Abstract

Preeclampsia is a common pregnancy-specific vascular disorder that develops during the second half of pregnancy. Preeclampsia shares features with thrombotic microangiopathies. Here we analyzed whether sequence variants in the coagulation system genes predispose to preeclampsia. We performed targeted exomic sequencing of 58 genes in a total of 615 preeclamptic women and 2094 controls. A common missense variant rs1800385 (Val1565Leu) in the gene coding for von Willebrand Factor (VWF) (OR=1.72, p-value=3.57E-4) and a low-frequency missense variant rs41314453 (Ala732Val) in the gene coding for a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13 (ADAMTS13) (OR=1.97, p-value=0.044) were associated with preeclampsia. rs41314453 is known to decrease ADAMTS13 expression and activity. Thus, the reduced enzyme activity could promote the formation of large vWF polymers on endothelial cells and platelets and thereby increase vascular prothrombotic activity in preeclampsia. Our results support a role for an impaired ability of ADAMTS13 to limit VWF polymerization in the pathogenesis of PE. Ultralarge multimers of VWF could mediate platelet accumulation in the turbulent intervillous spaces in preeclamptic placentae, calling upon novel therapeutics to control the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis in severe cases having low ADAMTS13 in the presence of high VWF levels and multimerization.

Keywords: preeclampsia, pregnancy, coagulation cascade, von willebrand factor, ADAMTS13, genetic association

Introduction

Preeclampsia (PE) is a common pregnancy-specific vascular disorder with diverse clinical characteristics. It affects approximately 3% of pregnancies and accounts for over 50,000 maternal and 900,000 perinatal deaths annually1. No specific treatment, other than delivery, is available for PE. For prevention, low-dose aspirin administered from < 16 weeks of gestation has been suggested to reduce the risk of preterm PE (resulting in delivery before 37 wks of gestation) in women at high risk for PE, but its use remains controversial2. Despite common signs, proteinuria and hypertension, the etiology of PE could be heterogeneous, especially in a subset of cases.

There is a familial predisposition to PE and strong epidemiological evidence suggests that the risk for PE is inherited3. However, the individual variant effects of the candidate genes discovered thus far are modest. Finnish population presents an opportunity to study complex diseases, because the allele frequencies observed in the modern Finnish population result from several bottleneck events in the founder population which helps to identify relevant pathways for disease pathogenesis due to the enrichment of associating variants4.

The coagulation system is activated by changes in the vascular endothelium, and by platelet activation, adhesion, aggregation and interaction among leukocytes. In these processes, platelet interactions with von Willebrand factor (VWF) are an important contributor. Dysregulation of the platelet activity and coagulation system may result in thrombotic microangiopathies, including hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia in women with PE5. No firm consensus regarding the role of platelets and coagulation biology in the development of PE has been reached6–8. Early results linking common variants such as FV Leiden and the prothrombin 3′ UTR variant to PE risk have not been replicated in larger studies9.

To investigate the role of the genetic burden of coagulation proteins in PE, we designed a targeted exome sequencing study to screen the exons and splicing sites of genes involved in blood coagulation and its regulation.

Results

In the 58 selected genes we discovered 107 annotated variants and 151 presumably benign variants (data not shown). Key results of this association analysis are shown in Table 2 (significant and borderline significant variants noted). The significantly associated variants in Table 2 are all listed as variant of unknown significance by the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) classification10. Overall, the most significant associations were available in the hemostasis axis, including VWF and its size-regulating ADAMTS13 enzyme. Also, two protective antithrombin variants were discovered.

Table 2.

Variants with significant or suggestive associations to preeclampsia within genes coding for coagulation proteins. Loss of function (LoF) is given per gene. All variants in Table 2 had a The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics classification of variant of uncertain significance due to not enough evidence.

| RSID number | Gene name | P-value | OR (95% confidence interval) | MAFcases | MAFcontrols | Consequence (distance from exon, base pairs) | LoFtool* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1800385 | VWF | 3.57E-4 | 1.72 (1.27 – 2.32) | 0.059 | 0.035 | missense variant, V1565L | 0.03 |

| rs34444862 | VWF | 0.01 | 2.30 (1.19 – 4.35) | 0.015 | 0.007 | intron variant (−8) | |

| rs34230288 | VWF | 0.02 | 2.18 (1.11 – 4.17) | 0.014 | 0.007 | missense variant, A2178S | |

| rs36219245 | ADAMTS13 | 8.62E-4 | 0.57 (0.40 – 0.80) | 0.053 | 0.089 | splice region variant (+4) | 0.52 |

| rs36218903 | ADAMTS13 | 2.28E-3 | 3.06 (1.42 – 6.52) | 0.012 | 0.004 | intron variant (−33) | |

| rs41314453 | ADAMTS13 | 0.04 | 1.97 (0.99 – 3.78) | 0.013 | 0.007 | missense variant, A732V | |

| rs5898 | F2 | 0.03 | 1.31 (1.01 – 1.69) | 0.077 | 0.060 | synonymous variant, P395P | 0.13 |

| rs2301515 | F5 | 8.06E-3 | 1.21 (1.05 – 1.39) | 0.014 | 0.007 | intron variant (−50) | 0.09 |

| rs6023 | F5 | 0.01 | 1.48 (1.07 – 2.03) | 0.050 | 0.034 | splice region variant (+7) | |

| rs6025 | F5 | 0.05 | 1.49 (1.01 – 2.21) | 0.030 | 0.021 | missense variant, R534Q | |

| rs9332688 | F5 | 0.02 | 2.10 (1.07 – 3.98) | 0.014 | 0.007 | intron variant (−32) | |

| rs900258823 | F5 | 0.05 | 1.49 (1.01 – 2.21) | 0.030 | 0.021 | intron variant (−7098) | |

| rs6042 | F7 | 0.02 | 1.32 (1.04 – 1.67) | 0.086 | 0.067 | synonymous variant, H176H | 0.07 |

| rs6109 | SERPINA5 | 5.70E-3 | 1.22 (1.06 – 1.41) | 0.313 | 0.272 | intron variant (−34) | 0.06 |

| rs6115 | SERPINA5 | 0.04 | 1.15 (1.01 – 1.32) | 0.367 | 0.335 | missense variant, S64N | |

| rs5878 | SERPINC1 | 0.02 | 1.17 (1.02 – 1.35) | 0.316 | 0.282 | synonymous variant, Q337Q | na |

| rs5877 | SERPINC1 | 0.03 | 1.17 (1.01–1.34) | 0.301 | 0.269 | synonymous variant, V327V | na |

LoF tool – (loss of function tool); score of LoF susceptibility per gene < 0.2 = probably damaging, 0.2–0.7 = possibly damaging, > 0.7 = benign

na – not available

RSID – Single nucleotide polymorphism identifier, OR – Odds Ratio, MAF – Minor Allele Frequency

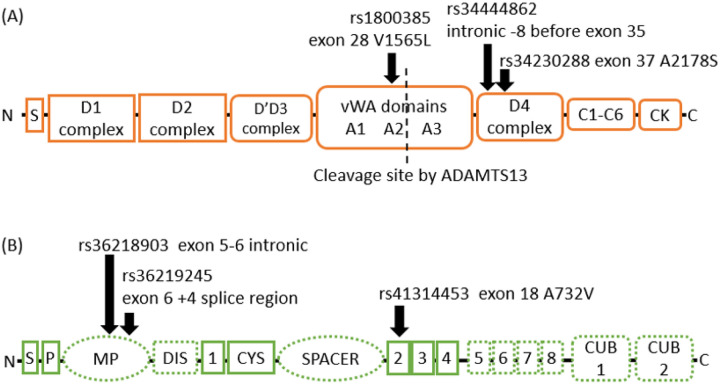

The gene coding for von Willebrand Factor (VWF) wasassociated with PE by three likely or probable LoF variants with significant p-values (Figure 1A). Rs1800385 (p.Val1565Leu) in the middle of the VWF gene is a missense variant that increases the risk for PE (OR=1.72, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.27–2.32, p-value=3.57E-4). The intronic variant rs34444862 located 8 base pairs downstream of exon 35, and the second missense variant rs34230288 (p.Ala2178Ser) increase the risk for PE (OR=2.30, 95%CI=1.19–4.35, p-value=0.01; OR=2.2, CI 1.11–4.17, p-value=0.017, respectively).

Figure 1.

Domain structure of von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS13 with associating variants indicated with black arrows. Panel (A) von Willebrand factor (VWF) protein consists of eight functional classes of domains (29 in total, not shown) encoded by 52 exons (not shown). The domains in the propeptide region consisting of 741 amino acids are marked with sharp-cornered boxes and the domains that produce the mature VWF consisting of 2050 amino acids are marked by round-cornered boxes. The cleavage site of ADAMTS13 in the A2 domain is indicated with a dashed vertical line.

Panel (B). ADAMTS13 consists of 12 domains that are encoded by 29 exons. The domains of the ADAMTS13 are a signal peptide (S), a propeptide (P), a metalloprotease domain (MP), a disintegrin domain (DIS), 8 thrombospondin type 1 domains (1–8), a cysteine-rich region (CYS), a spacer domain and two CUB domains. The domains that bind VWF are marked with dashed outlines. The disintegrin and spacer domains cleave the VWF A2 domain. The thrombospondin type domains 5–8 and CUB domains bind D4 and CK domains of VWF.

In ADAMTS13, the intronic variant rs36218903 increased the risk for PE (OR=3.06, CI 95%=1.42–6.53; p-value=0.002), while the splice region variant rs36219245 decreased risk (OR=0.57, 95% CI 0.40–0.80; p-value=8.62E-4), (Figure 1B). The missense variant rs41314453 (Ala732Val) in ADAMTS13 had a suggested increase in PE risk (OR=1.97, 95% CI=0.99–3.78; p-value=0.044).

We also found that in our cohorts rs5878 and rs5877 in SERPINC1 encoding for antithrombin (III), a critical plasma protease inhibitor and a member of the serpin superfamily, decreased the risk for PE (OR= 0.85 (95% CI=0.74 – 0.98), and 0.86 (95% CI=0.74–1), p-value=0.02 and 0.03, respectively).

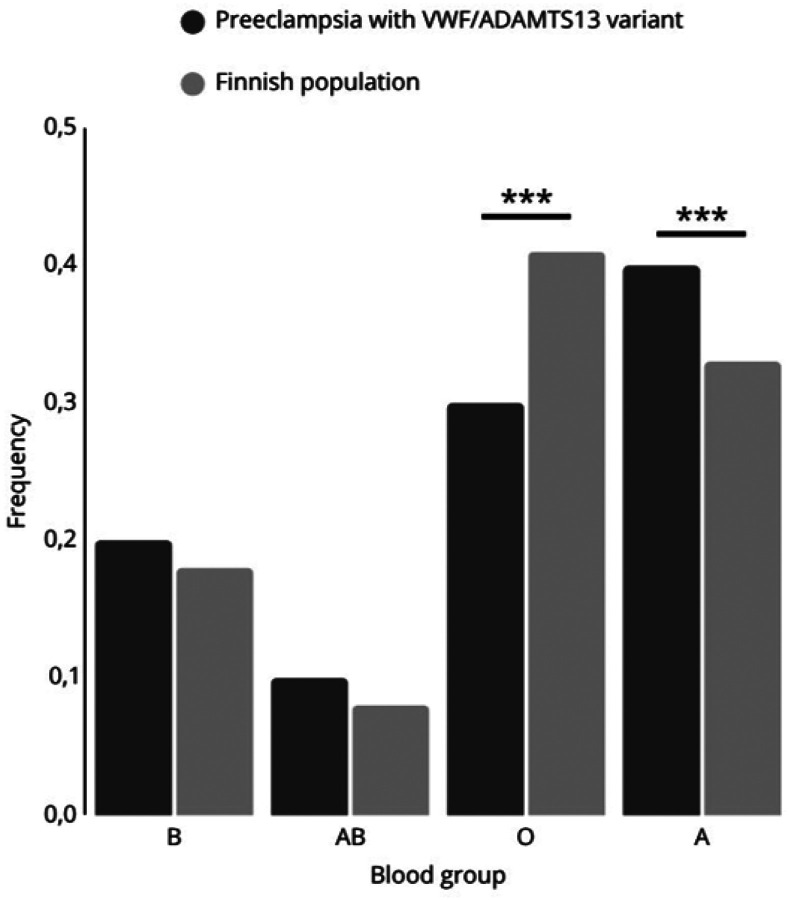

Comparison of the frequency of blood groups between patients carrying VWF and/or ADAMTS13 variants in the Finnish population revealed that women affected by PE blood group A are significantly more prevalent (X2 = 16.227, p<0.0001; Figure 2). In contrast, blood group O was significantly underrepresented in the PE patients (X2 = 21.403, p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Frequency of blood groups of preeclampsia patients with any predisposing VWF/ADAMTS13 allele (pe; N=80) and in the Finnish population (fin; N=5536, source: Finnish Red Cross Blood Service). *** indicates p<0.0001.

Discussion

Our results suggest that genetic variants in VWF and in its size and functional regulator ADAMTS13 associate with primary hemostasis abnormalities. Variants in genes coding for both proteins may predispose to PE. Women with blood group A are at particular risk of VWF-mediated PE, while mothers with blood group O have a lower incidence of PE.

These observations further support the proposed causative role of platelet dysregulation in a specific subgroup of PE. Importantly, we found associations within the VWF and ADAMTS13 axis, that cooperates to promote platelet-vascular wall interactions. A decrease in ADAMTS13 activity and an increase in VWF levels have also been previously associated with PE11, although the underlying and causative mechanisms in the VWF pathway have been under debate12,13. It is possible that VWF abnormalities are particularly associated with PE with severe features14. Common genetic variants within other coagulation genes are associated with PE15. Two of the discovered common PE-associating variants rs5878 and rs5877 in SERPINC1 that encode antithrombin are related reduced generation of thrombin and formation of fibrin. While we were able to confirm the reported association between Factor V Leiden (rs6025) and PE, the literature provides sparse insight into the potential associations we discovered in other F5 loci or variants discovered in F2, F7, and SERPINA5. Overall, the link between common coagulation variants, regulation of the coagulation system and an increased risk of preeclampsia16,17 was strongly corroborated by our data.

VWF is a plasma, platelet and endothelial glycoprotein that maintains hemostasis by generating multimers, which induce platelet aggregation and bind several proteins on activated endothelial cells in the vascular wall. Thereby, the multimers can lead to loss of vascular endothelial integrity18. This is particularly relevant in the placental vasculature due to its specific hemodynamic conditions. To prevent excessive platelet responses and coagulation, VWF oligomers emerging from endothelial cells or activated platelets are proteolytically cleaved by the ADAMTS13 enzyme19,20. ADAMTS13 cleaves VWF between tyrosine and methionine at position 842–843. Mutations in the ADAMTS13 gene or, more commonly, autoantibodies against the ADAMTS13 enzyme cause thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

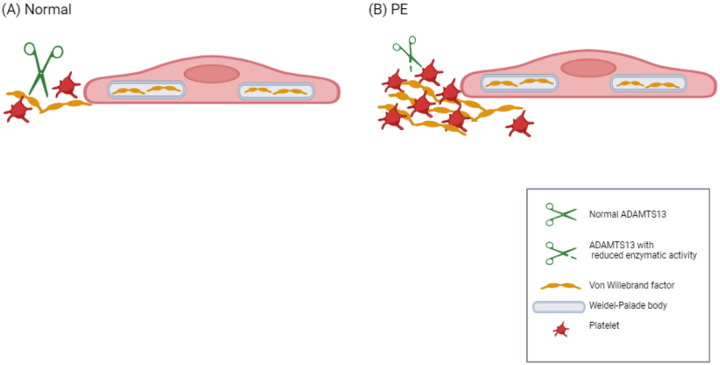

The variant rs34230288 results in the replacement of the alanine at position 2178 with a serine in VWF. This variant has been observed in a patient who was in cis heterozygous for two VWF mutations and suffering from a noncanonical type 2B von Willebrand disease characterized by low VWF activity21. Similarly, the variant rs1800385 results in the replacement of valine at position 1565 by leucine resulting in significantly elevated ADAMTS13 activity but available data is insufficient to ascertain it’s functional relevance22. Rs41314453 is the main genetic determinant of ADAMTS13 activity. It is important to note that it is in linkage disequilibrium with several intronic variants in ADAMTS13 and variants in the regulatory regions of neighbouring genes23. The total effect of rs41314453 is dependent on the sequence context, which may influence the extent and direction of its effect on gene expression24. It has been estimated that the variant reduces ADAMTS13 levels by approximately 40%23,24. Although this magnitude of a decrease does not reach levels that are considered significant in TTP (< 10%), it may be significant in the context of the strong triggers such as pregnancy. The product of the ADAMTS13 gene with the minor allele T of rs41314453 has up to 29% less VWF cleavage activity than the protein coded by the gene with the major allele24. Thereby, rs41314453 may increase the risk for platelet deposition by accumulation of ultralarge VWF multimers (Fig. 3). In TTP, the accumulation of platelet-super-adhesive ultralarge VWF multimers on vascular endothelium leads to the spontaneous formation of microthrombi. Pregnancy is also one of the well-known triggers to precipitate attacks of TTP5.

Figure 3.

Schematic depiction of the proposed role of the ADAMTS13 Ala732Val variant in PE. In normal pregnancy (panel A), the cleavage of Weibel-Palade body-derived VWF from endothelial cells by ADAMTS13 prevents excessive VWF multimerization. In preeclampsia pregnancies (panel B) with rs41314453*T of ADAMTS13, the amount or enzymatic activity of ADAMTS13 is reduced thereby enhancing multimeric VWF and platelet aggregation. Created with BioRender.com.

We recorded the blood groups of the women due to their role in association with VWF levels. Persons with blood group O have 30% lower VWF expression than the other blood groups, and blood group O has implications for platelet physiology25. Previously, blood groups A and more convincingly AB have been linked to a modestly increased risk of PE26,27. In addition, blood group A has been found to predispose to severe COVID-19, while blood group O is protective against infection and microthrombosis28. Concurrently, blood group O carries a 30% lower level of VWF, which may be highly elevated in COVID-1929,30. COVID-19 infection is also an independent risk factor for PE33. Our observed genetic variants of VWF, ADAMTS13 and non-O blood groups, likely contribute to the pathogenesis of PE. Furthermore, these findings may be helpful in the future to risk stratify patients and target novel therapies based on the specific analysis of VWF and ADAMTS13 biomarkers31

The findings of our study may explain aspects of the pathophysiology of PE and clinical observations related to the preventive use of aspirin. In PE, the placental intervillous blood flow is perturbed due to the lack of vasodilation in the spiral arteries, and local high shear forces prevail, promoting platelet-VWF interactions32,33. This also increases the risk of local red blood cell lysis and promotes the release of ADP and thromboxane A2, which are known to further activate platelets. ADP increases the expression and release of VWF on platelets34. Associated activation of the complement system results in the formation of C5a and of membrane attack complexes, which can further activate platelets and induce release of VWF from endothelial cell Weibel-Palade bodies35–37. Subsequent reduced ability of ADAMTS13 to cleave VWF multimers would thus promote formation of platelet aggregates, which have been shown to be resistant to ADAMTS1338. On the other hand, VWF has been shown to protect the endothelium from complement-mediated injury39. Aspirin has been shown to reduce expression of VWF on platelet surfaces34. Thereby it may partially compensate for the procoagulant effect of rs41314453 on ADAMTS13. Reduced platelet activity may improve blood flow in the intervillous space and reduce local ischemia and the severity of PE. TTP is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes including PE40. Previously, a patient suffering from TTP due to a mutation in ADAMTS13 experienced a successful pregnancy under prophylactic treatment by aspirin41. More recently, novel drugs to influence the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis have emerged. Drugs like caplacizumab or recombinant ADAMTS13 could thus potentially be used in severe cases that are linked to high level of VWF multimerization and thrombosis42.

In TMA, activation of the coagulation cascade and complement systems often go hand in hand43. Similarly, pregnancy is an inflammatory and procoagulative state. In a blood proteomic study, the most different expression patterns between preeclamptic patients and controls were observed in complement and coagulation pathways and platelet function and VWF were also implicated44. Thereby patients with a predisposing complement and/or coagulation pathway variants may present with TMA-like PE45.

This study was limited by unavailability to study VWF and ADAMTS13 activity or their biomarkers. Furthermore, complete blood cell counts were not measured routinely thereby rendering the analysis of this data inconclusive. The effect of blood group for PE risk in carriers of VWF and ADAMTS13 variants requires further investigation in other well-described case-control cohorts representing varied populations.

In summary, our findings demonstrate a link between PE and two important and related hemostatic components VWF and ADAMTS13. Our results support the concept that in some cases, PE with severe features may present as a thrombotic microangiopathy45. The fact that PE-associated rs41314453 reduces ADAMTS13 level suggests that the ADAMTS13-VWF axis and regulated VWF size or multimerization are important in preventing PE. Our results may also relate to aspirin, which may show preventive properties against preeclampsia in high-risk individuals. However, in the future based on laboratory assessment of VWF and ADMTS13, novel medications, such as caplacizumab and recombinant ADAMTS13 should be evaluated in PE.

Methods

Patient cohorts

Two independent case-control cohorts, The Finnish Genetics of preeclampsia Consortium (FINNPEC) cohort and the national FINRISK study cohort were investigated. The study rational is described in detail in the supplementary data. In the final association analyses, we included genotypes of FINNPEC and FINRISK population cohorts, leading to a combined total of 615 cases and 2094 controls. For FINNPEC, all women provided a written informed consent, and the FINNPEC study protocol was approved by the coordinating Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa. (FINRISK license 8/2016)46. The patients and controls from the FINNPEC cohort are characterized in the Supplementary table S1. The National FINRISK Study description and ethical approvals are available online: https://www.thl.fi/en/web/thlfi-en/research-and-expertwork/population-studies/the-national-finrisk-study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Targeted Sequencing and Capture Enrichment

Libraries from genomic DNA were prepared in-house (Washington University School of Medicine)47. Enzymes were purchased from Enzymatics (Beverly, MA). Briefly, the ends of sheared genomic DNA fragments were repaired by treatment with T4 DNA Polymerase and T4 DNA Polynucleotide Kinase, which phosphorylates the 5’ hydroxyl. Next, an adenosine was added to the 3’ position at each end of the DNA fragment with Taq Polymerase. Illumina adapters with an overhanging “T” were ligated onto the DNA fragment followed by bead-based size selection to remove adapter-dimers and fragments below the desired size. A barcode consisting of a unique index sequence was added by PCR by targeting the two ligated universal adapters on each fragment end. Sequence capture hybridization and other laboratory methods are described in the Supplementary data. The studied genes and intronic loci of interest are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Targeted coagulation-associated genes and intronic loci.

| Coagulation-associated genes | Coagulation loci | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | SNP | ||||

| ABO | F7 | KLKB1 | SERPNA5 | F2 | rs1799963 |

| ADAMTS13 | F8 | KNG1 | SERPNB2 | F5 | rs6020 |

| ADRA2A | F9 | MRVI1 | SERPNC1 | SERPINE1 | rs2227631 |

| CD36 | FGA | PEAR1 | SERPND1 | ||

| F10 | FGB | PIK3CG | SERPNE1 | ||

| F11 | FGG | PLAT | SERPNE2 | ||

| F12 | GP1BA | PLAU | SHH | ||

| F13B | GP1BB | PLG | STX2 | ||

| F2 | GP5 | PROC | STXBP5 | ||

| F2R | GP6 | PROCR | SVIL | ||

| F2RL1 | GP9 | PROS1 | TFPI | ||

| F2RL2 | IPCEF1 | PROZ | TFPI2 | ||

| F2RL3 | ITGA2B | SELP | VSGI4 | ||

| F3 | ITGB3 | SERPINA1 | VWF | ||

| F5 | JMJD1C | SERPINA10 | |||

Fisher’s exact t-test was used as the primary test of association, and differences in frequencies of variants with p-value < 0.05 were considered significant. Significant and borderline significant variants are listed in Table 2. In addition to the statistical probability test, odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI95) were calculated for all variants.

Comparison of the distribution of P values in benign (synonymous, intronic/intergenic; 151 observed variants) vs. annotated (missense, truncating, essential splice and splice region; 107 observed variants) variants indicate that the expected incidence of two annotated variants with p<0.001 is less than 0.01 in our data, compared with 0 observed variants with p<0.001. The lack of inflated P values indicates that confounders, such as stratification, are not causing false positives. Loss of function (LoF) analyses were done in silico for all genes with associating variants by the Loss of Function – tool of the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) (https://github.com/ensembl-variation/VEP_plugins/blob/master/LoFtool.pm). In the LoF tool, the following annotations were calculated: LoF score < 0.2 indicates a probably damaging variant, LoF score 0.2–0.7 possibly damaging and LoF score < 0.7 a benign variant. 5/7 of the genes in Table 2 had scores < 0.2, suggesting a probable LoF.

Data were analyzed using PlinkSeq, Plink48 and R. Kaviar49. VEP Build 37 was used for additional annotations50.

Supplementary Files

This is a list of supplementary files associated with this preprint. Click to download.

Acknowledgements

We thank Elisha D.O. Roberson for assistance in data analysis (P30-AR073752).

FINNPEC study board consists of Hannele Laivuori (PI), Seppo Heinonen, Eero Kajantie, Juha Kere, Katja Kivinen, and Anneli Pouta. Eija Kortelainen and late Susanna Mehtälä provided technical assistance. We thank all the participants of the FINNPEC study as well as participants of FinMetSeq and FINRISK population cohort studies.

Funding

This study was supported by Alfred Kordelin Foundation (AIL), Maud Kuistila Foundation, Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation (HL), The Academy of Finland (121196 and 278941; HL), Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (HL, SM) and Special State Subsidy for Health Research (TYH2019311, TYH2022315; SM, TYH2020318; RL TYH2021315, TYH2022315; HL). This research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers F30 HL103072 (MT), U54 HL112303 (JPA), R01 GM099111 (JPA), and P30 AR048335 (JPA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Finnish Medical Foundation (HL), University of Helsinki Funds (HL), Sakari and Päivikki Sohlberg Foundation (HL), Novo Nordisk Foundation and Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation for Pediatric Research contributed to the FINNPEC sample collection.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Alfred Kordelin Foundation (AIL), Maud Kuistila Foundation, Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation (HL), The Academy of Finland (121196 and 278941; HL), Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (HL, SM) and Special State Subsidy for Health Research (TYH2019311, TYH2022315; SM, TYH2020318; RL TYH2021315, TYH2022315; HL). This research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers F30 HL103072 (MT), U54 HL112303 (JPA), R01 GM099111 (JPA), and P30 AR048335 (JPA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Finnish Medical Foundation (HL), University of Helsinki Funds (HL), Sakari and Päivikki Sohlberg Foundation (HL), Novo Nordisk Foundation and Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation for Pediatric Research contributed to the FINNPEC sample collection.

Footnotes

Additional Declarations: Competing interest reported. RL is a member of an advisor board and given lectures for Sanofi and Takeda. AJ serves on the scientific advisory boards of Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, and Novartis International AG, and serves as a consultant for Dianthus Therapeutics and Aurinia Pharmaceuticals. She has been a Principal Investigator for Apellis Pharmaceuticals and is a Principal Investigator for Novartis International AG. She also receives royalty from UptoDate. HL has received honoraria from Orion Corporation. JPA is in the Scientific Advisory Board of Complement Corporation and Kypha, Inc; Scientific Advisory Board. Furthermore, he serves as a consultant in Celldex Therapeutics, formerly Avant Immunotherapeutics, Inc., Biothera and Clinical Pharmacy Services, CDMI. SM has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Biogen, Merck, Pfizer and UCB, and research funding from Alexion. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

A. Inkeri Lokki, University of Helsinki.

Michael Triebwasser, University of Michigan.

Emma Daly, Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Mitja I. Kurki, University of Helsinki

Markus Perola, National Institute for Health and Welfare.

Kirsi Auro, National Institute for Health and Welfare.

Anuja Java, Washington University School of Medicine.

Jane E. Salmon, Weill Medical College of Cornell University

Seppo Heinonen, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital.

Eero Kajantie, Norwegian University of Health and Technology.

Juha Kere, Karolinska Institutet.

Riitta Lassila, University of Helsinki, Helsinki University Hospital.

Mark Daly, University of Helsinki.

John P. Atkinson, Washington University School of Medicine

Hannele Laivuori, Tampere University.

Seppo Meri, University of Helsinki.

Data-sharing statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from Professor Hannele Laivuori on reasonable request.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from Professor Hannele Laivuori on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Van Lerberghe W., Manuel A., Matthews Z. & Cathy W. The World Health Report 2005 - Make Every Mother and Child Count. (2005).

- 2.Rolnik D. L. et al. Aspirin versus Placebo in Pregnancies at High Risk for Preterm Preeclampsia. New England Journal of Medicine (2017) doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1704559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skjaerven R. et al. Recurrence of pre-eclampsia across generations: exploring fetal and maternal genetic components in a population based cohort. BMJ 331, 877 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim E. T. et al. Distribution and Medical Impact of Loss-of-Function Variants in the Finnish Founder Population. PLoS Genet 10, e1004494 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCrae K. R. Thrombocytopenia in pregnancy. Hematology.American Society of Hematology.Education Program 2010, 397–402 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boij R. et al. Biomarkers of coagulation, inflammation, and angiogenesis are independently associated with preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 68, 258–270 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehkordi M. A. e. R., Soleimani A., Haji-Gholami A., Vardanjani A. K. & Dehkordi S. A. e. R. Association of deficiency of coagulation factors (Prs, Prc, ATIII) and FVL positivity with preeclampsia and/or eclampsia in pregnant women. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res (2014). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han L. et al. Blood coagulation parameters and platelet indices: Changes in normal and preeclamptic pregnancies and predictive values for preeclampsia. PLoS One (2014) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staines-Urias E. et al. Genetic association studies in pre-eclampsia: systematic meta-analyses and field synopsis. Int J Epidemiol 41, 1764–1775 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richards S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. (2015) doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aref S. & Goda H. Increased VWF antigen levels and decreased ADAMTS13 activity in preeclampsia. Hematology 18, 237–241 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stepanian A. et al. Von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS13: a candidate couple for preeclampsia pathophysiology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31, 1703–1709 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molvarec A. et al. Increased plasma von Willebrand factor antigen levels but normal von Willebrand factor cleaving protease (ADAMTS13) activity in preeclampsia. Thromb Haemost 101, 305–311 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang D. et al. Von Willebrand factor antigen and ADAMTS13 activity assay in pregnant women and severe preeclamptic patients. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.Medical sciences = Hua zhong ke ji da xue xue bao.Yi xue Ying De wen ban = Huazhong keji daxue xuebao.Yixue Yingdewen ban 30, 777–780 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nieves-Colón M. A. et al. Clotting factor genes are associated with preeclampsia in high-altitude pregnant women in the Peruvian Andes. The American Journal of Human Genetics 109, 1117–1139 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J., Ma H. P., Ti A. L. T. T. L., Zhang Y. Q. & Zheng H. Prothrombotic SERPINC1 Gene Polymorphism may Affect Heparin Sensitivity among Different Ethnicities of Chinese Patients Receiving Heart Surgery. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis (2015) doi: 10.1177/1076029614556744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao C. et al. Heparin promotes platelet responsiveness by potentiating alphaIIbbeta3-mediated outside-in signaling. Blood 117, 4946–4952 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadler J. E. Biochemistry and genetics of von Willebrand factor. Annu Rev Biochem 67, 395–424 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong J. fei et al. ADAMTS-13 metalloprotease interacts with the endothelial cell-derived ultra-large von Willebrand factor. J Biol Chem 278, 29633–29639 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiang Y., De Groot R., Crawley J. T. B. & Lane D. A. Mechanism of von Willebrand factor scissile bond cleavage by a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13 (ADAMTS13). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 11602–11607 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacco M. et al. Noncanonical type 2B von Willebrand disease associated with mutations in the VWF D’D3 and D4 domains. Blood Adv 4, 3405–3415 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lasom S. et al. Protective effect of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13 haplotype on coronary artery disease. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 28, 286–294 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Vries P. S. et al. Genetic variants in the ADAMTS13 and SUPT3H genes are associated with ADAMTS13 activity. Blood (2015) doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-629865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plaimauer B. et al. Modulation of ADAMTS13 secretion and specific activity by a combination of common amino acid polymorphisms and a missense mutation. Blood 107, 118–125 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward S. E., O’Sullivan J. M. & O’Donnell J. S. The relationship between ABO blood group, von Willebrand factor, and primary hemostasis. Blood 136, 2864–2874 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phaloprakarn C. & Tangjitgamol S. Maternal ABO blood group and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Journal of Perinatology 33, 107–111 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alpoim P. N. et al. Preeclampsia and ABO blood groups: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep (2013) doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu N. et al. The impact of ABO blood group on COVID-19 infection risk and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Rev 48, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ladikou E. E. et al. Von Willebrand factor (vWF): marker of endothelial damage and thrombotic risk in COVID-19? Clinical Medicine 20, e178 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill J. C., Endres-Brooks J., Bauer P. J., Marks W. J. & Montgomery R. R. The Effect of ABO Blood Group on the Diagnosis of von Willebrand Disease. Blood 69, 1691–1695 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papageorghiou A. T. et al. Preeclampsia and COVID-19: results from the INTERCOVID prospective longitudinal study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 225, 289.e1–289.e17 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brosens I. A., Robertson W. B. & Dixon H. G. The role of the spiral arteries in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Annu (1972). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mody N. A. & King M. R. Platelet Adhesive Dynamics. Part II: High Shear-Induced Transient Aggregation via GPIbα-vWF-GPIbα Bridging. Biophys J 95, 2556 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker R. I. & Gralnick H. R. Effect of aspirin on platelet-von Willebrand factor surface expression on thrombin and ADP-stimulated platelets. Blood 74, 2016–2021 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mannes M. et al. Complement & platelets: Prothrombotic cell activation requires membrane attack complex induced release of danger signals. Blood Adv (2023) doi: 10.1182/BLOODADVANCES.2023010817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aiello S. et al. C5a and C5aR1 are key drivers of microvascular platelet aggregation in clinical entities spanning from aHUS to COVID-19. Blood Adv 6, 866–881 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner N. A. & Moake J. Assembly and Activation of Alternative Complement Components on Endothelial Cell-Anchored Ultra-Large Von Willebrand Factor Links Complement and Hemostasis-Thrombosis. PLoS One 8, e59372 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ercig B. et al. Conformational plasticity of ADAMTS13 in hemostasis and autoimmunity. J Biol Chem 297,(2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noone D. G. et al. Von Willebrand factor regulates complement on endothelial cells. Kidney Int 90, 123–134 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scully M. How to evaluate and treat the spectrum of TMA syndromes in pregnancy. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2021, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moatti-Cohen M. et al. Unexpected frequency of Upshaw-Schulman syndrome in pregnancy-onset thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 119, 5888–5897 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coppo P. & Joly B. S. Caplacizumab: A game changer also in pregnancy-associated immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura? Br J Haematol (2023) doi: 10.1111/BJH.18915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meri S. Complement activation in diseases presenting with thrombotic microangiopathy. Eur J Intern Med 24, 496–502 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Youssef L. et al. Complement and coagulation cascades activation is the main pathophysiological pathway in early-onset severe preeclampsia revealed by maternal proteomics. Sci Rep 11, 3048 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lokki A. I. & Heikkinen-Eloranta J. Pregnancy induced TMA in severe preeclampsia results from complement-mediated thromboinflammation. Hum Immunol 82, 371–378 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borodulin K. et al. Forty-year trends in cardiovascular risk factors in Finland. Eur J Public Health (2015) doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Triebwasser M. Excessive Complement Activation Due to Genetic Haploinsufficiency of Regulators in Multiple Human Diseases. Washington University in St.Louis, Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. (2015). doi: 10.7936/K7V69GR4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Purcell S. & Sham P. Genetic Power Calculator. Power 8, 2005–2008 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glusman G., Caballero J., Mauldin D. E., Hood L. & Roach J. C. Kaviar: an accessible system for testing SNV novelty. Bioinformatics 27, 3216–3217 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLaren W. et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics 26, 2069–2070 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from Professor Hannele Laivuori on reasonable request.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from Professor Hannele Laivuori on reasonable request.