Abstract

As the key material for the all‐solid‐state batteries (ASSBs), solid electrolytes (SEs) have attracted increasing attention. Recently, a novel design strategy−high‐entropy (HE) approach is frequently reported to improve the ionic conductivity and electrochemical performance of SEs. However, the fundamental understandings on the HE working mechanism and applicability evaluation of HE concept are deficient, which would impede the sustainable development of a desirable strategy to enable high‐performance SEs. In this contribution, the essence of HE‐related approaches and their positive effects on SEs are evaluated. The reported HE strategy stems from complex compositional regulations. The derived structural stability and enhanced property are originally from the modulated system disorder and subtle local‐structure evolutions, respectively. While HE ardently describes the increased entropy/disorder during the modification of prevailing SEs, rigorous experimental formulations, and direct correlations between the HE structures and desired properties are necessary to be established. This perspective would be a timely and critical overview for the HE approaches in the context of SEs, aiming to stimulate further discussion and exploration in this emerging research direction.

Keywords: high‐entropy materials, ion migration, Li superionic conductors, solid electrolytes, solid‐state batteries

This perspective critically examines HE approaches in SEs, highlighting how compositional complexity induces system disorder and local‐structure evolution to enhance stability and properties. While HE concepts are attractive, establishing rigorous structure‐property relationships requires further investigation. The discussion aims to guide future research in this promising field by clarifying key challenges and opportunities in HE‐based electrolyte design.

1. Introduction

Solid electrolytes (SEs) are one of the most important materials that can dominate the development of all‐solid‐state batteries (ASSBs).[ 1 , 2 ] Generally, it is required that SEs can possess high ionic conductivity and chemo‐mechanical stability against both anode and cathode materials.[ 3 , 4 , 5 ] Structural innovations on the SEs, as fundamental in developing superionic conductors, play an essential role to realize those desirable properties.[ 6 , 7 ] Experiencing a long history of upgrading SEs in terms of pursuing superionic conductivity, various kinds of SEs have been developed within three main chemistries: oxide, sulfide, and halide.[ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ] In each type of these inorganic SEs, to fulfill specific objectives of structural manipulation, the constitution has become increasingly complex via single/multiple elements (anions or cations) doping or substitution approaches.[ 6 , 14 ]

In this context, the high‐entropy (HE) strategy has been gradually employed as a novel approach for developing high‐performance SEs with stabilized structure,[ 15 , 16 , 17 ] high ionic conductivity,[ 18 , 19 , 20 ] electrode compatibility,[ 21 , 22 ] and other physiochemical properties.[ 23 , 24 , 25 ] However, the implementation of HE strategy in the field of developing SEs is still lacking a solid theoretical foundation, and the working mechanism underlying the enhanced property is ambiguous. From the very beginning, the scientific term of “high entropy” was coined by Jein‐Wei Yeh to describe metal alloys with high compositional complexity (always involving five elements or more).[ 26 , 27 ] The increased configurational entropy, quantified as ≥ 1.5R (R is the gas constant) is essential to form HE alloys,[ 24 , 28 ] where multiple element constituents are mixed at one crystallographic site. By this way, unexpected properties, such as strength, hardness, thermostability, and corrosion resistance can be tuned according to the so called “cocktail effect”.[ 28 , 29 ] The cocktail effect describes the synergistic interactions among multiple principal elements in a single material, leading to enhanced or emergent properties unattainable by any individual element alone.[ 24 ] It emerges from the complex interplay of the individual components, leading to unpredictable overall system behavior. Therefore, the selection of multiple elements is very important in HE designs. The selection of constituent elements for HE materials should follow several fundamental criteria: 1) atomic radii within a reasonable range to balance lattice distortion and stability; 2) earth‐abundant substitutes for scalability; 3) preference for simple crystal structures; and 4) moderate electronegativity differences to avoid phase separation.[ 30 ] These principles ensure optimal property enhancement while maintaining structural integrity and practical feasibility.

Recently, the HE strategy has been extended to develop energy storage materials with excellent structural stability,[ 31 , 32 , 33 ] as well as various kinds of liquid[ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ] or polymer‐based electrolytes with high structural disorders.[ 39 , 40 , 41 ] These functionalities originated from the entropy‐stabilization effect or high degree of disorder that was triggered by HE designs. Regarding high‐entropy solid electrolytes (HESEs), as displayed in Figure 1 , typical HESEs showing flexible composition designs and entropic disorder have been demonstrated to induce several direct effects on stabilizing crystal structure, improving Li‐ion percolation, and enhancing critical physicochemical properties.[ 19 , 20 , 24 , 25 ] Among them, the HE‐induced structural stability is based on the theory of Gibbs free energy (ΔG = ΔH–TΔS). A higher entropy (ΔS) is prone to cause more negative ΔG and benefits the generation of entropy stabilization. In this context, while generally ascribing the increased ionic conductivity or other achieved properties to the established HE effect (site disorder or favorable local structure) is plausible, its relation to the entropy‐stabilized structure lacks necessary verification.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the structure of HESEs and the HE‐derived properties, as well as their potential interconnections.

In this perspective, we explore the origin of the HE approaches and its potential impact on SEs. We first overview the basic knowledge about HESEs, clarifying the relations between HE and two close concepts: disorder and compositional complexity. Subsequently, we discuss the latest advancement of HE strategies acting on improving Li‐ion transport and physicochemical properties. Based on these, we propose challenges and concerns regarding developing HESEs. Finally, we conclude with a summary and appeal for necessary research details on HESEs.

2. History of Involving Term “Entropy” to Develop SEs

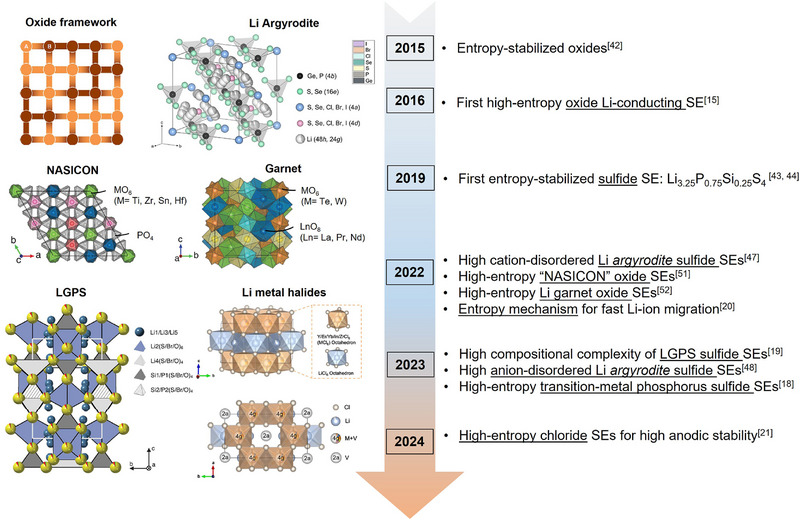

We retrospect the development of SEs that involves the concept of “entropy” as displayed in Figure 2 . Based on the HE oxide material (Mg, Cu, Ni, Co, and Zn)O developed by Maria and co‐workers,[ 42 ] Dragoe et al. reported the first case of Li/Na‐ion conducting HESEs in 2016.[ 15 ] The materials were prepared via air quenching from 1000 °C and showed a single phase with the rock salt structure. Aliovalent element doping (e.g., Li, Na with +1 valence) induced the formation of O vacancies that were regarded to promote the conduction of Li+ and Na+, showing optimized ionic conductivities up to 10−3 and 10−6 S cm−1 at 20 °C, respectively.[ 15 ] Afterward, the progress of developing HESEs slackened; there was only one report about using entropy stabilization to realize metastable “β‐Li3PS4” structure in the Li3.25P0.75Si0.25S4 sulfide SE at an ambient condition in 2019.[ 43 , 44 ] Until 2022, reports about the HE strategy for SEs started surging,[ 45 ] which has been demonstrated as an effective method to improve the ion migration in either ionic conductivity or activation energy (Ea) for a series of typical superionic conductors, such as Li‐Argyrodite and thiophosphate sulfides,[ 18 , 19 , 22 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ] sodium superionic conductor (NASICON) and garnet‐type oxides,[ 16 , 20 , 51 , 52 , 53 ] as well as lithium metal halides.[ 21 , 23 , 54 ] Among these reports, in addition to improving ion migration, critical issues, such as air sensitivity, inflated cost, and insufficient oxidation limit of specific SEs, were also alleviated via using the HE strategy.

Figure 2.

History of involving “entropy” to develop SEs. The crystal structures of cubic oxide framework, Reproduced with permission.[ 42 ] Copyright 2014, Springer Nature; Li Argyrodite sulfide, Reproduced with permission.[ 55 ] Copyright 2022, The American Chemical Society; NASICON oxide, Reproduced with permission.[ 20 ] Copyright 2022, AAAS; Li Garnet oxide, Reproduced with permission.[ 20 ] Copyright 2022, AAAS; LGPS‐type sulfide, Reproduced with permission.[ 19 ] Copyright 2023, AAAS; Li metal halide, Reproduced with permission.[ 21 ] Copyright 2024, Springer Nature, are illustrated. The transition metal phosphorus sulfide SEs represents Li x (Fe1/5Co1/5Ni1/5Mn1/5Zn1/5)PS3. Reproduced with permission.[ 18 ] Copyright 2023, The American Chemical Society.

3. High Entropy and Disorder Toward Stabilized Structure of SEs

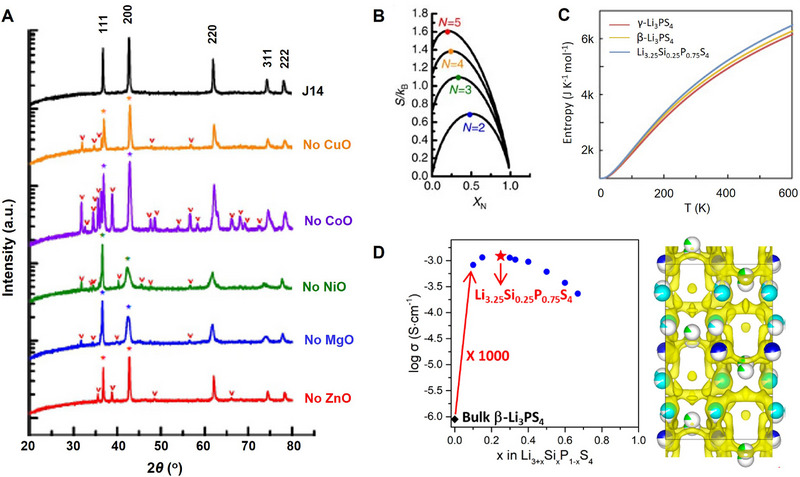

The entropy stabilization is one of the most recognized effects that increased configurational entropy can deliver on the structure of the material, which is a widely accepted motivation to develop HE‐based materials,[ 24 , 42 ] although factors other than the configurational entropy could also contribute to stabilizing the structure.[ 56 ] An entropy‐stabilized (or entropy‐selected) material exhibits a positive reaction enthalpy, requiring environmental heat absorption to offset this unfavorable energy change and drive the formation of an entropically favored state. Consequently, the hallmark of entropy stabilization is an endothermic phase transformation from constituent components to a single‐phase material. In the case of (Mg0.2Cu0.2Ni0.2Co0.2Zn0.2)O HE‐based oxide material, the authors demonstrated that removing any component oxide resulted in multiple phases (Figure 3A).[ 42 ] They further verified the entropy increased as new species were added and the maximum entropy was achieved when all the species have the same fraction (Figure 3B). The equimolarity of five starting materials was also verified to lead to the lowest transformation temperatures.[ 42 ] These results mean that the maximized entropy benefits form a target single phase with a thermodynamically preferred structure. Actually, entropy serves as a parameter reflecting the level of disorder within a system at the atomic, ionic, or molecular scale; with higher disorder correlating to greater entropy.[ 17 ] From a technical standpoint, entropy is also defined as a thermodynamic property, providing a measure of a system's proximity to equilibrium; that is to perfect internal disorder.[ 28 ] The high‐entropy‐stabilized structural stability was recently demonstrated in the Li6.2La3(Zr0.2Hf0.2Ti0.2Nb0.2Ta0.2)2O12 (Li‐Garnet) for excellent air stability.[ 16 ]

Figure 3.

Entropy‐stabilized structure. A) X‐ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of a series of compositions where individual components are removed from the parent composition of (Mg0.2Cu0.2Ni0.2Co0.2Zn0.2)O. Reproduced with permission.[ 42 ] Copyright 2015, Springer Nature. Asterisks identify peaks from rock salts; carrots identify peaks from other impurities. B) Calculated configurational entropy in an N‐component solid solution as a function of mol% of the Nth component. Reproduced with permission.[ 42 ] Copyright 2015, Springer Nature. C) Entropy of γ‐Li3PS4, β‐Li3PS4, and Li3.25(Si0.25P0.75)S4 from Phonon Calculations. Reproduced with permission.[ 44 ] Copyright 2020, Elsevier Inc. D) Crystal structures of orthorhombic Li3.25(Si0.25P0.75)S4 and β‐Li3PS4 along [010]. Reproduced with permission.[ 43 ] Copyright 2019, The American Chemical Society.

Nevertheless, the entropically stabilized electrolyte structure could be realized in a system where the entropy is not necessary to reach a maximum.[ 43 , 44 ] That is to say, materials can also be entropy‐stabilized without exceeding the 1.5R threshold. As shown in Figure 3C, Si‐substituted β‐Li3PS4 (Li3.25P0.75Si0.25S4) shows higher entropy than metastable β‐Li3PS4 and stable γ‐Li3PS4 (low‐temperature phase in three Li3PS4 isomers) in a wide range of 0−600 K.[ 44 ] The entropy‐stabilized Li3.25P0.75Si0.25S4 SEs (β‐phase) present multiple Li splitting sites comparing to the pristine β‐Li3PS4 (Figure 3D), delivering a high ionic conductivity of 1.22 mS cm−1 at room temperature, which is 1000 times higher than that of the β‐Li3PS4 SEs. [ 43 ]

4. High Entropy and High Compositional Complexity

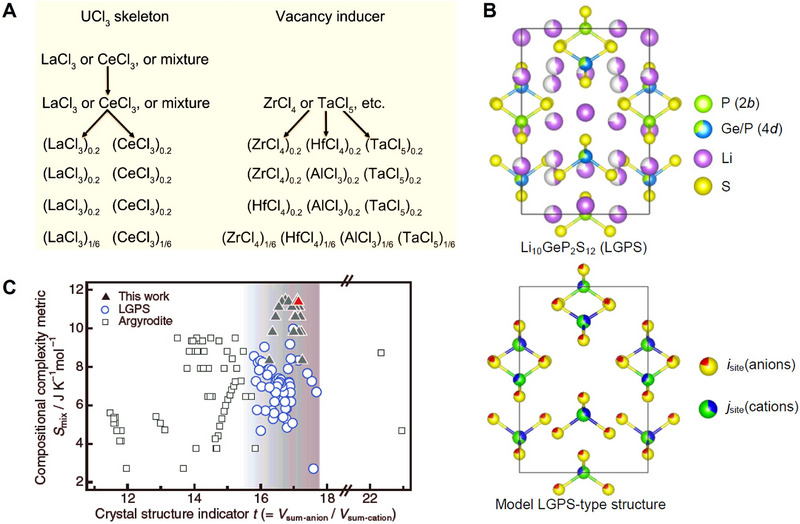

The implementation of HE strategy is based on achieving high compositional complexity (HCC),[ 19 ] because multiple elements (more than five cations or anions) co‐occupy the same equivalent crystallographic site in one single structure. However, the actual situation is that HCC is always reported in developing SEs with increased configurational entropy; while strictly speaking, it cannot belong to the scope of HE. Taking the UCl3‐type halide SEs (with abundant accommodating space)[ 57 , 58 ] as an example, Sun et al. investigated the functionality of compositional complexity on ionic conductivity.[ 59 ] As shown in Figure 4A, considering the cost, abundance, and structure of the raw materials, LaCl3 and CeCl3 were first selected as the UCl3 skeleton materials. Multiple high‐valence metal chlorides were selected as the vacancy inducer and disorder enhancer to provide essential conditions for fast Li‐ion transport. As a result, several five‐component (with equal molarity) UCl3‐type SEs were achieved with high ionic conductivities of over 10−3 S cm−1. However, it was challenging to calculate the configurational entropy induced by the multi‐cation design, because of the unidentified cation sites in the complex composition.

Figure 4.

High‐compositional‐complexity design of SEs. A) Prototype composition design of UCl3‐type chloride SSEs with different numbers of TM species. Reproduced with permission.[ 59 ] Copyright 2022, Wiley‐VCH GmbH. B) Crystal structure and the derived model structure of the LGPS superionic conductor for calculating configurational entropy for the mixed anions and cations (Smix ). Reproduced with permission.[ 19 ] Copyright 2023, AAAS. C) Relationship between the crystal structure indicator (t, volume ratio of anions to cations) and compositional complexity metric (Smix ) for LGPS‐type (open circles) and Argyrodite‐type (open squares) electrolytes. Reproduced with permission.[ 19 ] Copyright 2023, AAAS.

Beginning with Boltzmann's fundamental entropy formula, S = k BlnΩ, we derive the number of microstates (Ω) associated with the configurational entropy (Sconf ) of multiple elements occupying the same crystallographic site. By first considering the number of ways to distribute nk particles of type k across N = ∑ k nk states, we obtain the combinatorial factor Ω = N!/∏ k nk !, from which the entropy follows:

| (1) |

Through Stirling's approximation for Equation (1), we can obtain

| (2) |

where R is the gas constant (R = 8.314 J K−1 mol−1), and ck = nk /N, is the percentage of multiple site species k among all species at the same site.

Furthermore, in a HE materials with both anion and cation joint modification (including doping, substitution, etc.), the calculation of configurational entropy for mixed anions and cations (Smix ) can follow Equation (3).[ 31 ]

| (3) |

where ci (cj ) is the number percentage of anion species i (cation species j) among all anions (cations) and n (m) is the number of anion (cation) species, according to the nominal composition. Theoretically, this equation is only applicable to HE materials with a crystal structure containing only one type of anion/cation crystallographic site (e.g., a rock‐salt structure).

However, for a superionic conductor, the structure is always highly complicated compared to the rock‐salt structure. It is quite common to have multiple cation or anion sites in a superionic crystal structure and the complexity becomes more unidentified when the superionic conductor is amorphous or contains polymers. This issue has become a main obstacle to quantify/estimate the entropy (Smix or Sconf ) reasonably via using the typical calculation method. Kanno et al. figured out this problem via simplifying the crystal structure with a model structure,[ 19 ] in which one type of anion (cation) site is randomly occupied by the constituent anion (cation) atoms, as shown in Figure 4B. By this way, the entropy of the multiple site substitutions in the LGPS structure can be calculated as shown in Figure 4C. While the highest ionic conductivity of 32 mS cm−1 occurs to the Li9.54[Si0.6Ge0.4]1.74P1.44S11.1Br0.3O0.6 (LSiGePSBrO) sample with high compositional complexity, the calculated Smix has not reached 1.5R, which means the HE concept is not adaptable to this material.[ 24 ] Even extending to the Li Argyrodite family, none of the HCC‐based SEs could achieve a high‐entropy benchmark of more than 1.5R, but this did not impede the increase of ionic conductivity toward over 10 mS cm−1 via specifically structural modifications.[ 60 , 61 ] Therefore, it is inferred that HE could be a special situation of the HCC, and the increased ionic conductivity could be a result of structural optimization originating from the target‐orientated structural designs (e.g., HCC routes) rather than directly relating to the expression of HE.

5. High Entropy Correlating to Ionic Conductivity

Ceder and co‐workers, for the first time, established the connection between HE strategy and improved Li‐ion percolation, where the high‐entropy‐induced structural distortions and cation disorders play important roles.[ 20 ] As illustrated in Figure 5A, in a well‐ordered structure, there are two sites with distinct site energy (e.g., sites 1 and 2). Introducing chemical disorder by multiple‐element modification in one superionic structure can cause distortions and locally perturb the site energy, thus creating a distribution of site energies. When this distribution is wide enough for the energy of neighboring sites to overlap, ion hopping between them will be promoted and the macroscopic diffusion is enhanced eventually.[ 20 ] Therefore, the increased site disorder can be regarded as the essence of the HE‐related strategy (including increasing the composition complexity) for improved ionic conduction. The HE‐induced high ionic conductivity is not only reported in HE‐based oxide SEs, but also verified by Yang et al. in the LixMPS3 sulfide system.[ 18 ] HE‐Lix(Fe1/5Co1/5Ni1/5Mn1/5Zn1/5)PS3 with five equal‐molarity transition‐metal elements exhibits high lattice distortions and a large amount of cation vacancies, delivering a much‐improved ionic conductivity comparing to the low/medium entropy composition with less metal elements incorporated.

Figure 5.

High entropy correlating to ionic conductivity. A) Schematic showing how local distortions create overlapping site‐energy distributions. Reproduced with permission.[ 20 ] Copyright 2022, AAAS. B) Correlation between configurational entropy calculated from the specific occupancies of the anion sublattice and ionic conductivity. Reproduced with permission.[ 48 ] Copyright 2023, Wiley‐VCH GmbH. C) Schematic view of the crystal structure and summary plot of the ionic conductivities at 25 °C of three HE Li‐Argyrodite SEs (HEAR1: Li6PS5[Cl0.33Br0.33I0.33], HEAR2: Li6P[S2.5Se2.5][Cl0.33Br0.33I0.33], HEAR3: Li6.5[Ge0.5P0.5][S2.5Se2.5][Cl0.33Br0.33I0.33]). Reproduced with permission.[ 55 ] Copyright 2022, The American Chemical Society.

In the Li Argyrodite family, the site disorder between X− (X = Cl, Br, I) and S2− at Wyckoff position 4c was revealed by Zeier et al. early to 2017 as the main reason for the superionic conductivity (10−3 S cm−1) achieved in Li6PS5X (X = Cl, Br) and their derived Argyrodite‐type SEs.[ 62 , 63 , 64 ] Wang et al. recently employed the metric of Sconf to quantify the disorder of X−/S2− as displayed in Figure 5B.[ 48 , 65 ] Although only three elements are involved, the calculated Sconf can be as high as 1.98R for the Li5.5PS4.5Cl0.8Br0.7 composition, showing a feature of “HE” and delivering an ultrahigh ionic conductivity of 9.6 mS cm−1 (cold pellet).[ 48 ] Almost at the same time, Yao et al. reported that cation/anion joint doping further increased the entropy of Li6P0.85Si0.05Ge0.05Sn0.05S4.5BrCl0.5 to 2.29R,[ 22 ] while the ionic conductivity (7.96 S cm−1) could not show increased compared with the Li5.5PS4.5Cl0.8Br0.7 that was solely tuned on anion sites. Furthermore, it is worth noting that a high‐site disorder could not necessarily be generated in the modified Li‐Argyrodite SEs via the HE strategy.[ 55 , 66 ] As shown in Figure 5C, in the first HE study about Li‐Argyrodite SEs, although the Sconf of multiple anion/cation substitution could be as high as 2.98R for the Li6.5[Ge0.5P0.5][S2.5Se2.5][Cl0.33Br0.33I0.33] composition and the resultant activation energy (Ea) was reduced to 0.22 eV, there was a minor change in the site disorder (26–33%) and achieved ionic conductivity.[ 55 ] The reason might be related to the Ea‐correlated pre‐exponential factor (positive correlation), which displayed a negative effect on the ionic conductivity accompanying increased Sconf .[ 55 ] Despite achieving an ultrahigh conductivity of 13 mS cm−1 for an HE composition of Li6.5[P0.25Si0.25Ge0.25Sb0.25]S5I (2.03R),[ 47 ] further evaluation of this material's advancement originating from the HE design is suggested. This assessment should consider several earlier reported Li‐Argyrodite SEs with simpler compositions. For instance, Li6.6Si0.6Sb0.4S5I was reported to exhibit an ionic conductivity of 15 mS cm−1 when in the form of a cold‐pressed pellet.[ 60 ]

Overall, through investigating the case of Li Argyrodite SEs, we can infer that structural distortion or site disorder can be achieved not only through high‐entropy (HE) strategies but also through conventional element doping/substitution approaches designed to engineer favorable material structures. In fact, many reported systems demonstrate high degrees of disorder without employing HE design principles. In this regard, we appeal that it is not suggested to hastily ascribe the improved ionic conductivity to the HE strategy directly, but the origin of the improved ionic conductivity achieved by compositional and structural designs should be carefully investigated case by case.

6. High Entropy and Other Physicochemical Properties

In addition to the ionic conduction, the HE strategy has been reported to improve other essential properties (e.g., high‐voltage stability).[ 21 , 54 ] Luo et al. used HE design in the structure of Li3InCl6 (LIC) to introduce local lattice distortion with confined distribution of Cl−, which effectively curbs the kinetics of the Cl− oxidation.[ 21 ] As a result, the HE composition of Li2.75Y0.16Er0.16Yb0.16In0.25Zr0.25Cl6 (HE‐LIC) shows low reactivity at high voltages, and the solid cells using HE‐LIC can support a high‐voltage application of 4.6 V (vs Li+/Li).[ 21 ] Wan et al. further advanced the upper limit of charging voltage to 5.5 V by tuning the HE composition to Li2.2In0.2Sc0.2Zr0.2Hf0.2Ta0.2Cl6.[ 54 ] Nevertheless, whether the multiple‐cation doping can improve the oxidation limit is still disputable in the sulfide‐based HESEs with multiple cation elements. Studies by Zeier et al. demonstrated that cation substitutions for phosphorus (P) sites in Li‐argyrodite sulfide solid electrolytes fail to improve their anodic stability. The fundamental reason is associated with the valence band edges that can determine the oxidation limit and are mostly dominated by nonbonding orbitals of the PS4 3− units or unbound S2− anions.[ 67 ] The underlying factor for the oxidation limit in SEs is closely related to the strength of the M−S bond, which can be simplified and expressed as ionic potential φ of M (φ is calculated with the ratio of the electrical charge z to the ionic radius r). A higher ionic potential indicated a greater bond strength, corresponding to a higher oxidation potential.[ 68 ] Therefore, P (φ = 29.41 Å−1) in the typical sulfide SEs substituted by Si (φ = 15.38 Å−1) or Ge (φ = 10.26 Å−1) was ever verified with a decreased oxidation potential.[ 69 ]

In addition, the high‐voltage stability in solid cells could also be possibly due to the kinetically stabilized cathode interface (chlorinated) and the low electronic conductivity of the SEs. Nazar et al. reported that using the Li2In1/3Sc1/3Cl4 halide SE, the solid cell with a Ni‐rich cathode demonstrated excellent high‐voltage cycling stability reaching up to 4.8 V.[ 70 ] In their study, the electronically insulating and mechanically robust interphase was critical to achieving exceptional high‐voltage durability. Thus, we anticipate that the improved high‐voltage stability observed with high‐entropy halide SEs likely stems from multiple factors, not solely the high entropy‐induced effect. Lastly. HE strategy was also reported to reduce the surface energy and energy distribution, leading to smaller and more spherical particles with a relatively smooth surface, which showed a distinct comparison to the lamellar stacking morphology of LIC.[ 23 ] This HE‐induced advantageous morphology could improve the compactness of SE pellet and long‐range Li‐ion transport, thus enhancing the cycling performance of solid cells.[ 23 ]

7. Challenges

Through elucidating the origin of the HE strategy and overviewing the recent progress on the reported HESEs, we propose three significant challenges that require urgent attention for further advancement in this emerging field.

1) Quantification of the entropy. Identification of all element sites or distribution (including the Li sites) in HESEs is highly recommended to be performed prior to calculating the entropy value based on multiple‐site considerations. This would become more complicated for amorphous, or polymer‐based HESEs, resulting in a lack of basic entropy calculation in the majority of reports. To the best of our knowledge, in those publications about HE‐based polymers, the terms of high entropy, disorder, and complexity have been used interchangeably. While a simplified model could be employed to merge affiliated sites reasonably, it remains uncertain whether this approach might lead to any deviations in results.

2) Recognition of credit in HE designs stems from the overall composition rather than specific element(s). HE represents the special manifestation of compositional regulation. However, current research lacks detailed comparisons between the composition of HE and other non‐HE compositions (i.e., medium/low entropy) regarding resultant properties. This necessitates extensive sample preparations and subsequent advanced characterizations. Moreover, we may need to consider the situation deviating from equiatomic compositions. Under these circumstances, the number of samples studied would increase exponentially, which are time‐consuming and of high cost. The high‐throughput studies[ 71 , 72 ] could be a solution to improve the analysis efficiency and provide guidance for mechanism understanding.

3) Accurately characterizing the multi‐element composition of HESEs presents significant analytical challenges, particularly when measuring the elements with similar chemical properties that resist differentiation through conventional microscopy or spectroscopy. The development of high‐performance HESEs depends on understanding the local environment of each component element and interatomic distances. However, these characteristics often exceed the resolution limits even when using advanced characterization tools (e.g., synchrotron‐related techniques, and neutron scattering for rare earth elements). To overcome these limitations and enable precise control of material properties, the field requires either innovative characterization approaches or substantial improvements to existing methodologies, which will prove essential for advancing both fundamental understanding and practical applications of HESEs.

8. Summary and Outlook

The HE strategy has been frequently reported to achieve improved ionic conduction and other essential properties of various kinds of SEs. The development of HESEs has become an emerging research direction, receiving unprecedented attention. However, research in this area remains in its nascent stage, marked by deficient fundamental understandings and explanations behind observed phenomena. It is still lacking sufficient evidence showing that low/medium‐entropy composition cannot cause a similar effect induced by the reported HE strategy, necessitating substantial efforts for further identification. For the sustainable development of SEs employing the HE strategy, alongside the three major challenges we have highlighted, several necessary considerations listed below are suggested (Figure 6 ). These considerations are also expected to extend to research areas beyond SEs that utilize the HE strategy.

Figure 6.

Key design considerations for developing high‐entropy solid electrolytes.

1) To avoid misuse, it is crucial to distinguish the “high entropy” from closely related terms such as “disorder” and “compositional complexity”. The calculation of entropy in the developed system offers fundamental information to identify HE. Following recent review papers,[ 24 , 73 ] we adopt the widely recognized threshold of Sconf ≥ 1.5R to define high entropy. While this criterion is empirically derived and somewhat simplified (involving rounded values), it serves as an effective benchmark—clearly distinguishing HE materials from conventional multicomponent systems while minimizing ambiguity. It is encouraged that all future work on HESEs provides entropy values before asserting the HE strategy. Otherwise, the discussion may only pertain to disorder or compositional regulation.

2) Exploring the essence of property enhancement induced by HE and avoiding exaggeration is essential. In most cases, HE designs represent a specialized methodology falling under multiple‐element doping/substitution. It is not suggested to attribute performance enhancement solely to the HE strategy. Instead, conducting detailed contrast experiments is necessary to eliminate potential effects from specific elements or combinations. This process forms the foundation for rigorously discerning whether functionality is originally from increasing entropy or other structural factors.

3) Analyzing sublattices is inevitable given the HE strategy can improve the ionic conduction. This includes two aspects: a) the entropy calculation of HESEs should cover the Li sites comprehensively in the Li sublattice; and b) the connection between the non‐Li anion sublattices and Li‐ion migration should be well established. By addressing these aspects, a more convincing argument can be reached regarding the effectiveness of the HE strategy in enhancing ionic conduction.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Canada Research Chair Program (CRC), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), and Western University. F.Z. acknowledged the support from Mitacs Elevate Postdoc program (Reference number: IT34824).

Zhao F., Zhang S., Sun X., A Perspective on the Origin of High‐Entropy Solid Electrolytes. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2501544. 10.1002/adma.202501544

References

- 1. Janek J., Zeier W., Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 230. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meng Y., Srinivasan V., Xu K., Science 2022, 378, 1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao Q., Stalin S., Zhao C., Archer L., Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 229. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Banerjee A., Wang X., Fang C., Wu E., Meng Y., Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang Q., Soham D., Liang Z., Wan J., Med‐X 2025, 3, 3. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feng X., Fang H., Wu N., Liu P., Jena P., Nanda J., Mitlin D., Joule 2022, 6, 543. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liang J., Li X., Adair K., Sun X., Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang C., Fu K., Kammampata S., Mcowen D., Samson A., Zhang L., Hitz G., Nolan A., Wachsman E., Mo Y., Thangadurai V., Hu L., Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 4257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zuo D., Yang L., Zou Z., Li S., Feng Y., Harris S., Shi S., Wan J., Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2301540. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tan D., Meng Y., Jang J., Joule 2022, 6, 1755. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang S., Zhang W., Chen X., Das D., Ruess R., Gautam A., Walther F., Ohno S., Koerver R., Zhang Q., Zeier W., Richter F., Nan C., Janek J., Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2100654. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xia W., Zhao Y., Zhao F., Adair K., Zhao R., Li S., Zou R., Zhao Y., Sun X., Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li X., Liang J., Yang X., Adair K., Wang C., Zhao F., Sun X., Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 1429. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohno S., Banik A., Dewald G., Kraft M., Krauskopf T., Minafra N., Till P., Weiss M., Zeier W., Prog. Energy 2020, 2, 022001. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bérardan D., Franger S., Meena A., Dragoe N., J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 9536. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Han S., Wang Z., Ma Y., Miao Y., Wang X., Wang Y., Wang Y., J. Adv. Ceram. 2023, 12, 1201. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dragoe N., Bérardan D., Science 2019, 366, 573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao Q., Cao Z., Wang X., Chen H., Shi Y., Cheng Z., Guo Y., Li B., Gong Y., Du Z., Yang S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 21242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li Y., Song S., Kim H., Nomoto K., Kim H., Sun X., Hori S., Suzuki K., Matsui N., Hirayama M., Mizoguchi T., Saito T., Kamiyama T., Kanno R., Science 2023, 381, 50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zeng Y., Ouyang B., Liu J., Byeon Y., Cai Z., Miara L., Wang Y., Ceder G., Science 2022, 378, 1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Song Z., Wang T., Yang H., Kan W., Chen Y., Yu Q., Wang L., Zhang Y., Dai Y., Chen H., Yin W., Honda T., Avdeev M., Xu H., Ma J., Huang Y., Luo W., Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li W., Chen Z., Chen Y., Zhang L., Liu G., Yao L., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2312832. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Q., Zhou Y., Wang X., Guo H., Gong S., Yao Z., Wu F., Wang J., Ganapathy S., Bai X., Li B., Zhao C., Janek J., Wagemaker M., Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schweidler S., Botros M., Strauss F., Wang Q., Ma Y., Velasco L., Cadilha Marques G., Sarkar A., Kübel C., Hahn H., Aghassi‐Hagmann J., Brezesinski T., Breitung B., Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 9, 266. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhao X., Fu Z., Zhang X., Wang X., Li B., Zhou D., Kang F., Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 2406. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Balasubramanian N., Yeh J., MRS Bull. 2016, 41, 905. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yeh J., Chen S., Lin S., Gan J., Chin T., Shun T., Tsau C., Chang S., Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299. [Google Scholar]

- 28. George E., Raabe D., Ritchie R., Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 515. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ma Y., Ma Y., Wang Q., Schweidler S., Botros M., Fu T., Hahn H., Brezesinski T., Breitung B., Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 2883. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xiang H., Xing Y., Dai F., Wang H., Su L., Miao L., Zhang G., Wang Y., Qi X., Yao L., Wang H., Zhao B., Li J., Zhou Y., J. Adv. Ceram. 2021, 10, 385. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang R., Wang C., Zou P., Lin R., Ma L., Yin L., Li T., Xu W., Jia H., Li Q., Sainio S., Kisslinger K., Trask S., Ehrlich S., Yang Y., Kiss A., Ge M., Polzin B., Lee S., Xu W., Ren Y., Xin H., Nature 2022, 610, 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ma Y., Ma Y., Dreyer S., Wang Q., Wang K., Goonetilleke D., Omar A., Mikhailova D., Hahn H., Breitung B., Brezesinski T., Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2101342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang B., Zhang Q., Huang H., Pan H., Zhu W., Meng F., Lan S., Liu Y., Wei B., Liu Y., Yang L., Gu L., Chen L., Nan C., Lin Y., Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 956. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang C., Xia J., Cui C., Pollard T., Vatamanu J., Faraone A., Dura J., Tyagi M., Kattan A., Thimsen E., Xu J., Song W., Hu E., Ji X., Hou S., Zhang X., Ding M., Hwang S., Su D., Ren Y., Yang X., Wang H., Borodin O., Wang C., Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 325. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim S., Wang J., Xu R., Zhang P., Chen Y., Huang Z., Yang Y., Yu Z., Oyakhire S., Zhang W., Greenburg L., Kim M., Boyle D., Sayavong P., Ye Y., Qin J., Bao Z., Cui Y., Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 814. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang S., Wang K., Zhang Y., Jie Y., Li X., Pan Y., Gao X., Nian Q., Cao R., Li Q., Jiao S., Xu D., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, 202304411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang Q., Zhao C., Wang J., Yao Z., Wang S., Kumar S., Ganapathy S., Eustace S., Bai X., Li B., Wagemaker M., Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qiu M., Sun P., Han K., Pang Z., Du J., Li J., Chen J., Wang Z., Mai W., Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang H., Wang Y., Huang J., Li W., Zeng X., Jia A., Peng H., Zhang X., Yang W., Energy Environ. Mater. 2024, 7, 12514. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Su Y., Rong X., Li H., Huang X., Chen L., Liu B., Hu Y., Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2209402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. He X., Zhu Z., Wen G., Lv S., Yang S., Hu T., Cao Z., Ji Y., Fu X., Yang W., Wang Y., Adv. Mater. 2023, 36, 2307599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rost C., Sachet E., Borman T., Moballegh A., Dickey E., Hou D., Jones J., Curtarolo S., Maria J., Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhou L., Assoud A., Shyamsunder A., Huq A., Zhang Q., Hartmann P., Kulisch J., Nazar L., Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 7801. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang Z., Li H., Kaup K., Zhou L., Roy P., Nazar L., Matter 2020, 2, 1667. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ouyang B., Zeng Y., Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Strauss F., Lin J., Kondrakov A., Brezesinski T., Matter 2023, 6, 1068. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lin J., Cherkashinin G., Schäfer M., Melinte G., Indris S., Kondrakov A., Janek J., Brezesinski T., Strauss F., ACS Mater. Lett. 2022, 4, 2187. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li S., Lin J., Schaller M., Indris S., Zhang X., Brezesinski T., Nan C., Wang S., Strauss F., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, 202314155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin J., Schaller M., Cherkashinin G., Indris S., Du J., Ritter C., Kondrakov A., Janek J., Brezesinski T., Strauss F., Small 2024, 20, 2306832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lin J., Schaller M., Indris S., Baran V., Gautam A., Janek J., Kondrakov A., Brezesinski T., Strauss F., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, 202404874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu B., Hou G., Kovalska E., Mazanek V., Marvan P., Liao L., Dekanovsky L., Sedmidubsky D., Marek I., Hervoches C., Sofer Z., Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 4092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stockham M., Dong B., Slater P., J. Solid State Chem. 2022, 308, 122944. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Feng Y., Yang L., Yan Z., Zuo D., Zhu Z., Zeng L., Zhu Y., Wan J., Energy Storage Mater. 2023, 63, 103053. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ye Y., Gu Z., Geng J., Niu K., Yu P., Zhou Y., Lin J., Woo H., Zhu Y., Wan J., Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Strauss F., Lin J., Duffiet M., Wang K., Zinkevich T., Hansen A., Indris S., Brezesinski T., ACS Mater. Lett. 2022, 4, 418. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fracchia M., Coduri M., Manzoli M., Ghigna P., Tamburini U., Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fu J., Wang S., Liang J., Alahakoon S., Wu D., Luo J., Duan H., Zhang S., Zhao F., Li W., Li M., Hao X., Li X., Chen J., Chen N., King G., Chang L., Li R., Huang Y., Gu M., Sham T., Mo Y., Sun X., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 145, 2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yin Y., Yang J., Luo J., Lu G., Huang Z., Wang J., Li P., Li F., Wu Y., Tian T., Meng Y., Mo H., Song Y., Yang J., Feng L., Ma T., Wen W., Gong K., Wang L., Ju H., Xiao Y., Li Z., Nature 2023, 616, 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Li X., Xu Y., Zhao C., Wu D., Wang L., Zheng M., Han X., Zhang S., Yue J., Xiao B., Xiao W., Wang L., Mei T., Gu M., Liang J., Sun X., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, 202306433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhou L., Assoud A., Zhang Q., Wu X., Nazar L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 19002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kraft M., Ohno S., Zinkevich T., Koerver R., Culver S., Fuchs T., Senyshyn A., Indris S., Morgan B., Zeier W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kraft M., Culver S., Calderon M., Bocher F., Krauskopf T., Senyshyn A., Dietrich C., Zevalkink A., Janek J., Zeier W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhou R., Gautam A., Suard E., Li S., Ganapathy S., Chen K., Zhang X., Nan C., Wang S., Wagemaker M., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2420971. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang S., Tang M., Zhang Q., Li B., Ohno S., Walther F., Pan R., Xu X., Xin C., Zhang W., Li L., Shen Y., Richter F., Janek J., Nan C., Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2101370. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Strauss F., Wang S., Nan C., Brezesinski T., Matter 2024, 7, 742. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Guo H., Li J., Burton M., Cattermull J., Liang Y., Chart Y., Rees G., Aspinall J., Pasta M., Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 102228. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Banik A., Liu Y., Ohno S., Rudel Y., Jiménez‐Solano A., Gloskovskii A., Vargas‐Barbosa N., Mo Y., Zeier W., ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 2045. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cartledge G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1928, 50, 2863. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Du J., Lin J., Zhang R., Wang S., Indris S., Ehrenberg H., Kondrakov A., Brezesinski T., Strauss F., Batteries Supercaps 2024, 7, 202400112. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhou L., Zuo T., Kwok C., Kim S., Assoud A., Zhang Q., Janek J., Nazar L., Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 83. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ludwig A., npj Comput. Mater. 2019, 5, 70. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Velasco L., Castillo J., Kante M., Olaya J., Friederich P., Hahn H., Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2102301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Aamlid S., Oudah M., Rottler J., Hallas A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 5991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]