Abstract

Pancreatic development is a classic example of epithelium–mesenchyme interaction. During embryonic life, signals from the mesenchyme control the proliferation of precursor cells within the pancreatic epithelium and their differentiation into endocrine or acinar cells. It has been shown that signals from the mesenchyme activate epithelial cell proliferation but repress development of the pancreatic epithelium into endocrine cells. Here, experiments with specific inhibitors established that mesenchymal effects on epithelial cell development depended on the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Then we demonstrated that these effects of the mesenchyme were mimicked by fibroblast growth factor 7 (FGF7), a specific ligand of FGFR2IIIb, which is a tyrosine kinase receptor of the FGF-receptor family. When pancreatic epithelium expressing FGFR2IIIb was grown with FGF7, epithelial cell growth occurred in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas endocrine tissue development was repressed. The epithelial cells that proliferated in response to FGF7 were endocrine pancreatic precursor cells, as shown by their differentiation en masse into endocrine cells on FGF7 removal. Thus, efficient propagation of pancreatic progenitor cells can be achieved in vitro by exposure to FGF7, which does not affect their ability to differentiate en masse into endocrine cells on FGF7 removal.

Epithelium–mesenchyme interactions play crucial roles during organogenesis. These interactions are mediated at least in part by soluble factors produced by the mesenchyme and acting on the epithelium (1). Normal pancreatic development cannot occur without these interactions (2, 3). The mature pancreas is composed of endocrine tissue that produces hormones (insulin and glucagon) and acinar tissue that produces enzymes (amylase and carboxypeptidase A). The development of as-yet-unidentified progenitor cells located within the epithelium into mature cells may be controlled by signals from the surrounding mesenchyme (4, 5).

Various published data suggest that epithelium–mesenchyme interactions in the pancreas may be mediated by members of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) family. The four distinct FGFR genes identified to date (FGFR1 to -4) encode a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain and an extracellular region composed of two or three Ig-like domains (called loops I, II, and III). Ligand specificity is determined by the C-terminal domain of loop III. In the case of FGFR1–3, alternative exon usage exists at the level of loop III, giving rise to the IIIb and IIIc isoforms (6). FGFR2IIIb seems to be a key receptor for pancreatic development: this last is altered in mice expressing a dominant-negative form of FGFR2IIIb or no FGFR2IIIb (7, 8). Important unresolved questions include whether FGFR2IIIb-mediated signals act directly on the pancreatic epithelium (7, 9), and whether they control pancreatic epithelial cell proliferation or differentiation.

In the present study, we monitored the effects of FGFR2IIIb-mediated signals on pancreatic development, paying special attention to the development of endocrine cells. We used rat embryonic pancreatic epithelium grown in vitro with or without its surrounding mesenchyme. In earlier studies conducted with the same experimental system, signals from the mesenchyme activated epithelial cell proliferation and repressed endocrine cell differentiation (10). We found evidence that this repressive effect of the mesenchyme on endocrine cell differentiation required a functional mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling pathway. Then we showed that fibroblast growth factor 7 (FGF7), which binds only to FGFR2IIIb (11), activated pancreatic epithelial cell proliferation and repressed endocrine cell differentiation. The epithelial cells that grew when exposed to FGF7 were precursors of endocrine cells, as shown by their differentiation en masse into endocrine cells on FGF7 removal. Taken together, these data indicate that FGFR2IIIb-mediated signals are implicated in the activation of pancreatic progenitor cell growth. Use of FGFR2IIIb-mediated signals to expand pancreatic endocrine progenitor cells could allow detailed characterization of these cells and could serve to produce large amounts of β cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Pancreatic Dissection.

Pancreases were dissected from rat embryos on embryonic day (E)13.5. The pancreatic epithelium was separated from its surrounding mesenchyme as described previously (12). The dorsal pancreatic rudiments with (M+) or without (M−) their mesenchyme were grown into three-dimensional collagen gels (12). The culture medium consisted of RPMI medium 1640 containing penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), Hepes (10 mM), l-glutamine (2 mM), nonessential amino acid, and heat-inactivated 1% FCS (HyClone). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere composed of 95% air and 5% CO2. Human recombinant FGF7 (R & D Systems) was diluted in PBS containing 0.1% BSA. The growth factor or its vehicle (PBS with 0.1% BSA) was added every day to the culture medium. PD98059 (Calbiochem) was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and used in a dose of 50 μM. Comparable DMSO concentrations were added to control cultures. Human recombinant protein replicating the extracellular domain of FGFR2IIIb (R & D Systems) was used in a final concentration of 5 μg/ml.

During the last hour of culturing, BrdUrd (10 μM) was added to label cells in the S phase.

At the indicated times, the pancreatic rudiments were photographed, removed from the collagen gel, and fixed for immunohistochemistry, as described below.

Insulin Content.

For insulin content determinations, rudiments were homogenized, and insulin was extracted in acid alcohol (1.5% HCl/75% EtOH). For insulin secretion measurement, rudiments were incubated in 250 μl of Krebs buffered solution (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 37°C, then in 250 μl of Krebs buffered solution supplemented with 1.67 mM d-glucose for 1 h at 37°C, and finally with 16.7 mM d-glucose for 1 h at 37°C (total incubation time, 3 h). Immunoreactive insulin was measured by RIA, as previously described (13).

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcriptase) (RT)-PCR.

Total RNAs from E13.5 pancreatic epithelium or mesenchyme were extracted by the guanidinium isothiocyanate method (14). RT-PCR was performed according to the standard protocol (15). Briefly, total RNAs first treated for 30 min at 37°C with RNase-free DNase (GIBCO/BRL) were used to prepare cDNAs with random hexamers as the primers. The reaction was performed with (RT+) or without (RT−) murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (GIBCO/BRL). The following sets of primers were used for the PCR:

Cyclophilin (forward), 5′-CAGGTCCTGGCATCTTGTCC-3′

Cyclophilin (reverse), 5′-TTGCTGGTCTTGCCATTCCT-3′

FGFR4 (forward), 5′-AAGGATTTGGCAGACCTGATCTC-3′

FGFR4 (reverse), 5′-TGCACTTCCGAGACTCCAGATAC-3′

FGFR2IIIb (forward), 5′-AACGGTCACCACACCGGC-3′

FGFR2IIIb (reverse), 5′-AGGCAGACTGGTTGGCCTG-3′

FGFR2IIIc (forward), 5′-AACGGTCACCACACCGGC-3′

FGFR2IIIc (reverse), 5′-TGGCAGAACTGTCAAC-3′

FGFR1 (forward), 5′-TGGGAGCATTAACCACACCTACC-3′

FGFR1 (reverse), 5′-CCTGCCCGAAGCAGCCCTCGCC-3′

Vimentin (forward), 5′-ATTTTGCCCTTGAAGCTGCTAAC-3′

Vimentin (reverse), 5′-TCAACCAGAGGAAGTGACTCCAG-3′

Pdx-1 (forward), 5′-CTCGCTGGGAACGCTGGAACA-3′

Pdx-1 (reverse), 5′-GCTTTGGTGGATTTCATCCACGG-3′.

Thirty amplification cycles were performed. Each cycle consisted of denaturation for 30 s at 96°C; annealing for 30 s at 56°C for cyclophilin, FGFR4, FGFR2IIIc, FGFR1, vimentin, and Pdx-1 and at 65°C for FGFR2IIIb; and extension for 30 s at 72°C. The resulting fragments were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gel and photographed.

Immunohistochemistry.

Pancreatic rudiments were fixed for 1 h in 3.7% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Four-micrometer-thick sections were collected and analyzed by immunohistochemistry, as described elsewhere (12, 16, 17). The antisera were used in the following dilutions: mouse anti-human insulin (Sigma), 1/2,500; mouse anti-human glucagon (Sigma), 1/2,000; rabbit anti-insulin (Diasorin Incstar, Antony, France), 1/2,000; rabbit antiglucagon (Diasorin), 1/2,000; rabbit anticarboxypeptidase A (Biogenesis, Bournemouth, U.K.), 1/600; mouse anti-human pancytokeratin (Sigma), 1/100; mouse antiporcine vimentin (Dako clone V9), 1/50; and mouse anti-BrdUrd (Amersham Pharmacia), 1/4. The fluorescent secondary antibodies were FITC anti-rabbit antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch), 1/200, and Texas red anti-mouse antibodies (The Jackson Laboratory), 1/200. Photographs of all of the sections were taken using a DMRB microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

In some experiments, adjacent sections were stained for endocrine and mesenchyme markers (insulin/glucagon and vimentin, respectively) and for acinar and epithelial markers (carboxypeptidase-A and cytokeratin, respectively). False colors were generated by using red green blue (RGB) layers in PHOTOSHOP 5.5 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA), and the images from adjacent sections were overlain by using the merge option in openlab 2.2.5r1 (Improvision, Coventry, U.K.).

For double-labeling immunofluorescence, antibodies raised in different species were applied to the sections and revealed by using antispecies antibodies labeled with two different fluorochromes. Single-labeled sections incubated with mismatched secondary antibodies showed no immunostaining, confirming the specificity of the secondary antisera.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis.

For each pancreatic epithelium, all sections (between 50 and 120 per rudiment) were stained with antibodies and were digitized by using a Hamamatsu (Hamamatsu City, Japan) C5810 cooled tri-charge-coupled device camera. All images were taken at the same magnification. On each image, the surface areas of the various stains were quantified by using iplab (Ver. 3.2.4, Scanalytics, Billerica, MA). For each stain, the surface areas per section were summed to obtain the total surface area per rudiment. When a section was missing (less than 2% of the total section number), we took the mean value of the staining in the adjacent sections into account. To quantify total rudiment volume, the surface areas of all of the sections from that rudiment were measured and summed, and the result was multiplied by the section thickness (4 μm). Any cavities in the tissue were subtracted from this volume. Results are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed by using statview 5 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Because we could not assume that the data were binomial, we used the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test to compare groups.

Results

Effect of the MAP Kinase Signaling Pathway Inhibitor PD98059 on Endocrine Cell Differentiation.

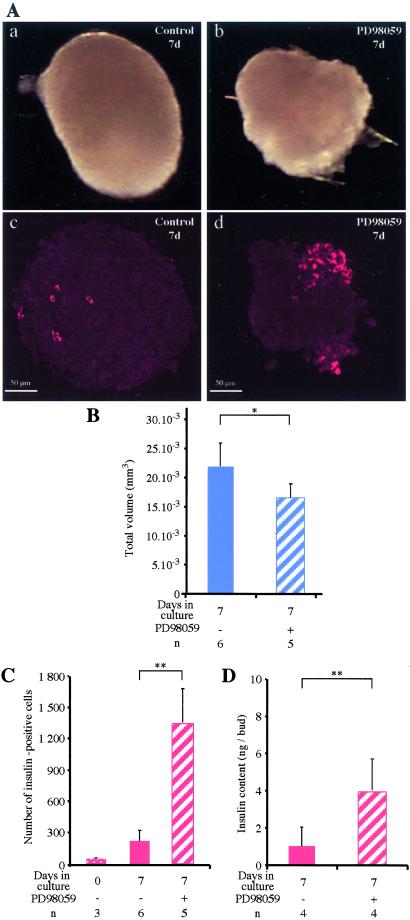

We investigated whether the effects of the mesenchyme on epithelial cell development depended on the MAP kinase pathway. Embryonic pancreatic rudiments (epithelium and mesenchyme) were cultured for 7 days with or without PD98059, a selective inhibitor of the MAP kinase pathway. Rudiments grown with PD98059 had a 25% smaller volume than controls cultured for the same duration (Fig. 1 A and B) (P < 0.05) but contained more insulin-expressing cells (P < 0.01; Fig. 1 A and C). Similarly, immunoreactive insulin content results showed that rudiments grown with PD98059 contained 3.5 times more insulin than those grown without PD98059 (P < 0.01; Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

In vitro effects of PD98059 on the development of rat embryonic pancreas. Pancreases (epithelium + mesenchyme) at E13.5 were grown for 7 days with PD98059 [50 μM diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] or with the same volume of DMSO (control), photographed (A a and b) and cut into sections, all of which were stained for insulin (red stain, A c and d). The volumes of the pancreases grown with or without PD98059 were measured (B), and the absolute number of insulin-expressing cells before or after culturing with or without PD98059 was determined (C). Insulin was extracted from the pancreases and assayed (D). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. n, number of samples analyzed.

Expression of FGFR2IIIb by the Embryonic Pancreatic Epithelium.

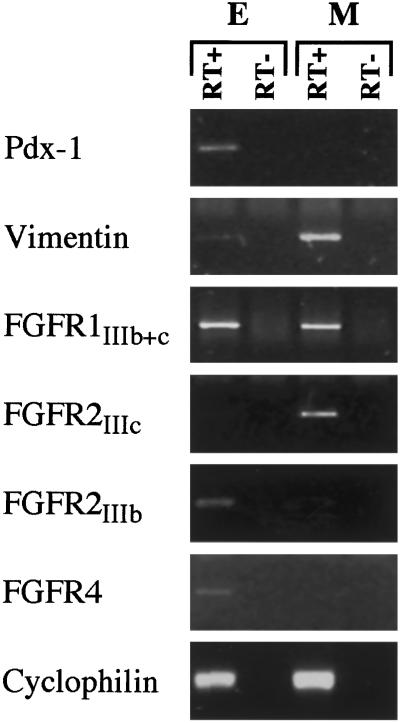

We defined the pattern of expression of FGFRs in E13.5 pancreases by using RT-PCR on cDNAs prepared from fractions enriched in epithelial or mesenchymal cells. Relative purity of the epithelial and mesenchymal pancreatic fractions was assessed by using RT-PCR for Pdx-1 and vimentin, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2, FGFR1 was found in both mesenchymal and epithelial fractions. FGFR2IIIc was detected only in the mesenchymal fraction, whereas FGFR2IIIb and FGFR4 were found only in the epithelial fraction.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR analysis of FGFRs using RNA from fractions enriched in epithelium (E) or mesenchyme (M). Pdx-1 and vimentin were used as markers of the epithelial and mesenchymal components, respectively. Cyclophilin was used to control the quality and quantities of the cDNAs. RT+ and RT−, reverse transcription with or without reverse transcriptase. Identical results were obtained when cyclophilin was coamplified with the various genes of interest.

Effect of Signals Transduced via FGFR2IIIb on Epithelial Cell Development.

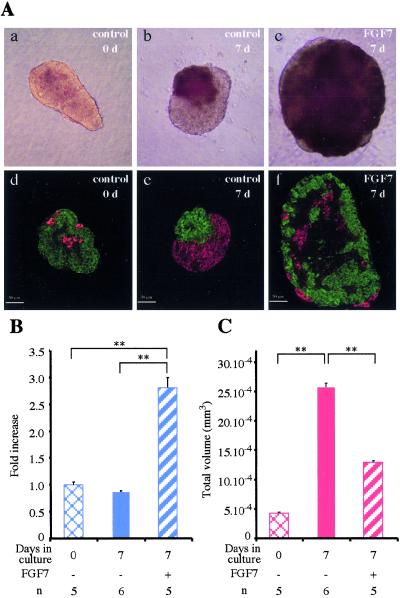

Pancreatic rudiments (containing epithelium and mesenchyme) were cultured with recombinant protein corresponding to the extracellular-ligand-binding domain of FGFR2IIIb, which blocks signals transduced via FGFR2IIIb. At the end of the culture, the absolute number of endocrine cells was 1.75 times higher than in control rudiments cultured with the same amount of BSA (P < 0.05). Thus, blocking signals transduced via FGFR2IIIb mimicked the positive effects of PD98059 on endocrine cell development. Gain-of-function experiments were next performed. When E13.5 pancreatic epithelium depleted of its surrounding mesenchyme was grown in vitro for 7 days, no major volume changes occurred without FGF7, whereas volume increased with FGF7 (P < 0.01; Fig. 3 A and B). At the end of the 7 days, the volume of rudiments grown with FGF7, 50 ng/ml, was increased 2.8-fold as compared with rudiments grown without FGF7 (P < 0.01). This increase in volume was paralleled by an increase in the number of cells that incorporated BrdUrd in the presence of FGF7 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

In vitro effects of FGF7 on the development of rat embryo pancreatic epithelium. Pancreatic epithelia at E13.5 were dissected and cultured for 7 days with or without FGF7 (50 ng/ml). Before culturing and at the end of the culture period, the epithelia were photographed (A a–c) and sectioned. All sections were stained for endocrine markers (insulin + glucagon, in red) or acinar markers (carboxypeptidase-A, in green) (A d–f). (B) Quantification of epithelium volume before and after culturing with or without FGF7. (C) Quantification of the absolute volume occupied by the endocrine cells under the various conditions. **, P < 0.01. n, number of samples analyzed.

We examined the effect of FGF7 on cell differentiation. When rudiments were cultured for 7 days without FGF7, the absolute volume occupied by endocrine cells increased 6-fold, as compared with 3-fold only with FGF7 (Fig. 3 A and C). After 7 days, the absolute volume occupied by acinar cells was 3 times greater in epithelia grown for 7 days with FGF7 than in epithelia grown without FGF7.

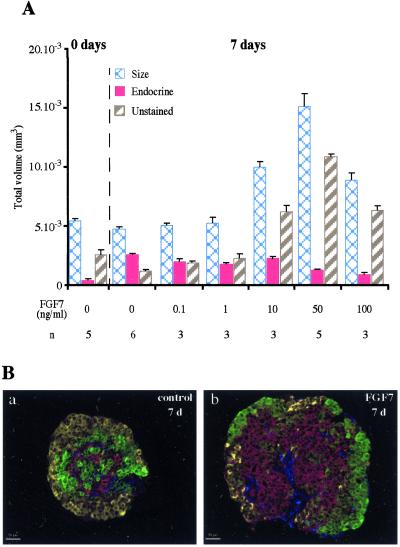

More importantly, when double immunohistochemistry for endocrine (insulin and glucagon) and acinar markers (carboxypeptidase-A) was performed, the vast majority of cells in rudiments exposed to FGF7 were negative for endocrine and acinar markers (Fig. 3A, compare e and f), whereas the opposite occurred without FGF7. Quantification showed a 9-fold increase in the number of cells negative for endocrine/acinar markers after 7 days of culture with 50 ng/ml of FGF7 than after 7 days without FGF7 (P < 0.01). These effects of FGF7 were dose-dependent, the maximum effect being obtained with 50 ng/ml of FGF7 (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

FGF7 increased the absolute volume occupied by cells that stained negative for endocrine and acinar markers but positive for cytokeratin. (A) Dose-dependent effect of FGF7 on volume of the epithelium, absolute volume occupied by endocrine cells, and absolute surface area occupied by cells that stained negative for endocrine and acinar markers. (B) The cells that stained negative for insulin + glucagon (yellow), carboxypeptidase-A (in green), and vimentin (in blue) stained positive for cytokeratin (in red). These cells were present in increased numbers in epithelia grown with FGF7 at 50 ng/ml (b) as compared with epithelia grown without FGF7 (a) (see A for quantification). n, number of samples analyzed.

To characterize the cells negative for endocrine/acinar markers, immunohistochemistry was performed on rudiments grown with or without FGF7 for 7 days. As shown in Fig. 4B, the vast majority of the cells negative for endocrine/acinar markers stained positive for cytokeratins. Cytokeratin-expressing cells were also detected in rudiments grown without FGF7, but their numbers were extremely small. Among cells negative for endocrine/acinar markers, few were positive for vimentin; these cells corresponded to the few fibroblasts that remain attached to the epithelium. Their numbers were similar in epithelial rudiments grown with and without FGF7.

Taken together, these results indicate that activation of FGFR2IIIb in the embryonic pancreatic epithelium induces cell proliferation and represses endocrine cell differentiation.

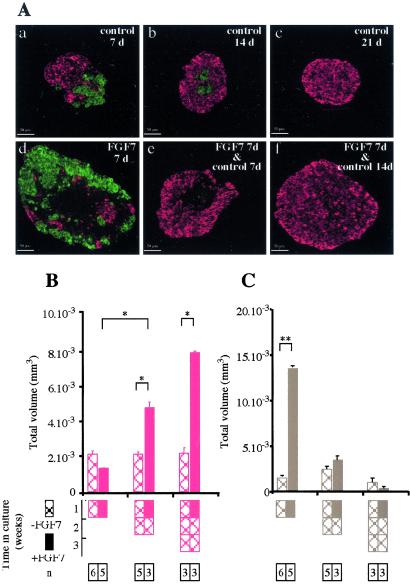

The Cytokeratin-Expressing Cells That Develop in the Presence of FGF7 Are Endocrine Progenitor Cells.

To determine whether the cytokeratin-expressing cells that proliferated in response to FGF7 were endocrine progenitor cells, we tested their ability to differentiate into endocrine cells on FGF7 removal. Epithelial rudiments were cultured for 7 days with or without FGF7. Then, the cultures were either stopped or continued for 1 or 2 weeks without FGF7. On removal of FGF7, endocrine cell development occurred en masse (Fig. 5 A and B), and the absolute volume occupied by cells negative for endocrine/acinar markers decreased (Fig. 5C), strongly suggesting that these negative cells differentiated into endocrine cells. Conversely, prolonging the culture for 1 or 2 weeks after a first week without FGF7 did not increase the amount of endocrine cells (Fig. 5). Note that, as previously shown (18), in vitro the acinar tissue degenerates when cultured for long periods. The vast majority of endocrine cells that developed from cytokeratin-expressing cells previously expanded with FGF7 were insulin-expressing cells (95%); only 5% expressed glucagon (not shown). The rudiments grown under these conditions had high insulin contents (926 ± 171 per rudiment; n = 4). Finally, these β cells released insulin in response to glucose; the rate of insulin release per rudiment and per hour was 0.79 ± 0.33 ng with 1.67 mM glucose and 10.93 ± 3.77 ng with 16.7 mM glucose (n = 4).

Figure 5.

Cells that stained negative for endocrine and acinar markers differentiated into endocrine cells on FGF7 removal. (A) E13.5 rat epithelia were grown for 7 days with (d–f) or without (a–c) FGF7. Cultures were either stopped (a, d) or continued for 1 (b, e) or 2 (c, f) weeks without FGF7. The epithelia were sectioned and stained for insulin + glucagon (in red) and carboxypeptidase-A (in green). (B) Quantification of the absolute volume occupied by the endocrine cells. (C) Quantification of the absolute volume occupied by cells that stained negative for endocrine and acinar markers. Hatched bars, no FGF7 during the culture period. Solid bars, FGF7 was present during the first week of culture. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

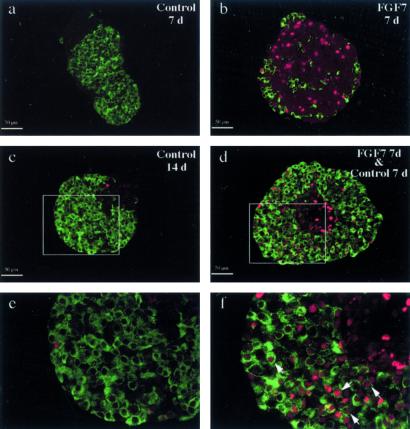

To obtain further evidence that the cells showing a proliferative response to FGF7 were the ones that differentiated into endocrine cells on FGF7 removal, we performed lineage experiments using BrdUrd as a tracer. When epithelial rudiments were grown for 7 days with or without FGF7 and pulsed for 1 h with BrdUrd, a very small number of cells positive for BrdUrd were detected on day 7 in epithelial rudiments grown without FGF7. In contrast, in rudiments cultured with FGF7, a large number of cells negative for endocrine markers incorporated BrdUrd (Fig. 6, compare a and b). When epithelia grown for 1 week with FGF7 were cultured for an additional week without FGF7, the newly formed endocrine cells were positive for BrdUrd (Fig. 6 d and f), indicating that they derived from epithelial cells that proliferated when exposed to FGF7.

Figure 6.

Endocrine cells differentiated from cells that proliferated in response to FGF7 exposure. E13.5 rat pancreatic epithelia were grown for 7 days with (b, d, f) or without (a, c, e) FGF7, then pulsed for 1 h with BrdUrd. Cultures were either stopped (a, b) or continued for 1 week without FGF7 (c–f). The epithelia were sectioned and stained for insulin + glucagon (in green) and BrdUrd (in red). e and f are enlargements of c and d, respectively. Arrowheads indicate cells that stained positive for both BrdUrd and endocrine hormones.

Discussion

The present work demonstrates that FGFR2IIIb is expressed in the pancreatic embryonic epithelium. Signals mediated by this receptor control epithelial development by activating the proliferation of epithelial cells and repressing their differentiation into endocrine cells, thereby amplifying the pool of endocrine precursor cells.

The endocrine cells of the pancreas develop from as-yet-uncharacterized progenitor cells that are located within the pancreatic epithelium. It was suggested more than 20 years ago that proliferation and differentiation of these progenitor cells may occur only in response to signals from the surrounding mesenchyme (19). The finding by Gittes et al. that embryonic pancreatic epithelium can differentiate in the absence of mesenchyme cast doubt on this hypothesis (20). More recently, it was shown not only that endocrine tissue could develop in the absence of mesenchyme, but also that the mesenchyme had a repressive effect on endocrine development (12). However, the exact nature of the mesenchymal signals acting on the epithelium to activate epithelial cell proliferation and to repress cell differentiation remains unknown. We demonstrate in the present study that a functional MAP kinase pathway is important for epithelium–mesenchyme interactions: the effect of the mesenchyme on epithelial development was altered in the presence of PD98059, which inhibits the MAP kinase-signaling pathway. This result strongly suggests that signals transduced by tyrosine kinase receptors may be implicated in the development of the pancreatic epithelium. Next, we demonstrated that the effects of the mesenchyme were mimicked by signals mediated by FGFR2IIIb, which is expressed in the embryonic pancreatic epithelium. These data were obtained in an in vitro model of rat pancreatic epithelium harvested on E13.5 and dissected free of its surrounding mesenchyme. In this in vitro system, epithelial cell proliferation is low in the absence of exogenous growth factors. In addition, epithelial cells differentiate mainly into endocrine cells, indicating that the development of pancreatic endocrine cells occurs via a default pathway (12, 20). On the other hand, in the presence of mesenchyme, epithelial cell growth occurs, acinar tissue develops, and endocrine differentiation is repressed (12). We found in the present study that FGF7 mimicked the effects of the mesenchyme at E13.5: epithelial cell proliferation and acinar development increased, whereas endocrine cell development decreased. We had previously demonstrated that earlier during development (E11), FGF7 mimicked the effects of the mesenchyme on epithelial cell proliferation and acinar cell differentiation. However, at this earlier stage, FGF7 repressed the relative concentration of endocrine cells but had no major repressive effect on the absolute amount of endocrine tissue (10). Thus the effect of FGFR2IIIb ligands on endocrine tissue development seems to vary with the developmental stage of the pancreas.

Several arguments from earlier studies indicate that in vivo, signals transduced via FGFR2IIIb are involved in controlling the development of the pancreatic epithelium. First, various FGFR2IIIb ligands, such as FGF1, FGF7, and FGF10, are expressed in the developing pancreas (10, 21, 22). In other organs, such as the lung (23), the epithelial component is known to develop under the control of signals from the surrounding mesenchyme. Similarly, FGFR2IIIb ligands are mainly produced by the mesenchymal cells in the pancreas (22) and are bound by FGFR2IIIb expressed by the epithelial component (22, 24). Second, pancreatic dysgenesis occurs in mice that express a dominant-negative form of FGFR2IIIb or no FGFR2IIIb at all (7, 8). However, pancreatic dysgenesis occurred only when expression of the dominant-negative form of FRFR2IIIb was controlled by the metallothionein promoter, which allows ubiquitous transcription of the transgene in mouse embryos (7). When the same dominant-negative transgene was driven by the tissue-specific Pdx-1 promoter and therefore was expressed only in the pancreatic epithelium, pancreatic development was not altered (9). Thus, it was unknown whether FGFR2IIIb ligands acted directly on pancreatic development or whether FGFR2IIIb induced as-yet-unidentified cells to send signals capable of controlling pancreatic epithelial cell development. The data obtained here by using cultured pancreatic epithelium from E13.5 embryos demonstrate that the effects are direct.

In addition to its positive effect on epithelial cell proliferation and its repressive effect on endocrine cell development, FGF7 activated the proliferation of undifferentiated epithelial cells that were endocrine progenitor cells. FGF7 induced the production of numerous cytokeratin-expressing cells that stained negative for endocrine and acinar markers. When FGF7 was removed, these undifferentiated epithelial cells differentiated into endocrine cells. This result indicates that FGFR2IIIb ligands could be used to expand pancreatic endocrine progenitor cells. FGF2 has been used successfully to expand progenitor cells present in various regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus, forebrain, or striatum (25–29). FGF2 acts mainly via the IIIc isoforms of FGFR1, 2, and 3, which are expressed by progenitor cells in the brain (30). In the pancreas, the IIIc isoform of FGFR2 is found only in the mesenchymal fraction (present study), whereas the epithelial cells express the IIIb isoform of FGFR2 (22). That endocrine progenitor cells can be expanded by using FGF7, a compound that binds only to FGFR2IIIb (11), strongly suggests that this receptor may be a marker for pancreatic progenitor cells.

Information is now available on the characterization, expansion, and differentiation induction of stem cells present in various tissues, including hematopoietic cells (31). Markers that can be used to isolate stem cells from the peripheral and central nervous system have been identified (32, 33), and conditions in which these stem cells can be made to expand and differentiate have been defined (34). These new data open a wide door toward future treatment of degenerative diseases with stem cells present in specific tissues (35). Type 1 diabetes is a metabolic disease caused by destruction of the pancreatic β cells, which are the insulin-producing cells. Conditions that activate the proliferation and differentiation of stem/progenitor cells present in the central nervous system have been identified (36). Studies aimed at achieving the same goal for pancreatic stem/progenitor cells have been hampered by the lack of specific markers for these cells. We demonstrate here that FGF7 increases the number of endocrine progenitor cells within the pancreatic epithelium. Comparisons of pancreatic epithelia grown with and without FGF7—i.e., containing large or small numbers of progenitor cells, respectively—should permit the identification of markers for pancreatic progenitor cells, as recently done for the central nervous system (37). These markers could be used to purify the progenitor cells.

Acknowledgments

I. Le Nin is acknowledged for technical assistance. L.E. and C.C.-M. were recipients of fellowships from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale and the Fondation de France, respectively. This work was supported by grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International, the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC), and the Association Française des Diabétiques.

Abbreviations

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR

FGF receptor

- MAP

mitogen-activated protein

- En

embryonic day n

- RT

reverse transcription

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Hogan B L. Cell. 1999;96:225–233. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80562-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golosow N, Grobstein C. Dev Biol. 1962;4:242–255. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(62)90042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallman F, Grobstein C. J Cell Biol. 1968;20:399–413. doi: 10.1083/jcb.20.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pictet R, Rutter W. In: Handbook in Physiology: The Endocrine Pancreas. Steiner D, Freinkel N, editors. Vol. 1. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1972. pp. 25–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slack J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1995;121:1569–1580. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson D, Williams L. Adv Cancer Res. 1993;60:1–41. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celli G, LaRochelle W, Mackem S, Sharp R, Merlino G. EMBO J. 1998;17:1642–1655. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Revest J M, Spencer-Dene B, Kerr K, De Moerlooze L, Rosewell I, Dickson C. Dev Biol. 2001;231:47–62. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart A W, Baeza N, Apelqvist A, Edlund H. Nature (London) 2000;408:864–868. doi: 10.1038/35048589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miralles F, Czernichow P, Ozaki K, Itoh N, Scharfmann R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6267–6272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ornitz D, Xu J, Colvin J, McEwen D, McArthur C, Coulier F, Gao G, Goldfarb M. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15292–15297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miralles F, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:1017–1024. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miralles F, Serup P, Cluzeaud F, Vandewalle A, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R. Dev Dyn. 1999;214:116–126. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199902)214:2<116::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atouf F, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1929–1934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miralles F, Battelino T, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:827–836. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cras-Meneur C, Elghazi L, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R. Diabetes. 2001;50:1571–1579. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.7.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanvito F, Herrera P, Huarte J, Nichols A, Montesano R, Orci L, Vassali J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1994;120:3451–3462. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wessels N, Cohen J. Dev Biol. 1967;15:237–270. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(67)90042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gittes G, Galante P, Hanahan D, Rutter W, Debas H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:439–447. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.2.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason I, Fuller-Pace F, Smith R, Dickson C. Mech Dev. 1994;45:15–30. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finch P, Cunha G, Rubin J, Wong J, Ron D. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:223–240. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellusci S, Grindley J, Emoto H, Itoh N, Hogan B L. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:4867–4878. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orr-Urtreger A, Bedford M, Burakowa T, Arman E, Zimmer Y, Yayon A, Givol D, Lonai P. Dev Biol. 1993;158:475–486. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vicario-Abejon C, Johe K K, Hazel T G, Collazo D, McKay R D. Neuron. 1995;15:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciccolini F, Svendsen C N. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7869–7880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07869.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tropepe V, Sibilia M, Ciruna B G, Rossant J, Wagner E F, van der Kooy D. Dev Biol. 1999;208:166–188. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gritti A, Frolichsthal-Schoeller P, Galli R, Parati E A, Cova L, Pagano S F, Bjornson C R, Vescovi A L. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3287–3297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03287.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martens D J, Tropepe V, van Der Kooy D. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1085–1095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01085.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian X, Davis A A, Goderie S K, Temple S. Neuron. 1997;18:81–93. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weissman I L. Cell. 2000;100:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrison S J, White P M, Zock C, Anderson D J. Cell. 1999;96:737–749. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80583-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uchida N, Buck D W, He D, Reitsma M J, Masek M, Phan T V, Tsukamoto A S, Gage F H, Weissman I L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14720–14725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss S, Reynolds B A, Vescovi A L, Morshead C, Craig C G, van der Kooy D. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:387–393. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weissman I L. Science. 2000;287:1442–1446. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKay R. Science. 1997;276:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geschwind D H, Ou J, Easterday M C, Dougherty J D, Jackson R L, Chen Z, Antoine H, Terskikh A, Weissman I L, Nelson S F, Kornblum H I. Neuron. 2001;29:325–339. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]