Abstract

Transposable elements (TEs) constitute a significant portion of the nuclear genome, but their influence on and ability to manage their activity during tissue regeneration remain largely unknown. Here, we revealed that LINE1, the most abundant TE, responds to cardiomyocyte injury and is overexpressed in a myocardial infarction (MI) model. We developed selectin binding peptide (SBP)-engineered extracellular vesicles (EVs) with targeted functions, which are loaded with LINE1 antisense oligonucleotide (ASO). The engineered EVs display targeted accumulation in injured hearts and protect against myocardial senescence by inhibiting the cGAS-STING‐TBK1‐IRF3 pathway and suppressing the expression of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors. Our data revealed that LINE1 retrotransposon activation is triggered by cardiomyocyte injury in the MI model. We also propose a strategy to reduce cardiomyocyte senescence post-myocardial infarction by modulating LINE1 activity.

Keywords: Transposable elements (TEs), LINE1 retrotransposon, Myocardial infarction, Selectins, Extracellular vesicles, Endothelial cell

Highlights

-

•

Although transposable element (TE) activity is intricately linked to the innate immune system, its contribution to regeneration remains unreported.

-

•

Inhibition of the LINE1 retrotransposon was identified as the novel therapeutic mechanism for myocardial infarction.

-

•

Engineered EVs exhibit selective targeting to injured hearts, enhancing myocardial protection via LINE1 antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) delivery.

-

•

Engineered EVs mitigate myocardial senescence by suppressing reactivation of the cGAS-STING‐TBK1‐IRF3 pathway and expression of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors.

-

•

This model paves the way for cardiac protection and therapeutic potential of EVs through targeted manipulation of TE activity.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), including heart failure (HF) and myocardial infarction (MI), are the leading causes of global mortality and remain a major public health concern [1]. Although its pathogenesis is complex, an important contributor is abnormal senescence, an intricate process that involves various molecular, cellular and systemic changes, including epigenetic alterations, DNA damage, and genomic instability [2,3]. Among these factors, retrotransposons, a type of repetitive DNA sequence capable of mobilizing across the genome, typically remain transcriptionally silenced but can be reactivated in the context of cellular senescence [4]. Furthermore, activated retrotransposons can result in de novo integration events within the genome, leading to genomic instability and further exacerbating the damage associated with the senescent phenotype [5,6].

Long interspersed element-1 (LINE1) is regarded as the most abundant and the only active retrotransposable element (RTE) capable of autonomous retrotransposition, comprising ∼20 % of the human and mouse genomes, and plays an important role in genome evolution and genetic diversity [5]. While typically subject to robust repression mechanisms, LINE1 can be triggered under certain conditions, such as during cellular senescence or in cancer cells. This activation could cause deleterious effects through genetic and epigenetic alterations or by activating immune pathways that recognize retrotransposon nucleic acids as exogenous DNA [5,7]. Modulation of LINE1 activity offers a promising avenue for developing therapeutic strategies against diverse pathologies, such as autoimmune diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancers [[8], [9], [10]]. In particular, targeted delivery of sequence-specific antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) directed against LINE1 transcripts has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in attenuating the cellular hallmarks of aging in patient-derived cells from progeroid syndromes [11].

Compared with adeno-associated virus (AAV)- and lipid nanoparticle (LNP-derived EVs), mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) display low immunoreactivity and toxicity, indicating good potential for cardiovascular therapy but suffering from limitations in cardiac residence [[12], [13], [14]]. Engineered EVs, with autonomous functionality and modifiability, offer a universal solution for CVDs, allowing targeted modifications without compromising basic functions [1,[14], [15], [16]]. Targeting selectin family molecules on injured endothelial cells (ECs) with engineered EVs, particularly CD62E and CD62P, presents a promising therapeutic strategy to mitigate vascular damage [13].

In this study, we investigated LINE1 retrotransposon activation in a mouse model of MI. We next developed bifunctional EVs that target the ischemic myocardium and deliver LINE1 ASOs for MI therapy. By utilizing selectin family molecules, including CD62E and CD62P, as molecular targets, we engineered EVs with a selectin binding peptide (SBP, IELLQAR) with LINE1-targeting ASO delivery. We confirmed that cardioprotective effects are achieved by inhibiting the cGAS-STING-TBK1-IRF3 pathway and the secretion of SASP factors. Overall, this work proposes a promising preclinical strategy for MI therapy by controlling LINE1 activity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

Human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hP-MSCs) were isolated from human placental tissues as previously described [17]. The hP-MSCs were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10 % (v/v) EV-free fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biological Industries), penicillin (100 U/ml, Gibco), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml, Gibco). To obtain neonatal cardiomyocytes (CMs) and cardiac fibroblasts (CFs), neonatal mice (BALB/c mice born within 1 day) were anesthetized with 1.0 % isoflurane and then euthanized via decapitation. The hearts were immediately embedded in freezing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY). The neonatal CMs and CFs were subsequently isolated via digestion with collagenase II and trypsin and subsequently purified via the differential attachment method. The CMs were cultured on 0.1 % gelatin in DMEM supplemented with 10 % (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biological Industries). All the experimental procedures described were approved by the Animal Experiments Ethical Committee of Nankai University (approval no. 20220022) and were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (eighth edition, 2011). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA) and cultured in endothelial cell growth medium-2 (EGM2; Lonza, Walkersville, MD).

2.2. Measurement of LINE1 expression

To test LINE1 expression under ischemic conditions, we examined CMs and heart ventricles. Total RNA from 5 × 105 cells or heart ventricles was harvested and extracted via TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) for RT-qPCR analysis. The cells or heart ventricles were collected, and total protein was extracted via radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for Western blot analysis.

2.3. Isolation of EVs

The EVs used in this study were isolated from the hP-MSC supernatant as previously described [13]. To obtain Gaussia luciferase (Gluc)-labeled EVs, hP-MSCs were transduced with Gluc-lactadherin fusion lentivirus, which allowed the EVs derived from hP-MSCs to be labeled with Gluc [13]. Briefly, the supernatant was collected every two or three days and differentially centrifuged at 500×g for 10 min, 2000×g for 30 min, and 10,000×g for 30 min to remove any cell debris or apoptotic bodies. After the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter, the EVs were collected by ultracentrifugation at 130,000×g for 2 h and washed with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) by a second ultracentrifugation step at 130,000×g for 2 h. All steps of centrifugation were performed at 4 °C. Finally, the precipitated EVs were resuspended in DPBS, and the total amount of protein was quantified via a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) before use.

2.4. Fabrication of endothelial-targeted EVs

To achieve injured endothelium-targeted therapy, we designed P selectin/E selectin-targeted EVs by conjugating selectin binding peptide (SBP; IELLQAR) onto hP-MSC-derived EVs. SBP was synthesized by RuiXi Biological Technology (Xi'an, China). The molecular weight of the SBP peptide was analyzed via high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS), and the peptide was further purified via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 6520 Q-TOF LC/MS). To generate amphipathic DSPE-PEG-SBP, 100 mg of 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-n-[poly(ethylene glycol)]-hydroxy succinimide (DSPE-PEG-NHS) and SBP peptide (1.1 mM) and triethylamine (3.0 mM) were completely dissolved in 3 ml of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and reacted at room temperature for 12 h. The reaction mixture was then dialyzed against deionized water via a dialysis membrane (MWCO <1000 Da) for 24 h. The chemical structure of purified DSPE-PEG-SBP was characterized via proton magnetic resonance (1H NMR, Bruker, AVANCE III) using D2O as the solvent.

The freeze-dried DSPE-PEG-SBP was dissolved in DMSO at a stock concentration of 500 μM. To generate SBP-EVs, the EVs were incubated with 5 μM DSPE-PEG-SBP at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, the uncombined DSPE-PEG-SBP was eluted with PBS three times by ultrafiltration (>100 kDa). To generate the EVs containing LINE1-ASO, 500 μg of naive EVs and 100 or 200 pmol of LINE1 antisense oligonucleotide (LINE1-ASO) were diluted in Gene Pulser Electroporation Buffer and transferred to ice-cold 0.4 cm or 0.2 cm Gene Pulser/MicroPulser Electroporation Cuvette (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Electroporation was performed via a Gene Pulser Xcell Total System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. EVs containing LINE-ASO were loaded on a 2.5 % agarose gel to assess the maximum retention of LINE1-ASO. The same procedures were performed for 5-carboxyfluorescein (5-FAM)-labeled LINE1-ASO for tracking LINE1-ASO in cells. The resulting FAM-LINE1-ASO-containing SBP-EVs were incubated with HEK293T cells for 24 h, captured via a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Lake Success, NY) and analyzed via ImageJ software.

2.5. Characterization of EVs

The morphologies of the EVs, SBP-EVs and SBP-LINE1-EVs were observed via transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Talos L120C G2, Hillsboro, OR). Specifically, 5 mg/ml EVs, SBP-EVs or SBP-LINE1-EVs were loaded in a carbon film (Zhongjingkeji Technology, Beijing, China) for 3 min at RT. The samples were negatively stained with 2 % phosphotungstic acid and dried through an infrared heat lamp. All samples were observed via transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at an acceleration voltage of 120 kV. The size distributions of the EVs, SBP-EVs and SBP-LINE1-EVs were measured via nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) (Particle Metrix, Germany). Additionally, EV samples were quantified via a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. EV markers (CD9, CD63, ALIX, and TSG101) were subsequently detected via Western blot.

2.6. EC targeting and transendothelial migration of SBP-EVs

To establish the ischemic endothelium in vitro, 4 × 104 HUVECs were passaged and seeded onto coverslips in a 24-well plate at 37 °C, 5 % CO2 and 95 % air for 24 h before ischemia induction. Then, an oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) assay was performed. In brief, HUVECs were cultured in serum-free DMEM without glucose (Solarbio) with 1 % O2, 5 % CO2 and 94 % N2 at 37 °C for 24 h. For the normoxic control, the medium was replaced with complete DMEM, and the cells were cultured at 37 °C, 5 % CO2 and 95 % air. Then, DiI membrane dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to mark the EVs. DiI-labeled EVs or SBP-EVs were added to the medium and further incubated for 4 h. After incubation, all the samples were washed three times with cold PBS and fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA). All the samples were stained with β-Tubulin (1:500; Proteintech, Wuhan, China) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:2000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus) and analyzed via ImageJ software.

To investigate the transendothelial migration of SBP-EVs in vitro, a 0.4 μm Transwell insert (NEST, Wuxi, China) was used according to previously described methods [13]. In brief, 5 × 103 HUVECs were seeded into the upper chamber of a Transwell insert and cultured in endothelial cell growth medium-2 (EGM-2; Lonza) medium for an additional 7 days. The cells were examined via an inverted microscope (Olympus) to ensure that the HUVECs were confluent before proceeding to the next step. Then, the CMs were seeded onto coverslips in the lower chambers of the inserts. After being cocultured for 24 h, an OGD experiment was performed for another 24 h. Next, CD62E- and CD62P-blocking antibodies (5 μg/ml, sc-137054, sc-8419, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were added to the upper chamber of the hypoxic system for 2 h and further washed with PBS to remove excess antibody. Then, DiI-labeled EVs or DiI-labeled SBP-EVs (100 μg/ml) were added to the upper chamber of the ischemic system and incubated for another 6 h under OGD conditions. The CMs cultured in the lower chambers were washed and fixed. All the samples were counterstained with α-Actinin (1:250; sc-17829; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and DAPI. The images were captured via a fluorescence microscope (Olympus) and analyzed via ImageJ software.

2.7. Mouse model of MI

BALB/c mice (male, 8–12 weeks old) were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of the Academy of Military Medical Science (Beijing, China). All the animal treatments and the experimental procedures of the present study were approved by the Animal Experiments Ethical Committee of Nankai University and were in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (approval no. 20220022). MI models were established as previously described [18,19]. The mice were anesthetized via inhalation of 4 % isoflurane (maintained at 2 %) supplemented with a respirator system (VentStar R415, RWD, Shenzhen, China). The left anterior descending (LAD) was permanently ligated with a 6–0 silk suture. For MI treatments, 100 μg/100 μl of EVs, SBP-EVs, or SBP-LINE1-EVs (>1010 particles) were administered via the tail vein at days 1, 7, 14 and 21 after MI, and the same volume of PBS was used as a control. At the end of the protocol, all the mice were euthanized by placing them under deep anesthesia with 100 % O2/5 % isoflurane, followed by cervical dislocation. The humane endpoints (e.g., severe distress, inability to eat or drink, significant weight loss, and behavioral abnormalities indicating suffering) were used to determine whether the animals should be sacrificed before the end of the study.

2.8. Heart targeting and biodistribution of SBP-EVs

DiR membrane dye (1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Gluc were used to label EVs. In brief, for fluorescence imaging, a single dose of 100 μg DiR-labeled EVs or SBP-EVs was injected via the tail vein at 24 h after MI. The distribution of EVs in the heart and other organs was monitored via an IVIS Lumina Imaging System (excitation, 754 nm; emission, 778 nm). To investigate heart retention in EVs, 1.5 × 104 cardiomyocytes were harvested from ventricles after a single dose of 100 μg of Gluc-EVs or Gluc-SBP-EVs was administered via the tail vein, and Gluc activity was measured at the mentioned time points via a Gluc flash assay kit (16158, Thermo Scientific, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To assess heart targeting of SBP-EVs, consecutive doses of 100 μg of DiI-labeled EVs or SBP-EVs were injected via the tail vein at days 1, 7, 14 and 21 after MI surgery. Then, 5-μm-thick frozen cardiac sections were monitored via a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM; excitation, 594 nm; FV1000, Olympus, Lake Success, NY). The average radiance of the region of interest (ROI) over the cardiac region was quantified.

2.9. Senescence-associated β-galactosidase enzymatic activity assay

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (β-gal) staining of CMs and frozen cardiac sections was performed via a β-gal staining kit (Beyotime Biotechnology) according to previous methods [20]. In brief, the samples were washed with cold PBS three times and fixed with 4 % PFA for more than 15 min at RT. All the samples were subsequently washed three times and incubated overnight with a staining solution containing 1 mg/ml X-gal at 37 °C. Finally, the samples were washed three times with PBS, observed and captured via a phase contrast microscope (Olympus).

2.10. Serum biomarkers of MI

On day 4 post-MI, serum samples were collected. The levels of creatine kinase-myocardial band isoenzyme (CK-MB) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were measured via a CK-MB detection kit and an LDH detection kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

2.11. Biocompatibility of SBP-LINE1-EVs

On day 4 post-MI, serum samples were collected. The levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr) were measured via detection kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). On day 28 post-MI, the excised liver, spleen, lung, kidney and small intestine were immediately preserved in 4 % paraformaldehyde for fixation and subsequently subjected to paraffin embedding and sectioning. H&E staining was conducted following the guidelines provided by the manufacturer. Images of the stained sections were captured with a phase contrast microscope (Olympus). For in vitro biocompatibility studies, hemocompatibility was tested.

2.12. Infarction size assessment

Hearts were collected and sliced at a thickness of 1 mm on day 4 post-MI. The sections were then incubated with a solution of 2 % 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC; Solarbio) at 37 °C for 30 min and fixed with 4 % PFA for another 2 h. The infarction size of the myocardium was quantified via ImageJ software.

2.13. Heart functional analysis with echocardiogram

Echocardiography was performed by an MS-400 ultrasound scanning transducer with a VisualSonics Vevo 2100 Imaging System (Fuji Film Visual Sonics, Inc. Toronto, Canada). Most of the animals were scanned under the heart rate of 400–600 bpm at baseline (day −3), day 7, day 14 and day 28. The short and long axes of the left ventricle were captured by M-mode echocardiography to obtain the left ventricular ejection fraction (EF, %), fractional shortening (FS, %), left ventricular internal diameter at end diastole (LVIDd), and left ventricular internal diameter in systole (LVIDs).

2.14. Reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR (RT‒qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells or ventricular tissues via TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). A total of 2 μg of RNA was subjected to reverse transcription via the First-Strand cDNA Synthesis System (TransGen Biotech). Quantitative PCR was performed via Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) on a CFX96 Touch System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

2.15. Western blot analysis

Ventricular tissues were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA; Solarbio) buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and proteinase inhibitor cocktail on ice for 30 min according to the manufacturer's protocol. A BCA protein assay kit was subsequently used to measure the protein concentration. Protein samples were loaded on a 10 % SDS‒PAGE gel and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Afterwards, the membranes were blocked with 5 % defatted milk for 2 h and incubated with primary antibodies against β-Tubulin (1:10,000; 10068-1-AP, Proteintech), LINE1 (1:1000; ab216324, Abcam), cGAS (1:1000; ab252416, Abcam), STING (1:1000; ab288157, Abcam), phospho-TBK1 (1:1000; 5483, Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-IRF3 (1:1000; 4947, Cell Signaling Technology), IFN-β (1:1000; sc-57201, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p53 (1:2000; 2524, Cell Signaling Technology), p21 (1:1000; ab188224, Abcam), H3 (1:1000; ab1791, Abcam), phospho-histone H2A.XSer139 (1:1000; 80312, Cell Signaling Technology), H3K4me3 (1:2000; ab12209, Abcam), H3K9me3 (1:2000; ab176916, Abcam), H3K27me3 (1:2000; ab6002, Abcam), CD62E (1:1000; sc-137054, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CD62P (1:1000; sc-8419, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), ALIX (1:2000; WL03063, Wanleibio), TSG101 (1:2000; ab125011, Abcam), CD9 (1:2000; ab307085, Abcam), CD63 (1:2000; WL02549, Wanleibio), α-SMA (1:2000; ab5694, Abcam), COL1A1 (1:1000; A1352, ABclonal), and COL3A1 (1:1000; A0817, ABclonal). HRP-linked secondary antibodies, including HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (H + L) and anti-rabbit IgG (H + L), were incubated with the membranes, and the HRP signal was detected via an HRP substrate (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany).

2.16. Histology and immunofluorescence analysis

The mice were euthanized, and ventricular tissues were harvested at the indicated time points. For Masson's trichrome staining, tissue samples were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 18 h, dehydrated with gradient ethanol, hyalinized with xylene, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5 μm paraffin sections. For immunofluorescence staining, samples were fixed with 4 % PFA for 18 h and dehydrated with a 30 % sucrose solution overnight before being embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and sectioned into 5-μm-thick frozen sections. For immunofluorescence staining, cryosections were incubated with primary antibodies against LINE1 (1:200; ab216324, Abcam), cGAS (1:200; ab252416, Abcam), STING (1:200; ab288157, Abcam), α-Actinin (1:250; sc-17829, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Anti-α- Sarcomeric Actinin (α-SA, 1:200; A7811, Sigma), β-Tubulin (1:500; 66240, Proteintech), CD62E (1:200; sc-137054, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CD62P (1:200; sc-8419, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CD31 (1:200; ab9498, Abcam), p21 (1:200; ab188224, Abcam), PDGFRα (1:200, ab203491, Abcam) and IFN-β (1:200; sc-57201, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4 °C overnight. The secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:500; SA00006-4, Proteintech) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:500; A-21202, Life Technologies). DAPI was used for nuclear counterstaining.

2.17. Statistical analysis

All the data are presented as the mean ± s.d. from at least three independent experiments. Significant differences between different groups were determined via two-tailed unpaired Student's t tests and one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey's test for multiple group comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. LINE1 reactivation under ischemic stress

In the mouse model of MI, the expression level of LINE1 mRNA was significantly greater in the ischemic core and peri-ischemic zone than in the remote zone (Fig. 1A–B). Furthermore, our Western blot analysis revealed significant increases in the DNA damage marker p-H2A.XSer139 and the transcriptional euchromatin marker H3 lysine-4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), as well as decreases in the heterochromatin-associated histone marks H3 lysine-9 trimethylation (H3K9me3) and H3 lysine-27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) (Fig. 1C–E), which are closely linked to the early stages of senescence in aging [2]. Moreover, we further demonstrated that DNA damage, senescence-related transcription factor p53 and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (CIP1/WAF1) also increased in accumulation with LINE1 protein expression in ischemic left ventricle tissues in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1D–E). Next, we validated whether LINE1 expression is associated with cell senescence with epigenetic derepression and genomic instability in vitro. Under oxygen‒glucose deprivation (OGD) conditions, cardiomyocytes (CMs) presented typical premature senescence phenotypes according to senescence-associated β-galactosidase (β-gal) staining (Fig. S1A), and the number of β-gal-positive cells gradually increased with prolonged OGD treatment time (Fig. S1B). Both the open reading frame (ORF) and ORF1 and ORF2 of LINE1 were significantly increased under OGD, resulting in the upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (Hif-1α) (Fig. S1C). These findings indicate that the ischemic myocardium triggers cardiac senescence and epigenetic derepression of the cardiac genome, resulting in reactivation of the LINE1 retrotransposon and suggesting a potential mechanism underlying the development of senescence in ischemic CMs.

Fig. 1.

LINE1, cardiac senescence and genomic instability respond to MI in mice. (A-B) RT‒qPCR analysis showing the expression of ORF1 and ORF2 of LINE1 in the zone, peri-infarcted zone and infarcted core of ischemic ventricular tissue on the indicated days after MI (n = 4). (C) A representative Western blot analysis revealed that the level of the DNA damage marker p-H2A.XSer139 and the epigenetic markers H3K4me3, H3K9me3, and H3K27me3 in the heart on the indicated days after MI. (D) A representative Western blot analysis confirmed the expression of the LINE1 retrotransposon and p53 and p21 in the heart at the indicated days after MI. (E) Quantitative data of the Western blot results (n = 3). All the data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. Significant differences were determined via one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD multiple comparison post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

3.2. Expression of CD62E and CD62P in MI

Ischemic injury is one of the leading causes of myocardial damage, and inflammatory activation and endothelial dysfunction are critical factors in this process [21]. Therapeutic strategies targeting the endothelium may offer a promising approach to protect the heart during ischemia and improve outcomes in MI [22]. We found that CD62E and CD62P expression increased markedly in HUVECs under OGD conditions, while no obvious trends were found in CMs or cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) (Fig. 2A). This finding was further confirmed by Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 2B and C). Consistent with our in vitro results, we observed significant upregulation of CD62E and CD62P in the vascular endothelium after MI (Fig. 2D and Fig. S2). These findings indicate that ECs exhibit rapid upregulation of CD62E and CD62P in response to ischemic injury, highlighting the potential of CD62E and CD62P as promising targets for MI therapy.

Fig. 2.

CD62E and CD62P have the capacity to serve as potential targets for MI treatment. (A) RT‒qPCR analysis showing the gene expression of various adhesion molecules, including CD62E, CD62P, CD54, CD106, and CD31, in cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, and HUVECs after 24 h of OGD treatment (n = 4). (B) Western blot analysis and quantitative data showing the expression of CD62E and CD62P in cells after 24 h of OGD treatment (n = 3). (C) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining of CD62E and CD62P in HUVECs 24 h after OGD treatment (n = 5). Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) Representative images of CD62E, CD62P and α-Actinin immunofluorescence staining in ischemic ventricular tissue (n = 4). Scale bar, 100 μm. All the data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. Significant differences were determined via one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD multiple comparison post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

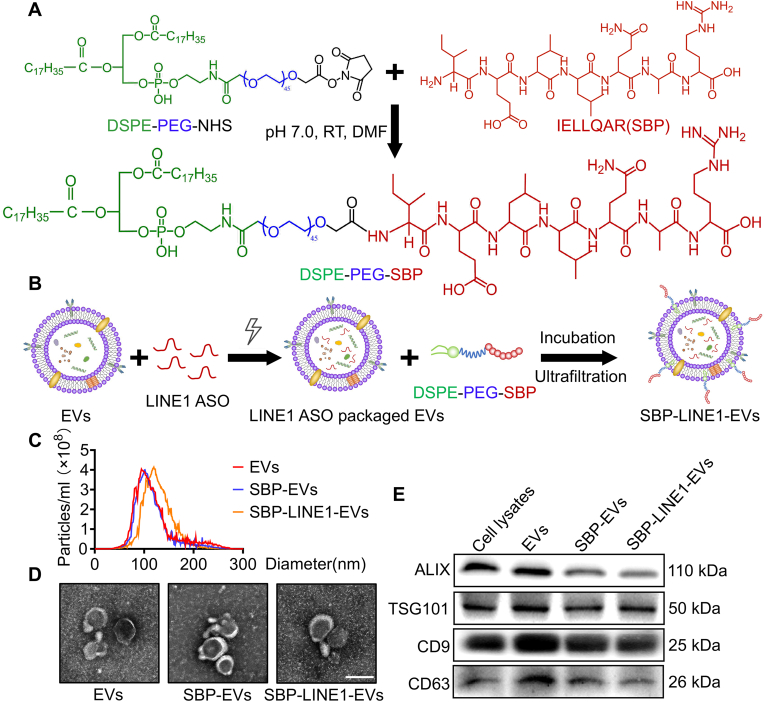

3.3. Fabrication of endothelial-targeting EVs with LINE1 ASO delivery

To design dual-function EVs that are endowed with endothelial targeting ability via LINE1 ASO delivery, we first conjugated a selectin-binding peptide (SBP; IELLQAR) on the surface of EVs via an amidation reaction to generate SBP-engineered EVs (SBP-EVs), which can specifically bind to CD62E and CD62P on injured ECs (Fig. 3A). The successful synthesis of SBP and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-n-[poly(ethylene glycol)]-SBP (DSPE-PEG-SBP) was characterized by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) and proton magnetic resonance (1H NMR) analysis (Fig. S3). Next, we designed and synthesized an ASO targeting LINE1 and loaded it into SBP-EVs via electroporation (Fig. 3B). Our results demonstrated that a 200 pmol dose of LINE1-ASO together with 4 mm cuvettes had the highest loading efficiency (∼76.3 %) according to agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. S4A), and the optimized conditions were confirmed by analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (Fig. S4B). Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) revealed that the particle size of SBP-LINE1-EVs was slightly greater than that of EVs and SBP-EVs (Fig. 3C). The morphology of SBP-LINE1-EVs was unchanged and exhibited typical round or cup-shaped vesicles after electroporation according to transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 3D). Western blot analysis revealed that EV markers were still expressed in SBP-LINE1-EVs (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Preparation and characterization of engineered endothelium-targeting and LINE1 ASO-packaged EVs. (A) Schematic illustration of the preparation of DSPE-PEG-SBP. (B) Schematic illustration of the fabrication of SBP-LINE1-EVs through internal and external modification by SBP anchoring and LINE1-ASO electroporation. (C) Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was used to analyze the particle size distributions of EVs, SBP-EVs and SBP-LINE1-EVs. (D) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of EVs and SBP-EVs. Scale bars, 100 nm. (E) Western blot analysis of the EV markers ALIX, TSG101, CD9 and CD63 in EVs, SBP-EVs, SBP-LINE1-EVs and hP-MSCs. All the data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. P values were calculated via one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD multiple comparison post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

3.4. Protective effects of SBP-LINE1-EVs

To validate the targeting effects of SBP-EVs to ECs, fluorescence images of DiI-labeled EVs revealed enhanced internalization of SBP-EVs under OGD conditions (Fig. S5A), while this trend was reduced with the blocking of CD62E and/or CD62P antibodies (Fig. S5B–C). The ability of SBP-LINE1-EVs to penetrate through injured ECs to CMs was subsequently evaluated via a Transwell system (Fig. 4A). Under normoxia, DiI-labeled EVs or SBP-EVs rarely penetrated the EC layer, and CMs showed less EV uptake (Fig. 4B), whereas injured ECs facilitated increased penetration of SBP-EVs through the EC layer, and increased internalization of SBP-EVs by CMs was observed; these effects were blocked by CD62E and CD62P antibodies (Fig. 4C–D). To investigate the delivery efficiency of SBP-LINE1-EVs, LINE1-ASO was labeled with 5-FAM. Our results revealed that OGD preconditioning improved LINE1-ASO uptake by CMs (Fig. 4E). We further investigated whether SBP-LINE-EVs could inhibit LINE1 expression and ameliorate the senescence of injured CMs induced by OGD. As expected, the expression level of LINE1 was significantly downregulated, and the number of β-gal-positive CMs was significantly reduced after treatment with SBP-LINE1-EVs but not SBP-EVs loaded with scrambled ASO (Fig. 4F–H).

Fig. 4.

In vitro assessment of the cargo transfer capacity and therapeutic potential of SBP-LINE1-EVs. (A) Experimental design for assessing the permeation effect of SBP-EVs through HUVEC monolayers. (B-D) Representative images of DiI-labeled EVs, DiI-labeled SBP-EVs and α-Actinin immunofluorescence staining of CMs in the lower chamber under normoxic conditions (B) and OGD-induced stress conditions (C). The intensity of DiI signals in the CMs was quantified (n = 6) (D). An anti-CD62E antibody and/or anti-CD62P antibody was added to the upper chamber of the hypoxic system for 2 h to block CD62E and/or CD62P in HUVECs after pretreatment with OGD. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) Immunofluorescence staining of 5-FAM-labeled LINE1-ASO delivery and α-Actinin. FAM-labeled LINE1-ASO was electroporated into EVs, and FAM-LINE1-ASO-containing SBP-EVs were added to the upper chamber of the transwell and incubated for 6 h. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) The degree of CM senescence was analyzed via β-gal staining after the internalization of SBP-LINE1-EVs, which penetrated from the upper chamber to the lower chamber of the transwell. β-gal-positive CMs under different conditions were quantified (n = 3). Scale bar, 100 μm. (G) The expression level of LINE1 in CMs was analyzed via RT‒qPCR (n = 4). (H) Representative images of β-gal-stained CMs after treatment with Scrambled ASO-packaged SBP-EVs or LINE1-ASO-packaged SBP-EVs for 24 h. Scale bar, 100 μm; n = 3. All the data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. P values were calculated via one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD multiple comparison post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

Because SBP-EVs are readily internalized by HUVECs, we investigated their effects on angiogenesis-related gene expression and endothelial function. RT‒qPCR confirmed that LINE1 expression remained stable under hypoxia, with SBP-LINE1-EVs slightly reducing LINE1 levels in HUVECs (Fig. S6A). Notably, SBP modification increased the proangiogenic potential of EVs, as Vegfa, Vegfr2, Ang1, and Ang2 were upregulated after EV incubation, with SBP-EVs and SBP-LINE1-EVs resulting in higher expression than unmodified EVs did (Fig. S6B). Tube formation assays further demonstrated that SBP modification improved endothelial function, whereas LINE1-ASO packaging had no significant effect (Fig. S6C). In summary, our findings highlight the potential of SBP-LINE1-EVs as a promising strategy in LINE1-ASO delivery for MI therapy.

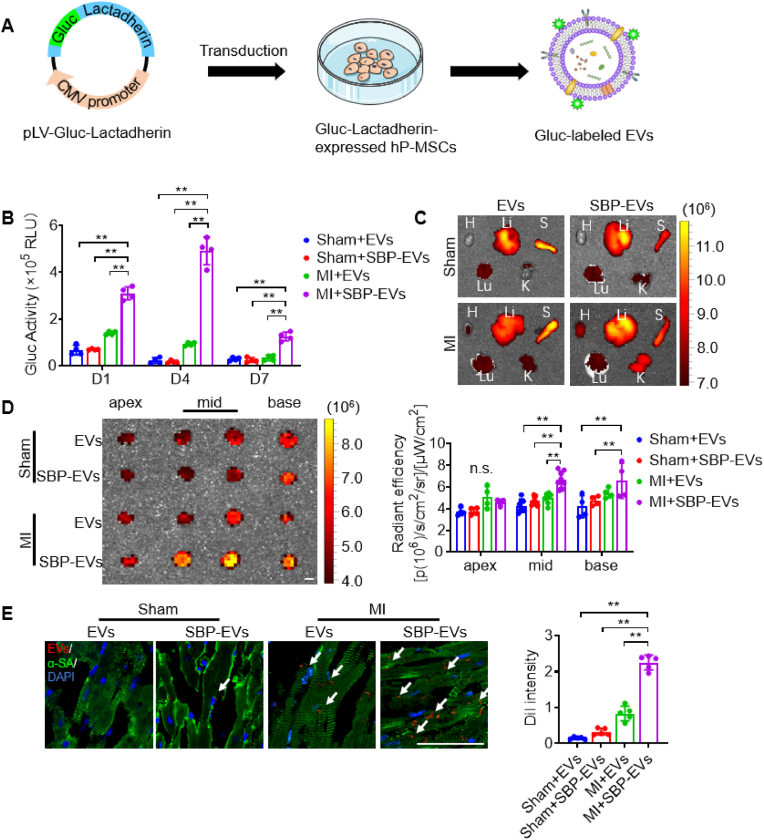

3.5. Cardiac targeting of SBP-LINE1-EVs

We next examined the biodistribution and targeting ability of SBP-LINE1-EVs in mice with MI. The Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) vector (Fig. 5A) was used to label EVs or SBP-EVs. Gluc activity tests revealed that EV retention occurred up to day 7 and reached peak levels on day 4 (Fig. 5B). In addition, DiR-labeling methods and near-infrared (NIR) imaging confirmed the targeting ability of SBP-EVs (Fig. S7A–B). To further demonstrate that SBP-EVs can be internalized by the myocardium, we injected SBP-EVs into the tail vein of mice and tracked the localization of EVs in the myocardial tissue. Two hours after injection, we observed that the fluorescence signal of EVs co-localized with vascular endothelial cells (Fig. S8). To further investigate the biodistribution dynamics of SBP-EVs, we tracked their fluorescence signals at multiple time points following intravenous injection. The results demonstrated that at 10 min post-injection, SBP-EVs were predominantly localized within larger blood vessels. By 2 h, SBP-EVs were detected in smaller capillaries and began to associate with cardiomyocytes. Notably, by 6 h post-injection, a substantial localization of SBP-EVs within cardiomyocytes was observed (Fig. S9).

Fig. 5.

Biodistribution and targeting capacity of engineered EVs in vivo. (A) Schematic illustration of the preparation of Gluc-EVs. (B) Quantification of the Gluc activity of Gluc-labeled EVs and Gluc-labeled SBP-EVs in sham or MI hearts (n = 4). (C-D)Ex vivo images of the main organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney (C) and heart sections (D), at 4 weeks post continuous injection of DiR-labeled EVs and DiR-labeled SBP-EVs. The average radiant efficiency was calculated (n = 4). H: heart, Lu: lung, S: spleen, K: kidney, Li: liver. Scale bar, 2 mm. (E) Representative images and quantification of DiI-labeled EVs or DiI-labeled SBP-EVs and immunofluorescence staining for the cardiac marker α-SA in ischemic ventricular tissue at 4 weeks post continuous injection (n = 5). EVs or SBP-EVs were indicated by arrow. Scale bar, 50 μm. All the data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. P values were calculated via one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD multiple comparison post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

We then investigated whether continuous doses of SBP-EVs for 4 weeks had cumulative effects. Although EVs and SBP-EVs preferentially accumulated in the liver and spleen, an obvious increase in DiR radiant efficiency was detected in the hearts of MI mice, indicating that SBP can improve the uptake of SBP-EVs by the ischemic myocardium (Fig. 5C–D). Furthermore, we confirmed the targeting of SBP-EVs to the myocardium of mice with MI on day 28, providing evidence of their specific affinity for injured cardiac tissue (Fig. 5E). In summary, our study revealed that SBP-LINE1-EVs preferentially accumulate in injured CMs and demonstrate enhanced targeting ability and prolonged retention within the myocardium in a mouse model of MI.

3.6. SBP-LINE1-EVs ameliorate myocardial injury

The cardioprotective effects of SBP-LINE1-EVs were further evaluated in a mouse MI model (Fig. 6A). Cardiac recovery from SBP-LINE1-EV therapy was evaluated by staining with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) (Fig. 6B). The administration of SBP-LINE1-EVs resulted in significant restoration after MI injury, with decreased serum levels of creatine kinase-myocardial band isoenzyme (CK-MB) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (Fig. 6C–D). We next performed serial echocardiography to evaluate left ventricular (LV) function, and the data revealed that SBP-LINE1-EVs significantly improved the left ventricular ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular internal diameter at end diastole (LVIDd), and Left Ventricular Internal Diameter in Systole (LVIDs) significantly (Fig. 6E). Masson's trichrome staining was used to assess pathological cardiac remodeling. The results showed that the injection of SBP-LINE1-EVs significantly alleviated cardiac fibrosis (Fig. 6F). Consequently, the expression levels of fibrosis-related mRNAs and proteins, including α-SMA, COL1A1, and COL3A1, were evaluated via RT‒qPCR and Western blot. Our results demonstrated that SBP-LINE1-EVs significantly alleviated cardiac fibrosis (Fig. 6G, S10). We also conducted additional experiments incorporating SBP-Scr-EVs (SBP-EVs loaded with scrambled ASO) as a control group to further validate our findings (Fig. S11). These results further confirm that the therapeutic effects observed in our study are sequence-specific and not due to nonspecific effects of ASO delivery.

Fig. 6.

SBP-LINE1-EVs improved myocardial infarction injury and reduced adverse cardiac remodeling in mice. (A) Experimental schedule showing the study design of the treatments for EVs, SBP-EVs and SBP-LINE1-EVs. (B) TTC staining images and quantification were performed to evaluate the infarct area of ischemic ventricle tissue via vein injection of PBS, EVs, SBP-EVs or SBP-LINE1-EVs (n = 4). Scale bar, 2 mm. (C-D) Serum levels of creatine kinase-myocardial band isoenzyme (CK-MB) (C) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (D) in mice treated with EVs, SBP-EVs or SBP-LINE1-EVs on day 4 (n ≥ 12). (E) Representative images of M-mode echocardiography. Statistical analysis of cardiac function revealed significant improvements in the left ventricular ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular internal diameter at end diastole (LVIDd), and left ventricular internal diameter in the sole (LVIDs) on days 7 and 14 (n = 5). (F) Representative images of Masson's trichrome staining on day 28 after MI. The infarct size of the left ventricle was quantified via Masson's trichrome staining (n = 5). Scale bar, 1 mm. (G) Western blot images and quantitative data of the expression of cardiac fibrosis-related genes, including α-SMA, COL1A1, and COL3A1, in ventricle tissue from each group of mice on day 28 after MI (n = 3). All the data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. P values were calculated via one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD multiple comparison post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

3.7. SBP-LINE1-EVs modulated cardiac senescence and SASP secretion by inhibiting the cGAS-STING signaling pathway

Recent studies have revealed that retrotransposons, including LINE1 retrotransposons and human endogenous retrovirus (HERV), are reactivated in normal and abnormal senescent cells and lead to deleterious effects through epigenetic changes and the activation of immune pathways or the accumulation of senescent cells and SASP effects [11,23,24]. We observed a significant reduction in LINE1 expression only after administering SBP-LINE1-EVs, which indicated their specific efficacy in suppressing LINE1 expression (Fig. 7A). We subsequently assessed myocardial senescence in mice following MI injury with various treatments. Our results demonstrated that the administration of SBP-LINE1-EVs had notable antiaging effects according to the results of β-gal staining (Fig. 7B). The modulatory effect of SBP-LINE1-EVs on antiaging effects was also confirmed by immunofluorescence staining for p21, a marker of cellular senescence (Fig. S12A). We further evaluated the impact of SBP-LINE1-EVs on the cGAS/STING‐dependent innate immune response, and SBP-LINE1-EV therapy resulted in notable downregulation of cGAS and STING expression in CMs (Fig. 7C–D). In addition, our data confirmed SBP-LINE1-EVs as antagonists of the cGAS/STING pathway, which inhibited downstream phosphorylated TANK-binding kinase 1 (p-TBK1), phosphorylated interferon regulatory factor 3 (p-IRF3) and the type I interferon response, including IFN-β production, in the ischemic myocardium of MI mice (Fig. 7E–F).

Fig. 7.

SBP-LINE1-EVs relieved cardiac senescence and the innate immune response by maintaining genomic stability and inhibiting the cGAS-STING signaling pathway. (A) Representative images of LINE1 and the cardiac marker α-SA immunofluorescence staining of ventricle tissue in each group of mice at 28 days after MI. The expression of LINE1 was quantified (n = 5). Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Representative images of β-gal-stained samples from each group of mice at 28 days after MI (n = 5). (C-D) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining for the cytoplasmic DNA sensors cGAS (C) and STING (D) in ventricular tissue from each group of mice 28 days after MI. The expression of cGAS and STING was quantified (n = 5). Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) Representative images of IFN-β immunofluorescence staining of ventricle tissue in each group of mice 28 days after MI, and the expression of IFN-β was quantified (n = 5). Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) Western blot images of LINE1, cGAS, and STING and their downstream phosphorylated forms of TBK1, phosphorylated forms of IRF3, and IFN-β, and the DNA damage marker p53 together with the senescence marker p21 in ventricle tissue from each group of mice at 28 days after MI (n = 3). (G) Western blot images of the DNA damage marker p-H2A.XSer139 and the epigenetic markers H3K4me3, H3K9me3, and H3K27me3 in the ventricle tissue of each group of mice at 28 days after MI (n = 3). All the data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. P values were calculated via one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD multiple comparison post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, n ≥ 6.

Growing evidence suggests that retrotransposons, such as LINE1, serve as upstream stimuli and cis-regulatory elements that initiate tumorigenesis, heterochromatin loss, DNA damage, the SASP response, and age-associated inflammation [5,23,25]. Therefore, we investigated the state of accessibility and damage to chromatin, together with the expression of SASP genes. The administration of SBP-LINE1-EVs resulted in increased histone modifications of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 and decreased H3K4me3, p53 and p-H2A.XSer139, which indicated that SBP-LINE1-EVs were more inclined to promote heterochromatin formation and inhibited genomic damage (Fig. 7F–G, S13). SASP factors, including interleukin (IL-1β, IL-6) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-3), were upregulated in the PBS, EV and SBP-EV groups compared with the sham group, whereas the expression of these genes was normalized after SBP-LINE1-EV treatment (Fig. S12B).

In addition, we performed additional in vitro experiments using CMs and Western blot analysis to assess the pathway (Fig. S14). Our results demonstrated that, compared with SBP-Scr-EV treatment, SBP-LINE1-EV treatment led to a further reduction in LINE1 expression and corresponding suppression of the cGAS-STING-TBK1-IRF3 signaling pathway in CMs. Overall, our findings provide compelling evidence that SBP-LINE1-EVs effectively protect against myocardial senescence by inhibiting the reactivation of the innate immune cGAS-STING-TBK1-IRF3 pathway induced by LINE1 derepression.

3.8. Biosafety evaluation of SBP-LINE1-EVs

The hemocompatibility of SBP-EVs and SBP-LINE1-EVs was assessed prior to their use in experiments for MI treatment. The hemolytic test indicated that after incubation with EVs, SBP-EVs, and SBP-LINE1-EVs, the cell integrity of red blood cells (RBCs) was similar to that of RBCs treated with PBS (Fig. S15A). The serum samples and major organs of the mice subjected to different treatments on day 28 were collected, and serum biochemical indices, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr) levels, were examined to evaluate the biocompatibility of SBP-LINE1-EVs. There were no significant changes in these indices after the administration of SBP-EVs or SBP-LINE1-EVs compared with the other groups (Fig. S15B). H&E staining of the liver, spleen, lung, kidney and small intestine indicated that SBP-EVs and SBP-LINE1-EVs were not toxic to these organs after injection (Fig. S15C). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the dual modification of the hydrophobic insertion strategy and electroporation did not impair further clinical applications of SBP-LINE1-EVs for the antiaging therapy of MI.

4. Discussion

In this study, we first revealed that the LINE1 retrotransposon was overexpressed and may be a key target for therapeutic molecules for MI. Furthermore, we confirmed the viability of selectin family molecules, such as CD62E and CD62P, as candidates for targeted delivery to the ischemic cardiac endothelium. Given the critical role of endothelial cells in post-MI inflammation, angiogenesis, and vascular remodeling, we chose to target damaged endothelial cells to enhance myocardial repair. Endothelial cells not only facilitate immune cell trafficking to the infarcted area but also contribute to vascular regeneration, making them effective targets for therapeutic EVs. Accordingly, we developed SBP-engineered EVs with the capacity for targeted delivery and equipped them with LINE1 ASO to achieve therapeutic effects. Our results demonstrated that SBP-LINE1-EVs could accumulate greatly in ischemic CMs by binding selectins and further restore cardiac structure and function by inhibiting LINE1 reactivation (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram depicting the therapeutic effects of intravenous administration of SBP-LINE-EVs for MI treatment. SBP-LINE1-EVs exhibit a selective targeting tendency to the injured heart with an enhanced myocardial protection effect by LINE1-ASO delivery. SBP-LINE1-EVs protected against myocardial senescence by inhibiting reactivation of the innate immune cGAS-STING-TBK1-IRF3 pathway and further repressing the expression of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors.

Identification of the crucial physiological role of cardiac senescence is the key to developing a CVD-related therapeutic strategy and minimizing subsequent distal cascades [3,21]. Accumulating evidence has established a link between senescent cell accumulation and SASP component production/release with age-related cardiac pathologies, including heart failure, MI, and chemotherapy-associated cardiotoxicity [[26], [27], [28]]. However, the exact mechanism by which senescent cells contribute to these processes is unclear. Emerging evidence suggests that transposons function as crucial signaling molecules in cellular aging, playing a pivotal role in establishing the pro-inflammatory microenvironment associated with aging and exacerbating age-related organ dysfunction [5,29]. Elucidating the causal association between transposons and myocardial aging, as well as characterizing the response of LINE1 to MI and cellular aging, may provide valuable insights for the development of novel clinical interventions aimed at mitigating MI. In mammals, retrotransposons, DNA damage, interferons, and inflammation are intricately intertwined [30]. Our findings support the conclusion that retrotransposons activated during the aging process are erroneously recognized as invading pathogens and serve as important driving factors for sterile inflammation, leading to many age-related diseases.

The molecular mechanism of cellular senescence in multiple CVDs, including cardiac fibrosis and MI injury, can involve diverse cell types [31]. As the cell type with the highest proportion of total cardiac volume, CM senescence results in impaired shortening, an increased frequency of pacing, contractile and metabolic dysfunction, and elevated secretion of SASP factors, including pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and proteases [21,31]. A previous study demonstrated that the expression of LINE1 in adult rat cardiac tissue and the inhibition of LINE1 expression during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion can protect the cardiac structure and function of the rat heart through the Akt/PKB signaling pathway [32]. Our study performed a more comprehensive analysis to better understand the relationship between myocardial aging and LINE1 expression and to further elucidate the regulatory role of LINE1 reactivation in CVDs.

Systemic administration of EVs results in rapid clearance or sequestration in organs such as the liver, spleen, and lungs [33]. In this study, we revealed that the selectin family proteins CD62E and CD62P in ECs are alarm molecules indicating initial myocardial ischemic injury. On the basis of the packaging of LINE1 ASO, EVs were modified with SBP to target ECs for cardiac homing. Notably, targeting ECs rather than directly targeting CMs is a strategy aimed at leveraging the endothelial dysfunction that characterizes post-MI injury. By utilizing the upregulation of selectins on activated ECs, this approach enhances the biodistribution and delivery of therapeutic EVs to the infarcted myocardium, indirectly facilitating their interaction with CMs through paracrine signaling and trans-endothelial migration. Our findings suggest that the SBP modification of EVs is the key determinant for enhancing EC function, whereas the presence of LINE1 in SBP-LINE1-EVs may contribute primarily to other cellular processes beyond the scope of endothelial function. However, the large size and autofluorescence of adult CMs pose challenges for flow cytometry-based quantification of DiI-labeled EV uptake, highlighting a limitation that may be addressed with alternative imaging or sorting techniques in future studies. Understanding the relationships among SBP modification, LINE1, and ECs can provide valuable insights for further optimizing the design and application of EV-based therapies for CVDs.

As a signaling pathway that mediates the endogenous type I interferon response, cGAS-STING has been shown to contribute to the development of excessive tissue destruction and heart failure in CVD patients [34]. Furthermore, by recognizing activated LINE1 DNA in the cytoplasm, cGAS/STING can further promote cellular and organ aging by inducing the SASP and the inflammatory microenvironment [23]. In this study, the delivery of LINE1-ASO via SBP-LINE1-EVs efficiently suppressed the overexpression of LINE1 in myocardial tissue. Although we provided evidence indicating the associations among LINE1 overexpression, epigenetic alterations and myocardial senescence, we cannot exclude the possibility that expression changes in other epigenetic regulatory factors, such as SUV39H (suppressor of variegation 3-9 homolog) or FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated protein), may also contribute to LINE1 reactivation and pro-inflammatory-related epigenetic derepression and play important roles in the context of aging and fibrosis in CVD patients [35,36]. It is necessary to investigate whether RNA sensors, including RIG1 and MDA5, are involved in LINE1-mediated cardiac senescence [37].

Furthermore, the main findings of this study are based on mouse samples. To determine whether human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K, also known as HML-2), which belongs to relatively new subfamilies of HERV proviruses, is similarly overexpressed in patients with MI, further investigation using larger clinical sample sizes and primate animal models is needed [24]. Although CMs are currently the cell type most affected by cardiac aging and the STING-IRF3 pathway in CMs exacerbates lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial injury, resident and circulating macrophages play crucial roles in the regulation of angiogenesis and fibrosis in response to cardiac stress [[38], [39], [40], [41]]. Inhibition of the cGAS‒STING pathway by LINE1 ASO may modulate the recruitment, polarization, and activation of T cells, which are essential for myocardial inflammation and tissue repair after MI. Future studies are needed to explore the immunomodulatory effects of LINE1 ASO and its impact on multicellular interactions during the LINE1-mediated fibroinflammatory response. Future systematic studies are needed to characterize multicellular interactions during LINE1-mediated fibroinflammatory cascades.

5. Conclusion

In summary, the LINE1 retrotransposon, the most abundant TE, responds to CM injury and propagates in the MI model. We further developed selectin binding peptide (SBP)-engineered EVs with endothelial-targeted functions loaded with LINE1 ASO. Engineered EVs mitigate myocardial senescence by suppressing reactivation of the cGAS-STING‐TBK1‐IRF3 pathway and the expression of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors. This model paves the way for cardiac protection and the therapeutic potential of EVs through targeted manipulation of TE activity.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Enze Fu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Kai Pan: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Benjamin Hinnant: Writing – original draft, Software, Data curation, Conceptualization. Shang Chen: Validation, Methodology, Investigation. Zhibo Han: Software, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Zhikun Guo: Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization. Zhong-chao Han: Supervision, Resources, Investigation, Conceptualization. Qiong Li: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization. Zongjin Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The care and experimentation involving animals adhered to the guidelines provided by the Nankai University Animal Care and Use Committee (approval No. 20220022).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82472169), the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0103200), the Tianjin Natural Science Foundation (22JCZXJC00170), and open funding from the Nankai University Eye Institute (NKYKD202203).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Zhibo Han and Zhong-chao Han are currently employed by Tianjin Key Laboratory of Engineering Technologies for Cell Pharmaceutical, National Engineering Research Center for Cell Products, AmCellGene Co., Ltd.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of editorial board of Bioactive Materials.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2025.07.008.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Li J., Sun S., Zhu D., Mei X., Lyu Y., Huang K., Li Y., Liu S., Wang Z., Hu S., Lutz H.J., Popowski K.D., Dinh P.C., Butte A.J., Cheng K. Inhalable stem cell exosomes promote heart repair after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2024;150(9):710–723. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez-Otin C., Blasco M.A., Partridge L., Serrano M., Kroemer G. Hallmarks of aging: an expanding universe. Cell. 2023;186(2):243–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehdizadeh M., Aguilar M., Thorin E., Ferbeyre G., Nattel S. The role of cellular senescence in cardiac disease: basic biology and clinical relevance. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022;19(4):250–264. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00624-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Z., Zhang W., Qu J., Liu G.H. Emerging epigenetic insights into aging mechanisms and interventions. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2024;45(2):157–172. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2023.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorbunova V., Seluanov A., Mita P., McKerrow W., Fenyo D., Boeke J.D., Linker S.B., Gage F.H., Kreiling J.A., Petrashen A.P., Woodham T.A., Taylor J.R., Helfand S.L., Sedivy J.M. The role of retrotransposable elements in ageing and age-associated diseases. Nature. 2021;596(7870):43–53. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03542-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Z., Qu J., Zhang W., Liu G.H. Stress, epigenetics, and aging: unraveling the intricate crosstalk. Mol. Cell. 2024;84(1):34–54. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decout A., Katz J.D., Venkatraman S., Ablasser A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021;21(9):548–569. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00524-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamdzyk M., Doycheva D.M., Araujo C., Ocak U., Luo Y., Tang J., Zhang J.H. cGAS/STING pathway activation contributes to delayed neurodegeneration in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia rat model: possible involvement of LINE-1. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020;57(6):2600–2619. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-01904-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao K., Du J., Peng Y., Li P., Wang S., Wang Y., Hou J., Kang J., Zheng W., Hua S., Yu X.F. LINE1 contributes to autoimmunity through both RIG-I- and MDA5-mediated RNA sensing pathways. J. Autoimmun. 2018;90:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun Z., Zhang R., Zhang X., Sun Y., Liu P., Francoeur N., Han L., Lam W.Y., Yi Z., Sebra R., Walsh M., Yu J., Zhang W. LINE-1 promotes tumorigenicity and exacerbates tumor progression via stimulating metabolism reprogramming in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01618-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Della Valle F., Reddy P., Yamamoto M., Liu P., Saera-Vila A., Bensaddek D., Zhang H., Prieto Martinez J., Abassi L., Celii M., Ocampo A., Nunez Delicado E., Mangiavacchi A., Aiese Cigliano R., Rodriguez Esteban C., Horvath S., Izpisua Belmonte J.C., Orlando V. LINE-1 RNA causes heterochromatin erosion and is a target for amelioration of senescent phenotypes in progeroid syndromes. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14(657) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abl6057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng K., Kalluri R. Guidelines for clinical translation and commercialization of extracellular vesicles and exosomes based therapeutics. Extracellular Vesicle. 2023;2 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang K., Li R., Chen X., Yan H., Li H., Zhao X., Huang H., Chen S., Liu Y., Wang K., Han Z., Han Z.C., Kong D., Chen X.M., Li Z. Renal endothelial cell-targeted extracellular vesicles protect the kidney from ischemic injury. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 2023;10(3) doi: 10.1002/advs.202204626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu E., Li Z. Extracellular vesicles: a new frontier in the theranostics of cardiovascular diseases. iRADIOLOGY. 2024;2:240–259. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu D., Liu S., Huang K., Wang Z., Hu S., Li J., Li Z., Cheng K. Intrapericardial exosome therapy dampens cardiac injury via activating Foxo3. Circ. Res. 2022;131(10):e135–e150. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.321384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu D., Liu S., Huang K., Li J., Mei X., Li Z., Cheng K. Intrapericardial long non-coding RNA-Tcf21 antisense RNA inducing demethylation administration promotes cardiac repair. Eur. Heart J. 2023;44(19):1748–1760. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang L., Li Z., Ma T., Han Z., Du W., Geng J., Jia H., Zhao M., Wang J., Zhang B., Feng J., Zhao L., Rupin A., Wang Y., Han Z.C. Transplantation of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviates critical limb ischemia in diabetic nude rats. Cell Transplant. 2017;26(1):45–61. doi: 10.3727/096368916X692726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao X., Liu Y., Gao J., Yang L., Mao D., Stefanitsch C., Li Y., Zhang J., Ou L., Kong D., Zhao Q., Li Z. Nitric oxide releasing hydrogel enhances the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells for myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 2015;60:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Z., Lee A., Huang M., Chun H., Chung J., Chu P., Hoyt G., Yang P., Rosenberg J., Robbins R.C., Wu J.C. Imaging survival and function of transplanted cardiac resident stem cells. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;53(14):1229–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao X., Liu Y., Jia P., Cheng H., Wang C., Chen S., Huang H., Han Z., Han Z.C., Marycz K., Chen X., Li Z. Chitosan hydrogel-loaded MSC-derived extracellular vesicles promote skin rejuvenation by ameliorating the senescence of dermal fibroblasts. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021;12(1):196. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02262-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen M.S., Lee R.T., Garbern J.C. Senescence mechanisms and targets in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022;118(5):1173–1187. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvab161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Q., He G.W., Underwood M.J., Yu C.M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of endothelial ischemia/reperfusion injury: perspectives and implications for postischemic myocardial protection. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(2):765–777. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Cecco M., Ito T., Petrashen A.P., Elias A.E., Skvir N.J., Criscione S.W., Caligiana A., Brocculi G., Adney E.M., Boeke J.D., Le O., Beausejour C., Ambati J., Ambati K., Simon M., Seluanov A., Gorbunova V., Slagboom P.E., Helfand S.L., Neretti N., Sedivy J.M. L1 drives IFN in senescent cells and promotes age-associated inflammation. Nature. 2019;566(7742):73–78. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0784-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X., Liu Z., Wu Z., Ren J., Fan Y., Sun L., Cao G., Niu Y., Zhang B., Ji Q., Jiang X., Wang C., Wang Q., Ji Z., Li L., Esteban C.R., Yan K., Li W., Cai Y., Wang S., Zheng A., Zhang Y.E., Tan S., Cai Y., Song M., Lu F., Tang F., Ji W., Zhou Q., Belmonte J.C.I., Zhang W., Qu J., Liu G.H. Resurrection of endogenous retroviruses during aging reinforces senescence. Cell. 2023;186(2):287–304 e26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Cecco M., Criscione S.W., Peckham E.J., Hillenmeyer S., Hamm E.A., Manivannan J., Peterson A.L., Kreiling J.A., Neretti N., Sedivy J.M. Genomes of replicatively senescent cells undergo global epigenetic changes leading to gene silencing and activation of transposable elements. Aging Cell. 2013;12(2):247–256. doi: 10.1111/acel.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Januzzi J.L., Jr., Packer M., Claggett B., Liu J., Shah A.M., Zile M.R., Pieske B., Voors A., Gandhi P.U., Prescott M.F., Shi V., Lefkowitz M.P., McMurray J.J.V., Solomon S.D. IGFBP7 (Insulin-Like growth factor-binding Protein-7) and neprilysin inhibition in patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(10) doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spallarossa P., Altieri P., Aloi C., Garibaldi S., Barisione C., Ghigliotti G., Fugazza G., Barsotti A., Brunelli C. Doxorubicin induces senescence or apoptosis in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes by regulating the expression levels of the telomere binding factors 1 and 2. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;297(6):H2169–H2181. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00068.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu F., Li Y., Zhang J., Piao C., Liu T., Li H.H., Du J. Senescent cardiac fibroblast is critical for cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H., Li J., Yu Y., Ren J., Liu Q., Bao Z., Sun S., Liu X., Ma S., Liu Z., Yan K., Wu Z., Fan Y., Sun X., Zhang Y., Ji Q., Cheng F., Wei P.H., Ma X., Zhang S., Xie Z., Niu Y., Wang Y.J., Han J.J., Jiang T., Zhao G., Ji W., Izpisua Belmonte J.C., Wang S., Qu J., Zhang W., Liu G.H. Nuclear lamina erosion-induced resurrection of endogenous retroviruses underlies neuronal aging. Cell Rep. 2023;42(6) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angileri K.M., Bagia N.A., Feschotte C. Transposon control as a checkpoint for tissue regeneration. Development. 2022;149(22) doi: 10.1242/dev.191957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang X., Li P.H., Chen H.Z. Cardiomyocyte senescence and cellular communications within myocardial microenvironments. Front. Endocrinol. 2020;11:280. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lucchinetti E., Feng J., Silva R., Tolstonog G.V., Schaub M.C., Schumann G.G., Zaugg M. Inhibition of LINE-1 expression in the heart decreases ischemic damage by activation of Akt/PKB signaling. Physiol. Genom. 2006;25(2):314–324. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00251.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Escude Martinez de Castilla P., Tong L., Huang C., Sofias A.M., Pastorin G., Chen X., Storm G., Schiffelers R.M., Wang J.W. Extracellular vesicles as a drug delivery system: a systematic review of preclinical studies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021;175 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao D.J., Schiattarella G.G., Villalobos E., Jiang N., May H.I., Li T., Chen Z.J., Gillette T.G., Hill J.A. Cytosolic DNA sensing promotes macrophage transformation and governs myocardial ischemic injury. Circulation. 2018;137(24):2613–2634. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang G., Weng X., Zhao Y., Zhang X., Hu Y., Dai X., Liang P., Wang P., Ma L., Sun X., Hou L., Xu H., Fang M., Li Y., Jenuwein T., Xu Y., Sun A. The histone H3K9 methyltransferase SUV39H links SIRT1 repression to myocardial infarction. Nat. Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathiyalagan P., Adamiak M., Mayourian J., Sassi Y., Liang Y., Agarwal N., Jha D., Zhang S., Kohlbrenner E., Chepurko E., Chen J., Trivieri M.G., Singh R., Bouchareb R., Fish K., Ishikawa K., Lebeche D., Hajjar R.J., Sahoo S. FTO-dependent N(6)-Methyladenosine regulates cardiac function during remodeling and repair. Circulation. 2019;139(4):518–532. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dhillon P., Mulholland K.A., Hu H., Park J., Sheng X., Abedini A., Liu H., Vassalotti A., Wu J., Susztak K. Increased levels of endogenous retroviruses trigger fibroinflammation and play a role in kidney disease development. Nat. Commun. 2023;14(1):559. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36212-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y., Zheng Y., Wang S., Fan Y., Ye Y., Jing Y., Liu Z., Yang S., Xiong M., Yang K., Hu J., Che S., Chu Q., Song M., Liu G.H., Zhang W., Ma S., Qu J. Single-nucleus transcriptomics reveals a gatekeeper role for FOXP1 in primate cardiac aging. Protein Cell. 2023;14(4):279–293. doi: 10.1093/procel/pwac038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li N., Zhou H., Wu H., Wu Q., Duan M., Deng W., Tang Q. STING-IRF3 contributes to lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac dysfunction, inflammation, apoptosis and pyroptosis by activating NLRP3. Redox Biol. 2019;24 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Revelo X.S., Parthiban P., Chen C., Barrow F., Fredrickson G., Wang H., Yucel D., Herman A., van Berlo J.H. Cardiac resident macrophages prevent fibrosis and stimulate angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2021;129(12):1086–1101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King K.R., Aguirre A.D., Ye Y.X., Sun Y., Roh J.D., Ng R.P., Jr., Kohler R.H., Arlauckas S.P., Iwamoto Y., Savol A., Sadreyev R.I., Kelly M., Fitzgibbons T.P., Fitzgerald K.A., Mitchison T., Libby P., Nahrendorf M., Weissleder R. IRF3 and type I interferons fuel a fatal response to myocardial infarction. Nat. Med. 2017;23(12):1481–1487. doi: 10.1038/nm.4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.