Highlights

-

•

This study leveraged multi-dataset analysis to construct and validate an Artificial Intelligence-Derived Prognostic Index (AIDPI) for ovarian cancer, which demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting ovarian cancer prognosis compared to existing models.

-

•

Functional analysis, immunoprofiling, and the role of the MFAP4 gene were investigated to elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying the model.

-

•

In clinical samples of ovarian cancer patients, MFAP4 is highly expressed in metastatic lesions and is associated with poor prognosis. In vitro and in vivo experiments knockdown of MFAP4 reduces the metastasis of ovarian cancer cells.

Keywords: Ovarian Cancer, Prognostic model, Precision medicine, AIDPI, MFAP4, Immune microenvironment

Abstract

Background

Gynecological malignancies, particularly ovarian cancer, pose a formidable challenge to women's wellbeing, as evidenced by the global incidence and mortality rates, emphasizing the pressing need for advanced diagnostic and treatment modalities. The heterogeneity of ovarian cancer poses challenges for traditional therapeutic approaches, necessitating the exploration of novel, precision medicine techniques.

Methods

This study leveraged multi-dataset analysis to construct and validate an Artificial Intelligence-Derived Prognostic Index (AIDPI) for ovarian cancer. Transcriptome data from the TCGA, ICGC, and GEO databases were utilized, encompassing bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing. The AIDPI model was developed and refined using univariate Cox regression analysis and an ensemble of machine learning algorithms. Functional analysis, immunoprofiling, and the role of the MFAP4 gene were investigated to elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying the model.

Results

The AIDPI model demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting ovarian cancer prognosis compared to existing models. It correlated with clinical treatment outcomes, including chemotherapy responsiveness, and was integrated into a nomogram for improved prognostic stratification. Functional analysis revealed the influence of AIDPI genes on tumor immune infiltration and cell cycle regulation. Single-cell analysis exposed cell type-specific expression patterns, and the MFAP4 gene was identified as a potential therapeutic target due to its association with patient prognosis and modulation of cellular behavior. In clinical samples of ovarian cancer patients, MFAP4 is highly expressed in metastatic lesions and is associated with poor prognosis. In vitro and in vivo experiments, knockdown of MFAP4 reduces the metastasis of ovarian cancer cells.

Conclusion

The AIDPI model offers a highly accurate tool for ovarian cancer prognosis and treatment decision-making, underscored by the integration of multi-omics data and artificial intelligence. The model's performance and biological insights provide a foundation for advancing precision medicine in ovarian cancer. MFAP4′s functionality and the influence of DNA methylation present opportunities for prospective research endeavors and potential therapeutic interventions.

Background

Gynecological cancers constitute a grave hazard to women's wellbeing, as evidenced by the staggering epidemiological statistics from 2021, which indicate a global burden of approximately 1.398 million fresh diagnoses and 672,000 fatalities attributed to these malignancies[1]. The clinical treatment effect of cancer patients needs to be improved [2]. With advancements in medicine, the early diagnosis rate and five-year progression-free survival rate for gynecological malignancies have significantly improved compared to the past. This improvement in therapeutic outcomes is closely correlated with the standardization of initial diagnosis and treatment by clinicians.

Ovarian cancer emerges as the leading cause of mortality among gynecological malignancies, primarily stemming from challenges in early detection and the tendency for the disease to recur[3,4]. Characteristically impacting the ovaries and omentum, this cancer is often accompanied by severe accumulation of malignant ascites and intraperitoneal metastasis[5]. Alarmingly, an estimated 75 % of patients are diagnosed with intraperitoneal involvement initially, and for those in stage III, the five-year survival rate falls below 40 %. The early symptoms of ovarian cancer are often inconspicuous, but as the disease progresses, it often manifests as abdominal distension, abdominal pain, and frequent urination. Although surgery, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy are the primary treatment modalities, the high heterogeneity of ovarian cancer limits the effectiveness of treatment. Therefore, exploring more effective treatment options is particularly crucial. The immune checkpoint inhibitors ushered a new era in oncology and became the fifth pillar of cancer care[6], however the response rate of immune checkpoint inhibitors to ovarian cancer is very low. There is a growing emphasis on identifying reliable biomarkers to enhance risk stratification, promote more personalized treatment escalation for patients at high risk of recurrence, and facilitate treatment downgrading for patients with good prognosis[7].

As computer technology advances swiftly, artificial intelligence (AI) is progressively incorporated into medical diagnosis, assuming a pivotal role in areas such as computer tomography (CT) imaging, three-dimensional reconstruction, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cell tracking and localization. Presently, this technology has garnered significant attention in the investigative landscape of gynecological malignancies, offering robust support for early detection, precise diagnosis, and the formulation of tailored treatment strategies for the disease.

In recent years, advances in high-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics have enabled researchers to delve deeper into the molecular mechanisms and prognostic factors of ovarian cancer using gene expression data[8]. The "Artificial Intelligence-Derived Prognostic Index" (AIDPI) is a prognostic index generated leveraging artificial intelligence technology, primarily utilized for predicting the prognosis of patients with certain diseases, such as osteosarcoma[9]. The AIDPI model, as an emerging analytical tool, comprehensively considers the factors of the tumor microenvironment, providing a new perspective for uncovering the complexity of ovarian cancer[8].

Notable progress has been made in the implementation of the AIDPI within the realm of ovarian cancer research and practice. According to numerous studies and reports, AI systems have demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting the prognosis of ovarian cancer patients compared to traditional methods. Researchers from Imperial College London and the University of Melbourne have collaboratively developed an AI system named Texlab[10], which specializes in prognostic analysis of ovarian cancer and offers the most effective treatment recommendations. By extracting quantitative data from preoperative computed tomography (CT) images, this system can accurately predict the survival rates and disease progression of ovarian cancer patients at early stages[10]. Furthermore, the prediction accuracy of this system is four times that of existing medical technologies[10]. Furthermore, researchers at the Integrated Cancer Research Center have concluded another pioneering study. By integrating machine learning with blood metabolite information, they have developed a novel method that achieves a 93 % accuracy rate in detecting ovarian cancer samples. This methodology not only elevates the accuracy of diagnoses but also furnishes robust underpinnings for the prompt identification and management of ovarian cancer, thereby improving patient outcomes[11].

This study aims to construct and validate a highly accurate prognostic model (AIDPI) for ovarian cancer by selecting and verifying genes with significant prognostic roles across multiple datasets. Furthermore, it delves into the biological mechanisms underlying AIDPI and its differences at the single-cell level, evaluating its clinical application in decision-making to provide theoretical and practical guidance for precision medicine in ovarian cancer.

Method

Transcriptome data acquisition and processing

To establish the foundation for our model, we initiated by screening the RNA expression profiles along with their corresponding clinical data of 378 ovarian cancer patients sourced from the TCGA database. To ascertain the reliability and precision of our model, we utilized the OV_AU dataset (93 cases) from the ICGC database for RNA sequencing validation. The entire dataset was standardized into TPM format and subsequently subjected to log2 transformation for uniformity and analytical convenience. Additionally, we integrated multiple ovarian cancer microarray datasets from the GEO database, totaling 2140 samples, for further model validation. Normalization of the microarray data was accomplished utilizing the normalizeBetweenArrays function within the limma package, ensuring consistency across different arrays (Fig. S1). For the creation of a reference dataset for normal tissues, we sourced RNA sequencing information from 88 ovarian samples classified as normal within the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project, complemented by microarray data from 10 additional normal ovarian tissues obtained from the GSE26712 study. Concurrently, we obtained mutation and CNV information related to ovarian cancer using the TCGAbiolinks package, and conducted in-depth analysis by integrating relevant cell line expression data and CNV information from the CCLE database. Ultimately, we applied the 'Combat' method, facilitated by the 'sva' R package, to rectify batch effects across the entire spectrum of our datasets.

Collection and analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data

We procured single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets from the GEO repository, aggregating a total of 20 samples from ovarian cancer tumors. These samples were sourced from the GSE184880 series, contributing 7 samples, the GSE203612 series with 8 samples, and the GSE211956 series comprising 5 samples. The analytical procedures were executed utilizing the R statistical software, specifically version 4.1.3, and we opted for the Seurat package as our primary tool for data manipulation and analysis. This choice was instrumental in handling the complexity of single-cell transcriptomic data, enabling robust computational processing. During cell quality control, we set a mitochondrial content threshold of no >20 % and established thresholds for UMI counts and gene counts, varying according to the sample source. Data were normalized, and 2000 highly variable genes were selected. Subsequent refinements of the data encompassed adjustments to mitigate the influences of cellular cycle variations. This was achieved by employing the suite of functions provided by the Seurat package, specifically leveraging NormalizeData for data normalization, FindVariableFeatures for identifying variable genes, and ScaleData to standardize the gene expression measurements. Batch effect correction was achieved through the harmony algorithm. To reveal the inherent structure of the data, we employed UMAP and t-SNE dimensionality reduction methods, along with the Louvain clustering algorithm, all sourced from the Seurat package. Finally, differential genes between cell types and AIDPI high and low groups were identified using the FindAllMarkers function, with screening criteria set at a p-value <0.05, a log2 fold change (log2FC) greater than 0.25, and an expression proportion exceeding 0.1.

Cell annotation

Initially, we applied a panel of specific markers to identify and characterize various cell types within the samples: epithelial cells were tagged with markers such as EPCAM, KRT18, KRT19, and CDH1; fibroblasts with DCN, THY1, COL1A1, and COL1A2; endothelial cells with PECAM1, CLDN5, FLT1, and RAMP2; T cells with CD3D, CD3E, CD3G, and TRAC; NK cells with NKG7, GNLY, NCAM1, and KLRD1; B cells with CD79A, IGHM, IGHG3, and IGHA2; myeloid cells with LYZ, MARCO, CD68, and FCGR3A; and mast cells with KIT, MS4A2, and GATA2. This approach facilitated a detailed cellular annotation and understanding of the cellular landscape in the context of ovarian cancer. The scGate software was employed to determine the cell annotation results. Subsequently, the sc-type software was used for subclassification annotation of immune cells, generating various charts including UMAP, t-SNE, bar plots, and heatmaps. To predict malignant cells within epithelial cells, we conducted CNV analysis on the epithelial cells using the inferCNA software, with stromal cells (endothelial and fibroblasts) serving as the reference.

Prognostic gene selection

A single-variable Cox proportional hazards model was applied to assess the prognostic relevance of all genes within the TCGA dataset and two external GEO validation cohorts, GEO_GPL96_OV and GEO_GPL570_OV. This analysis led to the identification of 21 genes that exhibited significant prognostic value, with a consistent P-value of <0.05 across all three datasets. The remaining datasets served as validation sets for modeling the AIDPI model using these 21 prognostic genes.

Cell culture and lentivirus packaging

The cell lines 293T, ES-2, OVCA-429, SKOV3, and TOV-21 G were procured from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). A2780 cells were obtained from the National Experimental Cell Resource Sharing Platform (Beijing, China), and 3AO cells were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). 293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), SKOV3 cells in McCoy's 5A with 10 % FBS, and the rest in RPMI 1640 10 % FBS.

To generate pLKO.1-puro lentiviruses, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with packaging plasmids psPAX2, pMD2G, and lentiviral vectors. As described previously (21), lentivirus infection was performed in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines, and puromycin (2 μg/mL) (540,222, Sigma) was applied to establish the stable cellular populations. The MFAP4 shRNA sequences were as follows (5,−3,): sh1, CTGACACTGAAGCAGAAGTAT and sh2, GAATGACTACAAGCTGGGCTT.

Tissue microarray

Tissue chips from 48 patients with ovarian cancer were supplied by the Department of Gynecology Oncology, National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital. These patients underwent surgical resection from January 2010 to October 2019. Following the exclusion of 2 unsuitable samples, the remaining 46 samples were subjected to further analysis.

Western blotting

The suitably treated cells were harvested and lysed with RIPA buffer (1 % NP-40, 0.1 % sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 % sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM (EDTA), 1×proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) for 30 min on ice. The proteins were resolved by 10 % SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). Post-blocking with 5 % skim milk, the membranes underwent overnight incubation at 4 °C with anti-MFAP4 (diluted at 1:200; sc-398,438, Santa cruz) and anti-β-actin (diluted at 1:4000; Abclonal) antibodies. Subsequent visualization of the immunoblots was achieved using the ImageQuant LAS-4000 System (GE).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue microarrays were stained with anti-MFAP4 antibody (1:100; 17,661–1-AP, Protientech). The images were captured by Aperio ScanScope (Leica, Nussloch, Germany).

Transwell assays

The migration and invasion capabilities of ES2 cells were evaluated using the transwell assay. Briefly, cells (5 × 104/well) were seeded in 200 μL of serum-free medium. The lower chamber contained 600 μL of medium with 10 % FBS. Matrigel (BD Bioscience, USA) was applied to the upper compartment for the invasion assay or omitted for the migration assay. After 24 h, cells that had invaded or migrated to the lower chamber were stained with 0.1 % crystal violet and quantified. Each experiment was conducted independently in triplicate.

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Cancer Hospital. To induce metastatic growth in vivo, luciferase-labeled ES2 cells transfected with shMFAP4 or the empty vector were intraperitoneally injected into 6-weeks-old female BALB/c nude mice (1 × 106 cells/mouse). After 18 days, the luciferase signals were measured. Once the tumors had grown for the stipulated duration, the mice were euthanized and the tumors were harvested.

SNV analysis

Genomic sequencing data pertaining to single nucleotide variants (SNVs) were extracted from the TCGA repository. Subsequently, the computational maftools package was engaged to determine the tumor mutation burden (TMB) for each individual sample. Comparative analysis of TMB between distinct risk groups was executed utilizing the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, where statistical significance was defined by a p-value threshold of <0.05.

Gene differential expression and enrichment analysis

The disparity in gene expression levels between cohorts delineated by high and low Artificial Intelligence-Derived Prognostic Index (AIDPI) scores was scrutinized through the application of the limma R package, encompassing data from both the GEO and TCGA biorepositories. Gene expression was deemed to significantly differ if the associated P-value was <0.05 and the absolute value of log2 fold change exceeded 0.5. Subsequently, an enrichment analysis was conducted on these differentially expressed genes, employing the clusterProfiler R package. This analysis was powered by the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) methodology, drawing on curated gene sets from the HALLMARK and KEGG databases, as cataloged in the Molecular Signatures Database (msigdb). The enrichplot package was used for visualizing enrichment results.

Establishment of tumor-related risk signatures

A prognostic model was constructed using 101 machine learning methods, allowing for risk scores to be assigned to each patient. The application of the surv_cutpoint function facilitated the identification of a threshold that stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups within the TCGA dataset as well as in the other comparative cohorts. Subsequently, the predictive performance and model accuracy of these two groups were evaluated.

Risk signatures generated by an ensemble machine learning approach

In pursuit of crafting the AIDPI model to achieve elevated levels of precision and reliability, we amalgamated a suite of 10 distinct machine learning strategies along with a comprehensive array of 101 algorithmic permutations. This ensemble spanned a spectrum of methodologies such as the Random Survival Forest (RSF), Elastic Net (Enet), Lasso for feature selection, Ridge regression for regularization, the Stepwise Cox for model building, CoxBoost for enhancing model robustness, Cox Partial Least Squares Regression (plsRcox) for dimensionality reduction, Supervised Principal Components (SuperPC) for data transformation, Generalized Boosted Regression Models (GBM) for handling complex relationships, and Survival Support Vector Machines (survival-SVM) for classification tasks.

The process of generating the predictive signature encompassed several methodical steps: (i) the initial step involved the selection of genes that were prognostically significant, achieved by conducting a univariate Cox regression analysis across a composite of six datasets, with a particular emphasis on the TCGA-STAD dataset; (ii) the subsequent phase was dedicated to the development of predictive models, which were meticulously tuned within the TCGA-STAD cohort, utilizing a diverse set of 101 algorithmic combinations under the rigorous conditions of a leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) framework; (iii) this was followed by a phase of extensive validation, where each model was rigorously evaluated against five distinct validation datasets, denoted as the GSE datasets; (iv) finally, to ascertain the predictive efficacy of the models, the Harrell's Concordance Index (C-index) was computed for each model across all validation datasets, identifying the model with the highest average C-index as the most effective.

Tumor immune infiltration analysis

Utilizing the IOBR package coupled with the Estimate algorithm, we conducted a quantitative assessment of immune cell infiltration among patients within the TCGA dataset. This analysis culminated in the generation of heatmaps that graphically represent the varying degrees of immune cell presence within the tumor microenvironment (TME). The outputs from the Estimate algorithm facilitated the comparative analysis of the proportional distribution of stromal cells, immune cells, and tumor cells, enabling a nuanced look at how these cellular components vary among distinct risk stratifications. This approach provided a deeper understanding of the immunological landscape and its potential impact on patient prognosis.

Statistical analysis

All manipulations of data, execution of statistical evaluations, and generation of visual representations were accomplished through the R programming environment, specifically version 4.1.3. The relationships between paired continuous variables were gauged by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients. For categorical variables, the Chi-square test was the method of choice for comparison. In contrast, the assessment of continuous variables was carried out using either the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or the T-test, depending on the data distribution. The survminer package was engaged to pinpoint the most effective cut-off points for variable stratification. Furthermore, survival analysis was performed via Cox proportional hazards regression and Kaplan-Meier estimator, facilitated by the survival package in R.

Result

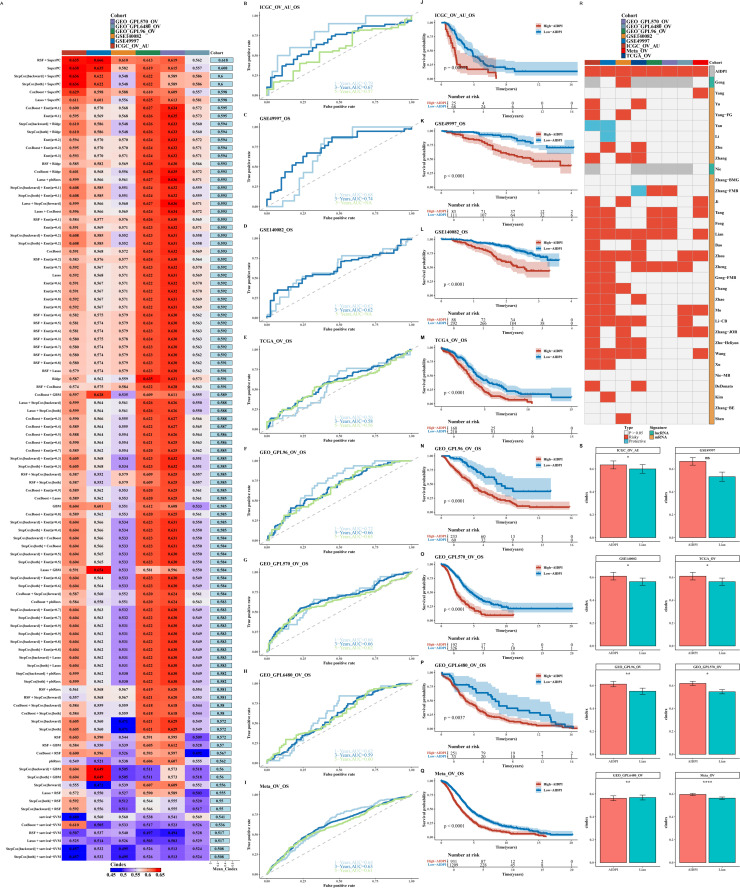

Construction and comparison of the AIDPI model

In our research, we executed a univariate Cox regression analysis across the complete spectrum of genes present within the TCGA database alongside two GEO validation cohorts, GEO_GPL96_OV and GEO_GPL570_OV. This comprehensive analysis culminated in the identification and selection of 21 genes that were significantly associated with prognosis, as indicated by a P-value threshold of <0.05. These genes were then utilized to construct the AIDPI model, which was evaluated using 101 algorithms based on the C-index, with the RSF+SuperPC algorithm combination demonstrating the optimal performance (as shown in Fig. 1A). The model consistently indicated a poorer prognosis for the high AIDPI group across various datasets through timeROC and survival analyses (as depicted in Figs. 1B–Q). Comparative analysis with 32 recently published ovarian cancer prognostic models revealed the superiority of our model (as illustrated in Fig. 1R and 1S).

Fig. 1.

Construction and Comparison of the AIDPI Model.

A. Heatmap displays C-index of 101 models across datasets, red=high, blue=low. B-Q. ROC curves & survival analysis for 1, 3, 5 years per dataset. R. Heatmap highlights AIDPI vs. 32 models. S. Bar chart compares AIDPI's C-index to top model in each dataset.

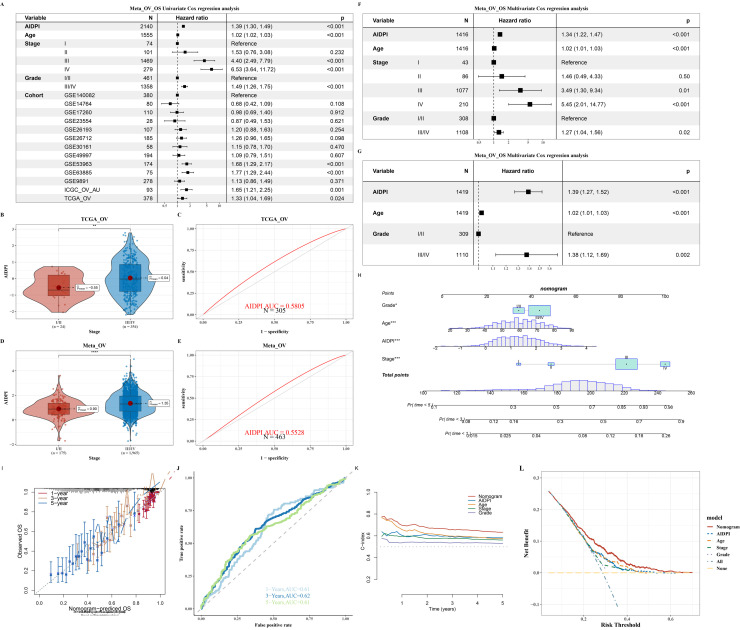

Cox analysis and nomogram construction of AIDPI in relation to clinical treatment

A dedicated Cox proportional hazards analysis was conducted, incorporating the Artificial Intelligence-Derived Prognostic Index (AIDPI) alongside a spectrum of clinical parameters—encompassing Age, Stage, Grade, and Cohort—which were graphically represented in Fig. 2A. This analysis aimed to gauge the predictive capacity of the AIDPI in chemotherapy responsiveness (Fig. S2). The discriminatory power of the AIDPI was further quantified using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), and a comparative analysis was performed to discern differences between chemotherapy responders and non-responders, as depicted in Figs. 2B through 2E. A comprehensive multivariate Cox regression analysis underscored the profound influence that the clinical Stage exerts on patient prognosis, a finding visually articulated in Figs. 2F–G. Advancing further, a predictive nomogram was meticulously crafted, integrating critical parameters such as the Artificial Intelligence-Derived Prognostic Index (AIDPI), patient Age, Stage, and Grade, as delineated in Fig. 2H To substantiate the nomogram's predictive efficacy, calibration plots and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were meticulously computed at the 1, 3, and 5-year milestones, as exhibited in Figs. 2I and 2J. These analyses collectively substantiated the nomogram's remarkable precision in prognostic estimation. Additionally, the pec package was employed to analyze the temporal dynamics of the C-index for each predictive marker, thereby affirming the sustained high predictive accuracy of the nomogram as depicted in Fig. 2K. This temporal analysis, coupled with the validation of the model's clinical applicability through Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) as illustrated in Fig. 2L, collectively reinforces the robustness and practicality of the predictive framework in real-world settings.

Fig. 2.

Cox Analysis and Nomogram Construction of AIDPI in Relation to Clinical Treatment.

A. Forest plot of univariate Cox analysis for AIDPI, Age, Stage, Grade, and Cohort in the Meta_OV dataset. B-E. Prediction results for chemotherapy response in the TCGA_OV and Meta_OV datasets. F. Multivariate Cox analysis reveals impact of AIDPI, Age, Stage, Grade, & Cohort. G. Similar analysis excluding Stage. H-L. Tools for clinical prediction: Nomogram, calibration, timeROC, time-Cindex, & DCA analyses.

Functional analysis of AIDPI model genes

The expression differences of 13 AIDPI model genes between groups were calculated, and their immune scores were presented (as shown in Fig. 3A). We leveraged the limma software to pinpoint differentially expressed genes between the groups, subsequently employing the GSEA algorithm to conduct a comprehensive functional analysis (as depicted in Fig. 3B). The ORA algorithm was employed for functional enrichment against the KEGG database, along with functional network analysis (as shown in Figs. 3C–D). Although no significant differences in average methylation levels were found between groups using methylation data (as shown in Fig. 3E), the ebGSEA analysis yielded the top 10 functional analysis results (as shown in Fig. 3F). We further analyzed the Tumor Mutation Burden (TMB) between two groups within the TCGA_OV dataset, and the results showed that the mutation change between the two groups was not obvious (Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

Functional Analysis of AIDPI Model Genes.

A. Heatmap of expression differences in 13 AIDPI model genes between two groups. Red represents the high expression group of AIDPI model genes, and blue represents the low expression group. B. GSEA enrichment plot (bar plot) for differentially expressed genes between groups. C-D. Bubble and network plots for differential gene expression identified by ORA analysis. E. Violin plot of average methylation differences between groups. Red represents the high expression group of AIDPI model genes, and blue represents the low expression group. F. Bar chart of ebGSEA analysis results for methylation data between groups.

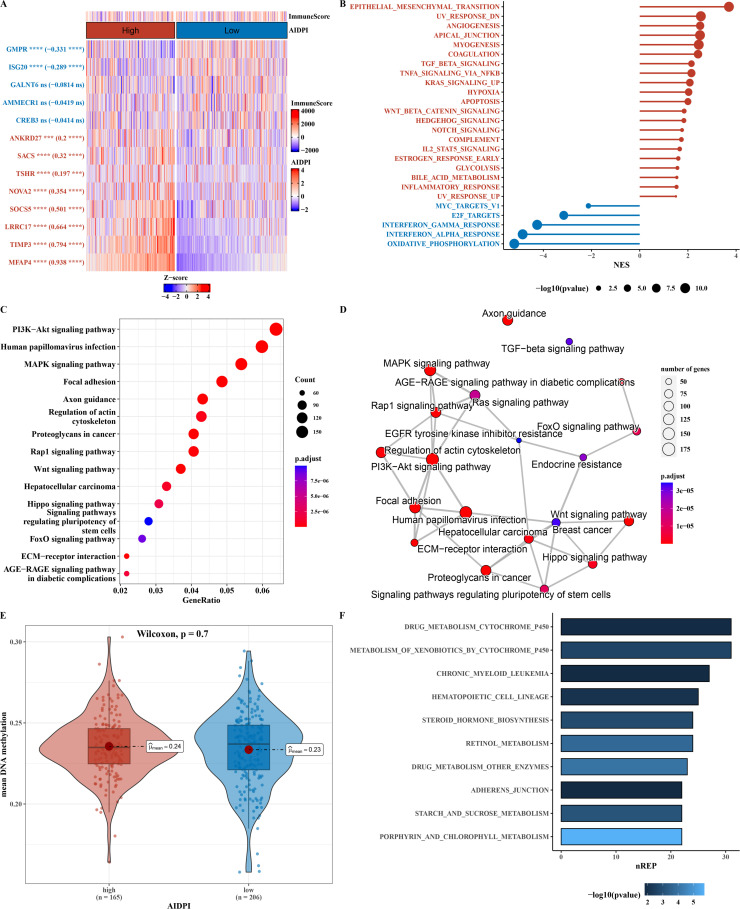

Single-Cell analysis of ovarian cancer

Utilizing the infercna software, we predicted the presence of malignant cells amidst epithelial cells, with stromal cells serving as a benchmark for comparison (as illustrated in Fig. S4 and Fig. 4A). Cell type annotation was achieved using the scGate and sc-type software in conjunction (as shown in Fig. 4B). Markers for each cell type were displayed using bubble and volcano plots (as shown in Figs. 4C–D). The AUCell software was employed to assign scores to the 13 genes comprising the AIDPI model, enabling the distinction between cells belonging to the high AIDPI group and those in the low AIDPI group. Subsequently, differences among these groups were meticulously analyzed and categorized (as exemplified in Fig. 4E). Utilizing markers for distinct cell types, as well as identifiers for cells belonging to the high and low AIDPI groups, along with the 13 genes that constitute the AIDPI model (visualized in Fig. 4F), we pinpointed three overlapping genes. Subsequently, we illustrated the expression patterns of these genes within the context of single-cell data (displayed in Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4.

Single-Cell Analysis Results of Ovarian Cancer.

A. CNV heatmap predicted by infercna software. B. tSNE plot of cell annotation in single-cell data. C. Bubble plot of markers for various cell types. D. Volcano plot of markers for various cell types. E. Pie chart of markers for high and low AIDPI group cells. F. Venn diagram of cell type markers, markers for high and low AIDPI group cells, and 13 AIDPI model genes. G. tSNE plot showing the expression patterns of three intersecting genes in single-cell data.

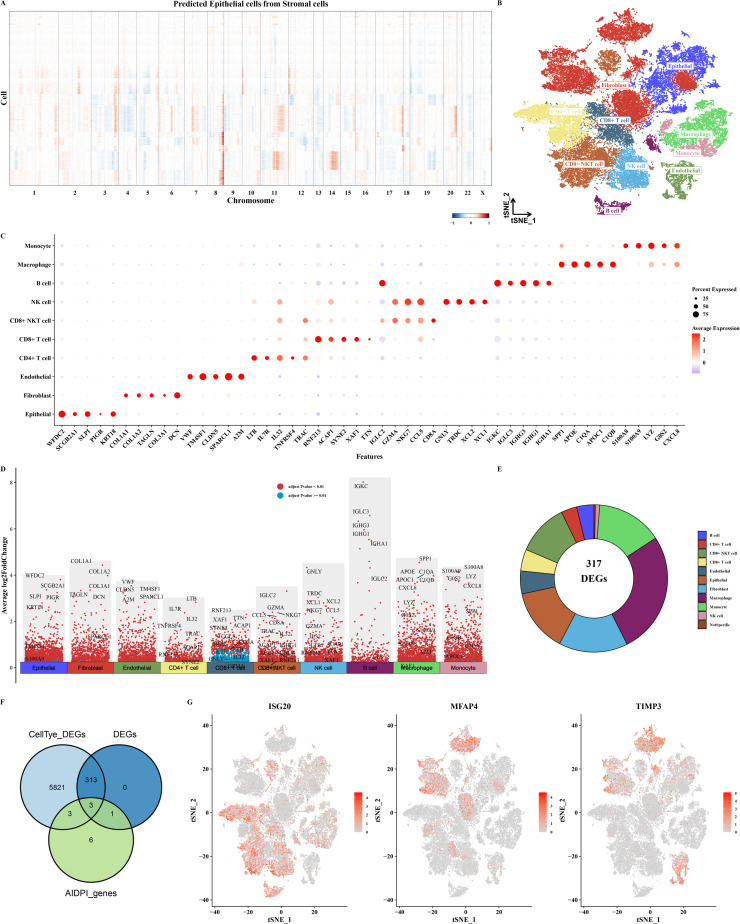

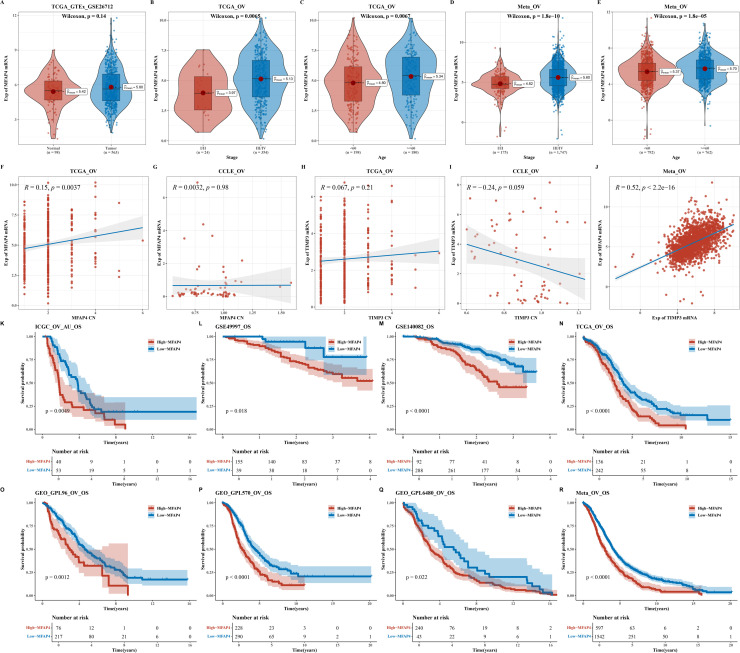

In-depth study of the MFAP4 gene

In light of the pivotal role played by the MFAP4 gene and its pronounced disparities in copy number between the high and low AIDPI groups, we embarked on a series of rigorous analytical endeavors. Initially, we presented the expression disparities of MFAP4 between normal and tumor samples (as illustrated in Fig. 5A). Subsequently, we observed notable differences in expression levels that correlated with Stage and Age across the TCGA-OV and Meta-OV datasets, with elevated expression levels detected in groups characterized by advanced Stage and older Age (as depicted in Figs. 5B–E). We conducted an analysis to explore the relationship between the expression levels and copy numbers of the MFAP4 and TIMP3 genes within the TCGA dataset and CCLE cell lines (as shown in Fig. S5 and Figs. 5F–I). Additionally, we examined the expression correlation between these two genes (as depicted in Fig. 5J). Survival analyses of the MFAP4 gene across various datasets indicated that higher MFAP4 expression is associated with a poorer prognosis (as shown in Figs. 5K–R).

Fig. 5.

Research Results of the MFAP4 Gene.

A. Violin plot of MFAP4 gene expression differences between normal and tumor samples. B-E. Violin plots of MFAP4 gene expression differences in relation to Stage and Age in the TCGA-OV and Meta-OV datasets. F-I. Scatter plots showing the correlation between expression levels and copy numbers of the MFAP4 and TIMP3 genes in the TCGA dataset and CCLE cell lines. J. Scatter plot of the expression correlation between the two genes. K-R. Survival analysis results for the MFAP4 gene across various datasets.

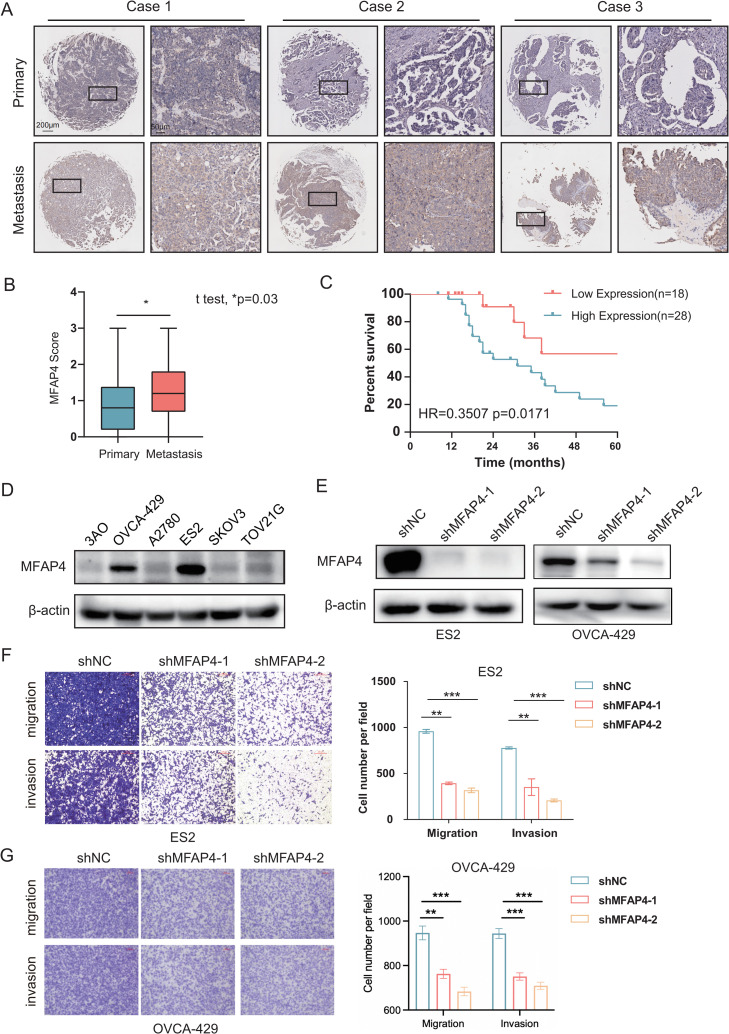

MFAP4 expression correlates with poor prognosis and modulates ovarian cancer cell behavior

To delve into the expression pattern of MFAP4 within tumor tissues, we initiated our investigation by applying immunohistochemistry to three ovarian cancer cases, as exemplified in Fig. 6A. Upon scrutinizing survival outcomes among ovarian cancer patients stratified by their MFAP4 protein expression levels, we discerned a striking association: patients with heightened MFAP4 expression exhibited a notably decreased survival rate, as validated through a Log-rank test (*p = 0.03) and further substantiated by a Hazard Ratio analysis (HR=0.3507, p = 0.0171), with these findings vividly portrayed in Figs. 6B and 6C. Moreover, to substantiate our observations, we employed Western blot analysis, which confirmed the upregulated expression of MFAP4 in ovarian cancer cell lines, specifically OVCA-429 and ES2 (as demonstrated in Fig. 6D). Of paramount importance, our investigation revealed that when the MFAP4 gene was effectively silenced using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) technology, a marked decrease was observed in the migratory and invasive capabilities of the ovarian cancer cell line ES2 and OVCA-429. Specifically, compared to the shControl group, both the shMFAP4–1 and shMFAP4–2 groups exhibited significantly reduced migration and invasion rates (*p < 0.05), as clearly demonstrated in Figs. 6E–G. Moreover, we found that no significant changes in apoptosis of ES2 cells were observed among shNC, shMFAP4–1 and shMFAP4–2 groups (displayed in Fig. S6A and S6B). By CCK-8 assay, we found that MFAP4 knockdown can restrain cell proliferation (as shown in Fig. S6C). Notably, there were no significant changes in proliferation of ES2 cells at 24 h among shNC, shMFAP4–1 and shMFAP4–2 groups (as shown in Fig. S6C). For transwell experiments, 24 h after seeding the cells, cells that had invaded or migrated to the lower chamber were stained with 0.1 % crystal violet and quantified, indicating that proliferation of ES2 cells does not effect the results of transwell assays to evaluate the invasion and migration ability. These results indicate that knocking down MFAP4 can indeed inhibit the migration and invasion abilities.

Fig. 6.

Comprehensive Analysis of MFAP4 Expression and Functionality in Ovarian Cancer.

A. Immunohistochemical examination of MFAP4 protein levels in a cohort of 46 paired primary and metastatic ovarian (OV) cancer tissues, illustrating differential expression patterns. B. Comparative gene expression analysis of MFAP4 between primary and metastatic sites within microarrays, derived from data of 46 patients with ovarian cancer, revealing expression disparities. C. Survival analysis for the 46 ovarian cancer patients, correlating MFAP4 expression levels with patient outcomes. D. Immunoblot analysis of MFAP4 protein expression across six commonly studied ovarian cancer cell lines, normalizing to β-actin as a loading control. E. Immunoblot detection of MFAP4 protein levels in ES2 and OVCA-429 cells following the knockdown of the MFAP4 gene, showcasing the efficiency of shRNA-mediated gene silencing. F. Transwell invasion assays quantifying the impact of MFAP4 knockdown on the invasiveness of ES2 cells, with a scale bar indicating 100 μm. The accompanying statistical analysis of the Transwell data is depicted on the right. Data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation; t-test was used for statistical comparison, with **indicating p < 0.01; experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3). G. Transwell invasion assays quantifying the impact of MFAP4 knockdown on the invasiveness of OVCA-429 cells. The accompanying statistical analysis of the Transwell data is depicted on the right. Data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation; t-test was used for statistical comparison, with **indicating p < 0.01, ***indicating p < 0.001; experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3).

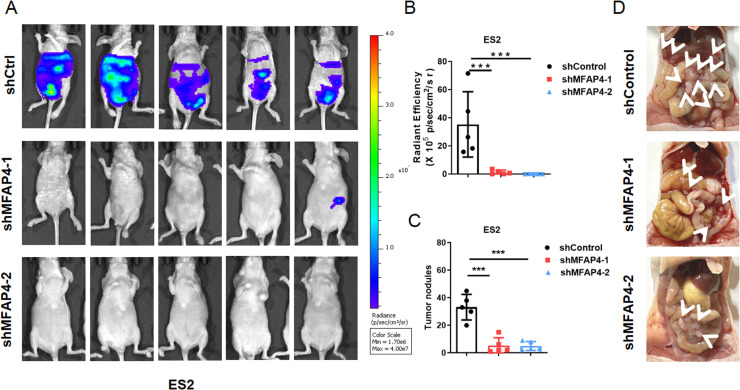

We also established an in vivo metastasis model of ovarian cancer by intraperitoneally injecting luciferase-labeled control or shMFAP4 ES2 cells into BALB/c nude mice. As shown in Fig. 7A, mice injected with the control cells showed stronger luciferase signal 18 days after inoculation, which indicated that MFAP4 silencing weakened the metastatic ability of the ES2 in vivo. The same results were also visually displayed in fluorescence intensity analysis and tumor quantity analysis (as demonstrated in Fig. 7B–C). We also presented an anatomical diagram of a mouse peritoneal metastasis model, where the white arrow represents the tumor (as shown in Figs. 7D). After knocking down MFAP4, the number of tumors significantly decreased.

Fig. 7.

Validation of the effects of MFAP4 in vivo experiments. A. Fluorescence intensity analysis of abdominal metastasis model constructed after knocking down MFAP4 in ES2. B-C. Statistical chart of fluorescence intensity tumor formation quantity. The data are presented as the means ± SEM; two-tailed t-test, ***p < 0.001; n = 5. D.Visual display of mouse abdominal anatomy, with tumor location marked with white arrows.

Discussion

Through multi-dataset analysis, this study successfully constructed and validated a highly accurate ovarian cancer prognostic model (AIDPI), delving into its biological mechanisms and differences at the single-cell level. The findings not only provide a theoretical basis and practical guidance for precision medicine in ovarian cancer but also underscore the potential of artificial intelligence in enhancing the accuracy of disease prognosis prediction.

Firstly, the AIDPI model's foundation was firmly established upon extensive transcriptomic data[9,11,12], which served as the cornerstone for identifying genes that exhibited a statistically significant correlation with ovarian cancer prognosis, a process facilitated by univariate Cox regression analysis. The robustness and versatility of the model were rigorously validated through extensive testing across multiple independent datasets, underscoring its ability to generalize across different data sources. Notably, we found that the AIDPI model exhibits significant advantages in prediction accuracy compared to existing models, which was corroborated in a comparison with 32 other ovarian cancer prognosis models.

The timely diagnosis and accurate prognostic prediction of ovarian cancer remains challenging due to the absence of reliable biomarkers[13]. Intra-tumoral heterogeneity of ovarian cancer led to the importance of identifying subpopulations of cells with critical roles in prognosis and drug resistance[14]. Integrating multi-omics data into prognostic models has proven essential for improving their resolution and specificity[[15], [16], [17]]. Moreover, the lack of a dataset for external validation and mechanistic interpretations limited the translational potential of many AI-based models with high predictive accuracy[18]. In our studies, we are addressing this gap by leveraging multi-modal data integration approaches using advanced machine learning algorithms, as demonstrated in the development of the AIDPI model. This approach allows for a more holistic view of tumor progression and immune microenvironment interactions.

Secondly, the correlation analysis between AIDPI and clinical treatment revealed its potential in assessing chemotherapy responsiveness. Through univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, we found that AIDPI serves as an independent prognostic factor and, when combined with traditional clinical features such as stage, age, and grade, can construct a nomogram to provide more precise prognostic information for clinical decision-making. This discovery underscores the possibility of integrating AIDPI into existing clinical assessment systems, facilitating individualized treatment. Survival prediction models based on both AIDPI and clinical characteristics have demonstrated superiority. For instance, combining AIDPI with age, MSTS stage, Huvos grade, and primary tumor site significantly improves the prediction accuracy of survival probabilities in patients with osteosarcoma (OSA)[9]. Furthermore, this combined approach validates its effectiveness as a prognostic prediction tool.

Furthermore, the functional analysis of genes in the AIDPI model provides biological insights for this study. Employing sophisticated tools like GSEA and ORA, we delved into the functional enrichment of differential genes, unveiling the pivotal roles played by AIDPI-associated genes in intricate biological processes, including tumor immune infiltration and cell cycle regulation. GSEA is a powerful tool for assessing whether the expression pattern of a set of genes in overall gene expression data is associated with known biological processes. This approach considers not only the expression levels of individual genes but also the interactions and network structures among them[19]. ORA, on the other hand, is another commonly used bioinformatics method for detecting the enrichment of specific categories (e.g., GO terms or KEGG pathways) within a gene set[19]. This method can help identify which biological processes or pathways are particularly activated or inhibited in the studied gene set. At the single-cell level, our analysis revealed expression differences of AIDPI model genes across various cell types and identified key genes through intersection analysis of cell type markers. These groundbreaking discoveries not only deepen our comprehension of the intricate molecular mechanisms underlying ovarian cancer but also pave the way for the identification of novel therapeutic targets, offering promising avenues for future treatment strategies.

The MFAP4 gene emerges as a pivotal player in the context of ovarian cancer, warranting meticulous scrutiny. Our meticulous research endeavors have unearthed a compelling correlation between MFAP4 expression and the clinical outcomes of ovarian cancer patients, further validated by our cellular-level investigations, which conclusively demonstrate its influence on the migratory and invasive potential of cancer cells. Elevated MFAP4 expression in patients with serous ovarian cancer (SOC) is linked to reduced recurrence-free and overall survival, positioning it as a potential biomarker for predicting response to platinum-based chemotherapy and survival outcomes in SOC[20]. The MFAP4 gene is highly expressed in ovarian cancer patients belonging to the high-risk group[21] and is significantly associated with poor progression-free survival[22].

Moreover, antibodies specifically targeting MFAP4, designed to disrupt its interactions with integrin receptors, may hold significant potential in regulating cellular growth and preventing the development of abnormal tissue layers, such as intimal hyperplasia[23,24]. While this groundbreaking finding initially garnered attention within the realm of vascular disorders, its relevance extends to the cellular migration and invasion mechanisms we have observed in ovarian cancer. Intriguingly, in the context of lung adenocarcinoma, a paradoxical scenario arises: low MFAP4 expression is predictive of an adverse prognosis. Furthermore, the expression patterns of MFAP4 are intricately linked to immune cell infiltration, exhibiting a positive correlation with M2-type macrophages and a negative association with M1-type macrophages[25,26]. This suggests that MFAP4 is not only involved in the biological behavior of tumor cells but may also influence tumor progression by affecting the immune microenvironment. However, a contrasting body of evidence suggests that MFAP4 expression is often downregulated in a majority of human cancers. Notably, in the case of breast cancer, a heightened mRNA expression of MFAP4 is notably associated with more favorable overall survival rates, underscoring the complex and context-dependent nature of MFAP4′s role in cancer biology.

The impact of DNA methylation of the MFAP4 gene on its mRNA expression is primarily mediated through alterations in transcriptional activity and stability. DNA methylation, an epigenetic modification process, entails the attachment of a methyl group to cytosine residues within the DNA structure, a phenomenon that is commonly associated with the repression or silencing of gene expression. In the case of MFAP4, hypermethylation in its promoter region may prevent transcription factors from binding, thereby inhibiting the transcription of MFAP4 mRNA[27,28]. Additionally, changes in DNA methylation patterns may affect the stability and translational efficiency of MFAP4 mRNA; certain methylation patterns may promote mRNA degradation or alter its binding to ribosomes, thus affecting protein synthesis. These mechanisms could explain the differential expression of MFAP4 in various cancers and its complex role in tumor progression[27].

MFAP4 is a protein expressed in a variety of tumors and is believed to promote tumor progression by modulating the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME). Although the specific mechanisms of action of MFAP4 are not explicitly detailed in the current literature, based on existing research findings on TIME and tumor progression, we can infer potential pathways through which MFAP4 may exert its effects. The tumor immune microenvironment represents a intricate and dynamic system, comprising a diverse array of components, including tumor cells, immune cells, and cytokines, that engage in intricate interactions and influence the progression and response to cancer [29]. The intricate interplay among these diverse elements plays a decisive role in shaping the trajectory and intensity of the anti-tumor immune response. As a tumor-associated protein, MFAP4 may influence one or more of these components within TIME. More specifically, MFAP4 may play a pivotal role in the recruitment or activation of immunosuppressive cells, notably regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), ultimately dampening the efficacy of the anti-tumor immune response. Furthermore, metabolic changes associated with obesity have been shown to exacerbate the immunosuppressive state within TIME and diminish the tumoricidal activity of CD8+ T cells[30]. MFAP4′s potential involvement in metabolic pathways could exacerbate the establishment of an immunosuppressive microenvironment, thereby fostering conditions favorable for tumor growth and metastasis. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), in particular, occupy a central position in orchestrating the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME)[31]. MFAP4 may modulate the phenotype and function of CAFs, altering their ability to recruit and activate immune cells, thereby regulating immune responses in a temporal and spatial manner to support tumor growth. While direct evidence of how MFAP4 specifically modulates the immune microenvironment is lacking, the current literature suggests that MFAP4 may influence the function and distribution of immune cells through various mechanisms, thereby promoting tumor progression. To fully comprehend the intricate mechanisms by which MFAP4 exerts its influence within the tumor immune microenvironment, further research endeavors are imperative. Such insights will serve as the cornerstone for the development of novel therapeutic strategies, underscoring the potential of MFAP4 as a promising therapeutic target. This discovery opens up exciting avenues for future drug development and innovative treatment approaches.

At the same time, we verified the role of MFAP4 gene in ovarian cancer in cell and animal experiments. We believe that MFAP4 may affect the metastasis of ovarian cancer cells. Metastasis is an important process of cancer progression. From a molecular point of view, homing of cancer cells to the bone represents a key concept and following epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), cancer cells acquire the capacity of departing from the primary site, thus emptying into blood circulation[32]. Given that metastasis in vivo is a multi-stage process involving tumor cell detachment from primary lesions, subsequent infiltration and colonization of distal tissues. This complex cascade encompasses various cellular capabilities such as anoikis resistance in circulation, endothelial adhesion and extravasation, immune evasion, establishment of pre-metastatic niches, and colonization at distant sites[33,34]. While our intraperitoneal metastasis model revealed that MFAP4 knockdown attenuates metastatic potential, further investigation is required to determine whether the attenuated metastatic potential occurs through other mechanisms in the metastatic cascade, such as mesothelial seeding and anoikis. The specific mechanism of tumor metastasis will be explored in the next study.

Lastly, the findings of this study emphasize the crucial role of artificial intelligence technology in medical diagnosis and treatment decision-making. With advancements in computer technology and bioinformatics[35,36], AI systems such as Texlab and machine learning-based approaches have demonstrated immense potential in the prognostic analysis and diagnosis of ovarian cancer[[37], [38], [39]]. The application of these technologies not only enhances diagnostic accuracy but also enables early detection and intervention, potentially leading to significant improvements in patient treatment outcomes.

Conclusion

In essence, our study underscores the AIDPI model's efficacy as a robust prognostic instrument, empowering more refined and accurate predictions of ovarian cancer patient outcomes. By fusing multi-omics data and harnessing the power of artificial intelligence, we have not only refined the model's predictive prowess but also illuminated the intricate molecular pathways that underpin ovarian cancer, deepening our comprehension of this complex disease. Furthermore, the discovery of the MFAP4 gene presents a new therapeutic target for future treatments, while the application of artificial intelligence technology opens new avenues for medical diagnosis and treatment decision-making. With continuous technological advancements and deeper applications, we anticipate that the AIDPI model and related technologies will play an even greater role in precision medicine for ovarian cancer.

Supplementary materials

Fig. S1: A. PCA plots before and after sva normalization of expression data from the GEO_GPL96_OV dataset. B. PCA plots before and after sva normalization of expression data from the GEO_GPL6480_OV dataset. C. PCA plots before and after sva normalization of expression data from the GEO_GPL570_OV dataset. D. Venn diagram of genes associated with survival across the GEO_GPL96_OV, GEO_GPL570_OV, and TCGA datasets. E. Bar chart of feature scores for the optimal model RSP+SuperPC. F. Model diagram using the surv_cutpoint function to determine the optimal cutoff point. G. PCA plots before and after sva normalization of expression data for all datasets, including TCGA, GEO, and ICGC. H. Survival analysis results for all datasets, including TCGA, GEO, and ICGC.

Fig. S2: A. Violin plots depicting the differences in AIDPI values associated with patient Grade, Age, and response to chemotherapy. B. Forest plot illustrating the differential Cox analysis of AIDPI values in relation to Grade, Age, and chemotherapy response.

Fig. S3: A. Violin plot showing the differences in Tumor Mutation Burden (TMB) between two groups within the TCGA_OV dataset. B. Forest plot representing the pathways of mutated genes that differ significantly between the two groups. C. Violin plot of the copy number variation in 13 AIDPI model genes between the two groups. D. Violin plot of the differences in cellular composition predicted by the EpiDISH software through methylation data between the two groups.

Fig. S4: A. tSNE plot using the scGate software with the UCell method to calculate epithelial, stromal, immune, and lymphocyte scores. B. tSNE plot using the scGate software to predict immune and non-immune cells based on CD45 positivity. C. Scatter plot of CNV signals and CNV-related predictions by the infercna software using stromal cells as a reference to distinguish normal from malignant epithelial cells. d-E. CNV heatmaps of reference stromal cells and predicted normal epithelial cells, respectively. F. tSNE plot of cell clustering analysis with a resolution of 0.8. G-I. Violin plots showing the expression of epithelial marker (EPCAM), endothelial marker (RAMP2), and fibroblast marker (DCN) across different clusters. J. tSNE plot with cells colored by patient-specific cell types.

Fig. S5: A. Box plot showing MFAP4 CNV variations across CCLE cell lines. B. Expression levels of MFAP4 across CCLE cell lines. C. Scatter plot correlating EpiDISH-predicted cellular composition with MFAP4 expression.

Fig. S6: A,B. The apoptosis rates of ES2 cells following the knockdown of the MFAP4 gene were analysed by the Annexin-V-FITC and PI double-staining method through flow cytometry, n = 3. C. Measurement of ES2 cell proliferation following the knockdown of the MFAP4 gene were analysed by CCK-8 assay, n = 3. The data are presented as the means ± SD; two-tailed t-test, *** p < 0.001.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

You Wu: Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Kunyu Wang: Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yan Song: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources. Bin Li: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that the research has no Conflict of Interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Capital Health Development Research Project(2020–2–4024).

The special research fund for central universities, peking union medical college(3332023025).

National Natural Science Foundation of China (82272726).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Mice were purchased from specific pathogen free (SPF) Vital River (Beijing, China). All animal experiments in this study were performed under guidelines evaluated and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Cancer Hospital.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Cancer Center / Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and Peking Union Medical College (Beijing, China).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2025.102439.

Contributor Information

Yan Song, Email: songyan@cicams.ac.cn.

Bin Li, Email: libin@cicams.ac.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzo A., Santoni M., Mollica V., Logullo F., Rosellini M., Marchetti A., et al. Peripheral neuropathy and headache in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy and immuno-oncology combinations: the MOUSEION-02 study. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2021;17:1455–1466. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2021.2029405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Havrilesky L.J., Broadwater G., Davis D.M., Nolte K.C., Barnett J.C., Myers E.R., et al. Determination of quality of life-related utilities for health states relevant to ovarian cancer diagnosis and treatment. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009;113:216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rojas V., Hirshfield K.M., Ganesan S., Rodriguez-Rodriguez L. Molecular characterization of epithelial ovarian cancer: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016 doi: 10.3390/ijms17122113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart C., Ralyea C., Lockwood S. Ovarian cancer: an integrated review. Semin Oncol. Nurs. 2019;35:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guven D.C., Erul E., Kaygusuz Y., Akagunduz B., Kilickap S., De Luca R., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hearing loss: a systematic review and analysis of individual patient data. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31:624. doi: 10.1007/s00520-023-08083-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahin T.K., Ayasun R., Rizzo A., Guven D.C. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio (NER) in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2024:16. doi: 10.3390/cancers16213689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanauer D., Rhodes D., Sinha-Kumar C., Chinnaiyan A. Bioinformatics approaches in the study of cancer. Curr. Mol. Med. 2007;7:133–141. doi: 10.2174/156652407779940431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y., Ma X., Xu E., Huang Z., Yang C., Zhu K., et al. Identifying squalene epoxidase as a metabolic vulnerability in high-risk osteosarcoma using an artificial intelligence-derived prognostic index. Clin. Transl. Med. 2024;14 doi: 10.1002/ctm2.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu H., Arshad M., Thornton A., Avesani G., Cunnea P., Curry E., et al. A mathematical-descriptor of tumor-mesoscopic-structure from computed-tomography images annotates prognostic- and molecular-phenotypes of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2019;10 doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08718-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ban D., Housley S.N., Matyunina L.V., McDonald L.D., Bae-Jump V.L., Benigno B.B., et al. A personalized probabilistic approach to ovarian cancer diagnostics. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024;182:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2023.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang R., Liu Z., Wang L., Wang W., Zhu R., Li J., et al. Comprehensive machine-learning survival framework develops a consensus model in large-scale multicenter cohorts for pancreatic cancer. eLife. 2022:11. doi: 10.7554/eLife.80150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai G., Huang F., Gao Y., Li X., Chi J., Xie J., et al. Artificial intelligence-based models enabling accurate diagnosis of ovarian cancer using laboratory tests in China: a multicentre, retrospective cohort study. Lancet Digit Health. 2024;6:e176–e186. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(23)00245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunnea P., Curry E.W., Christie E.L., Nixon K., Kwok C.H., Pandey A., et al. Spatial and temporal intra-tumoral heterogeneity in advanced HGSOC: implications for surgical and clinical outcomes. Cell Rep. Med. 2023;4 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takamatsu S., Hillman R.T., Yoshihara K., Baba T., Shimada M., Yoshida H., et al. Molecular classification of ovarian high-grade serous/endometrioid carcinomas through multi-omics analysis: JGOG3025-TR2 study. Br. J. Cancer. 2024;131:1340–1349. doi: 10.1038/s41416-024-02837-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatamikia S., Nougaret S., Panico C., Avesani G., Nero C., Boldrini L., et al. Ovarian cancer beyond imaging: integration of AI and multiomics biomarkers. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2023;7:50. doi: 10.1186/s41747-023-00364-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang J., Chen Z., Wang H., Wang Y., Zheng J., Guo Y., et al. Screening and identification of a prognostic model of ovarian cancer by combination of transcriptomic and proteomic data. Biomolecules. 2023;13 doi: 10.3390/biom13040685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akazawa M., Hashimoto K. Artificial intelligence in gynecologic cancers: current status and future challenges - A systematic review. Artif Intell Med. 2021;120 doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2021.102164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu R.-K., Zhang W., Zhang Y.-X., hui Z., Wang X.-W. A pan-cancer analysis to determine the prognostic analysis and immune infiltration of HSPA5. Curr. Cancer Drug. Targets. 2024;24:14–27. doi: 10.2174/1568009623666230508111721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao H., Sun Q., Li L., Zhou J., Zhang C., Hu T., et al. High expression levels of AGGF1 and MFAP4 predict primary platinum-based chemoresistance and are associated with adverse prognosis in patients with serous ovarian cancer. J. Cancer. 2019;10:397–407. doi: 10.7150/jca.28127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan H., Yu Q., Pang J., Chen Y., Sheng M., Tang W. The value of the stemness index in ovarian cancer prognosis. Genes (Basel) 2022;13 doi: 10.3390/genes13060993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang P.-Y., Liao Y.-P., Wang H.-C., Chen Y.-C., Huang R.-L., Wang Y.-C., et al. An epigenetic signature of adhesion molecules predicts poor prognosis of ovarian cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:53432–53449. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soerensen G.L., Schlosser A., Holmskov U. Anticorps liant mfap4 qui bloquent l'interaction entre mfap4 et les récepteurs d'intégrine, 2014.

- 24.Schlosser A., Pilecki B., Hemstra L.E., Kejling K., Kristmannsdottir G.B., Wulf-Johansson H., et al. MFAP4 Promotes vascular smooth muscle migration, proliferation and accelerates neointima formation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016;36:122–133. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohammadi A., Sorensen G.L., Pilecki B. MFAP4-Mediated effects in elastic Fiber homeostasis, integrin signaling and cancer, and its role in teleost fish. Cells. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/cells11132115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y., Li Q., Hu R., Li R., Yang Y. Five immune-related genes as diagnostic markers for endometriosis and their correlation with immune infiltration. Front. Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1011742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z. Multiple mechanisms of DNA methylation in cancer initiation and development. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2020;512 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haertle L., El Hajj N., Dittrich M., Müller T., Nanda I., Lehnen H., et al. Epigenetic signatures of gestational diabetes mellitus on cord blood methylation. Clin. Epigenet. 2017;9 doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lv B., Wang Y., Ma D., Cheng W., Liu J., Yong T., et al. Immunotherapy: reshape the tumor immune microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.844142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang H., Wu Y., Chen L., Cao Z., Deng Z., Zhao R., et al. Regulating the obesity-related tumor microenvironment to improve cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2023;17:4748–4763. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c11159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desbois M., Wang Y. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: key players in shaping the tumor immune microenvironment. Immunol. Rev. 2021;302:241–258. doi: 10.1111/imr.12982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mollica V., Rizzo A., Rosellini M., Marchetti A., Ricci A.D., Cimadamore A., et al. Bone targeting agents in patients with metastatic prostate cancer: state of the art. Cancers. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/cancers13030546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganesh K., Massague J. Targeting metastatic cancer. Nat. Med. 2021;27:34–44. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01195-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swanton C., Bernard E., Abbosh C., Andre F., Auwerx J., Balmain A., et al. Embracing cancer complexity: hallmarks of systemic disease. Cell. 2024;187:1589–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rakha E.A., Toss M., Shiino S., Gamble P., Jaroensri R., Mermel C.H., et al. Current and future applications of artificial intelligence in pathology: a clinical perspective. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021;74:409–414. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hunter B., Hindocha S., Lee R.W. The role of artificial intelligence in early cancer diagnosis. Cancers. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/cancers14061524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y., Lin W., Zhuang X., Wang X., He Y., Li L., et al. Advances in artificial intelligence for the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer (Review) Oncol. Rep. 2024:51. doi: 10.3892/or.2024.8705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boehm K.M., Aherne E.A., Ellenson L., Nikolovski I., Alghamdi M., Vázquez-García I., et al. Multimodal data integration using machine learning improves risk stratification of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nature Cancer. 2022;3:723–733. doi: 10.1038/s43018-022-00388-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akazawa M., Hashimoto K. Artificial intelligence in gynecologic cancers: current status and future challenges – A systematic review. Artif. Intell. Med. 2021;120 doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2021.102164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.