Abstract

A hazard to humanity is people’s indiscriminate use of pharmacological compounds, such as antibiotics, and their presence in the environment or water supplies, which are not eliminated during the purification process. Either left in open water, they cause sickness in humans and animals. As a result, antibiotic use management is required. This study aims to extract and assess the interactions between α, β, and γ-cyclodextrins (CD) and Tetracycline antibiotics. Studies show these chemicals have not yet been extracted and compared using various CDs. Thus, the molecular docking computational method was used to study the guest–host interaction of the CD with three types of Tetracycline antibiotics, which was helpful before laboratory investigation to achieve the ability to extract antibiotics by CD and to prevent wasting time and money. Although molecular docking provided valuable insights into the host–guest interactions, no molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted in the present study. Future investigations are recommended to perform MD simulations to assess the stability, flexibility (RMSF), and conformational stability (RMSD) of the CD-antibiotic complexes over time. The optimal orientation and manner of molecule binding for antibiotics in the CD cavity’s active site were examined using molecular docking studies. To fully capture the stability and flexibility of the docked complexes over time, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations should be employed as a complementary approach to docking studies. MD simulations allow for the observation of real-time structural fluctuations, solvent effects, and entropy contributions, which are not accounted for in standard docking models. Previous research has demonstrated the significance of MD in refining docking predictions and providing a more accurate assessment of host–guest stability in CD-based systems. Future studies should incorporate MD analyses to validate docking results and further enhance our understanding of tetracycline-CD interactions. As a result, the γ-type was the best for Doxycycline with the highest binding energy of − 8.1, and for Minocycline and Tetracycline with a binding energy of − 7.4 compared to α- and β-CD. Furthermore, the poorest host for the formation of the resultant complex was the α-CD cavity.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-04120-2.

Keywords: Molecular docking; Tetracycline antibiotics; α, β, and γ -cyclodextrin; Extraction

Subject terms: Computational chemistry, Chemical biology, Cheminformatics, Environmental chemistry

Introduction

Pharmaceutical substances called antibiotics are used to treat bacterial illnesses, and their extremely low levels in wastewater and the environment are thought to pose a major risk to both human health and the environment1. Antibiotics from a variety of applications, including veterinary and medical, infiltrate the environment and show up in soil, groundwater, surface water, and wastewater2, Recent studies have demonstrated that antibiotics remain persistent in aquatic environments, resulting in the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains and potential risks of bioaccumulation3 Moreover, studies have shown that conventional wastewater treatment plants fail to completely remove these contaminants, thus requiring alternative remediation techniques, including CDs-based extractions. To address these limitations, the current study details CDs’ capacity to act as sustainable agents for the removal of antibiotics and the associated mitigation of resulting environmental and health risks4.

In this study, we have focused on Tetracycline antibiotics (Doxycycline, Minocycline, and Tetracycline) that are prevalent in human and veterinary medicine and their persistence in aquatic systems. These antibiotics are widely used to treat bacterial infection but are not well removed in conventional wastewater treatment plants, resulting in their accumulation in surface waters and sediments5. Integrating as well as bioaccumulating tetracycline antibiotics in living tissues render them extremely dangerous as they lead to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and disrupt aquatic ecosystems6. To address these issues, this work will investigate how CDs can be used to specifically bind and extract these antibiotics from polluted waterways.

Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that Minocycline, a classical Tetracyclic antibiotic with high lipid solubility, has therapeutic potential against neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s disease, by inhibiting microglial activity and inflammatory cytokines. More recent research has demonstrated the antibiotic’s wide-ranging psychoactive effects as an antidepressant, anxiolytic, and nootropic7. Another class of tetracycline antibiotics is Doxycycline, which occur in three forms: hydrochloride, monohydrate, and hyclate, and is used to treat infectious disorders such as bacterial pneumonia, acne, cholera, and syphilis8. The following techniques have been studied thus far for the elimination of tetracycline antibiotics in aquatic environments: chemical oxidation, absorption, ultrasound, and microbiological approaches9.

The use of CD complexes is one of the strategies and tactics to get rid of and lessen the negative effects of these medications. A class of oligosaccharides known as CDs has numerous uses in biology and chemistry. They contain an outside hydrophilic surface that can interact with water molecules and an inner hydrophobic cavity that can trap molecules. Cyclic glucopyranose units are what give it its hydrophilic properties10. A complex is created when other substances enter CDs, which are made up of varying numbers of chair-shaped glucose units joined by bonds α-(1–4) D-glucopyranoses11. A cyclic molecular structure is formed by three primary CD types: α, which has six glucopyranose units, β, which has seven glucopyranose units, and γ, which has eight glucopyranose units. As a result, both in liquid and solid settings and in simulation software, a huge number of guests can be shown into the cavity with the participation of both the host and the guest12. These structural differences have a major influence on host–guest interactions and the consequent stability and efficiency of CD-based antibiotic removal methods. These differences should be further explored in experimental studies to determine optimal CD selection for use in environmental and pharmaceutical applications. Moreover, the development of lipid-based delivery systems, such as solid lipid nanoparticles, nanostructured lipid carriers, and liposomes, have gained significant attention in recent years as a result of their favorable biocompatibility and extensive use in pharmaceutical formulations to improve drug solubility and stability. Nonetheless, under high concentrations, some CDs, especially unmodified, may cause cytotoxic effects and represent environmental risks13. Studies have indicated that excessive concentrations of CDs can interfere with cell membrane integrity and disrupt microbial communities in aquatic environments14.

The use of γ-CD for environmental remediation by removal of antibiotics has been significantly investigated, and γ-CD was demonstrated as an effective host molecule to extract antibiotics from wastewater sources. It enhances the extraction and degradation of these persistent pollutants and causes the reduction of their ecological impact, given its capacity to stabilize with tetracyclines through exclusion complexes15. Moreover, γ-CD-based materials were also studied in wastewater treatment technology as selective adsorbents for the recovery of pharmaceutical residues based on their high efficiency16. In pharmaceutical applications, γ-CD has been utilized to improve the solubility, bioavailability, and controlled release of various drugs, including antibiotics. By enhancing drug stability and reducing toxicity, γ-CD-based formulations are promising candidates for improving therapeutic outcomes17. These practical applications highlight the versatility of γ-CD in both environmental and biomedical fields, emphasizing its importance in sustainable antibiotic management strategies.

We go over a few of the research that has been published up until the end of 2021 on the combination of CDs with antibiotics and antibacterial agents. Enhancing solubility, altering drug release properties, slowing down drug degradation, enhancing biological membrane permeability, and boosting antibacterial activity are some of the drug delivery applications that are the subject of these investigations18. Or the effects of CD complexes on medications exhibiting stability issues19, or the use of UV–vis and FT-IR spectroscopy to examine the formation of cyclodextrin complexes with phenolphthalein20. Or, utilizing epichlorohydrin cross-linking, a novel composite material based on sodium alginate airgel stabilized with (β -CD/NaAlg) was created and utilized as an adsorbent to extract tetracycline antibiotics from wastewater that had been recycled21. Recent studies have highlighted the advantages of CDs in pharmaceutical and environmental applications. For instance, a study by Li et al.22 compared the binding affinities of α-, β-, and γ-CDs with various antibiotics, emphasizing that γ-CD demonstrated the highest efficiency in forming stable complexes.

In addition, the recent advances in in-silico methods have improved the capability of computational studies on CD-antibiotic interaction. Research by Kumar et al.23 examined the dynamic stability of CD–antibiotic complexes using MD simulations. Purohit et al. conducted a separate study that24 used QM/MM hybrid methods to improve accuracy for binding energy calculations. This emphasizes our study’s importance in bridging the theoretical developments in CD chemistry with its applied work in drug delivery and environmental remediation, as these recent advancements indicate the growing trustworthiness and predictive power of computational models.

One technique for determining the ideal molecular orientation of a protein’s active site is molecular docking. Predicting the dependency factor can also be aided by selecting the optimal course. Because it can anticipate the best fit between small compounds and protein binding sites, this approach has been widely employed in drug creation25. and An effective method for researching how atoms and molecules interact and form bonds26. Stated differently, it is the most widely used technique for modeling interactions between a ligand (antibiotic) and a protein (CD).

In recent years, advances in in-silico techniques have significantly enhanced the study of host–guest interactions, particularly for cyclodextrin (CD) inclusion complexes. Computational methods such as molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) hybrid approaches, and binding free energy calculations (e.g., MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA) have become increasingly valuable tools for predicting complex stability, binding modes, and thermodynamic profiles. These approaches allow detailed insights into molecular flexibility, solvent effects, and binding affinity trends, which are often difficult to capture experimentally. Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of docking and MD simulations in elucidating the behavior of CD-antibiotic complexes and other pharmaceutical systems23,24,27–32. Incorporating these computational strategies enables a deeper and more predictive understanding of CD-based systems, thereby informing the rational design of more effective extraction and delivery platforms.

This study is novel in its comparative approach to evaluating the binding efficiencies of α, β, and γ-CDs with Tetracycline antibiotics, providing valuable insights into their potential applications in water purification and pharmaceutical formulations. Unlike previous studies that focused on either a single CD type or different antibiotic classes, this research systematically examines their interaction strengths using molecular docking. Additionally, it addresses the increasing environmental concern regarding antibiotic contamination and explores the feasibility of CDs as a sustainable solution for remediation. The medications Doxycycline, Minocycline, and Tetracycline were chosen for this study and utilized as ligands for molecular docking. Additionally, the guest–host complex was created by identifying the active site of each of the α, β, and γ-CD proteins. We looked into and contrasted the CDs’ binding locations with the target antibiotics. The type and style of interaction between the three varieties of CD were examined using a comparative method.

Methodology

Preparation of α, β, and γ-CDs (host) & tetracycline antibiotics (guest)

The three cyclodextrins (α-CD, β-CD, and γ-CD) were retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB IDs: 1CXF, 1BFN, and 1D3C, respectively). The antibiotic molecules, Tetracycline (PDB ID: 4B3A), Minocycline (PDB ID: 6QjX), and Doxycycline (PDB ID: 2O7O), were also obtained from the same source. These three antibiotics share a common Tetracycline core structure but differ in functional groups that influence their hydrophobicity, solubility, and binding interactions with cyclodextrins. Other structurally similar antibiotics, such as Tigecycline or Chlortetracycline, were not included due to the scope of this study, which aimed to focus on well-characterized tetracyclines with distinct yet comparable properties. Additionally, computational resource limitations and the need for a focused analysis of host–guest interactions contributed to limiting the number of antibiotics studied. Future studies may expand this research to include additional tetracycline derivatives to explore broader trends in cyclodextrin-antibiotic interactions.

Preparation of inclusion complex & software used

After receiving the host and guest molecules from the protein data bank website in PDB format, the next step is to use the software (ArgusLab.exe 4.0.1) with URL (https://arguslab.en.download.it/download) to remove the extra molecules and atoms in the structure. Finally, we save the desired composition structure in (Brookhaven pdb file) format.

The next step is the software (AutoDockTools-1.5.6) Which is one of the 4 programs available in the software (MGLTools) with URL (https://ccsb.scripps.edu/mgltools/downloads/), the active site of the host molecule is determined in this step, and the numbers related to Grid box center (x, y, z), and also Grid box dimensions (x, y, z) are specified and recorded. Molecular docking simulations were conducted using AutoDock Vina, which is part of the MGLTools suite. The following parameters were performed similarly for all interactions: Scoring function: Number of generated poses: 9, and Exhaustiveness: 8 (default setting in Vina unless explicitly modified). The following parameters were applied for Minocycline with α-CD: Grid box center (X, Y, Z): (82.349, 60.902, 45.658), Grid box dimensions (X, Y, Z): (38, 38, 38), Best binding affinity: − 5.5 kcal/mol, and RMSD range: (0.000–6.672)Å. for Minocycline with β-CD: Grid box center: (− 6.392, 28.4, 30.01), Grid box dimensions: (42, 36, 42), Best binding affinity: − 6.4 kcal/mol, and RMSD range: (0.000–7.830)Å. For Minocycline with γ-CD: Grid box center: (84.881, 59.252, 44.489), Grid box dimensions: (44, 42, 40), Best binding affinity: − 7.4 kcal/mol, and RMSD range: (0.000–8.754)Å. For Tetracycline with α-CD: Grid box center: (82.349, 60.902, 45.658), Grid box dimensions: (38, 38, 36), Best binding affinity: − 6.3 kcal/mol, and RMSD range: (0.000–6.611)Å. For Tetracycline with β-CD: Grid box center: (− 6.939, 28.4, 30.01), Grid box dimensions: (42, 36, 42), Best binding affinity: − 7.0 kcal/mol, and RMSD range: (0.000–6.951)Å. For Tetracycline with γ-CD: Grid box center: (84.867, 59.302, 44.343), Grid box dimensions: (44, 42, 40), Best binding affinity: − 7.4 kcal/mol, and RMSD range: (0.000–7.402)Å. For Doxycycline with α-CD: Grid box center: (82.349, 60.902, 45.658), Grid box dimensions: (38, 38, 38), Best binding affinity: − 5.9 kcal/mol, and RMSD range: (0.000–7.438)Å. For Doxycycline with β-CD: Grid box center: (− 6.939, 28.4, 30.01), Grid box dimensions: (44, 36, 42), Best binding affinity: − 7.3 kcal/mol, and RMSD range: (0.000–4.461)Å. For Doxycycline with γ-CD: Grid box center: (84.881, 59.252, 44.489), Grid box dimensions: (46, 42, 38), Best binding affinity: − 8.1 kcal/mol, and RMSD range: (0.000–7.466)Å. These parameters were chosen to ensure an adequate sampling of conformational space while maintaining computational efficiency. The docking process determined the electrostatic energies, dependency energy, active site flexibility, and hydrophobic interactions of the antibiotic-CD complexes. Finally, the output of the host–guest molecule is stored in the (pdbqt) format. Determining the electrostatic energies between various linkages, dependency energy, active site flexibility, and hydrophobic contacts are a few of this software’s functions.

The executable commands are then entered into a newly created text file with the title (conf). Ultimately, this work’s output (AutodockTools-1.5.6) shows up as two files (ref) and (log). Determining the coordinates and the optimal mode of the active interaction site allows for creating many potential modes of interaction and the ideal orientation of two guest–host molecules. This data is kept in the file (log), and it can be retrieved in many ways depending on the mode, including the degree of inclination and connection energy. A complex will be more stable if the derived number is more negative.

The estimated complexes were checked by 2 software (Python Molecule Viewer) (PMV-1.5.6), which is one of the 4 programs available in the software (MGLTools) with URL (https://ccsb.scripps.edu/mgltools/downloads/) and Discovery Studio 2021 Client (DS) with URL (https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download). In the (PMV) software, all interaction modes of two guest–host molecules are shown, from which only the best mode of the guest molecule can be selected. In the software (DS), the aggregate complex’s two-dimensional structure, the guest–host molecule’s orientation, the type of interactions, their location, and the distance between the atoms involved in the interaction of the aggregate complex are shown.

In general, Molecular docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina implemented within the MGLTools-1.5.6 package. The docking protocol involved setting the exhaustiveness parameter to 8 and generating nine binding poses for each antibiotic-CD interaction. The scoring function utilized by AutoDock Vina approximates the binding free energy based on a combination of steric, hydrophobic, hydrogen bonding, and torsional energy terms, without employing an explicit classical force field (e.g., AMBER or CHARMM). The grid box parameters, including center coordinates (x, y, z) and dimensions (x, y, z), were individually optimized for each docking simulation and are fully detailed for each system in the manuscript. No molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed within the current study; however, future work will incorporate MD simulations using standard force fields such as AMBER ff14SB or CHARMM36 to simulate complex behavior over extended timescales (typically 50–100 ns) to validate docking results and assess complex stability in a dynamic environment.

Results and discussion

One of the future objectives is to use molecular modeling and molecular docking techniques to extract medicinal components of tetracycline antibiotics more quickly and efficiently by host–guest interactions. α, β, and γ-CDs were the host molecules in this investigation, whereas Minocycline, Tetracycline, and Doxycycline were the target compounds employed as guest molecules (Tetracycline antibiotics). Using the Molecular Docking approach, the interaction and theoretical extraction of each antibiotic with α, β, and γ-CDs were investigated independently. Nine distinct modes were produced for each of the compounds, and they were organized starting with the optimal mode based on the degree of affinity or binding energy. The optimal mode and modeled orientation are displayed in the first mode.

Hydrogen bonding plays a crucial role in stabilizing the host–guest complexes by facilitating directional and specific interactions between the CDs and tetracycline antibiotics. Van der Waals forces contribute to additional stabilization by enabling weak but cumulative attractive interactions between non-polar regions of the molecules. Hydrophobic forces, though minimal, influence the binding in cases where non-polar regions of the antibiotics interact with the inner hydrophobic cavity of CDs, further reinforcing the complex formation.

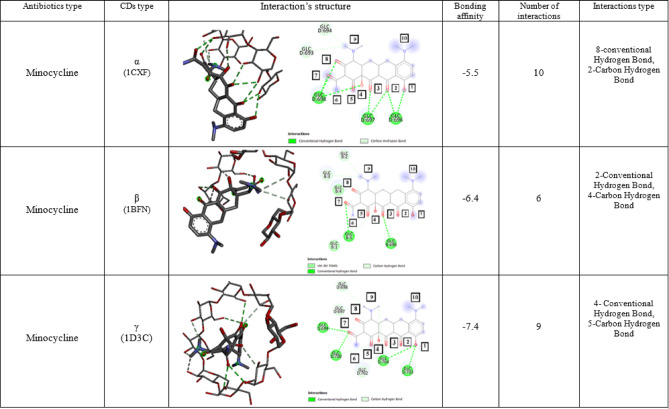

Docking results of minocycline antibiotics in α, β, and γ -CD and their comparison in terms of bonding affinity

As a result of minocycline’s docking with α, β, and γ -CD, nine states were determined. For the aggregated complex in docking, the first state in the findings always displays the optimal conformation.

Each kind of CD was docked with Minocycline separately. We are presented with the results in the form of tables, where the distance from the best mode data is expressed with (upper bound) rmsd u.b. and (lower bound) rmsd l.b. values that are computed exclusively for moveable heavy atoms. The distance at which atoms change between the two conformations varies with these values. In the (u.b.) state, the displacement of each atom from the optimal state is determined by comparing it to itself in a different shape. This mode works well when the molecule lacks internal symmetry, which is the case with the compounds this study looks at. Each atom in one conformation is measured in the (l.b.) mode by comparing it to the closest atom of the same type in another conformation. This method is employed when a molecule exhibits structural symmetry, like the benzene molecule.

The capacity to extract the antibiotic minocycline with high effectiveness and to accomplish its outcomes more quickly by using a CD cavity was investigated using molecular modeling and docking. α, β, and γ -CD were docked with Minocycline separately. As a result of its docking with each CD, nine states were determined. For the aggregated complex in docking, the first state in the findings always displays the optimal conformation. With energy levels of − 5.5, − 6.4, and − 7.4 kcal/mol, respectively, α, β, and γ-CD exhibit the optimal orientation and interaction with doxycycline (Table 1). Thus, γ-CD has the best binding energy.

Table 1.

Minocycline dock results with α, β, and γ -CD.

| Minocycline dock results with α-CD | Minocycline dock results with β -CD | Minocycline dock results with γ -CD | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Affinity | Dist from best mode | Mode | Affinity | Dist from best mode | Mode | Affinity | Dist from best mode | |||

| (kcal/mol) | rmsd l.b. | rmsd u.b. | (kcal/mol) | rmsd l.b. | rmsd u.b. | (kcal/mol) | rmsd l.b. | rmsd u.b. | |||

| 1 | − 5.5 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | − 6.4 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | − 7.4 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 2 | − 5.4 | 3.591 | 8.583 | 2 | − 6.4 | 3.463 | 5.456 | 2 | − 7.2 | 1.886 | 2.264 |

| 3 | − 5.2 | 1.703 | 2.192 | 3 | − 6.3 | 3.684 | 8.570 | 3 | − 7.2 | 4.160 | 6.367 |

| 4 | − 5.2 | 3.462 | 8.747 | 4 | − 6.1 | 3.757 | 8.430 | 4 | − 7.1 | 3.096 | 5.012 |

| 5 | − 5.1 | 4.396 | 8.533 | 5 | − 6.1 | 4.127 | 7.214 | 5 | − 7.1 | 4.372 | 6.370 |

| 6 | − 5.1 | 2.537 | 3.281 | 6 | − 6.0 | 1.799 | 2.187 | 6 | − 6.8 | 3.350 | 7.653 |

| 7 | − 5.1 | 1.984 | 2.307 | 7 | − 5.8 | 1.971 | 7.534 | 7 | − 6.8 | 2.769 | 4.593 |

| 8 | − 4.9 | 3.163 | 5.389 | 8 | − 5.8 | 2.857 | 4.617 | 8 | − 6.7 | 2.602 | 4.866 |

| 9 | − 4.8 | 3.510 | 6.672 | 9 | − 5.3 | 4.962 | 7.830 | 9 | − 6.6 | 4.668 | 8.754 |

Docking result of minocycline antibiotics in α-CD

Docking of minocycline with α-CD shows that due to the small diameter of the primary rim of the host molecule, Minocycline approached it through the secondary rim and the interaction took place from there. In the best case, the binding of the antibiotic minocycline with α-CD 10 occurs through the interaction (that 8 interactions are non-covalent and 2 interactions are covalent) with the secondary rim of α-CD, which includes:

The interaction of oxygen number 1 of minocycline with hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GLC D:696), which is of the usual Hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 2 of minocycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:696) and the Hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:697), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 3 of minocycline with hydrogens attached to the secondary 2- and 3-hydroxyl groups in the chain (GLC D:697), which is of the usual type of hydrogen bonds.

The interaction of oxygen number 4 of Minocycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:698), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen numbers 7 and 8 of minocycline with the Hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:698), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the carbon attached to the nitrogen number 9 of Minocycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:693), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type, and the next bond is with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-Hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:694).

Docking result of minocycline antibiotics in β -CD

The Molecular Docking of Minocycline with β-CD showed that the molecule has more space than α-CD to enter the cavity, and in the best case, the binding of this antibiotic with β-CD is 6 interactions (3 interactions are non-covalent and 3 interactions are covalent) with the primary and secondary rims, which include:

The interaction of oxygen number 3 of minocycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC B:496), which is of the usual Hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 7 of minocycline with the hydrogen attached to the primary 6-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC B:5), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 3 of Minocycline with the carbon attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC B:496), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 4 of Minocycline with the carbon attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC B:5), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type.

Interaction with carbon attached to nitrogen number 9 with hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls to the chain (GLC B:3) and hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 2-hydroxyls to the chain (GLC B:2), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type.

Docking result of minocycline antibiotics in γ -CD

The molecular docking of Minocycline and γ-CD showed that due to the large diameter of its primary and secondary rims compared to α and β, Minocycline enters the cavity completely. In the best case of binding between the Minocycline antibiotic and γ, 9 interactions (4 interactions are non-covalent and 5 interactions are covalent) occur with the primary and secondary rims of the CD molecule, which include:

The interaction of oxygen number 1 of minocycline with the hydrogen attached to the primary 6-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:703) and the hydrogen attached to the primary 6 hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:704), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 7 of minocycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:699) and the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:700), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 3 of Minocycline with the carbon attached to the primary 6-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:702), which is of the carbon-hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 4 of Minocycline with the carbon attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:700), which is of the carbon-hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the carbon attached to nitrogen number 9 with the hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GLC D:704) and the next carbon to the hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 2-hydroxyls in the chain (GLC D:698) and the hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GLC D:697), all of which are of the type It is a carbon–hydrogen bond (Table 2).

Table 2.

Interaction structure & bonding affinity of Minocycline with α, β, and γ-CD (all of the interactions with the best Mode (Mode1)).

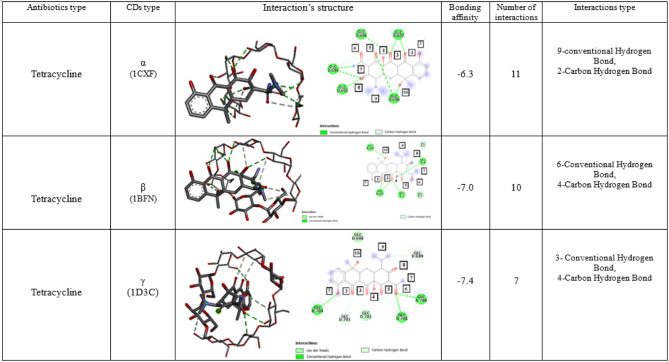

Docking results of tetracycline antibiotics in α, β, and γ -CD and their comparison in terms of bonding affinity

For the aggregated complex in docking Tetracycline with α, β, and γ -CD, the first state in the findings always displays the optimal conformation. With energy levels of − 6.3, − 7.0, and − 7.4 kcal/mol, respectively, α, β, and γ -CD exhibit the optimal orientation and interaction with doxycycline. γ-CD has the best binding energy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Tetracycline dock results with α, β, and γ -CD.

| Tetracycline dock result with α-CD | Tetracycline dock result with β-CD | Minocycline dock result with γ -CD | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Affinity | Dist from best mode | Mode | Affinity | Dist from best mode | Mode | Affinity | Dist from best mode | |||

| (kcal/mol) | rmsd l.b. | rmsd u.b. | (kcal/mol) | rmsd l.b. | rmsd u.b. | (kcal/mol) | rmsd l.b. | rmsd u.b. | |||

| 1 | − 6.3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | − 7.0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | − 7.4 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 2 | − 6.2 | 2.777 | 7.752 | 2 | − 6.9 | 3.134 | 7.282 | 2 | − 7.3 | 1.892 | 4.090 |

| 3 | − 5.9 | 2.104 | 4.194 | 3 | − 6.9 | 1.568 | 1.994 | 3 | − 7.0 | 3.169 | 7.253 |

| 4 | − 5.7 | 3.626 | 6.064 | 4 | − 6.7 | 3.210 | 6.978 | 4 | − 6.9 | 1.915 | 2.284 |

| 5 | − 5.7 | 3.258 | 7.713 | 5 | − 6.6 | 2.221 | 3.207 | 5 | − 6.8 | 3.021 | 7.309 |

| 6 | − 5.5 | 2.963 | 6.036 | 6 | − 6.4 | 3.092 | 5.494 | 6 | − 6.7 | 3.019 | 7.574 |

| 7 | − 5.4 | 3.520 | 6.571 | 7 | − 6.4 | 2.762 | 4.671 | 7 | − 6.6 | 3.062 | 7.369 |

| 8 | − 5.4 | 2.798 | 4.967 | 8 | − 6.2 | 3.081 | 5.202 | 8 | − 6.5 | 2.748 | 7.730 |

| 9 | − 5.0 | 4.190 | 6.611 | 9 | − 6.1 | 3.037 | 6.951 | 9 | − 6.5 | 2.791 | 7.402 |

Docking result of tetracycline antibiotics in α-CD

Docking Tetracycline with α-CD revealed that Tetracycline enters the cavity from the secondary rim because of the tiny diameter of CD’s primary rim. 11 interactions (9 interactions are non-covalent and 2 interactions are covalent) with α-CD’s secondary rim take place under the optimal scenario of Tetracycline interacting with α-CD. These interactions include:

The interaction of oxygen number 2 of tetracycline with hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GLC D:697), which is of the usual type of hydrogen bond.

The interaction of oxygen number 3 of tetracycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:696) and the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:697), both of which are the usual hydrogen bonds.

The interaction of oxygen number 5 of tetracycline with hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:698), which is of the usual Hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of nitrogen number 7 of tetracycline to the chain (GLC D:694), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 8 of tetracycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:694) and the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:695), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 10 of tetracycline with hydrogens attached to the secondary 2- and 3-hydroxyl groups in the chain (GLC D:698), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the OXYGEN number 6 of Tetracycline to the carbon attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:694), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 5 of Tetracycline to the carbon attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:696), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type.

Docking result of tetracycline antibiotic in β -CD

Tetracycline has greater room to enter the cavity than α-CD, according to the molecular docking of the two molecules. In the best scenario, 10 interactions (6 interactions are non-covalent and 4 interactions are covalent) with the secondary boundary taking place, including:

The interaction of oxygen number 2 of tetracycline with hydrogen attached to the secondary 2- and 3-hydroxyl groups in the chain (GLC B:496), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 3 of tetracycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC B:5) and the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC B:496), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 4 of tetracycline with hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GLC B:4), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 10 of tetracycline with hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC B:497) is of the usual Hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of hydrogen attached to oxygen number 4 to the chain (GLC B:4), which is of carbon–hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of hydrogen attached to nitrogen number 9 to the carbon of (GLC B:4) and (GLC B:3) chains, which is of carbon–hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the Hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 8 to the carbon of the chain (GLC B:3), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type.

Docking result of tetracycline antibiotic in γ -CD

Molecular docking between Tetracycline and γ -CD revealed that Tetracycline enters the cavity from the Phenolic head and has a good interaction with the γ type because its primary and secondary rims are larger than those of α and β. We may deduce that 7 interactions (3 interactions are non-covalent and 4 interactions are covalent) with the major and secondary rims of the CD molecule taking place in the optimal binding scenario between the tetracycline antibiotic and γ -CD. These interactions include:

The interaction of oxygen number 1 of tetracycline with hydrogen attached to the primary group of 6-hydroxyls in the chain (GLC D:704), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 6 of tetracycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:700) and the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group of the chain (GLC D:701), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 2 of Tetracycline to the carbon attached to the primary 6-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:703), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 3 of Tetracycline to the carbon attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:703), which is of the carbon-hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 5 of Tetracycline to the carbon attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:701), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the carbon attached to the nitrogen number 9 of Tetracycline to the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group in the chain (GLC D:699), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type (Table 4).

Table 4.

Interaction structure & Bonding affinity of Tetracycline with α, β, and γ-CD (all of the interactions with the best Mode (Mode1)).

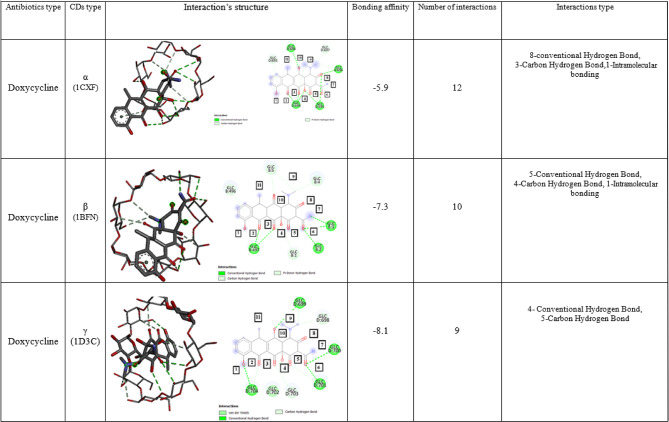

Docking results of doxycycline antibiotics in α, β, and γ -CD and their comparison in terms of bonding affinity

In all cases, the first state in the results shows the best conformation for the aggregated complex in docking. it can be seen that α, β, and γ-CDs have the best orientation and interaction on Doxycycline with an energy value of − 5.9, − 7.3, and − 8.1 kcal/mol, respectively. Thus, γ-CD has the best binding energy (Table 5).

Table 5.

Doxycycline dock results with α, β, and γ -CD.

| Doxycycline dock result with α-CD | Doxycycline dock result with β-CD | Doxycycline dock result with γ -CD | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Affinity | Dist from best mode | Mode | Affinity | Dist from best mode | Mode | Affinity | Dist from best mode | |||

| (kcal/mol) | rmsd l.b. | rmsd u.b. | (kcal/mol) | rmsd l.b. | rmsd u.b. | (kcal/mol) | rmsd l.b. | rmsd u.b. | |||

| 1 | − 5.9 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | − 7.3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | − 8.1 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 2 | − 5.9 | 2.712 | 4.572 | 2 | − 7.3 | 2.607 | 6.736 | 2 | − 7.7 | 1.985 | 4.430 |

| 3 | − 5.8 | 1.803 | 3.978 | 3 | − 7.2 | 1.742 | 4.077 | 3 | − 7.6 | 2.452 | 6.967 |

| 4 | − 5.8 | 2.893 | 8.117 | 4 | − 7.0 | 2.749 | 7.121 | 4 | − 7.4 | 3.598 | 6.898 |

| 5 | − 5.8 | 3.251 | 7.913 | 5 | − 6.7 | 3.140 | 7.226 | 5 | − 7.3 | 2.829 | 6.853 |

| 6 | − 5.7 | 2.945 | 7.876 | 6 | − 6.7 | 3.146 | 5.818 | 6 | − 7.2 | 2.915 | 6.696 |

| 7 | − 5.6 | 2.931 | 7.466 | 7 | − 6.6 | 2.390 | 3.261 | 7 | − 7.2 | 3.801 | 6.880 |

| 8 | − 5.6 | 3.780 | 6.452 | 8 | − 6.6 | 3.148 | 5.808 | 8 | − 7.1 | 2.806 | 7.188 |

| 9 | − 5.4 | 3.161 | 7.438 | 9 | − 6.4 | 2.059 | 4.461 | 9 | − 7.1 | 2.791 | 7.466 |

Docking result of doxycycline antibiotics in α-CD

Docking of Doxycycline with α-CD showed that due to the small diameter of the primary rim of the host molecule, doxycycline approached it through the secondary rim and the interaction took place from there and approached the cavity from its nitrogenous part. In the best case of Doxycycline antibiotic binding with α-CD, 12 interactions (8 interactions are non-covalent and 3 interactions are covalent, and one intramolecular interaction) occur with the secondary rim, which includes:

The interaction of oxygen number 2 of doxycycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group of the chain (GlC D:694), which is of the usual type of hydrogen bond.

The interaction of oxygen number 3 of doxycycline with hydrogens attached to the secondary groups of 2- and 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GlC D:694), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 4 of doxycycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group of the chain (GlC D:694) and the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group of the chain (GlC D:695), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 6 of doxycycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group of the chain (GlC D:695) and the Hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group of the chain (GlC D:696), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 10 of doxycycline with hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GlC D:698), which is of the usual type of hydrogen bond.

3-carbon–hydrogen interaction, which is established from the side of groups connected to nitrogen number 9 to chains (GlC D:696), (GlC D:697) and (GlC D:694).

An intramolecular interaction with the Phenolic ring to chain (GlC D:693) has also occurred.

Docking result of doxycycline antibiotic in β -CD

Docking of the Doxycycline molecule with β -CD showed that the molecule enters the cavity from the Nitrogenous side of the compound, and in the best case of binding this antibiotic with β -CD, 10 interactions and (7 interactions are non-covalent and 2 interactions are covalent, and one intramolecular interaction) occurs with the primary and secondary rims of β -CD, which include:

The interaction of oxygen numbers 2 and 3 of doxycycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group in the chain (GlC B:497), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 6 with the hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GlC B:2) and the hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 2-hydroxyls in the chain (GlC B:3), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of nitrogen number 7 with the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls to the chain (GlC B:3), which is of the usual type of hydrogen bond.

The interaction between the groups of nitrogen number 9 attached to the chain (GlC B:4) and the primary group of 6-hydroxyls to the chain (GlC B:5), which is of the usual type of hydrogen bond.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to oxygen number 4 with the Carbon attached to the secondary hydroxyl group 3 to the chain (GlC B:1) which is of the carbon–hydrogen type.

The interaction of hydrogen attached to oxygen number 10 with carbon attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GlC B:5), which is a type of carbon–hydrogen bond.

An intramolecular interaction with the phenolic ring has occurred to the chain (GlC B:496).

Docking result of doxycycline antibiotic in γ -CD

Molecular docking of Doxycycline and γ -CD showed that due to the large diameter of its primary and secondary rims compared to α and β, Doxycycline enters the cavity from the Phenolic ring and shows a good interaction with the γ type. It can be concluded that in the best case of Doxycycline antibiotic binding with γ, 9 interactions (5 interactions are non-covalent and 4 interactions are covalent) with the primary and secondary rims of the CD molecule occur, which include:

The interaction of oxygen number 1 of doxycycline with hydrogen attached to the primary group of 6 hydroxyls in the chain (GlC D:704), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 6 of doxycycline with the hydrogen attached to the secondary 3-hydroxyl group of the chain (GlC D:700) and the hydrogen attached to the secondary 2-hydroxyl group of the chain (GlC D:701), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of oxygen number 10 of doxycycline to the chain (GlC D:699), which is of the usual hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 2 of doxycycline to the carbon attached to the primary 6-hydroxyl group in the chain (GlC D:704), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of the hydrogen attached to the oxygen number 3 of Doxycycline to the carbon attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GlC D:703), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of Hydrogen attached to oxygen number 5 of doxycycline to carbon attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GlC D:701), which is of carbon–hydrogen bond type.

The interaction of carbon attached to nitrogen number 9 of doxycycline with hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 3-hydroxyls in the chain (GlC D:698) and with hydrogen attached to the secondary group of 2-hydroxyls in the chain (GlC D:699), which is of the carbon–hydrogen bond type (Table 6).

Table 6.

Interaction structure & bonding affinity of Doxycycline with α, β, and γ-CD (all of the interactions with the best Mode (Mode1)).

The higher binding affinity of γ-CD compared to α-CD and β-CD can be attributed to a combination of steric effects, hydrophobic interactions, and cavity size compatibility: (1) Cavity Size and Steric Effects: γ-CD has a larger cavity diameter compared to β-CD and α-CD. This larger cavity size allows for better accommodation of tetracycline antibiotics, reducing steric hindrance and enabling deeper insertion of the guest molecule. In contrast, α-CD has a smaller cavity that is too restrictive for optimal binding, which results in weaker interactions and lower docking scores. (2) Hydrophobic Interactions: Hydrophobic interactions play a key role in host–guest binding. Since γ-CD provides a larger nonpolar interior, it can form stronger van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions with the largely hydrophobic tetracycline backbone.β-CD also exhibits moderate hydrophobic stabilization but to a lesser extent than γ-CD due to its smaller cavity (3) Hydrogen Bonding and Orientation of the Guest Molecule: The orientation of antibiotics within the CD cavity influences binding strength. γ-CD’s larger size allows antibiotics to align more favorably, optimizing hydrogen bonding between functional groups of tetracyclines (e.g., hydroxyl, amide) and CD hydroxyl groups. α-CD has a more restricted binding mode, limiting the number and strength of hydrogen bonds33.

Beyond numerical binding affinity values, the specific non-covalent interactions between antibiotics and cyclodextrins play a crucial role in complex stabilization. Hydrogen bonding was observed between key polar functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carbonyl, and amine groups) of the guest molecules and the hydroxyl moieties on the primary and secondary rims of the CDs. Hydrophobic interactions, particularly π-alkyl and van der Waals contacts, contributed significantly to stabilizing the antibiotics within the non-polar cavity. For example, doxycycline exhibited multiple hydrogen bonds (e.g., via O11 and N4 atoms) and hydrophobic contacts within the γ-CD cavity, indicating a snug and energetically favorable fit. The number and geometry of these interactions correlate well with the observed binding energies, providing molecular-level justification for the higher affinity of γ-CD complexes. Visual analysis (2D interaction maps and 3D poses; Supplementary Figures) supports these findings and reveals that cavity size and shape directly influence the extent and type of interactions formed.

The binding energy values obtained in this study ranged from approximately − 5.5 kcal/mol (Minocycline with α-CD) to − 8.1 kcal/mol (Doxycycline with γ-CD). These results indicate moderate to strong host–guest interactions, consistent with reported binding affinities for cyclodextrin inclusion complexes in the literature, which typically range between − 5 and − 9 kcal/mol18,22. The superior binding affinities observed with γ-cyclodextrin (γ-CD) can be attributed to its larger cavity size, which provides better spatial accommodation for the tetracycline antibiotics, thereby enhancing hydrophobic interactions and the number of stabilizing hydrogen bonds. This observation aligns with previous findings, where γ-CD demonstrated enhanced complexation abilities with various guest molecules, including antibiotics22,23. The relatively small differences in binding energy between γ-CD and β-CD (e.g., − 8.1 vs. − 7.3 kcal/mol for Doxycycline) suggest that while γ-CD is the most effective host, β-CD also provides a reasonable alternative for complex formation. Overall, the results reinforce the critical role of cyclodextrin cavity size and geometry in determining the efficiency of host–guest binding interactions, with γ-CD emerging as a particularly promising candidate for tetracycline extraction applications.

A comparative analysis of the docking results reveals that minocycline exhibited slightly stronger binding affinities than tetracycline across all three types of cyclodextrins. This difference can be attributed to minocycline’s higher lipophilicity and more flexible molecular structure, which facilitate deeper insertion into the cyclodextrin cavities and the formation of more extensive non-covalent interactions. Both antibiotics showed the highest binding affinities with γ-cyclodextrin (γ-CD), supporting the idea that a larger cavity size promotes more stable inclusion complex formation. The findings are consistent with existing literature indicating that the size and hydrophobicity of the guest molecule, as well as the geometric complementarity with the host cavity, critically influence the stability and binding strength of CD-based complexes18,22. These results suggest that γ-CD could serve as an efficient host for the extraction and stabilization of tetracycline antibiotics from aqueous environments.

Limitations and future work

Molecular docking methods suffer from limitations, especially in scoring functions, which estimate binding affinities based on simplified energy calculations. These functions can often neglect solvent effects, entropy contributions, and dynamic molecular flexibility, intrinsically introducing inaccuracies into anticipated interactions34. Furthermore, docking studies postulate a rigid receptor-ligand interaction, while the real biomolecular interactions are dynamic. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can account for dynamic conformational fluctuations and environmental factors, allowing for a more comprehensive assessment of docking predictions and enhancing prediction performance35. However, in this study, MD simulations were not conducted. The discussion on MD simulations is a recommendation for future research rather than an integral part of the current analysis. Future studies should incorporate MD simulations to provide a more precise estimation of binding energy and improve the predictive capability of CD-antibiotic complex stability. By integrating MD simulations with docking studies, a more accurate and dynamic representation of host–guest interactions can be achieved, leading to improved reliability in computational predictions. Additionally, since docking simulations were performed in a vacuum environment without explicit solvation, future work should incorporate implicit solvation models or solvent-explicit MD simulations to better represent the aqueous environment in which CD-antibiotic interactions occur. By integrating MD simulations with docking studies, a more accurate and dynamic representation of host–guest interactions can be achieved, leading to improved reliability in computational predictions (Figs. 1 and 2).

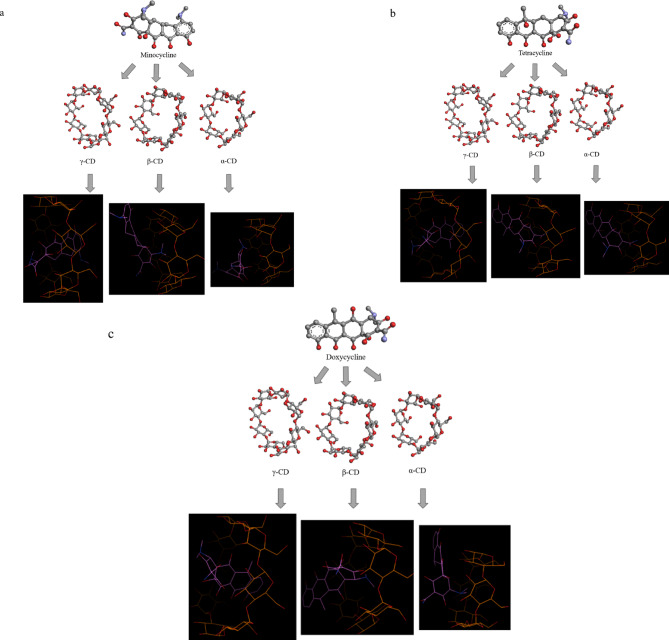

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of molecular docking for a) Minocycline b) Tetracycline c) Doxycycline antibiotics with α, β, and γ-CDs with Mode1.

Fig. 2.

Overview of the study on the best result of the complexation of Doxycycline with γ-CD.

Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) and Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) calculations have been known as powerful methods to enhance free-energy evaluations in molecular docking studies. These methods allow a better estimation of binding affinities since they account for solvation effects and entropic contributions, which are typically ignored in standard docking simulations36. By applying MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA, researchers can refine docking predictions and obtain a better understanding of the stability and energetics of antibiotic-CD complexes. Future studies should consider integrating these methods to enhance the reliability and precision of computational binding assessments37. Moreover, entropy effects in binding energy calculations were not explicitly considered in this study. Computational approaches such as MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA could enhance the accuracy of free energy estimations by integrating entropic contributions. These methods account for solvent interactions and dynamic conformational changes, providing a more realistic representation of host–guest complex stability. Therefore, future research should employ MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA calculations to complement docking results and improve the predictive accuracy of antibiotic-CD interactions. Furthermore, while this study focused on Doxycycline, Minocycline, and Tetracycline as representative tetracyclines, future work could expand the dataset to include additional derivatives such as Tigecycline or Chlortetracycline to assess broader structural trends in cyclodextrin binding. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of antibiotic-CD interactions and refine predictive docking methodologies. Additionally, this study focused exclusively on native cyclodextrins (CDs) rather than their modified derivatives. While methylated and hydroxypropyl derivatives of CDs have been shown to improve solubility and binding affinity, they were not considered here to establish a baseline comparison of native CD interactions. Future studies should explore the impact of these modifications on antibiotic complexation, as they may enhance binding efficiency, selectivity, and practical applicability in environmental and pharmaceutical settings.

Much research has been done on the modified CDs due to their greater solubility and superior binding affinity in comparison to the unmodified CDs, making these more attractive candidates for drug delivery and environmental remediation applications. Chemical modifications, such as methylation, Hydroxypropylation, and sulfation, change the hydrophilic-lipophilic balance of CDs, thus increasing their capacity to form stable inclusion complexes with a broader spectrum of guest molecules38. Such reforms not only increase the recovery efficiency of tetracycline antibiotics but also make it possible to selectively target specific contamination in an aqueous environment39. Future experimental studies should focus on evaluating the comparative effectiveness of native and modified CDs in real-world water treatment systems and controlled drug-release mechanisms. Such studies would provide valuable insights into optimizing CD-based strategies for sustainable pharmaceutical and environmental applications. However, molecular docking as a predictive tool has inherent limitations, particularly in terms of scoring function accuracy and underlying assumptions. Scoring functions estimate binding affinities based on simplified energy models that often fail to capture solvent effects, entropy contributions, and dynamic molecular flexibility40. Moreover, docking methods assume rigid receptor-ligand interactions, which do not accurately reflect the dynamic nature of molecular complexes in biological or environmental conditions. These limitations can introduce variability in binding energy predictions and reduce the reliability of reported results. To address these challenges, integrating molecular dynamics MD simulations alongside docking studies can provide a more accurate and dynamic representation of host–guest interactions, improving the predictive power of computational approaches41. Additionally, changes in pH can significantly influence the binding affinity of Tetracyclines to CDs due to their amphoteric nature. Tetracyclines contain multiple ionizable functional groups, including Hydroxyl and amine moieties, which can undergo protonation or deprotonation depending on the pH of the surrounding environment. At lower pH values, increased protonation may enhance electrostatic interactions, while at higher pH, deprotonation could reduce hydrogen bonding potential, affecting the overall stability of the inclusion complex42. Therefore, future studies should investigate pH-dependent variations in tetracycline-CD interactions to optimize extraction conditions for environmental and pharmaceutical applications. In addition, Tetracycline antibiotics feature pH-dependent charge states, influenced by their ionizable functional groups. Consequently, the binding affinity and interaction stability between these antibiotics and CDs can vary significantly based on environmental pH conditions. However, this study did not conduct pH-dependent docking simulations, presenting a limitation in our analysis. Future research should consider the implementation of pH-sensitive molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations to assess how binding affinities change under different pH environments. Such studies will enhance our understanding of the influence of pH on the efficacy of CD-based extraction methods for tetracycline antibiotics, leading to more accurate models of antibiotic behavior in natural aquatic systems. Finally, while docking scores provide insight into the relative binding affinities of tetracycline antibiotics with CDs, they do not directly translate to real-world extraction efficiency in wastewater treatment. Real-world applications involve complex environmental conditions, including the presence of competing contaminants, pH variations, and dynamic flow systems. To better assess extraction efficiency, further thermodynamic and kinetic studies should be conducted, such as isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) for binding thermodynamics and adsorption/desorption kinetic experiments in realistic wastewater environments. These experimental validations will help bridge the gap between computational predictions and practical applications43.

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool in optimizing docking protocols and predicting host–guest interactions with higher accuracy and efficiency. By leveraging data-driven models, ML algorithms can analyze vast molecular interaction datasets to refine docking parameters, improve scoring functions, and predict the most probable binding conformations with greater reliability. Furthermore, deep learning-based approaches have demonstrated success in modeling complex host–guest dynamics, enabling the identification of novel CD derivatives with enhanced binding properties44. Future studies should integrate ML techniques with molecular docking and MD simulations to accelerate computational screening and enhance the predictive capabilities of CD-antibiotic interactions.

Another limitation of this study is the lack of explicit docking protocol validation. Redocking known co-crystallized ligands and calculating the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) between experimental and predicted poses are standard practices for assessing docking reliability. Typically, an RMSD value below 2 Å indicates accurate docking predictions25. Additionally, direct comparisons with available crystallographic structures of cyclodextrin-antibiotic complexes would further validate the docking results. Future work should incorporate redocking experiments, RMSD analyses, and experimental pose comparisons to enhance molecular docking outcomes’ credibility and predictive reliability.

Furthermore, this study did not include control docking experiments with known cyclodextrin-guest complexes or comparisons with experimentally determined binding affinities. Benchmarking docking predictions against well-characterized CD-guest systems would provide a critical validation of docking scores and enhance the interpretive strength of the computational findings. Future work should incorporate docking of known ligands into their respective cyclodextrins and compare the predicted binding affinities and orientations with available experimental data. Such validation would help establish the reliability of the docking methodology and place the observed binding energies of tetracycline antibiotics within a broader, experimentally supported context30,31.

Potential toxicity of cyclodextrins

While CDs are widely utilized in pharmaceutical, food, and environmental applications due to their inclusion complex formation ability, their potential cytotoxicity at high concentrations is a critical consideration. Studies indicate that CD toxicity is concentration-dependent and varies by CD type. In general:

α-CD and β-CD exhibit moderate cytotoxicity due to their limited solubility, which may lead to membrane disruption.

γ-CD is considered the least toxic among natural CDs due to its higher aqueous solubility and reduced membrane interaction.

For environmental remediation applications, CDs are typically used at low, controlled concentrations to minimize toxicological risks. Moreover, modified CDs, such as hydroxypropyl-β-CD (HP-β-CD) and methylated CDs, have been developed to enhance solubility and reduce toxicity while maintaining efficient pollutant complexation. Previous studies suggest that biodegradable and modified CDs offer a safer alternative for practical applications in pollutant removal without posing significant ecological risks45.

We acknowledge this limitation and recommend dose-dependent toxicity assessments for future applications of CDs in environmental remediation. Future studies should also explore the use of biodegradable and functionalized CD derivatives to mitigate cytotoxic effects while maintaining their pollutant removal efficiency.

Conclusion

In this study, we used molecular docking experiments to examine the extraction of three different Tetracycline antibiotics—Minocycline, Tetracycline, and Doxycycline—with all three types of α, β, and γ-CD and covered the expense and time. A comparative analysis of binding energies revealed that γ-CD consistently exhibited the highest affinity for tetracycline antibiotics, with binding energies of − 8.1 kcal/mol for doxycycline, − 7.4 kcal/mol for minocycline, and − 7.4 kcal/mol for tetracycline. This superior binding efficiency can be attributed to the larger cavity size of γ-CD, which facilitates deeper and more stable host–guest interactions. In contrast, α-CD showed the weakest binding due to steric hindrance and limited cavity size, restricting the accommodation of bulky tetracycline molecules. β-CD displayed moderate binding affinities, balancing steric fit and interaction strength. These structural differences highlight the necessity of selecting appropriate CDs based on target antibiotics, ensuring optimal extraction efficiency and stability in real-world applications.

Although γ-cyclodextrin (γ-CD) exhibited the most favorable binding energies across all tetracycline antibiotics studied (e.g., − 8.1 kcal/mol for doxycycline), the differences in binding energies compared to β- and α-CD (e.g., − 7.4 kcal/mol and − 7.3 kcal/mol) are relatively small. Thus, while γ-CD appears to be the best host based on molecular docking scores, statistical validation through binding free energy difference (ΔΔG) analysis or advanced free energy methods such as MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA calculations is necessary to confirm the significance of these differences. Previous studies have demonstrated that even small variations in binding energy may not always correlate with substantial differences in binding stability without further energetic decomposition and statistical validation30,31. Therefore, future work should incorporate these computational techniques to ensure the robustness and reliability of the observed trends in host–guest interactions.

This study provides a computational perspective on the extraction of Tetracycline antibiotics using CDs. These findings offer critical guidance for future laboratory investigations by providing a preliminary screening of host–guest interactions before experimental validation. Molecular docking predictions can aid in selecting the most effective CD derivatives for targeted antibiotic removal in aqueous environments, reducing trial-and-error approaches in experimental setups. Furthermore, large-scale environmental applications, such as wastewater treatment and pharmaceutical contamination control, could benefit from these insights by identifying cost-effective and sustainable remediation strategies. Future research should focus on integrating computational and experimental methods to optimize CD-based filtration systems and evaluate their efficiency under real-world conditions. Additionally, experimental studies should focus on validating these computational results through binding assays, spectroscopic analyses, and chromatographic techniques to confirm the stability and efficiency of CD-antibiotic complexes. Real-world applications, particularly in wastewater treatment plants, should be assessed by evaluating the ability of CDs to capture and remove antibiotics under different environmental conditions. Pilot-scale studies examining the scalability of these approaches will further determine their feasibility for large-scale water purification systems. By bridging computational predictions with laboratory and field studies, a more comprehensive and practical framework for antibiotic removal can be developed46. Figure 1 separately shows the Docking of Minocycline, Tetracycline, and Doxycycline antibiotics with α, β, and γ-CDs with PMV software. Also, Fig. 2 shows the overview of the study in the best result of the investigated antibiotics, i.e. the formation of Doxycycline complex with γ-CD.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors wrote the main manuscript text and reviewed it.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be required in an alternative format, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zheng, Y. et al. Comparison of tetracycline rejection in reclaimed water by three kinds of forward osmosis membranes. Desalination359, 113–122 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chio, H. et al. Predicting bioactivity of antibiotic metabolites by molecular docking and dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. Model.123, 108508 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong, S. et al. Source preventing mechanism of florfenicol resistance risk in water by VUV/UV/sulfite advanced reduction pretreatment. Water Res.235, 119876 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenyvesi, É. et al. Removal of hazardous micropollutants from treated wastewater using cyclodextrin bead polymer—a pilot demonstration case. J. Hazard. Mater.383, 121181 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong, S. F. et al. Transformation products of tetracyclines in three typical municipal wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ.830, 154647 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li, X. et al. Removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in the synthetic oxytetracycline wastewater by UASB-A/O (MBR) process. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.11 (3), 109699 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng, D. et al. Minocycline, a classic antibiotic, exerts psychotropic effects by normalizing microglial neuroinflammation-evoked tryptophan-kynurenine pathway dysregulation in chronically stressed male mice. Brain. Behav. Immun.107, 305–318 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandey, M. et al. Preparation and characterization of cyclodextrin complexes of doxycycline hyclate for improved photostability in aqueous solution. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem.102 (3), 271–278 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang, L. et al. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in the aquatic environment: Biotoxicity, determination and electrochemical treatment. J. Clean. Prod.388, 135923 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alshati, F. et al. Guest-host relationship of cyclodextrin and its pharmacological benefits. Curr. Pharm. Design. 29 (36), 2853–2866 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsiung, E. et al. Antibacterial nanofibers of pullulan/tetracycline-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes for fast-disintegrating oral drug delivery. J. Colloid Interface Sci.610, 321–333 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leelasabari, C. et al. Characterization and molecular Docking analysis for the supramolecular interaction of Lidocaine with β-Cyclodextrin. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd.43 (2), 1202–1218 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loftsson, T., Saokham, P. & Couto, A. R. S. Self-association of cyclodextrins and cyclodextrin complexes in aqueous solutions. Int. J. Pharm.560, 228–234 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trotta, F. et al. Integration of cyclodextrins and associated toxicities: A roadmap for high quality biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym.295, 119880 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu, C. et al. Removal of contaminants present in water and wastewater by cyclodextrin-based adsorbents: A bibliometric review from 1993 To 2022. Environ. Pollut.348 123815 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, Y. et al. Cyclodextrin-derived materials: From design to promising applications in water treatment. Coord. Chem. Rev.502, 215613 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, L. et al. Anti-Inflammatory nanotherapies based on bioactive cyclodextrin materials. Adv. NanoBiomed Res.3 (12), 2300106 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boczar, D. & Michalska, K. Cyclodextrin inclusion complexes with antibiotics and antibacterial agents as drug-delivery systems—A pharmaceutical perspective. Pharmaceutics14 (7), 1389 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aiassa, V. et al. Cyclodextrins and their derivatives as drug stability modifiers. Pharmaceuticals16 (8), 1074 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kouderis, C. et al. The effect of alkali iodide salts in the inclusion process of phenolphthalein in β-Cyclodextrin: A spectroscopic and theoretical study. Molecules28 (3), 1147 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quan, X. et al. Selective adsorption of tetracycline by β-CD-immobilized sodium alginate aerogel coupled with ultrafiltration for reclaimed water. Chin. J. Chem. Eng.68, 27–34 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, Z. et al. A dual-emission ratiometric fluorescent sensor L/J-CDs with specific response to cetirizine hydrochloride in environmental water samples. J. Mater. Chem. C. 12 (46), 18704–18715 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar, P., Bhardwaj, V. K. & Purohit, R. Dispersion-corrected DFT calculations and umbrella sampling simulations to investigate stability of chrysin-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. Carbohydr. Polym.319, 121162 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar, P. & Purohit, R. Exploring cyclodextrin-glabridin inclusion complexes: Insights into enhanced pharmaceutical formulations. J. Mol. Liq.414, 126160 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng, L., Feng, K. & Ren, Y. Molecular modelling studies of tricyclic triazinone analogues as potential PKC-θ inhibitors through combined QSAR, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations techniques. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng.91, 155–175 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, K. et al. Molecular spectra and docking simulations investigated the binding mechanisms of tetracycline onto E. coli extracellular polymeric substances. Talanta276, 126231 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar, P., Bhardwaj, V. K. & Purohit, R. Unveiling the intricate supramolecular chemistry of γ-cyclodextrin-epigallocatechin gallate inclusion complexes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.63 (6), 2544–2554 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar, P., Bhardwaj, V. K. & Purohit, R. Highly robust quantum mechanics and umbrella sampling studies on inclusion complexes of curcumin and β-cyclodextrin. Carbohydr. Polym.323, 121432 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhardwaj, V. K. & Purohit, R. A comparative study on inclusion complex formation between formononetin and β-cyclodextrin derivatives through multiscale classical and umbrella sampling simulations. Carbohydr. Polym.310, 120729 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar, P., Bhardwaj, V. K. & Purohit, R. Molecular and quantum mechanical insights of conformational dynamics of Maltosyl-β-cyclodextrin/formononetin supramolecular complexes. J. Mol. Liq.397, 124196 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar, P. & Purohit, R. Driving forces and large scale affinity calculations for piperine/γ-cyclodxetrin complexes: Mechanistic insights from umbrella sampling simulation and DFT calculations. Carbohydr. Polym.342, 122350 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar, P. et al. Computational and experimental analysis of Luteolin-β-cyclodextrin supramolecular complexes: Insights into conformational dynamics and phase solubility. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm.205, 114569 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valente, A. J., Carvalho, R. A. & Soderman, O. Do cyclodextrins aggregate in water? Insights from NMR experiments. Langmuir31 (23), 6314–6320 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scarpino, A., Ferenczy, G. G. & Keserű, G. M. Covalent docking in drug discovery: Scope and limitations. Curr. Pharm. Design. 26 (44), 5684–5699 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rojas, S. et al. Combined MD/QTAIM techniques to evaluate ligand-receptor interactions. Scope and limitations. Eur. J. Med. Chem.208, 112792 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang, D. et al. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 10. Prediction reliability of binding affinities and binding poses for RNA–ligand complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.26 (13), 10323–10335 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen, Y. Q. et al. Improving performance of screening MM/PBSA in protein–ligand interactions via machine learning. Chin. Phys. B. 34 (1), 018701 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, X., Liu, J. & Qiu, N. Cyclodextrin-based polymeric drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. Polymers15 (6), 1400 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pang, J. et al. High-sensitive determination of tetracycline antibiotics adsorbed on microplastics in mariculture water using pre-COF/monolith composite-based in-tube solid phase Microextraction on-line coupled to HPLC-MS/MS. J. Hazard. Mater.469, 133768 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma, L. et al. Computational insights into cyclodextrin inclusion complexes with the organophosphorus flame retardant DOPO. Molecules29 (10), 2244 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan, F. et al. Identification of novel PI3Kα inhibitor against gastric cancer: QSAR-, molecular docking-, and molecular dynamics simulation-based analysis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 196 1–14. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, H. et al. Enhanced performance of β-cyclodextrin modified Cu2O nanocomposite for efficient removal of tetracycline and dyes: Synergistic role of adsorption and photocatalysis. Appl. Surf. Sci.621, 156735 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mic, M. et al. Inclusion of a catechol-derived Hydrazinyl-Thiazole (CHT) in β-Cyclodextrin nanocavity and its effect on antioxidant activity: A calorimetric, spectroscopic and molecular Docking approach. Antioxidants12 (7), 1367 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng, S. et al. Machine learning–enabled virtual screening indicates the anti-tuberculosis activity of aldoxorubicin and Quarfloxin with verification by molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and biological evaluations. Brief. Bioinform.26 (1), bbae696 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Köse, K. et al. Modification of cyclodextrin and use in environmental applications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.29 (1), 182–209 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu, Z. et al. Carboxymethyl-β-cyclodextrin functionalized TiO2@ Fe3O4@ RGO magnetic photocatalyst for efficient photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline under visible light irradiation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.12 (5), 113303 (2024). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be required in an alternative format, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.