Abstract

Background

With the popularity of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) and the growth of time that humans spend indoors, people have begun to think more about what kind of indoor air-conditioned environments are beneficial and sustainable for health, especially for preventing respiratory infectious diseases. This study aims to explore the role of airflow in mechanically ventilated environments in modulating airway immune and defense mechanisms.

Methods

Based on the self-developed mouse-applicable climate chamber system and the corresponding mouse model, this study investigated the health effects of exposure to thermal environments [(I) 20 ℃, 0 m/s; (II) 20 ℃, 1.5 m/s; and (III) 15 ℃, 1.5 m/s] on influenza-infected mice (female, 6–8 weeks), of which body and organ weight, and survival situation were measured and recorded. Lung histopathologic changes were analyzed by hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. The messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) relative expression levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in lung tissues were determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Lung tissue virus titer measurement was also conducted. We also collected peripheral blood samples for blood cell counts to assess the impact of environmental conditions on systemic inflammation.

Results

Prolonged mild exposure to cold airflow inhibited weight gain and significantly increased lung coefficient. The relative mRNA expression of inflammatory factors in lung tissues was elevated considerably and the area occupied proportion of the lung interstitium was significantly increased after cold airflow exposure. However, peripheral blood neutrophil and lymphocyte percentages were not significantly different from those of the control group. While there were remarkable differences in body weight changes, survival situations, lung coefficients, lung tissue viral titers, and peripheral blood neutrophil and lymphocyte percentages for mice with different environmental exposure experiences after viral infection.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the effects of airflow on health do not exist independently of temperature. Prolonged mild cold airflow in air-conditioned environments may induce respiratory injury and thus exacerbate respiratory virus infection outcomes, suggesting that the effect of airflow in air-conditioned environments should receive due attention in protecting public respiratory health.

Keywords: Airflow stimulation, air conditioning temperature, respiratory infection, mouse model

Highlight box.

Key findings

• Our study confirms that prolonged exposure to cold airflow in air-conditioned environments may cause respiratory damage and aggravate pulmonary and systemic inflammatory outcomes after respiratory viral infections.

What is known and what is new?

• Extreme climate conditions, particularly the temperature and relative humidity, contribute to respiratory virus infections by influencing the survival stability and transmission of respiratory viruses as well as the systematic immune response.

• We determine the potential role of mild airflow and temperature co-stimulation in respiratory virus infection in indoor air-conditioned environments by constructing a mouse model of airflow exposure followed by respiratory virus infection.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Our study confirms that even in indoor air-conditioned environments, prolonged mild airflow stimulation can likewise cause respiratory damage and increase the risk of exacerbating pathological symptoms following respiratory infections, which do not exist independently of temperature. This study may provide new theoretical guidance for constructing buildings with optimal environmental conditions for health. However, further exploration is needed to determine the biological mechanisms of thermal environmental factors inducing human respiratory infections.

Introduction

The indoor environment is the major venue of respiratory infection outbreaks (1), due to the fact that modern people spend more than 80% to 90% of their time indoors (2). The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has further prompted a re-examination of the role of indoor environments in contributing to human health rather than merely preventing the triggering and worsening of sensitive subpopulations (3).

Studies have shown that climate, particularly temperature (T) and relative humidity (RH), plays an important role in respiratory virus infections by influencing the survival stability and transmission of respiratory viruses as well as the systematic immune response. Gustin et al. observed that respiratory droplet transmission among ferrets occurred with the most efficient T/RH at 23 ℃/30% and the least efficient at 23 ℃/50% and 5 ℃/70% (4). Experiments by Lowen et al. using guinea pigs as influenza virus hosts showed that viral spread was generally more efficient at 5 ℃ compared to 20 ℃, even with a high RH of 80% (5). The research results from Kudo et al. illustrated that exposure to low RH at 10–20% caused influent A virus (IAV)-infected mice to suffer more severe symptoms than those at a higher RH (6). Moriyama et al. claimed that exposing infected mice to temperatures up to 36 ℃ impaired their adaptive immune response to influenza virus infection (7). It was found that either a high-temperature stress of 39 ℃ or a low-temperature stress of 4 ℃ could promote elevated natural killer cell activity in the blood (8). Larsson et al. found that exposure to cold air of −23 ℃ increased the number of granulocytes and macrophages in the lower airways of healthy subjects (9). Temperature also acts as a stressor to activate the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to mediate systemic immune responses (10-12). Juránková et al. also observed elevated norepinephrine concentrations in plasma samples from subjects exposed to cold air (in a swimming suit, 4 ℃ for 30 min) (13).

The popularity of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) has revolutionized how people live, greatly improving thermal comfort in indoor environments. However, for most existing indoor air-conditioned buildings, especially those under cooling conditions, the range of indoor thermal parameters deviates from the recommended range for thermal comfort demand (14). It has not been determined whether such mild indoor thermal discomfort, especially caused by airflow, affects respiratory infections. Limited Studies have explained the correlation between airflow and respiratory infections, and most have focused on the effect on the transmission of respiratory viruses rather than on the body’s immune defense response (15,16).

Numerous field studies have found that complaints about air movement are prevalent (17-20). Cruz and Togias believed that cold air-provoked rhinitis symptoms (mainly characterized by rhinorrhea and nasal congestion, often accompanied by an intranasal burning sensation) frequently become accentuated under windy conditions (21). Abundant research on exercise and immunity has supported this argument (22,23). Previous evidence has demonstrated that the effects of thermal environmental factors on immune function may be related to stress duration. Acute stress experiences may enhance innate and adaptive immune responses, whereas chronic stress experiences may have deleterious immunological implications (24). Whether this chronic mild discomfort caused by air movement in air-conditioned environments is associated with the impairment of the airway defense barrier, thereby increasing susceptibility to respiratory infections and exacerbating pathological responses post-infection, is critical to determining thermal parameter regulation thresholds and creating comfortable and healthy indoor environments.

However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, research on the effects of airflow on airway physiologic and pathologic responses in simulated indoor climates is still in its infancy, involving both experimental devices and animal models. In vivo and in vitro animal experiments are widely used to study the mechanism of airway and immune system responses caused by cold exposure (25-28), whereas only a few animal models of thermal stress consider the influence of air movement (29), which uses electric fans to create artificial winds rather than air conditioning. There is still a lack of animal experimental devices that can accurately simulate the airflow in air-conditioned indoors in engineering. Even more, several cold-exposure animal models used cold water immersion as the stressor (30,31), from which whether the results obtained can be generalized to mild air movement exposure in air-conditioned environments is a knowledge gap. To investigate whether airflow in mechanically ventilated environments is involved in modulating airway immune and defense mechanisms, a mouse-applicable climate chamber system capable of quantitatively regulating ambient temperature, humidity, and supply airflow velocity was developed. In addition, we constructed a model of respiratory virus infection in mice after exposure to airflow, thus determining the potential role of airflow and temperature co-stimulation in respiratory virus infection. We present this article in accordance with the ARRIVE reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1546/rc).

Methods

Experimental device

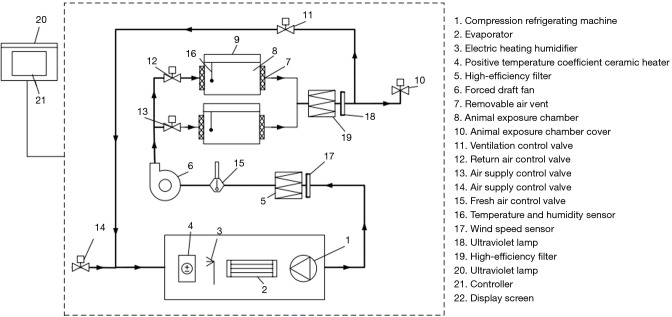

To simulate indoor air-conditioning environments, an animal-applicable climate chamber system that can control ambient T, RH and air velocity and meet the requirements of bio-safety protection is required. As shown in Figure 1, the climate chamber system for mice was commissioned to be manufactured by Wuxi Freshair AQ Technology Co., Ltd. The system has two feeding chambers and can individually control thermal parameters in each chamber. The adjustment ranges of air velocity, ambient T, and RH were 0–3 m/s, 14–30 ℃, and 40–90%, respectively. The high-efficiency filter and ultraviolet lamp were also equipped to ensure the cleanliness of class 10,000, which can be used for infectious animal experiments. This experimental device was housed in an animal bio-safety level 2 Plus (BSL-2+) laboratory, following governmental and institutional guidelines.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the climate chamber system for mice.

Mouse models

Healthy mice

Specific pathogen free (SPF) female BALB/c (Bagg albino with c/c color genotype, an albino laboratory-bred mouse strain) mice (6–8 weeks, 18–20 g) were purchased from Zhejiang Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. Mice were previously housed in an environment-controlled individual ventilated cages (IVC) (22±2 ℃, 50–60% RH, and 12 h light/12 h dark cycle) for 3 days to acclimatize. Sufficient feed and water were available ad libitum. The experiments were conducted in the Animal Laboratory of Zhongshan Development Zone, Institute of Analysis, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, and all procedures involved were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the above laboratory (approval No. W20210010). All procedures were conducted following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Infected mouse models

The murine lung-adapted strain of influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) (RP8) virus was cultured and amplified using 9-day-old SPF chicken embryos and then frozen and stored at −80 ℃. The 50% mouse lethal dose (LD50) of the H1N1 virus was determined by in vivo experiments. Briefly, the H1N1 virus was diluted in 10-fold serial gradients with phosphate buffer saline (PBS), with which mice (n=5 per group/dilution fold) were intranasally instilled in 25 µL after anesthetizing with isoflurane. After instillation, mortality was continuously monitored for 15 days. The LD50 value was calculated by the Reed-Muench method. In this study, mice were anesthetized and intranasally instilled with 25 µL PBS dissolving 1×LD50 H1N1 virus.

Study design and sample analysis

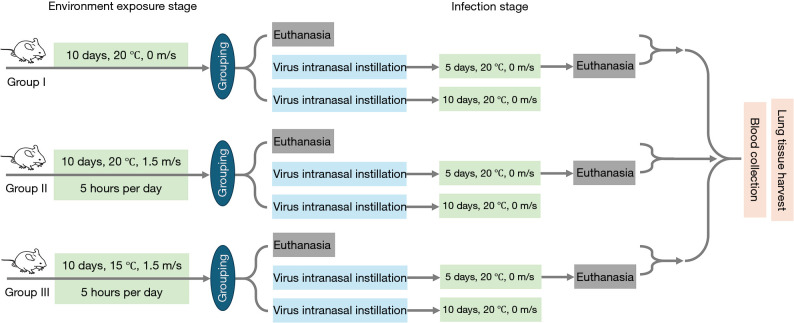

The experiment was designed to simulate the situation which healthy people are infected with a respiratory virus following prolonged exposure to airflow in air-conditioned environments in summer. A total of 48 healthy mice were equally divided into 3 groups of 16 mice each according to the completely randomized method, with different thermal exposure conditions among groups: (I) control group (20 ℃, 0 m/s); (II) neutral temperature airflow group (20 ℃, 1.5 m/s); and (III) cold temperature airflow group (15 ℃, 1.5 m/s). The 20-day experimental procedure is shown in Figure 2. During the first ten days, mice received airflow exposure interventions. This was done by placing mice in the climate chamber for 5-hour exposure each day and then returning them to the IVC (20 ℃, 0 m/s) at the end of daily intervention. The control group was always kept in the IVC. On day 10, after intervention, 5 mice from each group were euthanized by an overdose of pentobarbital sodium for sampling. The remaining mice were subjected to virus intranasal instillation and then housed in IVCs. On day 15, 6 mice from each group were euthanized to observe the indicators below. The remaining 5 mice were kept in the IVCs for daily recording of their body weight and survival rate.

Figure 2.

Experimental flowchart. Group I: control group (20 ℃, 0m/s); Group II: neutral temperature airflow group (20 ℃, 1.5 m/s); Group III: cold temperature airflow group (15 ℃, 1.5 m/s).

For the animal experiments above, only the experimenter knew the grouping. In addition, all procedures were conducted following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. During the experiments, to control for the effects of potential confounders, only the air temperature and supplied air velocity during the exposure period were changed among different groups. Maintain consistency in other experimental manipulations and rearing conditions. A protocol for animal experiments was prepared before the study without registration.

Body weight changes, survival rates, and lung coefficients

The body weights of mice were recorded daily before intervention until mice were painlessly executed when they reached the humane endpoint (20% or more weight loss). Mice euthanized on days 10 and 15 were not counted for survival rates if the change in body weight on that day did not reach the humane endpoint. Additionally, lung coefficients were calculated for mice euthanized on days 10 and 15, which expressed the percentage ratio of wet lung weight (mg) to body weight (g), characterizing lung lesions to some extent. It is well known that the weight ratio of each organ to the body is relatively constant in physiological health, whereas symptoms such as congestion, edema, or hyperplastic hypertrophy, which may occur after lung infection, can lead to changes in lung weight.

Blood collection and hematology analysis

Mice blood was collected from the orbital after euthanasia. The blood was collected into a 2 mL EP tube preloaded with 20 µL anticoagulant, which was obtained by dissolving 80 mg of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, dipotassium salt dihydrate (EDTA-2K) in 1 mL of pure water. An auto hematology analyzer (BC-5000Vet, Shenzhen Mindray Animal Medical Technology Co., Ltd., China) was used to analyze mice blood samples.

Lung tissue harvest

After extracting the whole lung tissue, the trachea was separated, in which the left lung was used for histopathological analysis, and the right lung was used for the determination of virus titer and messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) expression levels of cytokines. Then the right lung was ground and centrifuged to separate the supernatant and precipitate for the determination of viral titer and the extraction of RNA, respectively.

Virus titer determination

The 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) was conducted for the virus titer measurement. The tissues were homogenized using the medium, the supernatants were seeded onto Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells by 10-fold series dilution. After 48 h, infections were confirmed by hemagglutination assay. The virus titers were calculated according to the Reed-Muench method as described previously, and the specific procedure and calculation results were detailed in Table S1. Five replicate wells were set up for each concentration gradient of each sample.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA from tissue was extracted using Trizol reagent (15596026CN; Invitrogen, US). Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) synthesis was then performed using Hiscript IV RT SuperMix (R423; Vazyme, China). Real-time qPCR was conducted using Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Q712; Vazyme, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The sequences of the primers used are listed in Table S2.

Histological analysis

The left lung tissue was embedded in paraffin, cut into 5 µm sections, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Hematoxylin is an alkaline dye that stains chromatin in the nucleus and nucleic acids in the cytoplasm a violet-blue color; while eosin is an acidic dye that stains cytoplasmic and extracellular matrix components a red color. Histological section observation and image acquisition were performed using a revolve hybrid microscope (Echo). Quantitative analysis of the histological staining results was performed using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 26.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was employed to conduct the statistical analysis. Given the non-normal distribution of data, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was utilized to discern differences between before and after virus intranasal instillation in each group. Furthermore, the Mann-Whitney U test probed the differences among groups. We then applied linear fixed-effects models to estimate the correlations of exposure conditions with neutrophil and lymphocyte percentages. The percentages of neutrophils and lymphocytes were log-transformed because they followed a log-normal distribution. Exposure conditions were subsequently fitted as binary indicators (0 for 20 ℃ and 1 for 15 ℃; 0 for 0 m/s and 1 for 1.5 m/s) in the model to compare the differences in neutrophile and lymphocyte percentages after different thermal exposure experiences. All data were described as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Body weights and survival rates

Figure 3A illustrates the changes in body weight change rates (W%) over experiment time, which set the body weight measured on day 1 set as the baseline. The body weight of control group I increased normally before virus inoculation, and the change rate in body weight of group II fluctuated on the zero-horizontal line. However, the body weight of group III showed a decreasing trend under chill airflow exposure. As shown in Figure S1, the body weight change rate of mice in group II and group III on day 10 was statistically different from that of the control (W%II =−0.01±0.04 and W%III =−0.04±0.03 vs. W%I =0.03±0.05, P=0.01 and P<0.001, respectively), and the change rate in body weight of mice in group III was also significantly lower than that of mice in group II (P=0.02). On the 15th day, the body weight change rate of mice was −0.12±0.07 (group I), −0.17±0.02 (group II), and −0.20±0.04 (group III), respectively, which were statistically different among intergroups (P=0.03 for W%I vs. W%II, P=0.004 for W%I vs. W%III, P=0.03 for W%II vs. W%III). Beyond the 15th day, the fluctuations in the average weight change rate were not due to weight regain in mice, but rather, since some mice reached the humane endpoint and were euthanized, which were excluded from calculating the average weight change rate.

Figure 3.

Body weight change, survival situations. (A) Body weight changes of mice in every group with experiment days (day 1–10: n=16/group; day 11–15: n=11/group; day 16–20: n=1–5/group); (B) survival rates of mice in every group with experiment days (n=16/group); and (C) survival times of mice in each group after virus intranasal instillation (n=5/group I; n=7/group II; n=11/group III). The grey vertical dotted line indicates the time of viral inoculation. The red horizontal dotted line indicates the humane endpoint. Group I: control group (20 ℃, 0 m/s); Group II: neutral temperature airflow group (20 ℃, 1.5 m/s); Group III: cold temperature airflow group (15 ℃, 1.5 m/s).

Significant weight loss occurred in all three groups on the third day after virus inoculations, at which time all mice were observed to exhibit reduced activity, huddling, hunching, and fur ruffling. Mice in groups II and III showed a greater degree of weight loss than those in the control. On the fifth day after virus inoculations, some mice that reached the humane endpoint were found in all three groups. Especially, the survival rate in group III dropped directly to 27.27% (Figure 3B). Figure 3C shows the average survival time in each group after virus inoculation. The average survival time of mice in groups II and III decreased compared to the control group. Airflow exposure under cold air compared to that under neutral temperature had a harmful influence on the survival time of mice infected with the virus (P=0.08).

Pulmonary inflammatory response

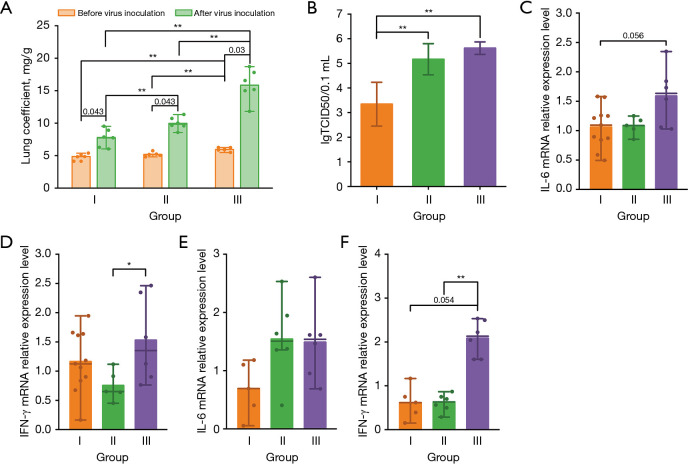

Lung coefficients and virus titer

To assess the effect of thermal environments on the virus replication and lung injury after influenza A virus inoculation, we calculated lung coefficients and lung tissue virus titers of mice separately (Figure 4A,4B). First of all, the lung coefficients of all three groups after virus inoculations (group I: 7.72±1.39 mg/g, group II: 9.97±0.97 mg/g, and group III: 15.84±2.45 mg/g) were significantly higher than those without (group I: 4.86±0.46 mg/g, group II: 5.19±0.35 mg/g, and group III: 5.95±0.29 mg/g), indicating that intranasal instillation was successful in achieving virus inoculation. Secondly, the experimental results showed that before virus inoculation, the lung coefficients of mice in group III were significantly higher than those of the control (P=0.006) and subgroup II (P=0.01); whereas, after virus inoculations, significant differences were found among the lung coefficients of all three groups. From the above analysis, the differences in the body weight change rates of mice exposed to different environmental conditions were statistically significant. Therefore, to further investigate whether the changes in lung coefficients were dominated by body weight loss or lung lesions, we recalculated the lung coefficients using the baseline body weight as the denominator. As shown in Figure S2, the statistical differences among subgroups were not affected by the body weight loss, implying that the notable differences in lung coefficients between groups were dominantly caused by the changes in wet lung weight. In other words, airflow exposure might significantly exacerbate the extent of lung lesions in mice after infection, which was further confirmed by the lung virus titers after virus inoculation shown in Figure 4B. The lung tissue virus titers of mice in group II (5.17±0.63 lgTCID50/0.1 mL) and group III (5.62±0.25 lgTCID50/0.1 mL) mice were significantly greater than those in the control group (3.34±0.89 lgTCID50/0.1 mL), with the P values being both less than 0.01. The virus titers of mice in group III mice were also slightly higher than those in group II, but not statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Lung coefficient, virus titer, and inflammatory factor mRNA relative expression level of lung tissue. (A) Lung coefficients for mice in each group before and after virus intranasal instillation (n=5/group before virus inoculation; n=6/group after virus inoculation); (B) virus titers of lung tissues for mice in each group after virus intranasal instillation (n=6/group); (C,D) lung mRNA expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6 (C), and IFN-γ (D) before virus intranasal instillation (n=5/group); and (E,F) lung mRNA expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6 (E), and IFN-γ (F) after virus intranasal instillation (n=6/group). The bars indicate the mean, and the lines indicate the median. Group I: control group (20 ℃, 0 m/s); Group II: neutral temperature airflow group (20 ℃, 1.5 m/s); Group III: cold temperature airflow group (15 ℃, 1.5 m/s). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01. IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL-6, interleukin-6; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; TCID50, 50% tissue culture infectious dose.

Proinflammatory cytokine mRNA expression level

Figure 4C,4D shows the relative mRNA expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in lung tissue of each group before virus inoculation, which was calculated using the average ΔCt of corresponding proinflammatory cytokine for group I before virus inoculation as the control, respectively. The relative expression of IL-6 mRNA in group III was slightly higher than that in the control group (P=0.056), and its relative expression of IFN-γ mRNA was also significantly higher than that in group II exposed to neutral-temperature airflow (P=0.045), suggesting that exposure to cold-airflow may induce an increased amount of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the lungs. Figure 4E,4F showed the relative mRNA expression of IL-6 and IFN-γ in lung tissue of each group after virus intranasal instillation, which was calculated using the average ΔCt of corresponding proinflammatory cytokine for group I after virus intranasal instillation as the control, respectively. The relative expression of IL-6 mRNA was higher than that of group I in groups II and III, but not statistically significant. While the relative expression of IFN-γ mRNA in group III was significantly greater than that of groups I (P=0.054) and II (P=0.004). A review (32) published in the past has shown that the average protein and/or mRNA levels of large ensembles of cells can remain relatively stable over time (usually above several hours). Under such circumstances, mRNA levels primarily explain protein levels. So, these results might suggest, to some extent, that cold airflow exposure experience may exacerbate pulmonary inflammation after viral infection.

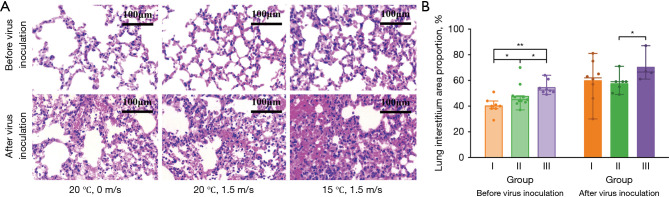

Lung histopathology

To examine pneumonia in mice, histopathology of the lung was performed as shown in Figure 5A. Microscopically, before virus inoculation, the alveoli of mice in the control group were structurally intact and relatively well-arranged, with no obvious pathological changes. Slight alveolar capillary hyperemia and exudation of a few inflammatory cells were observed in lung tissue sections of mice in groups II and III. In contrast, after virus inoculation, obvious pathological changes were observed in lung tissue sections of mice from all groups, varying in the degrees of hyperemic alveolar septa, inflammatory cell infiltration, and diffuse intra-alveolar edema, with the most severe degree of lung tissue lesions in mice from group III. Figure 5B illustrates the results of a quantitative analysis of the area percentage occupied by lung interstitium in H&E images of lung sections. Results demonstrate that exposure to airflow would cause the widening of lung interstitium compared with the control group (P=0.03), which might be aggravated by lowering the temperature (P=0.01). Not only that, after virus inoculation, the lung interstitium area percentage of the lung section in group III exposed to cold airflow was also much larger than that of group II with neutral-temperature airflow (P=0.04).

Figure 5.

Histopathological analysis. (A) Representative H&E images of lung sections for mice in each group after virus inoculation and (B) Proportion of the area occupied by lung interstitium in H&E images of lung sections for mice in each group before and after virus inoculation (n=5/group before virus inoculation; n=6/group after virus inoculation). The bars indicate the mean, and the lines indicate the median. Group I: control group (20 ℃, 0 m/s); Group II: neutral temperature airflow group (20 ℃, 1.5 m/s); Group III: cold temperature airflow group (15 ℃, 1.5 m/s). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01. H&E, hematoxylin-eosin.

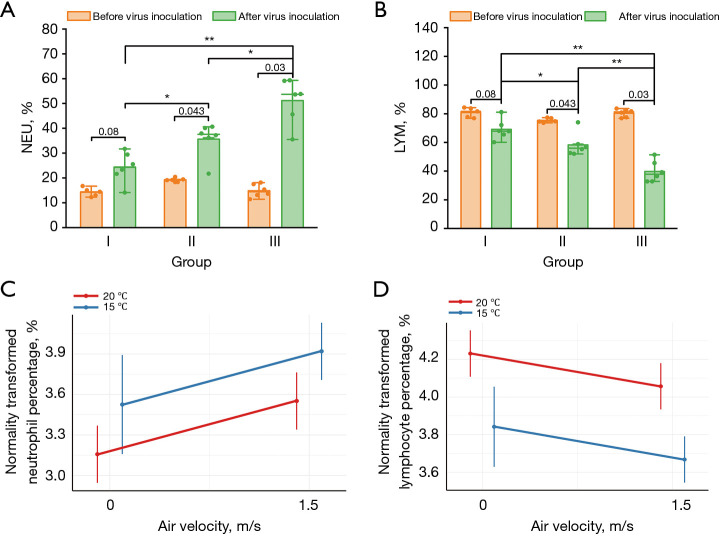

Blood cell analysis

Neutrophilia and lymphopenia were observed in all infected mice five days after virus inoculation (Figure 6A,6B). In hematological analysis, lymphocyte percentage (LYM%) and neutrophil percentage (NEU%) refer to their percentage of total white blood cells, respectively, both of which are key indicators of inflammation. There was strong evidence supporting that the NEU% of mice blood in groups II (P=0.03) and III (P=0.004) after inoculation was much greater than that in the control group, and the NEU% in group III was also significantly greater than that in group II (P=0.04). Whereas, the change in lymphocytes was the opposite, with the LYM% in groups II (P=0.04) and III (P=0.004) being much smaller than that in the control group, and the LYM% in the group III also being significantly smaller than that in group II (P=0.004).

Figure 6.

Hematology analysis. Percentage of (A) neutrophils and (B) lymphocytes in peripheral blood for mice in each group before and after virus inoculation (n=5/group before virus inoculation; n=6/group after virus inoculation); and predictive effect plot of supply air velocity affecting neutrophil (C) and lymphocyte (D) percentages under 20 and 15 ℃ after virus inoculation. Group I: control group (20 ℃, 0 m/s); Group II: neutral temperature airflow group (20 ℃, 1.5 m/s); Group III: cold temperature airflow group (15 ℃, 1.5 m/s). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01. LYM, lymphocyte; NEU, neutrophil.

Since neutrophilia and lymphocytopenia after virus intranasal instillation showed a significant gradient relationship among groups, we further applied a linear fixed-effects model to predict the effects of changes in temperature and air velocity on neutrophil and lymphocyte percentages after virus inoculation in mice blood. We found that the NEU% and LYM% in blood samples were significantly increased (β=0.39, P=0.01) and decreased (β=−0.17, P=0.049), respectively, at 1.5 m/s relative to the control condition, and were also significantly changed at 15 ℃ relative to 20 ℃ (NEU%: β=0.37, P=0.02; LYM%: β=−0.39, P<0.001). Figure 6C,6D illustrate the predicted effect plots of the log-transformed NEU% and LYM% for temperature and air velocity as fixed effect terms, respectively. Predicted effects after exponential transformation showed that when the temperature condition was 20 ℃, the predicted NEU% in mice blood under 0 and 1.5 m/s were 23.57% (95% CI: 19.11–29.08%) and 34.81% (95% CI: 28.22–42.95%), respectively; and the predicted LYM% was 68.72% (95% CI: 60.95–77.48%) and 57.97% (95% CI: 50.91–65.37%), respectively. While under 15 °C, the predicted NEU% in mice blood when exposure to air velocities of 0 and 1.5 m/s were 34.12% (95% CI: 23.57–48.91%) and 50.40% (95% CI: 40.85–62.18%), respectively; and the predicted LYM% was 46.53% (95% CI: 37.71–57.40%) and 39.25% (95% CI: 34.47–44.26%), respectively.

Discussion

This study focuses on the relationship between air movement and respiratory infections in air-conditioned thermal environments. In response, we developed an animal-applicable climate chamber with controllable air velocity, temperature, and humidity and established a mouse model of respiratory virus infection following exposure to airflow. Our study shows that prolonged mild exposure to airflow inhibits body weight gain and significantly increases lung coefficients, and that low temperature would worsen these symptoms. The mRNA relative expression levels of IL-6 and IFN-γ underwent a significant increase after low-temperature airflow exposure. Lung histopathologic sections also showed a significant increase in the area occupied proportion of the lung interstitium of groups II and III compared with the control group, and low temperature worsened the lung pathological changes caused by airflow exposure. However, no significant changes were observed in the percentage of neutrophils and lymphocytes in the peripheral blood. In contrast, after viral infection, there were remarkable differences in body weight changes, survival situations, lung coefficients, lung tissue viral titers, and peripheral blood neutrophil and lymphocyte percentages for mice with different environmental exposure experiences. The experimental results of lung histopathologic sections and mRNA relative expression level of inflammatory factors reflected that lung infectious inflammation may be more severe after exposure to chill airflow.

Some research evidence suggests that deviating from thermal comfort may be detrimental to respiratory health. For patients with non-infectious respiratory diseases such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, an uncomfortable temperature environment may worsen their clinical symptoms (3). Animal studies have indicated that airway inflammation in asthma mice was directly affected by exposure to the variation of the air temperature in 26/10 ℃ cycle and decreasing temperature from 30 to 20 ℃ (26,28). In addition, current epidemiologic evidence has supported the relationship between thermal environments and infectious respiratory diseases (33). Influenza virus infection in humans is influenced by a combination of internal and external factors. The pathogenesis of the influenza virus depends on the function of the immune system, such as upper respiratory mucosal immunity, innate and adaptive immunity, and a regulatory immune system that exists in the lung (34-36). Externally, environmental conditions may also influence influenza virus infection by affecting the immune status of the body. Seasonal variations in the incidence of respiratory tract infections caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), influenza viruses and respiratory syncytial viruses were confirmed (37). It was recently suggested that the production of several cytokines [tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-1β, and IL-6] shows a significant peak in summer, while circulating alpha 1-antitrypsin (AAT) concentrations were highest in the winter (36). The low cytokine response to influenza in winter may be an important pathophysiological factor for this phenomenon. However, the effects of mild airflow stimulation in indoor air-conditioned environments on the immune status of the respiratory system, the consequences of influenza virus infections, and their biological mechanisms remain largely unknown. Thus, the work conducted in this study on the effects of air movement in indoor air-conditioned environments on respiratory viral infections is of great significance in filling the research gap on the correlation between indoor thermal environments and respiratory health and providing referable experimental evidence for the construction of sustainable, comfortable, and healthy indoor environments.

The first conclusion of this study is that even in the absence of pathogen infection, air movement in air-conditioned environments, especially at low temperatures, has a significant inhibitory effect on the natural increase in mice body weight, and causes some lung injury, but no obvious peripheral inflammatory response was detected. The local inflammatory response in the respiratory system may be caused by the impaired local defense barrier resulting from the thermal environment. The airway defense barrier can be divided mainly into physical and immune barriers (38). The airway epithelium is an important component of the physical barrier, whose presence prevents antigenic substances entering the airway from easily invading the subepithelial tissues and maintains the stability of the mucosal microenvironment. Cruz et al. found that the number of epithelial cells in the nasal lavage fluid increased 6-fold after stimulation with cold and dry air (39). Previous animal experiments have also shown that short-term exposure of the airways to dry and cold air leads to significant epithelial detachment, subepithelial vascular congestion, edema, cellular infiltration, and longer periods for damaged lung epithelial cell repair (6,25). These results may be due to the fact that a cold, dry, and windy environment accelerates water evaporation from the nasal mucosa, leading to hypertonic nasal secretions (40). Additionally, airway cilia can serve by beating coordinately to clear particulate matter and pathogens from the mucus. Abnormal cilia function can result in stagnant mucus containing abundant pathogens. Clary-Meinesz et al. compared the ciliary beat frequency of human airway ciliated cells at different temperatures and found that the ciliary beat frequency started to decrease at temperatures below 20 ℃ and was almost nil at 5 ℃ (41).

It is well known that air movement accelerates skin cooling, leading to vasoconstriction that may activate sensory nerve endings. The hypertonicity of the nasal secretion and epithelial cell detachment that results in the exposure of sensory neurons may exacerbate the neuronal activation effect. Transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1) and transient receptor potential M8 (TRPM8) ion channels are widely distributed in neural and non-neural cells of the respiratory tract and are cold-temperature-sensitive (42). TRPA1 is present almost exclusively in substance P (SP)- and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-positive nociceptive afferents, whose activation prompts the release of these neuropeptides (43). SP and CGRP can induce mast cell degranulation and histamine and other cytokines release to cause edema, vasodilatation, and extravasation of immune cells (44,45). Whereas, activation of TRPM8 promotes mucin secretion, whose overexpression and accumulation would impair airway defense (46). In conclusion, the local inflammation of the respiratory system after cold airflow exposure may be due to local physical barrier damage and nerve endings stress, but does not cause a systemic inflammatory response as the symptoms are mild.

However, there are large inter-individual differences in the biological response to thermal environmental stimuli. Brazaitis et al. compared the physiological responses of two groups’ volunteers who exhibited fast and slow cooling in body temperature during cold water immersion, respectively, and surprisingly, only the subjects exhibiting slow cooling experienced a significant increase in the percentage of neutrophils and a significantly decreased percentage of lymphocytes and monocytes after cold stress (47). However, this may not be an immediate cause for alarm in healthy individuals, even though cold stimuli induce changes in stress and immune markers. But the problem arises when an immune challenge occurs (48).

Accordingly, the local airway damage described above may be responsible for the much more severe infection symptoms in the experimental group than in the control group after virus inoculations in the present study. Airway epithelium detachment, mucin overproduction, and ciliary beating frequency reduction all contribute to residence in the airway and invasion of subepithelial tissues for pathogens. Moreover, stimulation by thermal environments might also prolong the self-repair time of the damaged airway. According to the experimental setup of the present study, mice were kept in neutral environments after virus inoculations. However, the pathogenicity of the infection still showed significant differences among mice with different thermal exposure experiences, which may indicate the effect of thermal stimuli on the immune and antiviral defense capacity would not be eliminated immediately after the stressor was removed. Except for the physical barrier, cold airflow may also exacerbate post-infectious inflammation by suppressing the innate immune barrier in the airway, of which secretory immunoglobulin A (S-IgA) is a major effectivity factor and plays an important role in the first defense line against airborne pathogens (49). B cell-activating factor converts B cells into plasma cells, which acquire the ability to produce IgA. The in vitro experiments of Yoshino et al. suggested that low temperatures may inhibit the production of B cell-activating factor in epithelial cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells, thereby inhibiting IgA secretion (50). The mucosal immune system also enables an active host mucosal defense mechanism through extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are lipid-bound vesicles secreted by cells into extracellular space that carry a variety of components, including nucleic acids, proteins, and amino acids, and have been reported in virtually all human biological fluids (51). Cold air impairs antiviral immune defense functions by reducing total EVs secretion and decreasing microRNA packaging as well as the antiviral binding affinity of individual EV. A tissue culture experiment comparing the level of viral replication in rhinovirus-infected mice by playing epithelial cells at different temperatures found that the expression levels of type I and type III IFN genes and IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) were significantly higher at the core body temperature of 37 ℃ than at a cool temperature of 33 ℃ (27). In summary, the existing studies have demonstrated that thermal environmental factors may mediate the antiviral defense functions after respiratory viral infection through multiple physiological pathways, but most of the studies were in vitro experiments. Our study used in vivo experiments to demonstrate the combined effects of thermal environmental factors on the outcome of respiratory tract infections from a holistic perspective.

Our study, which exposed mice to a quantitatively mechanically ventilated chamber to mimic the mild airflow stimulation that humans may face in an indoor air-conditioned environment, clearly demonstrated decreased anti-respiratory viral defenses and exacerbated infection symptoms following long-time mild airflow stress, especially in cold temperature conditions. Thermal environments may not only be involved in mediating the susceptibility to respiratory viruses but also alter the likely outcome of respiratory infectious diseases. However, some limitations still should be noted. Firstly, it is well known that elevated air velocity is an effective energy-efficient approach for space cooling, which can offset heat stress caused by high temperatures and improve thermal comfort. There is now evidence showing that mice are also under chronic cold stress in a standard rearing environment of 20 ℃ and 0 m/s (28). In the future, further broader thermal parameters’ intervals are needed in the experimental design, and the animal-applicable climate chamber setup that we developed has the application potential for further study. Not only that, but applying these findings to human living environments requires more rigorous validation, given the distinct differences in thermal comfort conditions between mice and humans. The virus strain used in this study is a mouse lung-adapted strain, further studies should be conducted using animal models susceptible to human-derived virus strains, such as ferrets. Secondly, physiological responses to thermal stimuli are likely to be different among individuals of different genders, ages, or health situations. More scenario factors in the real world are required to be considered and simulated. Moreover, this experiment used intranasal instillation for the virus infection, which did not consider the effect of indoor airflow on the influenza virus transmission and lacked the process of extending the infection range from the upper to the lower respiratory tract. Finally, we plan to include experimental steps for detecting cytokine protein levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) using ELISA assay in future studies, which will help address the limitation of using qPCR alone to measure the relative mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines in lung tissue, as it cannot directly reflect the inflammation level.

Conclusions

Based on a self-developed mouse-applicable climatic chamber and a mouse model infected with influenza A H1N1 virus after airflow stress, this study emphasizes that prolonged exposure to mild airflow induces respiratory inflammatory injury in healthy individuals, and exacerbates pathological symptoms of respiratory virus infection. Whereas these effects of airflow do not exist independently of temperature, low ambient temperatures could further worsen these effects. These results suggest that mild cold airflow makes the body more sensitive to influenza virus infection. Further studies are needed to characterize the biological mechanisms of thermal environmental factors inducing respiratory infections, which may provide theoretical guidance for the construction of buildings with environmental conditions that are beneficial for health.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The animal procedures outlined in this study received approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of the Animal Laboratory of Zhongshan Development Zone, Institute of Analysis, Guangdong Academy of Sciences (approval No. W20210010). All procedures were conducted following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the ARRIVE reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1546/rc

Funding: This study was jointly supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82404322 and 82361168672), National Multidisciplinary Innovation Team Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Nos. ZYYCXTD-D-202201 and ZYYCXTD-D-202206), Young Scientists Program of Guangzhou Laboratory (No. QNPG24-10), National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFF0607002), Jiangsu Province Construction System Science and Technology Project (No. 2023ZD004), Guangzhou Science and Technology Planning Project (No. 2024B03J1385), and Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease (Nos. SKLRD-Z-202405, SKLRD-OP-202215 and SKLRD-OP-202209).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1546/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Sharing Statement

Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1546/dss

References

- 1.Qian H, Miao T, Liu L, et al. Indoor transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Indoor Air 2021;31:639-45. 10.1111/ina.12766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klepeis NE, Nelson WC, Ott WR, et al. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 2001;11:231-52. 10.1038/sj.jea.7500165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Amato M, Molino A, Calabrese G, et al. The impact of cold on the respiratory tract and its consequences to respiratory health. Clin Transl Allergy 2018;8:20. 10.1186/s13601-018-0208-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gustin KM, Belser JA, Veguilla V, et al. Environmental Conditions Affect Exhalation of H3N2 Seasonal and Variant Influenza Viruses and Respiratory Droplet Transmission in Ferrets. PLoS One 2015;10:e0125874. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Steel J, et al. Influenza virus transmission is dependent on relative humidity and temperature. PLoS Pathog 2007;3:1470-6. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kudo E, Song E, Yockey LJ, et al. Low ambient humidity impairs barrier function and innate resistance against influenza infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:10905-10. 10.1073/pnas.1902840116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moriyama M, Ichinohe T. High ambient temperature dampens adaptive immune responses to influenza A virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:3118-25. 10.1073/pnas.1815029116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lackovic V, Borecký L, Vigas M, et al. Activation of NK cells in subjects exposed to mild hyper- or hypothermic load. J Interferon Res 1988;8:393-402. 10.1089/jir.1988.8.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsson K, Tornling G, Gavhed D, et al. Inhalation of cold air increases the number of inflammatory cells in the lungs in healthy subjects. Eur Respir J 1998;12:825-30. 10.1183/09031936.98.12040825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eimonte M, Eimantas N, Baranauskiene N, et al. Kinetics of lipid indicators in response to short- and long-duration whole-body, cold-water immersion. Cryobiology 2022;109:62-71. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2022.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eimonte M, Eimantas N, Daniuseviciute L, et al. Recovering body temperature from acute cold stress is associated with delayed proinflammatory cytokine production in vivo. Cytokine 2021;143:155510. 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eimonte M, Paulauskas H, Daniuseviciute L, et al. Residual effects of short-term whole-body cold-water immersion on the cytokine profile, white blood cell count, and blood markers of stress. Int J Hyperthermia 2021;38:696-707. 10.1080/02656736.2021.1915504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juránková E, Jezová D, Vigas M. Central stimulation of hormone release and the proliferative response of lymphocytes in humans. Mol Chem Neuropathol 1995;25:213-23. 10.1007/BF02960914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendell MJ, Mirer AG. Indoor thermal factors and symptoms in office workers: findings from the US EPA BASE study. Indoor Air 2009;19:291-302. 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C, Zhao B, Yang X, et al. Role of two-way airflow owing to temperature difference in severe acute respiratory syndrome transmission: revisiting the largest nosocomial severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in Hong Kong. J R Soc Interface 2011;8:699-710. 10.1098/rsif.2010.0486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Duan S, Yu IT, et al. Multi-zone modeling of probable SARS virus transmission by airflow between flats in Block E, Amoy Gardens. Indoor Air 2005;15:96-111. 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00318.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atthajariyakul S, Lertsatittanakorn C. Small fan assisted air conditioner for thermal comfort and energy saving in Thailand. Energy Convers Manag 2008;49:2499-504. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cândido C, de Dear RJ, Lamberts R, et al. Air movement acceptability limits and thermal comfort in Brazil’s hot humid climate zone. Build Environ 2010;45:222-9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang L, Ouyang Q, Zhu Y, et al. A study about the demand for air movement in warm environment. Build Environ 2013;61:27-33. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H, Arens E, Fard SA, et al. Air movement preferences observed in office buildings. Int J Biometeorol 2007;51:349-60. 10.1007/s00484-006-0079-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruz AA, Togias A. Upper airways reactions to cold air. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2008;8:111-7. 10.1007/s11882-008-0020-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derman W, Badenhorst M, Eken M, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory illnesses in athletes: a systematic review by a subgroup of the IOC consensus on 'acute respiratory illness in the athlete'. Br J Sports Med 2022;56:639-50. 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koskela HO. Cold air-provoked respiratory symptoms: the mechanisms and management. Int J Circumpolar Health 2007;66:91-100. 10.3402/ijch.v66i2.18237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhabhar FS. Enhancing versus suppressive effects of stress on immune function: implications for immunoprotection and immunopathology. Neuroimmunomodulation 2009;16:300-17. 10.1159/000216188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbet JP, Chauveau M, Labbé S, et al. Breathing dry air causes acute epithelial damage and inflammation of the guinea pig trachea. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1988;64:1851-7. 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.5.1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du C, Kang J, Yu W, et al. Repeated exposure to temperature variation exacerbates airway inflammation through TRPA1 in a mouse model of asthma. Respirology 2019;24:238-45. 10.1111/resp.13433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foxman EF, Storer JA, Fitzgerald ME, et al. Temperature-dependent innate defense against the common cold virus limits viral replication at warm temperature in mouse airway cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:827-32. 10.1073/pnas.1411030112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao W, Zhou L, Zhao X, et al. Thermoneutral housing temperature regulates T-regulatory cell function and inhibits ovabumin-induced asthma development in mice. Sci Rep 2017;7:7123. 10.1038/s41598-017-07471-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng GM, Yu JX, Xu JQ, et al. Exposure to artificial wind increases energy intake and reproductive performance of female Swiss mice (Mus musculus) in hot temperatures. J Exp Biol 2020;223:jeb231415. 10.1242/jeb.231415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaur S, Singh N, Jaggi AS. Opening of T-type Ca2+ channels and activation of HCN channels contribute in stress adaptation in cold water immersion stress-subjected mice. Life Sci 2019;232:116605. 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Duan C, Wu S, et al. Knockout of IL-6 mitigates cold water-immersion restraint stress-induced intestinal epithelial injury and apoptosis. Front Immunol 2022;13:936689. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.936689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Beyer A, Aebersold R. On the Dependency of Cellular Protein Levels on mRNA Abundance. Cell 2016;165:535-50. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He Y, Liu WJ, Jia N, et al. Viral respiratory infections in a rapidly changing climate: the need to prepare for the next pandemic. EBioMedicine 2023;93:104593. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuyama S, Kawaoka Y. The pathogenesis of influenza virus infections: the contributions of virus and host factors. Curr Opin Immunol 2011;23:481-6. 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su F, Patel GB, Hu S, et al. Induction of mucosal immunity through systemic immunization: Phantom or reality? Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12:1070-9. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1114195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ter Horst R, Jaeger M, Smeekens SP, et al. Host and Environmental Factors Influencing Individual Human Cytokine Responses. Cell 2016;167:1111-1124.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moriyama M, Hugentobler WJ, Iwasaki A. Seasonality of Respiratory Viral Infections. Annu Rev Virol 2020;7:83-101. 10.1146/annurev-virology-012420-022445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu X, Shi Y. Airway defense barrier. Chinese Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2011;10:301-4. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cruz AA, Naclerio RM, Proud D, et al. Epithelial shedding is associated with nasal reactions to cold, dry air. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117:1351-8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Togias AG, Proud D, Lichtenstein LM, et al. The osmolality of nasal secretions increases when inflammatory mediators are released in response to inhalation of cold, dry air. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988;137:625-9. 10.1164/ajrccm/137.3.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clary-Meinesz CF, Cosson J, Huitorel P, et al. Temperature effect on the ciliary beat frequency of human nasal and tracheal ciliated cells. Biol Cell 1992;76:335-8. 10.1016/0248-4900(92)90436-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKemy DD. How cold is it? TRPM8 and TRPA1 in the molecular logic of cold sensation. Mol Pain 2005;1:16. 10.1186/1744-8069-1-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Story GM, Peier AM, Reeve AJ, et al. ANKTM1, a TRP-like channel expressed in nociceptive neurons, is activated by cold temperatures. Cell 2003;112:819-29. 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00158-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McNeil BD, Pundir P, Meeker S, et al. Identification of a mast-cell-specific receptor crucial for pseudo-allergic drug reactions. Nature 2015;519:237-41. 10.1038/nature14022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Verri WA, Jr, Chiu IM. Nociceptor Sensory Neuron-Immune Interactions in Pain and Inflammation. Trends Immunol 2017;38:5-19. 10.1016/j.it.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li M, Li Q, Yang G, et al. Cold temperature induces mucin hypersecretion from normal human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro through a transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8)-mediated mechanism. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:626-34.e1-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Brazaitis M, Eimantas N, Daniuseviciute L, et al. Two strategies for response to 14 °C cold-water immersion: is there a difference in the response of motor, cognitive, immune and stress markers? PLoS One 2014;9:e109020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacDonald CR, Choi JE, Hong CC, et al. Consideration of the importance of measuring thermal discomfort in biomedical research. Trends Mol Med 2023;29:589-98. 10.1016/j.molmed.2023.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russell MW, Mestecky J. Mucosal immunity: The missing link in comprehending SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission. Front Immunol 2022;13:957107. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.957107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshino Y, Yamamoto A, Misu K, et al. Exposure to low temperatures suppresses the production of B-cell activating factor via TLR3 in BEAS-2B cells. Biochem Biophys Rep 2020;24:100809. 10.1016/j.bbrep.2020.100809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang D, Taha MS, Nocera AL, et al. Cold exposure impairs extracellular vesicle swarm-mediated nasal antiviral immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023;151:509-525.e8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]