Abstract

Background

Rhodococcus equi is an intracellular bacterial pathogen that can cause infections in various hosts, including humans and animals. Host-associated virulence plasmids have been identified as key contributors to the pathogenicity of R. equi and potentially play a role in determining the host tropism of the bacteria. The investigation of additional clinical and environmental isolates is likely to provide novel insights into the population structure, infection pathways, and drug resistance of this important pathogen. We combined whole-genome sequencing and antimicrobial-susceptibility testing of 37 selected R. equi isolates from animal, human, and environmental sources, collected in Switzerland over a 21 year period. In addition, we gathered a total of 251 whole-genome sequences and 141 multi-locus sequence (MLST) typing records from public sources. Although large geographical areas are not represented due to missing genomes we used a phylogenetic approach to define diversity patterns, distribution, and host tropism of R. equi.

Results

Horse isolates, irrespective of the country of isolation, exhibited distinct sequence types (ST), notably ST-1 and ST-24 among others, and carried the VAPA plasmid, implying a strain-specific affinity for particular plasmid types. Several STs including ST-62 and ST-76 associated with the VAPN plasmid included both human and ruminant isolates from Switzerland, hinting at a potential common infection source. Similarly, isolates from porcine and human sources, documented in various European countries and China, exhibited common ST, including ST-18 and ST-36, and were found to harbour VAPB plasmids upon testing, suggesting potential zoonotic implications.

Conclusions

Using a genomic approach we report host-specific strains that serve as carriers of virulence-associated plasmids, indicating an adaptation strategy within distinct R. equi lineages. The existence of shared plasmid profiles between farm animals and humans suggests a common infection source. Our results contribute to an improved understanding of the global genetic diversity of virulent and environmental R. equi strains, which will benefit from additional molecular epidemiological studies including strains from unrepresented geographical areas.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-025-04152-8.

Keywords: Rhodococcus equi, Comparative genomics, Phylogenomics, Susceptibility testing, Host-associated virulence plasmids, Host tropism

Background

Rhodococcus equi (homotypic synonym Prescottella equi) is a Gram-positive, soil-dwelling, aerobic actinomycete bacterium that infects animals and humans. It was originally designated Corynebacterium equi and first isolated from foals with pneumonia in 1922 [1]. Thereafter, R. equi has been recognized as an animal pathogen causing pulmonary pyogranulomatous infections and occasionally septic arthritis, ulcerative lymphangitis, mesenteric lymph node abscesses, and pleuritis [2].

Rhodococcus equi strains exhibit significant phylogenomic divergence from other rhodococci, leading to a proposal for their placement in a newly proposed genus, Prescottella, alongside R. defluvii, R. agglutinans, R. soli, and R. subtropicus [3–5]. The taxonomic history of this pathogen has been intricate, involving two Requests for an Opinion presented to the Judicial Commission [4]. Recently, Val-Calvo and Vázquez-Boland proposed reclassifying the genus Prescottella and its members into the genus Rhodococcus [6]. This proposal is based on normalized tree clustering and network analysis of several genomic relatedness indices. Unfortunately, these frequent taxonomic alterations have not facilitated microbiologists, clinicians, researchers, and affected patients to gather information about this Gram-positive bacterium. For the sake of understandability, hereafter we will refer to the R. equi/R. hoagii/P. equi taxon as R. equi.

Foals younger than six months are particularly susceptible to pulmonary pyogranulomatous infections with R. equi [7]. Extrapulmonary manifestations, such as ulcerative enterocolitis and typhlitis, mesenteric granulomatous adenitis and less commonly polyarthritis, osteomyelitis, ocular lesions and hepatic and renal abscessation have been reported, with and without concurrent pulmonary infection [7, 8]. In addition to equine species, R. equi is repeatedly found in pigs with and without macroscopic lesions and occasionally in other domesticated species including cattle, cats, and dogs with wound infections, subcutaneous abscesses, vaginitis, hepatitis, osteomyelitis, myositis, and joint infections [9, 10]. The first case of human infection was reported in 1967 in a patient with severe hepatic dysfunction receiving immunosuppressive therapy and presenting cavitating pneumonia [11]. However, until the advent of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic in the early 1980 s, only sporadic cases were reported in humans [12]. Since then, a dramatic increase of human infections occurred, making R. equi an emerging pathogen for immunocompromised patients [13–16]. Most patients show pulmonary involvement and extrapulmonary lesions include subcutaneous abscesses or lymphadenitis. Before appropriate antiretroviral therapy was accessible to AIDS patients, high mortality rates (54.5 − 58.3%) due to R. equi coinfections were reported, depending on the adopted antimicrobial regimen and chemosensitivity of the strain [14, 17]. Although highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) combined with anti-rhodococcal therapy ameliorate the outcome of HIV-infected patients, rhodococcosis remains a cause of death in immunocompromised people [18].

Comparative genomics and phylogenomics studies have the potential to elucidate and understand the genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships of R. equi strains and their hosts. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) has been proposed as a tool to investigate the molecular epidemiology of R. equi [19]. However, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has boosted resolution and has become the new reference standard for typing [20]. The additional information provided by WGS-generated data has the potential to improve our understanding of Rhodococcus ecology, epidemiology, and evolution, in particular the transmission of virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) determinants [21, 22].

The virulence of R. equi is determined by circular and linear virulence-associated plasmids (pVAP) harboring genes encoding for virulence-associated proteins (Vaps) [23–25]. The vap genes are encoded in horizontally acquired pathogenicity islands (PAI), which confer the ability to parasitize macrophages and replicate intracellularly. Loss of the pVAP renders the bacteria unable to persist inside macrophages in vitro [26, 27]. Experimental investigations revealed that, among the twenty open reading frames within the PAI, only three — namely virR, virS, and vapA — are essential for intracellular replication in macrophages [25, 28–30]. The genes virR and virS play a pivotal role as transcriptional regulators essential for the expression of vapA, whereas vapA codes for the highly immunogenic protein known as virulence-associated protein A (VapA) [30, 31].

Currently, three distinct R. equi plasmids associated with virulence and host preferences have been identified, namely pVAPA, pVAPB, and pVAPN [23, 32–35]. Equine and porcine isolates generally harbour circular plasmids, pVAPA and pVAPB, respectively, while the linear type known as pVAPN has been identified among bovine isolates [25, 33]. Contrary to clinical isolates, environmental R. equi strains generally do not carry VAPs and isolates from animal sources without plasmids are most likely the result of transient colonization or opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients [33, 36]. Rhodococcus equi isolates both with and without plasmids have been documented in cases of human infection, especially in people living with HIV/AIDS [37, 38]. Depending on the host species, the pathogenicity of strains carrying a particular type of plasmid can vary significantly. As demonstrated by Takai and colleagues, the presence of the vapA gene confers increased virulence to R. equi strains in mice, while those with the vapB gene are classified as intermediately virulent [35]. In contrast, environmental R. equi strains commonly lack the virulence plasmids [33]. Recently, R. equi infections in other species than horse, in particular in swine and wild boar, have aroused considerable interest due to possible foodborne transmission to humans. Various infection rates were reported from slaughtered pigs and hunted wild boar with and up to 26% and 52% positivity in lymph nodes, respectively [39, 40]. The emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains of R. equi further highlights the importance of understanding the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment of infections caused by this organism [41, 42]. Prolonged treatment with rifampin in combination with a macrolide, e.g. clarithromycin or erythromycin is the actual cornerstone for foal rhodococcosis therapy and the addition of fluoroquinolones and vancomycin is recommended for human patients [43]. Information regarding efficacy of antimicrobials against this pathogen, their application in different host species, and the clinical outcome are crucial for successful treatment of new patients. Breakpoints for certain relevant drugs are still missing and minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of clinical and environmental isolates are needed. Moreover, several antimicrobial classes listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “critically important” for humans, such as fluoroquinolones, third and later-generation cephalosporins, and macrolides are routinely used in veterinary medicine, especially for equine and small animal patients [44].

In order to reduce the occurrence of inappropriate antibiotic administration, it is advisable to utilize culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing as well as fast and accurate molecular methods to inform treatment for suspected bacterial infections whenever feasible [45, 46]. In instances where empirical antimicrobial therapy is required for critically ill patients, therapeutic options should be selected based on the suspected pathogens involved and their susceptibility, including up-to-date information from the same geographical region. To make sound decisions in such situations, access to antimicrobial-susceptibility testing (AST) and current data on AMR surveillance is critical for clinicians. This study aimed to determine the diversity of R. equi, describe the occurrence and distribution of virulence traits and delineate the geographical and host linkage of this opportunistic pathogen. These findings are relevant to guide future infection prevention and control strategies.

Materials and methods

Microbiological procedures

A total of 37 putative R. equi strains isolated between 2007 and 2022 were included into the present study. Of these, 26 were clinical isolates from horses (n = 13), cattle (n = 3), humans (n = 7), and from goat, dog, and pig (n = 1 each). The remaining 11 isolates were opportunistic isolates cultured from elephant trunk washes performed within the frame of a tuberculosis monitoring program in a Swiss Zoo (Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, type strain ATCC 25,729, a strain isolated in 1922 from the lungs of an European horse suffering from respiratory tract infection, was included as reference [1]. The strains studied were maintained using cryobeads (AES or bioMérieux) at − 80 °C until further analyses were performed. Bacteria were routinely cultivated aerobically on Columbia agar containing 5% sheep blood (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 to 48 h. Identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) was carried out using the direct transfer-formic acid method and a Microflex LT benchtop operating system (Bruker Daltonics) [47].

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined using a commercially available microtitre plate (Sensititre RAPMYCOI AST Plate) with cation adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth w/TES (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The plate contains the following antimicrobial agents in a two-fold dilution series: amikacin (1 − 64 mg/L), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (2 − 64 mg/L amoxicillin in combination with 1 − 32 mg/L clavulanic acid), cefepime (1 − 32 mg/L), cefoxitin (4 − 128 mg/L), ceftriaxone (4 − 64 mg/L), ciprofloxacin (0.12 − 4 mg/L), clarithromycin (0.06 − 16 mg/L), doxycycline (0.12 − 16 mg/L), imipenem (2 − 64 mg/L), linezolid (1 − 32 mg/L), minocycline (1 − 8 mg/L), moxifloxacin (0.25 − 8 mg/L), tigecycline (0.015 − 4 mg/L), tobramycin (1 − 4 mg/L), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (0.25 − 8 mg/L trimethoprim in combination with 4.75 − 152 mg/L sulfamethoxazole).The microtitre plate was incubated at 35 + 2 °C, 5% CO2 for 48 h. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined for each strain and substance combination. Type strain ATCC 25,729 was used as a quality control (QC) strain. In addition, the isolates of R. equi were analysed for their MIC values to rifampicin and erythromycin using E-test strips (Biomerieux). The range of the strips used was 0.002–32 µg/ml for rifampicin and 0.016–256 µg/ml for erythromycin. The zones of inhibition showed by each of the isolates plated on Mueller-Hinton agar plates and Mueller-Hinton agar plates supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood and 20 µg/mL β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (β-NAD) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were clear and easily readable and no differences in terms of MIC values were observed. Colonies grown on supplemented Muller-Hinton agar plates were easier to read. Results were recorded as the lowest concentrations of rifampicin and erythromycin that inhibited visible growth of R. equi. Antibacterial resistance and susceptibility were assessed with respect to clinical breakpoints approved by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, VET06, 1 st ed.) if available, or other published clinical breakpoints following an established routine evaluation procedure [48].

Plasmid typing

To detect the presence of virulence plasmids and characterize the encoded virulence-associated surface protein, previously published primers for R. equi plasmids were used. These primers targeted the genes traA (common to all three virulence plasmids) [38], vapA [49], vapB [50], and vapN [37]. For isolates in which no PCR amplification of the traA gene was observed, the absence of a virulence plasmid was predicted. Sanger sequencing of the traA PCR amplicons was performed to confirm specific amplification of the gene and investigate genetic variability within the isolates of the present study. Finally, PCR results from the Swiss cohort were utilized to validate the outcome of the in silico approach applied to public genomes.

Whole genome sequencing

DNA extraction was performed on a Qiacube using the QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen). Subsequently, DNA quantity was determined using a Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher), paired-end library construction was performed using Nextera DNA Flex library kit, including Nextera CD indexes (Illumina). Sequencing was performed using a mid-output cartridge with 2 × 150 cycles on a MiniSeq instrument (Illumina). In addition, libraries of strain IMD-1031 prepared using the SQK-LSK109 kit were sequenced with MinION on a FLO-MIN106 flow cell (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). All generated data presented in this study were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under project reference number PRJNA1065651, https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1065651?reviewer=9vccetp4i7bqrev0jukj02psi0.

Genomic data Swiss cohort

Illumina sequencing data was quality-controlled using FastQC (v0.11.7, Babraham Bioinformatics). Reads were trimmed and demultiplexed using the Illumina local run software V2.0 (Illumina). Genome assemblies were created de novo using the Shovill pipeline (v1. 1.0, https://github.com/tseemann/shovill) with default setting, a minimal contig length of 500 bp and with SPAdes (v3.13.1) as assembler [51]. For strain IMD-1031, a hybrid assembly was generated from short- and long-read data using Unicycler (v0.4.8) [52], and checked for standard quality parameters using quast (v5.0.2) [53]. The complete chromosome and linear plasmid were annotated using Bakta v1.8.2 (DB: v5.0 - Light) [54], CRISPRCasFinder 4.2.20 [55], and visualized using CG View (Circular Genome Viewer) in Proksee [56].

Genomes that met al.l the following quality criteria were included in the downstream analyses: estimated mean read coverage cut-off of ≥ 30×, 5.2 Mb ± 400 kb genome assemblies, and contig count ≤ 150. Average nucleotide identity values for the newly sequences genomes were calculated using fastANI [57], whereas strains with ANI value > 94% were considered the same species [58]. Assemblies were then used to generate a species-wide core gene alignment and maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree using the R package cognac and FastTree (v2.1.10) with default parameters [59, 60] The obtained tree was visualized using iTOL [61].

Genotypic prediction of antimicrobial resistance

The identification of putative determinants conferring resistance to quinolones, erythromycin, aminoglycosides and tetracycline was performed as previously described [62]. Briefly, assembled contigs were screened for AMR-associated genes using the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) (https://github.com/arpcard/rgi) and the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) v3.1.0 [63], with a threshold for the identification of acquired genes of 90 % identity and 60 % minimum length in a RGI-standard blast output.

Phylogenetic and plasmid related analysis on a global dataset

Allelic profiles were deduced from the genome assemblies using mlst (v2.16.1; https://github.com/tseemann/mlst) and assigned to pre-defined sequence types (STs) and the conventional seven-locus MLST scheme (gapdh, tpi, mdh, icl, rpoB, recA, and adk) on PubMLST.org (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/rhodococcus-spp) [19, 64]. Additionally, we searched the US National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) for publicly available whole-genome sequences of R. equi, using names as search terms: “Rhodococcus equi [organism]”, “Rhodococcus hoagii [organism]”, and “Prescottella equi [organism]”. A total of 251 new genomes concordant with our search terms were available (Supplementary Table 2). Genomes with a genome size < 4.5 Mbp and > 6.0 Mbp were excluded from the analysis. Using the same approach as above, MLST nucleotide sequences were deduced from publicly available genomes. To understand the geographical distribution of different STs and their potential association with various hosts, we combined all available R. equi records from PubMLST (Supplementary Table 3) with publicly available genomes to construct a multiple sequence alignment using CLC Genomics Workbench (v22; Qiagen). A neighbor-joining tree was then generated from the seven concatenated allelic sequences (4017 bp) of each strain, employing 1000 bootstrap replicates with the Jukes-Cantor algorithm in CLC [64]. (Supplementary Table 3).

Plasmid sequences were downloaded from NCBI, namely pVAPA1037 (NC_011151.1), pVAPA1216 (NZ_KX443388.1), and pVAPAMBE116 (NC_014247.1) for pVAPA; pVAPB1413 (NC_014247.1), pVAPB1475 (NZ_KX443397.1), and pVAPB1593 (NC_011150.1) for pVAPB; pVAPN1204 (NZ_KX443398.1), pVAPN1571 (NZ_KF439868.1), and pVAPN2012 (NZ_KP851975.1) for pVAPN. These were used as references for average nucleotide identity (ANI) comparison (pyani; https://pypi.org/project/pyani) and determination of sequences similarity using complete genomes as input. Strains exhibiting greater than 94% similarity and over 95% coverage to any of the reference sequences were considered to harbour the corresponding plasmid. For the remaining sequences, the absence of the plasmid was inferred. Finally, in order to confirm the associations between phylogenetic distribution, plasmid occurrence and type, and host preferences, publicly available whole genome sequences including newly sequenced isolates were compared and used to generate a phylogeny. Core-genome MLST (cgMLST) analysis for 286 R. equi genomes was performed in Ridom Seqsphere+ (v9.0.1; Ridom GmbH, Münster, Germany). The finished and publicly available genome of R. equi 103 S (NC_014659.1) was selected as the “seed genome” for the cgMLST scheme definition. Using the cgMLST Target Definer tool with default parameters of the Ridom SeqSphere + software, a rapid local ad hoc cgMLST scheme containing 2737 genes was defined, including all genes of the reference genome that were not homologous, did not contain internal stop codons, and did not overlap other genes. Only genomes that presented ≥ 90% of all query targets from the ad hoc scheme were accepted for cgMLST analysis. A cgMLST matrix was generated with the option “ignore missing values”, thereafter the matrix was converted to a neighbor-joining phylogeny using the “NJ” command in the R package ape [65]. The cgMLST phylogeny was rooted at the mid-point and visualized using iTOL (v5) [61]. Finally, the distributions of the different types of plasmids and the source of isolation were compared using contingency tables and 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test. The threshold for statistical significance was P <.05 (GraphPad Prism v10.0.0).

Results

A total of 37 Rhodococcus sp. isolates of human and animal origin isolated in Switzerland between 2007 and 2022 were included in the present study (Supplementary Table 1). Of these, 26 were from clinical samples of human and animal patients. 30% (8/26) of the clinical isolates originated from abscesses from different body localization. Finally, all four bovine and porcine isolates were retrieved from lymph nodes, whereas over a half of the equine isolates (54%; 7/13) were cultured from the lower respiratory tract. Out of the 37 isolates included in the present study, 35 were confirmed to be R. equi based on MALDI-TOF MS log scores values (LSV) between 2.0 and 3.0. For the remaining two isolates (2510-52 and 3808-53), both of human origin, LSV scores below 1.8 were observed. Nevertheless, MALDI-TOF MS allowed clear species identification.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

To complement our genomic analyses, we performed AST to determine the MICs for 17 antimicrobial agents for all R. equi isolates. The obtained MIC values are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. A narrow MIC distribution that included only three dilution steps was seen for tigecycline 0.25–1 mg/L, linezolid 2–8 mg/L, and moxifloxacin 0.5–2 mg/L. Four dilution steps were seen for cefoxitin 8–64 mg/L, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 8–64 mg/L, and ciprofloxacin 1–8 mg/L. Other antimicrobial agents showed a rather broad MIC distribution such as for rifampicin (0.094–1 mg/L) which included 8 dilution steps. The lowest overall MICs were seen for clarithromycin (≤ 0.03–1 mg/L) and tigecycline (0.25–1 mg/L), and also for rifampicin in 28/35 isolates (0.094–0.5 mg/L). Based on the CLSI breakpoints for clarithromycin, trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole, rifampicin, and erythromycin, the Swiss isolates were pansusceptible, except for 32 isolates (91.4%) which exhibited MIC values ≥ 4/76 mg/L for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (see Supplementary Table 4).

Whole-genome sequencing

We sequenced the genomes of 37 Rhodococcus sp. isolated from human and animal patients, as well as from elephant trunk washes and the avirulent type strain ATCC 25,729, isolated from the lung abscess of a foal (Supplementary Table 1). The mean assembly length was 5 261 898 bp, with a mean read coverage of 82.8-fold, ranging from 37.9- to 113.3-fold. The mean G + C content was 68.74 mol%, ranging from 68.58 to 68.84 mol% (Supplementary Table 1). The average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis based on the whole genome confirmed that 35 isolates newly sequenced in this study belonged to R. equi, confirming the MALDI-TOF MS results. The remaining two isolates, showing ANI values below 94%, potentially represent two novel Rhodococcus sp. according to the TYGS genome-based taxonomy platform [66].

Plasmid typing - Swiss cohort

The traA gene, indicative of the presence of virulence-associated plasmids was detected in 60% of the R. equi isolates (21/35). Among the clinical isolates (n = 24), 87.5% (21/24) carried the traA gene of which 50% (12/24) were positive for vapA, 29% (7/24) for vapN, and two isolates for vapB (8%;2/24) as displayed in the species-wide core gene maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree in Fig. 1. Three clinical isolates lacked traA and originated from a human patient, a dog and a horse. Also, none of the opportunistically obtained isolates from elephants carried virulence-associated plasmids.

Fig. 1.

Whole-genome phylogeny of sequenced Swiss Rhodococcus equi isolates. A core genome alignment and maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree were constructed with R package cognac using concatenated gene alignments of sequences listed in Supplementary Table S1. Sequence types (STs) were mapped onto the tips and plasmid types (A = pVAPA, B = pVAPB, and N = pVAPN) highlighted with color bars. Reference strain 103 S (ST-3) was included, along with Rhodococcus sp. strain 2510-52, which served as the outgroup for tree rooting. The symbols (goat, human, cattle, horse, pig) represent the host species from which the isolates were cultured. Scale bar indicates substitutions per site

A BLAST search of the sequences from pVAPA, pVAPB and pVAPN revealed a similar plasmid backbone, in particular for pVAPA pVAPB, whereas pVAPNs were more diverse. Overall, the similarity among plasmid sequences from Swiss clinical isolates and the three references chosen was high. Sequences of pVAPA showed the highest similarity (M = 99.55%, SD = 0.27), followed by pVAPB (M = 99.19%, SD = 0. 79), and pVAPN with the lowest similarity (M = 95.68%, SD = 1.95) (Supplementary Fig. 1A-C and Supplementary Table 6).

Genotypic prediction of antimicrobial resistance

We next screened the whole-genome sequences to detect genes associated with resistance, such as chromosomally encoded antibiotic-resistance-conferring modifications and resistance genes located on plasmids (Supplementary Table 5). No antibiotic resistance-associated genes were found in the 35 genomes of R. equi. In strain 3808-53, a putative novel Rhodococcus species, the complete vanO operon comprising the vanH, vanO, vanX, vanS, and vanR genes encoding resistance to glycopeptides such as vancomycin was detected. The five genes are identical (100% identity,100% coverage) to previously reported genes present in publicly available databases (CARD).

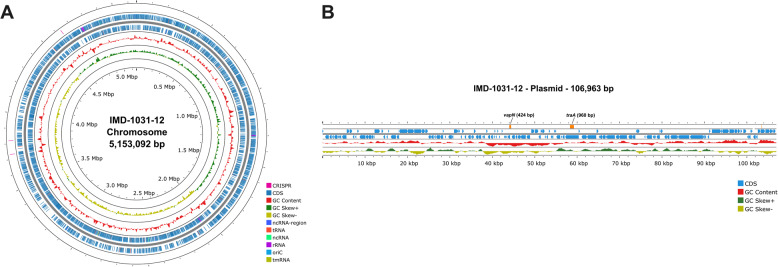

Complete genome assembly of R. equi IMD-1031-12

The pVAPN plasmids exhibit greater heterogeneity compared to pVAPA and pVAPB. To confirm the linearity of pVAPN within the Swiss cohort and to further characterize the genomic features of this plasmid type, we sequenced the complete genome of R. equi IMD-1031-12 using Oxford Nanopore. The hybrid assembly obtained consists of one 5,153,092 bp circular chromosome and one 106,963 bp linear plasmid with 68.77% and 65.69% GC content, respectively (Fig. 2). The plasmid exhibited 95.53% identity to R. equi strain PAM1571 plasmid (NZ_KF439868.1). Rhodococcus equi IMD-1031-12 contains 4,748 coding sequence (CDS) genes consisting of 4,365 functional genes and 470 genes encoding hypothetical proteins. Additionally, 12 genes encoding rRNA and 52 genes encoding tRNA were found and summarized in Table 1. For R. equi IMD-1031-12 plasmid, there are 129 CDS genes consisting of 51 functional genes and 78 genes encoding hypothetical proteins (Table 1). Finally, the genes used to identify virulence plasmids (traA) and to characterize the pVAPN type (vapN) were found to be approximately 13 thousand bases apart (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Complete genome of Rhodococcus equi IMD-1031-12 (A) Map of 5,153,092 bp chromosome (B) Map of 106,963 bp linear plasmid. The localization and size of the target genes traA and vapN for plasmid detection and characterisation, respectively, are highlighted in orange. Coding sequences (CDS) are displayed in blue, GC content in red, and three clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) highlighted in pink in the outer ring (A) were identified using CRISPR/Cas Finder-v1.1.0 in Proksee [55, 56]. Positive and negative GC skews are shown in dark green and yellow, respectively

Table 1.

Genomic characteristics of Rhodococcus equi IMD-1031-12

| Features | Chromosome | Plasmid |

|---|---|---|

| Length (bp) | 5,153,092 | 106,963 |

| GC content (%) | 68.77 | 65.69 |

| Coding sequences (CDS) | 4,748 | 129 |

| Functional proteins (genes) | 4365 | 51 |

| Hypothetical protein (genes) | 470 | 78 |

| tRNA | 52 | - |

| tmRNA | 1 | - |

| rRNA | 12 | - |

| ncRNA | 5 | - |

| ncRNA Regions | 16 | - |

| oriC | 1 | - |

| CRISPR/Cas | 3 | - |

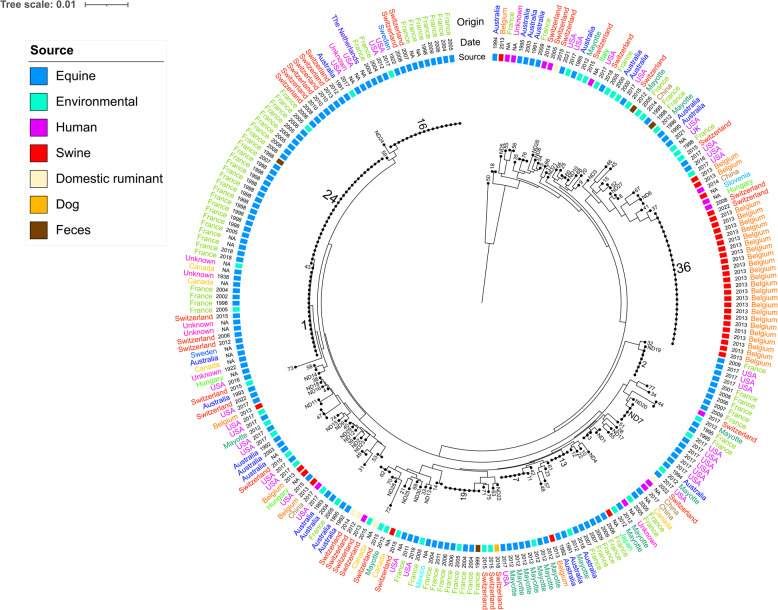

Multi-locus sequence typing

Multi-locus STs were extracted from all 35 assemblies classified as R. equi and revealed a heterogenous population for the Swiss cohort. A total of 21 unique STs were assigned to 34 sequenced strains, including 16 novel STs (ST-62 to ST-77), which have been added to the existing database in PubMLST.org. For one remaining sample, an ST could not be determined because one or more loci were missing or incomplete. The most common MLST types from this collection of R. equi isolates were ST-24 (n = 6) and ST-1 (n = 3), whereas the most common clonal complex (CC) was CC-1 (encompassing ST-1 and ST-24; n = 9). Horse isolates belonged to ST-1, ST-16, ST-24, ST-58, and ST-64. The latter (ST-64) was a novel ST reported for the first time and the isolates lacked virulence plasmids (Fig. 1). Isolates classified as novel ST-62, ST-65, and ST-76 all harbored the pVAPN plasmid. Notably, ST-62 and ST-76 included isolates from diverse sources; ST-62 encompassed isolates from humans, goats, and cattle, while ST-76 comprised isolates exclusively from humans and cattle. To comprehend the geographic spread of distinct STs and explore possible connections between STs and various hosts, a total of 241 sequences originating from 16 countries were retrieved. We employed all accessible data on R. equi from PubMLST (n = 141) and publicly available genomes (n = 65) representing a global dataset (Supplementary Table 3). The global sequences revealed a heterogenous population with a total of 102 unique ST, including 30 novel STs. This data was used to generate a neighbor-joining tree based on concatenated MLST nucleotide sequences (Fig. 3). Over a half of the isolates derived from horses and ponies (n = 135; 56%), followed by environmental (n = 48; 19.9%), porcine (n = 35; 14.5%), human (n = 14; 5.8%), and faecal origin (n = 4; 1.7%). A total of 72 unique ST, including the newly described profiles reported from Swiss isolates, are currently present in PubMLST, moreover, 30 novel STs were identified from publicly available R. equi genomes. Host tropism was evident among CCs, with certain complexes, such as CC-1, CC-2, CC-4, and CC-8, being associated primarily with equine hosts. Environmental isolates linked to these CCs were notably limited in number. CC-6 was associated with porcine and human isolates. ST-1, ST-2, and ST-16 have been identified as predominant STs among equine patients, exhibiting a global occurrence across various countries such as Australia, France, Switzerland, Mayotte, Hungary, the USA, and Canada. Interestingly, ST-24, another equine associated ST, was reported in France and Switzerland only. Rhodococcus equi isolates from both porcine and human sources, reported in various countries such as France, Belgium, Switzerland, Hungary, China, and Slovenia, shared the same STs, including ST-18 and particularly ST-36. The latter STs were found to harbour VAPB plasmids according to PubMLST records or upon testing the Swiss isolates.

Fig. 3.

Population structure of 225 Rhodococcus equi isolates based on an alignment constructed from concatenated multi-locus sequences (MLST). Sequence Types (ST)s are mapped onto the tips of the tree, the source and country of origin of the isolates are colour-coded in the inner and outer rings, respectively. The date of isolation is displayed between the source and the country of origin of the isolates. The tree was mid-point rooted and the scale bar is expressed as the average number of nucleotide substitutions per site. NA, not available

Whole-genome analysis

A total of 251 additional genomes concordant with our search terms were available from public repositories (Supplementary Table 2). The global distribution of the sequences can be found at https://jsfiddle.net/gorza89/92vougkj. Whole genome sequences from 18 countries obtained from various hosts and locations were included in the global dataset. The USA was the most represented country with 197 sequences, followed by Switzerland and China with 35 and 8 respectively. Genomes obtained from environmental isolates were predominant with 121 sequences, followed by equine and human with 95 and 23 respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Bar chart indicating the source of isolation of the whole genome sequences included in the present study and obtained from public repositories

Overall, the similarity among plasmid sequences from global isolates was lower compared to the Swiss cohort, although the Swiss pVAPN isolates also belong to different STs (Supplementary Table 6). Sequences identified as pVAPA showed the highest similarity compared the three reference sequences (M = 99.08%, SD = 1.89), followed by pVAPN for which the mean similarity observed was slightly higher compared to the sequences from Swiss isolates (M = 97.06%, SD = 2.56). The pVAPB sequences, however, showed lower similarity (M = 96.85%, SD = 2.71) (Supplementary Table 6).

The characterization of plasmid sequences among publicly available R. equi whole genome sequences revealed distinct patterns of virulence-associated plasmids prevalence among different sources. Equine isolates exhibited a dominant presence of pVAPA (78%), while human derived R. equi displayed significant proportions of pVAPB (26%) and pVAPN (52%) (Fig. 5). The environmental isolates exhibited a diverse distribution, with pVAPA detected in 48%, one pVAPB and pVAPN respectively (0.8% each), and absence of plasmid sequences in the remaining 50% (Fig. 5). A total of 45% of the ruminant isolates carried sequences with pVAPN, whereas the remaining isolates were plasmidless. In porcine isolates, pVAPB sequences accounted for 20% of the observed plasmid distribution. Human, ruminant, and porcine isolates were characterized by the absence of pVAPA. Differences in plasmid category distribution between groups are statistically significant (P <.001). Specific plasmid categories are associated with particular host species and in particular pVAPA is unlikely to be found in non-equine associated isolates. pVAPA was detected exclusively in equine and environmental sequences, pVAPN in sequences from human, environmental and ruminant isolates, and pVAPB was observed in isolates from all sources except from equine and ruminant isolates. Surprisingly, equal numbers of plasmidless and pVAPA positive sequences from environmental isolates were observed. Owing to the limited number of sequence data obtained from ruminants and pigs, meaningful statistical comparisons could not be conducted.

Fig. 5.

Stacked bar chart illustrating the distribution of various plasmid categories based on the origin of the Rhodococcus equi isolates

A total of 55 publicly available genomes, including 52 genomes from the USA, 2 from China, and one with unknown origin (highlighted in orange in Suppl. Table 2), did not meet the inclusion criteria for the cgMLST analysis and were excluded from the phylogenetic analysis. The inclusion of 233 whole genome sequences from 18 countries obtained from various hosts and locations provides an overview of the genetic diversity of R. equi both at a global and local level. The ST-derived phylogeny was congruent with the cgMLST phylogeny. Notably, ST-1 and ST-16, highlighted in red and dark pink in Fig. 6, comprised 10 and 21 genomes, respectively. These strains were isolated over an extended period, with the oldest isolate being the type strain NCTC1621T from 1922 and the most recent from 2017. They exhibit a global distribution, with isolates from the USA, Canada, Australia, Hungary, the Netherlands, France, Sweden and Switzerland. The majority of the strains were derived from equine samples and carried the VAPA plasmid. The only exceptions were four strains, including type strains DSM 20,295T (= ATCC 7005T = NCTC 10673T) and DSM 20,307T (= ATCC 6939T = NCTC 1621 = NBRC101255T = C7T). The origin history of DSM 20,295T is not well-documented, while the plasmid in DSM 20,307T has likely been lost during passaging over time [67]. No other plasmid types were observed in these two clades.

Fig. 6.

Population structure of the global Rhodococcus equi dataset including 233 genomes from 18 countries. Tree constructed using ad hoc core-genome MLST (cgMLST) scheme containing 2’737 genes generated in Ridom Seqsphere + v9.0.1 (https://www.ridom.de/seqsphere/cgmlst/) and converted to a neighbor-joining phylogeny using the R package ape [65]. The cgMLST phylogeny was rooted at the mid-point and visualized using iTOL [61]. The year and country of isolation are shown in the inner and second ring from the centre respectively. Source attribution of the different isolates is shown in the third ring. Presence/absence of the virulence-associated plasmid and the various plasmid categories are color-coded in the outer ring. The scale bar expresses the average number of nucleotide substitutions per site

Another cluster observed in the cgMLST tree, highlighted in yellow (Fig. 6), includes five genomes isolated from human (n = 3) and porcine (n = 2) samples from various countries, such as Slovenia, Hungary, China, and Switzerland. All strains belonged to ST-36 and either contained the pVAPB plasmid or were plasmid-free. Of particular interest is a clade of genetically distinct isolates from Switzerland, belonging to the newly described ST-62, ST-65, and ST-76, and highlighted in light green (Fig. 6). These isolates were collected over a considerable period (2005–2022), from diverse clinical samples, including humans (n = 3), cattle (n = 3), and one goat. All isolates contained the pVAPN plasmid type.

Finally, two large clades from the USA were more phylogeographically restricted. The first major clade is composed of 61 equine and environmental sequences obtained from isolates cultured between 2002 and 2021 and corresponds to the clonal population 2287 first identified by Álvarez-Narváez and colleagues (Fig. 6) [68]. Except for two sequences from Ireland, the remaining sequences originated from different regions within USA, including Florida, Kentucky, New York, and Texas. Of these, pVAPA was identified in 58 out of 61 sequences, whereas in the remaining three sequences, no plasmids were detected. The resulting structure confirms the persistent presence of this equine pathogen for nearly two decades, spanning a wide geographic area. It appears to be endemic within the equine population and horse-related environments in several US states and, more recently, in Ireland. A second clade, consisting of 31 sequences from horse-related environmental isolates exclusively originating from USA (Kentucky), was identified and corresponds to the clonal population 2017 first described by Huber et al. [69]. Five of these isolates, all of which were obtained in 2017, carried the pVAPA plasmid. Finally, a third clade, comprising 10 genomes predominantly sourced from equine isolates (8 equine and 2 environmental), demonstrates a unique geographic distribution. The earliest sequence, dated 1997, originates from the Netherlands, while the most recent, dating back to 2017, was obtained from the United States. In addition to these geographical regions, France and Switzerland are also represented in this clade, each with two isolates. In half of these sequences, pVAPA was found. For the remaining sequences, and particularly those containing the two plasmids pVAPB and pVAPN, a higher genomic diversity was observed. Although some sequences with these plasmids were grouped together in the phylogenetic tree, their genetic distance is evident (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Rhodococcus equi emerged as a major pathogen affecting horses and other animals, such as ruminants and pigs, as well as humans with a compromised immune system [14]. This study investigated the genomic characteristics, plasmid-type occurrence, and antibiotic resistance of 35 R. equi strains through whole-genome sequence analysis and comparative genomics. Additionally, the results of the present study suggest that MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry might hold promise as a future diagnostic tool for direct and rapid identification of clinical and environmental R. equi isolates in accordance with previous experiences using similar MALDI instruments [70, 71].

A narrow MIC distribution that included only three or four dilution steps was seen for most antimicrobial agents tested, suggesting clinical susceptibility to the latter. Although a rather broad MIC distribution was observed for rifampicin (0.094–1 mg/L) and erythromycin (0.19–2 mg/L) the isolates were interpreted as susceptible to these clinically important antimicrobials according to the CLSI guidelines. It has to be mentioned that Etest have been described to underestimate MICs for erythromycin relative to broth microdilution and this represent a limitation of our susceptibility testing methodology [72]. However, genes associated with resistance to erythromycin and other clinically relevant antimicrobials were not detected at genomic level. Interestingly, a glycopeptide resistance operon with a unique structure, reported as vanO and first described in the genus Rhodococcus [73] was detected in strain 3808-53. Genome-based classification using the TYGS taxonomy platform suggested that strain 3808-53 possibly represent a novel species, thereby clarifying the MALDI-TOF results. The strain was isolated from an abscess of a human patient and these findings have potential implications in clinical practice, since glycopeptides such as vancomycin are used for therapy of nosocomial infections caused by this Gram-positive species [73].

Historically, molecular epidemiological studies on R. equi primarily focused on the genetic diversity of pVAP using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) [74, 75]. Furthermore, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) has been employed to evaluate the genomic diversity of R. equi isolates [20]. However, it is noteworthy that environmental avirulent strains found in soil were often not considered in these analyses [19]. This omission is significant, given the potential for the conjugal transfer of a virulent plasmid from a virulent to an avirulent R. equi strain [76]. A MLST scheme, which is proposed to be an accurate and more accessible alternative for R. equi genotyping has been introduced [19]. In their study, Duquesne and colleagues observed that the same host species could harbour different STs, indicating genetic diversity among R. equi strains within host populations. In contrast, there were no shared STs identified between equine and porcine R. equi strains when taking into account allele microvariability. Intriguingly, our findings highlight the peculiar geographical and host-related distribution of equine-derived isolates. These strains, characterized by ST-1, ST-16, ST-24, and ST-58, were not found in other hosts, suggesting a possible host specificity of certain R. equi lineages based on chromosomal traits in addition to the well-known host tropism derived by virulence plasmids [19, 48]. This observation refines our understanding of the bacterium’s ecology and aids in tailoring targeted preventive measures, especially in equine populations.

Currently, there is a need for a consensus genotyping tool that provides accurate genetic classification of Rhodococcus spp. and MLST is a simple and promising technique [20]. In order to obtain a global representative dataset that will be valuable for monitoring the spread of virulent or antimicrobial resistant strains, however, it is crucial that MLST profiles are submitted to PubMLST. Although currently more accessible, MLST has been proven to be less accurate than WGS for clonal populations [20]. Therefore, we decided to extend our investigation using publicly available whole genome sequences. Similarly to MLST data and although globally distributed, WGS data for R. equi is only available from limited countries and there are no data from Africa and South America.

It is clear that the distribution of virulence-associated plasmid types is host-driven, as they are associated with specific hosts [32]. Contrary to previous observations, in our global dataset, a substantial proportion of sequences derived from environmental sources exhibited the presence of pVAPA. The elevated number of environmental isolates carrying pVAPA observed in the global dataset of whole genomes included in the present study is most likely the result of the type of sampling performed in previous studies. Frequently, sampling in horse breeding farms encompasses the collection of environmental samples, wherein virulent R. equi recently shed through feces is gathered, thus being considered ubiquitous [36, 74]. Conversely, the absence of pVAP from clinical isolates might be the result of a plasmid loss during isolation [77]. The precise number of passages required to lose the plasmid is yet to be investigated and is likely depended on various factors such as the culturing medium, bacterial load, and concurrent growth of different bacterial species.

Recent evidence supports the hypothesis that the ingestion of undercooked meat products might be a possible source of R. equi infection in humans [40, 78]. The examination of virulence-plasmid profiles in 164 R. equi isolates obtained from the lymph nodes of Hungarian pigs revealed the presence of pVAPB in 26.8% [79]. Furthermore, the serological analysis of 69 human isolates in Thailand, where 75% carried pVAPB, exhibited similar serotypes to those observed in Hungary [80]. A similar scenario has been observed in R. equi isolates derived from bovine samples and concerning the detection of pVAPN. Ribeiro and colleagues, in Brazil, isolated R. equi from 31 out of 100 lymphadenitis samples obtained from slaughtered cattle, with 13 isolates (41.9%) containing the vapN gene [33]. Concurrently, pVAPN was detected in 43% (16 out of 37) from a panel of 65 R. equi isolates collected from human patients globally between 1984 and 2002 [37]. The introduction of more discriminative typing techniques is enhancing the precision of genomic characterization for the involved strains, shedding light on their potential epidemiological connections. In the present study, isolates harbouring pVAPN plasmids and originating from different sources, namely human patients and ruminants including cattle and goats, shared identical STs, such as ST-62 and ST-76. These findings were confirmed by WGS, however, due to the low number of isolates and the considerable temporal span (2005–2022), a clear cluster potentially suggesting a common infection source could not be demonstrated and should be further investigated. A similar pattern was observed for the two isolates harbouring pVAPB plasmids and isolated from a Swiss human patient and the lymph node of a pig, both isolates were classified as ST-36. The likelihood of direct transmission appears low, given that these isolates were obtained at different time points during the study, with a 14-year gap between them. A total of 23 porcine isolates carrying the pVAPB and classified as ST-36, however, were also reported from 23 different farms investigated in Belgium, suggesting that this particular ST is well adapted in farmed pigs and potentially zoonotic [19]. A comparable clustering of pVAPB-harboring strains using whole-genome sequencing (WGS) could not be identified, as a smaller number of isolates were found to carry this plasmid type in the global dataset. In conclusion, the complex interplay between specific R. equi lineages, host adaptation, virulence-associated plasmids and their occurrence, and environmental persistence are far to be completely understood and will need further investigations.

Conclusion

Our investigation reports a novel aspect of the R. equi genome biology and ability to cause disease in various hosts. Using a genomic approach we report host-specific strains that serve as carriers of virulence-associated plasmids, indicating an adaptation strategy within distinct R. equi lineages. The existence of shared plasmid profiles between farm animals and humans suggests a common infection source. This observation carries implications for both veterinary and public health, urging a holistic approach to prevent infections in animals and humans.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ella Hübschke, Fenja Rademacher, and Ute Friedel for excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- R. equi

Rhodococcus equi

- HIV

Immunodeficiency virus

- AIDS

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- MLST

Multi-locus sequence typing

- WGS

Whole-genome sequencing

- AMR

Antimicrobial resistance

- pVAP

Virulence-associated plasmids

- Vaps

Virulence-associated proteins

- PAI

Pathogenicity islands

- MIC

Minimal inhibitory concentration

- WHO

World Health Organization

- MALDI-TOF MS

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry

- LSV

Log scores values

- CARD

Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database

Author contributions

GG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MJAS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. SS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SK: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. NC: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MB: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. BS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. PMK: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. RS: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors did not receive any specific grant for this work from any funding agency.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories under project reference number PRJNA1065651, https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1065651?reviewer=9vccetp4i7bqrev0jukj02psi0.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All clinical samples and data were collected during routine patient care. No personal information, photos, or images are contained in the study. The data have been anonymized, enabling analysis in accordance with Swiss law and ethical regulations. Under the Human Research Act and the Swiss Animal Welfare Act, no ethical approval or patient consent is required for quality-focused assessments of clinical samples.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Magnusson H. Spezifische infektiöse pneumonie beim fohlen: Ein Neuer eitererreger beim Pferde. Arch Wiss Prakt Tierheilkd. 1923;50:22–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith BP, Robinson RC. Studies of an outbreak of Corynebacterium equi pneumonia in foals. Equine Vet J. 1981;13(4):223–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones AL, Sutcliffe IC, Goodfellow M. Prescottia equi gen. Nov., comb. Nov.: a new home for an old pathogen. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2013;103(3):655–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sangal V, Goodfellow M, Jones AL, Sutcliffe IC. A stable home for an equine pathogen: valid publication of the binomial Prescottella equi gen. Nov., comb. Nov., and reclassification of four rhodococcal species into the genus Prescottella. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2022;72(9). 10.1099/ijsem.0.005551. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Sangal V, Jones AL, Goodfellow M, Sutcliffe IC, Hoskisson PA. Comparative genomic analyses reveal a lack of a substantial signature of host adaptation in Rhodococcus equi (‘Prescottella equi’). Pathog Dis. 2014;71(3):352–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Val-Calvo J, Vazquez-Boland JA. Mycobacteriales taxonomy using network analysis-aided, context-uniform phylogenomic approach for non-subjective genus demarcation. mBio. 2023;14(5):e0220723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muscatello G, Leadon DP, Klay M, Ocampo-Sosa A, Lewis DA, Fogarty U, et al. Rhodococcus equi infection in foals: the science of ‘rattles’. Equine Vet J. 2007;39(5):470–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giguere S, Cohen ND, Chaffin MK, Hines SA, Hondalus MK, Prescott JF, et al. Rhodococcus equi: clinical manifestations, virulence, and immunity. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25(6):1221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giles C, Vanniasinkam T, Ndi S, Barton MD. Rhodococcus equi (Prescottella equi) vaccines; the future of vaccine development. Equine Vet J. 2015;47(5):510–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vazquez-Boland JA, Giguere S, Hapeshi A, MacArthur I, Anastasi E, Valero-Rello A. Rhodococcus equi: the many facets of a pathogenic actinomycete. Vet Microbiol. 2013;167(1–2):9–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golub B, Falk G, Spink WW. Lung abscess due to Corynebacterium equi - Report of first human infection. Ann Intern Med. 1967;66(6):1174–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanetta LL, Filice GA, Ferguson RM, Gerding DN. Corynebacterium equi: a review of 12 cases of human infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5(6):1012–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drancourt M, Bonnet E, Gallais H, Peloux Y, Raoult D. Rhodococcus equi infection in patients with aids. J Infect. 1992;24(2):123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey RL, Sunstrum JC. Rhodococcus equi infection in patients with and without human-immunodeficiency-virus infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(1):139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsueh PR, Hung CC, Teng LJ, Yu MC, Chen YC, Wang HK, et al. Report of invasive Rhodococcus equi infections in taiwan, with an emphasis on the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(2):370–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lasky JA, Pulkingham N, Powers MA, Durack DT. Rhodococcus equi causing human pulmonary infection - Review of 29 cases. South Med J. 1991;84(10):1217–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donisi A, Suardi MG, Casari S, Longo M, Cadeo GP, Carosi G. Rhodococcus equi infection in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1996;10(4):359–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li N, Wu C, Cao P, Chen D, Chen F, Shen X. Multiple systemic infections caused by Rhodococcus equi: a case report. Access Microbiol. 2024;6(2). 10.1099/acmi.0.000600.v4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Duquesne F, Houssin E, Sevin C, Duytschaever L, Tapprest J, Fretin D, et al. Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for Rhodococcus equi. Vet Microbiol. 2017;210:64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarez-Narvaez S, Logue CM, Barbieri NL, Berghaus LJ, Giguere S, Comparing PFGE. MLST, and WGS in monitoring the spread of macrolide and Rifampin resistant Rhodococcus equi in horse production. Vet Microbiol. 2020;242:108571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song Y, Xu XM, Huang ZZ, Xiao Y, Yu KY, Jiang MN et al. Genomic characteristics and pan-genome analysis of Rhodococcus equi. Front Cell Infect Mi. 2022;12. 10.3389/fcimb.2022.884441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Ying J, Ye J, Xu T, Wang Q, Bao Q, Li A. Comparative genomic analysis of Rhodococcus equi: an insight into genomic diversity and genome evolution. Int J Genomics. 2019;2019:8987436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Letek M, Ocampo-Sosa AA, Sanders M, Fogarty U, Buckley T, Leadon DP, et al. Evolution of the Rhodococcus equi vap pathogenicity Island seen through comparison of host-associated VapA and VapB virulence plasmids. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(17):5797–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takai S, Anzai T, Fujita Y, Akita O, Shoda M, Tsubaki S, et al. Pathogenicity of Rhodococcus equi expressing a virulence-associated 20 kda protein (VapB) in foals. Vet Microbiol. 2000;76(1):71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valero-Rello A, Hapeshi A, Anastasi E, Alvarez S, Scortti M, Meijer WG, et al. An invertron-like linear plasmid mediates intracellular survival and virulence in bovine isolates of Rhodococcus equi. Infect Immun. 2015;83(7):2725–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giguere S, Hondalus MK, Yager JA, Darrah P, Mosser DM, Prescott JF. Role of the 85-kilobase plasmid and plasmid-encoded virulence-associated protein A in intracellular survival and virulence of Rhodococcus equi. Infect Immun. 1999;67(7):3548–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hondalus MK, Mosser DM. Survival and replication of Rhodococcus equi in macrophages. Infect Immun. 1994;62(10):4167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coulson GB, Miranda-CasoLuengo AA, Miranda-CasoLuengo R, Wang XG, Oliver J, Willingham-Lane JM, et al. Transcriptome reprogramming by plasmid-encoded transcriptional regulators is required for host niche adaption of a macrophage pathogen. Infect Immun. 2015;83(8):3137–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain S, Bloom BR, Hondalus MK. Deletion of VapA encoding virulence associated protein A attenuates the intracellular actinomycete Rhodococcus equi. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50(1):115–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright LM, Carpinone EM, Bennett TL, Hondalus MK, Starai VJ. VapA of Rhodococcus equi binds phosphatidic acid. Mol Microbiol. 2018;107(3):428–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takai S, Koike K, Ohbushi S, Izumi C, Tsubaki S. Identification of 15- to 17-kilodalton antigens associated with virulent Rhodococcus equi. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(3):439–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacArthur I, Anastasi E, Alvarez S, Scortti M, Vazquez-Boland JA. Comparative genomics of Rhodococcus equi virulence plasmids indicates host-driven evolution of the vap pathogenicity Island. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9(5):1241–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ribeiro MG, Lara GHB, da Silva P, Franco MMJ, de Mattos-Guaraldi AL, de Vargas APC, et al. Novel bovine-associated pVAPN plasmid type in Rhodococcus equi identified from lymph nodes of slaughtered cattle and lungs of people living with HIV/AIDS. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65(2):321–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sekizaki T, Takai S, Egawa Y, Ikeda T, Ito H, Tsubaki S. Sequence of the Rhodococcus equi gene encoding the virulence-associated 15-17-kDa antigens. Gene. 1995;155(1):135–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takai S, Imai Y, Fukunaga N, Uchida Y, Kamisawa K, Sasaki Y, et al. Identification of virulence-associated antigens and plasmids in Rhodococcus equi from patients with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1995;172(5):1306–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venner M, Meyer-Hamme B, Verspohl J, Hatori F, Shimizu N, Sasaki Y, et al. Genotypic characterization of VapA positive Rhodococcus equi in foals with pulmonary affection and their soil environment on a warmblood horse breeding farm in Germany. Res Vet Sci. 2007;83(3):311–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bryan LK, Alexander ER, Lawhon SD, Cohen ND. Detection of VapN in Rhodococcus equi isolates cultured from humans. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0190829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ocampo-Sosa AA, Lewis DA, Navas J, Quigley F, Callejo R, Scortti M, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Rhodococcus equi based on traA, vapA, and VapB virulence plasmid markers. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(5):763–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakai M, Ohno R, Higuchi C, Sudo M, Suzuki K, Sato H, et al. Isolation of Rhodococcus equi from wild boars (Sus scrofa) in Japan. J Wildl Dis. 2012;48(3):815–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witkowski L, Rzewuska M, Takai S, Kizerwetter-Swida M, Kita J. Molecular epidemiology of Rhodococcus equi in slaughtered swine, cattle and horses in Poland. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16. 10.1186/s12866-016-0712-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Alvarez-Narvaez S, Huber L, Giguere S, Hart KA, Berghaus RD, Sanchez S, et al. Epidemiology and molecular basis of multidrug resistance in Rhodococcus equi. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2021;85(2):e00011-21. 10.1128/MMBR.00011-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Val-Calvo J, Darcy J, Gibbons J, Creighton A, Egan C, Buckley T, et al. International spread of multidrug-resistant Rhodococcus equi. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28(9):1899–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin WV, Kruse RL, Yang K, Musher DM. Diagnosis and management of pulmonary infection due to Rhodococcus equi. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(3):310–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.WHO. Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine: 6th revision. Switzerland: Geneva; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morley PS, Apley MD, Besser TE, Burney DP, Fedorka-Cray PJ, Papich MG, et al. Antimicrobial drug use in veterinary medicine. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19(4):617–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Narvaez SA, Fernandez I, Patel NV, Sanchez S. Novel quantitative PCR for Rhodococcus equi and macrolide resistance detection in equine respiratory samples. Anim (Basel). 2022;12(9). 10.3390/ani12091172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Schulthess B, Bloemberg GV, Zbinden R, Bottger EC, Hombach M. Evaluation of the Bruker MALDI biotyper for identification of Gram-positive rods: development of a diagnostic algorithm for the clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(4):1089–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petry S, Sevin C, Kozak S, Foucher N, Laugier C, Linster M, et al. Relationship between rifampicin resistance and RpoB substitutions of Rhodococcus equi strains isolated in France. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;23:137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takai S, Vigo G, Ikushima H, Higuchi T, Hagiwara S, Hashikura S, et al. Detection of virulent Rhodococcus equi in tracheal aspirate samples by polymerase chain reaction for rapid diagnosis of R. equi pneumonia in foals. Vet Microbiol. 1998;61(1–2):59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oldfield C, Bonella H, Renwick L, Dodson HI, Alderson G, Goodfellow M. Rapid determination of vapa/vapb genotype in Rhodococcus equi using a differential polymerase chain reaction method. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2004;85(4):317–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE, Unicycler. Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(6):e1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(8):1072–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwengers O, Jelonek L, Dieckmann MA, Beyvers S, Blom J, Goesmann A. Bakta: rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification. Microb Genom. 2021;7(11). 10.1099/mgen.0.000685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Couvin D, Bernheim A, Toffano-Nioche C, Touchon M, Michalik J, Neron B, et al. CRISPRCasFinder, an update of crisrfinder, includes a portable version, enhanced performance and integrates search for Cas proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W246–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grant JR, Enns E, Marinier E, Mandal A, Herman EK, Chen CY, et al. Proksee: in-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(W1):W484–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jain C, Rodriguez RL, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee I, Kim YO, Park SC, Chun J. OrthoANI: an improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:1100–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crawford RD, Snitkin ES. Cognac: rapid generation of concatenated gene alignments for phylogenetic inference from large, bacterial whole genome sequencing datasets. BMC Bioinformatics. 2021;22(1):70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26(7):1641–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(W1):W293–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghielmetti G, Seth-Smith HMB, Roloff T, Cernela N, Biggel M, Stephan R et al. Whole-genome-based characterization of Campylobacter jejuni from human patients with gastroenteritis collected over an 18 year period reveals increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance. Microb Genom. 2023;9(2). 10.1099/mgen.0.000941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Jia B, Raphenya AR, Alcock B, Waglechner N, Guo P, Tsang KK, et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D566–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MCJ. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the pubmlst.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paradis E, Schliep K. Ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(3):526–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meier-Kolthoff JP, Goker M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vazquez-Boland JA, Scortti M, Meijer WG. Conservation of Rhodococcus equi (Magnusson 1923) Goodfellow and Alderson 1977 and rejection of Rhodococcus hoagii (Morse 1912) Kampfer et al. 2014. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70(5):3572–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alvarez-Narvaez S, Giguere S, Cohen N, Slovis N, Vazquez-Boland JA. Spread of multidrug-resistant Rhodococcus equi, united States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(2):529–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huber L, Giguere S, Slovis NM, Alvarez-Narvaez S, Hart KA, Greiter M, et al. The novel and transferable erm(51) gene confers macrolides, Lincosamides and streptogramins B (MLS(B)) resistance to clonal Rhodococcus equi in the environment. Environ Microbiol. 2020;22(7):2858–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Alegria Puig CR, Pilares L, Marco F, Vila J, Martinez-Martinez L, Navas J. Comparison of the Vitek MS and Bruker Matrix-Assisted laser desorption Ionization-Time of flight mass spectrometry systems for identification of Rhodococcus equi and Dietzia spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(7):2255–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vila J, Juiz P, Salas C, Almela M, de la Fuente CG, Zboromyrska Y, et al. Identification of clinically relevant Corynebacterium spp., Arcanobacterium haemolyticum, and Rhodococcus equi by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(5):1745–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berghaus LJ, Giguere S, Guldbech K, Warner E, Ugorji U, Berghaus RD. Comparison of etest, disk diffusion, and broth macrodilution for in vitro susceptibility testing of Rhodococcus equi. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(1):314–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gudeta DD, Moodley A, Bortolaia V, Guardabassi L. vanO, a new glycopeptide resistance Operon in environmental Rhodococcus equi isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(3):1768–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Duquesne F, Hebert L, Sevin C, Breuil MF, Tapprest J, Laugier C, et al. Analysis of plasmid diversity in 96 Rhodococcus equi strains isolated in Normandy (France) and sequencing of the 87-kb type I virulence plasmid. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;311(1):76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kalinowski M, Gradzki Z, Jarosz L, Kato K, Hieda Y, Kakuda T, et al. Plasmid profiles of virulent Rhodococcus equi strains isolated from infected foals in Poland. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0152887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tripathi VN, Harding WC, Willingham-Lane JM, Hondalus MK. Conjugal transfer of a virulence plasmid in the opportunistic intracellular actinomycete Rhodococcus equi. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(24):6790–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chirino-Trejo JM, Prescott JF. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of whole-cell preparations of Rhodococcus equi. Can J Vet Res. 1987;51(3):297–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lara GH, Takai S, Sasaki Y, Kakuda T, Listoni FJ, Risseti RM, et al. VapB type 8 plasmids in Rhodococcus equi isolated from the small intestine of pigs and comparison of selective culture media. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2015;61(3):306–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Makrai L, Takayama S, Denes B, Hajtos I, Sasaki Y, Kakuda T, et al. Characterization of virulence plasmids and serotyping of Rhodococcus equi isolates from submaxillary lymph nodes of pigs in Hungary. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(3):1246–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Takai S, Tharavichitkul P, Takarn P, Khantawa B, Tamura M, Tsukamoto A, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Rhodococcus equi of intermediate virulence isolated from patients with and without acquired immune deficiency syndrome in Chiang mai, Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(11):1717–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories under project reference number PRJNA1065651, https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1065651?reviewer=9vccetp4i7bqrev0jukj02psi0.