Abstract

Background

Conservative kidney management (CKM) is an established treatment option for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease(CKD) who are not candidates for kidney replacement therapy(KRT). Despite its benefits, CKM uptake remains low. This systematic review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of policy strategies designed to promote CKM uptake in advanced CKD patients.

Methods

Relevant studies were identified through searches of Medline, Scopus, and CINAHL databases since 2000 through 24 July 2024. Observational studies or randomized controlled trials that assessed the efficacy of interventions aiming to increase CKM utilization or preference in patients with chronic kidney disease were eligible for this study. Pairwise meta-analysis using the inverse variance or DerSimonion and Laird method, was applied to estimate the efficacy of interventions across studies.

Results

Seven studies were included in this systematic review. Education and training interventions which provided knowledge about CKM to patients and their families, did not significantly increased preference for CKM among CKD patients, compared to no intervention with a pooled OR of 1.05 (95% CI: 0.62–1.76; I2 = 0%). In contrast, results of two included studies found that strategies focused on reforming healthcare services, particularly through assessing patient prognosis and communicating results to nephrologists to inform decisions on KRT, significantly increased CKM utilization in patients with advanced CKD.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that educating patients and their families about CKM did not result in a statistically significant increase in CKM preference compared to no intervention. In contrast, interventions aimed at reforming healthcare services by implementing prognostication assessments into clinical practice might significantly increase CKM utilization. However, these conclusions are based on a limited number of observational studies, highlighting the need for further research to validate the effectiveness of these interventions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12882-025-04297-8.

Keywords: Conservative kidney management, Policy intervention, Chronic kidney disease, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global health challenge characterized by a gradual decline in kidney function, leading to significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in its advanced stages. In patients with advanced CKD progressing to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), kidney replacement therapy (KRT) becomes necessary when kidney function has deteriorated to the extent that the kidneys can no longer effectively eliminate metabolic waste and excess fluids. Available KRT options include hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation. Although these treatments can extend survival in patients with ESKD, certain populations—such as older adults and those with severe functional impairments—may derive limited survival benefit from these interventions. Previous studies have demonstrated that elderly patients undergoing hemodialysis experience a 2- to 4-fold higher mortality rate compared to younger patients, particularly in the early period following dialysis initiation [1, 2].

Additionally, dialysis patients frequently experience a decline in functional status and quality of life, often feeling less independent and less able to engage in social activities. Evidence from prior studies indicates that dialysis patients generally report a lower quality of life compared to individuals with other chronic conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, and osteoarthritis [3]. Moreover, approximately 30% of dialysis patients suffer from depression [4]. These factors add complexity to decision-making around KRT, particularly when the benefit of dialysis may not be clear. Thus, the decision to initiate KRT often requires careful consideration of factors such as the patient’s overall health status, quality of life, personal preferences, and the potential burdens of intensive treatment.

Conservative kidney management (CKM) provides a patient-centered approach focused on symptom management and psychosocial support, aiming to deliver holistic, individualized care [5]. For patients with ESKD, who are not candidates for KRT, such as older adults and those with multiple comorbidities, CKM is the best option, as dialysis does not prolong lifespan compared to not having dialysis, and dialysis may lead to significant deterioration in quality of life or further complications. Evidence from systematic reviews indicates no significant difference in survival between elderly patients undergoing dialysis and those opting for conservative management, with similar 1-year survival rates [6]. Furthermore, elderly patients who choose CKM reported improvements in quality of life, reduced symptom burden, fewer hospitalizations, and a greater likelihood of dying in their preferred setting [7].

Despite CKM being an established treatment option for patients with ESKD, its implementation remains inconsistent across healthcare systems. Factors such as physician education, patient awareness, and healthcare policies significantly influence the adoption of CKM in these patients. Thailand’s dialysis policy, which designates either peritoneal dialysis (PD) or hemodialysis (HD) as the default treatment under the Universal Coverage Scheme, has significantly influenced clinical practice. A recent study highlights how systemic factors favoring dialysis have resulted in the limited provision of conservative care for ESKD patients. This reflects not only a lack of opportunity but also limited motivation among healthcare providers to offer CKM as a viable option, regardless of their existing capacity and skills [8]. Additionally, results from qualitative studies [9] indicate that ESKD patients who do not receive dialysis experience numerous challenges, including unmanaged symptoms and complications like physical discomfort, psychological distress, and spiritual suffering during their final year at home. This underscores the critical need to carefully assess patient suitability for KRT and to strengthen CKM as an alternative option for patients who are not suitable candidates for KRT, both in Thailand and globally. Thus, this systematic review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of current policy strategies to enhance and promote the adoption of CKM for advanced CKD patients who may not be suitable candidates for KRT. The findings from this review will provide guidance to policymakers in Thailand and other countries for developing informed strategies to improve comprehensive CKD management practices.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were reported according to the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis guidelines (PRISMA).

Study searching

Studies were identified from three databases: Medline, Scopus and CINAHL from the year 2000 until 24 July 2024. The search terms were based on the population (i.e. chronic kidney disease, end stage kidney disease), intervention (i.e. conservative care, supportive care, palliative care) and outcomes (i.e. uptake, success, utilization). Details of the search terms and strategies of each database are presented in the Additional File 1: Additional Table 1.

Observational studies, quasi-experimental studies and randomized controlled trials (RCT) were eligible for this review if they met the following criteria (1) included participants with CKD, ESKD, or key stakeholders who are involved in the CKD patient’s care such as healthcare professionals or family members, and (2) assessed the effectiveness of interventions or policies designed to promote or improve the utilization or preference of CKM. The interventions of interest may include strategies or tools designed to inform or educate patients about CKM as an alternative treatment option for advanced CKD, communication training programs for healthcare providers to enhance discussions about CKM with patients, and reforms in healthcare processes or payment systems to promote CKM for patients with ESKD. In this review, CKM was referred to as an alternative treatment option for ESKD patients in place of KRT and does not encompass palliative or supportive care provided concurrently with KRT.

Study selection

Covidence systematic review software (version 2, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) was used to screen and select the studies. Titles and abstracts were selected independently by two reviewers and a third reviewer resolved any discrepancies. Study selection was based on full texts if the decision could not be made based on titles and abstracts. Full text selection was performed by two independent reviewers and any disagreements resolved by a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted the data including: Author’s name, year of publication, country, study design, types of funders and funding, intervention goal, target population for intervention, type of intervention, setting of intervention, specific name of intervention, intervention characteristics, health insurance context, duration of intervention, duration of follow-up, control characteristics, report on cost and its description. The total number of patients with and without the outcome were extracted. Any discrepancies in the data extraction among two reviewers process were resolved by a third reviewer.

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias using tools appropriate to each study design: the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB 2.0) for RCTs, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies and the risk of bias in non-randomized studies– of intervention tool (ROBINS-I) for quasi-experimental studies. The studies were graded according to each of the tools used. Any conflicts between two reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer through consensus.

Statistical analysis

Pairwise meta-analysis was conducted if at least three studies reported the effects of a similar intervention on the same outcome and provided sufficient data for analysis (i.e., the frequency of patients who experienced or did not experience the outcome in both intervention and control groups). Odds ratios (OR) were estimated for each study and were pooled using the inverse variance method if there was no heterogeneity between studies, or the random effects model (DerSimonion and Laird method) if heterogeneity was present. Q test and I2 statistic were used for assessing heterogeneity between studies. Heterogeneity was determined if I2 was ≥25% and/or P-value from Q test < 0.10.

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 18. P-value less than 0.05 was considered as the threshold for significance for all tests except for Q-tests, where P-value threshold less than 0.10 was used.

Results

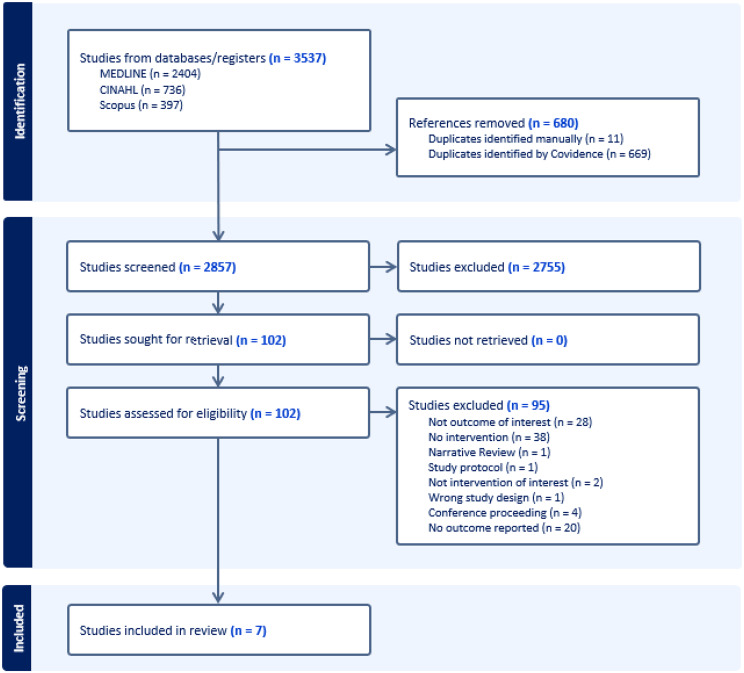

A total of 2,857 abstracts were screened of which 102 were relevant for full-text reviews, finally yielding 7 studies that met the inclusion criteria, encompassing a total of 961 patients with CKD. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram, detailing the number of studies excluded at the full-text stage along with the reasons for exclusion.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Risk of bias assessment

The results of risk of bias assessment are presented in Additional File 1: Additional Table 2 and Additional File 1: Additional Figs. 1 and 2. Of four observational studies, two and one studies were rated as fair and good quality, while one study had poor methodological quality based on the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. The two quasi-experimental studies were evaluated using the ROBINS-I and found to have a moderate risk of bias, while the RCT was assessed with the ROB2.0, showing some concerns regarding overall bias.

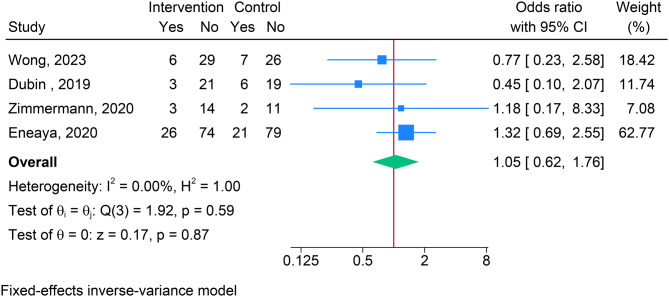

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of education and training interventions on preference for conservative kidney management among CKD patients

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Of the seven studies, one was an RCT [10], four were observational studies [11–14] and two were quasi-experimental studies [15, 16]. All studies included patients with CKD stage 4–5 with six studies focusing on pre-dialysis patients and one study focusing on both pre-dialysis and dialysis patients. All studies were conducted in high-income countries (HICs), with the majority (5 out of 7) carried out in the USA, one in the UK and one in Australia. The studies primarily included elderly participants, with two studies reporting a mean participant age of 65 or older and two studies reporting a mean age of 75 or older. All seven studies were conducted in tertiary care settings, with only one study involving general practices (GPs), thus incorporating primary care as well.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author, Year | Country | Study design | Age of participants | CKD stage | Dialysis status | Type of policy | Delivery of intervention | Targeted population | Setting of intervention | Intervention details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wong, 2023 | USA | RCT | ≥75 years | 4–5 | Pre-dialysis | Education and training | Patients and Families | Tertiary | 10-page booklet on Conservative Care Management | |

| Eneanya, 2020 | USA | Quasi-experimental | ≥65 years | 4–5 | Pre-dialysis | Education and training | In-person | Patients | Tertiary | Video vs verbal education to aid ESKD management decision making |

| Zimmermann, 2020 | USA | Prospective cohort | ≥75 years | 4–5 | Pre-dialysis | Education and training | In-person | Nephrologist | Tertiary | Best case/worst case communication tool |

| Dubin, 2019 | USA | Quasi-experimental | Not reported | 4–5 | Pre-dialysis | Education and training | Digital | Patients | Tertiary | Digital platform with VDO education, discussion groups, peer mentors, FAQs |

| Harrison, 2015 | UK | Prospective & retrospective cohort | ≥40 years | 5 | Pre-&post-dialysis | Reforming healthcare services | In-person and digital | Multi-disciplinary team | Tertiary and primary | Enrolling patients in the Supportive Care Register to refer patients to GP and palliative services |

| Salat, 2017 | USA | Prospective cohort | ≥65 years | 4–5 | Pre-dialysis | Reforming healthcare services | In-person | Multi-disciplinary team | Tertiary | Surprise Question use to help future planning |

| Kumarasinghe, 2020 | Australia | Prospective & retrospective cohort | ≥50 years | 4–5 | Pre-dialysis | Education and Reforming healthcare services | In-person | Multi-disciplinary team | Tertiary | Clinical Frailty Score assessment to promote advanced care planning |

Effectiveness of interventions

The interventions were categorized into two primary groups: (1) education and training, and (2) reforming healthcare services. Four studies evaluated the effectiveness of educational interventions, two studies examined the impact of reforming healthcare services, and one study assessed the combined effects of both intervention types.

Education and training

The educational interventions targeted both patients and their family, providing knowledge about conservative care management as an alternative treatment of advanced CKD. These interventions were delivered through various methods, including booklets [10], face-to-face interactions [16], videos [16], and online platforms [15], to help patients and their families participate in shared decision-making with healthcare providers regarding the available options of KRT. In addition, education and training interventions were also focused on health care providers with [14] training nephrologists to use best-case/worst-case scenarios to facilitate more effective communication of CKM as an alternative treatment option for patients with ESKD.

The effect of interventions on the occurrence of outcomes are presented in Table 2. All four studies assessing the effect of educational and training intervention, measured outcomes in terms of patient preference for CKM. Only one study reported on increased CKM utilization. Therefore, meta-analysis could be conducted only for the outcome of CKM preference. The meta-analysis results indicate that educational and training interventions did not significantly increased preference for CKM among CKD patients compared to no intervention with a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 1.05 (95% CI: 0.62–1.76; I2 = 0%), see Fig. 2. For CKM utilization, Zimmermann et al. found that educational and training interventions also increased the rate of CKM utilization, though this result was not statistically significant (OR = 1.60; 95% CI: 0.13–19.84).

Table 2.

The effectiveness of interventions of the included studies

| Author | Year | Outcome | Intervention | Comparator | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Having outcome | Not having outcome | Having outcome | Not having outcome | |||||

| Education and training | ||||||||

| Wong | 2023 | Preference of CKM | 6 | 29 | 7 | 7.0 | 0.77 | 0.23–2.58 |

| Zimmermann | 2020 | Preference of CKM | 3 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 1.18 | 0.17–8.33 |

| Zimmermann | 2020 | CKM utilization | 2 | 15 | 1 | 12 | 1.6 | 0.13–19.84 |

| Eneaya | 2020 | Preference of CKM | 26 | 74 | 21 | 21 | 1.32 | 0.69–2.55 |

| Dubin | 2019 | Preference of CKM | 3 | 21 | 6 | 6 | 0.45 | 0.10–2.07 |

| Reforming healthcare services | ||||||||

| Salat | 2017 | Preference of CKM | 23 | 148 | 6 | 6 | 8.06 | 3.21–20.20 |

| Harrison | 2015 | CKM utilization | 25 | 15 | 4 | 47 | 19.58 | 5.87–65.34 |

| Combined education & Reforming healthcare services | ||||||||

| Kumarasinghe | 2018 | Preference of CKM | 17 | 65 | 3 | 3 | 4.62 | 1.28–16.62 |

Reforming healthcare services

Two prospective cohort studies assessed the impact of reforming healthcare services on CKM outcomes. In both studies, restructuring involved the use of the “surprise question”—“Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months?”. Responses from the renal multidisciplinary team were documented in patients’ electronic health records, thereby establishing a supportive care register. This register functioned to notify family physicians or general practitioners, prompting timely referrals to CKM services. For the outcome of CKM utilization, Harrison et al. [11] found that implementing the “surprise question” and communicating responses to general practitioners significantly increased CKM uptake among patients with advanced CKD (OR = 19.58; 95% CI: 5.87–65.34), see Table 2. Similarly, in terms of CKM preference, findings from Salat et al. indicated that reforming healthcare services with the “surprise question” significantly heightened CKM preference compared to no intervention (OR = 8.06; 95% CI: 3.21–20.20).

Combination of education and reforming healthcare services

Only one study [12] has examined the combined effect of educational intervention and reforming healthcare service on CKM preference. This study employed mortality prediction tools to assess frailty in patients with ESKD, with the findings shared with nephrologists to guide decision-making regarding KRT options. The study’s results indicate that evaluating health status and mortality risk in CKD patients prior to undergoing KRT significantly increased the preference for CKM in the advanced CKD patients compared to no intervention (OR = 4.62; 95% CI: 1.28–16.62), see Table 2.

Discussion

The results of this systematic review suggest that reforming healthcare services, as well as implementing combined educational and service reforming interventions, significantly enhance both the preference for and utilization of CKM among patients with advanced CKD. In contrast, interventions focused solely on education did not yield similar improvements. These findings, however, are based on a limited number of studies with small sample sizes. Thus, this review highlights the scarcity of research on CKM for patients with advanced CKD, underscoring an evidence gap that may hinder the development of effective policy support for these interventions.

Kidney replacement therapy is a widely recognized treatment for patients with ESKD; however, it is not suitable for all patients. Conservative care choice is a well-established alternative treatment for patients with advanced CKD who are not ideal candidates for dialysis or kidney transplantation. Although CKM can improve quality of life and reduce symptom burden in these patients, CKM remains underutilized due to various access barriers existing on both the patient and healthcare provider sides [7]. Many patients receive little to no information about CKM from their healthcare providers [17] and may not understand that the risks and benefits of dialysis and kidney transplantation largely depend on individual health status. Additionally, there also may be differences in the information patients receive from nephrologists and what patients understood [18]. Healthcare providers, meanwhile, face challenges such as limited knowledge, inadequate training, time constraints, and insufficient resources to assess patient suitability for dialysis and to effectively discuss the risks and benefits of both dialysis and CKM with their patients [19].

Although a lack of knowledge and information about CKM may represent a significant barrier to its utilization and preference among patients, our study found that providing intervention solely focused on education did not significantly increase its utilization or preference among patients with advanced CKD. This lack of significant impact may be attributable to the limited number of studies and small sample sizes, which could reduce the power to detect differences between patients receiving the intervention and those who did not.

In contrast to educational interventions, our study found that reforming healthcare services by implementing prognostic assessments into nephrologist daily practice may be a strategy to increase uptake of CKM [20]. By using this tool to identify patients with a low probability of survival and subsequently referring them to receive CKM, healthcare providers were able to improve CKM utilization. Tools like the surprise question and the Clinical Frailty Score can assist in prognostication and alert healthcare providers to consider future management options, especially in time-limited scenarios. Both communication and understanding the patient’s illness trajectories are critical components of advanced care planning, which will ensure patients receive care that is personalized and suited to their values and preferences [21].

In addition to knowledge and awareness, the accessibility and quality of CKM are critical factors for increasing its utilization. Findings from the 2018 Global Kidney Health Atlas survey, which assessed the accessibility and quality of CKM services worldwide [22], indicated that the overall quality of CKM care was suboptimal, especially in low and middle-income countries including Thailand. Key deficiencies included limited training for healthcare providers in delivering conservative kidney management, inadequate incorporation of shared decision-making, insufficient psychological, cultural, and spiritual support, and underuse of multidisciplinary teams. Furthermore, the quality of CKM not only varies between countries but also likely differs within countries, influenced by individual nephrologists’ beliefs, attitudes, and their ability or willingness to discuss CKM and prognosis with patients. In Thailand, to address this gap, the Clinical Practice Recommendation for Conservative Kidney Management has been in place since 2017. In addition, CKD clinics staffed by multidisciplinary care teams have been established at the primary care level [23], aiming to enhance both the quality and equity of CKM services.

The study by Harrison et al. established a supportive care registry that connected the kidney multidisciplinary team with family physicians and palliative care services through an almost fully automated electronic communication system. This collaboration led to a statistically significant increase in the uptake of palliative services, highlighting the importance of teamwork in delivering effective CKM [11]. The electronic system offered advantages such as automatically generated emails and a user-friendly platform for linking different care team [24].

The strategies employed in our included studies aimed to inform patients about future management options, provide communication training for healthcare professionals, and prompt the treating renal team to consider the patient’s prognosis and future management plans. In contrast to a sister review conducted by our research team on strategies to improve the uptake of home hemodialysis, this review found no studies that utilized financial incentives for providers or quality improvement programs aimed at monitoring and enhancing the quality of care for these patients [25]. This may be attributed to the fact that CKM occupies a relatively low position on the policy agenda due to its low and short-term financial implications and the limited number of patients accessing CKM. Clinicians and policymakers may overlook the potential of CKM to significantly reduce costs associated with dialysis and improve patients’ quality of life when provided to appropriate patients who are not suitable for dialysis.

This is the first systematic review to focus specifically on strategies aimed at increasing the uptake and preference for CKM among patients with advanced CKD. This study did not assess the impact of CKM itself, as evaluating outcomes of CKM would require a different approach, including distinct search terms. Additionally, well-conducted studies already address that aspect [26–28]. Our review evaluated the effectiveness of policy interventions worldwide, encompassing a range of study designs and various intervention types. However, this study has several limitations, primarily due to the small number of included studies and the variability in study designs, intervention types, and outcomes assessed. Consequently, a meta-analysis could only be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of educational interventions in increasing the preference for CKM. Moreover, most of the included studies are observational studies, which may introduce confounding bias into the observed benefits of reforming healthcare services and combined restructuring with educational interventions. Additionally, all included studies were conducted in high-income countries, reflecting a lack of evidence from LMICs. As a result, our findings may not be generalizable to LMICs. Therefore, additional RCTs and other studies conducted in LMICs are needed to confirm the effectiveness of these interventions in increasing CKM utilization and to provide policymakers with the evidence necessary to support the implementation of both CKM preference and utilization globally. In addition, the outcomes in the included studies are predominantly reported as preference for CKM rather than actual CKM uptake. Preference for CKM reflects the patient’s choice at the time of the intervention or within a few months afterward and may not represent the patient’s final management decision. Finally, we did not search for relevant studies in grey literature databases, which makes our results may be susceptible to publication bias.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that educating patients and their families about CKM did not result in a statistically significant increase in CKM preference compared to no intervention. Reforming healthcare services and implementing combined educational and service restructuring interventions may be effective strategies to increase both the preference for and utilization of CKM among patients with advanced CKD. However, these conclusions are based on a limited number of small observational studies, highlighting the need for further research on CKM in advanced CKD. Thus, additional RCTs are essential to strengthen the evidence base and support the development of effective policy interventions for promote CKM utilization in advanced CKD patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all parties involved in the Commission: The Learning Committee, chaired by Prof. Emeritus Kriang Tungsanga. Prof. Vivekanand Jha; The National Health Security Office’s Working Group, chaired by Prof. Kearkiat Praditpornsilpa; and the Secretariat team of both the Committee and the Working Group. Their invaluable guidance and feedback have been instrumental throughout the research.

Abbreviations

- CKM

Conservative Kidney Management

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- ESKD

End-stage kidney disease

- GPs

General practices

- HICs

High income countries

- KRT

Kidney replacement therapy

- LMICs

Low and middle-income countries

- OR

Odds ratio

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- ROB2

Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool

- ROBIN-I

Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies - of Interventions

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

Author contributions

NC, TA, YT, NY planned the protocol and NC and TA searched for eligible studies. NC, TA, YT, NY, NT, HA, YMT, DP, RN selected the studies. NC, TA, NT, HA, YMT and DP extracted data and assessed risk of bias. NC and TA were involved in the data analysis. NC, TA and YT were involved in the writing of the manuscript. NC and TA are responsible for the overall content as guarantors and accept full responsibility for the work and conduct of the study, access to the data and controlled the decision to publish. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding

This study was funded by the Health Systems and Research Institute (HSRI), Thailand (grant number HSRI 67-067), and the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) through the Program Management Unit for Human Resources & Institutional Development, Research and Innovation (B41G670025). The funders had no role in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies. The Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP) Foundation in Thailand supports evidence-informed priority-setting and decision-making in healthcare and is funded by both national and international public agencies.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and Additional information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Berger JR, Jaikaransingh V, Hedayati SS. End-stage kidney disease in the elderly: Approach to dialysis initiation, choosing modality, and predicting outcomes. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016;23(1):36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradbury BD, Fissell RB, Albert JM, Anthony MS, Critchlow CW, Pisoni RL, Port FK, Gillespie BW. Predictors of early mortality among incident US hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns study (DOPPS). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(1):89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka M, Ishibashi Y, Hamasaki Y, Kamijo Y, Idei M, Kawahara T, Nishi T, Takeda M, Nonaka H, Nangaku M, et al. Health-related quality of life on combination therapy with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in comparison with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: A cross-sectional study. Perit Dial Int. 2020;40(5):462–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santos PR, Capote Junior J, Cavalcante Filho JRM, Ferreira TP, Dos Santos Filho JNG, da Silva Oliveira S. Religious coping methods predict depression and quality of life among end-stage renal disease patients undergoing hemodialysis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanini I, Samoni S, Husain-Syed F, Fabbri S, Canzani F, Messeri A, Mediati RD, Ricci Z, Romagnoli S, Villa G. Palliative care for patients with kidney disease. J Clin Med. 2022;11(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Foote C, Kotwal S, Gallagher M, Cass A, Brown M, Jardine M. Survival outcomes of supportive care versus dialysis therapies for elderly patients with end-stage kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol (Carlton). 2016;21(3):241–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buur LE, Madsen JK, Eidemak I, Krarup E, Lauridsen TG, Taasti LH, Finderup J. Does conservative kidney management offer a quantity or quality of life benefit compared to dialysis? A systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Botwright S, Teerawattananon Y, Yongphiphatwong N, Phannajit J, Chavarina KK, Sutawong J, Nguyen LKN. Understanding healthcare demand and supply through causal loop diagrams and system archetypes: Policy implications for kidney replacement therapy in Thailand. BMC Med. 2025;23(1):231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bristowe K, Selman LE, Higginson IJ, Murtagh FEM. Invisible and intangible illness: A qualitative interview study of patients’ experiences and understandings of conservatively managed end-stage kidney disease. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8(2):121–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong SPY, Oestreich T, Prince DK, Curtis JR. A patient decision aid about conservative kidney management in advanced kidney disease: A randomized Pilot trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;82(2):179–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison JK, Clipsham LE, Cooke CM, Warwick G, Burton JO. Establishing a supportive care register improves end-of-life care for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephron. 2015;129(3):209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumarasinghe AP, Chakera A, Chan K, Dogra S, Broers S, Maher S, Inderjeeth C, Jacques A. Incorporating the clinical frailty scale into routine outpatient nephrology practice: An observational study of feasibility and associations. Intern Med J. 2021;51(8):1269–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salat H, Javier A, Siew ED, Figueroa R, Lipworth L, Kabagambe E, Bian A, Stewart TG, El-Sourady MH, Karlekar M, et al. Nephrology provider prognostic perceptions and care delivered to older adults with advanced kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(11):1762–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmermann CJ, Jhagroo RA, Wakeen M, Schueller K, Zelenski A, Tucholka JL, Fox DA, Baggett ND, Buffington A, Campbell TC, et al. Opportunities to improve shared decision making in dialysis decisions for older adults with life-limiting kidney disease: A Pilot study. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(5):627–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubin R, Rubinsky A. A digital modality decision program for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. JMIR Form Res. 2019;3(1):e12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eneanya ND, Percy SG, Stallings TL, Wang W, Steele DJR, Germain MJ, Schell JO, Paasche-Orlow MK, Volandes AE. Use of a supportive kidney care video decision aid in older patients: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Nephrol. 2020;51(9):736–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakthivel P, Mostafa A, Aiyegbusi OL. Factors that influence the selection of conservative management for end-stage renal disease - a systematic review. Clin Kidney J. 2024;17(1):sfad269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamroun A, Speyer E, Ayav C, Combe C, Fouque D, Jacquelinet C, Laville M, Liabeuf S, Massy ZA, Pecoits-Filho R, et al. Barriers to conservative care from patients’ and nephrologists’ perspectives: The CKD-REIN study. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant. 2022;37(12):2438–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adenwalla SF, O’Halloran P, Faull C, Murtagh FEM, Graham-Brown MPM. Advance care planning for patients with end-stage kidney disease on dialysis: Narrative review of the current evidence, and future considerations. J Nephrol. 2024;37(3):547–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Javier AD, Figueroa R, Siew ED, Salat H, Morse J, Stewart TG, Malhotra R, Jhamb M, Schell JO, Cardona CY, et al. Reliability and utility of the surprise question in CKD stages 4 to 5. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(1):93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holley JL. Palliative care in end-Stage renal disease: Illness trajectories, communication, and hospice use. Adv Chronic Kidney Disease. 2007;14(4):402–08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lunney M, Bello AK, Levin A, Tam-Tham H, Thomas C, Osman MA, Ye F, Bellorin-Font E, Benghanem Gharbi M, Ghnaimat M, et al. Availability, accessibility, and quality of conservative kidney management worldwide. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;16(1):79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watcharananan Y, Pongsittisak W. Developing a chronic kidney disease clinic in primary care. J Appl Psychol The Nephrology Society Of Thailand. 2022;28(1):39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azamar-Alonso A, Costa AP, Huebner LA, Tarride JE. Electronic referral systems in health care: A scoping review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;11:325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yongphiphatwong Nea: The way home: A scoping review of Public health strategies to Increase the utilization of home dialysis in chronic kidney disease patients. In. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Ren Q, Shi Q, Ma T, Wang J, Li Q, Li X. Quality of life, symptoms, and sleep quality of elderly with end-stage renal disease receiving conservative management: A systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voorend CGN, van Oevelen M, Verberne WR, van den Wittenboer ID, Dekkers OM, Dekker F, Abrahams AC, van Buren M, Mooijaart SP, Bos WJW. Survival of patients who opt for dialysis versus conservative care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant. 2022;37(8):1529–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong SPY, Rubenzik T, Zelnick L, Davison SN, Louden D, Oestreich T, Jennerich AL. Long-term outcomes among patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis: A systematic review. JAMA Netw Open Open. 2022;5(3):e222255–222255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and Additional information files.