Abstract

Social participation is recognized as a critical factor in reducing mortality and promoting healthy aging in middle-aged and older adults with cardiovascular disease (CVD). However, the determinants influencing social participation within this demographic remain poorly understood. The present study sought to assess the social participation status of middle-aged and older individuals with CVD and identify the factors influencing their participation levels. A cross-sectional analysis was conducted using 2018 data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) database. Descriptive statistics and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were employed to explore differences and correlations among variables. Latent class analysis was performed using Mplus 8.3 software, while logistic regression analysis was utilized to examine patterns of social participation and their associated factors. A total of 2388 participants were included in the analysis. Latent profile analysis identified four distinct social participation patterns: “individual participation,” “group participation,” “full participation,” and “low participation.” Significant differences (P < 0.05) were found across these patterns with regard to educational attainment, geographic location, living conditions, health insurance coverage, and alcohol consumption. Social participation was associated with health status, ADL, IADL, loneliness, and depression. High level of social participation as a component of healthy lifestyle has been identified to be effective in reducing CVD mortality. Therefore, targeted interventions to enhance social participation may improve cardiovascular health outcomes in middle-aged and older adults.

Keywords: Social participation, Middle-aged and older adults, Cardiovascular disease, Health status, Latent profile analysis

Subject terms: Cardiology, Diseases

Introduction

China is projected to experience rapid population aging in the coming decades. As individuals age and accumulate various pathological conditions, the sclerosis of large arteries, particularly the aorta, progressively diminishes their ability to cushion cardiovascular stress, thereby posing a significant threat to cardiovascular health1,2. As a result, the incidence and mortality associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) are anticipated to continue rising3. Research has consistently shown that CVD remains the leading cause of mortality and premature death in the Chinese population4. Furthermore, CVD is a major contributor to the decline in functional capacity and participation in health-related activities5. Addressing the cardiovascular health challenges associated with an aging population has thus become an urgent and critical priority6.

In recent years, growing evidence has underscored the profound impact of lifestyle on aging and CVD1,7,8. High levels of social participation, as an integral component of a healthy lifestyle, have been identified as effective in reducing CVD mortality and promoting healthy aging9,10. The theoretical link between social participation and health is robust, with studies conducted across various countries consistently demonstrating a positive correlation between active social participation and improved health outcomes11–13.

According to life cycle theory, individuals in middle age undergo a range of physiological and psychological changes as they transition into old age, which in turn affects their patterns of activity participation14–16. Numerous studies have demonstrated that older adults generally engage in lower levels of social activity, and this decline in participation tends to become more pronounced with advancing age17–19. Middle-aged and older adults are particularly susceptible to loneliness and negative emotions, often arising from factors such as living alone, limited social networks, and reduced engagement in social activities20. These emotional states are strongly linked to decreased physical activity and declining health21. Beyond exercise, Activities of Daily Living (ADL) play a pivotal role in maintaining the health of older adults. ADL encompasses essential daily behaviors that support independent living, social integration, and the fulfillment of specific social roles22. These activities are crucial for preserving autonomy and quality of life23. Engaging in social activities and enhancing social participation not only alleviates depression but also reduces disability rates and enhances overall health and quality of life within this demographic. While previous research has explored these factors individually, no comprehensive study has examined their combined impact on social participation in CVD patients. At present we have not seen large sample studies related to this, so we have done this by integrating these variables into a unified analytical framework.

In this study, Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) was employed to comprehensively investigate the factors influencing social participation in middle-aged and older adults with CVD24,25. The CHARLS survey was conducted on a random sample of households people aged 45 years and older. Therefore, we used CHARLS data in 2018 to investigate the social participation of middle-aged and elderly (45+) CVD patients in China, and analyzed the effects of health status, ADL and emotion on their social participation by classifying different social participation patterns. The findings provide a foundation for improving social participation levels, enhancing physical function, and alleviating depressive symptoms in this population. Moreover, these results offer valuable insights for healthcare professionals to develop more targeted and effective rehabilitation strategies aimed at improving the well-being of middle-aged and older patients with CVD.

Methods

Data and study sample

The data for this study were sourced from the fourth wave of the nationwide CHARLS conducted in 2018. CHARLS is a comprehensive, high-quality public microdata repository that includes a randomly selected sample of Chinese residents aged 45 years and older, drawn from both urban and rural areas across 28 provinces26. This dataset serves as a valuable resource for investigating issues related to population aging in China and facilitates interdisciplinary research on aging.

The selection of the five variables-health status, loneliness, depression, ADL, and IADL-was based on established evidence highlighting their relevance to social participation among middle-aged and older adults with CVD20–23.

Following the integration of CHARLS data and a thorough review of the relevant literature, 2,388 participants (Data screening was conducted in two stages: Stage 1: We included participants reporting affirmative answers to Question zdiagnosed_7_(n = 1279), representing prevalent CVD cases confirmed during the prior survey cycle (2015). Stage 2: We further incorporated participants with affirmative responses to DA007_7_ (n = 1,109), indicating new CVD diagnoses occurring between the 2015 baseline survey and the 2018 follow-up.) were included in this study. Ethical approval for the CHARLS rounds was granted by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015), and all participants provided informed consent prior to their inclusion in the survey.

Cardiovascular disease

CVD was identified based on responses to a health status item in the CHARLS questionnaire. Specifically, participants were asked, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have any of the following chronic diseases?” CVD was determined if participants responded affirmatively to this question regarding cardiovascular-related conditions.

Activity factors

The activity-related variables in this study included ADL and IADL. ADL encompassed six basic activities: dressing, bathing, eating, getting in and out of bed, toileting, and defecating. IADL consisted of six additional tasks: housework, cooking, shopping, using the telephone, taking medication, and managing household finances.

A standardized scale was employed to score all activities for consistency in analysis. If a participant reported “no difficulty” in completing an activity, it was assigned 1 point. If the participant reported “difficult but can still complete it,” “difficult and needs help,” or “unable to complete it,” the activity was scored 0 points. The scores for the six activities were then summed to generate a total score, ranging from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating a better ability to perform the activities.

Body function and structural factors

The study incorporated variables related to physical functioning and structural factors, including self-assessed health status, loneliness, the 10-item Flow Center Depression Self-Rating Scale, and life satisfaction:

Self-assessed health status

Respondents’ self-assessed health status was categorized based on their responses to the questionnaire. Those who answered “extremely satisfied,” “very satisfied,” or “relatively satisfied” were grouped under the category “satisfied,” while responses of “not very satisfied” and “not at all satisfied” were categorized as "dissatisfied."

Loneliness

Loneliness was assessed using the item “I feel lonely” from the questionnaire. Response options included “rarely or not at all (< 1 day),” “not too much (1–2 days),” “sometimes or half the time (3–4 days),” and “most of the time (5–7 days).” These responses were assigned scores of 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, with higher scores indicating greater levels of loneliness.

10-item flow center depression self-rating scale

Depression was measured using the 10-item Flow Center Depression Self-Rating Scale, which included items such as “I get annoyed by small things” and “I have a hard time concentrating when I do things.” The response options were the same as those used for the loneliness scale: “rarely or not at all (< 1 day),” “not too much (1–2 days),” “sometimes or half the time (3–4 days),” and “most of the time (5–7 days),” with scores of 1, 2, 3, and 4 assigned in order. For positively worded items, such as “I am hopeful for the future” and “I am happy,” the scores were reversed. Higher total scores reflected more pronounced symptoms of depression.

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was assessed using the questionnaire, with responses of “extremely satisfied,” “very satisfied,” “quite satisfied,” “not very satisfied,” and “not at all satisfied” assigned scores of 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively. Higher scores indicated greater life satisfaction.

Social participation

The primary outcome was defined as social participation as confirmed by a health status questionnaire that assessed the following questions: “Have you participated in any of the following social activities in the past month?” The 11 social activity options were grouped into five profiles: (1) Clubs and Friendships (options 1 and 4), (2) Helping Others (options 3 and 7), (3) Physical Fitness and Educational Activities (options 2 and 5), (4) Skill Learning Activities (options 8, 9, and 10), and (5) Other (option 11). Participants who reported engaging in these social activities were assigned a score of 1, while those who did not participate were given a score of 0.

Covariates

This study integrated demographic characteristics, residency status, insurance coverage, and health status data.

Demographic characteristics included gender, educational attainment, and marital status. Educational attainment was categorized as “illiterate,” “primary school and below,” “secondary school,” and “high school and above.” Specifically, individuals classified as “illiterate,” those who “did not complete primary school,” “graduated from private school,” or “completed primary school” were grouped under “primary school and below.” Those who “graduated from lower secondary school” were classified as “lower secondary school,” while “junior high school” graduates were categorized as “junior high school.” Individuals with “high school graduation,” “secondary school graduation” (including secondary teacher training and vocational high school), “college graduation,” “bachelor’s degree,” “master’s degree,” or “doctoral degree” were grouped under “high school and above.” Marital status was categorized as “married” or “not married.”

Residency status included place of residence and living arrangement. Place of residence was classified as either “urban” or “rural,” while living arrangement was classified as “living alone” (yes or no).

Insurance status was determined based on the presence or absence of health insurance (yes or no).

Health status included perceived health, smoking behavior, and alcohol consumption, each treated as binary variables (yes or no).

Statistical analyses

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation, with comparisons between two groups conducted using ANOVA. The Spearman/Kendall statistical method was used to analyze the non-normal distribution of some data sets. LPA is a statistical technique used to identify latent profiles based on individual response patterns across multiple items. This method optimizes model selection, improves classification accuracy, maximizes between-group heterogeneity, and minimizes within-group heterogeneity24,25. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, with group comparisons performed using the chi-square (X2) test. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the impact of independent variables on dependent variables.

Results

General information on the study population

This study utilized a cross-sectional design, analyzing data from the 2018 CHARLS database, with a focus on 2388 individuals diagnosed with CVD. Of these, 1096 (45.9%) were male and 1296 (54.1%) were female. Educational attainment was distributed as follows: 493 participants (20.6%) were illiterate, 1009 (42.3%) had completed primary school or less, 533 (22.3%) had completed secondary school, and 353 (14.8%) had attained at least a high school education. In terms of marital status, the majority (1918; 80.3%) were married or living with a partner. A significant proportion resided in rural areas (1828; 76.5%), and 2100 (87.9%) did not live alone. Health insurance was reported by 1,404 participants (58.8%).

With regard to health-related behaviors, 2101 individuals (88%) expressed satisfaction with their health status, 1406 (58.8%) were non-smokers, and 1699 (71.1%) abstained from alcohol consumption. Table 1 provides a comprehensive summary of the demographic and health-related characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants.

| Variable | N = 2388 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage (%) | |

| Demographic characteristic | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1096 | 45.9 |

| Female | 1296 | 54.1 |

| Educational level | ||

| Illiteracy | 493 | 20.6 |

| Primary education and below | 1009 | 42.3 |

| Middle school | 533 | 22.3 |

| High school and above | 353 | 14.8 |

| Marriage | ||

| With spouse present | 1918 | 80.3 |

| Not living with spouse | 470 | 19.7 |

| Living conditions | ||

| Location of residential address | ||

| City | 560 | 23.5 |

| Country | 1828 | 76.5 |

| Living alone | ||

| Yes | 288 | 12.1 |

| No | 2100 | 87.9 |

| Insurance | ||

| Medical insurance | ||

| Have | 1404 | 58.8 |

| Not have | 984 | 41.2 |

| Health status | ||

| Satisfied with your health | ||

| Yes | 2101 | 88.0 |

| No | 287 | 12.0 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes | 982 | 41.1 |

| No | 1406 | 58.9 |

| Drinking | ||

| Yes | 689 | 28.9 |

| No | 1699 | 71.1 |

Table 2 explores the social activity patterns of patients with CVD, revealing statistically significant differences in social participation associated with health insurance coverage and alcohol consumption (P < 0.05). Living alone exhibited a marginal effect on social participation (P = 0.072).

Table 2.

Social activities among patients with CVD exhibiting different characteristics.

| Variable | N | The total score Mean (SE) | F/t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristic | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1096 | 1.19 ± 0.05 | 0.840 | 0.401 |

| Female | 1292 | 1.13 ± 0.05 | ||

| Educational level | ||||

| Illiteracy | 493 | 1.07 ± 0.07 | 0.794 | 0.497 |

| Primary education and below | 1009 | 1.16 ± 0.05 | ||

| Middle school | 533 | 1.23 ± 0.07 | ||

| High school and above | 353 | 1.20 ± 0.20 | ||

| Marriage | ||||

| With spouse present | 1918 | 1.16 ± 0.03 | 0.530 | 0.597 |

| Not living with spouse | 470 | 1.12 ± 0.07 | ||

| Living conditions | ||||

| Location of residential address | ||||

| City | 560 | 1.20 ± 0.07 | 0.622 | 0.534 |

| Country | 1828 | 1.15 ± 0.04 | ||

| Living alone | ||||

| Yes | 288 | 1.36 ± 0.10 | 1.800 | 0.072 |

| No | 2100 | 1.15 ± 0.07 | ||

| Insurance | ||||

| Medical insurance | ||||

| Have | 1404 | 1.05 ± 0.04 | ||

| Not have | 984 | 1.32 ± 0.06 | 3.985 | < 0.001 |

| Health status | ||||

| Satisfied with your health | ||||

| Yes | 2101 | 1.16 ± 0.04 | 0.305 | 0.761 |

| No | 287 | 1.14 ± 0.09 | ||

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 982 | 1.14 ± 0.05 | 0.442 | 0.658 |

| No | 1406 | 1.17 ± 0.04 | ||

| Drinking | ||||

| Yes | 689 | 1.52 ± 0.07 | 6.804 | < 0.001 |

| No | 1699 | 1.02 ± 0.04 | ||

CVD cardiovascular disease.

Correlation of social participation levels with health status, mood, and ability to perform activities of daily living in patients with CVD

To examine the associations between various characteristics and social participation in patients with CVD, relationships between social participation and health status, loneliness, depression, ADL, and IADL were analyzed. The values in the table represent the correlation coefficients between the variables, with a range from − 1 to 1. A coefficient near 1 signifies a strong positive correlation, while a coefficient near − 1 indicates a strong negative correlation. An asterisk denotes statistical significance. The results, as presented in Table 3, demonstrate positive correlations between social participation and health status (r = 0.113, P < 0.01), ADL (r = 0.159, P < 0.01), and IADL (r = 0.197, P < 0.01). These findings indicate that better health status, higher ADL scores, and elevated IADL scores are linked to increased social participation.

Table 3.

Correlation between health status, lonely, depression, ADL, IADL, and social activities (n = 2388).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Health status | 1 | |||||

| 2. Lonely | − 0.059** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Depressed | − 0.088** | 0.564** | 1 | |||

| 4. ADL | 0.317** | − 0.046** | − 0.056** | 1 | ||

| 5. IADL | 0.354** | − 0.054** | − 0.064** | 0.568** | 1 | |

| 6. Social activities | 0.113** | − 0.015 | − 0.045* | 0.143** | 0.188** | 1 |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Conversely, depression was negatively correlated with social participation (r = − 0.055, P < 0.01), suggesting that higher depression levels are associated with reduced social activity. This may be associated with the negative effect of a depressed mood on an individual’s social motivation and social competence. No statistically significant correlation was found between loneliness and social participation (P > 0.05). This suggests that the impact of loneliness on social participation among CVD patients was not significant in the present study sample. Further investigation into the underlying complex mechanisms or validation in other samples may be necessary.

Potential profile of social participation

A model was constructed to assess social participation, with model fit evaluated using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and sample-size adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC). The initial model was tested for one to four profiles of social participation to identify the optimal fit. The smaller the values of the three statistics-AIC, BIC, and aBIC-the better the model fit. The Entropy index ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating more accurate classification. Significant the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood test (LMR) and Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) values suggest that the n-category model provides a better fit than the n-1 category model. As shown in Table 4, AIC, BIC, and aBIC values consistently decreased as the number of profiles increased from one to four, suggesting improved model fit with smaller values. The entropy value, which ranges from 0 to 1 and measures classification accuracy, approached 1, indicating high classification accuracy. The P-value progressively decreased from the two-profile to the four-profile models. Following a comprehensive analysis, the four-profile model was determined to provide the best fit.

Table 4.

Fit indices for the latent profile models on Social participation.

| classes | AIC | BIC | SSABIC | Entropy | BLRT (p-value) |

Class Size (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2388 | 1 | 11,044.039 | 11,090.264 | 11,064.847 | |||

| 2 | 5165.395 | 5240.512 | 5199.208 | 1 | 0.3911 | 2141(89.7%), 247(10.3%) | |

| 3 | 2233.413 | 2337.421 | 2280.231 | 1 | 0.619 |

331(13.9%), 50(2.1%), 2007(84.0%) |

|

| 4 | 969.306 | 1102.204 | 1029.128 | 1 | 0.1499 |

162(6.8%), 331(13.9%), 1844(77.2%), 50(2.1%) |

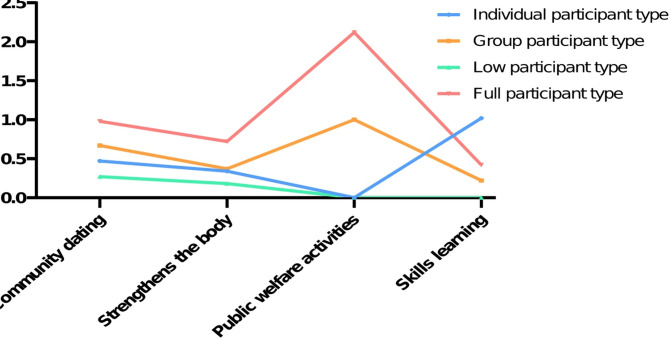

The study identified four distinct profiles of social participation among patients with CVD, as depicted in Fig. 1. Profile 1 exhibited the highest scores in the skills learning dimension, surpassing those in community dating, physical fitness, public welfare activities, and other forms of social participation. This profile was therefore categorized as the “Individual Participation Type.”

Fig. 1.

Plot of the standard deviation mean scores of social participation across the four identified latent profiles in the test sample.

Profile 2 showed elevated scores in public welfare activities, while community dating, physical fitness, and skills learning scored lower, earning it the designation of “Group Participation Type.”

Profile 3 demonstrated consistently low scores across all forms of social participation, and was accordingly labeled the “Low Participation Type.”

Profile 4, characterized by high scores across all categories, with public welfare activities being the highest, was classified as the “Comprehensive Participation Type.”

A detailed visualization of these profiles is provided in Fig. 1.

Variables scored in different potential social participation profiles

To assess the scores and differences in health status, loneliness, depression, ADL, and IADL across different patterns of social participation in patients with CVD, ANOVA was conducted for inter-group comparisons. The results indicated statistically significant differences in health status (P < 0.01), depression (P < 0.05), ADL (P < 0.0001), and IADL (P < 0.0001) across the social participation patterns, with F-values ranging from 1.197 to 20.58. However, no statistically significant differences were observed in loneliness (F = 1.197, P > 0.05). Detailed results are provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Variables score in different potential profiles of social participation.

| Individual participant type (n = 163) |

Group participant type (n = 331) |

Low participant type (n = 1844) |

Full participant type (n = 50) |

F | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health status | 2.79 ± 0.07 | 2.77 ± 0.05 | 2.60 ± 0.02 | 2.80 ± 0.13 | 4.843 | 0.001 |

| Lonely | 1.49 ± 0.07 | 1.62 ± 0.06 | 1.65 ± 0.02 | 1.68 ± 0.15 | 1.197 | 0.316 |

| Depression | 17.33 ± 0.50 | 18.90 ± 0.35 | 19.18 ± 0.05 | 17.96 ± 0.88 | 4.398 | 0.004 |

| ADL | 5.67 ± 0.06 | 5.64 ± 0.05 | 5.25 ± 0.03 | 5.60 ± 0.13 | 14.25 | < 0.0001 |

| IADL | 5.69 ± 0.07 | 5.37 ± 0.07 | 4.94 ± 0.04 | 5.50 ± 0.12 | 20.58 | < 0.0001 |

Comparison of general information characteristics of different potential profiles of social participation

To further investigate the patterns of social participation among patients with CVD, differences in characteristics such as demographics, region of residence, living arrangements, and health insurance coverage were analyzed. The results revealed no statistically significant differences in gender, marital status, or perceived health status (P > 0.05). However, statistically significant differences were found in education level, region of residence, living alone status, health insurance coverage, and alcohol consumption (P < 0.05). A comprehensive summary of these findings is provided in Table 6.

Table 6.

Characteristics of general data for different potential profiles.

| Variable | Individual participant type | Group participant type | Low participant type | Full participant type | χ 2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 81(49.7) | 167(50.4) | 825(44.7) | 23(46) | 4.079a | 0.194 |

| Female | 82(50.3) | 164(49.6) | 1019(55.3) | 27(54) | ||

| Educational level | ||||||

| Illiteracy | 24(14.7) | 68(20.5) | 391(21.2) | 10(20.0) | 30.612a | 0.000 |

| Primary education and below | 50(30.7) | 151(45.6) | 791(42.9) | 17(34.0) | ||

| Middle school | 48(29.4) | 66(19.9) | 404(21.9) | 15(30.0) | ||

| High School and above | 41(25.2) | 46(14.0) | 258(14.0) | 8(16.0) | ||

| Marriage | ||||||

| With spouse present | 137(84.0) | 263(79.5) | 1474(79.9) | 44(88.0) | 3.629a | 0.304 |

| Not living with spouse | 26(16.0) | 68(20.5) | 370(20.1) | 6(12.0) | ||

| Location of residential | ||||||

| City | 63(38.7) | 71(21.5) | 413(22.4) | 13(26.0) | 29.605a | 0.000 |

| Country | 100(61.3) | 260(78.5) | 1431(77.6) | 37(74.0) | ||

| Living alone | ||||||

| Yes | 30(18.4) | 47(14.2) | 205(11.1) | 5(10.0) | 9.386a | 0.025 |

| No | 133(81.6) | 284(85.8) | 1639(88.9) | 45(90.0) | ||

| Medical insurance | ||||||

| Have | 68(41.7) | 184(55.6) | 1132(61.4) | 20(40.0) | 33.435a | 0.000 |

| Not have | 95(58.3) | 147(44.4) | 712(38.6) | 30(60.0) | ||

| Satisfied with your health | ||||||

| Yes | 144(88.3) | 282(85.2) | 1628(88.3) | 47(94.0) | 4.323a | 0.229 |

| No | 19(11.7) | 49(14.8) | 216(11.7) | 3(6.0) | ||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 66(40.5) | 132(39.9) | 765(41.5) | 19(38.0) | 0.540a | 0.910 |

| No | 97(59.5) | 199(60.1) | 1079(58.5) | 31(62.0) | ||

| Drinking | ||||||

| Yes | 63(38.7) | 127(38.4) | 473(25.7) | 26(52.0) | 44.483a | 0.000 |

| No | 100(61.3) | 204(61.6) | 1371(74.3) | 24(48.0) | ||

achi-square test.

Logistic regression analysis of factors influencing social participation

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the impact of factors such as loneliness, depression, and ADL on social participation in patients with CVD. The latent profiles of patients with CVD served as the dependent variable, with the “Low Engagement Type” used as the reference profile. Depression, ADL, and IADL are treated as continuous and are brought into the multinomial logistic regression statistical analysis at their original values. Lonely, educational level are treated as dummy variables. Location of residential, living alone, medical insurance, and drinking are treated as as binary classification variable.

The analysis identified that depression, higher IADL, living in country, living alone, have medical insurance, alcohol consumption were significantly associated with classification under the “Individual Participation Type.” Higher ADL scores and alcohol consumption were linked to the “Group Participation Type.” Furthermore, have medical insurance and alcohol consumption was also significantly associated with the “Comprehensive Participation Type.” No statistically significant associations were found for other factors and profiles (P > 0.05). Detailed results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Logistic regression analysis of the influencing factors of social participation potential classification.

| Variable | b | Sb | Waldχ 2 | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual participant type | ||||||

| Constant | − 3.917 | 0.803 | 23.795 | 0.000 | ||

| Lonely | ||||||

| Rarely or none of the time = 000 | ||||||

| Some or a little of the time = 010 | 0.281 | 0.261 | 1.156 | 0.282 | 1.324 | 0.794–2.210 |

| Occasionally or a moderate amount of the time = 001 | 0.020 | 0.356 | 0.003 | 0.954 | 1.021 | 0.508–2.050 |

| Most of all of the time = 100 | 0.198 | 0.373 | 0.281 | 0.596 | 1.219 | 0.587–20,532 |

| Depression | − 0.038 | 0.017 | 4.759 | 0.029 | 0.936 | 0.931–0.996 |

| ADL | − 0.002 | 0.119 | 0.000 | 0.987 | 0.998 | 0.790–1.260 |

| IADL | 0.514 | 0.122 | 17.675 | 0.000 | 1.671 | 1.315–2.123 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Illiteracy = 000 | ||||||

| Primary education and below = 010 | − 0.067 | 0.260 | 0.067 | 0.795 | 0.935 | 0.562–1.555 |

| Middle school = 001 | 0.524 | 0.397 | 1.741 | 0.187 | 1.689 | 0.775–3.680 |

| High school and above = 100 | 0.710 | 0.642 | 1.223 | 0.269 | 2.034 | 0.578–7.161 |

| Location of residential | ||||||

| City = 0 | ||||||

| Country = 1 | − 0.380 | 0.191 | 3.944 | 0.047 | 0684 | 0.470–0.995 |

| Living alone | ||||||

| Yes = 0 | ||||||

| No = 1 | 0.478 | 0.224 | 4.575 | 0.032 | 1.613 | 1.041–2.501 |

| Medical insurance | ||||||

| Have = 0 | ||||||

| Not have = 1 | − 0.531 | 0.176 | 9.097 | 0.003 | 0.588 | 0.417–0.830 |

| Drinking | ||||||

| Yes = 0 | ||||||

| No = 1 | − 0.504 | 0.174 | 8.364 | 0.004 | 0.604 | 0.429–0.850 |

| Group participant type | ||||||

| Constant | − 3.154 | 0.496 | 40.487 | 0.000 | ||

| Lonely | ||||||

| Rarely or none of the time = 000 | ||||||

| Some or a little of the time = 010 | 0.347 | 0.179 | 3.747 | 0.053 | 1.415 | 0.996–2.010 |

| Occasionally or a moderate amount of the time = 001 | − 0.154 | 0.245 | 0.395 | 0.530 | 0.857 | 0.530–1.386 |

| Most of all of the time = 100 | 0.047 | 0.242 | 0.038 | 0.845 | 1.048 | 0.653–1.683 |

| Depression | − 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.187 | 0.665 | 0.995 | 0973–1.018 |

| ADL | 0.249 | 0.082 | 9.332 | 0.002 | 1.283 | 1.093–1.505 |

| IADL | 0.098 | 0.061 | 2.595 | 0.107 | 1.103 | 0.979–1.242 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Illiteracy = 000 | ||||||

| Primary education and below = 010 | 0.067 | 0.161 | 0.172 | 0.678 | 1.069 | 0.780–1.466 |

| Middle school = 001 | − 0.262 | 0.262 | 1.002 | 0.317 | 0.770 | 0.461–1.285 |

| High school and above = 100 | − 0.235 | 0.415 | 0.321 | 0.571 | 0.790 | 0.350–1.784 |

| Location of residential | ||||||

| City = 0 | ||||||

| Country = 1 | 0.107 | 0.158 | 0.457 | 0.499 | 1.112 | 00.817–1.515 |

| Living alone | ||||||

| Yes = 0 | ||||||

| No = 1 | 0.233 | 0.179 | 1.709 | 0.191 | 1.263 | 0.817–1.515 |

| Medical insurance | ||||||

| Have = 0 | ||||||

| Not have = 1 | − 0.210 | 0.125 | 2.806 | 0.094 | 0.811 | 0.634–1.036 |

| Drinking | ||||||

| Yes = 0 | ||||||

| No = 1 | − 0.540 | 0.127 | 18.086 | 0.000 | 0.583 | 0.455–0.748 |

| Full participant type | ||||||

| Constant | − 3.390 | 1.185 | 8.183 | 0.004 | ||

| Lonely | ||||||

| Rarely or none of the time = 000 | ||||||

| Some or a little of the time = 010 | 0.249 | 0.473 | 0.278 | 0.598 | 1.283 | 0.507–3.245 |

| Occasionally or a moderate amount of the time = 001 | 0.459 | 0.539 | 0.725 | 0.395 | 1.582 | 0.550–4.550 |

| Most of all of the time = 100 | 0.780 | 0.562 | 1.924 | 0.165 | 2.182 | 0.725–6.568 |

| Depression | − 0.045 | 0.030 | 2.267 | 0.132 | 0.956 | 0.901–1.014 |

| ADL | 0.044 | 0.189 | 0.054 | 0.817 | 1.045 | 0.721–1.514 |

| IADL | 0.246 | 0.169 | 2.115 | 0.146 | 1.279 | 0.918–1.781 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Illiteracy = 000 | ||||||

| Primary education and below = 010 | − 0.239 | 0.407 | 0.344 | 0557 | 0.787 | 0.354–1.749 |

| Middle school = 001 | 0.750 | 0.649 | 1.335 | 0.248 | 2.116 | 0.593–7.548 |

| High school and above = 100 | 0.695 | 1.054 | 0.435 | 0.510 | 2.003 | 0.254–15.792 |

| Location of residential | ||||||

| City = 0 | ||||||

| Country = 1 | 0.096 | 0.359 | 0.072 | 0.789 | 1.101 | 0.545–2.223 |

| Living alone | − 0.200 | 0.482 | 0.172 | 0.678 | 0.819 | 0.318–2.108 |

| Yes = 0 | ||||||

| No = 1 | ||||||

| Medical insurance | ||||||

| Have = 0 | ||||||

| Not have = 1 | − 0.831 | 0.303 | 7.506 | 0.006 | 0.435 | 0.240–0.789 |

| Drinking | ||||||

| Yes = 0 | ||||||

| No = 1 | − 1.102 | 0.292 | 14.265 | 0.000 | 0.332 | 0.187–0.588 |

b: Coefficient; Sb: Standard Error; Waldχ2: Wald Chi-Square; P: P-value; OR : odds ratio;

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval.

Discussion

This study utilized data from the CHARLS database to investigate the factors influencing social participation among patients with CVD. The findings indicated a significant association between social participation and factors such as health status, depression, ADL, and IADL. Similarly, a study conducted in the United States demonstrated that social participation enhances both physical and mental health, reduces the risk of CVD and mortality, and supports the maintenance of ADL and IADL27. This effect is attributed to the positive reinforcement individuals receive during social interactions, which facilitates recovery among patients with CVD28. Given these findings, healthcare professionals should actively encourage patients to engage in a variety of social activities. Such involvement helps patients maintain physical function and improve ADL and IADL, providing opportunities for social interaction. Moreover, these interactions may alleviate depression and anxiety while contributing to a reduction in the risk of CVD recurrence29.

The study also revealed that the presence of health insurance and alcohol consumption have a statistically significant (P < 0.05) influenced the level of social participation among patients with CVD. In line with previous research, health insurance status was positively associated with higher levels of social participation30. Patients without health insurance often experience limitations in their social interactions, including restricted access to diverse activities, which diminishes the breadth and depth of their social engagement31. Furthermore, moderate alcohol consumption was found to positively impact cardiovascular health, likely due to its role in facilitating social interactions and promoting psychological well-being within specific social and cultural contexts32. These findings underscore the importance of addressing health insurance coverage and considering the cultural dimensions of social behavior in efforts to promote engagement among patients with CVD. Additionally, the study found that health status, ADL, IADL, and social participation were positively correlated. Specifically, better health status and higher ADL and IADL scores were associated with greater levels of social participation. The correlation coefficients of the three factors with better health, higher ADL and IADL scores were greater than 0, indicating that these three factors had a positive impact on social participation. Previous research supports these findings, showing that enriched social participation enhances health status and ADL, thereby forming a mutually reinforcing relationship23. Health status and ADL significantly affect both the psychological and physical functioning of patients with CVD. Middle-aged and older adults with better psychological well-being are often more confident, proactive, and willing to engage in social activities, further promoting social participation. To facilitate this, society should prioritize regular medical checkups, disease prevention and treatment services, and rehabilitation training to improve ADL. For less capable older adults, tailored assistance can improve self-care abilities, indirectly promoting increased social participation. A study conducted in Japan found that moderate social participation significantly reduced the risk of IADL decline compared to non-participation33. Moreover, social participation helps maintain functional status, reducing the risk of functional limitations and IADL disability34. Therefore, healthcare professionals should prioritize comprehensive assessments of patients’ IADL abilities and implement targeted rehabilitation care. These interventions can assist patients in maintaining functional independence and foster greater social participation.

This study revealed a negative correlation between depression and social participation, indicating that higher levels of depression are linked to reduced social engagement. This study found that the correlation coefficient of depression factor was less than 0, which showed that this factor had a negative effect on social participation. Previous research has established that participation in social activities can reduce the risk of depression, with the effect being particularly pronounced when supported by social networks. Conversely, depression can exacerbate cardiovascular and metabolic disorders, worsen depressive symptoms, and further hinder social participation35,36. Given these dynamics, healthcare professionals should adopt an integrated approach that combines pharmacological treatments with socio-behavioral interventions. Strategies such as regular physical exercise, music therapy, and stress management can help prevent and alleviate depressive symptoms, while clinicians should actively monitor patients for signs of depression37. Furthermore, assessing patients’ satisfaction with daily life and their level of social participation can provide valuable insights into their mental health, enabling early intervention38. Such integrated care approaches can enhance psychological well-being, encourage social engagement, and improve the overall quality of life for patients.

The study also identified four latent profiles of social participation among patients with CVD: Individual Participation, Group Participation, Low Participation, and Full Participation. The largest group of patients was classified under the Low Participation type, characterized by low scores across all forms of social engagement. This pattern may be attributable to depressive symptoms and health limitations, where reduced physical functioning and psychological distress lead to social withdrawal39. Depressive symptoms can exacerbate cardiovascular conditions, thereby further reducing participation in social activities40. To address this, healthcare professionals should regularly monitor patients’ emotional well-being, design personalized social participation plans, and encourage emotional support connections with family and friends. The Full Participation type, which represented the smallest proportion of patients, demonstrated high scores across all types of social participation. This group typically had better health outcomes and was less affected by mood disturbances, which facilitated their engagement in various social activities. Active social participation not only promotes physical activity but also improves depressive symptoms, creating a positive feedback loop that enhances both physical and mental health41. Approximately 13.8% of patients were classified in the Group Participation type, characterized by higher scores in public welfare activities but lower scores in physical exercise and skill learning. This pattern may reflect the influence of physical limitations and psychological factors, where disease symptoms hinder physical activity and the perceived pressure of engaging in physical exercise or skill acquisition reduces motivation42,43. To enhance engagement, healthcare professionals could offer educational lectures and training on cardiovascular health to empower patients with knowledge, reduce fear, and encourage safe and appropriate physical activities. Patients in the Individual Participation type (6%) had higher scores in skill acquisition but lower scores in public welfare activities. This pattern may be linked to individual personality traits, as extroverted individuals or those with strong neighborhood cohesion are more likely to engage in community activities44. However, some patients in this group might exhibit greater independence or social anxiety, leading to lower participation in group-based activities. Their preference for independent learning may explain their higher engagement in skill acquisition. Tailored interventions that focus on each patient’s strengths, coupled with opportunities for safe and structured community interactions, could help this group expand their social participation.

In summary, the identification of distinct profiles of social participation offers critical insights for healthcare professionals to develop targeted strategies that promote engagement, enhance both physical and mental well-being, and ultimately improve the quality of life in patients with CVD. The results of this study demonstrate that better health status and a secondary school education level are significant factors influencing membership in the individual participation group. This suggests that CVD patients with these characteristics are more likely to be included in this category. Existing literature supports the notion that health status is positively correlated with social participation, as patients in better health typically demonstrate improved cognitive function, thereby facilitating independent involvement in social activities45. Moreover, education plays a pivotal role in fostering self-confidence and communication skills, both of which are essential for effective social participation46. Patients with higher ADL scores and alcohol consumption were more likely to be classified under “Group Participation” or “Full Participation.” Elevated ADL scores indicate superior self-care abilities, thereby increasing patients’ propensity to integrate into groups and engage in social activities47. Furthermore, alcohol consumption serves as a facilitator of social interactions, providing opportunities for individuals to engage more actively in collective activities48. In Chinese cultural contexts, moderate alcohol consumption is often ingrained in social practices, serving as a conduit for interpersonal communication. This cultural norm not only supports psychological well-being but also encourages group cohesion, thereby enhancing social participation49. These findings highlight the need for culturally sensitive, individualized interventions that promote social participation among patients with CVD. By addressing key factors such as health status, education, and lifestyle habits, healthcare providers can better facilitate improved health outcomes and a higher quality of life for these patients.

While this study provides valuable insights into the factors influencing and correlating with social participation in patients with CVD, several limitations must be considered. First, given its cross-sectional design, the study cannot establish causal relationships. Although associations were observed between social participation and various influencing factors, the directionality of these relationships remains indeterminate. Future research incorporating longitudinal data from the CHARLS, which includes multiple waves of data, could overcome this limitation, enabling a more thorough examination of the causal pathways between social participation and its determinants. Second, despite the broad representation of the elderly population across China in the CHARLS database, the sample may not fully capture the diversity of all older Chinese individuals, particularly those residing in remote areas or specific demographic groups. This limitation may affect the generalizability of the findings to the broader elderly population in China. Future studies would benefit from integrating more comprehensive datasets that include underrepresented populations, thereby providing a more accurate understanding of the broader determinants of social participation. By addressing these limitations, future research can offer a more nuanced understanding of the intricate interplay between social participation and the factors that influence patients with CVD, ultimately informing more effective intervention strategies.

Conclusion

This study analyzed data from the 2018 CHARLS database, classifying patients with CVD into four distinct profiles based on their scores across multiple dimensions of social participation: Individual Participation Type, Group Participation Type, Low Participation Type, and Full Participation Type. These profiles reveal unique characteristics of patients with CVD, offering valuable insights into their social participation behaviors. The findings demonstrated that social participation was positively correlated with health status, ADL, and IADL while showing a negative correlation with depression. Additionally, factors such as health status, educational level, ADL scores, and alcohol consumption emerged as significant determinants of social participation among patients with CVD across the different profiles. These results highlight the critical role of fostering positive emotions and enhancing patients’ self-care abilities. Healthcare professionals should prioritize recognizing individual variations among patients, including differences in self-care capacity and personality traits. By designing tailored social activities that consider these differences, healthcare providers can facilitate patients’ better integration into society, thereby improving their overall quality of life. Adopting such patient-centered approaches can encourage active participation, alleviate psychological distress, and ultimately contribute to improved long-term outcomes for patients with CVD.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all persons who agreed to participate to the study.

Abbreviations

- CHARLS

China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- IADL

Instrumental activities of daily living

- LPA

Latent profile analysis

Author contributions

X.L.Gao, T.Zhao designed the content of this study, X.L.Gao, S.L.Zhu, W.Y.Yang wrote the main manuscript text, T.Zhao, X.L.Gao and A.N.Ma drew the tables. L.N.Wang participated in data analysis and made adjustments to the format of the manuscript. The manuscript was examined by all the authors, and all authors are responsible for the content and have approved this final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Xinxiang Medical University Doctor Startup Fund (No.505431), Henan province humanities and social sciences research project (No.2024-ZZJH-300), Subject of educational science planning in Henan Province (2024JKZD18), Natural Science Foundation of Henan province (242300420113),Quzhou City Science and Technology Research Project (2024k124, 2024k120, 2024k121).

Data availability

The CHARLS datasets, which analysed during the current study, are publicly available at the National School of Development, Peking University (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en) and can be obtained after submitting a data use agree ment to the CHARLS team. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the CHARLS rounds was granted by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015), and all participants provided informed consent prior to their inclusion in the survey.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

ShuLin Zhu and WeiYe Yang contributed equally to this work.

These authors jointly supervised this work.

References

- 1.López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. & Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell186, 243–278 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang, J. C. & Bennett, M. Aging and atherosclerosis: mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence. Circ. Res.111, 245–259 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.China TWC of the R on CH and D. China cardiovascular health and disease report 2022 summary. Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Treatment. 23:1–19, 24 (2023).

- 4.Zhao, D., Liu, J., Wang, M., Zhang, X. & Zhou, M. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China: Current features and implications. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.16, 203–212 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth, G. A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.76, 2982–3021 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, X. et al. The path to healthy ageing in China: A Peking university–lancet commission. Lancet400, 1967–2006 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkisdóttir, M. B. et al. Unlike dietary restriction, rapamycin fails to extend lifespan and reduce transcription stress in progeroid DNA repair-deficient mice. Aging Cell20, e13302 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The importance of healthy lifestyle behaviors in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Tsuji, T. et al. Community-level group sports participation and all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality: A 7-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act.21, 44 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagargoje, V. P., James, K. S. & Muhammad, T. Moderation of marital status and living arrangements in the relationship between social participation and life satisfaction among older Indian adults. Sci. Rep.12, 20604 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, J., Rozelle, S., Xu, Q., Yu, N. & Zhou, T. Social engagement and elderly health in China: Evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal survey (CHARLS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health16, 278 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogelsang, E. M. Older adult social participation and its relationship with health: Rural-urban differences. Health Place42, 111–119 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maass, R., Kloeckner, C. A., Lindstrøm, B. & Lillefjell, M. The impact of neighborhood social capital on life satisfaction and self-rated health: A possible pathway for health promotion?. Health Place42, 120–128 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao, Y., Jia, Z., Zhao, L. & Han, S. The effect of activity participation in middle-aged and older people on the trajectory of depression in later life: National cohort study. JMIR Public Health Surveill.9, e44682 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu, C., Zhou, L. & Zhang, X. Effects of leisure activities on the cognitive ability of older adults: A latent variable growth model analysis. Front. Psychol.13, 838878 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, L. & Liu, W. Effects of family doctor contract services on the health-related quality of life among individuals with diabetes in China: Evidence from the CHARLS. Front. Public Health10, 865653 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong, X., Li, Y. & Simon, M. A. Social engagement among U.S. Chinese older adults: findings from the PINE Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci.69(Suppl 2), S82–S89 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, D. E. & Yoon, J. Y. Trajectory classes of social activity and their effects on longitudinal changes in cognitive function among older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.98, 104532 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly, M. E. et al. The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: A systematic review. Syst. Rev.6(1), 259 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu, D. S. et al. Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on loneliness among community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review, network meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Int. J. Nurs. Stud.144, 104524 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmes, E. A. et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry7, 547–560 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montero Mendoza, S. & Pelegrín Molina, M. A. Revisión de las escalas de valoración de las capacidades funcionales en la enfermedad de alzheimer. Fisioterapia32, 131–138 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma, X., Piao, X. & Oshio, T. Impact of social participation on health among middle-aged and elderly adults: Evidence from longitudinal survey data in China. BMC Public Health20, 502 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei, Z. Y., Jin, T. L. & Wuyun, T. N. Potential profiles and influencing factors of suicidal ideation among college students in Hohhot. Mod. Prevent. Med.48(11), 2010–2013 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu, H. Z. Principle and Technology of the Latent Class Model (Educational Science Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: The China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol.43, 61–68 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han, S. H., Tavares, J. L., Evans, M., Saczynski, J. & Burr, J. A. Social activities, incident cardiovascular disease, and mortality: Health behaviors mediation. J. Aging Health29, 268–288 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kianoush, S. et al. Association of participation in cardiac rehabilitation with social vulnerability index: The behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis.71, 86–91 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomioka, K., Kurumatani, N. & Hosoi, H. Association between social participation and instrumental activities of daily living among community-dwelling older adults. J. Epidemiol.26, 553–561 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaalema, D. E. et al. Financial incentives to increase cardiac rehabilitation participation among low-socioeconomic status patients. JACC Heart Fail.7, 537–546 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaalema, D. E. et al. Financial incentives to promote cardiac rehabilitation participation and adherence among Medicaid patients. Prev. Med.92, 47–50 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogunmoroti, O. et al. Alcohol type and ideal cardiovascular health among adults of the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Drug Alcohol. Depend.218, 108358 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomioka, K., Kurumatani, N. & Saeki, K. The differential effects of type and frequency of social participation on IADL declines of older people. PLoS ONE13, e0207426 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunningham, C., O’Sullivan, R., Caserotti, P. & Tully, M. A. Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci Sports30, 816–827 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, C. et al. The impact of internet device diversity on depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults in China: A cross-lagged model of social participation as the mediating role. J. Affect. Disord.368, 645–654 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chávez-Castillo, M. Exploring shared pharmacotherapeutics with cardiovascular disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Jiang, W. Depression and cardiovascular disorders in the elderly. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am.41, 29–37 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jönsson, M. & Siennicki-Lantz, A. Depressivity and mortality risk in a cohort of elderly men. A role of cognitive and vascular ill-health, and social participation. Aging Ment. Health24, 1246–1253 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, Y., Zhang, W., Ye, M. & Zhou, L. Perceived participation and autonomy post-stroke and associated factors: An explorative cross-sectional study. J. Adv. Nurs.77, 1293–1303 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bucciarelli, V. et al. Depression and cardiovascular disease: The deep blue sea of women’s heart. Trends Cardiovasc. Med.30, 170–176 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakagomi, A., Tsuji, T., Hanazato, M., Kobayashi, Y. & Kondo, K. Association between community-level social participation and self-reported hypertension in older Japanese: A JAGES multilevel cross-sectional study. Am. J. Hypertens.32, 503–514 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corrêa, V. P., De Oliveira, C. M., Vieira, D. S. R., Garcia, C. A. S. & Schneider, I. J. C. Socioemotional factors and cardiovascular risk: What is the relationship in Brazilian older adults?. Innov. Aging7, igad078 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkie, R. et al. Widespread pain and depression are key modifiable risk factors associated with reduced social participation in older adults: A prospective cohort study in primary care. Medicine (Baltimore)95, e4111 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hand, C. L. & Howrey, B. T. Associations among neighborhood characteristics, mobility limitation, and social participation in late life. J. Gerontol.: B.74, 546–555 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu, Y., Li, T., Ding, L., Cai, Z. & Nie, S. A predictive model for social participation of middle-aged and older adult stroke survivors: The China health and retirement longitudinal study. Front. Pub. Health11, 1271294 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou, H., Zhang, C., Wang, S., Yu, C. & Wu, L. Developmental trajectories and heterogeneity of social engagement among chinese older adults: A growth mixture model. BMC Geriatr.24, 846 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beltz, S., Gloystein, S., Litschko, T., Laag, S. & Van Den Berg, N. Multivariate analysis of independent determinants of ADL/IADL and quality of life in the elderly. BMC Geriatr.22, 894 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chai, X., Tan, Y. & Dong, Y. An investigation into social determinants of health lifestyles of canadians: A nationwide cross-sectional study on smoking, physical activity, and alcohol consumption. BMC Public Health24, 2080 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, J. et al. Impacts of alcohol consumption on farmers’ mental health: Insights from rural china. Heliyon10, e33859 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The CHARLS datasets, which analysed during the current study, are publicly available at the National School of Development, Peking University (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en) and can be obtained after submitting a data use agree ment to the CHARLS team. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request to the corresponding author.