Abstract

Background

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a highly aggressive malignancy predominantly treated with chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. The role of surgical intervention in SCLC, however, remains inadequately defined. This study aimed to retrospectively analyze the clinical data of patients with SCLC who underwent surgical treatment to assess the impact of surgery combined with perioperative adjuvant therapy on long-term prognosis, with the goal of informing future treatment strategies.

Methods

This study included patients with SCLC who underwent surgical treatment at West China Hospital, Sichuan University, between 2005 and 2021. Prognostic factors influencing overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were analyzed using univariate and multivariate Cox regression models, in conjunction with the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

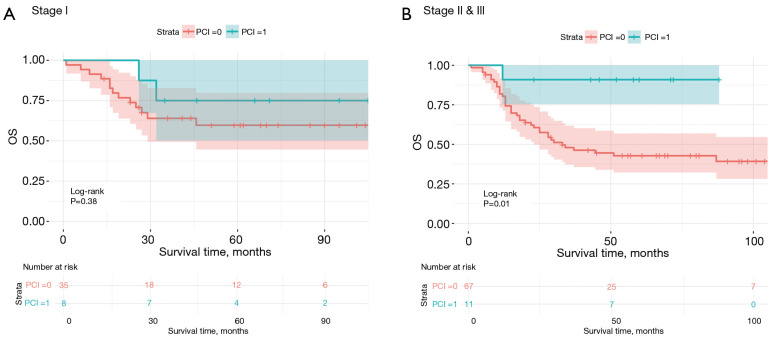

A cohort of 121 patients with SCLC who underwent surgical treatment was included. Multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy [hazard ratio (HR) =0.45; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.24–0.85] was significantly associated with improved OS, whereas a smoking index exceeding 400 (HR =1.0011; 95% CI: 1.0004–1.0018) was identified as an independent adverse prognostic factor. Pathological stratification showed that prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) was significantly associated with improved OS in stage II/III patients (P<0.05) but had not in stage I patients (P>0.05). Regarding DFS, preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy was associated with significantly prolonged DFS (HR =0.44; 95% CI: 0.21–0.94), while lymph node metastasis was identified as a negative predictor (HR =1.97; 95% CI: 1.16–3.36).

Conclusions

Surgical intervention combined with perioperative adjuvant therapy provides significant survival benefits for patients with SCLC. Notably, preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy were associated with prolonged DFS and OS. For early-stage patients, the application of PCI should be approached cautiously. Further prospective studies are warranted to better balance its potential risks and benefits.

Keywords: Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), surgical intervention, perioperative adjuvant therapy, overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS)

Highlight box.

Key findings

• Surgical intervention combined with perioperative adjuvant therapy was significantly associated with improved long-term survival in patients with small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) may benefit stage II/III patients but has no effect in patients with stage I disease. A high smoking index was associated with worse overall survival, and lymph node metastasis was associated with worse disease-free survival.

What is known and what is new?

• SCLC is typically treated with chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. The role of surgery in SCLC remains controversial.

• The findings of this study indicate a survival benefit of combining surgery with perioperative therapies and support the selective use of PCI in stage-specific contexts.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Surgery should be considered for early-stage SCLC with appropriate adjuvant therapies.

• PCI should be selectively applied based on stage.

• Smoking cessation should be prioritized in SCLC management.

Introduction

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) was first described by Barnard in 1926 and was initially referred to as “a peculiar medullary tumor with oat-shaped cells” (1). Currently, SCLC accounts for approximately 13–15% of all lung cancer cases (2,3). Despite its relatively low incidence, SCLC remains one of the most lethal malignancies. SCLC can be classified into limited-stage SCLC (LS-SCLC) and extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC). Notably, approximately 80% of patients are diagnosed with ES-SCLC at the time of initial presentation and have a poor prognosis (2). The median overall survival (OS) is only 7–10 months, the 2-year OS rate is 10–20%, and the 5-year OS rate is less than 7% (2,3). Due to the aggressive nature of SCLC, characterized by rapid growth, early and widespread metastasis, and frequent involvement of the liver and brain, standard treatment strategies primarily rely on chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. This reliance may contribute to the efficacy of surgical interventions being underestimated.

Some studies suggest that surgical treatment may improve OS in patients with LS-SCLC (4,5). Roof et al., through an analysis of data from the US National Cancer Database (NCDB) from 2004 to 2016, evaluated various prognostic factors for SCLC and identified surgery as a significant factor in prolonging OS (4). Schreiber et al. further reviewed treatment data from 1988 to 2002 for patients with stages T1–2 Nx–N0 and T3–4 Nx–N0 LS-SCLC, analyzing a cohort of 14,179 patients, of whom 863 underwent surgical treatment (5). Kaplan-Meier and Cox model analyses revealed that surgery had a significant impact on long-term survival among patients with SCLC: for T1–2 Nx–N0 patients, the median OS for those undergoing surgery was significantly extended from 15 months (compared to nonsurgical patients) to 42 months (P<0.001). Similarly, for T3–4 Nx–N0 patients, the median OS increased from 12 months (compared to nonsurgical patients) to 22 months (P<0.001) (5). Additionally, studies have reported that for patients with stage II and IIIa SCLC, the combination of surgery and chemotherapy can achieve outcomes comparable to surgical treatment of non-SCLC at corresponding stages (6,7). However, despite the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommending surgery for early-stage SCLC, the level of evidence supporting this recommendation remains low, and the efficacy of surgical treatment remains a subject of ongoing debate (8).

The research on surgical treatment for SCLC faces several limitations, particularly a lack of comprehensive evaluations of perioperative adjuvant therapies. The majority of related studies have focused on chemoradiotherapy for nonsurgical patients. Some evidence suggests that postoperative chemotherapy may improve OS (5,6,9). However, postoperative radiotherapy appears to have no significant impact on disease-free survival (DFS) or OS and may even be harmful (10). Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) is associated with significant neurotoxicity and cognitive side effects, leading to controversy regarding its use in patients with LS-SCLC (11). Although some studies support the application of PCI for stage II/III SCLC, its use for stage I disease is not recommended. Research on preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy is sparse, with two studies indicating the potential benefits of this approach (12,13).

In this context, this study retrospectively analyzed data from patients with SCLC who underwent surgical treatment at West China Hospital, Sichuan University, aiming to identify key factors associated with the survival of surgical patients and to evaluate the potential benefits of perioperative adjuvant therapy in improving patient prognosis. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2025-490/rc).

Methods

Patient cohort

This study involved a retrospective analysis based on a cohort of patients with long-term follow-up and was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (No. 20232450). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The requirement for individual consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the analysis. All patients included in the study were diagnosed with SCLC at West China Hospital, Sichuan University, between January 2005 and November 2021. Staging of SCLC was determined according to the 8th edition of the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification system.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients with primary, nonmetastatic SCLC who underwent surgical treatment. Preoperative staging was performed routinely through contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Additionally, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET), bone scans, and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial-needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) were selectively employed based on clinical indications and the physician’s judgment. The decision for surgery was made after comprehensive assessment of the patient’s clinical status and staging, in line with the institutional guidelines.

Regarding the surgical procedure, neoadjuvant chemotherapy with the EP regimen (etoposide and cisplatin combination) was administered to a subset of patients for 2 to 4 cycles, with etoposide doses ranging from 100 to 110 mg/m2 days 1, 2, 3 and cisplatin doses ranging from 40 to 60 mg/m2 day 1. Except for two patients who underwent pneumonectomy, all other patients underwent lobectomy. Lymph node dissection was performed during surgery, with the dissection range including ipsilateral hilar lymph nodes (N1), ipsilateral mediastinal lymph nodes (N2), and intrapulmonary lymph nodes. The number of lymph nodes dissected ranged from a minimum of 6 to a maximum of 28, depending on the pathological findings. Notably, some patients underwent surgery in the earlier years of the study period, when the indications for surgical treatment of SCLC—particularly for lymph node positivity (N+) patients—were still evolving in clinical practice. In addition, the sensitivity of preoperative imaging in detecting lymph node metastasis was limited at the time. Therefore, many N+ cases in this study were identified only through postoperative pathological examination rather than being confirmed preoperatively.

For patients who received postoperative chemotherapy, the treatment regimen primarily included the EP regimen (etoposide and cisplatin combination). The cycles typically ranged from 2 to 6 cycles, with etoposide doses ranging from 100 to 120 mg/m2 days 1, 2, 3 and cisplatin doses ranging from 40 to 60 mg/m2 day 1. A small subset of patients received alternative combinations, such as carboplatin with etoposide, etoposide with nedaplatin, or etoposide with carboplatin, based on individual clinical considerations. In addition, PCI was administered to selected patients with limited-stage disease and no evidence of brain metastasis, particularly those with higher pathological stage or lymph node involvement. The PCI dose was 25 to 30 Gy delivered in 10 to 15 fractions.

Brain imaging during follow-up was routinely conducted using non-contrast or contrast-enhanced CT of the head to monitor for intracranial metastasis. In addition, CT of the chest and abdomen was routinely performed to assess for thoracic or abdominal recurrence or metastasis.

The baseline clinical characteristics collected included age at diagnosis, gender, chief complaint, general physical condition, family history of cancer, surgical history, smoking history, tumor size, use of thoracoscopic surgery, postoperative admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), postoperative complications, R0 resection status, presence of vascular invasion in pathology, extent of lymph node involvement, histological grade, and whether adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy and PCI were administered. Additionally, data on recurrence and metastasis during follow-up were recorded.

Patients lacking detailed survival or treatment information were excluded from the analysis. OS was defined as the duration from the date of surgery to death or the date of the last follow-up. DFS was defined as the time from the date of surgery to the first documented recurrence, metastasis, or the last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Missing data are an inherent issue in retrospective studies. To understand the distribution of missing values, we first visualized them using a missing data intersection plot, shown in Figure S1. After identifying the missing data patterns, we applied the MissForest imputation method to handle the missing values. MissForest is a random forest-based algorithm that iteratively predicts and imputes missing values for both numerical and categorical variables, ensuring the statistical properties of the dataset are preserved.

Univariate Cox regression analysis was performed to evaluate each variable, with hazard ratios (HRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P values being extracted. For categorical variables, the model provided a detailed stratified analysis for different categories. Variables with P<0.05 in the univariate Cox regression were further analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method to construct survival curves and compare survival differences between groups. Based on the results of the univariate analysis, significant variables (P<0.05) were selected to construct a multivariate Cox regression model. This model was used to further extract HRs, 95% CIs, and P values to enable evaluation of the combined effects of multiple variables on OS and DFS.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 4.4.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with statistical significance set at a two-sided P value <0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 121 patients with SCLC were included in this study, with a mean age of 57.41 years (range, 35 to 81 years). Among them, 78.5% were male (95 patients), and 21.5% were female (26 patients). At diagnosis, 62.0% of patients were symptomatic while 38.0% were asymptomatic. A total of 49.6% of patients had comorbidities, 38.0% had a history of surgery, and 19.0% reported a family history of cancer. Smoking history was noted in 68.6% of patients, with a median smoking index of 400 (range, 0 to 1,800). Among these patients, 50.4% had smoking cessation, 18.2% continued smoking, and 31.4% were nonsmokers. The median tumor size was 2.9 cm (range, 0.5 to 7 cm). Regarding treatment history, 24.8% of patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and 57.0% underwent thoracoscopic surgery. Postoperative complications occurred in 30.6% of patients, and R0 resection was achieved in 96.7% of cases. Vascular tumor thrombus was identified in 9.9% of patients. Pathological TNM staging showed that 35.5% of patients were in stage I, 33.9% in stage II, and 30.6% in stage III, for which the detailed T and N staging is provided in Table S1. N+ was observed in 38.8% of patients. In terms of adjuvant therapy, 76.0% of patients received postoperative chemotherapy, 18.2% postoperative radiotherapy, and 15.7% PCI. During the follow-up period, 49.6% of patients experienced recurrence or metastasis (Table 1). The median follow-up duration was 22 months [range, 1–200 months; interquartile range (IQR), 7–61 months], with 25% of patients followed for more than 5 years.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical features of patients.

| Variables | Data (n=121) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean [range] | 57.41 [35, 81] |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 26 (21.5) |

| Male | 95 (78.5) |

| Symptoms at presentation, n (%) | |

| Yes | 75 (62.0) |

| No | 46 (38.0) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Yes | 60 (49.6) |

| No | 61 (50.4) |

| Family history, n (%) | |

| Yes | 23 (19.0) |

| No | 98 (81.0) |

| Surgical history, n (%) | |

| Yes | 46 (38.0) |

| No | 75 (62.0) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |

| Yes | 83 (68.6) |

| No | 38 (31.4) |

| Smoking index, median [range] | 400 [0, 1,800] |

| Smoking cessation, n (%) | |

| Yes | 61 (50.4) |

| No | 22 (18.2) |

| Not involved | 38 (31.4) |

| Tumor size (cm), median [range] | 2.9 [0.5, 7] |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| Yes | 30 (24.8) |

| No | 91 (75.2) |

| Thoracoscopy, n (%) | |

| Yes | 69 (57.0) |

| No | 52 (43.0) |

| ICU, n (%) | |

| Yes | 29 (24.0) |

| No | 92 (76.0) |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | |

| Yes | 37 (30.6) |

| No | 84 (69.4) |

| Surgical margin, n (%) | |

| R0 | 117 (96.7) |

| R1 | 4 (3.3) |

| Vascular cancer thrombus, n (%) | |

| Yes | 12 (9.9) |

| No | 109 (90.1) |

| T, n (%) | |

| T1a | 5 (4.1) |

| T1b | 23 (19.0) |

| T1c | 16 (13.2) |

| T2a | 39 (32.2) |

| T2b | 14 (11.6) |

| T3 | 24 (19.8) |

| N, n (%) | |

| N0 | 74 (61.2) |

| N+ | 47 (38.8) |

| TNM, n (%) | |

| Stage I | 43 (35.5) |

| Stage II | 41 (33.9) |

| Stage III | 37 (30.6) |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| Yes | 92 (76.0) |

| No | 29 (24.0) |

| Postoperative radiotherapy, n (%) | |

| Yes | 22 (18.2) |

| No | 99 (81.8) |

| PCI, n (%) | |

| Yes | 19 (15.7) |

| No | 102 (84.3) |

| Recurrence and metastasis, n (%) | |

| Yes | 60 (49.6) |

| No | 61 (50.4) |

ICU, intensive care unit; N, node; PCI, prophylactic cranial irradiation; T, tumor; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

OS

To investigate the factors affecting OS in patients with SCLC, univariate Cox regression analysis was performed for all variables, with the detailed results presented in Table S2. A total of six variables showed statistical significance in the analysis. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (HR =0.36; 95% CI: 0.21–0.62; P<0.001) and PCI (HR =0.24; 95% CI: 0.07–0.77; P=0.02) were identified as positive prognosis factors, while smoking index (HR =1.0010; 95% CI: 1.0004–1.0016; P<0.001), age (HR =1.03; 95% CI: 1.00–1.06; P=0.02), TNM stage (HR =2.06; 95% CI: 1.06–4.00; P=0.03), and N+ (HR =1.84; 95% CI: 1.05–3.23; P=0.03) were found to be negative prognosis factors (Table 2). Survival curves were plotted for each statistically significant variable (Figure 1A-1E). Notably, in the univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 2), stage III showed significantly worse survival than stage I. However, in the survival curve analysis (Figure 1E), when staging was considered as a three-level categorical variable, postoperative survival differences among stages did not reach statistical significance (P>0.05).

Table 2. Cox regression analysis of survival in SCLC.

| Variables | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| OS | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.36 (0.21–0.62) | <0.001 | 0.45 (0.24–0.85) | 0.01 | |

| Smoking index | 1.0010 (1.0004–1.0016) | <0.001 | 1.0011 (1.0004–1.0018) | 0.002 | |

| PCI | 0.24 (0.07–0.77) | 0.02 | 0.32 (0.10–1.05) | 0.06 | |

| Age | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.02 | 1.01 (0.97–1.04) | 0.65 | |

| Stage III | 2.06 (1.06–4.00) | 0.03 | 1.82 (0.63–5.29) | 0.27 | |

| N+ | 1.84 (1.05–3.23) | 0.03 | 1.50 (0.64–3.49) | 0.35 | |

| DFS | |||||

| N+ | 2.16 (1.27–3.67) | 0.004 | 1.97 (1.16–3.36) | 0.01 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.37 (0.18–0.79) | 0.01 | 0.44 (0.21–0.94) | 0.03 | |

CI, confidence interval; DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; N, node; OS, overall survival; PCI, prophylactic cranial irradiation; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer.

Figure 1.

OS curves of grouping variables with statistical significance in univariate Cox regression. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the OS of patients with SCLC who underwent surgical treatment. Subgroup analyses were performed for key prognostic factors identified in the univariate Cox regression, including (A) postoperative chemotherapy, (B) pathological lymph node status, (C) PCI, (D) smoking index, and (E) pathological staging. Chemotherapy and PCI: 0, no; 1, yes. OS, overall survival; PCI, prophylactic cranial irradiation; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer.

In the adjustment for potential confounding factors in the multivariate Cox regression analysis, only postoperative chemotherapy (HR =0.45; 95% CI: 0.24–0.85; P=0.01) and smoking index (HR =1.0011; 95% CI: 1.0004–1.0018; P=0.002) retained statistical significance (Table 2). Additionally, although PCI did not demonstrate a significant association with OS in the multivariate regression analysis (P=0.06), stratified survival curve analysis based on TNM stage revealed that PCI provided no significant prognostic benefit for stage I patients (Figure 2A). In contrast, PCI was associated with significant survival benefit in stage II and stage III patients (P=0.01) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for OS based on PCI and pathological stage. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the OS of patients with SCLC stratified by PCI status and pathological stage. Subgroup analyses were performed based on (A) stage I (n=43) and (B) stages II and III (n=78). PCI: 0, no; 1, yes. OS, overall survival; PCI, prophylactic cranial irradiation; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer.

Based on the grouping by postoperative chemotherapy status, the 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year OS rates for patients who did not receive chemotherapy were 69.0% (95% CI: 54.0–88.0%), 44.8% (95% CI: 29.9–67.1%), 30.3% (95% CI: 17.3–53.1%), 30.3% (95% CI: 17.3–53.1%), and 30.3% (95% CI: 17.3–53.1%), respectively; in contrast, the OS rates for patients who received chemotherapy were 91.2% (95% CI: 85.6–97.2%), 77.9% (95% CI: 69.8–86.9%), 67.1% (95% CI: 57.9–77.7%), 63.1% (95% CI: 53.6–74.2%), and 61.6% (95% CI: 52.0–73.0%) at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years, respectively. At all time points, the OS rates of patients who received chemotherapy were higher than those who did not. Regarding smoking index, patients with a smoking index >400 had 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year OS rates of 75.0% (95% CI: 63.7–88.3%), 58.3% (95% CI: 45.8–74.0%), 45.0% (95% CI: 32.7–61.8%), 40.0% (95% CI: 28.0–57.2%), and 40.0% (95% CI: 28.0–57.2%), respectively; for patients with a smoking index ≤400, the corresponding OS rates were 93.1% (95% CI: 87.4–99.1%), 77.6% (95% CI: 68.5–87.9%), 66.9% (95% CI: 56.7–79.0%), 65.2% (95% CI: 54.7–77.6%), and 63.3% (95% CI: 52.7–76.0%). At all time points, the OS rates for patients with a smoking index ≤400 were higher than those with a smoking index >400 (Table 3).

Table 3. OS and DFS rates in different subgroups.

| Variables | 1-year | 2-year | 3-year | 4-year | 5-year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS (%) | |||||

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| 0 | 69.0 (54.0–88.0) | 44.8 (29.9–67.1) | 30.3 (17.3–53.1) | 30.3 (17.3–53.1) | 30.3 (17.3–53.1) |

| 1 | 91.2 (85.6–97.2) | 77.9 (69.8–86.9) | 67.1 (57.9–77.7) | 63.1 (53.6–74.2) | 61.6 (52.0–73.0) |

| Smoking index | |||||

| >400 | 75.0 (63.7–88.3) | 58.3 (45.8–74.0) | 45.0 (32.7–61.8) | 40.0 (28.0–57.2) | 40.0 (28.0–57.2) |

| ≤400 | 93.1 (87.4–99.1) | 77.6 (68.5–87.9) | 66.9 (56.7–79.0) | 65.2 (54.7–77.6) | 63.3 (52.7–76.0) |

| DFS (%) | |||||

| N | |||||

| N+ | 51.5 (38.8–68.4) | 37.0 (25.0–54.6) | 34.5 (22.8–52.1) | 34.5 (22.8–52.1) | 31.4 (19.9–49.3) |

| N0 | 75.2 (65.3–86.5) | 65.6 (54.9–78.4) | 62.1 (51.1–75.3) | 60.1 (49.0–73.7) | 60.1 (49.0–73.7) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | |||||

| 0 | 61.7 (52.3–72.7) | 47.3 (37.9–59.1) | 43.5 (34.1–55.4) | 42.0 (32.7–54.0) | 40.2 (30.8–52.5) |

| 1 | 79.3 (65.9–95.5) | 72.2 (57.6–90.6) | 72.2 (57.6–90.6) | 72.2 (57.6–90.6) | 72.2 (57.6–90.6) |

Data are presented as survival rate (95% CI). Chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy: 0, no; 1, yes. CI, confidence interval; DFS, disease-free survival; N, node; OS, overall survival.

DFS

Using the same method described above, we analyzed the association of each variable with DFS. The results showed that only neoadjuvant chemotherapy (HR =0.37; 95% CI: 0.18–0.79; P=0.01) and pathological lymph node metastasis (HR =2.16; 95% CI: 1.27–3.67; P=0.004) were associated with prognosis (Table S3). Multivariate analysis further confirmed the statistical significance of these variables (P<0.05) (Table 2). Survival curves indicated that patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and those with negative lymph node status exhibited superior DFS (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

DFS curves of grouping variables with statistical significance in univariate Cox regression. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the DFS of patients with SCLC who underwent surgical treatment. Subgroup analyses were performed for key prognostic factors identified in the univariate Cox regression, including (A) preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy and (B) pathological lymph node status. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy: 0, no; 1, yes. DFS, disease-free survival; N, node; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer.

According to lymph node status, patients with N+ had 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year DFS rates of 51.5% (95% CI: 38.8–68.4%), 37.0% (95% CI: 25.0–54.6%), 34.5% (95% CI: 22.8–52.1%), 34.5% (95% CI: 22.8–52.1%), and 31.4% (95% CI: 19.9–49.3%), respectively. Patients without lymph node involvement had 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year DFS rates of 75.2% (95% CI: 65.3–86.5%), 65.6% (95% CI: 54.9–78.4%), 62.1% (95% CI: 51.1–75.3%), 60.1% (95% CI: 49.0–73.7%), and 60.1% (95% CI: 49.0–73.7%), respectively. At all time points, the DFS rates of N0 patients were consistently higher than those of N+ patients. Regarding neoadjuvant chemotherapy, patients who did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy had 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year DFS rates of 61.7% (95% CI: 52.3–72.7%), 47.3% (95% CI: 37.9–59.1%), 43.5% (95% CI: 34.1–55.4%), 42.0% (95% CI: 32.7–54.0%), and 40.2% (95% CI: 30.8–52.5%), respectively. In comparison, patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy had 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year DFS rates of 79.3% (95% CI: 65.9–95.5%), 72.2% (95% CI: 57.6–90.6%), 72.2% (95% CI: 57.6–90.6%), 72.2% (95% CI: 57.6–90.6%), and 72.2% (95% CI: 57.6–90.6%), respectively. At all time points, patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy had higher DFS rates than those who did not (Table 3).

Discussion

This study highlights the critical role of surgical intervention in improving the long-term survival of patients with SCLC, particularly when combined with postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Additionally, neoadjuvant chemotherapy and N0 demonstrated significantly associated with prolonged DFS, while a high smoking index was associated with poorer OS outcomes.

The findings regarding the positive association of postoperative chemotherapy with OS are consistent with previous studies. Zhou et al. conducted across retrospective study across five centers and systematically summarized the long-term survival of 164 patients with SCLC. Their main conclusion also emphasized the importance of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, regardless of mediastinal lymph node involvement (14). Similarly, Yang et al. reviewed the long-term survival data of patients with SCLC who underwent surgery combined with chemotherapy or postoperative chemoradiotherapy in the National Cancer Database from 2003 to 2011. The results showed that postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy was more effective in lymph node-negative patients. In addition, the study highlighted a significant underutilization of surgical intervention in early-stage SCLC (15). This reinforces the current clinical practice guidelines recommending adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with SCLC undergoing surgery.

This observation supports previous epidemiological findings that associate high smoking exposure with reduced survival in lung cancer patients (2). Smoking is a well-established risk factor for lung cancer progression and poor prognosis. Our study further found evidence for the association between a high smoking index and reduced survival in patients with SCLC, which is consistent with previous research (2). Ou et al. conducted a retrospective analysis of 4,782 patients with SCLC diagnosed between 1991 and 2005 across three counties in Southern California. They found that only 2.5% of the patients were never smokers, and smoking history was identified as an independent adverse prognostic factor for SCLC (16). Similarly, Huang et al. conducted a comprehensive analysis of 24 studies from the Illinois Lung Cancer Collaborative, systematically investigating the relationship between smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and SCLC. Their findings revealed a significant dose-response relationship between various quantitative smoking metrics and SCLC risk, with COPD mediating 0.70% to 7.55% of the total effect of smoking on SCLC (17). These results collectively underscore the critical role of smoking cessation in reducing both the incidence and progression of SCLC, highlighting its importance as an integral component of comprehensive cancer management.

The role of PCI in preventing brain metastases in SCLC is well established (18). However, due to its potential neurocognitive side effects and the uncertain survival benefit for early-stage SCLC, its application remains controversial (19). Xu et al. retrospectively analyzed 349 patients with SCLC who underwent surgery at their center between January 2006 and January 2014 to evaluate the prognostic impact of postoperative PCI. Their findings suggested that PCI was beneficial for stage II/III patients but not for stage I patients (20). Similarly, our study observed a survival benefit from PCI in stage II and III patients, while no significant advantage was noted for stage I patients. These results highlight the importance of a more selective approach to PCI and the need to balance the potential reduction in brain metastasis risk with the risk of neurocognitive side effects, particularly for patients with early-stage disease or longer expected survival.

The presence of N+ was significantly associated with poorer DFS in our study, consistent with its well-established role as a negative prognostic factor in SCLC. In our study, patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy had significantly higher DFS as compared to those who did not. However, the research on neoadjuvant chemotherapy in SCLC remains limited. These findings suggest that preoperative systemic treatment may play a crucial role in controlling disease progression and reducing postoperative recurrence. The benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy observed in our study supports its use as part of a multimodal approach in select patients with SCLC undergoing surgery. Interestingly, we found that neoadjuvant chemotherapy was significantly associated with improved DFS but not OS, whereas postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved OS but not DFS. One possible explanation is that neoadjuvant chemotherapy may reduce tumor burden and facilitate more complete surgical resection, thereby delaying recurrence. However, if recurrence still occurs, long-term survival may ultimately depend on the efficacy of postoperative systemic therapy. On the other hand, postoperative chemotherapy may have limited ability to prevent early recurrence but may extend survival after recurrence through better systemic disease control. Additionally, the recurrence events in our cohort mostly occurred early, suggesting that adjuvant chemotherapy might not delay the timing of recurrence but could prolong post-recurrence survival, resulting in improved OS without a corresponding DFS benefit (Figures S2,S3).

Despite the comprehensive analysis conducted in this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, due to the retrospective design, inherent biases—including selection bias and unmeasured confounding factors—could not be fully eliminated. Although we applied statistical adjustments and utilized the MissForest imputation method to address missing data and reduce information loss, this approach cannot fully account for bias introduced by unobserved variables, such as genetic or molecular markers, socioeconomic factors, and treatment adherence, which may have influenced both treatment selection and outcomes. Second, the relatively small overall sample size, and particularly the limited number of patients in key subgroups—such as those receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=30) or PCI (n=19)—restricted the statistical power to detect meaningful differences. Therefore, findings from these subgroup analyses should be interpreted with caution and viewed as hypothesis-generating. Future prospective, multicenter studies with larger and more diverse cohorts are warranted to validate and expand upon our findings.

Despite the predominant role of traditional chemotherapy in the treatment of SCLC, recent advances in targeted therapy and immunotherapy have brought new hope for this highly lethal disease. Notably, the combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies, with chemotherapy has demonstrated significant survival benefits in patients with ES-SCLC (21). However, the optimal integration of immunotherapy in patients with LS-SCLC, particularly in the perioperative and postoperative settings, requires further investigation. Additionally, targeted therapeutic strategies focusing on different molecular subtypes of SCLC, including targets such as MYC and DLL3, have emerged as promising research areas, potentially offering more precise treatment options for specific patient populations (21-23).

Future research directions should involve developing more effective multimodal treatment strategies, such as the combination of immunotherapy with targeted agents, identification of novel therapeutic targets, optimization of personalized treatment protocols based on molecular characteristics, and improvement of prognostic evaluation methods. These advancements are expected to further enhance long-term survival and improve the quality of life for patients with SCLC.

Conclusions

Our findings support the integration of surgical intervention with tailored perioperative strategies, particularly chemotherapy, as a valuable approach in managing LS-SCLC. The observed benefits of both neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy, along with the prognostic impact of nodal involvement, highlight the importance of individualized treatment planning. While PCI may reduce the risk of brain metastasis, its application in early-stage disease should be approached cautiously, and further research is needed to better define its role in this subgroup.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments, and was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (No. 20232450). The requirement for individual consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the analysis.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2025-490/rc

Funding: The work received funding from the Key R&D Project of Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Nos. 2024YFFK0235 and 2024YFFK0213).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2025-490/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

(English Language Editor: J. Gray)

Data Sharing Statement

Available at https://tlcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tlcr-2025-490/dss

References

- 1.Barnard WG. The nature of the “oat-celled sarcoma” of the mediastinum. J Pathol Bacteriol 1926;29:241-4. 10.1002/path.1700290304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gazdar AF, Bunn PA, Minna JD. Small-cell lung cancer: what we know, what we need to know and the path forward. Nat Rev Cancer 2017;17:725-37. 10.1038/nrc.2017.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:7-33. 10.3322/caac.21708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roof L, Wei W, Tullio K, et al. Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Overall Survival in SCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep 2022;3:100360. 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2022.100360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schreiber D, Rineer J, Weedon J, et al. Survival outcomes with the use of surgery in limited-stage small cell lung cancer: should its role be re-evaluated? Cancer 2010;116:1350-7. 10.1002/cncr.24853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Combs SE, Hancock JG, Boffa DJ, et al. Bolstering the case for lobectomy in stages I, II, and IIIA small-cell lung cancer using the National Cancer Data Base. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:316-23. 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lüchtenborg M, Riaz SP, Lim E, et al. Survival of patients with small cell lung cancer undergoing lung resection in England, 1998-2009. Thorax 2014;69:269-73. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganti AKP, Loo BW, Bassetti M, et al. Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;19:1441-64. 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takenaka T, Takenoyama M, Inamasu E, et al. Role of surgical resection for patients with limited disease-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2015;88:52-6. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Postoperative radiotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from nine randomised controlled trials. PORT Meta-analysis Trialists Group. Lancet 1998;352:257-63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06341-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Bentzen SM, Li J, et al. Relationship between neurocognitive function and quality of life after whole-brain radiotherapy in patients with brain metastasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;71:64-70. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.09.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Q, Li S, Zhang L, et al. Retrospective study of surgical resection in the treatment of limited stage small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer 2013;4:395-9. 10.1111/1759-7714.12035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wada H, Yokomise H, Tanaka F, et al. Surgical treatment of small cell carcinoma of the lung: advantage of preoperative chemotherapy. Lung Cancer 1995;13:45-56. 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00474-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou N, Bott M, Park BJ, et al. Predictors of survival following surgical resection of limited-stage small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021;161:760-771.e2. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.10.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang CJ, Chan DY, Shah SA, et al. Long-term Survival After Surgery Compared With Concurrent Chemoradiation for Node-negative Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann Surg 2018;268:1105-12. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ou SH, Ziogas A, Zell JA. Prognostic factors for survival in extensive stage small cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC): the importance of smoking history, socioeconomic and marital statuses, and ethnicity. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:37-43. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819140fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang R, Wei Y, Hung RJ, et al. Associated Links Among Smoking, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Pooled Analysis in the International Lung Cancer Consortium. EBioMedicine 2015;2:1677-85. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.09.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Früh M, De Ruysscher D, Popat S, et al. Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi99-105. 10.1093/annonc/mdt178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng H, Hao J, Dong B, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in patients with resected small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorac Cancer 2024;15:2309-18. 10.1111/1759-7714.15463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu J, Yang H, Fu X, et al. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation for Patients with Surgically Resected Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:347-53. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.09.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Megyesfalvi Z, Gay CM, Popper H, et al. Clinical insights into small cell lung cancer: Tumor heterogeneity, diagnosis, therapy, and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin 2023;73:620-52. 10.3322/caac.21785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel AS, Yoo S, Kong R, et al. Prototypical oncogene family Myc defines unappreciated distinct lineage states of small cell lung cancer. Sci Adv 2021;7:eabc2578. 10.1126/sciadv.abc2578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudin CM, Pietanza MC, Bauer TM, et al. Rovalpituzumab tesirine, a DLL3-targeted antibody-drug conjugate, in recurrent small-cell lung cancer: a first-in-human, first-in-class, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:42-51. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30565-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]