Short abstract

Doctors in the United Kingdom can accompany their patients every step of the way, up until the last. The law stops them helping their patients take the final step, even if that is the patient's fervent wish. Next month's debate in the House of Lords could begin the process of changing the law. To help doctors decide where they stand we publish a range of opinions

Two widely publicised medicolegal cases in the United Kingdom1,2 have prompted renewed debate about the moral and legal validity of providing assistance to die (box 1).3 The debate has been fuelled by publication of the report of a House of Lords select committee set up to consider the Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill4 and final determination by the US courts that hydration and nutrition could lawfully be withdrawn from a patient in a persistent vegetative state.5,6

Proposed legislation

The UK bill provides for a competent adult who has resided in Great Britain for at least one year and is suffering unbearably as a result of a terminal illness to receive medical assistance to die at his or her considered and persistent request (box 2). The bill also incorporates various qualifying conditions and safe-guards to protect the interests of patients and clinicians.

The proposed change should be supported as a matter of both principle and practicality. As a matter of principle, it reinforces current trends towards greater respect for personal autonomy.7 It also provides a logical extension to the well established principle in English law that competent adults are entitled to withhold or withdraw consent to life sustaining treatment.8 Some people would argue that because assisted dying introduces new intervention—the drug used with specific intent to procure death—it is different from allowing death by withholding or withdrawing life sustaining treatment. But if life sustaining treatment such as mechanical ventilation is withdrawn, whether at the patient's request or because it is deemed futile, death is a virtually certain consequence and doctors are aware of this when they act. In other words, their action fulfils the legal criteria for indirect intent.9 The motive may be benevolent but the intention is to kill or to permit a preventable death.

In practical terms, legislation to permit assisted dying responds to the predicament of the minority of terminally ill patients whose suffering cannot be relieved by even the best palliative care and who wish to end their lives but cannot do so by refusing life sustaining treatment. Examples include people with progressive paralysing illness that compromises respiration, speech, and swallowing but preserves sensation and mentation, as well as those for whom loss of autonomy, dignity, and quality of life are of paramount importance.10

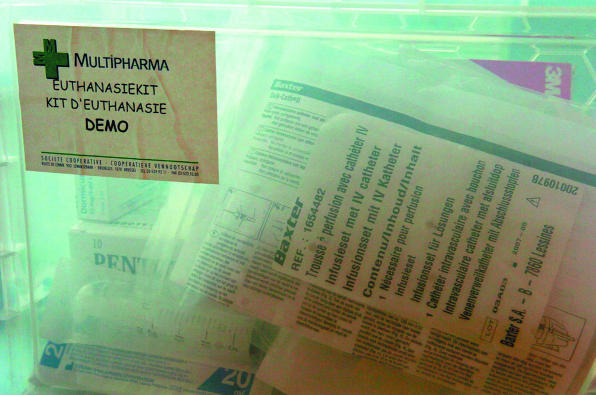

Figure 1.

Credit: ETIENNE ANSOTTE/SFP/GETTY

Kits are available for Belgian general practitioners who want to help patients to die at home

But creating rights or allowing indulgence of personal preference is open to challenge if it produces a corresponding risk to society as a whole or to specific and possibly vulnerable sections within it. Similar conflict is apparent in debates about restricting the personal liberty of people with mental illness or suspected of terrorism. Society, through its democratic processes, should be the arbiter.

Box 1: End of life decisions: two legal cases

Case 1—A 42 year old woman who was profoundly disabled by motor neurone disease sought a declaration that her husband would not be prosecuted if he assisted her to die when she considered her life intolerable. Founded on the Human Rights Act 1998, the application failed at all levels in the English courts and in the European Court of Human1 Rights.

Case 2—A 44 year old woman had a haemorrhage from a vascular anomaly in the cervical cord resulting in tetraplegia and dependence on a ventilator. She successfully sought a ruling that mechanical ventilation be withdrawn. She was deemed fully competent and, because treatment had already been continued without her consent for some months, she was also awarded damages.2

Box 2: Definitions in UK bill on assisted dying

Medical assistance to die—Providing the patient with the means to end life (physician assisted suicide) or ending that life if the patient is physically unable to do so (voluntary euthanasia).

Terminal illness—One that the consulting physician considers to be inevitably progressive, likely to result in death within a few months, and with effects that cannot be reversed by treatment even though symptoms may be relieved.

Unbearable suffering is defined subjectively.

Public opinion

Successive National Opinion Poll surveys show growing public support for legislation to permit assisted dying. The percentage in favour rose from 69% in 1976 to 82% in 2004, with a YouGov survey in 2004 indicating a similar proportion (80%) among disabled people.11 Although these surveys have been criticised as too simplistic,11 the progressive rise in the proportion of positive respondents strongly suggests that public opinion is increasingly in favour of change.

This conclusion is endorsed by public response to judicial opinion in cases of mercy killing which reach the courts.12 The sentence is often lenient, even when a conviction has been secured, and yet there is no public outcry that punishment has been inadequate. This contrasts with feelings expressed if the courts are perceived to be unduly lenient to convicted rapists or child molesters.

Finally, there is tacit acceptance that patients who cannot obtain help in the UK may travel to Switzerland, where assisted suicide can be obtained commercially and legally. Relatives or friends facilitating such journeys run the risk of prosecution for offences contrary to section 2 the Suicide Act 1961 (to aid, abet, counsel, or procure the suicide of another),13 but although some have been criminally investigated, no prosecutions have been brought.

Professional opinion

In 1994, formal representations offered by professional bodies to an earlier House of Lords select committee opposed a change in the law.14 In evidence to the 2004 select committee, the General Medical Council, Royal College of Physicians on behalf of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, and the Royal College of General Practitioners all adopted a neutral stance, but the British Medical Association and Royal College of Nursing maintained their opposition.15 However, BMA representatives at the 2005 annual meeting voted in favour of a neutral stance,16 and a survey of nurse practitioners also suggests a contrary view among members.17

Experience in other jurisdictions

Assisted dying has been legalised by statute in several jurisdictions including the Netherlands, Belgium, and the US State of Oregon. Oregon's Death with Dignity Act is most comparable with the UK bill because both apply only to terminally ill competent adults seeking assistance voluntarily. The Oregon Act, reaffirmed by voters in 1997, requires publication of an annual report based on information supplied mandatorily by doctors and pharmacies.18 The annual number of prescriptions for lethal medication (a barbiturate) has tended to rise, but the number of deaths resulting from its ingestion has changed little in the past three years (table). Physician assisted suicide has accounted for between 0.06% and 0.14% of total deaths. In 2004, all but one of the assisted deaths took place at home, the other being at a facility for assisted living. All those who obtained assisted dying had some form of health insurance and 89% were enrolled in hospice care. In general these patients were younger, more highly educated, and expressed more than one reason for choosing an assisted death. The most common reasons were a decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable, loss of autonomy, and loss of dignity. Assisted dying was proportionately more common in patients with motor neurone disease, AIDS, or malignant neoplasms than among those dying from other debilitating conditions.

Table 1.

Lethal prescriptions issued and assisted suicide under Oregon's Death with Dignity Act

| 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of prescriptions | 24 | 33 | 39 | 44 | 58 | 67 | 60 |

| No of assisted deaths | 16 | 27 | 27 | 21 | 38 | 42 | 37 |

The population of Oregon is about three million, and if similar experience followed enabling legislation in the UK about 650 assisted deaths might be expected annually.4 The Oregon experience also suggests more people might request assistance than use it, perhaps because the availability of a prescription is perceived as an insurance policy.

The data from Oregon also answer some of the concerns expressed by opponents of the proposed legislation. The fact that those choosing an assisted death are younger, more highly educated, and accustomed to being in control of their lives detracts from the contention that permissive legislation will pressurise elderly or vulnerable patients into seeking death for the perceived benefit of others. Both the Oregon legislation and Lord Joffe's bill emphasise the need for mental competence as a precondition. The applicant must also be acting voluntarily, and so the intent to die must defeat the universal animal instinct for self preservation.

Select committee report

Although the assisted dying bill ran out of time in the last parliament, the select committee reported on the evidence accumulated and offered recommendations about how the matter should be pursued in future. It drew attention to the following five concerns:

The demand for assistance to die is particularly strong among determined people whose suffering derives more from the fact that they are terminally ill than from the symptoms; such people are unlikely to be deflected from their wish to end their lives by the availability of more or better palliative care

The distinction between assisted suicide and euthanasia is important because the take-up of assisted dying is lower in jurisdictions where legislation is limited to assisting suicide than in those where euthanasia is also permitted

Procedural requirements need clarifying, in particular the steps a doctor should take after a patient has passed the qualifying tests

Terms such as terminal illness, mental competence, and unbearable suffering need to be defined more precisely. Any definition of terminal illness should reflect the realities of clinical practice as regards prognosis. Account should be taken of the need clearly to identify psychological or psychiatric disorder as part of any assessment of mental competence, and consideration should be given to including a test of unrelievable rather than unbearable suffering or distress

Those seeking an assisted death need to experience good palliative care rather than simply be informed of its existence if the two approaches to management at the end of life are to be regarded as complementary.

Conclusion

A small but determined group of patients with terminal illness seek to end their lives at a time of their own choosing. At present they must act alone and without assistance or travel overseas to fulfil their objective. Alternatively they expose family, friends, or doctors to an ill defined risk of criminal prosecution. A change in legislation is needed to regularise this situation and to ensure such patients are given respect for autonomy comparable with that of patients who can already influence the manner and timing of their death by withholding or withdrawing consent to life sustaining treatment.

Summary points

English law endorses the right of competent adults to withhold or withdraw consent even to life sustaining medical treatment

A few determined terminally ill patients seek assistance to die but this is illegal

Even the best palliative care is unable to alleviate the distress of some patients

Terminally ill patients seeking assistance to die should be given the same respect for self determination as those who can end their lives

Contributors and sources: MAB was a consultant physician and anaesthetist at the Royal Brompton Hospital, London with responsibility for adult intensive care, the medical high dependency unit, and domiciliary mechanical ventilation. She is a member and former chairman of the Voluntary Euthanasia Society. Information has been sourced primarily from professional journals and reports by public bodies.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Application 2346/02: R v Director of Public Prosecutions ex parte Pretty and Secretary of State for the Home Department ( 2002) 35 ECHR 1.

- 2.Ms B v An NHS Hospital Trust [ 2002]. Lloyd's Law Reports: Medical 265.

- 3.Doyal L, Doyal L. Why active euthanasia and physician assisted suicide should be legalised. BMJ 2001;323: 1079-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.House of Lords Select Committee on the Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill [HL]. Report on the assisted dying for the terminally ill bill. London: Stationery Office, 2005. www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld/ldasdy.htm (accessed 12 Sep 2005).

- 5.Grayling AC. Right to die. BMJ 2005;330: 799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Twisselmann B. “Right to die”: summary of responses. BMJ 2005;330: 1389. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kravitz RL, Melnikow J. Engaging patients in medical decision-making. BMJ 2001;323: 584-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Re T. (Adult, refusal of treatment) [ 1992] 3 Medical Law Reports 306.

- 9.R v Woollin [ 1999] AC 82.

- 10.Smith R. A good death. BMJ 2000;320: 129-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.House of Lords Select Committee on the Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill [HL]. Report on the assisted dying for the terminally ill bill. Vol I: appendix 7. London: Stationery Office, 2005.

- 12.Huxtable R. Assisted suicide. BMJ 2004;328: 1088-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ReZ, a local authority v Mr Z and the official solicitor. [ 2004] EWHC 2817 (Fam).

- 14.House of Lords Report. Select committee on medical ethics. London: Stationery Office, 1994.

- 15.House of Lords Select Committee on the Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill [HL]. Report on the assisted dying for the terminally ill bill. Vol 2. London: Stationery Office, 2005. www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld/ldasdy.htm (accessed 12 Sep 2005).

- 16.BMA drops its opposition to doctor-assisted dying. Times 2005. Jul 1. [PubMed]

- 17.Hemming P. Dying wishes. Nursing Times 2003;99: 20-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oregon Department of Human Services. Seventh annual report on Oregon's death with dignity act, March 2005. http://egov.oregon.gov/DHS/ph/pas/docs/year7.pdf (accessed 22 Jul 2005).