Abstract

Background

Oncolytic adenoviruses (OAds) mediate superior antitumor effects both by inducing direct oncolysis and activating antitumor immunity. Previously, we developed a novel OAd fully composed of human adenovirus serotype 35 (OAd35). OAd35 efficiently killed a variety of human tumor cells; however, OAd35-mediated activation of antitumor immunity remains to be evaluated. In this study, we examined whether OAd35-induced activation of immune cells contributes to the antitumor effects of OAd35.

Methods

Tumor infiltration and activation of immune cells following intratumoral administration of OAd35 in tumor-bearing immune-competent and nude mice were analyzed. The involvement of immune cells in the tumor growth-suppression effects of OAd35 was evaluated in asialo GM1 (aGM1)+ cell-depleted mice. The key signals for the OAd35-mediated tumor infiltration of NK cells were examined in interferon (IFN) alpha and beta receptor subunit 1 (IFNAR1) knockout and toll-like receptor 9 knockout mice.

Results

OAd35 efficiently induced tumor infiltration of activated natural killer (NK) cells and T cells after intratumoral administration in B16 tumor-bearing mice. Depletion of aGM1+ cells, including NK cells and a portion of CD8+ T cells, significantly hindered the OAd35-mediated tumor growth suppression in C57BL/6J wild-type mice and BALB/c nude mice. In IFNAR1 knockout mice, OAd35-induced tumor infiltration of activated NK cells and OAd35-mediated tumor growth suppression were significantly attenuated.

Conclusions

These data described above suggested that immune cells, including aGM1+ cells, contributed to the antitumor effects of OAd35. OAd35 significantly promoted activation and tumor infiltration of NK cells. The type-I IFN signal was crucial for the OAd35-mediated tumor infiltration, activation of NK cells, and tumor growth suppression. These findings suggest that OAd35 is a promising cancer immunotherapy agent via its enhancement of the antitumor activities of immune cells.

Keywords: Oncolytic Virotherapy; Oncolytic Viruses; Immunity, Innate

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

An oncolytic virus mediates antitumor effects via not only direct oncolysis but also activation of antitumor immunity. We have previously developed a novel oncolytic adenovirus serotype 35 (OAd35), which can overcome the drawbacks of conventional OAd35. OAd35 mediated efficient tumor cell killing activities in various types of human cultured tumor cells; however, the involvement of OAd35-induced activation of immune cells in the antitumor effects of OAd35 remains to be elucidated, in spite of the previous findings that Ad35 efficiently activated innate immunity in human dendritic cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

We revealed that OAd35 significantly induced tumor infiltration of activated natural killer cells in both C57BL/6J mice and BALB/c nude mice. OAd35 efficiently suppressed the growth of subcutaneous tumors following intratumoral administration in a manner dependent on asialo GM1 (aGM1)+ cells. The type-I interferon signal played a critical role in the antitumor effects of OAd35.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

We have found that OAd35 mediated efficient antitumor effects in an aGM1+ cell-dependent manner. OAd35 is expected to become a promising cancer immunotherapy agent.

Background

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) are natural or genetically modified viruses that specifically infect and kill tumor cells without harming normal cells. Clinical trials using OVs have been conducted worldwide and have shown favorable results.1 2 The attractive feature of OVs is their ability to convert immunosuppressive “cold” tumors into immunologically active “hot” tumors by activating antitumor immunity. In addition to the replication-dependent direct oncolysis, OVs directly activate innate immunity in immune cells, including dendritic cells and macrophages, following phagocytosis of OVs in immune cells. Moreover, OV-mediated tumor cell lysis results in the release of not only tumor-associated antigens but also pathogen-associated molecular patterns, such as virus genome and damage-associated molecular patterns, including high mobility group box 13 and heat shock proteins,4 from tumor cells. The OV-induced immune responses described above lead to the activation of antitumor immunity.5,7 In preclinical and clinical trials, combination therapy of OVs and immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, exhibited superior therapeutic efficacies in various types of tumors.8 9

Among the various types of OVs, the oncolytic adenovirus (Ad) (OAd) is the type most widely used in clinical trials of OVs.10 11 Tumor-selective replication of OAd is often mediated by tumor-specific expression of the Ad E1 gene, which encodes proteins essential for Ad self-replication, using a tumor cell-specific promoter.12 Although more than 100 types of human Ad serotypes have been identified,13 almost all OAds are based on human Ad serotype 5 (Ad5) (OAd5). OAd5 has various advantages as an OV; however, two major concerns of OAd5—namely, the high seroprevalence in adults14 15 and the low expression of the primary infection receptor, coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor (CAR), on the malignant tumor cells16 17—may limit the therapeutic efficacy of OAd5. In order to overcome these concerns regarding OAd5, we previously developed a novel OAd fully composed of human Ad serotype 35 (Ad35) (OAd35).18 We chose Ad35 for the development of a novel OAd because while only 20% or fewer adults have anti-Ad35 antibodies19 20 and the Ad35 infection receptor, human CD46, is highly expressed on a variety of human tumor cells.21 22 OAd35 has been shown to evade pre-existing anti-Ad5 neutralizing antibodies and to kill both CAR-positive and CAR-negative tumor cells.18 Although OAd35 is a promising alternative OAd, whether OAd35 activates antitumor immunity remains to be determined. Previously, we and other groups reported that a replication-incompetent Ad35 vector more efficiently activated innate immunity in immune cells, including mouse bone marrow-derived dendritic cells, than an Ad5 vector.23,26 These findings led us to hypothesize that OAd35 efficiently activated innate immunity following administration, leading to efficient induction of antitumor immunity and antitumor effects.

In this study, we examined tumor infiltration and activation of immune cells following intratumoral administration of OAd35. Our results showed that OAd35 induced tumor infiltration of immune cells more efficiently than OAd5. In addition, OAd35 mediated efficient growth suppression of subcutaneous tumors in a manner dependent on asialo-GM1 (aGM1)+ cells, including natural killer (NK) cells and a portion of CD8+ T cells, after intratumoral administration. Type-I interferon (IFN) was shown to be highly involved in OAd35-mediated tumor growth suppression and tumor infiltration of NK cells. These data indicated that OAd35 is a novel immune cell-stimulating OV and is highly promising as a cancer immunotherapy agent.

Methods

Cells and viruses

H1299 (a human non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line) and B16 (a mouse skin melanoma cell line) cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin in a 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air environment. Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells (JCRB1348; JCRB Cell Bank, NIBIOHN, Osaka, Japan) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin in a 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air environment. HCT116 (a human colon cancer cell line) cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A Medium (Cytiva, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin in a 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air environment. Normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin in a 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air environment. OAd35 and OAd5 were previously produced.18 A replication-incompetent Ad35 vector expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Ad35-GFP) was previously prepared using pAdMS18CA-GFP.27

Mice

C57BL/6J mice and BALB/c nude mice (5–6 weeks, female) were purchased from Nippon SLC (Hamamatsu, Japan). IFN alpha and beta receptor subunit 1 (IFNAR1) knockout mice (5–6 weeks, C57BL/6 background) were previously obtained.28 Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) knockout mice (5–6 weeks, C57BL/6 background) were purchased from Oriental Yeast (Tokyo, Japan).

In vitro tumor cell lysis activities of OAds

B16 cells were seeded on a 96-well plate at 8.0×103 cells/well. On the following day, cells were infected with OAd35 at 500 and 1,000 virus particles (VP)/cell. Cell viabilities were measured by a WST-8 assay using a cell counting kit-8 solution (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) on the indicated day points.

In vivo antitumor effects of OAd35

H1299 cells (3×106 cells/mouse) mixed with matrigel (Corning, Corning, New York, USA), B16 cells (2×105 cells/mouse), LLC cells (1×106 cells/mouse) and HCT116 cells (3×106 cells/mouse) were subcutaneously injected into the right flank of 5–6 weeks old mice. When the tumors grew to approximately 5–6 mm in diameter, mice were randomly assigned into groups. OAd35 was intratumorally administrated to subcutaneous tumors at a dose of 2.0×109 VP/mouse on the indicated day points. The tumor volumes were measured every 3 days. The following formula calculated tumor volume: tumor volume (mm3)=a×b2×3.14×6–1, where a is the longest dimension, and b is the shortest. For depletion of aGM1+ cells, normal rabbit serum (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical) and anti-aGM1 antibody (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical) were intravenously administered every 4 days from day 0 at a dose of 30 µL/mouse. For the evaluation of the preventive effects of OAd35 on lung metastasis, normal rabbit serum (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical) and anti-aGM1 antibody (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical) were intravenously administered every 4 days from day 0. OAd35 was intratumorally administrated to subcutaneous B16 tumors on days 3 and 6. Then, B16 cells (5×105 cells/mouse) were intravenously injected into subcutaneous B16 tumor-bearing mice via tail vein on day 7. Following 14 days after intravenous injection of B16 cells, mice were sacrificed, and the lung was collected. The metastatic tumor colonies on the lung were counted.

Analysis of tumor infiltration and activation of immune cells following OAd administration

When the tumor volumes reached approximately 200 mm3, OAds were intratumorally administered to tumor-bearing mice at a dose of 2.0×109 VP/mouse on day 0 and day 3. The blood cells in the tumor were analyzed on day 4 and day 13 as follows; briefly, the tumors were surgically excised and incubated with type I collagenase (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, New Jersey, USA). Cell numbers were counted using Cellometer Auto T4 (Nexcelom Bioscience LLC, Lawrence, Massachusetts, USA). On day 4, cells were incubated with 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-Aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) viability staining solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-mouse CD3ε antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, California, USA), Pacific Blue-labeled anti-mouse CD45 antibody (BioLegend), phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-mouse CD49b (DX5) antibody (BioLegend), and allophycocyanin (APC)/cyanine7-labeled anti-mouse CD69 antibody (BioLegend) after treatment with a mouse FcR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). For analysis of CD8+ T cells, cells were incubated with Pacific Blue-labeled anti-mouse CD8α antibody (BioLegend), instead of PE-labeled anti-mouse CD49b antibody, after treatment with a mouse FcR blocking reagent on day 13. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using a MACSQuant Analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec). The data was analyzed using FlowJo Software (BD Life Sciences, Ashland, Oregon, USA). The gating strategy is shown in online supplemental figure 1.

Gene expression analysis in the tumors following OAd administration

OAds were intratumorally administered to tumor-bearing mice, as described above. The total RNA in the tumor was recovered using ISOGEN (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions on day 4. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from recovered RNA by a SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) analysis was performed using a StepOnePlus System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and THUNDERBIRD Next SYBR qPCR Mix reagents (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). The gene expression levels were normalized by the messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of a housekeeping gene, mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The sequences of the primers were described in online supplemental table 1.

OAd-mediated activation of human NK cells

Normal human PBMCs were seeded on a Nunclon Sphera-Treated 24-well plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 1.0×106 cells/well. PBMCs were infected with OAds at 100 VP/cell. After a 24 hours infection, PBMCs were labeled with PE-labeled anti-human CD56 (NCAM) antibody (BioLegend), FITC-labeled anti-human CD3 antibody (BioLegend), APC/cyanine 7-labeled anti-human CD69 antibody (BioLegend), and 7-AAD viability staining solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific), after treatment with a human FcR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec). Flow cytometric analysis was performed as described above. The gating strategy is shown in online supplemental figure 2.

OAd genome copy numbers in the tumors

OAd35 was intratumorally administered as described above. Tumors were surgically excised at 21 days after the first administration of the anti-aGM1 antibody. Total DNA in the tumors was isolated using DNAzol (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA). OAd35 genome copy numbers were quantitated by real-time PCR analysis as previously described.18

Statistical analyses

Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, Welch’s t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). Data are presented as means±SD or SE.

Results

OAd35-induced tumor infiltration of NK cells in human tumor-bearing nude mice

We previously reported that OAd35 attenuated the subcutaneous H1299 tumor growth as much or more efficiently than OAd5 in BALB/c nude mice (figure 1A).18 Then, in order to examine whether OAd35 induces tumor infiltration and activation of immune cells in nude mice, OAd35 was intratumorally administered to H1299 tumor-bearing BALB/c nude mice, followed by flow cytometric analysis (figure 1B). BALB/c nude mice possess functional NK cells at levels comparable to or higher than those in wild-type BALB/c mice.29 30 Intratumoral administration of OAd35 significantly increased the percentages of CD3ε−/DX5+ cells (total NK cells) and CD69+/DX5+ cells (activated NK cells) in H1299 tumors (figure 1C,D). The OAd35-mediated activation and tumor infiltration levels of mouse NK cells were significantly higher than those by conventional OAd5. OAd35 induced significant and efficient increases in the mRNA levels of interleukin (IL)-15, IFN-γ, perforin, and granzyme B, compared with those in the other groups (figure 1E). OAd35-mediated promotion of tumor infiltration of NK cells and tumor growth suppression was also found in subcutaneous HCT116 tumor-bearing BALB/c nude mice (online supplemental figure 3). These results indicated that OAd35 more efficiently induced activation and tumor infiltration of NK cells in nude mice than OAd5.

Figure 1. Tumor infiltration of activated NK cells after OAd35 administration in BALB/c nude mice. (A) H1299 tumor growth following OAd35 and OAd5 administration. OAd35 and OAd5 were intratumorally administered at a dose of 2.0×109 VP/mouse on the days indicated by arrows. Tumor volumes were expressed as the mean tumor volumes±SE (n=7) and analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. ****p<0.0001. This data was previously reported.18 (B) Experimental design for analysis of the tumor infiltration of activated NK cells following intratumoral injection of OAds in BALB/c nude mice bearing H1299 tumors. (C) Representative dot plots of CD3ε−/DX5+ cells in CD45+ cells (left panel) and CD69+/DX5+ cells in CD3ε-/CD45+ cells (right panel). (D) The percentages of CD3ε−/DX5+ cells in CD45+ cells (upper panel) and of CD69+/DX5+ cells in CD3ε−/CD45+ cells (lower panel) on day 4. Data are from a representative experiment from two independent experiments. (E) The messenger RNA expression levels of IL-15, IFN-γ, perforin, and granzyme B in the tumors following OAds administration. The gene expression levels were normalized by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. These data were expressed as the means±SE (n=5). One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons post hoc test was performed. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; n.s.: not significant (p>0.05). ANOVA, analysis of variance; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; i.t., intratumoral; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; NK, natural killer; OAd5, oncolytic adenovirus serotype 5; OAd35, oncolytic adenovirus serotype 35; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR; VP, virus particle.

Impact of immune cells on the antitumor effects and replication of OAd35 in nude mice

In order to examine the involvement of immune cells in the antitumor effects of OAd35, aGM1+ cells in nude mice were depleted by intravenous injection of anti-aGM1 antibodies, followed by intratumoral administration of OAd35 (figure 2A). NK cells and a portion of CD8+T cells are positive for aGM1.31 32 In the presence of aGM1+ cells, intratumoral administration of OAd35 resulted in significant suppression of the subcutaneous H1299 tumor growth (figure 2B). Conversely, aGM1+ cell depletion clearly canceled the tumor growth inhibition of OAd35. These results indicated that aGM1+ cells filled an essential role in the tumor growth suppression effects of OAd35 in immune-incompetent mice.

Figure 2. Impact of NK cells on the antitumor effects of OAd35 in BALB/c nude mice. (A) Experimental schedule for analysis of the involvement of NK cells in the H1299 tumor growth suppression levels by intratumorally administered OAd35 in BALB/c nude mice. (B) H1299 tumor growth following OAd35 administration. The arrows indicate the days of OAd35 injection. These data were expressed as the means±SE (PBS: n=5; OAd35: n=7). Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test was performed. ****p<0.0001. (C) The OAd35 genome copy numbers in the tumors following OAd35 administration. The OAd35 genome copy numbers in the tumor were determined by quantitative PCR analysis at day 21. These data were expressed as the means±SE (PBS: n=5; OAd35: n=7). One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test was performed. *p<0.05. aGM1, asialo-GM1; ANOVA, analysis of variance; i.t., intratumoral; i.v., intravenous; NK, natural killer; OAd35, oncolytic adenovirus serotype 35; qPCR, quantitative PCR; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; VP, virus particle.

Next, in order to examine the virus replication levels in the tumors, the OAd35 genome copy numbers in the tumor were measured by quantitative PCR analysis at 21 days after the first administration of anti-aGM1 antibodies (figure 2C). The results showed that aGM1+ cell depletion significantly increased the OAd35 genome copy numbers in H1299 tumors by approximately 80-fold compared with those in the tumors of naïve serum-treated mice.

In order to further examine whether OAd35 replication in the tumors is crucial for OAd35-mediated tumor growth suppression, a replication-incompetent Ad35-GFP was intratumorally administered. OAd35 more efficiently suppressed the tumor growth than Ad35-GFP (online supplemental figure 4), indicating that OAd35 infection in H1299 tumors was important for the OAd35-mediated growth suppression of subcutaneous H1299 tumors following intratumoral administration.

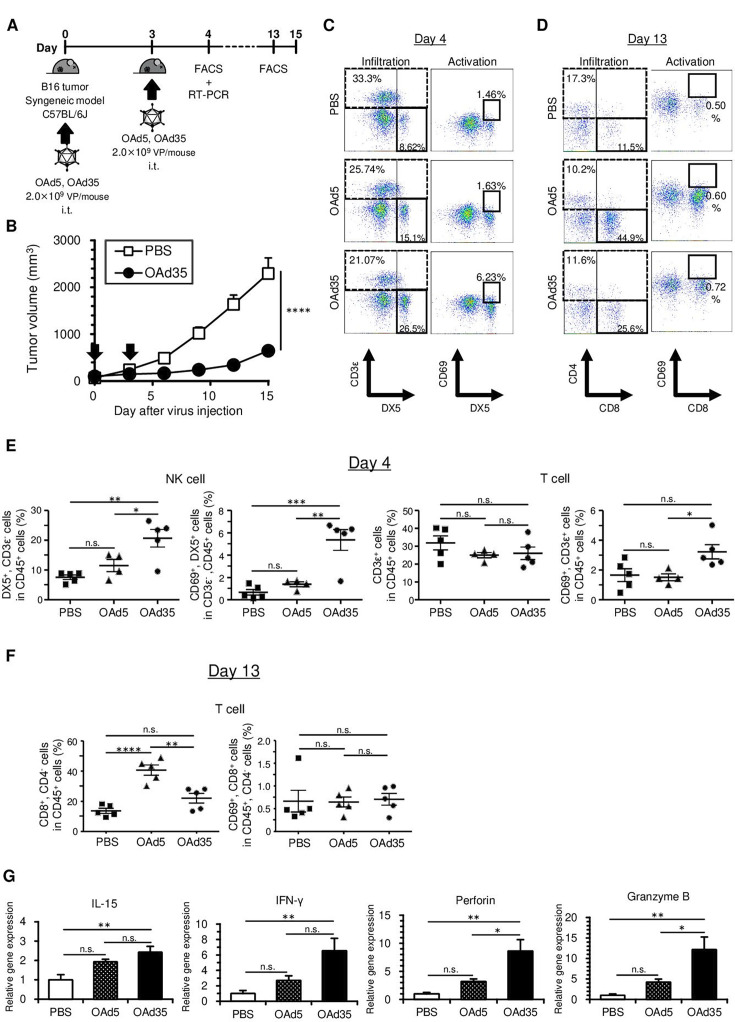

Immune cell activation in the tumors following OAd35 administration in immune-competent mice

In order to examine whether OAd35 induces tumor infiltration and activation of immune cells in immune-competent mice, OAd35 was intratumorally administered to B16 tumor-bearing C57BL/6J mice (figure 3A). OAd5 was also intratumorally administered as a control. OAd35 markedly inhibited B16 tumor growth following intratumoral administration (figure 3B), although OAd35 did not significantly mediate in vitro oncolysis in B16 cells (online supplemental figure 5). The percentages of CD3ε−/DX5+ cells (total NK cells) and CD69+/DX5+ cells (activated NK cells) were significantly increased by intratumoral injection of OAd35 on day 4 (figure 3C and E). CD69 expression on CD3ε+ T cells in the tumors was significantly higher following administration of OAd35 than following administration of OAd5, although the percentages of CD3ε+ T cells in the tumors were not significantly increased on day 4 (figure 3D,E). OAd5 less efficiently induced tumor infiltration of activated NK cells or T cells in B16 tumor-bearing mice than OAd35 on day 4. However, OAd5 significantly promoted tumor infiltration of CD8+ T cells on day 13. On the contrary, OAd35 did not mediate statistically significant enhancement of tumor infiltration of CD8+ T cells on day 13 (figure 3F). The percentages of CD69+/CD8+ T cells (activated CD8+ T cells) in the tumors were not significantly elevated following OAd35 or OAd5 administration on day 13. These results suggested that OAd35 efficiently promoted the tumor infiltration of activated NK cells and T cells after intratumoral administration, especially on the earliest measurement time points (day 4).

Figure 3. OAd35-mediated immune cell activation in C57BL/6J mice. (A) Experimental scheme for analysis of tumor infiltration of immune cells following intratumoral injection of OAds in C57BL/6J mice bearing B16 tumors. (B) B16 tumor growth following OAd35 administration. OAd35 was intratumorally administered at a dose of 2.0×109 VP/mouse on the days indicated by arrows. Tumor volumes were expressed as the mean tumor volumes±SE (n=8) and analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. ****p<0.0001. (C) Representative dot plots of tumor-infiltrated NK cells (CD3ε−/DX5+ cells) and T cells (CD3ε+ cells) (left panel) and tumor-infiltrated activated NK cells (CD69+/CD3ε−/DX5+ cells) (right panel) following OAds administration. Blood cells in the tumors were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 4. (D) The dot plots of tumor-infiltrated CD8+ T cells (left panel) and CD69+/CD8+ cells (right panel) 10 days after the first OAds administration. The data are representative of two independent experiments. (E) The percentages of tumor-infiltrated NK cells and activated NK cells and tumor-infiltrated T cells and activated T cells on day 4. The data were expressed as the means±SE (PBS, OAd35: n=5; OAd5: n=4). (F) The percentages of tumor-infiltrated NK cells and activated NK cells and tumor-infiltrated CD8+ T cells and activated CD8+ T cells on day 13. The data were expressed as the means±SE (n=5). Data are from a representative experiment from two independent experiments. (G) The messenger RNA levels of IL-15, IFN-γ, perforin, and granzyme B in the tumors following OAds administration. The gene expression levels were normalized by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. These data were expressed as the means±SE (n=5). One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons post hoc test was performed. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; n.s.: not significant (p>0.05). ANOVA, analysis of variance; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; i.t., intratumoral; NK, natural killer; OAd5, oncolytic adenovirus serotype 5; OAd35, oncolytic adenovirus serotype 35; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR; VP, virus particle.

OAd35-mediated promotion of tumor infiltration of NK cells and tumor growth suppression was also found in subcutaneous LLC tumor-bearing immune-competent mice (online supplemental figure 6). In addition, approximately fourfold higher levels of CD69+ human NK cells in human PBMCs were found following incubation of human PBMCs with OAd35, compared with incubation with OAd5 (online supplemental figure 7). The mRNA expressions of IFN-γ, perforin, and granzyme B, which were highly expressed in activated NK cells and CD8+ T cells,33 34 and IL-15 mRNAs, which were mainly produced by myeloid cells and were involved in the activation of NK cells and CD8+ T cells,35 36 in the tumors were significantly increased by intratumoral administration of OAd35 (figure 3G). These results indicated that OAd35 enhanced the tumor infiltration of immune cells, including activated NK cells, and significantly inhibited tumor growth in a virus infection-independent manner.

Attenuation of OAd35-mediated tumor growth suppression in aGM1+ cell-depleted mice

In order to examine the involvement of immune cells in OAd35-mediated tumor growth suppression in immune-competent mice, anti-aGM1 antibodies were administered before intratumoral administration of OAd35 to remove immune cells, including NK cells and a portion of CD8+ T cells from the mice. aGM1 is known to be expressed on not only NK cells but also a portion of CD8+ T cells.31 32 Previous studies demonstrated that approximately 20–30% of splenic CD8+ T cells were aGM1-positive.37 38 OAd35-mediated suppression of B16 tumor growth was completely canceled from the early day points (figure 4A,B). These results suggested that aGM1+ cells contributed to OAd35-mediated tumor growth suppression in B16 tumors. These results indicated that aGM1+ cells, including NK cells and a portion of CD8+ T cells, played a vital role in OAd35-mediated antitumor effects.

Figure 4. The tumor growth suppression levels of OAd35 in NK cell-depleted or CD8+ T cell-depleted C57BL/6J mice. (A) Experimental strategy for analysis of the antitumor effects of OAd35 in NK cell-depleted C57BL/6J mice bearing B16 tumor by anti-aGM1 antibodies. (B) B16 tumor growth following OAd35 administration in naïve serum-pretreated and anti-aGM1 antibody-pretreated mice. The arrows indicate the days of OAd35 injection. The tumor volumes were expressed as the means±SE (PBS: n=6; OAd35: n=8). Two-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test was performed. ****p<0.0001. aGM1, asialo-GM1; i.t., intratumoral; i.v., intravenous; NK, natural killer; OAd35, oncolytic adenovirus serotype 35; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; VP, virus particle.

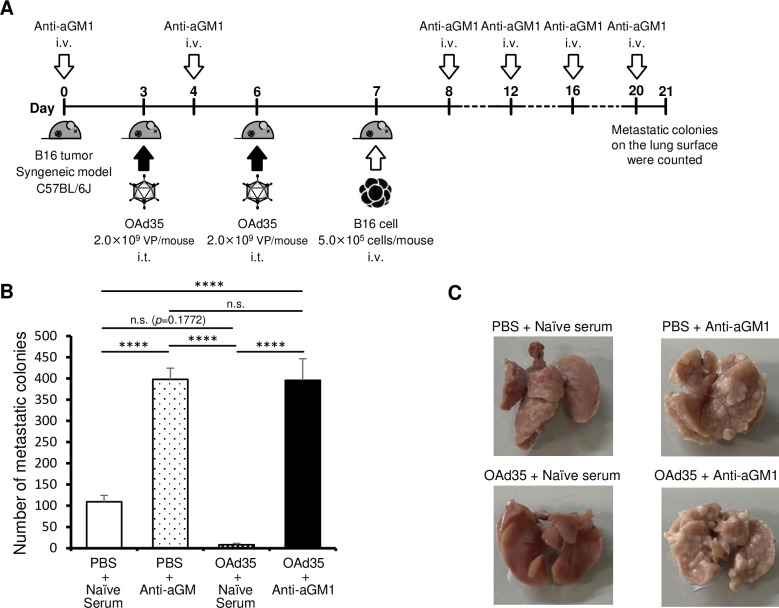

Next, in order to examine the aGM1+ cell-dependent preventive effects of OAd35 on lung metastasis, B16 cells were intravenously injected 1 day after intratumoral administration of OAd35 in subcutaneous B16 tumor-bearing mice pretreated with anti-aGM1 antibody and control serum (figure 5A). aGM1+ cells were highly involved in the inhibition of lung metastasis of B16 cells (figure 5B,C).29 39 Although there were no statistically significant differences between the naïve serum-treated PBS-administered and OAd35-administered groups, the average numbers of metastatic colonies in the lung were greatly decreased by OAd35 administration. The numbers of metastatic colonies in the lung were significantly restored by treatment with anti-aGM1 antibodies. These results indicated that aGM1+ cells played a key role in the antitumor effects of OAd35 in B16 tumor-bearing mice, including lung metastatic model mice.

Figure 5. Inhibition of B16 lung metastasis after OAd35 administration. (A) Experimental design to analyze the suppressive effects of intratumorally administered OAd35 on B16 lung metastasis. (B) The numbers of B16 metastatic colonies on the lung surface following OAd35 administration with or without pretreatment with anti-aGM1 antibody. These data were expressed as the means±SE (PBS: n=6–8; OAd35: n=6). One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons post hoc test was performed. ****p<0.0001; n.s.: not significant (p>0.05). (C) Representative images of the lungs from the PBS and OAd35 administration groups. aGM1, asialo-GM1; i.t., intratumoral; i.v., intravenous; OAd35, oncolytic adenovirus serotype 35; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; VP, virus particle.

Contribution of the type-I IFN signal to OAd35-mediated NK cell activation and tumor growth inhibition

To examine the contribution of the type-I IFN signal to OAd35-mediated tumor infiltration of activated NK cells and tumor growth suppression, OAd35 was intratumorally administered to IFNAR1 knockout mice bearing B16 tumors (figure 6A). In IFNAR1 knockout mice, there was no apparent tumor infiltration of NK cells following intratumoral administration of OAd35 (figure 6B,C). The CD69 expression levels on NK cells in the B16 tumors were comparable in PBS-administered and OAd35-administered IFNAR1 knockout mice. The mRNA expression levels of IL-15, IFN-γ, perforin, and granzyme B in the tumors were not significantly increased following OAd35 administration in IFNAR1 knockout mice (figure 6D). No growth suppression of B16 tumors was apparent following OAd35 administration in IFNAR1 knockout mice (figure 6E). These results indicated that OAd35 recruited activated NK cells into the tumors and mediated tumor growth suppression in a type-I IFN-dependent manner.

Figure 6. The role of the type-I IFN signal on OAd35-mediated tumor infiltration of NK cells and antitumor effects. (A) Experimental strategy for analysis of the involvement of the type-I IFN signal in NK cell infiltration following intratumoral injection of OAd35 in IFNAR1 knockout mice. (B) Representative dot plots of CD3ε−/DX5+ cells in CD45+ cells (left panel) and CD69+/DX5+ cells in CD3ε−/CD45+ cells (right panel) in the tumors. (C) The percentages of CD3ε−/DX5+ cells in CD45+ cells (upper panel) and CD69+/DX5+ cells in CD3ε−/CD45+ cells (lower panel) in the tumors on day 4. Data are from a representative experiment from two independent experiments. (D) The messenger RNA expression levels of IL-15, IFN-γ, perforin, and granzyme B in the tumors following OAd35 administration. The gene expression levels were normalized by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. These data were expressed as the means±SE (n=5). Data were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. n.s.: not significant (p>0.05). (E) OAd35 was intratumorally administered at a dose of 2.0×109 VP/mouse on the days indicated by arrows. Tumor volumes were expressed as the mean tumor volumes±SE (n=8) and analyzed by two-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. n.s.: not significant (p>0.05). FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; IFN, interferon; IFNAR1, IFN alpha and beta receptor subunit 1; IL, interleukin; NK, natural killer; OAd35, oncolytic adenovirus serotype 35; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR; VP, virus particle.

Involvement of the TLR9 signal in OAd35-mediated tumor infiltration of NK cells

To examine the involvement of the TLR9 signal in OAd35-mediated activation and tumor infiltration of NK cells, OAd35 was intratumorally administered to TLR9 knockout mice bearing B16 tumors (online supplemental figure 8A). A previous study demonstrated that TLR9 was involved in Ad35-induced innate immune responses.24 The percentages of CD3ε−/DX5+ cells (total NK cells) in the B16 tumors were not significantly increased by intratumoral injection of OAd35 in TLR9 knockout mice, although the percentages of CD69+/DX5+ cells (activated NK cells) in OAd35-treated mice were significantly higher than those in PBS-treated mice (online supplemental figure 8B,C). Significant elevations in the mRNA expression levels of IL-15, IFN-γ, perforin, and granzyme B in the tumors were found following OAd35 administration in TLR9 knockout mice (online supplemental figure 8D). While OAd35 did not induce NK cell infiltration, intratumoral administration of OAd35 significantly suppressed B16 tumor growth in TLR9 knockout mice (online supplemental figure 8E). These results indicated that the TLR9 signal was involved in the OAd35-mediated tumor infiltration of NK cells, but not in the activation and antitumor effects of OAd35.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to reveal the mechanisms of OAd35-mediated tumor growth suppression following intratumoral administration in subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice. The previous studies demonstrated that the antitumor effect of OAd5 is mediated by CD8+ T cells rather than virus proliferation.40 41 However, since OAd35 strongly attenuated the growth of subcutaneous H1299 tumors in BALB/c nude mice that hardly have CD8+ T cells, we first focused on NK cells on OAd35-mediated antitumor effects. The results showed that NK cells were efficiently activated and recruited to tumors following OAd35 administration in both immune-competent and nude mice (figures1C, D, 3C E). OAd5 mediated significantly lower levels of tumor infiltration of NK cells than OAd35. Previous studies reported that tumor infiltration and activation levels of NK cells were highly related to cancer metastasis, malignancy, and development rates in mouse models and patient cohorts.42,46 In addition, tumor infiltration levels of NK cells correlated well with the survival rates of patients with head and neck cancer.47 Hence, NK cells have been gaining much attention as a key player in cancer immunotherapy.48 49 Promotion of tumor infiltration and activation of NK cells are both highly important for OV-mediated cancer therapy.50 Other OVs, including reovirus51 and herpesvirus,52 also enhanced the tumor infiltration and activation of NK cells following administration and showed efficient antitumor effects in clinical trials.

Although administration of anti-aGM1 antibody to the nude mice significantly increased the OAd35 genome copy numbers in the tumors, OAd35 did not suppress the H1299 tumor growth in the absence of several types of immune cells, including NK cells (figure 2B,C). We previously demonstrated that OAd35 efficiently replicated in H1299 cells in vitro, leading to efficient lysis of H1299 cells following infection.18 Probably, OAd35-mediated activation of antitumor immunity made a greater contribution to the tumor growth suppression following administration than virus replication-mediated tumor cell lysis. In order to achieve efficient therapeutic effects of OAd35 in patients with cancer, it is important to examine whether NK cells are efficiently activated by OAd35 in patients with cancer rather than whether OAd35 efficiently replicates in the cancer cells of patients.

In our present experiments, OAd35-mediated B16 tumor growth suppression was completely canceled in IFNAR1 knockout mice (figure 6), indicating that type-I IFN signaling was indispensable for the antitumor effects of OAd35. It is well known that type I IFNs not only mediate direct growth inhibition on tumor cells but also play a crucial role in not only direct antitumor immunity.53 54 Immune cells, including CD8+T cells and NK cells, were significantly expanded by type I IFNs.55 In addition, OAd35 did not appear to induce NK cell recruitment into the tumor in IFNAR1 knockout mice or TLR9 knockout mice (figure 6 and online supplemental figure 8). These data indicated that TLR9 and type-I IFN signaling were crucial for the OAd35-mediated tumor infiltration of NK cells. Based on all the above, we can now consider the following hypothesis in regard to the mechanism of OAd35-mediated NK cell recruitment. First, OAd35 induced type-I IFN production in immune cells, including dendritic cells and macrophages, in a TLR9-dependent manner following administration. Previous studies demonstrated that wild-type Ad35 and a replication-incompetent Ad35 vector more efficiently induced type-I IFN production in dendritic cells than wild-type Ad5 and a replication-incompetent Ad5 vector.24,26 Next, type-I IFN efficiently activated NK cells. Type-I IFN is known to be a potent activator of NK cells.56 57 The activated NK cells, in turn, may contribute to the antitumor effect of OAd35. It remains to be examined whether NK cells are directly involved in the antitumor effect of OAd35 in future studies.

There was no apparent recruitment of the activated NK cells in H1299 and B16 tumors following OAd5 administration (figures1D 3E). In addition, the mRNA levels of IFN-γ, perforin and granzyme B in the tumors were not significantly elevated following OAd5 administration in tumor-bearing mice (figures1E 3G). These data suggested that OAd5 less efficiently activated innate immunity following administration compared with OAd35. Wild-type Ad35 and a replication-incompetent Ad35 vector induced higher amounts of type-I IFN production than wild-type Ad5 and a replication-incompetent Ad5 vector in cultured dendritic cells.25 We consider that the differences in the activation levels of innate immunity between Ad5 and Ad35 were partially due to the differences in intracellular trafficking. Because the amounts of Ad35 enclosed in late endosomes were higher than the corresponding amounts of Ad5,58 Ad35 should have more chances to interact with TLR9 in the endosomes. Further investigations into the differences among these immune profiles will contribute to the future design of immune-stimulating medicines.

It was reported that anti-aGM1 antibodies depleted several types of immune cells, including a portion of CD8+ T cells as well as NK cells.59 60 It is crucial to further examine the roles of aGM1+ cells on OAd35-mediated antitumor effects and to identify the aGM1+cells which play a key role in OAd35-mediated antitumor effects in future studies.

Antitumor therapeutic genes are often incorporated into the OV genome (so-called “arming”) to enhance the antitumor effects of OVs. Incorporation of immunostimulatory genes, such as IL-2,61 IL-12,62 IL-15,63 CD40L, OX40L,64 tumor antigens65 and full-length antibody,66 into OV genomes has been shown to significantly enhance the tumor infiltration of NK cells and/or CD8+ T cells, leading to efficient tumor growth suppression. These genetic modifications of the OAd35 genome would enhance the antitumor effects of OAd35 by inducing further activation and tumor infiltration of NK cells and CD8+ T cells.

Since human Ads cannot replicate in rodent cells, the antitumor effects of OAds are commonly assessed in human tumor-bearing immune-deficient mice, such as nude mice, severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) mice, or non-obese diabetic-SCID mice. Although innate immunity works in these immune-deficient mice, it is often overlooked.30 67 Our findings indicated that NK cells in BALB/c nude mice were significantly activated via OAd35-induced innate immunity and this probably contributed to the tumor growth inhibition of OAd35 (figure 1C,D). Nude mice possess various types of immune cells other than T cells. When the antitumor effects of OVs are assessed in nude mice, we should pay attention to the involvement of NK cells and other innate immune cells in the antitumor effects.

In conclusion, we revealed that OAd35 efficiently suppressed subcutaneous tumor growth in a virus infection-independent and aGM1+ cell-dependent manner following intratumoral administration. Type-I IFN signaling was involved in OAd35-mediated tumor infiltration and activation. These findings are essential for the clinical investigation of OAd35, and OAd35 is expected to become a promising cancer immunotherapy agent that enhances the antitumor activities of immune cells.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Kosuke Takayama, Tomohito Tsukamoto, Haruna Mizuta, Chiharu Arai, Yukiko Ueyama-Toba, Eiko Sakai (Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, The University of Osaka, Osaka, Japan), Kazunori Aoki (National Cancer Center Research Institute, Tokyo, Japan), and Hisashi Arase (Laboratory of Immunochemistry, World Premier International Immunology Frontier Research Centre, The University of Osaka, Osaka, Japan) for their support.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by grants-in-aid for Scientific Research (A) (20H00664, 23H00552) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (grant number JP24ym0126809), the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)) from AMED (grant numbers under grant numbers JP24ama121052 and JP24ama121054), and a grant from Oncolys Biopharma, Inc. RO is a Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (22J13377).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: The Animal Experiment Committee of The University of Osaka approved the animal experiments (approval no. DOYAKU R03-1-1).

Data availability free text: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and supplemental information.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Raja J, Ludwig JM, Gettinger SN, et al. Oncolytic virus immunotherapy: future prospects for oncology. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:140. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0458-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemminki O, Dos Santos JM, Hemminki A. Oncolytic viruses for cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:84. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00922-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang B, Sikorski R, Kirn DH, et al. Synergistic anti-tumor effects between oncolytic vaccinia virus and paclitaxel are mediated by the IFN response and HMGB1. Gene Ther. 2011;18:164–72. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moehler M, Zeidler M, Schede J, et al. Oncolytic parvovirus H1 induces release of heat-shock protein HSP72 in susceptible human tumor cells but may not affect primary immune cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10:477–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman HL, Kohlhapp FJ, Zloza A. Oncolytic viruses: a new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:642–62. doi: 10.1038/nrd4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bommareddy PK, Shettigar M, Kaufman HL. Integrating oncolytic viruses in combination cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:498–513. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malvehy J, Samoylenko I, Schadendorf D, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec upregulates immune-cell populations in non-injected lesions: findings from a phase II, multicenter, open-label study in patients with stage IIIB-IVM1c melanoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9:e001621. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribas A, Dummer R, Puzanov I, et al. Oncolytic Virotherapy Promotes Intratumoral T Cell Infiltration and Improves Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;170:1109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuo S, Wei M, Xu T, et al. An engineered oncolytic vaccinia virus encoding a single-chain variable fragment against TIGIT induces effective antitumor immunity and synergizes with PD-1 or LAG-3 blockade. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9:e002843. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng M, Huang J, Tong A, et al. Oncolytic Viruses for Cancer Therapy: Barriers and Recent Advances. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2019;15:234–47. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macedo N, Miller DM, Haq R, et al. Clinical landscape of oncolytic virus research in 2020. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e001486. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawashima T, Kagawa S, Kobayashi N, et al. Telomerase-specific replication-selective virotherapy for human cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:285–92. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crenshaw BJ, Jones LB, Bell CR, et al. Perspective on Adenoviruses: Epidemiology, Pathogenicity, and Gene Therapy. Biomedicines. 2019;7:61. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines7030061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mast TC, Kierstead L, Gupta SB, et al. International epidemiology of human pre-existing adenovirus (Ad) type-5, type-6, type-26 and type-36 neutralizing antibodies: Correlates of high Ad5 titers and implications for potential HIV vaccine trials. Vaccine (Auckl) 2010;28:950–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barouch DH, Kik SV, Weverling GJ, et al. International seroepidemiology of adenovirus serotypes 5, 26, 35, and 48 in pediatric and adult populations. Vaccine (Auckl) 2011;29:5203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang K-C, Altinoz M, Wosik K, et al. Impact of the coxsackie and adenovirus receptor (CAR) on glioma cell growth and invasion: requirement for the C-terminal domain. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:738–45. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korn WM, Macal M, Christian C, et al. Expression of the coxsackievirus- and adenovirus receptor in gastrointestinal cancer correlates with tumor differentiation. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13:792–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ono R, Takayama K, Sakurai F, et al. Efficient antitumor effects of a novel oncolytic adenovirus fully composed of species B adenovirus serotype 35. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2021;20:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2021.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogels R, Zuijdgeest D, van Rijnsoever R, et al. Replication-deficient human adenovirus type 35 vectors for gene transfer and vaccination: efficient human cell infection and bypass of preexisting adenovirus immunity. J Virol. 2003;77:8263–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.15.8263-8271.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbink P, Lemckert AAC, Ewald BA, et al. Comparative seroprevalence and immunogenicity of six rare serotype recombinant adenovirus vaccine vectors from subgroups B and D. J Virol. 2007;81:4654–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02696-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su Y, Liu Y, Behrens CR, et al. Targeting CD46 for both adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine prostate cancer. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e121497. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elvington M, Liszewski MK, Atkinson JP. CD46 and Oncologic Interactions: Friendly Fire against Cancer. Antibodies (Basel) 2020;9:59. doi: 10.3390/antib9040059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakurai F, Nakashima K, Yamaguchi T, et al. Adenovirus serotype 35 vector-induced innate immune responses in dendritic cells derived from wild-type and human CD46-transgenic mice: Comparison with a fiber-substituted Ad vector containing fiber proteins of Ad serotype 35. J Control Release. 2010;148:212–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pahl JHW, Verhoeven DHJ, Kwappenberg KMC, et al. Adenovirus type 35, but not type 5, stimulates NK cell activation via plasmacytoid dendritic cells and TLR9 signaling. Mol Immunol. 2012;51:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.02.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson MJ, Petrovas C, Yamamoto T, et al. Type I IFN induced by adenovirus serotypes 28 and 35 has multiple effects on T cell immunogenicity. J Immunol. 2012;188:6109–18. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson MJ, Björkström NK, Petrovas C, et al. Type I interferon-dependent activation of NK cells by rAd28 or rAd35, but not rAd5, leads to loss of vector-insert expression. Vaccine (Auckl) 2014;32:717–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murakami S, Sakurai F, Kawabata K, et al. Interaction of penton base Arg-Gly-Asp motifs with integrins is crucial for adenovirus serotype 35 vector transduction in human hematopoietic cells. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1525–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishii KJ, Coban C, Kato H, et al. A Toll-like receptor-independent antiviral response induced by double-stranded B-form DNA. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:40–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura T, Sato T, Endo R, et al. STING agonist loaded lipid nanoparticles overcome anti-PD-1 resistance in melanoma lung metastasis via NK cell activation. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9:e002852. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carreno BM, Garbow JR, Kolar GR, et al. Immunodeficient Mouse Strains Display Marked Variability in Growth of Human Melanoma Lung Metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3277–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosaka A, Wakita D, Matsubara N, et al. AsialoGM1+CD8+ central memory-type T cells in unimmunized mice as novel immunomodulator of IFN-gamma-dependent type 1 immunity. Int Immunol. 2007;19:249–56. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He K, Kimura T, Takeda K, et al. Characterization of anti-asialo-GM1 monoclonal antibody. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2025;743:151197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.151197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi YH, Lim EJ, Kim SW, et al. IL-27 enhances IL-15/IL-18-mediated activation of human natural killer cells. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:168. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0652-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao Q, Wang S, Chen X, et al. Cancer-cell-secreted CXCL11 promoted CD8+ T cells infiltration through docetaxel-induced-release of HMGB1 in NSCLC. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:42. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0511-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sindaco P, Pandey H, Isabelle C, et al. The role of interleukin-15 in the development and treatment of hematological malignancies. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1141208. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1141208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klebanoff CA, Finkelstein SE, Surman DR, et al. IL-15 enhances the in vivo antitumor activity of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1969–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307298101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trambley J, Bingaman AW, Lin A, et al. Asialo GM1(+) CD8(+) T cells play a critical role in costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1715–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee U, Santa K, Habu S, et al. Murine asialo GM1+CD8+ T cells as novel interleukin-12-responsive killer T cell precursors. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1996;87:429–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1996.tb00241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Umeshappa CS, Zhu Y, Bhanumathy KK, et al. Innate and adoptive immune cells contribute to natural resistance to systemic metastasis of B16 melanoma. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2015;30:72–8. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2014.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen D, Huang L, Zhou H, et al. Combining IL-10 and Oncolytic Adenovirus Demonstrates Enhanced Antitumor Efficacy Through CD8+ T Cells. Front Immunol. 2021;12:615089. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.615089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X, Wang P, Li H, et al. The Efficacy of Oncolytic Adenovirus Is Mediated by T-cell Responses against Virus and Tumor in Syrian Hamster Model. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:239–49. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takeda K, Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ, et al. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in surveillance of tumor metastasis by liver natural killer cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:94–100. doi: 10.1038/83416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guerra N, Tan YX, Joncker NT, et al. NKG2D-deficient mice are defective in tumor surveillance in models of spontaneous malignancy. Immunity. 2008;28:571–80. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imai K, Matsuyama S, Miyake S, et al. Natural cytotoxic activity of peripheral-blood lymphocytes and cancer incidence: an 11-year follow-up study of a general population. Lancet. 2000;356:1795–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gineau L, Cognet C, Kara N, et al. Partial MCM4 deficiency in patients with growth retardation, adrenal insufficiency, and natural killer cell deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:821–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI61014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spinner MA, Sanchez LA, Hsu AP, et al. GATA2 deficiency: a protean disorder of hematopoiesis, lymphatics, and immunity. Blood. 2014;123:809–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-515528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mandal R, Şenbabaoğlu Y, Desrichard A, et al. The head and neck cancer immune landscape and its immunotherapeutic implications. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89829. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimasaki N, Jain A, Campana D. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:200–18. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myers JA, Miller JS. Exploring the NK cell platform for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:85–100. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0426-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marotel M, Hasim MS, Hagerman A, et al. The two-faces of NK cells in oncolytic virotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020;56:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El-Sherbiny YM, Holmes TD, Wetherill LF, et al. Controlled infection with a therapeutic virus defines the activation kinetics of human natural killer cells in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;180:98–107. doi: 10.1111/cei.12562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, Jin J, Li Y, et al. NK cell tumor therapy modulated by UV-inactivated oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 2 and checkpoint inhibitors. Transl Res. 2022;240:64–86. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2021.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fleischmann CM, Stanton GJ, Fleischmann WR., Jr Enhanced in vivo sensitivity to interferon with in vitro resistant B16 tumor cells in mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1994;39:148–54. doi: 10.1007/BF01533379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang X, Zhang X, Fu ML, et al. Targeting the tumor microenvironment with interferon-β bridges innate and adaptive immune responses. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Audsley KM, Wagner T, Ta C, et al. IFNβ Is a Potent Adjuvant for Cancer Vaccination Strategies. Front Immunol. 2021;12:735133. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.735133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martinez J, Huang X, Yang Y. Direct action of type I IFN on NK cells is required for their activation in response to vaccinia viral infection in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;180:1592–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swann JB, Hayakawa Y, Zerafa N, et al. Type I IFN contributes to NK cell homeostasis, activation, and antitumor function. J Immunol. 2007;178:7540–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teigler JE, Kagan JC, Barouch DH. Late endosomal trafficking of alternative serotype adenovirus vaccine vectors augments antiviral innate immunity. J Virol. 2014;88:10354–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00936-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishikado H, Mukai K, Kawano Y, et al. NK cell-depleting anti-asialo GM1 antibody exhibits a lethal off-target effect on basophils in vivo. J Immunol. 2011;186:5766–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Monnier J, Zabel BA. Anti-asialo GM1 NK cell depleting antibody does not alter the development of bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e99350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dempe S, Lavie M, Struyf S, et al. Antitumoral activity of parvovirus-mediated IL-2 and MCP-3/CCL7 delivery into human pancreatic cancer: implication of leucocyte recruitment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:2113–23. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1279-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alkayyal AA, Tai L-H, Kennedy MA, et al. NK-Cell Recruitment Is Necessary for Eradication of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis with an IL12-Expressing Maraba Virus Cellular Vaccine. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5:211–21. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hock K, Laengle J, Kuznetsova I, et al. Oncolytic influenza A virus expressing interleukin-15 decreases tumor growth in vivo. Surgery. 2017;161:735–46. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ylösmäki E, Ylösmäki L, Fusciello M, et al. Characterization of a novel OX40 ligand and CD40 ligand-expressing oncolytic adenovirus used in the PeptiCRAd cancer vaccine platform. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2021;20:459–69. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2021.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Webb MJ, Sangsuwannukul T, van Vloten J, et al. Expression of tumor antigens within an oncolytic virus enhances the anti-tumor T cell response. Nat Commun. 2024;15:5442. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49286-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu B, Tian L, Chen J, et al. An oncolytic virus expressing a full-length antibody enhances antitumor innate immune response to glioblastoma. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5908. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kariya R, Matsuda K, Gotoh K, et al. Establishment of nude mice with complete loss of lymphocytes and NK cells and application for in vivo bio-imaging. In Vivo. 2014;28:779–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.