Abstract

Noncoding genetic variants underlie many complex diseases, yet identifying and interpreting their functional impacts remains challenging. Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD), a polygenic neurodegenerative disorder, exemplifies this challenge. The disease is strongly associated with noncoding variation, including common variants enriched in microglial enhancers and rare variants that are hypothesized to influence neurodevelopment and synaptic plasticity. These variants often perturb regulatory sequences by disrupting transcription factor (TF) motifs or altering local TF interactions, thereby reshaping gene expression and chromatin accessibility. However, assessing their impact is complicated by the context-dependent functions of regulatory sequences, underscoring the need to systematically examine variant effects across diverse tissues, cell types, and cellular states.

Here, we combined in vitro and in vivo massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs) with interpretable machine-learning models to systematically characterize common and rare variants across myeloid and neural contexts. Parallel profiling of variants in four immune states in vitro and three mouse brain regions in vivo revealed that individual variants can differentially and even oppositely modulate regulatory function depending on cell-type and cell-state contexts. Common variants associated with LOAD tended to exert stronger effects in immune contexts, whereas rare variants showed more pronounced impacts in brain contexts. Interpretable sequence-to-function deep-learning models elucidated how genetic variation leads to cell-type-specific differences in regulatory activity, pinpointing both direct transcription-factor motif disruptions and subtler tuning of motif context. To probe the broader functional consequences of a locus prioritized by our reporter assays and models, we used CRISPR interference to silence an enhancer within the SEC63-OSTM1 locus that harbors four functional rare variants, revealing its gatekeeper role in inflammation and amyloidogenesis. These findings underscore the context-dependent nature of noncoding variant effects in LOAD and provide a generalizable framework for the mechanistic interpretation of risk alleles in complex diseases.

Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD), the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder worldwide, exhibits strong heritability1. Its genetic architecture comprises multiple components, including the strong influence of the APOE ε4 allele2, common variants with weaker effects, and rare variants. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS)3–6 have identified numerous common variants (minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 0.01) that are enriched for functions in immune cells, particularly microglia and macrophages. This genetic landscape implicates neuroinflammation and mirrors the broad observed failure of microglial functions in LOAD brains7,8: impaired surveillance9,10, reduced amyloid-β11,12 and tau clearance13,14, dysregulated injury response15,16, and altered inflammatory regulation17,18. Notably, top risk genes such as BIN1 and TREM2 encode proteins crucial for maintaining myeloid homeostasis; dysfunction in these genes perturbs processes like endocytosis19,20, lipid metabolism19,21, and cytokine signaling19,22, thereby accelerating neurodegeneration23,24. Human single-nucleus transcriptomic studies further delineate distinct microglial activation states, and several of these states display more prominent LOAD-associated gene expression signatures, suggesting state-specific genetic effects25,26. Although fine-mapping efforts are increasingly narrowing down GWAS signals27–31 in the immune context, pinpointing the exact causal variants and their functional mechanisms remains a major challenge.

In contrast to GWAS, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of 2,247 individuals from 605 multiplex LOAD families uncovered 13 loci with consistent association of rare variant (MAF < 0.01) clusters, such as CTNNA2, KIF2A, SYTL3, CLSTN2, NALCN, and FNBP1L, whose products are pivotal for synaptic function and neurodevelopment32.

This suggests that neuron-intrinsic genetic risk constitutes a previously underappreciated dimension of LOAD. Nevertheless, limited statistical power for individual rare variants within these clusters obscures the identity of the causal alleles, and their precise functional consequences therefore remain unknown. Thus, directly measuring the effects of individual rare alleles and benchmarking them against common variants is essential to establish their relative impact and underlying mechanisms. Furthermore, immune-versus-neural cell-type divergence underscores the importance of analyzing genetic variants in disease-relevant cell types and states. Consequently, there is a critical need for systematic, large-scale functional measurements that directly compare common and rare variants, coupled with detailed mechanistic interpretations in disease-relevant cellular contexts.

Both the GWAS and WGS studies suggest that LOAD is predominantly driven by noncoding variants3–6,32. Noncoding genetic variants contribute to the risk of many complex diseases by disrupting gene regulation, often through interference with transcription factor (TF) binding at cis-regulatory elements (CREs) such as enhancers and promoters33–35. The activity of these CREs can be highly cell-type-specific and even state-specific, shaped by the availability and dynamics of distinct TFs36–39. This specificity implies that the effects of genetic variants on CRE function, and consequently on disease risk, are likewise context-dependent40,41. LOAD GWAS variants show significant enrichment in microglia and macrophage enhancers, potentially disrupting immune enhancer activities42,43. A well-characterized CRE is the microglia-specific enhancer ~25 kb upstream of BIN1 that harbors the lead LOAD risk variant rs6733839. CRISPR-mediated deletion of this enhancer in human iPSC-derived microglia selectively lowers BIN1 mRNA and protein levels, suggesting rs6733839 may modulates LOAD risk by altering microglial BIN1 expression43. Although epigenomic modeling that integrates open chromatin, histone marks, and three-dimensional contacts now permits prediction of variant impacts on these CREs, current models still struggle to resolve the resulting transcriptional and cellular consequences because of the versatile, combinatorial nature of TF function.

Quantifying the functional consequences of non-coding genetic variation is intrinsically difficult: regulatory elements act in highly context-specific manner and typically elicit subtler phenotypic changes than coding mutations44. Massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs) overcome many technical barriers by coupling thousands of synthesized cis-regulatory elements (CREs) to barcoded reporter constructs, positioned either upstream or downstream of a minimal promoter, to measure transcription factor-driven enhancer activity45. Allelic MPRAs directly contrasting CREs that differ by a single nucleotide, now provide a robust, high-throughput read-out of allele-specific regulatory effects30,31,46–48. Traditional in vitro MPRAs achieve excellent transfection efficiency and statistical power, yet they only approximate—rather than fully replicate—the in vivo cellular identity of their target cell type. Recent in vivo tissue MPRAs, including our AAV-based systemic platform (sysMPRA)49, extended this paradigm to native contexts such as adult brain tissue, enabling measurement of regulatory dynamics within complex cellular environments49,50. Thoughtful selection of the experimental system therefore remains critical for accurately inferring variant function. Additionally, while MPRA effectively quantifies variant impacts on transcription, elucidating downstream effects on endogenous gene expression remains limited. To bridge this gap, methods such as CRISPR interference (CRISPRi)51 and CRISPR-based excision43 have been employed to perturb enhancers, enabling profiling of affected gene expression implicated in LOAD, though still at a relatively limited scale28,30,43. Collectively, these experimental advances establish a versatile toolkit for disentangling the consequences of regulatory variants across diverse cellular contexts.

Complementing these experimental approaches, computational methodologies continue to evolve to interpret how genetic variants influence context- and cell-type-dependent gene expression. Early computational frameworks relied on position weight matrices representing individual TF motifs52. Over the past decade, sequence-to-function models such as DeepSEA53, Enformer54, ChromBPNet55, DeepAllele56 and GET57 have advanced the field by using deep neural networks to learn combinatorial regulatory codes directly from DNA. Although predicting gene expression from sequence alone remains difficult, these architectures now deliver state-of-the-art accuracy on chromatin-feature prediction. Within this deep-learning landscape, convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—neural networks that apply learnable filters to scan sequence features such as TF motifs—continue to excel at regulatory genomics tasks, including cell-type-specific enhancer classification58 and genetic variant effect inference27. Although transformer-based, self-supervised “genomic large language models” aspire to achieve zero-shot prediction by learning the “DNA language”—that is, by modeling genome-wide sequence context and long-range dependencies—ab initio–supervised CNNs and their derivatives54 currently deliver superior predictive performance, greater computational efficiency, and—crucially—enhanced interpretability for uncovering underlying biology59,60. Recently, multimodal foundation models such as AlphaGenome61 have emerged, aiming to unify multiple biological data modalities for predicting variant effects; however, these larger models remain limited in their ability to capture cell-type-specific and state-specific nuances, a task at which simpler CNN architectures still outperform62,63. Together, these advances in deep learning provide a powerful, yet still evolving, framework for mechanistically informed prediction of variant effects on gene regulation.

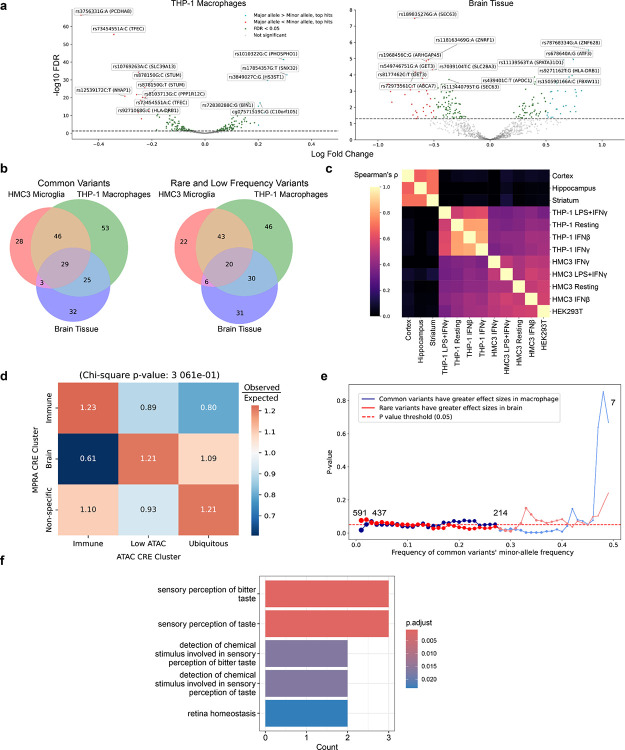

To clarify how non-coding risk alleles shape LOAD in immune and neural contexts, we curated 599 LOAD-associated variants (186 rare variants, MAF < 0.01; 106 low-frequency variants, 0.01 ≤ MAF < 0.05; and 307 common variants, MAF ≥ 0.05) from GWAS and WGS, selecting those that overlap open chromatin in microglia, macrophages, or neurons (Fig. 1a). Variants were grouped by chromatin accessibility in resting and activated immune cells into immune-specific enhancers, ubiquitously active elements, and regions with limited accessibility (Fig. 1b); most reside in intronic, intergenic, or promoter-proximal positions, consistent with distal-enhancer activity.

Fig. 1 |. Integrative framework for identifying context-dependent regulatory effects of LOAD-associated variants.

(a) Manhattan plot of 599 prioritized late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) variants, comprising common and rare variants from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of familial LOAD cases. Variants were selected based on their statistical association strength and overlap with open chromatin regions in brain and immune cell types.

(b) Variants were mapped to regions classified by chromatin accessibility annotations across immune and neuronal cell types and states, derived from bulk and single-nucleus ATAC-seq (Supplementary Table 3), then grouped as immune-specific cis-regulatory elements (CREs), ubiquitously accessible CREs, or regions with low accessibility. The accompanying bar plot summarizes the genomic context of these variants, showing the percentage that fall within 1–5 kb to transcription start site (TSS), promoter, 5’ untranslated regions (5’ UTR), exons, introns, 3’ untranslated regions (3’ UTR), and intergenic regions.

(c) Overview of the experimental and computational pipeline for functional interpretation of noncoding variants. Massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs) in multiple cell types and states validate regulatory activity and motif context. Convolutional neural networks trained on multi-cell-type, multi-state ATAC-seq data identify putative regulatory variants and transcription factor motifs. CRISPRi perturbation of the SEC63-OSTM1 locus followed by RNA-seq reveals downstream gene expression and pathway changes, linking regulatory variants to LOAD-relevant molecular mechanisms.

In this study, we established an integrated experimental and computational framework that combines context-dependent in vitro and in vivo MPRA, interpretable CNN models, and CRISPRi perturbation (Fig. 1c). Leveraging a validated THP-1 macrophage model that recapitulates canonical immune states together with mouse brain tissue from the cortex, hippocampus, and striatum that captures native neural context, this approach (i) quantifies the regulatory impact of hundreds of LOAD-associated variants, (ii) prioritizes functionally impactful alleles, (iii) dissects their cell-type- and state-specific mechanisms, and (iv) enables in-depth functional analysis of a disease-risk–associated enhancer harboring functional rare variants. Together, this framework connects noncoding genetic variation to context-dependent regulatory mechanisms and, ultimately, to the key genes and molecular pathways involved in LOAD.

Results

Characterization of THP-1 macrophages as an innate-immune-cell model for LOAD

Mononuclear phagocytes, including microglia, macrophages, and monocytes, are implicated in the genetic predisposition to LOAD5,6,27,42,64. Microglia, the resident macrophages of the central nervous system, continuously survey the brain parenchyma9,10, clear amyloid-β (Aβ)11,12 and tau aggregates13,14, respond to neural injury15,16, and modulate neuroinflammation17,18, all of which are processes dysregulated in LOAD7,8. Although microglia are the primary brain-resident immune cells, perivascular macrophages and recruited monocyte-derived macrophages also participate in plaque clearance and secrete proinflammatory cytokines65–68. In microglia-depleted mouse models of LOAD, it was found that monocyte-derived macrophages repopulated the entire brain and could functionally substitute microglia, marked by amyloid plaque association as well as Trem2-expression69. Moreover, peripheral inflammation could induce microglia immune memory through epigenetic reprogramming, modifying LOAD pathology70. Together with microglia, peripheral immune cells are also increasingly recognized as LOAD modulators27,71.

To model mononuclear phagocytes and LOAD-associated microglial states25,26, we adopted THP-1 cells as a macrophage model, leveraging their transcriptomic similarity to primary microglia and macrophages72 and their ease of genetic and pharmacological manipulation. In contrast, HMC3 microglia showed limited transcriptomic resemblance to primary microglia and were therefore used only as a secondary model in this study. Using chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) and transcriptome profiling (RNA-seq), we characterized THP-1 macrophages throughout differentiation and upon stimulation with interferon-β (IFN-β), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), or lipopolysaccharide plus IFN-γ (LPS+IFN-γ), modeling antiviral, M1-polarized, and hyperinflammatory states, respectively (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Upon differentiation from monocytes, THP-1 macrophages demonstrated upregulated immune responses and reduced cell-cycle activity, confirming successful differentiation (Extended Data Fig. 1a). IFN-β and IFN-γ treatments predominantly increased chromatin accessibility at promoters and enhancers, activating gene expression, whereas LPS+IFN-γ triggered broader chromatin remodeling that both opened and closed regulatory regions, leading to concurrent gene activation and repression (Extended Data Fig. 1b,c, 2a,c). IFN-β activated viral defense and leukocyte chemotaxis pathways; IFN-γ induced genes involved in bacterial/lipid sensing and protein trafficking; LPS+IFN-γ not only elicited robust interferon responses but also pronounced inflammatory responses (Extended Data Fig. 1d, 2b). Marker genes for microglia and macrophages (e.g., TREM2, IBA1) remained robustly expressed and exhibited state-specific modulation in each state (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Previous studies have shown that THP-1 macrophages exhibit transcriptomic similarity to both primary and stem-cell-derived microglia72; we further demonstrate that they also share epigenomic profiles with stem-cell-derived microglia (Extended Data Fig. 1e). These results demonstrate that we are able to capture gene expression and open chromatin profiles associated with different inflammatory states of mononuclear phagocytes.

Human single-nucleus transcriptomic studies of post-mortem brain tissue and cortical biopsies from living individuals have identified ~12 distinct microglial states in LOAD25,26. We next examined how THP-1 macrophages under different treatments might recapitulate these states. LPS+IFN-γ treatment induced marker genes of inflammatory microglial states identified in human post-mortem brains, MG10, MG2, and MG8 (ordered by descending inflammatory strength). Marker genes of the MG10 state, indicative of strong inflammation, exhibited the highest upregulation (Extended Data Fig. 2e). Inflammatory microglia are closely associated with amyloid plaques25,26. Sun et al. demonstrated that amyloid-β fibrils induce inflammatory responses in iPSC-derived microglia25. Notably, LPS+IFN-γ stimulation of THP-1 macrophages recapitulated the late (24 h) inflammatory response induced by amyloid-β fibrils (Extended Data Fig. 2f), demonstrating the pathological relevance of LPS+IFN-γ-driven inflammation. Disease-associated microglia (DAM) signatures, distributed across MG3, MG4, and MG10, were all upregulated by LPS+IFN-γ stimulation, further underscoring its disease relevance (Extended Data Fig. 2e). Additionally, antiviral state marker genes (MG11) were robustly upregulated by both IFN-β and LPS+IFN-γ, consistent with LPS-mediated endogenous IFN-β production (Extended Data Fig. 2e). These findings reflect that the THP-1 macrophages can recapitulate several key microglial states observed in the brains of LOAD human subjects.

Inflammatory and antiviral microglial states in human brains are enriched for LOAD GWAS variants25,26. We performed stratified linkage disequilibrium score regression (S-LDSC) and observed significant enrichment of LOAD GWAS variants in open chromatin from THP-1 macrophage states, comparable to that in primary microglia, macrophages, and iPSC/hESC-derived microglia, whereas no significant enrichment was detected in neurons (Extended Data Fig. 1f). Collectively, these data illustrate that THP-1 macrophages can recapitulate key microglial marker gene expression, activation states, and epigenomic features linked to LOAD, providing a practical model for dissecting LOAD-associated immune mechanisms.

Context-dependent MPRA identified LOAD-risk enhancers across neural and immune contexts

To systematically evaluate common and rare LOAD variant effects on cis-regulatory activities, we designed MPRA constructs with barcoded 227-bp synthetic CREs carrying reference or alternate alleles downstream of a minimal promoter, which captures enhancer-like activities (Fig. 2a). CREs were open chromatin peak-centered (variants close to open chromatin peak summit), variant-centered (distal variants), or motif-shuffled (disrupting local TF motifs), providing multiple readouts of variant effects (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Table 3). We assayed the library of 1600 CREs in four immune states (resting, IFN-β, IFN-γ, LPS+IFN-γ) by transfecting both THP-1 macrophages and the alternative microglia model HMC3, with HEK293T cells included as a non-immune control. To capture neural activity in vivo, the same library was delivered noninvasively to the brains of four mice via retro-orbital injection of AAV.PHP.eB virus. We dissected out and measured the regulatory activity of CREs in three brain regions: cortex, hippocampus, and striatum (Fig. 2b). Using median absolute deviation (MAD) scores as a measure of enhancer activity, we found high reproducibility between replicates (Pearson’s r ≈ 0.8–0.9 in vitro, r ≈ 0.6–0.7 in vivo; Extended Data Fig. 3a). Activity profiles clustered by cell type, strongly correlated within immune or neural contexts but moderately across them, highlighting distinct regulatory landscapes and additional interspecies differences (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Table 4).

Fig. 2 |. Context-dependent MPRA identified LOAD-risk enhancers across neuronal and immune contexts.

(a) Schematic of the massively parallel reporter assay (MPRA) design. Synthetic 227-bp candidate cis-regulatory elements (CREs) downstream of a minimal promoter that drives the expression of mCherry, each tagged with unique barcodes for quantification. CREs were either open chromatin peak-centered on or variant-centered, with additional motif-disrupted constructs generated by sequence shuffling around selected variants

(b) Reporter libraries were systemically delivered in vivo to the mouse brain tissues (cortex, hippocampus, and striatum) via AAV.PHP.eB viral retro-orbital injection, and transfected in vitro into THP-1 macrophages and HMC3 microglia-like cells under resting, IFN-β, IFN-γ, and LPS+IFN-γ conditions.

(c) CRE enhancer activities show both cell-type- and immune-state-specific patterns. MPRA activity is quantified using cDNA:DNA ratios and modeled via median absolute deviation (MAD) scores (MPRAnalyze quantitative analysis, see methods). MAD scores reveal strong correlations among similar cell types and conditions (Pearson correlation), whereas LPS+IFN-γ stimulation yields more distinct activity profiles and lower correlations with other immune states. This figure mixes scatter plots, histograms of MAD scores, and a heatmap of MAD score correlations.

(d) Immune and ubiquitous CREs (defined in Fig. 1b) exhibit higher activity in THP-1 macrophages, and immune CREs also display elevated activity in brain tissue (P.MAD, MPRAnalyze quantitative analysis).

(e) Coefficients of HOCOMOCO transcription factor motifs in elastic net models that predict MAD scores of THP-1 macrophage MPRA or brain tissue MPRA. Regression outliers highlighted in red have residuals greater than 3-fold the standard deviation.

(f) Clustering of cell-type-specific and broadly active enhancers. The heatmap depicts Z-normalized reporter transcription activity for each candidate CRE (columns) across the assayed cell types/conditions (rows). For every enhancer, reporter activity was quantified as the mean MAD score of its reference and alternate-allele constructs, then standardized within each cell type by dividing by that cell type’s standard deviation to yield a Z-score. Only enhancers with |Z| ≥ 1.65 (≈ 95th percentile) in at least one context are shown, highlighting elements with strong cell-type-specific or broadly shared activity. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Euclidean distance, average linkage) organizes both enhancers and cell types; warmer colors indicate higher activity and cooler colors lower activity.

(g) CRE responses to LPS+IFN-γ stimulation in THP-1 macrophages; most responsive CREs exhibit repression upon stimulation (FDR < 0.05, MPRAnalyze comparative analysis, see methods). Volcano plots show the log fold change of CRE enhancer activities in stimulated THP-1 macrophages versus resting THP-1 macrophages at the X-axis and −log10 (FDR) at the Y-axis.

(h) Genes proximal to LPS+IFN-γ-responsive CREs enriched in immune activation pathways (FDR < 0.05, fast gene set enrichment analysis).

Approximately 13% of tested CREs (P.MAD ≤ 0.05) showed significant enhancer activity in macrophages or brain tissue (Extended Data Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 4). Immune and ubiquitous CREs were more frequently active in THP-1 macrophages, consistent with ATAC-seq annotations, whereas in brain tissue, immune but not ubiquitous CREs retained activity (Fig. 2d). Many of those ubiquitous CREs were at promoters, which may not operate as efficiently in assays in which the candidate CRE is cloned in downstream of the TSS73,74. This assay limitation likely explains why immune, rather than ubiquitous, CREs appeared more active in brain tissue. Elastic net regression on TF motifs explained a substantial proportion of variance in enhancer activities (R2 = 0.90, P = 0.001, in vitro; R2 = 0.48, P = 0.001, in vivo; permutation test) despite higher noise in in vivo measurements, underscoring the central role of motif composition in shaping enhancer activity; notably, TFs linked to neural development and differentiation, including MEF2B, CRX, CLOCK, NR2E1, and POU3F4, emerged as key contributors to brain enhancer specificity (Fig. 2e). We further identified both cell type-specific as well as broadly active enhancer (Fig. 2f); for example, a distal enhancer at the BIN1 locus (rs13025765/rs13025717) was selectively active in macrophages, while a segment of the NRN1 promoter (rs192104059) showed brain-specific activity.

Among interferon stimulations, LPS+IFN-γ (hyperinflammatory) produced the most distinct enhancer responses. In THP-1 macrophages, 146 CREs (10%) showed significant activity changes in response to LPS+IFN-γ treatment, nearly half of which overlapped differentially accessible chromatin regions, while IFN-β and IFN-γ alone affected only three and one CREs, respectively (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Table 5). Similarly, in HMC3 microglia, 97 CREs responded to LPS+IFN-γ (Supplementary Table 5). Notably, LPS+IFN-γ induced widespread enhancer repression while activating only a small subset of enhancers, highlighting the role of repressive TFs in inflammatory responses (Fig. 2g). The nearest genes to these LPS+IFN-γ-responsive CREs were enriched in immune activation pathways, underscoring their functional relevance (Fig. 2h). Motif analysis revealed that the AP-1 family motif FOSL2 and ELK1 gained positive regulatory influence under LPS+IFN-γ, whereas NRF2 (NFE2L2) acted as a negative regulator, pointing to dynamic TF remodeling during inflammation (Extended Data Fig. 3c). These results reveal that LOAD risk variants converge on cell type-specific and inflammation-sensitive enhancers, providing reliable measurement of their regulatory effects. Our MPRA assay provides a comprehensive annotation of which LOAD-associated variants containing CREs are active across different brain regions and monocyte cell states.

Context-dependent MPRA identified regulatory LOAD variants across immune and neural contexts

Having mapped a high-confidence atlas of enhancer activity across immune and neural contexts, we next asked how LOAD variants modulate those activities. Screening 599 candidate variants with 855 pairs of constructs, we identified expression-modulating variants (emVars; FDR < 0.05) in THP-1 macrophages and HMC3 microglia under four immune states, and in vivo in the cortex, hippocampus, and striatum (Extended Data Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table 6). Of these, 104 emVars were shared between THP-1 macrophages and brain tissue; 188 were exclusive to THP-1 (not detected in brain tissue, though possibly present in HMC3); and 72 were unique to brain tissue (not detected in THP-1, though possibly present in HMC3) (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Among emVars with significant effects in both contexts, approximately 48% exhibited opposite allelic directions, reflecting distinct modes of regulatory activity across tissues. The variants’ effects displayed cell-type-specific patterns (Extended Data Fig. 4c). When aggregated across immune states or brain regions, emVars within active enhancers segregated into brain-specific, immune-specific, and nonspecific clusters (Fig. 3a), underscoring a sharp cell-type divergence in regulatory impact. Consistent with previous open chromatin partitioning (Fig. 1b), immune-specific emVars were enriched in immune CREs, brain-specific emVars preferentially resided in regions of low chromatin accessibility, and nonspecific emVars were overrepresented in ubiquitous CREs, although these trends were not statistically significant (χ2 test, p = 0.3; Extended Data Fig. 4d).

Fig. 3 |. Allele frequency, cellular context, and immune state modulate TF-motif-driven variant effects on enhancer activity.

(a) Clustering of LOAD variants with significant impacts (FDR < 0.05, MPRAnalyze comparative analysis) on active enhancers (P.MAD < 0.1, MPRA quantitative analysis). Brain-specific, immune-specific, and nonspecific effects were observed.

(b) Comparison of MPRA-derived effect sizes between rare (minor allele frequency [MAF] < 0.01) and common (MAF ≥ 0.29) variants in THP-1 macrophages and mouse brain tissue. Common variants exert stronger effects in macrophages, whereas rare variants show greater transcriptional consequences in the brain (P-value, one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test).

(c) TF motif-enrichment of the sequence context around significant expression-modulating variants (emVars) highlights distinct TF families in each cell type. Motif analysis was performed using AME (MEME Suite) to identify TF families enriched in the 25 bp sequence context surrounding MPRA-validated emVars (q < 0.05), separately for each cell type. Results are compared to motif enrichment in cell-type-specific ATAC-seq peaks from THP-1 macrophages and brain tissues (Cortex and Striatum). Similar TF family enrichment patterns were observed in both datasets, with cell-type-specific TFs identified in ATAC-seq showing comparable enrichment around MPRA-significant variants in the corresponding cell type.

(d) Comparison of CRE enhancer activities between constructs harboring single-nucleotide variants and those with shuffled motif sequences. Motif disruption causes significantly stronger transcriptional perturbations than SNVs in several key transcription factor (TF) families, including STAT, IRF, AP-1, MEF2, and SPI1 (FDR ≤ 0.05, one-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test). ns, not significant (FDR > 0.05)

(e) Disrupted motif contexts show directional regulatory effects: disruptions that decreased transcription mark the motif as an activator, whereas disruptions that increased transcription mark it as a repressor. Motifs such as IRF, SPI1, and STAT often correlate with increased transcriptional activity, suggesting their roles as activating factors.

(f) Variants exhibit distinct transcriptional responses under hyperinflammatory state (LPS+IFN-γ) (FDR < 0.05, MPRAnalyze comparative analysis). The Y and X axes represent the log fold change of CRE enhancer activities of the major allele versus the minor allele in LPS+IFN-γ-treated and resting THP-1 macrophages, respectively.

This divergence prompted us to investigate whether the genetic origins of LOAD variants are associated with their observed regulatory effects. Common LOAD variants identified by GWAS are enriched in microglial enhancers3–6,29,42,43,75, whereas rare variants from patient-family sequencing studies often map to neural-development and synaptic-plasticity genes32. We therefore tested the hypothesis that common variants are more likely to exert effects in immune cells, whereas rare variants have greater functional consequences in neural contexts. Consistent with this prediction, in THP-1 macrophages, common variants produced larger expression changes than rare variants, whereas in brain tissue, this pattern was reversed (Fig. 3b), with the strongest effects observed among the most common variants (MAF ≥ 0.29; Extended Data Fig. 4e). Although modest, our findings support a model where common LOAD variants primarily influence immune regulation, while rare variants more frequently modulate neural functions.

To investigate the mechanisms driving this cell-type divergence, we next examined TF-motif enrichment near emVars, comparing it directly to motif enrichment within open chromatin regions in THP-1 macrophages and brain tissue. Motifs enriched in open chromatin were also preferentially enriched near emVars within the same cellular context, with consistent representation across TF families. Brain-active emVars were predominantly associated with motifs from TF families involved in neural development and function, including TALE-type homeodomain, HOX-related, NK-related, and Fos-related families (Fig. 3c). In contrast, emVars active in THP-1 macrophages were enriched for immune-related TF families such as ETS-related, IRF, STAT, and NF-κB. Together, these analyses highlight distinct, cell-type-specific regulatory codes through which LOAD-associated variants exert their effects.

We next directly tested whether the TF-motif contexts surrounding these variants functionally modulate enhancer activities. Given that LOAD variants are often predicted to disrupt immune-related TF motifs, we analyzed a set of motif-shuffled enhancers in which a 25-bp window surrounding each variant was fully shuffled to disrupt the predicted immune-related TF-motif context, a design we refer to as motif-context shuffling. Because single-nucleotide variants typically weaken, rather than abolish, TF-binding sites, we hypothesized that complete motif ablation would elicit larger transcriptional shifts. In both THP-1 macrophages and HMC3 microglia, most motif-context shuffling events caused significant disruption of enhancer activity (FDR < 0.05, Supplementary Table 7) and produced markedly larger changes in reporter expression than single-nucleotide substitutions, with the strongest effects observed at motif contexts containing STAT, MEF2, IRF, AP-1, and SPI1 motifs (FDR < 0.05, Fig. 3d). Motif-context shuffling either increased or decreased transcription, though certain TF-motif contexts showed consistent directional biases. For example, IRF-, STAT-, and AP-1-related motif contexts preferentially decreased transcription upon disruption in THP-1 macrophages, highlighting their roles as transcriptional-activating contexts (Fig. 3e). These findings provide strong evidence that variants are associated with functionally active TF-motif contexts.

TFs involved in immune-signaling pathways, such as the interferon response, are often transiently activated; thus, variants disrupting these TF-binding sites may exert regulatory effects only under specific immune conditions. To explore this possibility, we analyzed variant effects separately in antiviral (IFN-β), M1-polarized (IFN-γ), and hyperinflammatory (LPS+IFN-γ) states in both THP-1 macrophages and HMC3 microglia. We detected significant state-specific emVars (FDR < 0.05) in all conditions except IFN-β-stimulated HMC3 cells. Under hyperinflammatory stimulation, we identified seven state-specific emVars in THP-1 macrophages and four in HMC3 cells (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Table 8). Notably, rs10838702-T (SPI1) and rs17515931-T (CLU) reduced transcription exclusively under hyperinflammatory conditions, whereas rs62427420-G (SEC63) reduced transcription only in resting cells. Several variants exhibited more complex patterns: rs73972710-T (CTDP1), rs73000577-C (UBA5), and rs636317-C (MS4A4E) increased transcription in both resting and stimulated states, but showed stronger activation upon stimulation, whereas rs549746751-A (GET3) exerted opposing effects depending on the immune state. These examples reflect regulatory scenarios in which variants disrupt TF binding that is active only in a specific state, alter the strength of binding in a state-dependent manner, or engage distinct TFs acting on the same sequence under different immune conditions.

In summary, our MPRA identifies both cell-type-specific and immune-state-specific effects of LOAD-associated variants on enhancer activity. Context-dependent disruption of regulatory activity is associated with key TF-binding motifs and with the variant’s allele frequency (common versus rare).

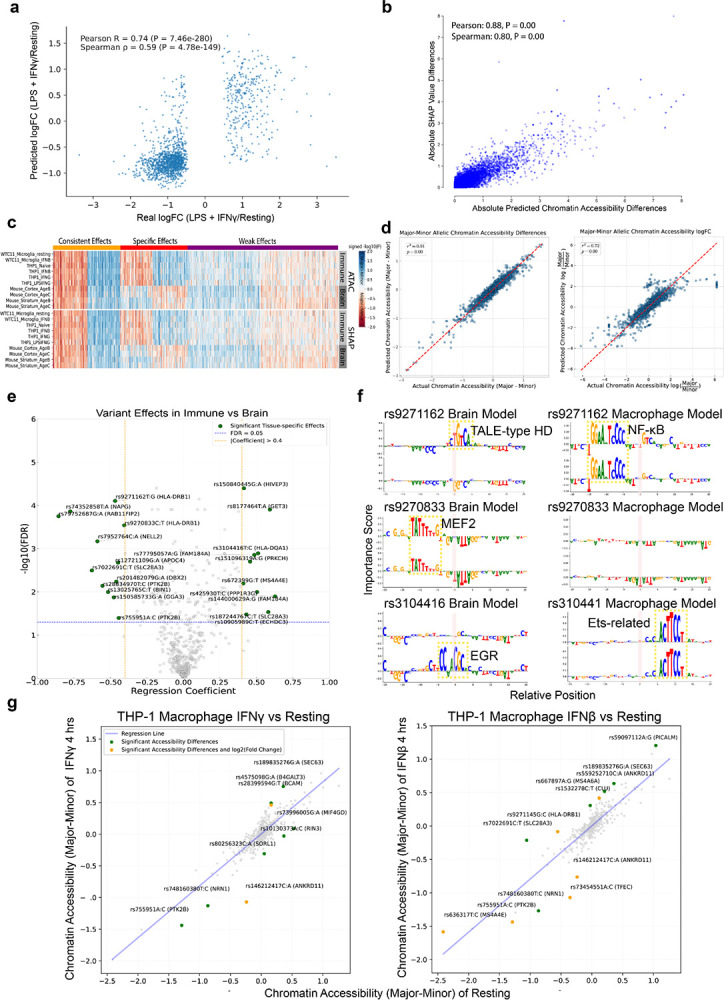

Deep-learning models interpret cell-type- and immune-state-specific variant effects

To interpret how LOAD genetic variants influence regulatory codes in MPRA, we trained CNN regression models on ATAC-seq data from multiple cell types, including stimulated and unstimulated THP-1 macrophages, hESC/iPSC-derived microglia, THP-1 monocytes, mouse cortex and striatum, and HEK293(T) cells. These models accurately predicted chromatin accessibility in holdout data from matched or related cell types (Spearman’s ρ ≈ 0.8), while predictions across divergent cell types yielded moderate performance (Spearman’s ρ ≈ 0.5), highlighting the cell type specificity of the regulatory codes they captured (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4 |. Machine-learning models interpret cell-type- and state-specific regulatory effects of LOAD variants.

(a) Convolutional neural network (CNN) models are trained on ATAC-seq data from multiple immune and neuronal cell types and states to predict chromatin accessibility. These models achieve high accuracy on closely related cell types (Spearman’s ρ ≈ 0.8) and moderate performance across more divergent types (ρ ≈ 0.5), indicating context specificity.

(b) TF-MoDISco motif analysis identifies cell-type- and state-specific transcription factor (TF) motifs based on SHAP importance scores from each model’s predictions (q-value < 0.05). These motifs form combinatorial modules that collectively yield distinct regulatory signatures.

(c) Models trained in immune versus neuronal contexts differentially predict accessibility of LOAD variant-containing sequences, distinguishing immune-specific, ubiquitous, and low-accessibility regions. Predictions from different models are aggregated: macrophage/microglia models (THP-1 macrophages, iPSC-derived microglia, and hESC-derived microglia) and brain-region models (cortex and striatum).

(d) The 50 variants predicted to most strongly alter chromatin accessibility induce markedly larger transcriptional changes in MPRA than the 50 variants predicted to have minimal impact (one-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

(e) Integrating predicted accessibility and SHAP scores identifies top variants that disrupt CTCF motifs or exert immune-specific and neuron-specific effects. P-values calculated based on differences in predicted chromatin accessibility and SHAP values between major and minor alleles relative to cell-type-specific null distributions.

(f) Linear regression of allele-specific effect sizes across paired cell-type models pinpoints variants with significant cell-type-selective activity (FDR < 0.05). Two patterns emerge: (i) magnitude-shift variants exert the same directional effect in immune and neuronal cells but with different strengths, and (ii) direction-switch variants flip between activation and repression across the two lineages. emVars detected in THP-1 macrophage MPRA, brain MPRA, or both are annotated with triangles, squares, and asterisks, respectively.

(g) Linear regression of allelic effect sizes in immune-state-specific models shows variants with enhanced or diminished regulatory effects in the hyperinflammatory state (LPS+IFN-γ, FDR < 0.05).

(h) Condition-specific regulatory variants. rs73972710 (C:T) at CTDP1—the major C allele forms a repressive ZBTB-family motif that dampens transcription in resting cells, whereas the T allele disrupts the motif and lifts repression. Under hyperinflammatory conditions, chromatin opening around the major allele masks its resting-state repression, reducing allelic differences. SHAP logos visualize the motif gains and losses that drive these state-specific effects.

Using SHAP76-based importance scores and TF-MoDISco77, we show that the models learned key cell type-specific TF motifs. Immune-related motifs (SPI, C/EBP, RUNX) were enriched in macrophage and microglia models, while neural motifs (EGR, MEF2, RFX) were enriched in brain models (FDR < 0.05; Fig. 4b). Only models trained on stimulated cells learned immune state-specific motifs, with IRF, NF-κB, CREB/ATF, and BATF promoting chromatin accessibility, and ZEB reducing accessibility in interferon-treated cells. To dissect TF roles in hyperinflammatory responses, we trained a model specifically on differentially accessible chromatin regions from LPS+IFN-γ-treated THP-1 macrophages (Extended Data Fig. 5a). This model revealed NF-κB, IRF/STAT, and CTCF motifs as drivers of chromatin opening, while, surprisingly, SPI and C/EBP motifs were linked to chromatin closure (Fig. 4b). SPI1 (PU.1) was previously found to be a microglial transcriptional repressor in late-stage LOAD78 that is marked by neuroinflammation79, suggesting a potential repressive role in hyperinflammatory responses. Together, these results demonstrate that the models successfully learned distinct transcription factor codes that underlie cell type- and state-specific patterns of chromatin accessibility.

We evaluated the models on LOAD variant-containing sequences in the MPRA library and found that immune-trained models discriminated against immune CREs from low-ATAC sequences, while brain-trained models favored ubiquitous over immune CREs, reflecting distinct regulatory codes (Fig. 4c). The models recapitulated the TF motif enrichments seen in the matched ATAC-seq datasets, capturing both cell-type- and state-specific activity as well as elements inducible by LPS-plus-IFN-γ stimulation (FDR < 0.05; Extended Data Fig. 3d,e). Overall, these findings highlight that these models capture the generalizable regulatory codes, making them valuable tools for interpreting cell type- and state-specific enhancer function.

We then applied in silico mutagenesis to assess allelic effects of LOAD variants (Supplementary Table 9), facilitated by generating a null distribution from negative sequences and estimating prediction uncertainty via Monte Carlo dropout in our CNN. The models effectively distinguished variants with strong versus weak regulatory effects in MPRA assays performed in THP-1 macrophages, with a similar trend observed for brain tissue, demonstrating concordance between predictions and experimental data (Fig. 4d). By integrating predicted accessibility changes and SHAP importance scores, which were significantly correlated (Spearman’s ρ = 0.8; Extended Data Fig. 5b), the models identified variants that exhibit effects across cell types as well as variants with effects biased toward the immune or neural contexts (P < 0.1; Fig. 4e). Among the strongest outliers were rs636317 (MS4A4E) and rs755951 (PTK2B), both of which alter CTCF motifs. Immune-biased variants were identified near EPHA1, MS4A4A, BIN1, PICALM, and PTK2B, all key microglial regulators, while brain-biased hits included variants near SORL1, SNAP25, and NAPG, central to synaptic vesicle trafficking and amyloid precursor protein processing. Interestingly, some variants showed consistent directional effects across cell types, while others displayed opposing effects (Extended Data Fig. 5c). These results suggest that the models can identify significant regulatory variants that align with MPRA data and capture their context-dependent effects.

To determine cell-type-specific effects of each allele, we performed linear regression on predicted allelic differences, including cell type (immune versus neural) as a covariate to isolate context-dependent effects. This analysis highlighted two major classes of variants: (i) those with a consistent direction but stronger effects in one cell type, and (ii) those with opposite effects between immune and neural contexts (Fig. 4f, Extended Data Fig. 5d, 5e). Surprisingly, common variants in HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQA1, typically associated with microglial function, showed stronger predicted effects in brain tissue. For example, exclusively in the neural context, the minor G allele of rs9271162 (HLA-DRB1) disrupts a TALE-type homeodomain binding site; the minor T allele of (HLA-DRB1) generates a repressive motif that reduces MEF2 binding; and the minor C allele of rs3104416 (HLA-DQA1) creates an EGR motif (Extended Data Fig. 5f). Notably, a substantial subset of these variants overlap with MPRA-validated emVars. For example, rs13025765 (BIN1), identified as an emVar in both THP-1 macrophages and brain tissue, increases accessibility in immune cells but decreases accessibility in the brain when the minor T allele is present. Together, these findings highlight the power of our models to resolve allele-specific regulatory effects with cell-type precision.

We next explored immune state-specific effects with models trained on LPS+IFN-γ-, IFN-γ-, IFN-β-treated, or resting THP-1 macrophages (Fig. 4g, Extended Data Fig. 5g). Variants with robust context-specificity were identified, such as rs13025765 (BIN1), which showed stronger effects under LPS+IFN-γ stimulation compared to the resting state, and rs189835276 (SEC63), which displayed stronger effects under all three interferon-activated conditions. Models trained on LPS+IFN-γ-responsive sequences provided mechanistic insight (Extended Data Fig. 3d). For example, the resting-state model predicted that for rs73972710 (CTDP1), the major C allele forms a repressive ZBT motif at rest, while the minor T allele disrupts this motif and increases transcription; upon stimulation, the model revealed a chromatin-opening advantage for the major allele, masking the resting-state repression and reducing allelic differences, matching MPRA findings (Fig. 4h; Fig. 3f). These examples demonstrate how the models uncover the regulatory mechanisms underlying the state-specific effects observed in experimental data.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that LOAD risk variants exhibit dynamic, cell type- and immune state-specific regulatory effects and highlight the utility of deep learning models for predicting and interpreting variant-mediated disruptions in gene regulation.

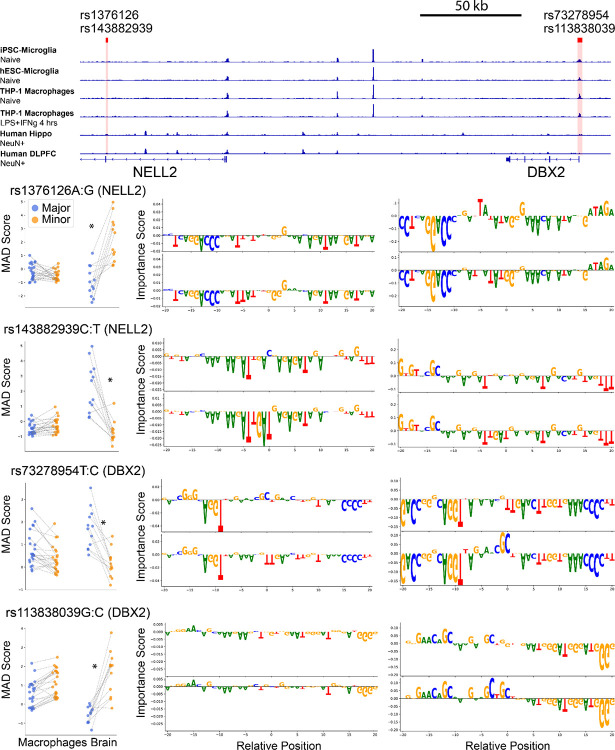

Functional regulatory LOAD variants

By examining the overlap between MPRA data and machine-learning predictions, we found that both rare and common emVars predicted by models are distributed across THP-1 macrophages and brain tissue, forming “hotspots” where multiple variants converge within the same locus to modulate gene expression (Fig. 5a). Within a given locus, certain minor alleles enhance transcription, whereas others attenuate it, highlighting the complexity of gene regulation in these systems. Two previously uncharacterized hotspots, SEC63-OSTM1 and NELL2-DBX2, were particularly enriched for rare variants with pronounced allelic effects in both macrophages and brain tissues; variants in a NELL2 intron were active exclusively in brain tissue (Extended Data Fig. 6). The immune-associated BIN1 locus, the second-strongest genetic signal for LOAD risk3–6, also emerged among the top hits. Although the disease risk is most often attributed to the coding ε4 allele of APOE, we observed potent noncoding variant effects at the APOE-APOC1 and APOC2 loci in both neural and immune contexts. Together, these findings illustrate how multiple distinct variants within the same locus can reshape the regulatory landscapes in a context-dependent manner, providing new insights into LOAD-associated genetic mechanisms.

Fig. 5 |. Functional regulatory variants.

(a) Genome-wide map of rare, low-frequency, and common expression-modulating variants (emVars) that simultaneously perturb transcription (MPRA) and chromatin accessibility (model predictions). Spatial clustering of these dual-effect alleles marks convergent regulatory hotspots, loci harboring multiple functionally active variants. Dots are colored by the direction of the transcriptional effect (red, minor < major; blue, minor > major). Variants shown satisfy FDR < 0.05 in the MPRA allelic comparison, and |log2FC| > 0.1 and FDR < 0.01 in predicted accessibility differences.

(b) Proposed mechanistic model illustrating how genetic variants modulate transcription via multiple mechanisms. Variants can disrupt or create transcription factor (TF) motifs, alter local TF binding affinity, or influence competitive interactions among TFs, collectively shaping transcriptional output. Motif shuffling abolishes local TF binding, clarifying variant mechanisms.

(c) Criteria-based selection of functional causal variants from MPRA data, categorized by higher or lower transcriptional activity of the major allele relative to the minor allele in THP-1 macrophages, HMC3 microglia-like cells, and mouse brain. Red: variants supported by motif shuffling. Bold: variants predicted to significantly alter chromatin accessibility (FDR < 0.01, two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test on Bayesian predictions using Monte Carlo dropout; logFC accessibility difference magnitude > 0.1).

Integrating multidimensional measurements of genetic variant effects, sequence-level regulatory activity, and motif context function, we synthesized a mechanistic model of regulatory variant actions (Fig. 5b). Variants can (i) destroy or create a core TF site, (ii) fine-tune the strength of adjacent TF motifs, or (iii) re-balance competition among neighboring activators and repressors; motif shuffling represents the extreme case of class (i). Guided by this framework, we prioritized candidate functional regulatory variants that met stringent criteria, including significant enhancer activity, allele-specific transcriptional differences, and, where applicable, disruption of a motif context (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Table 10). Notably, the majority of these prioritized variants also exhibited consistent predicted effects across our machine learning models.

After establishing a high-confidence set of functional regulatory variants, we examined their genomic context to identify the genes they regulate. Because the majority of candidate functional regulatory variants are located in non-promoter regions, we posited that they act through distal enhancers that physically contact target promoters. To nominate enhancer-gene pairs, we applied the Activity-By-Contact (ABC) model80 to Hi-C, H3K27ac ChIP-seq, and ATAC-seq profiles from resting and LPS+IFN-γ-stimulated THP-1 macrophages81, thereby integrating chromatin interaction frequency with enhancer activity (Supplementary Table 11). Interestingly, our analysis revealed three target genes (TAS2R60, AZGP1, PIP) associated with bitter taste sensory pathways, which were enriched among functional regulatory variants in THP-1 macrophages (Extended Data Fig. 4f).

The integrated MPRA-machine-learning framework uncovered a rich set of context-dependent functional regulatory variants and, through ABC modelling, associated each variant cluster with candidate target genes. Equipped with these genomic links, we next interrogated the mechanisms by incorporating model interpretation with CRISPR perturbations to pinpoint how specific alleles rewire transcriptional programs in immune and neural states.

Mechanistic interpretation of functional regulatory variants at BIN1, MS4A, and SEC63-OSTM1 loci

Within the functional regulatory variants that show impacts on enhancer activities, several loci stand out as multiple variants showing divergent effects (Fig. 6a). These include (i) an well-characterized BIN1 enhancer; (ii) an enhancer within the critical MS4A locus, whose gene products modulate TREM2 expression and microglial state82,83; and (iii) a newly identified enhancer overlapping a rare variant cluster at SEC63-OSTM1 locus. Here we show how these variants influence transcription via modulating TF activities differently in immune and neural contexts.

Fig. 6 |. Mechanistic interpretation of causal variants at BIN1, MS4A, and SEC63-OSTM1 loci.

(a) Selected functionally causal variants at BIN1, MS4A, and SEC63-OSTM1 loci and their regulatory effects across cell types. Cells are colored only when the allelic effect is significant within a significantly active enhancer (MPRAnalyze, FDR < 0.05, |P.MAD| > 0.1): red indicates reduced transcription from the minor allele, green indicates increased transcription. Uncolored cells reflect significant allelic effects observed in enhancers that do not meet the activity threshold.

(b) BIN1 locus. Four microglia-active variants cluster in two adjacent enhancers. In enhancer 1, rs6733839 is predicted to strengthen an SPI1 site in immune cells or create an MEF2 site in neurons, yet the minor allele T represses transcription in THP-1 macrophage MPRA, implying SPI1-induced silencing in THP-1 macrophages. Enhancer 2 contains rs13025765 and rs13025717: rs13025765 flips direction between THP-1 macrophage (repression) and brain tissue (activation), reflecting SPIB- versus RFX-driven regulation, whereas rs13025717 disrupts a SP/KLF motif, lowering both transcription and predicted chromatin accessibility in THP-1 macrophages.

(c) MS4A6E intron. An enhancer harbors three functional variants. The minor T allele of rs10897049 strengthens an ETS motif and elevates transcription in macrophages. Conversely, in brain tissue, rs4477457-A disrupts an E2F motif, lowering activity, while rs10792265-G creates an RFX site that likely competes with E2F, further repressing expression. In THP-1 macrophages, these two alleles increased transcription activity, but models did not reveal TF motif differences.

(d) SEC63/OSTM1 enhancer. Four rare variants produced distinct MPRA readouts. The minor A allele of rs147038704 strengthens an SPI1 motif in THP-1 macrophages yet suppresses transcription in both THP-1 macrophages and mouse brain. The minor T allele of rs115607757 weakens a bZIP motif in THP-1 macrophages, lowering transcription in macrophages but elevating it in the brain. The minor C allele of rs189835276 disrupts an ETS-related motif and consistently increases transcription in both cell types.

(e) CRISPR interference experiments highlight the functional enhancer from panel d. Targeting this enhancer with dCas9-KRAB in resting THP-1 macrophages leaves SEC63 and OSTM1 transcripts unchanged yet significantly up-regulates GSAP and SSH1 (DESeq2, adj. P < 0.05). In contrast, silencing the SEC63 promoter provokes a broader secondary response, also elevating GSAP.

(f) Pathway enrichment of the CRISPRi RNA-seq data (fGSEA, FDR < 0.05) reveals state-specific effects of enhancer silencing: in the resting state, it elevates complement signaling and suppresses proliferative programs (E2F, G2M checkpoint, MYC), whereas under LPS+IFN-γ stimulation, it strengthens TNFα–NF–κB, Notch, and KRAS-up signatures and further represses E2F targets.

Asterisks in panels b-d denote variants whose allelic MPRA comparison is significant at FDR < 0.05.

Brain model prediction represents the averaged SHAP values from cortex and striatum models.

Fine-mapping at BIN1 has prioritized rs6733839, an SNP within a microglia-specific enhancer near a SPI1 motif, where the minor T allele creates an MEF2 site and increases chromatin accessibility in iPSC-derived microglia, potentially elevating transcription3–6,84. Previous MPRA assays in HEK293T and THP-1 cells showed no significant allele-specific effects, though subtle upregulation was noted30,31.

Here, we comprehensively evaluated rs6733839 using context-dependent, multilayered approaches (Fig. 6b). SNP-centered MPRA constructs again showed no significant allele-specific effects in THP-1 macrophages, brain tissue, or HEK293T cells. However, peak-centered constructs with rs6733839 at the 5′ or 3′ ends unexpectedly revealed T allele-driven transcriptional repression in THP-1 macrophages and HMC3 microglia-like cells. Machine learning models predicted increased chromatin accessibility for the T allele in both macrophages and brain tissue. Interestingly, immune models suggested the T allele strengthened the nearby SPI1 motif, leading to the observed repression in immune cells, while brain models predicted gain-of-function with MEF2 motif, consistent with upregulation detected in brain MPRA constructs. Synthetic enhancer tiling and motif shuffling analyses further revealed that the motif context surrounding rs6733839 operates as a context-dependent repressor, exhibiting potential combinatorial interactions with adjacent motifs (Extended Data Fig. 7). Its repression can be masked by a potent upstream activator, resulting in an overall activating outcome; however, it can also push downstream activators toward inactivity. Combined interactions with both upstream and downstream motifs result in net repression. Collectively, these data illustrate the complexity of enhancer logic, where a single motif may exert activating or repressive functions contingent on local sequence context and the composition of bound TFs. We also characterized rs13025717, a variant in the adjacent BIN1 enhancer previously predicted to have its T allele disrupt a KLF4 motif meanwhile indirectly affecting the nearby PU.1 (SPI1) binding84,85 (Fig. 6b). In THP-1 MPRA, the T allele reduced transcription, and models predicted decreased chromatin accessibility due to KLF4 motif loss. This variant has also been reported as a BIN1 eQTL in monocytes and a SPI1 binding QTL in the B-lymphoblastoid cell line GM1287885. Another variant, rs13025765, showed opposing effects between THP-1 and brain, reflecting differential engagement of SPIB in immune cells versus RFX in neural contexts (Fig. 6b). Together, these findings reveal how multiple BIN1 enhancer variants modulate LOAD risk through distinct TF mechanisms.

In MS4A, a major open chromatin region within MS4A6E intron 1 is accessible in both microglia and neurons but becomes less accessible under LPS+IFN-γ stimulation in THP-1 macrophages (Fig. 6c). We identified variants with context-specific motif effects: the T allele of rs10897049 strengthened an ETS motif, increasing transcription in macrophages but not in brain; the minor A allele of rs4477457 disrupted an E2F motif, reducing transcription in brain but not in macrophages; and rs10792265 created an RFX motif that may compete with E2F, reducing transcription in brain but not in THP-1 macrophages. These results highlight how individual motif disruptions can drive divergent immune- and neuron-specific transcriptional outcomes.

In the SEC63-OSTM1 intergenic region, four rare variants within an enhancer showed distinct MPRA profiles: three reduced transcription alleles and one increased transcription (Fig. 6d). Notably, these variants are not in linkage-disequilibrium (LD), indicating independent effects. ML analyses suggest that the minor allele T of rs147038704 upregulates SPI1 motifs yet represses transcription, while rs115607757 G allele weakens a bZIP site, reducing macrophage transcription but increasing brain expression. The rs189835276 T allele disrupts an ETS motif, increasing macrophage transcription.

Chromatin analysis (Hi-C, ATAC-seq, H3K27ac ChIP-seq) of publicly available data81 in THP-1 macrophages reveals that this active enhancer is positioned within a chromatin loop connecting the OSTM1 promoter and a distal CTCF site at AFG1L; Hi-C data also show that the enhancer lies within a high-contact region with the SEC63 promoter (Extended Data Fig. 8 a,b). These results suggest that the enhancer has the potential to regulate both OSTM1 and SEC63 expression. Consistently, RNA-seq confirms strong expression of OSTM1 and SEC63 (Supplementary Table 12).

Functionally, SEC63 and OSTM1 are involved in ER import and lysosomal acidification, linking them to LOAD-related ER stress, lysosomal dysfunction, and APP trafficking. To clarify the enhancer’s regulatory role, we performed CRISPRi knockdowns of the enhancer as well as SEC63 and OSTM1 in THP-1 macrophages under both resting and hyperinflammatory conditions. Surprisingly, enhancer repression left SEC63 and OSTM1 unchanged but elevated the LOAD effector genes GSAP and SSH1 by ~30 % (Fig. 6e). In the resting state, the perturbation up-regulated complement genes and down-regulated proliferation pathways (G2M checkpoint, E2F and MYC targets), steering macrophages toward an M1-like state (Fig. 6f). Under LPS+IFN-γ stimulation, the same knock-down amplified TNFα–NF-κB, Notch and KRAS-up signatures and further suppressed E2F targets, reinforcing inflammatory, metabolic and pro-survival pathways. Collectively, these data indicate that the enhancer functions as a gatekeeper for innate-immune signaling. GSAP and SSH1 were also upregulated in amyloid-treated iPSC-microglia and LPS+IFN-γ-stimulated THP-1 macrophages (Supplementary Table 12), implicating their roles in inflammation. Notably, knockdown of SEC63 or OSTM1 also affected immune response pathways and cellular metabolism, with SEC63 knockdown producing broader effects, especially under inflammatory conditions, underscoring their critical roles in macrophage function (Fig. 6e, Extended Data Fig. 8c, 8d, 8e).

Together, these findings reveal how functional regulatory variants at BIN1, MS4A, and SEC63-OSTM1 modulate transcription through distinct, cell type- and context-specific mechanisms, highlighting the critical roles of enhancer architecture and TF networks in orchestrating immune and neural programs relevant to LOAD.

Discussion

GWAS and rare variant studies continue to expand the catalogue of LOAD risk variants, yet fine-mapping these loci remains challenging. In GWAS, tightly linked variants often share indistinguishable association statistics, making it hard to nominate the true causal allele within each LD block. Conversely, WGS highlights ultra-rare variants, but their effect estimates are under-powered without complementary functional evidence. Compounding these issues, LOAD pathogenesis spans multiple cell types and tissues, so variants must be interpreted in the specific cellular contexts where they exert their effects.

Our study combined context-dependent in vitro and in vivo MPRA, deep learning models, and CRISPRi perturbations to systematically map the cell type- and state-specific regulatory effects of 599 LOAD-associated noncoding variants. By examining both common and rare variants across human myeloid cell lines, brain tissue, and diverse immune states, we uncovered striking heterogeneity in functional outcomes. We found several variants exhibiting opposing effects across cell types, underscoring the importance of testing variants in disease-relevant tissue, cellular, and immune conditions. This integrated framework highlights how noncoding variation shapes distinct immune and neural regulatory programs, offering mechanistic insights into the genetic architecture of LOAD.

Although previous GWAS and epigenomic studies highlighted the enrichment of LOAD risk variants in microglial and macrophage enhancers, most functional work has focused narrowly on common variants or immune contexts, leaving rare variants and neural settings largely unexplored. Here, we systematically compare common and rare LOAD variants across immune and neural contexts using reporter assays and deep learning. We show that common variants tend to exert stronger regulatory effects in immune cells, whereas rare variants tend to affect transcription more significantly in the brain context. These findings support our hypothesis that common LOAD variants identified by GWAS and enriched in microglial enhancers3–6,29,42,43,75 are more likely to affect immune regulatory programs, whereas rare variants identified through patient-family sequencing studies—often mapped to genes involved in neural development and synaptic plasticity32—are more likely to exert their effects in a neural context. Although the rare variants we tested are frequently located in regions with low ATAC signal, their potential gain-of-function roles or activities during developmental stages—when chromatin is generally more accessible—should be considered. Additionally, during aging, cells can undergo epigenomic erosion29,86, a process in which closed chromatin becomes more accessible and active regulatory elements lose activities leading to loss of cell identity, potentially enabling these variants buried in closed chromatin to exert effects later in life. The role of rare variants remains underappreciated in LOAD research, and identifying and understanding their functional impact is only the beginning.

By integrating MPRA and machine learning interpretations, we identified regulatory “hotspots” where multiple variants converge to modulate gene expression. Mechanistically, variants disrupt or strengthen TF binding sites, fine-tune motif strength, or rebalance competition among adjacent activators and repressors. Leveraging multidimensional measurements, we nominated functional regulatory variants and link enhancers to their target genes, including an unexpected enrichment of sensory genes, implicated in early LOAD deficits, in THP-1 macrophages.

Detailed analyses of representative loci revealed mechanisms underlying cell type-specific variant effects (Fig 6, Extended Data Fig. 7). At BIN1, prior MPRA studies using SNP-centered constructs failed to detect allele-specific effects; however, by employing longer, peak-centered constructs, we uncovered a reproducible repressive effect of the rs6733839 T allele in macrophages, mediated by SPI1 rather than the previously predicted MEF2 motif. Motif tiling further revealed complex interactions between the variant’s local context and neighboring motifs. Similarly, the rs13025717-T allele in another BIN1 enhancer was previously shown to reduce transcription in HEK293T MPRAs. In our THP-1 macrophage MPRAs, we observed T allele-driven repression only in SNP-centered constructs, while peak-centered constructs showed no effect. Model predictions pointed to SP/KLF motif disruption in immune, but not neural, contexts. These findings, along with the results of Ernst et al.45 and Klein et al.73, highlight how variant positioning and CRE length critically influence the detection and interpretation of regulatory effects, underscoring the need for diverse MPRA designs to capture motif interactions.

In parallel with the recent work of Bond et al.31, we examined variant effects under immune stimulation. We showed that LPS+IFN-γ, which mimics the hyperinflammatory state relevant to LOAD, elicited the most pronounced chromatin remodeling (ATAC-seq) and enhancer-activity shifts (MPRA) in THP-1 macrophages. Notably, at the resting THP-1 macrophages, rs73972710 (CTDP1), the major C allele forms a repressive ZBT motif at rest, whereas the minor T allele disrupts this motif and elevates transcription; upon LPS+IFN-γ stimulation, the major allele gains higher motif scores that mask the resting-state repression and reduces allelic differences, a pattern captured by both our models and MPRA readouts (Fig. 3f, 4h). Beyond CTDP1, several variants at other LOAD risk loci—including the immune-regulatory MS4A cluster, which multiple fine-mapping studies have implicated in disease susceptibility27,28,30,85,87—showed comparable allele-by-stimulation interactions, further underscoring the importance of assaying variants in disease-relevant cellular states. These cases, along with our immune-state profiling of macrophages demonstrate that the magnitude of LOAD-associated variant effects is dynamically tuned by cellular states, such as the inflammatory states implicated in the disease. Context dependence therefore extends beyond cell-type specificity to a temporal dimension in which immune activation scales variant impact. Evaluating candidate variants within disease-relevant immune milieus is thus essential for revealing their full pathogenic potential.

At the SEC63-OSTM1 intergenic enhancer, we identified four functional regulatory rare variants with independent, allele-specific transcriptional effects in THP-1 macrophages mediated through immune motifs. Although Hi-C analysis implicated enhancer interactions with the nearby genes SEC63 and OSTM1, CRISPRi-mediated enhancer perturbation unexpectedly increased expression of distant LOAD effector genes, notably GSAP and SSH1, while enhancing pro-inflammatory signaling pathways without altering SEC63 or OSTM1 transcript levels. γ-Secretase activating protein (GSAP) promotes amyloid-β production via interactions with the γ-secretase complex and amyloid precursor protein (APP)88, whereas Slingshot-1 (SSH1), an actin phosphatase, attenuates Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses, with its loss ameliorating Aβ and tau pathology89. Thus, increased expression of GSAP and SSH1 likely exacerbates complementary pathogenic mechanisms in LOAD—amyloid deposition and oxidative stress—indicating the enhancer typically serves as a suppressor of these detrimental pathways. Remarkably, although GSAP and SSH1 reside on chromosomes distinct from the enhancer, both genes exhibited altered expression following enhancer perturbation and were upregulated in the inflammatory macrophages, likely reflecting secondary consequences of enhanced innate immune activation. These findings highlight a notable instance wherein distal noncoding regulatory elements modulate LOAD-associated networks through non-canonical or higher-order interactions, linking noncoding genetic variation to amyloidogenesis, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation.

These mechanistic insights were enabled by several technical advances that improved both the sensitivity and resolution of our measurements. Transcriptomic and epigenomic profiling of cytokine-stimulated THP-1 macrophages ensured that variant effects were assayed in immune states relevant to LOAD pathophysiology. We optimized electroporation-based delivery of MPRA libraries into THP-1 cells, which are typically challenging to transfect, enabling reproducible detection of stimulus-responsive enhancer activities. Building on previous work by Brown et al.49, which demonstrated systemic AAV-mediated MPRA delivery across the blood-brain barrier (sysMPRA), we achieved increased reproducibility and larger library sizes using pseudo-barcoding strategies that aggregate barcodes with similar representation to establish robust expression estimates across individual animals. In parallel, we adapted convolutional neural networks from Ramamurthy et al.27 to predict chromatin accessibility using 500 bp sequences, achieving consistent performance across cell types and datasets, including those generated in different laboratories. To quantify machine learning-predicted variant effects with confidence, we applied both cell-type-matched null distributions and dropout-based uncertainty estimation. Together, these innovations enabled high-confidence, context-specific dissection of noncoding variant function at scale, laying the foundation for systematic interpretation of regulatory architecture in LOAD.

Several limitations warrant mention. THP-1 and HMC3 cells, while experimentally tractable, are surrogates for primary human microglia and macrophages and do not fully capture the complexity of the brain immune milieu. Although we have previously demonstrated an overall conservation of the ‘regulatory code’ between rodent and primate90,91, our in vivo MPRAs in mice may introduce cross-species regulatory differences. Moreover, synthetic CREs, though powerful, may overlook contributions from long-range chromatin contacts, topological features, or promoter-like elements. We also note that some variants, such as rs563571689 at the last nucleotide of APOE exon 1, are predicted to alter splicing without affecting MPRA output, highlighting the importance of complementary assays to capture the full regulatory landscape. While we identified variants with effects specific to brain tissue rather than immune cells, we lacked the statistical power to resolve region-specific effects within the brain. Furthermore, variants with cell type-restricted regulatory functions may be masked in bulk-tissue MPRAs due to their limited representation in the sampled population. Continued method development is needed to achieve single-cell resolution within the native tissue context. Emerging droplet-based single-cell92,93 and spatially resolved62 MPRA platforms offer a promising path to pinpoint subtle, context-specific effects, such as those acting in neural subtypes or immune activation states not represented in our current in vitro systems.

Our findings open key avenues for future research, including systematic enhancer-gene mapping, investigation of variant effects in motif-motif interactions, functional studies of hotspot genes, and defining the cellular states where variants become active to guide therapeutic strategies. Together, these efforts will deepen our understanding of noncoding genetic risks and advance the development of precision therapies for LOAD.

Methods

Cell Culture and Animals

THP-1 Macrophage Differentiation

THP-1 monocytes (ATCC TIB-202) were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in 5% CO₂, with a density of under 1 million cells/mL. Differentiation into macrophages was induced by treating cells with 100 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Sigma-Aldrich) for 72 h, followed by a 24 h resting period in PMA-free medium.

HMC3 Microglia-like Cell Culture

HMC3 microglia-like cells (ATCC CRL-3304) were cultured in Microglial Cell Medium Kit (Accegen, ABI-TM009) and maintained at 37°C with 5% CO₂. Cells were passaged before reaching confluence and seeded at appropriate densities for downstream assays.

HEK293T Cell Culture

HEK293T cells (AAVpro(R), Clontech, Cat. No. 632273) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and maintained at 37°C with 5% CO₂. Cells were passaged into fresh medium before reaching confluence and seeded at appropriate densities for downstream assays.

Stimulation of THP-1 Macrophages and HMC3 Microglia

To model diverse immune states, THP-1 macrophages were stimulated for 4 h and HMC3 microglia for 24 h with interferon-β (IFN-β, 20 ng/mL; R&D Systems), interferon-γ (IFN-γ, 20 ng/mL; PeproTech), or lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 ng/mL; InvivoGen) plus IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) to induce antiviral, M1-like, and hyperinflammatory states, respectively. For ATAC-seq characterization of THP-1 macrophages, THP-1 macrophages were additionally stimulated for 24 h to assess longer-term transcriptional and chromatin accessibility changes. Stimulated cells were harvested for RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and MPRA assays.

Animals

All procedures were approved by the Carnegie Mellon University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Experiments were conducted on 10-week-old C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, strain 000664; n = 4, 2 males and 2 females). Animals were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions in individually ventilated cages (≤ 5 mice per cage) containing corncob bedding and nestlet enrichment. The animal room was maintained at 20–22 °C with 45 % relative humidity and a 12 h:12 h light-dark cycle. Autoclaved standard chow (LabDiet 5001) and UV-irradiated water were provided ad libitum. Detailed surgical procedures are described in the section ‘Plasmid Library Transduction of Mouse Brain Regions via AAV Viruses’.

ATAC-seq Experiments

Cell Preparation and Lysis

THP-1 monocytes were centrifuged and pelleted, lysed using pre-chilled Buenrostro lysis buffer94, homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer on ice, and then debris was removed by filtration through a 70 μm mesh. Similarly, THP-1-derived macrophages, adhered to 6-well plates, were lysed with pre-chilled Buenrostro lysis buffer on ice for 10 minutes. Nuclei were dislodged using cell scrapers, filtered through a 70 μm mesh, and pelleted by centrifugation at 500 xg for 5 minutes at 4°C.

Nuclei Isolation and DNA Tagmentation

Isolated nuclei were resuspended in nuclease-free water. DAPI-stained nuclei were quantified to approximately 50,000 using a Countess II cell counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific). These nuclei underwent DNA tagmentation using the Illumina Tagment DNA TDE1 Enzyme and Buffer Kits, incubated at 37°C with shaking at 300 rpm for 30 minutes.

Library Preparation and Amplification

Tagmented DNA was purified using the Qiagen MinElute PCR Purification Kit. The sequencing library was then prepared using NEBNext High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix and primers (Eurofins Genomics) following the Illumina Nextera tagmentation format as previously published95, with the optimal number of amplification cycles determined via qPCR side reactions to be an average of 9 cycles. Final PCR products were purified using the NEB Monarch Nucleic Acid Purification Kit (# T1030).

ATAC-seq Library Sequencing

MPRA sequencing libraries were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq™ 6000 platform at GENEWIZ from Azenta Life Sciences using paired-end 150 bp reads. The libraries achieved an average sequencing depth of 68 million reads per sample.

ATAC-Seq Data Processing

FASTQ files were processed using the ENCODE ATAC-Seq Pipeline. Paired-end sequencing reads from biological replicates in fastq format were analyzed with the pipeline’s default settings. The Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) optimal peaks, derived from these analyses, were utilized for both differential analyses and machine learning model training.

Differential Analysis of THP-1 Macrophages upon Stimulation

Common open chromatin regions were identified by merging IDR optimal peaks from both resting and stimulated THP-1 macrophages within a 200 bp proximity. This merging was performed using the bedtools suite with the command: bedtools sort −i {input} | bedtools merge −d 200 −i − > {output}. Read counts at each peak for each cell type were quantified using the featureCounts function from the Rsubread package, utilizing the bam files and bed files of common chromatin peaks. Differential accessibility analysis was executed using the DESeq296 package, with filtering criteria set to include peaks that had at least one read in a minimum of two replicates. Peaks with significantly different accessibility were determined using a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of <0.05. Differentially accessible promoter regions were annotated using the hg38 human genome assembly, focusing on known genes within a 500 bp range of the identified open chromatin regions.

Variants Enrichment Analysis: stratified LD Score Regression (S-LDSC)

To pinpoint cell types enriched for LOAD risk, we applied stratified LD score regression (S-LDSC)97 on open chromatin data from various sources. We obtained open chromatin promoter, enhancer and dyadic peaks for 111 reference epigenomes from the Epigenome Roadmap database36. These peaks were merged using bedtools98 and treated as background peaks. Following the original S-LDSC methodology, testing LOAD variants in enrichment in the open chromatin peak of the candidate cell type relative to the Roadmap background. Enrichment p-values were then adjusted across all tests using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction, with enriched cell types defined by a q-value below 0.05. This analysis was performed separately for using different GWAS summary statistics3–6.

RNA-seq Experiments

RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing