Abstract

Considerable evidence argues that consumption of beef products from cattle infected with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) prions causes new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. In an effort to prevent new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, certain “specified offals,” including neural and lymphatic tissues, thought to contain high titers of prions have been excluded from foods destined for human consumption [Phillips, N. A., Bridgeman, J. & Ferguson-Smith, M. (2000) in The BSE Inquiry (Stationery Office, London), Vol. 6, pp. 413–451]. Here we report that mouse skeletal muscle can propagate prions and accumulate substantial titers of these pathogens. We found both high prion titers and the disease-causing isoform of the prion protein (PrPSc) in the skeletal muscle of wild-type mice inoculated with either the Me7 or Rocky Mountain Laboratory strain of murine prions. Particular muscles accumulated distinct levels of PrPSc, with the highest levels observed in muscle from the hind limb. To determine whether prions are produced or merely accumulate intramuscularly, we established transgenic mice expressing either mouse or Syrian hamster PrP exclusively in muscle. Inoculating these mice intramuscularly with prions resulted in the formation of high titers of nascent prions in muscle. In contrast, inoculating mice in which PrP expression was targeted to hepatocytes resulted in low prion titers. Our data demonstrate that factors in addition to the amount of PrP expressed determine the tropism of prions for certain tissues. That some muscles are intrinsically capable of accumulating substantial titers of prions is of particular concern. Because significant dietary exposure to prions might occur through the consumption of meat, even if it is largely free of neural and lymphatic tissue, a comprehensive effort to map the distribution of prions in the muscle of infected livestock is needed. Furthermore, muscle may provide a readily biopsied tissue from which to diagnose prion disease in asymptomatic animals and even humans.

Prions cause neurodegenerative diseases, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), chronic wasting disease (CWD), and scrapie in mammals (1). The only known constituent of the infectious prion is an aberrant isoform (PrPSc) of the normal cellular (PrPC) prion protein (PrP). PrPC is a cell-surface glycoprotein, the expression of which is necessary for the production of prions (2, 3). In animals with clinical signs of scrapie, the highest levels of prions are found in the brain and spinal cord, but other tissues, particularly those of the reticuloendothelial system, exhibit substantial prion titers (4, 5).

It is important that animal tissues bearing high prion titers be excluded from the human food supply. Transmission of prions by oral ingestion of infected tissues is well documented in rodents and more recently in cattle and sheep (6–8). The efficiency of transmission of prion disease between species is governed by a phenomenon commonly known as the “species barrier.” This barrier is influenced by differences in the amino acid sequence of PrP between the species (9), but recent data clearly demonstrate that the barrier to prion transmission between any two species also depends on the particular prion strain (10). As yet, a reliable procedure of experimentally or theoretically predicting the barrier to prion transmission from prion-infected animals to humans does not exist. Although BSE prions have been transmitted to teenagers and young adults from infected cattle (10, 11) and kuru was transmitted among humans by ritualistic cannibalism (12, 13), it remains unclear whether cervid prions in North America have been transmitted to humans (14, 15). Animal muscle composes a substantial portion of the human diet, but whether prions can be found in muscle has not been thoroughly examined using sensitive assays (16–19).

We report here that prions propagate and accumulate in skeletal muscle in a region-specific manner, and at levels much higher than have been generally assumed (19–21).

Materials and Methods

Detection of PrPSc in Skeletal Muscle.

Muscle tissue was pulverized under liquid nitrogen, suspended to 10% in PBS, then subjected to 10 strokes of a Potter–Elvehjem homogenizer. For protease digestion, an equal volume of 4% Sarkosyl in PBS was added to 1–4 ml of the homogenate, and proteinase K (PK) was added at a ratio of 1:50, PK to homogenate protein. The sample was incubated at 37°C for 1 h with rocking, followed by the addition of a proteinase inhibitor mixture (Complete, Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Phosphotungstic acid precipitation was performed as described (22), except that samples were subjected to centrifugation at 20,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h in a fixed angle rotor.

Western blotting and PrP detection were performed as described (23). Relative amounts of brain and muscle PrPSc were determined by comparing densities of bands obtained from serial dilutions of brain homogenate to bands representing muscle-derived PrPSc on Western blots. NIH image software analysis of digitized images of photographic film was used to quantify band densities and interpolate PrPSc amounts in muscle relative to those in brain. Mean values obtained from analyses of several exposures of differing durations are reported.

For PrPSc detection using ELISA, PK-digested muscle homogenates were denatured with 6 M guanidine thiocyanate after centrifugation described above. Subsequently denatured homogenates were immobilized on the surface of a 96-well Immulon II ELISA plate (Dynex, Franklin, MA) and the rest of the surface was blocked by 3% BSA. Detection of PrPSc was carried out by a 2-h incubation of HuM-D18 Ab (24) in 1× Tris buffered saline, followed by 1-h incubation with goat anti-human Fab Ab conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Pierce). An additional 1-h incubation used 1-step pNPP (Pierce), an alkaline phosphatase substrate for the development of a colored product, which can be measured at 405 nm.

Inoculation of Mice with Prions.

Mice were inoculated i.m. or i.p. with 50 μl of a 10% pooled brain homogenate either from Syrian hamsters inoculated with Sc237 prions or from CD-1 mice inoculated with Rocky Mountain Laboratory (RML) prions showing signs of scrapie. The inoculum contained ≈107 ID50 units of prions. Mice inoculated intracerebrally (i.c.) received 30 μl of a final 1% homogenate of RML- or Me7-infected mouse brain (≈106 ID50 units).

Determination of Prion Titers.

Prion titers in organ homogenates were determined by an incubation time assay. Tissue from Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 mice (Tg, transgenic; MCK, muscle creatine kinase; SHa, Syrian hamster), which express SHaPrP, were assayed in Syrian hamsters (25, 26). Tissues from Tg(α-actin-MoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0 (Mo, mouse) and Tg(TTR-MoPrP)8332/Prnp0/0 mice (TTR, transthyretin), which express mouse PrP, were assayed in Tg(MoPrP)4053/FVB mice, a Tg line that overexpresses mouse Prnpa (27). The relationship between incubation time and prion titer for Tg(MoPrP)4053/FVB, using the RML prion strain, is log titer (ID50 units/g) = 1 + 32.189⋅e(−0.0278⋅(mean inc. time (days)) (23). Incubation time assays are less accurate at estimating low prion titers than high titers. The convention applied in this article was to estimate titers to be less than 103 ID50 units/g if some, but not all, inoculated animals became ill, and titers to be less than 102 ID50 units/g if no animals became ill. An alternative estimate of low titers can be obtained by assuming that because (0.5t)N is the chance that no inoculated animals develop disease (in which N is the number of animals inoculated and t is ID50 unit titer per inoculum), the maximum titer that has at least a 5% chance of zero transmissions is 0.43 units per inoculum, or about 103.2 ID50 units/g tissue, which is therefore the lower limit of the sensitivity of the assay. In some bioassays of Sc237 prions, all i.c. inoculated hamsters developed disease, but prion titers calculated from equations describing standard curves of mean incubation time vs. the titer resulted in estimated values significantly lower than 1 ID50 unit per inoculation. In these cases, prion titers were reported as calculated to allow comparison with other experiments. Actual titers were likely to be significantly higher, because if all animals developed disease, the titer should be greater than the minimum necessary to result in at least a 5% chance that all inoculated animals would become ill. This value is 1.7 ID50 units per inoculum, or about 103.5 ID50 units/g of tissue, when 8 animals are inoculated with 50 μl of a 1% homogenate, because the likelihood of all animals developing disease is (1 − 0.5t)N.

Transgene Constructs

MCK-SHaPrP.

A 3.3-kbp fragment of the promoter/enhancer region of the mouse MCK gene directs chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) expression to skeletal muscle and myocardium (28). We replaced the β-galactosidase coding sequence in pNASS-beta (CLONTECH) with the coding sequence for full-length SHaPrP and ligated the MCK promoter/enhancer into the XhoI site of the vector. In the completed construct, SV40 splice donor and acceptor sites are situated between the MCK promoter and the SHa ORF. This “artificial intron” may increase expression of the transgene (29).

α-Actin-MoPrP.

A fragment of the chicken α-actin gene, extending from position −191 to position +27 relative to the transcriptional start site, directs expression of a chloramphenicol acetyl transferase gene to skeletal muscle (30). We ligated this 218-bp fragment to a derivative of the mouse PrP gene in which the promoter/enhancer elements and the 12-kbp second intron had been deleted (31).

TTR-MoPrP.

An approximately 300-bp sequence containing the promoter and an enhancer sequence from the mouse TTR gene was linked to the same modified fragment of the mouse PrP gene used in the α-actin-MoPrP construct described above. The TTR promoter/enhancer sequence used had been demonstrated to direct expression to the liver and brain, with occasional expression in the kidney (32).

Microinjections and Screening.

The transgene constructs were introduced into FVB/Prnp0/0 mice. Incorporation of the α-actin-MoPrP and TTR-MoPrP transgenes was detected by hybridization of tail DNA with a murine PrP-specific probe, whereas the presence of the MCK-SHaPrP transgene was determined by PCR on tail DNA using primers that amplify across the MCK-SHaPrP junction.

Analysis of PrP Expression.

Organ homogenates were prepared in PBS. For skeletal muscle, we homogenized the proximal hindlimb muscles. After determining the protein concentration by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce), indicated amounts of total protein were analyzed by Western blotting according to standard procedures (33) with a chemiluminescent detection system (ECL, Amersham Biosciences). Blots were probed with R073, a polyclonal rabbit antiserum that recognizes mouse and hamster PrP (34); HuM-D13, a recombinant Ab recognizing mouse PrP (24); 3F4, a mAb that recognizes hamster but not mouse PrP (35); or HuM-P, a recombinant Ab that recognizes bovine PrP (J. Safar, personal communication). We determined PrP expression levels by visual inspection of serial dilutions of the appropriate homogenates on Western blots.

Results

Substantial Prion Titers in Muscle.

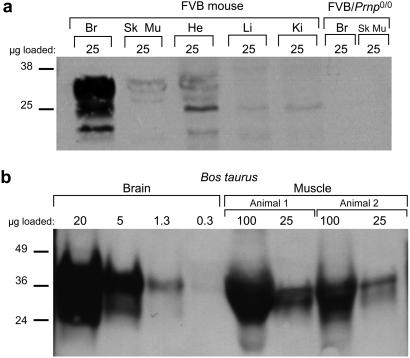

Because PrPC expression is essential for prion propagation, we first used Western blot analysis to confirm that in both mice and cattle (Bos taurus), PrPC is expressed in skeletal muscle, at a level about 5–10% of that in brain (Fig. 1; refs. 36 and 37). We then used an incubation time assay to determine the prion titers in the hindlimb muscle of FVB mice showing signs of disease. Muscle harvested from mice killed 128 days after i.c. inoculation with RML prions harbored titers of 105-106 ID50 units/g (Table 1). These surprisingly high titers of prions in muscle do not represent a general contamination of mouse organs with brain-derived prions because homogenates of liver, an organ that in wild-type (wt) mice expresses almost no PrPC (38), from these same mice either failed to transmit scrapie or transmitted to only a few mice, indicating titers of 103 ID50 units/g or less. Previous studies demonstrated that brain prion titers in mice exhibiting signs of prion infection are typically 109-1010 ID50 units/g (23) when assayed in Tg(MoPrP)4053/FVB mice.

Figure 1.

PrPC expression in mammalian muscle. (a) Western blot depicting the level of PrPC expression in various tissues of an FVB mouse. The highest level of PrPC is in brain (Br), but distinct bands corresponding to fully glycosylated PrPC are also seen in lanes with skeletal muscle (Sk Mu) and heart (He) homogenates. Faint bands apparently representing partially glycosylated PrPC are found in lanes bearing liver (Li) and kidney (Ki) homogenates. No bands are seen in tissues from an FVB/Prnp0/0 mouse. The blot was probed with the R073 polyclonal antiserum. (b) Western blots comparing PrPC expression level in the brain and muscle of Bos taurus. Serial dilutions of brain homogenate from a single animal were compared with dilutions of muscle homogenates from two animals obtained from a different source. The amount of PrPC found in 25 μg of muscle homogenate is slightly greater than that seen in 1.3 μg of brain homogenate; therefore, we conclude that PrPC expression in muscle is ≈5–10% of that in brain. The PrPC derived from muscle in this blot migrated faster than that derived from brain because the muscle is from cattle bearing a 5-octarepeat PRNP allele, whereas brain is derived from an animal with the 6-octarepeat allele (50).

Table 1.

Prion titers in tissues of wt FVB mice

| Tissue assayed | Animal no. | Mean incubation time [days ± SEM (n/n0)]* | Log titer (ID50 units/g† ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle | G70155 | 66 ± 1.7 (10/10) | 6.1 ± 0.2 |

| G70158 | 70 ± 2.4 (10/10) | 5.6 ± 0.3 | |

| G70155 | 64 ± 2.5 (10/10) | 6.4 ± 0.3 | |

| G70157 | 73 ± 2.1 (10/10) | 5.2 ± 0.3 | |

| Liver | G70155 | 103 (2/10) | <3 |

| G70157 | — (0/10) | <2 |

Mice were killed when showing signs of neurologic illness, 128 days after intracerebral inoculation with RML prions.

n, no. of animals diagnosed ill with scrapie; n0, no. of animals inoculated.

Determined by incubation time assay in Tg(MoPrP)4053/FVB mice.

PrPSc Differentially Accumulates in Specific Muscle Groups.

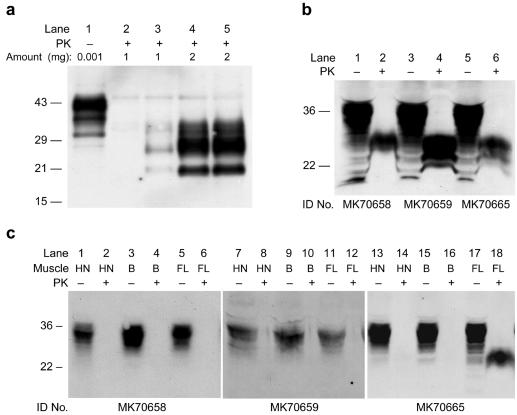

To confirm the high titers of infectious prions we found in skeletal muscle, we used Western immunoblots to detect the presence of protease-resistant PrPSc. We initially examined the hindlimb muscle of wt CD-1 mice showing signs of neurologic disease 128 days after i.c. inoculation with RML prions (Fig. 2a). Muscle homogenates from these mice, but not from uninoculated controls, displayed PK-resistant PrPSc of an apparent molecular weight and glycoform ratio identical to that of PrPSc found in the brain. Comparison of muscle and serial dilutions of brain homogenates on Western blots demonstrated that PK-resistant PrPSc in muscle was ≈500-fold lower than in the brain (data not shown). This brain/muscle PrPSc ratio of 102.7 is similar to the brain/muscle prion titer ratio of approximately 103.

Figure 2.

Protease-resistant PrPSc in muscle of RML- and Me7-infected CD-1 and FVB mice. (a) Lane 1 contains untreated brain homogenate from an uninoculated CD-1 mouse. All other lanes contain insoluble fractions from PK-digested homogenates of CD-1 mouse muscle. No protease-resistant PrPSc was found in the muscle of uninoculated mice (lane 2), whereas PrPSc was readily detectable in the muscle of mice showing signs of neurologic disease 132 days after intracerebral inoculation with RML prions (lanes 4 and 5). For comparison, brain homogenate from a mouse showing signs of disease was diluted 1:1000 into a muscle homogenate from an uninoculated mouse (lane 3). Amounts loaded are expressed as equivalents of total protein (in mg) of homogenate, before proteinase digestion and precipitation. Note that lanes 4 and 5 were loaded with the product of twice as much original homogenate as lanes 2 and 3. (b) Hindlimb skeletal muscles of three ill FVB mice inoculated with Me7 prions were homogenized and subjected to analysis. These mice showed typical clinical signs of disease at 138 days (MK70665) and 146 days (MK70658, MK70659) after intracerebral inoculation with Me7 prions. Samples were digested with PK (lanes 2, 4, and 6) or undigested (lanes 1, 3, and 5). Two milligrams of PK-digested muscle homogenates and about 60 μg of undigested muscle homogenates were used for analysis. (c) Muscle tissue from the head-neck (HN), back (B), and forelimb (FL) of the mice analyzed in b were collected at the time that the hindlimb muscle was collected. Lanes were loaded with PK-digested (even-numbered lanes) and undigested muscle homogenates (odd-numbered lanes). The analytical method was the same as that described in b. All blots were probed with the HuM-D13 Ab.

We next examined the distribution of PrPSc in various muscle groups. For these studies, we used mice showing signs of disease at 138 or 146 days after i.c. inoculation with the Me7 strain of murine prions. Again, we observed substantial PK-resistant PrPSc accumulation in the hindlimb muscle (Fig. 2b). In contrast, we did not detect PrPSc accumulation in the skeletal muscle from other regions, including head and neck, back, or forelimb, with an exception of the forelimb muscle from a single mouse (Fig. 2c). To confirm the region-specific PrPSc accumulation shown in the Western blot analysis, we measured the levels of PrPSc by using ELISA, which gives more quantitative results than Western blotting (Table 2). Only muscle from the hindlimbs of infected mice, and the forelimb muscle of the one mouse described above, had values significantly above background.

Table 2.

Differential protease-resistant PrPSc accumulation in various regions of muscle tissue from mice inoculated i.c. with Me7 prions

| Animal ID | OD405 Mean ± SD†

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head/neck | Back | Forelimb | Hindlimb | |

| Uninoculated control 1 | 0.038 ± 0.015 | 0.091 ± 0.017 | 0.038 ± 0.008 | 0.036 ± 0.007 |

| Uninoculated control 2 | 0.057 ± 0.002 | 0.040 ± 0.006 | 0.059 ± 0.006 | 0.049 ± 0.001 |

| MK70658 | 0.032 ± 0.005 | 0.026 | 0.110 ± 0.063 | 0.414 ± 0.006 |

| MK70659 | 0.043 ± 0.004 | 0.095 | 0.124 | 0.492 ± 0.023 |

| MK70665 | 0.047 ± 0.001 | 0.055 ± 0.011 | 0.498 ± 0.059 | 0.499 ± 0.029 |

| P value* | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.02 | <0.000001 |

P values were calculated by comparing all muscle of uninoculated mice to muscle of the indicated region from all inoculated mice, using the t test with an alpha of 0.0125 to correct for multiple comparisons.

Mean and SD were obtained from duplicates or triplicates of ELISA. Nos. without SD were obtained from single ELISA determinations.

Intrinsic Prion Replication in Muscle.

Muscle tissue is composed of a variety of cell types (39) and is intimately associated with neural tissue. To determine whether prions replicate in myofibers, we constructed two lines of Tg mice that express PrP only under the control of myocyte-specific promoters. For each line, we introduced transgenes into FVB mice in which the chromosomal PrP gene had been disrupted (Prnp0/0) (refs. 27 and 40). In the first line, designated Tg(α-actin-MoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0, the chicken α-actin promoter directs expression of the mouse Prnpa allele. In the second line, designated Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0, the MCK promoter drives the expression of SHaPrP.

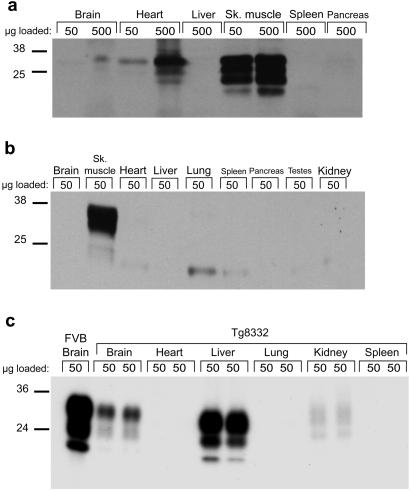

Skeletal muscle from Tg(α-actin-MoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0 mice (Fig. 3a) expresses PrPC at a level that is about 8-fold higher than the level found in the brains of wt mice. Low levels of PrPC are produced in cardiac muscle and PrPC is barely detectable in brain. In the Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 line, the level of PrPC expression in muscle is 4-fold higher than the level of PrPC that is expressed in hamster brain. Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 mice express low levels of PrPC in cardiac muscle, and no PrPC was detected in the brain (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Western blots depicting the distribution of PrPC expression in Tg mice. (a) Tg(α-actin-MoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0 mouse probed with the polyclonal Ab R073. PrPC expression in muscle is about 8-fold higher than in wt mouse brain (not shown). (b) Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 mouse probed with 3F4, a mAb that recognizes hamster PrPC. PrPC expression is detectable only in skeletal muscle (Sk. muscle). A longer exposure of this blot (not shown) revealed trace expression in cardiac muscle, but no PrPC was detected in any other organ. The low molecular weight bands, seen most prominently in lane 5 (Lung), were also seen when the anti-mouse Ig secondary Ab was used without prior incubation with 3F4. (c) Homogenates of organs from two Tg(TTR-MoPrP) 8332/Prnp0/0 mice compared with FVB brain. The blot was probed with R073. PrPC expression in liver is lower than in FVB brain but higher than in the brain of mice of this Tg line. A very small amount of PrPC is expressed in the kidney. Glycosylated forms of PrPC from the liver migrate slightly faster than the corresponding glycoforms from the brain of these same mice or of FVB mice.

We inoculated the Tg mice and non-Tg littermates i.m. in the left hindlimb with prions and then killed the mice at various times after inoculation. Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 mice were inoculated with hamster Sc237 prions. We inoculated Tg(α-actinMoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0 mice with RML prions and in parallel, inoculated FVB/Prnp0/0 mice, which are incapable of propagating prions (2, 3), with the same prion strain. We used incubation time assays to determine prion titers in homogenates of muscle from the hindlimb contralateral to the inoculated one, the brain, and the spleen.

From Tg(α-actin-MoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0 mice inoculated with RML prions, we found titers of >107 ID50 units/g in muscle, obtained at 350 days after inoculation. Titers were generally lower in muscles of Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 mice inoculated with Sc237 prions, at ≈104 ID50 units/g in two mice and ≈108 ID50 units/g in another mouse, all three of which were killed 413 days after inoculation (Table 3). The muscle prion titer in a fourth mouse killed 76 days after inoculation was ≈104 ID50 units/g. We did not detect prions in muscle homogenates from uninoculated Tg(α-actin-MoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0 and Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 mice.

Table 3.

Prion titers in tissues of Tg mice

| Line | Inoculum (route) | Interval* | Tissue assayed | Animal no. | Mean incubation time [days ± SEM (n/n0)‡] | Log titer (ID50 units/g§ ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 | Sc237 (i.m.) | 413 | Muscle† | E4041 | 82 ± 1.3 (8/8) | 7.4 ± 0.1 |

| 413 | E4516 | 112 ± 0.7 (8/8) | 4.2 ± 0.1 | |||

| 413 | E4509 | 114 ± 6.2 (8/8) | 4.0 ± 0.4 | |||

| 76 | E4515 | 113 ± 2.4 (8.8) | 4.2 ± 0.1 | |||

| 413 | Brain | E4509 | — (0/8) | <2 | ||

| 76 | Spleen | E4515 | 211 (5/8) | <3 | ||

| 413 | E4516 | 220 (3/8) | <3 | |||

| None | NA | Muscle | D16745 | — (0/8) | <2 | |

| D16746 | — (0/8) | <2 | ||||

| Tg(α-actin-MoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0 | RML (i.m.) | 350 | Muscle | E9812 | 58 ± 2 (10/10) | 7.4 ± 0.4 |

| 350 | E9813 | 59 ± 2 (10/10) | 7.2 ± 0.4 | |||

| 350 | Brain | E9812 | 105 (2/10) | <3 | ||

| 350 | E9813 | 126 (4/10) | <3 | |||

| 350 | Spleen | E9812 | 424 (3/5) | <3 | ||

| 350 | E9813 | 201 (6/7) | <3 | |||

| FVB/Prnp0/0 | RML (i.m.) | 350 | Muscle | E8979 | — (0/10) | <2 |

| 350 | E8980 | — (0/10) | <2 | |||

| Tg(TTR-MoPrP)8332/Prnp0/0 | RML (i.p.) | 523 | Liver | E10176 | 197 (3/10) | <3 |

| 523 | E10177 | 93 ± 3.2 (10/10) | 3.4 ± 0.2 | |||

| RML (i.c.) | 296 | Liver | MF4691 | 91 ± 2.9 (10/10) | 3.8 ± 0.2 | |

| 296 | MF4692 | 97 (7/8) | <3 | |||

| 296 | Brain | MF4691 | 51 ± 2.5 (10/10) | 8.8 ± 0.6 | ||

| 296 | MF4692 | 55 ± 2.1 (10/10) | 8.0 ± 0.5 | |||

| None | NA | Liver | ME9012 | — (0/10) | <2 |

No. of days from inoculation to time of death of animal. NA, not applicable.

Muscle tissue is from the hindlimb contralateral to the hindlimb that was injected with the prion inoculum.

n, no. of animals diagnosed ill with scrapie; n0, no. of animals inoculated.

Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 tissue prion titers determined by incubation time assay in Syrian hamsters. All others assayed in Tg(MoPrP)4053/FVB mice.

We performed several experiments to confirm that the prions we found in muscle were formed therein. Results from two experiments exclude residual inoculum as the source of the prions that we measured. First, we detected no prions in the muscle of the FVB/Prnp0/0 mice, which are incapable of propagating prions (2, 3), at 350 days after i.m. inoculation with RML prions, indicating that the prions had been cleared. Second, because it is conceivable that FVB/Prnp0/0 mice clear prions more efficiently than mice expressing PrPC (41), we inoculated both Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 and FVB/Prnp0/0 mice with Sc237 prions, then determined prion titers in the inoculated muscle at various intervals (Table 4). Prions disappeared equally rapidly from both lines. Moreover, the levels of prions found ipsilateral to the injection site at 28 days after inoculation in Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 mice were at least 10-fold lower than the levels found contralateral to the injection site in mice killed at later times, indicating de novo prion synthesis (compare Tables 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Decline of prion titers in muscle early after inoculation with Sc237 prions

| Line | Interval between inoculation and harvest | Mean incubation time [days ± SEM (n/n0)*] | Log titer† (ID50 units/g ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 | 4 h | 112.5 ± 3.3 (8/8) | 3.9 ± 0.3 |

| 90 ± 4.3 (8/8) | 6.8 ± 0.5 | ||

| 1 day | 85.8 ± 2.0 (8/8) | 6.2 ± 0.2 | |

| 92.5 ± 1.3 (8/8) | 5.3 ± 0.2 | ||

| 7 days | 118 ± 2.3 (8/8) | 3.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 114.4 ± 4.9 (8/8) | 4.8 ± 0.4 | ||

| 28 days | 184.5 ± 4.6 (8/8) | −0.6 ± 0.3 | |

| — (0/8) | — | ||

| FVB/Prnp0/0 | 4 h | 87.4 ± 1.0 (8/8) | 6.0 ± 0.1 |

| 115.8 ± 1.3 (8/8) | 3.0 ± 0.1 | ||

| 1 day | 109.6 ± 2.7 (8/8) | 3.5 ± 0.2 | |

| 101.9 ± 1.5 (8/8) | 4.2 ± 0.2 | ||

| 7 days | 114 ± 3.0 (8/8) | 3.2 ± 0.2 | |

| 182.1 ± 8.1 (8/8) | 0.5 ± 0.5 | ||

| 28 days | 174.3 ± 5.7 (8/8) | 0.4 ± 0.4 | |

| 200.3 ± 9.7 (4/8) | — |

n, no. of animals diagnosed ill with scrapie; n0, no. of animals inoculated.

Determined by incubation time assay in i.c. inoculated hamsters. In some cases, very long incubation periods result in low calculated titers, which are likely to be underestimations (see Materials and Methods). These values are reported for purposes of comparison.

To exclude the possibility that the prions found in muscle were contaminants produced elsewhere in our mice, we determined prion titers in the brains and spleens of Tg mice inoculated i.m. No prions were detected in Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 mouse brain, but low titers were found in Tg(α-actin-MoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0 brain, a finding consistent with the low level of PrPC produced there. We also found low prion titers in the spleens of inoculated mice from both lines, which might represent an accumulation of prions formed elsewhere, because Western blot analysis failed to detect splenic PrPC in these lines. The titers in spleen and brain were, in all cases, lower than in muscle; therefore, the titers in muscle were unlikely to be the results of contamination from other tissues.

Tg(α-actin-MoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0 and Tg(MCK-SHaPrP)8775/Prnp0/0 mice spontaneously developed a myopathy, in accordance with findings in mice, in which PrPC is overexpressed under control of the SHaPrP promoter (42). We detected similar histologic abnormalities in the muscle of prion-inoculated mice and uninoculated Tg controls (data not shown).

Hepatocytes Inefficiently Accumulate Prions.

To determine whether prions can propagate in hepatocytes, we used Tg(TTR-MoPrP)8332/Prnp0/0 mice, in which a fragment of the TTR promoter directs mouse Prnpa expression simultaneously to the liver and to a subset of brain neurons (Fig. 3c), with higher PrP levels in liver than in brain. We inoculated the mice i.c. with RML prions and killed them when they developed signs of disease at 296 days. To test the influence of inoculation site, we also inoculated Tg(TTR-MoPrP)8332/Prnp0/0 mice i.p. with RML prions.

Prion titers in the brains of Tg(TTR-MoPrP)8332/Prnp0/0 mice inoculated i.c. with RML prions were 108–109 ID50 units/g, whereas hepatic prion titers were only ≈103 ID50 units/g. Tg(TTR-MoPrP)8332/Prnp0/0 mice inoculated i.p. with RML prions never appeared ill and were killed 523 days after inoculation. Hepatic prion titers in the mice inoculated i.p. were similar to those of mice inoculated i.c. Although hepatic prion titers were low, it does seem that expressing high levels of PrPC in liver enhances prion formation, because liver homogenates from Tg(TTR-MoPrP)8332/Prnp0/0 mice inoculated with RML prions transmitted disease to significantly more mice than did liver homogenates from RML-inoculated FVB mice (Tables 1 and 3; P < 0.001, Fisher exact test).

From these data, we conclude that different cell types accumulate prions with markedly different efficiencies, even when PrPC expression levels are similar. Comparing three tissues in Tg mice expressing murine PrPC, RML prion titers were ≈109 ID50 units/g in brain, ≈103 ID50 units/g in liver [for Tg(TTR-MoPrP)8332/Prnp0/0 mice], and 107 ID50 units/g in hindlimb skeletal muscle [for Tg(α-actin-MoPrP)6906/Prnp0/0 mice]. The differing levels of prion accumulation may be due in part to the restricted expression of auxiliary proteins that have been postulated to participate in prion replication (43, 44). The apparently different glycosylation of hepatic PrPC may contribute to the inefficient prion accumulation seen there, but brain and muscle PrPSc displayed different levels of accumulation despite indistinguishable glycoforms. Notable is a study by other investigators (38) who concluded that prions failed to propagate in hepatocytes or T cells of Tg mice that express PrP in these cell types. However, the authors stated that the levels of PrP expression achieved in the livers of their mice were quite low and that the absence of detectable prions in circulating T cells might have been caused by loss of prion-infected cells during natural turnover or because of prion-related toxicity.

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate that mouse skeletal muscle is intrinsically capable of propagating prions, that titers at least as high as 107 ID50 units/g can accumulate in muscle, and most surprisingly, that the efficiency of this accumulation varies markedly among groups of muscles taken from different regions of the body. Our finding of prion accumulation in skeletal muscle seems unambiguous, in that we obtained similar results with two different prion strains in wt mice and in Tg mice expressing PrPC almost exclusively in skeletal muscle. Why prions accumulate more efficiently in certain muscles than in others is not clear. However, different skeletal muscle groups demonstrate differential susceptibility to a number of disease processes, a property that presumably reflects biochemical differences in skeletal muscles of different body regions (45).

Studies in Tg mice (46) and cultured cells (43, 44) have implicated a cellular factor other than PrP, provisionally termed “protein X,” that is needed for the efficient propagation of prions. Perhaps only some skeletal muscles have sufficient amounts of protein X to enable the accumulation of high titers of prions. Similarly, the inefficient accumulation of prions in hepatic tissue demonstrated by our studies is further evidence of a role for an auxiliary factor such as protein X in prion propagation.

That high prion titers may be found in skeletal muscle even if central nervous system and lymphatic tissues are carefully excluded from the muscle raises the concern that humans consuming meat from prion-infected animals are at risk for acquiring infection. However, several caveats must be considered when assessing the risk of humans developing disease from prion-tainted meat. First, the efficiency of prion accumulation in muscle may vary with either the host species or the prion strain involved. Indeed, mouse RML prions seem to have accumulated more efficiently in muscle than did hamster Sc237 prions. Second, oral transmission is inefficient compared with the i.c. inoculations used for the bioassays reported in this study. In hamsters, oral exposure is 105- to 109-fold less efficient that the i.c. route (47, 48). Finally, the species barrier must be considered. In many cases, efficient transmission of prions from one species to another requires a high degree of homology in the amino acid sequence of PrP between the two species. However, the degree to which amino acid sequence influences the efficiency of transmission depends on the strain of prion. In the case of new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (nvCJD) prions, Tg mice expressing bovine PrPC are much more susceptible to nvCJD prions, derived from human brain, than are Tg mice expressing either human or chimeric human-mouse PrPC (refs. 10 and 49; C. Korth and S.B.P., unpublished data).

Previous studies have generally reported low prion titers in muscle tissue. Some of these studies used inefficient cross-species transmissions, which might be responsible for their failure to detect prions in muscle (19). Our investigations reveal another potential explanation for this failure. Because muscle prion accumulation varies between muscle groups or perhaps between specific muscles, previous studies may have failed to sample the muscles bearing the highest prion titers. If prions accumulate in certain muscles of humans with prion disease to levels near those that we found in mice with prion disease, it should be possible to definitively diagnose all forms of CJD and related disorders by using muscle tissue for biopsy. This approach would offer significant advantages over the relatively difficult and morbid brain biopsy procedure, which is currently the only way to definitively diagnose prion disease in humans.

Whether prions accumulate in skeletal muscle of cattle with BSE, of sheep with scrapie, or of deer and elk with chronic wasting disease remains to be established. However, our findings indicate that a comprehensive and systematic effort to determine the distribution of prions in the skeletal muscle of animals with prion disease is urgently needed. The distribution of prions in muscle may vary with the animal species, perhaps even with breeds, varieties, and lines within a species as well as with the strain of prions. Such assays need to be carried out by using sensitive and quantitative techniques, such as bioassays in Tg mice and quantitative immunoassays adapted to PrPSc detection in muscle tissue.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hang Nguyen for her skillful editorial assistance and to Julianna Cayetano for performing much of the histological tissue preparation associated with this project. We thank Douglas Hanahan for his useful advice in developing the Tg mice used in this study. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and by a gift from the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Foundation.

Abbreviations

- PrP

prion protein

- PrPC

normal cellular isoform

- PrPSc

disease-causing isoform

- Tg

transgenic

- wt

wild type

- MCK

muscle creatine kinase

- TTR

transthyretin

- BSE

bovine spongiform encephalopathy

- PK

proteinase K

- RML

Rocky Mountain Laboratory

- i.c.

intracerebrally

- SHa

Syrian hamster

- Mo

mouse

References

- 1.Prusiner S B. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Büeler H, Aguzzi A, Sailer A, Greiner R-A, Autenried P, Aguet M, Weissmann C. Cell. 1993;73:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prusiner S B, Groth D, Serban A, Koehler R, Foster D, Torchia M, Burton D, Yang S-L, DeArmond S J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10608–10612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eklund C M, Kennedy R C, Hadlow W J. J Infect Dis. 1967;117:15–22. doi: 10.1093/infdis/117.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hadlow W J, Kennedy R C, Race R E, Eklund C M. Vet Pathol. 1980;17:187–199. doi: 10.1177/030098588001700207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prusiner S B, Fuzi M, Scott M, Serban D, Serban H, Taraboulos A, Gabriel J-M, Wells G, Wilesmith J, Bradley R, et al. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:602–613. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carp R I. Lancet. 1982;1:170–171. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips N A, Bridgeman J, Ferguson-Smith M. The BSE Inquiry. Vol. 2. London: Stationery Office; 2000. pp. 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott M, Foster D, Mirenda C, Serban D, Coufal F, Wälchli M, Torchia M, Groth D, Carlson G, DeArmond S J, et al. Cell. 1989;59:847–857. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90608-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott M R, Will R, Ironside J, Nguyen H-O B, Tremblay P, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15137–15142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Will R G, Cousens S N, Farrington C P, Smith P G, Knight R S G, Ironside J W. Lancet. 1999;353:979. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alpers M P. In: The Central Nervous System: Some Experimental Models of Neurological Diseases. Bailey O T, Smith D E, editors. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1968. pp. 234–251. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gajdusek D C. Science. 1977;197:943–960. doi: 10.1126/science.142303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spraker T R, Miller M W, Williams E S, Getzy D M, Adrian W J, Schoonveld G G, Spowart R A, O'Rourke K I, Miller J M, Merz P A. J Wildl Dis. 1997;33:1–6. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-33.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belay E D, Gambetti P, Schonberger L B, Parchi P, Lyon D R, Capellari S, McQuiston J H, Bradley K, Dowdle G, Crutcher J M, Nichols C R. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1673–1678. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pattison I H, Millison G C. J Comp Path Ther. 1962;72:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0368-1742(62)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh R F, Burger D, Hanson R P. Am J Vet Res. 1969;30:1637–1642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser H, Bruce M E, Chree A, McConnell I, Wells G A H. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1891–1897. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells G A H, Hawkins S A C, Green R B, Austin A R, Dexter I, Spencer Y I, Chaplin M J, Stack M J, Dawson M. Vet Rec. 1998;142:103–106. doi: 10.1136/vr.142.5.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubo M, Kimura K, Yokoyama T, Kobayashi M. Bull Natl Inst Anim Health. 1995;101:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips N A, Bridgeman J, Ferguson-Smith M. The BSE Inquiry. Vol. 4. London: Stationery Office; 2000. p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Safar J, Wille H, Itri V, Groth D, Serban H, Torchia M, Cohen F E, Prusiner S B. Nat Med. 1998;4:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Supattapone S, Wille H, Uyechi L, Safar J, Tremblay P, Szoka F C, Cohen F E, Prusiner S B, Scott M R. J Virol. 2001;75:3453–3461. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3453-3461.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peretz D, Scott M, Groth D, Williamson A, Burton D, Cohen F E, Prusiner S B. Protein Sci. 2001;10:854–863. doi: 10.1110/ps.39201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prusiner S B, Cochran S P, Groth D F, Downey D E, Bowman K A, Martinez H M. Ann Neurol. 1982;11:353–358. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prusiner S B, Kaneko K, Cohen F E, Safar J, Riesner D. In: Prion Biology and Diseases. Prusiner S B, editor. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1999. pp. 653–715. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Telling G C, Haga T, Torchia M, Tremblay P, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1736–1750. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.14.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson J E, Wold B J, Hauschka S D. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3393–3399. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi T, Huang M, Gorman C, Jaenisch R. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3070–3074. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petropoulos C J, Rosenberg M P, Jenkins N A, Copeland N G, Hughes S H. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3785–3792. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer M, Rülicke T, Raeber A, Sailer A, Moser M, Oesch B, Brandner S, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. EMBO J. 1996;15:1255–1264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costa R H, Lai E, Grayson D R, Darnell J E., Jr Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:81–90. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning–A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serban D, Taraboulos A, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Neurology. 1990;40:110–117. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kascsak R J, Rubenstein R, Merz P A, Tonna-DeMasi M, Fersko R, Carp R I, Wisniewski H M, Diringer H. J Virol. 1987;61:3688–3693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3688-3693.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horiuchi M, Yamazaki N, Ikeda T, Ishiguro N, Shinagawa M. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2583–2587. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-10-2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bendheim P E, Brown H R, Rudelli R D, Scala L J, Goller N L, Wen G Y, Kascsak R J, Cashman N R, Bolton D C. Neurology. 1992;42:149–156. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raeber A J, Sailer A, Hegyi I, Klein M A, Rulike T, Fischer M, Brandner S, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3987–3992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engel A, Banker B Q. Myology: Basic and Clinical. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Büeler H, Fisher M, Lang Y, Bluethmann H, Lipp H-P, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B, Aguet M, Weissmann C. Nature (London) 1992;356:577–582. doi: 10.1038/356577a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Race R, Chesebro B. Nature (London) 1998;392:770. doi: 10.1038/33834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westaway D, DeArmond S J, Cayetano-Canlas J, Groth D, Foster D, Yang S-L, Torchia M, Carlson G A, Prusiner S B. Cell. 1994;76:117–129. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaneko K, Zulianello L, Scott M, Cooper C M, Wallace A C, James T L, Cohen F E, Prusiner S B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10069–10074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zulianello L, Kaneko K, Scott M, Erpel S, Han D, Cohen F E, Prusiner S B. J Virol. 2000;74:4351–4360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4351-4360.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams R D, Victor M, Ropper A H. Principles of Neurology. New York: McGraw–Hill Health Professions Division; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Telling G C, Scott M, Mastrianni J, Gabizon R, Torchia M, Cohen F E, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Cell. 1995;83:79–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prusiner S B, Cochran S P, Alpers M P. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:971–978. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diringer H, Roehmel J, Beekes M. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:609–612. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-3-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hill A F, Desbruslais M, Joiner S, Sidle K C L, Gowland I, Collinge J, Doey L J, Lantos P. Nature (London) 1997;389:448–450. doi: 10.1038/38925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldmann W, Hunter N, Martin T, Dawson M, Hope J. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:201–204. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-1-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]