Abstract

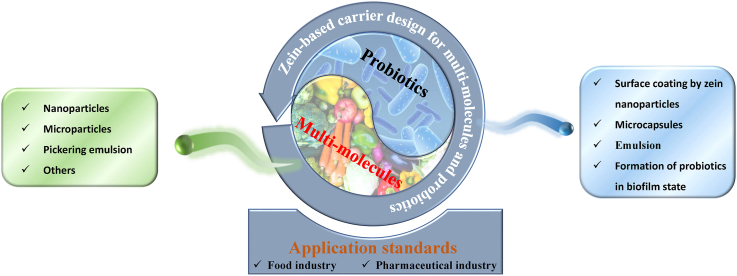

Zein is an excellent carrier material for active substances. Previous reviews have mainly focused on the encapsulation of single active molecules, while this review is for the first time to comprehensively review the design of multi-molecules and probiotics carriers, and summarize its application standards. For multi-molecule encapsulation, zein nanoparticles with core-shell structure are widely used. Based on the difference in fabrication methods and physicochemical properties of active molecules, zein nanoparticles were categorized into mixed/isolated encapsulation. Besides, zein microparticles and Pickering emulsions (with two-compartment structures for different active molecules) stabilized by zein nanoparticles as multi-molecule delivery platforms are also discussed. For carrier design of probiotics, the methods include layer-by-layer self-assembly/complex coacervation based on zein nanoparticles, microcapsules, emulsion, and probiotic biofilm formation based on zein fibers. Importantly, zein has different criteria in the food/pharmaceutical industry, which is a prerequisite for practical application. Although zein-based multi-molecule carriers have been studied extensively, most of the current work focuses on characterizing properties instead of mechanism investigation of complex systems. In the future, designing carriers with superior structures to control the release rate of different molecules and targeted colonic delivery of probiotics are the main challenges for expanding zein applications. This review is expected to guide the rapid and scientific progress of zein-based carrier design for multi-molecules and probiotics.

Keywords: Zein, Carrier, Multi-molecules, Probiotics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Zein nanoparticles are divided into mixed/isolated encapsulation for multi-molecules.

-

•

Zein-based carriers have remarkable designs for encapsulating probiotics.

-

•

Standards of zein in the food/pharmaceutical industry are summarized.

1. Introduction

Bioactive substances, including molecules (curcumin, quercetin, etc) and probiotics, have been proven to provide diverse health benefits to the body (Chen et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2024), while the application of which is limited by various harsh environmental stresses. Currently, encapsulation is considered an effective strategy for protecting these environmentally sensitive components (Virk et al., 2025; Yao et al., 2021). Compared with synthetic materials, encapsulation based on natural materials is more accepted by consumers, one of which is zein. The unique protein structure (self-assembly properties) of zein makes it an ideal carrier for the encapsulation of bioactive molecules (Ren et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2023).

For a long time, extensive research has been conducted on encapsulation based on zein, mainly in carrier design for single active molecules: (1) Zein-based nanoparticles and their emulsion-based carriers are prepared to encapsulate single active molecules. Owing to the instability of zein nanoparticles, coating with other wall materials on their surface is usually required to construct composite nanoparticles, such as our previous reports (Ma et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2020, 2021a, 2021b). (2) Benefiting from the proposal of electrospinning technology, nanofibers based on zein are fabricated to encapsulate single active molecules (Li et al., 2024; Moradinezhad et al., 2024; Radünz et al., 2022; Weng et al., 2023).

Currently, the reviews on zein-based carrier design mainly focus on its encapsulation for single active molecules and the food application (Feng et al., 2025; Han et al., 2024; Lan et al., 2023; Yuan et al., 2022). With the development of carrier technology and the demand of consumers for effective utilization of multiple health benefits, zein-based carrier design for multi-molecules and probiotics is gradually becoming a research hotspot. However, there is no comprehensive review focusing on this perspective.

Unlike single active molecules, multi-molecules have different carrier design ideas due to differences in solubility, structure, and functional groups. The ability to encapsulate multiple substances with different biological activities simultaneously in the same delivery system provides a unique advantage over single encapsulation (Dissanayake and Bandara, 2024). Combinations of different active ingredients with complementary effects like curcumin and resveratrol have shown improved stability by protecting each other from oxidative degradation (Huang et al., 2019). It has also been reported that the incorporation of one active substance can increase the encapsulation rate of another active substance (Chen et al., 2023). The incorporation of multiple bioactive compounds with different functions into the same product can reduce the content of a single substance thereby enhancing nutritional and health and improving sensory attributes. In addition, the rate of release of different actives can be controlled by modifying the structure of the delivery system. Besides, probiotics are micrometer-sized cells, which not only have the influence of volume space but also require unique carrier designs due to their survival sensitivity. Therefore, it is of great guiding significance to re-examine zein-based carrier design from the perspective of encapsulating multi-molecules and probiotics. In addition, although there have been reports on the application of zein-based carriers in foods, there is currently no review summarizing the standards for its application in the food and pharmaceutical industries in various countries and regions, which is a prerequisite for its practical application. This is also summarized in this review.

2. Multi-molecule encapsulation

Multi-molecule encapsulation refers to encapsulating two or more active molecules in the same carrier (Liu et al., 2022; Misra et al., 2021). The main reason for proposing this development direction is based on the synergistic effects between active substances (Buniowska-Olejnik et al., 2023; Faucher et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2020). However, owing to differences in physicochemical properties between different active substances, the wall material may favor binding to one compound over another (Chen et al., 2019a). Competition between compounds may result in less efficient encapsulation of all compounds. Therefore, the encapsulation of them in the same carrier is challenging. The maturity of the research on single active compound encapsulation based on zein provides a strong research foundation for co-encapsulation of active substances. Therefore, research on zein-based multi-molecule encapsulation has gradually been reported in recent years.

2.1. Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles are the main multi-molecule encapsulation carrier form based on zein, the small size of the nanoparticles allows for fuller contact with the intestinal mucosa, which has a longer gastrointestinal retention time and promotes the accumulation and uptake of bioactive in the gastrointestinal tract (Yang et al., 2024). Core-shell structures based on zein for multi-molecule delivery systems have been widely reported (Han et al., 2024; Tadele et al., 2025). And the amphiphilic zein is often used as the core of nanoparticles to encapsulate hydrophobic substances. However, nanoparticles based on zein tend to aggregate near the isoelectric point (6.2) and under high ionic strength conditions, limiting their application in functional foods (Tadele and Mekonnen, 2024). Therefore, various strategies have been proposed for improving the chemical stability of zein nanoparticles and broadening the range of bioactive compounds, which include surface modification (Yin et al., 2014), surface coating (Yuan et al., 2022a), and utilization of emulsifier/surfactant (Zheng et al., 2018). Among them, the formation of surface coating in zein nanoparticles mainly by electrostatic interactions is the most commonly used strategy, with the coating providing spatial/electrostatic repulsion to hinder aggregation. It is also this special structure that enables the encapsulation of multi-molecules in the same delivery system. The active substance can be located in different regions of the core-shell system: within the hydrophobic core of the zein nanoparticles or in the weakly hydrophobic region between the hydrophobic core and the coating. Therefore, this chapter can be divided into mixed multi-molecule encapsulation and isolated multi-molecule encapsulation based on the distribution of bioactive molecules in the nanoparticles during the preparation process (Table 1).

Table 1.

Multi-molecule encapsulation based on zein nanoparticles.

| Encapsulation type | Coating material | Encapsulated multi-molecules | Preparation method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed multi-molecule encapsulation | K+ cross-linked κ-carrageenan | Coenzyme Q10 and piperine | Antisolvent precipitation | Chen et al. (2020d) |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose | Quercetin and resveratrol | Antisolvent precipitation | (Yang et al., 2022, 2023) | |

| Pectin | Tannic acid and resveratrol | Antisolvent precipitation | Liang et al. (2022) | |

| Caseinate | Puerarin, resveratrol, diosmetin, and curcumin | Antisolvent precipitation | Chen et al. (2022) | |

| Alginate and chitosan | Phenolic acids, glycosylated flavonoids, and flavonoid aglycones | Antisolvent precipitation | Carrasco-Sandoval et al. (2021) | |

| DNA and DNA-quercetin complexes | Kaempferol and α-tocopherol | Antisolvent precipitation | Ji et al. (2023) | |

| – | Quercetin and α-tocopherol | Antisolvent co-precipitation | Tadele et al. (2024) | |

| Hydroxypropyl beta-cyclodextrin | Curcumin and quercetin | Antisolvent co-precipitation | Qiu et al. (2023) | |

| Bovine serum albumin | Curcumin and resveratrol | pH-driven | Chen et al. (2023) | |

| Soy protein isolate | Curcumin and diosmetin | pH-driven | Yu et al. (2023) | |

| Polyethylene glycol or ethyl cellulose | Curcumin and resveratrol | Co-axial electrospraying | Leena et al. (2022) | |

| Gum arabic | Vitamins B6 and B12 | Anti-solvent evaporation | Karoshi et al. (2024) | |

| Chondroitin | Egg white-derived peptides and quercetin | / | Ma et al. (2025) | |

| Mesona chinensis polysaccharides | Resveratrol and curcumin | Antisolvent precipitation | Yang et al. (2024) | |

| κ-carrageenan | Curcumin and piperine | / | Chen et al. (2020b) | |

| Isolated multi-molecule encapsulation | Chitosan | Curcumin and resveratrol | Antisolvent precipitation/layer-by-layer self-assembly | Chen et al. (2020a) |

| Pectin and chitosan | Coenzyme Q10 and piperine | Antisolvent precipitation/layer-by-layer self-assembly | Chen et al. (2020c) | |

| Chitosan | Curcumin and berberine | Antisolvent precipitation/layer-by-layer self-assembly | Ghobadi-Oghaz et al. (2022) | |

| κ-carrageenan | Anthocyanin and cinnamaldehyde | Antisolvent precipitation/layer-by-layer self-assembly | Zhou et al. (2024) | |

| Bovine serum albumin or caseinate | Curcumin and quercetin | Antisolvent precipitation/pH driven | Chen et al. (2024b) | |

| Chitosan | Caffeic acid and folic acid | Template sacrifice/electrostatic deposition | Wusigale et al. (2021) | |

| Propylene glycol alginate | Resveratrol and coenzyme Q10 | Emulsification evaporation | Wei et al. (2020) | |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose | Quercetin and resveratrol | Antisolvent precipitation/layer-by-layer self-assembly | Chen et al. (2024a) | |

| Hyaluronic acid | Curcumin and Piperine | Antisolvent precipitation/layer-by-layer self-assembly | Chen et al. (2019b) |

2.1.1. Mixed multi-molecule encapsulation

The commonly used methods for preparing zein-based nanoparticles can achieve multi-molecule encapsulation. Some factors that affect multi-molecule encapsulation need to be noted. The hydrophobic amino acid composition of prolamin and polarity of active substances can affect the encapsulation capacity (Chen et al., 2022). Therefore, this section discusses in detail the methods for fabricating mixed multi-molecular encapsulations.

2.1.1.1. Antisolvent precipitation/co-precipitation

The combination of antisolvent precipitation and electrostatic deposition is the mainstream method for preparing zein-based core-shell nanoparticles, and the same applies to the construction of multi-molecule encapsulated nanoparticles. However, the method is applicable to most alcohol-soluble polyphenols and two polyphenols may compete for binding sites on zein, resulting in less efficient encapsulation compared to single encapsulation. Recently, Chen et al. (2020d) prepared zein nanoparticles coated by K+ cross-linked κ-carrageenan by an antisolvent precipitation method to encapsulate coenzyme Q10 and piperine (Fig. 1A), and the authors found that a better carrier of synergistic nutrients could be achieved by K+ cross-linked nanoparticles and the release of nutrients could be delayed during in vitro digestion. Besides, Liang et al. (2022) fabricated zein nanoparticles coated by pectin using the antisolvent precipitation method to encapsulate tannic acid and resveratrol with encapsulation efficiencies of 51.5 % and 77.2 %, and the authors found that a better antioxidant activity than ascorbic acid was presented by co-encapsulated tannic acid and resveratrol. The reason may be that the tannic acid and resveratrol complement each other through different reaction sites and electron donor capabilities, forming a synergistic effect; tannic acid has a fast-free radical scavenging rate, reduces the concentration of free radicals in the system, minimizes the structural damage of resveratrol under oxidative stress, indirectly preserves its reducing ability, thereby enhancing overall reaction capacity and stability. Coating of hydrophilic polysaccharides to address the aggregation of zein due to surface hydrophobicity. Incorporation of carboxymethyl cellulose coating resulted in highly negative charge (−50 mV) of zein nanoparticles and no aggregation/precipitation of the multi-molecules delivery system in the pH range of 3–6 (Chen et al., 2024a; Yang et al., 2023). In addition, the pectin coating imparts stable anti-aggregation properties to encapsulated hydrophilic tannic acid and hydrophobic resveratrol of zein nanoparticles when heated at 80 °C for 2h/less than 50 mM NaCl/pH of 2–8 conditions (Liang et al., 2022). The antisolvent co-precipitation method can also achieve co-encapsulation proven by recent reports (Tadele and Mekonnen, 2024). However, it is worth noting that the antisolvent co-precipitation method requires the simultaneous precipitation of different substances to form a homogeneous complex, which makes the system complicated, but it also makes it possible to modulate the formation of multiple structures.

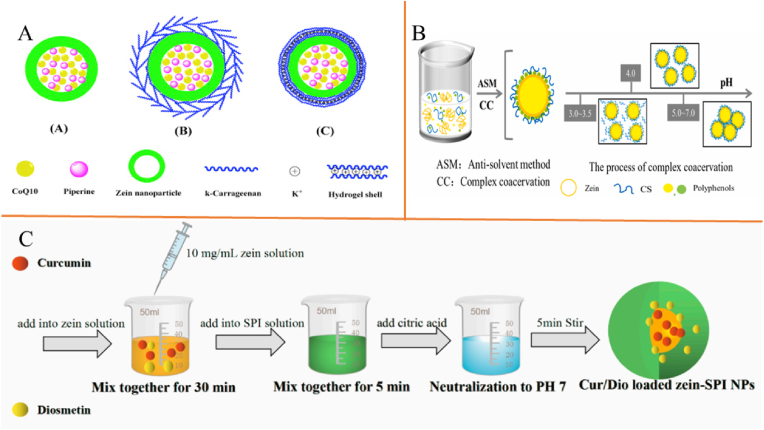

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagrams of mixed multi-molecule encapsulation based on zein nanoparticles. A, Coenzyme Q10/piperine-loaded zein nanoparticles coated by K+ cross-linked κ-carrageenan (Chen et al., 2020d); B, pH regulates the particle size of particles with core-shell structure (Ma et al., 2023); C, Curcumin/diosmetin-loaded zein nanoparticles coated by soy protein isolate (Yu et al., 2023). SPI is soy protein isolate. NPs are nanoparticles.

Changes in pH can alter the charged properties of core-shell structural complexes and affect the intermolecular interactions which in turn modulate the complex particle size. As shown in Fig. 1B, at pH 3–6.5, the zein/chitosan complexes co-encapsulating curcumin and quercetin had particle sizes of 150–300 nm and showed good stability, whereas at pH 7, the electrostatic repulsion of the complexes decreased and aggregation (particle size of 4000 nm) occurred to form a composite cohesive layer (Ma et al., 2023). This reveals that changing environments can lead to the formation of delivery systems different from those of nanocomplexes, which also suggests that the environmental stability of complexes with core-shell structures needs to be further improved. However, the use of cross-linkers further improves the stability of the coated zein nanoparticles. The external cross-linker is located outside the nanocomplex and it can regulate the particle size of the nanocomplexes with the help of different concentrations. Whereas, the internal cross-linker is located inside the nanocomplex to increase the cross-linking of the coating and the hydrophobic core. The internal cross-linkers are mainly potassium ions and calcium ions, and adjusting the ion concentration can effectively change the degree of cross-linking of the nanocomplexes and thus the particle size. The low concentration of ions (4 mmol/L for potassium ions and 2 mmol/L for calcium ions) promotes cross-linking of κ-carrageenan to form a dense coating and thus reduces the particle size of the nanocomplexes, whereas the high concentration of ions promotes cross-linking of κ-carrageenan on different nanoparticles and thus promotes aggregation (Chen et al., 2020b, 2020d). The binding of polydopamine to zein (hydrophobic core) and whey proteins (coating) helps to form a stable core-shell structure, which protects quercetin from any pro-oxidants in the aqueous environment. However, this approach is not currently used in multi-molecule delivery systems (Zhang et al., 2024). Interestingly, the presence of Ca2+ improved the encapsulation efficiency, antioxidant activity, and stability of these bioactive substances by promoting crosslinking of protein, electrostatic screening, and binding effects (Qiu et al., 2023).

2.1.1.2. pH-driven method

The pH-driven method, another novel preparation method for zein-based nanoparticles, has also been proven to apply to the construction of multi-molecule encapsulation carriers. Alkaline condition fully unfolds the protein structure and exposes the binding sites, allowing the active substance to fully interact with the zein, which is subsequently adjusted to a neutral pH environment for protein self-assembly to form nanoparticles. Therefore, it has been shown that the pH-driven method has a significant encapsulation rate compared to the antisolvent precipitation (Chen et al., 2023). The main reason is that the conformational change of the protein under alkaline conditions increases the number of binding sites between the active substance and the zein nanoparticles. However, the pH-driven method could not regulate the position of the active substance in the nanoparticles i.e. different active substances could only be in the same region and the approach is only applicable to chemically stable bioactive compounds that are soluble under alkaline conditions like curcumin and resveratrol. For example, as presented in Fig. 1C, the pH-driven method was used to prepare zein/soy protein isolate composite nanoparticles to encapsulate curcumin and diosmetin (Yu et al., 2023).

In summary, the incorporation of the coating layers can significantly increase the encapsulation efficiency of some active substances, such as phenolic acids and glycosylated flavonoids (Carrasco-Sandoval et al., 2021). Moreover, the addition of an active substance may promote the improvement of the performance of another active substance. For example, quercetin could form complexes with DNA to act as the coating layer of zein particles, and the presence of quercetin (as an antioxidant barrier) improved the stability of α-tocopherol encapsulated by zein particles (Ji et al., 2023). Interestingly, mixed multi-molecule encapsulated nanoparticles have been proven to be applied to 3D-printed hydrogel for consumer-preferred customized structures (Leena et al., 2022). In addition, multi-molecule delivery systems have the potential to enhance pharmacokinetics and enable site-targeted delivery. Co-encapsulated drugs based on zein nanoparticles show increased pharmacological activity compared to single drugs (Campos et al., 2024; Celano et al., 2022). The zein-based co-delivery oral systems for targeted colonic drug delivery are the preferred strategy for the treatment of ulcerative colitis (Ma et al., 2025; Yang et al., 2024).

2.1.2. Isolated multi-molecule encapsulation

At present, the methods used for isolated multi-molecule encapsulation include antisolvent precipitation/layer-by-layer self-assembly, antisolvent precipitation/pH driven, and template sacrifice/electrostatic deposition.

For the method of antisolvent precipitation/layer-by-layer self-assembly, Chen et al. (2020a) prepared curcumin-loaded zein nanoparticles by antisolvent precipitation method, then coated by resveratrol and chitosan using layer-by-layer assembly, and the results showed that the use of low molecular weight chitosan exhibited an excellent encapsulation efficiency of curcumin (91.3 %) and resveratrol (82.1 %). Layer-by-layer assembly techniques can immobilize bioactives at different locations and can effectively protect and release the bioactives. Positively and negatively charged biopolymers can be sequentially deposited around nanoparticles to modulate interfacial properties depending on the delivery requirements (Chen et al., 2024a). The rate of gastrointestinal release can be adjusted by adjusting the position of active substances in the nanoparticles as well as varying the number of coatings and the materials used to form the outermost coating (Chen et al., 2019b, 2020c).

For the method of antisolvent precipitation/pH driven, Chen et al. (2024b) prepared curcumin-loaded bovine serum albumin (BSA) or caseinate nanoparticles by pH-driven method, and then the obtained nanoparticles were coated on the surface of quercetin-loaded zein nanoparticles that fabricated by antisolvent precipitation method, and the results showed the different effects for the encapsulation, release, and stability against the harsh environment. The coating materials significantly affect the properties of the delivery system due to differences in binding strength and binding sites. Zein-BSA nanoparticles have small particle sizes and excellent encapsulation capabilities while zein-caseinate nanoparticles have excellent environmental stability (thermal/ionic stability) (Chen et al., 2024b).

Hard-template-assisted strategies enable the fabrication of hollow-structured materials characterized by desirable features such as large specific surface area, reduced density, and enhanced loading capacity. This approach involves filling a removable template with the target material, followed by template elimination to yield a hollow interior (Ren et al., 2025). Calcium-containing compounds such as calcium phosphate and calcium carbonate are widely utilized as sacrificial templates for fabricating hollow structures capable of encapsulating biomacromolecules, pharmaceuticals, and genetic materials (Volodkin, 2014). Their popularity stems from excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability, ease of synthesis under pH-regulated conditions, cost-effectiveness, and the ability to decompose under mild conditions, such as slightly acidic environments or in the presence of chelating agents like EDTA (Volodkin, 2014). For the method of template sacrifice/electrostatic deposition, Wusigale et al. (2021) prepared hollow zein particles using a sacrificing template (calcium phosphate) to encapsulate caffeic acid, and folic acid interacted with chitosan to form complexes that coated on the zein particles. The authors found that the photostability of both active substances was improved compared with the encapsulation of a single compound (Wusigale et al., 2021).

In summary, the main reason for the design of isolated multi-molecule encapsulation is that the significant differences in the polarity of active molecules make it difficult to co-encapsulate effectively, such as the co-encapsulation of hydrophobic and hydrophilic active molecules. In addition, isolated multi-molecule encapsulated nanoparticles can be further loaded into the film for monitoring and preserving the freshness of food, such as fish (Zhou et al., 2024). zein is a good material for the encapsulation of hydrophobic substances, but systems for the delivery of hydrophilic substances can also be constructed to improve the physicochemical properties and bioavailability of active substances (Karoshi et al., 2024; Wusigale et al., 2021).

2.2. Microparticles

Generally, drying powder microparticles were proposed to store and transport effectively, and spray drying is a common method based on its advantages of continuous high yield and low cost (Altay et al., 2024; Laein et al., 2024). A recent study has shown that microparticles can achieve multi-molecule encapsulation based on zein. As shown in Fig. 2A, Tchuenbou-Magaia et al. (2022) co-encapsulated vitamin D3 and rutin within chitosan-zein microparticles (<10 μm) via antisolvent precipitation and spray drying, and the results showed that the encapsulation efficiency of vitamin D3 and rutin was 75 % and 44 %, respectively.

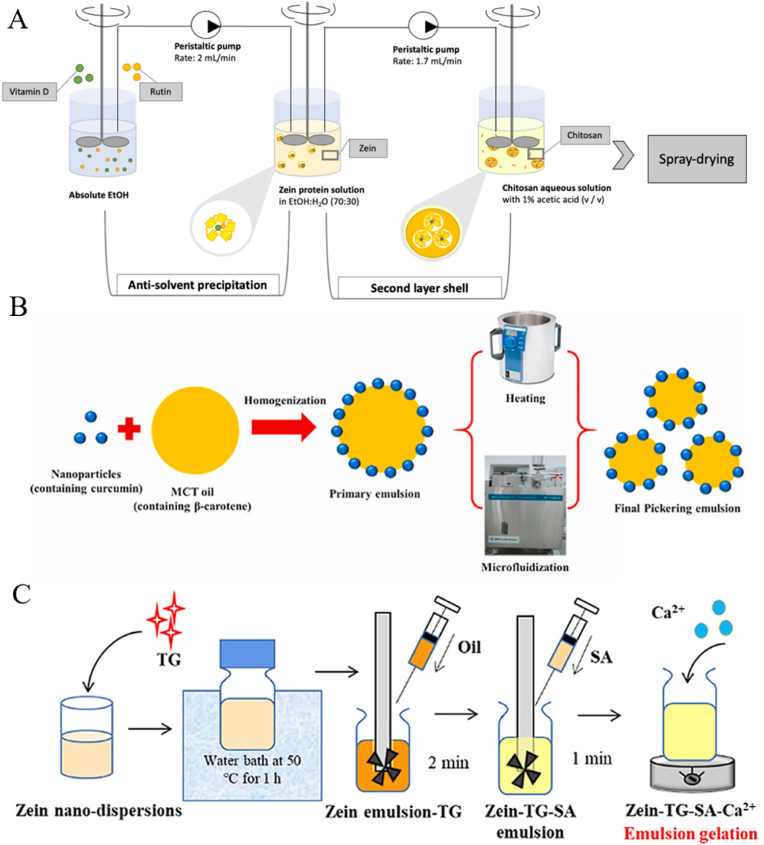

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagrams of multi-molecule encapsulation based on zein microparticles (A) (Tchuenbou-Magaia et al., 2022), (B) Pickering emulsion (Wei et al., 2022), and (C) emulsion gel (Yan et al., 2021). TG is transglutaminase. SA is sodium alginate.

Considering that the purpose of spray drying is to dehydrate to form particles and the heating stress of this process on thermosensitive substances, other drying methods such as electrospraying (Jayaprakash et al., 2023) and the addition of high melting point oils such as shortening oil (Yin et al., 2024a, Yin et al., 2024b; Yin et al., 2024) may achieve better results in the future. Electrospraying is a liquid atomization technique driven by electrostatic forces (Pires et al., 2024). In this process, a liquid is delivered through a capillary nozzle held at high voltage, causing the liquid to break up into fine, charged droplets under the influence of an external electric field (Lo et al., 2025). A typical electrospray system comprises four key components: a fluid delivery mechanism, a capillary nozzle, a high-voltage power supply (typically ranging from 1 to 30 kV, operating in DC or AC modes), and a grounded collector plate (Jayaprakash et al., 2023). When voltage is applied, the liquid at the nozzle tip forms a cone-like structure known as the Taylor cone. From this cone, highly charged droplets are emitted and travel toward the grounded collector due to electrostatic attraction. As the droplets accumulate charge, electrostatic repulsion gradually overcomes the cohesive surface tension. When this balance reaches the Rayleigh limit, Coulomb fission occurs, resulting in the droplet's disintegration into several smaller, less charged particles (Nguyen, Clasen, & Van den Mooter, 2016). High melting point oils refer to oils that are solid at room temperature and liquid after heating, such as 60 °C. This oil, such as shortening oil, can effectively absorb heat during the heat stress process of spray drying, which can protect heat-sensitive active substances.

2.3. Pickering emulsion

As a novel delivery system, Pickering emulsions enable synergistic delivery of multi-molecules for synergistic functions. Currently, the two-compartment structure is the main model, i.e., emulsion and nanoparticles that stabilize the emulsion encapsulate different actives. Generally, the interface stabilizers of zein-based Pickering emulsion are zein nanoparticles (Ren et al., 2025; Song et al., 2022). Recently, Wei et al. (2022) prepared β-carotene-loaded Pickering emulsion stabilized by curcumin-loaded zein nanoparticles coated by propylene glycol alginate and tea saponin (Fig. 2B), and the authors found that a synergistic effect on the photothermal stability of β-carotene and curcumin was presented by co-encapsulation. It should be noted that different particle concentrations, microfluidic pressure, and heating temperature may affect the physicochemical properties of compounds co-encapsulated by Pickering emulsion (Wei et al., 2022).

2.4. Others

Emulsion gel is a gel with emulsion as a template and cross-linked biopolymer using a cross-linking agent. As presented in Fig. 2C, it is reported that a double-cross-linked emulsion gel could encapsulate curcumin and resveratrol, a Pickering emulsion was used as a template, zein was cross-linked by transglutaminase and sodium alginate was cross-linked by Ca2+ (Yan et al., 2021). The authors found that the emulsion gel with double-cross-linking gave higher light stability and bioaccessibility than the ones with single-cross-linking (Yan et al., 2021). Curcumin/anthocyanins encapsulated in the hydrogel based on zein/sodium alginate provide wider color variations over the pH response range and can be used as an effective colorimetric hydrogel for differentiating meat freshness (Du et al., 2025).

Zein fibers, prepared usually by electrospinning technique, can co-encapsulate bioactive substances (Wang et al., 2021). For example, EGCG and vitamin B12 could be co-encapsulated in zein fibers by electrospinning technique and the results showed that the increase in polymer concentration is associated with the increase in release time (Couto et al., 2023).

Some emerging platforms can provide the possibility for effective encapsulation and delivery of multiple molecules. Integrating DNA with proteins enables the construction of well-organized nanostructures that exhibit sophisticated functionalities, potentially mimicking or even outperforming natural nucleoprotein assemblies in their biological roles (Hernandez-Garcia, 2021). Therefore, DNA nanostructure-zein hybrids may be an excellent strategy. Phage-display targeted carrier is a nanoparticle or delivery system like zein-based carrier that is decorated with specific targeting ligands—these ligands were discovered using phage display, a technique to find molecules that bind tightly and specifically to a certain target (like a cancer cell receptor) (Jahandar-Lashaki et al., 2024). This platform can provide new ideas for multi-molecule intelligent delivery based on zein.

3. Encapsulation of probiotics

The premise for probiotics to exert health benefits is to reach the colon in an active state (Nezamdoost-Sani et al., 2023; Yuan et al., 2022b). However, probiotics are sensitive to the environment. During food processing, the probiotics can be damaged by the pH, freeze-drying, heating stress, etc.; During the storage, water activity, water content, temperature, and other factors can affect the survival of probiotics; During the gastrointestinal tract, probiotics can be stressed by gastric acid and bile salts (Han et al., 2024; Wang and Zhong, 2024; Yin et al., 2022). Therefore, the consumption of commercial probiotics faces multiple challenges. Encapsulation has been proven to be an effective strategy for overcoming this challenge (Amiri et al., 2024; Nezamdoost-Sani et al., 2024; Virk et al., 2024; Zhong et al., 2024). Currently, the main wall materials for probiotic encapsulation are proteins and polysaccharides (Yuan et al., 2022). Compared to other proteins and polysaccharides like alginate and whey protein isolate, the application of zein in the encapsulation of probiotics is relatively lacking. The reason may be related to the specificity of its solubility i.e. the methods (antisolvent precipitation and co-precipitation) used in zein encapsulation require ethanol which damages the probiotics. It is difficult to choose low-toxicity solvent alternatives for ethanol-sensitive probiotics, as probiotics are also sensitive to other organic solvents, acids, and bases. However, in recent years, several reports have emphasized the feasibility and advantages of zein in the encapsulation of probiotics, expanding new perspectives and worthy of attention.

3.1. Surface coating by zein nanoparticles

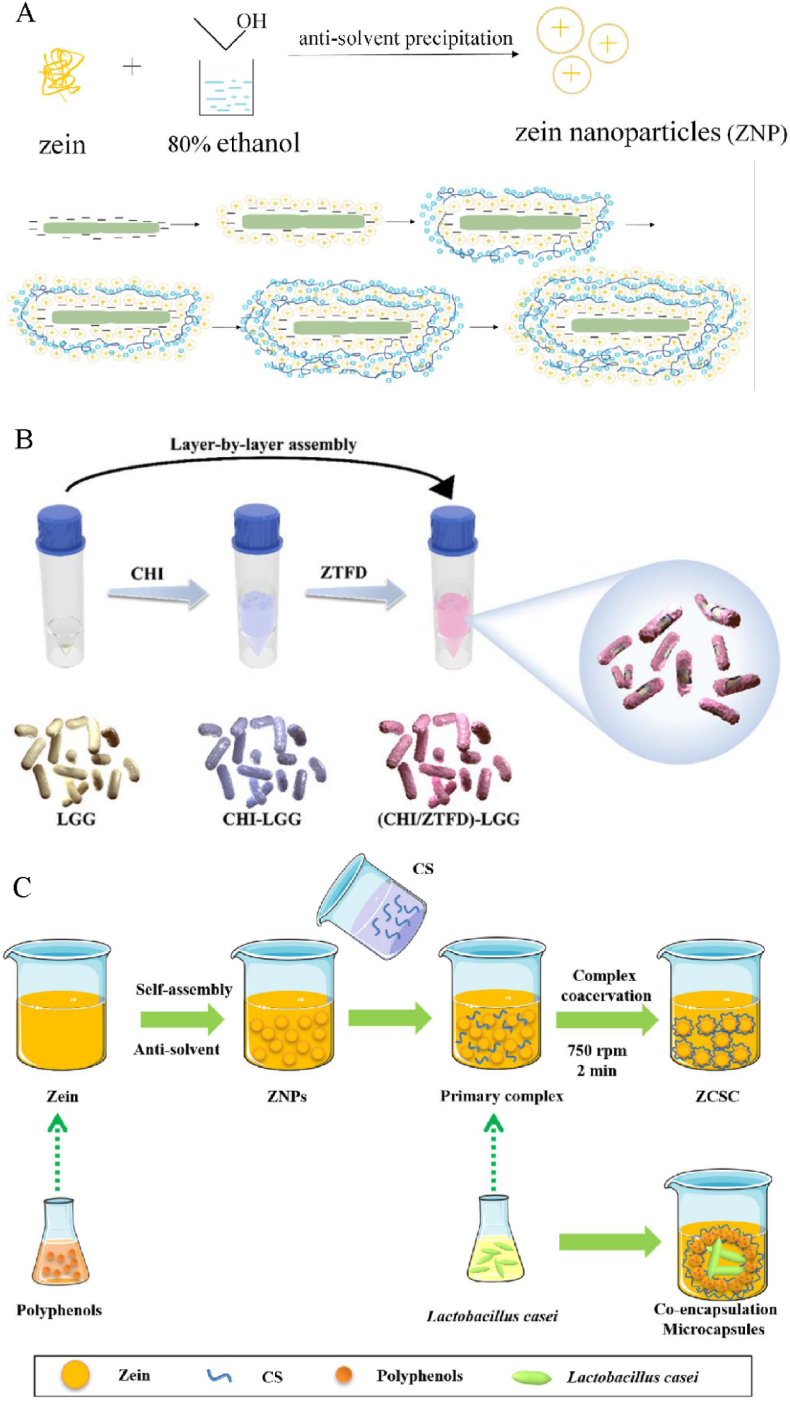

Probiotics are micrometer-sized cells, mostly rod-shaped. Therefore, unlike active molecules, zein-based nanoparticles generally cannot encapsulate them. However, recent studies have shown that zein-based nanoparticles can adsorb on the surface of probiotics, similar to film, to encapsulate probiotics and improve the survival of probiotics. For example, Liu et al. (2023) prepared zein nanoparticles by antisolvent precipitation, then alternated with pectin to adsorb on the surface of probiotics based on electrostatic attraction (Fig. 3A). The authors found that the number of coating layers affected the survival of probiotics against external adverse conditions, pectin as the outmost layer improved the survival of probiotics during heating, while zein nanoparticles as the outmost layer improved the storage survival of probiotics (Liu et al., 2023). Similarly, as shown in Fig. 3B–Lei et al. (2024) fabricated zein/tween-80/fucoidan composite nanoparticles, then the probiotics were coated layer by layer with chitosan and these composite nanoparticles, and the results showed that two bi-layer coated probiotics exhibited improved survival in vitro when compared with free probiotics, and the enhanced probiotic effects were confirmed by in vivo mice (encapsulated probiotics showed 63.7-fold increase in survival compared to plain probiotics). Besides, Cheng et al. (2024) prepared zein nanoparticles coated by soluble soybean polysaccharide through antisolvent precipitation at pH 6.0, which were used to form a hydrophobic shell around Bacillus subtilis to improve its protection. The authors found that the resulting Bacillus subtilis showed a 3.13-fold protection ability than free cells for gastrointestinal digestion, 3.20-fold for pasteurization at 65 °C for 30 min, and 1.50-fold for storage at 4 °C. Interestingly, oral administration of the resulting Bacillus subtilis improved the beneficial gut bacteria abundance. The application of this encapsulation method in food has also been explored, and it has shown good survival protection of probiotics and food sensory effects, such as yogurt (Kiran et al., 2023).

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagrams of encapsulation of probiotics based on zein nanoparticles. A, layer-by-layer assembly using zein nanoparticles and pectin (Liu et al., 2023); B, layer-by-layer assembly using chitosan and zein/tween-80/fucoidan nanoparticles (Lei et al., 2024), CHI is chitosan, LGG is Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG, ZTFD is zein/tween-80/fucoidan nanoparticles; C, bilayer microencapsulation based on complex coacervation reaction of zein and chitosan (Ma et al., 2024), CS is chitosan, ZNPs are zein nanoparticles, ZCSC are zein-chitosan complex coacervates.

Encapsulation of probiotics based on zein nanoparticles can achieve co-encapsulation with active molecules. As shown in Fig. 3C–Ma et al. (2024) prepared polyphenols-loaded zein nanoparticles and then formed complex coacervation with chitosan to encapsulate probiotics, and the results showed that quercetin increased the encapsulation rate of probiotics over 16.89 %, and co-encapsulated probiotics showed better stability in complex coacervates, such as gastric digestion stability and storage stability. For this encapsulation system, the binding of zein and chitosan was dependent on their pH; electrostatic interactions were strengthened with the increased pH, resulting in the formation of larger particles with a weak positive charge that could weakly electrostatically adsorb probiotics (Ma et al., 2024). Meanwhile, hydrogen bonding was confirmed within the complex coacervates (Ma et al., 2024). Importantly, the co-encapsulation carriers could act as a fermenting agent to prepare flavored fermented milk with multiple functions (Ma et al., 2024). The co-encapsulation of probiotics and active molecules can exert their synergistic effects (Ma et al., 2025), which is a key focus of surface coating of probiotics by zein nanoparticles in the future.

3.2. Microcapsules

Microcapsules of probiotics involve encapsulating a large number of cells in the wall material to form micrometer-sized particles. Recently, Zeng et al. (2024) prepared Lactiplantibacillus plantarum microcapsules using skim milk powder, alginic acid, trehalose, and zein based on the phase separation method. The authors found that the encapsulated Lactiplantibacillus plantarum showed a higher in vitro survival rate than free cells, and it exhibited a controlled release ability. Notably, these microcapsules showed the colonization ability in the intestinal tract of mice, and ameliorated gut microbiota imbalance related to depression, including the intestine inflammation and hippocampus inflammation of mice with depression. Specifically, at the genus level, significant changes in a total of 51 genera following the establishment of the chronic restraint stress models, while the changes in 13 genera were reversed with the involvement of encapsulated Lactiplantibacillus plantarum; Inflammatory factors, including TNF in hippocampus, TNF in intestine, and IL-6 in intestine, decreased from about 40, 27, 30 mg/g (free probiotics group) to 30, 20, 22 mg/g (encapsulated probiotics group), respectively (Zeng et al., 2024). Therefore, microcapsules of probiotics based on zein have the potential for application in the pharmaceutical field, indicating the importance of zein as a wall material for probiotics.

3.3. Emulsion

The emulsion is a common form of probiotic encapsulation, and zein has recently been successfully applied to its wall material. For example, Zhou et al. (2021) reported a pH value-adjusted method to fabricate Pickering high internal phase emulsion with zein particles, and the resulting emulsion was used to encapsulate Lactobacillus plantarum, improving its survival at 4 °C. Furthermore, Xu et al. (2024) fabricated zein nanoparticles stabilized by pectin, which were used to stabilize W/O/W emulsion for the encapsulation of Lactobacillus plantarum 23–1. And the resulting W/O/W emulsion could improve the survival rate of Lactobacillus plantarum 23–1 during storage (survival rate of 78.42 % for 35 days at 4 °C) and gastrointestinal tract (survival rate of 73.36 %). Currently, emulsion has been developed into various types, and zein has promising application potential due to its properties. More emulsion used to encapsulate probiotic based on zein should be constructed in the future for a wider range of food applications.

3.4. Formation of probiotics in biofilm state

Probiotics in biofilm state refer to a highly organized microbial community encapsulated by extracellular polymers and are considered the most advanced fourth-generation probiotics (Hu et al., 2022). Probiotics in biofilm state have attracted attention for their ability to exhibit more advantages than free probiotics, one of which is their resistance to harsh environments, thereby improving the survival of probiotics, which belongs to the spontaneous encapsulation method (Gao et al., 2022). Therefore, the researchers consider how to enrich the probiotics in biofilm state. In addition to the in situ re-culture based on hydrogel (Yuan et al., 2023), the main basic principle is porous adsorption and colonization of probiotics, such as water-insoluble dietary fiber (Liu et al., 2021; Rajasekharan et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2024). In recent years, zein fibers based on this principle have also been found to promote the formation of probiotics in biofilm state (Fig. 4), enabling them to be encapsulated in extracellular polymers to increase their resistance (He et al., 2024; Hu et al., 2023).

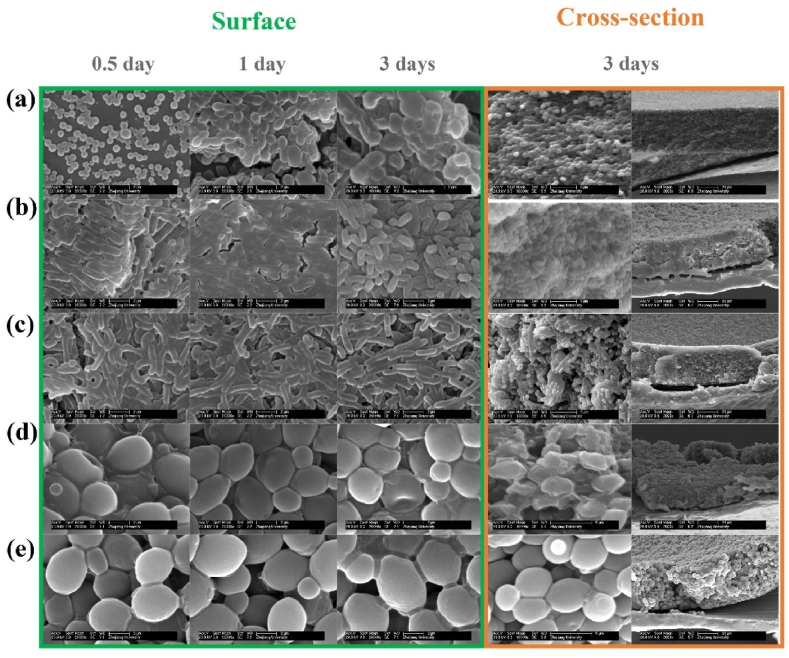

Fig. 4.

SEM images of biofilms formed in zein nanofibrous scaffolds: (a) S. thermophilus, (b) Bifidobacterium, (c) L. paracasei, (d) S. cerevisiae N85, and (e) S. cerevisiae 321 (Hu et al., 2023). The time is culture time of probiotics.

4. Application standards

4.1. Food industry

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies zein as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) for use in food applications such as coatings for fruits, vegetables, and confectionery, as well as in food packaging. This means that zein does not require pre-market approval but must comply with 21 CFR 184.1400, which outlines the criteria for GRAS substances. The substance must meet safety and purity standards to ensure it is free from contaminants and does not pose any health risks. Similarly, in the European Union (EU), the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) evaluates food ingredients and additives, though zein is not specifically listed as an approved additive. However, it is subject to safety assessments if used in food products, ensuring that it complies with the EU General Food Law (Regulation (EC) No 178/2002), which mandates that all food sold in the market must be safe for consumption. Zein's use in food contact materials, including packaging and coatings, must also comply with EU Food Contact Materials Regulation (EC) No 1935/2004, ensuring that it does not migrate harmful substances into food. In China, zein is regulated by the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) and must conform to the GB2760-2014 standard, which governs food additives. If used in food coatings or packaging, zein must meet the GB 4806.1–2016 standards for food contact materials, ensuring safety and compliance with national food safety regulations. Overall, the use of zein in food across various regions is governed by strict regulations to ensure its safety and effectiveness as an ingredient or material.

4.2. Pharmaceutical industry

In the pharmaceutical industry, zein is primarily used as an excipient in drug formulations, especially for tablet coatings and controlled-release systems, due to its film-forming and biocompatible properties. In the United States, the FDA regulates zein as an excipient under the Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) guidelines, which ensure that zein meets the necessary standards for purity, safety, and quality. Zein must comply with USP (United States Pharmacopoeia) standards for excipients, which outline specifications for excipient quality, including limits for contaminants and compatibility with active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Additionally, any pharmaceutical product containing zein must undergo rigorous testing to ensure it does not interfere with the therapeutic effects of the drug. In the European Union, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) oversees the use of excipients like zein in drug formulations, ensuring compliance with European Pharmacopoeia standards. Zein must meet strict criteria for purity, stability, and safety, particularly when used in controlled-release tablets or capsules. The excipient must also meet the regulatory requirements outlined in the EMA's Guideline on Excipients and be manufactured according to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). In China, the use of zein as an excipient is regulated by the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) and must comply with Chinese Pharmacopoeia (ChP) standards. The NMPA ensures that zein meets the safety, purity, and quality criteria set forth for excipients, and all drug products containing zein must undergo a rigorous approval process. Overall, the application of zein in pharmaceuticals is tightly regulated in all regions to ensure its safety, compatibility, and effectiveness in drug formulations.

5. Challenges, perspectives, and future trends

Zein-based delivery systems hold promising potential for the co-encapsulation of multi-molecules and probiotics. However, realizing this potential requires overcoming several scientific and practical challenges. Future research should not only explore technical solutions but also broaden the scope of applications to meet the complex demands of the food and nutrition industries. The following five key directions are expected to shape the evolution of this field.

-

(1)

Innovation in carrier architecture: Beyond single-molecule systems

While zein carriers have been well explored for individual bioactive molecules, the encapsulation of multiple components—such as hydrophilic/hydrophobic molecules or probiotic-bioactive molecules combinations—demands novel carrier architectures. Multi-compartmental, core–shell, and hierarchical structures may offer spatial separation, stability, and controlled interactions, opening up possibilities for customized delivery in diverse food matrices.

-

(2)

Elucidating multi-molecule encapsulation mechanisms

Unlike single-molecule systems, co-encapsulation involves intricate molecular interactions among the encapsulants and the carrier. Understanding these interactions—whether synergistic, antagonistic, or competitive—is critical. Future studies should focus on mechanism-driven design using tools like molecular docking to rationalize and optimize encapsulation efficiency and release behavior.

-

(3)

Achieving precise spatial-temporal release and synergistic function

A major goal of multi-molecule encapsulation is to enhance synergistic bioactivities (e.g., antioxidant/anti-inflammatory combinations). This requires carriers that enable spatial separation of actives and programmable release kinetics. Smart design strategies—such as stimulus-responsive linkers, region-specific degradation, or gradient-based structures—should be developed to fine-tune the co-release behavior and maximize functional synergy at target sites.

-

(4)

Engineering integrated probiotic–bioactive molecule systems

The co-encapsulation of probiotics with functional molecules (e.g., polyphenols, peptides, vitamins) represents a frontier with strong health implications. Yet, the stability and viability of probiotics alongside bioactive protection remain a challenge. Future work should focus on designing protective microenvironments within zein-based carriers, ensuring mutual stabilization, and enabling co-delivery under harsh gastrointestinal or food processing conditions.

-

(5)

Bridging laboratory design and real food applications

Most current evaluations of zein-based systems occur under simplified laboratory settings. However, food matrices present dynamic and complex environments (e.g., pH variability, enzymatic activity, temperature shifts). Future studies must establish robust testing protocols in real or simulated food systems to assess carrier performance, sensory compatibility, and regulatory compliance. Real-world validation is critical for commercial translation.

6. Conclusion

This paper reviews the latest progress in zein-based carrier design for multi-molecules and probiotics. The main carrier types of multi-molecule encapsulation are nanoparticles, microparticles, and Pickering emulsion. Multi-molecule encapsulation based on zein nanoparticles can be divided into mixed multi-molecule encapsulation and isolated multi-molecule encapsulation based on the distribution of active substances in the nanoparticles during the preparation process. The methods for mixed multi-molecule encapsulation mainly include antisolvent precipitation, antisolvent co-precipitation, and pH-driven. The performance of mixed multi-molecule encapsulated carriers may be affected by the hydrophobic amino acid composition of zein, the polarity of active substances, surface coating of zein nanoparticles, additional active ingredients, etc. The methods used for isolated multi-molecule encapsulation include antisolvent precipitation/layer-by-layer self-assembly, antisolvent precipitation/pH-driven, and template sacrifice/electrostatic deposition. The methods for encapsulation of probiotics include layer-by-layer self-assembly/complex coacervation based on zein nanoparticles, microcapsules, emulsion, and biofilm formation based on zein fibers. Zein-based carriers need to comply with industry standards when applied in different countries and regions. In the future, innovation in carrier architecture, elucidating multi-molecule encapsulation mechanisms, achieving precise spatial-temporal release/synergistic function, engineering integrated probiotic–bioactive molecule systems, and bridging laboratory design and real food applications should be focused on. Zein has broad development prospects in the construction of multi-molecule and probiotic carriers.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Defeng Shu: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Yueyue Liu: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Jinlong Xu: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Yongkai Yuan: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflict of interest exists in the submission of this manuscript, and the manuscript is approved by all authors for publication. I would like to declare on behalf of my co-authors that the review has not been published previously, and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part. All the authors listed have approved the manuscript that is enclosed.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Altay Ö., Köprüalan Ö., İlter I., Koç M., Ertekin F.K., Jafari S.M. Spray drying encapsulation of essential oils; process efficiency, formulation strategies, and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024;64(4):1139–1157. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2113364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri S., Nezamdoost-Sani N., Mostashari P., McClements D.J., Marszałek K., Mousavi Khaneghah A. Effect of the molecular structure and mechanical properties of plant-based hydrogels in food systems to deliver probiotics: an updated review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024;64(8):2130–2156. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2121260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buniowska-Olejnik M., Urbański J., Mykhalevych A., Bieganowski P., Znamirowska-Piotrowska A., Kačániová M., Banach M. The influence of curcumin additives on the viability of probiotic bacteria, antibacterial activity against pathogenic microorganisms, and quality indicators of low-fat yogurt. Front. Nutr. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1118752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos L.A.d.A., Neto A.F.S., Scavuzzi A.M.L., Lopes A.C.D.S., Santos-Magalhães N.S., Cavalcanti I.M.F. Ceftazidime/tobramycin Co-Loaded chitosan-coated zein nanoparticles against antibiotic-resistant and biofilm-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pharmaceuticals. 2024;17(3):320. doi: 10.3390/ph17030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Sandoval J., Aranda-Bustos M., Henríquez-Aedo K., López-Rubio A., Fabra M.J. Bioaccessibility of different types of phenolic compounds co-encapsulated in alginate/chitosan-coated zein nanoparticles. Lwt. 2021;149 [Google Scholar]

- Celano M., Gagliardi A., Maggisano V., Ambrosio N., Bulotta S., Fresta M., Russo D., Cosco D. Co-Encapsulation of paclitaxel and JQ1 in zein nanoparticles as potential innovative nanomedicine. Micromachines. 2022;13(10):1580. doi: 10.3390/mi13101580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Chen Z., Zhong Q. Caseinate nanoparticles co-loaded with quercetin and avenanthramide 2c using a novel two-step pH-driven method: formation, characterization, and bioavailability. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;129 [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Xu W., Yang Z., McClements D.J., Peng X., Xu Z., Meng M., Zou Y., Chen G., Jin Z. Co-encapsulation of quercetin and resveratrol: Comparison in different layers of zein-carboxymethyl cellulose nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;278 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Han Y., Huang J., Dai L., Du J., McClements D.J., Mao L., Liu J., Gao Y. Fabrication and characterization of layer-by-layer composite nanoparticles based on zein and hyaluronic acid for codelivery of curcumin and quercetagetin. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11(18):16922–16933. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b02529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Han Y., Jian L., Liao W., Zhang Y., Gao Y. Fabrication, characterization, physicochemical stability of zein-chitosan nanocomplex for co-encapsulating curcumin and resveratrol. Carbohyd. Polym. 2020;236 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Li Q., McClements D.J., Han Y., Dai L., Mao L., Gao Y. Co-delivery of curcumin and piperine in zein-carrageenan core-shell nanoparticles: formation, structure, stability and in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;99 [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., McClements D.J., Jian L., Han Y., Dai L., Mao L., Gao Y. Core–shell biopolymer nanoparticles for Co-Delivery of curcumin and piperine: sequential electrostatic deposition of hyaluronic acid and chitosan shells on the zein core. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11(41):38103–38115. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b11782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zhang Y., Han Y., McClements D.J., Liao W., Mao L., Yuan F., Gao Y. Fabrication of multilayer structural microparticles for co-encapsulating coenzyme Q10 and piperine: effect of the encapsulation location and interface thickness. Food Hydrocollioids. 2020;109 [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zhang Y., Qing J., Han Y., McClements D.J., Gao Y. Core-shell nanoparticles for co-encapsulation of coenzyme Q10 and piperine: surface engineering of hydrogel shell around protein core. Food Hydrocollioids. 2020;103 [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Wang Z.-X., Zhang Y., Liu W., Hao-Song Z., Wu Y.-C., Li H.-J. Caseinate vs bovine serum albumin on stabilizing zein nanoparticles for co-entrapping quercetin and curcumin. Colloid. Surface. A. 2024;683 [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Wu Y.-C., Liu Y., Qian L.-H., Zhang Y.-H., Li H.-J. Single/Co-Encapsulation capacity and physicochemical stability of zein and foxtail millet prolamin nanoparticles. Colloid. Surface. B. 2022;217 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yu C., Zhang Y., Wu Y.-C., Ma Y., Li H.-J. Co-encapsulation of curcumin and resveratrol in zein-bovine serum albumin nanoparticles using a pH-driven method. Food Funct. 2023;14(7):3169–3178. doi: 10.1039/d2fo03929j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C., Sun M., Wang L., Wang H., Li L., Yang Q., Zhao Y., Chen W., Wang P. Zein and soy polysaccharide encapsulation enhances probiotic viability and modulates gut microbiota. Lwt. 2024;210 [Google Scholar]

- Couto A.F., Favretto M., Paquis R., Estevinho B.N. Co-encapsulation of epigallocatechin-3-Gallate and vitamin B12 in zein microstructures by electrospinning/electrospraying technique. Molecules. 2023;28(6):2544. doi: 10.3390/molecules28062544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake T., Bandara N. Protein-based encapsulation systems for codelivery of bioactive compounds: recent studies and potential applications. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2024;57 [Google Scholar]

- Du S., Xia Q., Sun Y., Wu Z., Deng Q., Ji J., Pan D., Zhou C. The fabrication and intelligent evaluation for meat freshness of colorimetric hydrogels using zein and sodium alginate loading anthocyanin and curcumin: stability and sensitivity to pH and volatile amines. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025;309 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.142889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucher P., Dries A., Mousset P., Leboyer M., Dore J., Beracochea D. Synergistic effects of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG, glutamine, and curcumin on chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depression in a mouse model. Benef. Microbes. 2022;13(3):253–264. doi: 10.3920/BM2021.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z., Shao B., Yang Q., Diao Y., Ju J. The force of zein self-assembled nanoparticles and the application of functional materials in food preservation. Food Chem. 2025;463 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.141197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Sadiq F.A., Zheng Y., Zhao J., He G., Sang Y. Biofilm-based delivery approaches and specific enrichment strategies of probiotics in the human gut. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1) doi: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2126274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghobadi-Oghaz N., Asoodeh A., Mohammadi M. Fabrication, characterization and in vitro cell exposure study of zein-chitosan nanoparticles for co-delivery of curcumin and berberine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022;204:576–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L., Zhu J., Jones K.L., Yang J., Zhai R., Cao J., Hu B. Fabrication and functional application of zein-based core-shell structures: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;272 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M., Yang S., Song J., Gao Z. Layer-by-layer coated probiotics with chitosan and liposomes demonstrate improved stability and antioxidant properties in vitro. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;258 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F., Ma X.-K., Tu C.-K., Teng H., Shao X., Chen J., Hu M.-X. Lactobacillus reuteri biofilms formed on porous zein/cellulose scaffolds: synbiotics to regulate intestinal microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;262 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Garcia A. Strategies to build hybrid Protein–DNA nanostructures. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(5):1332. doi: 10.3390/nano11051332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M.-X., He F., Tu C.-K., Chen Z.-X., Teng H., Shao X., Ren G.-R., Guo Y.-X. Edible electrospun zein nanofibrous scaffolds close the gaps in biofilm formation ability between microorganisms. Food Biosci. 2023;56 [Google Scholar]

- Hu M.X., He F., Zhao Z.S., Guo Y.X., Ma X.K., Tu C.K., Teng H., Chen Z.X., Yan H., Shao X. Electrospun nanofibrous membranes accelerate biofilm formation and probiotic enrichment: enhanced tolerances to pH and antibiotics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022;14(28):31601–31612. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c04540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Liang C., Tan C., Huang S., Ying R., Wang Y., Wang Z., Zhang Y. Liposome co-encapsulation as a strategy for the delivery of curcumin and resveratrol. Food Funct. 2019;10(10):6447–6458. doi: 10.1039/c9fo01338e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahandar-Lashaki S., Farajnia S., Faraji-Barhagh A., Hosseini Z., Bakhtiyari N., Rahbarnia L. Phage display as a medium for target therapy based drug discovery, review and update. Mol. Biotechnol. 2024;67:2161–2184. doi: 10.1007/s12033-024-01195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaprakash P., Maudhuit A., Gaiani C., Desobry S. Encapsulation of bioactive compounds using competitive emerging techniques: electrospraying, nano spray drying, and electrostatic spray drying. J. Food Eng. 2023;339 [Google Scholar]

- Ji C., Khan M.A., Chen K., Liang L. Coating of DNA and DNA complexes on zein particles for the encapsulation and protection of kaempferol and α-tocopherol. J. Food Eng. 2023;352 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Lv H., Lu Y., Lu Y., Lv L. Trapping of acrolein by curcumin and the synergistic inhibition effect of curcumin combined with quercetin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020;69(1):294–301. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D., Thurairajasingam S., Letchumanan V., Chan K.-G., Lee L.-H. Exploring the role and potential of probiotics in the field of mental health: major depressive disorder. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1728. doi: 10.3390/nu13051728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karoshi V.R., Nallamuthu I., Anand T. Co‐encapsulation of vitamins B6 and B12 using zein/gum Arabic nanocarriers for enhanced stability, bioaccessibility, and oral bioavailability. J. Food Sci. 2024;89(12):9766–9782. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.17567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran F., Afzaal M., Shahid H., Saeed F., Ahmad A., Ateeq H., Islam F., Yousaf H., Shah Y.A., Nayik G.A. Effect of protein-based nanoencapsulation on viability of probiotic bacteria under hostile conditions. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023;26(1):1698–1710. [Google Scholar]

- Laein S.S., Samborska K., Karaca A.C., Mostashari P., Akbarbaglu Z., Sarabandi K., Jafari S.M. Strategies for further stabilization of lipid-based delivery systems with a focus on solidification by spray-drying. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024;146 [Google Scholar]

- Lan X., Zhang X., Wang L., Wang H., Hu Z., Ju X., Yuan Y. A review of food preservation based on zein: the perspective from application types of coating and film. Food Chem. 2023;424 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leena M.M., Anukiruthika T., Moses J., Anandharamakrishnan C. Co-delivery of curcumin and resveratrol through electrosprayed core-shell nanoparticles in 3D printed hydrogel. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;124 [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y., Xie Z., Zhao A., Colarelli J., Miller M.J., Lee Y. Layer-by-layer coating of lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) using chitosan and zein/tween-80/fucoidan nanoparticles to enhance LGG's survival under adverse conditions. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;154 [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zheng Y., Wang P., Zhang H. The alginate dialdehyde crosslinking on curcumin-loaded zein nanofibers for controllable release. Food Res. Int. 2024;178 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.113944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X., Cheng W., Liang Z., Zhan Y., McClements D.J., Hu K. Co-encapsulation of tannic acid and resveratrol in zein/pectin nanoparticles: stability, antioxidant activity, and bioaccessibility. Foods. 2022;11(21):3478. doi: 10.3390/foods11213478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Hu J., Yao H., Zhang L., Liu H. Improved viability of probiotics encapsulated by layer-by-layer assembly using zein nanoparticles and pectin. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;143 [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Chen Y.-Y., Pan L.-H., Li Q.-M., Luo J.-P., Zha X.-Q. Co-encapsulation systems for delivery of bioactive ingredients. Food Res. Int. 2022;155 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Li L., Fang Z., Lee Y., Zhao J., Zhang H., Chen W., Li H., Lu W. The biofilm-forming ability of six bifidobacterium strains on grape seed flour. Lwt. 2021;144 [Google Scholar]

- Lo J.S.C., Chen X., Chen S., Daoud W.A., Tso C.Y., Firdous I., Deka B.J., Lin C.S.K. Fabrication of multilayer superhydrophobic and biodegradable filters through electrospinning and electrospraying of PHA-SiO2 biopolymer composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2025;512 [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Su C.-R., Li S.-Y., He S., Nag A., Yuan Y. Co-delivery of curcumin and quercetin in the bilayer structure based on complex coacervation. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;144 [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Su C., Li X., Wang H., Luo M., Chen Z., Zhang B., Zhu J., Yuan Y. Preparation and characterization of bilayered microencapsulation for co-delivery Lactobacillus casei and polyphenols via Zein-chitosan complex coacervation. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;148 [Google Scholar]

- Ma M., Liu Y., Chen Y., Zhang S., Yuan Y. Co-encapsulation: an effective strategy to enhance the synergistic effects of probiotics and polyphenols. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025;158 [Google Scholar]

- Ma M., Yuan Y., Yang S., Wang Y., Lv Z. Fabrication and characterization of zein/tea saponin composite nanoparticles as delivery vehicles of lutein. Lwt. 2020;125 [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Liu J., Li Y., Liu Y., Li S., Liu Y., Zhang T., Yang M., Liu C., Du Z. Egg white-derived peptides co-assembly-reinforced zein/chondroitin sulfate nanoparticles for orally colon-targeted co-delivery of quercetin in colitis mitigation. Food Biosci. 2025;65 [Google Scholar]

- Misra S., Pandey P., Mishra H.N. Novel approaches for co-encapsulation of probiotic bacteria with bioactive compounds, their health benefits and functional food product development: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;109:340–351. [Google Scholar]

- Moradinezhad F., Aliabadi M., Ansarifar E. Zein multilayer electrospun nanofibers contain essential oil: release kinetic, functional effectiveness, and application to fruit preservation. Foods. 2024;13(5):700. doi: 10.3390/foods13050700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezamdoost-Sani N., Khaledabad M.A., Amiri S., Khaneghah A.M. Alginate and derivatives hydrogels in encapsulation of probiotic bacteria: an updated review. Food Biosci. 2023;52 [Google Scholar]

- Nezamdoost-Sani N., Khaledabad M.A., Amiri S., Phimolsiripol Y., Khaneghah A.M. A comprehensive review on the utilization of biopolymer hydrogels to encapsulate and protect probiotics in foods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;254 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D.N., Clasen C., Van den Mooter G. Pharmaceutical applications of electrospraying. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016;105(9):2601–2620. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires J.B., Dos Santos F.N., da Cruz E.P., Fonseca L.M., de Oliveira Pacheco C., da Rosa B.N., Santana L.R., de Pereira C.M.P., Carreno N.L.V., Diaz P.S. Cassava, corn, wheat, and sweet potato native starches: a promising biopolymer in the production of capsules by electrospraying. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;281 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu C., Zhang Z., Li X., Sang S., McClements D.J., Chen L., Long J., Jiao A., Xu X., Jin Z. Co-encapsulation of curcumin and quercetin with zein/HP-β-CD conjugates to enhance environmental resistance and antioxidant activity. npj Science of Food. 2023;7(1):29. doi: 10.1038/s41538-023-00186-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radünz M., Mota Camargo T., dos Santos Hackbart H.C., Paes Nunes C.F., Araújo Ribeiro J., da Rosa Zavareze E. Characterization of ultrafine zein fibers incorporated with broccoli, kale, and cauliflower extracts by electrospinning. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022;102(10):4210–4217. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.11772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekharan S.K., Paz‐Aviram T., Galili S., Berkovich Z., Reifen R., Shemesh M. Biofilm formation onto starch fibres by Bacillus subtilis governs its successful adaptation to chickpea milk. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021;14(4):1839–1846. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren M., Xie T., Chen L., Zhao T., Zhou C. Pickering emulsion stabilized by hollow Zein/SSPS nanoparticles loaded with thymol: formation, characterization, and application in fruit preservation. Food Res. Int. 2025;201 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.115561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song T., Xiong Z., Shi T., Yuan L., Gao R. Effect of glutamic acid on the preparation and characterization of pickering emulsions stabilized by zein. Food Chem. 2022;366 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadele D.T., Islam M.S., Mekonnen T.H. Zein-based nanoparticles and nanofibers: co-Encapsulation, characterization, and application in food and biomedicine. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025;155 [Google Scholar]

- Tadele D.T., Mekonnen T.H. Co-encapsulation of quercetin and α-Tocopherol bioactives in zein nanoparticles: synergistic interactions, stability, and controlled release. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024;6(7):3767–3777. [Google Scholar]

- Tchuenbou-Magaia F.L., Tolve R., Anyadike U., Giarola M., Favati F. Co-encapsulation of vitamin D and rutin in chitosan-zein microparticles. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022;16(3):2060–2070. [Google Scholar]

- Virk M.S., Virk M.A., Gul M., Awais M., Liang Q., Tufail T., Zhong M., Sun Y., Qayum A., El-Salam E.A., Ekumah J.-N., Rehman A., Rashid A., Ren X. Layer-by-layer concurrent encapsulation of probiotics and bioactive compounds with supplementation in intermediary layers: an establishing instrument for microbiome recharge, core safety, and targeted delivery. Food Hydrocoll. 2025;161 [Google Scholar]

- Virk M.S., Virk M.A., Liang Q., Sun Y., Zhong M., Tufail T., Rashid A., Qayum A., Rehman A., Ekumah J.-N., Wang J., Zhao Y., Ren X. Enhancing storage and gastroprotective viability of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum encapsulated by sodium caseinate-inulin-soy protein isolates composites carried within carboxymethyl cellulose hydrogel. Food Res. Int. 2024;187 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volodkin D. CaCO3 templated micro-beads and-capsules for bioapplications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;207:306–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A., Zhong Q. Drying of probiotics to enhance the viability during preparation, storage, food application, and digestion: a review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024;23(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.13287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Liu Y., Sun J., Sun Z., Liu F., Du L., Wang D. Fabrication and characterization of gelatin/zein nanofiber films loading perillaldehyde for the preservation of chilled chicken. Foods. 2021;10(6):1277. doi: 10.3390/foods10061277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Li Z., Meng Y., Lv G., Wang J., Zhang D., Shi J., Zhai X., Meng X., Zou X. Co-delivery mechanism of curcumin/catechin complex by modified soy protein isolate: emphasizing structure, functionality, and intermolecular interaction. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;152 [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Wang C., Liu X., Mackie A., Zhang M., Dai L., Liu J., Mao L., Yuan F., Gao Y. Co-encapsulation of curcumin and β-carotene in pickering emulsions stabilized by complex nanoparticles: effects of microfluidization and thermal treatment. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;122 [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Yang S., Zhang L., Dai L., Tai K., Liu J., Mao L., Yuan F., Gao Y., Mackie A. Fabrication, characterization and in vitro digestion of food grade complex nanoparticles for co-delivery of resveratrol and coenzyme Q10. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;105 [Google Scholar]

- Weng J., Zou Y., Zhang Y., Zhang H. Stable encapsulation of camellia oil in core–shell zein nanofibers fabricated by emulsion electrospinning. Food Chem. 2023;429 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wusigale, Wang T., Hu Q., Xue J., Khan M.A., Liang L., Luo Y. Partition and stability of folic acid and caffeic acid in hollow zein particles coated with chitosan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;183:2282–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Guo J., Chang B., Wang Q., Zhang Y., Chen X., Zhu W., Ma J., Qian S., Jiang Z. Study on encapsulation of Lactobacillus plantarum 23-1 in W/O/W emulsion stabilized by pectin and zein particle complex. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;279 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Liang X., Ma C., McClements D.J., Liu X., Liu F. Design and characterization of double-cross-linked emulsion gels using mixed biopolymers: Zein and sodium alginate. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;113 [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Chen X., Lin J., Shen M., Wang Y., Sarkar A., Wen H., Xie J. Co-delivery of resveratrol and curcumin based on mesona chinensis polysaccharides/zein nanoparticle for targeted alleviation of ulcerative colitis. Food Biosci. 2024;59 [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., McClements D.J., Peng X., Qiu C., Long J., Zhao J., Xu Z., Meng M., Chen L., Jin Z. Co-encapsulation of quercetin and resveratrol in zein/carboxymethyl cellulose nanoparticles: characterization, stability and in vitro digestion. Food Funct. 2022;13(22):11652–11663. doi: 10.1039/d2fo02718f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., McClements D.J., Peng X., Xu Z., Meng M., Chen L., Jin Z. Fabrication of zein–carboxymethyl cellulose nanoparticles for co-delivery of quercetin and resveratrol. J. Food Eng. 2023;341 [Google Scholar]

- Yao L., Xu J., Zhang L., Liu L., Zhang L. Nanoencapsulation of anthocyanin by an amphiphilic peptide for stability enhancement. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;118 [Google Scholar]

- Yin M., Chen L., Chen M., Yuan Y., Liu F., Zhong F. Encapsulation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in double emulsions: role of prebiotics in improving probiotics survival during spray drying and storage. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;151 [Google Scholar]

- Yin M., Chen M., Yuan Y., Liu F., Zhong F. Encapsulation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in whey protein isolate-shortening oil and gum Arabic by complex coacervation: enhanced the viability of probiotics during spray drying and storage. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;146 [Google Scholar]

- Yin M., Yuan Y., Chen M., Liu F., Saqib M.N., Chiou B.S., Zhong F. The dual effect of shellac on survival of spray-dried Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG microcapsules. Food Chem. 2022;389 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y.-C., Yin S.-W., Yang X.-Q., Tang C.-H., Wen S.-H., Chen Z., Xiao B.-j., Wu L.-Y. Surface modification of sodium caseinate films by zein coatings. Food Hydrocoll. 2014;36:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yu C., Shan J., Fu Z., Ju H., Chen X., Xu G., Liu Y., Li H., Wu Y. Co-Encapsulation of curcumin and diosmetin in nanoparticles formed by plant-food-protein interaction using a pH-Driven method. Foods. 2023;12(15):2861. doi: 10.3390/foods12152861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Huang J., He S., Ma M., Wang D., Xu Y. One-step self-assembly of curcumin-loaded zein/sophorolipid nanoparticles: physicochemical stability, redispersibility, solubility and bioaccessibility. Food Funct. 2021;12(13):5719–5730. doi: 10.1039/d1fo00942g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Li H., Liu C., Zhang S., Xu Y., Wang D. Fabrication and characterization of lutein-loaded nanoparticles based on Zein and sophorolipid: enhancement of water solubility, stability, and bioaccessibility. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67(43):11977–11985. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b05175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Li H., Liu C., Zhu J., Xu Y., Zhang S., Fan M., Zhang D., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Wang D. Fabrication of stable zein nanoparticles by chondroitin sulfate deposition based on antisolvent precipitation method. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;139:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.07.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Li H., Zhu J., Liu C., Sun X., Wang D., Xu Y. Fabrication and characterization of zein nanoparticles by dextran sulfate coating as vehicles for delivery of curcumin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;151:1074–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Liu F., Chen M., Yin M., Tsirimiagkou C., Giatrakou V., Zhong F. Improving the survival of probiotics via in situ re-culture in calcium alginate gel beads. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;145 [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Ma M., Xu Y., Wang D. Surface coating of zein nanoparticles to improve the application of bioactive compounds: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022;120:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Xiao J., Zhang P., Ma M., Wang D., Xu Y. Development of pH-driven zein/tea saponin composite nanoparticles for encapsulation and oral delivery of curcumin. Food Chem. 2021;364 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Yin M., Chen L., Liu F., Chen M., Zhong F. Effect of calcium ions on the freeze-drying survival of probiotic encapsulated in sodium alginate. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;130 [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Yin M., Zhai Q., Chen M. The encapsulation strategy to improve the survival of probiotics for food application: from rough multicellular to single-cell surface engineering and microbial mediation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022;64(10):2794–2810. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2126818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J., Lyu Y., Huang X., Leung H.K., Zhao S., Zhang J., Wang Y., Wang D.Y. Optimizing Lactiplantibacillus plantarum viability in the gastrointestinal tract and its impact on gut microbiota–brain axis through zein microencapsulation. J. Food Sci. 2024;89(12):9783–9798. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.17368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Hassane Hamadou A., Chen C., Xu B. Entrapment of carvacrol in zein-trehalolipid nanoparticles via pH-driven method and antisolvent co-precipitation: influence of loading approaches on formation, stability, and release. Lwt. 2023;183 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Jiang H., Chen G., Miao W., Lin Q., Sang S., McClements D.J., Jiao A., Jin Z., Wang J., Qiu C. Fabrication and characterization of polydopamine-mediated zein-based nanoparticle for delivery of bioactive molecules. Food Chem. 2024;451 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.139477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Peng S., Zhang X., McClements D.J. Impact of delivery System type on curcumin bioaccessibility: comparison of curcumin-loaded nanoemulsions with commercial curcumin supplements. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2018;66(41):10816–10826. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b03174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y., Huang W., Zheng Y., Chen T., Liu C. Alginate-coated pomelo pith cellulose matrix for probiotic encapsulation and controlled release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;262 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F.-Z., Yu X.-H., Luo D.-H., Liu B., Yang T., Yin S.-W., Yang X.-Q. Facile and robust route for preparing pickering high internal phase emulsions stabilized by bare zein particles. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021;1(8):1481–1491. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Han Y., McClements D.J., Cheng C., Chen S. Co-encapsulation of anthocyanin and cinnamaldehyde in nanoparticle-filled carrageenan films: fabrication, characterization, and active packaging applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;149 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Sun H., Shen K., Liu Y., Nie R., Liu G. Preparation and properties of biofilm-states Bifidobacterium adolensentis Gr19 under dynamic culture system and its application on probiotic ice cream manufacture. Food Biosci. 2024;57 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.