Abstract

The self-assembly of a new class of coordination cages formed from two tetrapyridyl-substituted cavitands connected through four square-planar palladium or platinum complexes is reported. The shape of the internal cavity resembles an ellipsoid with a calculated volume of 840 Å3. The four lateral portals have a diameter of about 6 Å, large enough to allow the fast entrance/egress of counterions in solution. The platinum cages 3a,e cannot be disassembled using triethylamine as competitive ligand and they are kinetically stable at room temperature, whereas the palladium cages 3b-d, 3f-h are disassembled and kinetically labile under the same conditions. The different solubility properties of the cage components have allowed the extension of this self-assembly protocol to the liquid–liquid interface.

Keywords: cavitands

Metal-directed self-assembly has been widely used to construct three-dimensional structures presenting internal cavities of molecular dimensions, capable of trapping ions and neutral molecules (1, 2). The ability of such container molecules to confine (3) and stabilize (4) their guests makes them particularly attractive for many potential applications ranging from catalysis (5, 6) to nanotechnology (for self-assembly in nanotechnology, see ref. 7; ref. 8). Specifically, surface-controlled self-assembly is rapidly emerging as a valuable tool for the generation of complex structures directly on solid supports (9–11). Unlike the covalent approach used for carcerands synthesis (12), the thermodynamic control of the process conveys interesting features, among which reversibility (13), selection (14), and self-repairing properties are the most interesting.

Cavitand-based coordination cages are receiving increasing attention because of the versatility of cavitand platforms in terms of preorganization and synthetic modularity (15–20). Strong metal–ligand interactions are necessary to operate cage self-assembly (CSA) in a wide range of solvents, to extend further these self-assembly protocols to solid–liquid and liquid–liquid interfaces.

For this purpose we designed and synthesized new cavitands bearing pyridines (for references on cages derived from multidentate pyridine ligands, see ref. 21; refs. 22 and 23) instead of nitriles (24) at the upper rim as ligands for the coordination to the metal centers. CSA requires a cavitand with four pyridines preorganized in a diverging spatial orientation, pointing outward (o) the cavity, being designated the oooo isomer (for in/out isomerism in cavitands, see ref. 25).

Materials and Methods

General.

All commercial reagents were ACS reagent grade and used as received. All solvents were dried over 3- and 4-Å molecular sieves. Resorcinarenes 1a,b were prepared according to the literature (26). Metal precursors were prepared from the corresponding dichlorobis derivatives following established procedures (27–29). 1H NMR were recorded on Bruker (Billerica, MA) AC300 (300 MHz) and AMX400 (400 MHz) spectrometers and all chemical shifts (δ) were reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to the proton resonances resulting from incomplete deuteration of the NMR solvents. 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AC300 (75 MHz) spectrometer. 31P NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker XP200 (81 MHz), and all chemical shifts were reported in ppm relative to external 85% H3PO4 at 0.00 ppm. 19F NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker XP200 (188 MHz) spectrometer, and all chemical shifts were reported relative to external CFCl3 at 0.00 ppm. Melting points were obtained with an electrothermal capillary melting points apparatus and are uncorrected. Mass spectra of the organic compounds were measured with a Finnigan-MAT (San Jose, CA) SSQ 710 spectrometer, using the CI (chemical ionization) technique. Electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS experiments were performed on a Perkin–Elmer API 100 SCIEX spectrometer equipped with an ionospray interface. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectra were obtained on a PerSeptive Biosystems (Framingham, MA) Voyager DE-RP spectrometer equipped with delayed extraction. HPLC chromatography was performed using a semipreparative HPLC S10 Nitrile column on a Perkin–Elmer Series II instrument.

Cavitand 2a.

A mixture of resorcinarene 1a (R = C11H23; 0.707 g, 0.64 mmol), K2CO3 (1.06 g, 7.67 mmol) and 4-(dibromomethyl)pyridine (see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org) (1.61 g, 6.40 mmol) in 30 ml of dry N,N,-dimethylacetamide (DMA) was stirred in a sealed tube at 80°C for 15 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled, poured into a saturated Na2CO3 solution, and extracted with CH2Cl2. Removal of the CH2Cl2 gave a black solid that was purified in two steps: at first by column chromatography (SiO2, CH2Cl2/EtOH from 9:1 to 1:1), then on silica gel plates (CH2Cl2/EtOH 9:1) to give cavitand 2a in 10% yield (0.090 g, 0.06 mmol); mp 106–108°C.

1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 300 K): δ 0.88 (bt, 12H, CH3), 1.28 [m, 72H (CH2)9], 2.32 (m, 8H, CHCH2), 4.91 (t, 4H, CHCH2, J = 7.9 Hz), 5.46 (s, 4H, CHPy), 6.71 (s, 4H, ArH), 7.28 (s, 4H, ArH), 7.71 (d, 8 H, m-Py, AA′ part of an AA′XX′ system, J = 5.5 Hz), 8.72 (d, 8 H, o-Py, XX′ part of an AA′XX′ system, J = 5.5 Hz); CI-MS: m/z: 1462 (M−,100).

Cavitand 2b.

A mixture of resorcinarene 1b (R = CH2CH2Ph; 1.01 g, 1.11 mmol), K2CO3 (3.28 g, 23.73 mmol) and 4-(dibromomethyl)pyridine (4.16 g, 16.64 mmol) in 30 ml of dry DMA was stirred in a sealed tube at 80°C for 15 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled, poured into a saturated Na2CO3 solution, and extracted with CH2Cl2. Removal of the CH2Cl2 gave a black solid that was purified in two steps: at first by column chromatography (SiO2, CH2Cl2/EtOH from 9:1 to 1:1), then by HPLC (S10 Nitrile, EtOH/CH2Cl2 9:1) to give cavitand 2b in 12% yield (0.168 g, 0.13 mmol); mp 230°C (with decomposition).

1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 300 K): δ 2.62 (m, 8H, CH2CH2Ph), 2.75 (m, 8H, CH2CH2Ph), 5.04 (t, 4H, CHCH2, J = 7.8 Hz), 5.45 (s, 4H, CHPy), 6.73 (s, 4H, ArH), 7.17–7.27 (m, 20H, CH2C6H5), 7.34 (s, 4H, ArH), 7.60 (d, 8 H, m-Py, AA′ part of a AA′XX′ system, J = 4.7 Hz), 8.74 (d, 8 H, o-Py, XX′ part of an AA′XX′ system, J = 4.7 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 300 K): δ 32.1 (CH2), 34.3 (CH2), 36.5 (CH), 106.0 (CH), 116.7 (CH), 120.8 (CH), 120.9 (CH), 126.2 (CH), 128.3 (CH), 128.6 (CH), 139.0 (Cq), 141.3 (Cq), 146.1 (Cq), 150.3 (CH), 154.2 (Cq); CI-MS: m/z: 1261 (M−, 100).

Crystallographic Data for 2b.

C84H68N4O8, fw = 1261.43, orthorombic space group Pca21, a = 20.608 (5), b = 33.315 (5), c = 21.863 (5) Å, V = 15010.2 (5) Å3, ρcalcd = g/cm−3, Z = 8, λ(CuKα) = 1.54184 Å, T = 293 (2) K, θ/2θ scan technique, absorption coefficient = 0.57 mm−1. A total of 14,476 unique data with 3,878 reflections having I > 4σ(I) were collected. Index range: −12 ≤ h ≤ 25, −12 ≤ k ≤ 26, −1 ≤ l ≤ 40, range from 3.23 to 70.27°. Refinement on F2 converged to R1 = 0.098 and wR2 = 0.239.

The diffraction experiment was carried out on an Enraf Nonius CAD4

diffractometer. Data were corrected for Lorentz and polarization

effects but not for absorption effects. The structure was solved by

direct methods in the SIR92 program and

refined by full-matrix least-squares procedures, using the

SHELXL-97 system of crystallographic computer

programs. Two symmetry independent molecules were found in the

asymmetric unit. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically

with the exception of those belonging to the terminal phenyl rings; all

hydrogen atoms were taken in their calculated positions and refined

“riding” on the corresponding parent atoms; the weighting scheme

used in the last cycle of refinement was w =

1/[σ2F +

(0.0159 P)2], where P

= (F

+

(0.0159 P)2], where P

= (F +

2F

+

2F )/3. The highest peak and

the deepest hole in the final difference Fourier ΔF map were 1.081

and −0.339 eÅ−3. Molecular geometry

calculations were carried out using the PARST97

program.

)/3. The highest peak and

the deepest hole in the final difference Fourier ΔF map were 1.081

and −0.339 eÅ−3. Molecular geometry

calculations were carried out using the PARST97

program.

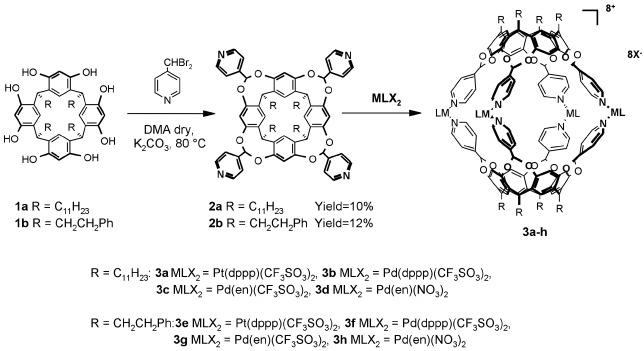

General Procedure for Cage Formation.

Cages 3a-h were assembled by simply mixing cavitands 2a and 2b with different metal precursors MLX2 [M = Pd, Pt; L = 1,3-bis(diphenylphosphino)-propane (dppp), ethylenediamine (en); X = CF3SO3, NO3] in a 1:2 molar ratio at room temperature in solvents such as CH2Cl2, CHCl3, acetone, or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). In all cases removal of the solvent in vacuo gave the desired cage in quantitative yields.

3a.

(M = Pt, L = dppp, X =

CF3SO3, R =

C11H23):

1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 300

K): δ = 0.85 (t, 24 H, CH3,

J = 6.8 Hz), 1.24–1.28 [m, 128 H

(CH2)8], 1.41

(m, 16 H,

CHCH2CH2), 2.25

(m, 24 H,

CHCH2CH2 and

Ph2PCH2CH2),

3.39 (m, 16 H,

Ph2PCH2CH2),

4.68 (t, 8 H, CHCH2, J

= 8.0 Hz), 4.96 (s, 8 H, CHPy), 6.50 (s, 8 H,

ArH), 7.10 (s, 8 H, ArH), 7.37 (d, 16 H,

m-Py, AA′ part of a AA′XX′ system, J = 6.0

Hz), 7.42 [m, 48 H,

P(C6H5)2],

7.59 [m, 32 H,

P(C6H5)2],

8.87 (d, 16 H, o-Py, XX′ part of a AA′XX′ system,

J = 6.0 Hz); 31P-NMR (81 MHz,

CDCl3) δ = −12.1, J

(Pt-P) = 3120 Hz; 19F NMR (188.3 MHz,

CD2Cl2) δ = −77.5;

ESI-MS: m/z 3122.9

[M-2CF3SO ]2+,

2032.1

[M-3CF3SO

]2+,

2032.1

[M-3CF3SO ]3+,

1486.9

[M-4CF3SO

]3+,

1486.9

[M-4CF3SO ]4+

(M =

C308H352F24N8O40S8P8Pt4).

]4+

(M =

C308H352F24N8O40S8P8Pt4).

3b.

(M = Pd, L = dppp, X =

CF3SO3, R =

C11H23):

1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 300

K): δ = 0.85 (t, 24 H, CH3,

J = 7.2 Hz), 1.22–1.25 [m, 128 H

(CH2)8], 1.39

(m, 16 H,

CHCH2CH2), 2.24

(m, 16 H,

CHCH2CH2), 2.45

(m, 8 H,

Ph2PCH2CH2),

3.27 (m, 16 H,

Ph2PCH2CH2),

4.65 (t, 8 H, CHCH2, J

= 7.9 Hz), 4.99 (s, 8 H, CHPy), 6.46 (s, 8 H,

ArH), 7.10 (s, 8 H, ArH), 7.31–7.43 [m,

64 H, m-Py, AA′ part of a AA′XX′ system and

P(C6H5)2],

7.56 [m, 32 H,

P(C6H5)2],

8.91 (bd, 16 H, o-Py, XX′ part of a AA′XX′ system);

31P-NMR (81 MHz, CDCl3)

δ = 8.8; 19F NMR (188.3 MHz,

CD2Cl2) δ = −79.8;

ESI-MS: m/z 2946.2

[M-2CF3SO ]2+,

1913.8

[M-3CF3SO

]2+,

1913.8

[M-3CF3SO ]3+

(M =

C308H352F24N8O40S8P8Pd4).

]3+

(M =

C308H352F24N8O40S8P8Pd4).

3c.

(M = Pd, L = en, X =

CF3SO3, R =

C11H23):

1H NMR (300 MHz,

acetone-d6, 300 K): δ = 0.86

(bt, 24 H, CH3), 1.26 [m, 128 H

(CH2)8], 1.38

(m, 16 H,

CHCH2CH2), 2.41

(m, 16 H,

CHCH2CH2), 3.12

(s, 16 H,

H2NCH2CH2NH2),

4.78 (t, 8 H, CHCH2, J

= 7.8 Hz), 5.25 (bs, 16 H,

H2NCH2CH2NH2),

5.37 (s, 8 H, CHPy), 7.17 (s, 8 H,

ArH), 7.68 (s, 8 H, ArH), 8.05 (d, 16 H,

m-Py, AA′ part of a AA′XX′ system, J = 6.7

Hz), 9.19 (d, 16 H, o-Py, XX′ part of a AA′XX′ system,

J = 6.7 Hz); ESI-MS: m/z

2242.6

[M-2CF3SO ]2+,

1445.5

[M-3CF3SO

]2+,

1445.5

[M-3CF3SO ]3+,

1046.9

[M-4CF3SO

]3+,

1046.9

[M-4CF3SO ]4+

(M =

C208H280F24N16O40S8Pd4).

]4+

(M =

C208H280F24N16O40S8Pd4).

3d.

(M = Pd, L = en, X = NO3, R = C11H23): 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, 300 K): δ = 0.86 (t, 24 H, CH3, J = 6.9 Hz), 1.22 [m, 128 H (CH2)8], 1.37 (m, 16 H, CHCH2CH2), 2.39 (m, 16 H, CHCH2CH2), 2.73 (s, 16 H, H2NCH2CH2NH2), 4.59 (bt, 8 H, CHCH2), 5.26 (s, 8 H, CHPy), 5.53 (bs, 16 H, H2NCH2CH2NH2), 7.20 (s, 8 H, ArH), 7.62 (s, 8 H, ArH), 8.05 (d, 16 H, m-Py, AA′ part of a AA′XX′ system, J = 5.9 Hz), 9.14 (d, 16 H, o-Py, XX′ part of a AA′XX′ system, J = 5.9 Hz).

3e.

(M = Pt, L = dppp, X =

CF3SO3, R =

CH2CH2Ph):

1H NMR (300 MHz,

CD2Cl2, 300 K): δ =

2.27 (m, 8 H,

Ph2PCH2CH2),

2.61 (m, 16 H,

CH2CH2Ph), 2.68

(m, 16 H,

CH2CH2Ph), 3.33

(m, 16 H,

Ph2PCH2CH2),

4.69 (t, 8 H, CHCH2, J

= 7.6 Hz), 4.84 (s, 8 H, CHPy), 6.54 (s, 8 H,

ArH), 7.11–7.23 (s, 48 H,

CH2CH2Ph and

ArH), 7.36–7.40 [m, 64 H, m-Py, AA′ part of a

AA′XX′ system and

P(C6H5)2],

7.57 [m, 32 H,

P(C6H5)2],

8.80 (d, 16 H, o-Py, XX′ part of a AA′XX′ system,

J = 5.3 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz,

CD2Cl2, 300 K): δ 30.0

(dppp CH2), 30.9 (dppp

CH2), 32.0 (CH2), 34.2

(CH2), 36.2 (CH), 104.1 (CH), 117.0 (CH), 121.2

(q, CF3, J = 320 Hz), 121.5 (CH),

123.6 (dppp Cq), 125.8 (CH), 126.5 (CH), 128.8 (CH), 128.9 (CH), 130.0

(dppp CH), 133.0 (dppp CH), 133.2 (dppp CH), 138.8 (Cq), 141.9 (Cq),

146.1 (Cq), 150.3 (CH), 154.2 (Cq); 31P-NMR (81

MHz, CD2Cl2) δ =

−12.9, J (Pt-P) = 30,96 Hz; ESI-MS:

m/z 2921.9

[M-2CF3SO ]2+,

1898.2

[M-3CF3SO

]2+,

1898.2

[M-3CF3SO ]3+,

1386.6

[M-4CF3SO

]3+,

1386.6

[M-4CF3SO ]4+

(M =

C284H240F24N8O40S8P8Pt4).

]4+

(M =

C284H240F24N8O40S8P8Pt4).

3f.

(M = Pd, L = dppp, X =

CF3SO3, R =

CH2CH2Ph):

1H NMR (300 MHz,

CD2Cl2, 300 K): δ =

2.40 (m, 8 H,

Ph2PCH2CH2),

2.65 (m, 16 H,

CH2CH2Ph), 2.74

(m, 16 H,

CH2CH2Ph), 3.27

(m, 16 H,

Ph2PCH2CH2),

4.75 (t, 8 H, CHCH2, J

= 7.7 Hz), 4.93 (s, 8 H, CHPy), 6.57 (s, 8 H,

ArH), 7.15–7.25 (s, 48 H,

CH2CH2Ph and

ArH), 7.38–7.43 [m, 64 H, m-Py, AA′ part of a

AA′XX′ system and

P(C6H5)2],

7.59 [m, 32 H,

P(C6H5)2],

8.85 (d, 16 H, o-Py, XX′ part of a AA′XX′ system,

J = 6.0 Hz); 31P-NMR (81 MHz,

CD2Cl2) δ = 9.4;

19F NMR (188.3 MHz,

CD2Cl2) δ = −77.3;

ESI-MS: m/z 2745.3

[M-2CF3SO ]2+,

1780.6

[M-3CF3SO

]2+,

1780.6

[M-3CF3SO ]3+,

1298.1

[M-4CF3SO

]3+,

1298.1

[M-4CF3SO ]4+

(M =

C284H240F24N8O40S8P8Pd4).

]4+

(M =

C284H240F24N8O40S8P8Pd4).

3g.

(M = Pd, L = en, X =

CF3SO3, R =

CH2CH2Ph): NMR (300 MHz,

acetone-d6, 300 K): δ = 2.82

(m, 16 H,

CH2CH2Ph), 2.85

(m, 16 H,

CH2CH2Ph), 3.17

(m, 16 H.

H2NCH2CH2NH2),

4.89 (bt, 8 H, CHCH2), 5.30 (bs, 16 H,

H2NCH2CH2NH2),

5.45 (s, 8 H, CHPy), 7.20–7.24 (m, 40 H,

CH2CH2Ph), 7.30 (s, 8

H, ArH), 7.83 (s, 8 H, ArH), 8.12 (d, 16 H,

m-Py, AA′ part of a AA′XX′ system, J = 6.6

Hz), 9.25 (d, 16 H, o-Py, XX′ part of a AA′XX′ system,

J = 6.6 Hz); ESI-MS: m/z

2042.2

[M-2CF3SO ]2+,

1312.1

[M-3CF3SO

]2+,

1312.1

[M-3CF3SO ]3+,

946.8

[M-4CF3SO

]3+,

946.8

[M-4CF3SO ]4+

(M =

C184H168F24N16O40S8Pd4).

]4+

(M =

C184H168F24N16O40S8Pd4).

3h.

(M = Pd, L = en, X = NO3, R =

CH2CH2Ph): NMR (300 MHz,

DMSO-d6, 300 K): δ = 2.67 (m,

16 H, CH2CH2Ph),

2.71–2.76 (m, 32 H,

CH2CH2Ph and

H2NCH2CH2NH2),

4.71 (t, 8 H, CHCH2, J

= 6.85 Hz), 5.32 (s, 8 H, CHPy), 5.52 (bs, 16 H,

H2NCH2CH2NH2),

7.15–7.22 (m, 40 H,

CH2CH2Ph), 7.23 (s, 8

H, ArH), 7.71 (s, 8 H, ArH), 8.07 (d, 16 H,

m-Py, AA′ part of a AA′XX′ system, J = 6.3

Hz), 9.14 (d, 16 H, o-Py, XX′ part of a AA′XX′ system,

J = 6.3 Hz). MALDI-MS:

[M-NO ]+ (M =

C176H168N24O40Pd4)

calculated 3623.09 m/z, found 3623.5

m/z.

]+ (M =

C176H168N24O40Pd4)

calculated 3623.09 m/z, found 3623.5

m/z.

Results

The synthesis of these deep-cavity cavitands (30–32), of general structure 2a-b, was performed by bridging the corresponding resorcinarenes with 4-(α,α′-dibromomethyl)pyridine (Scheme S1). In all cases the low yields (10–12%) of the desired (oooo) isomer are due to the competitive formation of useless isomers having one (iooo) or two (iioo, ioio) pyridyl groups pointing inward (i) the cavity (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). The correct stereochemical assignment of the oooo isomer has been confirmed by the x-ray crystal structure of cavitand 2b. X-ray structure analysis reveals that the cavitand exists in two slightly different conformations. The dihedral angles between the least-squares plane through the bridging CH groups and the planes of the benzene rings of the resorcinarene skeleton [109.3(3), 123.9(3), 129.3(3), and 109.5(2) in one molecule, and 118.4(3), 116(4(3), 118.5(3), and 118.0(3) in the other] indicate that the former is in the “pinched cone” conformation and the latter is in a more regular “cone” conformation (Fig. 1 Left). In both cavitands the terminal phenethyl chains are affected by high thermal motion and static disorder.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the cavitand ligands 2a-b and self-assembly of cages 3a-h.

Figure 1.

(Left) X-ray crystal structure of the phenethyl cavitand 2b. (Right) The average α angle is 42°, close to the ideal 45° value for cage formation through four square planar complexes; the gray ellipsoid represents the internal cavity volume whose principal axes are a = 11.69 Å, b = 5.86 Å, c = 11.69 Å (calculated from the spartan minimized structure of Fig. 5).

From the crystal structure of the tetradentate cavitand it is possible to evaluate the α angle of the pyridyl ligands relative to the C4v symmetry axis (Fig. 1 Right): the estimated value is 42°, close to the ideal value of 45° required for the formation of strainless square-planar complexes. Therefore the cavitand ligand is correctly preorganized for CSA.

The typical procedure for cage formation is shown in the case of

cavitands 2a and 2b and various metal precursors

MLX2 (M = Pd, Pt; L = dppp, en; X

= CF3SO3,

NO3; Scheme S1): by mixing the two components in a

1:2 molar ratio at room temperature in solvents like

CH2Cl2,

CHCl3, acetone, or DMSO, cages 3a-h

were obtained in quantitative yields. In all cases

1H NMR spectra showed the formation of a new set

of signals, indicative of the presence of a single highly symmetric

compound (D4h symmetry). The downfield shift of

the pyridine protons ortho to the N is indicative of coordination to

the metal, whereas up field shift of the CH pointing inside

the cavity is diagnostic of cage formation. 31P

NMR spectra exhibited sharp singlets, with appropriate Pt satellites

for Pt complexes 3a and 3e, indicating the

equivalence of the eight dppp phosphorus atoms, thus confirming the

high symmetry of the cages. No permanent inclusion of triflate

counterions was detected by 19F NMR. Additional

evidence of cage formation was obtained through ESI-MS, which showed

prominent [M-2X−]2+,

[M-3X−]3+ for most of

the cages formed; the molecular ions could not be detected because

their molecular weight exceeded the limit of the instrument. In the

case of 3h the MALDI-TOF spectrum has been

recorded, showing the

[M-NO ]+ molecular ion at

3623.5 m/z.

]+ molecular ion at

3623.5 m/z.

Strong cooperativity in CSA has been evidenced via 1H NMR (Fig. 2): adding 1 eq of Pt(dppp)(CF3SO3)2 to a solution of cavitand 2a led to the formation of a 1:1 mixture of Pt-cage and free cavitand. After addition of the second equivalent of metal precursor the 1H NMR spectrum showed the signals of the cage as the only product. The same behavior has been observed in the case of cavitand 2b plus Pd(en)(NO3)2 in DMSO-d6 as solvent (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Self-assembly of cage 3a monitored by means of 1H NMR. (a) spectral window of cavitand 2a in CDCl3. (b) 1:1 mixture of free cavitand ligand (L) and cage (C) after addition of 1 eq Pt(dppp)(CF3SO3)2. (c) Cage 3a as single product after addition of 2 eq of Pt(dppp)(CF3SO3)2.

Figure 3.

Self-assembly of cage 3h monitored by means of 1H NMR. (a) spectrum of cavitand 2b in DMSO-d6. (b) Mixture of free cavitand ligand (L) and cage (C) after addition of slightly less than 1 eq of Pd(en)(NO3)2. (c) Cage 3h as single product after addition of 2 eq of Pd(en)(NO3)2.

The robustness of the M-Py coordination allowed us to perform CSA in

polar and competitive solvents like DMSO or acetonitrile, where the

nitrile-based coordination cages immediately decompose (24). The

solubility properties of cages 3a-h can be tuned by

appropriately choosing counterion, chelating ligand and R substituents

at the lower rim of the cavitand ligand. In particular the solubility

of the cages in DMSO or even in DMSO/H2O

mixtures (up to 3:1 ratio) has been achieved, introducing the highly

hydrophilic NO counterion as in the case of

3d and 3h. The different solubility properties of

the cage components have been exploited to perform CSA in a

liquid–liquid two-phase system. In a typical experiment cavitand

2b (1 eq) dissolved in 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane was exposed

to an aqueous solution of

Pd(en)(NO3)2 (2.5 eq) in a

test tube (Fig. 4). Immediately, a solid

formed at the interface, which became more abundant over time.

1H NMR analysis of the recovered solid indicated

the formation of cage 3h in pure form. A MALDI-TOF

experiment performed directly on the solid sample confirmed the

attribution, ruling out the possibility of the formation of a

sheet-like network at the

interface.§ This

last result is particularly interesting because liquid–liquid

interfaces represent another potentially useful field of action for

self-assembly protocols, which has barely been explored so far (33).

counterion as in the case of

3d and 3h. The different solubility properties of

the cage components have been exploited to perform CSA in a

liquid–liquid two-phase system. In a typical experiment cavitand

2b (1 eq) dissolved in 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane was exposed

to an aqueous solution of

Pd(en)(NO3)2 (2.5 eq) in a

test tube (Fig. 4). Immediately, a solid

formed at the interface, which became more abundant over time.

1H NMR analysis of the recovered solid indicated

the formation of cage 3h in pure form. A MALDI-TOF

experiment performed directly on the solid sample confirmed the

attribution, ruling out the possibility of the formation of a

sheet-like network at the

interface.§ This

last result is particularly interesting because liquid–liquid

interfaces represent another potentially useful field of action for

self-assembly protocols, which has barely been explored so far (33).

Figure 4.

Cage formation at the water/organic solvent interface.

Several attempts of determining the crystal structure of cages 3e,g failed repeatedly because of the total absence of any diffraction pattern, although the crystals were well formed and shaped. This led us to undertake a computational approach to study the molecular properties of the cage.

Theoretical calculations [the calculations were carried in vacuo by using spartan (PC Spartan Pro, Version 1.05, Wavefunction, Irvine, CA)] performed on 3g indicate that the cage is squeezed in the polar regions (Fig. 5), embracing a wide cavity that can be fitted by an ellipsoid of rotation whose principal axes (at the van der Waals limits) are a = 11.69 Å, b = 5.86 Å, and c = 11.69 Å (Fig. 1 Right), corresponding to a total available volume of nearly 840 Å3.¶ This estimate is conservative because it does not take into account the residual space of the resorcinarene caps. The cavity can be accessed through the four large circular lateral portals, of approximate diameter of 6 Å, large enough to allow the entrance/egress of solvent molecules and triflate anions, in accordance with 19F NMR experiments. The calculated Pd-N(Py) bond distances range from 2.028 to 2.035 Å, those of Pd-N(en) from 2.017 to 2.020 Å, in agreement with the values observed in the solid state (35, 36). The torsion angles C-C-N-Pd involving the pyridine atoms (from 165 to 170°), as well as the N(Py)-Pd-N(Py) bond angles (from 85.6 to 88.8°) and those of N(en)-Pd-N(en) (from 92.7 to 95.4°), indicate a distortion in the coordination sphere at the Pd metal centers.

Figure 5.

Computer modeling of cage 3g (the phenethyl chains at the lower rim are omitted).

Several attempts to disassemble Pt and Pd cages were performed. Pd cage 3b was disassembled into its cavitand component and [Pd(dppp)(NEt3)2(CF3SO3)2] in the presence of an excess of NEt3 as competitive ligand (32 eq) at 323 K (Fig. 6), whereas, under the same conditions, the 1H NMR spectrum of the corresponding Pt cage 3a remained unchanged. This finding is consistent with the greater Pt-N bond strength with respect to the Pd-N one.

Figure 6.

(a) Cage 3b in the presence of an excess of NEt3 at 300 K. (b) Partial disassembly of the cage (C) into its cavitand component (L) after heating at 323 K for a few minutes.

The kinetic stability of the Pt cages has been assessed by means of ESI-MS.‖ A ligand-exchange experiment was performed starting from two Pt-cages 3a and 3e different for the chains at the lower rim (R = C11H23 and CH2CH2Ph): both cages were separately analyzed by means of ESI-MS, showing [M-2CF3SO3]2+, [M-3CF3SO3]3+, and [M-4CF3SO3]4+ ions. Then they were mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio at room temperature, giving a spectrum resulting from the simple addition of the signals owing to the two homocages. On heating the mixture, the ESI-MS spectrum exhibited a third set of peaks belonging to the heterocage in a statistic 1:2:1 ratio with the signals of the homocages (see Figs. 8–10, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

In summary the introduction of four pyridine groups at the upper rim of a cavitand ligand in a preorganized diverging orientation has allowed the self-assembly of a series of new coordination cages, embracing an internal cavity of approximately 840 Å3. The robustness of the pyridine–metal coordinative bond has been exploited to perform CSA in highly polar solvents, precluded to the first generation of cavitand-based coordination cages bearing nitrile moieties (24). Kinetically the platinum cages are stable at room temperature both in polar and apolar solvents. The extension of the CSA protocol to liquid–liquid interfaces is particularly appealing in view of the possible applications to surface patterning for microanalytical devices (38).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Use was made of instrumental facilities at the Centro Interfacoltà di Misure G. Casnati of the University of Parma. Special thanks to R. Fokkens (Supramolecular Chemistry and Technology Laboratory, University of Twente) for the MALDI-TOF measurements. This work was supported by Centro Nazionale delle Ricerche (Nanotechnology Project).

Abbreviations

- CSA

cage self-assembly

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- dppp

1,3-bis(diphenylphosphino)-propane

- en

ethylenediamine

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight

Footnotes

Dynamic interconversion of similar square-planar Pd(II) complexes with pyridyl cycloveratrylenes has been shown by Shinkai et al. (37) to occur at room temperature.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Cambridge Structural Database, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, United Kingdom (CSD reference no. CCDC-167027).

In principle a sheet-like network that contains both components in a 2:1 ratio could also form at the interface and subsequently rearrange into cage 3h on dissolution in DMSO. We thank one reviewer for having suggested this possibility.

The geometry of the cationic complex has been optimized in vacuo at the semiempirical PM3 level (34).

References

- 1.Caulder D L, Raymond K N. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:975–982. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leininger S, Olenyuk B, Stang P J. Chem Rev. 2000;100:853–908. doi: 10.1021/cr9601324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jasat A, Sherman J C. Chem Rev. 1999;99:931–967. doi: 10.1021/cr960048o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Warmuth, R. (2001) Eur. J. Org. Chem. 423–437.

- 5.Kang J, Rebek J., Jr Nature (London) 1997;385:50–52. doi: 10.1038/385050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshizawa M, Kusukawa T, Fujita M, Yamaguchi K. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6311–6312. doi: 10.1021/ja010875t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Service R F. Science. 2000;290:1523–1531. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Service R F. Science. 2001;293:782–785. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5531.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissbuch I, Baxter P N W, Cohen S, Cohen H, Kjaer K, Howes P B, Als-Nielsen J, Hanan G S, Schubert U S, Lehn J-M, Leiserowitz L, Lahav M. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:4850–4860. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatzor A, Moav T, Cohen H, Matlis S, Libman J, Vaskevich A, Shanzer A, Rubinstein I. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:13469–13477. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levi S A, Guatteri P, van Veggel F C J M, Vancso G J, Dalcanale E, Reinhoudt D N. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:1892–1896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cram D J, Cram J M. Container Molecules and Their Guests. Cambridge, U.K.: R. Soc. Chem.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebek J., Jr Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:278–286. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hof F, Nuckolls C, Rebek J., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4251–4252. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacopozzi P, Dalcanale E. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1997;36:613–615. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox D O, Dalley N K, Harrison R G. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7111–7112. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox D O, Dalley N K, Harrison R G. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:5860–5863. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox O D, Drew M G B, Beer P D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:136–140. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000103)39:1<135::aid-anie135>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuminetti N, Ebbing M H K, Prados P, de Mendoza J, Dalcanale E. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:527–530. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park, S. J. & Hong, J.-I. (2001) Chem. Commun. 1554–1555. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Fujita M, Nagao S, Ogura K. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:1649–1650. doi: 10.1021/ja00110a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ikeda, A., Yoshimura, M., Tani, F., Naruta, Y. & Shinkai, S. (1998) Chem. Lett. 587–588.

- 23.Zhong Z, Ikeda A, Ayabe M, Shinkai S, Sakamoto S, Yamaguchi K. J Org Chem. 2001;66:1002–1008. doi: 10.1021/jo0011686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fochi F, Jacopozzi P, Wegelius E, Rissanen K, Cozzini P, Marastoni E, Fisicaro E, Manini P, Fokkens R, Dalcanale E. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7539–7552. doi: 10.1021/ja0103492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lippmann T, Wilde H, Dalcanale E, Mavilla L, Mann G, Heyer U, Spera S. J Org Chem. 1995;60:235–242. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tunstad L M, Tucker J A, Dalcanale E, Weiser J, Bryant J A, Sherman J C, Helgeson R C, Knobler C B, Cram D J. J Org Chem. 1989;54:1305–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fallis S, Anderson G K, Rath N P. Organometallics. 1991;10:3180–3184. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stang P J, Cao D H, Saito S, Arif A M. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:6273–6283. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujita M, Yazaki J, Ogura K. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:5645–5647. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xi, H., Gibb, C. L. D., Stevens, E. D. & Gibb, B. C. (1998) Chem. Commun. 1743–1744.

- 31. Rudkevich, D. M. & Rebek, J., Jr. (1999) Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1991–2005.

- 32.Green J O, Baird J-H, Gibb B C. Org Lett. 2000;2:3845–3848. doi: 10.1021/ol006569m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowden N, Terfort A, Carbeck J, Whitesides G M. Science. 1997;276:233–235. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart J P J. J Computational Chem. 1989;10:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siedle A R, Pignolet L H. Inorg Chem. 1982;21:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tebbe K-F, Grafe-Kavoosian A, Freckmann B. Z Naturforsch, B. 1996;51:999–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong Z, Ikeda A, Shinkai S, Sakamoto S, Yamaguchi K. Org Lett. 2001;3:1085–1087. doi: 10.1021/ol0157205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kenis P J A, Ismagilov R F, Whitesides G M. Science. 1999;285:83–85. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.