Abstract

Background:

The genetic architecture of Parkinson's disease (PD) varies considerably across ancestries, yet most genetic studies have focused on individuals of European descent, limiting our insights into the genetic architecture of PD at a global scale.

Methods:

We conducted a large-scale, multi-ancestry investigation of causal and risk variants in PD-related genes. Using genetic datasets from the Global Parkinson's Genetics Program, we analyzed sequencing and genotyping data from 69,881 individuals, including 41,139 affected and 28,742 unaffected, from eleven different ancestries, including ~30% of individuals from non-European ancestries.

Findings:

Our findings revealed shared and ancestry-specific patterns in the prevalence and spectrum of PD-associated variants. Overall, ~2% of affected individuals carried a causative variant, with substantial variations across ancestries ranging from <0·5% in African, African-admixed, and Central Asian to >10% in Middle Eastern and Ashkenazi Jewish ancestries. Including disease-associated GBA1 and LRRK2 risk variants raised the yield to ~12.5%, largely driven by GBA1, except in East Asians, where LRRK2 risk variants dominated. GBA1 variants were most frequent globally, albeit with substantial differences in frequencies and variant spectra. While GBA1 variants were identified across all ancestries, frequencies ranged from 3·4% in Middle Eastern to 51·7% in African ancestry. Similarly, LRRK2 variants showed ancestry-specific enrichment, with G2019S most frequently seen in Middle Eastern and Ashkenazi Jewish, and risk variants predominating in East Asians. However, clinical trials targeting proteins encoded by these genes are primarily based in Europe and North America.

Interpretation:

This large-scale, multi-ancestry assessment offers crucial insights into the population-specific genetic architecture of PD. It underscores the critical need for increased diversity in PD genetic research to improve diagnostic accuracy, enhance our understanding of disease mechanisms across populations, and ensure the equitable development and application of emerging precision therapies.

Keywords: PD, Multi-ancestry, Genetics, LRRK2, GBA1, SNCA, PRKN, causal variants, risk variants, precision medicine

Introduction

Genetic discoveries have transformed our understanding of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Genetic factors substantially contribute to PD risk and progression,1 comprising a spectrum ranging from rare variants with large effect sizes to common variants with small effect sizes. More than 130 independent risk loci have been identified by genome-wide association studies,2 and over 15 genes have been linked to monogenic PD and parkinsonism.1,3

A critical gap in PD genetics research is the lack of ancestral diversity.4 Although genetic forms of PD are found globally, approximately 75% of all genetic PD studies to date focused on European-ancestry individuals.5,6 Research in diverse populations is critical to uncovering unique genetic contributions to disease, which is particularly relevant for clinical trials driven by genetic discoveries, e.g., targeting glucocerebrosidase or LRRK2 kinase activity (encoded by the PD-linked genes GBA1 and LRRK2, respectively). Lack of diversity may limit the global applicability of emerging opportunities, as it is unclear whether current genetic targets are relevant across ancestries or whether population-specific variants exist. Expanding genetic studies to all ancestries is essential to improve diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic development.

The Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2; https://gp2.org/)7 is a large-scale initiative actively addressing this gap by investigating the genetic underpinnings of PD and parkinsonism across global populations.5,8 The aim of this study was to investigate pathogenic and high-risk variants linked to PD and parkinsonism at a global scale using data from GP2.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

Our study workflow is displayed in Figure 1. We used short-read sequencing data from GP2 Release 8 (DOI 10.5281/zenodo.13755496), including clinical exome and genome sequencing (WGS) data, and genome-wide Illumina NeuroBooster Array genotyping data from GP2 Release 9 (DOI 10.5281/zenodo.14510099). Data processing and quality control are described elsewhere.9

Figure 1. Study workflow.

We used short-read sequencing and genome-wide genotyping data and investigated variants in 18 genes linked to PD and parkinsonism. Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants according to ClinVar and/or ACMG criteria are referred to as causative variants, and selected variants with an established PD-risk association are referred to as risk variants. Figure created with BioRender.

* For the purpose of this study and in the context of PD, all variants in GBA1 (including variants causal for Gaucher’s disease) are considered PD risk variants (regardless of their Gaucher’s severity).

** Select LRRK2 variants with established PD-risk associations included rs33949390 (chr12:40320043:G:C, R1628P) and rs34778348 (chr12:40363526:G:A, G2385R).

AAC = African Admixed, ACMG = American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, AFR = African, AJ = Ashkenazi Jewish, AMR = Latinos and Indigenous people of the Americas, CAH = Complex Admixture, CES = clinical exome sequencing, CAS = Central Asian, EAS = East Asian, EUR = European, FIN = Finnish, GP2 = Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program, MDE = Middle Eastern, OR = Odds ratio, PD = Parkinson’s disease, SAS = South Asian, WGS = whole-genome sequencing

The sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The total sample comprised 69,881 individuals, including 41,139 clinically affected individuals (PD and other neurodegenerative phenotypes) and 28,742 unaffected individuals (controls, population cohorts, and unaffected family members). Both groups included genetically enriched samples, i.e., individuals specifically recruited based on their genetic status (e.g., GBA1, LRRK2, or SNCA variant carriers). Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the number of samples categorized by available genetic data, and divided by genetically determined9 ancestry, including African-Admixed (AAC), African (AFR), Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ), Latinos and Indigenous People of the Americas (AMR), Complex Admixture (CAH), Central Asian (CAS), East Asian (EAS), European (EUR), Finnish (FIN), Middle Eastern (MDE), and South Asian (SAS).

Table 1. Study sample characteristics.

Summary of sample numbers and cohort-level data by study type, including sex, age, age at onset (if applicable), and family history of Parkinson’s disease.

| Group | n samples | Male (%) | Median Age* (range) | Median AAO (range) | Positive FH of PD** (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affected individuals | 41139 | 24886 (60.5) | 67.5 (12–114), [unk for n = 10639] | 59 (5–102), [unk for n = 13998] | 8414 (20.5), [unk for n = 13635] |

| PD cohort unselected | 33329 | 22718 (61.2) | 68 (18–114), [unk for n = 6822] | 60 (5–98), [unk for n = 14067] | 6189 (18.6), [unk for n = 9840] |

| Monogenic recruitment | 3421 | 1977 (57.8) | 59 (19–101), [unk for n = 1211] | 48 (6–102), [unk for n = 173] | 1720 (50.3), [unk for n = 456] |

| Other phenotypes | 3539 | 1971 (55.7) | 72 (12–97), [unk for n = 2604] | 66 (6–88), [unk for n = 2191] | 184 (5.2), [unk for n = 3079] |

| Genetic enrichment affected | 850 | 448 (77.2) | 67 (21–91), [unk for n = 2] | 57 (16–88), [unk for n = 454] | 321 (37.8), [unk for n = 260] |

| Unaffected individuals | 28742 | 14833 (51.6) | 63 (16–104), [unk for n = 6706] | NA | 1410 (4.9), [unk for n = 20193] |

| Controls | 18585 | 9845 (53.0) | 63 (17–104), [unk for n = 6672] | NA | 689 (3.7), [unk for n = 10838] |

| Unaffected family members | 184 | 92 (50.0) | 71 (67–84), [unk for n = 0] | NA | 184 (100), [unk for n = 0] |

| Population cohort | 9245 | 4607 (49.8) | 63 (45–94), [unk for n = 0] | NA | 0 (0), [unk for n = 9245] |

| Genetic enrichment unaffected | 728 | 289 (39.7) | 59 (19–90), [unk for n = 2] | NA | 537 (73.8), [unk for n = 110] |

| TOTAL | 73710 | 41947 (56.9) | NA | 10524 (14.3), [unk for n = 34305] |

Age refers to the age at recruitment/age at sample collection;

Including related individuals.

AAO = Age at onset, FH = Family history, NA = not available/not applicable, PD = Parkinson's disease, unk = unknown, PD cohort unselected = Samples of PD cases recruited without specific selection criteria. Monogenic recruitment = Samples of affected individuals with a suspected monogenic cause of PD based on an early age at onset (≤50 years) or a positive family history of PD. Other phenotypes = Individuals with diagnoses other than PD, including atypical parkinsonism (e.g., dementia with Lewy bodies, corticobasal degeneration/syndrome, multisystem atrophy, and progressive supranuclear palsy), mild cognitive impairment and dementia (e.g., Alzheimer's disease, unspecified dementia), clinically diagnosed PD without a dopaminergic deficit in imaging (SWEDD), tremor, any other neurodegenerative diseases, and unspecified parkinsonism. Genetic enrichment affected = Individuals specifically recruited based on their genetic status, i.e., clinically affected GBA1, LRRK2, or SNCA variant carriers. Controls = Neurologically healthy controls. Unaffected family members = Unaffected family members of individuals with PD. Population cohort = Group representative of a general population, not affected by neurodegenerative diseases. Genetic enrichment unaffected = Individuals specifically recruited based on their genetic status, i.e., clinically unaffected GBA1, LRRK2, or SNCA variant carriers.

Genes and variants of interest

We focused on variants in genes linked to PD and parkinsonism following the recommendations of the MDS Task Force on the Nomenclature of Genetic Movement Disorders3, including variants in i) LRRK2, SNCA, and VPS35 linked to autosomal-dominant PD, ii) DJ-1/PARK7, PINK1, and PRKN linked to autosomal-recessive PD, and iii) ATP13A2, DCTN1, DNAJC6, FBXO7, JAM2, RAB39B, SLC20A2, SYNJ1, VPS13C, and WDR45 linked to atypical parkinsonism. We included only PARK-designated genes; variants in genes linked to combined phenotypes including PD or parkinsonism (e.g., dystonia-parkinsonism) were beyond the scope of this study. We added RAB32 S71R, identified as causal for PD after the Task Force gene list was published. We included pathogenic/likely pathogenic (according to ClinVar; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) variants in these genes and also investigated PD risk-associated variants in GBA1 and LRRK2, given their established translational significance. For details on pathogenicity evaluation, see Figure 1 and Supplementary Material. Copy number variation (CNV) analyses for SNCA and PRKN were done as described before.10 Carriers of two heterozygous pathogenic variants in recessive genes and an age at onset (AAO) ≤50 years were considered likely compound heterozygous without further validation, based on findings from previous studies.11

Results

Summary

Across all ancestries, a total of 2·1% (826/40,288) of affected individuals carried a causative and 10·8% (4,331/40,288) a risk variant (Table 2). In comparison, causative variants were observed in 0.2% (67/28,014) and risk variants in 7·5% (2,103/28,014) of unaffected individuals (Table 3).

Table 2. Yield of genetic findings in affected individuals across ancestries.

Proportion of affected individuals with genetic findings identified in this study, shown with and without genetically enriched cohorts, stratified by ancestry and by variant type (causal and risk variants vs. only causal variants).

| AAC | AFR | AJ | AMR | CAH | CAS | EAS | EUR | FIN | MDE | SAS | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All affected individuals (incl. genetically enriched studies) | ||||||||||||

| Samples investigated [n] | 373 | 1030 | 2045 | 2143 | 813 | 756 | 3394 | 29339 | 121 | 620 | 505 | 41139 |

| Causal and risk variants | ||||||||||||

| Genetic finding [n] | 134 | 536 | 781 | 134 | 161 | 48 | 624 | 3262 | 14 | 104 | 38 | 5836 |

| Yield [%] | 35.92 | 52.04 | 38.19 | 6.25 | 19.80 | 6.34 | 18.39 | 11.12 | 11.57 | 16.77 | 7.52 | 14.19 |

| Only causal variants | ||||||||||||

| Genetic finding [n] | 1 | 2 | 425 | 59 | 30 | 6 | 53 | 621 | 0 | 85 | 6 | 1288 |

| Yield [%] | 0.27 | 0.19 | 20.78 | 2.75 | 3.69 | 0.79 | 1.56 | 2.12 | 0 | 13.71 | 1.19 | 3.13 |

| All affected individuals (excl. genetically enriched studies) | ||||||||||||

| Samples investigated [n] | 371 | 1030 | 1745 | 2140 | 812 | 753 | 3363 | 28859 | 120 | 596 | 499 | 40288 |

| Causal and risk variants | ||||||||||||

| Genetic finding [n] | 132 | 536 | 482 | 132 | 160 | 47 | 613 | 2925 | 14 | 80 | 36 | 5157 |

| Yield [%] | 35.58 | 52.04 | 27.62 | 6.17 | 19.70 | 6.24 | 18.23 | 10.14 | 11.67 | 13.42 | 7.21 | 12.80 |

| Only causal variants | ||||||||||||

| Genetic finding [n] | 1 | 2 | 226 | 57 | 29 | 5 | 46 | 393 | 0 | 61 | 6 | 826 |

| Yield [%] | 0.27 | 0.19 | 12.95 | 2.66 | 3.57 | 0.66 | 1.37 | 1.36 | 0 | 10.23 | 1.20 | 2.05 |

AAC = African Admixed, AFR = African, AJ = Ashkenazi Jewish, AMR = Latino and Indigenous people of the Americas, CAH = Complex Admixture, CAS = Central Asian, EAS = East Asian, EUR = European, FIN = Finnish, MDE = Middle Eastern, SAS = South Asian.

Table 3. Yield of genetic findings in unaffected individuals across ancestries.

Proportion of unaffected individuals with genetic findings identified in this study, shown with and without genetically enriched cohorts, stratified by ancestry and by variant type (causal and risk variants vs. only causal variants).

| AAC | AFR | AJ | AMR | CAH | CAS | EAS | EUR | FIN | MDE | SAS | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All unaffected individuals (incl. genetically enriched studies) | ||||||||||||

| Samples investigated [n] | 855 | 1743 | 1158 | 1485 | 339 | 371 | 2503 | 19795 | 14 | 244 | 235 | 28742 |

| Causal and risk variants | ||||||||||||

| Genetic finding [n] | 225 | 576 | 516 | 17 | 43 | 13 | 238 | 1233 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2858 |

| Yield [%] | 26.32 | 33.04 | 44.56 | 1.14 | 12.68 | 3.50 | 9.51 | 6.23 | 7.14 | 1.23 | 1.33 | 9.94 |

| Only causal variants | ||||||||||||

| Genetic finding [n] | 1 | 1 | 258 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 216 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 497 |

| Yield [%] | 0.12 | 0.06 | 22.28 | 0.20 | 1.47 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 1.09 | 0 | 1.23 | 0 | 1.73 |

| All unaffected individuals (excl. genetically enriched studies) | ||||||||||||

| Samples investigated [n] | 855 | 1743 | 695 | 1481 | 337 | 370 | 2503 | 19539 | 14 | 242 | 235 | 28014 |

| Causal and risk variants | ||||||||||||

| Genetic finding [n] | 225 | 576 | 60 | 13 | 42 | 12 | 238 | 999 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2170 |

| Yield [%] | 26.32 | 33.04 | 8.63 | 0.88 | 12.46 | 3.24 | 9.51 | 5.11 | 7.14 | 0.41 | 1.33 | 7.75 |

| Only causal variants | ||||||||||||

| Genetic finding [n] | 1 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 43 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 67 |

| Yield [%] | 0.12 | 0.06 | 2.30 | 0.07 | 1.48 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0 | 0.41 | 0 | 0.24 |

AAC = African Admixed, AFR = African, AJ = Ashkenazi Jewish, AMR = Latino and Indigenous people of the Americas, CAH = Complex Admixture, CAS = Central Asian, EAS = East Asian, EUR = European, FIN = Finnish, MDE = Middle Eastern, SAS = South Asian.

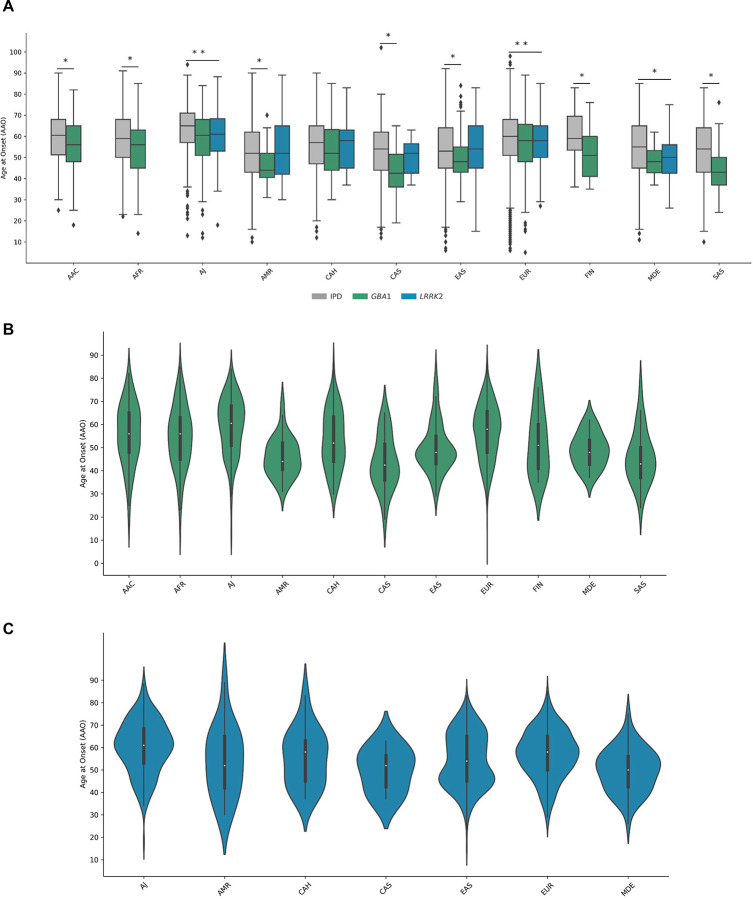

Among all affected variant carriers, we observed 53 distinct single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in 12 genes, next to structural variations like SNCA gene multiplications and variable PRKN exon deletions and duplications, two LRRK2 risk variants, and 63 GBA1 variants. GBA1 variant carriers were most frequent overall and detected across all ancestries, albeit with substantially different variant spectra (Figure 2). LRRK2 and PRKN variants were also identified across multiple ancestries, whereas causative variants in other genes were rarer and only identified in certain populations (Figure 3 and 4). Across multiple ancestries, individuals with GBA1-associated PD showed a significantly earlier median AAO of 3 to 8 years, compared to those with idiopathic PD (IPD) (Figure 5A and Supplementary Table 2). The AAO between LRRK2-PD and IPD differed significantly in AJ, EUR, and MDE, with LRRK2-PD showing a 1- to 4-year earlier onset (Figure 5A and Supplementary Table 2). Further, the AAO distribution among GBA1 and LRRK2 carriers showed heterogeneity across ancestries (Figure 5B and C).

Figure 2. Mutational and severity spectrum of GBA1 variants across ancestries.

Donut charts illustrate the spectrum of GBA1 variants identified across ancestries, stratified by variant severity. Severity was assessed using the GBA1-PD browser (https://pdgenetics.shinyapps.io/GBA1Browser/); notably, the newly identified c.1225–34C>A variant (rs3115534-G) is not yet included and was therefore grouped as unknown. Each segment size reflects the percentage of variant carriers within each ancestry. The inner colors represent variant severity categories: Severe (purple), Mild (blue), Risk (green), and Unknown (gray). The outer segments show individual variants, with color shades corresponding to the inner severity group. Due to the high number of different variants, for EAS, all severe variants with <3 carriers were grouped as “Other”, and for EUR, all variants with <10 carriers were grouped as “Other”. Similarly, due to the very small percentage of GBA1 variants other than c.1225–34C>A in AFR, all severe and mild variants were each grouped as “Other”.

AAC = African Admixed, AFR = African, AJ = Ashkenazi Jewish, AMR = Latinos and Indigenous people of the Americas, CAH = Complex Admixture, CAS = Central Asian, EAS = East Asian, EUR = European, FIN = Finnish, MDE = Middle Eastern, SAS = South Asian.

Figure 3. Distribution of variants in genes linked to Parkinson’s disease (PD) and parkinsonism across ancestries.

Horizontal stacked bar charts displaying the percentage of identified variant carriers per gene amongst all carriers per ancestry: (A) only variants considered causal (excluding genetically enriched cohorts), (B) causal and risk variants excluding genetically enriched cohorts, and (C) causal and risk variants including genetically enriched cohorts. Numbers in bars indicate the absolute number of carriers. Dual carriers harbor variants in two different genes (e.g., LRRK2 and GBA1). Atypical includes carriers of variants in ATP13A2, RAB39B, SLC20A2, and WDR45. LRRK2 risk variants are R1628P and G2385R.

AAC = African Admixed, AFR = African, AJ = Ashkenazi Jewish, AMR = Latinos and Indigenous people of the Americas, CAH = Complex Admixture, CAS = Central Asian, EAS = East Asian, EUR = European, FIN = Finnish, MDE = Middle Eastern, SAS = South Asian.

Figure 4. Global genetic spectrum of PD and locations of clinical trials targeting gene variant carriers.

(A) Donut charts displaying the percentage of identified carriers per gene amongst all carriers per ancestry. Dual carriers harbor variants in two different genes (e.g., LRRK2 and GBA1). Atypical includes carriers of variants in ATP13A2, RAB39B, SLC20A2, and WDR45. LRRK2 risk variants are R1628P and G2385R. (B) Global map of clinical trial locations recruiting gene variant carriers (GBA1, LRRK2, PINK1, and PRKN), obtained from the clinical trial registry https://clinicaltrials.gov/. Only one pin per gene and country is shown, regardless of the number of study sites within that country.

AAC = African Admixed, AFR = African, AJ = Ashkenazi Jewish, AMR = Latinos and Indigenous people of the Americas, CAH = Complex Admixture, CAS = Central Asian, EAS = East Asian, EUR = European, FIN = Finnish, MDE = Middle Eastern, SAS = South Asian.

Figure 5. Ancestry-Stratified Age at Onset in Idiopathic, GBA1-, and LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s Disease.

(A) Boxplots of ages at onset (AAO) for individuals with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD; gray), GBA1-associated PD (green), and LRRK2-linked PD (blue) grouped by ancestry. Boxes indicate interquartile ranges, horizontal lines represent median, and whiskers show the range. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Statistically significant group differences within ancestry based on linear regression are indicated by asterisks. (B) and (C) Violin plots of AAO for GBA1-associated PD (Panel B; green) and LRRK2-linked PD (Panel C; blue) across ancestries. Each violin reflects the distribution and median AAO within each ancestry group.

AAC = African Admixed, AFR = African, AJ = Ashkenazi Jewish, AMR = Latinos and Indigenous people of the Americas, CAH = Complex Admixture, CAS = Central Asian, EAS = East Asian, EUR = European, FIN = Finnish, MDE = Middle Eastern, SAS = South Asian.

The distribution of variants per gene across ancestries is summarized in Figures 3 and 4, Table 4, and Supplementary Table 3. Detailed results for each ancestry (excluding genetically enriched cohorts) are reported below, while results inclusive of genetically enriched cohorts are provided in Figure 3, Table 2, and Supplementary Table 3.

Table 4. Summary of genetic findings across all ancestries.

Overview of variant findings per gene by ancestry, including affected and unaffected individuals, limited to individuals from non-genetically enriched cohorts.

| PD risk | Typical autosomal-dominant PD | Early-onset recessive PD | Atypical parkinsonism | Dual carriers ** | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBA1 | LRRK2 | LRRK2 risk * | SNCA | VPS35 | RAB32 | PINK1 | PRKN | PARK7/DJ-1 | ATP13A2 | DCTN1 | SLC20A2 | RAB39B | WDR45 | |||

| AAC | Affected | 131 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unaffected | 222 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| AFR | Affected | 532 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unaffected | 573 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| AJ | Affected | 256 | 201 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| Unaffected | 44 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| AMR | Affected | 75 | 46 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Unaffected | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CAH | Affected | 127 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unaffected | 36 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CAS | Affected | 30 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Unaffected | 9 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| EAS | Affected | 114 | 10 | 439 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Unaffected | 19 | 1 | 217 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| EUR | Affected | 2501 | 248 | 31 | 29 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 63 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 26 |

| Unaffected | 936 | 35 | 19 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| FIN | Affected | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unaffected | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| MDE | Affected | 19 | 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Unaffected | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SAS | Affected | 29 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unaffected | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Variants identified as LRRK2 PD risk variants in the Asian population, including rs33949390 (chr12:40320043:G:C, p.R1628P) and rs34778348 (chr12:40363526:G:A, p.G2385R).

Dual carriers refers to carriers of two pathogenic/likely pathogenic or PD risk variants in two different genes.

AAC = African Admixed, AFR = African, AJ = Ashkenazi Jewish, AMR = Latino and Indigenous people of the Americas, CAH = Complex Admixture, CAS = Central Asian, EAS = East Asian, EUR = European, FIN = Finnish, MDE = Middle Eastern, SAS = South Asian.

African-Admixed ancestry (371 affected and 855 unaffected individuals)

Pathogenic or risk variants were observed in 35·6% of affected individuals (132/371). One early-onset PD patient (AAO=27 years) harbored a homozygous PRKN deletion. All other affected carriers harbored GBA1 variants, most frequently the intronic rs3115534-G variant, found in 120/131 GBA1 carriers (18 homozygous; overall frequency 32·3% [120/371]), while the remaining 11 individuals (3·0%) carried five distinct coding variants (Figure 2). GBA1 variants were also identified in unaffected individuals (222/855; 26·0%), most commonly rs3115534-G (203/222 GBA1 carriers; overall frequency 23·7% [203/855]). One unaffected individual harbored a LRRK2 risk variant, and two pathogenic LRRK2 variants, one being an unaffected family member (aged 27 years) of a PD patient (G2019S).

African ancestry (1,030 affected and 1,743 unaffected individuals)

Among all identified affected carriers (536/1,030; 52·0%), GBA1 variants were most frequent, particularly rs3115534-G (517/532 GBA1 carriers; 123 homozygous; overall frequency 50·2% [517/1,030]). A small subset (15/1,030; 1·5%) carried nine distinct GBA1 coding variants (Figure 2). Variants in other genes were rare and included LRRK2 G2019S (n=1; 0·1%), LRRK2 R1628P (n=2; 0·2%), and one (0·1%) early-onset PD patient (AAO=28 years) harboring two heterozygous PRKN variants. Among unaffected variant carriers (576/1,743; 33·0%), the majority harbored GBA1 rs3115534-G (568/573; overall frequency 32·6% [568/1,743]) or GBA1 coding variants (5/1,743; 0·3%). Three controls (0·2%), carried LRRK2 variants (R1628P, n=2 and R1325Q, n=1).

Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry (1,745 affected and 695 unaffected individuals)

In total, 27·6% (482/1,745) of affected individuals harbored pathogenic and risk variants, all in GBA1 or LRRK2. 14·7% (256/1,745) carried eight distinct GBA1 variants (Figure 2), most frequently N409S (178/256). Most GBA1 carriers were PD patients, while a subset (n=12) had other neurodegenerative diseases. 11·5% (201/1,745) of affected individuals carried LRRK2 variants, including one individual harboring R1067Q, while all others harbored G2019S. One LRRK2 carrier was diagnosed with corticobasal degeneration, all others had PD. Another 25 individuals (1·4%) carried LRRK2 G2019S and a GBA1 variant. Among unaffected individuals, 8·6% (60/695) harbored GBA1 or LRRK2 variants.

Latinos and Indigenous people of the Americas (2,140 affected and 1,481 unaffected individuals)

Among all identified affected carriers (134/2,140; 6·3%), GBA1 variants were most frequent (75/2,140; 3·5%). Fifteen different GBA1 variants were identified; E365K, T408M, and N409S were most common (Figure 2). 2·1% (46/2,140) carried LRRK2 variants; all but one G2019S. One individual carried a G2019S and a GBA1 variant. Ten individuals (0·5%) harbored biallelic PRKN variants (six homozygous and four likely compound heterozygous) and two (0·1%) biallelic ATP13A2 variants. Among unaffected individuals, 0·8% (12/1,481) harbored GBA1 and 0·1% (1/1,481) LRRK2 variants.

Complex Admixture (812 affected and 337 unaffected individuals)

Causative or risk variants were identified in 19·7% (160/812) of affected individuals, the majority of which were GBA1 variants (127/812; 15·6%). Eight different GBA1 variants were identified (Figure 2); rs3115534-G was most frequent (86/127 GBA1 carriers; 4 homozygous; overall frequency 10·6% [86/812]). LRRK2 variants were observed in 2·8% (23/812), mostly G2019S (17/23), and two carriers each of R1441C, R1628P, and G2385R. Two PD patients (0·25%) carried VPS35 D620N, one (0·1%) harbored a SNCA multiplication, and seven early-onset patients (0·9%) harbored biallelic PRKN variants (four homozygous deletions and three likely compound heterozygous). Among unaffected carriers (42/337; 12·5%), GBA1 variants were most frequent (36/337; 10·7%), particularly rs3115534-G (33/36 GBA1 carriers; 2 homozygous; overall frequency 9·8% [33/337]). Six asymptomatic LRRK2 carriers were identified (1·8%), three of which (all G2019S) were unaffected family members of PD patients (aged 45, 51, and 58 years).

Central Asian ancestry (753 affected and 370 unaffected individuals)

We observed pathogenic or risk variants in 6·2% (47/753) of affected individuals, most frequently GBA1 variants (30/753; 3·9%). Eight different GBA1 variants were detected, most commonly E365K (n=11) and T408M (n=9) (Figure 2). We identified LRRK2 variants in 1.6% (12/753); where the risk variants G2385R (n=8) and R1628P (n=3) were more frequent than pathogenic variants (R1441C, n=1). A subset (4/753; 0·5%) carried biallelic PRKN variants (three homozygous deletions and one likely compound heterozygous). Finally, twelve unaffected individuals (3·2%) carried GBA1 (n=9) or LRRK2 (n=3) risk variants.

East Asian ancestry (3,363 affected and 2,503 unaffected individuals)

Amongst identified affected variant carriers (613/3,363; 18·2%), more than two-thirds carried one or both LRRK2 risk variants R1628P and G2385R (439/3,363; 13·1%). Most were diagnosed with PD, while a subset (n=8) had atypical parkinsonism. Pathogenic LRRK2 variants were rare (10/3,363; 0·3%) and included R1067Q, R1441C, R1441H, and G2019S. GBA1 variants were observed in 3·4% (114/3,363), with a broad mutational spectrum including 29 distinct variants (Figure 2), most frequently L483P (33/114). 17 affected individuals (0·5%) harbored a risk variant in LRRK2 and GBA1. Other dominantly inherited genes with identified variant carriers were VPS35 D620N (n=3; 0·09%), SNCA (n=4; 0·1%), SLC20A2 (n=2; 0·06%), and DCTN1 (n=1; 0·03%). Additionally, 14 PD patients (0·4%) harbored biallelic PRKN variants (six homozygous deletions and six likely compound-heterozygous), and nine the homozygous PINK1 L347P variant. Three additional individuals carried PINK1 L347P and a LRRK2 risk variant, and seven unaffected individuals harbored L347P in the heterozygous state. Additionally, LRRK2 risk variants were identified in 8·7% (217/2,503) and GBA1 variants in 0·8% (19/2,503) of unaffected individuals, and one control (0·04%) harbored LRRK2 R1441C.

European ancestry (28,859 affected and 19,539 unaffected individuals)

We identified pathogenic or risk variants across 11 genes in 10·1% (2,925/28,859) of affected individuals. Most frequent were GBA1 variants (2,501/28,859; 8·7%), with 49 different identified variants (Figure 2), most commonly E365K (n=1,194) and T408M (n=755). 26 additional individuals (0·1%) were dual carriers of variants in GBA1 and another gene, mostly LRRK2. Single LRRK2 variants were observed in 0·9% (248/28,859). Eight different pathogenic variants were identified, most frequently G2019S (172/248), but also several other variants that were predominantly (R1325Q, R1441G/H/C) or exclusively (L1795F) identified in EUR individuals. We further identified carriers of SNCA multiplications (n=15) or coding variants (n=14) (29/28,859 in total, 0·1%), VPS35 D620N (n=4, 0·01%), and RAB32 S71R (n=7, 0·02%). In recessive genes, biallelic variants in PRKN were more frequent (63/28,859, 0·2%; 29 homozygous and 34 likely compound-heterozygous) than PINK1 variants (n=8; 0·03%), and only a single biallelic PARK7/DJ-1 E64D carrier was identified. Variants in atypical parkinsonism genes were observed in a subset (combined 7/28,859; 0·02%) and included DCTN1 (n=4), RAB39B (n=2), and WDR45 (n=1). All were diagnosed with PD. Finally, 5·1% (999/19,539) of unaffected individuals, including unaffected family members of PD patients, harbored variants in GBA1 (n=936; 4·8%), especially E365K and T408M, LRRK2 (n=54; 0·3%), SNCA (n=3; 0·02%), and PRKN (n=1; 0·01%).

Finnish ancestry (120 affected and 14 unaffected individuals)

Only GBA1 variants were identified in this ancestry. 11·7% of affected individuals (14/120) carried three different variants, E365K, T408M, and N409S (Figure 2), 13 diagnosed with PD and one with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). One unaffected individual (7·1%) harbored GBA1 T408M.

Middle Eastern ancestry (596 affected and 242 unaffected individuals)

Pathogenic or risk variants were identified in 13·4% (80/596) of affected individuals. Most frequent were pathogenic LRRK2 variants (42/596; 7·0%), particularly G2019S (35/42), and a subset (n=7) with R1441C. All LRRK2 variant carriers were diagnosed with PD. We identified 3·1% (19/596) harboring eleven different GBA1 variants (Figure 2). One E365K carrier with PSP, while all other GBA1 carriers were PD patients. Three additional PD patients (0·5%) harbored a pathogenic LRRK2 and a GBA1 variant. One PD patient carried RAB32 S71R, and one a SNCA multiplication (0·2% each). A notable proportion of individuals carried biallelic variants in the recessive genes PINK1 (n=10; 1·7%) and PRKN (n=4; 0·7%). One unaffected LRRK2 G2019S carrier was identified (1/242; 0·4%).

South Asian ancestry (499 affected and 235 unaffected individuals)

Pathogenic or risk variants were observed in 7·2% (36/499) of affected individuals, the majority of which were GBA1 carriers (29/499; 5·8%). Except for one PSP patient, all others had PD. The most frequent GBA1 variant was L483R (Figure 2), identified in 11 affected individuals and three unaffected family members of those (aged 40, 41, and 50 years, respectively). Further, one affected individual each carried a pathogenic (R1067Q) or LRRK2 risk (R1628P) variant (total LRRK2: 0·4%), and five individuals harbored biallelic PRKN variants (5/499; 1·0%).

Single heterozygous variants in recessively inherited genes

Across all ancestries, we identified 461 affected carriers of single heterozygous pathogenic variants in recessive genes, most frequently in PRKN (n=410), followed by PINK1 (n=16) and ATP13A2 (n=10), whereas variants in other genes were rare. Many carriers had an AAO ≤50 years (178/344, 51·7%; AAO missing for n=117). Three individuals carried two heterozygous PRKN variants but had an AAO >50 years, so we did not interpret them as likely compound heterozygous without further confirmation.

Discussion

We performed a comprehensive analysis of causative and risk variants in PD-associated genes across diverse populations. Our work represents the largest ancestry-informed assessments to date, including >30% of non-European ancestry individuals, offering insights into the population-specific genetic architecture of PD. This is important as multiple ongoing or planned clinical trials target proteins encoded by PD-linked genes.12,13 Ensuring these advances are inclusive requires a detailed understanding of genetic variation beyond European ancestry.14

The overall yield of causal variants across affected individuals was ~2%, with substantial variations across ancestries ranging from <0·5% in FIN, AAC, and AFR to >10% in MDE and AJ. Including risk variants raised the yield to ~13%, aligning with prior studies.15,16 This increase was largely driven by GBA1, except in EAS, where the LRRK2 risk variants R1628P and G2385R dominated.

GBA1 variants were most frequent overall and identified across all populations, notably with different variant spectra: N409S was the most common variant in AJ, while E365K and T408M were more frequent in EUR, FIN, and CAS, but rare in AFR and EAS. The variant spectrum in EAS was broad, but L483P appeared more frequent than in other populations. The intronic variant rs3115534-G was by far the most frequently observed in AAC, AFR, and CAH, as previously reported.17 These findings emphasize the importance of GBA1 as a globally relevant therapeutic target, an important observation given that most trials targeting glucocerebrosidase only include EUR or AJ individuals.4

LRRK2 variants also showed ancestral variability. G2019S was detected across multiple ancestries, with the highest frequencies in MDE (reflecting North African Berbers) and AJ.18,19 While G2019S was also the most frequent LRRK2 variant in EUR, the mutational spectrum was notably broader and included R1441C, R1441G, and L1795F with suggested founder effects in European sub-populations.20–23 In contrast, G2019S was largely absent from Asian populations, where the risk variants R1628P and G2385R dominated,24 especially in EAS. LRRK2 variants differ in their impact on kinase activity,25 which may inform clinical trial design and therapeutic targeting. Investigating these actionable variants globally is key, particularly given the ongoing LRRK2-targeted trials.

SNCA variants were overall rare but most frequently identified in EUR, with only sporadic carriers in other populations, in line with previous reports.26 While SNCA multiplications were identified in EUR, EAS, MDE, and CAH individuals, missense variants (almost exclusively A53T) were predominantly observed in EUR (almost 50% of all SNCA carriers).

Other known autosomal dominant forms of PD caused by VPS35 D620N or RAB32 S71R were rare. RAB32 variants were predominantly detected in EUR individuals, while VPS35 variant carriers were observed across three different populations, with a relatively higher proportion in EAS and CAH compared to EUR. Given the low sample size of some populations, especially with WGS data, these findings need cautious interpretation. Nonetheless, detecting VPS35 and RAB32 variants across multiple ancestries underscores the importance of continued investigation in larger, diverse cohorts.

Investigating recessive forms of PD across populations, we found PRKN to be the most frequently implicated gene, followed by PINK1, while only a single EUR DJ-1/PARK7 carrier was observed. Biallelic PRKN variants were identified across nearly all populations, except AJ and FIN. In Asian populations (EAS, CAS, and SAS), PRKN variants were more frequent than pathogenic LRRK2 variants, although this warrants cautious interpretation given the small sample sizes in some groups. SNVs and CNVs in PRKN were observed at similar frequencies; however, CNVs appeared more frequent in EAS and SNVs in EUR. Identifying PRKN carriers across multiple ancestries reinforces its global relevance, as preclinical efforts increasingly explore therapeutic strategies targeting Parkin (encoded by PRKN) or its associated pathways.12 While PINK1 variants were rare, we identified a notable proportion of MDE and EAS carriers. All EAS carriers harbored L347P, a variant known to be enriched in this population.27 We further identified numerous individuals carrying single heterozygous pathogenic variants in recessive PD genes. While these are not causative, many carriers had an early AAO ≤50 years, suggesting a second pathogenic variant, particularly a complex structural variant not captured by genotyping or short-read sequencing.

Limitations

Our study focused on variants in known PD genes, primarily identified in European populations. This and the predominance of European-ancestry data in resources like ClinVar may bias variant interpretation in non-European groups. While our study allowed for a large-scale, clinically relevant assessment of those known variants, it limits the discovery of novel PD genes and variants that may be more relevant in other populations. Systematically studying large, well-powered non-European ancestry cohorts using WGS-rich datasets will be important to capture the full global spectrum of novel variation. Another important area will be investigating variants of uncertain significance in known PD genes. Some variants may be pathogenic in specific populations but are currently classified as of uncertain significance due to limited ancestry-specific reference data and low statistical power. Ancestry-aware (re)classification using variant frequency, functional, and segregation data will be key for establishing pathogenicity, improving genetic counseling and enabling trial access.23,28

While our study is large and ancestrally diverse, some populations were of limited sample size. This may inflate the relative contribution of known genes in well-powered populations and is particularly relevant for groups with limited WGS data, since select variants are not captured by genotyping (e.g., RAB32 S71R and select GBA1 variants).

The detection of compound-heterozygous variants was limited by the absence of phased data. We conservatively considered carriers of two heterozygous pathogenic variants in recessive genes with an AAO ≤50 years as likely compound heterozygous, but validation is needed.

CNV analyses did not include all investigated samples, likely resulting in an underestimation of SNCA and PRKN carriers. Lastly, findings were generated in a research setting; while we employed quality control measures and WGS validation where possible, further confirmation is needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this is the largest study to date assessing the genetic spectrum of PD at a global level, offering crucial insights into the population-specific genetic architecture of PD and underscoring the critical need to expand PD genetics research beyond European ancestry. Ancestry-informed analysis improves diagnostic accuracy and risk interpretation and is essential to ensure equitable participation in clinical trials and access to emerging precision therapies. Addressing current gaps in data diversity is fundamental to fulfilling the promise of precision neurology on a global scale.

Supplementary Material

Putting research into context.

Evidence before this study

Genetic discoveries have drastically advanced our understanding of Parkinson’s disease (PD), including the identification of rare monogenic causes and common risk variants. However, according to our PubMed-based (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) literature review, the majority of genetic data has been generated in PD cohorts of European ancestry. The sample sets of two recent comprehensive, large-scale genetic screening studies, the PD GENEration North America and the Rostock International Parkinson’s disease (ROPAD) study, comprised 85% and 96% of White participants, respectively. Moreover, a global survey of monogenic PD, published in 2023, reported that 91% of genetically confirmed individuals with PD were of European ancestry, underscoring the major gap in ancestral representation in PD genetics research. Although ancestry-specific variants and founder effects have been reported for select PD-associated genes such as GBA1, LRRK2, and PINK1, comprehensive, globally- and ancestry-representative studies are missing, thereby constraining the applicability of genetic diagnostics and the development and inclusivity of equitable, ancestry-informed therapeutic strategies.

Added value of this study

This study, conducted within the framework of the Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2), represents the largest multi-ancestry exploratory genetic investigation of PD to date, including nearly 70,000 individuals from around the world, with more than 20,000 participants of non-European ancestry (representing ~30% of the study cohort). By exploring the genetic landscape of pathogenic variants in established PD-linked genes and PD risk-associated variants across 11 diverse genetically defined ancestry groups, it provides crucial insights into the global genetic landscape of PD. This work highlights both shared and ancestry-specific contributions and emphasizes the need to consider genetic diversity in research and clinical practice. Our findings highlight the importance of GBA1 as a globally relevant genetic contributor to PD risk, with variant carriers identified across all investigated populations, reinforcing it as a relevant therapeutic target across ancestries. Similarly, LRRK2 variant carriers, currently already targeted in clinical trials, and individuals with PRKN alterations, increasingly being explored as a therapeutic target in preclinical studies, were identified across multiple ancestral groups.

However, overall, investigating variants in known PD-linked genes resulted in substantially different yields across ancestries, underscoring the limited applicability of current PD gene and variant panels across ancestries and suggesting yet unexplored population-specific variations, especially in currently underrepresented populations, where newly identified variants in established PD-genes often remain of uncertain significance due to limited sample size and reference data.

Implications of all the available evidence

As precision medicine approaches are increasingly integrated into PD research and clinical trials, it is critical to ensure that emerging therapies are applicable and accessible to individuals of all ancestral backgrounds. Current trials targeting gene variant carriers predominantly enroll participants of European or Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, raising concerns about equity and efficacy in a global multi-ancestry context. This study underscores the importance of globally inclusive genetic efforts like GP2 to close these existing gaps, improve diagnostic equity, and enable more representative and effective implementation of precision neurology worldwide.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2; https://gp2.org). GP2 is funded by the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) initiative and implemented by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (MJFF). For a complete list of GP2 members see doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7904831.

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, project number ZO1 AG000535 and ZIA AG000949.

We thank Yuliia Kanana for her valuable support in processing and handling the samples used in this study. HH and RK are grateful for the important support from patients and families, UK and international collaborators, brainbank and biobanks.

Biospecimens used in the analyses presented in this article were obtained from the Northwestern University Movement Disorders Center (MDC) Biorepository. As such, the investigators within MDC Biorepository contributed to the design and implementation of the MDC Biorepository and/or provided data and collected biospecimens but may not have participated in the analysis or writing of this article. MDC Biorepository investigators include Rizwan Akhtar MD, PhD; Dimitri Krainc, MD, PhD, Tanya Simuni MD; Puneet Opal MD, PhD; Joanna Blackburn MD; Monika Szela MHA; and Lisa Kinsley MS, CGC.

Declaration of Interests

LML, SoB, MLD, PH, SJ, SUR, LS, CS, SS, EJS, AHT, ZT, NZ, KL, and SBC declare no relevant conflict of interests. LML received faculty honoraria from the Movement Disorder Society in the past 12 months, unrelated to this manuscript. ZHF is supported by the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2) and receives GP2 salary support from The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. MBM, NK, ShB, HI, LJ, MJK, HLL, KSL, DV, and MAN’s participation in this project was part of a competitive contract awarded to DataTecnica LLC by the National Institutes of Health to support open science research. MAN also currently serves on the scientific advisory board for Character Bio Inc plus is a scientific founder at Neuron23 Inc and owns stock. KAB and MT are supported by the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2). PH serves as an advisor to Alector Inc., the Global Parkinson’s Genetics Consortium (Michael J. Fox Foundation), LSP Advisory B.V., and Neuro.VC. HH and RK received essential funding from The Wellcome Trust, The MRC, The MSA Trust, The National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre NIHR-BRC), The Michael J Fox Foundation (MJFF), The Fidelity Trust, Rosetrees Trust, The Dolby Family fund, Alzheimer's Research UK (ARUK), MSA Coalition, The Guarantors of Brain, Cerebral Palsy Alliance, FARA, EAN and the NIH NeuroBioBank, Queen Square BrainBank, and The MRC Brainbank Network. JJ was supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation (Data Community Innovators Program). KRK is supported by the Ainsworth 4 Foundation and the Medical Research Future Fund. SYL received consultancies and grants from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s research (MJFF) and the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2). Unrelated to this manuscript, he received honoraria for participating as a Member of the Neurotorium Editorial Board and honoraria for lecturing/teaching from the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) and Medtronic. He also received stipends from the MDS as Chair of the Asian-Oceanian Section, and npj PD as Associate Editor. NEM receives NIH funding (1K08NS131581). He is supported by the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2) and is member of the steering committee of the PD GENEration study for which he receives an honorarium from the Parkinson’s Foundation. WMYM is the founding member and Chair of the AfrAbia Parkinson’s Disease Genomic Consortium (AfrAbia PD-GC), which is supported by funding from the Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2). AJN reports grants from Parkinson's UK, Barts Charity, Cure Parkinson’s, National Institute for Health and Care Research, Innovate UK, the Medical College of Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital Trust, Alchemab, Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (ASAP-GP2) and the Michael J Fox Foundation and consultancy and personal fees from AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Profile, Bial, Charco Neurotech, Alchemab, Sosei Heptares, Umedeor and Britannia. He is an Associate Editor for the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. RO has received travel grants from the Movement Disorder Society in the past 12 months, unrelated to this manuscript, and received research grants and travel support to attend annual GP2 meetings from the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2). NUO reports funding from MJFF and UK NIHR institutional grant funding, both for PD research. AHT receives support from the Michael J Fox Foundation and the Global Parkinson Genetic Program (GP2). Unrelated to this manuscript, she received speaker honoraria from International Parkinson and Movement Disorders, Eisai and Orion Pharma and reports consultancies from Elsevier as Section Editor for Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. JT is supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2), and is a consultant for Acurex. BT acknowledges support from the Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2). EMV is supported by the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2). Unrelated to this manuscript, she received research grants from Telethon Foundation Italy (GGP20070), the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata RF-2019-12369368 and ERA-NET Neuron NDCil project EUR002), the Italian Ministry of University and Research (GENERA, MNESYS) and the Silverstein Foundation. KL received grants from the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation and German Research Foundation (DFG), unrelated to this manuscript. CB is an employee of the Coalition for Aligning Science (CAS). AS is the lead investigator for a grant from the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and has a contract for work on the Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2). Unrelated to this manuscript, he is named as an inventor on patents for a diagnostic for stroke and for molecular testing for C9orf72 repeats; he is on the scientific advisory board of the Lewy Body Disease Association and for Cajal Neuroscience (both unpaid positions); and he received an honorarium for speaking at the World Laureates Association. HRM reports grant support from Parkinson’s UK, Cure Parkinson’s Trust, PSP Association, Medical Research Council, and the Michael J Fox Foundation. Unrelated to this manuscript, he is a co-applicant on a patent application related to C9orf72 - Method for diagnosing a neurodegenerative disease (PCT/GB2012/052140) and received honoraria from the Movement Disorder Society. CK received grants from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s Initiative. Unrelated to this manuscript, she received grants from the German Research Foundation and speakers’ honoraria from Bial. She has royalties at Oxford University Press and Springer Nature and serves as a medical advisor to Centogene and Biogen.

Funding:

Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Global Parkinson's Genetics Program (GP2)

Funding Statement

Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Global Parkinson's Genetics Program (GP2)

Data and Code Availability

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2; https://gp2.org). Specifically, we used Tier 2 data from GP2 releases 8 (DOI 10.5281/zenodo.13755496) and 9 (DOI 10.5281/zenodo.14510099). Tier 1 data can be accessed by completing a form on the Accelerating Medicines Partnership in Parkinson’s Disease (AMP®-PD) website (https://amp-pd.org/register-for-amp-pd). Tier 2 data access requires approval and a Data Use Agreement signed by your institution. Qualified researchers are encouraged to apply for direct access to the data through AMP PD.

All code generated for this article, and the identifiers for all software programs and packages used, are available on GitHub (https://github.com/GP2code/GP2-global-genetic-variant-landscape) and were given a persistent identifier via Zenodo (DOI 10.5281/zenodo.15699539).

A detailed list of all identified variant carriers, including corresponding anonymised GP2-IDs, variant details as well as basic demographic and clinical characteristics are available to qualified researchers and upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Lim S-Y, Klein C. Parkinson’s Disease is Predominantly a Genetic Disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2024; 14: 467–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonard HL, Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2). Novel Parkinson’s disease genetic risk factors within and across European populations. medRxiv. 2025; published online March 17. DOI: 10.1101/2025.03.14.24319455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lange LM, Gonzalez-Latapi P, Rajalingam R, et al. Nomenclature of Genetic Movement Disorders: Recommendations of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society Task Force - an update. Mov Disord 2022; 37: 905–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim S-Y, Tan AH, Ahmad-Annuar A, et al. Uncovering the genetic basis of Parkinson’s disease globally: from discoveries to the clinic. Lancet Neurol 2024; 23: 1267–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Junker J, Lange LM, Vollstedt E-J, et al. Team science approaches to unravel monogenic Parkinson’s disease on a global scale. Mov Disord 2024; 39: 1868–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vollstedt E-J, Schaake S, Lohmann K, et al. Embracing monogenic Parkinson’s disease: The MJFF Global Genetic PD cohort. Mov Disord 2023; 38: 286–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program. GP2: The Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program. Mov Disord 2021; 36: 842–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lange LM, Avenali M, Ellis M, et al. Elucidating causative gene variants in hereditary Parkinson’s disease in the Global Parkinson's Genetics Program (GP2). NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2023; 9: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vitale D, Koretsky MJ, Kuznetsov N, et al. GenoTools: An open-source Python package for efficient genotype data quality control and analysis. G3 (Bethesda) 2024; published online Nov 20. DOI: 10.1093/g3journal/jkae268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuznetsov N, Daida K, Makarious MB, et al. CNV-Finder: Streamlining copy number variation discovery. bioRxivorg. 2024; published online Nov 23. DOI: 10.1101/2024.11.22.624040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesage S, Lunati A, Houot M, et al. Characterization of recessive Parkinson’s disease in a large multicenter study. Ann Neurol 2020; 88: 843–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senkevich K, Rudakou U, Gan-Or Z. New therapeutic approaches to Parkinson’s disease targeting GBA, LRRK2 and Parkin. Neuropharmacology 2022; 202: 108822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McFarthing K, Buff S, Rafaloff G, et al. Parkinson’s disease drug therapies in the clinical trial pipeline: 2023 update. J Parkinsons Dis 2023; 13: 427–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schumacher-Schuh AF, Bieger A, Okunoye O, et al. Underrepresented populations in Parkinson’s genetics research: Current landscape and future directions. Mov Disord 2022; 37: 1593–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westenberger A, Skrahina V, Usnich T, et al. Relevance of genetic testing in the gene-targeted trial era: the Rostock Parkinson’s disease study. Brain 2024; 147: 2652–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook L, Verbrugge J, Schwantes-An T-H, et al. Parkinson’s disease variant detection and disclosure: PD GENEration, a North American study. Brain 2024; 147: 2668–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rizig M, Bandres-Ciga S, Makarious MB, et al. Identification of genetic risk loci and causal insights associated with Parkinson’s disease in African and African admixed populations: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol 2023; 22: 1015–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Otmani H, Daghi M, Tahiri Jouti N, Lesage S. An overview of the worldwide distribution of LRRK2 mutations in Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2023; 13: 335–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lesage S, Leutenegger A-L, Ibanez P, et al. LRRK2 haplotype analyses in European and North African families with Parkinson disease: a common founder for the G2019S mutation dating from the 13th century. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 77: 330–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorostidi A, Ruiz-Martínez J, Lopez de Munain A, Alzualde A, Martí Massó JF. LRRK2 G2019S and R1441G mutations associated with Parkinson’s disease are common in the Basque Country, but relative prevalence is determined by ethnicity. Neurogenetics 2009; 10: 157–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mata IF, Taylor JP, Kachergus J, et al. LRRK2 R1441G in Spanish patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Lett 2005; 382: 309–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nuytemans K, Rademakers R, Theuns J, et al. Founder mutation p.R1441C in the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 gene in Belgian Parkinson’s disease patients. Eur J Hum Genet 2008; 16: 471–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lange LM, Levine K, Fox SH, et al. The LRRK2 p.L1795F variant causes Parkinson’s disease in the European population. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2025; 11: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim S-Y, Tan AH, Ahmad-Annuar A, et al. Parkinson’s disease in the Western Pacific Region. Lancet Neurol 2019; 18: 865–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalogeropulou AF, Purlyte E, Tonelli F, et al. Impact of 100 LRRK2 variants linked to Parkinson’s disease on kinase activity and microtubule binding. Biochem J 2022; 479: 1759–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trinh J, Zeldenrust FMJ, Huang J, et al. Genotype-phenotype relations for the Parkinson’s disease genes SNCA, LRRK2, VPS35: MDSGene systematic review. Mov Disord 2018; 33: 1857–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel SG, Buchanan CM, Mulroy E, et al. Potential PINK1 founder effect in Polynesia causing early-onset Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2021; 36: 2199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim S-Y, Toh TS, Hor JW, et al. Clinical and functional evidence for the pathogenicity of the LRRK2 p.Arg1067Gln variant. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2025; 11: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2; https://gp2.org). Specifically, we used Tier 2 data from GP2 releases 8 (DOI 10.5281/zenodo.13755496) and 9 (DOI 10.5281/zenodo.14510099). Tier 1 data can be accessed by completing a form on the Accelerating Medicines Partnership in Parkinson’s Disease (AMP®-PD) website (https://amp-pd.org/register-for-amp-pd). Tier 2 data access requires approval and a Data Use Agreement signed by your institution. Qualified researchers are encouraged to apply for direct access to the data through AMP PD.

All code generated for this article, and the identifiers for all software programs and packages used, are available on GitHub (https://github.com/GP2code/GP2-global-genetic-variant-landscape) and were given a persistent identifier via Zenodo (DOI 10.5281/zenodo.15699539).

A detailed list of all identified variant carriers, including corresponding anonymised GP2-IDs, variant details as well as basic demographic and clinical characteristics are available to qualified researchers and upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.