Abstract

Immunity to Plasmodium falciparum in African children has been correlated with antibodies to the P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) variant gene family expressed on the surface of infected red cells. We immunized Aotus monkeys with a subregion of the Malayan Camp variant antigen (MCvar1) that mediates adhesion to the host receptor CD36 on the endothelial surface and present data that PfEMP1 is an important target for vaccine development. The immunization induced a high level of protection against the homologous strain. Protection correlated with the titer of agglutinating antibodies and occurred despite the expression of variant copies of the gene during recurrent waves of parasitemia. A second challenge with a different P. falciparum strain, to which there was no agglutinating activity, showed no protection but boosted the immune response to this region during the infection. The level of protection and the evidence of boosting during infection encourage further exploration of this concept for malaria vaccine development.

Clinical immunity to malaria requires numerous and repeated exposure to the pathogen and can take years to develop (1). Ample evidence indicates that antibodies to the variant antigen, Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) (2–4), are a major component of protective immunity, particularly during early childhood (5–8). Variant antigens, however, are used by organisms to evade immunity and are not considered as good vaccine targets to control infection (9). Vast diversity, multiple copies, and clonal antigenic variation are the hallmark of these variant antigens leading to variant specific immune response (10, 11). Immunity to variants of PfEMP1 also results from multiple antibodies specific for each variant and not from cross-reactive epitopes (12). Why then should PfEMP1 be considered an appropriate candidate for a malaria vaccine? Besides its role in evasion of antibody-dependent immunity, PfEMP1 mediates the attachment of mature parasitized erythrocytes (PEs) to the host endothelium, a process that prevents clearance of mature parasites by the spleen (13; for review, see refs. 14 and 15). The immunodominant epitopes of PfEMP1 are likely to be the least cross-reactive, but the diversity of functional domains of PfEMP1 may be restricted to maintain function. Although PEs express antigenically distinct PfEMP1s, almost all bind to CD36 (16), a vital receptor for P. falciparum sequestration in the microvasculature (17, 18). This interaction is mediated by a 179-amino acid variant fragment (179 region) of the cysteine-rich interdomain region 1 (CIDR1) of PfEMP1 (19). Therefore, we immunized monkeys against this region from one PfEMP1 to determine whether it would lead to protection from parasite challenge, despite antigenic variation and the extensive diversity of PfEMP1s.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant Proteins.

The recombinant proteins y179 and the Plasmodium yoelii circumsporozoite protein (yPyCSP) were cloned into the YEpRPEU3 plasmid that supplied a C-terminal six-histidine tag. The proteins were expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae VK1 cells and purified from the supernatant by Ni-NTA chromatography (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) as described (20). Protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce). Endotoxin levels were determined by Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Charles River Endosafe, Charleston, SC). The final y179 product had <11 endotoxin units/mg compared with <1.2 units/mg for the yPyCSP.

Animals.

Twenty-four spleen-intact male Aotus nancymai monkeys, negative for evidence of Plasmodium infection and reactivity with Malayan Camp (MC) R+ parasites, were used. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in accordance with U.S. Public Health Service Policy, 1986 (protocol 1056-COL-MON-B). Starting 1 month before the vaccine trial, animals were observed daily by trained personnel, weighed weekly, and bled biweekly for complete blood count and serum collection, and as needed for clinical chemistry. All observations and laboratory values were recorded on a daily basis. Animals were under the supervision of a resident clinical veterinarian.

Immunization.

The monkeys were assigned to four trial groups of six monkeys each taking into consideration weight through the use of a table of random numbers for distribution to a group. Each animal was injected with 200 μg per injection of yeast recombinant protein in an adjuvant formulation. Groups I and II received three injections of yPyCSP and y179, respectively, on days 0, 28, and 56, with Freund's complete on day 0 and incomplete adjuvant on days 28 and 56. These monkeys were injected s.c. at four sites in the back. Groups III and IV received four intramuscular injections in the thighs of yPyCSP or y179, respectively, on days 0, 28, 56, and 84 with the MF59 adjuvant (Chiron).

Challenge Infections.

On day 114, each monkey was challenged with 50,000 MC R+ ring-stage PEs from a donor monkey. Parasitemia was followed daily by quantitative Giemsa-stained thick films according to the methodology of Earle and Perez (21). Parasite counts were recorded as PEs/μl of blood. Fifty-six days after the first challenge, all monkeys were drug treated and allowed to rest for 70 days. The monkeys were then challenged with 25,000 Vietnam Oak Knoll (FVO) ring-stage PEs and followed as above. Monkeys developing parasite counts higher than 200,000 PE/μl or developing a hematocrit lower than 20% were cured with mefloquine (20 mg) and quinine (50 mg). Blood was checked for subpatent parasites by nested PCR-based amplification (22). Samples from some of the primary and recrudescent peaks of parasitemia were inoculated into additional monkeys, and the resulting infected erythrocytes tested for antigenic phenotype by agglutination as described below. In some cases, immune sera were also collected from these monkeys.

Measurements of Immune Responses.

ELISA, agglutination, and flow cytometry assays were performed as described (23). ELISA was performed with glutathione S-transferase-179, y179, or yPyCSP at 1 μg/ml by using 1:5,000 dilution alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). Agglutination scores (0–5) were determined according to size and number of agglutinates as described (23). Flow cytometry was performed as described (23) with monkey sera diluted 1:250 followed by fluorescein-labeled goat anti-human IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) at 1:100 dilution. Results are given as median fluorescence intensity.

Results

Efficacy of the Vaccines Against the P. falciparum MC Challenge.

We vaccinated four groups of monkeys to determine the efficacy of the CIDR1 subdomain produced in S. cerevisiae (y179) in protecting A. nancymai monkeys from usually lethal P. falciparum challenge. Two groups were vaccinated with y179 or a control antigen, yPyCSP, in Freund's adjuvant (FA), and two were vaccinated with y179 or the control antigen in MF59, an adjuvant used for influenza vaccination (24). We challenged the monkeys with 50,000 Malayan Camp rosetting positive (MC R+) PEs and compared the efficacy of each formulation of y179 to its control group.

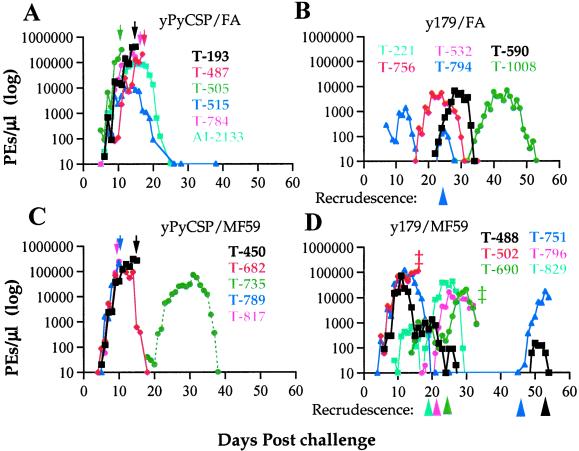

The monkeys vaccinated with y179 in FA demonstrated a very high level of protection. None of them developed parasitemia that required drug treatment compared with four of the six monkeys in the FA control group that received drug treatment (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Two monkeys of the y179/FA group never developed detectable parasitemia, and the peak parasitemia for the other four monkeys were between 1,400 and 6,700 PEs/μl, compared with an average of 211,939 PEs/μl (11,635–416,000) in the control monkeys. All y179/FA vaccinated monkeys had a delayed onset of parasitemia except for one monkey (T794) that rapidly suppressed the infection followed by a subsequent recrudescence on day 22 reaching 150 PEs/μl. This recrudescence as well as parasites from at least some of the monkeys having a significant delay in primary infection expressed a variant antigen phenotype that was antigenically distinct from the MCvar1 type expressed by parasites in the primary peak (Fig. 2). The highly significant delays in the prepatent period indicate that control of parasitemia was achieved by preexisting antibodies to PfEMP1 from the vaccination. This is supported by the presence of high PE agglutination titers in these monkeys before challenge (Table 1; see also Fig. 3). The four y179-vaccinated monkeys that had parasitemia during the study were positive by PCR at the end of the study, indicating persistent low grade parasitemia (Table 1). This suggests that PfEMP1-based vaccination leads to low-grade chronicity of the infection, and the monkeys harbored parasites without developing detectable parasitemia.

Figure 1.

Parasitemia in control and immunized monkeys challenged with MC R+ P. falciparum parasites. (A) yPyCSP/FA formulation (control); (B) y179/FA formulation; (C) yPyCSP/MF59 formulation (control); (D) y179/MF59 formulation. Parasitemia are given as PEs/μl on a log scale. Drug treatments for high parasitemia are indicated by down arrows, and appearances of secondary peak recrudescence are marked by arrowheads. ‡, Died during trial.

Table 1.

Homologous challenge of Aotus monkeys with MC R + P. falciparum parasites

| Monkey | Day of patency | Peak parasitemia (day)*

|

Drug treatment | PCR† (d56) | ELISA titer‡

|

Agglut. titer§

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||||

| yPyCSP/FA | |||||||||

| T-193 | 6 | 416,000 (15) | + | ND | <100 | <100 | 0 | 298 | |

| T-487 | 9 | 212,000 (17) | + | ND | <100 | <100 | 0 | 269 | |

| T-505 | 5 | 312,000 (11) | + | ND | <100 | <100 | 0 | 12 | |

| T-515 | 6 | 11,635 (14) | − | − | <100 | <225 | 0 | >625 | |

| T-784 | 5 | 236,000 (14) | + | ND | <100 | <100 | 0 | 309 | |

| AI-2133 | 5 | 84,000 (15) | − | − | <100 | <100 | 0 | 625 | |

| Average | 6 | 211,939 (14) | 4/6 | 0/2 | <100 | <100 | 0 | 490 | |

| y179/FA | |||||||||

| T-221 | >56 | 0 | − | − | 11,776 | 23,988 | >5,625 | >5,625 | |

| T-532 | >56 | 0 | − | − | 11,324 | 12,134 | >5,625 | >5,625 | |

| T-590 | 22 | 6,660 (30) | − | + | 18,535 | 19,861 | >5,625 | >5,625 | |

| T-756 | 16 | 5,580 (24) | − | + | 45,709 | 36,559 | >5,625 | >5,625 | |

| T-794 | 7 | 1,350 (13) | 150 (25) | − | + | 10,914 | 18,493 | 1,537 | >5,625 |

| T-1008 | 32 | 6,600 (44) | − | + | 5,395 | 2,606 | >5,625 | >5,625 | |

| Average | 31.5 | 3,365 (37) | 0/6 | 4/6 | 19,346 | 18,880 | >5,625 | >5,625 | |

| yPyCSP/MF59 | |||||||||

| T-450 | 5 | 272,000 (15) | + | ND | <100 | <100 | 0 | >625 | |

| T-682 | 5 | 112,000 (11) | − | + | <100 | <100 | 0 | ≥625 | |

| T-735¶ | 18 | 72,000 (31) | − | − | <100 | <100 | >125 | 214 | |

| T-789 | 6 | 212,000 (11) | + | ND | <100 | <100 | 0 | ≥625 | |

| T-817 | 6 | 256,000 (10) | + | ND | <100 | <100 | 0 | 126 | |

| Average | 8 | 184,800 (12) | 3/5 | 1/2 | <100 | <100 | 0 | 533 | |

| y179/MF59 | |||||||||

| T-488 | 5 | 74,000 (11) | 150 (50) | − | + | 117 | 579 | 625 | >5,625 |

| T-502 | 5 | 112,000 (16) | D17 | ND | 294 | 298 | 0 | 25 | |

| T-690 | 14 | 1,080 (18) | 20,000 (30) | −(D36) | ND | 671 | 2,089 | 625 | >5,625 |

| T-751 | 4 | 122,170 (12) | 16,920 (53) | − | + | 670 | 1,303 | 0 | 3,515 |

| T-796 | 17 | 20 (18) | 16,560 (25) | − | − | 774 | 565 | 3,858 | >5,625 |

| T-829 | 9 | 667 (14) | 41,632 (26) | − | + | 1,607 | 8,054 | 1,875 | >5,625 |

| Average | 9 | 51,656 (15) | 19,052 (37) | 0/5 | 3/4 | 614 | 1,910 | 1,057 | >5,625 |

Peak parasitemia of primary and secondary (recrudescence) are given as PEs/μl. The day of peak is in parentheses.

Blood collected from monkeys on last day of the trial (day 56) was tested for presence of P. falciparum parasites by PCR reaction.

Sera dilution that gave an OD of 0.5 by standard ELISA assay with glutathione S-transferase-179 (MC).

Lowest serum dilution that gave agglutination of 1+.

Monkey T-735 spontaneously developed antibodies that agglutinated MC R + PEs but did not react with y179 about 60 days before challenge. ND, not determined; D, died; day of death is superscript.

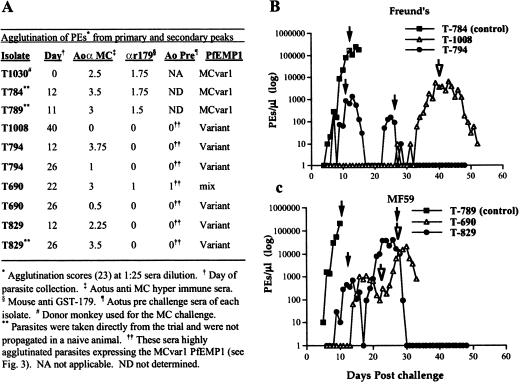

Figure 2.

Parasitemia and agglutination results with PEs taken from various peaks during the MC R+ challenge. (A) Agglutination scores of various isolates depicted at 1:25 sera dilution. Agglutination was scored as described (23). (B) Parasitemia courses in monkeys from the Freund's adjuvant groups (immunized and control) tested in A. Arrows indicate the day of challenge PEs were taken. (C) Parasitemia courses in monkeys from the MF59 adjuvant groups (immunized and control) tested in A. Arrows indicate the day of challenge PEs were taken.

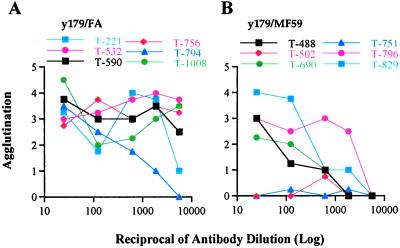

Figure 3.

Agglutination titers of y179 immunized monkeys with MC R+ parasites on day of MC R+ challenge. (A) y179/FA immunized monkeys; (B) y179/MF59 immunized monkeys.

Monkeys immunized with the y179/MF59 formulation showed variable degrees of protection, having higher overall peak parasitemia and shorter prepatent periods than monkeys immunized with y179/FA. Five of the six monkeys controlled their infection without treatment. The sixth monkey (T502) unexpectedly died after rapidly reaching parasitemia of 112,000 PEs/μl and was classified as a vaccine failure (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Another monkey, T-690, died on day 36 because of excessive internal bleeding from splenic rupture. The onset of parasitemia was delayed in three monkeys (T-796, T-690, and T-829) that had the lowest primary peaks in this group; in two of them, the primary infection was of recrudescences or a mixture of MCvar1 and recrudescent type (Fig. 2). One monkey in the control group, T-735, had a long delay in the onset of parasitemia. This animal developed agglutinating antibodies before challenge, which might explain the apparent protection, but was negative for antibodies to y179 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). We found recrudescence in all five monkeys in the y179/MF59 group that controlled their initial acute parasitemia (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Interestingly, some of the recrudescents developed into more substantial infections than in the primary peaks. Yet, none of these recrudescences required treatment.

Immunization Protects from Recrudescent Parasites Expressing Antigenically Distinct PfEMP1s.

One of our important goals was to show that the immunization protects from recrudescent parasites expressing variant PfEMP1. To establish this, we collected parasites from some of the primary and secondary peaks and tested a panel of sera for agglutination with these PEs at dilutions ranging from 1:10 to 1:3,125 (Fig. 2A and data not shown). To obtain sufficient amounts, parasites collected from vaccinated animals were inoculated into naive monkeys. The rapid progression to fulminant infection that required drug treatment (data not shown) indicated that these (recrudescent) parasites are highly virulent, yet fully controlled by the immunized monkeys.

Parasites from control animals expressed a MCvar1 type PfEMP1 (Fig. 2A). Contrary to that, all of the isolates from vaccinated monkeys expressed PfEMP1s different from MCvar1 except for T-690 from day 22, which had a mixture of MCvar1 and variant PfEMP1 (Fig. 2A). These PEs were not agglutinated by mouse anti-MC-179 sera or the monkey prechallenge sera but were agglutinated by Aotus anti-MC hyperimmune sera. Interestingly, PEs taken from peaks delayed only by 2–4 days also expressed PfEMP1 differently from the inoculums. Our results clearly show that immunization with y179 generated variant transcending protection within MC strain parasites.

Antibody Response to the 179 Region Is Boosted by Exposure to MC R+ Parasites.

We analyzed the antibody response among the various monkeys before and after challenge. We measured the specific response to the 179 region by ELISA against recombinant glutathione S-transferase-179 (19) and to PfEMP1 by PEs agglutination. The antibody response to glutathione S-transferase-179 was positive by ELISA in all y179 immunized animals. Agglutinating antibodies were found in 10 of the 12 y179 immunized monkeys before challenge and in all monkeys (immunized and control) after challenge (Table 1). The challenge with MC R+ parasites boosted the antibody titer in immunized monkeys, particularly in the y179/MF59 group that had initially lower antibody titers (Table 1). Of particular note was the absence of antibodies to the 179 region in the control groups after infection (except for T515), although they developed agglutinating antibodies after challenge (Table 1). This indicates that immunity to PfEMP1 induced by infection is directed against parts of the molecule outside the 179 region. In the y179/MF59 immunized group, the rise in agglutination titers was also associated in many monkeys with increased reactivity to the glutathione S-transferase-179 recombinant protein as measured by ELISA (Table 1). These results indicate that the 179 region is not only immunogenic when presented as recombinant protein but also that vaccination makes it a target for the immune system during the infection.

Protection Is Correlated with Antibody Response.

A number of malaria vaccine trials have shown measurable antiparasitic protection but failed to demonstrate correlation between the measured immune responses and the degree of protection (25–27). We measured immune responses to the y179 region and PfEMP1 to determine whether they correlate with protection. In general, we found association between antibody titers and protection. Monkeys in the y179/FA group had a higher degree of protection than those in the y179/MF59 group in line with the higher ELISA and agglutination responses of the former group (Table 1). Overall, although higher ELISA titers were not always associated with greater protection, they positively correlated (P < 0.01 by Spearman rank correlation) with lower parasitemia and extended prepatent period. We found even higher correlation between protection and agglutination titers (P < 0.0001), and agglutination titers of individual monkeys were associated with the degree of protection (Table 1 and Fig. 3). The one monkey (T-794) in the y179/FA group having parasites on day 7 had the lowest agglutination titer (Fig. 3A), but not ELISA response, in the group (Table 1). The two monkeys with the highest peak parasitemia in the y179/MF59 group, T-502 and T-751, had no agglutinating antibodies before challenge, although the ELISA titer of T-751 was similar to other monkeys in the group. In contrast, those that had higher agglutination titers, particularly T-796 and T-829, had the lowest peak parasitemia (Table 1). Thus, agglutination titers may serve as prechallenge indicators for the degree of protection.

Vaccination with y179 Does Not Protect from Challenge with Heterologous FVO Strain Parasites.

After demonstrating protection from homologous MC R+ challenge, we tested whether the immunization could protect from a highly virulent heterologous strain expressing a variant PfEMP1 (FVOvar1). We did not observe significant protection in any of the y179 immunized groups, and there were no significant differences in day of patency or reduction in peak parasitemia (Table 2). We attribute the apparent protection in the control FA group to the combined effect of the Freund's adjuvant and the high parasite burden experienced during the previous challenge. The difference in the number of animals requiring treatment may indicate some protection among y179/MF59 immunized monkeys but also could arise from the previous exposure to recrudescent parasites during the first challenge. We did not find any agglutination of FVO parasites with sera taken before the FVO challenge, and the monkeys developed FVO-specific agglutinating antibodies only after the challenge (Table 2). The lack of detectable agglutinating antibodies and the rapid increase in parasitemia can account for the lack of significant protection to this heterologous challenge. An unanticipated result of this challenge was the much higher antibody response to the FVO CIDR1 and the FVO-179 region developed in the y179 immunized monkeys (P < 0.018), although their agglutinating antibody titers were lower than in control monkeys (Table 2). Thus, despite the fact that immunization with y179 did not elicit strain transcending protective immunity, it effectively diverted the response to this normally silent region of PfEMP1 in a homologous and heterologous challenge. These findings provide evidence that additional exposure to parasites could induce variant and strain transcending protective immunity directed against the minimal CD36-binding region of PfEMP1.

Table 2.

Heterologous challenge of Aotus monkeys with FVO P. falciparum parasites

| Monkey | Day of patency | Peak* parasitemia | Drug treatment | FACS (median)† FVO-179

|

Agglut. titer‡

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||||

| yPyCSP/FA | |||||||

| T-193 | 6 | 259,200 (14) | + | 0.9 | 18.2 | 0 | >625 |

| T-487 | 7 | 10,908 (11) | − | 1.1 | 21.1 | 0 | >625 |

| T-505 | 6 | 96,660 (12) | − | 1.2 | 29.9 | 0 | <125 |

| T-515 | 7 | 515 (12) | − | 0.9 | 11.7 | 0 | <125 |

| T-784 | 7 | 69,328 (14) | − | 0.7 | 38.1 | 0 | >625 |

| Average | 7 | 87,322 (13) | 1/5 | 1.0 | 23.8 | 0 | 490 |

| y179/FA | |||||||

| T-221 | 7 | 236,000 (18) | + | 6.9 | 59.6 | 0 | >625 |

| T-532 | 6 | 48,268 (13) | D13 | 7.5 | NA | 0 | NA |

| T-590 | 6 | 47,208 (16) | D16 | 8.1 | 53.7 | 0 | NA |

| T-756 | 6 | 255,000 (16) | + | 63.6 | 159.9 | 0 | >625 |

| T-794 | 6 | 376,000 (14) | + | 4.2 | 97.1 | 0 | 517 |

| T-1008 | 8 | 252,000 (16) | + | 15.3 | 102.2 | 0 | 296 |

| Average | 7 | 202,413 (16) | 4/4 | 17.6 | 94.5 | 0 | <625 |

| yPyCSP/MF59 | |||||||

| T-450 | 7 | 132,000 (16) | − | 28.3 | 55.5 | 0 | >625 |

| T-682 | 7 | 1,091 (14) | − | 0.9 | 6.2 | 0 | 0 |

| T-735 | 8 | 244,000 (17) | + | 0.8 | 19.4 | 0 | >625 |

| T-789 | 6 | 376,000 (15) | + | 1.0 | 61.1 | 0 | >625 |

| T-817 | 7 | 244,000 (14) | + | 0.8 | 42.6 | 0 | >625 |

| Average | 7 | 199,418 (15) | 3/5 | 6.4 | 36.9 | 0 | >625 |

| y179/MF59 | |||||||

| T-488 | 5 | 384,000 (14) | + | 0.9 | 93.3 | 0 | 488 |

| T-751 | 7 | 136,000 (15) | − | 3.1 | 85.4 | 0 | >625 |

| T-796 | 7 | 2,727 (10) | − | 0.8 | 25.6 | 0 | 561 |

| T-829 | 7 | 14,908 (12) | − | 0.9 | 21.4 | 0 | ≤625 |

| Average | 7 | 134,409 (13) | 1/4 | 1.4 | 56.4 | 0 | <625 |

Peak parasitemia are given as PEs/μl. The day of peak is in parentheses.

Median fluorescence intensity of sera reactivity with Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing the 179 region of the FVO CIDR1 measured by flow cytometry.

Serum dilution that gave agglutination of 1+. NA, not applicable; D, died; day of death is superscript.

Discussion

Developing vaccines based on PfEMP1 may seem counterintuitive as these proteins evolved to evade host immunity. PfEMP1 is encoded by the large and diverse var gene family and is clonally expressed from a set of multiple copies (50 genes) of PfEMP1 that are highly variant (2–4). Switching between var genes (antigenic variation) can be very rapid (up to 2% per generation) (28), and the parasite expresses new PfEMP1s that are not recognized by antibodies raised against variants from previous exposures (13, 29). These new variants can escape anti-PfEMP1 immunity and rapidly develop into virulent infection.

Our strategy was to choose a functional region of PfEMP1, CIDR1, that may be conserved in structure for binding of CD36 (19) on endothelium. After immunization, the monkeys controlled the primary infection and subsequently the equally virulent recrudescent parasites that expressed antigenically different copies of PfEMP1. This indicates that immunization with this region could protect against severe infection and a diverse range of variants.

The lower immune responses and variable outcomes in animals immunized with y179/MF59 formulation are consistent with previous studies using MF59 as an adjuvant in Aotus monkeys (30). Nevertheless, most of the y179/MF59 monkeys were protected from high parasitemia during primary infection and recrudescence, although less than monkeys immunized with Freund's adjuvant. Our findings indicate that this immunogen may be effective even when eliciting moderate antibody responses. This suggests that other adjuvants suitable for use in humans that are less toxic than Freund's adjuvant but more effective than MF59 may provide high protective efficacy.

Antibodies may function to this region to induce blocking of adhesion, agglutination of infected erythrocytes, or opsonization of infected erythrocytes. Whatever the mechanism, immunization with this vaccine target led to highly effective immunity. Low grade parasitemia is unlikely to induce immunity or elicit antibodies to other proteins such as those related to parasite invasion. Higher initial parasitemia is usually required to protect against a second challenge. This was evident from the higher resistance to the FVO challenge among the Freund's adjuvant control animals compared with the susceptible y179 immunized monkeys that had only low grade parasitemia (maximum of 8,700 PEs/μl) during the MC challenge. We found a highly significant correlation between the degree of protection and anti-PfEMP1 antibodies that agglutinated infected erythrocytes. This correlation provides an important tool in developing PfEMP1-based vaccines, as it provides a link between in vitro assays and protection not found with other vaccine candidates (26, 27). Thus, other constructs of PfEMP1 can be tested for inducing broadly reactive antibodies against field isolates without the need to challenge during the development phases of the vaccine.

Children in Africa eventually develop immunity that protects against severe and clinical disease (1, 6, 8, 31). In the course of developing this immunity, they experienced many infections, including some that can be life threatening, and continue to be routinely exposed to parasites for years (1, 31, 32). These chronic, recurrent infections boost immunity that may recognize new variants and is associated with antibodies that agglutinate infected erythrocytes (5, 6, 8). The correlation between protection and agglutinating antibodies in this trial provide additional support that such protection is associated with PfEMP1 (5).

An ideal vaccine against P. falciparum blood-stage infections will rapidly accelerate the development of immunity and will prevent disease without compromising the natural immunity acquired by residents of endemic areas (1, 5, 31). Our study indicates that var gene vaccines may do just that in that they boost immunity without eliminating exposure to the parasite. We did not observe sterile immunity in most monkeys. The monkeys continued to harbor infected erythrocytes, detectable only by PCR, but suppressed development of significant infection, particularly in those animals with higher antibody titers. This type of immunity is typical of immune adults in regions of heavy malaria transmission who carry the blood infection at low levels of parasitemia without developing disease (1, 31, 32). Thus, a PfEMP1-based vaccine apparently accelerates immunity to other copies of PfEMP1 and may induce a young child to develop immunity similar to that in an older child without paying the price of frequent illness and sometimes death.

We found that although immunization with the MC R+ y179 region protected against variant PfEMP1s of MC parasites, it did not elicit agglutinating antibodies against FVO parasites and failed to protect against this strain. Overcoming this limitation is a major concern for this type of vaccine. It is conceivable that the rapid progression of the FVO infection, the most virulent P. falciparum strain in Aotus monkeys, did not allow sufficient time for effective immune responses to be mounted before the animals succumb to the infection. Thus, protection may be evident in a less virulent challenge or whether the proliferation of the parasite is attenuated by combining y179 with other vaccine candidates. Another possibility is that after immunization, further exposure to a limited number of infections will induce and facilitate the development of clinical protection. This is suggested by the boost in the antibody response to the respective 179 region by exposure to PEs expressing homologous and heterologous CIDR1 and was not observed in monkeys without y179 immunization (19). It is possible that this critical region is cryptic because of immunodominant variant epitopes in other regions of PfEMP1 (19, 23, 33). We provide data that immunization with y179 overcomes its cryptic nature and can lead to “determinant spreading” with subsequent P. falciparum infections (34).

Vaccines against blood stages of P. falciparum are in the early stages of development and field testing. Our approach to attack a functionally critical region of the variant antigen is a first step in directing immunity toward a molecule that is exposed to antibody for much of the parasite cycle and plays an important role in clinical immunity. Importantly, we have shown that antibodies to CIDR1 will protect against challenge and that this immunity spreads to other var genes. The objective of this approach is not to eliminate the parasite but instead to lead to low grade, asymptomatic parasitemia while boosting broad protection. We face many difficulties and challenges along the way, but whether we are able to develop immunogens that induce immunity to multiple CIDR1s and accelerate spreading of the immunity to that domain during natural infection, it will become an important component in future malaria vaccines.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carter Diggs, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Malaria Vaccine Development Program, for his support and Chiron for providing us the MF59 adjuvant. This work was supported in part by USAID Interagency Agreement No. 936-6001 between the Division of Parasitic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Abbreviations

- CIDR

cysteine-rich interdomain region

- CSP

circumsporozoite protein

- FA

Freund's adjuvant

- FVO

Vietnam Oak Knoll

- MC

Malayan Camp

- PE

parasitized erythrocyte

- PfEMP1

P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1

References

- 1.Dubois P, Pereira da Silva L. Res Immunol. 1995;146:263–275. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(96)80261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baruch D I, Pasloske B L, Singh H B, Bi X, Ma X C, Feldman M, Taraschi T F, Howard R J. Cell. 1995;82:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith J D, Chitnis C E, Craig A G, Roberts D J, Hudsontaylor D E, Peterson D S, Pinches R, Newbold C I, Miller L H. Cell. 1995;82:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90056-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su X Z, Heatwole V M, Wertheimer S P, Guinet F, Herrfeldt J A, Peterson D S, Ravetch J A, Wellems T E. Cell. 1995;82:89–100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bull P C, Lowe B S, Kortok M, Molyneux C S, Newbold C I, Marsh K. Nat Med. 1998;4:358–360. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bull P C, Lowe B S, Kortok M, Marsh K. Infect Immun. 1999;67:733–739. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.733-739.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta S, Snow R W, Donnelly C A, Marsh K, Newbold C. Nat Med. 1999;5:340–343. doi: 10.1038/6560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsh K, Otoo L, Hayes R J, Carson D C, Greenwood B M. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:293–303. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boslego J W, Tramont E C, Chung R C, McChesney D G, Ciak J, Sadoff J C, Piziak M V, Brown J D, Brinton C C, Jr, Wood S W, et al. Vaccine. 1991;9:154–162. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbour A G, Restrepo B I. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:449–457. doi: 10.3201/eid0605.000502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta S, Anderson R M. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:497–501. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01559-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newbold C I, Pinches R, Roberts D J, Marsh K. Exp Parasitol. 1992;75:281–292. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90213-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hommel M, David P H, Oligino L D. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1137–1148. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.4.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baruch D I. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 1999;12:747–761. doi: 10.1053/beha.1999.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho M, White N J. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C1231–C1242. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.6.C1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnwell J W, Asch A S, Nachman R L, Yamaya M, Aikawa M, Ingravallo P. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:765–772. doi: 10.1172/JCI114234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho M, Hickey M J, Murray A G, Andonegui G, Kubes P. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1205–1211. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newbold C, Warn P, Black G, Berendt A, Craig A, Snow B, Msobo M, Peshu N, Marsh K. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:389–398. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baruch D I, Ma X C, Singh H B, Bi X, Pasloske B L, Howard R J. Blood. 1997;90:3766–3775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stowers A W, Zhang Y, Shimp R L, Kaslow D C. Yeast. 2001;18:137–150. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20010130)18:2<137::AID-YEA657>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Earle W C, Perez Z M. J Lab Clin Med. 1932;17:1124–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snounou G. Methods Mol Biol. 1996;50:263–291. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-323-6:263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gamain B, Miller L H, Baruch D I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2664–2669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041602598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podda A. Vaccine. 2001;19:2673–2680. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00499-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrington D, Davis J, Nardin E, Beier M, Cortese J, Eddy H, Losonsky G, Hollingdale M, Sztein M, Levine M, et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:539–547. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ockenhouse C F, Sun P F, Lanar D E, Wellde B T, Hall B T, Kester K, Stoute J A, Magill A, Krzych U, Farley L, et al. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1664–1673. doi: 10.1086/515331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoute J A, Slaoui M, Heppner D G, Momin P, Kester K E, Desmons P, Wellde B T, Garcon N, Krzych U, Marchand M. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:86–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701093360202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts D J, Craig A G, Berendt A R, Pinches R, Nash G, Marsh K, Newbold C I. Nature (London) 1992;357:689–692. doi: 10.1038/357689a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fandeur T, Le Scanf C, Bonnemains B, Slomianny C, Mercereau-Puijalon O. J Exp Med. 1995;181:283–295. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inselburg J, Bathurst I C, Kansopon J, Barr P J, Rossan R. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2048–2052. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2048-2052.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snow R W, Marsh K. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:293–309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner G, Koram K, McGuinness D, Bennett S, Nkrumah F, Riley E. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:115–123. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sercarz E E, Lehmann P V, Ametani A, Benichou G, Miller A, Moudgil K. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:729–766. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehmann P V, Sercarz E E, Forsthuber T, Dayan C M, Gammon G. Immunol Today. 1993;14:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90163-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]