Abstract

Background and objectives

Acute kidney injury (AKI) poses a serious clinical challenge, particularly in high-risk environments, due to its association with increased morbidity and mortality. Traditional diagnostic markers, such as serum creatinine, often detect AKI only after significant kidney damage has occurred, limiting opportunities for early intervention. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) has emerged as a promising early biomarker due to its rapid upregulation following kidney ischemia. NGAL supports renal recovery by reducing toxicity and promoting tubular regeneration via heme oxygenase-1 activity. This study aimed to validate the BioPorto ProNephro AKI™ turbidimetric immunoassay for urinary NGAL on the Ortho Vitros XT7600 analyzer and evaluate its clinical utility in detecting early-stage AKI.

Design and methods

Assay performance was evaluated in accordance with CLSI guidelines, assessing precision, linearity, method agreement, specificity, and reference range. Method comparison involved 20 urine samples, while reference range verification used 57 pediatric samples. A clinical validation study included 21 pediatric CRRT patient samples to assess real-world diagnostic performance.

Results

The assay demonstrated strong precision (intra-assay CV: 1.3–1.8 %; inter-assay CV: 1.8–2.7 %) and excellent linearity (18–1140 ng/mL; extended to 15,000 ng/mL with dilution). High correlation (r = 0.9836) was observed in method comparison. Specificity tests showed minimal interference. Clinical validation yielded 76.19 % sensitivity and 100 % specificity for AKI detection.

Conclusions

The BioPorto ProNephro AKI™ assay on the Ortho Vitros XT7600 shows high sensitivity and specificity for urinary NGAL detection in pediatric patients, enabling early AKI identification, timely intervention, and potentially improved clinical outcomes through enhanced diagnostic performance.

Keywords: Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, Acute kidney injury, BioPorto ProNephro AKI™, Ortho vitros XT7600, Method validation, Pediatric population, Urinary biomarker

Highlights

-

•

NGAL assay on Ortho Vitros XT7600 demonstrates high analytical precision, linearity, and minimal interference.

-

•

NGAL assay did not show any analytical interferences with common urine interferents.

-

•

Clinical validation demonstrated 100 % specificity and 76.2 % sensitivity for detecting AKI in children.

1. Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a significant and often life-threatening condition characterized by a rapid decline in kidney function, leading to the accumulation of waste products, electrolyte imbalances, and fluid balance disturbances [1]. AKI affects millions worldwide and is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality, particularly among critically ill patients [2]. In addition to immediate health complications, AKI can result in long-term effects, including an increased risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cardiovascular conditions, underlining its impact on long-term health and healthcare costs [3].

In pediatric populations, AKI is a critical concern, particularly among children undergoing high-risk procedures such as cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), where incidence rates can reach up to 40 % [[4], [5], [6]]. AKI in pediatric patients has been associated with significant morbidity and mortality, with reported mortality rates ranging from 20 % to 79 %, depending on the population and AKI severity [7]. The long-term consequences of pediatric AKI are especially concerning, as kidney injury during childhood may predispose patients to CKD and other health complications later in life. Early identification of AKI is essential for effective intervention, as therapeutic measures are most beneficial when applied soon after injury [8]. However, traditional markers such as serum creatinine (SCr) are often inadequate for early AKI detection, as they typically begin to rise only after a substantial loss of kidney function, often after a 50 % reduction [9]. The limitations of SCr are further compounded by its dependency on non-renal factors, including age, gender, muscle mass, and hydration status, which can lead to delayed or inaccurate AKI diagnosis in pediatric patients [10]. These limitations underscore the urgent need for more sensitive and specific biomarkers that can detect AKI at an earlier stage, providing a more reliable means of assessment and enabling timely interventions in high-risk pediatric settings.

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) has emerged as a promising early biomarker for AKI. Studies have demonstrated that urinary NGAL (uNGAL) levels can rise significantly within hours of renal injury, providing a more timely indication of kidney dysfunction compared to traditional markers [[11], [12], [13]]. This rapid elevation makes uNGAL a valuable tool for all populations affected by AKI, as swift intervention can significantly improve outcomes. Previous study observed a marked increase in uNGAL levels as early as 2 h post-CPB, well before any rise in SCr [14]. Moreover, uNGAL has shown predictive utility in various clinical contexts, including renal transplantation and critically ill patients [[15], [16], [17]]. Given these advantages, uNGAL is a key candidate for incorporation into clinical practice, particularly in the pediatric setting where the etiology of AKI can be heterogeneous [18].

Despite the promising potential of the NGAL assay, it is not yet widely available in the United States, leading to a gap in clinical practice [19]. To address this, we have undertaken the validation of the analytical performance of the recently FDA-approved Bioporto ProNephro AKI™ (NGAL) quantitative immunoassay [20] on the Ortho Vitros XT7600 automated chemistry analyzer. This study presents the first analytical and clinical validation of the BioPorto ProNephro AKI™ urinary NGAL assay on the Ortho Vitros XT7600 analyzer in a pediatric population. This validation aims to empower physicians to order NGAL testing, which can provide valuable guidance in managing AKI and enhancing patient care.

2. Materials and methods

The Bioporto ProNephro AKI™ turbidimetric immunoassay (BioPorto Diagnostics A/S, Hellerup, Denmark) was evaluated for performance on the Ortho Vitros XT7600 automated chemistry analyzer (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Raritan, NJ). The ProNephro AKI assay provides quantitative measurements of NGAL in ng/mL, making it suitable for clinical use. For this validation study, remainder human urine specimens were obtained from the clinical laboratory from de-identified pediatric patients without known kidney, cardiac, or inflammatory disease, specifically those without cardiac or kidney disease. Urine samples were collected in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and stored at −80 °C to maintain specimen integrity. These samples were later used to establish reference ranges for the assay. Additionally, urine specimens from patients diagnosed with AKI were collected, de-identified, and included in the study to assess the assay's clinical applicability. All studies were approved as exempt by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

2.1. Analytical validation

Studies were conducted to evaluate precision (including both intra- and inter-assay), analytical sensitivity, analytical interferences, method comparison, and verification of reference intervals. Analytical performance specifications for precision, linearity, and sensitivity were established based on manufacturer-provided targets, prior literature benchmarks for NGAL assays, and clinical performance requirements relevant to pediatric AKI diagnostics.

Precision studies: Intra- and inter-assay precision studies were performed in accordance with CLSI guidelines. Within-run precision was assessed by measuring two levels of controls, each tested 20 times in a single run. Between-run precision was determined by analyzing two control levels (BioPorto-provided low and high QC materials) once daily over 5 consecutive days, in accordance with CLSI EP15-A3. The coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated for both intra- and inter-run precision studies using the formula: standard deviation/mean × 100.

Linearity: Linearity was assessed using linear regression without forced intercept, and percent bias was calculated relative to target concentrations. The range spanned the manufacturer's claimed AMR of 50–1500 ng/mL. Linearity studies were carried out by measuring a set of 5 manufacturer-provided samples with assigned values ranging from 29 to 1294 ng/mL with allowable systematic error set at 10 %. Dilution verification was performed by measurement of 6 high-concentration samples neat or diluted 10X, and results were considered acceptable if measured values differed by less than 20 %. Dilution recovery was evaluated using 1:10 dilution with 0.9 % saline on six high-concentration urine samples measured in duplicate. Mean percent difference after adjusting for dilution factor was −17.1 %, with acceptable directional consistency across all samples (Table 3).

Table 3.

Recovery results for 10 × dilution of high-concentration NGAL samples.

| Sample ID | Neat Results (ng/mL) | Mean Neat | Diluted Results (ng/mL × 10) | Mean Diluted | % Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 474–492 | 483 | 4020–3680 | 3850 | −13.7 % |

| 2 | 903–1060 | 982 | 9370–8120 | 8745 | −11.0 % |

| 3 | 1600–1490 | 1545 | 11,800–12,000 | 11,900 | −23.0 % |

| 4 | 596–598 | 597 | 5920–5790 | 5855 | −1.9 % |

| 5 | 2070–2460 | 2265 | 16,300–16,800 | 16,550 | −26.9 % |

| 6 | 1620–1650 | 1635 | 13,200–12,800 | 13,000 | −20.6 % |

| Mean | −17.1 % |

Analytical sensitivity: Analytical sensitivity was assessed by measuring 10 replicates of the blank (Standard A) to determine the limit of blank (LoB), defined as 10 times the blank signal. The limit of detection (LoD) was calculated as LoB + 1.645 × SD from low-concentration urine samples. Limit of quantitation (LoQ) was defined as the lowest concentration with ≤20 % CV using two different reagent lots.

Method agreement: Method agreement of the Bioporto NGAL turbidimetric immunoassay on the Ortho Vitros XT7600 was determined by comparison with previously tested specimens from from CLIA-certified laboratories (Nationwide Children's Hospital and Colorado Children's Hospital), both using the same manufacturer's assay on Vitros analyzers, in line with CLSI EP09-A3 guidelines. A total of 20 urine specimens were collected following the same protocol, frozen at −80 °C, and thawed just prior to analysis.

Analytical Specificity: Analytical specificity was assessed by spiking samples with known concentrations of hemoglobin, protein, conjugated bilirubin (Sun Diagnostics, New Gloucester, ME), MEDTOX positive drug control (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), varying pH levels and lymphocytes.

Reference range verification: The manufacturer-provided reference range (≤50 ng/mL) [17] was verified using 57 urine specimens from pediatric patients (age range: 3 months–17 years) without known kidney, cardiac, or inflammatory disease at our institution. The specimens were collected from patients aged 3 months to 17 years, including both males and females. A thorough chart review was conducted to exclude samples from patients with a diagnosis of AKI or other kidney and heart diseases, as these conditions are known to elevate NGAL concentrations.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis for method agreement, precision, linearity, and reference range studies was carried out using EP evaluator. Method comparison studies were evaluated using Deming regression, and a Bland-Altman plot was generated to evaluate proportional bias.

Clinical validation: Urine samples were collected from pediatric patients (age range: 3 months–17 years) admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) at Texas Children Hospital with suspected AKI. The inclusion criteria comprised: (1) age ≤18 years at the time of hospital admission, (2) clinical suspicion of AKI due to underlying conditions such as sepsis, hyperuricemia, or hepatic failure, (3) availability of NGAL measurements. Patients were excluded if they had (1) chronic kidney disease, (2) active malignancy with prior nephrotoxic exposure, or (3) incomplete clinical records.

For each patient, demographic data, clinical presentation, and biochemical markers, including SCr levels, were extracted from the electronic medical records. NGAL levels were measured, with the predefined cutoff of 125 ng/mL indicating high risk for AKI (Stage 2–3) within 48–72 h. AKI diagnoses were extracted from patient medical records, based on clinical assessments performed by the treating teams in the PICU. No retrospective reclassification of AKI status was performed. Institutional criteria for AKI diagnosis align with KDIGO 2012 guidelines [27]. Key performance metrics were calculated, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and likelihood ratios (LR+ and LR-). Confidence intervals (CIs) were computed using Wilson's method for proportions. Patients with NGAL levels below detection limits and no clinical evidence of AKI were classified as true negatives.

3. Results

The NGAL assay demonstrated robust analytical performance.

Precision: The Bioporto NGAL turbidimetric immunoassay demonstrated high precision across concentration ranges. At the low concentration level (mean = 197.9 ng/mL), the within-run standard deviation (SD) was 3.0 ng/mL and the inter-run SD was 3.6 ng/mL, resulting in a total coefficient of variation (CV) of 1.8 % (95 % CI for SD: 2.8–5.3). At the high concentration level (mean = 488.1 ng/mL), the within-run SD was 6.8 ng/mL and CV was 1.4 % (95 % CI for SD: 5.2–10.0). These results meet the predefined precision verification goal of ≤10 % random error, and are within the 20 % total allowable error (TEa) for NGAL, confirming reproducibility of the assay across runs and concentrations (see Table 1 for intra- and inter-assay precision).

Table 1.

Within-run and between-day precision studies.

| Within-run |

Between-day |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | %CV | Mean | SD | %CV |

| 217 ng/mL | 3.0 | 1.4 % | 197 ng/mL | 3.6 | 1.8 % |

| 483 ng/mL | 5.0 | 1.0 % | 488 ng/mL | 6.8 | 1.4 % |

Linearity and reportable range: The Bioporto NGAL turbidimetric immunoassay was determined to be linear between 18.05 and 1140 ng/mL, with total observed error of 2.1 %. Dilution studies performed with high-concentration samples verified linearity of response up to a 10X dilution. Limit of blank was measured as 0 ng/mL, with limit of detection 18.13 ng/mL, and limit of quantitation of 30 ng/mL. The clinical reportable range for the NGAL was verified to be < 50–15000 ng/mL (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Scatter and residual plots for linearity studies of the urinary NGAL on the Ortho Vitros XT7600 analyzer. Samples used for these studies were provided by the manufacturer with assigned values.

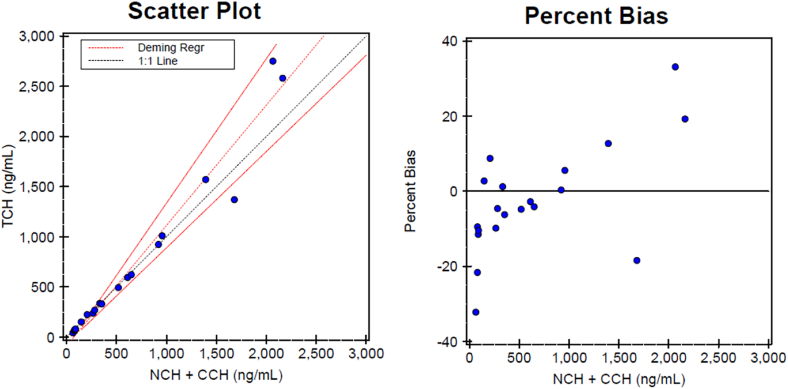

Method agreement/Method comparison: Method comparison studies of the Bioporto NGAL on the Ortho Vitros XT7600 automated chemistry analyzer with the manufacturer's turbidimetric immunoassay indicated excellent agreement between the two methods. Comparison to turbidimetric immunoassay in the range of NGAL 42.7–2750 ng/mL, yielded an R = 0.9836 and percent bias of 7.20 % (Fig. 2). Deming regression showed a slope of 1.209 (95 % CI: 1.101–1.317) and intercept of −87.98 ng/mL (95 % CI: 187.05 to 11.08). The mean bias was 46.33 ng/mL (7.2 %), and correlation coefficient was 0.9836. Visual plots supported assumptions of homoscedasticity and no proportional bias. Lin's Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) was 0.98.

Fig. 2.

Deming regression and Bland-Altman plots for method comparison of the urinary NGAL on the Ortho Vitros XT7600 analyzer.

Reference range: Reference range verification was conducted using a total of 57 samples classified as normal based on our exclusion criteria. Three samples measured slightly above the 50 ng/mL threshold, with values of 56.8, 57.6, and 53.3 ng/mL, while all remaining specimens fell within the expected reference range of ≤50 ng/mL. Despite the elevated NGAL levels in these three samples, no evidence of acute kidney injury or cardiac involvement was observed in the respective patients. The elevated NGAL levels may be attributed to other factors, such as the patients' underlying medical histories. Based on these findings, our reference interval for patients without kidney and/or cardiac disease was confirmed to be ≤ 50 ng/mL.

Analytical interferences: Interference studies were performed to assess the impact of pH, hemoglobin (2000 mg/L), bilirubin (200 mg/L) and protein (60,000 mg/L), and positive drug levels using three sample pools with NGAL concentrations of approximately 140 ng/mL, 172 ng/mL, and 254 ng/mL. Recovery was assessed relative to baseline samples No significant interference was observed. The potential effect of leukocytes was also evaluated using varying leukocyte concentrations in a sample pool with an NGAL concentration of approximately 105 ng/mL, and no significant interference was observed in this analysis either (Table 2).

Table 2.

Interference studies.

| Interferent | Sample 1 (ng/mL) | Recovery (%) | Sample 2 (ng/mL) | Recovery (%) | Sample 3 (ng/mL) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neat (baseline) | 140 | – | 172 | – | 247 | – |

| pH 3–4 | 143 | 102.1 % | 181 | 105.2 % | 265 | 107.3 % |

| pH 8–9 | 149 | 106.4 % | 170 | 98.8 % | 274 | 110.9 % |

| Hemoglobin (2000 mg/L) | 151 | 107.9 % | 175 | 101.7 % | 244 | 98.8 % |

| Bilirubin (200 mg/L) | 158.6 | 113.3 % | 188.5 | 109.6 % | 263.9 | 106.8 % |

| Protein (60,000 mg/L) | 152.1 | 108.6 % | 176.8 | 102.8 % | 260 | 105.3 % |

| Positive Drug Control | 153.2 | 109.4 % | 190 | 110.5 % | 270 | 109.3 % |

| Without Leucocytes | 105 | |||||

| 500 Leucocytes/μL | 99.4 | 94.7 % |

3.1. Clinical validation of NGAL assay in AKI patients

Clinical validation of the BioPorto ProNephro AKI™ turbidimetric immunoassay was conducted using 21 urine samples from pediatric patients admitted to the PICU, all of whom were receiving continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) at the time of collection. Among these: 13 samples were from patients with confirmed Stage 3 AKI, 5 samples were from patients with oliguric AKI or AKI secondary to hyperuricemia, 2 samples were from patients with tumor lysis syndrome and resultant renal failure, and 1 sample was from a patient with no AKI at the time of collection, though the patient subsequently progressed to Stage 3 AKI approximately 20 days later (Supplementary file 1). This cohort reflects a spectrum of AKI etiologies, including sepsis, liver failure, hyperuricemia, and malignancy-related renal injury, demonstrating the assay's applicability across diverse pediatric critical care scenarios.

Out of the 21 samples, 16 were identified as true positives (NGAL ≥125 ng/mL with confirmed AKI), 1 as a true negative (NGAL <125 ng/mL with no AKI), and 4 as false negatives (NGAL <125 ng/mL despite the presence of AKI). No false positives were observed, highlighting the high specificity of the assay (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

NGAL (Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin) levels in 21 pediatric patients with AKI undergoing CRRT. The dashed black line at 125 ng/mL represents the cutoff for distinguishing high and low AKI risk. The plot demonstrates the association between higher NGAL levels and more severe kidney dysfunction.

The performance metrics of NGAL for AKI detection were: Sensitivity: 76.19 % (95 % CI: 54.91 %–89.37 %), Specificity: 100.00 % (95 % CI: 15.81 %–100.00 %), PPV: 100.00 % (95 % CI: 79.58 %–100.00 %), NPV: 16.67 % (95 % CI: 3.00 %–56.41 %), Positive Likelihood Ratio (LR+): Undefined (since specificity is 100 %), Negative Likelihood Ratio (LR-): 0.24 (95 % CI: 0.07–0.81) (Table 4)

Table 4.

Diagnostic method agreement of the NGAL test.

| Parameter | % or Ratio | 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 76.19 | 55–89 |

| Specificity | 100 | 5.5–100 |

| PPV | 100 | 80–100 |

| NPV | 16.67 | 3–56 |

| LR+ | ∞ | |

| LR- | 0.24 | 0.07–0.81 |

These results indicate that NGAL strongly correlates with AKI diagnosis in critically ill pediatric patients, particularly for ruling in AKI when levels exceed 125 ng/mL. The 100 % PPV suggests that a high NGAL value is highly predictive of AKI, making it a reliable early biomarker. However, 5 samples had NGAL levels below the cutoff, resulting in a low negative predictive value (NPV) of 16.67 %.

4. Discussion

The BioPorto ProNephro AKI™ turbidimetric immunoassay demonstrated excellent analytical performance. Despite differences in platforms across existing studies—including Beckman Coulter AU480 and Roche Cobas c502—our study, which utilized the Ortho Vitros XT7600 analyzer, and has not been reported before on this platform, confirmed comparable or superior assay characteristics. The Vitros platform is commonly available in pediatric hospital laboratories, making this validation highly relevant for real-world implementation. Precision, specificity, and sensitivity were excellent, as shown in both this and prior studies on other automated platforms [24,25]. Additionally, the assay exhibited minimal interference from substances like hemolysis, bilirubin, protein or drug. These characteristics support its suitability for integration into clinical laboratories. We also evaluated possible interference from high WBC counts. Although some literature reports leukocyte interference with NGAL assays, we did not observe this effect in our study [26].

One of the strengths of our study is the pediatric focus, which is relatively underrepresented in the literature. Our pediatric cohort of 21 samples provides valuable reference ranges and clinical insight, particularly in the context of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). Future studies will be aimed to examining clinical utility in larger pediatric populations presenting with different stages of AKI.

The accurate and timely detection of AKI is crucial for improving outcomes in pediatric patients, particularly those undergoing high-risk procedures like cardiac surgery or CRRT. Traditional markers, such as SCr and urine output, are commonly used to assess renal function but have significant limitations in detecting early-stage AKI. SCr levels can be influenced by various non-renal factors, including age, muscle mass, and hydration status, often leading to a delayed response in detecting renal impairment [21]. Typically, creatinine levels may not rise until there is a substantial loss of renal function, often lagging 24–48 h after injury [22]. This delay can result in significant and potentially irreversible kidney damage before any clinical intervention can occur. In patients undergoing CRRT, the reliance on creatinine as a marker is further challenged, as clearance through dialysis can prevent expected rises in SCr, making early AKI detection even more complex.

In contrast, NGAL has emerged as a promising biomarker for AKI due to its rapid elevation in response to renal injury. NGAL can be detected in both plasma and urine within hours of kidney insult, providing a much earlier indication of renal dysfunction than SCr [23]. This rapid response highlights NGAL's potential as a critical tool for early AKI diagnosis, particularly in vulnerable pediatric populations requiring CRRT. Our study supports these findings, as we observed NGAL levels above 125 ng/mL in 16 of 21 samples. However, not all of the clinical samples were from patients with confirmed AKI at the time of sample collection; one sample was from a patient who did not have AKI at the time but later developed Stage 3 AKI approximately 20 days after, while two others were from patients with AKI secondary to hyperuricemia. Importantly, 5 samples exhibited NGAL values below the 125 ng/mL cutoff, despite corresponding with patients who either had AKI or were at risk for AKI. Some of these cases likely reflect the complex pathophysiology of pediatric patients undergoing CRRT or those with multi-organ dysfunction, where NGAL expression may be suppressed or altered due to various clinical conditions. The reason for NGAL failing to rise in these instances could be multifactorial, involving early-stage kidney injury, immunomodulatory effects, and therapeutic interventions.

When comparing our clinical validation with recent studies, several key aspects emerge. Previous studies on NGAL validation and clinical implementation have underscored the assay's versatility across platforms. Despite technical variation, consistent diagnostic method agreement across studies reinforces NGAL's robustness as a biomarker. The major limitation of this study, which will be addressed in future studies, is that we did not obtain samples from patients as they presented in the ED with varying stages of AKI.

Importantly, our study's results demonstrate that NGAL levels above 125 ng/mL correlate with AKI in pediatric CRRT patients, with high sensitivity (76.2 %) and perfect specificity (100 %) for AKI detection. This aligns with findings from Clinical Implementation of NGAL testing, where the NGAL assay showed high method agreement in detecting AKI in general hospital populations. However, we observed a low negative predictive value (NPV) of 16.7 %, suggesting that NGAL values below the cutoff do not entirely rule out AKI in our patient population, particularly when non-traditional AKI mechanisms such as hepatic dysfunction or sepsis might influence NGAL levels. Although the 125 ng/mL cutoff showed excellent specificity (100 %), its sensitivity (76.2 %) may be limited in cases of non-traditional AKI mechanisms such as hepatic failure or hyperuricemia. NGAL should complement, not replace, other diagnostic tests. These findings reinforce the need to interpret NGAL levels within a broader clinical context, especially in critically ill pediatric patients with complex multi-organ involvement.

Our findings also highlight NGAL's utility in clinical practice: the assay's robust performance across different platforms (e.g., Ortho Vitros XT7600 in our study versus Roche Cobas c502 in other studies) suggests that it could be easily integrated into various clinical settings. Moreover, the absence of significant interference from substances such as hemolysis, bilirubin, or protein further strengthens its clinical applicability. These results position the BioPorto ProNephro AKI™ assay as a highly reliable tool for early AKI detection, especially in high-risk pediatric patients undergoing CRRT. In addition, since NGAL is mainly from neutrophils, we assessed the effect of high WBC count on NGAL, and while there is a small report of interference of leukocytes with NGAL assay, we failed to observe the same [26].

Despite the promising findings, further research is necessary to address some limitations. The five false-negative cases (patients with AKI but NGAL <125 ng/mL) highlight that NGAL alone may not be sufficient to identify all cases of AKI, especially in complex clinical settings. Non-traditional AKI mechanisms, such as hepatic dysfunction, sepsis, or multi-organ dysfunction, may alter NGAL expression, leading to lower sensitivity. Additionally, potential interference from rheumatoid factor (RF) was not evaluated. Given its low prevalence in pediatric urine, it was not prioritized but will be included in future validations to expand clinical applicability. Variability in NGAL levels across different studies and assay techniques underscores the need for standardization in measurement methods and cut-off values to improve the diagnostic method agreement and applicability of NGAL as a biomarker for AKI. While our findings support the utility of NGAL in early AKI detection, the relatively small sample size, especially for clinical performance metrics, limits broader generalization. Additionally, the high specificity observed (100 %) may be influenced by the sample's ICU-only composition and limited size. Future studies with larger, multicenter cohorts are necessary to validate these findings and refine cutoff thresholds.

Additionally, while NGAL has demonstrated sensitivity and specificity for AKI, its role in distinguishing AKI from other inflammatory conditions remains to be fully clarified. In critically ill pediatric patients, systemic inflammation, sepsis, and multi-organ dysfunction could impact NGAL expression, necessitating further investigation into its specificity in these contexts. Standardizing NGAL measurement protocols and utilizing more homogeneous patient populations could enhance its clinical utility for early diagnosis and management of AKI in pediatric patients.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the BioPorto ProNephro AKI™ turbidimetric immunoassay is well validated analytically on the Ortho Vitros 7600 and clinically, it could lead to a significant advancement in the early detection of AKI in pediatric populations, particularly in high-risk settings such as cardiac surgery and CRRT-dependent patients.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nazmin Bithi: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ridwan B. Ibrahim: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Estella L. Tam: Methodology, Formal analysis. Radwa Almamoun: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. Annette C. Frenk Oquendo: Formal analysis. Ayse Akcan-Arikan: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. Sridevi Devaraj: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Sridevi Devaraj reports equipment, drugs, or supplies was provided by BIOPORTO DIAGNOSTICS INC. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Nazmin Bithi and Ridwan B. Ibrahim were supported by the Ching Nan Ou Fellowship Endowment in Clinical Chemistry. We also thank BioPorto Diagnostics for providing some of the validation kits for the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plabm.2025.e00486.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Kellum J.A., Romagnani P., Ashuntantang G., Ronco C., Zarbock A., Anders H.J. Acute kidney injury. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2021 Jul 15;7(1):52. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00284-z. PMID: 34267223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kam Tao Li P., Burdmann E.A., Mehta R.L. World kidney day steering committee 2013. Acute kidney injury: global health alert. J Nephropathol. 2013 Apr;2(2):90–97. doi: 10.12860/JNP.2013.15. Epub 2013 Apr 1. PMID: 24475433; PMCID: PMC3891141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gameiro J., Marques F., Lopes J.A. Long-term consequences of acute kidney injury: a narrative review. Clin Kidney J. 2020 Nov 19;14(3):789–804. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfaa177. PMID: 33777362; PMCID: PMC7986368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma A., Chakraborty R., Sharma K., Sethi S.K., Raina R. Development of acute kidney injury following pediatric cardiac surgery. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2020 Sep 30;39(3):259–268. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.20.053. PMID: 32773391; PMCID: PMC7530361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jefferies J.L., Devarajan P. Early detection of acute kidney injury after pediatric cardiac surgery. Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2016 Jun;41:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2016.01.011. PMID: 27429538; PMCID: PMC4943672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan S.M. Acute kidney injury after pediatric cardiac surgery. Pediatr Neonatol. 2019 Feb;60(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2018.03.007. Epub 2018 Mar 30. PMID: 29891225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girling B.J., Channon S.W., Haines R.W., Prowle J.R. Acute kidney injury and adverse outcomes of critical illness: correlation or causation? Clin Kidney J. 2019 Nov 18;13(2):133–141. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfz158. PMID: 32296515; PMCID: PMC7147312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao Z., Huang Q., Yang Y., Liu M., Chen Q., Huang J., Xiang Y., Long X., Zhao T., Wang X., Zhu X., Tu S., Ai K. Emerging early diagnostic methods for acute kidney injury. Theranostics. 2022 Mar 21;12(6):2963–2986. doi: 10.7150/thno.71064. PMID: 35401836; PMCID: PMC8965497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jana S., Mitra P., Roy S. Proficient novel biomarkers guide early detection of acute kidney injury: a review. Diseases. 2022 Dec 30;11(1):8. doi: 10.3390/diseases11010008. PMID: 36648873; PMCID: PMC9844481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng Y., Wang Q., Jin F., Tao T., Qin Q. Assessment of urine CCL2 as a potential diagnostic biomarker for acute kidney injury and septic acute kidney injury in intensive care unit patients. Ren. Fail. 2024 Dec;46(1) doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2024.2313171. Epub 2024 Feb 12. PMID: 38345000; PMCID: PMC10863526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanjeevani S., Pruthi S., Kalra S., Goel A., Kalra O.P. Role of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for early detection of acute kidney injury. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2014 Jul;4(3):223–228. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.141420. PMID: 25337484; PMCID: PMC4200548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz-Greenberg G., Malinchoc M., Broyles D.L., Oxman D., Hamrahian S.M., Maarouf O.H. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin predicts intensive care unit admission diagnosis: a prospective cohort study. Kidney. 2022 Jul 13;3(9):1502–1510. doi: 10.34067/KID.0001492022. 360 PMID: 36245663; PMCID: PMC9528386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostermann M., Zarbock A., Goldstein S., Kashani K., Macedo E., Murugan R., Bell M., Forni L., Guzzi L., Joannidis M., Kane-Gill S.L., Legrand M., Mehta R., Murray P.T., Pickkers P., Plebani M., Prowle J., Ricci Z., Rimmelé T., Rosner M., Shaw A.D., Kellum J.A., Ronco C. Recommendations on acute kidney injury biomarkers from the acute disease quality initiative consensus conference: a consensus statement. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020 Oct 1;3(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19209. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2029182. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29182. PMID: 33021646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishra J., Dent C., Tarabishi R., Mitsnefes M.M., Ma Q., Kelly C., Ruff S.M., Zahedi K., Shao M., Bean J., Mori K., Barasch J., Devarajan P. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2005 Apr 2-8;365(9466):1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74811-X. PMID: 15811456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kielar M., Dumnicka P., Gala-Błądzińska A., Będkowska-Prokop A., Ignacak E., Maziarz B., Ceranowicz P., Kuśnierz-Cabala B. Urinary NGAL measured after the first year post kidney transplantation predicts changes in glomerular filtration over one-year follow-up. J. Clin. Med. 2020 Dec 25;10(1):43. doi: 10.3390/jcm10010043. PMID: 33375581; PMCID: PMC7795618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cappuccilli M., Capelli I., Comai G., Cianciolo G., La Manna G. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a biomarker of allograft function after renal transplantation: evaluation of the current status and future insights. Artif. Organs. 2018 Jan;42(1):8–14. doi: 10.1111/aor.13039. Epub 2017 Dec 20. PMID: 29266311; PMCID: PMC5814881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romejko K., Markowska M., Niemczyk S. The review of current knowledge on neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023 Jun 21;24(13) doi: 10.3390/ijms241310470. PMID: 37445650; PMCID: PMC10341718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zappitelli M., Washburn K.K., Arikan A.A., Loftis L., Ma Q., Devarajan P., Parikh C.R., Goldstein S.L. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is an early marker of acute kidney injury in critically ill children: a prospective cohort study. Crit. Care. 2007;11(4) doi: 10.1186/cc6089. PMID: 17678545; PMCID: PMC2206519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allegretti A.S., Parada X.V., Endres P., Zhao S., Krinsky S., St Hillien S.A., Kalim S., Nigwekar S.U., Flood J.G., Nixon A., Simonetto D.A., Juncos L.A., Karakala N., Wadei H.M., Regner K.R., Belcher J.M., Nadim M.K., Garcia-Tsao G., Velez J.C.Q., Parikh S.M., Chung R.T., HRS-HARMONY study investigators Urinary NGAL as a diagnostic and prognostic marker for acute kidney injury in cirrhosis: a prospective study. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2021 May 11;12(5) doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000359. PMID: 33979307; PMCID: PMC8116001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/K232761.pdf

- 21.Gounden Verena, Bhatt Harshil, Jialal Ishwarlal. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Renal Function tests." StatPearls [Internet] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soto K., Coelho S., Rodrigues B., Martins H., Frade F., Lopes S., Cunha L., Papoila A.L., Devarajan P. Cystatin C as a marker of acute kidney injury in the emergency department. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010 Oct;5(10):1745–1754. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00690110. Epub 2010 Jun 24. PMID: 20576828; PMCID: PMC2974372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devarajan P. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL): a new marker of kidney disease. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. Suppl. 2008;241:89–94. doi: 10.1080/00365510802150158. PMID: 18569973; PMCID: PMC2528839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bufkin Kendra B., Karim Zubair A., Jeane Silva. Validation of plasma neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin as a biomarker for diabetes-related acute kidney injury. Sci. Prog. 2024;107(4) doi: 10.1177/00368504241288776. 00368504241288776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldstein Stuart L., et al. Derivation and validation of an optimal neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated lipocalin cutoff to predict stage 2/3 acute kidney injury (AKI) in critically ill children. Kidney. Inter. Report. 2024;9(8):2443–2452. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2024.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samara Vishnu, Song Lu, Vincent Buggs. Validation of Neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL), a urinary biomarker for Acute Kidney Injury and the positive interference from high leukocyturia samples. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2022;158:S26. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khwaja Arif. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2012;120(4):c179–c184. doi: 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.