Abstract

Notch receptors undergo three distinct proteolytic cleavages during maturation and activation. The third cleavage occurs within the plasma membrane and results in the release and translocation of the intracellular domain into the nucleus to execute Notch signaling. This so-called γ-secretase cleavage is under the control of presenilins, but it is not known whether presenilins themselves carry out the cleavage or whether they act by means of yet-unidentified γ-secretase(s). In this article, we show that Notch intracellular cleavage in intact cells completely depends on presenilins. In contrast, partial purification of the Notch cleavage activity reveals an activity, which is present only in protein extracts from presenilin-containing cells, and which does not comigrate with presenilin. This finding provides evidence for the existence of a specific Notch-processing activity, which is physically distinct from presenilins. We conclude from these experiments that presenilins are critically required for Notch intracellular cleavage but are not themselves directly mediating the cleavage.

Keywords: secretase‖Alzheimer's disease‖neurodegenerative disease‖HES gene

The Notch signaling pathway is an evolutionarily conserved signaling system, which controls cell fate decisions (1). The Notch receptor is a single transmembrane spanning protein, and activation of the receptor involves at least three different proteolytic cleavage events (2). The two first cleavages occur at the extracellular side of the Notch receptor and are followed by a third cleavage, which takes place at the plasma membrane. This cleavage liberates the intracellular Notch receptor domain (Notch IC), which then is translocated to the nucleus to mediate signaling through activation of HES (Hairy/Enhancer of split) genes (3–6). The third proteolytic cleavage of the Notch receptor is linked to the function of presenilins, which also control the proteolytic processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) (for review see refs. 7 and 8). Presenilins are the most frequently mutated genes in familial Alzheimer's disease, and the mutations in presenilin affect APP processing.

A key question is whether presenilins contain the γ-secretase activity required for cleavage or whether they act indirectly by activating other intermediate proteins that execute the proteolytic cleavage of Notch and APP. Support for the notion that presenilins are identical to γ-secretase (see refs. 7–9 for review) comes from work with γ-secretase inhibitors (10–12) and active site-mutated presenilins (13). Furthermore, no detectable Aβ production from APP is observed in cells derived from mice in which both presenilin 1 (PS1) and presenilin 2 (PS2) have been inactivated by gene targeting (14–16).

The situation, however, becomes more complex if processing of Notch receptors is taken into account. Presenilins clearly play an important role in Notch processing, which was first discovered in Caenorhabditis elegans (17) and later in Drosophila and mice (16, 18–22). These data do not, however, reveal whether this processing is a direct or indirect effect of the presenilins. There are observations suggesting that the specificity of presenilin-controlled Notch and APP processing differ, which may indicate that presenilins are not solely responsible for the cleavage of both Notch and APP. Thus, Notch and APP are differently affected by certain γ-secretase inhibitors (24),§§ mutations in presenilin (13), or mutations at the cleavage sites of Notch and APP (25, 26). To address the role of presenilins for Notch processing, we here analyze whether presenilins directly cleave Notch or whether cleavage is mediated by a distinct protein activity.

Materials and Methods

DNA Constructs.

The detailed description of the cloning work is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Generation of Cell Lines, Transfections, and Reporter Gene Assay.

The detailed description of the generation and culture of the BD8 and BD3 cell lines is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Transfections were performed with the Lipofectamine Plus method (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) in 24-well tissue culture plates by using a total amount of 450 ng DNA consisting of: 200 ng UAS-luc, 100 ng Notch1 ΔEGVP or Notch3 ΔEGVP constructs, 50 ng CMV-βgal vector, and 0–100 ng additional vector (PS1 and PS2) with the remaining DNA made up to 450 ng with empty pCMX vector. Transfected cells were grown for 48 h followed by lysis. The lysate was used to determine luciferase activity as described (27). β-Galactosidase concentration was determined to equalize results for transfection efficiency. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated 3–6 times.

Western Blot.

The lysed cells (50% of total lysed cell extracts from above) were boiled in 1× SDS sample buffer + 5% β-mercaptoethanol and used for analysis by SDS/PAGE. Proteins transferred to nitrocellulose membranes were probed with the 9E10 myc mAb (PharMingen) or the VP16 polyclonal antibody (CLONTECH, no. 3844–1) and visualized by SuperSignal Western blot reagents (Pierce). Fuji Super RX x-ray film was used for exposure and scanned in AGFA Arcus II and reproduced for publication with Adobe photoshop.

Inhibitors.

MW167 inhibitor (Calbiochem) and Merck inhibitor L-685,458 and L-405,484 (generously provided by M. Shearman, Merck) were dissolved in DMSO. The inhibitors were added to the transiently transfected cell cultures 24 h posttransfection (final concentration 10 μM and 25 μM, respectively; DMSO at a final concentration of 1.25%) for 12 h of incubation. The cells were lysed and analyzed for luciferase/β-galactosidase activity.

Isolation of Membrane from the Cells.

All procedures were conducted at 4°C. Cells were grown confluent on 15-cm dishes and washed with ice-cold 1× PBS. Cells were harvested with cell scraper and collected in 50-ml tubes. After spinning down the cells, they were homogenized with a dounce homogenizer by using 15 strokes of B pestle in 9× volume of isotonic buffer (30 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4/0.25 M sucrose). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 7 min. The pellet containing nuclei and the large fragments of membrane were resuspended in 2.1 M sucrose. Sucrose solutions (1.25 M and 0.25 M) were overlaid. After the centrifugation with swing rotor at 75,000 g overnight (for 8–16 h), the membrane fraction was concentrated at the border between 1.25 M and 0.25 M sucrose layers, collected, diluted in 5× volume of 1 M NaCl, placed on ice for 15–20 min, and centrifuged again with an angled rotor at 75,000 g for 1 h. The pelleted membrane fraction was resuspended in stock solution (30 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4/20% glycerol), flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Solubilization and Fractionation of Membrane Protein.

The frozen membrane fraction was thawed rapidly. 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) was added to the final concentration of 0.25%. The membrane fraction was placed on ice for 15 min, and the insoluble materials were removed by centrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was dialyzed overnight against more than 100× volume of buffer containing 30 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM EDTA, 0.25% CHAPS, and 10% glycerol with a replacement of the buffer 3 h after the start of dialysis. The dialyzed proteins were applied to a 1-ml Hitrap Q column (Amersham Pharmacia) equilibrated with buffer A (30 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4/1 mM EDTA/0.25% CHAPS/10% glycerol) and eluted with 25 ml of linear NaCl gradient (0–0.5 M), and 1-ml fractions were collected.

Peptide Cleavage Assay.

Peptides were synthesized and purified by HPLC by Peptide Inc., Osaka. The following peptides were used for the assay: wild-type Notch peptide, Nma-GCGVLL-K (Dnp)rr-NH2, and mutant Notch peptide, Nma-GCGKLL-K(Dnp)rr-NH2. The peptide dissolved in DMSO was added to the final concentration of 8 μM to 50 μl of each protein fraction. After incubation at 37°C for 2 h, the reaction was terminated by placing samples on ice. The fluorescence was measured by using 1420 ARVO fluorometer (Amersham Pharmacia) with the excitation wavelength at 355 nm and the emission wavelength at 440 nm. Inhibitors were added to the fractionated protein samples and incubated on ice for 10 min before the addition of the peptide. For immunodepletion experiments, the fractionated proteins were precleared with Protein G Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia) at 4°C for 1 h. Subsequently, 5 μl of the preimmune serum, anti-PS1 antibody, G1L3, or anti-PS2 antibody, G2L (a kind gift from T. Iwatsubo, University of Tokyo, Tokyo) was added to each 50 μl of precleared samples and incubated at 4°C for 1 h, followed by incubation with Protein G Sepharose for an additional hour.

Results

A Sensitive Assay for Notch Intracellular Cleavage.

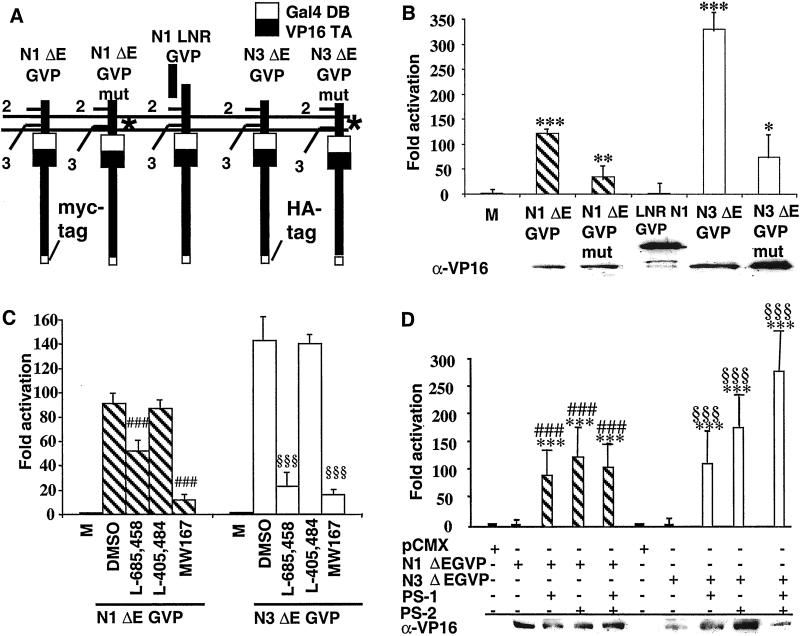

It has previously been shown that no production of Notch IC detectable by Western blot analysis takes place in presenilin-deficient cells (13, 16, 18). As biologically relevant Notch signaling may, however, occur at levels below the Western blot detection limit, we wanted to establish an alternative, more sensitive, and specific assay to measure Notch intracellular cleavage. The assay is based on the integration of the GAL4 DNA binding and VP16 transactivating protein domains (G4VP16) into the intracellular portion of the Notch ΔE protein, which mimics a site two-cleaved Notch receptor, to generate N ΔEGVP (Fig. 1A). After cleavage of the N ΔEGVP, the intracellular domain translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription from a UAS promoter element. The insertion of G4VP16 into a Notch receptor has previously been used in vivo in Drosophila to record Notch intracellular cleavage (4, 6, 20) and to measure cleavage at site 2 in Notch 1 (28). We generated Notch ΔE constructs containing G4VP16 from the Notch 1 and Notch 3 genes (N1 ΔEGVP and N3 ΔEGVP, respectively) (Fig. 1A), and 100 pg of each construct is sufficient to be detected by UAS/promoter activation in HEK293T cells, which are wild type for presenilin (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Analysis of Notch ΔEGVP constructs. (A) Schematic illustration of the different constructs used in the study. * denotes the site of mutation in the Notch (N) receptors (V1744G in N1 and GVM1662–1664AAA in N3). Gal4VP16 is denoted GVP. HA tag, hemagglutinin tag. (B) Analysis of the effects of mutations in the cleavage site 3 of N1 ΔEGVP and N3 ΔEGVP (compare N1 ΔEGVPmut versus N1 ΔEGVP and N3 ΔEGVPmut versus N3 ΔEGVP). A strong reduction of cleavage is observed with both mutants. The N1 LNR GVP protein, which lacks the EGF repeats at the extracellular side, is not processed at detectable levels. Below is shown a Western blot examining the expression levels of the different constructs. The experiment was repeated at least three times with triplicates in each assay. ***, P < 0 001; **, P <0.01; *, P < 0.05 vs. Mock. (C) Analysis of the effects of γ-secretase inhibitors on Notch processing. Cleavage of both N1 ΔEGVP and N3 ΔEGVP was reduced by the addition of L-685,458 and MW167, but not by DMSO and L-405,484, which is structurally related to L-685,458, but does not inhibit γ-secretase activity. ###, P < 0.001 vs. N1 ΔEGVP; §§§, P < 0.001 vs. N3 ΔEGVP. (D) Analysis of N ΔEGVP processing in the presence and absence of presenilins. Cleavage of N1 ΔEGVP and N3 ΔEGVP was analyzed in transiently transfected cells deficient for PS1 and PS2 (BD8 cells). No cleavage of the N ΔEGVP-encoding constructs is observed in BD8 cells in the absence of presenilin, whereas substantial processing is recorded after cotransfection of PS1 cDNA, PS2 cDNA, or both PS1 and PS2 cDNAs. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated three times. ***, P < 0.001 vs. Mock; ###, P < 0.001 vs. N1 ΔEGVP; §§§, P < 0.001 vs. N3 ΔEGVP.

To test the specificity of the assay we asked whether specific mutations at the cleavage site in the intracellular domain affected signaling. An exchange of the valine-1744 residue, critical for cleavage in vivo (26), for a glycine residue (Fig. 1A) reduced cleavage by approximately 60% in N1 ΔEGVP (Fig. 1B). Similarly, replacement in the N3 ΔEGVP construct of 3 aa located at the cleavage site resulted in a 75% reduction of cleavage (Fig. 1B). Notch receptors lacking the EGF repeats at the extracellular side (LNR constructs) have been shown to be deficient in intracellular cleavage (23), and transfection of a G4VP16 version of a Notch 1 LNR (N1 LNR GVP; Fig. 1A) did not result in detectable cleavage and activation (Fig. 1B). Finally, the use of specific γ-secretase inhibitors considerably reduced cleavage. The inhibitor L-685,458 (11) reduced cleavage of N1 ΔEGVP by 40% and N3 ΔEGVP by 85% at 25 μM, whereas the structurally related compound L-405,484, which is nonfunctional on APP cleavage, did not reduce cleavage of Notch 1 ΔEG4V16 and Notch 3 ΔEG4V16 by more than 5% (Fig. 1C). Addition of the inhibitor MW167 (10) at 20 μM led to a 90% reduction of cleavage for both Notch ΔE constructs (Fig. 1C). We conclude that the G4VP16-based assay is very sensitive and provides a specific readout for the γ-secretase-mediated cleavage of Notch.

Notch Intracellular Cleavage Completely Depends on Presenilin Function.

To assess whether Notch signaling completely depends on presenilin function, we tested the level of N1 ΔEGVP and N3 ΔEGVP cleavage in cells of different presenilin genotypes. Whereas very efficient activation from the UAS/promoter gene was observed in cells wild type for PS1 and PS2 (data not shown), no activation could be detected for either N1 ΔEGVP or N3 ΔEGVP in the cell line BD8 (Fig. 1D), which is derived from a mouse embryo lacking both PS1 and PS2 (14). Transfection of the BD8 cells with expression constructs for PS1, PS2, or both rescued reporter gene activation (Fig. 1D). These data indicate that no detectable Notch cleavage occurs in cells lacking both PS1 and PS2.

A Fluorimetric Peptide Assay for Analysis of Notch Intracellular Cleavage.

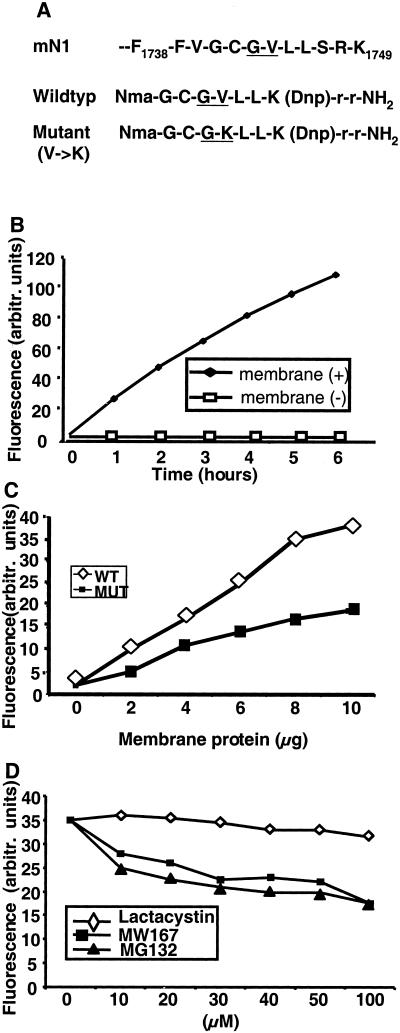

To study whether presenilins are the direct mediators of Notch cleavage, we used a well-established approach to identify protease activity based on an intramolecularly quenched fluorogenic peptide containing the cleavage site. A fluorogenic peptide covering the third proteolytic cleavage site in Notch 1 (amino acids GCGVLL, Fig. 2A) was tested for activity on a membrane fraction from HEK293T cells, which readily cleave the Notch ΔEG4VP16 proteins (see above) and thus contain presenilin activity. Incubation of the substrate peptide with the membrane fraction generated a fluorescence signal, which increased linearly for up to 6 h (Fig. 2B). The conversion rate increased in response to addition of larger amounts of the membrane fraction (Fig. 2C). Because Notch cleavage is shown to be sensitive to mutations at the intracellular cleavage site (25, 26) (see also Fig. 1B) we tested the efficacy of a peptide containing a valine-1744 to lysine substitution (CCGKLL). Cleavage was reduced to approximately 60% (Fig. 2C), which is in agreement with the reduction of cleavage observed in living cells (Fig. 1B) and in vivo (26).

Figure 2.

Specific cleavage of a Notch 1 fluorogenic peptide. (A) Depicted is the amino acid sequence encompassing the mouse N1 site 3 cleavage site. The wild-type (GCGVLL) and mutant V→K (GCGKLL) fluorogenic peptides are outlined below. The position at which the site 3 cleavage occurs is underlined. (B) Cleavage of the fluorogenic peptide depends on addition of membrane fraction. The fluorescence signal emitted from the cleaved peptide increased linearly with time when incubated with the membrane fraction for up to 6 h. No signal was observed when the peptide was incubated in the absence of membrane fraction. (C) Cleavage of the peptide is sequence-specific. The conversion rate measured after 120 min of incubation increased proportionally to the amount of membrane fraction added. The wild-type peptide (WT, ◊) was more frequently cleaved than the mutant (MUT, V→K) peptide (■) at all concentrations of membrane fraction. (D) Challenge of peptide cleavage with protease inhibitors. Cleavage of the wild-type peptide was inhibited by MW167 and MG132 but to a much lesser extent by clasto-lactacystin β-lactone.

We next tested the specificity of the assay by various protease inhibitors. The conversion rate decreased when the membrane was preincubated with MG132, a peptide aldehyde, which is known to inhibit the intracellular cleavage (25) and with MW167 (Fig. 2D). Because MG132 also is a proteasome inhibitor, the observed reduction could conceivably be mediated by this mechanism. However, incubation with another proteasome inhibitor, clasto-lactacystin β-lactone, did not result in decreased fluorescence (Fig. 2D). Other protease inhibitors, including the serine and cysteine protease inhibitors PMSF, E64, and antipain, did not alter the rate of conversion (data not shown). We conclude from these experiments that the cleavage of the Notch fluorogenic peptide is specific.

Purification of a Detergent Solubilized Notch Intracellular Cleavage Activity.

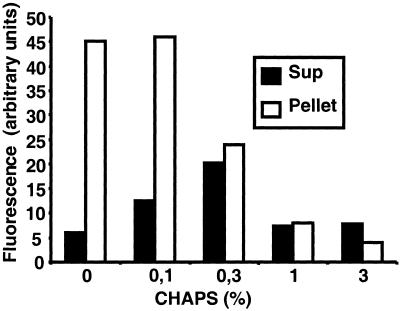

To purify the protein activity or activities responsible for cleavage of the Notch peptide, we first solubilized the crude membrane fraction with various detergents. Only CHAPS or CHAPSO (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate) solubilized the protease, whereas other detergents, like Triton X-100 or n-octyl-β-d-glucoside, failed to solubilize and retain the activity (data not shown). The optimal concentration of CHAPS was 0.25–0.3% (Fig. 3). Approximately 50% of the activity was solubilized by using 0.3% CHAPS, and an increase in the concentration of CHAPS resulted in a decrease in net peptide cleavage activity (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

A detergent solubilized Notch intracellular cleavage activity. Fluorogenic conversion of the wild-type Notch peptide measured in the supernatant (Sup, filled bars) or pellet (empty bars) from membrane fractions solubilized at different concentrations of CHAPS. Maximal solubilized activity was obtained at 0.3% CHAPS.

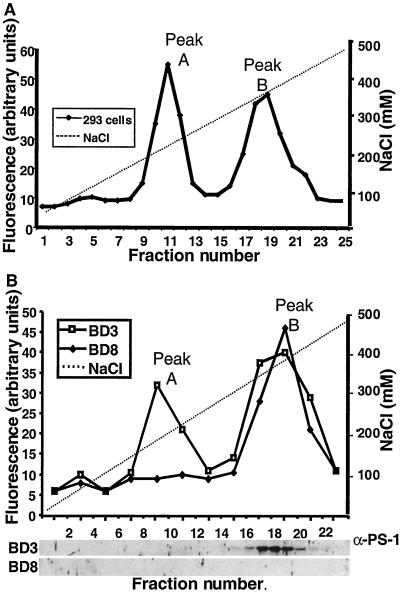

Next, we fractionated the cleavage activity based on charge distribution, using a Sepharose Q column. When the CHAPS-solubilized proteins were separated in the absence of EDTA, four distinct peaks of activity were identified (data not shown). In the presence of 10 mM EDTA two of the four peaks were retained (Fig. 4A), which we hereafter refer to as peak A and peak B. To test the specificity of the activities in peaks A and B we analyzed their efficiency in cleaving the cleavage site-mutated Notch fluorogenic peptide GCGKLL. The cleavage activity for the mutant peptide was considerably reduced in both peak A and B (69% and 38% of the wild-type peptide, respectively, Table 1). Furthermore, the activities in peaks A and B were inhibited by MG132, but not by leupeptin, another peptide aldehyde protease inhibitor (Table 1). This finding suggests that the activities in peaks A and B reflect a specific cleavage of the Notch intracellular site.

Figure 4.

Purification of the detergent-solubilized Notch intracellular cleavage activity based on charge distribution. (A) CHAPS-solubilized protein fractions of HEK293T cells were passed through a Sepharose Q column in the presence of 1 mM EDTA and eluted at various NaCl concentrations (0–500 mM NaCl). The eluates were investigated for fluorogenic conversion and two peaks were identified: peak A (fraction 9–13) and peak B (fraction 16–22). (B) Comparison of cleavage activities from presenilin-containing and presenilin-deficient cells. The fluorogenic conversion profiles from presenilin-containing BD3 (□) and presenilin-deficient BD8 (⧫) cells after separation over a Sepharose Q column. Note that peak A is present only in extracts from BD3 cells, whereas peak B is retained in extracts from both BD3 and BD8 cells. A Western blot analysis of the protein fractions from the BD3 and BD8 cells probed with an antibody to PS1 is shown at the bottom. Note that PS1 protein is detected only in BD3 cells, where it coincides with peak B.

Table 1.

Effects on conversion of the fluorogenic Notch peptide by the addition of protease or γ-secretase inhibitors or by presenilin immunodepletion

| PS (+/+)

|

PS (−/−)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak A | Peak B | Membrane | Membrane | |

| Wild-type peptide | 100 ± 2 | 100 ± 12 | 100 ± 6 | 100 ± 0 |

| + 50 μM Leupeptine | 107 ± 4 | 96 ± 1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| + 20 μM MG132 | 63 ± 2 | 68 ± 1 | 64 ± 4 | 58 ± 4 |

| + 20 μM MW167 | 97 ± 3 | 52 ± 0 | 75 ± 1 | 62 ± 6 |

| + 25 μM L-685,458 | 92 ± 2 | 85 ± 3 | 80 ± 2 | 89 ± 6 |

| + PS1 ab | 101 ± 3 | 69 ± 2 | n.d. | n.d. |

| + PS2 ab | 101 ± 1 | 76 ± 3 | n.d. | n.d. |

| MUT peptide | 69 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 57 ± 8 | n.d. |

Protein extracts from peak A, peak B, or crude membrane preparations from presenilin-containing (HEK293T or BD3) or presenilin-deficient (BD8) cells were analyzed for conversion of the Notch wild-type peptide with the protease inhibitors leupeptin and MG132 or with the γ-secretase inhibitors MW167 and L-685,458. The conversion activity after immunodepletion with PS1 or PS2 antibodies is shown. The conversion efficiency for the mutant Notch peptide (V → K, MUT peptide) is depicted. All values are shown as % cleavage as compared to cleavage of the wild-type peptide in peak A, peak B, or crude membrane preparations from HEK293T cells (wild-type peptide), which is set to 100%. Note that the activity in peak A is not sensitive to the γ-secretase inhibitors or to immunodepletion with presenilin antibodies. n.d., not determined.

Identification of a Notch Intracellular Cleavage Activity That Is Distinct from Presenilins.

We next addressed the requirements of presenilins for the activities in peaks A and B. Membrane extracts were prepared from cells deficient in both presenilins (BD8 cells) or from cells deficient in PS2, but retaining one gene copy of PS1 (BD3 cells). When CHAPS-solubilized proteins were separated on the Sepharose Q column, we observed that both peak A and B were present in extracts from the PS1-containing BD3 cells (Fig. 4B). In contrast, only peak B was retained in extracts from presenilin-deficient BD8 cells, whereas the activity in peak A was absent (Fig. 4B). Western blot analysis of the distribution of PS1 in BD3 cells demonstrated that PS1 was exclusively confined to peak B, whereas no PS1 was observed in peak A (Fig. 4B). We therefore conclude from this experiment that peak A is distinct from presenilins but completely depends on presenilin function.

To further assay the proteolytic profiles of the cleavage activities in peaks A and B, we challenged their activity in extracts from HEK293T cells with the γ-secretase inhibitors MW167 and L-685,458 and by presenilin immunodepletion experiments. MW167 reduced the activity only in peak B, whereas the activity in peak A was not altered (Table 1). In contrast, L-685,458 had relatively little effect on either of the two peaks in HEK293T cells (Table 1). The activity of peak B from BD8 cells was reduced by 30% by MW167 (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that peak A is insensitive to both inhibitors. To learn whether the activity in peak B is related to presenilins, we used antibodies to PS1 and PS2 to immunodeplete presenilins from peak B. Immunodepletion with antibodies to the intracellular loop regions of PS1 and PS2 reduced the activity in peak B from 293T cells to 69% and 76%, respectively (Table 1). As expected, the activity of peak A was not reduced by immunodepletion using the PS1 and PS2 antibodies (Table 1).

Discussion

In this article we present evidence that Notch intracellular cleavage in intact cells completely depends on presenilin function, based on a very sensitive assay for Notch intracellular domain release. We also show that partial purification of the Notch transmembrane domain cleavage activity generates one peak of activity, peak A, which does not contain presenilin protein, but is found only in presenilin-containing cells.

The Protease Activity in Peak A Is Presenilin-Dependent but Physically Distinct from Presenilins.

Peaks A and B were identified on the basis of cleaving a fluorogenic peptide containing the Notch 1 intracellular site, and there is some evidence suggesting that this cleavage is specific. First, cleavage of a peptide mutated at the 1744 valine residue is reduced to approximately the same extent in both peak A and B as it is when the mutation is introduced in the GAL4/VP16 constructs (Fig. 1), or when the effect of the mutation is related to the production of the intracellular domain (25). Furthermore, cleavage activity was reduced by MG132 and MW167, which affect processing at the Notch intracellular cleavage site (25).

Peak A is observed only in presenilin-containing cells. In contrast, the activity is completely lost in cells deficient for both PS1 and PS2, which demonstrates a strict dependence on presenilin function. A parsimonious explanation to these findings is that the protease activity in peak A requires a close interaction with and modification by presenilins to be able to cleave at the Notch intracellular site, but that a close physical association between presenilins and the protein(s) in peak A is not required after the modification. This hypothesis receives support from two observations. First, peak A activity does not require a close association with presenilins for cleaving Notch, because they segregate differently after protein fractionation. Second, peak A activity is not sensitive to the γ-secretase inhibitors directed to presenilins.

The nature of peak B and its relationship to presenilins is more complex. Although we cannot strictly prove that peak B in presenilin-containing and -deficient cells are identical, the fact that they have the same elution profile based on charge separation and that they respond similarly to MW167 would support this notion. The sensitivity to MW167 and the observation that immunodepletion with presenilin antibodies reduces the activity of peak B in presenilin-containing cells suggests some kind of relationship between peak B and presenilins, but the nature of this relationship remains to be established.

The Protease Activity in Peak A Is a Candidate for Notch Cleavage in Vivo.

As both peak A and peak B are specific for Notch intracellular cleavage in vitro, it raises the question as to which activity is important in the cell in vivo. The data from cleavage of the Notch ΔEGVP proteins strongly support that Notch intracellular cleavage strictly depends on presenilin function, because no cleavage can be detected in presenilin-deficient cells. This notion is supported by previous observations that the Notch cleavage cannot be detected in presenilin-deficient mouse (19) or Drosophila (20, 21) cells, and that loss of presenilin results in a Notch-like phenotype in mouse embryos lacking both PS1 and PS2 (14, 15). This would argue that the activity in peak A is the activity operating in Notch intracellular cleavage in vivo, because this activity is found exclusively in presenilin-containing cells and is lost in the presenilin-deficient cells. As a consequence, peak B, while specific for Notch cleavage in vitro, may not represent the activity that is operating in vivo. It seems likely that peak B is “activated” when cells are physically disrupted, because the crude membrane fraction from presenilin-deficient cells contains a cleavage activity, which cannot be the peak A activity. The nature of this activation, however, remains to be established.

In conclusion, the data presented here strongly support a model in which presenilin function on Notch is indirect and requires a distinct protease, which is activated by presenilins, possibly through the aspartyl protease activity in presenilins. Identification of this protease activity will help to decipher the mode of action of presenilins on their target proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. R. Kopan for the kind gift of plasmid ΔE-Notch1, Dr. J. Nye for the gift of LNRmNotch 1, Dr. M Shearman for the inhibitors L-685,458 and L-405,484, Dr. M. S. Wolfe for MW167, Dr. T. Iwatsubo for anti-presenilin antibodies, and Dr. H. Miyagawa for the use of HPLC. We are grateful to Dr. J. Näslund for valuable comments on the manuscript and Dr. J. Nye for sharing data before publication. The work is supported by the Swedish Cancer Society and Human Frontiers Science Program (to U.L.), Stiftelsen Gamla Tjänarinnor (to M.V.), AMF sjukförsäkrings jubileumsstipendier (to J.L.), and the Center of Excellence Grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports of Japan (to T.H.).

Abbreviations

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- CHAPS

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate

- PS1

presenilin 1

- PS2

presenilin 2

Footnotes

Molinoff, B. P., Felsenstein, M. K., Smith, W. D. & Barten, M. D. (2000) Neurobiol. Aging 21, S136 (abstr.).

References

- 1.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand M D, Lake R J. Science. 1999;284:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frisén J, Lendahl U. BioEssays. 2001;23:3–7. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200101)23:1<3::AID-BIES1001>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidd S, Lieber T, Young M. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3728–3740. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lecourtois M, Schweisguth F. Curr Biol. 1998;8:771–774. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroeter E H, Kisslinger J A, Kopan R. Nature (London) 1998;393:382–385. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Struhl G, Adachi A. Cell. 1998;93:649–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopan R, Goate A. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2799–2806. doi: 10.1101/gad.836900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vassar R, Citron M. Neuron. 2000;27:419–422. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selkoe D J. Nature (London) 1999;399:A23–A31. doi: 10.1038/399a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esler W P, Kimberly W T, Ostaszewski B L, Diehl T S, Moore C L, Tsai J-Y, Rahmati T, Xia W, Selkoe D J, Wolfe M S. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:428–434. doi: 10.1038/35017062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y-M, Xu M, Lai M-T, Huang Q, Castro J L, DiMuzio-Mower J, Harrison T, Lellis C, Nadin A, Neuduvelli J G, et al. Nature (London) 2000;405:689–694. doi: 10.1038/35015085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seiffert D, Bradley J D, Rominger C M, Rominger D H, Yang F, Meredith J E J, Wang Q, Roach A H, Thompson L A, Spitz S M, et al. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34086–34091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capell A, Steiner H, Romig H, Keck S, Baader M, Grim M G, Baumeister R, Haass C. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:205–211. doi: 10.1038/35008626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donoviel D B, Hadjantonakis A-K, Ikeda M, Zheng H, St George Hyslop P, Bernstein A. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2801–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.21.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herreman A, Hartmann D, Annaert W, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Serneels L, Umans L, Schrijvers V, Checler F, Vanderstichele H, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11872–11877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Z, Nadeau P, Song W, Donoviel D, Yuan M, Bernstein A, Yankner B A. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:463–465. doi: 10.1038/35017108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levitan D, Greenwald I. Nature (London) 1995;377:351–354. doi: 10.1038/377351a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berechid B E, Thinakaran G, Wong P C, Sisodia S S, Nye J S. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1493–1496. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Mumm J S, Schoreter E H, Schrijvers V, Wolfe M S, Ray W J, et al. Nature (London) 1999;398:518–521. doi: 10.1038/19083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Struhl G, Greenwald I. Nature (London) 1999;398:522–524. doi: 10.1038/19091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye Y, Lukinova N, Fortini M E. Nature (London) 1999;398:525–529. doi: 10.1038/19096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song W, Nadeau P, Yuan M, Yang X, Shen J, Yankner B A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6959–6963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mumm J S, Schroeter E H, Saxena M T, Griesemer A, Tian X, Pan D J, Ray W J, Kopan R. Mol Cell. 2000;5:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petit A, Bihel F, Alvès da Costa C, Pourquié O, Checler F, Kraus J-L. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:507–511. doi: 10.1038/35074581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopan R, Schroeter E H, Weintraub H, Nye J S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1683–1688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huppert S S, Le A, Schroeter E H, Mumm J S, Saxena M T, Milner L A, Kopan R. Nature (London) 2000;405:966–970. doi: 10.1038/35016111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beatus P, Lundkvist J, Öberg C, Lendahl U. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:3925–3935. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brou C, Logeat F, Gupta N, Bessia C, LeBail O, Doedens J R, Cumano A, Roux P, Black R A, Israël A. Mol Cell. 2000;5:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.