Abstract

Background

Mental disorders are common in the United States. According to the National Institute of Mental Health more than 23% of the adult population in the United States live with some form of mental illness. Genome-wide association studies have implicated CACNA1C, which encodes the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel CaV1.2, and it has been suggested that the expression levels of CACNA1C may be associated with mental illness. To this end, we have generated a novel mouse line that conditionally overexpresses the mouse ortholog Cacna1c.

Methods

Transgenic mice (CaV1.2Tg+ mice) were characterized for expression and distribution of CaV1.2. The CaV1.2Tg+ mice were compared with control littermates using assays that examined cognitive and affective behaviors. Cortical network dynamics were assessed using in vivo multiphoton calcium imaging.

Results

Compared with their control littermates, CaV1.2Tg+ mice exhibited a ∼1-fold increase in CaV1.2 expression. Behavioral characterization of the CaV1.2Tg+ mice revealed a complex phenotype in which they exhibited deficits in the consolidation of fearful memories and an increase in anxiolytic-like behavior. The CaV1.2Tg+ mice also appeared to have altered cortical dynamics in which the network was more dense but less synchronized.

Conclusions

We have successfully generated mice that overexpress the mouse ortholog of a gene that has been implicated in several psychiatric diseases. Our initial characterization suggests that these mice have alterations in behavior and neural function that have been linked to mental illness. It is anticipated that future studies will reveal additional neurobehavioral alterations whose mechanisms will be studied.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, Cortical subnetworks, L-type calcium channel CaV1.2, Psychiatric risk variant, Schizophrenia

Plain Language Summary

More than 23% of the adult population in the United States live with some form of mental illness. Several genes have been identified, which appear more frequently in people diagnosed with a psychiatric condition, that have small alterations of unknown significance. There is some evidence suggesting that expression levels of one of these genes, CACNA1C, may be altered in psychiatric patients. To address this question, using genetic engineering, we have generated mice that overexpress the mouse version of CACNA1C. Our initial characterization suggests that these mice have alterations in behavior and neural function that have been linked to mental illness.

Plain Language Summary

More than 23% of the adult population in the United States live with some form of mental illness. Several genes have been identified, which appear more frequently in people diagnosed with a psychiatric condition, that have small alterations of unknown significance. There is some evidence suggesting that expression levels of one of these genes, CACNA1C, may be altered in psychiatric patients. To address this question, using genetic engineering, we have generated mice that overexpress the mouse version of CACNA1C. Our initial characterization suggests that these mice have alterations in behavior and neural function that have been linked to mental illness.

Voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) are multisubunit membrane complexes that are responsible for gating calcium entry upon membrane depolarization, resulting in regulation of gene expression, calcium release from intracellular stores, neuronal excitability and plasticity, neurogenesis, and secretion of hormones and neurotransmitters (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Each complex consists of an α1 pore-forming subunit together with at least 2 of the 3 accessory subunits. The α1 subunit is made up of 4 homologous domains (each of which includes 6 transmembrane α-helices) that are connected by intra- and extracellular loops with the NH2 and COOH ends located in the cytoplasmic space (1,2). Most of the pharmacological and gating properties are determined by the α1 subunit, while the accessory subunits ensure proper trafficking, membrane insertion, and modulation of channel kinetics (6).

VGCCs have been divided into subfamilies based on the currents that they gate as well as their pharmacology. The L-type VGCCs (LVGCCs) are described as having large and long-lasting currents that are blocked by dihydropyridines such as nimodipine (5). There are 4 known LVGCCs but only 2, CaV1.2 and CaV1.3, are highly expressed in the brain. Although CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 share significant homology in DNA and protein sequence (7), they differ significantly in their biophysical properties (8, 9, 10), distribution (11) and abundance, with CaV1.2 being more highly expressed (12).

Given the important role that LVGCCs play in neuronal function, it is unsurprising that mutations in genes that encode them result in neurological and psychiatric illness (13). Several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within noncoding regions of CACNA1C (which encodes the α1 subunit of CaV1.2) have been implicated by genome-wide association studies (GWASs) of several neuropsychiatric diseases (14,15), including bipolar disorder (BD) (16, 17, 18), schizophrenia (SCZ) (19, 20, 21), major depressive disorder (MDD) (22, 23, 24), and autism spectrum disorder (25, 26, 27).

Although the relationship between CACNA1C and neuropsychiatric disease is not fully understood, some of the implicated SNPs lie within enhancer regions within intron 3 of CACNA1C (28). Under normal conditions, these regions bind nuclear proteins and interact with the promoter and transcription start site, regulating gene expression (29,30). It seems plausible that SNPs in these areas differentially bind with nuclear proteins, ultimately interfering with transcriptional regulation, causing changes in CACNA1C expression. In support of this, changes in CACNA1C expression have been reported in individuals harboring risk SNPs within intron 3, with both increases (31, 32, 33) and decreases (28,31, 32, 33, 34) in expression depending on the brain region and cell type examined, suggesting that perturbations in CaV1.2 levels may contribute to disease.

Several rodent models have been developed to study the impact of reduced expression or complete loss of expression of CaV1.2, and there is a well-established mouse model that emulates aspects of Timothy syndrome (which is a gain-of-function mutation) (26); however, to our knowledge, the functional consequences of Cav1.2 overexpression have not yet been examined. To this end, we have developed a conditional mouse model that overexpresses CaV1.2. Importantly, the exogenous CaV1.2 contains a hemagglutinin (HA) tag to distinguish it from the endogenous protein. Here, we describe the generation and initial behavioral and neurophysiological characterization of these mice.

Methods and Materials

Transgene Construction

The full-length rat CaV1.2 complementary DNA (cDNA) containing a surface-expressed HA epitope (Figure 1A) was obtained from the sHA-Cav1.2 plasmid (a kind gift from E. Bourinet, Institute of Functional Genomics) (35). Previous work has demonstrated that the inclusion of the HA epitope does not alter protein folding, trafficking to the cellular membrane, cell surface levels, or channel function (35,36). The cloning and pronuclear injection strategy was modified from that which has been described previously (37).

Figure 1.

CaV1.2 transgene injection construct and expression analysis. (A) Schematic of the injection construct consisting of the CAG promoter, Loxp-3xStop-Loxp cassette cassette, 5′ UTR, CaV1.2Tg and 3′ UTR, as well as PCR primer and poly-A consensus sequence locations. The 12-kB transgene was linearized for injection using NotI restriction enzyme digestion. (B) Cartoon of the CaV1.2Tg protein product including the location of the HA epitope. (C) The CaV1.2Tg injection construct was expressed in HEK293 alone or with pCAG-ERT2-Cre-ERT2. Blots containing whole-cell lysates were probed with rat anti-HA to detect the presence of the transgenic protein and anti β-actin as a loading control. Only those samples co-expressing Cre recombinase (CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+) also expressed CaV1.2Tg. (D) Representative Western blots containing cell lysates from whole-brain tissue. Membranes were probed with either anti-CaV1.2 or anti-HA where appropriate and anti β-actin as a loading control. (D1) Immunoblotting with an HA-specific antibody reveals staining that is only present in tissue harvested from CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice. (D2) Western blot of total CaV1.2 protein (transgenic and endogenous). (E) Quantification of total CaV1.2. CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice express approximately 100% more CaV1.2 than their control or CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− littermates (F2,18 = 1.612, p = .0013; significant post hoc comparisons: wild-type × CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+, ∗∗p = .007. CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− × CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+, ∗∗p = .0018). All data are presented as mean ± SEM. HA, hemagglutinin; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; UTR, untranslated region.

Mice

Founder mice were genotyped similar to that which has been described previously (37) for the presence of the CaV1.2Tg by polymerase chain reaction. Experimental mice were generated by crossing hemizygous CaV1.2Tg+ mice with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of either the Synapsin I (SynTg+; SynTg+Tg(Syn1-cre)671Jxm/J strain #003966) (38) or CamKIIα (calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alpha) (CamKTg+; Tg(Camk2a-cre)T29-1Stl/J strain #005359) (39) promoter. Mice were fed ad libitum and kept on a schedule of 14:10-hour light/dark cycle. All procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Data Analysis

Western blots and confocal images were processed using Fiji (40). Tracking data during behavioral experiments were acquired with digital cameras and processed with LimeLight3 software or DeepLabCut (41). All behavioral experiments were analyzed with sex as a factor. No significant differences between sexes were found, so males and females were collapsed into a single group of the same genotype. The calcium network analysis used in-house MATLAB (version R2020b; The MathWorks, Inc.) routines to process the data. GraphPad Prism 8 and R were used to calculate statistical significance.

Additional Details

For detailed descriptions of biochemical, behavioral, and imaging methods, see the Supplement.

Results

Characterization of CaV1.2 Transgene Expression

The CaV1.2 injection construct consisted of the CAG promoter, Loxp-3xStop-Loxp (LSL) cassette, and an HA-tagged CaV1.2 cDNA flanked by a 5′ and 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (Figure 1A). The surface expressed HA epitope (Figure 1B) was included to allow for the distinction between endogenously expressed CaV1.2 and the CaV1.2 transgene (CaV1.2Tg), which importantly does not significantly affect the functional properties or cell surface levels of the channel (35,36). The 5′ and 3′ UTRs were included to help stabilize the messenger RNA and increase expression levels of the CaV1.2Tg (42), as well as provide the 3′ end poly-A sequence. The CAG promoter was chosen because it has a strong and ubiquitous expression pattern and has previously been used in conjunction with the LSL cassette, which restricts expression of the transgene to areas coexpressing Cre recombinase (43).

Prior to pronuclear injection, Cre recombinase mediated excision, and transgene expression was confirmed in vitro using HEK293 cells that were transfected with either the Cav1.2Tg plasmid or the Cav1.2Tg plasmid together with pCAG-ERT2-Cre-ERT2 (#13777; Addgene). Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates was performed with an antibody specific to HA. The Cav1.2Tg was detected only in those cells coexpressing the Cav1.2Tg plasmid and pCAG-ERT2-Cre-ERT2 (Figure 1C), confirming that in HEK293 cells, expression of Cav1.2Tg does not occur when the LSL cassette is intact.

The linearized construct was transferred to the University of Michigan Transgenic Core for pronuclear injection into fertilized eggs, which were subsequently implanted into C57BL/6J pseudopregnant female mice. Offspring were genotyped, and the colony was expanded by backcrossing onto a C57BL/6Tac genetic background.

For the initial analysis presented here, Cav1.2Tg+ mice were crossed with the pan-neuronal Cre driver line, Synapsin I Cre (SynTg+) (C57BL/6Tac genetic background) (38), resulting in 4 genotypes: CaV1.2Tg−; SynTg−, CaV1.2Tg−; SynTg+, CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg−, and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice. Western blot analysis was performed on whole-brain lysates to measure total CaV1.2 levels in CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice and confirm a lack of ectopic expression of the Cav1.2Tg in CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− mice. Membrane fractions were probed either with an antibody specific to CaV1.2 or to the HA-epitope together with anti-β-actin as a loading control. CaV1.2 was detected in all genotypes, with an obvious increase in immunostaining for CaV1.2 in the CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice (Figure 1D1). Immunostaining for HA was only present in CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice, confirming that there was no observable ectopic expression of the Cav1.2Tg (Figure 1D2) and indicating that the increase in total CaV1.2 was a result of expression of the Cav1.2Tg. Finally, quantification of total CaV1.2 revealed an approximately 100% increase in total CaV1.2 protein in CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice compared with both wild-type (WT) and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− littermates, with no difference in CaV1.2 levels between WT controls and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− mice (Figure 1E).

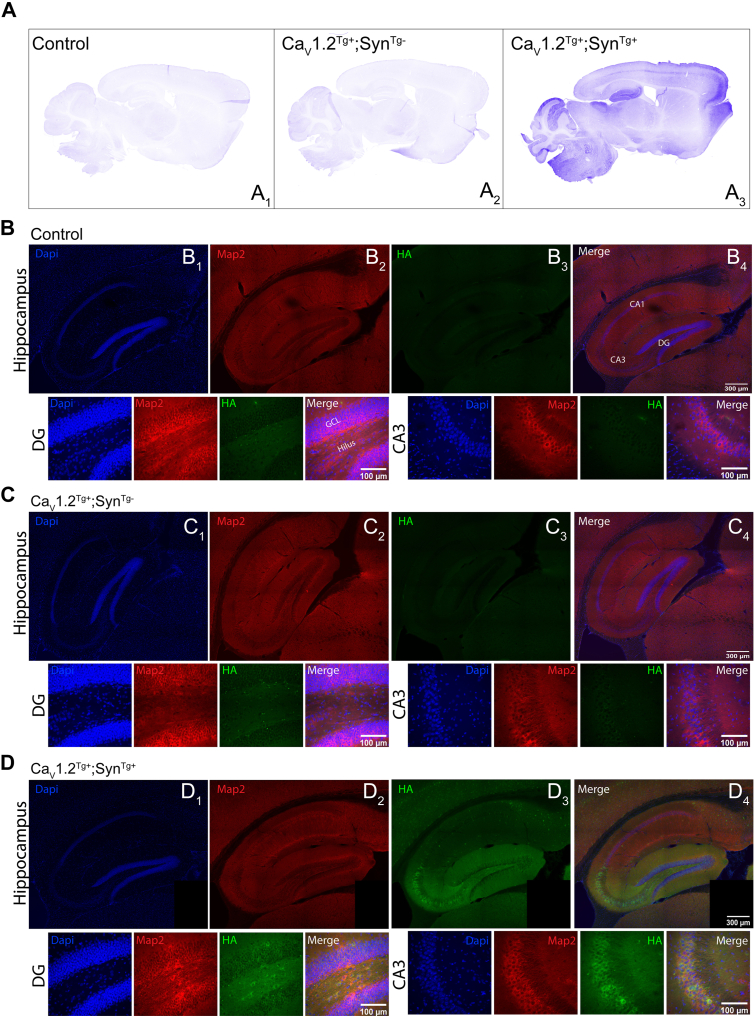

To examine the neuroanatomical distribution of transgene expression, sagittal sections were immunostained with the same HA-specific antibody, which revealed immunostaining that was restricted to CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice (Figure 2A). Consistent with the reported distribution of endogenous CaV1.2 in the hippocampus (11), higher-resolution images of the hippocampus revealed greater levels of CaV1.2Tg in the dentate gyrus and CA2/CA3 compared with CA1 (Figure 2B), with HA staining observed in both cell bodies and projections (Figure 2B, DG and CA3). Similar staining patterns were observed in the cerebellum (Figure S1A) and visual cortex (Figure S1B).

Figure 2.

Expression pattern of CaV1.2Tg in adult brain. (A) Representative confocal images of anti-HA staining of 25-μm sagittal sections of whole brain (4×). CaV1.2Tg expression is restricted to CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ brains (A3), confirming a lack of transgene expression without co-expression of Cre recombinase. (B–D) Representative confocal images (20×) of sagittal sections of the hippocampus taken from control (B), CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg−(C) and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+(D) mice immunostained with antibodies specific for DAPI (blue), MAP2 kinase (red), and HA (green). Staining for the HA tag is only observable in hippocampus recovered from the CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice (D3) and is particularly abundant in the DG and CA3 regions (40× images below main images). Note in panels (D1–D4), a tile is missing in the lower right corner that was lost during image acquisition. DG, dentate gyrus; GCL, granule cell layer; HA, hemagglutinin.

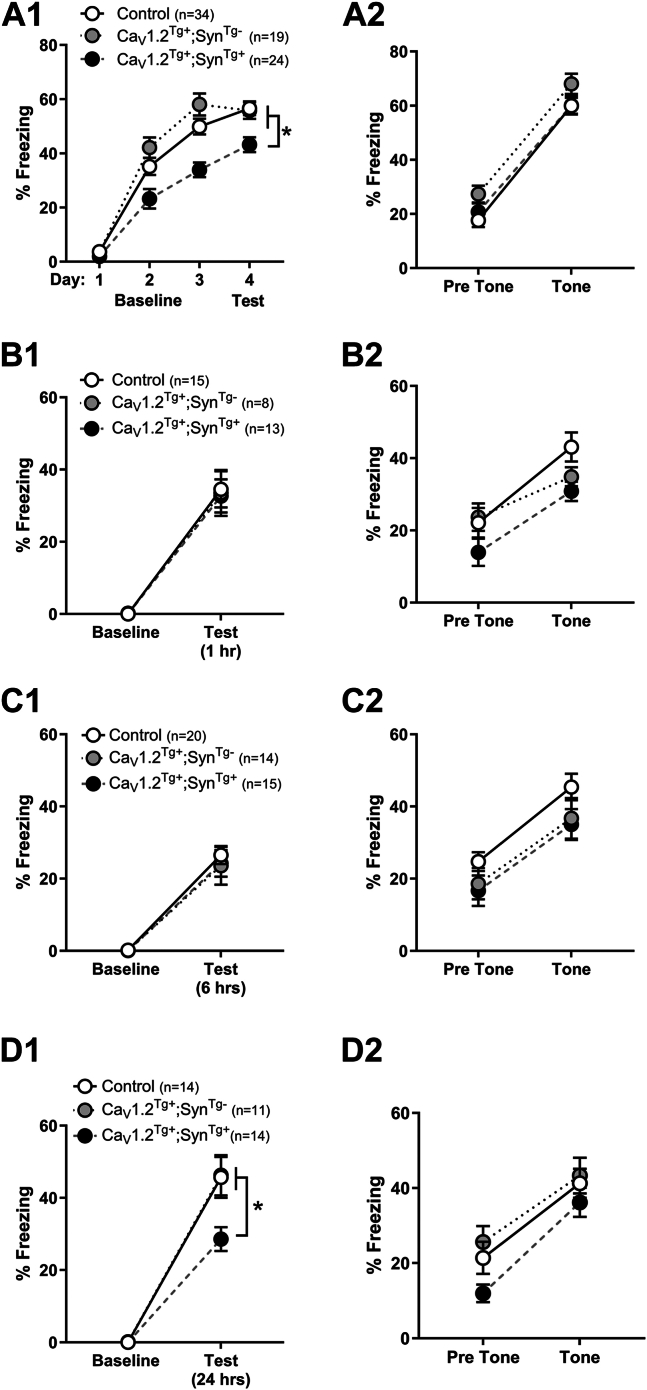

Overexpression of CaV1.2 Disrupts the Consolidation of Contextual Fear Memories

Consistent with their putative role in neuropsychiatric disease, disrupting LVGCC function or expression has been demonstrated to impact complex behavioral states in rodent models (44). For example, we have demonstrated that pan-neuronal deletion of Cacna1c produces deficits in context discrimination (45), the extinction of fearful memories, and excitatory/inhibitory tone within the amygdala (46). However, the impact of overexpression of Cacna1c on the acquisition and consolidation of fearful memories has not yet been investigated. Therefore, a series of fear conditioning experiments was conducted similar to our previous work (45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53). Training took place for 3 days. Mice were placed individually into fear conditioning chambers for 3 minutes (baseline), followed by a 30-second tone that coterminated with a 2-second foot shock, after which mice remained in the chambers for 30 seconds. Freezing was assessed during the 3 minutes of baseline. Following training (day 4), mice were returned to the same chambers for 5 minutes absent the tone (Figure 3A2). Analysis of freezing revealed a significant effect of genotype and day, as well as a significant interaction. Post hoc comparisons revealed no significant differences between control and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− groups; however, CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice froze significantly less than either group on training days 2 or 3, as well as the context test on day 4 (Figure 3A1).

Figure 3.

CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice exhibit deficits in memory consolidation of fearful contexts. (A1) Mice were exposed to a single tone-shock pairing each day for 3 days and subsequently returned to the same context 24 hours later, and freezing was measured in the absence of tone or shock. While all groups exhibited an increase in freezing across the 3 days of training, the CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice exhibited less freezing 24 hours after the first training session (day 2), a deficit which persisted across 3 days of training and was maintained during a context test on the fourth day (effect of training: F2.638,172.9 = 197.0, p < .0001; effect of genotype: F2,73 = 20.42, p < .0001; training × genotype interaction: F6,219 = 3.194, p = .005; post hoc analysis indicates CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ froze less than CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− and control mice on days 2, 3, and 4. ∗p < .05; Tukey). (A2) On the day following the context test, mice were placed in a novel context, and freezing was measured during a brief baseline period (pretone) and during the presentation of the same tone previously associated with the foot shock on days 1 to 3 (tone). In contrast to the deficits in memory consolidation for context, mice exhibited freezing levels similar to that observed in littermate control and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− mice (effect of training: F1,60 = 201.2, p < .0001; effect of genotype: F2,60 = 1.966, p = .1489). To determine to what extent the deficits in context conditioning were due to a failure in acquisition or memory consolidation, a series of additional experiments were performed using 3 separate cohorts of mice (B–D). Mice were placed in the training chambers, and after a brief baseline period, 3 tone-shock pairings were delivered, and after 30 seconds mice were returned to their home cage. Mice were returned to the same context in which they were trained after 1, 6, or 24 hours, and freezing was measured in the absence of tone or shock. (B1) Compared with baseline, all mice exhibited significant freezing after a 1-hour delay; however, there were no significant differences in freezing levels between the 3 genotypes (effect of training: F1,33 = 115.8, p < .0001; effect of genotype: F2,33 = 0.03593, p = .9647). (B2) All groups exhibited significant freezing during the tone presentation (effect of tone: F1,33 = 59.12, p < .0001), which did not differ significantly across the 3 genotypes (F2,33 = 2.729, p = .08). (C1) Similarly, 6 hours after training, control mice, CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg−, and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice all exhibited similar levels of freezing when returned to the training context (effect of training: F1,46 = 132.4, p < .0001; effect of genotype: F2,46 = 0.1987, p = .8205). (C2) When placed into a novel context 24 hours later, all mice exhibited robust freezing during the tone presentation that did not differ across the 3 genotypes (effect of tone: F1,46 = 52.90, p < .0001; effect of genotype: F2,46 = 2.311, p = .1105). (D1) In contrast, when returned to the same context 24 hours after a single contextual fear conditioning session, CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice exhibited less freezing than their control and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− littermates (effect of training: F1,36 = 199.3, p < .0001; effect of genotype: F2,36 = 4.323, p = .0208; training × genotype interaction: F2,36 = 4.331, p = .0206). Post hoc analysis indicates CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice froze less than CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− and control mice during the context test 24 hours after training (∗p < .01; Tukey) (D2) without exhibiting a tone condition deficit (effect of training: F1,36 = 63.62, p < .0001; effect of genotype: F2,36 = 2.760, p = .0767). All data are presented as mean ± SEM.

The following day, mice were placed into a novel context, and after a 2-minute pretone baseline period, a continuous tone (the same tone used during training) was played for 3 minutes. All genotypes exhibited similar freezing levels prior to the tone and exhibited similar increases in freezing during tone presentation (Figure 3A2).

To determine whether the impaired context conditioning was due to a deficit in acquisition or consolidation, 3 separate cohorts of mice were given a single training trial with 3 tone-shock pairings (30-second intertrial interval) and then returned to the same chambers either 1, 6, or 24 hours after training. All cohorts and genotypes exhibited similar levels of freezing during the 3-minute baseline. There was no effect of genotype in the 1-hour cohort (Figure 3B1) or the 6-hour cohort (Figure 3C1); however, all genotypes exhibited a significant increase in freezing compared with baseline. Similarly, all genotypes exhibited an increase in freezing when returned to the training context after 24 hours (cohort 3; Figure 3D1); however, CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice exhibited significantly less freezing than their CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− or control littermates (Figure 3D1). These results suggest that overexpression of CaV1.2 selectively disrupts long-term (24 hours) consolidation and not acquisition of fearful context memories. The following day (48 hours after training), mice were placed into a novel context for 2 minutes, after which a continuous tone was played for 3 minutes. Regardless of cohort, mice displayed similar levels of freezing in the new context and exhibited similar increases in freezing to the tone (Figures 3B2, 4C2, 4D2). These results, together with the apparent ability of CaV1.2Tg+ mice to acquire contextual memories, suggest that the amygdala remains functionally intact, despite significant overexpression of CaV1.2 throughout the basolateral amygdala (Figure S2). These data also suggest that overexpression of CaV1.2 does not alter pain processing (54), which we tested directly (Figure S3).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of CaV1.2 results in mild anxiolytic behavior in the absence of sensory or motor deficits. (A) Zero maze. CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice spent significantly more time in the open quadrants as a percentage of total time (5 min) on the elevated zero maze (F2,71 = 5.149, p = .0053. Significant post hoc comparisons: control × CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+, p = .0055; CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− × CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+, ∗p = .0386; Tukey). (B) Elevated plus maze: CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice spent more time in the open arms of the elevated plus maze than their control and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− littermates (F2,41 = 9.466, p = .0014. Significant post hoc comparisons: control × CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+, p = .0017; CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− × CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+, ∗p = .0136; Tukey). (C) Open field: mice were placed individually into an open field and allowed to explore for 5 minutes. There were no significant differences between groups in the total distance traveled (F2,74 = 0.0131, p = .8027) during the trial. (D) Rotarod: mice were placed onto the accelerating rotarod (1–60 rpm over 300 s) once per day for 5 days, and latency to fall was recorded. Across groups, there was a main effect of training day (F3.469,246.3 = 15.32, p < .0001) but no effect of genotype (F2,73 = 2.491, p = .0899) and no training day × genotype interaction (F8,284 = 0.4399, p = .8965). (E) Porsolt forced swim test: all 3 groups of mice exhibited similar amounts of time immobile during the forced swim test (F2,39 = 1.098, p = .8208). (F) Marble burying test: mice were placed individually into corncob bedding-filled cages that contained 24 marbles and were allowed to explore for 30 minutes. There were no significant differences between groups in the number of marbles buried during the marble burying test (F2,42 = 0.3991, p = .1646). (G) In order to assess sociability, mice were placed into an arena for 5 minutes with the option to explore either a novel mouse or an inanimate object. There were no significant differences between groups (F2,37 = 1.110, p = .4265); however, all groups preferred interaction with a novel mouse over the object, as indicated by a positive discrimination ratio (∗p < .05; 1-sample t test). (H) Short-term social memory was tested by giving the mice an option to explore either the mouse that they had previously investigated or an unfamiliar mouse. Similarly to sociability, there were no significant differences between groups (F2,32 = 0.8612, p = .2552), while all of the groups showed a preference for the novel mouse (∗p < .05; 1-sample t test). All data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Affective Behavior Is Modestly Impacted by CaV1.2 Overexpression

Altered CaV1.2 expression levels in mice have been implicated in affective behaviors resembling anxiety (55,56) [although see (46)], depression (57), and social coping (56). To examine anxiety-like behavior, mice were evaluated using the elevated zero maze (EZM) and the elevated plus maze (EPM) which were originally used to validate anxiolytic agents (58). During the EZM and EPM experiments, mice were placed on the maze and allowed to explore for 5 minutes. In the EZM and the EPM, CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice spent significantly more time in the open areas than their CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− or control littermates (Figure 4A, B).

The enhanced exploratory behavior on the EZM and EPM does not appear to be due to hyperactivity. When placed in an open field and allowed to explore for 5 minutes, the CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice traveled the same distance as the CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− and control mice (Figure 4C and Figure S4). To assess balance and motor learning, mice were placed onto an accelerating rotarod (1–60 rpm over 5 minutes) once per day for 5 days. On day 1, there were no significant differences between groups in latency to fall off the rod, indicating that CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− mice both have normal gross locomotor function (Figure 4D). Additionally, latency to fall increased to the same extent each day, indicating normal motor learning. These results indicate that the overexpression of CaV1.2 observed in the cerebellum (Figure S1A) does not alter locomotor activity or motor learning.

To evaluate the impact of CaV1.2 overexpression on depressive-like behavior (59) or stress-coping behavior (60), mice were examined in the Porsolt forced swim test (61). Mice were placed individually into a 5-L beaker filled with room temperature water and allowed to swim for 5 minutes. The amount of time that the mice spent immobile during the last 4 minutes was scored offline by a viewer blinded to the genotype. There were no significant differences between any of the groups (Figure 4E). Examining putative shared biological networks in patients diagnosed with depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) using gene-set enrichment analysis, CACNA1C has been identified as one of the 7 prominent genes (62). In mice, OCD-like behavior is often modeled using the marble-burying test (63), which has been previously reported as being altered in mice harboring a gain-of-function mutation in Cacna1c (increased inward Ca2+ current) as a model of Timothy syndrome (26). Mice were placed individually into the cages containing marbles and left to explore for 30 minutes. Any marbles that were more than two-thirds covered were considered buried and counted by a scorer blinded to the genotype. There were no significant differences between groups in the number of marbles buried, suggesting that overexpression of CaV1.2 does not alter repetitive behavior (Figure 4F).

Abnormal sociability is a prominent feature of several neuropsychiatric diseases in which CACNA1C has been implicated. Therefore, we tested sociability and short-term social recognition in the CaV1.2Tg mice. Experimental mice were placed individually into an arena containing an empty presentation chamber and a presentation chamber containing a tester mouse. Mice were allowed to explore for 5 minutes before being placed into a holding cage while a second tester mouse was placed into the previously empty chamber. After a 5-minute delay, the experimental mouse was placed back into the arena (now containing a familiar mouse from the first trial and a novel mouse in the previously empty chamber) and allowed to explore for another 5 minutes.

To assess sociability and short-term social recognition, discrimination ratios (DRs) were calculated, with a positive DR indicating a preference for the novel mouse over an inanimate object (sociability) or a familiar mouse (short-term recognition). In both the sociability test and short-term social recognition test, all groups produced a positive DR, indicating a preference for another mouse over an object (Figure 4G) and the ability to distinguish a familiar mouse from a novel one (Figure 4H) after a 5-minute delay. There were no significant differences among genotypes in either experiment indicating that overexpression of CaV1.2 does not disrupt social behavior.

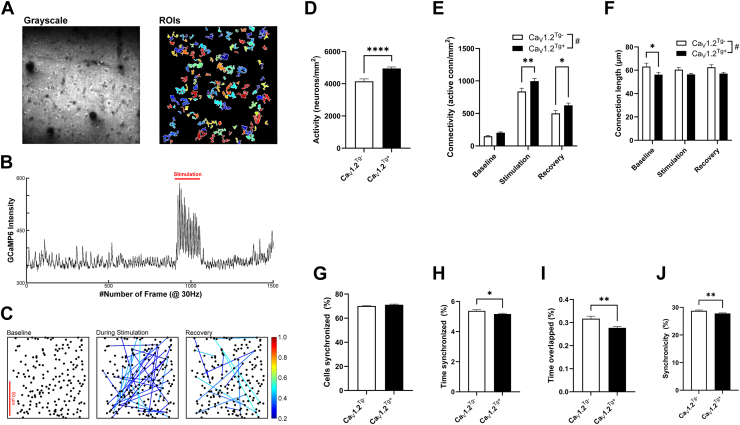

Cortical Network Dynamics Are Altered by CaV1.2 Overexpression

To determine to what extent CaV1.2 overexpression might change neuronal network dynamics, we performed in vivo 2-photon calcium imaging, as previously described (64, 65, 66). For the imaging experiments, overexpression of CaV1.2 and the expression of the calcium indicator (GCaMP6f) was confined to glutamatergic neurons by using a CaMKIIα Cre driver line (39). For the sake of simplicity, we refer to the WT (CaV1.2Tg−; GCaMP6fTg+; CaMKIITg+) mice as “CaV1.2Tg− mice” and the CaV1.2 overexpressing (CaV1.2Tg+; GCaMP6fTg+; CaMKIITg+) mice as “CaV1.2Tg+ mice.”

A representative field of view (FOV) is presented in grayscale (Figure 5A, left) with individual regions of interest (ROIs) highlighted by pseudocoloring (Figure 5A, right). Electrical stimulation of the paws (3 Hz for 5 seconds) was used to elicit digit movement, which reliably generated calcium transients in the contralateral primary somatosensory cortex (S1) (Figure 5B and Figure S5) that were used to generate network connectivity correlograms (Figure 5C) The number of active ROIs per FOV was significantly increased in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice compared with the CaV1.2Tg− mice (Figure 5D), suggesting that CaV1.2 overexpression increases the density of active neurons. Network dynamics in the S1 were evaluated by calculating the number of active connections, the length of the connections, and the synchronicity of the connections. Two neurons were considered functionally connected if the value of the correlation coefficient was >0.4 for the pair. While overexpression of CaV1.2 did not appear to impact baseline connectivity, the number of active connections was higher during stimulation and recovery than that in CaV1.2Tg− mice (Figure 5E). Furthermore, the connection length was slightly reduced in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice compared with CaV1.2Tg− mice, which was most evident during the baseline recordings (Figure 5F) and could be considered a consequence of a denser neuronal network (Figure 5D). Using Morse continuous wavelet transform function to investigate the impact of CaV1.2 overexpression on network synchronicity, correlated activity during the simulation phase was further analyzed. While there was no difference between the percentage of neurons in the FOV that were synchronized to the input frequency (Figure 5G), there were modest but statistically significant reductions in the levels of synchronized activity. There was a significant reduction in the percentage of time the neurons were synchronized to the 3-Hz stimulation (Figure 5H) and the percentage of time that identified pairs were synchronized to that frequency (Figure 5I). Finally, there was a modest reduction in the number of responses (of 15: 3 Hz for 5 seconds) during the stimulation period (Figure 5J). Taken together, the calcium imaging results suggest that overexpression of CaV1.2 results in alterations in cortical network dynamics such that the network is more dense but less synchronized.

Figure 5.

Cortical network alterations in mice that overexpress CaV1.2. (A) Representative FOV in grayscale (left) and with pseudocolored ROIs (right). (B) Raw GCaMP6 signal before, during, and after tactile stimulation during a 50-second recording. (C) Network connectivity correlogram. The size of the dot (neuron) represents the sum of that neuron’s weighted CC with all other neurons. The color of the line between 2 dots indicates the unweighted CC between that pair of neurons. Recordings were made from 6 mice in each genotype (CaV1.2Tg− = 95 FOV; CaV1.2Tg+ = 143 FOV). (D) Mice that overexpressed CaV1.2 exhibited significantly more active neurons per mm2 than their WT littermate controls (t236 = 4.67, ∗∗∗∗p = .007; unpaired t test). (E) In addition to the increase in number of active neurons in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice, the number of active connections was greater than those observed in the CaV1.2Tg− mice both during stimulation and the recovery period (effect of genotype F1,708 = 15.06, #p = .0001, ∗∗p = .005, ∗p = .041; Sidak’s). (F) Connection lengths were overall shorter in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice (F1,256 = 14.52, #p = .0002; restricted maximum likelihood), which was most apparent during the baseline period (t256 = 2.65, ∗p = .026; Sidak’s). (G–I) In contrast to the presence of more densely connected neurons, network activity in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice appeared to be less synchronized during the stimulation period. (G) The average percentage of cells that were synchronized with the 3-Hz paw stimulation was ∼70% and was not different between the 2 genotypes. (H) The percentage of time that cells in the FOV were synchronized to the input frequency was modestly reduced in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice compared with their WT littermates (t236 = 2.49, ∗p = .0134; unpaired t test). (I) Similarly, overlapping events between pairs of cells in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice was significantly reduced (t148 = 3.01, ∗∗p = .0023; t test with Welch’s correction). (J) Lastly, network synchronicity during the 3-Hz stimulation (calculated as the number of consecutive events detected divided by 15 and presented as percentage of time) was modestly reduced in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice (t236 = 2.69, ∗∗p = .008; t test). All data are presented as mean ± SEM. CC, correlation coefficient; FOV, field of view; ROI, region of interest; WT, wild-type.

Discussion

The gene that encodes the voltage-gated calcium channel CaV1.2, CACNA1C, has been identified by GWASs as being associated with psychiatric disease. The initial GWAS linked an SNP within CACNA1C (67) to BD, which was rapidly confirmed (18). Perhaps the most common reported SNP is rs1006737, which is in the third intron of CACNA1C (68). This same SNP has also been implicated in SCZ, and while there were some initial studies that failed to find an association (69), there have been a number of meta-analyses that have confirmed the link between CACNA1C rs1006737 and SCZ [e.g., (20)]. In addition, rs1006737 has been associated with MDD, for which there appears to be a gene × environment interaction with threatening life events (70).

The functional consequence of this SNP remains unclear. Most data that implicate rs100673 in altered brain function have come from neuroimaging studies (71). While the studies have not been highly consistent, there is an overarching theme that suggests a relationship between this SNP and the limbic system (72) including increased amygdala volume (73) and reduced fractional anisotropy in the hippocampus, the latter being associated with impaired working memory (74). In addition, reduced functional connectivity within the corticolimbic frontotemporal neural system during an event-related emotional face task has been reported (75).

It seems likely that the functional changes mentioned above are driven by altered expression levels of CaV1.2. Several of the best-characterized SNPs are found within areas of intron 3 that contain multiple regulatory elements, and it has been suggested that SNPs in these areas may alter the 3-dimensional genome architecture, which in turn may alter expression (28). Several studies have suggested that CaV1.2 (or its transcript) is upregulated in patients with CACNA1C risk variants (31,32,76). These reports would be consistent with a recent analysis of electronic health records that found reduced rates of psychiatric illness in individuals taking brain-permeant calcium channel blockers compared with individuals taking blockers with minimal brain penetrability (77).

While there have been numerous studies of mice [e.g., (45,46)] and rats [e.g., (78)] that have examined the impact of Cacna1c deletion on behavior and physiology, to our knowledge, this is the first report examining increased expression. Like the studies that have utilized genetic deletion of CaV1.2, the current study suggests that pan-neuronal overexpression of CaV1.2 results in a complex behavioral phenotype that impacts specific domains. Perhaps the most striking phenotype observed in the CaV1.2Tg mice is their inability to consolidate fearful memories of contexts (Figure 3). This is in contrast to the CaV1.2 conditional knockout mice, which exhibit deficits in remote memory consolidation (79), context discrimination (45), and extinction of fearful memories but not acquisition or retention at 24 hours (46). The deficits in the CaV1.2Tg mice appear to be bona fide deficits in consolidation in that the CaV1.2Tg mice exhibit freezing levels at 1 and 6 hours that are identical to their control and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− littermates (Figure 3B1, C1). Similarly, the CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg+ mice exhibited freezing levels that were like their control and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− littermates during the tone presentation in a novel context (Figure 3A2–D2). Finally, the consolidation deficits observed in the CaV1.2Tg mice are not a confound of altered sensorimotor behavior because the CaV1.2Tg mice exhibited normal levels of exploration in the open field (Figure 4C) and performed like their control and CaV1.2Tg+; SynTg− littermates on the rotorod (Figure 4D).

It has been suggested that increased CACNA1C expression may be associated with psychiatric illness; therefore, we investigated the impact of CaV1.2 overexpression on affective-like behaviors. We did not observe any significant differences in the forced swim test (Figure 4E), marble burying test (Figure 4F), sociability (Figure 4G), or social memory (Figure 4H). While imperfect, these tasks are often used to evaluate baseline levels of learned helplessness, compulsive behavior, and social coping, respectively. Taken collectively these results suggest that increased expression of CaV1.2 alone is not sufficient to recapitulate all the analogous conditions in SCZ and/or BD.

It has previously been reported that genetic ablation of Cacna1c promotes anxiety-like behavior (56). Conversely, we found that overexpression of CaV1.2 increased exploration of the open portions of the EZM and EPM (Figure 4A, B) which could be viewed as increased risk-taking behavior. These results appear to be the opposite of results from similar experiments using mice in which Cacna1c has been deleted or knocked down (80,81). While it is tempting to make a linear association based on the directionality of the effects, it is unlikely to be this simple. We have previously demonstrated that deletion of CaV1.3 produces deficits in learning (49), as does overexpression (82), suggesting that there is a nominal level of activity-dependent calcium influx and that deviations in either direction result in dysfunction.

It has been reported that CaV1.2 modulates cortical activity, which may be linked to its role in psychiatric illnesses (83). To gain some insight into how overexpression of CaV1.2 might alter network dynamics, we carried out in vivo multiphoton calcium imaging in the S1. Overexpression of CaV1.2 increased basal activity (Figure 5D). It is interesting to note that Smedler et al. (83) found that deletion of Cacna1c produced a reduction in overall activity. Furthermore, in previous work conducted in the F344 rat, an animal model of aging characterized with elevated LVGCC density (84), an increase in overall activity and connectivity in primary somatosensory neurons was reported using similar imaging and data extraction routines (65). In this work, the authors also tested the impact of the LVGCC agonist BayK-8644 on young animals and again noted significant increases in overall network activity and connectivity.

The CaV1.2Tg+ mice exhibited higher levels of connectivity (Figure 5E), which was denser (Figure 5F) than that of their CaV1.2Tg− littermates. During paw stimulation, the number of cells that were firing synchronously was similar regardless of the genotype (Figure 5G); however, cortical neurons in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice were significantly less temporally synchronized (Figure 5H–J). Taken together, these data portray a cortical subnetwork in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice as being more highly connected and less synchronized. While highly speculative, the observed lack of temporal specificity in the CaV1.2Tg+ mice is interesting in that it has been appreciated for a long time that individuals diagnosed with SCZ exhibit desynchronized oscillatory activity in response to sensory stimuli (85).

Conclusions

We have generated a novel mouse model in which CaV1.2 can be overexpressed in a cell type–specific manner. Our initial characterization suggests a complex behavioral phenotype that includes deficits in the consolidation of fearful memories and increased risk-taking behaviors, which are accompanied by altered cortical network dynamics.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

This work was supported in part by an award from the Pritzker Neuropsychiatric Disorders Research Consortium (to GGM) and the National Institutes of Health (Grant Nos. R01AG074552 and R01AG081981R01 [to GGM]; R01AG058171 [to GGM and OT]; and P01AG078116 [to OT]).

RP and GGM were responsible for conceptualization. RP was responsible for methodology. MDU was responsible for validation. RP, GGM, R-LL, and OT were responsible for formal analysis. RP, LO, HB, SLC, and R-LL were responsible for investigation. RP and GGM were responsible for writing the original draft of the article. GGM and OT were responsible for supervision. GGM was responsible for project administration. GGM and OT were responsible for funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the submitted version of the article.

We thank the University of Michigan Transgenic Animal Model Core. We thank and acknowledge the help from Austin T. Smarsh.

Some of the data herein have been published in abstract form.

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

SLC is currently affiliated with the Department of Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2025.100537.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Berger S.M., Bartsch D. The role of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 in normal and pathological brain function. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;357:463–476. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1936-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catterall W.A. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nanou E., Catterall W.A. Calcium channels, synaptic plasticity, and neuropsychiatric disease. Neuron. 2018;98:466–481. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moon A.L., Haan N., Wilkinson L.S., Thomas K.L., Hall J. CACNA1C: Association with psychiatric disorders, behavior, and neurogenesis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:958–965. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore S.J., Murphy G.G. The role of L-type calcium channels in neuronal excitability and aging. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2020;173 doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2020.107230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamponi G.W., Striessnig J., Koschak A., Dolphin A.C. The physiology, pathology, and pharmacology of voltage-gated calcium channels and their future therapeutic potential. Pharmacol Rev. 2015;67:821–870. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.009654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snutch T.P., Leonard J.P., Gilbert M.M., Lester H.A., Davidson N. Rat brain expresses a heterogeneous family of calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3391–3395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helton T.D., Xu W., Lipscombe D. Neuronal L-type calcium channels open quickly and are inhibited slowly. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10247–10251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1089-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipscombe D., Helton T.D., Xu W. L-Type calcium channels: The low down. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2633–2641. doi: 10.1152/jn.00486.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu W., Lipscombe D. Neuronal CaV1.3 α1 L-type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5944–5951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05944.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hell J.W., Westenbroek R.E., Warner C., Ahlijanian M.K., Prystay W., Gilbert M.M., et al. Identification and differential subcellular localization of the neuronal class C and class D L-type calcium channel alpha 1 subunits. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:949–962. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinnegger-Brauns M.J., Huber I.G., Koschak A., Wild C., Obermair G.J., Einzinger U., et al. Expression and 1,4-dihydropyridine-binding properties of brain L-type calcium channel isoforms. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:407–414. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Striessnig J. Voltage-Gated Ca2+-channel α1-subunit de novo missense mutations: Gain or loss of function – Implications for potential therapies. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2021;13:634760. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2021.634760. 634760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heyes S., Pratt W.S., Rees E., Dahimene S., Ferron L., Owen M.J., Dolphin A.C. Genetic disruption of voltage-gated calcium channels in psychiatric and neurological disorders. Prog Neurobiol. 2015;134:36–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhat S., Dao D.T., Terrillion C.E., Arad M., Smith R.J., Soldatov N.M., Gould T.D. CACNA1C (CaV1.2) in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;99:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orrù G., Carta M.G. Genetic variants involved in bipolar disorder, a rough road ahead. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2018;14:37–45. doi: 10.2174/1745017901814010037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ament S.A., Szelinger S., Glusman G., Ashworth J., Hou L., Akula N., et al. Rare variants in neuronal excitability genes influence risk for bipolar disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:3576–3581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424958112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira M.A.R., O’Donovan M.C., Meng Y.A., Jones I.R., Ruderfer D.M., Jones L., et al. Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/ng.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z., Chen W., Cao Y., Dou Y., Fu Y., Zhang Y., et al. An independent, replicable, functional and significant risk variant block at intron 3 of CACNA1C for schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2022;56:385–397. doi: 10.1177/00048674211009595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y.-P., Wu X., Xia X., Yao J., Wang B.-J. The genome-wide supported CACNA1C gene polymorphisms and the risk of schizophrenia: An updated meta-analysis. BMC Med Genet. 2020;21:159. doi: 10.1186/s12881-020-01084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyegaard M., Demontis D., Foldager L., Hedemand A., Flint T.J., Sørensen K.M., et al. CACNA1C (rs1006737) is associated with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:119–121. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X., Hou Z., Yin Y., Xie C., Zhang H., Zhang H., et al. CACNA1C gene rs11832738 polymorphism influences depression severity by modulating spontaneous activity in the right middle frontal gyrus in patients with major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:73. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green E.K., Grozeva D., Jones I., Jones L., Kirov G., Caesar S., et al. The bipolar disorder risk allele at CACNA1C also confers risk of recurrent major depression and of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:1016–1022. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao S., Yao Y., Zheng C., Ryan J., Mao C., Zhang F., et al. Common variants in CACNA1C and MDD susceptibility: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2016;171:896–903. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcantoni A., Calorio C., Hidisoglu E., Chiantia G., Carbone E. CaV1.2 channelopathies causing autism: New hallmarks on Timothy syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2020;472:775–789. doi: 10.1007/s00424-020-02430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bader P.L., Faizi M., Kim L.H., Owen S.F., Tadross M.R., Alfa R.W., et al. Mouse model of Timothy syndrome recapitulates triad of autistic traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15432–15437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112667108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J., Zhao L., You Y., Lu T., Jia M., Yu H., et al. Schizophrenia related variants in CACNA1C also confer risk of autism. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roussos P., Mitchell A.C., Voloudakis G., Fullard J.F., Pothula V.M., Tsang J., et al. A role for noncoding variation in schizophrenia. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1417–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fanucchi S., Shibayama Y., Burd S., Weinberg M.S., Mhlanga M.M. Chromosomal contact permits transcription between coregulated genes. Cell. 2013;155:606–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kagey M.H., Newman J.J., Bilodeau S., Zhan Y., Orlando D.A., van Berkum N.L., et al. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2010;467:430–435. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshimizu T., Pan J.Q., Mungenast A.E., Madison J.M., Su S., Ketterman J., et al. Functional implications of a psychiatric risk variant within CACNA1C in induced human neurons. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:162–169. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bigos K.L., Mattay V.S., Callicott J.H., Straub R.E., Vakkalanka R., Kolachana B., et al. Genetic variation in CACNA1C affects brain circuitries related to mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:939–945. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eckart N., Song Q., Yang R., Wang R., Zhu H., McCallion A.S., Avramopoulos D. Functional characterization of schizophrenia-associated variation in CACNA1C. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gershon E.S., Grennan K., Busnello J., Badner J.A., Ovsiew F., Memon S., et al. A rare mutation of CACNA1C in a patient with bipolar disorder, and decreased gene expression associated with a bipolar-associated common SNP of CACNA1C in brain. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:890–894. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Altier C., Dubel S.J., Barrère C., Jarvis S.E., Stotz S.C., Spaetgens R.L., et al. Trafficking of L-type calcium channels mediated by the postsynaptic scaffolding protein AKAP79. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33598–33603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang H., Fu Y., Altier C., Platzer J., Surmeier D.J., Bezprozvanny I. Ca1.2 and CaV1.3 neuronal L-type calcium channels: Differential targeting and signaling to pCREB. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2297–2310. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krueger J.N., Moore S.J., Parent R., McKinney B.C., Lee A., Murphy G.G. A novel mouse model of the aged brain: Over-expression of the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel CaV1.3. Behav Brain Res. 2017;322:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Y., Romero M.I., Ghosh P., Ye Z., Charnay P., Rushing E.J., et al. Ablation of NF1 function in neurons induces abnormal development of cerebral cortex and reactive gliosis in the brain. Genes Dev. 2001;15:859–876. doi: 10.1101/gad.862101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsien J.Z., Chen D.F., Gerber D., Tom C., Mercer E.H., Anderson D.J., et al. Subregion- and cell type-restricted gene knockout in mouse brain. Cell. 1996;87:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nath T., Mathis A., Chen A.C., Patel A., Bethge M., Mathis M.W. Using DeepLabCut for 3D markerless pose estimation across species and behaviors. Nat Protoc. 2019;14:2152–2176. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Callis J., Fromm M., Walbot V. Introns increase gene expression in cultured maize cells. Genes Dev. 1987;1:1183–1200. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madisen L., Zwingman T.A., Sunkin S.M., Oh S.W., Zariwala H.A., Gu H., et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabir Z.D., Martínez-Rivera A., Rajadhyaksha A.M. From gene to behavior: L-type calcium channel mechanisms underlying neuropsychiatric symptoms. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14:588–613. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0532-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Temme S.J., Bell R.Z., Fisher G.L., Murphy G.G. Deletion of the mouse homolog of CACNA1C disrupts discrete forms of hippocampal-dependent memory and neurogenesis within the dentate gyrus. Eurneurol 3:ENEURO. 2016:0118. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0118-16.2016. –16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Temme S.J., Murphy G.G. The L-type voltage-gated calcium channel CaV1.2 mediates fear extinction and modulates synaptic tone in the lateral amygdala. Learn Mem. 2017;24:580–588. doi: 10.1101/lm.045773.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cazares V.A., Rodriguez G., Parent R., Ouillette L., Glanowska K.M., Moore S.J., Murphy G.G. Environmental variables that ameliorate extinction learning deficits in the 129S1/SvlmJ mouse strain. Genes Brain Behav. 2019;18 doi: 10.1111/gbb.12575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKinney B.C., Chow C.Y., Meisler M.H., Murphy G.G. Exaggerated emotional behavior in mice heterozygous null for the sodium channel Scn8a (NaV1.6) Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:629–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McKinney B.C., Murphy G.G. The L-type voltage-gated calcium channel CaV1.3 mediates consolidation, but not extinction, of contextually conditioned fear in mice. Learn Mem. 2006;13:584–589. doi: 10.1101/lm.279006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKinney B.C., Sze W., White J.A., Murphy G.G. L-type voltage-gated calcium channels in conditioned fear: A genetic and pharmacological analysis. Learn Mem. 2008;15:326–334. doi: 10.1101/lm.893808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perkowski J.J., Murphy G.G. Deletion of the mouse homolog of KCNAB2, a gene linked to monosomy 1p36, results in associative memory impairments and amygdala hyperexcitability. J Neurosci. 2011;31:46–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2634-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodriguez G., Moore S.J., Neff R.C., Glass E.D., Stevenson T.K., Stinnett G.S., et al. Deficits across multiple behavioral domains align with susceptibility to stress in 129S1/SvImJ mice. Neurobiol Stress. 2020;13 doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Temme S.J., Bell R.Z., Pahumi R., Murphy G.G. Comparison of inbred mouse substrains reveals segregation of maladaptive fear phenotypes. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:282. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeon D., Kim S., Chetana M., Jo D., Ruley H.E., Lin S.-Y., et al. Observational fear learning involves affective pain system and CaV1.2 Ca2+ channels in ACC. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:482–488. doi: 10.1038/nn.2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dedic N., Pöhlmann M.L., Richter J.S., Mehta D., Czamara D., Metzger M.W., et al. Cross-disorder risk gene CACNA1C differentially modulates susceptibility to psychiatric disorders during development and adulthood. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:533–543. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kabir Z.D., Che A., Fischer D.K., Rice R.C., Rizzo B.K., Byrne M., et al. Rescue of impaired sociability and anxiety-like behavior in adult Cacna1c-deficient mice by pharmacologically targeting eIF2α. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:1096–1109. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kabir Z.D., Lee A.S., Burgdorf C.E., Fischer D.K., Rajadhyaksha A.M., Mok E., et al. Cacna1c in the prefrontal cortex regulates depression-related behaviors via REDD1. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:2032–2042. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Braun A.A., Skelton M.R., Vorhees C.V., Williams M.T. Comparison of the elevated plus and elevated zero mazes in treated and untreated male Sprague–Dawley rats: Effects of anxiolytic and anxiogenic agents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;97:406–415. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kraeuter A.-K., Guest P.C., Sarnyai Z. The Forced Swim Test for Depression-Like Behavior in Rodents. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1916:75–80. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8994-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Commons K.G., Cholanians A.B., Babb J.A., Ehlinger D.G. The rodent forced swim test measures stress-coping strategy, not depression-like behavior. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8:955–960. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Porsolt R.D., Le Pichon M., Jalfre M. Depression: A new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Nature. 1977;266:730–732. doi: 10.1038/266730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hamidian S., Pourshahbaz A., Bozorgmehr A., Ananloo E.S., Dolatshahi B., Ohadi M. How obsessive–compulsive and bipolar disorders meet each other? An integrative gene-based enrichment approach. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2020;19:31. doi: 10.1186/s12991-020-00280-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Brouwer G., Fick A., Harvey B.H., Wolmarans W. A critical inquiry into marble-burying as a preclinical screening paradigm of relevance for anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorder: Mapping the way forward. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2019;19:1–39. doi: 10.3758/s13415-018-00653-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Case S.L., Lin R.-L., Thibault O. Age- and sex-dependent alterations in primary somatosensory cortex neuronal calcium network dynamics during locomotion. Aging Cell. 2023;22 doi: 10.1111/acel.13898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin R.L., Frazier H.N., Anderson K.L., Case S.L., Ghoweri A.O., Thibault O. Sensitivity of the S1 neuronal calcium network to insulin and Bay-K 8644 in vivo: Relationship to gait, motivation, and aging processes. Aging Cell. 2022;21 doi: 10.1111/acel.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sompol P., Gollihue J.L., Weiss B.E., Lin R.L., Case S.L., Kraner S.D., et al. Targeting astrocyte signaling alleviates cerebrovascular and synaptic function deficits in a diet-based mouse model of small cerebral vessel disease. J Neurosci. 2023;43:1797–1813. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1333-22.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sklar P., Smoller J.W., Fan J., Ferreira M.A., Perlis R.H., Chambert K., et al. Whole-genome association study of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:558–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baker M.R., Lee A.S., Rajadhyaksha A.M. L-type calcium channels and neuropsychiatric diseases: Insights into genetic risk variant-associated genomic regulation and impact on brain development. Channels (Austin) 2023;17 doi: 10.1080/19336950.2023.2176984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hori H., Yamamoto N., Fujii T., Teraishi T., Sasayama D., Matsuo J., et al. Effects of the CACNA1C risk allele on neurocognition in patients with schizophrenia and healthy individuals. Sci Rep. 2012;2:634. doi: 10.1038/srep00634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao M., Yang J., Qiu X., Yang X., Qiao Z., Song X., et al. CACNA1C rs1006737, threatening life events, and gene–environment interaction predict major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:982. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Janiri D., Kotzalidis G.D., di Luzio M., Giuseppin G., Simonetti A., Janiri L., Sani G. Genetic neuroimaging of bipolar disorder: A systematic 2017–2020 update. Psychiatr Genet. 2021;31:50–64. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wessa M., Linke J., Witt S.H., Nieratschker V., Esslinger C., Kirsch P., et al. The CACNA1C risk variant for bipolar disorder influences limbic activity. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:1126–1127. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lancaster T.M., Foley S., Tansey K.E., Linden D.E.J., Caseras X. CACNA1C risk variant is associated with increased amygdala volume. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;266:269–275. doi: 10.1007/s00406-015-0609-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dietsche B., Backes H., Laneri D., Weikert T., Witt S.H., Rietschel M., et al. The impact of a CACNA1C gene polymorphism on learning and hippocampal formation in healthy individuals: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuroimage. 2014;89:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang F., McIntosh A.M., He Y., Gelernter J., Blumberg H.P. The association of genetic variation in CACNA1C with structure and function of a frontotemporal system. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:696–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Allen O., Coombes B.J., Pazdernik V., Gisabella B., Hartley J., Biernacka J.M., et al. Differential serum levels of CACNA1C, circadian rhythm and stress response molecules in subjects with bipolar disorder: Associations with genetic and clinical factors. J Affect Disord. 2024;367:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.08.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Colbourne L., Harrison P.J. Brain-penetrant calcium channel blockers are associated with a reduced incidence of neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:3904–3912. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01615-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gasalla P., Manahan-Vaughan D., Dwyer D.M., Hall J., Méndez-Couz M. Characterisation of the neural basis underlying appetitive extinction & renewal in Cacna1c rats. Neuropharmacology. 2023;227 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2023.109444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.White J.A., McKinney B.C., John M.C., Powers P.A., Kamp T.J., Murphy G.G. Conditional forebrain deletion of the L-type calcium channel Ca V1.2 disrupts remote spatial memories in mice. Learn Mem. 2008;15:1–5. doi: 10.1101/lm.773208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee A.S., Ra S., Rajadhyaksha A.M., Britt J.K., De Jesus-Cortes H., Gonzales K.L., et al. Forebrain elimination of Cacna1c mediates anxiety-like behavior in mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1054–1055. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Loganathan S., Menegaz D., Delling J.P., Eder M., Deussing J.M. Cacna1c deficiency in forebrain glutamatergic neurons alters behavior and hippocampal plasticity in female mice. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14:421. doi: 10.1038/s41398-024-03140-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moore S.J., Cazares V.A., Temme S.J., Murphy G.G. Age-related deficits in neuronal physiology and cognitive function are recapitulated in young mice overexpressing the L-type calcium channel, CaV 1.3. Aging Cell. 2023;22 doi: 10.1111/acel.13781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smedler E., Louhivuori L., Romanov R.A., Masini D., Dehnisch Ellström I., Wang C., et al. Disrupted Cacna1c gene expression perturbs spontaneous Ca2+ activity causing abnormal brain development and increased anxiety. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2108768119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thibault O., Landfield P.W. Increase in single L-type calcium channels in hippocampal neurons during aging. Science. 1996;272:1017–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hirano Y., Uhlhaas P.J. Current findings and perspectives on aberrant neural oscillations in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;75:358–368. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.