Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is characterized by the loss or dysfunction pancreatic β-cells. Human amniotic epithelial cells (hAEC), which retain pluripotency markers and are readily obtainable from term placentas, represent a promising alternative source of stem cells. We investigated whether hAECs can be guided through pancreatic ontogeny to generate insulin-producing β-like cells. hAEC from uncomplicated term deliveries were expanded to passage 1 and exposed to a four-stage differentiation sequence that sequentially modulated Activin/WNT, KGF/TGF-β, retinoic-acid/hedgehog, and EGF/Noggin signaling. Stage progression was monitored by end-point RT-PCR and quantitative immunofluorescence for hallmark transcription factors. After definitive endoderm induction, 64% of cells were Brachyury positive and 71% were WNT3A positive; primitive-gut specification yielded 57% HNF1B+ cells. Posterior foregut commitment produced 75% PDX1+ and 60% Sox9+ nuclei and the final endocrine stage generated 74% NKX2.2+ cells, with 71% showing cytoplasmatic insulin and 51% C-peptide staining; insulin/C-peptide co-localization was confirmed by double labelling. Thus a chemically defined, four-step protocol can convert term-derived hAEC into insulin-producing β-like cells, supporting their use as an accessible platform for diabetes modelling and future cell-replacement therapies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00418-025-02400-6.

Keywords: Human amniotic epithelial cells, Pancreatic beta cells, Differentiation

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major global health challenge. The International Diabetes Federation projects that about 853 million adults aged 20–79 years will be living with diabetes by 2050. DM is a group of carbohydrate metabolism disorders in which glucose is both underutilized and overproduced as a result of inappropriate gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, resulting in hyperglycemia. Chronic hyperglycemia is associated with long-term damage, dysfunction, and failure of various organs, particularly the eyes, kidneys, nerves, heart, and blood vessels (American Diabetes Association Professional Practice 2024a). These complications can lead to blindness, nontraumatic limb amputation, renal failure, among others issues (Campbell 2009).

Diabetes can be classified into four main types: type 1 diabetes (caused by autoimmune β-cell destruction, usually leading to absolute insulin deficiency); type 2 diabetes (resulting from a non-autoimmune progressive loss of adequate β-cell insulin secretion, associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome); other specific types of diabetes (due to other causes such as monogenic diabetes syndromes, diseases of the exocrine pancreas or drug- or chemical-induced diabetes); and gestational diabetes mellitus (diabetes diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy that was not clearly overt diabetes prior to gestation) (ElSayed et al. 2023).

Conventional pharmacologic therapy for adults with type 1 diabetes typically involves subcutaneous insulin infusion or multiple daily doses of prandial (injected or inhaled) and basal insulin (American Diabetes Association Professional Practice 2024b). For type 2 diabetes, the preferred initial pharmacologic agents are oral hypoglycemics. However, if these agents are contraindicated, not tolerated, or if the patient presents with markedly symptomatic and/or elevated blood glucose or A1C levels, insulin therapy (with or without additional agents) is a therapeutic option. If non-insulin monotherapy at the maximum tolerated dose fails to achieve or maintain target A1C levels for 3 months, a second oral agent, a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, or basal insulin is added to the regimen. As a result of the progressive nature of type 2 diabetes, insulin therapy eventually becomes necessary for many patients (American Diabetes 2015).

Pancreas transplantation could be an ideal treatment for patients with diabetes, offering sustained glycemic control and preventing complications associated with the disease (Dholakia et al. 2016). The first successful pancreas transplant was performed in 1966 (Kelly et al. 1967) and this procedure is now associated with improved glucose control (Scalea et al. 2018). However, the number of cadaveric donations worldwide remains very low (Abouna 2008). Moreover, pancreas transplant recipients often require higher levels of immunosuppression, potentially due to the increased immunogenicity of the pancreas and/or autoimmune status of the recipient (Redfield et al. 2015).

To overcome these challenges, recent advancements in stem cell and reprogramming have introduced an alternative approach differentiating pancreatic β-cells from pluripotent stem cells, such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (Zhang et al. 2009) or embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (Kroon et al. 2008). This approach has garnered significant interest in the field of regenerative medicine. However, several critical issues must still be addressed, including immune rejection, safety concerns, tumorigenesis, and ethical and legal issues. Therefore, further research is needed to explore and validate novel sources of stem cells.

Human fetal membranes, which comprise the chorion and amnion, offer a promising alternative for stem cell research. Unlike the chorion, human amniotic epithelial cells (hAEC), which originate from epiblast, can maintain a population of undifferentiated cells. These cell express pluripotent markers such as OCT-4, SOX-2, and NANOG (Avila-Gonzalez et al. 2019; Garcia-Castro et al. 2015; Garcia-Lopez et al. 2019) and have the capacity to differentiate into all three germ layers—endoderm (e.g., liver, pancreas), mesoderm (e.g., cardiomiocytes), and ectoderm (e.g., neural cells)—in vitro (Ilancheran et al. 2007). Additionally, hAEC exhibit several beneficial characteristics, including immunosuppressive properties, antibacterial activity, anti-tumor effects, and the absence of ethical and legal concern. These attributes make them a highly promising candidate for stem cell research. Here, we describe the directed differentiation of hAEC into β-like cells.

Materials and methods

Samples

Fetal membranes were collected after elective cesarean deliveries (n = 5). Written patient consent and ethical approval were obtained before tissue collection, in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Perinatology, protocol 21081. Women with uncomplicated term pregnancies (37–40 weeks), who had not experience labor activation or premature rupture of membranes, were included in this study. No evidence of microbiological signs of chorioamnionitis or lower genital tract infection was found in the fetal membranes.

Mechanical isolation and sterile pre-processing of hAEC

The human amniotic membrane (amnion) was mechanically detached from the chorion and placed in a container with 0.9% saline. Under aseptic conditions, the tissue was rinsed several times with saline solution to remove blood and clots. The amnion was then spread on a plastic table using forceps and wiped with gauze pads soaked in saline to clear any remaining debris.

Culture of hAEC

Subsequently, the tissue was processed following previously described methods (Avila-Gonzalez et al. 2019; Garcia-Castro et al. 2015; Garcia-Lopez et al. 2019; Romero-Reyes et al. 2021). Briefly, the amnion was placed in 10 ml of 0.5 mM ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA; Sigma-Aldrich, Merck Group, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA; E3889) solution and shaken by inversion for 30 s, followed by incubation in 15 ml of 0.5 mM EGTA solution at 37 °C for 10 min (these two digestions were discarded).

The tissue was then incubated twice in 25 ml of the 0.05% trypsin–EDTA solution for 40 min at 37 °C. Trypsin activity from these two digestions was inactivated with two volumes of culture medium (DMEM medium (Gibco, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Grand Island, New York, USA; 12100046) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum Certified (FBS, Gibco 16000-044). Both digestions were centrifuged at 200 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. hAEC were cultivated at a density of 3 × 104 cells/cm2 in standard culture medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% non-essentials amino acid 100× (Gibco 11140-050), 1% sodium pyruvate 100 mM (Gibco 11360-070), 1% antibiotic–antimycotic 100× (Gibco 15240062), and 500 μl β-mercaptoethanol 55 mM (Gibco 21985-023)) with 10 ng/ml human recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF) and incubated at 37 °C in normoxic conditions (5% CO2, 95% air) in a humidified incubator. The medium was changed every three days and supplemented with 10 ng/ml EGF daily until 80% confluence was reached.

In vitro differentiation of hAEC to insulin-producing β-like cells

The differentiation of hAEC into insulin-producing β-like cells was performed using a four-stage protocol adapted from the literature (D’Amour et al. 2006; Schulz et al. 2012).

Stage 1: To induce definitive endoderm, hAECs were cultured at a density of 3 × 104 cells/cm2 in RPMI medium (Gibco 1640) supplemented with 0.2% FBS, ITS (1:1000; Gibco 41400-045), 100 ng/ml activin A (PeproTech, Thermo Fischer Scientific; 120-14E), and 3 μM CHIR99021 (R&D System; Minnesota, USA; 4423/50) for 1 day. The following day, the medium was replaced with fresh RPMI supplemented with 100 ng/ml activin A and 0.3 μM CHIR99021 for an additional day.

Stage 2: To induce primitive gut tube formation, the hAEC were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 25 ng/ml keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) (PeproTech 100-19) and 2.5 µM TGF-β RI kinase inhibitor IV (TBI). The medium was changed every 3 days, with fresh KGF and TBI added daily.

Stage 3: For posterior foregut induction, the cells were cultured in 1% B27 (Gibco 17504-044)/DMEM (Gibco 12100061) medium (1× GlutaMax 100× (Gibco 35050-061), 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco 15140-148)) supplemented with 3 nM TTNPB (TT; TOCRIS bioscience 07-611-0), 0.25 µM cyclopamine (CYC; Sigma C4116), and 50 ng/ml Noggin (NOG; PeproTech 120-10C). The medium was changed every 3 days with TT, CYC, and NOG added daily.

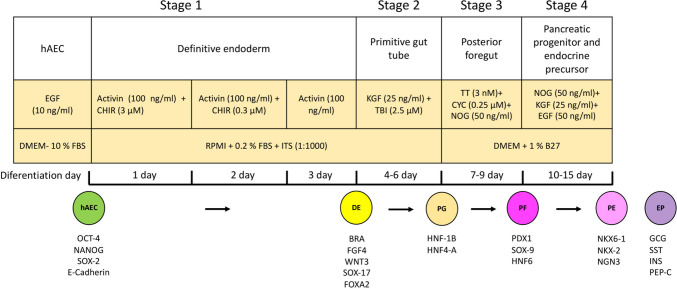

Stage 4: To induce pancreatic progenitor and endocrine precursor cells, hAEC were cultured in 1% B27/DMEM medium supplemented with 50 ng/ml NOG, 25 ng/ml KGF, and 50 ng/ml EGF. The medium was changed every 3 days, with the addition of NOG, KGF, and EGF daily for 6 days (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of four-stage differentiation protocol from human amniotic epithelial cells (hAEC) into definitive endoderm, primitive gut tube, posterior foregut, and mixed population comprising pancreatic endoderm and endocrine precursor cells

At the end of each stage, hAECs were processed according to their subsequent use.

RNA extraction

The phenol–chloroform method was used for RNA extraction. Trizol (100 μl; Thermo Fischer Scientific) was added to hAEC at the end of each stage and kept at room temperature for 5 min. Then, 16.65 μl of chloroform was added, vortexed for 15 s, and incubated for 3 min at room temperature. Samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The aqueous phase was extracted and transferred to a new tube. Isopropanol was added in a volume equal to that of the aqueous phase, mixed by inversion, incubated at − 20 °C for 5 min (to precipitate the RNA), and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was carefully removed and the pellet was dried for 10 min on sterile gauze. The pellet was resuspended in 40 μl of RNases-free water. RNA concentration and purity were measured by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop One; Thermo Fischer Scientific, 260 and 280 nm, path length 1 mm).

Purification of RNA with ethanol

For further RNA purification, 1 μl of sodium acetate (3 M, pH 5.2) was added to every 10 μl of RNA. Three volumes of chilled absolute ethanol were added, mixed by inversion 50 times, incubated at − 80 °C for 30 min, and centrifuged at 17,800 × g for 25 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed with 1 ml of 70% ethanol, centrifuged at 17,800 × g for 5 min at room temperature, and dried for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in 20 μl of RNases-free water. The RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry and stored at − 80 °C.

End-point RT-PCR

Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the reverse transcription system (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wisconsin, USA; A3500). A total of 800 ng of RNA was mixed with 5 mM MgCl2, 1× reverse transcription buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.0), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM dNTP, recombinant RNase inhibitor (1 u/μl), AMV reverse transcriptase (15 u/μg), oligo(dT) primer (0.5 μg). The reaction mixture was incubated at 42 °C for 60 min, then at 95 °C for 5 min, and finally at 4 °C for 5 min using a Mastercycler (Eppendorf Corporate, Hamburg, Germany).

Subsequent PCR was performed using the GoTaq system (Promega M8295) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. For this, 500 ng of cDNA was used in a reaction with a final volume of 50 μl (cDNA, 200 uM dNTPs, 2 mM MgCl2, 1× buffer, 50 pmol of specific forward and reverse primers, and 2.5 U of DNA polymerase). The sequences of the specific primer pairs for each gene are listed in Table 1. The amplification conditions were as follows: denaturalization 95 °C for 1 min, annealing at 55–61 °C (depending on gene) for 1 min, elongation at 72 °C for 1 min and final extension at 74 °C for 10 min, followed by cooling to 4 °C. For somatostatin, glucagon, and insulin, a pre-amplification of 15 cycles was performed. A total of 30–35 cycles were conducted and PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Products were stained with Gelred (Biotium, Fremont, California, USA; 41003) and size was determined by comparison with a molecular weight standard (100 bp DNA Ladder, Promega G210A). Negative controls without cDNA were included for PCR amplification.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and RT-PCR amplification conditions

Immunofluorescence

hAEC at each stage were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 20 min and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100/ PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, X100) for 45 min. Cells were then incubated with 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, A7906) to block non-specific epitopes for 45 min. Subsequently, hAEC were incubated with stage-specific primary antibodies.

Primary antibodies specific to BRACH, FGF4, WNT3, SOX-17, and FOXA2 were used to identify the formation of definitive endoderm in stage 1; HNF-1B and HNF-4A for primitive gut tube identification in stage 2; PDX-1 and SOX-9 for posterior foregut in stage 3; and NKX-6-1, NKX-2, glucagon (GCG), insulin (INS), and C-peptide (C-PEP) to identify pancreatic progenitor and endocrine precursor of stage 4 (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of antibodies

| Marker | Primary antibody | Dilution | Brand name | Antibody validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epithelial | Mouse anti-E-cadherin | 1:100 | BD Biosciences, 610181 | https://www.bdbiosciences.com/en-us/products/reagents/microscopy-imaging-reagents/immunofluorescence-reagents/purified-mouse-anti-e-cadherin.610181?tab=product_details |

| Pluripotency | Rabbit anti-OCT-4 | 1:100 | Abcam, Ab19857 | https://www.abcam.com/en-us/products/primary-antibodies/oct4-antibody-ab19857#overlay=images |

| Rabbit anti-SOX-2 | 1:200 | Merck Millipore, Ab5603 | https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/MX/es/product/mm/ab5603 | |

| Rabbit anti-NANOG | 1:200 | PeproTech, 500-P236 | https://www.thermofisher.com/antibody/product/Nanog-Antibody-Polyclonal/500-P236-1MG | |

|

Stage 1 Definitive endoderm |

Rabbit anti-BRA | 1:100 | Abcam, ab20680 | Anti-Brachyury / Bry antibody (ab20680) | Abcam |

| Goat anti-FGF4 | 1:100 | Santa Cruz, Sc-1361 | PMID: 12841847 | |

| Rabbit anti-WNT3 | 1:200 | Abcam, ab28472 | https://www.abcam.com/en-us/products/primary-antibodies/wnt3a-antibody-ab28472#overlay=images | |

| Mouse anti-SOX-17 | 1:100 | Abcam, ab84990 | PMID: 39493348 | |

| Rabbit anti-FOX-A2 | 1:200 | Abcam, ab40874 | PMID: 39251590 | |

|

Stage 2 Primitive gut tube |

Rabbit anti-HNF1B | 1:500 | Santa Cruz, Sc-22840 | PMID: 29158444 |

| Rabbit anti-HNF4A | 1:500 | Abcam, ab64911 | https://www.abcam.com/en-us/products/unavailable/hnf-4-alpha--hnf-4-gamma-antibody-ab64911 | |

|

Stage 3 Posterior foregut |

Rabbit anti-PDX1 | 1:200 | Abcam, ab47267 | PMID: 37662743 |

| Rabbit anti-SOX-9 | 1:50 | Abcam, ab118892 | https://www.abcam.com/en-us/products/unavailable/sox9-antibody-ab118892 | |

| Mouse anti-HNF6 | 1:50 | Abcam, ab87420 | https://www.abcam.com/en-us/products/unavailable/hnf6-antibody-4f12-ab87420 | |

|

Stage 4 Pancreatic progenitor and endocrine precursor |

Goat anti-NKX6-1 | 1:100 | Santa Cruz, Sc-15030 | PMID: 28423506 |

| Mouse anti-NGN3 | 1:200 | Abcam, ab87108 | https://www.abcam.com/en-us/products/unavailable/neurogenin3-antibody-oti3b5-ab87108 | |

| Rabbit anti-NKX2-2 | 1:100 | Santa Cruz, Sc-25404 | PMID: 36359244 | |

| Rabbit anti-GCG | 1:100 | Santa Cruz, Sc-13091 | PMID: 29321614 | |

| Mouse anti-SST | 1:100 | Santa Cruz, Sc-55565 | https://www.scbt.com/p/somatostatin-antibody-g-10 | |

| Rabbit anti-INS | 1:200 | Abcam, ab63820 | https://www.abcam.com/en-us/products/primary-antibodies/insulin-antibody-ab63820# | |

| Mouse anti-PEP C | 1:400 | Abcam, ab8297 | https://www.abcam.com/en-us/products/unavailable/c-peptide-antibody-1h8-ab8297 |

Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with appropriate fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies; Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (Invitrogen, Thermo Fischer Scientific; A11034) or Alexa Fluor® 568 goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (Invitrogen, Thermo Fischer Scientific; A11004) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, cell nuclei were counterstained with 0.2 µg/ml−1 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Invitrogen, Thermo Fischer Scientific; D1306). Secondary antibody background was assessed by primary antibody omission; no autofluorescence or non-specific signal was detected under the imaging conditions and as positive control for INS and C-PEP, human pancreas tissue was used (GeneTex, San Antonio, Texas, USA; GTX24611).

Microscopy and image acquisition

Images were collected on an epifluorescence microscope (Olympus IX-81, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a sCMOS camera (Hamamatsu, ORCA-Flash 2.8, Hamamatsu Photonics, Tokyo, Japan). Objective lens was LUCPlanFL 20X/0.45 NA Ph1 ∞/0–2/FN 22. Exposure time was 250 ms; camera gain was 1.2 e− ADU−1. All images were acquired at 1920 × 1440 pixels (0.18 μm pixel−1) and saved as 16-bit TIFF. Single band filter cubes were used: DAPI (exc 365 nm/10; em 445/50 nm), FITC/Alexa 488 (exc 470/40 nm; em 525/50 nm), and Cy3/Alexa 568 (exc 575/25 nm; em 610/60 nm). Multi-fluorescence images were acquired sequentially (channel-by-channel) with automatic filter-wheel switching to prevent spectral bleed-through. Lamp intensity was kept constant within each experiment.

Cell counting

At the end of each stage of the differentiation protocol, photomicrographs were captured and the number of cells positive for the stage-specific marker was assessed in nine randomly selected fields at ×200 magnification across five independent experiments. Merged images were generated using Adobe Photoshop 2024 software. The total cell count was determined by counting the DAPI-stained nuclei and the percentage of marker-positive cells was calculated using the following equation: % of positive cells = (number of single or double marker-positive cells × 100/(total number of DAPI-positive nuclei).

Results

hAEC at term express pluripotency markers

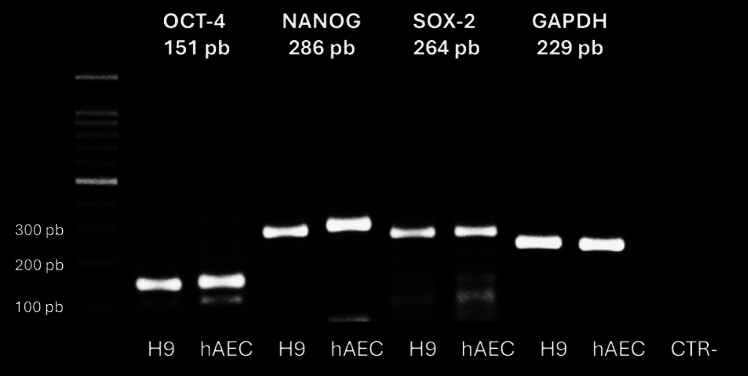

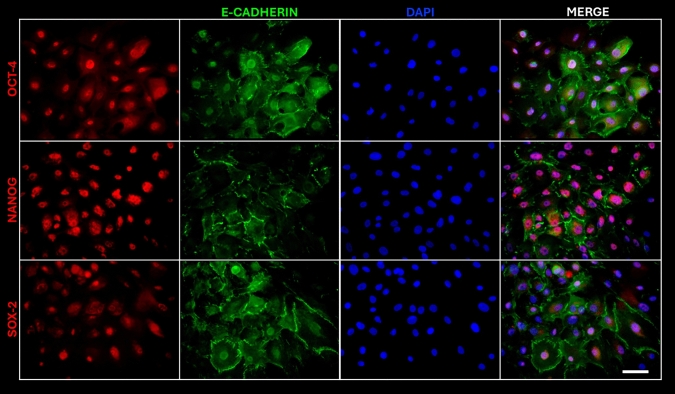

We isolated hAEC from term human membranes, which exhibited a cobblestone cytology and expressed pluripotency markers OCT-4, NANOG, and SOX-2 similar to human embryonic stem cell line H9 (Fig. 2). The presence of these transcription factors was confirmed by immunofluorescence. To eliminate the possibility of contamination by other cell types in our cultures, we also demonstrated the presence of E-cadherin, an epithelial marker (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of pluripotency marker gene expression in hAEC, including OCT-4, NANOG, and SOX-2. Positive control; human embryonic stem cell line H9 (CTR+). Negative control (CTR−): reactions without cDNA

Fig. 3.

Microphotographs of hAEC positive for pluripotency markers OCT-4, NANOG, and SOX-2 (red), E-cadherin (green) and DAPI (blue) staining the nuclei. Image taken at ×20. Scale bar = 100 μm

In vitro differentiation of hAEC to insulin-producing β-like cells

hAEC at passage 1 were differentiated into β-like cells using a four-stage protocol (Fig. 1). We assessed the expression of stage-specific markers in the resulting cells through RT-PCR and immunofluorescence. At the conclusion of stage 1, we analyzed the expression of definitive endoderm genes, such as BRACHYURY and SOX17 in hAEC (Figs. 4). While these markers were also found expressed in undifferentiated hAEC, RNA expression levels were higher in cells undergoing differentiation (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

RT-PCR analysis of gene expression in hAEC at the end of stage 1 of differentiation. Expression of constitutive gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in undifferentiated hAEC and hAEC at the end of the protocol (differ). The gels show the RT-PCR products for BRACHYURY (122 bp), SOX17 (151 bp), and GADPH (229 bp). Negative control (CTR): reactions without cDNA

Fig. 5.

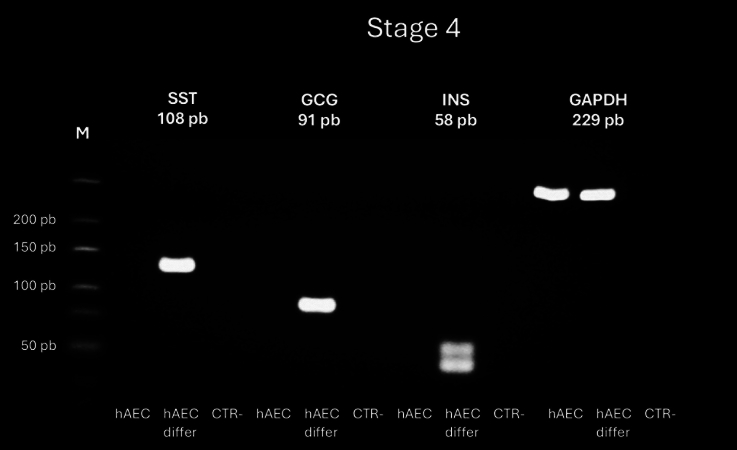

RT-PCR analysis of gene expression in hAEC at the end of stage 4 of differentiation protocol into insulin-positive cells. Expression of somatostatin (SST), glucagon (GCG), insulin (INS) and the constitutive gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in undifferentiated and differentiated (differ) hAEC. The gels shown RT-PCR products for SST (108 bp), CGC (91 bp), INS (58 bp), and GAPDH (229 bp). Negative control (CTR): reactions without cDNA

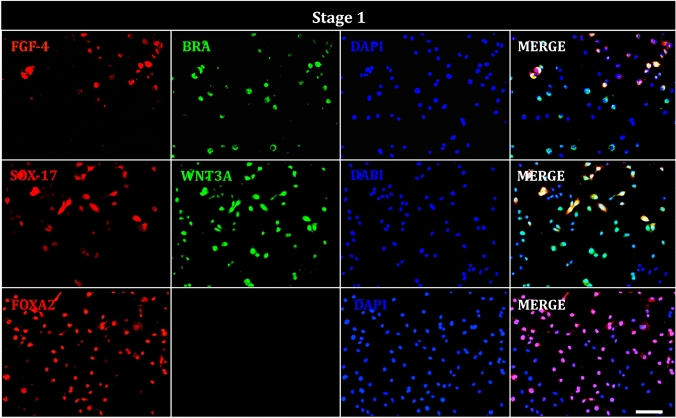

Next, we determined the presence of FGF-5, BRACHYURY, SOX-17, WNT3A, and FOXA2 in hAEC at the end of stage 1. Immunocytochemistry detected signals for each of these (Fig. 6). Notably, some cells exhibited co-localization of FGF-4 with BRACHURY and SOX-17 with WNT3A in our cultures.

Fig. 6.

Immunofluorescence of hAEC at stage 1 of differentiation. Representative images show cells positive for definitive endoderm markers; FGF-4 (red), BRACHYURY (BRA, green), SOX-17 (red), WNT3A (green), FOXA2 (red), and DAPI (blue) staining the nuclei. Image taken at ×20. Scale bar = 100 μm

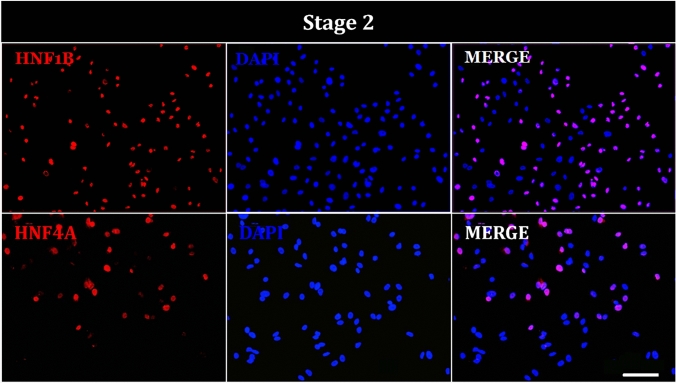

By the end of stage 2, cells displayed nuclear positivity for HNF-1B and HNF-4A, suggesting their involvement as transcription factors in primitive gut development (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Immunofluorescence of hAEC at stage 2 of differentiation. Representative images show cells positive for primitive gut tube markers; HNF1B (red), HNF4A (red), and DAPI (blue) staining the nuclei. Image taken at ×20. Scale bar = 100 μm

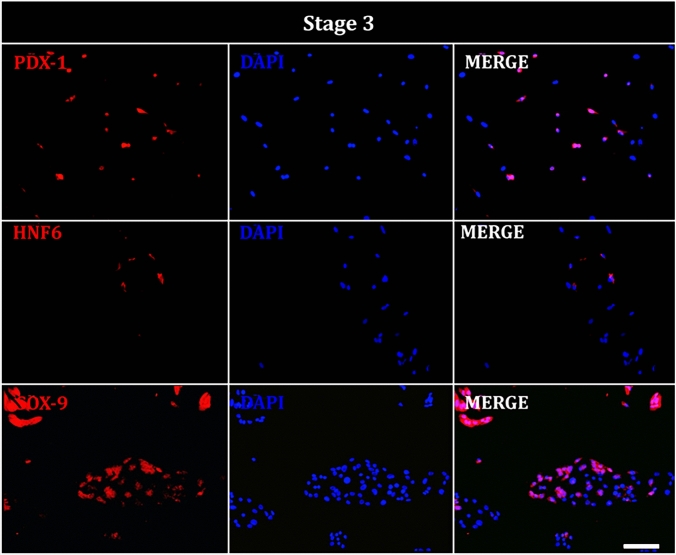

During stage 3, cells showed nuclear expression of PDX-1, HNF6, and SOX-9, indicating differentiation toward the foregut (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Immunofluorescence of hAEC at stage 3 of differentiation. Representative images show cells positive for posterior foregut markers; PDX-1 (red), HNF-6 (red), SOX-9 (red), and DAPI (blue) staining the nuclei. Image taken at ×20. Scale bar = 100 μm

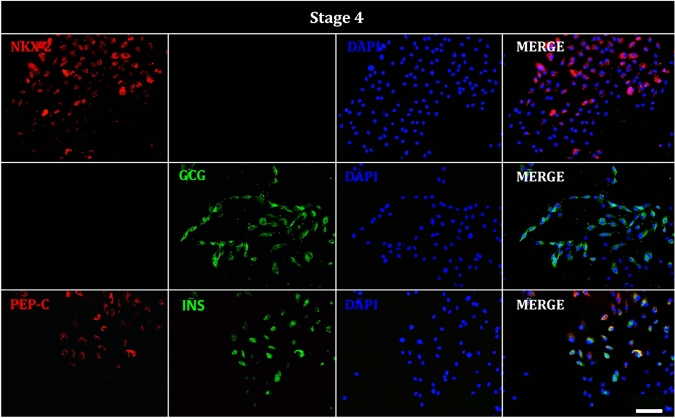

Finally, at the conclusion of the differentiation protocol, we detected RNA expression of somatostatin and insulin exclusively in cells subjected to the differentiation process (Fig. 5). Additionally, NKX2 was observed in the nuclei and glucagon was present in the cytoplasm. Some cells also exhibited co-localization of C-PEP and insulin markers in the cytoplasm, suggesting the successful differentiation of hAEC into β-like cells (Fig. 9). Antibody specificity for C-PEP and insulin was confirmed using human pancreatic tissue as a positive control (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 9.

Immunofluorescence of hAEC at stage 4 of differentiation. Representative images show cells positive for pancreatic progenitor and endocrine precursor markers; NKX2 (red), glucagon, (GCG, green), C-peptide (C-PEP, red), insulin (INS, green), and DAPI (blue) staining the nuclei. Image taken at ×20. Scale bar = 100 μm

At the end of each stage of the differentiation protocol, we quantified the percentage of hAECs positive for key stage-specific markers. In the definitive endoderm stage, 63.6% of cells were positive for BRACHYURY, 42.8% for FGF4, 71.2% for WNT3A, 34.1% for SOX17, and 56.6% for FOXA2. During the primitive gut tube formation stage, 56.6% of cells were positive for HNF1B and 34.6% for HNF4A. In the foregut stage, 74.9% of the cells showed positivity for PDX1, 6.2% for HNF6, and 60% for SOX-9. Finally, in the endocrine precursor stage, we observed 74.3% of cells positive to NKX-2, 76.5% positives for GCG, 71.1% positives for insulin, and 51.4% positive for C-PEP (Fig. 10)

Fig. 10.

Quantification of marker-positive cells at each stage of the differentiation protocol from human amniotic epithelial cells (hAEC)

Discussion

We demonstrated that a fully defined, four-stage differentiation sequence differentiates term hAEC into insulin-producing β-like cells.

The development of an effective therapy for diabetes remains a major challenge. Despite advancements in hypoglycemic treatments and drugs designed to regulate insulin release, these interventions often fail to provide consistent control over acute complications or avoided unwanted side effects. Furthermore, the bioavailability of the biologicals source often limits therapeutic efficiency. Thus, pancreatic transplantation has emerged as a potentially superior treatment option for patients and possibly a definitive solution.

Regenerative therapy using stem cells has shown promise, particularly with the successful generation of insulin-producing cells from human embryonic stem cells (D’Amour et al. 2006; Shim et al. 2007; Jiang et al. 2007; Kroon et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2009; Rezania et al. 2014; Pagliuca et al. 2014; Agulnick et al. 2015; Hogrebe et al. 2021) or hIPSC (Zhao et al. 2023; Silva et al. 2022) through various protocols. However, several challenges remain before these therapies can be fully adopted in regenerative medicine. These include ethical and legal issues, the potential for teratoma formation, and the limited availability of stem cell sources beyond Anglo-Saxon or Asian populations (Kuroda et al. 2013; Volarevic et al. 2018; Charitos et al. 2021). Given these limitations hAEC could represent an alternative source of stem cells owing to their pluripotent characteristics, lack of ethical concerns, among others (Garcia-Lopez et al. 2015).

In our study, we initiated the differentiation protocol with a population of hAEC expressing undifferentiated markers such as OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2, demonstrated at both mRNA and protein level (Fig. 2 and 3). Our population was also positive for E-cadherin, ruling out the possibility of contamination by other layers of the fetal membranes. While other studies have reported hAEC differentiation, they have often failed to demonstrate pluripotency markers (Luo et al. 2019; Szukiewicz et al. 2010; Tamagawa et al. 2009) or they reported only one or two pluripotency factors at either the mRNA or protein level (Luo et al. 2019; Wei et al. 2003). As hAEC are known to be heterogeneous, establishing their pluripotency is critical for any differentiation protocol.

The differentiation potential of hAEC has been extensively explored, with evidence supporting their ability to differentiate into various functional cell types from the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm (Michalik et al. 2022; Niknejad et al. 2010; Luo et al. 2011). In the context of differentiation into insulin-producing β-like cells, several studies have employed nicotinamide over 2–3 weeks. Wei et al. (2003) were among the first to demonstrate the differentiation of hAEC into insulin-secreting cells. They showed that hAEC express mRNA for insulin and glucose transporter 2 and markers such as Nestin, GATA-4, and HNF-3β after treatment. Their functional efficacy was validated in a hyperglycemic mouse model, where grafted hAEC lower blood glucose levels compared to the sham group (Wei et al. 2003).

Szukiewicz et al. (2010) demonstrate hAEC differentiation into pancreatic beta-like cells, although they only reported C-PEP levels in the culture medium using immunoenzymatic techniques. Zou et al. (2016) induced differentiation into islet-like cells, reporting insulin and glucose transporter 2 expression and presence via RT-PCR and western blot, respectively. After treatment with nicotinamide, they found that hAECs were immunoreactive to insulin and secreted C-PEP upon KCl stimulation. Their in vivo experiments demonstrated that hAEC grafts reduced blood glucose levels in hyperglycemic rats within 5 weeks post grafting. All these results were obtained in a siRNA-Mock model (Zou et al. 2016).

Tamagawa et al. (2009) developed a three-step differentiation protocol designed to mimic pancreatic development, although they used fibroblasts from the amniotic membrane and nicotinamide in the final stage. Their results indicated mRNA expression for insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin as well as protein presence, after 18 days of differentiation. Luo et al. (2019) later refined these methods, employing a three-step protocol (definitive endoderm, pancreatic progenitor cells, and insulin-producing cells) with the addition of hyaluronic acid and nicotinamide to enhance differentiation efficiency. They found that hyaluronic acid upregulated key regulators like Pdx1, Nkx6.1, and Pax4, but had no effect on Ngn3 and Pax6 expression. Similar to previous reports, these cells reduced glucose level when transplanted into hyperglycemic mice (Luo et al. 2019).

However, despite the generation of insulin-positive cells and evidence of glucose-lowering effects, none of these studies investigated the underlying mechanism of hAEC differentiation or transdifferentiation. Furthermore, they did not quantify the percentage of insulin or C-PEP-positive cells generated. The use of nicotinamide in these protocols, while effective, highlights its role as a poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase inhibitor, know to increase β-cell mass in cultured human fetal pancreatic cells (Otonkoski et al. 1993) and transdifferentiate hepatic oval cells to synthesize insulin. While its precise mechanism in hAEC differentiation remains unclear, it is possible that it involves chromatin modification that facilitate gene transcription, potentially activating non-target genes.

Our study aimed to address these gaps by applying a sequential differentiation protocol designed to mimic in vivo pancreatic development (D’Amour et al. 2006). Through stepwise inactivating or activating key signaling pathways, we guided hAEC towards endocrine precursors and ultimately insulin-producing β-like cells. Thus, we characterize various cell populations during critical stages of pancreatic development at both mRNA and protein levels.

At the mRNA level, we note a qualitative increase in the expression of BRACH and SOX-17 during the first stage of differentiation, compared to undifferentiated hAEC (Fig. 4). The mesoderm-specific gene BRACH is regulated by the Wnt signaling pathway in ES cells (Arnold et al. 2000). Notably, we detected pancreatic hormone mRNA exclusively in the hAEC following differentiation, suggesting their responsiveness to mesodermal development signals similar to pluripotent stem cell lines.

At the protein level, cells positive for BRACH, FGF4, WNT, SOX17, and FOXA2 were observed followed by those positive for HNF1B and HNF4A at the end of the primitive gut tube stage. In the third stage, we identified PDX-1, HNF6, and SOX-9-positive cells. Notably, PDX-1 is essential for the maturation of endocrine cells, further supporting the idea that our protocol recapitulates key aspects of pancreatic development.

After completing the differentiation protocol, a significant population of cells was positive for insulin and C-PEP (64.1% and 35%, respectively), with co-localization of these markers observed in our cultures. These findings suggest that the differentiated cells possess the machinery necessary for insulin synthesis.

These percentages are comparable with previous reports obtained from multiple hESC lines which reported 20–60% of β-cells (D’Amour et al. 2006; Hogrebe et al. 2021), or from iPSC (Fantuzzi et al. 2022). However, unlike iPSC, which retain epigenetic memory that complicates their use in clinical settings, hAEC lack such as limitations, making them an attractive candidate for regenerative therapies. While our study demonstrated the successful differentiation of hAEC into insulin-producing β-like cells, several challenges remain. The functional maturity of these cells, particularly their ability to respond to glucose stimuli, must be thoroughly evaluated in future studies. Additionally, long-term transplantation experiments in animal models are necessary to assess the stability and functionally of these cells in vivo.

Conclusions

We present a protocol for differentiating hAEC into pancreatic beta-like cells opening new possibilities for using hAEC as stem cell source in diabetes research. The results of this study provide a valuable model not only for generating insulin-producing β-like cells but also for testing hypoglycemic drugs, studying developmental processes, and exploring pancreatic disease mechanisms. This represents a significant advance in the potential application of hAEC in regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

MRD, conception of the work; acquisition and analysis of data; SAJ, CAA, AGD, MAO, MHA, acquisition, interpretation and analysis of data; MJA, GMH, LBDE, acquisition and analysis of data, PMW, DMNE cquisition, interpretation and analysis of data; GLG and NFD conception of the work; analysis and interpretation of data; drafted the work. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Instituto Nacional de Perinatología (21081, 2018-1-150 and 2019-1-40) and CONACYT (140917 and A1-S-8450).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guadalupe García-López, Email: guadalupegl2000@yahoo.com.mx.

Nestor Fabián Díaz, Email: nfdiaz00@yahoo.com.mx.

References

- Abouna GM (2008) Organ shortage crisis: problems and possible solutions. Transplant Proc 40(1):34–38. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.11.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agulnick AD, Ambruzs DM, Moorman MA, Bhoumik A, Cesario RM, Payne JK, Kelly JR, Haakmeester C, Srijemac R, Wilson AZ, Kerr J, Frazier MA, Kroon EJ, D’Amour KA (2015) Insulin-producing endocrine cells differentiated in vitro from human embryonic stem cells function in macroencapsulation devices in vivo. Stem Cells Transl Med 4(10):1214–1222. 10.5966/sctm.2015-0079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association (2015) (7) Approaches to glycemic treatment. Diabetes Care 38(Suppl):S41-48. http://doi.org/10.2337/dc15-S010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee (2024a) 2 Diagnosis and classification of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 47(Supp1):S20–S42. 10.2337/dc24-S002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee (2024b) 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of care in diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 47(1):S158–S178. 10.2337/dc24-S009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SJ, Stappert J, Bauer A, Kispert A, Herrmann BG, Kemler R (2000) Brachyury is a target gene of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Mech Dev 91(1–2):249–258. 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00309-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Gonzalez D, Garcia-Lopez G, Diaz-Martinez NE, Flores-Herrera H, Molina-Hernandez A, Portillo W, Diaz NF (2019) In vitro culture of epithelial cells from different anatomical regions of the human amniotic membrane. J vis Exp. 10.3791/60551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RK (2009) Type 2 diabetes: where we are today: an overview of disease burden, current treatments, and treatment strategies (2003). J Am Pharm Assoc 49(Suppl 1):S3-9. 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.09077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charitos IA, Ballini A, Cantore S, Boccellino M, Di Domenico M, Borsani E, Nocini R, Di Cosola M, Santacroce L, Bottalico L (2021) Stem cells: a historical review about biological, religious, and ethical issues. Stem Cells Int 2021:9978837. 10.1155/2021/9978837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amour KA, Bang AG, Eliazer S, Kelly OG, Agulnick AD, Smart NG, Moorman MA, Kroon E, Carpenter MK, Baetge EE (2006) Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 24(11):1392–1401. 10.1038/nbt1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dholakia S, Mittal S, Quiroga I, Gilbert J, Sharples EJ, Ploeg RJ, Friend PJ (2016) Pancreas transplantation: past, present. Future Am J Med 129(7):667–673. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, Collins BS, Hilliard ME, Isaacs D, Johnson EL, Kahan S, Khunti K, Leon J, Lyons SK, Perry ML, Prahalad P, Pratley RE, Seley JJ, Stanton RC, Gabbay RA, American Diabetes Association (2023) 2 classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 46(Suppl 1):S19–S40. 10.2337/dc23-S002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzi F, Toivonen S, Schiavo AA, Chae H, Tariq M, Sawatani T, Pachera N, Cai Y, Vinci C, Virgilio E, Ladriere L, Suleiman M, Marchetti P, Jonas JC, Gilon P, Eizirik DL, Igoillo-Esteve M, Cnop M (2022) In depth functional characterization of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived beta cells in vitro and in vivo. Front Cell Dev Biol 10:967765. 10.3389/fcell.2022.967765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Castro IL, Garcia-Lopez G, Avila-Gonzalez D, Flores-Herrera H, Molina-Hernandez A, Portillo W, Ramon-Gallegos E, Diaz NF (2015) Markers of pluripotency in human amniotic epithelial cells and their differentiation to progenitor of cortical neurons. PLoS ONE 10(12):e0146082. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lopez G, Garcia-Castro IL, Avila-Gonzalez D, Molina-Hernandez A, Flores-Herrera H, Merchant-Larios H, Diaz-Martinez F (2015) Human amniotic epithelium (HAE) as a possible source of stem cells (SC). Gac Med Mex 151(1):66–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lopez G, Avila-Gonzalez D, Garcia-Castro IL, Flores-Herrera H, Molina-Hernandez A, Portillo W, Diaz-Martinez NE, Sanchez-Flores A, Verleyen J, Merchant-Larios H, Diaz NF (2019) Pluripotency markers in tissue and cultivated cells in vitro of different regions of human amniotic epithelium. Exp Cell Res 375(1):31–41. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogrebe NJ, Maxwell KG, Augsornworawat P, Millman JR (2021) Generation of insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells from multiple human stem cell lines. Nat Protoc 16(9):4109–4143. 10.1038/s41596-021-00560-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilancheran S, Michalska A, Peh G, Wallace EM, Pera M, Manuelpillai U (2007) Stem cells derived from human fetal membranes display multilineage differentiation potential. Biol Reprod 77(3):577–588. 10.1095/biolreprod.106.055244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Au M, Lu K, Eshpeter A, Korbutt G, Fisk G, Majumdar AS (2007) Generation of insulin-producing islet-like clusters from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 25(8):1940–1953. 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WD, Lillehei RC, Merkel FK, Idezuki Y, Goetz FC (1967) Allotransplantation of the pancreas and duodenum along with the kidney in diabetic nephropathy. Surgery 61(6):827–837 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon E, Martinson LA, Kadoya K, Bang AG, Kelly OG, Eliazer S, Young H, Richardson M, Smart NG, Cunningham J, Agulnick AD, D’Amour KA, Carpenter MK, Baetge EE (2008) Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 26(4):443–452. 10.1038/nbt1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda T, Yasuda S, Sato Y (2013) Tumorigenicity studies for human pluripotent stem cell-derived products. Biol Pharm Bull 36(2):189–192. 10.1248/bpb.b12-00970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Huang X, Huang F, Liu X (2011) Transversal inducing differentiation of human amniotic epithelial cells into hepatocyte-like cells. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 36(6):525–531. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2011.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Cheng YW, Yu CY, Liu RM, Zhao YJ, Chen DX, Zhong JJ, Xiao JH (2019) Effects of hyaluronic acid on differentiation of human amniotic epithelial cells and cell-replacement therapy in type 1 diabetic mice. Exp Cell Res 384(2):111642. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.111642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalik M, Wieczorek P, Czekaj P (2022) In vitro differentiation of human amniotic epithelial cells into hepatocyte-like cells. Cells. 10.3390/cells11142138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niknejad H, Peirovi H, Ahmadiani A, Ghanavi J, Jorjani M (2010) Differentiation factors that influence neuronal markers expression in vitro from human amniotic epithelial cells. Eur Cell Mater 19:22–29. 10.22203/ecm.v019a03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otonkoski T, Beattie GM, Mally MI, Ricordi C, Hayek A (1993) Nicotinamide is a potent inducer of endocrine differentiation in cultured human fetal pancreatic cells. J Clin Invest 92(3):1459–1466. 10.1172/JCI116723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliuca FW, Millman JR, Gurtler M, Segel M, Van Dervort A, Ryu JH, Peterson QP, Greiner D, Melton DA (2014) Generation of functional human pancreatic beta cells in vitro. Cell 159(2):428–439. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfield RR, Scalea JR, Odorico JS (2015) Simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation: current trends and future directions. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 20(1):94–102. 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezania A, Bruin JE, Arora P, Rubin A, Batushansky I, Asadi A, O’Dwyer S, Quiskamp N, Mojibian M, Albrecht T, Yang YH, Johnson JD, Kieffer TJ (2014) Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 32(11):1121–1133. 10.1038/nbt.3033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Reyes J, Vazquez-Martinez ER, Bahena-Alvarez D, Lopez-Jimenez J, Molina-Hernandez A, Camacho-Arroyo I, Diaz NF (2021) Differential localization of serotoninergic system elements in human amniotic epithelial cellsdagger. Biol Reprod 105(2):439–448. 10.1093/biolre/ioab106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalea JR, Pettinato L, Fiscella B, Bartosic A, Piedmonte A, Paran J, Todi N, Siskind EJ, Bartlett ST (2018) Successful pancreas transplantation alone is associated with excellent self-identified health score and glucose control: a retrospective study from a high-volume center in the United States. Clin Transplant. 10.1111/ctr.13177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz TC, Young HY, Agulnick AD, Babin MJ, Baetge EE, Bang AG, Bhoumik A, Cepa I, Cesario RM, Haakmeester C, Kadoya K, Kelly JR, Kerr J, Martinson LA, McLean AB, Moorman MA, Payne JK, Richardson M, Ross KG, Sherrer ES, Song X, Wilson AZ, Brandon EP, Green CE, Kroon EJ, Kelly OG, D’Amour KA, Robins AJ (2012) A scalable system for production of functional pancreatic progenitors from human embryonic stem cells. PLoS ONE 7(5):e37004. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JH, Kim SE, Woo DH, Kim SK, Oh CH, McKay R, Kim JH (2007) Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells towards a pancreatic cell fate. Diabetologia 50(6):1228–1238. 10.1007/s00125-007-0634-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva IBB, Kimura CH, Colantoni VP, Sogayar MC (2022) Stem cells differentiation into insulin-producing cells (IPCs): recent advances and current challenges. Stem Cell Res Ther 13(1):309. 10.1186/s13287-022-02977-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szukiewicz D, Pyzlak M, Stangret A, Rongies W, Maslinska D (2010) Decrease in expression of histamine H2 receptors by human amniotic epithelial cells during differentiation into pancreatic beta-like cells. Inflamm Res 59(Suppl 2):S205-207. 10.1007/s00011-009-0131-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamagawa T, Ishiwata I, Sato K, Nakamura Y (2009) Induced in vitro differentiation of pancreatic-like cells from human amnion-derived fibroblast-like cells. Hum Cell 22(3):55–63. 10.1111/j.1749-0774.2009.00069.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volarevic V, Markovic BS, Gazdic M, Volarevic A, Jovicic N, Arsenijevic N, Armstrong L, Djonov V, Lako M, Stojkovic M (2018) Ethical and safety issues of stem cell-based therapy. Int J Med Sci 15(1):36–45. 10.7150/ijms.21666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei JP, Zhang TS, Kawa S, Aizawa T, Ota M, Akaike T, Kato K, Konishi I, Nikaido T (2003) Human amnion-isolated cells normalize blood glucose in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Cell Transplant 12(5):545–552. 10.3727/000000003108747000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Jiang W, Liu M, Sui X, Yin X, Chen S, Shi Y, Deng H (2009) Highly efficient differentiation of human ES cells and iPS cells into mature pancreatic insulin-producing cells. Cell Res 19(4):429–438. 10.1038/cr.2009.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Liang S, Braam MJS, Baker RK, Iworima DG, Quiskamp N, Kieffer TJ (2023) Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into insulin-producing islet clusters. J vis Exp. 10.3791/64840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G, Liu T, Guo L, Huang Y, Feng Y, Huang Q, Duan T (2016) miR-145 modulates lncRNA-ROR and Sox2 expression to maintain human amniotic epithelial stem cell pluripotency and beta islet-like cell differentiation efficiency. Gene 591(1):48–57. 10.1016/j.gene.2016.06.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.