Abstract

All-trans-retinoic acid (RA) treatment induces remissions in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) cases expressing the t(15;17) product, promyelocytic leukemia (PML)/RA receptor α (RARα). Microarray analyses previously revealed induction of UBE1L (ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1-like) after RA treatment of NB4 APL cells. We report here that this occurs within 3 h in RA-sensitive but not RA-resistant APL cells, implicating UBE1L as a direct retinoid target. A 1.3-kb fragment of the UBE1L promoter was capable of mediating transcriptional response to RA in a retinoid receptor-selective manner. PML/RARα, a repressor of RA target genes, abolished this UBE1L promoter activity. A hallmark of retinoid response in APL is the proteasome-dependent PML/RARα degradation. UBE1L transfection triggered PML/RARα degradation, but transfection of a truncated UBE1L or E1 did not cause this degradation. A tight link was shown between UBE1L induction and PML/RARα degradation. Notably, retroviral expression of UBE1L rapidly induced apoptosis in NB4 APL cells, but not in cells lacking PML/RARα expression. UBE1L has been implicated directly in retinoid effects in APL and may be targeted for repression by PML/RARα. UBE1L is proposed as a direct pharmacological target that overcomes oncogenic effects of PML/RARα by triggering its degradation and signaling apoptosis in APL cells.

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) (FAB M3) cases express the oncogenic product of the t(15;17) rearrangement, promyelocytic leukemia (PML)/retinoic acid receptor α (RARα), as reviewed in refs. 1 and 2. All-trans-retinoic acid (RA) treatment causes complete remissions in these APL cases through induction of leukemic cell differentiation (1, 2). A hallmark of RA response in APL is PML/RARα degradation that reverses PML/RARα oncogenic effects (3–8). Proteasomal inhibitors prevent PML/RARα proteolysis, despite RA treatment, implicating a proteasome-dependent pathway in this degradation (5–8). PML/RARα expression results in dominant-negative transcriptional repression (3, 4). This repression is antagonized by pharmacological RA dosages that overcome inhibitory effects on transcription of the N-Cor/SMRT corepressor complex that has histone deacetylase activity (9, 10). RA treatment recruits a coactivator complex that stimulates transcription, resulting in activation of target genes (9, 10).

Identification of RA target genes is the next step in understanding the molecular basis of RA response in APL. Recent microarray analysis of RA-treated NB4 APL cells reported the prominent induction of UBE1L (ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1-like) (11). We examined in this study this homolog of the ubiquitin-degradation pathway. In APL, the proteasome-dependent degradation of PML/RARα has been proposed as a mechanism by which RA overcomes PML/RARα oncogenic effects. Evidence is now provided for UBE1L as a retinoid target in APL that antagonizes PML/RARα oncogenic effects by triggering PML/RARα degradation.

A direct relationship was found between retinoid induction of UBE1L and degradation of PML/RARα. Examination of RA-resistant APL cells indicated that RA induction of UBE1L did not occur, further implicating UBE1L in retinoid response. Expression of E1 (that has homology to UBE1L) was not increased by RA treatment. PML/RARα cotransfected with UBE1L (but not E1) led to PML/RARα degradation without RA treatment. This finding indicated specificity of UBE1L for triggering PML/RARα degradation. Results were extended by using a UBE1L reporter assay to explore how RA regulated UBE1L. Retroviral transduction of UBE1L caused apoptosis only in cells that expressed PML/RARα. Findings that will be presented here implicate UBE1L as a candidate RA target gene responsible for a major retinoid effect in APL, degradation of PML/RARα. Retinoid induction of UBE1L overcame PML/RARα leukemogenic actions by triggering its degradation. The consequence of this action is the promotion of apoptosis that further enhances the antioncogenic effects of UBE1L in APL.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Induction Protocol.

RA and DMSO were purchased from Sigma. Stock RA (10 mM) solutions were dissolved in DMSO, stored in liquid nitrogen, and used in the dark during experiments. RPMI 1640 and α-MEM were purchased from Cellgro/Mediatech, Herndon, VA. The NB4 APL cell line expresses PML/RARα (12). NB4-S1 and NB4-R1 are RA-sensitive and RA-resistant clones of NB4 cells, respectively (13). These cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS as described (13). Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 5% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 units/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37°C. Human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) were cultured in serum-free LHC-9 medium (Biofluids, Rockville, MD) by using established techniques (14, 15). HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 units/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37°C.

Differentiation and Apoptosis Markers.

NB4 cell differentiation was scored by using the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction assay (13, 16, 17). Transductants were identified by green fluorescent protein (GFP) coexpression. Apoptosis was scored by using established techniques and Hoechst staining of transductants that coexpressed GFP (16–18). Digital images were collected by using an Olympus 1×70 inverted microscope, a cooled charge-coupled device camera, and a MiraCal Pro Single Cell Imaging System (Olympus LSR Research, Melville, NY).

Plasmid Constructs.

A full-length UBE1L cDNA containing plasmid was obtained from C. H. C. M. Buys (University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands). A. Schwartz (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis) provided the pGEM-HA-1E1 plasmid, and pSG5-HA-1E1 was constructed by cloning the HA-1E1 fragment into the pSG5 expression vector. An EcoR1 fragment containing the UBE1L cDNA was cloned into EcoRI-retricted pSG5 to yield the pSG5-UBE1L plasmid. A truncated UBE1L plasmid (UBE1L-T) removed an EclXI/SnaBI fragment from pSG5-UBE1L that deleted a large portion of the carboxyl terminus of UBE1L. The hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged PML/RARα expression vector was constructed from pCMX-PML/RARα and pCMV-HA (CLONTECH) plasmids. The pGL3-UBE1L-Luc reporter plasmid contained the luciferase gene and 5′ promoter elements of UBE1L. It was constructed by using an amplified fragment of the UBE1L promoter derived from NB4-S1 genomic DNA (forward primer: 5′-GCAACCGAGTGAGACTGTCT-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GCGCTCAGAGATAGGGTCTTT-3′). DNA sequence analysis confirmed this cloning.

UBE1L mRNA Expression Assays.

UBE1L mRNA expression was assessed by a reverse transcription–PCR assay and established methods (3). The forward primer was 5′-AGGTGGCCAAGAACTTGGTT-3′, and reverse primer was 5′CACCACCTGGAAGTCCAACA-3′. The PCR product was visualized by probing with a 32P-labeled primer. Results were confirmed independently by Northern analysis using a 1.0-kb EcoRI/NcoI-radiolabeled UBE1L probe and standard techniques (14). This probe had limited homology to E1.

Generation of Anti-UBE1L Antisera.

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were independently derived (Covance Research Products, Denver, PA) against UBE1L by using one peptide within the amino terminus (DCDPRSIHVREDGSLEIGD) and a second peptide within the carboxyl terminus (PGSQDWTALRELLKLL). Specificities of these antisera were confirmed by immunoblot analyses of UBE1L-transfected CHO cells.

Immunoblot Analysis.

Immunoblot analyses were performed by using established techniques (14, 19). Anti-RARα antibody was provided by P. Chambon (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Strasbourg, France) to detect PML/RARα (16, 17). An anti-HA mAb was purchased (Babco, Richmond, CA) as was an anti-actin polyclonal antibody, C-11 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Transfection Procedure.

Transient transfection of BEAS-2B or CHO cells was accomplished by using Effectene and transfection methods as per the manufacturer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). A β-galactosidase reporter plasmid (pCH111) was cotransfected to control for transfection efficiencies.

Retroviral Constructs and Transduction Procedures.

Murine stem cell virus (MSCV)-IRES (internal ribosome entry sequence)-GFP was constructed to express UBE1L cDNA by cloning an EcoRI fragment from pSG5-UBE1L into an EcoRI site of this retroviral vector. Restriction endonuclease and partial DNA sequence analyses confirmed cloning was in the desired orientation. A vector without an insert served as a control. For each vector, 10 μg was transiently transfected by using calcium phosphate precipitation along with the CellPhect Transfection kit (Amersham Pharmacia). The 293GPG packaging cell line was provided by R. Mulligan (Harvard University, Cambridge). Forty-eight hours later, viral supernatant from 293GPG transfectants (20) was used to transduce NB4-S1 or HeLa cells in the presence of 6 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma). Twenty-four hours later, FACS analysis was performed, and cells positive for GFP expression were harvested by sorting and used for these experiments.

Results

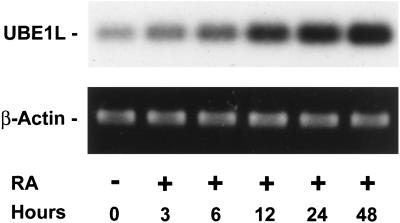

RA Induction of UBE1L mRNA.

UBE1L mRNA was reported as induced after RA treatment of APL cells (11). The kinetics of this induction was studied in RA-sensitive NB4-S1 APL cells by using a reverse transcription–PCR assay (Fig. 1). UBE1L mRNA expression increased rapidly after RA treatment. UBE1L induction occurred by 3 h after 10 μM RA treatment (Fig. 1). This was independently confirmed by Northern analysis (data not shown) and after 1 μM RA treatment by reverse transcription–PCR assay (data not shown). In contrast, UBE1L expression was not induced during the same time period, despite 10 μM RA treatment of the RA-resistant NB4-R1 cell line (data not shown). Differential UBE1L expression implicated a role for UBE1L in regulating growth or differentiation of APL cells.

Figure 1.

UBE1L mRNA induction in RA-treated NB4-S1 APL cells. UBE1L expression was induced within 3 h of RA treatment in this reverse transcription–PCR assay, implicating a role for UBE1L in RA response of APL cells. No appreciable change in UBE1L expression occurred in RA-untreated controls. β-actin expression confirmed similar loading in each lane.

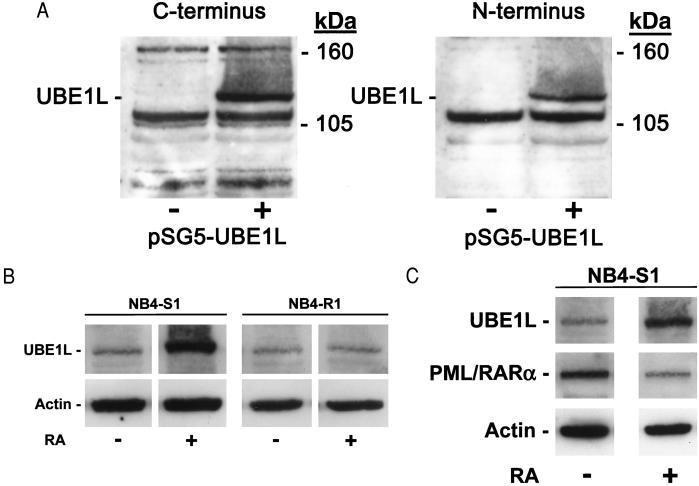

RA Induction of UBE1L Protein.

UBE1L immunoblot expression was examined. As discussed in Materials and Methods, immunogenic peptides generated independent polyclonal antisera recognizing the amino or carboxyl termini of UBE1L protein. CHO cells that did not basally express UBE1L mRNA (data not shown) were transfected with a full-length UBE1L cDNA or an insertless vector. CHO cells transfected with UBE1L expressed UBE1L protein whereas cells transfected with an insertless vector did not express this 112-kDa species (Fig. 2A). UBE1L immunoblot expression profiles were compared in RA-sensitive versus RA-resistant NB4 cells. UBE1L protein was basally expressed at low levels in both cell lines. It was induced only after RA (1 μM) treatment of NB4-S1 APL cells (Fig. 2B). These findings implicated a direct relationship between UBE1L induction and effective retinoid treatment of APL cells.

Figure 2.

Immunoblot assays for UBE1L expression. (A) Immunogenic peptides generated anti-UBE1L polyclonal antisera recognizing, respectively, the carboxyl or amino termini of human UBE1L. UBE1L immunoblot assays were performed in transfected CHO cells. The 112-kDa UBE1L species was detected by using either antisera. + and − refer to transfection (+) of pSG5-UBE1L or an insertless control pSG5 vector (−). Molecular mass size markers are depicted. (B) UBE1L protein was induced by 24 h of RA (1 μM) treatment of NB4-S1 but not NB4-R1 cells, as assayed by using the anti-UBE1L amino terminus antibody. (C) An inverse relationship existed between UBE1L and PML/RARα protein expression before and after RA treatment of NB4-S1 cells. UBE1L expression was induced and PML/RARα expression was repressed after 24 h of RA treatment of these cells. In B and C, actin expression confirmed similar protein loading in each lane.

A hallmark of RA response in APL is PML/RARα degradation (5–8). RA treatment repressed PML/RARα expression in NB4-S1, but not in NB4-R1 cells (13). To examine the relationship in APL cells between UBE1L and PML/RARα expression, immunoblot expression profiles for these species were examined before and after RA (1 μM) treatment of NB4-S1 cells. An inverse relationship was evident between UBE1L and PML/RARα expression both before and after RA treatment (Fig. 2C). This finding suggested a direct role for PML/RARα in regulating UBE1L expression.

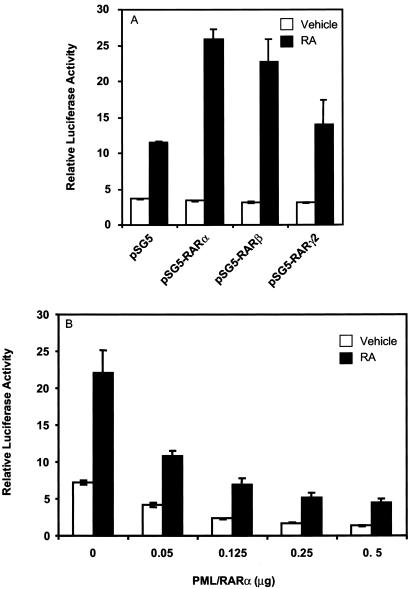

Induction of UBE1L Reporter Activity.

To examine further the potential for PML/RARα to affect UBE1L, 1.3 kb of the UBE1L promoter upstream of the ATG translation start site was cloned into a luciferase-containing reporter plasmid. This reporter plasmid was transfected into CHO cells in the presence and absence of RA treatment (Fig. 3A). This fragment of the UBE1L promoter was capable of mediating transcriptional response to RA in a retinoid receptor-selective manner.

Figure 3.

UBE1L reporter assays in CHO cells cotransfected with RARs or PML/RARα. (A) Cotransfection of RARs activated this UBE1L reporter plasmid, but to differing degrees after RA (10 μM) treatment. (B) PML/RARα cotransfection with the UBE1L reporter plasmid inhibited transcriptional activation in a dose-dependent manner. PML/RARα inhibition was antagonized by RA (1 μM) treatment. In this experiment, pSG5-RARα was cotransfected (0.125 μg) because this retinoid receptor most efficiently induced UBE1L transcriptional activity, as shown in A. SD bars are depicted.

The relationship between PML/RARα and activity of this UBE1L reporter plasmid was examined when PML/RARα was cotransfected with this reporter plasmid. Cotransfection of PML/RARα with RARα led to a marked repression of UBE1L reporter activity before and after RA (1 μM) treatment. This inhibition depended on the dosage of transfected PML/RARα (Fig. 3B). In each experiment, a cotransfected β-galactosidase reporter plasmid was used to control for tranfection efficiencies. No appreciable effect of PML/RARα on the transcriptional activity of the β-galactosidase reporter plasmid was observed (data not shown). Thus, PML/RARα repressed activity of this UBE1L reporter plasmid.

Lack of E1 Induction by RA.

UBE1L has homology to E1. Whether RA treatment induced E1 expression in APL cells was examined. E1 mRNA was not induced after RA (1 μM) treatment of NB4-S1 cells (data not shown), indicating different effects of RA on expression of UBE1L and E1. The ability of UBE1L or E1 to trigger PML/RARα degradation was next examined.

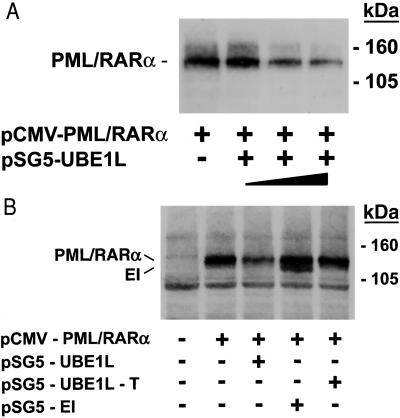

UBE1L Triggers PML/RARα Degradation.

Cotransfection assays used cells that did not express PML/RARα. Experiments used CHO cells that did not express UBE1L and BEAS-2B cells that expressed low levels of UBE1L, but could be readily transfected with RARs or PML/RARα. Degradation of transfected PML/RARα was triggered by UBE1L in a dose-dependent manner after transfection of CHO cells (data not shown) or BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 4A). This degradation of PML/RARα occurred in the absence of RA treatment. Transfection of a truncated UBE1L (pSG5-UBE1L-T) did not cause PML/RARα degradation (Fig. 4B). To establish that PML/RARα degradation was a distinct UBE1L function, E1 was transfected into BEAS-2B cells with PML/RARα. E1 did not cause PML/RARα degradation (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

UBE1L transfection triggered PML/RARα degradation. (A) Cotransfection of PML-RARα (HA-tagged) with UBE1L led to PML/RARα degradation. This depended on the transfected UBE1L dosage (closed triangle). Molecular mass size markers are depicted. The symbols + and − refer to transfection of PML/RARα or UBE1L, respectively. (B) Cotransfection of E1 (pSG5-E1) or a truncated UBE1L (pSG5-UBE1L-T) did not cause PML/RARα degradation. Both PML/RARα and E1 were HA-tagged and an anti-HA antibody was used, accounting for dual detection in the fourth lane. Intact UBE1L was required for this PML/RARα degradation. + and − refer to transfection of pCMV-PML/RARα, pSG5-UBE1L, pSG5-UBE1L-T, or pSG5-E1, respectively. Molecular mass size markers are displayed.

UBE1L Expression Triggers Apoptosis in APL Cells.

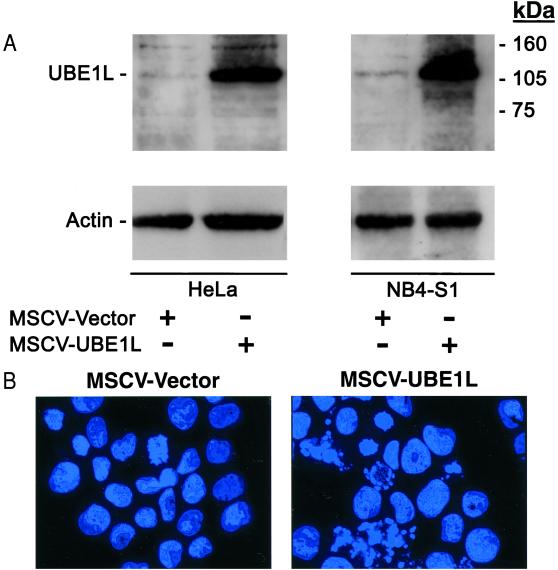

Transfection of UBE1L, but not E1, led to PML/RARα degradation even without RA treatment. It was next examined whether engineered overexpression of UBE1L in APL cells would alter the growth or differentiation state of these cells. To accomplish this, retroviral vectors (20) were constructed to express UBE1L or no insert. Coexpressed GFP was used to enrich for retroviral-expressing cells after FACS sorting. HeLa cells, which do not express PML/RARα and basally express UBE1L at low levels (Fig. 5A and data not shown), were used as a control for these experiments because retroviral transduction conditions were previously optimized in these cells. UBE1L overexpression was engineered independently in NB4-S1 and HeLa cells (Fig. 5A) using the described retroviral transduction method. As a control, an insertless control vector was independently introduced into these cell lines, as confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 5A). A striking difference in biological effects was observed after transduction of UBE1L into NB4-S1 versus HeLa cells. UBE1L overexpression in NB4-S1 cells resulted in the rapid induction of apoptosis as shown by the Hoechst staining of transduced cells (Fig. 5B). Three independent fields were examined for the insertless control NB4-S1 transfectants and 5.1% of these cells were apoptotic. Analysis of UBE1L-transduced NB4-S1 cells revealed a high proportion (39.7%) of apoptotic cells. These transductants did not exhibit morphological evidence of leukemic cell maturation. This lack of induced differentiation was confirmed by the absence of NBT-positive cells (Table 1). Notably, promotion of apoptosis was not observed in HeLa cells transduced with either the UBE1L or insertless retroviral vector (data not shown). Thus, UBE1L transduction preferentially triggered apoptosis in PML/RARα-expressing cells.

Figure 5.

(A) UBE1L immunoblot expression in HeLa and NB4-S1 cells independently transduced with retroviral vectors that expressed UBE1L or no insert. Lanes represent HeLa cells 7 days after transduction with an insertless retroviral vector (first lane) or UBE1L retroviral vector (second lane); NB4-S1 cells 5 days after transduction with an insertless retroviral vector (third lane) or the UBE1L retroviral vector (fourth lane). UBE1L expression in MSCV-UBE1L transductants was increased over that in HeLa or NB4-S1 cells after introduction of the MSCV vector. Actin expression confirmed similar protein loading. Molecular mass size markers are depicted. (B) UBE1L retroviral expression triggered apoptosis in NB4-S1 but not HeLa cells. The control vector (MSCV-Vector) was expressed in NB4-S1 cells without observed growth or differentiation effects (Left and Table 1). In marked contrast, when UBE1L (MSCV-UBE1L) was introduced, rapid induction of NB4-S1 cell death occurred through triggering of apoptosis as shown by appearance of fragmented nuclei in Hoechst-stained cells (Right and text). Representative fields are depicted. This was not observed after introduction of the control (MSCV-Vector) or UBE1L retroviral vector (MSCV-UBE1L) into HeLa cells that do not express PML/RARα (data not shown).

Table 1.

NBT maturation assays performed on NB4-S1 APL cells after 5 days of treatment with RA (1 μM) [designated +RA] or vehicle (DMSO) [designated −RA] or transduction of the UBE1L retrovirus, [designated +UBE1L] as compared to transduction of the same retrovirus without an insert [designated −UBE1L]

| Cell line | NBT, % |

|---|---|

| NB4-S1 (−RA) | 0 |

| NB4-S1 (+RA) | 92 |

| NB4-S1 (−UBE1L) | 0 |

| NB4-S1 (+UBE1L) | 0 |

NBT-positive NB4-S1 cells appeared after RA treatment, but transduction of UBE1L or a control vector did not induce morphological maturation (data not shown) or a positive NBT assay. For each assay, 200 cells were scored and percentages of NBT-positive cells are shown.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that UBE1L is a candidate RA target gene in APL. Several lines of evidence supported this view. UBE1L expression was induced by RA treatment of differentiation sensitive, but not resistant APL cells (Figs. 1 and 2). The UBE1L promoter was capable of mediating transcriptional response to RA in a retinoid receptor-selective manner. It is not known whether these transcriptional effects are direct, but it is notable that the UBE1L promoter contained several putative RA response element half-sites. PML/RARα inhibited UBE1L reporter activity (Fig. 3). A hallmark of RA response in APL is PML/RARα degradation. Direct evidence for UBE1L involvement in this degradation came from experiments where UBE1L and PML/RARα cotransfection led to PML/RARα degradation (Fig. 4). Preliminary findings indicated that the PML domain of PML/RARα was more sensitive to degradation by UBE1L than the RARα domain (I.P.-R., unpublished work). These UBE1L effects were specific because RA treatment failed to induce E1 expression and cotransfection of E1 with PML/RARα did not cause PML/RARα degradation. Thus, UBE1L and E1 functions are distinct. These results were consistent with a report that demonstrated different biochemical properties of UBE1L and E1 regarding complex formation (21).

Findings reported here are consistent with an antagonistic relationship between UBE1L and PML/RARα in APL. To determine UBE1L biological effects in APL cells, UBE1L was overexpressed in these cells by using a retroviral approach (Fig. 5). Whereas an insertless control retroviral vector could be readily expressed in NB4-S1 cells, the UBE1L retroviral vector could not because apoptosis was rapidly triggered. This occurred without evidence for induced maturation (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Induction of apoptosis was so rapid that examination of the mechanisms signaling apoptosis was precluded. These effects were specific to APL cells because transduction of the UBE1L or control retroviral vector did not trigger apoptosis in HeLa cells that lacked PML/RARα expression.

These findings were not unexpected. Previous work with hammerhead ribozymes that target PML/RARα indicated how PML/RARα degradation signaled apoptosis but not differentiation in transfected APL cells that were either RA-sensitive or RA-resistant (16, 17). Catalytic ribozymes must be introduced into APL cells for their overexpression to trigger apoptosis. This requirement could limit therapeutic activity of these ribozymes even though they might exert limited biological effects beyond PML/RARα catalysis. In contrast, UBE1L induction by RA should be clinically achievable. Whether RA is the optimal agent to induce UBE1L expression in APL cells is not yet known. A pharmacological agent that preferentially induced UBE1L expression might exhibit therapeutic activity in APL.

RA treatment signaled myeloid differentiation and degradation of PML/RARα without triggering appreciable apoptosis (5–8, 16, 17). Transcriptional activation by RA treatment likely exerts diverse effects in APL cells in addition to PML/RARα degradation and myeloid differentiation. Regarding PML/RARα degradation after RA treatment, previous work indicated how this could occur through proteasomal as well as caspase-dependent pathways (7, 8). These pathways are reported as linked in some cell contexts, including thymocytes and sympathetic neurons (22, 23). Perhaps RA treatment links these pathways in APL cells.

Future work will determine the biochemical relationship between UBE1L and PML/RARα degradation. Findings reported here are consistent with previous work indicating that RA promoted ubiquitination and cyclin degradation during retinoid-induced differentiation or growth suppression (14, 15, 19). Recent evidence highlighted the tumor-selective death ligand, TRAIL, in induction of apoptosis in APL cells (24). It would be interesting to determine whether UBE1L plays a role in TRAIL-mediated death signaling by retinoids.

Arsenic trioxide treatment also caused apoptosis and PML/RARα degradation without prominent induction of differentiation in APL (8, 25, 26). It was reported to trigger PML/RARα proteolysis through covalent modification with PIC-1/SUMO (26). Arsenic trioxide proteolytic effects could differ from those of RA treatment. Consistent with this view, preliminary findings indicated that UBE1L induction did not occur after arsenic trioxide treatment of NB4 cells (S.K., unpublished work). UBE1L retroviral expression in APL cells might confer more limited biological effects than treatments with either arsenic trioxide or RA. UBE1L biochemical targets in APL should be determined. Agents that selectively induce UBE1L expression in APL could cause antileukemic effects by triggering PML/RARα degradation and apoptosis, perhaps without undesirable clinical toxicities that complicate RA or arsenic trioxide treatments.

Few candidate RA target genes have been reported in APL. GOS2 is a putative RA target gene identified by microarray analysis of APL cells (11). The precise function of G0S2 is not yet known, but it was first identified as regulated during the cell cycle (27), suggesting a role in cell cycle control. Another candidate retinoid target gene is the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein ɛ (C/EBPɛ) that contributes to retinoid transcriptional effects in APL (28). In contrast to these species, UBE1L could account for an important posttranscriptional retinoid effect in APL, PML/RARα degradation. An in-depth examination of retinoid-regulated species identified by microarray analyses (11) would provide a fuller understanding of the acute promyelocytic differentiation program.

E1 and UBE1L exhibited distinct functions. Based on findings presented here and previous work (21), UBE1L may have an important biological role beyond APL. UBE1L maps to chromosome 3p, a region frequently deleted in lung cancers; UBE1L repression is frequent in lung cancers (29, 30) where it may exert a tumor suppressive effect. This possibility, when coupled with the expression pattern of UBE1L in human tissues or tumor cells (ref. 31 and I.P.-R., unpublished work) and results of UBE1L retroviral transduction reported here, indicates that UBE1L might regulate growth of normal or neoplastic cells.

How UBE1L triggers PML/RARα degradation should be determined. It has not been excluded that UBE1L affects transcription, translation, or PML/RARα stability, independent of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. Perhaps UBE1L complexes with another protein that would cause PML/RARα degradation. In this regard, complex of UBE1L to the ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 has been reported (21). Perhaps RA promotes ISG15-dependent modification of PML/RARα and thereby targets PML/RARα for degradation.

In summary, this study identified UBE1L as a candidate retinoid target gene in APL. This view was based on the rapid induction of UBE1L after RA treatment of differentiation sensitive but not resistant NB4 APL cells. An antagonistic relationship between UBE1L and PML/RARα was uncovered. PML/RARα oncogenic effects were overcome by RA induction of UBE1L that triggers PML/RARα degradation. Apoptosis was signaled when UBE1L was introduced into APL but not control cells that lacked PML/RARα expression. UBE1L triggered PML/RARα degradation and antioncogenic effects, but did not signal a maturation response. Differentiation may depend on other target genes. Future work will determine which agents optimally augment UBE1L expression and how UBE1L causes PML/RARα degradation. UBE1L could play an important biological role beyond APL. In APL, retinoid induction of UBE1L abolished PML/RARα leukemogenic effects by targeting it for degradation. This triggered apoptosis, further enhancing antioncogenic actions of UBE1L in APL. Taken together, these findings indicate how UBE1L induction accounted for a major retinoid therapeutic effect in APL, the degradation of PML/RARα.

Acknowledgments

The NB4 APL line was obtained from Dr. M. Lanotte (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Paris). We thank Dr. R. Mulligan for providing the 293GPG packaging cell line, Dr. A. Eastman (Dartmouth Medical School) for providing the CHO cell line, Dr. C. Harris (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for providing the BEAS-2B cell line, Dr. C. H. C. M. Buys for providing the UBE1L cDNA, Dr. A. Schwartz for providing the pGEM-HA-1E1 plasmid, Dr. B. Sorrentino (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN) for providing the MSCV vector, and Dr. P. Chambon for providing the anti-RARα antibody. We thank Drs. R. Craig and J. Vrana (Dartmouth Medical School) for assistance regarding apoptosis and maturation assays and Dr. B. Stanton and Mr. K. DiPetrillo for consultation regarding confocal microscopic imaging. We thank Mr. G. Ward and Dr. A. Givens of the Herbert C. Engelbert Cell Analysis Laboratory (Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center) for assistance in FACS experiments and Dr. M. Spinella (Dartmouth Medical School) for his consultation. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1-CA62275 (to E.D.) and partly by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1-CA87546 (to E.D.) and National Institutes of Health Grant RO1-HL52243 (to C.H.L.). S.J.F. was supported in part by the Lance Armstrong Award. M.J.N. is a Fellow of the Alfred J. Ryan Foundation and a recipient of the Rosalind Borison Memorial Award.

Abbreviations

- APL

acute promyelocytic leukemia

- PML

promyelocytic leukemia

- RARα

retinoic acid receptor α

- RA

all-trans retinoic acid

- UBE1L

ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1-like

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- NBT

nitroblue tetrazolium

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- HA

hemagglutinin

- MSCV

murine stem cell virus

References

- 1.Nason-Burchenal K, Dmitrovsky E. In: Molecular Biology of Cancer. 1st Ed. Bertino J R, editor. San Diego: Academic; 1996. pp. 1547–1560. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nason-Burchenal K, Dmitrovsky E. In: Retinoids: The Biochemical and Molecular Basis of Vitamin A and Retinoid Action. Nau H, Blaner W, editors. Berlin: Springer; 1999. pp. 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kakizuka A, Miller W H, Jr, Umesono K, Warrell R P, Jr, Frankel S R, Murty V V V S, Dmitrovsky E, Evans R M. Cell. 1991;68:663–674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90112-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Thé H, Lavau C, Marchio A, Chomienne C, Degos L, Dejean A. Cell. 1991;68:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90113-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida H, Kitamura K, Tanaka K, Omura S, Miyazaki T, Hachiya T, Ohno R, Naoe T. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2945–2948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raelson J V, Nervi C, Rosenauer A, Benedetti L, Monczak Y, Pearson M, Pelicci P G, Miller W H., Jr Blood. 1996;88:2826–2832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nervi C, Ferrara F F, Fanelli M, Rippo M R, Tomassoni B, Ferrucci P F, Ruthardt M, Gelmetti V, Gambaeorti-Passerini C, Diverio D, et al. Blood. 1998;92:2244–2251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu J, Gianni M, Kopf E, Honore N, Chelbi-Alix M, Koken M, Quignon F, Rochette-Egly C, de Thé H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14807–14812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin R J, Nagy L, Inoue S, Shao W, Miller W H, Jr, Evans R M. Nature (London) 1998;391:811–814. doi: 10.1038/35895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grignani F, de Matteis S, Nervi C, Tomassoni L, Gelmetti V, Cioce M, Fanelli M, Ruthardt M, Ferrara F F, Zamir I, et al. Nature (London) 1998;391:815–818. doi: 10.1038/35901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamayo P, Slonim D, Mesirov J, Zhu Q, Kitareewan S, Dmitrovsky E, Lander E S, Golub T R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2907–2912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanotte M, Martin-Thouvenin V, Najman S, Balerini P, Valensi F, Berger R. Blood. 1991;77:1080–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nason-Burchenal K, Maerz W, Albanell J, Allopenna J, Martin P, Moore M A S, Dmitrovsky E. Differentiation. 1997;61:321–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1997.6150321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langenfeld J, Kiyokawa H, Sekula D, Boyle J, Dmitrovsky E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12070–12074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle J O, Langenfeld J, Lonardo F, Sekula D, Reczek P, Rusch V, Dawson M I, Dmitrovsky E. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:373–379. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nason-Burchenal K, Allopenna J, Bègue A, Stéhelin D, Dmitrovsky E, Martin P. Blood. 1998;92:1758–1767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nason-Burchenal K, Takle G, Pace U, Flynn S, Allopenna J, Martin P, George S T, Goldberg A R, Dmitrovsky E. Oncogene. 1998;17:1759–1768. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stadheim T A, Xiao H, Eastman A. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1533–1540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spinella M J, Freemantle S J, Sekula D, Chang J H, Christie A J, Dmitrovsky E. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22013–22018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ory D S, Neugeboren B A, Mulligan R C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11400–11406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan W, Krug R M. EMBO J. 2001;20:362–371. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadoul R, Fernandez P-A, Quiquerez A-L, Martinou I, Maki M, Schroter M, Becherer J D, Irmler M, Tschopp J, Martinou J C. EMBO J. 1996;15:3845–3852. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimm L M, Goldberg A L, Poirier G G, Schwartz L M, Osborne B A. EMBO J. 1996;15:3835–3844. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altucci L, Rossin A, Raffelsberger W, Reitmair A, Chomienne C, Gronemeyer H. Nat Med. 2001;7:680–686. doi: 10.1038/89050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen Z-X, Chen G Q, Ni J H, Li X S, Xiong S M, Qui Q Y, Zhu J, Tang W, Sun G L, Yang K Q, et al. Blood. 1997;89:3354–3360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sternsdorf T, Puccetti E, Jensen K, Hoelza D, Will H, Ottmann O G, Ruthardt M. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5170–5178. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell L, Forsdyke D R. DNA Cell Biol. 1991;10:581–591. doi: 10.1089/dna.1991.10.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park D J, Chumakov A M, Vuong P T, Chih D Y, Gombart A F, Miller W H, Jr, Koeffler H P. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1399–1408. doi: 10.1172/JCI2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kok K, Hofstra R, Pilz A, van den Berg A, Terpstra P, Buys C H C M, Carritt B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6071–6075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carritt B, Kok K, van den Berg A, Osinga J, Pilz A, Hofstra R M W, Davis M B, van der Veen A Y, Rabbitts P H, Gulati K, Buys C H C M. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1536–1541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLaughlin P M J, Helfrich W, Kok K, Mulder M, Hu S W, Brinker M G L, Rutters M H J, de Leij L F M H, Buys C H C M. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:871–876. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000315)85:6<871::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]