Abstract

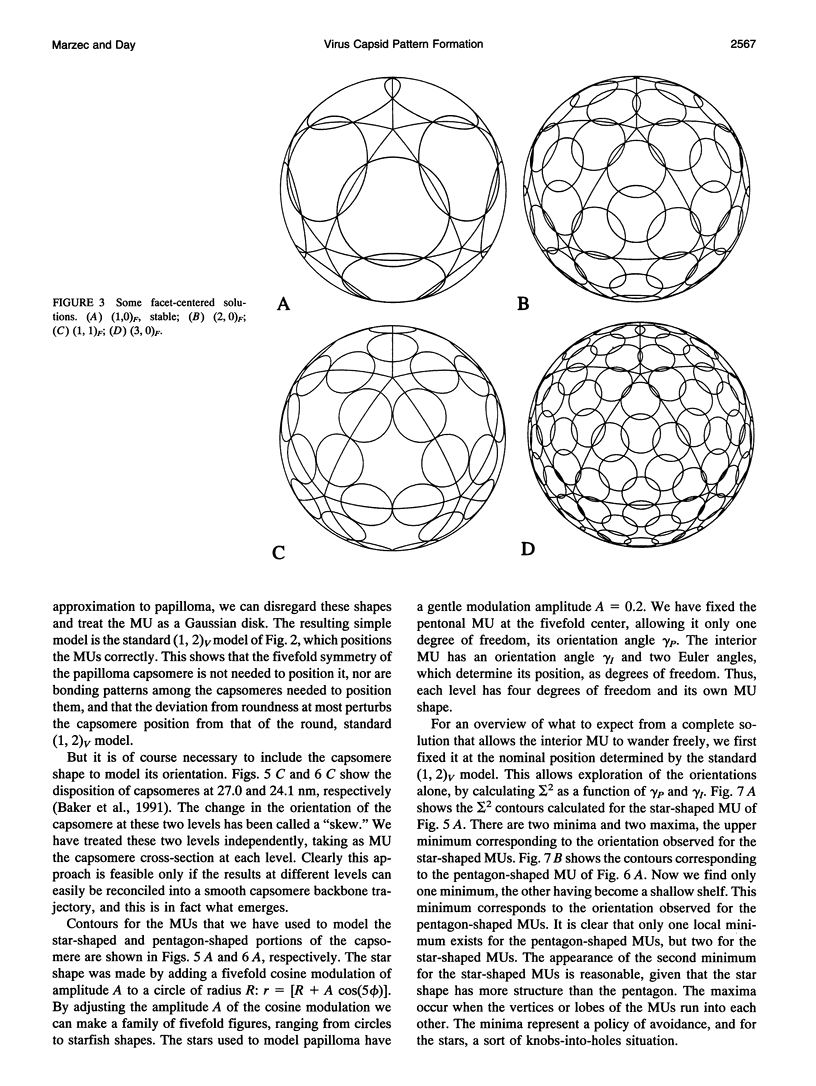

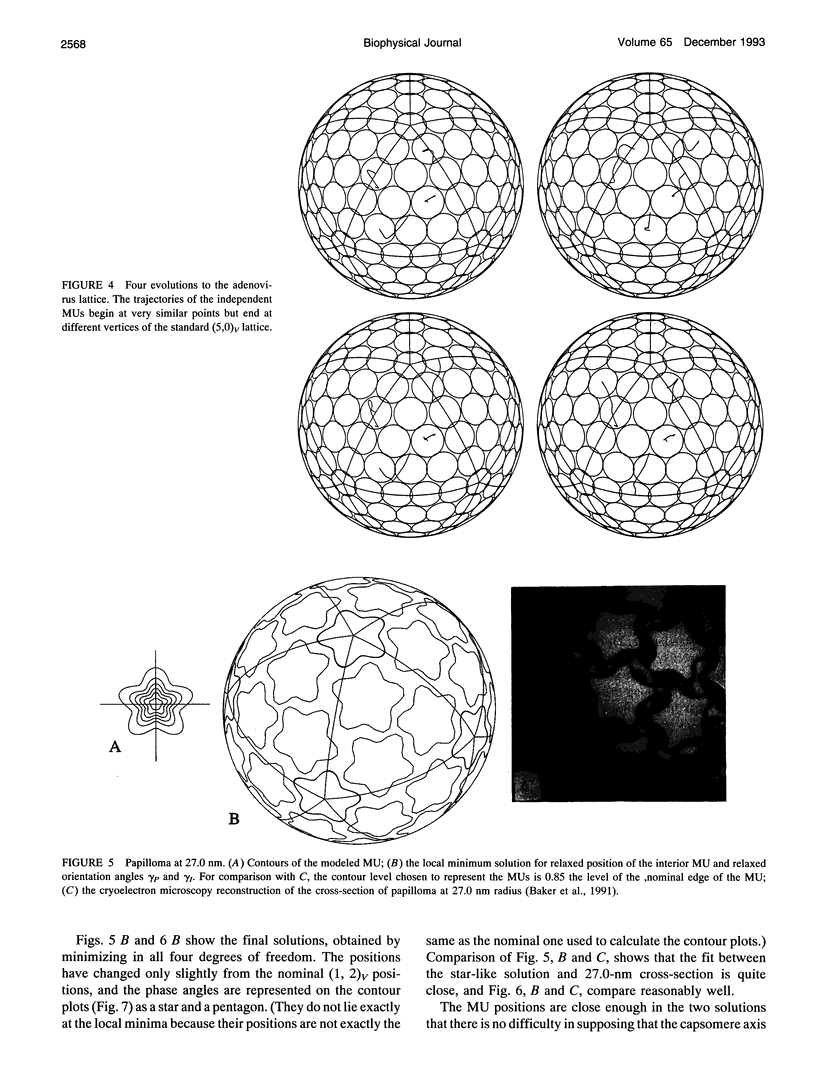

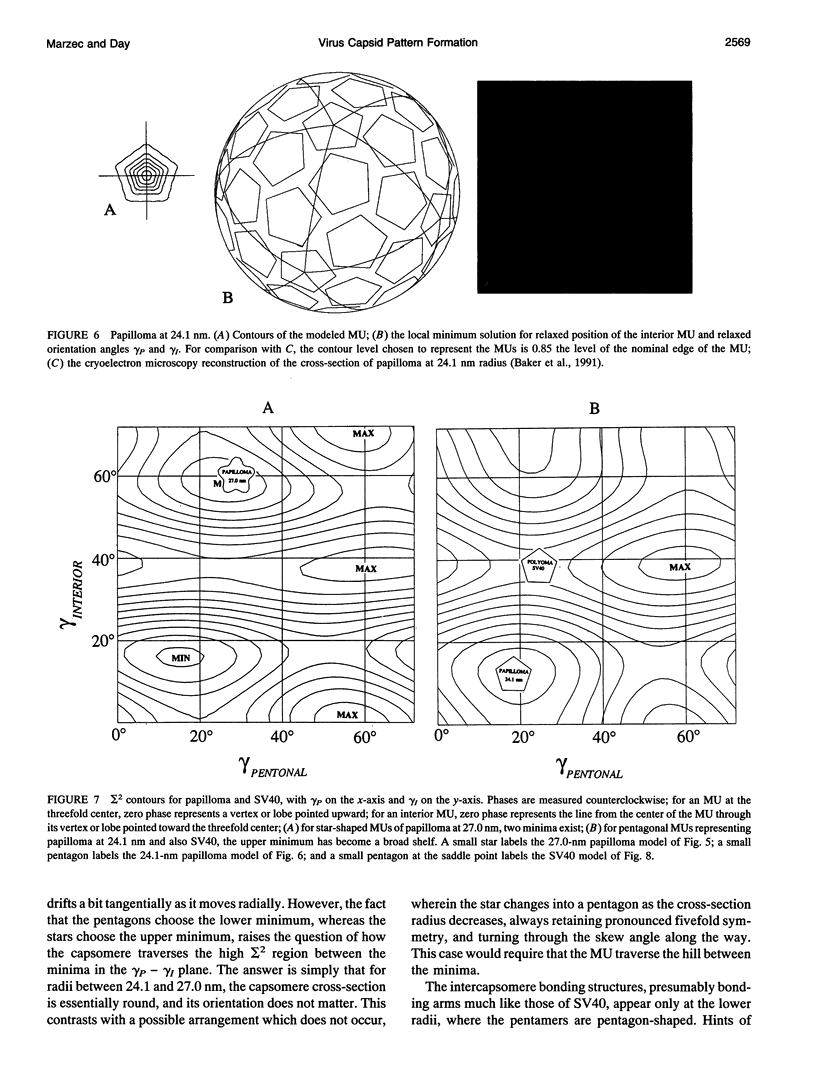

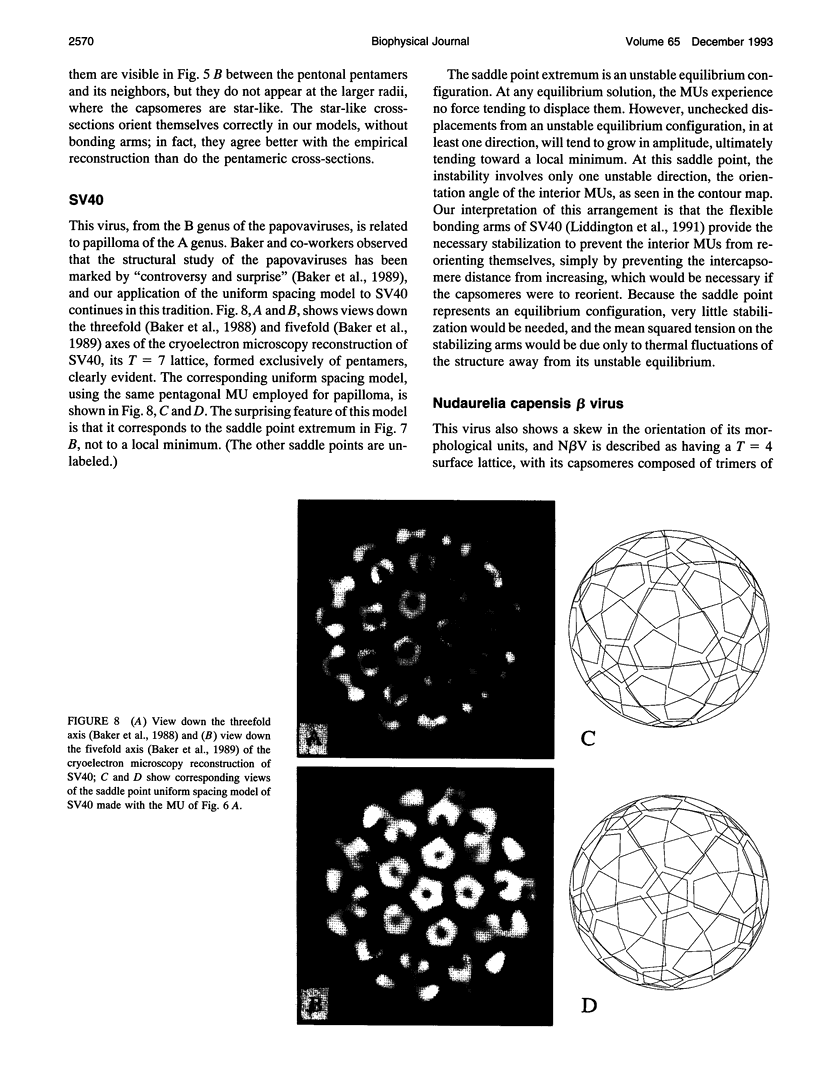

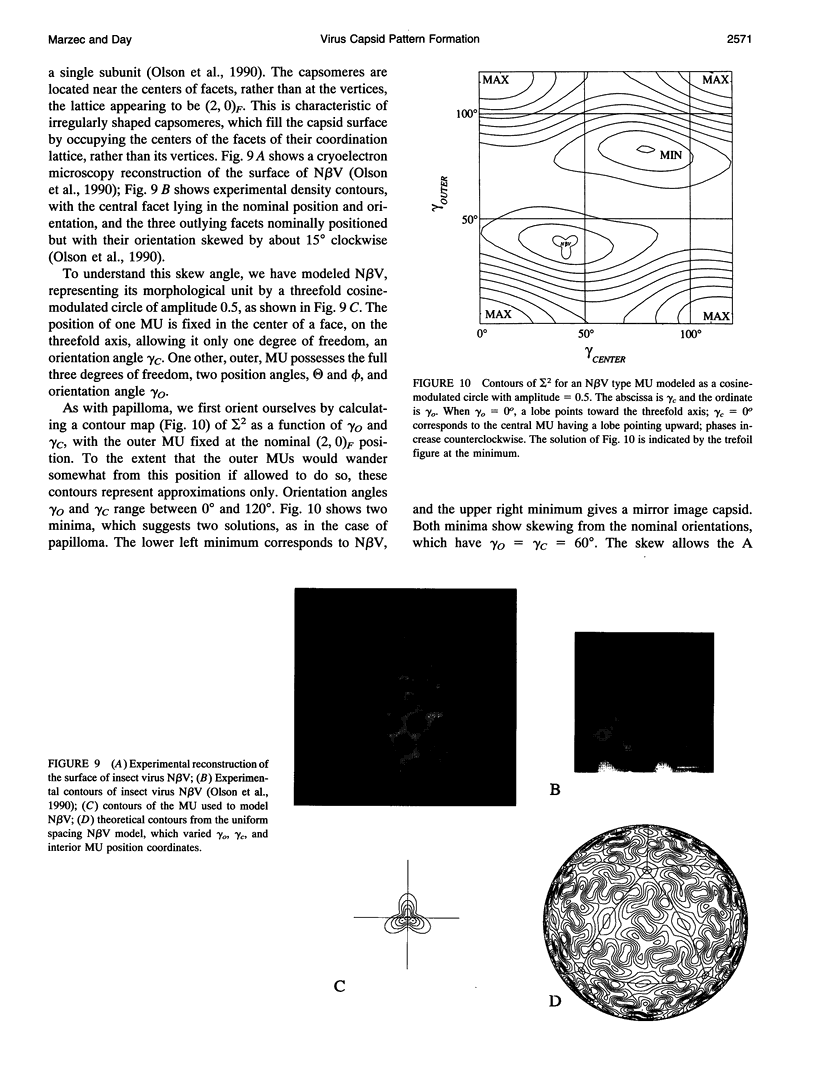

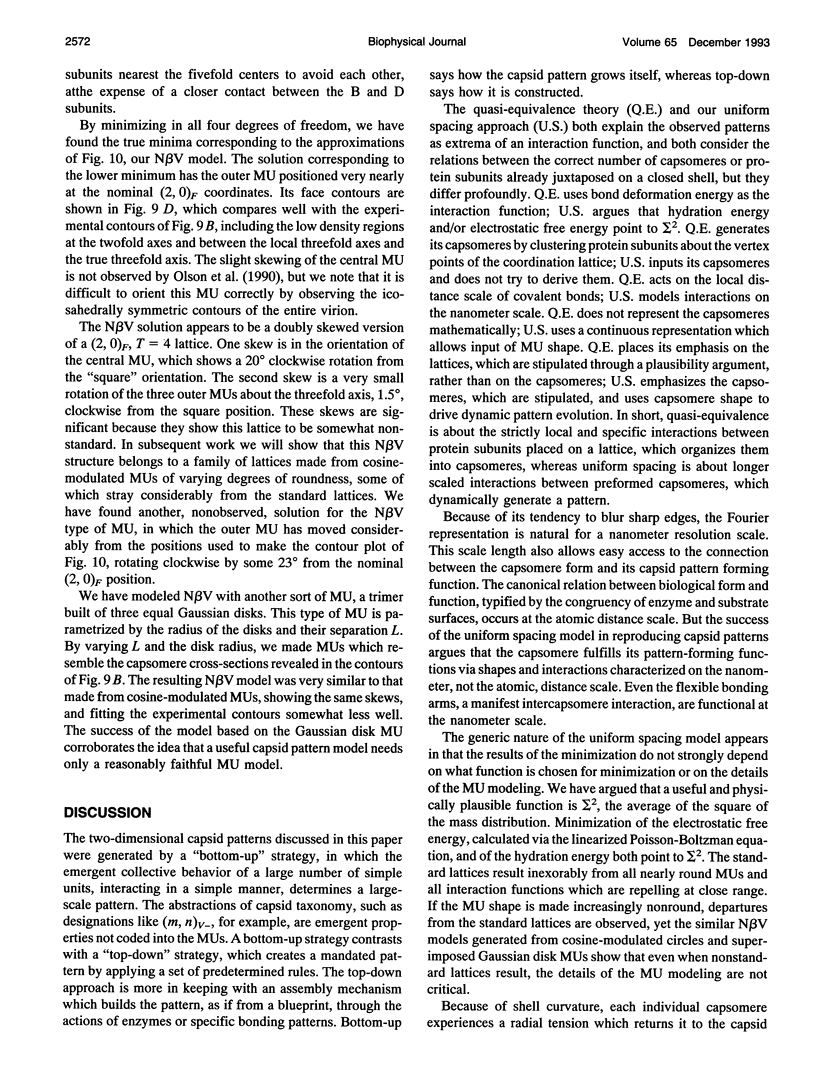

The capsids of the spherical viruses all show underlying icosahedral symmetry, yet they differ markedly in capsomere shape and in capsomere position and orientation. The capsid patterns presented by the capsomere shapes, positions, and orientations of three viruses (papilloma, SV40, and N beta V) have been generated dynamically through a bottom-up procedure which provides a basis for understanding the patterns. A capsomere shape is represented in two-dimensional cross-section by a mass or charge density on the surface of a sphere, given by an expansion in spherical harmonics, and referred to herein as a morphological unit (MU). A capsid pattern is represented by an icosahedrally symmetrical superposition of such densities, determined by the positions and orientations of its MUs on the spherical surface. The fitness of an arrangement of MUs is measured by an interaction integral through which all capsid elements interact with each other via an arbitrary function of distance. A capsid pattern is generated by allowing the correct number of approximately shaped MUs to move dynamically on the sphere, positioning themselves until an extremum of the fitness function is attained. The resulting patterns are largely independent of the details of both the capsomere representation and the interaction function; thus the patterns produced are generic. The simplest useful fitness function is sigma 2, the average square of the mass (or charge) density, a minimum of which corresponds to a "uniformly spaced" MU distribution; to good approximation, the electrostatic free energy of charged capsomeres, calculated from the linearized Poisson-Boltzmann equation, is proportional to sigma 2. With disks as MUs, the model generates the coordinated lattices familiar from the quasi-equivalence theory, indexed by triangulation numbers. Using fivefold MUs, the model generates the patterns observed at different radii within the T = 7 capsid of papilloma and at the surface of SV40; threefold MUs give the T = 4 pattern of Nudaurelia capensis beta virus. In all cases examined so far, the MU orientations are correctly found.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baker T. S., Drak J., Bina M. Reconstruction of the three-dimensional structure of simian virus 40 and visualization of the chromatin core. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jan;85(2):422–426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. S., Drak J., Bina M. The capsid of small papova viruses contains 72 pentameric capsomeres: direct evidence from cryo-electron-microscopy of simian virus 40. Biophys J. 1989 Feb;55(2):243–253. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82799-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. S., Newcomb W. W., Olson N. H., Cowsert L. M., Olson C., Brown J. C. Structures of bovine and human papillomaviruses. Analysis by cryoelectron microscopy and three-dimensional image reconstruction. Biophys J. 1991 Dec;60(6):1445–1456. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82181-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett R. M. The structure of the adenovirus capsid. II. The packing symmetry of hexon and its implications for viral architecture. J Mol Biol. 1985 Sep 5;185(1):125–143. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASPAR D. L., KLUG A. Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1962;27:1–24. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1962.027.001.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S. Molecular organization of the bacteriophage P22 coat protein shell. J Mol Biol. 1979 Jun 15;131(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng R. H., Olson N. H., Baker T. S. Cauliflower mosaic virus: a 420 subunit (T = 7), multilayer structure. Virology. 1992 Feb;186(2):655–668. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90032-k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokland T., Lindqvist B. H., Fuller S. D. Image reconstruction from cryo-electron micrographs reveals the morphopoietic mechanism in the P2-P4 bacteriophage system. EMBO J. 1992 Mar;11(3):839–846. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORNE R. W., WILDY P. Symmetry in virus architecture. Virology. 1961 Nov;15:348–373. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(61)90366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsura I. Structure and inherent properties of the bacteriophage lambda head shell. IV. Small-head mutants. J Mol Biol. 1983 Dec 15;171(3):297–317. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(83)90095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddington R. C., Yan Y., Moulai J., Sahli R., Benjamin T. L., Harrison S. C. Structure of simian virus 40 at 3.8-A resolution. Nature. 1991 Nov 28;354(6351):278–284. doi: 10.1038/354278a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljas L., Unge T., Jones T. A., Fridborg K., Lövgren S., Skoglund U., Strandberg B. Structure of satellite tobacco necrosis virus at 3.0 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1982 Jul 25;159(1):93–108. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson A. J., Bricogne G., Harrison S. C. Structure of tomato busy stunt virus IV. The virus particle at 2.9 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1983 Nov 25;171(1):61–93. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson N. H., Baker T. S., Johnson J. E., Hendry D. A. The three-dimensional structure of frozen-hydrated Nudaurelia capensis beta virus, a T = 4 insect virus. J Struct Biol. 1990 Oct-Dec;105(1-3):111–122. doi: 10.1016/1047-8477(90)90105-l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevelige P. E., Jr, Thomas D., King J. Scaffolding protein regulates the polymerization of P22 coat subunits into icosahedral shells in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1988 Aug 20;202(4):743–757. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90555-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau D. C., Parsegian V. A. Direct measurement of forces between linear polysaccharides xanthan and schizophyllan. Science. 1990 Sep 14;249(4974):1278–1281. doi: 10.1126/science.2144663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau D. C., Parsegian V. A. Direct measurement of temperature-dependent solvation forces between DNA double helices. Biophys J. 1992 Jan;61(1):260–271. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81832-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayment I., Baker T. S., Caspar D. L., Murakami W. T. Polyoma virus capsid structure at 22.5 A resolution. Nature. 1982 Jan 14;295(5845):110–115. doi: 10.1038/295110a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann M. G., Johnson J. E. Icosahedral RNA virus structure. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:533–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salunke D. M., Caspar D. L., Garcea R. L. Polymorphism in the assembly of polyomavirus capsid protein VP1. Biophys J. 1989 Nov;56(5):887–900. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82735-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarnai T. The observed form of coated vesicles and a mathematical covering problem. J Mol Biol. 1991 Apr 5;218(3):485–488. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90691-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel R. H., Provencher S. W. Three-dimensional reconstruction from electron micrographs of disordered specimens. II. Implementation and results. Ultramicroscopy. 1988;25(3):223–239. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(88)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]