Abstract

Background

Mistrust of medical providers disproportionately affects individuals from racialized communities. Mistrust of providers negatively influences willingness to seek care, which exacerbates health disparities. Patient-centered communication can mitigate this mistrust.

Objective

To assess the impact of a three-hour pilot workshop entitled Storytelling to Build Medical Trust, which brings medical students and Black, Indigenous and other People of Color (BIPOC) community members together to practice the skills underlying patient-centered communication, on medical student patient-centered communication self-efficacy and community member trust.

Methods

Medical students completed the Self-Efficacy in Patient-Centeredness Questionnaire (SEPCQ-27) before, after, and one-month post-participation in the workshop, while community members completed two sub-scales of the Collaboration Trust Scale at the same time points. Community members also participated in focus group discussions approximately one week after workshop completion. Focus group transcripts were analyzed using the Social Cognitive Theory.

Results

Median medical student SEPCQ-27 score increased 18 % pre to post-workshop (p < 0.001). Similarly, median scores of the Collaboration Trust Survey sub-scales “Trust in Communication” and “Trust in Partner Investment and Community Well-Being” increased 23.3 % (p = 0.025), and 18.75 % (p = 0.013), respectively. Analysis of focus group discussions identified five themes: 1) The workshop cultivated an open and comfortable environment; 2) Community members desire additional information and direction prior to the program; 3) Training medical students may have a downstream impact, but there is a pressing need to train current providers; 4) The workshop articulates opportunities for community members to assert their strength and empowers them to pursue them; and 5) Dismantling medical mistrust requires ongoing efforts.

Conclusion

The Storytelling workshop may build trust between patients from historically marginalized communities and medical practitioners.

Innovation

This is the first evaluation of a trust-building intervention that brings both medical providers and potential patients together in one room.

Keywords: Health equity, Trust, Patient-centered communication, Historically marginalized communities, Mixed methods

Highlights

-

•

Training medical students and community members improves patient-centered communication.

-

•

A collaborative learning environment may improve communication between patients and providers.

-

•

Patient and provider engagement in storytelling and listening may be a step towards improved trust.

1. Introduction

Mistrust of medical providers is associated with a patient's decreased willingness to seek care [1,2], including preventive screenings [[3], [4], [5]]; lower likelihood of following clinician instructions [2]; and poor satisfaction [6]. Mistrust of medical providers disproportionately impacts Black, Indigenous and other People of Color (BIPOC)1 communities [3,7], which exacerbates health disparities.

Interventions aimed at building patients' trust in medical providers report limited success. A 2014 Cochrane review identified ten randomized controlled trials that aimed to improve patients' trust in providers with various interventions, including: 1) coaching providers to improve their cultural competency and empathy, 2) using decision aids to educate patients, 3) providing patient education via group visits, and 4) providing patients with information about provider incentives [8]. Despite the Cochrane review's conclusion that there was insufficient evidence that any of these education strategies increased trust in physicians [8], interventions implemented since 2014 aimed at improving patients' trust have continued to use similar patient and provider education strategies, such as pre-appointment patient education and synchronous virtual group education [9,10]. Further, interventions to date have operated on parallel tracks, with patients and providers receiving education in how, theoretically, to trust the other, but not given the opportunity to learn with and from each other. These interventions, though satisfactory and informational for patients, did not build trust regardless of the duration of the interventions, whether one-time [9] or weeks-long [10].

There is a need for a new approach to improve patients' trust of medical providers. Patient-centered communication (PCC),2 which includes understanding a patient within their psychosocial circumstances, eliciting patients' opinions and needs, and engaging with patients to develop treatment plans aligned with their values [11], has been shown to mitigate patient mistrust of providers [12,13]. At the core of PCC is being curious about the patient's life and experiences, asking questions, and listening actively (i.e., skills facilitating connection), which improve patients' trust of providers [14,15]. These skills overlap with some concepts inherent in therapeutic empathy, such as exploring and shared understanding, and have shown to modestly improve healthcare outcomes [16,17]. However, current medical education and clinical practice promote efficiency over connection [18,19]. Igniting or re-igniting medical providers' curiosity about their patients' lives and strengthening skills that facilitate connection and understanding has the potential to improve the quality of PCC during encounters and, ultimately, trust. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of a pilot workshop that brings patients and medical students together to engage in mutual storytelling, listening, and curiosity building to improve trust.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Storytelling to build medical trust workshop

The Storytelling to Build Medical Trust (Storytelling) workshop was created by Everyday Boston (EB),3 a non-profit organization with the mission of bridging long-standing social, economic, and racial divides through the sharing of life stories. Full details of the curriculum development process can be found in Supplementary Appendix #1.

Briefly, the Storytelling workshop emerged from a formative three-year project uniting community members and healthcare professionals to amplify BIPOC voices on healthcare bias and motivate providers to drive change. Community members with the most mistrust felt unseen, unheard, and unappreciated; those with high trust felt the opposite—seen, heard, and valued as care partners. The workshop was based on the evidence-informed thesis that bringing patients and providers together in a neutral setting to practice connection and listening can spark curiosity and improve their use of PCC [14,15].

EB's co-founder designed the final workshop version, which was reviewed and approved by community members. Its goal is to foster shared humanity and build trust through skills like curiosity, active listening, and asking clarifying questions—not to completely eliminate medical mistrust. Community members endorsed it as a bridge-building activity, not a story-sharing session.

The three-hour workshop includes five sequential activities (Table 1) and accommodates 20–30 participants—equally split between community members and medical students—to promote balanced power dynamics and open discussion. One workshop was held at each of four Massachusetts medical schools (Dec 2023–Jan 2024). The pilot was co-facilitated by the curriculum developer. Community participants were recruited by EB via social networks (e.g., individuals who had engaged with EB in past activities) and social media and received $100. EB identified medical student champions who then recruited additional students through their social and academic networks. Medical students in the first workshop did not receive remuneration. Student participants received $40 for participation in the final three workshops.

Table 1.

Storytelling to Build Medical Trust workshop activities.

| Activity | Description | Learning Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Curiosity Teaser |

|

Recognize that our brains are hard-wired to make assumptions about others, but that these assumptions are often wrong, and always incomplete Explore curiosity as a tactic to dismantle stereotypes, and to focus on our shared humanity |

| Curiosity Deep Dive |

|

Forge connections with others by getting curious about their life experiences, asking about and better understanding their life experiences Explore important caveats about when curiosity becomes intrusive |

| Listening |

|

Understand signs of effective listening, and the profound impact it can have on another human being Explore important caveats about signs of listening, such as cultural or cognitive differences |

| Trust |

|

Identify qualities and actions which lead to trust |

| Health Care |

|

Translate findings about trust into actionable opportunities providers can take to build trust |

2.2. Pilot evaluation study design

We conducted a convergent parallel mixed methods pre and post evaluation of the pilot workshop. Surveys evaluated medical students' self-efficacy using PCC and community members' trust in healthcare providers, respectively. Additionally, as this was a pilot program and evaluation in preparation for a larger program scale-up, we collected qualitative data from the community member participants to receive feedback on the workshop itself, as well as any anticipated impacts of the workshop on their future interactions with the healthcare system (see Supplementary Appendix #3).

2.2.1. Study participant recruitment

At each workshop's start, a Research Assistant explained the study and invited participants to consent to the quantitative portion, clarifying that workshop participation was not dependent on study participation. At the end, the same Research Assistant invited community members to join one-hour group interviews (in-person or virtual) held a week later. All workshop participants were eligible to participate in group discussions regardless of survey participation. To reduce burden and maximize data, those unavailable for group interviews were offered individual interviews. All research activities were voluntary; we did not collect reasons for non-participation.

2.2.2. Quantitative data measures

We employed previously validated scales of provider self-efficacy in PCC and patient trust in collaboration with medical professionals including:

2.2.2.1. SEPCQ-27

Medical school students completed the Self-Efficacy in Patient-Centeredness Questionnaire (SEPCQ-27),4 a 27-item survey designed to assess patient-centeredness self-efficacy [20]. The SEPCQ-27 has previously been used with medical, nursing and other health sciences students to examine changes in their self-efficacy after educational interventions using pre- and post-surveys [[21], [22], [23]]. Each SEPCQ-27 item is scored on a scale from zero to four, with zero representing “To a very low degree” and four representing “To a very high degree,” for a total ranging from zero to 108 points; higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy. The SEPCQ-27 has three sub-scales: “Exploring the Patient Perspective,” “Sharing Information and Power,” and “Dealing with Communicative Challenges.”

2.2.2.2. Collaboration trust scale

Community member participants completed two, five-question sub-scales of the National Association of County & City Health Officials' Collaboration Trust Scale for Shared Services Arrangements Between Local Health Departments and Health Centers – “Trust in Communication” and “Trust in Partner Investment and Community Well-Being” – that were adapted to assess community members' opinions of healthcare provider trustworthiness (Supplementary Appendix #2). Each survey item is scored on a scale of one to five. One represents “Completely disagree” and five represents “Completely agree.” Respondents could also select zero for “Don't have enough information to respond.”

The Collaboration Trust Scale (CTS**) typically used to assess trust between health departments and health centers [24], and has not previously been applied to patients-provider relationships. Following a thorough literature search, the team found existing trust scales either focused on individuals doctor-patient relationships (e.g., Trust in Physician Scale [25]) or percecptions of systemic treatment by race/ethnicity (e.g., Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale [26]), both misaligned with the workshop's goals. Since the intervention aimed to build trust between medical stduents and community members, the CTS was selected—with EB's input—to measure connection and partnership rooted in shared humanity.

2.2.2.3. Quantitative data schedule of events

Medical student participants completed the SEPCQ-27 prior to participation in the workshop, immediately following the workshop, and one month after completion. Community member participants completed the CTS at the same time intervals.

2.2.3. Quantitative data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize participant demographics and pre−/post-workshop measures of self-efficacy and trust. Primary analyses assessed the workshop's impact on provider self-efficacy in patient-centered communication and community member trust, using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to compare pre- and immediate post-workshop survey scores. Only participants who completed both surveys were included.

For secondary analyses, we again used Wilcoxon tests to compare post-workshop and one-month follow-up scores, including only those who completed all three surveys. No participants completed only the post-workshop and one-month surveys. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. We used R Studio (v4.3.1) [27] to complete quantitative analyses.

2.2.4. Qualitative data collection

We conducted small group interviews with community members approximately one week after they completed the workshop. We created an interview guide (Supplementary Appendix #3) consisting of questions designed to elicit community member participants' feedback on the workshop and its activities, as well as their perception of the impact of the workshop on their future medical encounters. One of two members of the research team, a doctoral-trained health services researcher and a masters-trained research coordinator, conducted each interview. All interviews were recorded, de-identified, and transcribed verbatim.

2.2.5. Qualitative data analysis

We developed a codebook anchored in the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)5 to analyze all interview transcripts [28]. The SCT posits that an individual's actions are dynamically influenced by their environment, previous experiences, and behavior [28], and has been used widely in public health and medical settings to understand determinants of and influence health behavior [29]. We created a deductive coding frame using the six underlying constructs of the SCT: 1) reciprocal determinism, 2) self-efficacy, 3) behavioral capability, 4) observational learning, 5) reinforcements, and 6) expectations. One researcher then read two interview transcripts and created data-derived inductive child codes in line with each of the six parent codes anchored in the SCT. Three researchers met frequently throughout the codebook development process to iteratively refine the child codes, documenting all changes and updates throughout the process.

Once the study team developed and agreed upon a final codebook, two researchers independently analyzed all data using NVivo Release 1.7.1 (QSR International) [30,31], meeting weekly with the third study team member to discuss findings, resolve coding differences, and achieve consensus. After coding all transcripts, we used the Framework Method to analyze data [32]. This method involved exporting all coded phrases into a matrix and systematically and continually sorting, categorizing, and summarizing codes to identify themes [32]. The three researchers who participated in qualitative data coding and analysis were two doctoral-trained health services researchers and a masters- trained research coordinator; all are white women.

2.2.6. Human subjects protections

The Boston University/Boston Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

3. Results

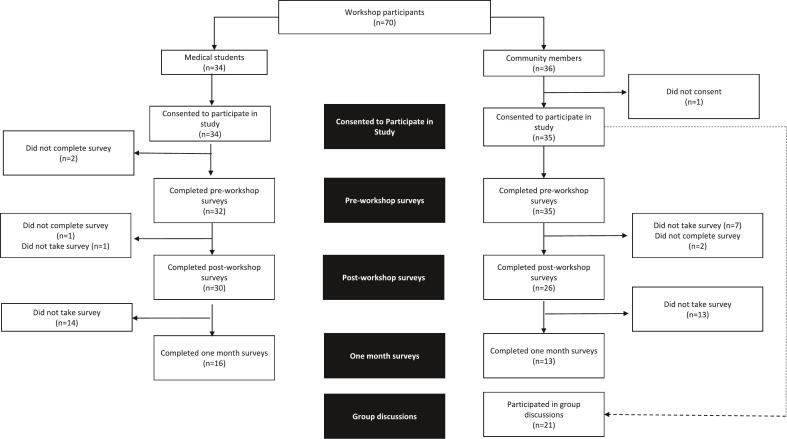

In total, 36 community members and 34 medical students participated across the four pilot workshops (Fig. 1). Except for one community member, all workshop participants agreed to participate in the quantitative portion of the study. Fourteen (40 %) community members declined to participate in the group discussions. In total, 26 community members and 30 medical students were included in primary analysis of the pre- and post-workshop surveys. Thirteen community members and 16 medical students were included in secondary analyses. Ten community members and four medical students were excluded from quantitative analyses due to incomplete pre- and post-workshop surveys.

Fig. 1.

Study participants in final analyses.

3.1. Quantitative results

3.1.1. Demographic surveys

The plurality of the medical students identified as female (66.7 %, n = 20), white (36.7 %, n = 11), and non-Hispanic (90.0 %, n = 27) (Table 2). Students' age ranged from 22 to 31 years. The majority of community member participants identified as female (65.4 %, n = 17), black (76.9 %, n = 20), and non-Hispanic (69.2 %, n = 18) (Table 2). Community members' mean age (50.8 years) was twice that of the medical students (24.5 years).

Table 2.

Demographic information of study participants (n = 54)a.

| Community Members (n = 26) |

Medical Students (n = 28)b |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender [n(%)] | ||

| Female | 17 (65.4 %) | 20 (71.4 %) |

| Male | 7 (26.9 %) | 6 (21.4 %) |

| Gender non-conforming / gender non-binary / genderqueer | 2 (7.7 %) | 1 (3.6 %) |

| Otherc | 0 (0 %) | 1 (3.6 %) |

| Age [Mean (SD)] | ||

| Mean (SD) | 50.8 (13.7) | 24.5 (2.01) |

| Race [n(%)] | ||

| Asian | 1 (3.8 %) | 7 (25.0 %) |

| Black or African American | 20 (76.9 %) | 3 (10.7 %) |

| White/Caucasian | 1 (3.8 %) | 11 (39.3 %) |

| Asian Indian | 0 (0 %) | 6 (21.4 %) |

| Other / Not Specified | 4 (15.4 %) | 1 (3.6 %) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity [n(%)] | ||

| Yes | 5 (19.2 %) | 1 (3.6 %) |

| No | 18 (69.2 %) | 27 (96.4 %) |

| Not Specified | 3 (11.5 %) | 0 (0 %) |

The full study sample includes n = 26 community members and n = 30 medical students. Two medical students did not provide any demographic information. Descriptive characteristics for age are based on n = 24 community members.

A total of 30 medical students participated across four sessions. Sessions were divided by medical school. Six (20.0 %) medical students were from Medical School A, 8 (26.7 %) were from Medical School B, 3 (10.0 %) from Medical School C, and 13 (43.3 %) from Medical School D.

A student who selected more than one gender identity was reclassified as “Other.” A student who selected more than one racial identity was reclassified as “Other.”

3.1.2. Impact on medical student self-efficacy in PCC

Primary analyses of medical students' surveys reveal self-reported scores increased after workshop completion. The median of the SEPCQ-27 total score increased from 64 pre-workshop to 76 points post-workshop, out of a possible 108 points, an 18.8 % increase (Table 3). For all three sub-scales, “Exploring the Patient Perspective,” “Sharing Information and Power,” and “Dealing with Communicative Challenges,” as well as the total SEPCQ-27 scores, there were statistically significant differences between pre- and post-workshop surveys (p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Impact on medical student self-efficacy in PCC as measured by SEPCQ-27.

| Measure | Pre-Workshop Median (n = 30) | Post-Workshop Median (n = 30) | p-Value⁎ | Post-Workshop Median (n = 16) | One Month Post-Workshop (n = 16) | p-Value⁎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exploring the Patient Perspective | 29 | 33.5 | <0.001 | 32.5 | 34 | 0.049 |

| Sharing Information and Power | 21.5 | 25 | <0.001 | 25 | 27.5 | 0.201 |

| Dealing with Communicative Challenges | 13.5 | 19.5 | <0.001 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 0.820 |

| Overall Sum | 64 | 76 | <0.001 | 76 | 81.5 | 0.179 |

p- value from Wilcoxon signed-rank tests; Significance assessed at p ≤ 0.05.

Secondary analyses among participants who completed the SEPCQ-27 one month after the workshop (n = 16) suggested that benefits sustained, and perhaps even grew over time. The median SEPCQ-27 total score increased from 76 points immediately after the workshop to 81.5 points one month following the workshop. There was only a statistically significant difference for the “Exploring the Patient Perspective” sub-scale (p = 0.049).

3.1.3. Impact on community member trust

The median scores of the sub-scales “Trust in Communication” and “Trust in Partner Investment and Community Well-Being” respectively increased from 15 to 18.5 points (23.3 % increase, p = 0.025), and 16 to 19 points (18.75 % increase, p = 0.013), out of a possible 25 points, from before to after the workshop (Table 4). For the secondary analyses (n = 13), there was no significant change between the post-workshop sub-scale scores and the one month post workshop scores.

Table 4.

Impact on community member trust as measured by Collaboration Trust Scale.

| Measure | Pre-Workshop Median (n = 26) | Post-Workshop Median (n = 26) | p-Value⁎ | Post-Workshop Median (n = 13) | One Month Post-Workshop (n = 13) | p-Value⁎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in Communication | 15 | 18.5 | 0.025 | 18 | 18 | 0.582 |

| Trust in Partner Investment in Community Well-Being | 16 | 19 | 0.013 | 19 | 18 | 0.269 |

p- value from Wilcoxon signed-rank tests; Significance assessed at p ≤ 0.05.

3.2. Qualitative results

Twenty-one community members participated in individual and small group interviews (Table 5). Two community members participated in individual interviews due to scheduling constraints, and the remaining 19 community members participated in group interviews, which ranged from two to five participants each. Analysis of the interviews identified five themes: 1) The workshop cultivated an open and comfortable environment; 2) Community members desire additional information and direction prior to the program; 3) Training medical students may have a downstream impact, but there is a pressing need to train current providers; 4) The workshop articulates opportunities for community members to assert their strength and empowers them to pursue them; and 5) Dismantling medical mistrust requires ongoing efforts.

Table 5.

Demographic information of community members who participated in group interviews (n = 19)a.

| Community Members | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 15 (78.9 %) |

| Male | 2 (10.5 %) |

| Gender non-conforming / gender non-binary / genderqueer | 2 (10.5 %) |

| Ageb | |

| Mean (SD) | 48.5 (15.5) |

| Race | |

| Black or African American | 16 (84.2 %) |

| Otherc | 3 (15.8 %) |

| Hispanic | |

| Yes | 3 (15.8 %) |

| No | 15 (78.9 %) |

| Not Specified | 1 (5.3 %) |

Descriptive characteristics for discussion participants who completed the demographic survey (n = 19).

Descriptive characteristics for age based on n = 17.

Participants who did not select an option for self-identified race are classified as “Other”.

The workshop cultivated an open and comfortable environment

The Storytelling workshop cultivated an environment in which community members felt comfortable sharing and connecting with each other and the medical students. Community members were able to learn from the medical students and felt the students were similarly open and receptive to learning from them.

“I feel like this workshop did kinda put a good taste in my mouth because, um, I would, if I didn't come, I would have never put that in my head to like understand what doctors, clients, patients, medical students, anyone that's in the…health field is going through” – Focus Group (FG) 7.

They reported that medical students were good listeners who actively sought out feedback and were notably eager to solicit opinions on how they could become better practitioners.

“They were open and cognizant of being listeners, true listeners. Not that they needed to jump in and say no, this is the way it should be or this is what I understand. No, they heard us, they heard us loud and clear” – FG3.

Community members desire additional information and direction prior to the program

Despite overall positive feedback, community members noted their confusion on the intentions of the workshop, and would have preferred to receive information on the workshop's goals and activities prior to participation. Gaining insights into the details of the workshop would allow participants to prepare themselves for the emotional work and vulnerability required for participation. Further, since the workshop is advertised as Storytelling to Build Medical Trust, community members believed they had been invited to share their own stories and were disappointed this opportunity did not materialize. They were interested in using their own experiences to convey why they experience medical mistrust and to use their personal stories to prevent medical students from making similar harmful mistakes in future practice.

“Since they had medical students, I thought that they, um, got us to come in there so we could tell them what we have experienced, you know, and, um, when we go to…receive medical care so that they could not do that” – FG4.

“The last piece about like your experience and stuff like that, honestly, like that probably should have been, we should have had more time to do that since like the goal I believe is the storytelling of your experience in the medical field. So I feel like that should have been like the main, like the area where we had more time and communication about that” – FG8.

Additionally, some community members felt the Curiosity Teaser activity (see Table 1), which required workshop participants to meet in small groups to imagine a narrative behind a picture given to them, could veer into assumptions and stereotyping. They did not believe the activity achieved its intended goal of piquing participants' curiosity about strangers.

Training medical students may have a downstream impact, but there is a pressing need to train current practitioners

Community members felt that medical students were open to learning, humble, and eager to participate in the workshop. While they felt this to be critical for training the next generation of providers, they noted that students are not the current drivers of medical mistrust and therefore should not be the main focus of the workshop. Instead, community members suggested they would have preferred to partake in the workshop alongside current practitioners.

“It was just also a little bit strange to me where the only doctor in the room is doctor [de-identified], respectfully. And like not to say like, yeah, we got the med students in their training but they're in training, they're not there yet…I feel like I would have felt more empowered, if I saw my PCP there. He trying to like, if he's actually trying to be in a community. Like if I would have seen more doctors in the room, that just makes sense and that just wasn't there” – FG5.

Community members noted that doctors in practice must be willing to actively listen to patients without the preconception that they know best because of their education and experience. If doctors were to participate in the workshop, community members expected doctors would learn to be more patient-centered, more willing to disrupt the existing power dynamic, and more eager to share power with patients.

“It's like she said, the wrong audience was there. It, it has to be the doctors and the practitioners to hear us the community, and what we feel and how we go about it and who we are as individuals” – FG2.

The workshop articulates opportunities for community members to self-advocate in medical encounters

Community members reported that hearing fellow participants' lived experiences confirmed the prevalence of medical mistrust. Instead of leading to hopelessness, it provided a sense of community, reminding community members that they are not alone in their experiences. Moreover, community members emphasized that workshop conversations equipped them with the language and tools to advocate for themselves in future medical encounters. They felt empowered to self-advocate, set boundaries, and effectively communicate with their own providers after workshop completion.

“I think is important and I think for the group it gave people the okay to be like, hey, these are things that you can and should be doing, um, to make sure you're creating boundaries for yourself and let them and, and so that we know that we actually have power. It's not just the doctor or the nurse and/or the nurse, like, we actually hold some power in those situations as well” – FG1.

“I feel more secure, because before I wasn't heard. Before, I didn't have a voice. Before I was afraid to speak. I was letting them say this and that and I wasn't speaking up, and now I'm like more, you know, assertive, I have the papers. I feel like, okay, I got this, you know, like we matter, you know” – FG2.

Dismantling medical mistrust requires ongoing efforts

Community members felt the workshop is a first step towards building trust with medical providers. However, dismantling mistrust and building trusting relationships cannot be accomplished without concerted, long-term efforts. They remarked that the workshop initiated a much-needed process, but one session is insufficient in building trust between vulnerable populations and healthcare providers. The workshop may inspire future change, but change would take time.

“The opportunity to get to really engage with the students in a one on one, you know, type of situation...It's like that type of thing is like, that's the type of thing that builds. He's right, that's the type of things that builds trust, that's the type of thing that builds, you know, um, security and, and, and security and that my doctor is gonna do the best thing for me” – FG6.

“I think it's a building block. You know, there might be other methodologies or other processes that are more effective and maybe this is just one step towards the continuum of what we're trying to achieve. And so I think, but this is a good first step in whatever we're trying to achieve here” – FG3.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

This mixed methods study of a pilot Storytelling to Build Medical Trust workshop found statistically significant increases in provider's self-efficacy in PCC and community members' trust of medical providers' communication and investment in community well-being. Qualitatively, community members noted the experience was acceptable and fruitful, but provided feedback for scale-up of the program.

Community members in this study experienced improvements in their trust of provider communication and provider investment in community well-being that persisted one month after the workshop. While these increases were small and conducted using non-validated scales, they are important findings showing that it is possible to impact patient trust of providers through a short intervention. As previous literature has shown limited success of interventions to improve trust [8], any potential impact is promising. While we hypothesized that increasing patient and community member curiosity and listening would lead to PCC self-efficacy and skills, and ultimately to trust, we did not explicitly measure curiosity or PCC skills among community members. Future research will aim to assess clinical significance of findings and understand what changes in skills and attitudes may lead to these changes in trust.

Medical students experienced improved self-efficacy in PCC from the beginning of the workshop to immediately after the workshop; this change persisted at one month. Previous research has shown that improving medical provider self-efficacy of PCC, as measured by the SEPCQ-27, was associated with improved patient activation and health behaviors [33]. Further, providers with higher SEPCQ-27 scores are perceived by their patients to have a higher degree of empathy [33], which can positively impact PCC [34]. These findings indicate that the workshop, by improving medical students' PCC self-efficacy, may be able to build a foundation on which medical students can continue to build their PCC skills to ultimately provide patient-centered care and improve trust.

The workshop was conceptualized to allow community members and medical students to see each other as individuals with shared humanity, understanding each other's perspectives and motivations. “Othering” – in which individuals from one group view individuals from outgroups as intrinsically different from themselves – likely plays a role in medical mistrust [35]. We thus anticipated that interactions between medical students and community members would improve trust as a result of time spent together having open discussion in a neutral (i.e., non-medical) environment. In fact, community members reported that the workshop provided them the skills, knowledge, and empowerment to assert themselves during future medical encounters, which they attributed to conversations with other community members. This aligns with previous research that found that peer support positively impacts self-advocacy in medical encounters [36,37]. This highlights the complex interpersonal and group dynamics at play during workshop sessions. Our future research will aim to unpack these relationships to understand the driving forces behind changes in PCC and trust. Nevertheless, as self-advocacy during medical encounters improves both physician communication [38] and alignment of patient and physician goals [39] – tenets of PCC and associated with improved trust – we are heartened by this finding.

This study had some limitations. First, this was a pre-post evaluation of a single-arm pilot study with no comparator group, which limits generalizability of findings. However, this pilot study was designed only to provide initial data to inform future iterations and scale-up of the workshop. The study design is prone to selection bias and may not be reflective of the medical student or community member population at large, as those who chose to attend are likely more interested in the topic than others. Of note, a number of study participants had engaged in prior EB programing, although not the workshop itself, which may have further contributed to selection bias.

Although we conducted focus groups among community members, we did not have the capacity within the scope of this pilot to hold medical student focus groups. We were therefore unable to report on medical students' feedback on the workshop or its perceived impact on their practice of PCC. Lastly, we used adapted sub-scales of the non-validated CTS, which may not have construct validity. However, this study was able to move the needle on PCC skills among medical students, which is linked to improved patient trust of providers. As trust is imperative to a patient-provider relationship and medical care, this finding is promising.

4.2. Innovation

To our knowledge, this is the first study that brought medical providers and community members together to to engage in a workshop aimed at improving trust. As trust is built largely on communication and understanding, providing a space outside of the medical encounter, in which providers and potential patients can practice communication skills, may be more effective than trainings in silos.

4.3. Conclusion

Our findings suggest the Storytelling workshop may help build trust between marginalized communities and medical practitioners. It created space for community members to assert power in medical settings and fostered a sense of empowerment. Results will be shared with the community and used to refine the workshop for broader implementation. Future versions, co-designed with community members, will involve practicing providers, rather than medical students, and expand into a multi-session curriculum to support lasting trust.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Rebecca K. Rudel: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Nicole D. Kaufmann: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Formal analysis. Shana A.B. Burrowes: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Cheryl Harding: Writing – review & editing. Cara Solomon: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Benjamin P. Linas: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Mari-Lynn Drainoni: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. Katherine Gergen Barnett: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [OT2HL61615].

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecinn.2025.100420.

BIPOC: Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color

PCC: Patient-Centered Communication

EB: Everyday Boston

SEPCQ-27: Self-Efficacy in Patient-Centeredness Questionnaire.

SCT: Social Cognitive Theory.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Curriculum development details

Collaboration Trust Scale

Focus grup discussion guide

References

- 1.Hammond W.P. Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. Am J Comm Psychol. 2010;45(1–2):87–106. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9280-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trachtenberg F., Dugan E., Hall M.A. How patients’ trust relates to their involvement in medical care. J Fam Pract. 2005;54(4):344–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musa D., Schulz R., Harris R., Silverman M., Thomas S.B. Trust in the Health Care System and the use of preventive health services by older black and white adults. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(7):1293–1299. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orji C.C., Kanu C., Adelodun A.I., Brown C.M. Factors that influence mammography use for breast Cancer screening among African American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(6):578–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell W., Richmond J., Mohottige D., Yen I., Joslyn A., Corbie-Smith G. Medical mistrust, racism, and delays in preventive health screening among African-American men. Behav Med. 2019;45(2):102–117. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2019.1585327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benkert R., Peters R.M., Clark R., Keves-Foster K. Effects of perceived racism, cultural mistrust and trust in providers on satisfaction with care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(9):1532–1540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoyt M.A., Rubin L.R., Nemeroff C.J., Lee J., Huebner D.M., Proeschold-Bell R.J. HIV/AIDS-related institutional mistrust among multiethnic men who have sex with men: effects on HIV testing and risk behaviors. Health Psychol. 2012;31(3):269–277. doi: 10.1037/a0025953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolfe A., Cash-Gibson L., Car J., Sheikh A., McKinstry B. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group, editor. 2014. Interventions for improving patients’ trust in doctors and groups of doctors. 2014(3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Malley P.G., Jackson J.L., Becher D., Hanson J., Lee J.K., Grace K.A. Tool to improve patient-provider interactions in adult primary care: randomized controlled pilot study. Can Fam Physician. 2022;68(2):e49–e58. doi: 10.46747/cfp.6802e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramos S.R., Warren R., Shedlin M., Melkus G., Kershaw T., Vorderstrasse A. A framework for using eHealth interventions to overcome medical mistrust among sexual minority men of color living with chronic conditions. Behav Med. 2019;45(2):166–176. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2019.1570074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein R.M., Franks P., Fiscella K., et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in Patient–Physician consultations: Theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1516–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elkefi S., Asan O. The impact of patient-centered care on Cancer patients’ QOC, self-efficacy, and trust towards doctors: analysis of a National Survey. J Patient Exp. 2023;10 doi: 10.1177/23743735231151533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuevas A.G., O’Brien K., Saha S. Can patient-centered communication reduce the effects of medical mistrust on patients’ decision making? Health Psychol. 2019;38(4):325–333. doi: 10.1037/hea0000721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene J., Ramos C. A mixed methods examination of health care provider behaviors that build Patients’ Trust. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(5):1222–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurtz J., Steenbergh K., Kessler J., et al. ‘What I wish my surgeon knew’: a novel approach to promote empathic curiosity in surgery. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(1):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howick J., Bennett-Weston A., Dudko M., Eva K. Uncovering the components of therapeutic empathy through thematic analysis of existing definitions. Patient Educ Couns. 2025;131 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2024.108596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howick J., Moscrop A., Mebius A., et al. Effects of empathic and positive communication in healthcare consultations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J R Soc Med. 2018;111(7):240–252. doi: 10.1177/0141076818769477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyche L., Epstein R.M. Curiosity and medical education: supporting curiosity in medical education. Med Educ. 2011;45(7):663–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald F.T. Curiosity. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(1):70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-1-199901050-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zachariae R., O’Connor M., Lassesen B., et al. The self-efficacy in patient-centeredness questionnaire – a new measure of medical student and physician confidence in exhibiting patient-centered behaviors. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0427-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harlan M.D., Bench V., Hudack C., et al. Using teaching videos to improve nursing students’ self-efficacy in managing patient aggression. J Nurs Educ. 2023;62(7):423–426. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20230509-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosasco J., Hanson Z., Kramer J., et al. A randomized study using telepresence robots for behavioral health in Interprofessional practice and education. Telemed e-Health. 2021;27(7):755–762. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chéret A., Durier C., Noël N., et al. Motivational interviewing training for medical students: a pilot pre-post feasibility study. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(11):1934–1941. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collaboration Trust Scale for Shared Services Arrangements Between Local Health Departments and Health Centers. Center for Sharing Public Health Services and the National Association of County & City Health Officials. http://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/6-Trust-Scale.pdf. n.d.

- 25.Thom D.H., Ribisl K.M., Stewart A.L., Luke D.A., Physicians T.S.T.S. Further validation and reliability testing of the Trust in Physician Scale. Med Care. 1999;37(5):510. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shelton R.C., Winkel G., Davis S.N., et al. Validation of the group-based medical mistrust scale among urban black men. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):549–555. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1288-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Studio Integrated Development for R. 2023. http://www.rstudio.com Published online.

- 28.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Islam K.F., Awal A., Mazumder H., et al. Social cognitive theory-based health promotion in primary care practice: a scoping review. Heliyon. 2023;9(4) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NVivo qualitative data analysis. Release 1.7.1. [software]. QSR International Pty Ltd. 2018. Available from: 2022. https://support.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/s/ Published online 2022.

- 32.Gale N.K., Heath G., Cameron E., Rashid S., Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Consoli S.M., Duclos M., Grimaldi A., et al. OPADIA study: is a patient questionnaire useful for enhancing physician-patient shared decision making on physical activity Micro-objectives in diabetes? Adv Ther. 2020;37(5):2317–2336. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01336-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michael K., Dror M.G., Karnieli-Miller O. Students’ patient-centered-care attitudes: the contribution of self-efficacy, communication, and empathy. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(11):2031–2037. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alpers L.M. Distrust and patients in intercultural healthcare: a qualitative interview study. Nurs Ethics. 2018;25(3):313–323. doi: 10.1177/0969733016652449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jonikas J.A., Grey D.D., Copeland M.E., et al. Improving propensity for patient self-advocacy through wellness recovery action planning: results of a randomized controlled trial. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(3):260–269. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Høgh Egmose C., Heinsvig Poulsen C., Hjorthøj C., et al. The effectiveness of peer support in personal and clinical recovery: systematic review and meta-analysis. PS. 2023;74(8):847–858. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cegala D.J., Post D.M. The impact of patients’ participation on physicians’ patient-centered communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cegala D.J., Street R.L., Clinch C.R. The impact of patient participation on Physicians’ information provision during a primary care medical interview. Health Commun. 2007;21(2):177–185. doi: 10.1080/10410230701307824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Curriculum development details

Collaboration Trust Scale

Focus grup discussion guide