Abstract

Aims

Sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim (SMX‐TMP) is a widely used antibiotic for treating bacterial infections, but its safety in adult outpatients remains understudied. This systematic review and meta‐analysis evaluated the safety profile of SMX‐TMP and identified critical research gaps. The pharmacovigilance study aimed to validate and extend findings from meta‐analyses to better understand the real‐world safety of SMX‐TMP.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE and Embase up to 12 August 2024, to identify studies comparing adverse drug events (ADEs) following SMX‐TMP vs. other antibiotics in adult outpatients. Meta‐analyses were performed where data allowed. A pharmacovigilance study using the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System was conducted to supplement our findings.

Results

Our review, which included 43 studies, found SMX‐TMP had a nearly 3‐fold higher risk of rash compared to other antibiotics (pooled risk ratio 2.56, 95% confidence interval [1.69, 3.89], I 2 = 0%, n = 4458 participants, 24 randomized control trials). Pharmacovigilance data confirmed a higher frequencies of skin disorders and other ADEs compared to various comparator drugs. Compared to azithromycin, SMX‐TMP was associated with a 5‐fold increase in Stevens–Johnson syndrome, a 3‐fold increase in toxic epidermal necrolysis, and a 10‐fold increase in drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Additionally, SMX‐TMP showed a 10‐fold increase in reports of pancytopenia, a 6‐fold increase in neutropenia, a 4‐fold increase in both thrombocytopenia and aplastic anaemia, a 56‐fold increase in hyperkalaemia, and a 10‐fold increase in hyponatraemia.

Conclusion

Our meta‐analyses and pharmacovigilance study suggested SMX‐TMP was associated with increased risk of ADEs compared to other antibiotics including amoxicillin/clavulanate, azithromycin and nitrofurantoin. Further robust research is essential to confirm these safety signals and guide clinical practice.

Keywords: adverse drug event, cotrimoxazole, cutaneous drug reaction, Septra

1. INTRODUCTION

Adverse drug events (ADEs) are significant concerns in healthcare, contributing to significant morbidity and mortality, leading to patient harm, prolonged hospital stays and increased healthcare costs. 1 , 2 Sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim (SMX‐TMP), commonly referred to as cotrimoxazole, was first approved for use in Canada in 1968, followed by the USA in 1973 and is known for its efficacy in treating bacterial infections and its cost‐effectiveness compared to other antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin. 3 , 4 , 5 This combination antibiotic has broad‐spectrum activity against various bacterial pathogens, including Moraxella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. 6 Current Food and Drug Administration (FDA)‐approved indications include treatment of chronic bronchitis, traveller's diarrhoea, urinary tract infections (UTIs), Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and toxoplasmosis. 7

SMX‐TMP use has been associated with many ADEs ranging from mild to life‐threatening in severity. 8 , 9 Several studies indicated that SMX‐TMP exhibits a higher incidence of ADEs compared to fluoroquinolones when used for the treatment of similar infections. 10 Furthermore, this antibiotic combination has been linked to ADEs unrelated to its intended use, and prescribers often underestimate the risk associated with this medication. 9 The product monograph for SMX‐TMP has reported potential associations with skin disorders such as rash and severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs), including Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). 11 Additionally, SMX‐TMP has been linked with blood disorders, including thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, aplastic anaemia and pancytopenia. 12 , 13 , 14 Previous literature suggests SMX‐TMP use can deplete folic acid stores in the human body, increasing the risk for myelosuppression in patients. 4 , 15 SMX‐TMP has also been linked to metabolic disorders, including hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia. 11 , 16 , 17 Other ADEs, including liver disorders such as hepatic disorders and renal disorders have also been reported. 11 , 18 , 19

Despite >50 years of use, the evidence on SMX‐TMP safety has not been comprehensively studied and remains incompletely characterized. Data on SMX‐TMP safety primarily come from small observational studies and case reports, offering a lower level of evidence compared to randomized controlled trials and large‐scale cohort studies. Therefore, assessing the true incidence and severity of adverse effects associated with SMX‐TMP in diverse outpatient populations is challenging. While SMX‐TMP is primarily prescribed for treating bacterial infections, existing systematic reviews and meta‐analyses predominantly examine its safety and efficacy in the treatment of fungal infections (P. jirovecii) and parasitic infections (toxoplasma, Plasmodium falciparum) especially in patients with HIV/AIDS. This has resulted in a significant gap in the literature regarding the safety of SMX‐TMP when used for bacterial infections in outpatient settings.

To address this significant gap and identify critical areas for future research, we conducted a systematic review and meta‐analysis to summarize current evidence on the association between SMX‐TMP use for bacterial infections and the risk of ADEs in outpatient settings. A pharmacovigilance study using the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database was conducted to further extend and validate findings from the meta‐analyses.

2. METHODS

2.1. Protocols and registration

We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) 20 (Table S1). This review was registered with the International Prospective Systematic Reviews Registry (PROSPERO) under the number CRD42023488122.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria for study selection included: (i) studies published in the English language on adult outpatients aged 18 and older treated with SMX‐TMP or with other antibiotics with a similar indication of use (e.g., nitrofurantoin, ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid); and (ii) comparative studies, including pharmacovigilance studies, cross‐sectional studies, case–control studies, cohort studies and randomized control trials (RCTs). The following exclusion criteria were used: (i) editorials, case reports, case series, reviews, and grey literature such as institutional reports, unpublished theses and conference abstracts; (ii) studies on pregnant and lactating patients; (iii) studies including inpatients or patients taking multiple medications or patients diagnosed with HIV or AIDS; and (iv) any studies on SMX‐TMP use as a prophylactic agent or for treatment of fungal and parasitic infections.

2.3. Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search of the bibliographic databases MEDLINE (Ovid) and Embase was conducted up to 12 August 2024, for comparative studies reporting the following outcomes of interest associated with SMX‐TMP use for the treatment of bacterial infections in outpatient settings: skin disorders (e.g., rash, SJS, TEN, DRESS), metabolic and nutrition disorders (e.g., hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia), blood disorders (e.g., pancytopenia, aplastic anaemia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia), renal disorders and hepatic disorders. We have chosen to explore these ADEs outlined in the SMX‐TMP product monograph because of their potential severity, including life‐threatening consequences or the need for hospitalization. Searching 2 or more databases provides >95% coverage of the relevant references. 21 The search strategy included database‐specific keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms to ensure all relevant literature was captured. Synonyms for SMX‐TMP, such as cotrimoxazole, and commercialized brand names such as Bactrim and Septra were used in the search strategy. Further, synonymous terms used to describe outcomes of interest were also incorporated into the search strategy. Details of the search strategy used for Medline and Embase can be found in Tables S2 and S3, respectively.

2.4. Study selection

We used Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for study selection. Two screening levels were conducted to identify relevant literature: (i) title and abstract screening; and (ii) full‐text review. Two independent reviewers (R.P. and L.E.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all records identified in the systematic search to assess their eligibility for inclusion in the review. The full texts of potentially relevant studies were retrieved, and full texts were assessed independently by the same reviewers for eligibility based on pre‐established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Consensus or a third reviewer (F.T.M.) resolved disagreements at both screening levels.

2.5. Data extraction

Data were extracted from included studies and managed using Microsoft Excel. Extracted data included study characteristics (e.g., author, study design and sample size), data collection procedures and statistical analysis methods used, patient demographics and baseline characteristics (e.g., sex, age and gender), details of SMX‐TMP exposure (e.g., dosage and duration of treatment), type of adverse event reported, as well as the number of ADEs associated and any relevant measures of effect (e.g., odds ratios, relative risks or hazard ratios). When the measure of association was not reported, we calculated unadjusted risk ratios using the Mantel–Haenszel chi‐squared test.

2.6. Risk of bias assessment

Four reviewers, grouped into 2 pairs (R.P. and L.E., F.A. and A.J), independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or a fifth reviewer (F.T.M.). Version 2 of the Cochrane Risk of Bias for Randomized Trials (RoB 2) tool was used to appraise RCTs. 22 If an RCT exhibited indications for concern in the randomization process, deviations from the intended intervention, missing outcome data, inadequacy in measuring the outcome, or selective reporting, it was classified as having an overall high risk of bias. If the RCT did not provide sufficient information to make a definite judgement in these bias domains, the study was classified as having an unclear risk of bias. If a study scored a high or unclear risk of bias in 1 domain, the overall article was classified as high or unclear risk of bias, respectively. If a study was classified as low risk across all domains, the overall article had a low risk of bias. For cohort studies, the Risk of Bias in Non‐randomized Studies—of Exposures (ROBINS‐E) tool was used. 23 The modified Downs and Black checklist was used to appraise case–control and cross‐sectional studies (Downs and Black 1998). 24 These studies were assigned scores ranging from 0 to 28 and categorized into 4 quality levels: excellent (scores 26–28), good (scores 20–25), fair (scores 15–19) and poor (scores ≤14). All reviewers who completed the risk of bias assessment convened to ensure uniformity and clarify uncertainties throughout the evaluation process. Details regarding the grading of RCTs, cohort studies and other observational studies are provided in Tables S4, S5 and S6.

2.7. Data synthesis and analysis

We calculated the summary risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the random effects model (Der Simonian and Laird method) to address variability within and between studies. 25 We considered that this model was the most appropriate for calculating the summary estimate because of the diverse range of countries, populations, comparators and study periods included in our review. A meta‐analysis was completed if 3 studies or more were available for an outcome of interest. Pooled estimates were also obtained for 2 studies where the results were sufficiently similar. 26 We applied a 0.5 continuity correction to include data from a study in which 1 of the arms had zero events. This continuity correction allows for the inclusion of zero‐event trials while maintaining analytic consistency. 27 Including zero total event trials in meta‐analyses maintains analytic consistency and incorporates all available data. 27 The heterogeneity was quantified using the I 2 statistic, which indicates the percentage of variability in effect estimates attributed to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance). If the I 2 statistic exceeded 50%, we considered the heterogeneity to be high. 23 Subgroup analysis was conducted, and funnel plots were created and visually inspected with the eyeball test to assess publication bias in cases where at least 10 studies were included in a meta‐analysis.

All analyses were performed using RevMan 5.4 Review Manager software. 28 Quantitative data were combined through meta‐analysis using RevMan 5.4 Review Manager software.

2.8. Analysis of pharmacovigilance FAERS data

We used FAERS Quarterly Data Extract Files from the first quarter of 2004 to the fourth quarter of 2023 to collect reports of ADEs reported following SMX‐TMP use. The FAERS database adheres to the International Safety Reporting Guidelines established by the International Council for Harmonization (ICH). ADEs are categorized according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), an international standard medical terminology used for encoding adverse event information related to medicinal products. MedDRA preferred terms were used to identify outcomes of interest. Additionally, both the generic and brand name were used to study drugs of interest. Duplicate cases were identified and removed based on the unique Case ID associated with each report. Only the most recently reported case was included. Additionally, only case reports designated as primary suspects were included in the study.

Active comparators included drugs with similar indications for the treatment of the same condition or drugs commonly used as alternatives in clinical practice. The drugs selected as active comparators were nitrofurantoin, amoxicillin/clavulanate and azithromycin. We selected these antibiotics as comparator groups because they share several similar indications of use with SMX‐TMP, including treatment of uncomplicated UTIs, which is 1 of the most common indications for SMX‐TMP, particularly in women. Additionally, amoxicillin/clavulanate and azithromycin are commonly used for respiratory tract infections and skin and soft tissue infections, both of which are also treated with SMX‐TMP.

To identify safety signals, researchers have proposed using qualitative methods, which involve the case‐by‐case evaluation of individual safety reports, and quantitative methods that leverage data mining techniques with real‐world data from large spontaneous reporting database. 29 Disproportionality analysis is a data mining technique based on comparison of reporting proportions between the study drug and all drugs in the spontaneous reporting database combined to detect potential safety signal. 30 While this commonly used data mining technique has proven effective in identifying potential safety signals associated with newly marketed drugs that have limited safety data from randomized trials, it is not suitable for determining causality or accurately quantifying the risk of ADEs. This is due to the inherent limitations of spontaneous reporting systems, such as the presence of confounding factors and incomplete capture of critical variables needed to address these confounders, and the common issue of underreporting. 31 Therefore, to reduce concern about confounding by the indication, we used an active‐comparator restricted disproportionality analysis. 32 This method restricts the reference group to reports that include a clinically relevant active comparator, thereby improving the performance of disproportionality analysis when using spontaneous reporting databases to identify safety signals. By employing this approach, we also seek to reduce the incidence of false positive signals resulting from disproportionate reporting. 33 It is important to note that the active comparator disproportionality analysis closely resembles the active new user design, which is widely recognized as the gold standard for cohort studies evaluating post‐marketing drug safety. 34

SAS (Version 8.3, SAS Studio, Cary, NC, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses. A logistic regression was used to calculate the reporting odds ratio (ROR) and 95% CI for SMX‐TMP reports in comparison to the azithromycin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and nitrofurantoin reports.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study selection

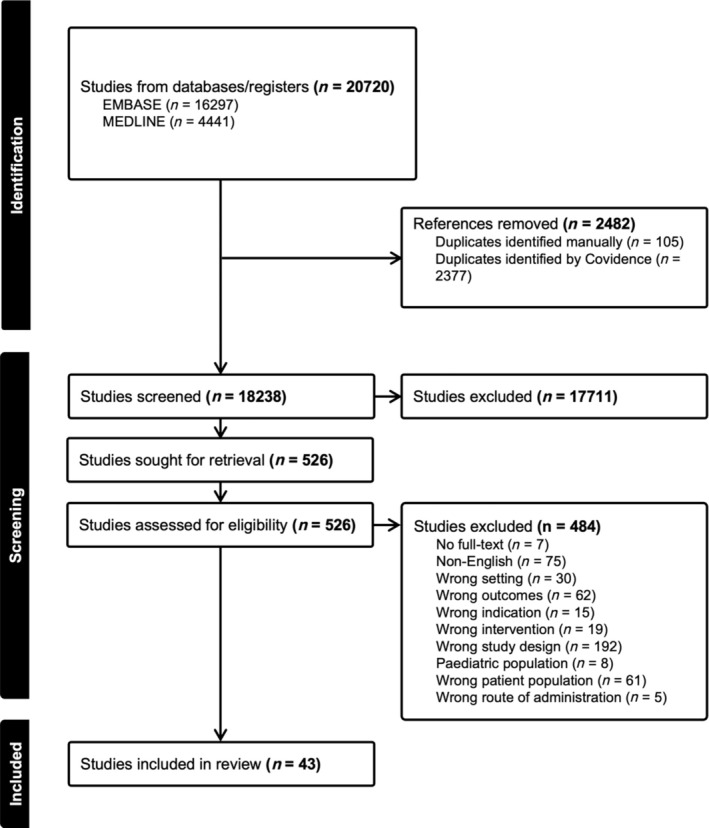

In total, 20 720 studies were retrieved from the databases EMBASE and MEDLINE (Figure 1). There were 2377 duplicates removed, leaving 18 238 studies to undergo title and abstract screening. Following this level of screening, 526 studies were sought for full‐text retrieval. A total of 484 studies were excluded during the full‐text review, with the most common reasons for exclusion being wrong study design (n = 193), non‐English language (n = 75) and wrong outcomes (n = 62; Figure 1). After completing full‐text screening, 43 studies were included in the review.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection from the databases MEDLINE and EMBASE. (Indexed from 1946 to 12 August 2024).

3.2. Included studies

Of the 43 studies included in the review, 33 studies (77%) reported on skin disorders, 9 (21%) reported on blood disorders, 3 (7%) reported on metabolic and nutritional disorders, 3 (7%) reported on immune system disorders and 4 studies (9%) reported on other ADEs including renal disorders, hepatic disorders and musculoskeletal disorders. Of the 43 studies included in the review, 33 (77%) were RCTs, 3 (7%) were cohort studies, 3 (7%) were case–control studies, 3 (7%) were cross‐sectional studies and 1 (2%) was a case‐crossover study. All 33 RCTs were published prior to 2000, with study populations ranging from 36 to 938 subjects. The median age of individuals included in this review was 36.7 years, with 93.8% of them being female.

3.3. Skin disorders

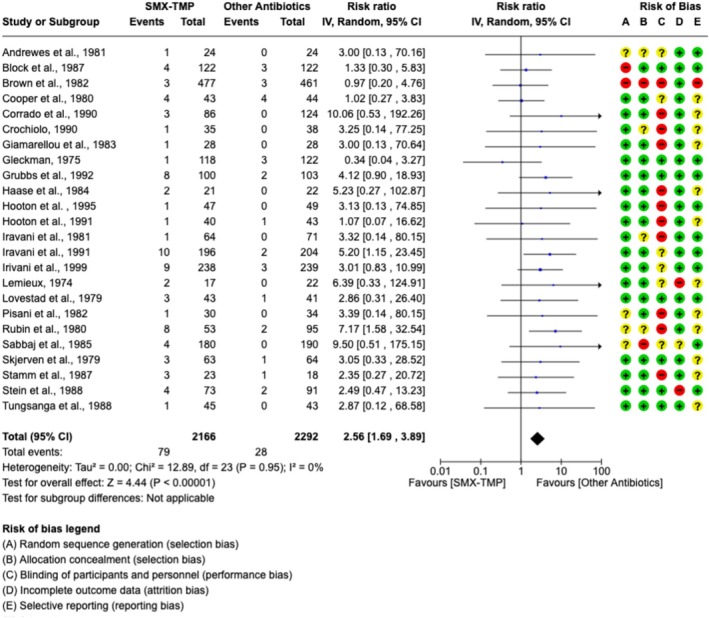

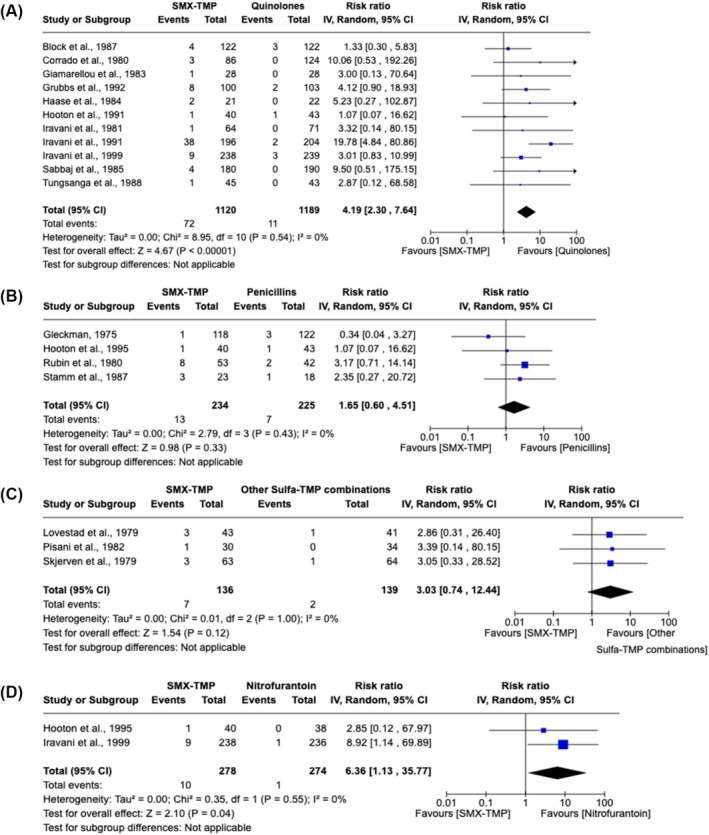

Skin disorders were reported in 33 studies (24 RCTs and 9 observational studies), comprising a total of 1 551 121 participants. These studies included patients who either received SMX‐TMP or an antibiotic with the same indication. Pre‐existing sulfa allergy was not specifically assessed or reported in individuals who presented with rash. Compared to other antibiotics, SMX‐TMP was associated with a greater risk of rash (pooled risk ratio [RR] 2.56, 95% CI [1.69–3.89], I 2 = 0, n = 4458 participants, 24 RCTs; Figure 2). There was no suggestion of publication bias in this meta‐analysis (Figure S1). Characteristics of the studies included in the meta‐analysis are shown in Table 1. In subgroup analyses, SMX‐TMP was also associated with a higher risk of rash when compared to quinolone (pooled RR 4.19, 95% CI [2.30–7.64], I 2 = 0%, n = 2309 participants, 11 RCTs; Figure 3A) or to nitrofurantoin (pooled RR 6.36, 95% CI [1.13–35.77], I 2 = 0%, n = 552 participants, 2 RCTs; Figure 3D). A higher risk of rash was also observed when penicillin or other sulfonamide‐TMP combinations were used as the comparator group, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3B,C).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot, pooled measure of risk of rash and risk of bias assessment in 24 randomized control trials comparing SMX‐TMP to antibiotics with a similar indication. Meta‐analysis included adult outpatients with an indication of urinary tract infection (UTI) treated with SMX‐TMP (n = 2166) or a different antibiotic (n = 2292). Inverse variance was used to determine risk ratio (RR) and a random‐effects model was used to assess pooled treatment effects across studies included in each analysis. Red (−) icons indicate high risk of bias, yellow (?) icons indicate unclear risk of bias and green (+) icons indicate low risk of bias.

TABLE 1.

Summary of 24 randomized control trials included in meta‐analysis of risk of rash associated with sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim (SMX‐TMP) use in comparison to other antibiotics.

| Citation | Sample size and indication | Intervention/exposure group | Comparator group | Cases of rash | Effect estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrewes et al. 1981 35 |

n = 48 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 7 days | TMP tablet (300 mg) qd, 7 days | SMX‐TMP: 1/24TMP: 0/24 | N/A |

| Block et al. 1987 36 |

n = 244 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 3 days | Ofloxacin (100 mg), BID, 3 days | SMX‐TMP: 4/122Ofloxacin: 3/122 | Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*:1.75 [0.43, 7.2] |

| Brown et al. 1982 37 |

n = 938 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 7 days | Tetracycline (1.5 g, followed by 500 mg, QID, 4 days) |

SMX‐TMP: 3/477 Tetracycline: 3/461 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: 0.97 [0.20, 4.8] |

| Cooper et al. 1980 38 |

n = 87 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (2 ablets), BID, 7 days | Cephradine (500 mg), qd, 7 days |

SMX‐TMP: 4/43 Cephradine: 4/44 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: 1.02 [0.27, 3.8] |

| Corrado et al. 1990 39 |

n = 210 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP | Norfloxacin |

SMX‐TMP: 3/86 Norfloxacin: 0/124 |

N/A |

| Crochiolo 1990 40 |

n = 73 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800 mg/160 mg), qd, 3 days | Fosfomycin trometamol (3 g), single dose |

SMX‐TMP: 1/35 Fosfomycin: 0/38 |

N/A |

| Giamarellou et al. 1983 41 |

n = 56 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (400 ug/50 ug), BID, 10 days | Norfloxacin tablet (200 mg), BID, 10 days |

SMX‐TMP: 1/28 Norfloxacin: 0/28 |

N/A |

| Gleckman 1975 42 |

n = 240 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (1.6 g/320 mg), divided doses, 10 days | Ampicillin (2 g), divided doses, 10 days |

SMX‐TMP: 1/118 Ampicillin: 3/122 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: Rash: 0.34 [0.04, 3.3] |

| Grubbs et al. 1992 43 |

n = 203 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 10 days | Ciprofloxacin (250 mg), BID, 10 days (n = 103) |

SMX‐TMP:8/100 Ciprofloxacin: 2/103 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: 4.12 [0.90, 18.9] |

| Haase et al. 1984 44 |

n = 43 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 10 days | Norfloxacin (400 mg), BID, 10 days |

SMX‐TMP: 2/21 Norfloxacin: 0/22 |

N/A |

| Hooton et al. 1991 45 | n = 144Indication: UTI | SMX‐TMP (800 mg/160 mg), BID, 7 days |

1‐Ofloxacin (400 mg), single dose (n = 48) 2‐Ofloxacin (200 mg), qd, 3 days |

SMX‐TMP: 1/47 1‐Ofloxacin: 0/48 2‐Ofloxacin: 0/49 |

N/A |

| Hooton et al. 1995 46 |

n = 158 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID,3 days |

1‐Nitrofurantoin (100 mg), QID, 3 days 2‐Cefadroxil (500 mg), BID, 3 days 3‐Amoxicillin (500 mg), TID, 3 days |

SMX‐TMP: 1/40 Nitrofurantoin: 0/38 Cefadroxil: 0/37 Amoxicillin: 1/43 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)* (reference: amoxicillin): 1.08 [0.070, 16.6] |

| Iravani et al. 1981 47 |

n = 135 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 10 days | Nalidixic Acid (1.0 g) QID, 7 days |

SMX‐TMP: 1/64 Nalidixic Acid: 0/71 |

N/A |

| Iravani et al. 1991 48 |

n = 400 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 10 days | Temafloxacin HCl (400 mg), qd, 7 days | SMX‐TMP: 10/196Temafloxacin: 2/204 | Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: 5.20 [1.2, 23] |

| Iravani et al. 1999 49 |

n = 713 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 7 days |

1‐Nitrofurantoin (100 mg), BID, 7 days (n = 236) 2‐Ciprofloxacin (100 mg), BID, 3 days (n = 239) |

SMX‐TMP: 9/238 Nitrofurantoin: 1/236 Ciprofloxacin: 3/239 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: Nitrofurantoin: 8.9 [1.1, 70] Ciprofloxacin: 3.01[0.83, 11] |

| Lemieux 1974 50 |

n = 39 Indication: UTI |

1‐SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 4 weeks | 2‐SMX (1 g), BID, 4 weeks |

1‐SMX‐TMP: 2/17 2‐SMX: 0/22 |

N/A |

| Lovestad et al. 1979 51 |

n = 105 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (600 mg/320 mg/day), 14 days |

1‐Cotrimazine (180 mg TMP/day + 820 mg sulphadiazine/day), 14 days 2‐Sulphalene (200 mg BID (day 1), 100 mg daily, 14 days |

SMX‐TMP: 3/43 Cotrimazine: 1/41 Sulphalene: 0/21 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: 2.86 [0.31–26.4] |

| Pisani et al. 1982 52 | n = 64Indication: UTI | SMX‐TMP (4 × 80 mg TMP + 400 mg SMX), QD, 10 days | Kelfiprim (TMP 350 mg + SMP 200 mg), initial double dose, followed by single dose, 10 days |

SMX‐TMP: 1/30 Kelfiprim: 0/34 |

N/A |

| Rubin et al. 1980 53 |

n = 134 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 10 days |

1‐Amoxicllin trihydrate (3 g), once 2‐Ampicillin sodium (500 mg), QID, 10 days |

SMX‐TMP: 8/53 Amoxicillin tri: 0/53 Ampicillin Na: 2/42 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: 3.17 [0.71,14.1] |

| Sabbaj et al. 1985 54 | n = 370 Indication: UTI | SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID | Norfloxacin (400 mg), BID |

SMX‐TMP: 4/180 Norfloxacin: 0/190 |

N/A |

| Skjerven et al. 1979 55 |

n = 127 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 14 days | Sulphadiazine–trimethoprim (410/90 mg), BID, 14 days |

SMX‐TMP: 3/63 SD‐TMP: 1/64 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: 3.05 [0.33, 28.5] |

| Stamm et al. 1987 56 |

n = 65 Indication: UTI |

1‐SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 14 days 2‐SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 6 weeks |

1‐Ampicillin (500 mg), QID, 14 days 2‐Ampicillin (500 mg), QID, 6 weeks |

1‐SMX‐TMP: 3/23 2‐SMX‐TMP: 1/13 1‐Ampicillin: 1/18 2‐Ampicillin: 0/11 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: 1‐SMX‐TMP + 1‐Ampicillin: 2.35 [0.27, 20.7] |

| Stein et al. 1988 57 |

n = 164 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg) BID, 10 days | RIF‐TMP 300/100 mg AM and 600/200 mg PM |

RIF‐TMP: 2/91 SMX‐TMP: 4/73 |

Crude risk ratio (95%CI)*: 2.49 [0.47, 13.2] 6 weeks SMX‐TMP differed from both treatment groups (P = 0.05) |

| Tungsanga et al. 1988 58 |

n = 88 Indication: UTI |

SMX‐TMP (800/160 mg), BID, 7 days | Norfloxacin (400 mg), BID, 7 days |

SMX‐TMP: 1/45 Norfloxacin: 0/43 |

N/A |

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; qd, once daily; QID, 4 times daily; RIF‐TMP, rifampicin–trimethoprim; SD‐TMP, sulfadiazine–trimethoprim; SMX‐TMP, sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim; UTI, urinary tract infection.

The reported effect estimate was calculated by the current reviewers.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plots and pooled risk ratios for rash according to comparator group antibiotic class. For all analyses, inverse variance was used to determine risk ratio (RR) and a random‐effects model was used to assess pooled treatment effects across studies. (A) Meta‐analysis included adult outpatients with an indication of urinary tract infection (UTI) treated with sulfamethoxazole (SMX)–trimethoprim (TMP; n = 1120) or an antibiotic from the quinolone family (i.e. ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, norfloxacin, temafloxacin, ornalidixic acid; n = 1189). (B) Meta‐analysis includes adult outpatients with an indication of UTI treated with SMX‐TMP (n = 234) or an antibiotic from the penicillin family (i.e. ampicillin or amoxicillin; n = 225). (C) Meta‐analysis includes adult outpatients with an indication of UTI treated with SMX‐TMP (n = 136) or a different sulfa–trimethoprim combination (i.e. sulfamethopyrazine‐TMP or sulfadiazine‐TMP; n = 139). (D) Meta‐analysis includes adult outpatients with an indication of UTI treated with SMX‐TMP (n = 278) or an antibiotic from the nitrofuran family (i.e. nitrofurantoin) (n = 274).

SCARs, including SJS and TEN, were reported in 2 studies: 1 retrospective population‐based cohort study and 1 case‐crossover study. The retrospective population‐based study, conducted in 1 169 033 adult outpatient women with uncomplicated UTI using the IBM MarketScan Commercial Database from 1 July 2006 to 30 September 2015 quantified the risk of adverse events associated with antibiotic treatment for urinary tract infection. This study showed that the rate of SJS events was higher among SMX‐TMP users compared to nitrofurantoin users; however, the hazard ratio could not be estimated due to low case counts. 59 The case‐crossover study assessing the risk of SJS/TEN associated with different antibiotic classes in Japanese patients showed a higher 28‐day risk of SJS/TEN (odds ratio 18.11, 95% CI [5.62–91.36]) for SMX‐TMP. However, a similar risk was also observed for penicillins (odds ratio 19.56, 95% CI [8.66–54.00]). 60 A summary of the studies reporting SJS/TEN as an outcome can be found in Table S7.

3.4. SMX‐TMP and blood disorders

Nine studies reported blood disorders (5 RCTs and 4 observational studies), comprising a total of 21 959 participants. 37 , 39 , 48 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 Thrombocytopenia, anaemia and leucopenia were each reported in 3 studies, 37 , 39 , 48 , 61 , 64 , 65 while eosinophilia and agranulocytosis were each reported in 2 studies. 48 , 62 , 63 , 64 Compared to quinolones users, SMX‐TMP users had a higher risk of leucopenia (pooled RR 3.98, 95% CI [0.83, 18.96], I 2 = 0%, n = 530 participants, 2 RCTs; Figure S2). However, the results did not reach statistical significance. A summary of these studies can be found in Table S8.

3.5. Metabolism disorders

Three studies reported metabolism disorders. 67 , 68 , 69 Hyperkalaemia was the outcome most commonly reported in studies investigating metabolism disorders. 68 , 69 Table S9 summarizes studies reporting metabolism and nutrition disorders as an outcome following SMX‐TMP use.

3.6. Immune system disorders

Two RCTs and 1 cross‐sectional study reported immune system disorders as an outcome following SMX‐TMP use. 59 , 67 , 70 Immune‐related outcomes reported included allergy, anaphylaxis and angioedema. A summary of these studies can be found in Table S10.

3.7. Other disorders

Two studies reported renal disorders, 59 , 69 while hepatic and musculoskeletal disorders were each reported in 1 study. 71 , 72 Table S11 summarizes these studies.

3.8. Analysis of pharmacovigilance FAERS data

There was a total of 10 069 cases reporting SMX‐TMP as the primary suspect drug following duplicate removal. The baseline characteristics associated with SMX‐TMP ADEs are described in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics of SMX‐TMP associated study ADE reports from the FAERS database (January 2004 to December 2023).

| All SMX‐TMP case reports (n = 10 069) | Rash (n = 1594) | Thrombocytopenia (n = 279) | Hyperkalaemia (n = 552) | Acute kidney injury (n = 491) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median age (IQR) | 56 (36–38) | 53 (33–66) | 59.5 (40–68) | 69 (62–78) | 68 (56–75) |

| Age, n (%) | |||||

| <18 | 698 (6.9) | 109 (6.8) | 23 (8.2) | 2 (0.36) | 27 (5.5) |

| 18–<45 | 2004 (19.9) | 397 (24.9) | 54 (19.4) | 25 (4.5) | 45 (9.2) |

| 45–<65 | 2559 (25.4) | 417 (26.2) | 85 (30.5) | 149 (27.0) | 129 (26.3) |

| >65 | 2563 (25.5) | 354 (22.2) | 88 (31.5) | 345 (62.5) | 262 (53.4) |

| Unknown | 2245 (22.3) | 317 (19.9) | 29 (10.4) | 31(5.62) | 28 (5.7) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 4549 (45.2) | 743 (46.6) | 169 (60.6) | 417 (75.5) | 331 (67.4) |

| Female | 4580 (45.5) | 734 (46.1) | 95 (34.1) | 122 (22.1) | 134 (27.3) |

| Unknown | 940 (9.3) | 117 (7.3) | 15 (5.4) | 13 (2.4) | 26 (5.3) |

| Weight (kg) | |||||

| Median weight (IQR) | 77 (63–92) | 78 (64–93) | 76 (66–89) | 84 (72–98) | 84 (73–100) |

| <43 | 169 (1.7) | 42 (2.6) | 4 (1.4) | 5 (0.91) | 1 (0.20) |

| 43–<76 | 1515 (15.1) | 326 (20.5) | 49 (17.6) | 87 (15.8) | 70 (14.3) |

| 76–<92 | 895 (8.9) | 223 (14.0) | 29 (10.4) | 89 (16.1) | 60 (12.2) |

| >92 | 876 (8.7) | 208 (13.1) | 22 (7.9) | 104 (18.8) | 83 (16.9) |

| Unknown | 6614 (65.7) | 795 (50.0) | 175 (62.7) | 267 (48.4) | 277 (56.4) |

| Indication of use | |||||

| Urinary tract infection | 1450 (14.4) | 281 (17.6) | 36 (12.9) | 96 (17.4) | 73 (14.9) |

| Respiratory tract infection | 274 (2.7) | 81 (5.1) | 8 (2.9) | 15 (2.7) | 7 (1.4) |

| Skin infection | 530 (5.6) | 124 (7.8) | 21 (7.5) | 48 (8.7) | 50 (10.2) |

| Serious outcomes | |||||

| Death | 297 (3.0) | 16 (1.0) | 11 (3.9) | 5 (0.91) | 9 (1.8) |

| Hospitalization | 2477 (24.6) | 521 (32.7) | 105 (37.6) | 298 (54.0) | 216 (44.0) |

| Life threatening | 608 (6.0) | 89 (5.6) | 33 (11.8) | 61 (11.1) | 23 (4.7) |

| Disability | 108 (1.1) | 22 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.54) | 1 (0.20) |

| Time to reaction onset | |||||

| Median time to reaction onset (IQR), days | 7 (3–10) | 7 (3–72) | 10 (6–79) | 10 (6–77) | 10 (6–79) |

| <3 | 758 (7.5) | 184 (11.5) | 6 (2.15) | 22 (4.0) | 17 (3.5) |

| 3‐ < 7 | 727 (7.2) | 172 (10.8) | 23 (8.2) | 65 (11.8) | 49 (10.0) |

| 7‐ < 14 | 755 (7.5) | 221 (13.06) | 38 (13.6) | 102 (18.5) | 58 (11.8) |

| 14‐ < 30 | 141 (1.4) | 32 (2.0) | 7 (2.5) | 23 (4.2) | 10 (2.0) |

| ≥30 | 887 (8.8) | 211 (13.2) | 32 (11.5) | 101 (18.3) | 70 (14.3) |

| Unknown | 6801 (67.5) | 774 (48.6) | 173 (62.0) | 239 (43.3) | 287 (58.5) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

3.8.1. Skin disorders

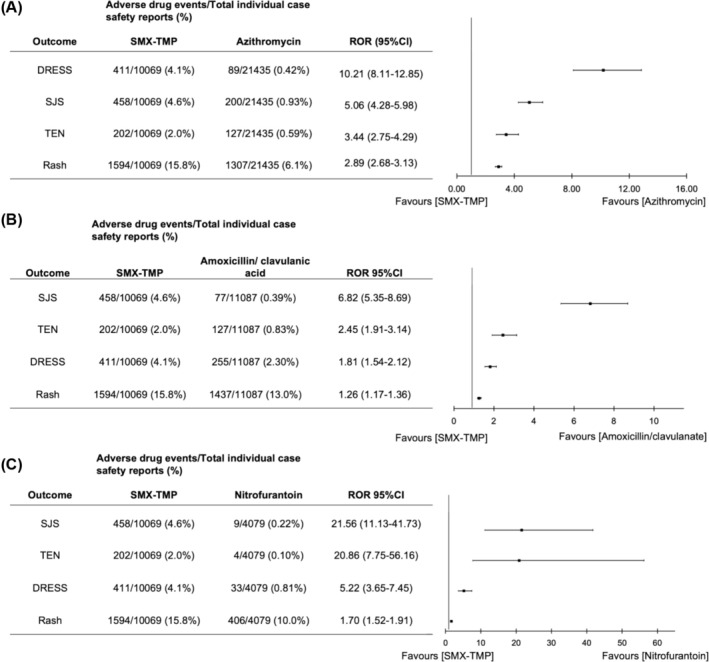

Skin disorders investigated included rash, SJS, TEN and DRESS. Compared to azithromycin, SMX‐TMP showed a 2.9‐fold increase in rash reports (1594 of 10 069 [15.8%] vs. 1307 of 21 435 [6.1%]; ROR, 2.89 [95%CI 2.68–3.13]), a 5‐fold increase in SJS reports (458 of 10 069 [4.6%] vs. 200 of 21 435 [0.93%]; ROR, 5.06 [95% CI 4.28–5.98]), a 3‐fold increase in TEN reports (202 of 10 069 [2.0%] vs. 127 of 21 435 [0.59%]; ROR, 3.44 [95%CI 2.75–4.29] and a 10‐fold increase in DRESS reports (411 cases of 10 069 [4.08%] vs. 89 cases of 21 435 [0.42%]; ROR, 10.21 [95% CI, 8.11–12.85]; Figure 4A). Similarly, signals were detected for each of these outcomes when a comparator group of amoxicillin/clavulanate (Figure 4B) or nitrofurantoin (Figure 4C) was used. In comparison to amoxicillin/clavulanate, SMX‐TMP exhibited a nearly 7‐fold increase in SJS reports (458 of 10 069 [4.6%] vs. 77 of 11 087 [0.39%]; ROR, 6.82 [95%CI 5.35–8.69]) and 2‐fold increase in TEN reports (202 of 10 069 [2.0%] vs. 127 of 11 087 [0.83%]; ROR, 2.45 [95%CI 1.91–3.14]; Figure 4B). When nitrofurantoin was used as the comparator group, SMX‐TMP showed a nearly 21‐fold increase in SJS reports (458 of 10 069 [4.6%] vs. 9 of 4079 [0.22%]; ROR, 21.56 [95%CI 11.13–41.73]) and a 21‐fold increase in TEN reports (202 of 10 069 [2.0%] vs. 4 of 4079 [0.10%]; ROR, 20.86 [95%CI 7.75–56.16]; Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Reporting odds ratio (ROR) and confidence interval (95%CI) for the skin disorders rash, Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) using 3 different comparator drugs. Comparator drugs included (A) azithromycin, (B) amoxicillin/clavulanate and (C) nitrofurantoin. ROR > 1 and lower confidence limit >1 indicates signal detection.

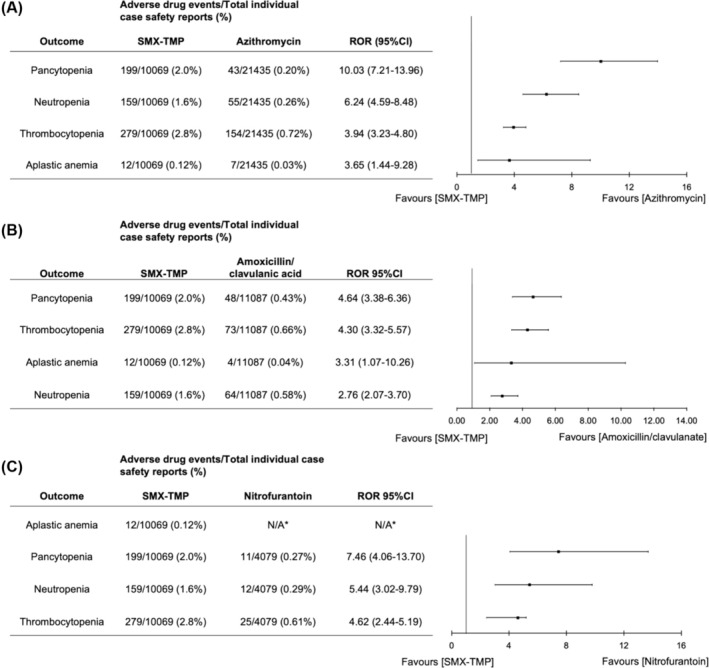

3.8.2. Blood disorders

The blood disorders examined in this active‐comparator disproportionality analysis included aplastic anaemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia and pancytopenia. Compared to azithromycin, SMX‐TMP exhibited a 10‐fold increase in the reports of pancytopenia (199 of 10 069 [2.0%] vs. 43 of 21 435 [0.20%]; ROR, 10.03 [95% CI 7.21–13.96]; Figure 5A). This was a higher increase than the ROR observed with amoxicillin/clavulanate (Figure 5B) or nitrofurantoin (Figure 5C) as comparator groups. Similarly, SMX‐TMP showed a higher ROR for neutropenia compared to azithromycin (159 of 10 069 [1.6%] vs. 55 of 21 435 [0.26%]; ROR, 6.24 [95% CI 4.59–8.48]), amoxicillin/clavulanate (159 of 10 069 [1.6%] vs. 64 of 21 435 [0.30%]; ROR, 2.76 [95% CI 2.07–3.70]) and nitrofurantoin (159 of 10 069 [1.6%] vs. 12 of 4079 [0.29%]; ROR, 5.44 [95% CI 3.02–9.79]; Figure 5). The ROR for thrombocytopenia and aplastic anaemia was similar across the comparator groups. However, the ROR for aplastic anaemia was not calculated for the nitrofurantoin group due to fewer than 3 reported cases (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Reporting odds ratio (ROR) and confidence interval (95%CI) for the blood disorders aplastic anaemia, pancytopenia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia using 3 different comparator drugs. Comparator drugs included (A) azithromycin, (B) amoxicillin/clavulanate and (C) nitrofurantoin. ROR > 1 and lower confidence limit >1 indicates signal detection.*indicates number of cases < 3, so ROR was not calculated.

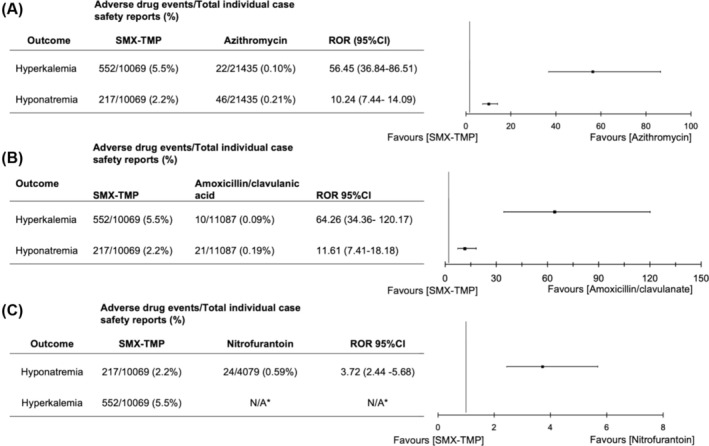

3.8.3. Metabolism disorders

SMX‐TMP exhibited a 56‐fold (552 of 10 069 [5.5%] vs. 22 of 21 435 [0.10%]; ROR, 56.45 [95%CI 36.84–86.51]) and 64‐fold (552 of 10 069 [5.5%] vs. 10 of 11 087 [0.19%]; ROR, 64.26 [95%CI 34.36–120.17]) increase in hyperkalaemia reports in comparison to azithromycin and amoxicillin/clavulanate, respectively (Figure 6). There was also an increased risk of hyponatraemia following SMX‐TMP use in comparison to all 3 comparator groups.

FIGURE 6.

Reporting odds ratio (ROR) and confidence interval (95%CI) for the metabolic disorders hyperkalaemia and hyponatraemia using 3 different comparator drugs. Comparator drugs included (A) azithromycin, (B) amoxicillin/clavulanate and (C) nitrofurantoin. ROR > 1 and lower confidence limit >1 indicates signal detection. * Indicates fewer than 3 cases, ROR not calculated.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study used both a systematic review/meta‐analysis and an active comparator disproportionality analysis of the FAERS database to examine the safety profile of SMX‐TMP. Forty‐three studies were included in the review, covering a wide range of ADEs, including skin disorders, blood disorders, immune system disorders, hepatic disorders, renal disorders and musculoskeletal disorders reported in comparative studies.

Skin disorders, particularly rash, were the most commonly reported ADEs following SMX‐TMP use across the included studies. Compared to other antibiotics, SMX‐TMP was associated with a 2.6‐fold increased risk of rash. Results were consistent across subgroup analyses when antibiotic classes served as comparator groups. Findings from this meta‐analysis of RCTs were consistent across other study designs. Two observational studies reporting SCARs showed that the risk of SJS/TEN was higher among SMX‐TMP users compared to other antibiotic users. 59 , 60 However, these results should be interpreted with caution. Although the risk of SJS was higher for SMX‐TMP users in the first study, the hazard ratio could not be quantified due to low case counts, and the results were not adjusted for potential confounders. 59 In the second study, the SJS/TEN risk magnitude was higher for SMX‐TMP users. A similar increase was also observed for penicillin users, which might suggest a confounding indication. However, it is also possible that penicillin users are at a higher risk of developing SJS/TEN. Although only 2 studies included in the review reported on SJS/TEN following SMX‐TMP treatment, our active comparator‐restricted disproportionality analysis showed a 5‐fold increase in the risk of SJS, a 3‐fold increase for TEN and a 10‐fold increase for DRESS with SMX‐TMP compared to azithromycin. Similar results were observed when using amoxicillin/clavulanate and nitrofurantoin as comparator groups. These results align with a previously conducted disproportionality analysis of the Vietnamese spontaneous reporting database, reporting an adjusted ROR of 3.1 (95%CI 1.16–6.9) for SMX‐TMP compared to reports of other medications. 73

Immunoglobulin E (IgE)‐mediated hypersensitivity cutaneous reactions are hypothesized to be mediated by the 5‐methyl group or the N1‐substitute group in SMX‐TMP, which are both important for IgE antibody recognition. 74 , 75 Predisposition to SMX‐TMP induced rash has been linked to pharmacogenetic factors, including N‐acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2) slow acetylator phenotypes. Previous studies have demonstrated that NAT2 slow acetylators are at increased risk for SCARs including SJS and TEN. 76 , 77 It has been suggested that the structural features of SMX‐TMP metabolites, such as SMX‐nitro, contribute to non‐IgE‐mediated reactions. 75 , 78 In slow acetylators, the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 2C9 facilitates the formation of these reactive compounds, which can bind to T cells and induce hypersensitivity reactions. Different ethnic groups exhibit different prevalences of the NAT2 slow acetylator phenotype, with rates of approximately 5–25% in East Asians, 40–60% in Caucasians and 90% in Arab populations. 79

In our study, the median time to rash onset was 7 days, with most AEs occurring within 30 days. This is consistent with findings from a recent population‐based study examining severe cutaneous drug reactions associated with oral antibiotics, including TMP‐SMX. 80 However, this onset time is longer than typically expected for an IgE‐mediated allergic reaction, which often occurs within minutes to hours after allergen exposure. Our results suggest that T‐cell‐mediated delayed hypersensitivity mechanisms may be the primary drivers of TMP‐SMX‐induced cutaneous reactions rather than immediate‐type hypersensitivity. As outlined above, some mechanistic studies may support this hypothesis, suggesting that pharmacogenetic factors such as NAT2 slow acetylator phenotypes contribute to SCARs such as SJS and TEN. Additionally, reactive SMX metabolites in individuals with reduced acetylation capacity may play a role in non‐IgE‐mediated hypersensitivity reactions hypersensitivity reactions. However, further mechanistic studies are required to confirm this hypothesis.

Clinicians should remain vigilant for any signs of skin adverse reactions in patients who have been prescribed SMX‐TMP. It is essential to consider alternative antibiotics for patients with a history of skin reactions to SMX‐TMP or those who are at a higher risk of developing skin conditions.

Blood disorders were the second most reported ADEs following SMX‐TMP use in the included studies. Compared to quinolone users, SMX‐TMP users had an almost 4‐fold higher risk of leucopenia, but the results did not reach statistical significance due to a lack of power. Our pharmacovigilance study showed a 10‐fold increase in reports of pancytopenia, a 6‐fold increase in neutropenia and a 4‐fold increase in both thrombocytopenia and aplastic anaemia for SMX‐TMP compared to azithromycin. These results were consistent when nitrofurantoin and amoxicillin/clavulanate were used as comparator groups. Prolonged use of SMX‐TMP has been associated with myelosuppression, leading to thrombocytopenia, anaemia and pancytopenia. 81 This ADE may result from SMX‐TMP's inhibition of dihydrofolic acid in haematopoietic progenitor cells, leading to impaired proliferation and maturation of blood cell lineages. 81 , 82 Further investigation is required to determine the risk of blood disorders associated with SMX‐TMP use in outpatients.

Hyperkalaemia was reported most frequently in studies investigating metabolism disorders. A well‐conducted population‐based study showed that SMX‐TMP vs. amoxicillin was associated with a >3‐fold increase in the risk of hyperkalaemia. 69 Our pharmacovigilance study showed a 56‐fold increase in reports of hyperkalaemia and a 10‐fold increase in reports of hyponatraemia for SMX‐TMP compared to azithromycin. Standard doses of SMX‐TMP are linked to metabolic disorders such as hyperkalaemia and hyponatraemia in patients with pre‐existing renal function deficiencies. 83 , 84 SMX‐TMP may cause hyperkalaemia primarily through TMP's interference with epithelial sodium channels in the distal nephron, leading to increased potassium retention and decreased sodium reabsorption. 85 Healthcare providers should be aware of the possible association of SMX‐TMP with hyperkalaemia, especially in elderly patients who are potentially at high risk of this ADE. While our study results indicate that SMX‐TMP is associated with an increased risk of several adverse effects, including severe cutaneous reactions such as SJS, pancytopenia and hyperkalaemia, we acknowledge that TMP‐SMX is often the treatment of choice for serious infections, such as Pneumocystis pneumonia, particularly in HIV patients. In these cases, the benefits of using TMP‐SMX, which is highly effective for treating these infections, may outweigh the risks of rare and potentially severe ADEs. The risk of ADEs must always be balanced against the much higher risk of morbidity or mortality associated with ineffective treatment in such critical conditions. Physicians should carefully monitor and consider patient‐specific factors when prescribing TMP‐SMX, especially for patients with underlying comorbidities or in settings where alternative treatments may not be as effective. Additionally, our findings should be confirmed in future pharmacoepidemiological studies to validate these safety signals and better guide clinical practice.

The results of our study are consistent with previous findings and provide further insight into ADEs associated with SMX‐TMP use in outpatient treatment of bacterial infections. 86 This systematic review had several limitations. First, most RCTs included in the review (71%; 24/34) were subject to a high or unclear risk of bias. The 2 studies included in the meta‐analysis for leucopenia were scored as high and unclear risk of bias, respectively, leading to low evidence. Second, most studies included in the review (84%; 36/43) were published before 2000. The temporal limitation may affect the findings' applicability to current clinical practices, as both antibiotic safety profiles and ADE management practices have evolved over time. However, results for the pharmacovigilance study, which include a contemporary period of time (2004–2023), were consistent with the results observed in this review. Third, 93.8% of individuals included in the meta‐analysis were female. This is mainly because the studies focused on UTIs, which predominantly affect women. This sex imbalance may limit the generalizability of our findings to males or individuals using SMX‐TMP for other indications. However, results from the pharmacovigilance study showed consistent reporting odds ratios for rash in both males and females, suggesting that the risk of skin reactions associated with SMX‐TMP may not be limited to women. Fourth, studies reviewed came from diverse geographic locations, which could result in variability in the reported ADEs due to differences in patient populations, healthcare systems and antibiotic prescribing practices. Due to this variability, our findings may not be generalizable to specific regions or populations. Sixty percent of reports from the FAERS database that were included in our active comparator disproportionality analysis came from the USA, which can limit the generalizability of the results. Fifth, fewer studies were included in the review for many ADEs, such as immune system disorders and metabolic disorders, which precluded further meta‐analyses of these outcomes. However, data from our pharmacovigilance study showed potential signals for these outcomes that require further research with a more robust study design. Although the pharmacovigilance study extended and supplemented the findings of the review, it remains limited by the spontaneous reporting nature of the database. The FAERS database is subject to underreporting because it relies on a voluntary reporting system, and healthcare professionals and consumers do not always report ADEs. Further, the reports on the database often lack detailed patient information and information on crucial confounding variables such as medical history. The FAERS database is also subject to confounding by indication and notoriety bias. 32 , 87 Disproportionality analyses, such as the current study that calculate effects such as ROR, are not indications of the strength of an association between a drug and ADE. This study was intended to generate hypotheses for future studies to investigate ADE association with SMX‐TMP use. Sixth, while including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) could increase the coverage of our studies, we conducted a comprehensive search using MEDLINE (Ovid) and Embase (Ovid), both of which are well‐regarded for their extensive coverage of medical and pharmacological literature. Searching 2 or more databases provides >95% coverage of relevant references. 21 Additionally, we manually reviewed the reference lists of included studies to ensure completeness. We are confident that our literature search was comprehensive and minimized the risk of missing studies.

Seventh, while we did not include the Baktar brand name for SMX‐TMP used in some regions, we are confident that our search strategy captured all relevant studies. We included both the generic terms “sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim” and “cotrimoxazole,” as well as widely recognized commercial brand names such as “Bactrim” and “Septra.” This approach ensured that studies using various brand names were incorporated. Baktar is not commonly used or reported in the literature and would probably be captured under the generic terms “sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim” and “cotrimoxazole.” Therefore, its omission is unlikely to compromise the thoroughness of our search. Eighth, we acknowledged that SMX‐TMP dosing can vary widely depending on the indication. Unfortunately, dosing information was not consistently available in the studies included in our analysis, preventing us from performing subgroup analyses based on specific dosing regimens. Future research with more detailed dosing data would be valuable in understanding how dosing impacts the risk of AEs. Ninth, pre‐existing sulfa allergies were not assessed or reported in individuals who developed a rash. This is a potential limitation, as a known sulfa allergy could increase the likelihood of rash development. Future studies that account for this risk factor could provide clearer insights into the relationship between sulfa allergies and the risk of skin reactions associated with SMX‐TMP.

Our findings highlight the need for additional high‐quality studies to further explore the safety of SMX‐TMP. Future research should address the limitations identified in our review and in our pharmacovigilance study by conducting contemporary, well‐designed, population‐based studies with rigorous methodologies. Clinical decision‐making needs to consider a variety of patient populations when researching ADEs.

5. CONCLUSION

Our meta‐analyses and pharmacovigilance study suggested that SMX‐TMP may be associated with an increased risk of rash and SCARs, such as SJS, TEN and DRESS, and other ADEs, such as pancytopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and hyperkalaemia compared to other commonly used antibiotics. However, potential biases in both the meta‐analysis and the pharmacovigilance study may affect the validity of these findings. Further research is needed to accurately quantify the association between SMX‐TMP and ADEs to guide clinicians in considering alternative treatments or enhanced monitoring strategies for at‐risk patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.P. and F.T.M. coordinated the study design and data acquisition. All authors contributed to analysing and interpreting the data. R.P. drafted the initial manuscript. L.E.E., F.A., A.J. and F.T.M. critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final version. The corresponding author (F.T.M.) attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors reported no conflicts of interest.

PATIENT CONSENT

This study does not include factors necessitating patient consent.

Supporting information

TABLE S1 PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

TABLE S2 Search strategy MEDLINE (Ovid).

TABLE S3 Search strategy EMBASE.

TABLE S4 Risk of bias analysis of RCTs.

TABLE S5. Risk of bias analysis of case–control and cross‐sectional studies.

TABLE S6 Risk of bias analysis of nonrandomized studies of exposure.

TABLE S7 Summary of studies reporting SJS and TEN post SMX‐TMP exposure.

TABLE S8 Summary of studies reporting blood disorders post SMX‐TMP exposure.

TABLE S9 Summary of studies reporting metabolism and nutrition disorders post SMX‐TMP exposure.

TABLE S10 Summary of studies reporting immune system disorders post SMX‐TMP exposure.

TABLE S11 Summary of studies reporting renal, hepatic and MSK disorders post SMX‐TMP exposure.

FIGURE S1 Funnel plot of 24 RCTs reporting rash following SMX‐TMP use.

FIGURE S2 Forest plot, pooled measure of risk of leucopenia and risk of bias assessment in 2 RCTs comparing SMX‐TMP to antibiotics from the quinolone family.

Preyra R, Eddin LE, Ahmadi F, Jafari A, Muanda FT. Safety of sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim for the treatment of bacterial infection in outpatient settings: A systematic review and meta‐analysis with active comparator disproportionality analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2025;91(6):1632‐1648. doi: 10.1002/bcp.70051

Funding information No funding was received for this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wu C, Bell CM, Wodchis WP. Incidence and economic burden of adverse drug reactions among elderly patients in Ontario emergency departments: a retrospective study. Drug Saf. 2012;35(9):769‐781. doi: 10.1007/BF03261973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shehab N, Lovegrove MC, Geller AI, Rose KO, Weidle NJ, Budnitz DS. US emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events, 2013–2014. Jama. 2016;316(20):2115‐2125. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smilack JD. Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74(7):730‐734. doi: 10.4065/74.7.730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ho JMW, Juurlink DN. Considerations when prescribing trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(16):1851‐1858. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kurzer E, Kaplan SA. Cost effectiveness model comparing trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin for the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis. Eur Urol. 2002;42(2):163‐166. doi: 10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00270-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Masters PA, O'Bryan TA, Zurlo J, Miller DQ, Joshi N. Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole revisited. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(4):402‐410. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kemnic TR, Coleman M. Trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513232/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lawson DH, Paice BJ. Adverse reactions to trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. Rev Infect Dis. 1982;4(2):429‐433. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.2.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coppry M, Duret S, Berdaï D, et al. Adverse drug reactions induced by cotrimoxazole: still a lot of preventable harm. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2022;36(2):421‐426. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boye NP, Gaustad P. Double‐blind comparative study of ofloxacin (hoe 280) and trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of patients with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive lung disease. Infection. 1991;19(Suppl 7):S388‐S390. doi: 10.1007/BF01715834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Teva Canada Limited . Product monograph ‐ Teva‐trimel DS tablets. Published Online 2018. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00043787.PDF

- 12. Chiravuri S, De Jesus O. Pancytopenia. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed April 4, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563146/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jinna S, Khandhar PB. Thrombocytopenia. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed April 4, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542208/ [Google Scholar]

- 14. Justiz Vaillant AA, Zito PM. Neutropenia. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed April 4, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507702/ [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parajuli P, Ibrahim AM, Siddiqui HH, Lara Garcia OE, Regmi MR. Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole induced pancytopenia: a common occurrence but a rare diagnosis. Cureus. 11(7):e5071. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rondon H, Badireddy M. Hyponatremia. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed April 4, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470386/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Simon LV, Hashmi MF, Farrell MW. Hyperkalemia. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470284/ [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abusin S, Johnson S. Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim induced liver failure: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1(1):44. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shimizu Y, Hirai T, Ogawa Y, Yamada C, Kobayashi E. Characteristics of risk factors for acute kidney injury among inpatients administered sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim: a retrospective observational study. J Pharm Health Care Sci. 2022;8(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s40780-022-00251-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ewald H, Klerings I, Wagner G, et al. Searching two or more databases decreased the risk of missing relevant studies: a metaresearch study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;149:154‐164. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539‐1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non‐randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377‐384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177‐188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ryan R, Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. ‘Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group: meta‐analysis. December 2016. Accessed June 26, 2024. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/

- 27. Friedrich JO, Adhikari NKJ, Beyene J. Inclusion of zero total event trials in meta‐analyses maintains analytic consistency and incorporates all available data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. The Cochrane Collaboration . Rev Man 5.4 Review Manager. revman.cochrane.org

- 29. Alvarez Y, Hidalgo A, Maignen F, Slattery J. Validation of statistical signal detection procedures in eudravigilance post‐authorization data: a retrospective evaluation of the potential for earlier signalling. Drug Saf. 2010;33(6):475‐487. doi: 10.2165/11534410-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bate A, Evans SJW. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(6):427‐436. doi: 10.1002/pds.1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Michel C, Scosyrev E, Petrin M, Schmouder R. Can disproportionality analysis of post‐marketing case reports be used for comparison of drug safety profiles? Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(5):415‐422. doi: 10.1007/s40261-017-0503-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alkabbani W, Gamble JM. Active‐comparator restricted disproportionality analysis for pharmacovigilance signal detection studies of chronic disease medications: an example using sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;89(2):431‐439. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grundmark B, Holmberg L, Garmo H, Zethelius B. Reducing the noise in signal detection of adverse drug reactions by standardizing the background: a pilot study on analyses of proportional reporting ratios‐by‐therapeutic area. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(5):627‐635. doi: 10.1007/s00228-014-1658-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lund JL, Richardson DB, Stürmer T. The active comparator, new user study design in pharmacoepidemiology: historical foundations and contemporary application. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2015;2(4):221‐228. doi: 10.1007/s40471-015-0053-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Andrewes DA, Chuter PJ, Dawson MJ, et al. Trimethoprim and co‐trimoxazole in the treatment of acute urinary tract infections: patient compliance and efficacy. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1981;31(226):274‐278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Block JM, Walstad RA, Bjertnaes A, et al. Ofloxacin versus trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole in acute cystitis. Drugs. 1987;34(Suppl 1):100‐106. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198700341-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brown ST, Thompson SE, Biddle JW, Kraus SJ, Zaidi AA, Kleris GS. Treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infection with trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. Sex Transm Dis. 1982;9(1):9‐14. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198201000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cooper N, Da Silva AL, Powell S. Teaching clinical reasoning. ABC Clin Reason. 2017;1:44‐50. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Corrado ML, Hesney M, Struble WE, et al. Norfloxacin versus trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of urinary tract infections. Eur Urol. 1990;17(Suppl 1):34‐39. doi: 10.1159/000464089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Crocchiolo P. Single‐dose fosfomycin trometamol versus multiple‐dose cotrimoxazole in the treatment of lower urinary tract infections in general practice. Multicenter Group of General Practitioners. Chemotherapy. 1990;36(Suppl 1):37‐40. doi: 10.1159/000238815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Giamarellou H, Tsagarakis J, Petrikkos G, Daikos GK. Norfloxacin versus cotrimoxazole in the treatment of lower urinary tract infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1983;2(3):266‐269. doi: 10.1007/BF02029530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gleckman RA. Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole vs ampicillin in chronic urinary tract infections. A double‐blind multicenter cooperative controlled study. Jama. 1975;233(5):427‐431. doi: 10.1001/jama.1975.03260050033016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grubbs NC, Schultz HJ, Henry NK, Ilstrup DM, Muller SM, Wilson WR. Ciprofloxacin versus trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole: treatment of community‐acquired urinary tract infections in a prospective, controlled, double‐blind comparison. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67(12):1163‐1168. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61146-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Haase DA, Harding GK, Thomson MJ, Kennedy JK, Urias BA, Ronald AR. Comparative trial of norfloxacin and trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of women with localized, acute, symptomatic urinary tract infections and antimicrobial effect on periurethral and fecal microflora. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;26(4):481‐484. doi: 10.1128/AAC.26.4.481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hooton TM, Johnson C, Winter C, et al. Single‐dose and three‐day regimens of ofloxacin versus trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole for acute cystitis in women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35(7):1479‐1483. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.7.1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hooton TM, Winter C, Tiu F, Stamm WE. Randomized comparative trial and cost analysis of 3‐day antimicrobial regimens for treatment of acute cystitis in women. Jama. 1995;273(1):41‐45. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520250057034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Iravani A, Richard GA, Baer H, Fennell R. Comparative efficacy and safety of nalidixic acid versus trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in treatment of acute urinary tract infections in college‐age women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;19(4):598‐604. doi: 10.1128/AAC.19.4.598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Iravani A. Comparative, double‐blind, prospective, multicenter trial of temafloxacin versus trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole in uncomplicated urinary tract infections in women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35(9):1777‐1781. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.9.1777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Iravani A, Klimberg I, Briefer C, Munera C, Kowalsky SF, Echols RM. A trial comparing low‐dose, short‐course ciprofloxacin and standard 7 day therapy with co‐trimoxazole or nitrofurantoin in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43(Suppl A):67‐75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lemieux G. Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole compared with sulfamethoxazole in urinary tract infection. Can Med Assoc J. 1974;110(8):910‐915. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lövestad A, Gästrin B, Lundström R. A clinical study of co‐trimazine in comparison with co‐trimoxazole and sulphalene in urinary tract infections. Infection. 1979;7(Suppl 4):S401‐S403. doi: 10.1007/BF01639021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pisani E, Pavone‐Macaluso M, Rocco F, et al. Kelfiprim, a new sulpha‐trimethoprim combination, versus cotrimoxazole, in the treatment of urinary tract infections: a multicentre, double‐blind trial. Urol Res. 1982;10(1):41‐44. doi: 10.1007/BF00256523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rubin RH, Fang LS, Jones SR, et al. Single‐dose amoxicillin therapy for urinary tract infection. Multicenter trial using antibody‐coated bacteria localization technique. Jama. 1980;244(6):561‐564. doi: 10.1001/jama.1980.03310060017014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sabbaj J, Hoagland VL, Shih WJ. Multiclinic comparative study of norfloxacin and trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole for treatment of urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27(3):297‐301. doi: 10.1128/AAC.27.3.297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Skjerven O, Bergan T. Double‐blind comparison of sulphonamide‐trimethoprim combinations in acute uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Infection. 1979;7(Suppl 4):S398‐S400. doi: 10.1007/BF01639020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stamm WE, McKevitt M, Counts GW. Acute renal infection in women: treatment with trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole or ampicillin for two or six weeks. A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106(3):341‐345. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-3-341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stein GE, Gurwith D, Gurwith M. Randomized clinical trial of rifampin‐trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole‐trimethoprim in the treatment of localized urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32(6):802‐806. doi: 10.1128/AAC.32.6.802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tungsanga K, Chongthaleong A, Udomsantisuk N, Petcharabutr OA, Sitprija V, Wong EC. Norfloxacin versus co‐trimoxazole for the treatment of upper urinary tract infections: a double blind trial. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1988;56:28‐34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Butler AM, Durkin MJ, Keller MR, Ma Y, Powderly WG, Olsen MA. Association of Adverse Events with antibiotic treatment for urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2022;74(8):1408‐1418. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fukasawa T, Urushihara H, Takahashi H, Okura T, Kawakami K. Risk of stevens‐Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with antibiotic use: a case‐crossover study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11(11):3463‐3472. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Asai Y, Yamamoto T, Abe Y. Evaluation of the expression profile of antibiotic‐induced thrombocytopenia using the Japanese adverse drug event report database. Int J Toxicol. 2021;40(6):542‐550. doi: 10.1177/10915818211048151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Castro M. A comparative study of cefadroxil and co‐trimoxazole in patients with lower respiratory tract infections. Drugs. 1986;32(Suppl 3):50‐56. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198600323-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Keisu M, Ekman E, Wiholm BE. Comparing risk estimates of sulphonamide‐induced agranulocytosis from the Swedish drug monitoring system and a case‐control study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;43(3):211‐214. doi: 10.1007/BF02333011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Levy M, Slone D, Shapiro S. Anti‐infective drug use in relation to the risk of agranulocytosis and aplastic anemia. A report from the international agranulocytosis and aplastic anemia study. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(5):1036‐1040. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1989.00390050040008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nelson M, Bresher JT, Duncan WC, Eakins W, Knox JM. Comparison of trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole with penicillin and tetracycline in the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea in women. Can Med Assoc J. 1975;112(13 Spec No:43‐46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. ten Berg MJ, Huisman A, Souverein PC, et al. Drug‐induced thrombocytopenia: a population study. Drug Saf. 2006;29(8):713‐721. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200629080-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Basista MP. Randomized study to evaluate efficacy and safety of ofloxacin vs. trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole in treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Urology. 1991;37(3 Suppl):21‐27. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(91)80092-l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Alappan R, Buller GK, Perazella MA. Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole therapy in outpatients: is hyperkalemia a significant problem? Am J Nephrol. 1999;19(3):389‐394. doi: 10.1159/000013483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hwang YJ, Muanda FT, McArthur E, et al. Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole and the risk of a hospital encounter with hyperkalemia: a matched population‐based cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;38(6):1459‐1468. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfac282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Watt B, Chait I, Kelsey MC, et al. Norfloxacin versus cotrimoxazole in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections‐‐a multi‐centre trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984;13(Suppl B):89‐94. doi: 10.1093/jac/13.suppl_b.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jick H, Derby LE. A large population‐based follow‐up study of trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, and cephalexin for uncommon serious drug toxicity. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 1995;15(4):428‐432. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.1995.tb04378.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Teng C, Baus C, Wilson JP, Frei CR. Rhabdomyolysis associations with antibiotics: a pharmacovigilance study of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS). Int J Med Sci. 2019;16(11):1504‐1509. doi: 10.7150/ijms.38605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Nguyen KD, Tran TN, Nguyen MLT, et al. Drug‐induced stevens‐Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in vietnamese spontaneous adverse drug reaction database: a subgroup approach to disproportionality analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(1):69‐77. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Harle DG, Baldo BA, Wells JV. Drugs as allergens: detection and combining site specificities of IgE antibodies to sulfamethoxazole. Mol Immunol. 1988;25(12):1347‐1354. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(88)90050-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Khan DA, Knowles SR, Shear NH. Sulfonamide hypersensitivity: fact and fiction. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(7):2116‐2123. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wang D, Para MF, Koletar SL, Sadee W. Human N‐acetyltransferase 1 *10 and *11 alleles increase protein expression through distinct mechanisms and associate with sulfamethoxazole‐induced hypersensitivity. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2011;21(10):652‐664. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283498ee9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sim E, Abuhammad A, Ryan A. Arylamine N‐Acetyltransferases: from Drug Metabolism and Pharmacogenetics to Drug Discovery Accessed January 27, 2025. https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.12598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78. Maker JH, Stroup CM, Huang V, James SF. Antibiotic hypersensitivity mechanisms. Pharm J Pharm Educ Pract. 2019;7(3):122. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy7030122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Desta Z, Flockhart DA. Chapter 18 ‐ Pharmacogenetics of Drug Metabolism. In: Robertson D, Williams GH, eds. Clinical and translational science. Second ed. Academic Press; 2017:327‐345. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-802101-9.00018-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lee EY, Gomes T, Drucker AM, et al. Oral antibiotics and risk of serious cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Jama. 2024;332(9):730‐737. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.11437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Libecco JA, Powell KR. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole: clinical update. Pediatr Rev. 2004;25(11):375‐380. doi: 10.1542/pir.25.11.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Elajez R, Nisar S, Adeli M. Does trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis induce myelosuppression in primary immune deficiency disease patients; a retrospective, 3 groups comparative study. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2023;41(4):353‐360. doi: 10.12932/AP-050320-0782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Witt JM, Koo JM, Danielson BD. Effect of standard‐dose trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole on the serum potassium concentration in elderly men. Ann Pharmacother. 1996;30(4):347‐350. doi: 10.1177/106002809603000404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Mori H, Kuroda Y, Imamura S, et al. Hyponatremia and/or hyperkalemia in patients treated with the standard dose of trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. Intern Med Tokyo Jpn. 2003;42(8):665‐669. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.42.665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lam N, Weir MA, Juurlink DN, et al. Hospital admissions for hyperkalemia with trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole: a cohort study using health care database codes for 393,039 older women with urinary tract infections. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(3):521‐523. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Green H, Paul M, Yaphe J, Leibovici L. Antimicrobial agents for treating uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD007182. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007182.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Yin Y, Shu Y, Zhu J, Li F, Li J. A real‐world pharmacovigilance study of FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) events for osimertinib. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):19555. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-23834-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

TABLE S1 PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

TABLE S2 Search strategy MEDLINE (Ovid).

TABLE S3 Search strategy EMBASE.

TABLE S4 Risk of bias analysis of RCTs.

TABLE S5. Risk of bias analysis of case–control and cross‐sectional studies.

TABLE S6 Risk of bias analysis of nonrandomized studies of exposure.

TABLE S7 Summary of studies reporting SJS and TEN post SMX‐TMP exposure.

TABLE S8 Summary of studies reporting blood disorders post SMX‐TMP exposure.

TABLE S9 Summary of studies reporting metabolism and nutrition disorders post SMX‐TMP exposure.

TABLE S10 Summary of studies reporting immune system disorders post SMX‐TMP exposure.

TABLE S11 Summary of studies reporting renal, hepatic and MSK disorders post SMX‐TMP exposure.

FIGURE S1 Funnel plot of 24 RCTs reporting rash following SMX‐TMP use.

FIGURE S2 Forest plot, pooled measure of risk of leucopenia and risk of bias assessment in 2 RCTs comparing SMX‐TMP to antibiotics from the quinolone family.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.