Abstract

As one of the interruption management strategies, using information cues can effectively mitigate the sequential task performance decline caused by task interruptions. However, how to use information cues to optimize post-interruption performance in a concurrent multitasking environment is still unknown. This study analyzed the effects of retrieval cue (a cue that points towards the last action before interruption) and assistant cue (a cue that points towards the next action after interruption) on interrupted task performance in the concurrent multitasking environment through two experiments. The effects of cues on different levels of personnel fatigue were further investigated using electroencephalography (EEG). The results show that assistant cues effectively improve concurrent multitasking interruptions, with a more significant impact observed in the presence of fatigue. Retrieval cues do not enhance the performance of interrupted tasks but can reduce the operator workload and improve alertness. The findings provide valuable insights for managing interruptions in concurrent multitasking environments.

Keywords: Task interruption, Interruption management, Information cues, Mental fatigue, EEG

Subject terms: Human behaviour, Neurophysiology, Information technology

Introduction

Concurrent multitasking involving human–computer interactions (HCI) has become increasingly complex. Operating a complex system requires operators to focus on multiple subtasks simultaneously1, such as docking by astronauts and operation monitoring of operators in the control room of nuclear power plants and reprocessing plants. Eyal Ophir2 discovered that people are not as proficient at multitasking as they believe. Moreover, the increasing prevalence of task interruptions in HCI scenarios has further exacerbated these challenges3. Typical examples include train operators who must simultaneously handle dispatch command reception and passenger communication responses while controlling trains, as well as nuclear power plant operators who need to address emergent alarm notifications while conducting routine monitoring operations. These interruptions, particularly alarm signals and communication tasks, are usually unplanned and unexpected4. They disrupt operators’ primary workflow, which forces abrupt shifts in attentional focus5, resulting in distraction and diminished attentional capacity. Given that human cognitive capabilities remain fundamentally constrained despite technological advancements, such interruptions amplify cognitive decision-making pressure6. Prolonged exposure to such high cognitive load induces mental fatigue. It manifests as degraded task performance, diminished situational awareness, reduced vigilance, delayed behavioral responses, and increased human error7,8. Therefore, operators in complex human–machine systems must simultaneously contend with three interrelated challenges: concurrent multitasking demands, disruptive task interruptions, and cumulative mental fatigue.

Among these challenges, task interruption is particularly critical due to its unique characteristics. Understanding the core characteristics of interruptions helps to clarify their impacts and management strategies. A critical distinction of task interruption lies in its inherent workflow disruption requiring resumption of primary tasks after interruption, a characteristic that differentiates it from task switching1. Task switching refers to transitions between predefined tasks. When performing concurrent multitasking, changing between multiple subtasks can be referred to as task switching. In contrast, task interruption constitutes unscheduled action suspension that superimposes new task demands on ongoing activities, enforcing a mandatory sequential structure of primary task, interrupting task, and primary task recovery. The time spent on one task before switching to another is also different for task interruption and task switching9.

Given the disruptive nature of task interruptions on workflow, their negative impacts are widely acknowledged10,11. Most studies indicate that task interruptions impair primary task performance, primarily due to reduced memory activation of the primary task caused by interruptions12. Resuming the primary task requires overcoming interference from interruption memory and reactivating task-related memory through environmental cues, resulting in delayed recovery13. This underscores the necessity of interruption management. Interruption management refers to promoting the recovery of primary tasks to help the operator prevent or mitigate the negative impact of interruption14. McFarlane15 proposed four response strategies for task interruption: immediate, negotiated, mediated, and scheduled. Some researchers use machine learning to classify and evaluate the cognitive load of operators by collecting their physiological characteristics such as EEG, heart rate, and eye movements, and dynamically judge the strategy and time of feedback interruption to operators according to the importance of the interruption task, for example, CARSON16, Phylter17, and FeedMe18. These technologies automatically identify the source of the interruption and reduce the interruption alerts by filtering out unnecessary alerts. However, filtering or delaying the arrival of interruptions may lead to the loss of important messages and the best time to process interruptions, which is not suitable for interruptions in a concurrent multitasking environment. This study aims to explore strategies applicable to interruption management for concurrent multitasking.

Task interruption process for concurrent multitasking

To gain a deeper understanding of interruptions in concurrent multitasking environments, it is first necessary to define their unique interruption process. Trafton proposed the initial timeline of task interruption19, as depicted in Fig. 1. This interruption timeline applies to sequential tasks rather than concurrent multitasking. Addressing the specificity of concurrent multitasking environments, we propose an interruption timeline that is suitable for concurrent multitasking environment, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

The interruption and resumption process of sequential multitasking.

Fig. 2.

The task interruption process in a concurrent multitasking environment.

The concurrent multitasking interruption timeline still consists of a series of stages, and the "◇" indicates a specific key point in the interruption flow. The relevant warning signal from an external event typically triggers the alert about an interruption. Due to the importance and urgency of certain alarms, the operator is unintentionally diverted from the original primary task. Immediate interruption necessitates the operator disengaging from their current subtask and redirecting their focus to the interrupting task, regardless of its nature. The interruption lag refers to the time interval between disengagement from the primary task and the commencement of the interruption task. Typically, encoding the primary task’s current problem state occurs during this interval. The period between the cessation of the interruption task and the recommencement of the primary task is referred to as the resumption lag.

It needs to be particularly pointed out here that there exists a major distinction between concurrent multitasking interruption and sequential task interruption. Compared with a sequential task interruption, a concurrent multitasking interruption requires weighing multiple subtasks and selecting a first subtask to be resumed. Therefore, the timeline for concurrent multitasking interruptions includes subtask selection, which is essential. It affects the resumption lag after interruption and influences task performance. How to reduce the time of subtask selection after interruption is one of the key ways to help quickly resume the primary task.

Hypotheses formulation

Based on the understanding of the concurrent multitasking interruption process (especially the importance of the subtask selection phase), and the limitations of the existing interruption management strategies in the concurrent environment, this study explores the use of cues as the core strategy to improve post-interruption recovery and performance.

The role of cues in task interruption management has been preliminarily confirmed20. Falkland et al.21 demonstrated that subtle environmental cues, like cursors or images, function as position markers, reducing recovery time from interruptions. Ratwani et al. 22 found that auditory interruptions, which do not obscure the primary task screen, led to faster recovery than visual interruptions. Malin et al.23 pointed out that the user interfaces should redirect users to previously interrupted activities when they attempt to restore them. Therefore, the interface cues can provide recovery support for operators when they switch back to the original task. It could provide mechanisms to aid the operators in recalling the context of the primary task, helping the operators return more quickly to that previous task. Numerous studies on cue characteristics and usage underscore their perceptibility, contextual relevance, and timeliness24,25. Chung and Byrne25 found that providing a prominent cue immediately before the post-completion step eliminated post-completion errors. Falkland et al.21 found participants with a higher ability to utilize cues experienced less performance loss after interruptions. Thus, the cues designed for concurrent multitasking should be as prominent as possible and enhance availability.

However, most of the existing studies on the effect of cues are based on sequential task environments, and their conclusions may no longer be fully applicable in concurrent multi-task environments. Jones et al.26 found providing a cue that points to the last action taken before an interruption has equal effects on accuracy and resumption time as a cue that points to the next action in the sequence. In other words, for sequential multitasking, informing operators of what they have just done and informing them of what to do next has the same effect, which is beneficial for post-interruption recovery. However, in concurrent multitasking, cues for the last action may not guide the next action due to a lack of sequence between subtasks. Moreover, there are multiple subtasks to choose when the operator returns to the primary task after an interruption. The effectiveness of cues on post-interruption performance still needs further verification. Research has shown that increasing cues can enhance the transparency of interface systems, that is, improve the observability and predictability of system behaviors, enabling users to understand what the system is doing, why it is doing it, and what it will do next27. Moreover, this does not increase the cost of mental workload28. Therefore, this study proposes an assistant cue suitable for concurrent multitasking interruption recovery, which is a cue that indicates the next action to be taken after an interruption, enabling operators to understand what the system should do next. And further explore the impact of retrieval cues on the recovery of concurrent multitasking interruptions, where a cue points towards the last action performed before the interruption, allowing operators to understand what the system was doing before the interruption.

Furthermore, mental fatigue state of the operator is another key factor affecting the performance of interruptions. Mental fatigue is a state of discomfort caused by long-term and demanding cognitive tasks that cannot maintain the best cognitive performance29. Mental fatigue has been preliminarily confirmed to affect post-interruption performance. Mental fatigue exacerbates the negative effects of interruption on working memory and related behavioral performance due to the detriment of cognitive functions30,31. Our study aims to explore further the impact of cues on post-interruption performance in various states of mental fatigue induced by prolonged cognitive tasks.

Based on the above background and research objectives, two experiments were designed in this study. In Experiment 1, we initially investigated whether retrieval cues and assistant cues positively impact rapid recovery and task performance following an interruption. In Experiment 2, we compared how two types of cues affect performance after interruptions in both fatigue and non-fatigue states. We aim to explore how different cues impact task recovery and performance post-interruptions and how fatigue affects these outcomes. Additionally, we used electroencephalogram (EEG) data to further explore specific cognitive activities from physiological and cognitive perspectives during task interruption.

According to the task interruption process in a concurrent multitasking environment, the resumption lag includes the process of memory retrieval, memory activation, and selection of subtasks for the primary task. Studies have shown that providing contextual cues can promote associative activation20 and decrease the occurrence of post-completion errors25. The retrieval cue points to the last action and provides system state information before interruptions. This cue helps operators quickly restore the memory of the primary task information through association activation. Therefore, the following assumption is proposed:

H1

The retrieval cues have a positive impact on performance following concurrent multitasking interruptions.

This study also proposed an assistant cue. There is an intelligent agent that evaluates the status of multiple subtasks when returning to the primary task after an interruption. The intelligent agent seeks out urgent tasks and offers guidance with important, timely, and meaningful cues. Assistant cues may reduce the time required for selecting subtasks after a task interruption, which cannot be achieved by retrieval cues. Based on this, the following assumptions are proposed:

H2.1

The assistant cues positively impact on performance after concurrent multitasking interruptions.

H2.2

In a multitasking environment, assistant cues have a greater impact on interruption resumption than retrieval cues.

The resumption lag after a task interruption relates to the inhibition of irrelevant information, task switching, and working memory retrieval, which are core aspects of executive control32. Executive control is compromised due to fatigue. Mental fatigue affects control processes involved in the organization of actions and plays a significant role in deliberate and goal-directed behavior33. Therefore, mental fatigue can exacerbate the negative effects of interruption on working memory and related behavioral performance due to the detriment of cognitive functions31. Informational cues may partially offset cognitive function impairment and decline in executive control. Previous studies have shown that as mental fatigue intensifies, the effectiveness of the task preparation in the transformation task decreases33 and relies more on the representation of the current cue32. Therefore, the following assumption is proposed:

H3

Mental fatigue moderates the impact of information cues on task interruption performance. The information cues exert a more significant positive effect on task interruption performance under a fatigue state.

Experiment 1

Methods

Participants

Human Factors and Ergonomics Laboratory, Beijing Jiaotong University, reviewed and approved the experiment. All participants were treated according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and all methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations. Fifteen participants volunteered for the experiment (8 males and 7 females), as estimated by the sample size calculation using GPower. Partial η2 was obtained from previous studies34 and f was calculated using the following:

|

Their ages ranged from 23 to 31 years (M = 24.96, SD = 3.14). All participants were right-handed and had no behavioral or cognitive impairments. Each participant volunteered, consented, and was fully informed about the experiment.

Materials and procedure

We used MATB-II (Fig. 3) as the experimental environment for the human–computer concurrent multitasking interaction35. The MATB-II has been used to study the human characteristics of physiological psychology and behavior36 in multitasking environments. It contains four subtasks: system monitoring (SYSMON), resource management (RESMAN), tracking (TRK), and communication (COMMUN):

Fig. 3.

The primary MATB-II task with all the retrieval cues (orange arrow) and assistant cues (red arrow).

SYSMON: Participants should click the mouse to respond when visual alerts activate (F5 illuminates red) or deactivate (F6 dims to background color). When the indicator light of each scale (F1-F4, represented by a segmented bar graph) touches either the upper or lower section of the scale, participants should respond by clicking on the scale with lights that have shifted up or down.

TRK. The target center point of the TRK continuously shifts toward the exterior of the box. In manual mode, users must continuously adjust the joystick to maintain a drifting central target within the bounding box. During automated operation, the target self-stabilizes within the inner box despite minor oscillations, requiring no manual intervention.

COMM. The task requires participants to modify communication frequencies during audio transmissions (e.g., air traffic control instructions); they must first select a radio channel. This activates frequency adjustment arrows and an ENTER confirmation button, enabling sequential arrow clicks to modify values before finalizing changes.

RESMAN. Participants are tasked with manipulating pumps to maintain A and B tank levels fluctuating within ± 500 units of their initial 2,500 unit conditions. Pumps may temporarily malfunction, indicated by a color change to red. During this period, participants cannot operate pump until it returns to the background color.

The primary tasks consisted of three subtasks (SYSMON, TRK, and RESMAN). Participants were instructed to monitor and control each subtask concurrently with the same weight, aiming to maximize their overall performance. In this experiment, to simulate the busy monitoring task, 22 SYSMON events are designed in a set of conditions. TRK adopts manual mode, and the amount of random target movement per update cycle is set at high. For RESMAN, the backup reservoirs have limited capacity, there were 1–2 pumps damaged during the process, which were recovered within 10 s. Detailed task design visit: https://osf.io/vfwcq/files/osfstorage. The interruption tasks were simple mathematical questions (Fig. 4), randomly generated and popped up unexpectedly, with a minimum interval of 30 s between consecutive interruptions. The window of interruption tasks covered the entire screen. Participants encountered six interruption tasks in an experimental condition, necessitating them to solve the math questions, submit answers, and then resume the primary tasks. This experiment adopted immediate interruption15. When an interruption occured, the participants had to complete all the math questions, and the interface of math questions covers the full screen. Participants were unable to continue with the primary tasks until the interruption was resolved.

Fig. 4.

Interface of math questions.

This study employed a within-subjects experimental design, and independent variable was cue types after the interruption, including no cue (NC), retrieval cue (RC), assistant cue (AC), and full assistant cue (full AC). Figure 3 shows the primary MATB-II task with all the retrieval cues (orange arrow) and assistant cues (red arrow). The two colors of the arrows in Fig. 3 are only used to distinguish the types of cues. Only one type of cue is presented as a red arrow in one condition during the experiment. In the retrieval cue conditions, only one red arrow points to the location of the last action performed before interruptions. In the assistant cue condition, the red arrow points to the location to be executed: for the SYSMON, when the warning boxes and scales (F1-F6) change, the corresponding location cues appear; for the TRK, when the target center moves outside of the box, the corresponding location cues appear; for the COMM, when there is a request, the cue appears (COMM subtasks are applicable only in subsequent formal experiments); for the RESMAN, when A and B fuel tanks fluctuate more than 100, the corresponding location cues appear and indicate adjustment trends (increase or decrease the fuel). The arrows disappeared after completing the related operations. All cues disappeared after 5 s after an interruption, even without operation. In the full assistant cue condition, no matter whether an interruption occurs, the cues appear as long as the above requirements are matched. There is no cue after the interruption in the no-cue condition. There were four conditions, each requiring six minutes to complete the primary task. A baseline condition without interruptions was also performed.

The participants were first trained on the MATB-II for 1 h. The sequence of conditions in the experiments was randomized. After completing tasks in each condition, participants filled out the NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) to assess their mental workload37 and Situational Awareness Rating Technique (SART) scales to assess situation awareness38.

Measures and data analysis

Primary task performance encompassed the following metrics: response time to events in the SYSMON task, the root mean square deviation from the center point in pixel units for the TRK task, and the deviation in tank volumes in the RESMAN task. The performance of subtasks was standardized and unified by z-scores. Subsequently, these z-scores were aggregated to derive an overall performance for the primary task39.

|

|

NASA-TLX was employed to quantify the subjective mental workload, while the SART was used to assess situation awareness. When sphericity assumptions were violated, the Greenhouse–Geisser method was applied to adjust the variance analysis data. Bonferroni correction post hoc analyses were conducted. Significance was established at a p-value < 0.05, and the effect size was quantified using partial eta-square ( ).

).

Results

Primary task performance

The descriptive data of subtasks and overall performance are shown in Table 1. A one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (rm-ANOVA) was conducted. The results indicated that cue types had significant effects on overall performance, F(4,56) = 16.58, p < 0.001,  = 0.54, RESMAN, F(4,56) = 13.21, p < 0.001,

= 0.54, RESMAN, F(4,56) = 13.21, p < 0.001,  = 0.49, and SYSMON, F(4,56) = 13.24, p < 0.001,

= 0.49, and SYSMON, F(4,56) = 13.24, p < 0.001,  = 0.49. But there was no significant difference between TRK with different types of cues, F(4,56) = 0.77, p = 0.547,

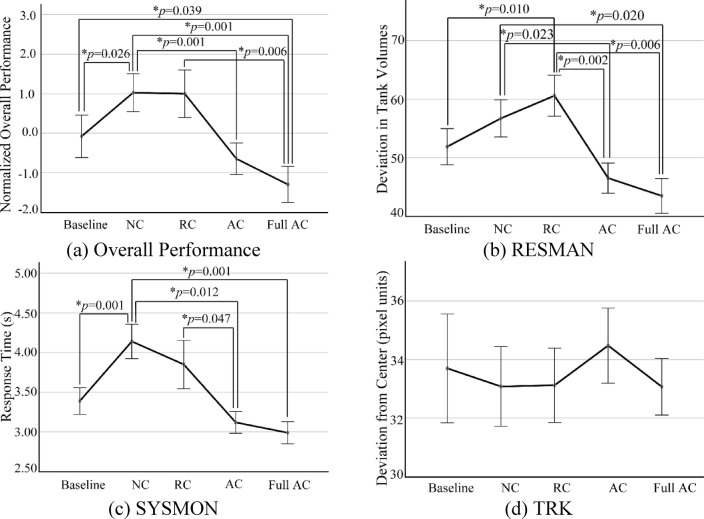

= 0.49. But there was no significant difference between TRK with different types of cues, F(4,56) = 0.77, p = 0.547,  = 0.05. As shown in Fig. 5, both post-interruption assistant cues and full assistance cues led to a significant improvement in primary task performance. Post-hoc analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the retrieval cue and the no cue conditions, and no significant difference was found between the post-interruption assistant cue and the full assistance cue.

= 0.05. As shown in Fig. 5, both post-interruption assistant cues and full assistance cues led to a significant improvement in primary task performance. Post-hoc analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the retrieval cue and the no cue conditions, and no significant difference was found between the post-interruption assistant cue and the full assistance cue.

Table 1.

Description Statistics for subtasks and overall performance.

| Cue type | Overall | RESMAN | SYSMON | TRK |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (No interruption) | − 0.08 ± 2.01 | 51.88 ± 11.55 | 3.39 ± 0.63 | 33.70 ± 6.96 |

| NC | 1.03 ± 1.79 | 56.71 ± 11.78 | 4.14 ± 0.81 | 33.08 ± 5.09 |

| RC | 1.00 ± 2.24 | 60.59 ± 13.06 | 3.85 ± 1.14 | 33.12 ± 4.76 |

| AC | − 0.65 ± 1.49 | 46.52 ± 9.68 | 3.12 ± 0.51 | 34.48 ± 4.80 |

| Full AC | − 1.30 ± 1.71 | 43.48 ± 11.13 | 2.99 ± 0.52 | 33.07 ± 3.62 |

Fig. 5.

Behavioral data for three subtasks and overall performance. Error bars indicate SEM. The high performance is related to lower values.

Subjective workload

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the subjective workload and situation awareness. The subjective workload evaluation was obtained from the NASA-TLX after completing each condition. A one-way rm-ANOVA was conducted (Fig. 6), revealing the significant main effects on subjective workload for cue types, F(4,56) = 14.96, p < 0.001, = 0.52. The workload was the highest without any cue, followed by retrieval cue and assistant cue. The assistant cue significantly reduced the subjective workload, and there was no significant difference with the baseline. The main effect of situational awareness obtained from the SART was significant, F(4,56) = 11.03, p < 0.001,

= 0.52. The workload was the highest without any cue, followed by retrieval cue and assistant cue. The assistant cue significantly reduced the subjective workload, and there was no significant difference with the baseline. The main effect of situational awareness obtained from the SART was significant, F(4,56) = 11.03, p < 0.001,  = 0.44. The assistant cue significantly improved the situation awareness of the participants.

= 0.44. The assistant cue significantly improved the situation awareness of the participants.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for subjective workload and situation awareness.

| Tasks | Subjective workload | Situation awareness |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (No interruption) | 42.27 ± 13.82 | 20.93 ± 6.51 |

| No cue | 70.53 ± 14.71 | 10.80 ± 5.36 |

| Retrieval cue | 66.80 ± 14.73 | 19.13 ± 5.34 |

| Assistant cue | 50.80 ± 9.20 | 12.13 ± 5.39 |

| Full assistant cue | 48.07 ± 11.14 | 19.53 ± 5.90 |

Fig. 6.

Subjective workload and situation awareness. Error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

The effect of the assistant cues on improving the performance of the interrupted primary task was verified by experiment 1, especially for the RESMAN and SYSMON subtasks. It was initially confirmed that information cues positively affect post-interruption performance in the concurrent multitasking environment and that the assistant cues were better than the retrieval cues for post-interruption recovery. However, the retrieval cues did not significantly improve interrupted task performance compared to the no cue condition. The results of this experiment on retrieval cues differ from those obtained in previous interruption management studies26 due to differences in the type of primary task used. Previous studies have used sequential multitasking even in more complex multitasking contexts24. The role of retrieval cues in sequential multitasking is similar to a visual placeholder40, a symbol that occupies a fixed location and later adds content to it, which could simplify and speed up the process of switching attention between displays. The retrieval cues in experiment 1 assigned to this placeholder the meaning of the last executed subtask before being interrupted, thus facilitating fast switching of attention after an interruption40. However, there is no sequential order among subtasks in the concurrent multitasking environment. The retrieval cues representing the last action before an interruption did not indicate the following action after the interruption. Therefore, a retrieval cue did not play a significant positive role in performance improvement for concurrent multitasking interruptions.

In addition, it was found that there was no significant difference in the primary task performance between the condition with the assistant cues and the condition with the full assistant cues. It suggested that the short post-interruption cues were sufficient to improve the overall performance without using the full assistant cues. This is because performance decreases due to interruptions are concentrated in the period after the interruption (mainly in resumption lag)12. The assistant cues were targeted to eliminate the negative effects of interruptions, and there was no need to provide assistant cues throughout the whole task. Otherwise, it may confuse the goal of the cues’ work. The full assistance cues would no longer be studied in formal experiments. Further, in formal experiments, EEG data were collected to deeply analyze the positive effects of interruption cues on post-interruption performance and the mechanisms. The differences in the effects of interruption cues under different fatigue states were also analyzed.

Experiment 2

Method

Participants

Human Factors and Ergonomics Laboratory, Beijing Jiaotong University, reviewed and approved the experiment. All participants were treated according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and all methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

We recruited 25 participants (13 males and 12 females) who were different from those involved in experiment 1. Their ages ranged from 22 to 30 years (M = 24.08, SD = 2.14). All participants were right-handed and had no behavioral or cognitive impairments. Each participant volunteered, consented, and was fully informed about the experiment.

Materials and procedure

In Experiment 2, we introduced fatigue factors and compared the effects of retrieval cues and assistant cues on post-interruption performance in both fatigue and non-fatigue states. The formal experiment used the same MATB-II and math tasks as Experiment 1. This study employed a within-subjects 2 × 3 experimental design. The fatigue state was defined by two levels (fatigue and non-fatigue); cue type was organized into three levels (no cue, assistant cue, and retrieval cue). There were six conditions, each requiring six minutes to complete the primary task. All participants completed tasks in each condition.

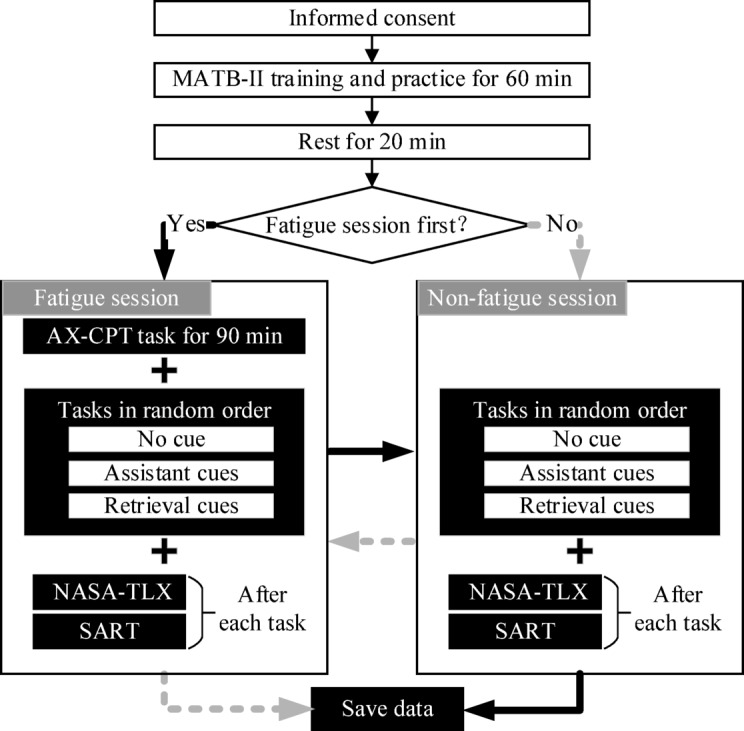

Participants were pre-trained on MATB-II for 60 min to stabilize performance before the formal experiment. The experiment comprised six conditions, split by fatigue level into “fatigue” and “non-fatigue” sessions across two days (Fig. 7). The session order was randomized. On day 1, four conditions of one session were completed; the other session followed on day 2. Participants were advised to rest adequately at night. Each task was assessed using NASA-TLX and SART.

Fig. 7.

Experiment Design. The six conditions of the experiment were divided by the fatigue level into the “fatigue session” and “non-fatigue session”, which were carried out in two days.

Figure 7 illustrates the experimental design. We induced fatigue before the fatigue session using the continuous performance test (AX-CPT), which is a paradigm for rapidly inducing fatigue (Fig. 8). Participants were required to work on the AX-CPT for 90 minutes41. The paradigm consists of a cue A, a probe X, and two random letters aiming to judge the cue-probe sequence. The letters “K” and “Y” were omitted due to visual similarity to “X” to ensure task accuracy. Participants’ accuracy was monitored every 30 min. The fatigue induction was effective if the participants’ accuracy was no less than 85%. A VAS-F42, a visual analogue scale designed to quantify fatigue severity, was employed to gauge participants’ condition before and after the AX-CPT, thereby evaluating the success of fatigue induction.

Fig. 8.

Experimental paradigm of AX-CPT.

Measures and data analysis

Primary task performance encompassed various metrics: response latency in the SYSMON, deviation from the central point (measured in pixels) in the TRK, reaction time to demands in the COMM, and deviations in tank volumes in the RESMAN. All performance indicators were standardized using z-scores aggregated to compute an overall primary task performance score. Subjective workload, situational awareness measurement, and data analysis techniques remained consistent with those employed in Experiment 1.

|

|

EEG recording and analysis

The experiment was conducted in a room with standard illumination and electrical shielding measures. Using Ag/AgCl electrodes, EEG signals were continuously captured from 64 scalp positions arranged according to the international 10–20 system. Vertical electrooculogram (VEOG) and horizontal electrooculogram (HEOG) data were recorded as shown in Fig. 9. The impedance of the electrodes was kept below 10 kΩ. The SynAmps2 amplifier from Neuroscan Inc. (USA) was utilized to amplify EEG signals, which were then digitized with a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz. Offline data analysis employed the EEGLAB toolbox in MATLAB, applying a 0.1–30 Hz bandpass filter43 and ICA for the removal of eye movement artifacts. Filtered data were intercepted into epochs of 500 ms before, during, and after the interruption, respectively (Fig. 10).

Fig. 9.

Ocular electrode locations.

Fig. 10.

The interception of EEG Epoch.

Theta and Alpha oscillations are associated with working memory processes44. Theta rhythms are recognized as neural mechanisms underlying working memory maintenance, particularly showing increased amplitudes during memory encoding and retention under higher cognitive loads45. Concurrently, Alpha oscillations demonstrate functional links to attentional control mechanisms, exhibiting cortical inhibition patterns that suppress task-irrelevant cortical activations to maintain focused attention46. These justify the selection of both frequency bands for analytical investigation in the study. Theta (4–8 Hz) and Alpha (8–12 Hz) bands were analyzed at Fz, Cz, Pz, using a − 500 to − 200 ms baseline47. The event-related spectral perturbation values were extracted48, and a 2 × 3 × 3 rm-ANOVA examined the main and interaction effects on EEG power, considering fatigue state, cue type, and epoch.

Results

Manipulation check: fatigue induced

The VAS-F data was saved to verify the effectiveness of fatigue induction through a 90-min AX-CPT task. A paired t-test was used to analyze the fatigue and energy subscales data before and after the task. The results indicated that the fatigue subscale rating after the AX-CPT task was significantly higher than before, t(24) = − 11.30, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.26, and the energy subscale rating after the AX-CPT task was significantly lower than before, t(24) = 8.638, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.73. This suggested that fatigue was successfully induced.

Primary task performance

The descriptive data of subtasks and overall performance are shown in Table 3. A 2 × 2 rm-ANOVA was performed on the fatigue state and cue type. The main effects of fatigue, F(1, 24) = 12.03, p = 0.002,  = 0.33, and cue type, F(2, 48) = 6.49, p = 0.003,

= 0.33, and cue type, F(2, 48) = 6.49, p = 0.003,  = 0.21, on overall performance were both significant. Mental fatigue led to lower primary task performance, and participants performed better with assistant cues than with retrieval cues or without cues. The results of simple effects indicated that the cue type effect was significant only in the fatigue state, F(2, 48) = 5.10, p = 0.010,

= 0.21, on overall performance were both significant. Mental fatigue led to lower primary task performance, and participants performed better with assistant cues than with retrieval cues or without cues. The results of simple effects indicated that the cue type effect was significant only in the fatigue state, F(2, 48) = 5.10, p = 0.010,  = 0.18, there were marginal significance on overall performance between cue types when participants were not fatigued, F(2, 48) = 3.04, p = 0.057,

= 0.18, there were marginal significance on overall performance between cue types when participants were not fatigued, F(2, 48) = 3.04, p = 0.057,  = 0.11, are shown in Fig. 11. Post hoc analysis showed that the performance of assistant cues was significantly better than that of retrieval cues (p = 0.007). The performance of each subtask was analyzed separately, and the results are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 12. We found the main effects of fatigue and cue type on SYSMON performance were significant. However, no significant main effects were found in the other three subtasks (RESMAN, TRK, and COMM).

= 0.11, are shown in Fig. 11. Post hoc analysis showed that the performance of assistant cues was significantly better than that of retrieval cues (p = 0.007). The performance of each subtask was analyzed separately, and the results are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 12. We found the main effects of fatigue and cue type on SYSMON performance were significant. However, no significant main effects were found in the other three subtasks (RESMAN, TRK, and COMM).

Table 3.

Description Statistics for the subtasks and overall performance.

| Fatigue state | Cue type | Overall | RESMAN | TRK | SYSMON | COMM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-fatigue | NC | − 0.02 ± 0.66 | 76.21 ± 32.82 | 38.35 ± 6.85 | 6.89 ± 2.55 | 4.07 ± 1.40 |

| AC | − 0.13 ± 0.53 | 76.48 ± 30.51 | 38.55 ± 6.25 | 6.28 ± 1.79 | 4.37 ± 1.73 | |

| RC | 0.10 ± 0.65 | 80.50 ± 30.05 | 38.50 ± 5.75 | 6.86 ± 2.00 | 4.39 ± 1.47 | |

| Fatigue | NC | 0.24 ± 0.59 | 84.89 ± 38.26 | 40.21 ± 6.93 | 7.79 ± 2.74 | 4.99 ± 2.32 |

| AC | 0.16 ± 0.68 | 84.51 ± 36.16 | 39.74 ± 6.63 | 7.31 ± 2.17 | 4.11 ± 1.62 | |

| RC | 0.44 ± 0.77 | 88.10 ± 35.86 | 41.27 ± 7.71 | 8.26 ± 2.55 | 5.24 ± 2.09 |

Fig. 11.

Simple effects of fatigue × cue type on overall primary task performance. Error bars are SEMs.

Table 4.

Two-way rm-ANOVA analyses results for each subtask performance.

| ANOVAs | RESMAN | TRK | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | F | p |

|

F | p |

|

| Fatigue | 3.66 | 0.068 | 0.13 | 3.26 | 0.085 | 0.13 |

| Cue types | 0.74 | 0.484 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.475 | 0.03 |

| Fatigue × Cue types | 1.11 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.43 | 0.652 | 0.02 |

| ANOVAs | SYSMON | COMM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | F | p |

|

F | p |

|

| Fatigue | 10.51 | 0.003* | 0.31 | 2.80 | 0.107 | 0.10 |

| Cue types | 8.34 | 0.001* | 0.26 | 1.54 | 0.224 | 0.06 |

| Fatigue × Cue types | 0.10 | 0.907 | 0.004 | 2.40 | 0.103 | 0.09 |

*Indicates statistical significance, where p < 0.05.

Fig. 12.

Simple effects of fatigue × cue type on subtasks’ performance. Error bars are SEMs.

Subjective workload and situation awareness

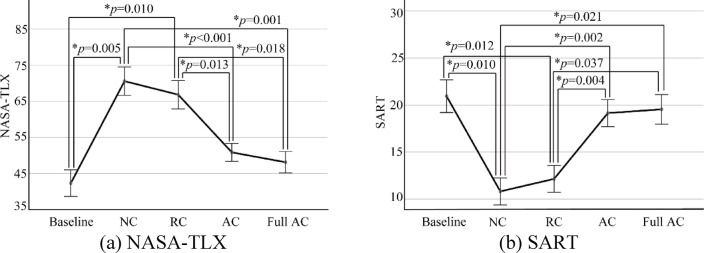

The subjective workload was obtained from NASA-TLX after completing each condition. Two-way rm-ANOVA results revealed the significant main effects of fatigue, F(1, 24) = 43.60, p < 0.001,  = 0.65, and cue type, F(2, 48) = 10.20, p < 0.001,

= 0.65, and cue type, F(2, 48) = 10.20, p < 0.001,  = 0.30, on subjective workload, and their significant interaction effect, F(2, 48) = 20.97, p < 0.001,

= 0.30, on subjective workload, and their significant interaction effect, F(2, 48) = 20.97, p < 0.001,  = 0.47. Subsequent analyses showed that workload with assistant cues was significantly lower than no cue and retrieval cues in fatigue state, F(2, 48) = 22.47, p < 0.001,

= 0.47. Subsequent analyses showed that workload with assistant cues was significantly lower than no cue and retrieval cues in fatigue state, F(2, 48) = 22.47, p < 0.001,  = 0.51, as shown in Fig. 13A. However, in the non-fatigue state, there was no significant difference in workload among the three cue types, F(2, 48) = 0.47, p = 0.631,

= 0.51, as shown in Fig. 13A. However, in the non-fatigue state, there was no significant difference in workload among the three cue types, F(2, 48) = 0.47, p = 0.631,  = 0.02. Post hoc analysis showed that the workload with assistant cues was significantly lower than no cue (p = 0.004), and retrieval cue (p = 0.002). There was no significant difference between no cue and retrieval cue was found (p = 0.602).

= 0.02. Post hoc analysis showed that the workload with assistant cues was significantly lower than no cue (p = 0.004), and retrieval cue (p = 0.002). There was no significant difference between no cue and retrieval cue was found (p = 0.602).

Fig. 13.

Simple effects of fatigue × cue type on subjective workload (A) and situation awareness (B). Error bars are SEMs.

The situation awareness was obtained from SART after completing each condition. Two-way rm-ANOVA results also revealed the significant main effects of fatigue, F(1, 24) = 17.13, p < 0.001,  = 0.42, and cue type, F(2, 48) = 7.51, p = 0.003,

= 0.42, and cue type, F(2, 48) = 7.51, p = 0.003,  = 0.24, on situation awareness, as shown in Fig. 13B. Subsequent analyses showed that the effects of cue type were significant both in non-fatigue F(2, 48) = 3.98, p = 0.025,

= 0.24, on situation awareness, as shown in Fig. 13B. Subsequent analyses showed that the effects of cue type were significant both in non-fatigue F(2, 48) = 3.98, p = 0.025,  = 0.14, and fatigue state, F(2, 48) = 7.33, p = 0.004,

= 0.14, and fatigue state, F(2, 48) = 7.33, p = 0.004,  = 0.23. Post hoc analysis showed that the situation awareness with assistant cues was higher than no cue (p = 0.010) and retrieval cue (p = 0.054). No significant difference was found between no cue and retrieval cue was found (p = 0.335). The interaction effect of the two factors was not significant, F(2, 48) = 1.93, p = 0.156,

= 0.23. Post hoc analysis showed that the situation awareness with assistant cues was higher than no cue (p = 0.010) and retrieval cue (p = 0.054). No significant difference was found between no cue and retrieval cue was found (p = 0.335). The interaction effect of the two factors was not significant, F(2, 48) = 1.93, p = 0.156,  = 0.07.

= 0.07.

EEG

The 2 (fatigue state: non-fatigue and fatigue) × 3 (cue type: no cue, assistant cue, and retrieval cue) × 3 (epoch: pre-interruption, interruption, and post-interruption) three-way rm-ANOVA was performed, see Table 5. The results showed the main effect of epoch on theta power was significant, F(2, 44) = 13.51, p < 0.001,  = 0.38. Post hoc analyses indicated that theta power of post-interruption was higher than pre-interruption (p = 0.003) and interruption (p < 0.001). A three-way interaction effect of fatigue, cue type, and epoch was found, F(4,88) = 4.86, p = 0.001,

= 0.38. Post hoc analyses indicated that theta power of post-interruption was higher than pre-interruption (p = 0.003) and interruption (p < 0.001). A three-way interaction effect of fatigue, cue type, and epoch was found, F(4,88) = 4.86, p = 0.001, = 0.18. Further analyses showed the significant fatigue × cue type effect on theta power was found only in the epoch of post-interruption, F(2,44) = 5.77, p = 0.006,

= 0.18. Further analyses showed the significant fatigue × cue type effect on theta power was found only in the epoch of post-interruption, F(2,44) = 5.77, p = 0.006,  = 0.21, not in the epoch of pre-interruption, F(2,44) = 3.19, p = 0.051,

= 0.21, not in the epoch of pre-interruption, F(2,44) = 3.19, p = 0.051,  = 0.12, and interruption, F(2,44) = 0.23, p = 0.723,

= 0.12, and interruption, F(2,44) = 0.23, p = 0.723,  = 0.01. The following simple effects indicated that theta power in post-interruption were significantly different between the three cue types in fatigue state, F(2,44) = 4.28, p = 0.020,

= 0.01. The following simple effects indicated that theta power in post-interruption were significantly different between the three cue types in fatigue state, F(2,44) = 4.28, p = 0.020,  = 0.16, and not significantly different in the non-fatigue state, F(2,44) = 1.22, p = 0.305,

= 0.16, and not significantly different in the non-fatigue state, F(2,44) = 1.22, p = 0.305,  = 0.05. Figure 14 presents the scalp topographies of the theta power.

= 0.05. Figure 14 presents the scalp topographies of the theta power.

Table 5.

Three-way rm-ANOVA analyses results for Theta and Alpha power.

| Effect | Theta | Alpha | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p |

|

F | p |

|

|

| Fatigue | 2.19 | 0.153 | 0.09 | 0.81 | 0.377 | 0.04 |

| Cue type | 0.22 | 0.804 | 0.01 | 0.80 | 0.455 | 0.04 |

| Epoch | 13.51 | < 0.001* | 0.38 | 5.71 | 0.006* | 0.21 |

| Fatigue × Cue type | 0.71 | 0.466 | 0.03 | 0.69 | 0.506 | 0.03 |

| Fatigue × Epoch | 1.11 | 0.340 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.641 | 0.02 |

| Cue type × Epoch | 1.35 | 0.271 | 0.06 | 1.13 | 0.340 | 0.05 |

| Three factors interaction | 4.86 | 0.001* | 0.18 | 2.93 | 0.025* | 0.12 |

Fig. 14.

Topographic representation of the grand average of theta power.

For alpha, the three-way rm-ANOVA results also found a significant main effect of epoch, F(2, 44) = 5.71, p = 0.006,  = 0.04, and a three-factor interaction, F(4, 88) = 2.93, p = 0.025,

= 0.04, and a three-factor interaction, F(4, 88) = 2.93, p = 0.025,  = 0.12. We found a significant interaction effect between fatigue and epoch in assistant cue condition, F(2, 44) = 3.55, p = 0.037,

= 0.12. We found a significant interaction effect between fatigue and epoch in assistant cue condition, F(2, 44) = 3.55, p = 0.037,  = 0.14, but not in no cue, F(2, 44) = 0.55, p = 0.578,

= 0.14, but not in no cue, F(2, 44) = 0.55, p = 0.578,  = 0.02, and retrieval cue conditions, F(2, 44) = 2.54, p = 0.090,

= 0.02, and retrieval cue conditions, F(2, 44) = 2.54, p = 0.090,  = 0.10. Further analyses showed the significant fatigue × cue type effect on alpha power was found only in the epoch of post-interruption, F(2,44) = 3.27, p = 0.047,

= 0.10. Further analyses showed the significant fatigue × cue type effect on alpha power was found only in the epoch of post-interruption, F(2,44) = 3.27, p = 0.047,  = 0.13, not in the epoch of pre-interruption, F(2,44) = 2.82, p = 0.070,

= 0.13, not in the epoch of pre-interruption, F(2,44) = 2.82, p = 0.070,  = 0.11, and interruption, F(2,44) = 0.06, p = 0.946,

= 0.11, and interruption, F(2,44) = 0.06, p = 0.946,  = 0.003. Figure 15 presents the scalp topographies of alpha power.

= 0.003. Figure 15 presents the scalp topographies of alpha power.

Fig. 15.

Topographic representation of the grand average of alpha power.

Discussion

This experiment aimed to examine the effectiveness of providing cues for improving interrupted primary task performance and analyze the effects of different cue types. The study compared the effects of assistant cue, retrieval cue, and no-cue conditions on concurrent multitask interruption performance under both fatigue and non-fatigue states, and analyzed the physiological and cognitive levels in conjunction with EEG data. The experimental results did not support H1, indicating that providing retrieval cues had no positive effect on performance after interruptions in the concurrent multitasking, and instead reduced performance (Fig. 11). H2.1 and H2.2 were verified. Assistant cues significantly positively affected the overall performance of the primary task after interruptions, especially for the SYSMON subtask. In a concurrent multitasking environment, assistant cues outperform retrieval cues for recovery of primary tasks and improvement of post-interruption performance. The H3 has been partially validated. In the state of fatigue, information cues have a greater impact on improving task interruption performance.

Experiments confirmed the effectiveness of assistant cues for concurrent multitask interruption management. Some researchers have argued that environmental cues work because utilizing good well-established associations between environmental features and events in memory that form cues when the operator notices facilitates the activation of relevant goals49. Applying cue-based associations during task execution allows for rapid and accurate assessment of system state with minimal demand on working memory34. Most previous studies exploring interruption cues have not been based on complex concurrent multitasking environments, thus it is difficult to compare the results with those of this experiment. Sasangohar et al.50 explored the effect of interruption recovery assistance in time-critical control tasks, which has a similar research context to the present experiment. Sasangohar found that the interaction of the aid function minimized visual search time by directing participants’ attention to events with the highest priority, thereby improving performance, especially in complex decision-making under high time pressure. This is similar to the results of the present experiment.

Cueing effect

The memory for goals (MFG) theory of interruption12 characterizes each subtask by a particular goal. MFG draws lessons from many basic theories of ACT-R. An important feature of the usability of ACT-R is its goal stack. The difference is that MFG “turns off” the architectural goal stack of ACT-R, and works strictly with its working memory mechanism12. There is no last-in-first-out order of completion; instead, the most active goal at a given time will guide action20. After an interruption, participants need to quickly activate primary task-related goal memory and extract accurate information from the memory to respond. Assistant cues could help participants quickly locate the position at which they need to perform by quickly activating the goal activity level and operating with meaningful action instructions, significantly reducing the resumption lag, while also reducing the cognitive load on working memory resources21. Further, in combination with the participants’ skills, knowledge, and experience, the cognitive focus of the primary task was recovered through the assistant cues. And participants perceived higher situational awareness, leading to a faster resumption of primary tasks. The results of the subjective situational awareness scale corroborated this finding (Fig. 13). Anderson and Douglass51 examined the costs associated with the storage and retrieval of subgoals and found that subjects acted more slowly in retrieving the goals and that the longer they took to develop these goals, the slower the action. In the declarative storage system of ACT-R, the likelihood of retrieving a given item depends on its level of activation. This activation is determined by base-level activation and associative activation. Associative activation is a limited type of attentional activation that spreads among those items that are relevant to the current context52. Quick orientation via assistant cues could help focus back on the primary task as opposed to choosing between four subtasks. Additionally, analysis across four subtasks revealed that the cueing effect was most pronounced in SYSMON and COMM tasks, likely attributable to their categorization as discrete tasks requiring greater reliance on working memory following interruptions. In contrast, RESMAN and TRK, being continuous tasks, demonstrated participants’ maintained sustained attention patterns, rendering them less affected by interruption-induced working memory decline.

Moderation effect of mental fatigue

The simple effects analysis of the interaction between fatigue and cues found that the assistant cues exerted a significant positive effect on performance when the participants were in a state of mental fatigue, and the assistant cues only exhibited marginal significance (p = 0.057) when participants were non-fatigued. This may be due to the reflexive attention caused by the assistant cues. According to the voluntariness of attention, attention can be divided into voluntary attention and reflexive attention (involuntary attention)53. Reflexive attention is bottom-up stimulus-driven attention that triggers an outwardly directed response toward a stimulus. Attention’s alerting, orienting function is directed towards the current stimulus and is closer to the bottom-up information processing54, which is reactive control. According to the dual mechanisms of cognitive control (DMCC)55, proactive control is the prevention of potential conflicts by actively maintaining representations of target-related information before a response; Reactive control is the resolution of conflicts by reactivating target-related information during a reaction. Therefore, the cues given after interruption align with reactive control56. Mental fatigue exacerbates the depletion of cognitive resources. It has been shown that proactive cognitive control is more dependent on cognitive resources compared to reactive cognitive control, and thus mental fatigue weakens proactive control and facilitates reactive control57,58. The use of a salient red arrow in this experiment was able to cause reflexive attention upon return to the primary task interface after interruptions, which is the reactive control. Assistant cues had a clear pointing meaning and were facilitated in the fatigue state and thus could have a positive effect on post-interruption performance.

In Experiment 2, the assistant cues only had marginal significance on performance in non-fatigue state, which is not entirely consistent with the significant cueing effect obtained in Experiment 1. The discrepancies in statistical results between the two experiments can be attributed to two primary factors. First, fatigue modulated cueing effects by redistributing cognitive resources. Participants in fatigue state may have relied more on external cues to compensate for depleted cognitive capacity, amplifying the cueing effect, whereas non-fatigued participants showed weakened effects due to strategic variability or ceiling effects from sufficient cognitive flexibility. Second, procedural interference emerged in Experiment 2, where fatigue induction extended experimental duration and increased task load. Participants completing the non-fatigue condition first exhibited distraction from anticipating subsequent fatigue tasks, destabilizing cueing effects. Specifically, participants’ awareness of impending fatigue-inducing tasks likely triggered strategic adjustments, such as conserving cognitive resources or diverting attention to prepare for subsequent demands. While those starting with the fatigue condition developed psychological expectations for tasks during the subsequent non-fatigue session, further diminishing the effect. This is needed to avoid as much as possible by taking measures in future research. Additionally, a potential secondary factor involves the methodological variation in MATB-II task composition between experiments. In Experiment 1, only RESMAN, SYSMON, and TRK subtasks were utilized, whereas Experiment 2 incorporated all four subtasks, including the COMM. The COMM in Experiment 2 likely increased overall cognitive demands and attentional requirements. The COMM imposes distinct auditory-verbal processing loads and necessitates rapid response selection, potentially altering the baseline resource allocation strategy compared to the visual and manual used in Experiment 1, thus affecting the cue effect.

The role of cues in alertness and workload

The retrieval cues with the salient red arrow also produced reflexive attention. However, the retrieval cues had no clear instructions for the participant’s next action in a concurrent multitasking environment. Thus, instead of improving performance, the retrieval cues had a negative effect on post-interruption performance by creating reflexive attention, causing attention shifts, and taking up some cognitive resources. One unanticipated finding was that retrieval cues did not have a positive effect on performance, but they reduced the subjective workload and increased situational awareness to a certain extent, especially in the fatigue state. This was also corroborated by the EEG bands. Theta activity is correlated with workload, and the increase in working memory load-dependent theta wave activity is thought to become stronger as the amount of encoded information increases59. Alpha activity shows a moderate to large increase with reduced alertness during mental fatigue60. The theta and alpha power were significantly lower after interruptions under a fatigue state compared to the other conditions. This suggested that retrieval cues had a positive effect on workload and situational awareness. Furthermore, similar to assistant cues, retrieval cues had a greater improvement effect on interruption management under a fatigue state compared to non-fatigue. Theta and alpha activities were significantly lower after task interruptions with the retrieval-cue condition compared to the no-cue and assistant-cue conditions only in fatigue. This further proves the positive effect of retrieval cues in increasing alertness and reducing workload.

Subjective questionnaires and EEG data indicated that assistant cues also had a role in reducing subjective workload and increasing alertness compared to no cue. Participants could use available cues to reduce cognitive effort61. Similarly, the effect of assistant cues is more significant under fatigue conditions. Here is another noteworthy point to consider. Although assistant cues have a significantly greater positive impact on behavioral performance than retrieval cues, EEG results indicate that it is not as effective as retrieval cues in reducing workload and enhancing alertness. This may be due to the number of cue arrows. After each interruption, the retrieval cue only shows one arrow; the assistant cue may display multiple red arrows simultaneously based on the current development status of the primary task. When multiple arrows appear simultaneously, although they all have a task-assisting effect, they may inadvertently increase the workload of the participants in a short time. This also provides us with a way to optimize assistant cues for interruption management in the future.

Limitations and future research

The current study has a few limitations. First, the sample size used in the study is relatively small. Next, Experiment 1 suggested that only the short post-interruption cues were sufficient to improve the overall performance without using the full assistant cues. The specific display time of cues and the reliance of operators on cues are still questions worth studying. A preliminary analysis was conducted on the EEG characteristics of participants during the interruption process of multitasking concurrent tasks, but EEG data collection and feature analysis were limited in the study. In future work, finding more suitable physiological parameters and characteristics for analyzing interruption processes will be more beneficial for interruption management.

Conclusions and practical implications

This study introduces two strategies for managing task interruptions in concurrent multitasking environments: assistant cues and retrieval cues. Employing Experiment 1 and 2, alongside behavioral performance assessments and EEG data, the study validates the efficacy of cues in preserving multitasking interruption performance, personnel workload, and situational awareness. The assistant cues help quickly reactivate the target of the primary task after an interruption by establishing a strong connection with the primary task information in working memory. This improves performance and situational awareness after task interruption and reduces the subjective workload. Since retrieval cues cannot provide meaningful information for the next operation after the interruption of concurrent multitasking, and it is easy to seize attention resources, it has a slight negative effect on the performance after the interruption, but it can improve the alertness of operators and reduce the workload. In addition, information cues can better affect interruption management in concurrent multitasking environments when operators are in a mental fatigue state.

The allocation of functions between humans and machines, coupled with the escalating levels of automation and task complexity, has resulted in a proliferation of interruptions, while prolonged monitoring activities frequently induce fatigue among operators. Operators usually view interruptions as part of their work. For example, operators in the control rooms of nuclear power plants and nuclear fuel reprocessing plants must handle some alarms while performing daily monitoring operations. Handling alarms is a task interruption for operators. Even in simple tasks, performance will decline if the operator is interrupted when fatigued30. In the control rooms of nuclear power plants and spent fuel reprocessing plants, operators follow standardized operating procedures (SOPs) for emergency response tasks, which consist of detailed step-by-step instructions. Designing assistive cues based on these SOPs is feasible. Operators cannot memorize every detail of every procedure, and whether they consult digital or paper-based manuals, locating the relevant steps requires significant time. Therefore, the assistant information cues proposed in this study can be utilized for interruption management, they can not only reduce operators’ response time but also minimize human errors. In addition, eye tracking or portable physiological monitoring systems can be used to monitor operator fatigue and provide the most appropriate interruption management strategies under different fatigue states.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.; Data curation, Y.C. and W.F.; Formal analysis, Y.C. and C.Z; Funding acquisition, W.F. and J.M.; Investigation, C.Z.; Methodology, Y.C. and W.F.; Project administration, J.M. and C.Z.; Software, Y.C. and C.Z.; Supervision, J.M. and C.Z.; Validation, J.M. and W.F.; Visualization, Y.C.; Roles/Writing—original draft, Y.C. and C.Z; Writing—review and editing, W.F. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 72271015) and The Company’s Independent Research Project (KY23125).

Data availability

The data for all experiments are available at https://osf.io/vfwcq/files/osfstorage.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Darmoul, S., Ahmad, A., Ghaleb, M. & Alkahtani, M. Interruption management in human multitasking environments. IFAC-PapersOnLine48, 1179–1185. 10.1016/j.ifacol.2015.06.244 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.EyalOphir, C. N. & Wagner, A. D. Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.106, 15583–15587. 10.1073/pnas.0903620106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liebowitz, J. Interruption management: A review and implications for IT professionals. IT Prof.13, 44–48. 10.1109/MITP.2010.118 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkahtani, M. et al. Human interruption management in workplace environments: An overview. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res.10, 5452–5458. 10.48084/etasr.3404 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson, M. D., Farrell, S., Visser, T. A. & Loft, S. Remembering to execute deferred tasks in simulated air traffic control: The impact of interruptions. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl.24, 360–379. 10.1037/xap0000171 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheridan, T. B. & Parasuraman, R. in Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. (eds Thomas B Sheridan & Raja Parasuraman) 1–4 (Sage Publications Sage).

- 7.Mizuno, K. et al. Mental fatigue caused by prolonged cognitive load associated with sympathetic hyperactivity. Behav. Brain Funct.7, 1–7 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noé, F., Hachard, B., Ceyte, H., Bru, N. & Paillard, T. Relationship between the level of mental fatigue induced by a prolonged cognitive task and the degree of balance disturbance. Exp. Brain Res.239, 2273–2283 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salvucci, D. D., Taatgen, N. A. & Borst, J. P. in SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. (eds Salvucci, D. D, Taatgen, N. A & Borst, J. P.) 1819–1828.

- 10.Chen, Y.-Y., Fang, W.-N., Bao, H.-F. & Guo, B.-Y. The effect of task interruption on working memory performance. Hum. Fact.66, 1132–1151 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ülkü, S., Getzmann, S., Wascher, E. & Schneider, D. Be prepared for interruptions: EEG correlates of anticipation when dealing with task interruptions and the role of aging. Sci. Rep.14, 5679. 10.1038/s41598-024-56400-y (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altmann, E. M. & Trafton, J. G. Memory for goals: an activation-based model. Cogn. Sci.26, 39–83. 10.1016/s0364-0213(01)00058-1 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxby, D. J., Matthews, G., Warm, J. S., Hitchcock, E. M. & Neubauer, C. Active and passive fatigue in simulated driving: Discriminating styles of workload regulation and their safety impacts. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl.19, 287–321. 10.1037/a0034386 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grundgeiger, T., Sanderson, P., MacDougall, H. G. & Venkatesh, B. Interruption management in the intensive care unit: Predicting resumption times and assessing distributed support. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl.16, 317–334 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFarlane, D. C. Comparison of four primary methods for coordinating the interruption of people in human-computer interaction. Human–Comput. Interact.17, 63–139. 10.1207/s15327051hci1701_2 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peck, E. M., Carlin, E. & Jacob, R. Designing brain–computer interfaces for attention-aware systems. Computer48, 34–42. 10.1109/MC.2015.315 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afergan, D., Hincks, S. W., Shibata, T. & Jacob, R. J. in International Conference on Augmented Cognition. (eds Afergan, D., Hincks, S. W., Shibata, T & Jacob, R. J. K.) 167–177 (Springer, Cham).

- 18.Sen, S. et al. in 2006 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. (eds Sen, S. et al.) 89–98.

- 19.Trafton, J. G., Altmann, E. M., Brock, D. P. & Mintz, F. E. Preparing to resume an interrupted task: Effects of prospective goal encoding and retrospective rehearsal. Int. J. Hum Comput Stud.58, 583–603. 10.1016/s1071-5819(03)00023-5 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodgetts, H. M. & Jones, D. M. Contextual cues aid recovery from interruption: the role of associative activation. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn.32, 1120–1132. 10.1037/0278-7393.32.5.1120 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falkland, E. C., Wiggins, M. W. & Westbrook, J. Cue utilization differentiates performance in the management of interruptions. Hum. Fact.62, 751–769. 10.1177/0018720819855281 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ratwani, R. M., McCurry, J. M. & Trafton, J. G. in SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. (eds Ratwani, R. M., McCurry, J. M. & Trafton, J. G.) 539–542 (ACM).

- 23.Malin, J. T. et al. Making intelligent systems team players: Case studies and design issues. Volume 1: Human–computer interaction design. (1991).

- 24.Trafton, J. G., Altmann, E. M. & Brock, D. P. in Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. (eds Gregory Trafton, J., Altmann, E. M. & Brock, D. P.) 468–472 (SAGE Publications Sage).

- 25.Chung, P. H. & Byrne, M. D. Cue effectiveness in mitigating postcompletion errors in a routine procedural task. Int. J. Hum Comput Stud.66, 217–232. 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2007.09.001 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones, S. A., Gould, S. J. & Cox, A. L. in 26th annual BCS interaction specialist group conference on people and computers. (eds Jones, S. A, Gould, S. J. J. & Cox, A. L.) 251–256 (British Computer Society).

- 27.Alonso, V. & De La Puente, P. System transparency in shared autonomy: A mini review. Front. Neurorobot.12, 83 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van de Merwe, K., Mallam, S. & Nazir, S. Agent transparency, situation awareness, mental workload, and operator performance: A systematic literature review. Hum. Fact.66, 180–208 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, T. et al. Research on mental fatigue during long-term motor imagery: A pilot study. Sci. Rep.14, 18454 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen, Y., Fang, W., Guo, B. & Bao, H. The moderation effects of task attributes and mental fatigue on post-interruption task performance in a concurrent multitasking environment. Appl. Ergon.102, 103764. 10.1016/j.apergo.2022.103764 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen, Y., Fang, W., Guo, B. & Bao, H. Fatigue-related effects in the process of task interruption on working memory. Front. Hum. Neurosci.15, 703422. 10.3389/fnhum.2021.703422 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van der Linden, D., Frese, M. & Meijman, T. F. Mental fatigue and the control of cognitive processes: Effects on perseveration and planning. Acta Physiol. (Oxf)113, 45–65. 10.1016/S0001-6918(02)00150-6 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorist, M. M. et al. Mental fatigue and task control: Planning and preparation. Psychophysiology37, 614–625. 10.1017/s004857720099005x (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falkland, E. C., Wiggins, M. W. & Westbrook, J. I. Interruptions versus breaks: The role of cue utilisation in a simulated process control task. Appl. Cogn. Psychol.35, 473–485. 10.1002/acp.3766 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santiago-Espada, Y., Myer, R. R., Latorella, K. A. & Comstock, J. R. Jr. The Multi-Attribute Task Battery II (MATB-II) Software for Human Performance and Workload Research: A User’s Guide (National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan, B. et al. Individual differences in multitasking ability and adaptability. Hum. Fact.55, 776–788. 10.1177/0018720812470842 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinss, M. F. et al. Open multi-session and multi-task EEG cognitive dataset for passive brain–computer interface applications. Sci. Data10, 85 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirshfield, L., Costa, M., Bandara, D. & Bratt, S. in Foundations of Augmented Cognition: 9th International Conference, AC 2015, Held as Part of HCI International 2015, Los Angeles, CA, USA, August 2–7, 2015, Proceedings 9. 244–255 (Springer).

- 39.Kennedy, L. & Parker, S. H. in International Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care. (eds Kennedy, L. & Parker, S. H.) 201–208 (SAGE Publications Sage).

- 40.Kern, D., Marshall, P. & Schmidt, A. in SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. (eds Kern, D., Marshall, P. & Schmidt, A.) 2093–2102.

- 41.Marcora, S. M., Staiano, W. & Manning, V. Mental fatigue impairs physical performance in humans. J. Appl. Physiol.106, 857–864. 10.1152/japplphysiol.91324.2008 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shahid, A., Wilkinson, K., Marcu, S. & Shapiro, C. M. in STOP, THAT and one Hundred Other Sleep Scales (eds Shahid, A., Wilkinson, K., Marcu, S. & Shapiro, C. M.) 399–402 (Springer, 2011).

- 43.Hruby, T. & Marsalek, P. Event-related potentials-the P3 wave. Acta Neurobiol. Exp.63, 55–63 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riddle, J., Scimeca, J. M., Cellier, D., Dhanani, S. & D’Esposito, M. Causal evidence for a role of theta and alpha oscillations in the control of working memory. Curr. Biol.30, 1748–1754. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.02.065 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao, X., Li, X. & Yao, L. Localized fluctuant oscillatory activity by working memory load: a simultaneous EEG-fMRI study. Front. Behav. Neurosci.11, 00215. 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00215 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wöstmann, M., Alavash, M. & Obleser, J. Alpha oscillations in the human brain implement distractor suppression independent of target selection. J. Neurosci.39, 9797–9805. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1954-19.2019 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boksem, M., Meijman, T. F. & Lorist, M. M. Effects of mental fatigue on attention: An ERP study. Cogn. Brain Res.25, 107–116. 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.04.011 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prada, L., Barceló, F., Herrmann, C. S. & Escera, C. J. P. EEG delta oscillations index inhibitory control of contextual novelty to both irrelevant distracters and relevant task-switch cues. Psychophysiology51, 658–672. 10.1111/psyp.12210 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiggins, M. W. A behaviour-based approach to the assessment of cue utilisation: Implications for situation assessment and performance. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci.22, 46–62. 10.1080/1463922X.2020.1758828 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasangohar, F., Scott, S. D. & Cummings, M. L. Supervisory-level interruption recovery in time-critical control tasks. Appl. Ergon.45, 1148–1156. 10.1016/j.apergo.2014.02.005 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson, J. R. & Douglass, S. Tower of Hanoi: Evidence for the cost of goal retrieval. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn.27, 1331–1381. 10.1037/0278-7393.27.6.1331 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anderson, J. R. & Schooler, L. J. Reflections of the environment in memory. Psychol. Sci.2, 396–408. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1991.tb00174.x (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lundwall, R. A., Woodruff, J. & Tolboe, S. P. RT slowing to valid cues on a reflexive attention task in children and young adults. Front. Psychol.9, 1324. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pacheco-Unguetti, A. P., Acosta, A., Callejas, A. & Lupiáñez, J. Attention and anxiety: Different attentional functioning under state and trait anxiety. Psychol. Sci.21, 298–304. 10.1177/0956797609359624 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braver, T. S. The variable nature of cognitive control: A dual mechanisms framework. Trends Cogn. Sci.16, 106–113. 10.1016/j.tics.2011.12.010 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braver, T. S., Kizhner, A., Tang, R., Freund, M. C. & Etzel, J. A. The dual mechanisms of cognitive control project. J. Cogn. Neurosci.33, 1990–2015 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holtzer, R. et al. Cognitive fatigue defined in the context of attention networks. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn.18, 108–128. 10.1080/13825585.2010.517826 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li, M. L., Zhang, L. W., Qu, Z. Y. & Sun, J. X. The Effects of mental fatigue on cognitive control and the moderating role of reward. 39, 36-47, 10.16469/j.css.201906005 (2019).

- 59.Jensen, O. & Tesche, C. D. Frontal theta activity in humans increases with memory load in a working memory task. Eur. J. Neurosci.15, 1395–1399. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01975.x (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tran, Y., Craig, A., Craig, R., Chai, R. & Nguyen, H. The influence of mental fatigue on brain activity: Evidence from a systematic review with meta-analyses. Psychophysiology57, e13554. 10.1111/psyp.13554 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kool, W., McGuire, J. T., Rosen, Z. B. & Botvinick, M. M. Decision making and the avoidance of cognitive demand. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen.139, 665. 10.1037/a0020198 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data for all experiments are available at https://osf.io/vfwcq/files/osfstorage.