Abstract

Confocal imaging and time-lapsed videomicroscopy were used to study the directionality, motility, rate of cell movement, and morphologies of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ (PI3K)γ−/− neutrophils undergoing chemotaxis in Zigmond chambers containing N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe gradients. Most of the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils failed to translocate up the cheomotactic gradient. A partial reduction in cell motility and abnormal morphologies were also observed. In the wild-type neutrophils, the pleckstrin homology domain-containing protein kinase B (AKT) and F-actin colocalize to the leading edge of polarized neutrophils oriented toward the gradient, which was not observed in PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils. In PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils, AKT staining consistently failed to perfectly overlap with the F-actin. This failure was observed as an F-actin-filled region of 2.3 ± 0.5 μm between AKT and the cell membrane. These data suggest that PI3Kγ regulates neutrophil chemotaxis primarily by controlling the direction of cell migration and the intracellular colocalization of AKT and F-actin to the leading edge.

The phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K) are evolutionarily conserved lipid kinases composed of a catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit that convert the phospholipid phosphotidylinositol-4′,5′-bisphosphate to phosphotidylinositol-3′,4′,5′-triphosphate (PIP3) (reviewed in ref. 1). They are involved in numerous cellular functions and responses (reviewed in refs. 2 and 3). Although p110α, -β, and -δ isoforms are activated by tyrosine kinases, the p110γ isoform is activated by the βγ complex of heterotrimeric G proteins (4). The PI3Kγ isoform is therefore activated by G protein-coupled receptors (5).

PIP3 has been proposed to act as a compass to control the direction of cell migration (reviewed in ref. 6). Recent studies using Dictyostelium mutants lacking pi3k1/2 suggest that PI3K1/2 are required for the spatiotemporal regulation of F-actin and the establishment of psuedopods toward chemotactic gradients (7). Directional control may occur through the binding of signaling molecules containing pleckstrin homology (PH) domains [such as the protein kinase B (AKT)] to PIP3. When expressed in the neutrophil-like HL60 cells, PHAKT-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (the PH domain of AKT kinase tagged with GFP) shows selective recruitment to the cell regions receiving the strongest N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) stimulation. These regions also showed F-actin polymerization and psuedopod formation (8).

The phenotypes of PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils have recently been studied (9–11). fMLP-induced adhesion (10, 11), F-actin polymerization (9), intracellular calcium release (9, 10), and Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis (11) were normal. In contrast, fMLP-induced superoxide production and activation of the protein kinases AKT and ERK1/2 were reduced (9–11). In the Boyden chamber chemotaxis assay, impaired neutrophil migration in response to IL-8 (10), fMLP (9–11), C5a (10, 11) and MIP-1α (9) were observed.

To better understand the nature of the chemotactic defects of PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils, we used confocal imaging and time-lapsed videomicroscopy to examine the directionality, migration speed, and morphologies of wild-type (WT) and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils undergoing chemotaxis in Zigmond chambers containing fMLP gradients. PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils showed frequent directional changes and failed to orient toward the gradient. The results suggest that PI3Kγ regulates neutrophil chemotaxis primarily by controlling the direction of cell migration.

Mateials and Methods

Materials.

PI3Kγ−/− and WT mice were prepared as described (9). The mice were housed at the University of Connecticut Health Center, and all experiments involving the mice were approved by the University of Connecticut Health Center Animal Care Committee. Zigmond chambers were purchased from Neuroprobe (Cabin John, MD). The following reagents were purchased: anti-AKT (rabbit polyclonal IgG) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; FITC or peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG from Jackson ImmunoResearch; slowfade and rhodamine phalloidin from Molecular Probes; crystalline BSA and fMLP from Sigma; enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagent from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ); and broad-range molecular weight markers from Bio-Rad.

Neutrophil Preparation and Zigmond Chamber Chemotaxis Assay.

Murine bone marrow neutrophils were prepared by centrifugation (1,800 × g) through Percoll gradients as described (11). Purified neutrophils were suspended in Hanks' buffer (0.14 M NaCl/5.4 mM KCl/1 mM Tris/1.1 mM CaCl2/0.4 mM MgSO4/1 mM Hepes, pH 7.2) containing 5 mg/ml of crystalline BSA. After isolation, cells were allowed to adhere to glass coverslips for 5 min at 37°C. The coverslips were then rinsed and placed on Zigmond chambers (12). Aliquots (0.1 ml) of a solution (Hanks' buffer containing a 1:10 dilution of 10% gelatin in H20) were added to one side of the chamber and the same solution containing fMLP (10−5 M) was added to the other side (12). Chambers were then used for either time-lapsed videomicroscopy or confocal microscopy as described below.

Videomicroscopy of Migrating Neutrophils.

Time-lapsed videomicroscopy was used to examine neutrophil movements in Zigmond chambers. In these chambers purified neutrophils were recorded crawling in the absence or presence of fMLP gradients. The microscope was equipped with differential interference contrast optics and a ×20 objective. Images were captured at 5-sec intervals with a PXL-EEV37 charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Photometrics, Waterloo, ON, Canada) and Metamorph (West Chester, PA) imaging software. The recorded data were used for analyses of neutrophil chemotaxis by using the Metamorph software.

Confocal Microscopy of Migrating Neutrophils and Immunofluorescence Staining of F-Actin and Protein Kinase AKT.

For indirect immunofluorescence, neutrophils were fixed in Zigmond chambers after being exposed to fMLP gradients for 15 min (13). Chemotaxis buffers were carefully removed from the chamber wells and immediately replaced with 2.4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at 37°C. The coverslips containing the cells were removed from the chamber and incubated with a solution of 0.1% lysolecithin in PBS containing 1% normal goat serum (Sigma) and Abs to AKT (1:100 dilution). After 30 min at room temperature, the cells were washed and incubated in lysolecithin/PBS containing FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ig and rhodamine-phalloidin. After this incubation, cells were washed, and coverslips were mounted with a drop of slowfade reagent (Molecular Probes). These samples were then examined by using a Zeiss confocal imaging system with a 25-μm pinhole (14). Excitation wavelengths of 488 and 568 nm and emission filters were used to detect FITC (515–520 nm) and rhodamine (590 nm).

Analyses of Neutrophil Chemotaxis.

(i) Construction of distribution plots and circular histograms.

Time-lapsed video images were used to calculate the final position of a neutrophil relative to its starting position and these data were graphed (15). On these graphs, a positive X distance reflects travel up the gradient. The absolute Y values represent lateral deviation along the gradient. From these graphs circular histograms were constructed to show the directionality of the neutrophil population during migration (15). This was done by dividing a circle around the origin into 36 contiguous sectors. Each sector was defined by a 10o angle emanating from the origin. The percentage of cells whose final position relative to a common origin was within each sector was then calculated and presented as circular histograms (Fig. 1 Inserts).

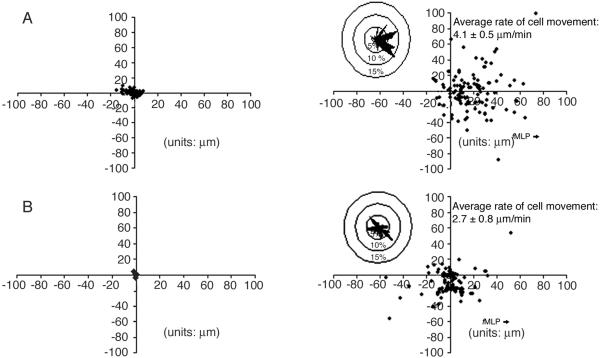

Figure 1.

Analysis of WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophil migration. Migration direction of WT (A) and PI3Kγ−/− (B) neutrophils during chemotaxis in fMLP gradients. Neutrophils were placed in Zigmond chambers containing buffer (Left) or gradients of fMLP (Right). Time-lapsed videomicroscopy was used to record the position of cells at 5-sec intervals on the bridge of the Zigmond chamber for 15 min. The final positions of neutrophils relative to a common origin was then plotted. The direction to wells containing the fMLP source is indicated. Average rates of cell movement were calculated based on the total movement of the cell centroid over 150 sec of observation. Inserts are circular histograms showing the percentage of cells whose final position was found within 1 of 36 sectors. These sectors were calculated as 10o angles emanating from the origin.

(ii) Motility and translocation measurements.

Time-lapsed videomicroscopy data were analyzed with the Metamorph software to determine cell motility (centroid movement over 5 sec) and cell translocation speed (total centroid movement over 150 sec) (16).

(iii) Calculating the time interval between direction changes.

The position, relative to a common origin, of chemotaxing neutrophils was plotted every 5 sec. These positions were connected by straight lines. Changes in direction were taken as turns in the path of greater than 45o relative to a straight line connecting the first and final positions.

(iv) Determination of the percentage of neutrophils translocating toward the chemotactic source.

Neutrophils that moved at least 15 μm over the 15 min of observation and had positive X coordinates were considered as translocating toward the fMLP source.

(v) Tracing of migrating neutrophil boundaries.

Images of neutrophils migrating in fMLP gradients at 75-sec intervals were used. Over these images, a new editing layer was added by using photoshop software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) and on this layer, the boundary of individual neutrophils was traced. Each successive tracing was assigned a graded color (generated with photoshop) ranging from red (initial tracings) to blue (final tracings).

Immunoblotting Analysis of AKT.

Neutrophils (2 × 105) were lysed with sample buffer, boiled, and resolved in 10% PAGE as described (17). Samples were then analyzed as immunoblots by using Abs to AKT (1:1000) followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ig (1:5,000). Bound Abs were visualized by using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system.

Chemokinesis in Boyden Chamber.

Boyden chamber assays were done as described (9). Chemokinesis was analyzed by the checkerboard assay as described (18).

Results

Analyses of Chemotactic Behaviors of PI3Kγ−/− Neutrophils.

Time-lapsed videomicroscopy was used to construct distribution plots for examining the migration pattern of WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils in Zigmond chambers containing either buffer (Fig. 1 A and B Left) or fMLP gradients (Fig. 1 A and B Right). The overall directionality of the neutrophil migration was quantitated by the construction of circular histograms (Fig. 1 A and B Inserts).

In the absence of fMLP gradients, only 7.3 ± 0.6% (n = 67) of WT neutrophils demonstrated translocation (i.e., movement of the centroid more than 15 μm over the 15 min of observation). In contrast, none of the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils (n = 55) showed translocation. In the presence of fMLP gradients, 76.7 ± 3% (n = 203) of the WT neutrophils demonstrated cell translocation, that is, their centroid moved at least 15 μm over the observation period of 15 min. In addition, as shown in the distribution plots of their final locations relative to their initial position (Fig. 1) and in Fig. 2B, 92% of the translocating neutrophils were moving toward the fMLP source. Likewise, 79.4 ± 2% (n = 195) of the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils showed translocation; however, of these only 61% were moving up the fMLP gradient (Figs. 1 and 2B). This value should be compared with an expected value of 50% if the cells were undergoing random migration.

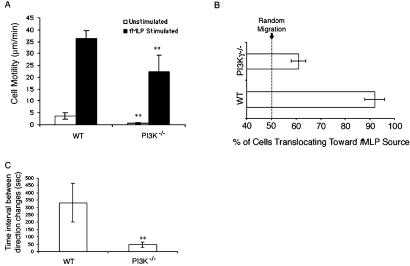

Figure 2.

Comparisons of chemotactic parameters between WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils. (A) The motility of WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils in Zigmond chambers containing buffer only or fMLP in one chamber. Motility was determined as the rate of movement of the centroid at each 5 sec of observation. (B) The percentage of cells showing translocation toward the fMLP source. (C) The time interval between turns of greater than 45o, calculated as described in Materials and Methods. **, indicates statistical significance (P < 0.0005) vs. WT.

Both WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils were motile, that is, their shapes changed as reflected by the movement of their centroids when examined over 5-sec intervals. The motility of the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils, however, was significantly reduced compared with WT (Fig. 2A).

Despite the reduced translocation speed, nearly all of the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils were moving. In fact, only 3% of either WT or PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils were immobile (data not shown). These nonmoving cells were not included in other analyses.

Chemokinesis Assay.

PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils showed a partial reduction in the Boyden chamber chemotaxis assay compared with WT cells (9–11). We examined whether the residual activity is because of chemokinesis by using a checkerboard assay (Table 1) (18). The results showed that although fMLP stimulated migration, the chemokinesis activities of WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils in Boyden chambers after stimulation with fMLP were indistinguishable.

Table 1.

Checkerboard Boyden chamber assay of neutrophil chemotaxis

| Neutrophils | WT | PI3Kγ−/− | WT | PI3Kγ−/− | WT | PI3Kγ−/− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMLP in Lower chamber | fMLP in Upper Chamber | |||||

| 0 μM | 0.2 μM | 2 μM | ||||

| 0 μM | 1 | 1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 1.9 |

| 0.2 μM | 2.9 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| 2 μM | 7.5 | 3.7 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.0 |

Data are presented as chemotactic indexes. The chemotactic indexes in wells containing no fMLP were taken as one (8). Highlighted boxes show chemotactic index obtained in chambers containing no fMLP gradient.

Morphologies of Migrating PI3Kγ−/− Neutrophils.

Cell boundaries of individual neutrophils were traced to define how the cells moved in the Zigmond chambers containing fMLP gradients (Fig. 3). Representative neutrophils from the fast- (WT >3 μm/min, PI3Kγ−/− > 1.5 μm/min; 52 and 47% of totals, respectively) and slow-moving (WT <3 μm/min, PI3Kγ−/− < 1.5 μm/min) neutrophils are shown in Fig. 3. The fast-moving WT neutrophils (Fig. 3A) moved by protrusion of lamellipodia and retraction of tails (19). With few turns the neutrophils were able to orient themselves toward the chemotactic source (Fig. 3A) (12). The slow-moving WT neutrophils (Fig. 3B) moved in a similar way, but the lamellipod protrusions did not reach as far as those of the fast-moving WT. In contrast, the fast-moving PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils (Fig. 3C) were able to make only small surface protrusions and these protrusions were all over the cell. The slow-moving PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils (Fig. 3D) remained near the origins and showed only slight surface protrusions.

Figure 3.

Tracings of WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophil boundaries during migration in fMLP gradients. The cell boundaries of translocating WT neutrophils [(A) fast-moving (>3 μm/min) and (B) slow-moving (<3 μm/min)] and translocating PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils [(C) fast-moving (>1.5 μm/min) and (D) slow-moving (<1.5 μm/min)]. PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils were traced at 75-sec intervals as described in the text.

Movies 1 and 2, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site (www.pnas.org), were made from time-lapse video images showing a representative fast-moving WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophil. Polarization of WT neutrophils was observed with the appearance of contraction waves (20), which moved down the cell from front to back in parallel to the direction of cell migration (figure 1 of ref. 20 and Movie 1). In the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils, the contraction waves were disrupted and failed to show a directional movement (Movie 2).

Confocal Images of AKT and F-Actin Staining in WT and PI3Kγ−/− Neutrophils.

Activation of PI3 kinase has been shown to be required for the translocation of AKT to the leading edges and the activation of kinase activity (21, 22). In contrast to the earlier hypothesis that PI3K may regulate actin polymerization (7), fMLP-induced actin polymerization, and Rac activation seems to be normal in the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils (10, 11). It would be interesting to compare the intracellular localization of F-actin and AKT in WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils undergoing chemotaxis.

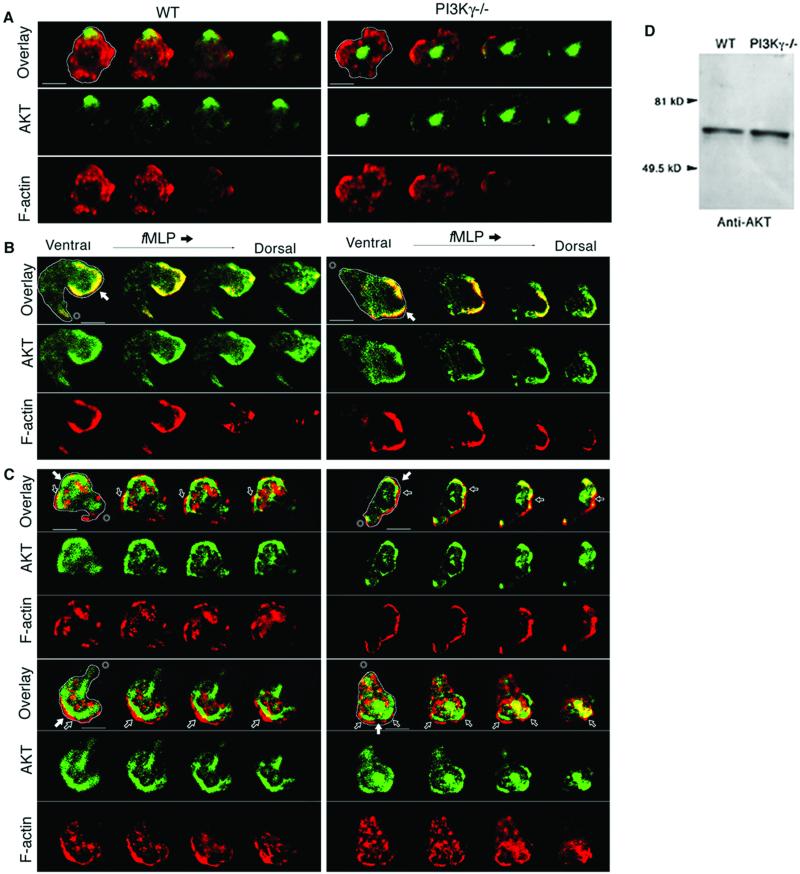

Confocal imaging was used to examine the staining patterns of F-actin and AKT in WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils with (Fig. 4 B and C) or without (Fig. 4A) fMLP stimulation. In the resting WT neutrophils, the AKT was found to be near the cell membrane and colocalized with a small portion of the total intracellular F-actin (Fig. 4A Left). In the resting PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils, AKT was found often to be in the central region of the cell and not colocalized with F-actin at all (Fig. 4A Right), but sometimes showed patterns similar to WT.

Figure 4.

Serial optical sections from confocal images of neutrophils fixed in Zigmond chambers containing buffer (A) or fMLP gradients (B and C). Serial sections 1 μm apart are shown from the ventral (left-most) through the dorsal (right-most) levels. In the first frame of each image, the outline of the cell body is shown in white. This outline was constructed by examining the F-actin staining pattern of the most-ventral image. Confocal images show the staining patterns of F-actin (Bottom, red), AKT (Middle, green), and both (Top, yellow) in neutrophils. (A) Confocal images from the ventral to dorsal plane (left to right) of resting neutrophils in Zigmond chambers lacking fMLP are shown. (B and C) Neutrophils undergoing chemotaxis in Zigmond chambers, the chemoattractant source was located to the right in each image. Two WT neutrophils are shown in B, and 4 PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils are shown in C. In all images, the reference bars are 10-μm long. In the overlay images, filled arrows indicate the apparent leading front while an asterisk marks the tail end (B and C). In PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils, open arrows show the location of imperfect overlap between F-actin staining and AKT staining. Three (Upper Left, Lower Left, and Lower Right) of the four neutrophils in C did not move toward the fMLP gradient but showed strong intracellular F-actin staining and imperfect overlap between F-actin staining and AKT staining. (D) The specificity of the anti-AKT Abs as judged by immunoblot analysis in WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils. Immunoblots were done by using the anti-AKT Abs as described in the text. The positions to which the molecular mass standards migrated are marked [crystalline BSA (81 kDa); Ovalbumin (49.5 kDa)].

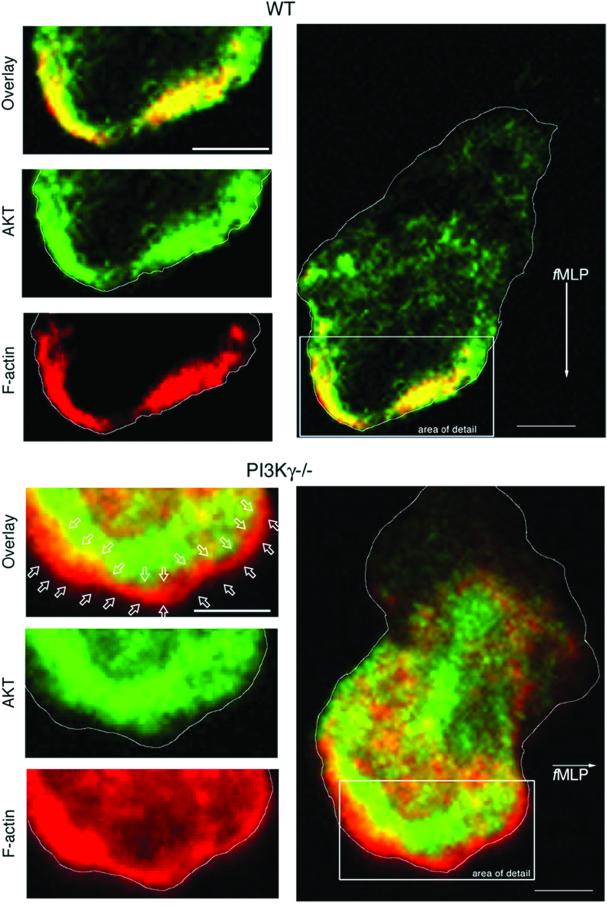

In the fMLP-stimulated WT neutrophils, AKT was found to colocalize with F-actin at the very leading front of migrating neutrophils especially at the ventral levels. Interestingly, at the dorsal level, AKT still localized to the leading front even though very little F-actin was detected (Fig. 4B, green images and overlay). This result suggests that AKT localization at the dorsal level does not require F-actin polymerization (23). Unlike the WT, the fMLP-stimulated PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils showed poor colocalization of F-actin and AKT at both ventral and dorsal levels (Fig. 4C, green images and overlay). In addition, at both the ventral and dorsal levels, strong F-actin staining was often observed intracellularly throughout the anterior, middle, and posterior regions of the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils (Fig. 4C, red images). This staining patttern was shown in three of the four neutrophils that were moving in a different direction from the gradient (Fig. 4C). Very often, there was a failure of the AKT to perfectly overlap the F-actin staining (Fig. 4). When measured, this left an average distance of 2.3 ± 0.5 μm (n = 40) of F-actin staining near the leading edge without AKT costaining (Fig. 4C). Immunoblots (Fig. 4D) showed that the anti-AKT Abs used in these studies recognize specifically the AKT kinase (molecular mass: 56 kDa) as has been reported by others (10, 11). To illustrate the gap more clearly, enlarged images of the leading fronts of both the WT and PI3Kγ−/− are shown in Fig. 5. Immunoblots (Fig. 4D) showed that the anti-AKT Abs used in these studies recognize specifically the AKT kinase (molecular mass: 56 kDa) as has been reported by others (9, 10).

Figure 5.

Enlarged images of the leading edges of WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils. Confocal images of neutrophils undergoing chemotaxis in Zigmond chambers containing fMLP gradients are prepared as described in the text. The staining patterns of F-actin (red), AKT (green), and overlays are shown. An imperfect overlap between the staining patterns of AKT and F-actin at the leading front in PI3Kγ−/− but not WT is indicated by open arrows. White tracings indicate the cell boundaries. Reference bars are 5-μm long, and a solid arrow is used to show the direction to the fMLP source.

Discussion

Previous analysis with Boyden chambers showed defects of chemotaxis in PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils. However, it is not clear whether the defect is on migration speed or directionality. In this report, we demonstrate that neutrophils lacking PI3Kγ are defective in migration directionality. This conclusion is supported by two lines of evidence. (i) The checkerboard migration test revealed PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils primarily underwent chemokinesis rather than chemotaxis (Table 1), and (ii) analysis of time-lapsed videomicroscopy data of WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils in Zigmond chambers containing fMLP gradients showed that many of the mutant neutrophils failed to migrate up the chemotactic gradient of fMLP (Fig. 1). They showed lower cell motility, poor translocation toward fMLP, and frequent changes in the direction of migration (Fig. 2).

The lack of directionality phenotype of PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils is unlikely to result from defects in cell adhesion or F-actin formation, because we and others found that fMLP-induced adhesion to fibronectin (10, 11), fibrinogen (data not shown), or crystalline BSA (data not shown) and F-actin formation (9) (data not shown) were similar in both WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils. In fact, the tracings of the cell outlines (Fig. 3) suggest that the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils are defective in their ability to stabilize and consolidate a leading edge. This result likely leads to the inability to maintain cellular translocation persistently in the direction of the fMLP gradient.

To understand the mechanism by which PI3Kγ-deficiency leads to the inability to persistently migrate up a chemotactic gradient, we examined the subcellular distribution of F-actin and AKT. In the absence of chemoattractants, the staining patterns of AKT and F-actin are similar in both PI3Kγ−/− and WT neutrophils (Fig. 4A). Although the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils often show AKT staining at the center of the cells, we also observed that some mutant neutrophils have AKT staining at one side of the cells as seen in the WT neutrophils. The difference between the WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils may correlate with the lack of cell translocation among nonstimulated PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils (Fig. 1).

Previous studies have shown that chemotactic cells are polarized, in which some proteins, including PH domain containing proteins (21, 24) and F-actin (25), are concentrated at the edges receiving highest concentrations of chemoattractants (8, 26, 27). Consistent with these previous observations, we found that AKT and F-actin are colocalized and concentrated at the leading edges of chemotactic WT neutrophils. However, such a distribution pattern of F-actin does not exist in the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils. Although some F-actin can still be seen at the leading edges, F-actin is apparently randomly distributed within PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils, being found in the anterior mid and posterior regions of PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils. This finding may explain the observation that PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils have more protrusions per cell than the WT cells (Fig. 2B). On first inspection, the distribution of AKT in the PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils seems less distinguishable from that in the WT cells. However, when F-actin staining was overlaid with AKT staining, a striking and consistent difference between WT and mutant cells was observed; there are imperfect overlaps between AKT staining and F-actin staining in the PI3Kγ−/− cells. It seems that AKT proteins are not localized at the plasma membrane in PI3Kγ−/− cells despite F-actin concentrated nearby. In other words, although AKT is concentrated near the cell membrane, often at the leading edge of movement, it remains 2.3 μm away from the protruding membrane. The mechanism of the imperfect overlap with F-actin at the leading edge remains unclear but ectopic PIP3 production is unlikely to be responsible because no PIP3 is produced by fMLP in buffer-suspended PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils (9, 10). However, it is possible that other isoforms of PI3 kinase may be activated in adherent PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils.

In fMLP-stimulated WT neutrophils, PIP3 was found to be localized at the very leading edge of migrating cells (figure 3C of ref. 6). Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that in fMLP-stimulated neutrophils, the function of PI3Kγ is to produce PIP3 at the leading edge. This localized PIP3 would recruit PH domain-containing proteins, such as AKT, to the cell membranes of the leading edge, which in turn causes the redistribution of some cellular proteins or machineries such as F-actin to provide the directionality for cell movement.

In summary, our results support the current model of leukocyte navigation by a compass-like mechanism requiring PIP3 (6). The localized production of PIP3 at the leading edges is apparently vital for directed and persistent movement, but not movement itself. The PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils, which lack fMLP-induced PIP3 (9), are able to move, but are unable to sense the chemotactic gradient, probably because PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils are unable to persistently stabilize a leading front. Without PIP3, AKT is not properly localized to a particular membrane location. Additionally, the total amount of actin polymerization and the kinetics of actin polymerization were not different when WT and PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils were compared (ref. 9 and data not shown). We cannot eliminate the possibility that PI3Kγ may have a minor role in modulation of cell movement, as PI3Kγ−/− neutrophils translocate slower than WT neutrophils. However, the conflicting polarization signals caused by PI3Kγ deficiency may also contribute the reduced translocation rates. Although our results suggest that recruitment of AKT to this region may have a major role in controlling directionality, the possible role of other PH domain-containing proteins (24) such as WASP and SCAR (28, 29) remains to be examined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Center for Biomedical Imaging Technology, University of Connecticut Health Center for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI20943 (to C.-K.H.) and GM54597 (to D.W.).

Abbreviations

- PI3Kγ

phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ

- fMLP

N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe

- WT

wild type

- PIP3

phosphotidylinositol-3′,4′,5′-triphosphate

- PH

pleckstrin homology

- AKT

protein kinase B

References

- 1.Vanhaesebroek G, Leevers S, Ahmadi K, Timms J, Katso R, Driscoll P, Woscholski R, Parker P, Waterfield M. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:535–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wymann M, Pirola L. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1436:127–150. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu D, Huang C, Jiang H. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2935–2940. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dekker L, Segal A. Science. 2000;287:982–985. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krugmann S, Hawkins P, Pryer N, Braselmann S. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17152–17158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rickert P, Weiner O, Wang F, Bourne H, Servant G. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:466–473. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01841-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funamoto S, Milan K, Meili R, Firtel R. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:795–809. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Servant G, Weiner O, Herzmark P, Balla T, Sedat J, Bourne H. Science. 2000;287:1037–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z, Jiang H, Xie W, Zuchuan Z, Smrka A, Wu D. Science. 2000;287:1046–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsh E, Katanaev V, Garlanda C, Azzonilo O, Pirola L, Silengo L, Sozzani S, Mantovani A, Altruda F, Wymann M. Science. 2000;287:1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sasaki T, Irie-Sasaki J, Jones R, Oliveira-dos-Santos A, Stanford W, Bolon B, Wakeham A, Itie A, Bouchard D, Kozieradzki I, et al. Science. 2000;287:1040–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zigmond S. Methods Enzymol. 1988;162:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)62064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannigan M, Zhan L, Ai Y, Huang C. J Leukocyte Biol. 2001;69:497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright S, Centonze V, Stricker S, DeVries P, Paddock S, Schatten G. Method Cell Biol. 1993;38:1–45. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60998-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen W, Zicha D, Ridley A, Jones G. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1147–1157. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Ishihara A, Theriot J, Jacobson K. Nature (London) 1993;362:167–171. doi: 10.1038/362167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labadia M, Zu Y, Huang C. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;59:116–124. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson P. Methods Enzymol. 1988;162:38–50. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)62061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zigmond S. J Cell Biol. 1978;77:269–287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.77.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson P, Haston W. Methods Enzymol. 1988;162:3–16. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)62059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parent C, Blacklock B, Froehlich W, Murphy D, Devreotes P. Cell. 1998;95:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meili R, Ellsworth C, Lee S, Reddy T, Mu H, Firtel R. EMBO J. 1999;18:2092–2105. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin T, Zhang N, Long Y, Parent C, Devreotes P. Science. 2000. 2871034–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Firtel R, Chung C. BioEssays. 2000;22:603–615. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200007)22:7<603::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Condeelis J. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:411–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janetopoulos C, Jin T, Devreotes P. Science. 2001;291:2408–2411. doi: 10.1126/science.1055835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Es S, Devreotes P. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:1341–1351. doi: 10.1007/s000180050374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miki H, Minura K, Takenawa T. EMBO J. 1996;15:5326–5335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowell C, Fumagalli L, Berton G. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:895–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.