Abstract

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the subarachnoid space around the brain drains to lymph nodes in the neck, but the connections and regulation have been challenging to identify1–24. Here we used fluorescent tracers in Prox1–GFP lymphatic reporter mice to map the pathway of CSF outflow through lymphatics to superficial cervical lymph nodes. CSF entered initial lymphatics in the meninges at the skull base and continued through extracranial periorbital, olfactory, nasopharyngeal and hard palate lymphatics, and then through smooth muscle-covered superficial cervical lymphatics to submandibular lymph nodes. Tracer studies in adult mice revealed that a substantial amount of total CSF outflow to the neck drained to superficial cervical lymph nodes. However, aged mice had fewer lymphatics in the nasal mucosa and hard palate and reduced CSF outflow to cervical lymph nodes. Superficial cervical lymphatics in aged mice had increased endothelial cell expression of Nos3, encoding endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), but had less eNOS protein and impaired nitric oxide signalling. Manipulation of superficial cervical lymphatics through intact skin by a force-regulated mechanical device doubled CSF outflow and corrected drainage impairment in aged mice. This manipulation increased CSF outflow by compressing superficial cervical lymphatics while having little effect on their normal spontaneous contractions. Overall, the findings highlight the importance of superficial cervical lymphatics for CSF outflow and the potential for reversing CSF drainage impairment by non-invasive mechanical stimulation.

Subject terms: Ageing, Cardiovascular biology

The outflow pathway of cerebrospinal fluid into lymph nodes in the neck and how non-invasive mechanical stimulation can enhance drainage and restore impaired outflow in aged mice are explored.

Main

CSF provides mechanical protection and clears neurotransmitters, metabolites, and amyloid-β, tau and other protein aggregates from the central nervous system17,19,24. Claims that diminished secretion or impaired clearance of CSF can contribute to impaired brain function in ageing, Alzheimer disease or other neurodegenerative disorders have promoted interest in gaining a better understanding of factors that regulate CSF outflow12,25–28, but the underlying pathophysiology and potential approaches for ameliorating these conditions by manipulating CSF drainage29,30 are at an early stage of understanding.

After the landmark study by Key and Retzius in 1875 (ref. 1), CSF drainage from meningeal lymphatics to lymphatics and lymph nodes in the head and neck was then confirmed in many subsequent studies2–11,13–18,21,31 by using diverse approaches including injection of carbon particles, Microfil silicone rubber, dyes or other substances into the subarachnoid space (SAS) and then observing the tracers in nasal lymphatics and cervical lymph nodes4,5,7,8. Recent studies using Prox1–GFP mice32, immunohistochemistry, confocal microscopy and magnetic resonance imaging have further characterized the connections between the SAS and lymphatics in the dura around the olfactory bulb, cribriform plate, nasal mucosa and nasopharynx14,20–23.

Findings that CSF clearance can be manipulated by expanding or reducing meningeal lymphatic networks have raised new therapeutic possibilities15,25,26,29,30,33. Through vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C)–vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3) signalling modulation15,29,30 or photodynamic destruction25,26, studies have shown that increasing CSF clearance can reduce the severity of ischaemic or traumatic stroke and other neurological conditions, including migraines34,35. Beyond the therapeutic applications, questions remain about how CSF crosses the arachnoid barrier to reach dural lymphatics. Although openings have been reported near olfactory nerves and the cribriform plate22,23 and along bridging veins near dural venous sinuses36, further work is needed to understand the cellular nature of these openings and how different conditions affect drainage routes.

In a previous study, we identified the pathway of CSF clearance from the SAS through dural lymphatics to deep cervical lymph nodes23. This pathway, through the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus to deep cervical lymph nodes, carried about half of the CSF outflow to the neck23. With the goal of developing approaches for increasing CSF outflow, we found that local pharmacological manipulation of the lymphatics promoted greater CSF outflow23. However, a limitation was that surgical exposure was required to access these lymphatics located deep in the neck, which were inaccessible to non-invasive approaches for increasing CSF transport by mechanical manipulation through the skin.

To address this limitation, in the present study, we found that superficial cervical lymphatics (scLVs) were responsive to non-invasive manipulation. By using fluorescent CSF tracers in Prox1–GFP lymphatic reporter mice and in monkeys, we learned that CSF in the SAS drained through scLVs to submandibular lymph nodes after passing through meningeal lymphatics in the frontal and basal region of the skull to extracranial periorbital, nasal and hard palate lymphatics. We then learned that the contractile apparatus of the collecting lymphatics of the scLV pathway remained normal in aged mice, despite the atrophy of upstream lymphatics and impaired CSF outflow. To take advantage of the location and intact contractility of the scLV pathway, we developed a non-invasive approach for correcting the impairment in aged mice by increasing CSF outflow with a force-regulated mechanical stimulator on the intact skin. Experiments with aged mice revealed that the approach largely normalized CSF outflow through scLVs to lymph nodes.

CSF outflow via scLVs

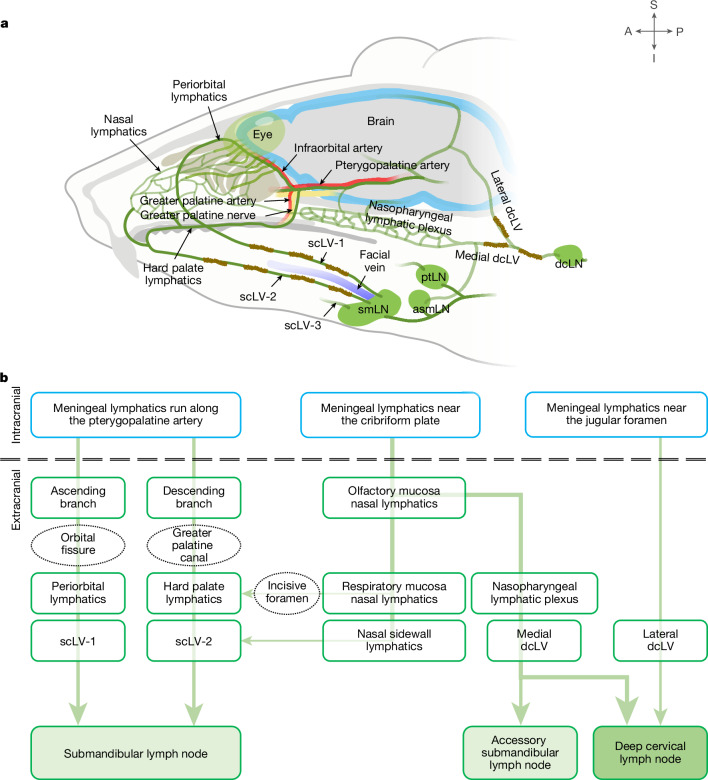

In the neck of mice, scLVs drain to the submandibular, accessory submandibular and parotid lymph nodes, and deep cervical lymphatics (dcLV) drain to the deep cervical lymph node (Fig. 1a,b). Examination of 77 Prox1–GFP mice revealed that the three superficial cervical lymph nodes were consistently present, but the accessory submandibular lymph node had variable locations in relation to the others, as reflected by the classification of type 1 (61.0%; accessory combined with submandibular), type 2 (31.2%; accessory separate from other nodes) or type 3 (7.8%; accessory combined with parotid; Extended Data Fig. 1a–c).

Fig. 1. Overview of CSF drainage from meningeal lymphatics to cervical lymphatics and lymph nodes.

a,b, Drawing (a) and flow chart (b) illustrating the complex lymphatic system for CSF drainage from meningeal lymphatics through multiple lymphatic pathways to superficial and deep cervical lymph nodes. (1) Meningeal lymphatics that run along the pterygopalatine and infraorbital arteries traverse the orbital fissure to join periorbital lymphatics that carry CSF through scLV-1 to the submandibular lymph node (smLN). (2) Some meningeal lymphatics that run along the pterygopalatine artery, greater palatine artery and greater palatine nerve traverse the greater palatine canal to join the hard palate lymphatic plexus en route to scLV-2 that drains CSF to the smLN. (3) Meningeal lymphatics near the olfactory bulb traverse the cribriform plate and join lymphatics in the nasal mucosa and nasal sidewall that carry CSF to scLV-2 en route to the smLN. Alternatively, nasal lymphatics traverse the incisive foramen to join the hard palate lymphatic plexus en route to scLV-2 and the smLN. (4) Other meningeal lymphatics near the olfactory bulb traverse the cribriform plate and join nasal lymphatics connected to the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus that carries CSF to medial dcLV en route to the accessory submandibular (asmLN) or deep cervical lymph node (dcLN). (5) Meningeal lymphatics at the base of the skull that traverse the jugular foramen join lateral dcLV en route to the dcLN. (6) The parotid lymph node (ptLN) does not receive CSF drainage. Anatomical positions are indicated in the top right corner. A, anterior; I, inferior; P, posterior; S, superior.

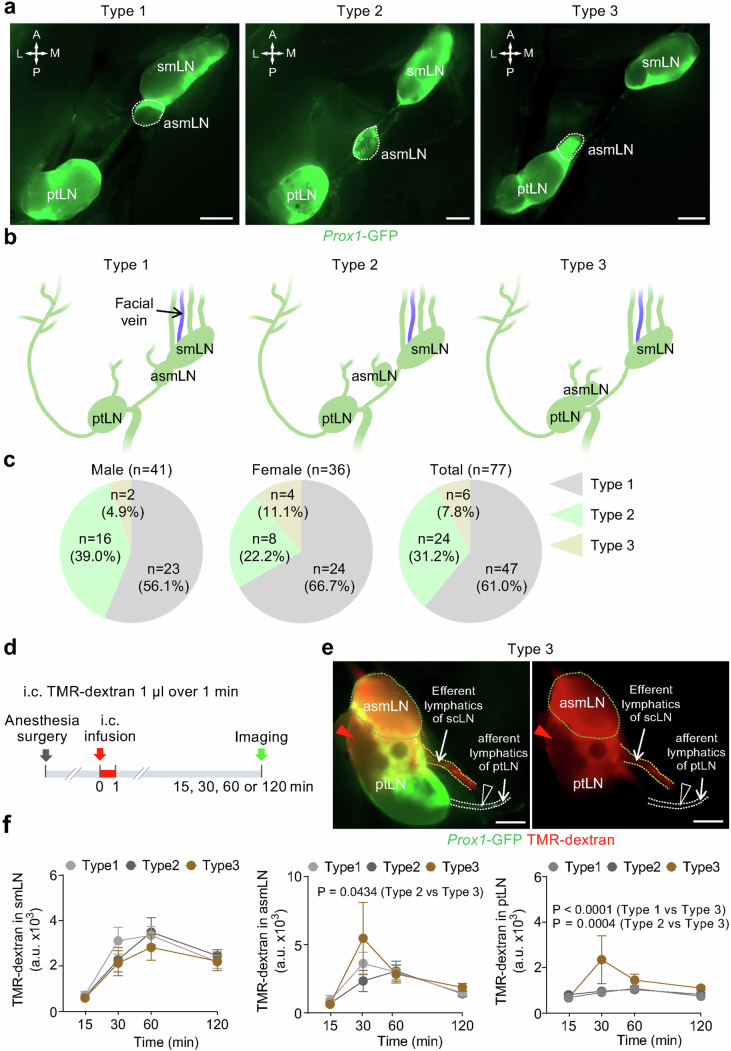

Extended Data Fig. 1. Variability in relative positions of superficial cervical lymph nodes.

a-c, Fluorescence images and drawings of the three types of superficial cervical lymph nodes defined by the relationship of the accessory submandibular lymph node (asmLN, white dashed line) to neighboring lymph nodes in Prox1-GFP mice (a,b). Type 1, asmLN is fused with the submandibular lymph node (smLN). Type 2, asmLN is separated from both smLN and the parotid lymph node (ptLN). Type 3, asmLN is fused with ptLN. Anatomical positions are indicated in the top left corner (a): A, anterior; P, posterior; M, medial; L, lateral. Scale bars, 1 mm. Drawings illustrate the relationship of asmLN to other lymph nodes (b). Pie charts showing the percentage of the three types of asmLN in male (n = 41), female (n = 36), and all (n = 77) mice (c). d-f, Sequence of intracisternal (i.c.) infusion of 1.0 μl TMR-dextran over 1 min into Prox1-GFP mice followed 15, 30, 60, or 120 min later by measurement of TMR-dextran fluorescence in superficial cervical lymph nodes (d). Fluorescence images representative of n = 7 mice showing TMR-dextran distribution in asmLN (green dashed line) and ptLN components of a Type 3 superficial cervical lymph node at 30 min after intracisternal infusion (e). TMR-dextran fluorescence in (i) asmLN and the adjacent region of ptLN (red arrowheads) and in (ii) efferent lymphatics (orange dashed lines) but not in (iii) afferent lymphatics of ptLN (blank arrowheads) at 30 min after intracisternal infusion (e). Scale bars, 500 μm. Measurements of temporal changes in TMR-dextran fluorescence in Type 1, Type 2, and Type 3 superficial cervical lymph nodes after intracisternal infusion (f). Each dot represents the mean value of superficial cervical lymph nodes on one side of n = 3-5 mice for 15 min, n = 7-19 mice for 30 min, n = 10-15 mice for 60 min, and n = 6-17 mice for 120 min. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. a.u., arbitrary unit. P values calculated by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

To determine which of these lymph nodes received CSF drainage, we infused 1 μl of 10 kDa tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated dextran (TMR–dextran) in PBS over 1 min into the SAS at the cisterna magna of anaesthetized Prox1–GFP mice (Fig. 2a). TMR–dextran fluorescence was examined and measured in scLVs at 30 min and 60 min (Fig. 2b–e) and in the superficial cervical lymph nodes at 15–120 min (Fig. 2f,g). TMR–dextran fluorescence was strong in the submandibular, accessory submandibular and deep cervical lymph nodes and had an unambiguous pattern in types 1 and 2 lymph nodes. No tracer was visible in parotid lymph nodes (Fig. 2f), except in the type 3 group, where the tracer was detected in the accessory submandibular lymph node and the adjacent rostral region of the parotid lymph node at 30 min after intracisternal tracer infusion (Extended Data Fig. 1d–f), indicative of functional coupling of the fused lymph nodes.

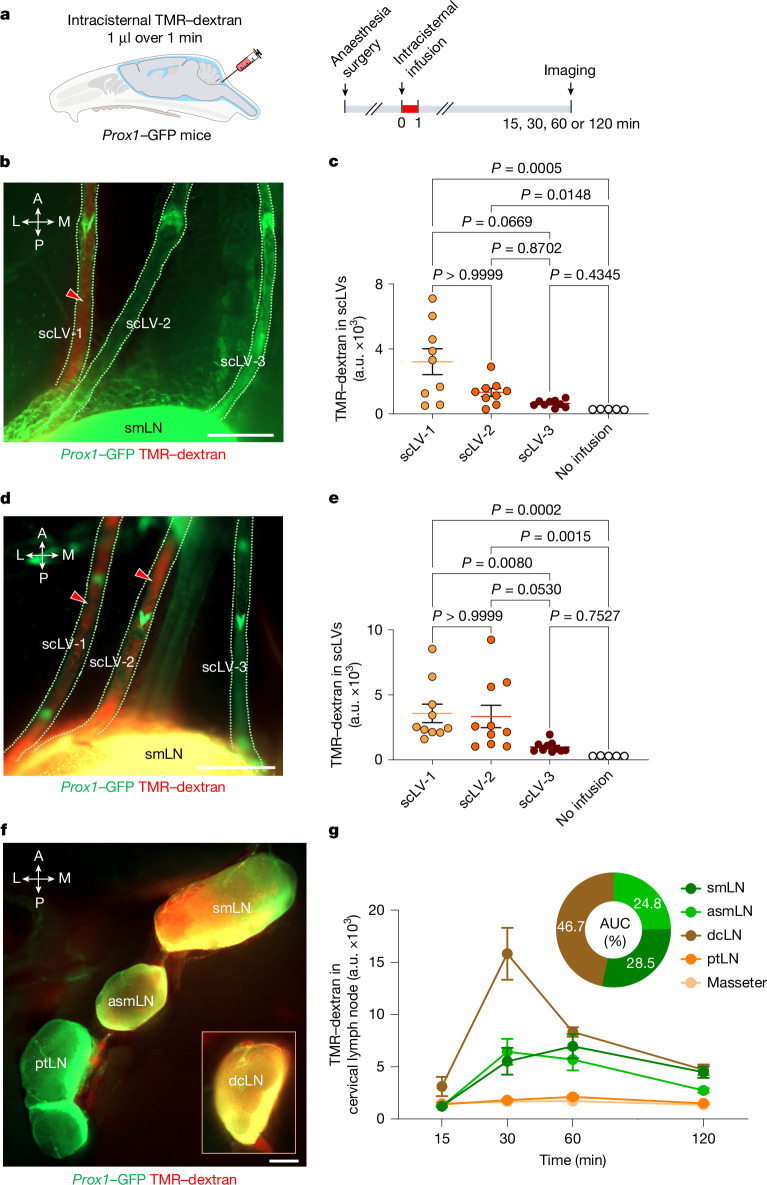

Fig. 2. TMR–dextran distribution in scLVs and lymph nodes after intracisternal infusion.

a, Sequence of intracisternal infusion of 1.0 μl TMR–dextran over 1 min into Prox1–GFP mice followed 15, 30, 60 or 120 min later by measurement of TMR–dextran fluorescence in scLVs and draining lymph nodes. b–e, Images (b,d) and measurements (c,e) of TMR–dextran fluorescence in three scLVs that join the smLN. At 30 min after intracisternal infusion, TMR–dextran fluorescence (red arrowheads) is strong in scLV-1 (b), but at 60 min is strong in scLV-1 and scLV-2 (d), yet is essentially absent in scLV-3 at either time point (b,d); measurements support these findings (c,e). Scale bars, 200 μm. Each dot represents one mouse (n = 5 for no infusion, n = 9 for scLV-1, scLV-2 or scLV-3 at 30 min and n = 10 for scLV-1, scLV-2 or scLV-3 at 60 min) from three independent experiments. The error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated by Kruskal–Wallis test followed by two-tailed Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc test. a.u., arbitrary unit. f,g, Images (f) and measurements (g) of temporal changes of TMR–dextran fluorescence in type 1 and type 2 superficial cervical lymph nodes, the dcLN (inset) and the masseter muscle. TMR–dextran fluorescence (red) is strong in all lymph nodes but is not evident in the ptLN (f). Scale bar, 500 μm. The curves show the tracer fluorescence intensity at the four time points. Each dot is the mean value for n = 4–12 mice per group from three independent experiments. The pie chart compares the amounts of tracer fluorescence in the smLN, asmLN and dcLN expressed as the percent of their area under the time-course curve (AUC; g). The error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. Anatomical positions are indicated in the top left corner. L, lateral; M, medial.

The amount of TMR–dextran fluorescence in the submandibular and accessory submandibular lymph nodes combined (53%) was similar to the amount in the deep cervical lymph node (47%), when expressed as the proportion of total fluorescence in these nodes over the period of 15–120 min after intracisternal infusion (Fig. 2g). The measurements revealed that superficial cervical and deep cervical lymph nodes each received about half of the CSF drainage to lymph nodes in the neck of mice.

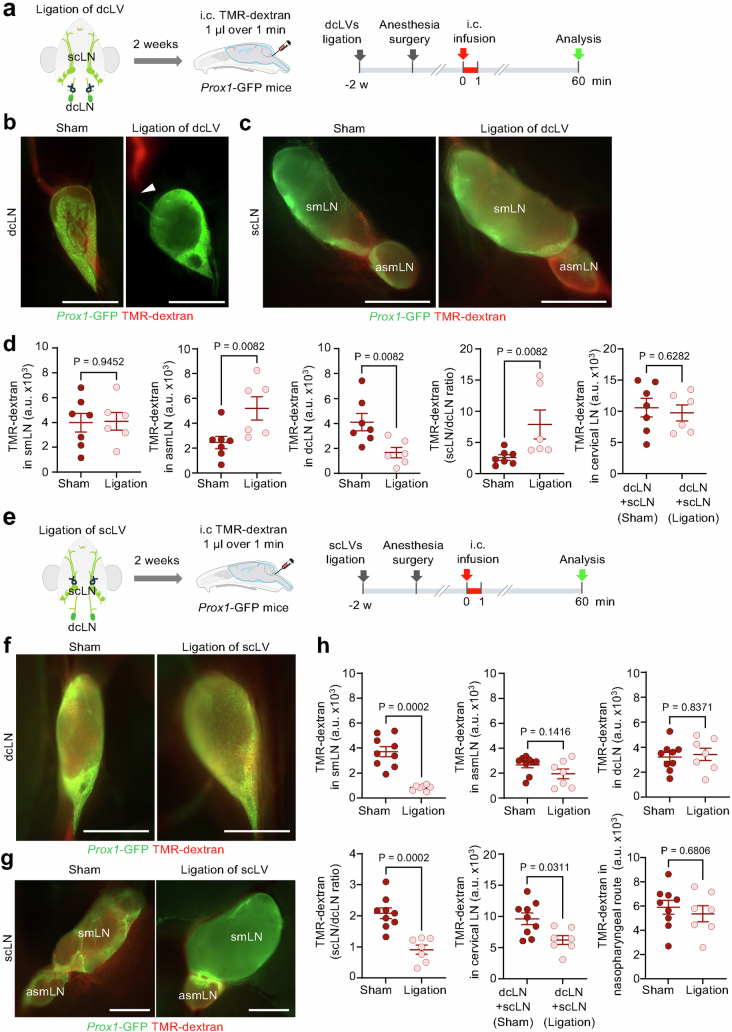

The amount of CSF drainage to individual cervical lymph nodes changed with the conditions. Ligation of dcLV shifted the drainage from deep to superficial cervical lymph nodes, as reflected by reduction in CSF tracer in the deep node and increase in the accessory submandibular lymph node (Extended Data Fig. 2a–d). By comparison, ligation of scLVs reduced overall CSF drainage to all cervical lymph nodes by only approximately 35%. This modest reduction was the result of a large decrease in CSF drainage to submandibular lymph nodes, but no change in drainage to the accessory submandibular and deep cervical lymph nodes (Extended Data Fig. 2e–h). This was explained by the latter lymph nodes receiving CSF mainly through the nasopharyngeal lymphatic route (Fig. 1b). These effects illustrated the potential for maintaining CSF drainage by increasing outflow through a lymphatic route after obstruction of another route, but the differences showed the importance of selective targeting of the manipulations.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Compensatory redistribution of CSF drainage after ligation of either deep or superficial cervical lymphatics.

a, Sequence for intracisternal (i.c.) infusion of 1 µl TMR-dextran over 1 min into Prox1-GFP mice 2 wk after ligation of deep cervical lymphatics (dcLV) on both sides. The fluorescence intensity of the deep cervical (dcLN) and superficial cervical lymph nodes (scLN) was measured at 60 min after TMR-dextran infusion. b,c, Fluorescence images of dcLN, submandibular lymph node (smLN, left) and accessory submandibular lymph nodes (asmLN, right) after ligation of the deep cervical lymphatics (dcLV). TMR-dextran accumulated in the dcLN in the sham group but not in the ligation group. However, TMR-dextran fluorescence in the asmLN is stronger in the ligation group than in the sham group. Scale bars, 1 mm. Representative of n = 6-7 mice from three independent experiments. d, Comparison of TMR-dextran signal intensity in smLN, asmLN, dcLN, scLN/dcLN ratio, and cervical LN. Compensation in CSF drainage among cervical lymph nodes at 2 wk after ligation of deep cervical lymphatics (dcLV) shown by similar CSF drainage to cervical lymph nodes (sum of TMR-dextran fluorescence intensity for superficial and deep cervical lymph nodes) without ligation (sham, left) and with ligation (right) and increased ratio of TMR-dextran fluorescence in superficial to deep cervical lymph nodes with ligation. Each dot is the value for one mouse. Sham (n = 7 mice), dcLV ligation (n = 6 mice) from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. a.u., arbitrary unit. P values calculated by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test. e, Sequence for intracisternal (i.c.) infusion of 1 µl TMR-dextran over 1 min into Prox1-GFP mice at 2 weeks after ligation of superficial cervical lymphatics (scLV) on both sides. The fluorescence intensity of the deep cervical (dcLN) and superficial cervical lymph nodes (scLN) was measured at 60 min after TMR-dextran infusion. f,g, Strong TMR-dextran fluorescence (red) in a deep cervical lymph node (dcLN, f) and accessory submandibular lymph node (asmLN, g), with or without (sham) ligation of scLV. However, red fluorescence is evident in a submandibular node (smLN) in the sham but not after scLV ligation (g). Scale bars, 1 mm. Representative images of n = 7-9 mice from three independent experiments. h, Measurements of TMR-dextran fluorescence in smLN, asmLN, and dcLN with or without scLV ligation. Also shown are corresponding calculated values for the ratio of superficial to deep lymph nodes (scLN/dcLN), sum of deep and superficial cervical lymph nodes (dcLN + scLN), and nodes downstream of the nasopharyngeal lymphatic drainage route (asmLN + dcLN, as shown in Fig. 1). ScLV ligation resulted a large reduction in TMR-dextran in smLN (and corresponding reduction in dcLN + scLN) but no reduction in asmcLV or dcLN due to continued patency of the nasopharyngeal route. Each dot is the value for one mouse. Sham (n = 9 mice) and scLV ligation (n = 7 mice) from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. a.u., arbitrary unit. P values calculated by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test.

To determine whether CSF drainage to cervical lymph nodes of mice was similar in primates, we infused 2.5 ml of fluorescent 0.5-µm beads (FluoSpheres) in PBS over 10 min into the SAS at the cisterna magna of anaesthetized Macaca fascicularis monkeys (Extended Data Fig. 3a). At 180 min, FluoSpheres were abundant in submandibular and retropharyngeal (deep cervical lymph node in mice) lymph nodes, but not in the parotid lymph node (Extended Data Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 1a). FluoSpheres were also abundant near the greater palatine and incisive foramina in the hard palate (Extended Data Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 1b,c).

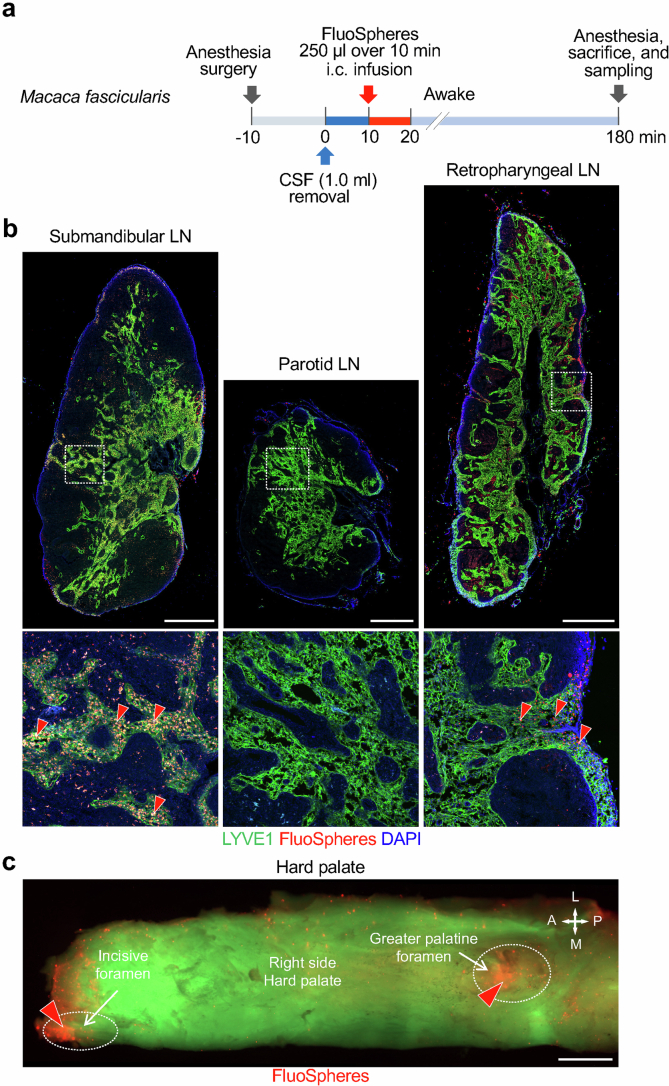

Extended Data Fig. 3. FluoSpheres distribution in cervical lymph nodes and hard palate of monkeys after infusion into cisterna magna.

a, Sequence of intracisternal (i.c.) infusion of FluoSpheres into Macaca fascicularis monkeys at 2.5 ml over 10 min followed by measurement of FluoSpheres in cervical lymph nodes and hard palate at 180 min. Before infusion, 1 ml of CSF was removed at the cisterna magna over 10 min. Anesthesia was administered until the end of the infusion and then readministered at 180 min. b, Immunofluorescence images showing the distribution of FluoSpheres (red) and LYVE1+ vessels in submandibular, parotid, and retropharyngeal lymph nodes (LN). White dashed line boxes mark regions enlarged in panels below. Red arrowheads mark regions with abundant FluoSpheres in lymph node medullary sinusoids. Scale bars, 1 mm. Representative of n = 2 monkeys from two independent experiments. c, Fluorescence image showing the distribution of FluoSpheres (red) in the right-side of the hard palate of a Macaca fascicularis monkey. FluoSpheres (red arrowheads) are abundant near the incisive and greater palatine foramina (white dashed ellipses) in the hard palate. Scale bar, 5 mm. Representative of n = 2 monkeys from two independent experiments. Anatomical positions are indicated in the top right corner: A, anterior; P, posterior; M, medial; L, lateral.

Submandibular lymph nodes had three afferent lymphatic trunk vessels, designated scLV vessels scLV-1, scLV-2 and scLV-3, in two-thirds of male and female mice (Fig. 2b,d, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Video 1). A fourth afferent lymphatic, scLV-4, was found in one-third of the mice. The diameter and length of the lymphatic segment between valves (lymphangion) of scLV-1 and scLV-2 were similarly variable and lacked sex differences (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b).

scLV-1 and scLV-2 had a dense but uneven layer of circular smooth muscle cells that stained for α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA+) along their entire length (Supplementary Fig. 3c,d). Smooth muscle coverage was greater in the middle of lymphangions than near the valves in both sexes (Supplementary Fig. 3e). These features of the lymphatics match the features of contractile lymphangions (‘lymphangion pumps’) that propel CSF outflow unidirectionally37,38.

TMR–dextran was visible in scLV-1, but rarely in scLV-2, at 30 min after the intracisternal infusion and was visible in both lymphatics at 60 min but was not detected in scLV-3 at either time (Fig. 2b–e). However, when Alexa-647-conjugated ovalbumin was infused into the floor of the mouth while TMR–dextran was infused intracisternally (Supplementary Fig. 4a), strong Alexa-647-conjugated ovalbumin fluorescence was detected in scLV-3 and in the upper portion of the submandibular lymph node (Supplementary Fig. 4b–d). At 60 min after intracisternal infusion, TMR–dextran was found in a branch from the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus23 that drained to the accessory submandibular lymph node (Extended Data Fig. 4). All superficial cervical lymph nodes drained into common efferent lymphatics (Extended Data Fig. 4e).

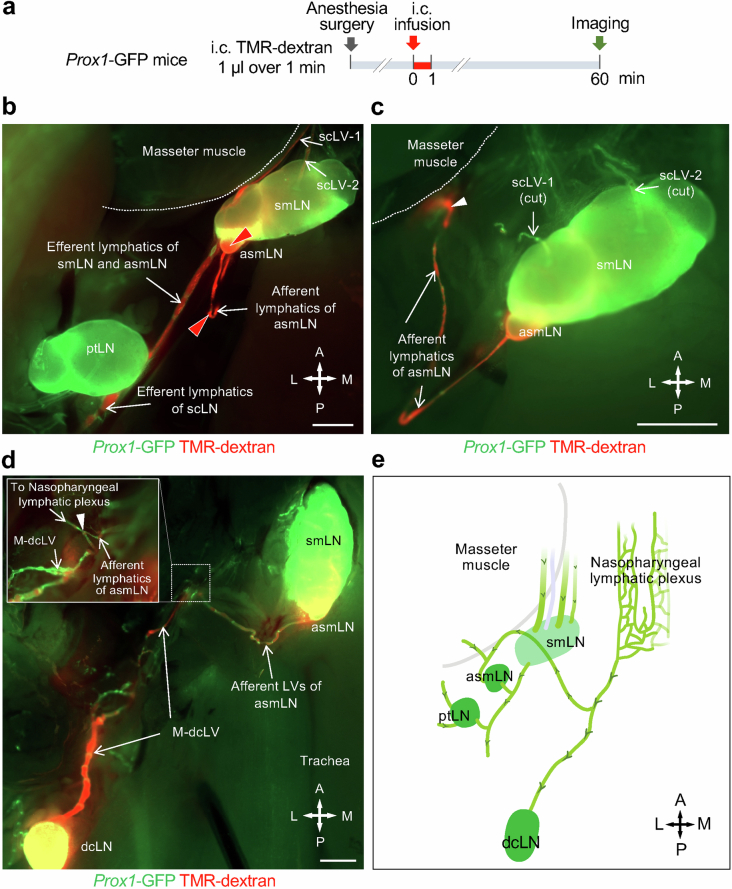

Extended Data Fig. 4. Lymphatic connection of nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus to accessory submandibular lymph node.

a, Sequence of intracisternal (i.c.) infusion of 1.0 μl TMR-dextran over 1 min into Prox1-GFP mice followed by imaging of TMR-dextran in superficial cervical lymphatics and lymph nodes 60 min later. b,c, Fluorescence image of Prox1-GFP mouse showing TMR-dextran (red) in superficial cervical lymphatics scLV-1 and scLV-2, submandibular (smLN) and accessory submandibular (asmLN) lymph nodes, and efferent lymphatics from these lymph nodes but not in the parotid lymph node (ptLN) (b). Lymphatics near the masseter muscle (white arrowhead) en route to asmLN (c). White dashed lines mark the border of the masseter muscle. Scale bars, 1 mm. Representative of n = 4 mice from four independent experiments. d, Fluorescence image showing the connections of medial deep cervical lymphatics (M-dcLV) and lymphatics that drain into the accessary submandibular lymph node (asmLN). White dashed line boxes marks the connecting point (white arrowhead) and the enlargement of this region. TMR-dextran fluorescence (red) is strong in M-dcLV and afferent lymphatics of asmLN and in the deep cervical lymph node (dcLN) and asmLN. Scale bars, 1 mm. Representative of n = 4 mice from four independent experiments. e, Drawing summarizing the lymphatic connections of the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus and the downstream accessory submandibular (asmLN) and deep cervical (dcLN) lymph nodes. The submandibular (smLN) and parotid (ptLN) lymph nodes are not downstream of the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus. Anatomical positions are indicated in the bottom right corner: A, anterior; P, posterior; M, medial; L, lateral.

Together, these observations revealed that the submandibular lymph node received CSF drainage through scLV-1 and scLV-2 but not through scLV-3, which received lymph from the floor of the mouth. By contrast, the accessory submandibular lymph node received CSF drainage from the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus (Extended Data Fig. 4e). On the basis of these findings, we focused our attention on scLV-1 and scLV-2 in subsequent studies.

Physiological properties of scLV-1 and scLV-2 were assessed in vivo and ex vivo (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6), as previously described39–41. Similar spontaneous contractions were found in scLV-1 and scLV-2 in anaesthetized adult mice of both sexes (Supplementary Fig. 5b,c), consistent with a recent report42. After isolation, scLV-1 and scLV-2 actively contracted ex vivo in response to pressures ranging from 0.5 to 10 cmH2O (Supplementary Fig. 6), as reported for other lymphatics in mice39.

Upstream connections of the scLV

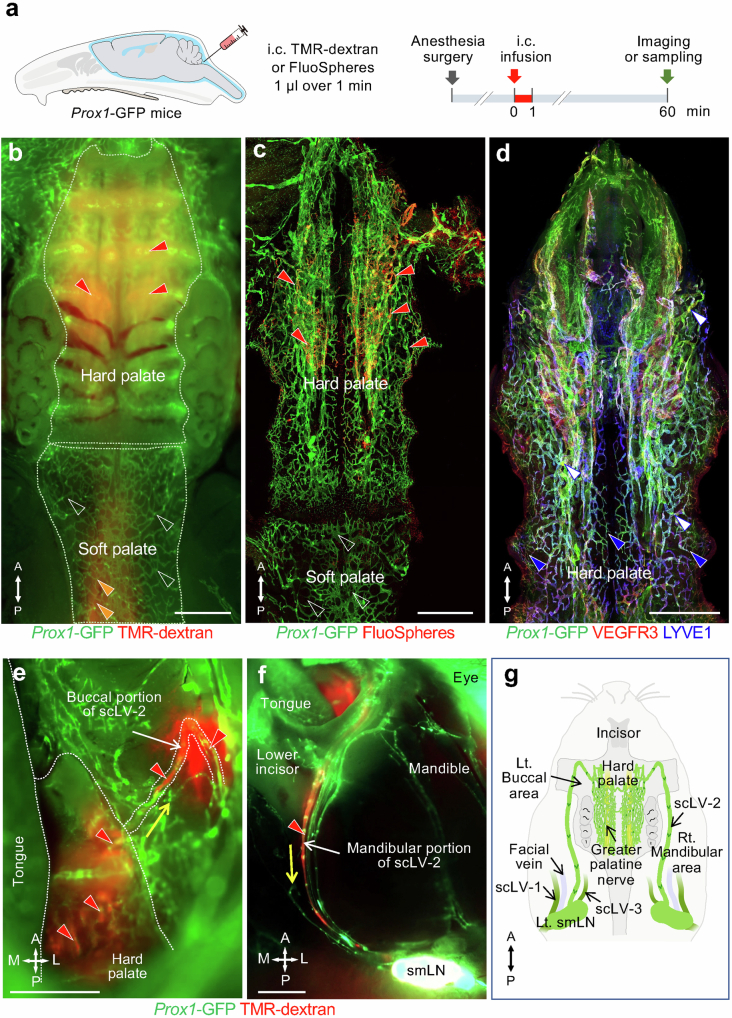

The upstream connections of scLV-1 and scLV-2 were identified by infusing TMR–dextran, FluoSpheres or Qdots into the SAS at the cisterna magna of Prox1–GFP mice and then examining the distribution of the tracer in dural lymphatics (intracranial) and head and neck lymphatics (extracranial) at 20, 30 or 60 min (Fig. 3, Extended Data Figs. 5–7 and Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). Tracer-containing lymphatics upstream to scLV-1 included the ascending branch of dural lymphatics that ran along the pterygopalatine artery intracranially and joined extracranial periorbital lymphatics (Fig. 3a–e and Extended Data Figs. 5e and 6a–c). Two networks of dural lymphatics were upstream to scLV-2. One network was near the olfactory bulb, traversed the cribriform plate and joined extracranial lymphatics of the olfactory mucosa and nasal side wall23 (Fig. 3f,g, Extended Data Fig. 6a,d–j and Supplementary Fig. 7). The other network accompanied the pterygopalatine artery and joined the descending branch of meningeal lymphatics that ran along the greater palatine artery and greater palatine nerve (Extended Data Figs. 5 and 6b,c). Part of the nasal lymphatics transverses the incisive foramen and joined extracranial lymphatics in the hard palate, without connections to lymphatics in the soft palate (Fig. 1a,b, Extended Data Figs. 5 and 7 and Supplementary Fig. 8).

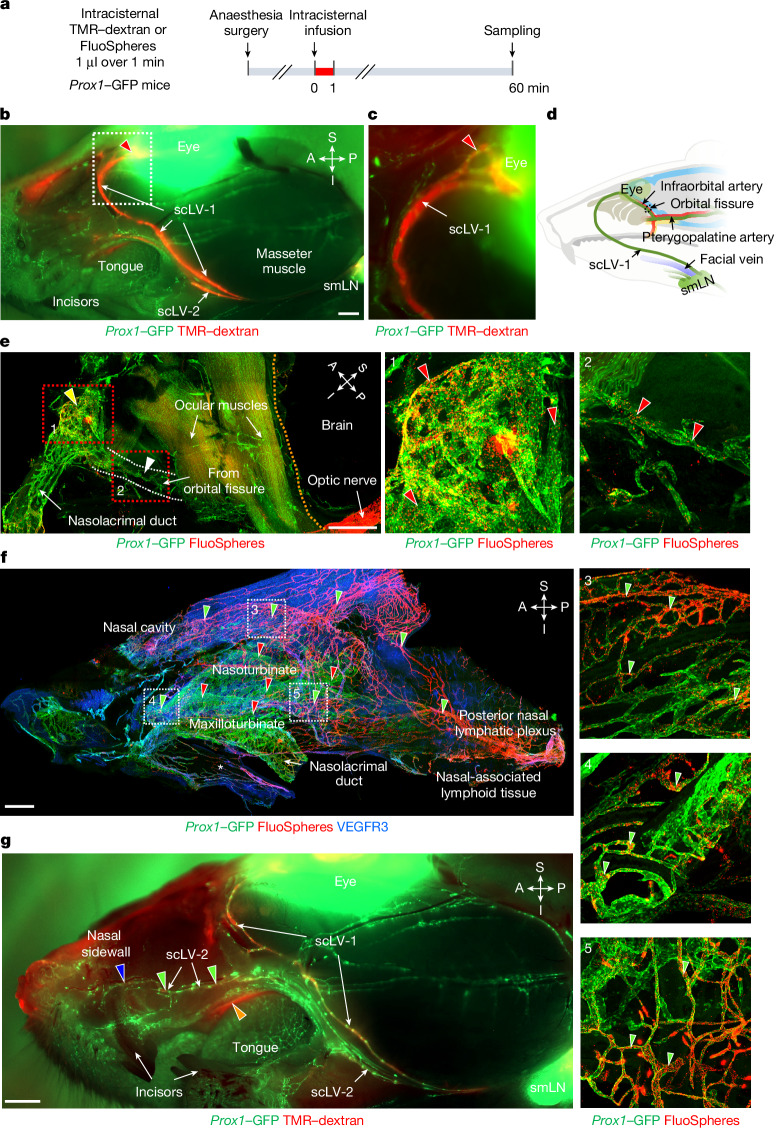

Fig. 3. CSF drainage through periorbital, nasal and hard palate lymphatics to the submandibular lymph node.

a, Sequence of intracisternal infusion of 1.0 μl TMR–dextran or FluoSpheres over 1 min into Prox1–GFP mice with analysis at 60 min. b,c, Fluorescence images of TMR–dextran (red) in head and neck lymphatics after removal of facial skin. The TMR–dextran signal is strong in scLV-1, scLV-2 and the periorbital region (red arrowhead). The white dashed line box marks the region enlarged in panel c. Scale bar, 1 mm. Representative of n = 4 mice from three independent experiments. d, Drawing showing the CSF drainage route from meningeal lymphatics near the orbit to the submandibular lymph node. e, Immunofluorescence images of FluoSpheres in periorbital (yellow arrowhead) and orbital fissure (white arrowhead) lymphatics. The white dashed lines indicate the lymphatic pathway from the orbital fissure. The orange dashed line marks the intracranial–extracranial boundary. The red dashed line boxes mark regions enlarged in panels showing that FluoSpheres (red) are abundant in periorbital (panel 1) and orbital fissure (panel 2) lymphatics (red arrowheads). Scale bar, 1 mm. Representative of n = 4 mice from three independent experiments. f, Immunofluorescence images of FluoSpheres in nasal lymphatics at 60 min after intracisternal infusion. In the nasal mucosa, FluoSpheres (red) are abundant in lymphatics (green arrowheads) but not in venous sinusoids (red arrowheads; also PROX1+). The white boxes in panel f are enlarged in panels 3–5. The white asterisk in panel f marks the junction of the nasal mucosa and hard palate. Scale bar, 500 µm. Representative of n = 5 mice from three independent experiments. g, Fluorescence image showing TMR–dextran (red) in nasal sidewall lymphatics (blue arrowhead), hard palate (orange arrowhead), and scLV-1 and scLV-2 (green arrowheads). Scale bar, 1 mm. Representative of n = 4 mice from three independent experiments. Anatomical positions are indicated in the top right corner.

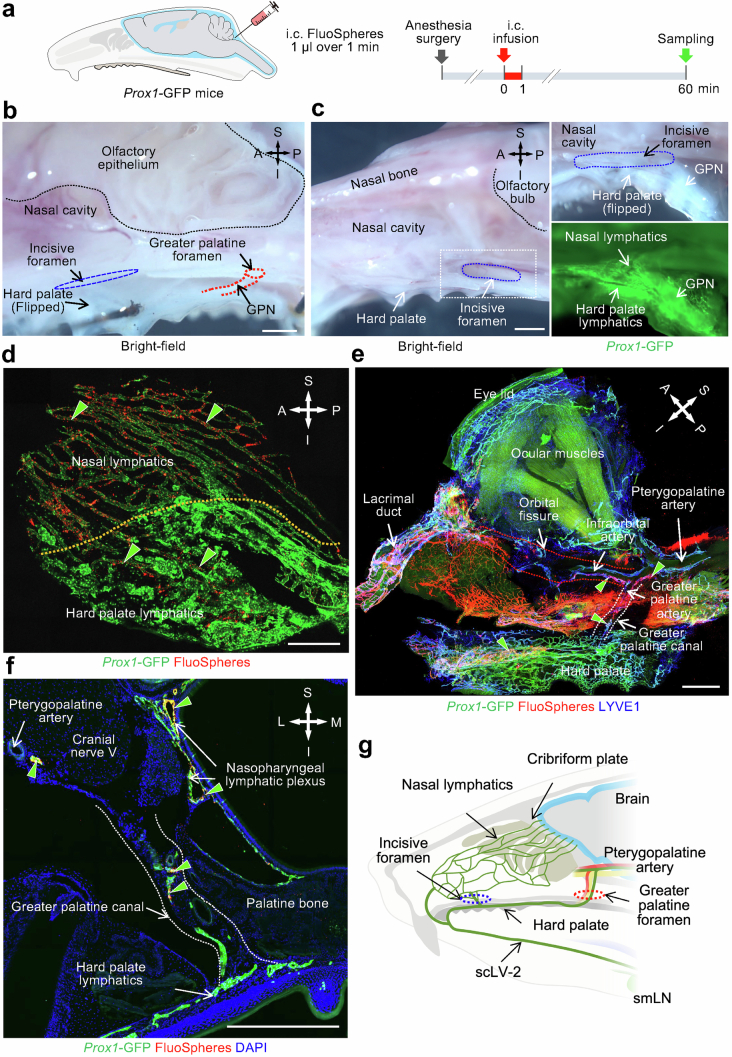

Extended Data Fig. 5. CSF drainage through two lymphatic routes to hard palate lymphatics en route to the submandibular lymph node.

a, Sequence of intracisternal (i.c.) infusion of 1.0 μl FluoSpheres over 1 min into Prox1-GFP mice followed by imaging of FluoSphere distribution in the nasal cavity and hard palate 60 min later. b, Brightfield microscopic image showing the anatomical location of the incisive foramen (blue dashed elliptical circle), greater palatine foramen (red dashed circle), and greater palatine nerve (GPN, red dashed lines). The black dashed line marks the border of the olfactory epithelium. Scale bar, 1 mm. Representative of n = 3 mice from three independent experiments. c, Brightfield, fluorescence, and immunofluorescence images of whole mounts showing connections between lymphatics in the nasal cavity and hard palate through the incisive foramen. Brightfield image showing the anatomical location of the incisive foramen (blue dashed elliptical circle). White dashed line box is enlarged in brightfield and fluorescence images in the right two panels that show connections between lymphatics in the nasal mucosa and hard palate through the incisive foramen. The black dashed line marks the border of the intracranial olfactory bulb. Scale bar, 1 mm. Representative of n = 4 mice from three independent experiments. d, Immunofluorescence image showing FluoSpheres (red) within lymphatics in the nasal mucosa and hard palate (green arrowheads). The orange dashed line marks the boundary between lymphatics in the nasal mucosa and hard palate. Scale bar, 200 μm. Representative of n = 4 mice from three independent experiments. e, Immunofluorescence image of whole mount showing FluoSpheres (red) and lymphatics (Prox1-GFP, green; LYVE1, blue) in the periorbital area and hard palate. FluoSphere fluorescence is strong in lymphatics along the pterygopalatine artery, infraorbital artery in the orbital fissure, greater palatine artery in the greater palatine canal, and hard palate (green arrowheads). Red dashed lines mark the lymphatic pathway from the orbital fissure to periorbital lymphatics. White dashed lines mark the lymphatic pathway from descending branch of pterygopalatine artery through the greater palatine canal to the hard palate plexus. Scale bar, 1 mm. Representative of n = 4 mice from three independent experiments. f, Immunofluorescence image of coronal section of the greater palatine canal showing FluoSpheres (red) in lymphatics (green) along the pterygopalatine artery, in the greater palatine canal, and in the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus (green arrowheads). The white dashed lines mark the lymphatic pathway from the greater palatine canal to the hard palate. Scale bar, 500 μm. Representative of n = 4 mice from three independent experiments. g, Drawing of two lymphatic routes for CSF to reach the hard palate lymphatic plexus, superficial cervical lymphatic scLV-2, and submandibular lymph node (smLN): (1) Meningeal lymphatics that cross the cribriform plate join nasal lymphatics and then traverse the incisive foramen to join the hard palate plexus. (2) Meningeal lymphatics along the pterygopalatine artery travel with the greater palatine artery through the greater palatine canal and join the hard palate lymphatic plexus. Lymphatics in the hard palate plexus carry CSF to scLV-2 en route to the submandibular lymph node. Anatomical positions are indicated in the top right corner: S, superior; I, inferior; A, anterior; P, posterior; M, medial; L, lateral.

Extended Data Fig. 7. CSF drainage through the hard palate lymphatic plexus to the submandibular lymph node.

a, Sequence of intracisternal (i.c.) infusion of 1.0 μl TMR-dextran or FluoSpheres over 1 min into Prox1-GFP mice followed by analysis of the distribution of the tracer in the hard palate lymphatic plexus at 60 min. b-d, Fluorescence images showing the distribution of TMR-dextran or FluoSpheres (red) in whole mounts of the hard palate and soft palate of Prox1-GFP mice (b,c). White dashed lines mark border between hard palate and soft palate (b). Tracer fluorescence (red) is strong in hard palate lymphatic plexus (red arrowheads) but not in soft palate lymphatic plexus (b,c white empty arrowheads). Orange arrowheads mark the faint TMR-dextran fluorescence in the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus (b). Hard palate lymphatic plexus of Prox1-GFP mouse stained for VEGFR3 (red) and LYVE1 (blue) (d). Lymphatic valves (d, white arrowheads). Initial lymphatics (d, blue arrowheads) are distributed in the medial and lateral sides of hard palate. Scale bars, 1 mm. Representative of n = 5 mice from three independent experiments. e,f, Images showing TMR-dextran fluorescence (red arrowheads) in the buccal (e) and mandibular (f) portions of superficial cervical lymphatic scLV-2 between the hard palate lymphatic plexus and submandibular lymph node. White dashed lines (e) outline border of hard palate, tongue, and buccal portion of scLV-2. Yellow arrows mark the direction of CSF outflow. Scale bars, 1 mm. Representative of n = 5 mice from three independent experiments. g, Drawing of downstream connection of hard palate plexus to submandibular lymph node (smLN) through buccal and mandibular portions of scLV-2 for CSF drainage. Locations of scLV-1 and scLV-3 are shown for comparison. Left (Lt.), Right (Rt.). Anatomical positions are indicated in the bottom left corner: A, anterior; P, posterior; M, medial; L, lateral.

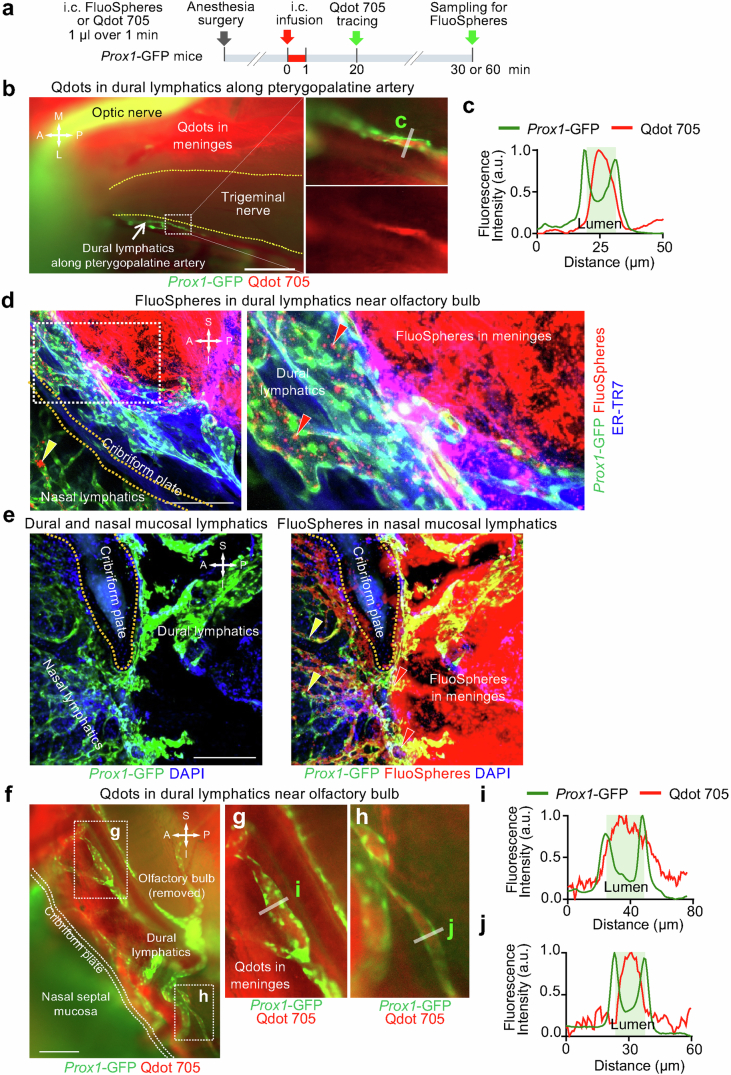

Extended Data Fig. 6. Dural lymphatics containing tracers after infusion into the CSF.

a, Sequence of intracisternal (i.c.) infusion of 1.0 μl FluoSpheres or Qdot 705 over 1 min into Prox1-GFP mice followed by imaging of the tracer distribution in dural lymphatics near pterygopalatine artery or cribriform plate 20, 30 or 60 min later. b,c, Fluorescence images of Qdot 705 in dural lymphatics along pterygopalatine artery (b). Trigeminal nerve is outlined by yellow dashed line. Region of dashed line box is enlarged in right two panels, upper showing Prox1-GFP and Qdot 705 and lower showing only Qdot 705. Fluorescence intensity profiles of Prox1-GFP and Qdot 705 in the dural lymphatic (gray bar in b) is shown in c. Scale bar, 500 μm. Representative of n = 3 mice from three independent experiments. d,e, Confocal microscopic images of whole mounts showing a sagittal view of lymphatics near the cribriform plate (yellow dashed line). Dashed line box in d-left is enlarged in d-right. Panel e shows a region near d without (e-left) and with (e-right) the red channel (FluoSpheres). After intracisternal infusion, FluoSpheres (red) are located in dural lymphatics (red arrowheads), nasal mucosal lymphatics (yellow arrowheads), and trapped in the meninges (probably arachnoid layer) bordering the SAS. Staining of meninges by anti-mouse fibroblast antibody ER-TR7 (blue). Scale bars, 200 μm. Representative of n = 6 mice from three independent experiments. f-j, Fluorescence images showing Qdot 705 in dural lymphatics near the cribriform plate (white dashed lines). Regions in f marked by dashed line boxes are enlarged in right two panels (g and h). Fluorescence intensity profiles of Prox1-GFP and Qdot 705 (i and j) in dural lymphatics (gray bars in g and h). Scale bar, 1 mm. Representative of n = 3 mice from three independent experiments. Anatomical positions are indicated in the top right or left corner: S, superior; I, inferior; A, anterior; P, posterior; M, medial; L, lateral.

Lymphatics of the hard palate plexus upstream to scLV-2 had short lymphangions, a mixture of typical semilunar valves and atypical irregularly shaped valves that stained for Prox1–GFP and laminin-α5, but they had no smooth muscle coverage (Supplementary Fig. 9). These features resemble lymphatics of the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus23 and differ both from initial lymphatics, which have oak leaf-shaped endothelial cells, and from collecting lymphatics, which have semilunar valves, longer lymphangions and smooth muscle coverage.

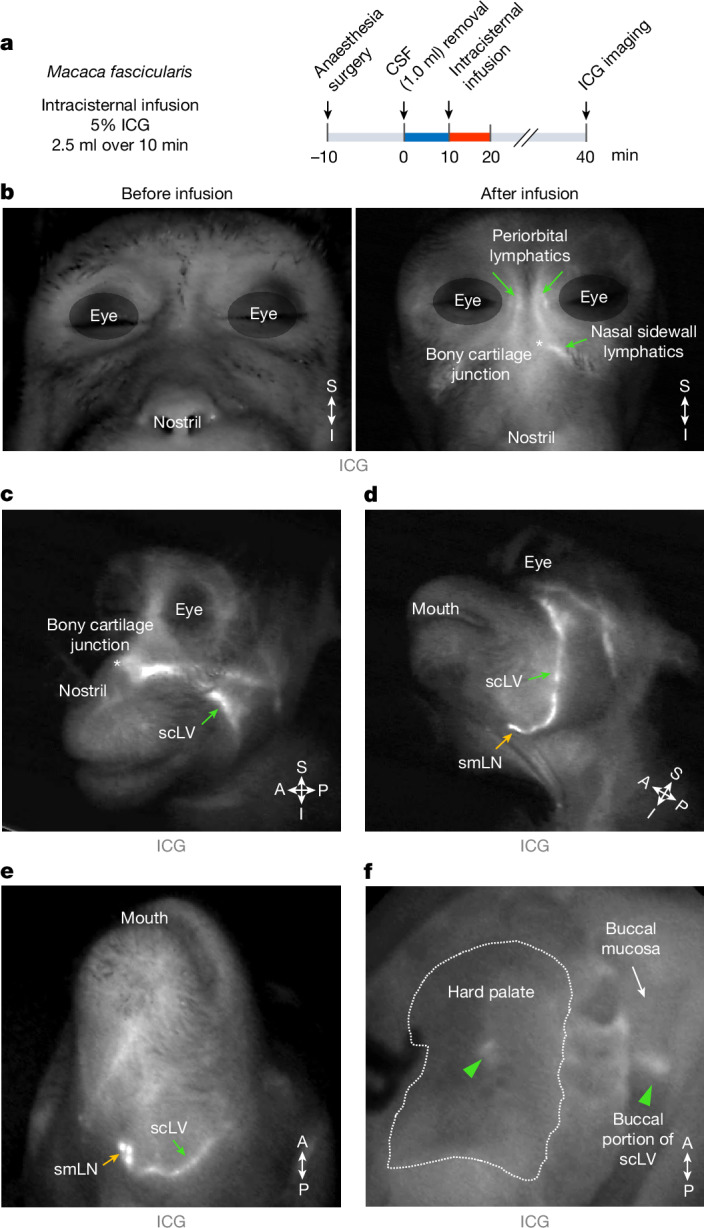

FluoSpheres infused into the SAS of monkeys revealed CSF drainage routes through lymphatics like those in mice (Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Similarly, indocyanine green infused into the SAS of monkeys revealed CSF drainage routes through lymphatics in the periorbital, nasal sidewall, hard palatal and superficial cervical regions of the face and neck (Fig. 4), similar to those shown by TMR–dextran or FluoSphere infusion in mice.

Fig. 4. CSF tracer in lymphatics around the eye and in the nasal sidewall, hard palate and superficial cervical regions of the monkey.

a, Sequence of intracisternal infusion of 2.5 ml indocyanine green (ICG) into M. fascicularis monkeys over 10 min followed at 30 min by imaging of ICG in the face and neck. Before infusion, 1.0 ml of CSF was removed at the cisterna magna over 10 min. b–e, Images of the face of monkeys before and after the intracisternal infusion showing ICG fluorescence (white) in lymphatics. The white asterisk (bone–cartilage junction) marks the lymphatic connection between the nasal mucosa and nasal sidewall. The green arrows indicate ICG in lymphatics in the periorbital and nasal sidewall regions and in scLVs. The yellow arrows indicate ICG in the smLN. Representatives of n = 3 monkeys from three independent experiments. f, Image showing ICG fluorescence (white) in hard palate and buccal lymphatics and scLVs (green arrowheads) of a monkey after intracisternal infusion. The white dashed line marks the boundary of the hard palate. Representatives of n = 3 monkeys from three independent experiments. Anatomical positions are indicated in the bottom right corner.

To determine whether the lymphatics upstream to the superficial cervical lymph node can be expanded, mouse Vegfc (mVegfc) was overexpressed in Prox1–GFP mice by intracisternal delivery of 1 × 1013 gene copies of adeno-associated virus serotype 9 encoding mVEGF-C–mCherry (AAV9–mVEGF-C–mCherry) or control AAV9–mCherry (Supplementary Fig. 10a). Four weeks after viral delivery, mCherry fluorescence reflecting mVEGF-C expression was present around lymphatics of the nasal cavity, hard palate and transverse sinus, but not around the scLVs (Supplementary Fig. 10b,c). In the AAV9–mVEGF-C–mCherry group, lymphatics were expanded in the nasal mucosa (1.30-fold), inferior nasal mucosa (1.56-fold), hard palate (1.42-fold) and along the transverse sinus of dorsal meninges (4.57-fold) over corresponding regions in the AAV9–mCherry control group, but no change was found in the scLVs (Supplementary Fig. 10). These findings indicate that lymphatics upstream to the superficial cervical lymph node can be expanded by activating VEGF-C–VEGFR3 signalling, but scLV trunks do not change under these conditions.

As the parotid lymph node did not receive drainage from the SAS, we determined the afferent drainage routes by infusing TMR–dextran into the facial dermis (0.5 μl over 1 min) of anaesthetized Prox1–GFP mice (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Fig. 11a,b). At 15 min after injection into each of three facial compartments, TMR–dextran fluorescence was found in the parotid lymph node, but not in the submandibular or accessory submandibular lymph node (Supplementary Fig. 11c–e). These findings provide evidence that the parotid lymph node receives lymph from facial skin and not from the SAS.

Ageing reduces CSF drainage via the scLV

CSF outflow through lymphatics decreases with age20,23,43,44. The reduction in CSF drainage to deep cervical lymph nodes has been documented in multiple studies of aged mice14,16,20,23,25. In the present study, we found that TMR–dextran fluorescence in the submandibular lymph node at 60 min after infusion into the SAS was approximately 30% less in aged mice (80–95 weeks) than in younger adults (8–12 weeks; Supplementary Fig. 12).

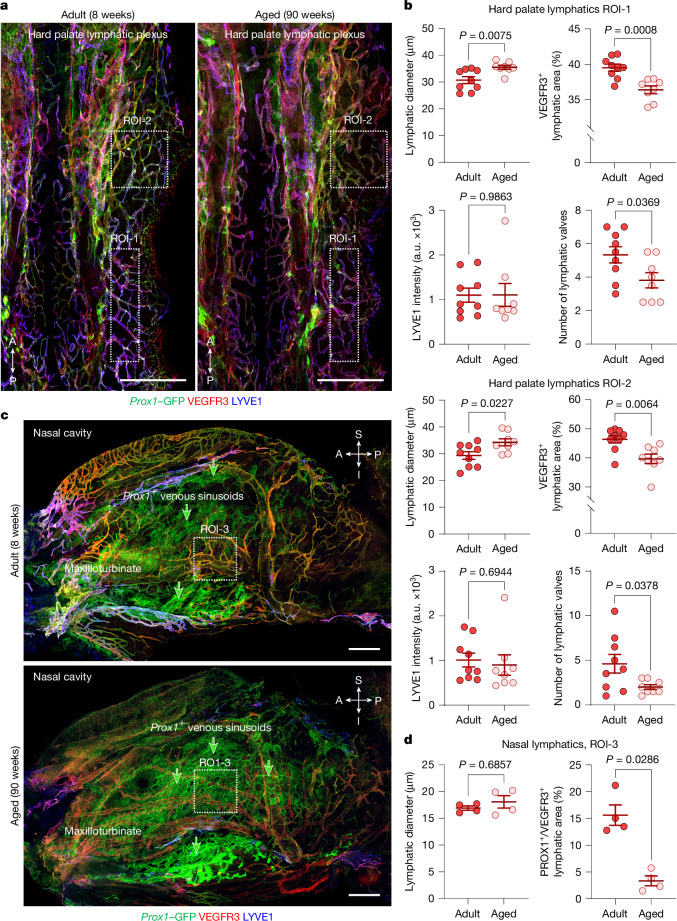

To learn the reason for the reduction in aged mice, we compared the abundance and size of lymphatics in the scLV pathway of aged mice to younger adults. The extent (area) of the VEGFR3+ lymphatic network upstream to scLV-2 of aged mice was approximately 80% less in the nasal mucosa and 9–17% less in the hard palate plexus than in younger adults (Fig. 5). Lymphatics in the nasal mucosa were about the same size in the two age groups, but in the hard palate plexus were 11–12% larger in aged mice (Fig. 5). Lymphatic valves in the hard palate plexus were 43–71% less numerous in aged mice (Fig. 5a,b). LYVE1 staining intensity of the hard palate lymphatic plexus was similar in the two age groups (Fig. 5a,b), which could reflect resistance of LYVE1+ lymphatics to regression during ageing.

Fig. 5. Ageing-related changes in lymphatics of the nasal mucosa and hard palate.

a, Immunofluorescence images of whole mounts comparing hard palate lymphatics in adult (8 weeks of age) and aged (90 weeks of age) Prox1–GFP mice. Like lymphatics, venous sinusoids are PROX1+. Ageing-related reductions in the lymphatic plexus are outlined by white dashed line boxes that mark regions of interest (ROIs) near the greater palatine nerve (ROI-1) and incisive foramen (ROI-2). Scale bars, 500 μm. Representative of n = 9 mice (adult) and n = 8 mice (aged) from three independent experiments. b, Comparison of lymphatic diameter, VEGFR3+ lymphatic area, LYVE1 intensity and number of lymphatic valves in ROI-1 and ROI-2 in adult (8–10 weeks of age; n = 9) and aged (86–95 weeks of age; n = 8) Prox1–GFP mice. Each dot is the value for one mouse. The error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated by two-tailed Welch’s t-test. c, Immunofluorescence images of whole mounts comparing nasal lymphatics in adult (8 weeks of age) and aged (90 weeks of age) Prox1–GFP mice. Staining as in panel a. ROI-3 marks the measured region of PROX1+/VEGFR3+ nasal lymphatics (red) for data in panel d. Unlike PROX1+/VEGFR3+ nasal lymphatics, which are abundant in young adults but less in aged mice, PROX1+ venous sinusoids (green; marked by green arrows) are more abundant in aged mice, as previously described50. Scale bars, 500 μm. Representative of n = 4 mice (adult) and n = 4 mice (aged) from three independent experiments. d, Comparison of lymphatic diameter and PROX1+/VEGFR3+ lymphatic area in nasal lymphatics of adult (8–10 weeks of age; n = 4) and aged (86–95 weeks of age; n = 4) Prox1–GFP mice. Each dot is the value for one mouse. The error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-tests. Anatomical positions are indicated in the bottom left or top right corner.

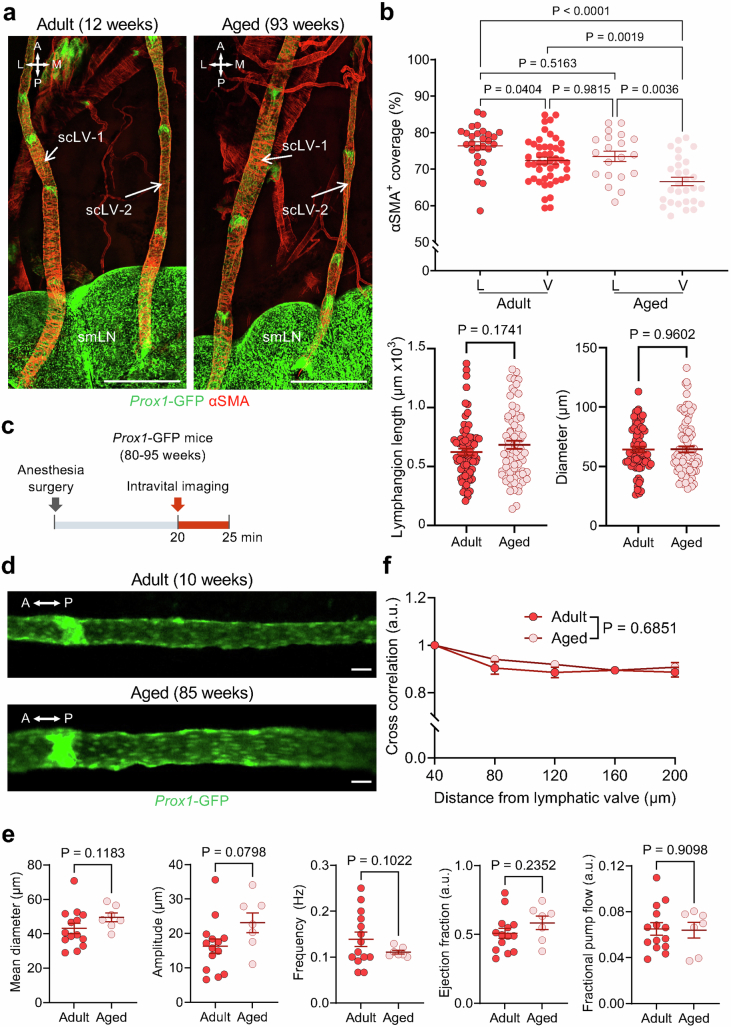

These differences in upstream lymphatics examined ex vivo were not accompanied by corresponding changes in scLV-1 or scLV-2, where the diameter, lymphangion length and αSMA+ smooth muscle coverage of the mid-lymphangion region were similar in aged and younger adult mice. However, a small reduction (5.7%) was found in αSMA+ smooth muscle coverage of the perivalvular region of scLV-1 and scLV-2 in aged mice (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b).

Extended Data Fig. 8. Ageing-related changes in smooth muscle coverage and functional properties of superficial cervical lymphatics in vivo.

a, Immunofluorescence images showing smooth muscle coverage in superficial cervical lymphatics (scLV) of aged Prox1-GFP mice (93 weeks) and in younger adults (12 weeks). α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), Submandibular lymph node (smLN). Scale bars, 500 μm. Representative of n = 12-13 mice from three independent experiments. b, Measurements showing less circular smooth muscle coverage (α-smooth muscle actin, αSMA) in the peri-valvular region (V) of superficial cervical lymphatics in aged Prox1-GFP mice (80–95 weeks) than in younger adults (10–12 weeks) but no difference in coverage of the middle of lymphangions (L) (upper). Similarities of lymphangion length and diameter at the two ages are also shown (lower). Each dot is the value for one lymphangion. n = 13 (adult), n = 12 (aged) mice per group from four independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values calculated by two-tailed unpaired t test with Welch’s correction or Brown-Forsythe ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison test. c, Sequence of surgical exposure and intravital imaging of superficial cervical lymphatics scLV-1 from adult (10–12 weeks) and aged (80–95 weeks) Prox1-GFP mice. Intravital imaging began after a 20-min stabilization period and lasted 5 min. d, Intravital images of superficial cervical lymphatic scLV-1 of adult (10 weeks) and aged (85 weeks) Prox1-GFP mice. Scale bars, 20 μm. Representative of n = 7-14 mice from four independent experiments. e, Measurements showing no age-related difference in mean diameter, contraction amplitude, frequency of spontaneous contraction, ejection fraction, or fractional pump flow of scLV-1 from aged Prox1-GFP mice (80–95 weeks) and younger adults (10–12 weeks). Each dot is the value for one mouse. n = 14 (adult), n = 7 (aged) mice of both sexes per group from four independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. a.u., arbitrary unit. P values calculated by two-tailed unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. f, Measurements of synchronization of spontaneous contractions and relaxations within a lymphangion assessed by cross-correlation of changes in diameter at five locations in superficial cervical lymphatics scLV-1 spaced 40 μm to 200 μm away from a valve in aged (80–95 weeks) and younger adult (10–12 weeks) Prox1-GFP mice. Each dot is the value for one mouse and n = 8 (adult), n = 7 (aged) mice for both sexes from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values calculated by two-way ANOVA test. The P value represents the significance of the interaction between cross-correlation and the measurement location. Anatomical positions are indicated in the top left corner: A, anterior; P, posterior; M, medial; L, lateral.

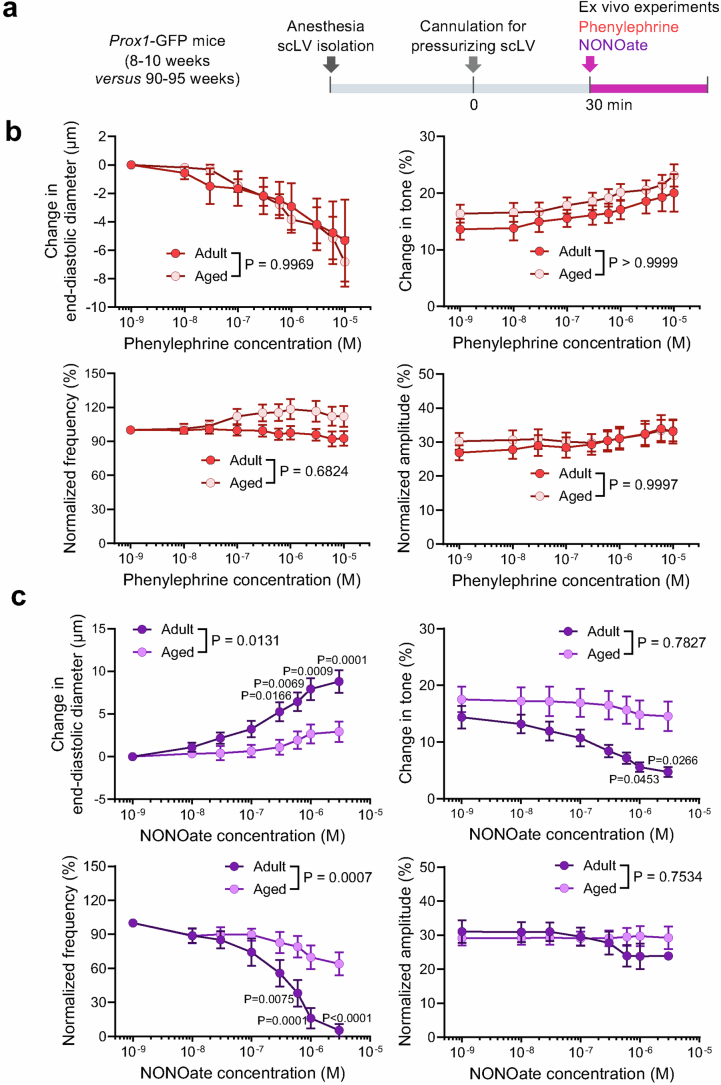

Spontaneous contractions and relaxations of scLV-1 were similar in aged and younger adult mice. Intravital imaging of scLV-1 revealed no differences in diameter, contraction amplitude, frequency of spontaneous contraction, ejection fraction or fractional pump flow between aged and younger adults (Extended Data Fig. 8c–e). In addition, spontaneous contractions and relaxations within individual lymphangions of scLV-1 were comparably synchronized, as reflected by cross-correlations of synchronizing indices (Extended Data Fig. 8f). Similarly, scLV-1 examined ex vivo after removal from aged and younger adults had equivalent responses to pressures between 0.5 and 10 cmH2O and to the α1-adrenergic agonist phenylephrine in a range of 10−9 to 10−5 M (Extended Data Fig. 9a,b and Supplementary Fig. 13a,b).

Extended Data Fig. 9. Ageing-related reduction in response of isolated superficial cervical lymphatics to NONOate but not to phenylephrine.

a, Sequence of experiments of superficial cervical lymphatics scLV-1 or scLV-2 removed from Prox1-GFP mice at age 8–10 weeks (adult) and 90–95 weeks (aged), cannulated, pressurized, and then exposed ex vivo to phenylephrine or NONOate. b, Comparison of response to phenylephrine measured by changes in end-diastolic diameter, tone, normalized frequency, and amplitude of scLV-1 and scLV-2 after removal from adult (8–10 weeks, n = 9) and aged (90–95 weeks, n = 14) Prox1-GFP mice. No significant age-related differences were found. Each dot is the value for one mouse of either sex from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values calculated by two-way ANOVA test followed by two-tailed Sidak’s multiple comparison test. The P values represent the significance of the interaction between phenylephrine concentration and scLV from adult or aged mice. c, Comparison of response to NONOate reflected by changes in end-diastolic diameter, tone, normalized frequency, and amplitude of scLV-1 and scLV-2 from adult (8–10 weeks, n = 9) and aged (90–95 weeks, n = 14) Prox1-GFP mice. Ageing-related differences in concentration-dependent NONOate-induced end-diastolic diameter and normalized frequency were significant. Each dot is the value for one mouse of either sex from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values calculated by two-way ANOVA test followed by two-tailed Sidak’s multiple comparison test. The P values represent the significance of the interaction between NONOate concentration and scLV from adult or aged mice.

Despite the similarities, the changes of end-diastolic diameter and normalized frequency to nitric oxide donor NONOate (10−7 to 3 × 10−6 M) of scLV-1 were smaller in aged mice (Extended Data Fig. 9c), which was evidence of dysfunctional nitric oxide synthesis and signalling in cervical lymphatics in aged mice. Despite the apparent nitric oxide insensitivity, no differences were found in spontaneous contraction parameters of scLV-1 in aged mice compared with younger adults (Extended Data Fig. 8c–e), implying that the CSF pumping function of cervical lymphatics is maintained during ageing.

Together, these findings revealed a mixture of ageing-related changes in lymphatic networks that drain through scLV-1 and scLV-2 to submandibular lymph nodes. Most conspicuous was the reduction in nasal mucosal lymphatics. Although scLV-1 and scLV-2 manifested few ageing-related structural changes, responses of these vessels to nitric oxide were impaired in aged mice.

Transcriptomic changes in the scLV with ageing

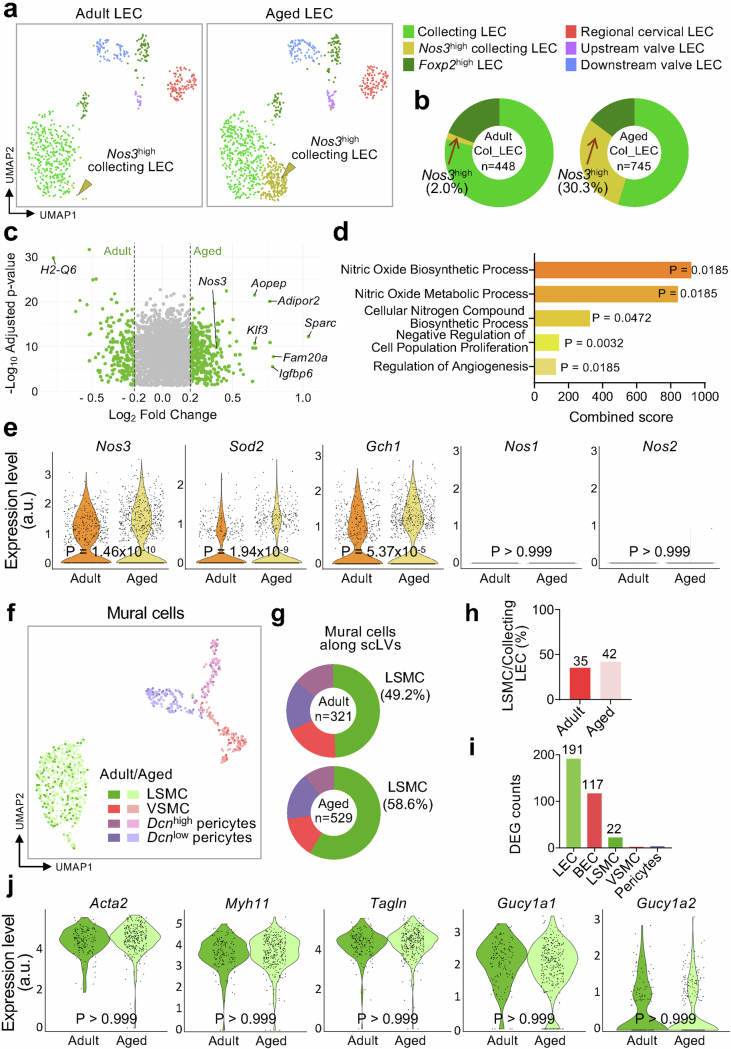

To gain further insight into the nature of ageing-related changes in endothelial cells of scLV-1 and scLV-2, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis of pooled samples of cells isolated from cervical subcutaneous tissues that contained lymphatics proximal to and around the submandibular lymph nodes from six adult mice (three males and three females) and six aged mice (three males and three females; see Methods for details).

Unsupervised clustering analysis of 21,170 cells from the 12 mice revealed four distinct clusters of lymphatic vessel endothelial cells (LECs; 1,604 cells), blood vessel endothelial cells (640 cells), vascular mural cells (850 cells) and fibroblasts (18,076 cells; Supplementary Fig. 14a). These clusters were further divided into six subclusters of LECs, four subclusters of mural cells and five subclusters of fibroblasts, each distinguished by differential gene expression and annotated by subtype marker genes23,45–51 (Supplementary Fig. 14b–e).

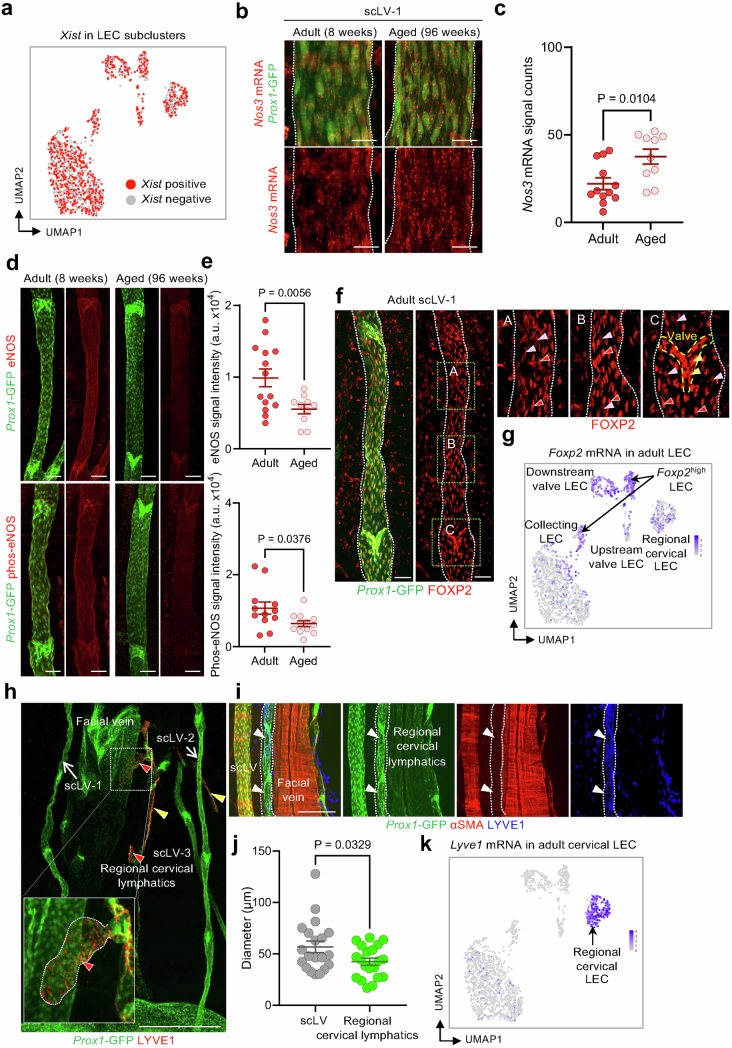

The identity of the six subclusters of LECs was characterized and validated by gene expression profiles, in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence staining. All LEC clusters had high expression of Pecam1, a pan-endothelial cell marker, and Prox1, a pan-LEC marker (Supplementary Fig. 14e). LEC subcluster gene expression profiles were annotated as collecting LEC (Apoe+Eng+Bgn+), Nos3high collecting LEC (Nos3+Sparc+Igfbp+), Foxp2high LEC (Foxp2+Apoe+)47,49, initial and pre-collecting (regional) cervical lymphatic LEC (Lyve1+Reln+Piezo2+), upstream valve LEC (Cldn11+Neo1+) and downstream valve LEC (Cldn11+Adm+)23,46,48,50 (Extended Data Fig. 10a and Supplementary Fig. 14b,e). Heatmaps revealed distinctive differences in the gene expression profiles of the six LEC clusters (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Extended Data Fig. 10. Ageing-related transcriptomic changes in superficial cervical lymphatics.

a, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot of single-cell gene expression (scRNA-seq) showing six subclusters of lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC) isolated from superficial cervical lymphatics scLV-1 and scLV2 proximal to and around submandibular lymph nodes of adult (12 weeks) and aged (93 weeks) mice. Gold arrowheads mark the Nos3high collecting LEC subcluster that is greatly increased in aged mice. b, Pie charts showing the 15-fold enlargement of the Nos3high LEC subcluster in collecting LEC from aged mice (745 cells) compared collecting LEC from adult mice (448 cells). The other LEC subclusters do not show this change. Values based on scRNA-seq gene expression analysis of scLV-1 and scLV2 in a. c, Volcano plot showing 2,624 differentially expressed genes between adult and aged LECs. Positive values of Log2 fold change indicate genes upregulated in aged LECs, while negative values indicate genes with higher expression in adult LECs. Gray dots indicate genes with Log2 fold change absolute values less than 0.2, while green dots indicate genes with absolute values greater than 0.2. P values calculated by two-tailed MAST with Bonferroni post hoc test. d, Bar graphs showing five terms from Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of Nos3high collecting LEC indicating the largest enrichment of nitric oxide-related gene functions. GO enrichment was assessed using Enrichr. P values calculated using one-tailed Fisher’s exact test, with FDR correction using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Complete dataset for the GO term analysis is presented in Supplementary Table 2. e, Violin plots showing greater expression of Nos3, Sod2, and Gch1 genes in LEC of aged mice but no detected expression of Nos1 and Nos2 genes in LEC of either younger adults or aged mice. P values calculated by two-tailed MAST with Bonferroni post hoc test. f-i, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot of gene expression in mural cells from superficial cervical lymphatics showing four subclusters that are similar in younger adult (12 weeks, n = 321 cells analyzed) and aged (93 weeks, n = 529 cells analyzed) mice (f). Pie charts showing similar proportions of lymphatic smooth muscle cells (LSMC), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), Dcnhigh pericytes, and Dcnlow pericytes in younger adults and aged mice (g). Bar graph comparing the percentage of LSMC relative to the number of collecting lymphatic endothelial cells (Apoe+Eng+Bgn+) from younger adult and aged mice (h). Number of differentially expressed genes between aged mice and younger adults in lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC), blood endothelial cells (BEC), LSMC, VSMC, and pericytes (i). j, Violin plots showing the absence of ageing-related gene expression differences in lymphatic smooth muscle cells of three smooth muscle markers (Acta2, Myh11, Tagln) and two downstream guanylate cyclases (Gucy1a1, Gucy1a2) of the nitric oxide pathway. P values calculated by two-tailed MAST with Bonferroni post hoc test.

The proportion of cells in the Nos3high collecting LEC subcluster in aged mice (30.3% of 968 LECs) was 15-fold the value in younger adults (2.0% of 635 LECs; Extended Data Fig. 10b). The 10 genes in the Nos3high cluster from aged mice with the greatest expression (3.4–6.6-fold) compared with the other LEC clusters were Dcpp1, Cyp1b1, Gm14636, Adipor2, Fam20a, Tead4, Fam135a, Sparc, Igfbp6 and Klf3 (Supplementary Fig. 15). Previous reports52–55 have shown that four of these genes (Adipor2, Tead4, Sparc and Igfbp6) are associated with ageing in multiple cell types. In the Nos3high collecting LEC cluster, Adipor2, Sparc and Igfbp6 were found by volcano plot analysis to be upregulated 1.6–2.0-fold in aged mice (Extended Data Fig. 10c).

Analysis by Gene Ontology revealed that expression of multiple genes related to nitric oxide biosynthetic and metabolic processes was greater in the Nos3high collecting LEC subcluster of aged mice (Extended Data Fig. 10d). In addition to Nos3, aged mice had greater expression of Sod2, encoding superoxide dismutase 2, which reduces the burden of reactive oxygen species created when eNOS is uncoupled and produces superoxide instead of nitric oxide56 (Extended Data Fig. 10e). Also having greater expression in the LECs of aged mice was Gch1, which encodes GTP cyclohydrolase, a rate-limiting enzyme in the production of a key NOS cofactor (tetrahydrobiopterin; Extended Data Fig. 10e). Unlike Nos3, expression of Nos1, encoding neuronal NOS, and Nos2, encoding inducible NOS, was not detected in the LECs of younger or aged mice (Extended Data Fig. 10e).

Greater Nos3 expression in superficial cervical LECs was confirmed by RNA in situ hybridization for Nos3 mRNA (Extended Data Fig. 11a–c). However, immunofluorescence staining revealed lower staining for eNOS protein and phosphorylated (Ser1177)-eNOS in these LECs of aged mice than in younger adults (Extended Data Fig. 11d,e). This discrepancy could be explained by dysregulated translational activity, protein stability or functional activity of eNOS in the LECs of aged mice57,58.

Extended Data Fig. 11. Validation of scRNA-seq data with RNA in-situ hybridization and immunohistochemical staining of LEC clusters.

a, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot showing expression of Xist, a female-specific non-coding RNA, in LEC clusters from 3 male and 3 female Prox1-GFP mice shown in Extended Data Fig. 10a. Equal distributions of Xist positive and Xist negative cells are consistent with the sample being representative. b,c, Representative RNA in-situ hybridization images and signal counts comparing Nos3 mRNA expression in superficial cervical lymphatics scLV-1 (white dashed lines) in whole mounts from adult (8 weeks) and aged (96 weeks) Prox1-GFP mice. Scale bars, 20 μm. In c, each dot is the value for one side of scLV-1 from one mouse. n = 6 mice (adult) and n = 5 mice (aged) from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values calculated by two-tailed Welch’s t-test. d,e, Confocal microscopic images and measurements of immunofluorescence staining for eNOS and phosphorylated-eNOS (phos-eNOS) in superficial cervical lymphatics scLV-1 in tissue whole mounts from adult (8 weeks) and aged (96 weeks) Prox1-GFP mice. Scale bars, 100 µm. Each dot is the value for one side of scLV-1 from one mouse. n = 7 (adult, eNOS), n = 6 (adult, Phos-eNOS) mice and n = 5 (aged, eNOS), n = 6 (aged, Phos-eNOS) mice from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values calculated by two-tailed Welch’s t-test. f,g, Confocal microscopic images of immunofluorescence staining (f) and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot (g) of FOXP2 expression in superficial cervical lymphatics scLV-1 (white dashed lines) in tissue whole mounts from adult (8 weeks) Prox1-GFP mice. Green dashed line boxes in f mark regions enlarged in the right three panels. Diverse features of FOXP2 expression in LEC are marked by colored arrowheads: red (Foxp2high LEC), pink (Foxp2low LEC), and yellow (Foxp2high LEC in valve). Scale bars, 50 μm. Representative of n = 3 mice from three independent experiments. FOXP2 immunofluorescence was variably strong in luminal LEC but consistently strong in valve LEC (f), which fits with the UMAP plot that shows two separate Foxp2high LEC clusters (g). h-k, Immunofluorescence images of whole mounts showing staining for Prox1-GFP and LYVE1 in initial lymphatics (with blunt ends, red arrowheads) and pre-collecting lymphatics (with valves, yellow arrowheads) of regional cervical lymphatics (h). White dashed line box marks the region enlarged in the left lower corner. Scale bar, 500 μm. Representative of n = 3 mice from three independent experiments. Immunofluorescence images of whole mounts showing Prox1-GFP in all lymphatics but not in a facial vein; αSMA staining of smooth muscle in a collecting lymphatic and facial vein but not in a pre-collecting lymphatic; and LYVE1 staining in a pre-collecting lymphatic (white arrowheads and dashed line outline) but not in the other vessels (i). Scale bar, 200 μm. Representative of n = 3 mice from three independent experiments. Dot plot graph showing superficial cervical collecting lymphatics that are larger in diameter than pre-collecting lymphatics in adult Prox1-GFP mice (j). Each dot is the value for one lymphangion from one side of cervical lymphatics. n = 6 mice from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. a.u., arbitrary unit. P values calculated by two-tailed Welch’s t-test. The immunofluorescence staining (h,i) fits with the strong Lyve1 mRNA expression restricted to the regional cervical (initial and pre-collecting) LEC cluster in the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot (k).

Further validation studies revealed variable but clear FOXP2 immunoreactivity in the LECs of scLVs and uniformly strong in LECs of valves (Extended Data Fig. 11f,g). The combination of Prox1–GFP and LYVE1-marked regional lymphatics, consisting of initial lymphatics (with blunt ends) and pre-collecting lymphatics (with valves; Extended Data Fig. 11h–k). By comparison, αSMA+ marked collecting lymphatics, which had smooth muscle cell envelopment but lacked LYVE1 (Extended Data Fig. 11i). Large veins were marked by αSMA+ but not Prox1–GFP (Extended Data Fig. 11i).

Mural cell subclusters were annotated according to previous work45,51 as lymphatic smooth muscle cells (Acta2+Myh11+Nr4a2highScn3ahigh)51, blood vessel smooth muscle cells (Acta2+Myh11+Nr4a2lowScn3alow)51, Dcnhigh pericytes (Vtn+Dcnhigh)45 and Dcnlow pericytes (Vtn+Dcnlow; Extended Data Fig. 10f and Supplementary Figs. 14c,e and 16). Pdgfrb, a pan-mural cell marker, was expressed in all mural cell clusters (Supplementary Fig. 14e).

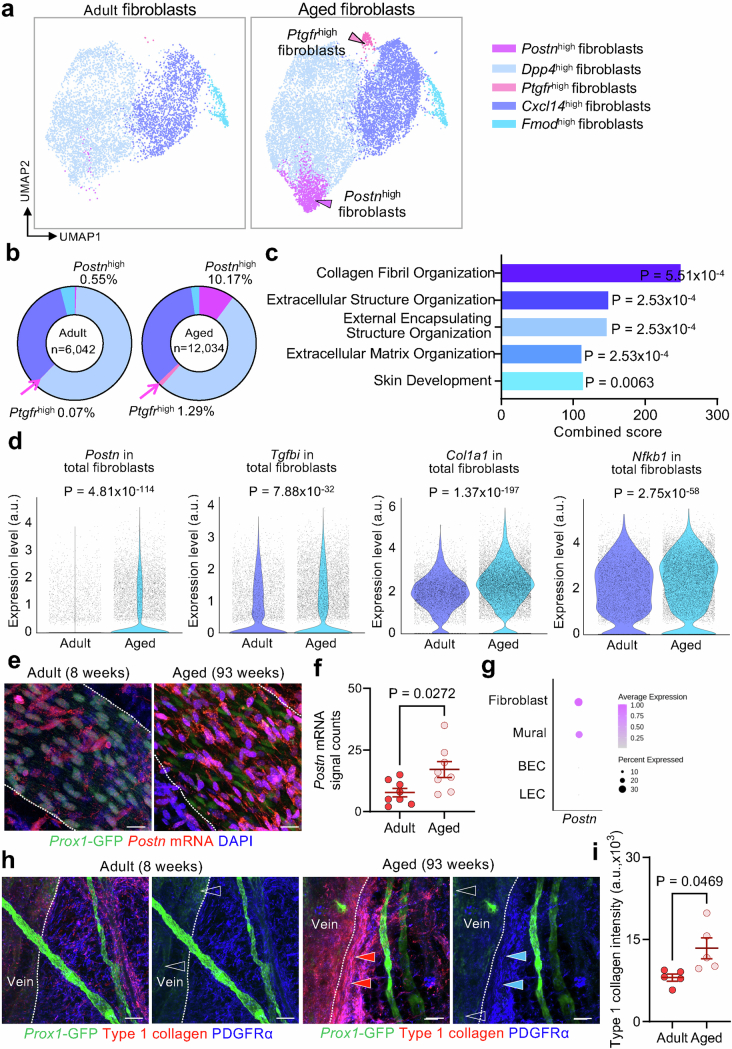

Fibroblast subclusters were annotated as Dpp4high fibroblasts (Dpp4+), Postnhigh fibroblasts (Postn+; encoding periostin), Cxcl14high fibroblasts (Cxcl14+Cxcl12+), Ptgfrhigh fibroblasts (Ptgfr+) and Fmodhigh fibroblasts (Fmod+)59,60 (Extended Data Fig. 12 and Supplementary Figs. 14d,e and 17). The pan-fibroblast markers Pdgfra and Col1a2 were highly expressed in all fibroblast subclusters (Supplementary Fig. 14e).

Extended Data Fig. 12. Differential effects of ageing on gene expression in five fibroblast subclusters associated with superficial cervical lymphatics.

a, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plots of single-cell gene expression (scRNA-seq) analysis identified five subclusters of fibroblasts in tissues around superficial cervical lymphatics from six adult (12 weeks) and six aged (93 weeks) Prox1-GFP mice. Arrowheads in plot of fibroblasts from aged mice mark subclusters that were rare in younger adult mice: magenta arrowhead marks the Postnhigh fibroblast subcluster, and pink arrowhead marks the Ptgfrhigh fibroblast subcluster. The total number of fibroblasts analyzed is 6,042 in adult mice and 12,034 in aged mice. b, Pie charts of the five fibroblast subclusters showing that Postnhigh (magenta) and Ptgfrhigh (pink) fibroblasts around superficial cervical lymphatics of aged mice were both 18 times the corresponding proportion in younger adults, but the other three fibroblast subclusters were similarly abundant at both ages. c, Gene ontology analysis of gene expression of fibroblasts around superior cervical lymphatics showing five gene ontology terms related to fibrosis that were significantly enriched in aged mice: collagen fibril organization, extracellular structure organization, external encapsulating structure organization, extracellular matrix organization, skin development. GO enrichment was assessed using Enrichr. P values calculated using one-tailed Fisher’s exact test, with FDR correction using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Complete dataset for the GO term analysis is presented in Supplementary Table 3. d, Violin plots showing four examples of fibrosis- or inflammation-related genes in fibroblasts around superficial cervical lymphatics that had significantly greater expression in aged mice than in younger adults: Postn (periostin, osteoblast-specific factor 2), Tgfbi (transforming growth factor, beta-induced), Col1a1 (skin, tendon, bone collagen, type I, alpha-1 chain), and Nfkb1 (nuclear factor kappa-B, subunit 1). P values calculated by two-tailed MAST with Bonferroni post hoc test. e-g, Images comparing RNA in-situ hybridization of Postn mRNA expression in whole mounts of superficial cervical lymphatics (white dashed lines) in Prox1-GFP mice at age 8 weeks and 93 weeks and corresponding measurements (e,f). In the younger adult specimen, Prox1-GFP nuclei (green) are prominent, but in the aged adult specimen, fibroblasts with strong expression of postn mRNA (magenta) and DAPI-stained (blue) nuclei are distributed around the superficial cervical lymphatics (e). Scale bars, 20 μm. The dot plot (g) shows the relative expression levels of postn mRNA in fibroblasts, mural cells, and endothelial cells of blood vessels (BEC) and lymphatics (LEC), based on scRNA-seq data in Supplementary Fig. 14. Each dot (f) is the value for one scLV from n = 4 mice (younger adult) and n = 4 mice (aged) examined in three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values calculated by two-tailed Welch’s t-test. h,i, Type 1 collagen immunofluorescence around the superficial cervical lymphatics and adjacent vein in whole mounts from adult (8 weeks) and aged (93 weeks) Prox1-GFP mice and corresponding measurements. Type 1 collagen staining (red arrowheads) is strongest in fibroblasts near the vein in the aged mouse but is less near the lymphatics and elsewhere (h). Veins (left of white dashed lines) are distinguished by the weak signal (blank arrowheads) of Prox1-GFP fluorescence. PDGFRα+ fibroblasts (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm. Measurements document greater type 1 collagen staining in the aged mice (i). Each dot is the value for one scLV. n = 5 mice (adult) and n = 5 mice (aged) from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values calculated by two-tailed Welch’s t-test.

Transcriptomes of lymphatic mural cell subclusters had few differences (Extended Data Fig. 10f), unlike the ageing-related changes in LECs. Both aged mice and younger adults had similar proportions and number of smooth muscle cells per LEC in collecting lymphatics, consistent with little or no change in these cells with ageing (Extended Data Fig. 10f–h). In addition, lymphatic smooth muscle cells, blood vessel smooth muscle cells and pericytes of aged mice had few differentially expressed genes than younger adults (Extended Data Fig. 10i). Mural cells in aged and younger adult mice had similar expression of canonical smooth muscle cell genes Acta2, Myh11 and Tagln and nitric oxide-mediated activating enzymes Gucy1a1 (encoding guanylate cyclase 1 soluble, α1) and Gucy1a2 (encoding guanylate cyclase 1 soluble, α2; Extended Data Fig. 10j).

In comparison, two of the five fibroblast subclusters were 18 times as numerous in aged mice as in younger adults: Postnhigh cells represented 10.17% compared with 0.55%, and Ptgfrhigh cells represented 1.29% compared with 0.07% of total cells (Extended Data Fig. 12a,b). Similarly, Gene Ontology analysis revealed greater expression of fibrosis-related genes in the fibroblast clusters of aged mice (Extended Data Fig. 12c). As examples, Postn, Tgfbi, Col1a1 and Nfkb1 had greater expression in the fibroblasts of aged mice (Extended Data Fig. 12d). Cells with Postn mRNA localized by RNA in situ hybridization were more abundant around scLVs of aged mice than of younger adults (Extended Data Fig. 12e–g). However, Col1a1 expression, assessed by immunofluorescence staining for type 1 collagen, was greater around larger veins than around lymphatics (Extended Data Fig. 12h,i).

Together, these findings provide evidence for increased expression of Nos3 and related genes in scLV LECs of aged mice; however, immunoreactivity for eNOS protein was reduced, indicating that nitric oxide signalling in these lymphatics could be impaired in ageing. Corresponding changes were not found in genes directly linked to contraction of lymphatic smooth muscle cells. Although periostin expression was greater in fibroblasts around lymphatics of aged mice, the increase in type I collagen was not restricted to lymphatics.

Mechanical manipulation increases CSF outflow

We next determined whether CSF drainage could be increased by manipulating scLV-1 and scLV-2 through the intact skin, with the goal of reversing the CSF drainage impairment in aged mice. These vessels were chosen because of their accessibility due to their superficial location in the head and neck, unlike dcLV23. Another feature of scLV-1 and scLV-2 was the innervation of their smooth muscle cell envelopment by adrenergic sympathetic axons, which were identified by staining for tyrosine hydroxylase, but not by cholinergic parasympathetic axons stained for vesicular acetylcholine transporter (Supplementary Fig. 18).

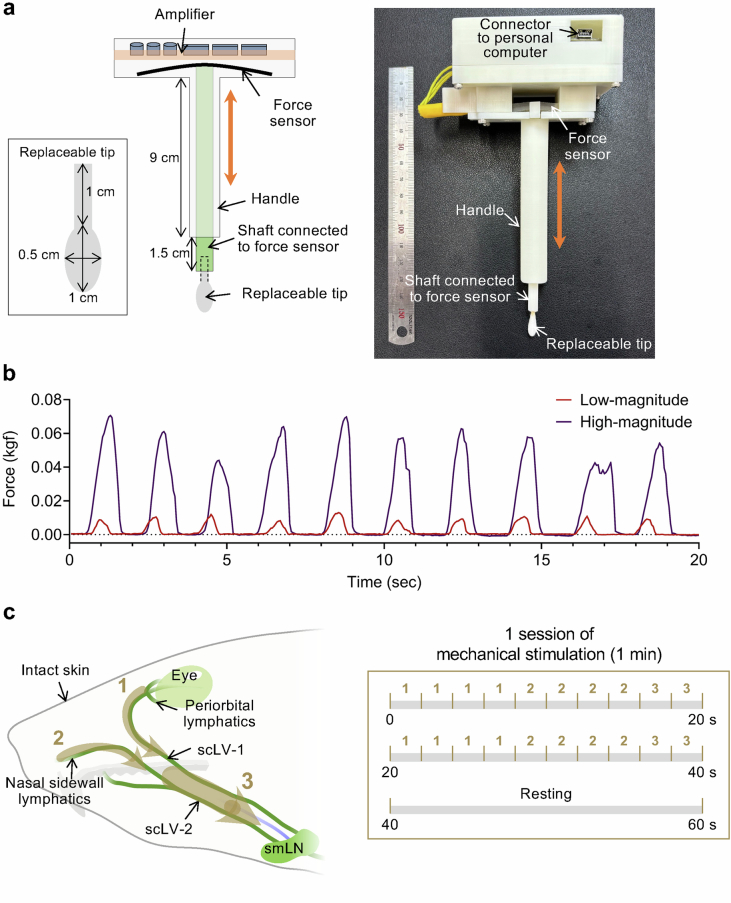

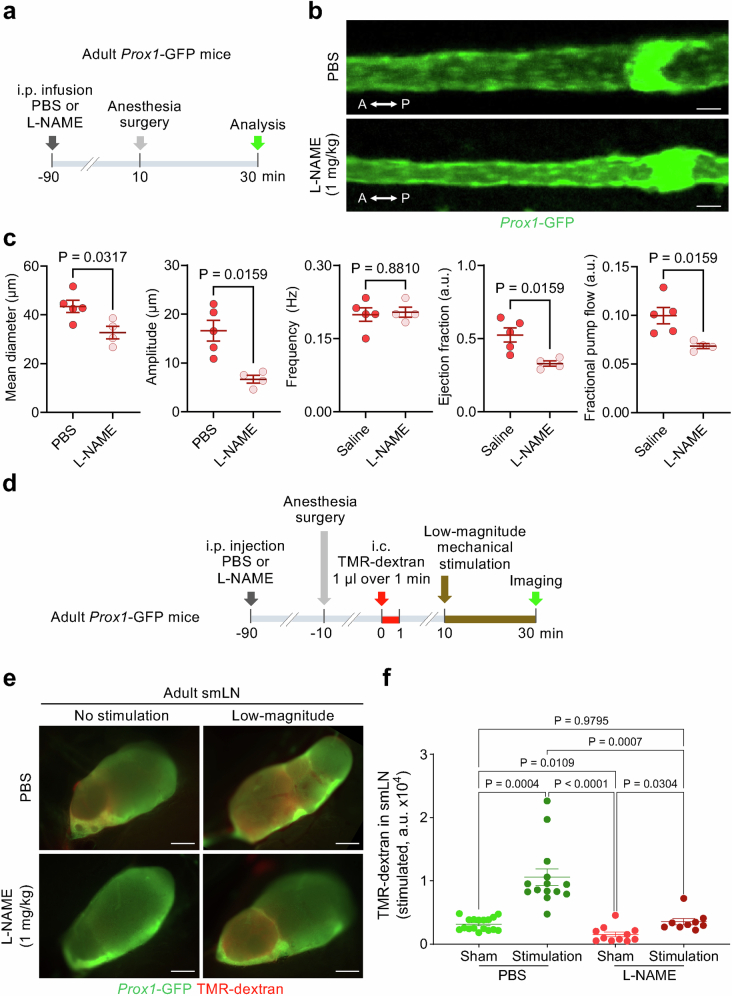

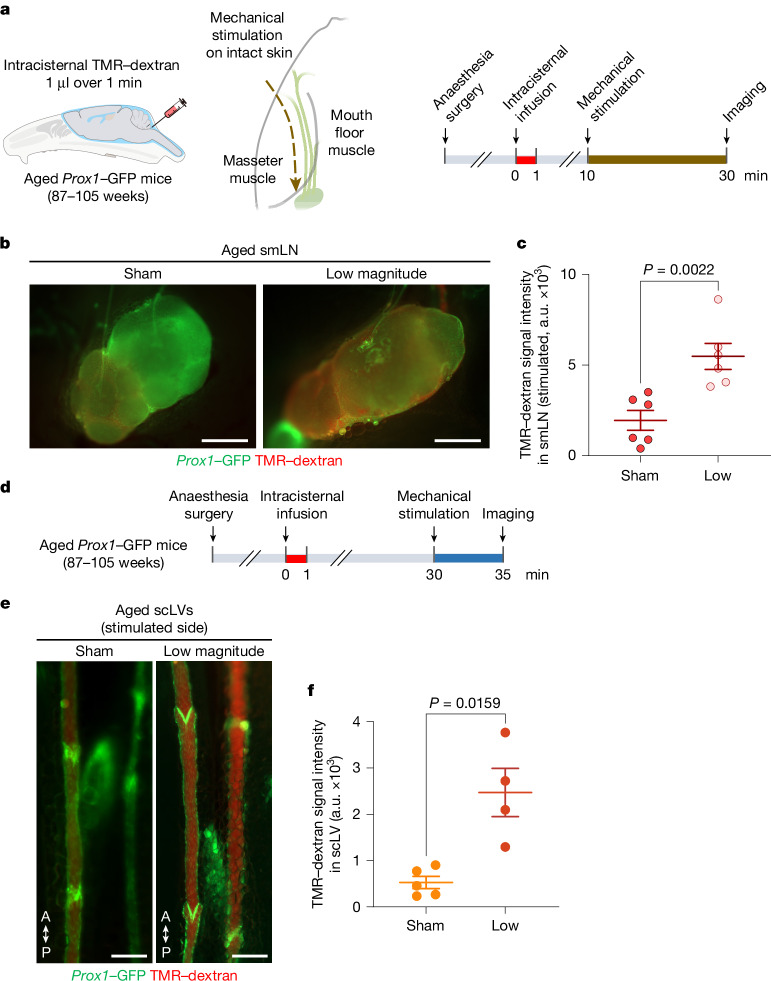

To determine whether CSF outflow could be increased by non-invasive mechanical manipulation through the skin, we developed a force-regulated mechanical stimulator (see Methods for details) and compared low (0.01–0.02 kilogram-force (kgf)) and high (0.04–0.08 kgf) magnitude forces (Extended Data Fig. 13a,b and Supplementary Video 2). Using this device on urethane anaesthetized mice, we compared the effects of downward strokes in three regions of intact skin: (1) from the periorbital area to the mandible; (2) from the nasal sidewall to the mandible; and (3) from rostral to caudal along the path of scLV-1 and scLV-2 en route to the submandibular lymph node (Extended Data Fig. 13c). Each session consisted of two cycles of 10 strokes each of 2-s duration (4 strokes to region 1, 4 strokes to region 2 and 2 strokes to region 3). Two 10-stroke cycles over 40 s were followed by a 20-s rest period (Extended Data Fig. 13c and Supplementary Video 2).

Extended Data Fig. 13. Features and use of mechanical stimulator for increasing CSF drainage through superficial cervical lymphatics.

a, Drawing and photograph of the precision force-regulated mechano-stimulator consisting of an amplifier, force sensor, handle, shaft connecting the tip to the force sensor, and replaceable tip. The replaceable tip was an oval-shaped cotton ball, with a major axis of 1 cm and minor axis of 0.5 cm, that was attached to a 1-cm long rod securely connected to the shaft. The length of the handle was 9 cm. The force sensor made of silicone and conductive fabric was connected to the replaceable tip through the shaft. The measured force was transmitted to an amplifier connected to a personal computer. b, Graphs comparing low-magnitude (0.01-0.02 kgf) and high-magnitude (0.04-0.08 kgf) forces generated by the mechanical stimulator every 2 s over 20 s. c, Drawing (left) showing the three stimulation paths (numbered brown dashed arrows) in three regions of intact skin of mice along the course of superficial cervical lymphatics scLV-1 and scLV-2 to promote CSF flow toward the submandibular lymph node (smLN). Region 1 was from the periorbital area to the mandible. Region 2 was from the nasal sidewall to the mandible. Region 3 was along the paths of scLV-1 and scLV-2 to the submandibular lymph node. Each 1-min session of mechanical stimulation consisted of two sequences of 10 two-second strokes each, with a 20-sec rest period after the two sequences. Each sequence included four two-second strokes in Region 1, four in Region 2, and two in Region 3 (right).

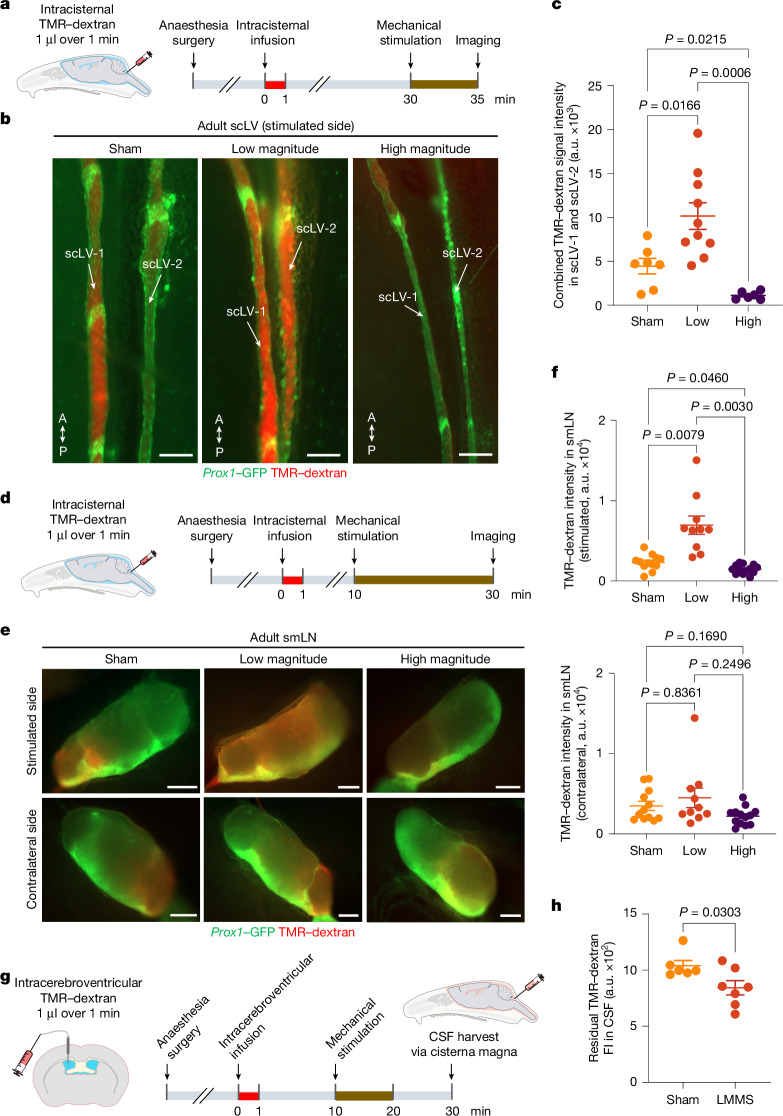

Treatments consisted of five 1-min sessions of mechanical stimulation for tracer studies from the SAS to scLV-1 and scLV-2 (Fig. 6a). The TMR–dextran tracer was infused intracisternally 30 min before the onset of mechanical stimulation (Fig. 6a). CSF drainage was assessed by measuring tracer fluorescence in scLV-1 and scLV-2 at the end of the stimulation (Fig. 6a). TMR–dextran fluorescence more than doubled (2.29-fold mean increase) in scLV-1 and scLV-2 after low-magnitude stimulation over 5 min (Fig. 6b,c). By comparison, after high-magnitude stimulation over 5 min, scLV-1 and scLV-2 were constricted in some places and had 89% less TMR–dextran fluorescence than the sham (no stimulation; Fig. 6b,c).

Fig. 6. Increased CSF drainage by non-invasive mechanical stimulation of scLVs.

a, Sequence of intracisternal infusion of TMR–dextran into Prox1–GFP mice followed by mechanical stimulation at 30 min for 5 min, then imaging of TMR–dextran in scLV-1 and scLV-2 at 35 min. b,c, Fluorescence images and measurements of TMR–dextran in scLV-1 and scLV-2. Sham compared with mechanical stimulation (b). Anatomical positions are indicated. Scale bars, 200 μm. Each dot represents combined TMR–dextran fluorescence intensity in scLV-1 and scLV-2 from one mouse (c). n = 7 (sham), n = 10 (low magnitude) and n = 6 (high magnitude) from three independent experiments. The error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated by Brown–Forsythe analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by two-tailed Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison post-hoc test. d, Sequence of intracisternal infusion of TMR–dextran into Prox1–GFP mice followed by mechanical stimulation at 10 min for 20 min, then imaging of TMR–dextran in the smLN at 30 min. e,f, Fluorescence images (e) and measurements (f) of TMR–dextran in the smLN of the stimulated side (top) versus unstimulated side (bottom). Scale bars, 500 μm. Each dot is the value for one mouse. n = 12 (sham), n = 10 (low magnitude) and n = 13 (high magnitude) from three independent experiments. The error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated by Brown–Forsythe ANOVA test followed by two-tailed Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison post-hoc test. g,h, Sequence of intracerebroventricular infusion of TMR–dextran into Prox1–GFP mice followed by low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS) at 10 min for 10 min and removal of CSF at 30 min (g). Fluorescence in CSF after LMMS or sham is also shown (h). Each dot is the value for one mouse. n = 6 (sham) and n = 7 (LMMS) from three independent experiments. The error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. P values were calculated by two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. FI, fluorescence intensity.

For tracer studies from the SAS to cervical lymph nodes, treatments consisted of 20 1-min sessions of mechanical stimulation (Fig. 6d). The TMR–dextran tracer was infused at the cisterna magna 10 min before the onset of mechanical stimulation, and CSF drainage was assessed by measuring tracer fluorescence in submandibular lymph nodes at the end of the stimulation (Fig. 6d–f). TMR–dextran fluorescence tripled (3.01-fold mean increase) in the ipsilateral lymph node after low-magnitude mechanical stimulation over 20 min but not after high-magnitude stimulation (Fig. 6d–f), where values were less in the ipsilateral lymph nodes (Fig. 6d–f). In comparison, no differences among the three groups were found in the contralateral lymph nodes (Fig. 6d–f).

To determine whether mechanical stimulation of facial and neck skin increased CSF clearance from the SAS, instead of just pushing lymph in scLV-1 and scLV-2 into cervical lymph nodes, we injected TMR–dextran into a lateral ventricle and applied 10 1-min sessions of low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (Fig. 6g). Measurements of CSF removed at the cisterna magna revealed a 23% lower concentration of TMR–dextran in the stimulation group than in the sham group (P = 0.03; Fig. 6h and Supplementary Fig. 19), consistent with increased CSF clearance from the SAS.

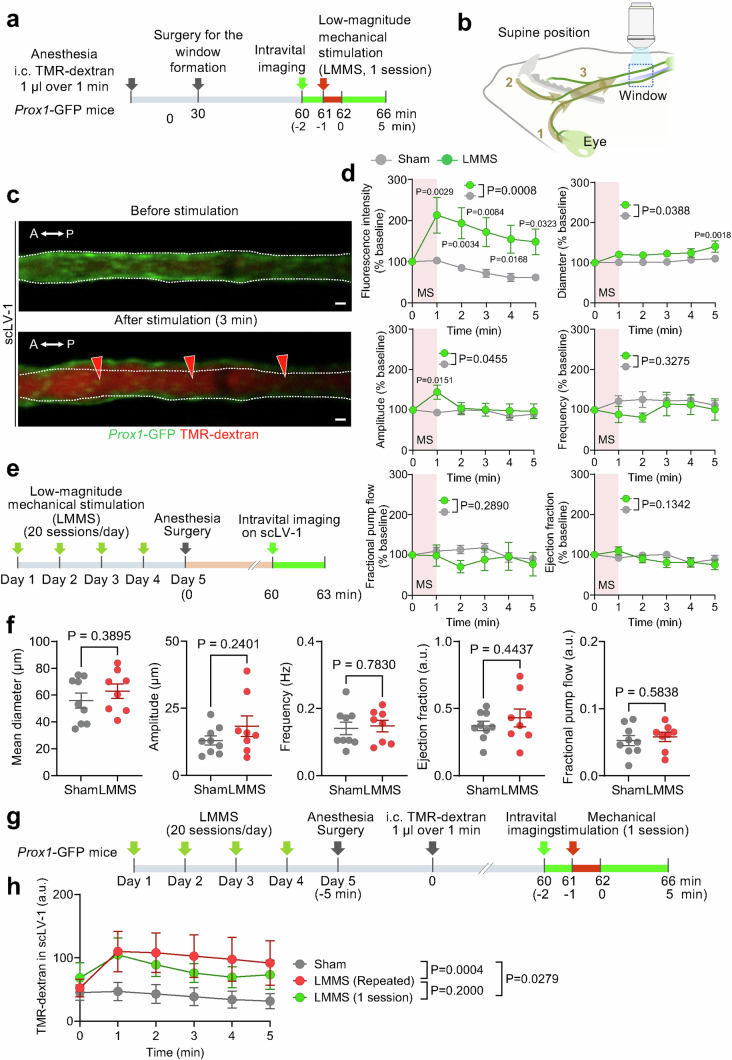

We next determined the magnitude and duration of the increase in CSF outflow after a 1-min session of low-magnitude mechanical stimulation by using TMR–dextran fluorescence in scLVs as a readout (Extended Data Fig. 14a,b). TMR–dextran fluorescence measured by intravital imaging was more than doubled at 1 min after stimulation, and the increase was sustained throughout the 5-min monitoring period (Extended Data Fig. 14c,d). Mechanical stimulation was also accompanied by a small increase in the diameter of scLVs and a transient increase in the amplitude of spontaneous contractions, but no consistent change in spontaneous contraction ejection fraction, frequency or fractional pump flow (Extended Data Fig. 14d).

Extended Data Fig. 14. Low-magnitude mechanical stimulation increases CSF outflow through superficial cervical lymphatics with sustained efficacy after 4 daily sessions.

a, Sequence of surgical exposure of superficial cervical lymphatics scLV-1 in Prox1-GFP mice, a 20-min stabilization period, and intravital imaging during and 5 min after 1-min of low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS) of the face and neck as in Extended Data Fig. 13. Measurements were made at 1-min intervals for 5 min after stimulation. b, Drawing showing the relative locations of region 3 of LMMS of scLV-1 and scLV-2 and the downstream window for intravital imaging (blue dashed box). c, Intravital images of scLV-1 of Prox1-GFP mouse downstream before and after one session of LMMS. White dashed lines outline the vessel border before LMMS. Red arrowheads mark regions of TMR-dextran fluorescence. Scale bars, 20 μm. Anatomical positions are indicated in the top left corner: A, anterior; P, posterior. d, Measurements of temporal changes in TMR-dextran fluorescence, as an index of CSF outflow, and five parameters of spontaneous contraction of scLV-1 at the onset and 1-5 min after a 1-min session of LMMS (MS). At 1-min, TMR-dextran values are more than double the onset and continue to be significantly greater throughout the 5-min monitoring period. Other values show a small increase in scLV-1 mean diameter and transient increase in amplitude of spontaneous contractions but no significant change in ejection fraction, contraction frequency, or fractional pump flow. All values are expressed as % of mean baseline fluorescence before LMMS. Each dot is the mean value for n = 9 (sham), n = 7 (LMMS) mice of both sexes from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate s.e.m. P values calculated by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. e, Sequence of repeated low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS, 20 sessions/day) for 4 days followed on day 5 by surgical exposure and intravital imaging of superficial cervical lymphatic scLV-1 in adult (8–12 weeks) Prox1-GFP mice. Intravital imaging began after a 30-min stabilization period and lasted 3 min. f, Measurements show no difference between the sham and stimulated group in values for mean diameter, spontaneous contraction amplitude, ejection fraction, frequency, or fractional pump flow in scLV-1. Each dot is the value for one mouse. n = 9 (sham), n = 8 (LMMS) mice per group in three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. a.u., arbitrary unit. Intravital imaging values were averaged over 3 min for each mouse. P values calculated by two-tailed Welch’s t test. g, Sequence of repeated LMMS (20 sessions/day) for 4 days followed by surgical exposure, intracisternal infusion of TMR-dextran, intravital imaging of scLV-1, low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (1 session) in adult Prox1-GFP mice, and measurement of TMR-dextran fluorescence in scLV-1 within the imaging window. Intravital imaging began after a 30-min stabilization period and lasted 5 min after LMMS (1 session) or sham. h, Comparison of three conditions showing significantly greater TMR-dextran fluorescence in scLV-1 in the repeated stimulation group than in the sham group. The magnitude of TMR-dextran fluorescence in the scLV-1 after repeated stimulation over 4 days did not differ from corresponding values after one stimulation session (data from Extended Data Fig. 14d). Each dot is the value for n = 9 (sham), n = 7 (1 session LMMS or repeated LMMS) mice of both sexes from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. a.u., arbitrary unit. P values calculated by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA.

Repeated low-magnitude mechanical stimulation (20 1-min sessions daily) for 4 days did not change the spontaneous contraction parameters (Extended Data Fig. 14e,f) or impair the stimulation-mediated increase in CSF outflow through scLV-1 (Extended Data Fig. 14g,h). These findings provide promising evidence that prolonged mechanical stimulation of lymphatics in the face and neck can promote a sustained increase in CSF outflow.