Abstract

A molecular understanding of the regulation of IgG class switching to IL-4-independent isotypes, particularly to IgG2a, remains largely unknown. The T-box transcription factor T-bet directly regulates Th1 lineage commitment by CD4 T cells, but its role in B lymphocytes has been largely unexplored. We show here a role for T-bet in the regulation of IgG class switching, especially to IgG2a. T-bet-deficient B lymphocytes demonstrate impaired production of IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 and, most strikingly, are unable to generate germ-line or postswitch IgG2a transcripts in response to IFN-γ. Conversely, enforced expression of T-bet initiates IgG2a switching in cell lines and primary cells. This function contributes critically to the pathogenesis of murine lupus, where the absence of T-bet strikingly reduces B cell-dependent manifestations, including autoantibody production, hypergammaglobulinemia, and immune-complex renal disease and, in particular, abrogates IFN-γ-mediated IgG2a production. Classical T cell manifestations persisted, including lymphadenopathy and cellular infiltrates of skin and liver. These results identify T-bet as a selective transducer of IFN-γ-mediated IgG2a class switching in B cells and emphasize the importance of this regulation in the pathogenesis of humorally mediated autoimmunity.

Upon activation, mature B lymphocytes may undergo class-switch recombination (CSR) to produce a single, specific Ig isotype, which may include IgA, IgE, or one of the IgG subclasses (1). Although many extracellular signals play prominent roles in this process, cytokines such as IL-4, IFN-γ, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) appear to play particularly critical roles in B cell differentiation in part by directing the isotype specificity of CSR. For instance, IL-4 directs murine IgE and IgG1 isotype production by activating transcription factors such as STAT6, which bind to and transactivate the germ-line Cɛ and Cγ1 promoters (2). Isotype specificity of CSR presumably is determined at least in part through the regulation of these resulting sterile, germ-line RNA transcripts, which presumably make the target isotype locus accessible to the CSR machinery (3). Similarly, the cytokines IFN-γ and TGF-β are thought to regulate B cell CSR to the IL-4-independent IgG isotypes: TGF-β appears to selectively stimulate CSR to IgG2b (4), whereas IFN-γ appears to selectively stimulate IgG2a (5) and play a controversial role in the regulation of IgG3 (5, 6). However, the molecular mechanisms by which these cytokines regulate these latter isotypes remain largely unknown, particularly for IFN-γ and IgG2a.

The regulation of these IL-4-independent isotypes remains an investigative priority in part because they are often pathogenic in autoantibody-mediated disease states such as lupus, particularly in relationship to IFN-γ production (7–9). Indeed, the pathogeneses of many humoral autoimmune syndromes, including lupus, rely heavily upon T helper 1 (Th1) T cells, which are hallmarked by IFN-γ production, and the marked representation of these isotypes in the hypergammaglobulinemia and autoantibody production in such syndromes often has been considered to be related to this underlying “Th1-ness” (10, 11). Nevertheless, the mechanisms by which IFN-γ regulates B cell autoimmunity remains somewhat unexplored. Accordingly, further understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which IFN-γ contributes to B cell responses, including CSR, likely also will provide insight into the pathogenesis of humorally mediated autoimmune syndromes such as lupus, and vice versa.

The T-box transcription factor T-bet plays a critical role in Th1 lineage commitment by CD4 T cells and, therefore, likely contributes significantly to autoimmune disease pathogenesis (12–14). We generated T-bet-deficient, lupus-prone mice, expecting a T cell-dependent phenotype; we were surprised to find that T-bet was dispensable for T cell-mediated autoimmune disease manifestations yet was required for the development of humoral autoimmunity and hypergammaglobulinemia of IL-4-independent isotypes. Further investigation determined that T-bet was required for the induction of IgG2a germ-line transcripts by IFN-γ, suggesting that it regulates autoantibody production and IgG CSR in a B cell-intrinsic fashion.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Cell Lines.

BALB/c, C57BL/6, FVB, MRL/Mp-Faslpr/lpr, and IFN-γ receptor (IFN-γR)-deficient mice (15) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. T-bet-deficient mice were generated via traditional gene-targeting methods in C57BL/6 × 129 chimeras and confirmed to be deficient in T-bet protein (14). To generate a transgenic mouse with enforced expression of T-bet under the early cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, a pCDNA3.1-based (Invitrogen) T-bet expression construct (12) was linearized and injected into FVB oocytes. The founder line used for this study was backcrossed against C57BL/6 or IFN-γR-deficient (129) strains at least twice before use. T-bet+/+Fas+/+, T-bet−/−Fas+/+, T-bet+/+ Faslpr/lpr, and T-bet−/−Faslpr/lpr animals were generated by intercrossing the F1 progeny of a T-bet+/− × MRL/Mp-Faslpr/lpr mating. Genotypes for Fas (CD95) (16) and IFN-γR (17) were determined by PCR on tail DNA as described previously. For T-bet knockout and transgenic genotypes, PCR was performed in a PTC-100 Thermal Cycler (MJ Research, Cambridge, MA) under the following conditions: 94°C, 4′, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C, 1′; 60°C, 1′; 72°C, 1′. For the T-bet knockout, primers Tb-596F, Tb-314R, and PGKPR1220R were combined in a trimolecular reaction, which produced a 282-bp band corresponding to the wild-type allele and an ≈350-bp band corresponding to the mutant allele. The T-bet transgenic was detected by using primers D1000673F and D1000947R, which produced a 274-bp product corresponding to the transgenic allele and a 623-bp internal control product corresponding to the endogenous T-bet genomic locus. The 18.81 murine pre-B cell line (18), a gift of Wes Dunnick (Universiy of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), and the M12 murine B cell lymphoma were maintained in RPMI medium 1640 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) with 10% (vol/vol) FCS (HyClone).

Disease Characterization.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of formalin-fixed tissue sections, immunofluorescent studies on OCT-embedded frozen sections, flow cytometry of lymphoid cells, and assays for serum autoantibodies were performed as described (19). Specific antibodies used in this study included R4–6A2 and XMG1.2 (anti-mouse IFN-γ), BVD4–1D11 and BVD6–24G2 (anti-mouse IL-4), MP5–20F3 and MP5–32C11 (anti-mouse IL-6), JES5–2A5 and SXC-1 (anti-mouse IL-10), MP1–22E9 and MP1–31G6 (anti-mouse granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor), TN3–19.12 (anti-mouse TNF-α), rabbit anti-TNF-α, HM40–3 (anti-mouse CD40), 1D3 (anti-mouse CD19), and PE-R3–34 (rat IgG1, κ) (PharMingen); PE-H106.771 (rat IgG1, κ anti-mouse IgG2a) (Southern Biotechnology Associates); and FITC-goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG (Sigma). Anti-DNA activity was determined by ELISA, using high-molecular-weight mouse DNA (Sigma), and confirmed by immunofluorescence on Crithidia lucilliae kinetoplasts (Antibodies, Inc.).

T Cell Assays.

Naive CD4+ T cells were purified from spleen and lymph nodes by negative selection (R & D Systems) and stimulated for 48–72 h in RPMI/10% with 1 μg/ml anti-murine CD28 (37.51) antibody and 1 μg/ml plate-bound anti-murine CD3 (145–2C11) antibody (PharMingen). Cytokine production was evaluated in culture supernatants by ELISA (PharMingen). Proliferation was measured by BrdUrd incorporation (Amersham Pharmacia). Apoptosis was evaluated by exposing the cells for 24 h to 20 μg/ml soluble anti-mouse CD3 and anti-mouse CD28, 5 μg/ml dexamethasone (Sigma), or 1,200-J UV irradiation in a Stratalinker (Stratagene), followed by evaluation by the CaspACE Assay System (Promega).

Ig Assays.

For in vitro analyses, purified mature B cells were isolated from spleen and lymph nodes by magnetic CD43 depletion (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and stimulated in RPMI/10% with 25 μg/ml LPS (Sigma) supplemented with recombinant murine IL-4 at 10 ng/ml, IFN-γ at 100 ng/ml, human TGF-β1 at 1 ng/ml (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), or murine IFN-α at 100 units/ml (R & D Systems). For retroviral infection studies, purified CD43-depleted mature B cells were stimulated by 25 μg/ml LPS for 24 h, followed by infection by a T-bet-GFP (green fluorescent protein) or control-GFP retrovirus (12). Quantitation of serum Ig isotypes in serum or culture supernatants was performed as described (20). Germ-line and postswitch transcripts were determined by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR as described (21).

Plasmids and Electroporation.

Ig promoter reporter constructs were based on the firefly luciferase reporter vector pGL3-Basic (Promega). ɛ-Luciferase was generated by deleting the HS1,2 sites from GLɛ promoter-HS1,2-luc (22). γ2a-Luciferase was generated by replacing the HindIII-BglII promoter fragment of ɛ-luciferase with an ≈773-bp PstI-PstI genomic fragment from plasmid E1.6, corresponding to approximately −520/+253 with regard to the presumed first transcription start site of the Iγ2a exon (23). T-bet-expressing and control pCDNA3.1-based vectors have been described (12). Where indicated, the pCMV-Renilla luciferase plasmid (Promega) was used as an internal control. Electroporation was performed with 10–20 μg of supercoiled plasmid, 5 × 106 cells, a 0.4-cm cuvette, at 280 V and 975 μF in a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad). Luciferase activity was determined by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

PCR Primers.

Primers used in this study included D100673F, 5′-GCGAATGTTCCCATTCCTGTCCTTC; D100947R, 5′-GGGTCACATTGTTGGAAGCCCCCTTG; Tb-596F, 5′-TGGGCATACAGGAGGCAGCAACAAATA; Tb-314R, 5′-GACTGAAGCCCCGACCCCCACTCCTAAG; and PGKPR1220R, 5′-GCGCGAAGGGGCCACCAAAGAACGGAG.

Results and Discussion

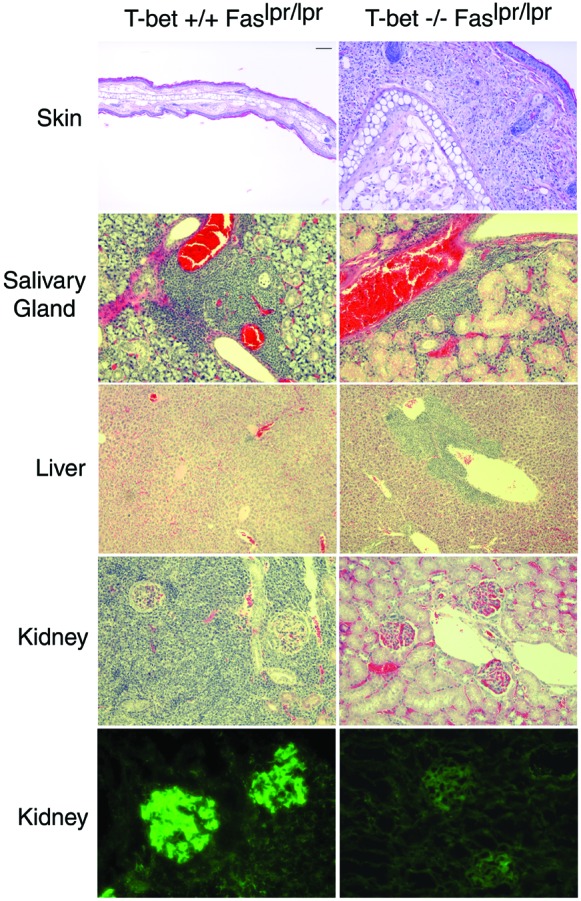

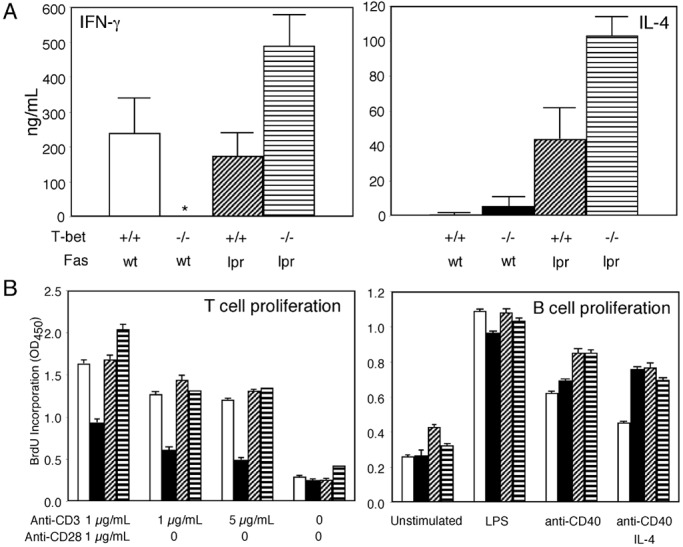

Lupus-prone T-bet-deficient mice were generated by intercrossing a T-bet-deficient line (14) with the MRL/MpJ-Fas(CD95)lpr/lpr murine lupus strain, generating animals of four genotypes, T-bet+/+Fas+/+, T-bet−/−Fas+/+, T-bet+/+Faslpr/lpr(T-bet+lpr), and T-bet−/−Faslpr/lpr(T-bet-lpr). Flow cytometric analyses of tissues from adult, 6-week-old animals revealed that T-bet did not have a significant effect on the proportional numbers of CD4 or CD8 T cells or B220-positive B cells in spleen or lymph node (ref. 14 and data not shown). Surprisingly, T-bet-lpr animals continued to develop manifestations consistent with T cell autoimmunity, including cutaneous, salivary gland, and hepatic infiltrates (Fig. 1) as well as lymphadenopathy (Fig. 2A), often in excess of their T-bet+lpr littermates. These lymphoid infiltrates consisted mostly of T cells, as assessed by immunohistochemistry (refs. 19 and 24, Fig. 1, and unpublished data). Such findings suggested to us that the Th1-dominant T cell autoimmunity in this model was largely intact in the absence T-bet. Indeed, although T-bet was required for the production of IFN-γ by naive CD4 T cells from CD95-intact animals, T-bet-lpr T cells produced excess cytokines, including IFN-γ and IL-4 (ref. 14; Fig. 3A), and demonstrated similar proliferative activity in an autologous mixed lymphocyte reaction, compared with their T-bet+lpr littermates (data not shown). This did not appear to reflect defects in apoptosis or proliferative capacity related to an interaction between T-bet and Fas-deficiency, because anti-CD3-mediated proliferation of purified naive CD4 T cells was comparable in T-bet+lpr and T-bet-lpr animals (Fig. 3B), and both genotypes of T cells underwent programmed cell death at similar rates when exposed to apoptogenic doses of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, UV irradiation, and dexamethasone (60% ± 5% vs. 60% ± 10%, 50% ± 10% vs. 45% ± 7%, and 72% ± 5% vs. 74% ± 3%, respectively, n = 3). Therefore, we concluded that T-bet was dispensable for T cell autoimmunity in this model of systemic disease.

Figure 1.

Role of T-bet in the autoimmune histopathology in lupus-prone mice. Indicated tissues from 12-week-old T-bet+/+Faslpr/lpr or T-bet−/−Faslpr/lpr animals were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For the bottom images, kidneys from respective mice were embedded frozen in OCT medium, sectioned, and stained with FITC–anti-mouse IgG antibody. Representative sections from eight animals examined from each genotype are shown. Clockwise from Upper Left, bar corresponds to 100 μm, 100 μm, 50 μm, 100 μm, 25 μm, 25 μm, 25 μm, 25 μm, 100 μm, and 50 μm.

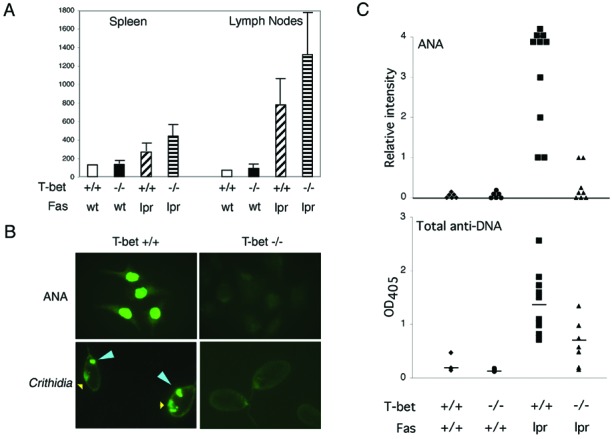

Figure 2.

Role of T-bet in serological and lymphoid manifestations of systemic autoimmunity. (A) Lymphoid organomegaly was assayed in 12-week-old animals of the indicated genotypes by total cell counts (in millions) of erythrocyte-depleted spleen and lymph nodes (n = 4–6 in each group). (B and C) Sera from 12-week-old animals of the indicated genotypes were assayed by the fluorescent antinuclear antibody test on Hep-2 substrates at 1:50 dilution and, for anti-DNA antibodies, by ELISA and Crithidia immunofluorescence. Yellow arrow indicates the Crithidia nucleus, where fluorescent staining indicates the presence of antinuclear antibody activity; blue arrow indicates the doubled-stranded DNA (dsDNA)-containing kinetoplast, where fluorescent staining specifically indicates the presence of anti-dsDNA activity. Some sera from T-bet−/−Faslpr/lpr animals displayed modest, generalized reactivity against DNA in a plate-bound ELISA assay, but all T-bet−/−Faslpr/lpr sera were negative for anti-dsDNA autoantibody activity as assayed by Crithidia. (n = 8–10 in each group.)

Figure 3.

T-bet is partially dispensable for cytokine production. (A) Cytokine production by T cells. Naive CD4+ T cells were purified from spleen and lymph nodes by negative selection (R & D Systems) and stimulated for 72 h in RPMI/10% with 1 μg/ml anti-murine CD28 (37.51) antibody and 1 μg/ml plate-bound anti-murine CD3 (145–2C11) antibody (PharMingen). Cytokine production was evaluated in culture supernatants by ELISA (PharMingen) from three to five 12-week-old animals of each genotype. (B) T and B cell proliferation. T and B cell proliferation was measured by BrdUrd incorporation (Amersham Pharmacia) on purified naive CD4 T cells or purified resting B cells, derived from three to five 12-week-old animals of each genotype, by using the stimulatory conditions indicated. BrdUrd incorporation was measured by pulsing cells at 48 h of stimulation, followed by assay at 72 h. *, Undetectable by assay (<2 ng/ml). Open bars, T-bet+/+Faswt/wt; solid bars, T-bet−/−Faswt/wt; diagonally hatched bars, T-bet+/+Faslpr/lpr; horizontally hatched bars, T-bet−/−Faslpr/lpr.

Just as surprising, however, T-bet-lpr animals nevertheless were protected from immune-complex renal disease, including strikingly diminished glomerular, interstitial and perivascular inflammation, as well as glomerular immune-complex deposition (Fig. 1 and unpublished data). Also, they developed significantly less humoral autoimmunity as assessed by the fluorescent antinuclear antibody test and two tests for anti-DNA antibodies (Fig. 2 B and C); their sera contained some, albeit diminished, autoimmunity to DNA as assessed by ELISA but were unable to recognize native, double-stranded DNA as assessed by Crithidia immunofluorescence, suggesting the presence of generalized (e.g., anti-single-stranded DNA), but not matured (e.g., anti-double-stranded DNA), autoimmunity in T-bet-lpr animals (25). Indeed, compared with T-bet+lpr animals, T-bet-lpr animals were relatively protected from glomerulonephritis-related mortality (survival of 57%, n = 7, vs. 100%, n = 6, at 28 weeks, respectively).

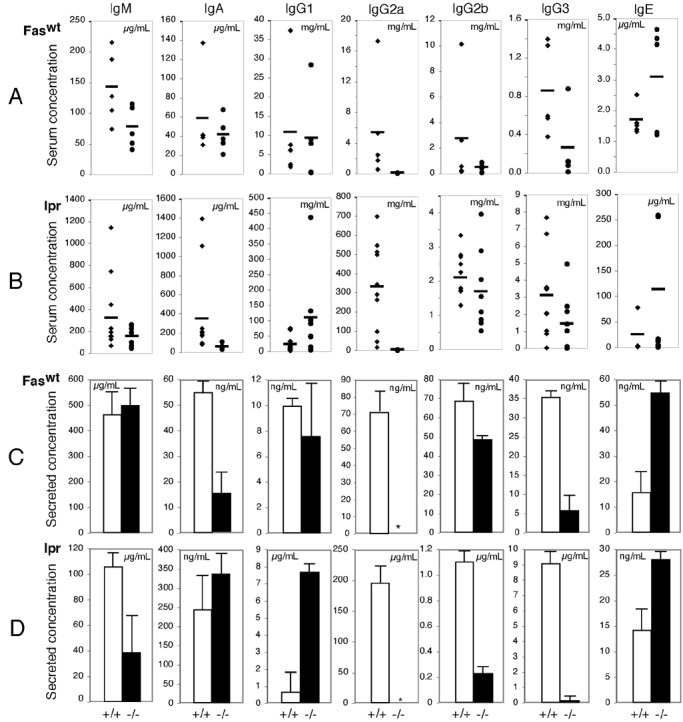

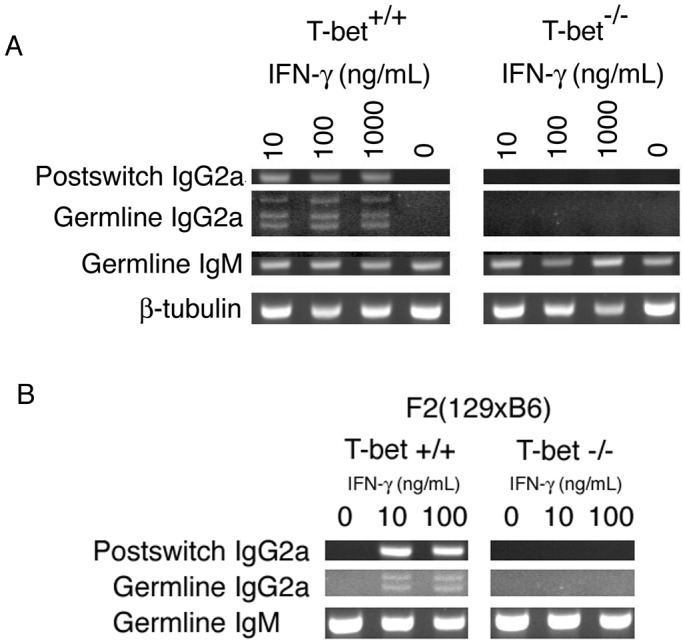

Because pathogenic autoantibodies are necessary and sufficient to induce immune-complex glomerulonephritis (26, 27) and T-bet is induced in both human and murine B cells upon activation (ref. 12 and data not shown), we investigated the possibility that T-bet is required directly in B lymphocyte function to account for our observations. As assessed by serum levels, T-bet was required for the complete expression in these lupus-prone animals of hypergammaglobulinemia of the IL-4-independent isotypes IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3, a requirement amplified in Faslpr/lpr animals (Fig. 4 A and B). Most strikingly, however, IgG2a levels were diminished severely in T-bet-deficient sera from either Fas genotype: IgG2a-immune deposits were reduced significantly in the kidneys of T-bet-lpr animals (data not shown), and purified T-bet-deficient B cells were unable to complete class switching to IgG2a when stimulated in vitro, as assayed by secreted Ig (Fig. 4 C and D). Class switching to IgG2b and IgG3 was diminished significantly but, nevertheless, present in T-bet-deficient cells. These deficits appeared to occur at the transcriptional level because, in class-switching assays, T-bet-deficient B cells neither were able to accumulate surface IgG2a nor generate germ-line or postswitch IgG2a transcripts (Fig. 5 and data not shown). Conversely, T-bet-deficient B cells produced excess amounts of the Th2-related isotypes IgG1 and IgE (Fig. 4). These deficits did not simply result from an unopposed effect of IL-4 (5, 28), because the addition of up to 10 μg/ml anti-mIL-4 antibodies to B cell cultures did not affect the IgG2a deficiency or the IgG1/IgE excess (not shown). Such observations suggest a profound role for T-bet in the regulation of IgG2a at the level of the germ-line transcript and further implicate it in the regulation of IgG1 and IgE.

Figure 4.

Ig production in T-bet-deficient mice. (A and B) Serum Ig isotype titers were evaluated on 12-week-old Faswt/wt (A) and Faslpr/lpr (B) animals of the indicated T-bet genotypes by ELISA. (C and D) In vitro class switching was assayed in 48-h culture supernatants from purified CD43-depleted B cells. Three Faswt/wt (C) and Faslpr/lpr (D) animals of indicated T-bet genotypes were assayed for Ig isotype production by ELISA. Stimulatory conditions included: IgM, IgA, IgG2b, and IgG3, LPS 25 μg/ml; IgG1 and IgE, anti-CD40 2 μg/ml + 10 ng/ml recombinant mouse (rm) IL-4; IgG2a, LPS 25 μg/ml + 100 ng/ml rmIFN-γ. *, Undetectable by assay (less than 20 pg/ml).

Figure 5.

T-bet is required for IgG2a isotype switching by resting B cells. (A) CSR transcripts in MRL B cells. Germ-line and postswitch class-switching transcripts were assayed by RT-PCR on total RNA purified from CD43-depleted Fas+ B cells stimulated for 96 h in RPMI/10% supplemented with 25 μg/ml LPS ± rmIFN-γ at the concentrations indicated, as described (21). (B) CSR transcripts in F2(129 × B6) B cells. Germ-line and postswitch class-switching transcripts were assayed by RT-PCR on total RNA purified from CD43-depleted B cells stimulated for 96 h in RPMI/10% supplemented with 25 μg/ml LPS ± rmIFN-γ at the concentrations indicated.

Accordingly, we sought further evidence that T-bet directly controls the transcription of IgG2a. Transfection of the murine pre-B cell lymphoma 18.81 with a T-bet expression plasmid induced endogenous IgG2a germ-line transcripts (Fig. 6A), and transduction of primary T-bet-deficient B cells by a T-bet-expressing retrovirus also conferred the ability to generate IgG2a germ-line transcripts (Fig. 6B) as well as secreted IgG2a (Fig. 6C). In addition, purified B cells from a CMV-T-bet transgenic mouse line, which expresses T-bet under the control of the CMV early promoter, produced increased amounts of IgG2a when stimulated in vitro with LPS and rmIFN-γ compared with B cells from nontransgenic littermates (490 ± 50 ng/ml vs. 1,058 ± 120 ng/ml, n = 3).

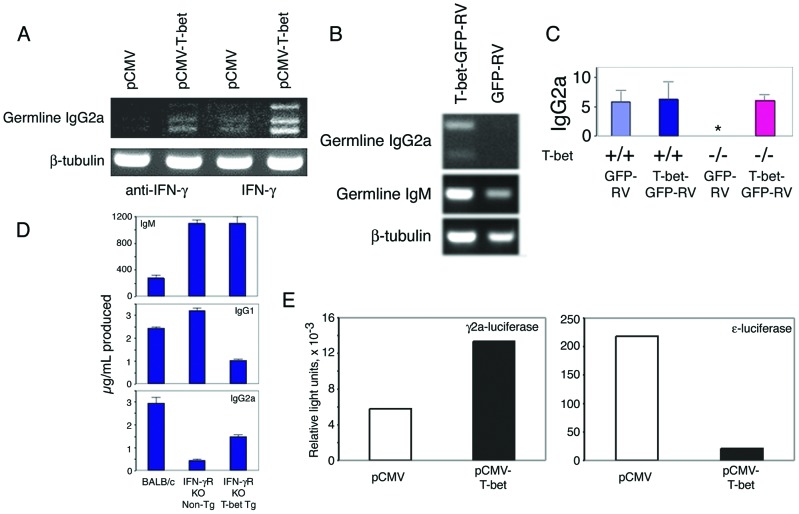

Figure 6.

T-bet-dependent regulation of IgG2a transcription. (A) 18.81 murine pre-B cells were transfected with a T-bet or control expression vector and assayed for the presence of germ-line IgG2a transcripts by RT-PCR on total RNA after 6 h in RPMI/10% supplemented with 100 ng/ml rmIFN-γ or 10 μg/ml neutralizing anti-IFN-γ antibody. (B) Purified CD43-depleted B cells from T-bet-deficient Faswt/wt mice were stimulated by 25 μg/ml LPS and 100 ng/ml rmIFN-γ for 24 h, transduced by a T-bet-GFP or control-GFP retrovirus, and assayed for the presence of germ-line IgG2a transcripts by RT-PCR on total RNA after 24 h of further incubation in medium containing 25 μg/ml LPS and 100 ng/ml rmIFN-γ. (C) Purified CD43-depleted B cells from T-bet+/+Faslpr/lpr and T-bet−/−Faslpr/lpr mice were stimulated by 25 μg/ml LPS for 24 h and transduced by a T-bet-GFP or control-GFP retrovirus, and the culture supernatant was assayed for secreted IgG2a after a further 48 h in medium containing 25 μg/ml LPS. (D) Class-switch assays were performed on purified CD43-depleted B cells from IFN-γR-deficient animals bearing a transgene that enforces T-bet expression under the control of the CMV promoter or IFN-γR-deficient, nontransgenic littermates. All cells were stimulated with 25 μg/ml LPS, supplemented with 10 ng/ml rmIL-4 for IgG1 and 100 ng/ml rmIFN-γ for IgG2a. Results from three animals in each group are shown; a BALB/c animal was used for comparison. (E) The ability of T-bet to transactivate germ-line IgG2a and IgE promoter–firefly luciferase constructs was tested in transient transfection assays in M12 cells. Cells were electroporated simultaneously with 10 μg of reporter plasmid, 10 μg of either control (pCMV) or T-bet-expressing (pCMV-T-bet) plasmids, and 0.2 μg of a pCMV-Renilla luciferase control expression plasmid. Firefly luciferase luminescence was determined upon whole-cell extracts within 6 h, normalized for Renilla luciferase. For IgG2a, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml rmIFN-γ; for IgE, cells were treated with 2 μg/ml anti-CD40 and 10 ng/ml rmIL-4. Ig promoter reporter constructs were based on the firefly luciferase reporter vector pGL3-Basic (Promega). ɛ-Luciferase was generated by deleting the HS1,2 sites from GLɛ promoter-HS1,2-luc (22). γ2a-Luciferase was generated by replacing the HindIII-BglII promoter fragment of ɛ-luciferase with an ≈773-bp PstI-PstI genomic fragment from plasmid E1.6, corresponding to approximately −520/+253 with regard to the presumed first transcription start site of the Iγ2a exon (23). Electroporation was performed by using 10–20 μg of supercoiled plasmid, 5 × 106 cells, 0.4-cm cuvette, at 280 V, 975 μF in a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad). Luciferase activity was determined by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Shown is a single experiment, representative of three.

Because IFN-γ alone can induce endogenous IgG2a germ-line transcripts in 18.81 cells (Fig. 6A, lane 3) and given the relationship between T-bet and IFN-γ expression (12–14), we wondered whether T-bet played a role specifically in the IFN-γ-signaling pathway that induces IgG2a expression (23). Indeed, T-bet expression alone was sufficient to induce germ-line IgG2a transcripts in the absence of exogenous IFN-γ (Fig. 6A, lane 2), and, although we could not detect significant levels of IFN-γ in 18.81 cells transfected by a T-bet-expressing plasmid, as assayed by real-time RT-PCR analysis (not shown), we could not absolutely rule out the possibility that its effects were secondary to the induction of IFN-γ. Therefore, we crossed the CMV-T-bet transgenic line upon an IFN-γR-deficient background (15): again, T-bet was able to augment the production of IgG2a, this time in the absence of IFN-γ signaling (Fig. 6D). The proliferative capacity of T-bet-deficient B cells (Fig. 3A) as well as their ability to up-regulate several markers of B cell activation, including IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (not shown), was unaffected in vitro, further suggesting a direct role for T-bet in the regulation of IgG transcription, independent of B cell activation status.

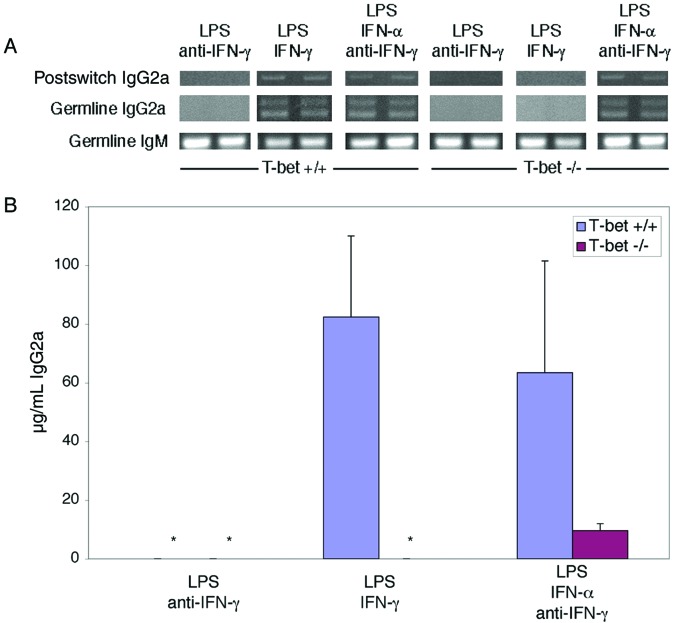

Despite these dramatic findings, T-bet was not absolutely required for IgG2a class switching in vivo, because T-bet-deficient animals nevertheless produced detectable serum IgG2a levels, albeit significantly reduced in comparison with T-bet+ littermates (Fig. 4 and data not shown). In addition, T-bet deficiency did not alter spontaneous IgG2a levels as dramatically in animals of a wild-type (mixed C57BL/6 × 129) compared with the MRL background (ref. 14 and data not shown). Such observations suggest the importance of an IFN-γ-dependent, T-bet-dependent pathway in the genesis of pathological hypergammaglobulinemia in MRL animals yet indicate further that other IFN-γ-independent and, therefore, T-bet-independent pathways also can induce IgG2a class switching. One such attractive mechanism includes type I interferons, which have been demonstrated to induce class switching to IgG2a in an IFN-γ-independent fashion (29–31). Indeed, we noted that T-bet-deficient B cells could produce some IgG2a in response to IFN-α but not to IFN-γ (Fig. 7), albeit less than wild-type B cells.

Figure 7.

IFN-α can induce IgG2a in a T-bet-independent fashion. Germ-line and postswitch IgG2a transcripts were assayed by RT-PCR (A) and IgG2a levels were measured by ELISA (B) on culture supernatant of purified CD43-depleted B cells from T-bet+/+Faswt/wt and T-bet−/−Faswt/wt mice stimulated by 25 μg/ml LPS for 96 h, supplemented with 100 ng/ml rmIFN-γ, 10 μg/ml neutralizing anti-IFN-γ, and/or 100 units/ml rmIFN-α as indicated. In A, duplicate studies performed simultaneously are shown. In B, data represent three animals in each group. *, undetectable by assay (<20 pg/ml).

T-bet therefore confers upon B lymphocytes the ability to class switch to IgG2a in response to IFN-γ and appears to play a significant, albeit less critical, role in the regulation of other Ig isotypes and the response to other class-switch-inducing cytokines, nevertheless playing a major role in the regulation of pathogenic autoantibody production. The identification of T-bet as a regulator of IgG isotype class switching may prove helpful in future transcriptional analyses of the non-IL4-dependent IgG subclasses, whose study has been hindered greatly by their apparently very distant locus control regions (32–35). Given its role as a transcription factor (refs. 12 and 13 and unpublished data), T-bet likely regulates class switching via control of germ-line transcripts (Figs. 4–7), which have been implicated strongly as a prerequisite to isotype-switch recombination (36–40). Alternatively, T-bet may participate in mediating accessibility of the IgG locus to transcriptional or recombinatorial factors, as it does for IFN-γ in CD4 T cells (13). Accordingly, a T-bet-expressing plasmid can transactivate an IgG2a promoter luciferase reporter but, instead, represses an IgE promoter reporter in M12 cells (Fig. 6E). Considering, though, that complete wild-type-level production of IgG2a appears to require IFN-γ signaling (Fig. 6D), such findings suggest that additional factors, such as STAT1 (41), cooperate with T-bet in the regulation of germ-line Ig transcripts and also imply that a control region(s) for IgG2a, at least as it relates to T-bet, may be quite distant.

Regardless, these data support a model in which T-bet serves as a mediator of signals to transactivate the classical IFN-γ-related Ig isotype IgG2a yet inhibit the classical Th2-related isotypes IgG1 and IgE, analogous to the role of STAT6 in the isotype-switch response to IL-4 (42). Therefore, these findings are of particular significance given the complete yet selective absence of IgG2a germ-line transcripts in the T-bet-deficient B cells, because, in comparison, several reported Ig isotype immunodeficiencies caused by other transcription factor knockouts involve multiple Ig isotypes (43, 44) and/or other developmental B cell defects (45, 46). These results identify T-bet as an isotype-specific participant in the class-switch mechanism.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dorothy Zhang for assistance with histopathology; Kirsten Sigrist for assistance with transgenic animal development; Wes Dunnick for the 18.81 cell line, IgG2a promoter, 3′α Ig enhancer HS1,2 and HS3,4 constructs, and the use of the unpublished IgG2a promoter–reporter construct pXYCAT; and Eva Severinson for the germ-line IgE promoter–luciferase construct. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (to L.H.G. and S.L.P.) and a grant from the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation (to L.H.G.).

Abbreviations

- CSR

class-switch recombination

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- RT

reverse transcription

- IFN-γR

IFN-γ receptor

References

- 1.Snapper C M, Finkelman F D. In: Fundamental Immunology. Paul W E, editor. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1999. pp. 831–861. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacharier L B, Geha R S. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:S547–S558. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snapper C, Marcu K B, Zelazowski P. Immunity. 1997;6:217–223. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntyre T M, Klinman D R, Rothman P, Lugo M, Dasch J R, Mond J J, Snapper C M. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1031–1037. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snapper C M, Paul W E. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snapper C M, McIntyre T M, Mandler R, Pecanha L M, Finkelman F D, Lees A, Mond J J. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1367–1371. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gavalchin J, Seder R A, Datta S K. J Immunol. 1987;138:128–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gyotoku Y, Abdelmoula M, Spertini F, Izui S, Lambert P H. J Immunol. 1987;138:3785–3792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas C, Ryffel B, Le Hir M. J Immunol. 1997;158:5484–5491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi S, Fossati L, Iwamoto M, Merino R, Motta R, Kobayakawa T, Izui S. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1597–1604. doi: 10.1172/JCI118584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balasa B, Sarvetnick N. Immunol Today. 2000;21:19–23. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szabo S J, Kim S T, Costa G L, Zhang X, Fathman C G, Glimcher L H. Cell. 2000;100:655–669. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullen A C, High F A, Hutchins A S, Lee H W, Villarino A V, Livingston D M, Kung A L, Cereb N, Yao T P, Yang S Y, et al. Science. 2001;292:1907–1910. doi: 10.1126/science.1059835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szabo S J, Sullivan B M, Stemmann C, Satoskar A R, Sleckman B P, Glimcher L H. Science. 2002;295:338–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang S, Hendriks W, Althage A, Hemmi S, Bluethmann H, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Zinkernagel R M, Aguet M. Science. 1993;259:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.8456301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singer G G, Abbas A K. Immunity. 1994;1:365–371. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kageyama Y, Koide Y, Yoshida A, Uchijima M, Arai T, Miyamoto S, Ozeki T, Hiyoshi M, Kushida K, Inoue T. J Immunol. 1998;161:1542–1548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green N S, Rabinowitz J L, Zhu M, Kobrin B J, Scharff M D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6304–6308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng S L, Madaio M P, Hughes D P, Crispe I N, Owen M J, Wen L, Hayday A C, Craft J. J Immunol. 1996;156:4041–4049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng S L, Gerth A J, Ranger A M, Glimcher L H. Immunity. 2001;14:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laurencikiene J, Deveikaite V, Severinson E. J Immunol. 2001;167:3257–3265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins J T, Dunnick W A. Int Immunol. 1993;5:885–891. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.8.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng S L, Madaio M P, Hayday A C, Craft J. J Immunol. 1996;157:5689–5698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aarden L A, de Groot E R, Feltkamp T E. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1975;254:505–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb29197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madaio M P, Carlson J, Cataldo J, Ucci A, Migliorini P, Pankewycz O. J Immunol. 1987;138:2883–2889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shlomchik M J, Madaio M P, Ni D, Trounstein M, Huszar D. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1295–1306. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coffman R L, Carty J. J Immunol. 1986;136:949–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkelman F D, Svetic A, Gresser I, Snapper C, Holmes J, Trotta P P, Katona I M, Gause W C. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1179–1188. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Broek M F, Muller U, Huang S, Aguet M, Zinkernagel R M. J Virol. 1995;69:4792–4796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4792-4796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Bon A, Schiavoni G, D'Agostino G, Gresser I, Belardelli F, Tough D F. Immunity. 2001;14:461–470. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cogne M, Lansford R, Bottaro A, Zhang J, Gorman J, Young F, Cheng H L, Alt F W. Cell. 1994;77:737–747. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lieberson R, Ong J, Shi X, Eckhardt L A. EMBO J. 1995;14:6229–6238. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins J T, Dunnick W A. J Immunol. 1999;163:5758–5762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinaud E, Khamlichi A A, Le Morvan C, Drouet M, Nalesso V, Le Bert M, Cogné M. Immunity. 2001;15:187–199. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lutzker S, Rothman P, Pollock R, Coffman R, Alt F W. Cell. 1988;53:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stavnezer J, Radcliffe G, Lin Y C, Nietupski J, Berggren L, Sitia R, Severinson E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7704–7708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jung S, Rajewsky K, Radbruch A. Science. 1993;259:984–987. doi: 10.1126/science.8438159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Bottaro A, Li S, Stewart V, Alt F W. EMBO J. 1993;12:3529–3537. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bottaro A, Lansford R, Xu L, Zhang J, Rothman P, Alt F W. EMBO J. 1994;13:665–674. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Venkataraman C, Leung S, Salvekar A, Mano H, Schindler U. J Immunol. 1999;162:4053–4061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Linehan L A, Warren W D, Thompson P A, Grusby M J, Berton M T. J Immunol. 1998;161:302–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snapper C M, Zelazowski P, Rosas F R, Kehry M R, Tian M, Baltimore D, Sha W C. J Immunol. 1996;156:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su G H, Chen H M, Muthusamy N, Garrett-Sinha L A, Baunoch D, Tenen D G, Simon M C. EMBO J. 1997;16:7118–7129. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liao F, Birshtein B K, Busslinger M, Rothman P. J Immunol. 1994;152:2904–2911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nutt S L, Heavey B, Rolink A G, Busslinger M. Nature (London) 1999;401:556–562. doi: 10.1038/44076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]