Abstract

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a rare genetic disorder with highly variable phenotypes, ranging from psychosocial challenges and congenital malformations to benign tumors and even aggressive cancers. We hypothesize that this variability stems from additional rare variants in other genes, in addition to NF1 variants. The analysis of 32 NF1 patients revealed that those with solid cancers carried a higher average of cancer driver variants especially in DNA repair genes compared to those without (p < 0.05). An extended validation study using 217 NF1 carriers (71 cancer and 146 controls) from UK biobank confirmed significant enrichment of pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP) and uncertain significant (VUS) variants in DNA repair genes, in NF1 patients with tumors (FDR ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, P/LP variants in other genes are shown in those patients with NF1 ancillary traits such as cognitive impairments, macrocephaly, and connective defects. This study provides novel evidence suggesting that additional genetic variants in other genes may contribute to the phenotypic variability observed in NF1, indicating that rare secondary mutational events could influence specific manifestations, adding complexity to its variable expressivity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-09751-z.

Subject terms: Cancer, Genetics, Diseases, Molecular medicine, Pathogenesis

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is one of the most pleiotropic genetic disorders, predisposing individuals to various dysfunctions, ranging from psychosocial issues, congenital malformations to tumors1,2. Tumors can be benign, often involving the central and peripheral nervous systems, or malignant, particularly in solid organs2. Among solid tumors, breast cancer is one of the most recognized in association with NF1, with specific prevention included in surveillance guidelines1,2.

The role of genetic background is well established in many solid cancers, including breast cancer3. For instance, polygenic risk scores (PRSs) have been proposed to enhance the efficiency of cancer screening programs, extending their application to new age groups and diverse cancer types, such as breast, prostate, colorectal, pancreatic, ovarian, kidney, lung, and testicular cancers3. However, authors note that the absolute number of cancers in PRS-defined high-risk quantiles remains too low to justify screening, highlighting the importance of rare variants3.

The impact of rare causative variants on NF1 expression is well documented, particularly in genomic microdeletions encompassing the NF1 gene. For example, the increased lifetime risk of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors is attributed to the loss of the contiguous SUZ12 gene4. However, the contribution of other rare variants (P/LP), outside the context of microdeletion syndromes, remains unexplored. In this work using an exome sequencing approach, we hypothesize that the wide phenotypic variability observed in families segregating the same NF1 variant is due to additional rare causative variants in other genes, supporting an oligogenic model. Our study aimed to explore genotype-phenotype correlations, considering the diverse clinical presentations observed in this NF1 mutated cohort. Some individuals exhibited hallmark NF1-related features, such as café-au-lait spots, neurofibromas, Lisch nodules, or skeletal anomalies, while others presented with clinical complications, including various solid tumors. To address this, we conducted a detailed analysis to investigate whether specific NF1 mutations or additional rare variants in other genes might correlate with distinct phenotypic expressions.

Results

Description of the patient cohort

To investigate the role of secondary rare genetic variants in NF1 carriers of Pathogenic/likely Pathogenic (P/LP) genetic variants, we recruited a cohort of 32 NF1individuals with specific demographic characteristics (Supplementary Table 1).

Clinical and genetic data were obtained from patients who received counseling at the Medical Genetics Unit of the University Hospital in Siena, Italy, over a three-year period (Table 1). The variants identified in the NF1 gene have not been reported in the gnomAD database, except for the c.3916 C > T variant, which has been recorded with a frequency of 0.000879%. Among the 32 patients included in our study, 8 presented with malignant solid tumors. These tumors were classified based on their known association with NF1 into three categories: (1) NF1-related tumors (2/8, 25%): Breast cancer; (2) Rarely NF1-related tumors (4/8, 50%): Colon, ovarian, and endometrial cancers; (3) Non-NF1-related tumors (2/8, 25%): Prostate and pancreatic cancers.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and NF1 genetic variant of the cohort.

| Age | Sex | ID | Clinical Characteristics | cDNA NF1 | protein NF1 | Inheritance | VAF | ACMG | Clinvar | Varsome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical suspicion of NF1 | ||||||||||

| 33y | F | 1 | Café au lait spots, teratoma | c.479 + 1G > A | NA | 0.4 | P | P | P | |

| 4 m | M | F6-P | Café au lait spots | c.5305 C > T | p.Arg1769* | Mosaicism | 0.24 | P | P | P |

| 33y | F | 3 | Café au lait spots | c.7189 + 1G > T | NA | 0.4 | P | P | P | |

| 10 m | F | F4-P | Early growth failure, Café au lait spots | c.2941G > T | p.Glu981* | Father | 0.6 | P | NA | LP |

| 34y | M | F4-F | Café au lait spots, Axillary freckling, Neurofibromas | c.2941G > T | p.Glu981* | Father | 0.5 | P | NA | LP |

| 44y | F | 6 | Café au lait spots | c.5044T > C | p.Cys1682Arg | NA | 0.5 | P | Conflict | LP |

| 36y | M | 7 | Neurofibromas, freckles, Café au lait spots | c.2251 + 2delT | NA | 0.5 | P | NA | LP | |

| 7y | F | F7-P | Lenguage delay ADHD, precocious puberty, Café au lait spots > 15, Umbilical hernia | c.5552dupC | p.Gly1852TrpfsTer10 | De novo | 0.5 | P | NA | LP |

| 53y | F | 9 | Café au lait spots | c.5311 A > G | p.Lys1771Glu | NA | 0.5 | LP | P/LP | P |

| 9y | F | F8-P | Café au lait spots > 13, precocious puberty with absent pubertal hair | c.4624 C > T | p.Leu1542Phe | De novo | 0.4 | LP | VUS | VUS/LP |

| 34y | M | F5-P | Café au lait spots, Axillary freckling, glioma, short stature, peculiar face | c.1730T > G | p.Met577Arg | Father | 0.3 | LP | LP | VUS/LP |

| 70y | M | F5-F | Café au lait spots, Axillary freckling, neurofibromas | c.1730T > G | p.Met577Arg | Father | 0.3 | LP | LP | VUS/LP |

| Autism spectrum disorder, language delay and malformations | ||||||||||

| 11y | M | F9-P | Lenguage delay and macrocephaly | c.3916 C > T | p.Arg1306* | Mosaicism | 0.21 | P | P | P |

| 2 m | M | F1-P | Polysyndactyly and macrocephaly | c.3611G > T | p.Arg1204Leu | Father | 0.5 | LP | P | P |

| 36y | M | F1-F | Undescended testicle | c.3611G > T | p.Arg1204Leu | Father | 0.5 | LP | P | P |

| 2y | F | F2-P | Early growth failure and developmental delay | c.6213 A > T | p.Gln2071His | Father | 0.5 | LP | NA | VUS |

| 39y | M | F2-F | School support and lenguage delay | c.6213 A > T | p.Gln2071His | Father | 0.5 | LP | NA | VUS |

| 30y | F | F3-P | Neurodevelopmental disorder, treatable epilepsy | c.4227G > A | p.Met1409Ile | Father | 0.5 | LP | VUS | VUS/LP |

| 60y | M | F3-F | Depression | c.4227G > A | p.Met1409Ile | Father | 0.57 | LP | VUS | VUS/LP |

| Fetus | F | 20 | c.569T > A | p.Leu190* | NA | 0.2 | P | P | P | |

| Solid adult cancer | ||||||||||

| 68y | F | 21 | Endometrial cancer | c.6147 + 1G > A | Mosaicism | 0.28 | P | P | P | |

| 76y | F | 22 | Breast cancer | c.1339 C > T | p.Leu447Val | NA | 0.4 | LP | VUS | VUS/LP |

| 44y | M | 23 | Juvenile Polyposis | c.5083 C > T | p.Arg1695Trp | NA | 0.5 | LP | VUS | VUS/LP |

| 63y | M | 24 | Prostate Cancer | c.4924G > A | p.Val1642Ile | NA | 0.5 | LP | VUS | VUS |

| 45y | M | 25 | Colon Cancer | c.8104dupT | p.Tyr2702LeufsTer8 | NA | 0.5 | P | NA | LP |

| 71y | F | 26 | Ovarian Cancer | c.5351 A > G | p.Tyr1784Cys | NA | 0.5 | LP | VUS | VUS/LP |

| 73y | F | 27 | Pancreatic Cancer | c.644G > A | p.Ser215Asn | NA | 0.5 | LP | VUS | VUS |

| 51y | F | 28 | Breast Cancer | c.320 C > T | p.Thr107Met | NA | 0.4 | LP | VUS | VUS |

| Myopathies and Autoinflammatory diseases | ||||||||||

| 69y | F | 29 | Myopathy | c.5351 A > G | p.Tyr1784Cys | NA | 0.5 | LP | VUS | VUS/LP |

| 20y | M | 30 | Behçet disease | c.7466 A > G | p.Lys2489Arg | NA | 0.6 | LP | Conflict | VUS |

| Paucisymptomatic parents | ||||||||||

| 51y | M | 31 | c.878_880delACA | p.Asn293del | NA/Germline | 0.3 | LP | NA | VUS | |

| 40y | M | 32 | c.5020G > A | p.Val1674Ile | NA | 0.4 | LP | VUS | VUS | |

The samples 6;9;12;19,29;31 were utilized as the control cohort (non cancer) in the nested oncological study. The table is divided into five panels based on the clinical classification of the patients: “Clinical suspicion of NF1”, “Autism spectrum disorder, Language delay and malformations”, “Solid Adult Cancer”, “Myopathies and Autoinflammatory diseases”, and “Paucisymptomatic parents”. VAF variant allele frequency. ACMG American college of medical genetics and genomics classification, P pathogenic, LP likely Pathogenic,VUS variant of uncertain significance.

A nested study was conducted within the entire cohort, including 8 NF1 patients with solid malignant cancers, who were matched with 6 NF1 patients without cancer based on sex and age distribution. The study aimed to identify rare genetic variants predisposing to adult-onset solid malignancies. The baseline characteristics of NF1 carriers > 40 years are added in Supplementary Table 2.

Genetic data were derived from exome sequencing routinely performed in clinical practice. Variant prioritization was initially conducted using the eVAI tool, which considers rarity (< 0.05 minor allele frequency [MAF]) in public databases as a key selection criterion. A second filtering step employed an internal database to exclude variants that appear rare in public databases but are enriched in the local population (< 0.001 MAF). Finally, the analysis focused on a panel of 229 genes known to be associated with solid cancers.

Cancer driver variants enriched in NF1 patients with solid tumors

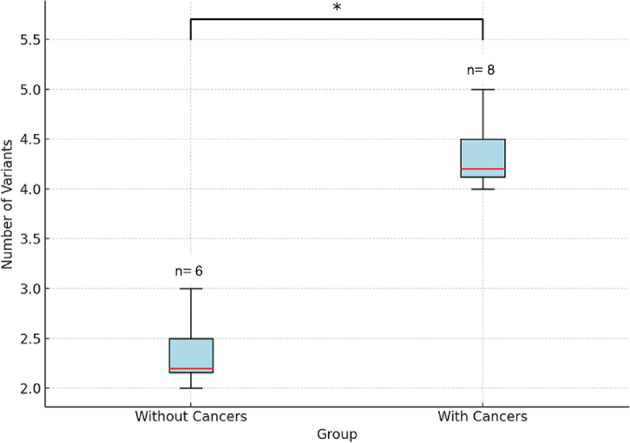

After filtering, NF1 carriers with solid cancers had a mean of 4.12 variants (P/LP/VUS) per individual, compared to 2.16 variants per individual in NF1 carriers without cancers. This difference was statistically significant according to the Mann-Whitney U test (z-score: 2.066; p = 0.038) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Variant burden in NF1 patients versus controls.

The box plot illustrates an increased number of germline rare variants (P/LP/VUS) in cancer driver genes among NF1 carriers with solid cancers compared to those without. The y-axis represents the number of rare variants in cancer driver genes, highlighting a significantly higher burden in NF1 carriers with cancers (Mann-Whitney U test (z-score: 2.066; p = 0.038)).

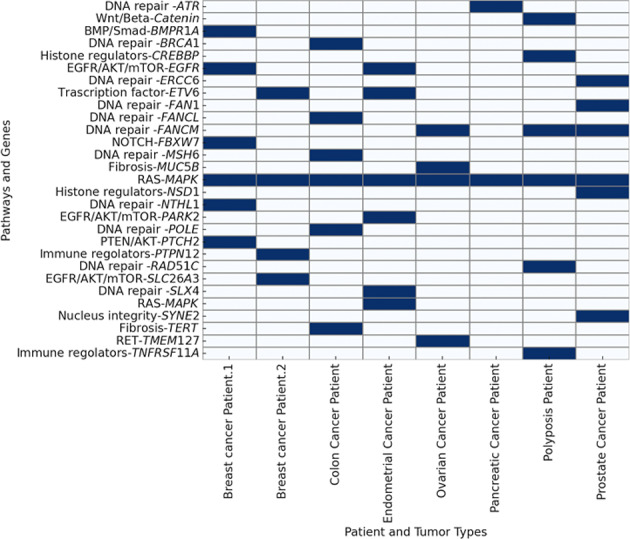

Gene combination analysis reveals that at least one variant (P/LP/VUS frequently two or more) in DNA repair pathways is present in the majority of cases (7/8). These include classical DNA repair genes (e.g., BRCA1, MSH6, POLE, ERCC6, NTHL1, RAD51C, ATR) and/or FANC genes (e.g., FANCL, FANCM, SLX4, FAN1) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Gene Variants and tumor associations. This Figure illustrates the presence of rare variants classified as P (Pathogenic), LP (Likely Pathogenic) or VUS (Variant of Uncertain Significance) within cancer driver genes across different patients. X-axis: Represents individual patients categorized by tumor type. Y-axis: Lists genes and pathways involved in cancer-related mechanisms. Blue-colored cells: Indicate the presence of a rare P, LP or VUS variant in the corresponding gene for a specific patient. White-colored cells: Indicate the absence of such variants in the respective genes for that patient.

In addition, variants are often observed in alternative pathways, including the RAS-MAPK pathway (e.g., SPRED1, linking to neurofibromin), EGFR/AKT/mTOR (e.g., PARK2, SLC6A3, EGFR), BMP/Smad (e.g., BMPR1A), PTEN/AKT (e.g., PTCH2), NOTCH (e.g., FBXW7), and WNT/β-catenin (e.g., AXIN1). Other notable pathways and functions involved include RET (e.g., TMEM127), histone regulation (e.g., NSD1, CREBBP), immune regulation (e.g., TNFRSF11A, PTPN12), fibrosis (e.g., TERT, MUC5B), nuclear and Golgi integrity (e.g., SYNE2), and transcription regulation (e.g., ETV6) (Fig. 2). The P/LP/VUS variants filtered from virtual cancer panel are all listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Trio Patient IDs follow the convention F#-X, where F# represents the family number, P indicates the proband, M refers to the mother, and F to the father.

Validation of cancer variant enrichment using UK biobank

To validate the findings observed in our cohort, we extended the analysis to the UK Biobank dataset (Supplementary Table 4). Specifically, we identified all patients carrying a pathogenic/ likely pathogenic variant in the NF1 gene according to ACMG annotation, resulting in a total of 217 individuals. Among them, n = 71 (32.72%) have a history of reported cancer and controls (n = 146, 67.28%), with a comparable mean age of approximately 60 years between the two groups.

Subsequently, we analyzed the number of P, LP and VUS with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≤ 0.001, as annotated by ACMG, in the 208 cancer-associated genes listed in the Genturis panel.

When considering all variant types (P/LP/VUS) in these genes, no statistically significant difference was observed in their distribution between the case and control groups (Fisher’s exact test, all p-values > 0.05), and the mean number of variants per individual was also comparable between cases (1.57 variants/individual) and controls (1.45 variants/individual).

To investigate the functional impact of rare variants in cancer-related genes, we performed a Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) using a ranked gene list based on the difference in cumulative pathogenicity scores between cases and controls. This approach allowed us to assess whether specific biological pathways were disproportionately affected in either group.

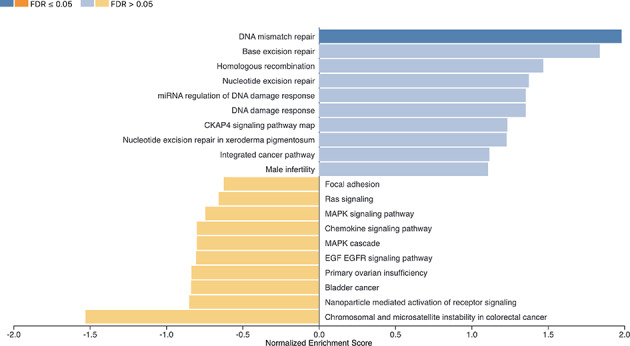

The analysis revealed a clear enrichment of DNA repair-related pathways in genes with higher pathogenicity scores in the case group. In particular, the DNA mismatch repair pathway reached statistical significance (FDR ≤ 0.05), while other pathways such as base excision repair, homologous recombination, and nucleotide excision repair showed positive enrichment scores (NES > 0), though with FDR values > 0.05 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Results of Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) based on cumulative pathogenicity scores.GSEA was performed on a ranked list of genes ordered by the difference in cumulative pathogenicity scores between cases and controls. Positive Normalized Enrichment Scores (NES) indicate pathways enriched in genes more pathogenic in cases, while negative NES reflect enrichment in controls. The color of each bar indicates statistical significance based on False Discovery Rate (FDR): dark blue = FDR ≤ 0.05; light blue = FDR > 0.05; orange = enrichment in controls. DNA repair-related pathways showed the strongest enrichment in the case group.

Rare variants shaping ancillary phenotypes in NF1 patients

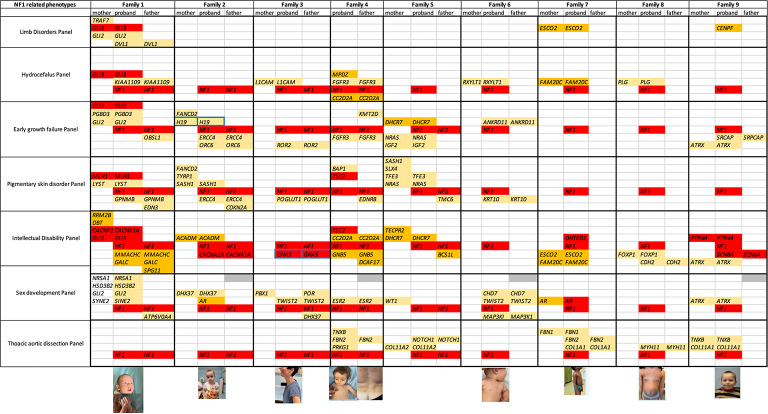

We expanded the analysis of rare variants in genes filtered by following clinical panels: growth failure in early childhood, sex development, hydrocephalus, pigmentary skin disorders, intellectual disability and thoracic aortic aneurysms virtual panel (Genomics England PanelApp). Only probands for whom TRIO (proband, father, mother) samples were available were subjected to a descriptive analysis of rare variants aimed at explaining ancillary phenotypes in NF1 (Fig. 4).

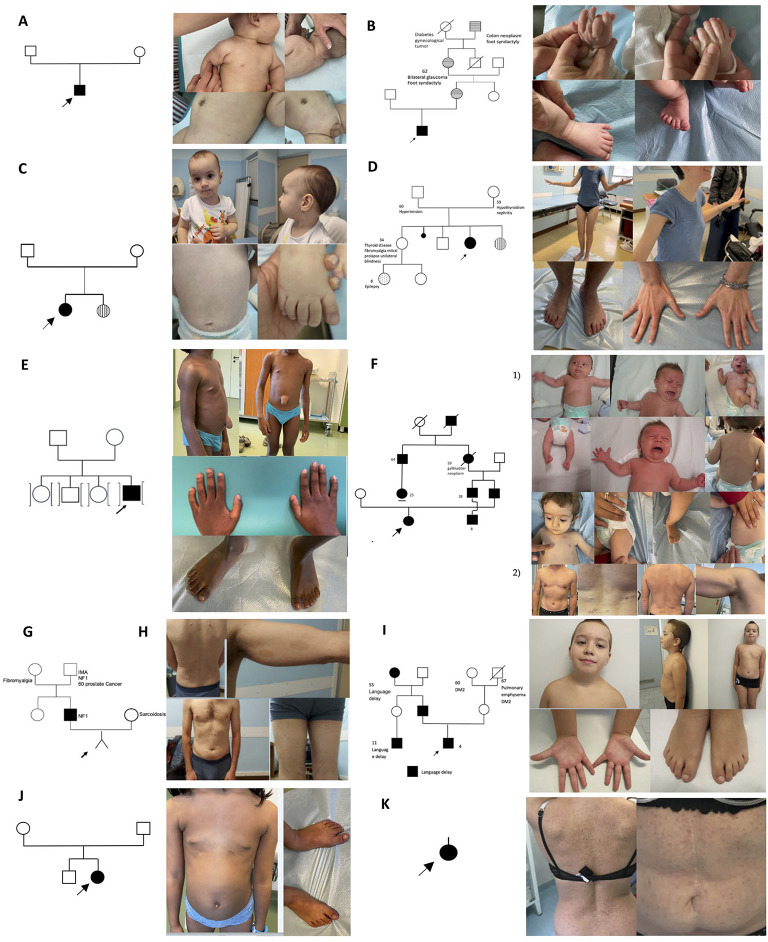

Fig. 4.

Pedigrees with Segregating NF1 Variants. (A) A de novo NF1 case of a 4-month-old child (F6-P). (B) Family 1 was identified in the neonatology unit due to the baby presenting with macrocephaly and polysyndactyly (F1-P). (C) Family 2 was identified in the pediatric unit due to early growth failure and a neurodevelopmental disorder (F2-P). (D) Family 3 was identified in the pediatric-neuropsychiatry unit due to epilepsy and a neurodevelopmental disorder (F3-P). (E) Precocious puberty case. A 7 years-old male with a large umbilical hernia and abdominal neurofibroma (F7-P). (F) Family 4 was identified in the pediatric unit based on skin characteristics. Both the daughter F4-P1 and the father F4-F2 are shown. (G) Family 5 was identified during prenatal counseling of the partners (F5-P; F5-F). (H) Sporadic case a 36-year-old man presenting with multiple neurofibromas, freckles, and café-au-lait patches (ID 7). (I) An 11-years old male from family 9 with mosaic NF1 variant (F9-P). (J) A 9-years old female from family 8 with de novo NF1 variant (F8-P). (K) Sporadic case a 44-year-old woman presenting with multiple café-au-lait patches (ID 6).

In nine cases, the proband’s parents were tested. In two instances, the variant was de novo, specifically in families 7 and 8 (Fig. 4E and J). In two apparently de novo cases, the variant resulted from somatic mosaicism (Fig. 4A and I), while in five cases, it was inherited from one parent, which was always the father. The five families with inherited NF1 variants were identified as follows: family 1 was identified in the neonatology unit due to macrocephaly and polysyndactyly (Fig. 4B); family 2 in the pediatric unit for early growth failure and neurodevelopmental disorder (Fig. 4C); family 3 in the pediatric-neuropsychiatry unit for epilepsy and neurodevelopmental disorder (Fig. 4D); family 4 in the pediatric unit for skin-related characteristics (Fig. 4F); and family 5 during prenatal counseling of the partner (Fig. 4G).

We subsequently investigated the presence of additional rare variants in the nine cases where parental DNA was available, allowing for the clear determination of inheritance for both NF1 and additional rare variants (Fig. 5). Notably, 45% of these patients (4/9) harbored at least one pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in another dominant gene (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Gene and Phenotype Combinations. This figure illustrates the combinations of genes and phenotypes observed in the nine cases where both parents were also genetically characterized.The red box indicates pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants in dominant disorders, the yellow box indicates P/LP variants in recessive disorders, and the beige box represents variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in dominant disorders. The GNAS and H19 gene, boxed in blue, are paternally imprinted, with the disease caused by the inheritance of the mutation on the maternal allele. Gray boxes indicate phenotypes that are not assessable due to the young age of the patient. All the variants in the mentioned genes are reported in Supplementary Table 5.

Regarding short stature, we observed that it becomes apparent when NF1 variants are combined with other rare variants that confer similar susceptibility. For instance, in Family 5, the NF1 variant was inherited from the father (who lacks any additional variants conferring the same risk), while additional variants were inherited from the mother (who does not carry the NF1 variant): NRAS, IGF2 and DHCR7 (selected from the “growth failure in early childhood panel”).

In Family 2, the proband inherited the NF1 variant from the father (along with variants in two additional genes: ERCC4 and ORC6) and the H19 variant from the mother. Loss-of-function variants in H19 are known to cause growth failure and distinctive facial features, including a broad forehead, characteristic of Silver-Russell syndrome, which resembles the proband’s facial phenotype. Precocious puberty also manifests in combination with other rare variants. For example, the proband of Family 7 (male) (Fig. 4E) exhibited precocious puberty associated with a de novo variant in the NF1 gene, combined with a hemizygous reduction in the number of triplets in one allele of the AR gene. This alteration is known to enhance receptor function, leading to peripheral precocious puberty.

The proband of Family 1, who presents with polysyndactyly, carries an NF1 variant inherited from the father and a concurrent pathogenic variant in GLI3, a gene classically associated with polydactyly, inherited from the mother, who displays mild polydactyly.

The proband of Family 7, a 7-year-old male, presents with a large umbilical hernia and an abdominal neurofibroma, which was excluded by echography. He carries a de novo NF1 variant along with a distinctive combination of rare VUS variants in FBN1 (inherited from the mother), FBN2, and COL1A1 (both inherited from the father).

Analyzing the “intellectual disability gene panel,” four cases referred by the pediatric-neuropsychiatry unit were found to have, on average, 2.7 additional variants alongside the NF1 variant. At least one of these was a pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) variant in a well-known dominant neurodevelopmental disorder gene, including GLI3, CACNA1A, TSC2, GNAS, PTPN4 and SCN8A (Fig. 5). Notably, the latter two genes (PTPN4 and SCN8A) were identified in the same patient, an 11-year-old male from Family 9 (Fig. 4I) with a mosaic NF1 variant (21%). In this case, PTPN4 was inherited from the mother and SCN8A from the father. A six-year follow-up confirmed the presence of a neurodevelopmental disorder in this patient, with no associated skin abnormalities.

Discussion

Huntley et al. reported that polygenic risk scores (PRS) could explain 37% of breast cancer cases, 46% of prostate cancer cases, 34% of colorectal cancer cases, 29% of pancreatic cancer cases, 26% of ovarian cancer cases, 22% of renal cancer cases, 26% of lung cancer cases, and 47% of testicular cancer cases2. These findings highlight that a significant proportion of genetic predisposition remains unexplained.

This highlights the complexity of cancer genetics and the likelihood that additional rare variants may contribute to tumorigenesis beyond common polygenic risk factors.

One such factor is NF1, a well-established tumor suppressor gene encoding neurofibromin, a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) that negatively regulates the Ras signaling pathway, which is critical for cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival5. Loss of NF1 function leads to constitutive Ras activation, promoting uncontrolled cellular growth and increasing tumorigenic potential6. The hypothesis is that the incomplete penetrance in the development of solid tumors in NF1 mutations is due to the occasional co-occurrence of causative variants in other cancer driver genes which may shift dramatically the cancer risk, and this is what we highlighted in our study7.

In our internal cohort, we observed that NF1 carriers with malignant solid cancers had a mean of 4.12 variants (P/LP/VUS) per individual, compared to 2.16 variants in NF1 carriers without cancers. This difference was statistically significant (Mann-Whitney U test: z = 2.066; p = 0.038). The variants identified in cancer driver genes, predominantly in cases, are primarily located in genes involved in DNA repair pathways.

To validate this observation, we performed a confirmation analysis using the UK Biobank cohort8. We selected individuals carrying a pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variant in the NF1 gene, and assessed the occurrence of any malignant solid tumors within this genetically defined group. A total of 71 individuals reported a diagnosis of at least one malignant solid tumor. It is important to note that this analysis was not limited to NF1-related tumor phenotypes, but rather aimed to evaluate the broader cancer susceptibility in this population. Although no significant differences were observed in the overall number of pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), or variants of uncertain significance (VUS) between cases and controls, a functional divergence emerged when considering the pathogenic impact of the variants through Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). Rather than simply counting variants, we incorporated ACMG-based pathogenicity scores to weight each variant’s biological relevance, and aggregated these scores at the gene level9.

By ranking genes according to the difference in cumulative pathogenicity scores between cases and controls, we were able to identify pathways in which genes were more heavily burdened by pathogenic variants in the case group. Notably, this approach revealed a significant enrichment of DNA repair-related pathways, such as mismatch repair, base excision repair, and homologous recombination, among the genes more affected in cases.

This result suggests that while the mutational burden may appear quantitatively similar, its functional distribution across biological pathways differs. This supports the idea that it is not simply the presence of rare variants, but their biological context and cumulative impact that may underlie disease risk.

These findings are clinically relevant, as the capture of such rare variants could improve cancer screening programs in NF1 carriers.

Regarding the analysis of ancillary phenotypes in TRIO samples, we observed that in all inherited cases within our cohort (n = 5), the variant was transmitted by the father. This observation tentatively aligns with earlier findings by Stephens et al. (1992), who speculated that most variants could arise in paternal gametes, potentially hinting at an imprinting-like mechanism10. However, while imprinting has been proposed as a possibility for NF1, conclusive evidence remains absent, and its role, if any, is highly uncertain. Short stature is reported in 10–30% of NF1 patients, yet its underlying cause remains unclear11,12. We propose that short stature may result from a combination of the NF1 variant inherited from one parent and additional rare causative variants inherited from the other parent that confer the same risk. For instance, in Family 5, the proband inherited the NF1 variant from the father (who lacked additional risk variants) and five rare causative variants from the mother, including NRAS, IGF2, and DHCR7.

In Family 2, the proband inherited the NF1 variant from the father alongside variants in two growth failure-related genes (ERCC4 and ORC6) and the maternally expressed H19 gene. Loss-of-function variants in H19 cause Silver-Russell syndrome, characterized by short stature and distinctive facial features such as a broad forehead, which closely resemble those observed in the proband.

Precocious puberty (PP) is reported in up to two-thirds of NF1 children, though the underlying mechanism remains unclear13. Central PP (CPP) has been attributed to optic pathway gliomas in only a fraction of cases14. We found that PP likely depends on rare variant combinations. For instance, in the probands of Family 7 (male), we identified peripheral precocious puberty (PPP) due to increased androgen receptor (AR) activity caused by a reduced number of trinucleotide repeats. PPP, also known as precocious pseudopuberty, is gonadotropin-independent. This raises questions about the current treatment approach using GnRH analogs (Decapeptyl), which are only effective for gonadotropin-dependent puberty. In such cases, antiandrogen or aromatase inhibitors may be more appropriate15.

Polydactyly is rarely reported in NF1 patients. Mensink et al. attributed this to other genes within NF1 microdeletions16. We identified a proband in Family 1 with polysyndactyly and a concurrent pathogenic variant in GLI3, a gene classically associated with polydactyly. This demonstrates that pathogenic variants in additional genes, rather than NF1 alone, are responsible.

Connective tissue abnormalities, such as joint hypermobility, mitral valve prolapse, and aortic dilatation, have been reported in some NF1 patients16,17. These have sometimes been linked to NF1 microdeletions. Here, we describe a 7-year-old male with a large umbilical hernia (not caused by abdominal neurofibroma) and a rare variant combination involving FBN1, FBN2, and COL1A1, suggesting a genotype-phenotype correlation.

Neurodevelopmental disorders are frequently observed in NF1 patients, yet a convincing explanation is lacking1,2. In our cohort, we identified an average of 2.7 additional variants per patient, including at least one pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in dominant neurodevelopmental disorder genes such as GLI3, CACNA1A, TSC2, PTPN4, and SCN8A. For instance, in Family 9, an 11-year-old male with a mosaic NF1 variant (21%) carried a compound pathogenic variant: PTPN4 inherited from the mother and SCN8A from the father. These findings suggest that neurodevelopmental phenotypes in NF1 may result from additional high-penetrance variants.

Our findings hold significant relevance for both clinical policy and clinical practice. The capture of rare variants could be leveraged to improve screening programs for NF1 carriers and to identify specific gene sets (“gene cards”) for personalized treatment approaches. Moreover, these results contribute to a better understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying NF1 and provide a foundation for future research.

The analysis of ancillary phenotypes in NF1 patients was purely descriptive, as no control cohort was included. Future studies could introduce control groups utilizing biobank datasets to better investigate the potential role of rare variants in shaping these phenotypes and to strengthen the clinical significance of our findings.

This approach will enable a deeper exploration of the genetic contributions to secondary traits in NF1 patients, paving the way for improved precision medicine strategies. The interpretation of our findings should account for potential confounding factors, particularly the influence of polygenic risk scores (PRS), common variants, and environmental exposures.

While our study primarily focused on rare genetic variants, the overall genetic risk for an individual may be shaped by a combination of rare high-penetrance mutations and common low-penetrance variants.

Moreover cancer risk is not solely dictated by genetic predisposition; environmental exposures play a fundamental role in disease development. Factors such as smoking, diet, pollution, radiation, and lifestyle choices (e.g., physical activity and alcohol consumption) can significantly modify individual risk, often in interaction with genetic background.

In our study, we considered pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in the NF1 gene according to the ACMG classification as the primary criteria for inclusion. However, to ensure transparency and comprehensive reporting, we also included variant evaluations from additional reference databases such as ClinVar and Varsome. The variants reported as VUS in one database exhibit a conflict in pathogenicity, which is, however, more skewed towards being likely pathogenic when considering the integrated evaluation from the two other classifiers.

While it is well established that loss-of-function (LoF) variants (e.g., nonsense, frameshift, and splice-site mutations) are predominant in NF1, missense variants in functionally critical regions of neurofibromin have also been reported to contribute to NF1 pathogenesis18.

In our cohort, only 12 out of 32 patients exhibit a typical NF1 phenotype, and within this subgroup, missense variants account for 30%, which is slightly higher than the expected 10–15%. This percentage may be influenced by the presence of the recurrent missense variant c.1730T > G, which was identified in two patients blood-related. When considering the rest of the cohort, which presents with a more atypical phenotype, it is reasonable to find NF1 variants that differ from the loss-of-function mutations typically responsible for the classical NF1 phenotype.

It is increasingly recognized that the type and functional impact of NF1 variants critically modulate clinical expressivity and cancer predisposition. While canonical loss-of-function mutations typically result in the full neurocutaneous syndrome, hypomorphic missense or low-penetrance alleles may fail to produce overt diagnostic features yet still predispose to solid tumors via partial deregulation of RAS/MAPK signaling. This is consistent with recent findings that pathogenic NF1 variants may be found in individuals without a clinical diagnosis but with increased cancer risk19. Our data support this concept and emphasize the importance of extending genetic counseling and surveillance even to asymptomatic NF1 variant carriers.

Methods

Study design

This study was conducted on a cohort of patients attending the Medical Genetics Unit in Siena, Italy, over a period of three years. These patients were referred for various clinical reasons and were found to carry a pathogenic or likely pathogenic NF1 variant. The 32 patients included in our study were identified based on the presence of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic NF1 mutation rather than a uniform clinical diagnosis of NF1. These individuals came to our attention for different clinical reasons, and not all of them had a classic clinical NF1 diagnosis at the time of recruitment.

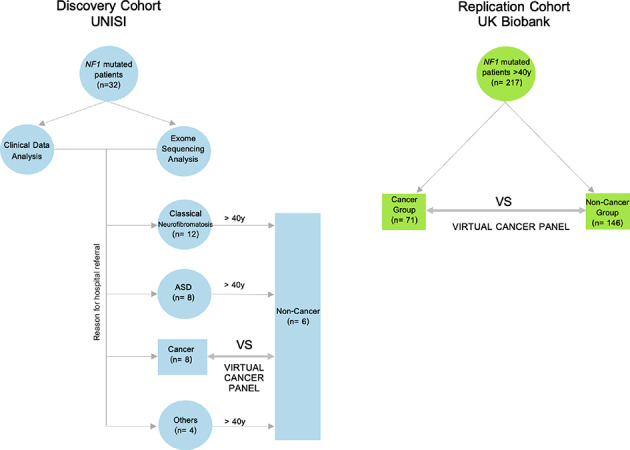

A flowchart summarizing the experimental workflow is presented in Fig. 6. This diagram outlines the different cohorts analyzed and the analyses performed on each group (Discovery and Validation analysis).

Fig. 6.

Experimental design. The Discovery Cohort UNISI involved 32 NF1 mutated patients underwent clinical data and exome sequencing analysis. Patients were divided into different cohorts based on their clinical characteristics: ‘NF1 Clinical Diagnosis’, ‘ASD’, ‘Solid Cancer’ and ‘Others’. The ‘Solid Cancer’ group and ‘Non-Cancer group’ (composed of patients older than 40 years from other groups) underwent a nested study and analysis using the virtual cancer panel. The Replication Cohort UK Biobank validated the nested study in 217 NF1 patients from the UK Biobank, similarly divided into Solid Cancer (n = 71) and Non-Cancer (n = 146) group. Arrows indicate the study workflow and relationships between groups. ASD Autism.

Participants

Patients included in the study carried pathogenic or likely pathogenic NF1 variants, as classified by ACMG criteria, and their ages ranged from birth to 76 years. Patients with variants of uncertain significance (VUS), likely benign, or benign NF1 variants, as classified by ACMG criteria, were excluded. Controls for the nested study were selected by matching sex and age, with a ratio of 0.75 controls per patient. The cohort consists of 32 related and unrelated individuals, 97% of whom are of Caucasian ethnic origin.

Procedures

Clinical data were obtained from medical records, while genetic data were retrieved from exome sequencing routinely performed. Genetic variants were identified using exome analysis (6,794 morbid genes) with the TruSight One Expanded Sequencing Panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sample preparation followed the Nextera Flex for Enrichment manufacturer protocol, which uses a bead-based transposome complex to fragment genomic DNA and tag it with adapter sequences in a single step. After DNA fragmentation, a limited-cycle PCR was used to add adapter sequences to the DNA fragments. Subsequently, a target enrichment workflow was applied. Denatured double-stranded DNA libraries were hybridized with biotinylated TruSight One Expanded Oligonucleotide probes. Streptavidin Magnetic Beads (SMB) captured the targeted library fragments, which were then amplified and sequenced. Exome sequencing was conducted using the Illumina NovaSeq6000 System, and reads were aligned to the hg19 reference genome using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) with a mean target coverage depth of 100. The variant calling was performed using the Illumina DRAGEN Enrichment BaseSpace App and we consider PASS variant with depth > 20. Variants with allele frequencies between 0.4 and 0.6, as well as inherited variants, were considered constitutive heterozygous. Variants with allele frequencies ≤ 0.3, without segregation confirmation or classified as de novo, were considered potential somatic mosaics. For these variants, the suspected somatic mosaicism, initially detected through NGS sequencing, was confirmed using Sanger sequencing (Supplementary File 1).

Bioinformatic and statistical analysis on internal cohort

Genetic variants were prioritized using eVAI software (enGenome) based on their rarity in public databases (minor allele frequency [MAF] < 0.05). Variant frequencies were then compared with a local database of 6,161 exome-sequenced subjects, all analyzed using the same methodology over the past five years. Only variants with a MAF < 0.001 were retained. Variants were further classified by ACMG as Pathogenic, Likely Pathogenic, or Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS). Selected variants belonged to one of the following clinical panels: growth failure in early childhood, sex development, hydrocephalus, pigmentary skin disorders, intellectual disability, thoracic aortic aneurysms, or the GENTURIS/SOLVE-RD project panel. The GENTURIS panel was designed by a group of experts from the ERN GENTURIS (European Reference Network on Genetic Tumour Risk Syndromes). The selection of genes included in the panel was based on clinical and scientific criteria, considering the strength of evidence supporting their association with hereditary cancers. Data from association studies, clinical databases, and scientific literature were utilized to ensure the panel’s clinical relevance. The other mentioned virtual panels were downloaded from Genome England https://panelapp.genomicsengland.co.uk.

Statistical differences in the number of retrieved variants between patients and controls were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test in the nested study.

Validation cohort selection

The validation analysis was conducted using the UK Biobank dataset under the application number 78,537. Patients were included if they carried a pathogenic/likely pathogenic NF1 variant according to ACMG annotation. Diagnosis ICD10 data field was used to distinguish the cases, that is patients diagnosed with at least one tumor type, and controls those without any tumor diagnosis. Finally, NF1 carriers cohort was balanced to have a similar age median (i.e. 60,7y). A total of 217 individuals were identified and categorized into cases (n = 71, 32.72%) and controls (n = 146, 67.28%) based on their cancer status. Genetic variants were filtered based on their classification as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, or variants of uncertain significance (VUS), with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≤ 0.001, as annotated by ACMG. The analysis focused on the 208 cancer-associated genes listed in the Genturis panel. For each individual, the total number of retained variants was calculated. The median number of pathogenic variants was compared between cases and controls using the two-sided Wilcoxon test, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. We performed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) using a ranked list of genes based on the difference in cumulative pathogenicity scores between cases and controls. For each gene, variant pathogenicity scores (derived from ACMG classifications via the eVAI platform) were summed separately in each group. The ranking metric was calculated as the sum in cases minus the sum in controls.

The analysis was conducted using WebGestalt (www.webgestalt.org), with enrichment tested against the WikiPathways database for Homo sapiens. Pathways with FDR ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the NeuroNext project (Version No. 4, dated July 18, 2023), approved on August 22, 2023 (A.R.).This work was supported by PNRR – Next Generation EU: Mission 4 Component 2 (M4C2) – Investment 1.4 – Acronym MNRA – Spoke 1, National Center for Gene Therapy and Drugs Based on RNA Technology (to AR); PNC-E.3 INNOVA: Innovative Ecosystem for Health - Mission 6, Component 2 - Innovation, Research, and Digitalization of the National Health Service - Hub Life Science – Advanced Diagnostic (to A.R.); GENERA FSC 2014-2020: Personalized Medicine Genome (POS-Ministry of Health T3-AN-04, to A.R.); EU H2020-SC1-FA-DTS-2018–2020: International Consortium for Integrative Genomics Prediction – Grant Agreement No. 101016775 (to A.R.); PNRR THE – Tuscany Health Ecosystem: Spoke No. 7, Translational Medicine for Rare, Oncological, and Infectious Diseases (to A.R.); and ERDERA: Diagnostic Research Workstream (to A.R.); INTERVENE (A.R).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, E.P., A.R.; methodology, E.P., G.C., S.M.; C.F., O.B.; software, E.P. and S.M.; validation, G.C. formal analysis S.M., E.P., G.C., C.F investigation, E.P., A.R., G.C, G.B., R.D.: resources, A.R.; data curation, E.P., C.F., A.R writing—original draft preparation, E.P.,A.R writing—review and editing E.P., G.C., A.R, O.B.; ; clinical part of the study and provided patient samples, S.G., R.C., S.M., I.M., S.T.M., R.P., M.B., A.R.; visualization, E.P. A.R.; supervision, A.R.; project administration, A.R; funding acquisition, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data generated in this study cannot be publicly shared due to restrictions in participant informed consent, which did not permit deposition in open-access repositories. Data access may be considered upon reasonable request and pending approval by the relevant ethics committee, subject to GDPR and institutional policies. Researchers can request the data we used from UK Biobank (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk) and the author to be contacted is Giulia Brunelli.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent, and the procedures were approved by the institutional ethics committee (Regional Ethics Committee for Clinical Trials of the Tuscany Region – South-East Area). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and or their legal guardian/parents whose images in this publication allow for personal identification.

Ethical approval waiver

The requirement for ethical approval for this study was waived by the Regional Ethics Committee for Clinical Trials of the Tuscany Region – South-East Area, which convened on August 22, 2023.

Informed consent waiver

The need for informed consent was waived by the Regional Ethics Committee for Clinical Trials of Tuscany - South East Area Section, which convened on August 22, 2023.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Carton, C. et al. on behalf of the ERN GENTURIS NF1 Tumour Management Guideline Group. ERN GENTURIS tumour surveillance guidelines for individuals with neurofibromatosis type 1. Clin. Med. 56, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Goetsch Weisman, A. et al. Neurofibromatosis- and schwannomatosis-associated tumors: approaches to genetic testing and counseling considerations. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 191, 2467–2481. 10.1002/ajmg.a.63346 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huntley, C. et al. Utility of polygenic risk scores in UK cancer screening: a modelling analysis. Lancet Oncol.24, 658–668. 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00156-0 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kehrer-Sawatzki, H., Mautner, V. F. & Cooper, D. N. Emerging genotype-phenotype relationships in patients with large NF1 deletions. Hum. Genet.136, 349–376 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cichowski, K. & Jacks, T. NF1 tumor suppressor gene function: narrowing the GAP. Cell104, 593–604 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Dasgupta, B. & Gutmann, D. H. Neurofibromin regulates neural stem cell proliferation, survival, and astroglial differentiation in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurosci.25, 5584–5594 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fortin, T. et al. Alterations in DNA damage response and repair pathways in neurofibromatosis type 1-associated gliomas. Neuro-Oncol. 25, 101–113 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature562, 203–209 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation. Genet. Med.17, 405–424 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephens, K. et al. Preferential mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene in paternally derived chromosomes. Hum. Genet.88, 279–282. 10.1007/BF00197259 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soucy, E. A. et al. Height assessments in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. J. Child. Neurol.28, 303–307. 10.1177/0883073812446310 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ucar, H. K. et al. Short stature and insulin-like growth factor-I in neurofibromatosis type 1. Ann. Med. Res.28, 1763–1766. 10.5455/annalsmedres.2020.07.714 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santoro, C. et al. Pretreatment endocrine disorders due to optic pathway gliomas in pediatric neurofibromatosis type 1: multicenter study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.105, dgaa138. 10.1210/clinem/dgaa138 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinheiro, S. L. et al. Precocious and accelerated puberty in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: results from a close follow-up of a cohort of 45 patients. Horm. (Athens). 22, 79–85. 10.1007/s42000-022-00411-9 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feuillan, P., Merke, D. W., Leschek, E. W. & Cutler, G. B. Jr. Use of aromatase inhibitors in precocious puberty. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 6, 303–306. 10.1677/erc.0.0060303 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mensink, K. A. et al. Connective tissue dysplasia in five new patients with NF1 microdeletions: further expansion of phenotype and review of the literature. J. Med. Genet.43 (e8). 10.1136/jmg.2005.034256 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.PatelN.B. & StacyG.S. Musculoskeletal manifestations of neurofibromatosis type 1. Am. J. Roentgenol.199, 88–106. 10.2214/AJR.12.8565 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen, J. et al. Identification of pathogenic missense mutations of NF1 using computational approaches. J. Mol. Neurosci.74, 94. 10.1007/s12031-024-02271-x (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safanov, A. et al. Pathogenic NF1 variants in individuals without a clinical diagnosis of NF1 and implications for cancer susceptibility. Nat. Commun. 16, 3121 10.1038/s41467-025-57077-1 (2025).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data generated in this study cannot be publicly shared due to restrictions in participant informed consent, which did not permit deposition in open-access repositories. Data access may be considered upon reasonable request and pending approval by the relevant ethics committee, subject to GDPR and institutional policies. Researchers can request the data we used from UK Biobank (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk) and the author to be contacted is Giulia Brunelli.