Abstract

Pituitary adenomas (PAs) are common brain tumors, accounting for about 15% of all brain neoplasms. Although generally benign, they can lead to serious complications through mass effects and hormone dysregulation. Emerging evidence suggests that collagen, a major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM), plays a pivotal role in PA pathophysiology. Collagen provides both structural integrity and biochemical cues within the tumor microenvironment (TME), influencing cellular behaviors and intercellular interactions. Recent studies indicate that collagen remodeling in PAs is dynamic, with alterations in collagen composition and organization affecting tumor growth, invasion, and hormone secretion. Collagen degradation products and collagenase activity may also facilitate tumor invasion into adjacent tissues. Additionally, collagen has been implicated in immune modulation, acting as a physical barrier that restricts immune cell infiltration and promotes immune evasion through receptor-mediated signaling. Metabolically, collagen may serve as an energy source or modulate metabolic pathways to sustain tumor proliferation. Clinically, collagen content in PAs correlates with tumor consistency, which has implications for surgical resection strategies. Moreover, serum collagen is emerging as a potential non-invasive biomarker for PA diagnosis and prognosis. Targeting collagen synthesis, degradation, or its mechanotransductive signaling pathways represents a promising therapeutic avenue.

Keywords: Pituitary adenoma, Collagen, Tumor microenvironment, Tumor immunity, Extracellular matrix, Tumor invasion, Biomarker

Introduction

Pituitary adenomas (PAs) are one of the common brain tumors and account for about 15 % of intracranial tumors [1]. Although the majority of these tumors are benign, PAs can lead to severe neurological deficits by compressing adjacent structures and induce systemic complications through excessive hormone secretion [2]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) is increasingly recognized as a key factor in PA progression, with the extracellular matrix (ECM), especially collagen, being particularly important [3].

As the most abundant structural protein in the ECM, collagen not only provides mechanical support but also actively influences tumor growth, invasion, and therapy resistance [4]. However, the precise molecular mechanisms by which collagen modulates PA progression remain poorly understood.

This review aims to explore the multifaceted role of collagen in the pathogenesis of PAs, emphasizing its dynamic remodeling and diverse impacts on tumor progression. Specifically, we will analyze collagen-driven mechanisms regulating key aspects of PA biology within the TME, including tumor growth, invasion, hormone secretion, immune modulation, and metabolic reprogramming. Furthermore, we will discuss the therapeutic potential of targeting collagen in the treatment of PAs and its utility as a biomarker. By elucidating the complex interplay between collagen and PA, we can pave the way for the development of more effective treatments of PA.

Tumor collagen components are heterogeneously altered in pituitary adenomas

Collagen is a right-handed helix glycoprotein with three left-handed α chains, characterized by glycine–X–Y repeats (where X and Y are frequently proline or hydroxyproline) and hydroxyproline contributes to its thermal stability [5]. The collagen family comprises 28 members, and it can be classified into eight subpopulations based on structural domains, including (1)fibril-forming collagens (I, II, III, V, XI, XXVI, XXVII); (2) fibril-associated collagens (IX, XII, XIV, XVI, XIX, XX, XXI, XXII, XXIV), which characteristically link to the surface of collagen fibrils rather than form fibrils by themselves; (3) network-forming collagens (IV, VIII, X); (4) membrane-anchored collagens (XIII, XVII, XXIII, XXV); (5) multiple triple-helix domains and interruptions (XV and XVIII); (6) beaded-lament-forming collagen (VI); (7) anchoring bril forming collagen (VII); and (8) other COL types (XXVI, XXVIII) [6].

In normal pituitaries, collagen types I and IV (COL I and IV) are distributed across the pituitary gland, medial wall and pituitary capsule. The pituitary capsule displayed the least staining for both collagen types. In contrast, the medial wall exhibited the highest staining intensity for COL I, whereas the pituitary gland showed the greatest staining for COL IV. Furthermore, COL II and III were weakly expressed, being present in only a small subset of pituitary gland cells [7].

However, PAs, especially fibrous, large and more aggressive tumors, exhibit significant collagen remodeling, characterized by increased deposition of fibrillar collagens such as collagen types I and III (COL I and COL III), resulting in markedly higher collagen content compared to soft adenomas and normal pituitary glands [8]. This is due to an expansion in both the types and number of collagen-producing cells within PAs [8]. In contrast, non-fibrillar collagens, including COL IV and COL VI, are notably reduced in PAs. COL IV, a key component of basement membranes and commonly overexpressed in various cancers [9], is less abundant in PAs than in normal pituitaries [10], potentially due to proteolytic degradation by collagenases such as matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 (MMP-2 and MMP-9), which facilitate tumor invasion by degrading the ECM barrier [11,12]. Moreover, while ADAM12—a member of the A disintegrin and metalloproteinases (ADAMs) family with known collagenolytic activity—is upregulated in invasive PAs, its potential role in COL IV degradation has yet to be confirmed [13,14]. Similarly, COL VI, a beaded-filament-forming collagen typically localized near basement membranes, is downregulated in PAs, particularly its COL6A6 subunit, which shows a negative correlation with prolyl-4-hydroxylase alpha polypeptide III (P4HA3), an enzyme involved in collagen post-translational modification [15]. In addition to structural changes, ECM dynamics in PAs are influenced by regulatory enzymes such as lysyl oxidases (LOXs), which promote collagen crosslinking and matrix stiffening and are upregulated in PAs [16]. Although LOX-dependent crosslinks have been linked to pituitary hormone regulation, the precise mechanisms remain incompletely understood [17]. Moreover, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) also contribute to the regulation of collagen deposition, with fibrotic areas showing associations with TIMP-1 and TIMP-3 expression; however, their specific interactions with distinct collagen types remain to be elucidated [18,19] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Influence of different collagen types in tumor proliferation, invasiveness and hormone production in PA.

| Type | Expression in PA | Proliferation | Invasiveness | Hormone production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen type I | ↑ | ↓in AtT-20 cells | ↓ | ACTH↓ |

| Collagen type III | ↑ | ↑in GH3 cells when co-exposed to COL I | ↓ | Unknown |

| Collagen type IV | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | PRL↓ (compared to COL I/III) |

| Collagen type VI | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | Unknown |

* With the exception of collagen expression, all other results presented in this table were derived from artificial cell models rather than human pituitary adenoma specimens.

Collagen distribution within PAs is heterogeneous, with Xie et al. demonstrating that COL I and III are expressed at significantly higher levels in the cavernous sinus than in the sella turcica [16]. Additionally, collagen deposition varies among different types of PAs. For instance, TSH-secreting PAs exhibit the highest fibrous matrix deposition, whereas most null cell adenomas and GH-secreting adenomas generally show lower collagen content [8]. Gonadotroph non-functioning PAs (NFPAs) have significantly lower collagen deposition than GH-secreting PAs, with both thick and thin collagen fibers markedly reduced in invasive NFPAs compared to invasive GH-secreting PAs. Furthermore, invasive gonadotroph NFPAs display decreased collagen deposition compared to their non-invasive counterparts [20]. These findings suggest that collagen deposition patterns may provide insights into the differing biological behaviors and invasive potentials of these adenomas.

Tumor collagen-producing cells and concomitant ECM remodeling in pituitary adenomas

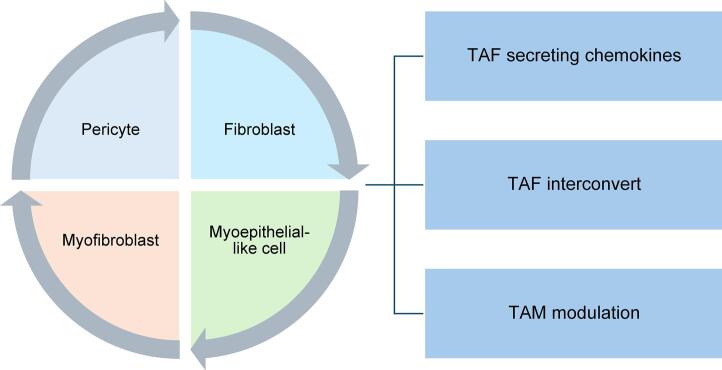

Collagen production and remodeling in PAs are orchestrated by a diverse array of cells within the TME. In the normal pituitary gland, pericytes are the primary collagen producers, ensuring the structural integrity of the ECM. However, in PAs, the spectrum of collagen-producing cells broadens to include fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and myoepithelial-like cells. This diversification possibly arises from the re-acquisition of mesenchymal traits through the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) from normal pituitary tissue to adenomas [8]. The spatial distribution of these cells varies: pericytes are located in the perivascular space, fibroblasts and myofibroblasts inhabit the fibrous matrix, and myoepithelial-like cells are found at the tumor cluster's base [8].

Despite these insights, it remains unclear which cell type predominates in collagen production within PAs. Evidence from a pan-human fibroblast categorization study suggests that the terminal differentiation state of fibroblasts (LRRC15+ fibroblasts) expresses pericyte markers (MCAM+ and PDGFRb+), indicating a potential differentiation pathway from pericytes to myofibroblasts [21]. Consequently, collagen-producing cells in PAs might share common origins and occupy distinct locations during differentiation to remodel the TME.

Collagen deposition consistently accompanies ECM remodeling (Fig. 1). The increasing numbers and types of collagen-producing cells in PAs lead to denser collagen deposition, which alters the tumor texture, making it firmer and more resistant to surgical resection [8,22]. This collagen deposition is influenced by the immune cells and is accompanied by chemokine secretion, which supports tumor growth and invasion. Cross-tissue human fibroblast analysis has revealed that collagen secretion can be induced by SPP1+ macrophages, promoting myofibroblast transformation and recruiting additional macrophages [21]. SPP1+ macrophages have also been identified in PAs, occurring alongside CD4+ T cells, potentially influencing tumor immunity and collagen production in PAs [23]. Cytokines, secreted alongside collagen by tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs), can increase PA aggressiveness, alter angiogenesis, and induce EMT changes [24]. These cytokines included CCL2, CCL11, VEGF-A, CCL22, IL-6, FGF-2, and IL-8. Notably, IL-6 is associated with cavernous sinus invasion, and CCL2 correlates with an increased number of capillaries and a higher Ki-67 index [24]. This suggests that collagen secretion may occur alongside tumor immunity and invasion, thereby remodeling the TME of PAs.

Fig. 1.

Collagen-producing cells in pituitary adenomas (PAs) and concomitant extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling.

Fibroblast remodeling also coincides with collagen secretion, involving three main subsets of TAFs identified by single-cell sequencing in the Pit-1 lineage of PAs: inflammatory TAF, myofibroblasts and antigen-presenting TAFs [25]. Myofibroblasts are typically located near tumor cells, while inflammatory fibroblasts, which secrete IL-6 and other cytokines, recruit and activate immune cells and regulate tumor progression, are found farther from cancer cells [26,27]. These two cell subpopulations are dynamic and can reversibly interconvert based on their spatial and biochemical niche within the TME [26,27]. In the Pit-1 lineage of PAs, IFN-γ signaling suppresses the functional remodeling of myofibroblasts towards inflammatory fibroblasts via STAT3 pathways, thereby enhancing anti-tumor effects and benefiting clinical treatments [25]. Hence, modulating the types and proportions of fibroblasts may represent a potential therapeutic strategy for PAs.

Tumor collagen influences tumor growth and invasion in pituitary adenomas

Different types of collagen and their associated collagenases have been shown to influence the invasiveness of PAs in artificial cell systems (e.g., AtT20 and GH3 cells), as summarized in Table 1. It is important to note that these findings regarding tumor behaviour are derived from in vitro or cell line-based models, and further validation in human tumor tissues is needed.

COL I, typically resistant to matrix metalloproteinases, can support invasive cancer cell proliferation and migration by providing a stable structure for cell movement [28]. However, in corticotroph tumor cells found in PAs, COL I has been observed to inhibit cell proliferation, indicating a potential suppressive effect on tumor growth [29]. Moreover, while COL I/III increases the aggregation capacity and internal tension of GH3 tumor cells, thereby reducing the invasion rate [30], it paradoxically promotes the proliferation of these cells [31]. Interestingly, the presence of COL I in GH3 cells confers resistance to gamma radiation, enhancing cell survival and increasing invasiveness through the activation of MAPK/ERK1/2 signaling when exposed to irritation [32].

Conversely, COL IV is known to promote cell proliferation and invasion in PAs. It fosters an invasive phenotype in GH-secreting PA (GH3) cells by enhancing substrate adhesion and altering cell motility [30]. Additionally, COL IV stimulates proliferation in corticotroph tumor cells (AtT-20) and is linked with increased invasiveness in PAs [29].

COL VI alpha 6 (COL6A6) is found to be downregulated in PAs, and its overexpression suppresses tumor growth and invasion. The inhibitory influence of COL6A6 on invasion is notably counteracted by P4HA3 and activating the pro-tumorigenic PI3K-Akt pathway [15].

Collagen degradation also plays a critical role in tumor invasion in PAs, primarily by facilitating the breakdown of basement membranes and adjacent structures, thereby weakening the barrier function and enabling tumor cell infiltration and extension [11,33]. This process is predominantly mediated by proteolytic enzymes, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing proteins (ADAMs), and cathepsin K (CTSK), which target collagen fibers by cleaving specific peptide bonds within their triple-helical structure [33,34]. Among these, MMP-2 and MMP-9, classified as type IV collagenases, are particularly implicated in degrading COL IV in the basement membrane, thus promoting tumor dissemination. Immunohistochemical (IHC) studies have demonstrated elevated MMP-9 expression in invasive and recurrent NFPAs, prolactinomas, and the majority of pituitary carcinomas, and is highlyassociated with cavernous sinus invasion [35,36]. Moreover, increased MMP-9 expression at both mRNA and protein levels has been consistently observed across various hormonal subtypes, tumor sizes, growth patterns, and between primary and recurrent tumors [37,38]. Similarly, MMP-2 expression is significantly associated with cavernous sinus invasion in PAs, independent of tumor size or hormonal classification [39]. A systematic review further confirmed that both MMP-2 and MMP-9 are markedly upregulated in invasive PAs compared to non-invasive ones, with statistically significant odds ratios (OR = 3.58, p = 0.001; OR = 5.48, p < 0.00001, respectively) [40]. Beyond role in collagen degradation, MMP-9 is also involved in angiogenesis where the release of growth factors, fibroblast growth factor and chemokines involved in the formation of new blood vessels within the TME [35,41]. Other collagenases such as MMP-14 and ADAM12 have also been linked to cavernous sinus invasion through ECM remodeling [14]. Additionally, CTSK, a potent collagenase primarily expressed in activated osteoclasts, contributes to bone resorption by degrading type I collagen, which constitutes approximately 90 % of bone collagen fibers [42]. Higher expression of CTSK in PAs is associated with larger tumor size, higher rates of compressive symptoms, and specifically, increased incidence of bony invasion into the sphenoid sinus rather than the cavernous sinus [43]. In vitro and in vivo studies have further elucidated its role in promoting bone invasion via TLR4-mediated RANKL expression in osteoblasts or stromal cells, as well as enhancing PA cell proliferation through activation of the mTOR signaling pathway [44].

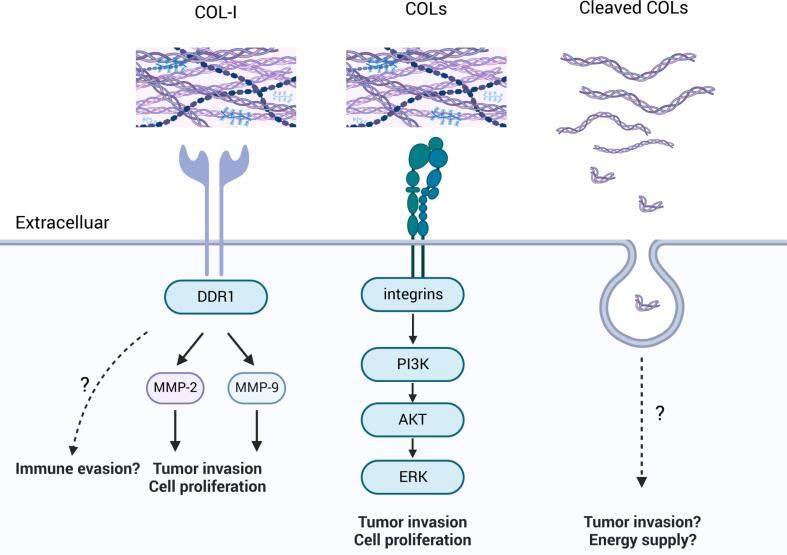

As for the specific mechanism, collagen can influence tumor cell behavior and promote cancer progression through interacting with discoidin domain receptors (DDRs), integrins, and other mechanisms (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Key pathways through which collagen influences PA progression.

DDRs, a novel class of receptor tyrosine kinases, are pivotal in cellular interactions with the ECM, particularly through collagen binding, which regulates cell invasion, adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and matrix homeostasis [45]. There are two primary types of DDRs, DDR1 and DDR2, each with distinct expression profiles and ligand specificities. DDR1 is notably involved in processes such as collagen synthesis, contraction, and fibrosis, while DDR2 is critical in the EMT process [46,47]. DDR1 predominantly binds to collagens I–V and VIII (including Periostin), whereas DDR2 binds to collagens I–III, V, and X [45]. In PAs, DDR1 expression is significantly higher in GH- and PRL-secreting macroadenomas compared to microadenomas, as demonstrated by Yoshida et al. [48] DDR1 facilitates PA cell (HP-75 cell line) invasion through adhesion to COL I and subsequent activation of the MMP-2 and MMP-9 signaling pathways, with no association with COL II, III, or IV [48]. Under hypoxic conditions of the TME, DDR1 expression is upregulated in PA cells, leading to increased secretion of MMP-2 and MMP-9, which promote tumor cell proliferation and invasion [49]. DDR1 inhibitors, such as nilotinib, have been shown to reduce DDR1 levels and decrease MMP-2 and MMP-9, suggesting a potential therapeutic strategy for invasive PAs [49.] Although COL IV is also reported to adhere to DDR1 and promote tumor progression in various cancers [50], this pathway has yet to be elucidated in PAs. While DDR2 may play a significant role in EMT and other biological processes, its impact on PAs remains unexplored.

Integrins, another class of tumor surface receptors, mediate cell adhesion and transmit mechanical and chemical signals to the cell interior, influencing multiple stem cell functions in cancer, including tumor initiation, epithelial plasticity, metastatic reactivation, and resistance to targeted therapies [51]. The key downstream signaling pathways of collagen-integrin interactions in most cancers include the AKT/PI3K, MAPK, Rho family, and MEK/ERK pathways [9,52]. For instance, COL IV binds to integrins α1β1 and α2β1 activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, which promotes tumor cell growth and anti-apoptosis [53,54]. It can also activate the MAPK/ERK pathway, regulating tumor cell proliferation and migration [55]. Similarly, another collagen type, COL I, functions through the integrin α2β1/PI3K/AKT/Snail signaling to enhance colorectal cancer stemness and metastasis [52]. In PAs, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAF/MEK/ERK pathways have been identified as significant in PA invasiveness, suggesting the potential role of collagen-integrin binding in tumorigenesis through these pathways [56]. The primary integrin subunits identified in PAs include α1, α2, α5, β1, and β4, with particularly high expression of α2 and β4. Specifically, integrins α1β1 and α2β1 recognize collagen types I, III, and IV, α5β1 acts as a fibronectin receptor, and α6β4 serves as a laminin receptor [31]. Bioinformatics analysis has also shown upregulation of integrin α6 in invasive NFPAs [57].

Integrins are being investigated for their role in regulating the invasiveness and progression of PAs. Among NFPAs, silent corticotroph adenomas (SCAs) are more aggressive than non-functioning gonadotroph adenomas (NFGAs). Research by Mete et al. revealed that SCAs exhibit higher levels of β1 integrin compared to NFGAs, contributing to their biological aggressiveness [58]. Additionally, β1 integrin promotes PA progression through the FAK/PI3K and FAK/ERK pathways [59]. Thus, the collagen-integrin pathway presents a promising mechanism for enhancing PA growth and invasiveness, though it has yet to be directly validated in vivo or in vitro. Further investigation is necessary to substantiate these findings.

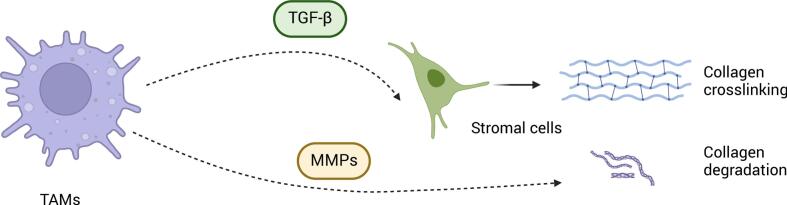

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) also regulate collagen function. (Fig. 3) TAMs promote tumor metastasis by driving stromal cell-dependent collagen crosslinking and stiffening in human breast cancer, with the stiffest stroma harboring the highest density of macrophages [60]. Furthermore, TAMs secrete TGF-β to activate stromal-mediated collagen crosslinking and increase the expression of collagen-crosslinking enzymes such as lysyl oxidase (LOX) and lysyl hydroxylase two (LH2) [60,61]. Besides facilitating collagen crosslinking, TAMs contribute to collagen degradation through mannose receptor-dependent endocytic pathways, facilitating collagen internalization and lysosomal breakdown [62]. Such remodeling of the tumor stroma may enhance tumor invasiveness by altering the TME's physical architecture. A similar mechanism has been proposed in PAs, where TAMs are hypothesized to secrete MMPs to degrade collagen, although the precise regulatory networks remain to be elucidated [3].

Fig. 3.

The impact of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) on collagen dynamics within the ECM.

Collagen fragments generated by MMPs can act as signaling molecules, further promoting tumor invasion [63]. Collagenase MMP-2, MMP-9, and cathepsin K enhance PA invasiveness, indicating that collagen fragments of types I and IV may contribute to this invasiveness [35,44,49]. Cleaved collagen has been shown to promote cancer progression in various cancers. For instance, Su et al. found that COL I cleaved by MMPs, rather than intact collagen, promotes pancreatic cancer growth through DDR1-NF-kappaB-p62-NRF2 signaling [64]. Similarly, cleaved COL XVII is associated with increased invasiveness in squamous cell carcinoma by enhancing cell motility and adhesion [65]. The cleaved fragment of COL VI, endotrophin, is highly expressed in various cancers and promotes tumor progression by inducing EMT and fibrosis through TGF-β-dependent mechanisms [66].

Tumor collagen influences hormone activity in pituitary adenomas

Recent studies have highlighted the role of collagen in influencing hormone production in PAs, particularly in corticotroph-secreting PAs and GH3 cells. A recent bulk RNA-Seq analysis revealed an up-regulation of several collagen genes, including COL1A1, COL4A3, COL4A4, COL20A1, and COL28A, in active corticotroph-secreting PAs compared to their silent counterparts, which do not produce ACTH [67]. However, in vitro experiments have shown that COL I, despite its up-regulation in active corticotroph-secreting PAs, actually inhibits ACTH biosynthesis in corticotroph tumor cells (AtT-20 cell line), a phenomenon not observed in normal pituitary cells [29]. In GH3 cells, basal PRL secretion decreased when exposed to COL IV compared to COL I/III exposure [31]. These findings underscore the distinct effects of different collagen types on hormone secretion across various PA cell lines. Further research is essential to elucidate the underlying mechanisms governing these interactions.

Tumor collagen modulates immune process in pituitary adenomas

Collagen can modulate immune responses in the tumor and is possibly responsible for immune evasion. It affects the function and phenotype of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, such as macrophages and T cells, thereby potentially impacting cancer progression and the efficacy of immunotherapy [68]. It functions as a physical barrier that prevents immune cells from infiltrating tumor cells, trapping immune cells such as T cells in the stroma [69,70]. Additionally, collagen can suppress immune responses by acting as a ligand that interacts with receptors on immune cells and tumor cells [68,69,71].

PAs exhibit a cold immune infiltration phenotype, ranking among the least immunologically active tumor types across a spectrum of 35 human cancers [72]. The immune status of the TME in PAs is complex and characterized by varying degrees of immune cell infiltration, with macrophages and T cells being prominent [73]. Macrophages predominate among intratumoral immune cells in PAs (median 42 %, IQR: 27–64 %), followed by CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and NK cells (∼11–12 %, IQRs: 5–20 %), whereas other immune populations remain low [72]. Specifically, CD68+ macrophage infiltration tends to occur in larger and more invasive adenomas [74]. Functioning PAs generally exhibit higher infiltration of B cells and CD8+ T cells compared to non-functioning PAs [73,75]. Moreover, aggressive PAs show upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules (ICM) such as PD-L1, PD-L2, CD80, and CD86, facilitating immune escape [76]. Conversely, some PAs exhibit downregulated ICM genes, indicating potential unresponsiveness to immunotherapy [77]. Notably, PD-L1 expression is detected in only a small subset of PAs, ranging from 15 % to 18 %, and its expression does not correlate with any specific biological features or clinical behavior of the tumor [78,79]. Of the PD-L1-positive PAs, 82.5 % belong to the PIT-1 lineage, suggesting that this subgroup may derive particular benefit from anti-PD-L1 immunotherapeutic strategies [79].

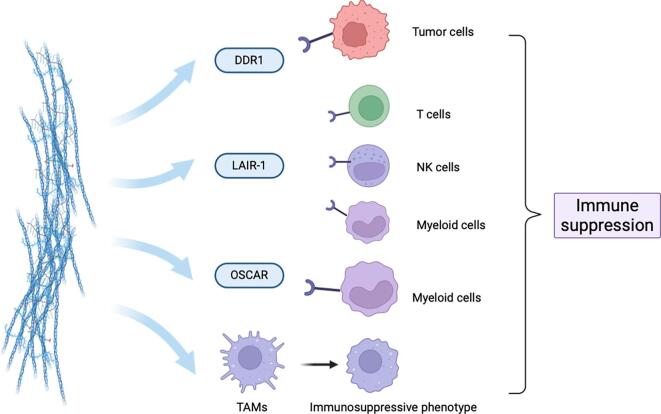

Collagen deposition may be negatively correlated with macrophage infiltration, as evidenced by a study by Principe et al., which found increased percentages of CD68+ and CD163+ macrophages in invasive NFPAs compared to non-invasive ones, aligning with decreased collagen deposition in invasive PAs [20]. Despite extensive research on collagen's impact on local tumor immunity, its effects on PAs remain underexplored. PAs with firm textures exhibit significant collagen deposition, theoretically creating a physical barrier that hinders immune cell infiltration. Furthermore, some receptors that bind collagen are expressed in PAs. Below are potential mechanisms by which collagen may suppress immunity in PAs (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Collagen-mediated immune suppression in PAs through interactions with tumor cells and TAMs.

Integrins have been shown to contribute to immune evasion in various cancer types [80,81]. Specifically, integrin β1, often found paired with α subunits (like α1, α2, α10, and α11), forms receptors that bind to collagen [82]. These collagen-binding integrins are crucial mediators of the communication between tumor cells and their surrounding stroma, which ultimately contributes to immune evasion [82]. For example, in pancreatic cancer, the integrin α3β1 complex actively promotes tumor progression and resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy by interacting with type I collagen homotrimers [83]. Research has shown that degrading these collagen homotrimers can increase T-cell infiltration and improve their survival in mouse models [83]. Other integrins, such as αvβ3 and αvβ6, similarly promote metastasis and immune evasion in various cancers by upregulating PD-L1 or activating TGF-β signaling [80,81]. Recent spatial transcriptomic analyses of by our team, validated by immunofluorescence, unveiled a close interaction between SPP1+ TAMs and TAFs in PA tissues, suggesting paracrine macrophage recruitment by TAF-derived collagen [84]. We also found SPP1-induced PA cell proliferation and invasion depended on Integrin β1 signaling [84], though that study lacked specific enrichment or confirmation of the collagen-immune cell axis. Emerging evidence shows SPP1 promotes fibrosis and collagen production by modulating MMP-9 in fibroblasts, facilitating TGFβ activation and subsequent COL I synthesis [85]. Furthermore, SPP1 correlates negatively with CD8+ T cell infiltration across tumor types, contributing to T cell exhaustion and immune suppression [86,87]. Given these findings, we hypothesize that SPP1 induces collagen production in the PA tumor microenvironment, subsequently activating Integrin β1 signaling to modulate T cell exhaustion and immune escape. This proposed SPP1-collagen-integrin axis mechanism requires experimental validation but could offer novel insights into PA immune evasion.

DDR1, as previously described, is known to promote the invasion and proliferation of PA cells [48,49]. DDR1 significantly influences tumor immunity by promoting immune exclusion and altering immune cell infiltration across various cancers, where high DDR1 expression correlates with reduced immune cell presence in the TME and sfunctions as negative immunomodulator [[88], [89], [90], [91]]. Mechanistically, the DDR1 extracellular domain (DDR1-ECD), rather than its intracellular kinase domain, is crucial for immune exclusion. Upon binding to collagen, DDR1-ECD maintains fiber alignment and prevents immune infiltration. Neutralizing antibodies targeting ECD can disrupt this alignment, increasing immune cell infiltration and promoting IFN-γ production, ultimately inhibiting tumor growth [92]. The humanized antibody PRTH-101 targets DDR1 to inhibit its phosphorylation, reduce collagen-mediated cell attachment, and prevent DDR1 shedding, thereby altering collagen alignment and promoting CD8+ T cell infiltration in tumors [89]. DDR1-related gene signatures have been validated to predict responsiveness to PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor therapy and stratify differential T-cell infiltration in the TME [93]. Therapies targeting DDR1 have shown promise in enhancing glioblastoma treatment, with DDR1 inhibition in combination with radiochemotherapy and temozolomide improving sensitivity and extending survival beyond conventional therapy [94]. In PAs, DDR1 binding to collagen activates MMP-2 and MMP-9, leading to ECM degradation and enhanced tumor cell invasion [48]. While the precise mechanisms of immune evasion in PAs require further investigation, studies in other cancers shed light on MMP-9′s role in this process. Activated MMP-9 cleaves chemokines such as CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, thereby impairing the recruitment of anti-tumor T cells to TME [95]. Additionally, MMP-9 contributes to tumor-associated immunosuppression by increasing the bioavailability of VEGF. This, in turn, promotes the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which inhibit T-lymphocyte proliferation, and facilitates the infiltration of tumor-promoting macrophages [96]. Consequently, targeting DDR1 in PAs with firm textures and abundant collagens may contribute to immune exclusion in the TME and serve as a therapeutic target, potentially enhancing PD-L1 indications screening and combination therapies such as radiotherapy and temozolomide.

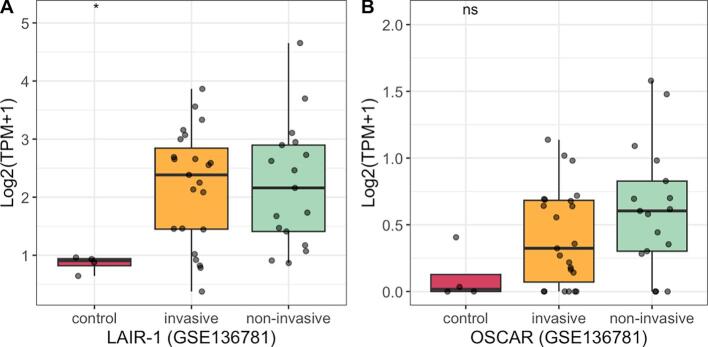

Leukocyte-Associated Immunoglobulin-like Receptor-1 (LAIR-1) is a type-I transmembrane receptor expressed on T cells, NK cells, myeloid cells, and other immune components [97]. It specifically binds to collagen and collagen-like proteins, triggering inhibitory signaling [98,99]. Collagen in the TME causes immune exclusion by physically preventing the infiltration of LAIR-1-expressing immune cells and hindering the activation of tumor antigen-specific T cells and myeloid cells [69,100]. The receptor LAIR-1 is upregulated following CD18 (also known as integrin β2) interaction with collagen, and induces CD8+T cell exhaustion through SHP-1, which thereby creating immunesuppresive TME in cancer and exacerbate resistance to anti-PDL1 immunotherapy [100]. Triple blockade of PD-L1, TGF-β and LAIR-1 signaling was able to enhance recruitment and activation of CD8+ T cells, reduce M2 macrophage populations, and remodel collagens in the TME, resulting in effective tumor control in murine cancer models [69]. Additionally, cleaved COL I produced in cancer can mediate immune suppression by binding to and triggering LAIR-1, inhibiting CD3 signaling and IFN-γ secretion in T cells [101]. Strategies targeting collagen interactions, such as using LAIR-2 to block LAIR-1-mediated immune suppression, are being explored [69,102]. The LAIR-2 Fc protein, known as NC410, is designed to block human LAIR-collagen interaction, reducing collagen content in the ECM, enhancing tumor infiltration and activation of CD8+ T cells, and repolarizing suppressive macrophage populations [69,102]. NC410 has also been shown to facilitate PD-L1-mediated tumor eradication in solid tumors in vitro, with ongoing clinical trials for NC410 in human solid tumors (NCT04408599) [69,102]. Analysis of RNA-sequencing data from the GSE136781 dataset (GEO database) revealed significantly elevated expression of LAIR-1 in NFPAs compared to normal pituitary gland tissue (Fig. 5A). Therefore, further research on LAIR-1′s mechanisms in PAs could reveal important information about tumor development and immune evasion.

Fig. 5.

The RNA expression of LAIR-1 and OSCAR in Non-functioning Pituitary Adenomas.

The Osteoclast-associated receptor (OSCAR) is another collagen receptor similar to LAIR-1, promoting cellular activation and maturation of immune cells and enhancing proinflammatory circuits [103]. While OSCAR has a proinflammatory role, its RNA expression is positively linked to increased levels of M2 macrophage polarization, T cell exhaustion, mesenchymal phenotype, and metastasis in most cancer types [104]. We also found OSCAR is highly expressed in NFPA (GSE136781), and its potential role in PAs remains to be investigated (Fig. 5B).

In addition, TAMs are sepculated be remodeled in the TME of PAs, promoting immune suppression. High collagen density instructs macrophages to acquire an immunosuppressive phenotype, impairing their ability to recruit and activate cytotoxic T cells, thereby fostering an immune-evasive niche that supports tumor progression and diminishes the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies [105].

Tumor collagen possibly affects metabolism in pituitary adenomas

Collagen significantly influences tumor metabolism by modulating metabolic pathways and regulating nutrient availability. For instance, in breast cancer, high collagen density has been shown to decrease glucose utilization in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle while increasing glutamine utilization as an energy source [106]. Furthermore, collagen itself can serve as a fuel source to sustain tumor survival. In pancreatic cancer, where tumor cells are embedded in a collagen-rich meshwork with limited oxygen and nutrient access, collagens are cleaved into fragments by MMPs and then transported into the cytoplasm and metabolized as proline fuel into the TCA cycle, thereby promoting tumor cell survival [107].

Similarly, in PAs, glucose metabolism and glycolysis are reduced compared to normal tissues, with evidence suggesting that anaplerosis of glutamate may be enhanced to supplement the TCA cycle [108]. In PAs, particularly aggressive macroadenomas characterized by stiff tumor texture, the dense collagen matrix limits oxygen and nutrient diffusion, resulting in a hypoxic microenvironment. This hypoxia drives the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), and other pro-angiogenic factors, further supporting tumor growth and invasion [11,109]. Notably, hypoxia can also increase PA cell adhesion and invasion through the upregulation of laminin β2 and enhance binding to COL IV [110]. However, the dynamic regulation of tumor metabolism by collagen in PAs remains largely unexplored, and the translation of these mechanistic insights into effective therapeutic strategies requires further investigation.

Potential clinical implications of tumor collagen in pituitary adenomas

While collagen exhibits significant genetic stability and a stable spatial structure, offering therapeutic potential in various cancers, its role in PA remains underexplored. Here, we will discuss the potential clinical implications of collagen in PA.

Radiological assessment of collagen content

Tumor firmness plays an important role in guiding surgical strategies and predicting postoperative complications [111]. In PAs, this property is largely influenced by collagen content, which has been highlighted as a critical determinant in surgical planning and outcomes. Studies consistently show a direct correlation between collagen content and tumor consistency. Higher collagen content, particularly of types I and III, leads to firmer, more fibrous tumors, while lower collagen content is associated with softer tumors [22]. Specifically, higher collagen content correlates with increased tumor stiffness, with collagen thresholds of 3.74 % and 8.93 % being identified as critical values for predicting soft and tough tumor textures, respectively [112]. Imaging features such as T2-weighted MRI and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values have been explored as predictors of consistency, with some studies suggesting that lower T2 signal and ADC correlate with higher collagen content [112,113]. However, other studies have found no statistically significant correlation between T2WI signal intensity and tumor consistency, indicating that T2WI alone may not be a reliable predictor [22]. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI), particularly parameters like 've' (volume of extravascular extracellular space per unit volume of tissue), shows stronger correlations with collagen content and may offer a more reliable preoperative assessment of tumor consistency [113]. The volume transfer constant (Ktrans) from DCE-MRI has also been shown to be higher in harder adenomas [113]. Studies on ultrahigh-field MRI (7T MRI) further suggested that soft tumors tend to have a significantly higher proportion of voxels with signal intensity greater than that of the local gray matter, in addition to increased vascularity, compared to firm tumors. Besides, Histological analysis revealed the percentage of hyperintense tumor voxels is correlated with collagen content [114]. Hence, it is essential for surgeons to understand the collagen composition of PAs through preoperative imaging to design surgical approaches and anticipate challenges related to tumor removal, such as adherence to surrounding structures, resistance to dissection tools and higher residual tumor rates.

Serum collagen as a diagnostic biomarker

Serum collagen and its derivatives hold significant potential as diagnostic biomarkers for PAs. Research increasingly supports their utility in distinguishing neoplastic from non-neoplastic conditions. Thorlacius et al. demonstrated that circulating collagen levels exhibit strong diagnostic accuracy in differentiating cancer patients from healthy controls, underscoring their potential as non-invasive tools for tumor detection and characterization [115]. Because pancreatic cancer is known to be the most collagen-rich cancer, serum collagen levels have been applied for prognosis prediction, with higher levels of the propeptide of type III collagen (PRO-C3), PRO-C5, PRO-C11, PRO-C20 and PRO-C22 correlate with poor survival [[116], [117], [118], [119], [120]]. Similar serum collagen markers were also applied for breast cancer to predict survival and metastasis risk [121,122]. In PAs, Gruszka et al. reported that serum levels of the cleaved fragment of collagen XVIII, known as endostatin, were elevated in patients with PA compared to control subjects [123]. Additionally, these elevated levels showed positive correlations with circulating VEGF, which may contribute to the relatively weak neovascularization observed in PAs [123]. However, it remains unclear whether collagen and its degradation fragments correlate with disease progression, pituitary hormone secretion, tumorigenesis, or treatment response. To date, a validated panel of collagen-specific serum biomarkers for PAs has not been established in routine clinical practice. Efforts have been tried to identify invasive and non-invasive PAs by testing collagenase MMP and TIMP levels in circulating plasma, while plasma MMP-9 and TIMP-2 concentrations did not demonstrate significant difference as their tissue counterparts did. MMP-2 was even not detected in plasma of PAs [124]. Further research is needed to elucidate the functional roles and clinical relevance of circulating collagen and its fragments in PAs.

Enhancing the sensitivity of chemotherapy

Temozolomide is the first-line chemotherapeutic agent for invasive and refractory pituitary adenomas; however, its efficacy is limited to only one-third of patients [125]. Similar resistance has been observed in glioblastoma, where DDR1, a key mediator of tumor cell interactions with collagen, has been targeted to enhance the treatment of glioblastoma. Inhibition of DDR1 in combination with radiotherapy and temozolomide in glioblastoma models has shown efficacy in enhancing sensitivity and prolonging survival superior to conventional therapy [94]. In addition, collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase (P4H), which stabilizes the collagen triple helix, has been shown to promote chemoresistance of docetaxel and doxorubicin by modulating HIF-1-dependent cancer cell stemness in breast cancer. Targeting collagen P4H, therefore, represents a potential strategy to inhibit tumor progression and enhance chemosensitivity [126]. These findings suggest that collagen-targeted therapies, when combined with chemotherapy, hold promise as a treatment modality in cancers. Further research is required to evaluate the therapeutic potential of these strategies PAs, particularly refractory PAs, where they may offer a significant opportunity to improve remission rates.

Collagen targeting therapy

Medications such as somatostatin analogs and dopamine agonists, commonly employed in the management of PAs, have demonstrated efficacy in both tumor shrinkage and hormonal control [1]. However, these medications can induce potential adverse effects, including increased collagen volume and tumor firmness [127]. Consequently, exploring targeted tumor stroma therapy strategies represents an imperative new direction in PA treatment. A critical consideration in this approach is determining whether the stroma exerts a supportive or suppressive influence on tumor growth. While reducing tumor stiffness and collagen content, collagen degradation via MMP overexpression may paradoxically induce angiogenesis and exacerbate tumor invasiveness [125,128]. Furthermore, it remains to be elucidated whether collagen degradation fragments continue to promote tumor angiogenesis and invasion in PAs, as has been observed in pancreatic cancer, where cleaved collagen promotes tumor metastasis and growth [64]. Additionally, the potential for immune evasion following collagen depletion requires further investigation, given reports in pancreatic cancer indicating that collagen depletion can suppress immune surveillance and diminish survival [129]. Therefore, a viable strategy may involve carefully balancing the content, crosslinking, alignment, and distribution of collagen within the PA microenvironment.

Despite these concerns, experimental targets on collagen or ECM components have been explored in PAs. Our team identified sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, as a potential therapy for reducing tumor stiffness via multi-omics investigation [130]. Preclinical studies (in GH3 cell lines and xenograft PA models) further demonstrated that sunitinib could inhibit tumor growth and reduce tumor stiffness, potentially by influencing the extracellular matrix [130]. Additionally, research explores inhibiting enzymes like P4HA3, crucial for collagen synthesis, and promoting the expression of tumor-suppressing COL6A6 to normalize ECM composition and potentially block pro-tumorigenic pathways [15]. LOX enzymes are responsible for cross-linking collagen, contributing to ECM stiffness. While not yet in clinical trials for PAs, inhibition of LOX is an area of interest in other cancers to reduce tumor stiffness and invasiveness [131]. Given that LOX expression levels increase in stiffer PA matrices, targeting LOX could be a future strategy for PAs.

Immunotherapy response prediction

Immunotherapy represents a promising approach for treating refractory pituitary adenomas. However, a systematic review of 24 patients indicated that only approximately 50 percent achieved disease control [132]. A major challenge remains in identifying the patient population most likely to benefit from immunotherapy.

Collagen has demonstrated potential in predicting therapy responsiveness across multiple tumor types. In lung cancer, increased collagen levels promote resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, while targeting lysyl oxidase-like two (LOXL2), an enzyme that facilitates collagen crosslinking, enhances T cell infiltration, and sensitizes resistant tumors to anti-PD-1 therapy [100]. In triple-negative breast cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, linearly aligned rather than wavy collagen, has been associated with reduced responsiveness to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) due to its inhibitory effects on T cell infiltration [4,92,133]. In PAs, tumors with increased stiffness and higher TAF infiltration have demonstrated decreased responses to immunotherapy [130]. However, further research is required to elucidate the relationship between collagen and ICI responsiveness to refine patient selection and optimize treatment outcomes.

Conclusions and future directions

Collagen plays multifaceted roles in PA progression, acting as both a structural scaffold and a biochemical regulator. Within PAs, collagen undergoes heterogeneous alterations in its composition and content, coinciding with the dynamic remodeling of collagen-producing cells. While collagen generally supports tumor growth, its influence on PA cell invasion remains inconsistent. Intriguingly, collagen fragments, along with their associated collagenase, may contribute to PA invasiveness. Furthermore, collagen modulates hormone production in PAs and potentially functions as an immune barrier. By trapping immune cells and facilitating immune evasion through receptor-mediated interactions, collagen may contribute to the complex immunological heterogeneity observed across different PA subtypes. Metabolically, collagen may serve as an energy substrate or reprogram metabolic pathways to sustain PA proliferation.

Clinically, radiological assessments of collagen content provide preoperative insights into tumor consistency, while serum collagen shows promise as a non-invasive diagnostic biomarker. Therapeutic strategies targeting collagen synthesis, degradation, or mechanical signaling pathways warrant exploration, with potential applications in chemotherapy enhancement and immunotherapy response prediction.

These diverse functions highlight collagen's crucial role in orchestrating PA biology and tumor progression through structural, biochemical, metabolic, and immunological mechanisms. Future research should focus on elucidating subtype-specific collagen signatures and developing precision therapies that exploit collagen's dual role as a pathological driver and a potential therapeutic target in PA management.

Funding

This work was supported from the Yinhua Public Welfare Foundation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jie Liu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization. Yong Yao: Supervision, Conceptualization. Lian Duan: Supervision. Lin Lu: Supervision. Huijuan Zhu: Supervision. Yongning Li: Supervision, Conceptualization. Jun Gao: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

This article is part of a special issue entitled: ‘Onco-Endocrinology’ published in Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology.

Contributor Information

Yongning Li, Email: liyongning@pumch.cn.

Jun Gao, Email: gaoj@pumch.cn.

References

- 1.Melmed S. Pituitary-tumor endocrinopathies. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:937–950. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1810772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tritos N.A., Miller K.K. Diagnosis and management of pituitary adenomas: a review. JAMA. 2023;329:1386–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ilie MD, Vasiljevic A, Raverot G, Bertolino P. The microenvironment of pituitary tumors-biological and therapeutic implications. Cancers (Basel) 11; 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11101605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Su H., Karin M. Collagen architecture and signaling orchestrate cancer development. Trends Cancer. 2023;9:764–773. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2023.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu S., Gu M., Wu K., Li G. Unraveling the role of hydroxyproline in maintaining the thermal stability of the collagen triple helix structure using simulation. J Phys Chem B. 2019;123:7754–7763. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b05006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricard-Blum S. The collagen family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceylan S., Anik I., Koc K., Kokturk S., Ceylan S., Cine N., et al. Microsurgical anatomy of membranous layers of the pituitary gland and the expression of extracellular matrix collagenous proteins. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153:2435–2443. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1182-3. discussion 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tofrizal A., Fujiwara K., Yashiro T., Yamada S. Alterations of collagen-producing cells in human pituitary adenomas. Med Mol Morphol. 2016;49:224–232. doi: 10.1007/s00795-016-0140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J., Liu J., Zhang H., Wang J., Hua H., Jiang Y. The role of network-forming collagens in cancer progression. Int J Cancer. 2022;151:833–842. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarzembowski J., Lloyd R., Mckeever P. Type IV collagen immunostaining is a simple, reliable diagnostic tool for distinguishing between adenomatous and normal pituitary glands. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:931–935. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-931-TICIIA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Q., Li X. Molecular network basis of invasive pituitary adenoma: a review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:7. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tallant C., Marrero A., Gomis-Ruth F.X. Matrix metalloproteinases: fold and function of their catalytic domains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mochizuki S., Okada Y. ADAMs in cancer cell proliferation and progression. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J., Voellger B., Benzel J., Schlomann U., Nimsky C., Bartsch J.W., et al. Metalloproteinases ADAM12 and MMP-14 are associated with cavernous sinus invasion in pituitary adenomas. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:1327–1339. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long R., Liu Z., Li J., Yu H. COL6A6 interacted with P4HA3 to suppress the growth and metastasis of pituitary adenoma via blocking PI3K-akt pathway. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11:8845–8859. doi: 10.18632/aging.102300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie T., Gao Y., Hu J., Luo R., Guo Y., Xie Q., et al. Increased matrix stiffness in pituitary neuroendocrine tumors invading the cavernous sinus is activated by TAFs: focus on the mechanical signatures. Endocrine. 2024 doi: 10.1007/s12020-024-04022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shoshan S., Finkelstein S. Lysyl oxidase: a pituitary hormone-dependent enzyme. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;439:358–362. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(76)90071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tofrizal A., Fujiwara K., Azuma M., Kikuchi M., Jindatip D., Yashiro T., et al. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase-expressing cells in human anterior pituitary and pituitary adenoma. Med Mol Morphol. 2017;50:145–154. doi: 10.1007/s00795-017-0155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H., Li W.S., Shi D.J., Ye Z.P., Tai F., He H.Y., et al. Correlation of MMP(1) and TIMP (1) expression with pituitary adenoma fibrosis. J Neurooncol. 2008;90:151–156. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Principe M., Chanal M., Ilie M.D., Ziverec A., Vasiljevic A., Jouanneau E., et al. Immune landscape of pituitary tumors reveals association between macrophages and gonadotroph tumor invasion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa520. 105:https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao Y., Li J., Cheng W., Diao T., Liu H., Bo Y., et al. Cross-tissue human fibroblast atlas reveals myofibroblast subtypes with distinct roles in immune modulation. Cancer Cell. 2024;42(1764–83):e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2024.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li P., Zhang D., Ma S., Kang P., Zhang C., Mao B., et al. Consistency of pituitary adenomas: Amounts of collagen types I and III and the predictive value of T2WI MRI. Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:1255. doi: 10.3892/etm.2021.10690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potthoff T.E., Walter C., Jeising D., Munter D., Verma A., Suero Molina E., et al. Single-cell transcriptomics link gene expression signatures to clinicopathological features of gonadotroph and lactotroph PitNET. J Transl Med. 2024;22:1027. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05821-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marques P., Barry S., Carlsen E., Collier D., Ronaldson A., Awad S., et al. Pituitary tumour fibroblast-derived cytokines influence tumour aggressiveness. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2019;26:853–865. doi: 10.1530/ERC-19-0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyu L., Jiang Y., Ma W., Li H., Liu X., Li L., et al. Single-cell sequencing of PIT1-positive pituitary adenoma highlights the pro-tumour microenvironment mediated by IFN-gamma-induced tumour-associated fibroblasts remodelling. Br J Cancer. 2023;128:1117–1133. doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-02126-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohlund D., Handly-Santana A., Biffi G., Elyada E., Almeida A.S., Ponz-Sarvise M., et al. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. 2017;214:579–596. doi: 10.1084/jem.20162024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forsthuber A., Aschenbrenner B., Korosec A., Jacob T., Annusver K., Krajic N., et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast subtypes modulate the tumor-immune microenvironment and are associated with skin cancer malignancy. Nat Commun. 2024;15:9678. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-53908-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makareeva E., Han S., Vera J.C., Sackett D.L., Holmbeck K., Phillips C.L., et al. Carcinomas contain a matrix metalloproteinase-resistant isoform of type I collagen exerting selective support to invasion. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4366–4374. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuchenbauer F., Hopfner U., Stalla J., Arzt E., Stalla G.K., Paez-Pereda M. Extracellular matrix components regulate ACTH production and proliferation in corticotroph tumor cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;175:141–148. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azorin E., Solano-Agama C., Mendoza-Garrido M.E. The invasion mode of GH(3) cells is conditioned by collagen subtype, and its efficiency depends on cell-cell adhesion. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;528:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azorin E., Romero-Perez B., Solano-Agama C., De La Vega M.T., Toriz C.G., Reyes-Marquez B., et al. GH3 tumor pituitary cell cytoskeleton and plasma membrane arrangement are determined by extracellular matrix proteins: implications on motility, proliferation and hormone secretion. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2014;6:66–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azorin E., Gonzalez-Martinez P.R., Azorin J. Collagen I confers gamma radiation resistance. Appl Radiat Isot. 2012;71(Suppl):71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalluri R. Basement membranes: structure, assembly and role in tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:422–433. doi: 10.1038/nrc1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niland S., Riscanevo A.X., Eble J.A. Matrix metalloproteinases shape the tumor microenvironment in cancer progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 doi: 10.3390/ijms23010146. 23:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23010146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner H.E., Nagy Z., Esiri M.M., Harris A.L., Wass J.A. Role of matrix metalloproteinase 9 in pituitary tumor behavior. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2931–2935. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.8.6754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawamoto H., Uozumi T., Kawamoto K., Arita K., Yano T., Hirohata T. Type IV collagenase activity and cavernous sinus invasion in human pituitary adenomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1996;138:390–395. doi: 10.1007/BF01420300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong J., Zhao Y., Abdel-Fattah R., Amos S., Xiao A., Lopes M.B., et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9, a potential biological marker in invasive pituitary adenomas. Pituitary. 2008;11:37–48. doi: 10.1007/s11102-007-0066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hussaini I.M., Trotter C., Zhao Y., Abdel-Fattah R., Amos S., Xiao A., et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is differentially expressed in nonfunctioning invasive and noninvasive pituitary adenomas and increases invasion in human pituitary adenoma cell line. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:356–365. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu W., Kunishio K., Matsumoto Y., Okada M., Nagao S. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression correlates with cavernous sinus invasion in pituitary adenomas. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:791–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu H.Y., Gu W.J., Wang C.Z., Ji X.J., Mu Y.M. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and -2 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in invasive pituitary adenomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3904. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malik M.T., Kakar S.S. Regulation of angiogenesis and invasion by human Pituitary tumor transforming gene (PTTG) through increased expression and secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) Mol Cancer. 2006;5:61. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garnero P., Ferreras M., Karsdal M.A., Nicamhlaoibh R., Risteli J., Borel O., et al. The type I collagen fragments ICTP and CTX reveal distinct enzymatic pathways of bone collagen degradation. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:859–867. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H., Zhang S., Wu T., Lv Z., Ba J., Gu W., et al. Expression and clinical significance of Cathepsin K and MMPs in invasive non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Front Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.901647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu H., Wang P., Li J., Zhao J., Mu Y., Gu W. Role of cathepsin K in bone invasion of pituitary adenomas: a dual mechanism involving cell proliferation and osteoclastogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2025;217443 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2025.217443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu H.L., Valiathan R.R., Arkwright R., Sohail A., Mihai C., Kumarasiri M., et al. Discoidin domain receptors: unique receptor tyrosine kinases in collagen-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:7430–7437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.444158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coelho N.M., Arora P.D., Van Putten S., Boo S., Petrovic P., Lin A.X., et al. Discoidin domain receptor 1 mediates myosin-dependent collagen contraction. Cell Rep. 2017;18:1774–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walsh L.A., Nawshad A., Medici D. Discoidin domain receptor 2 is a critical regulator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Matrix Biol. 2011;30:243–247. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida D., Teramoto A. Enhancement of pituitary adenoma cell invasion and adhesion is mediated by discoidin domain receptor-1. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:29–40. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li S., Zhang Z., Xue J., Guo X., Liang S., Liu A. Effect of hypoxia on DDR1 expression in pituitary adenomas. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:2433–2438. doi: 10.12659/MSM.894205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dagamajalu S., Rex D., a B, Suchitha G.P., Rai A.B., Kumar S., Joshi S., Raju R., Prasad T.S.K. A network map of discoidin domain receptor 1(DDR1)-mediated signaling in pathological conditions. J Cell Commun Signal. 2023;17:1081–1088. doi: 10.1007/s12079-022-00714-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cooper J., Giancotti F.G. Integrin signaling in cancer: mechanotransduction, stemness, epithelial plasticity, and therapeutic resistance. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:347–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu X., Cai J., Zuo Z., Li J. Collagen facilitates the colorectal cancer stemness and metastasis through an integrin/PI3K/AKT/Snail signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;114 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Y., Zhang J., Chen Y., Sohel H., Ke X., Chen J., et al. The correlation and role analysis of COL4A1 and COL4A2 in hepatocarcinogenesis. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:204–223. doi: 10.18632/aging.102610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsuoka T., Yashiro M., Nishioka N., Hirakawa K., Olden K., Roberts J.D. PI3K/Akt signalling is required for the attachment and spreading, and growth in vivo of metastatic scirrhous gastric carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1535–1542. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng T., Zheng Z., Zhou H., Guo Y., Li S. The multifaceted roles of COL4A4 in lung adenocarcinoma: an integrated bioinformatics and experimental study. Comput Biol Med. 2024;170 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Derwich A., Sykutera M., Brominska B., Rubis B., Ruchala M., Sawicka-Gutaj N. The role of activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAF/MEK/ERK pathways in aggressive pituitary adenomas-new potential therapeutic approach-a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 doi: 10.3390/ijms241310952. 24:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241310952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cao C., Wang W., Ma C., Jiang P. Computational analysis identifies invasion-associated genes in pituitary adenomas. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:1977–1982. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mete O., Hayhurst C., Alahmadi H., Monsalves E., Gucer H., Gentili F., et al. The role of mediators of cell invasiveness, motility, and migration in the pathogenesis of silent corticotroph adenomas. Endocr Pathol. 2013;24:191–198. doi: 10.1007/s12022-013-9270-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xing B., Lei Z., Wang Z., Wang Q., Jiang Q., Zhang Z., et al. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 22 activates integrin beta1 through its disintegrin domain to promote the progression of pituitary adenoma. Neuro Oncol. 2024;26:137–152. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noad148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maller O., Drain A.P., Barrett A.S., Borgquist S., Ruffell B., Zakharevich I., et al. Tumour-associated macrophages drive stromal cell-dependent collagen crosslinking and stiffening to promote breast cancer aggression. Nat Mater. 2021;20:548–559. doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-00849-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pickup M.W., Laklai H., Acerbi I., Owens P., Gorska A.E., Chytil A., et al. Stromally derived lysyl oxidase promotes metastasis of transforming growth factor-beta-deficient mouse mammary carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5336–5346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Madsen D.H., Jurgensen H.J., Siersbaek M.S., Kuczek D.E., Grey Cloud L., Liu S., et al. Tumor-associated macrophages derived from circulating inflammatory monocytes degrade collagen through cellular uptake. Cell Rep. 2017;21:3662–3671. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hsu K.S., Dunleavey J.M., Szot C., Yang L., Hilton M.B., Morris K., et al. Cancer cell survival depends on collagen uptake into tumor-associated stroma. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7078. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34643-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Su H., Yang F., Fu R., Trinh B., Sun N., Liu J., et al. Collagenolysis-dependent DDR1 signalling dictates pancreatic cancer outcome. Nature. 2022;610:366–372. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05169-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones V.A., Patel P.M., Gibson F.T., Cordova A., Amber K.T. The role of collagen XVII in cancer: squamous cell carcinoma and beyond. Front Oncol. 2020;10:352. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang J., Pan W. The biological role of the collagen alpha-3 (VI) chain and its cleaved C5 domain fragment endotrophin in cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:5779–5793. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S256654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eieland A.K., Normann K.R., Sundaram A.Y.M., Nyman T.A., Oystese K., a B, Lekva T., Berg J.P., Bollerslev J., Olarescu N.C. Distinct pattern of endoplasmic reticulum protein processing and extracellular matrix proteins in functioning and silent corticotroph pituitary adenomas. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/cancers12102980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Romer A.M.A., Thorseth M.L., Madsen D.H. Immune modulatory properties of collagen in cancer. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.791453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Horn L.A., Chariou P.L., Gameiro S.R., Qin H., Iida M., Fousek K., et al. Remodeling the tumor microenvironment via blockade of LAIR-1 and TGF-beta signaling enables PD-L1-mediated tumor eradication. J Clin Invest. 2022 doi: 10.1172/JCI155148. 132:https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI155148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hartmann N., Giese N.A., Giese T., Poschke I., Offringa R., Werner J., et al. Prevailing role of contact guidance in intrastromal T-cell trapping in human pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:3422–3433. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Flies D.B., Langermann S., Jensen C., Karsdal M.A., Willumsen N. Regulation of tumor immunity and immunotherapy by the tumor collagen extracellular matrix. Front Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1199513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo X., Chang M., Li W., Qian Z., Guo H., Xie C., et al. Immune atlas of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors highlights endocrine-driven immune signature and therapeutic implication. Cell Rep. 2025;44 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guo X., Yang Y., Qian Z., Chang M., Zhao Y., Ma W., et al. Immune landscape and progress in immunotherapy for pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Lett. 2024;592 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lu J.Q., Adam B., Jack A.S., Lam A., Broad R.W., Chik C.L. Immune cell infiltrates in pituitary adenomas: more macrophages in larger adenomas and more T cells in growth hormone adenomas. Endocr Pathol. 2015;26:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s12022-015-9383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou W., Zhang C., Zhang D., Peng J., Ma S., Wang X., et al. Comprehensive analysis of the immunological landscape of pituitary adenomas: implications of immunotherapy for pituitary adenomas. J Neurooncol. 2020;149:473–487. doi: 10.1007/s11060-020-03636-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xi Z., Jones P.S., Mikamoto M., Jiang X., Faje A.T., Nie C., et al. The upregulation of molecules related to tumor immune escape in human pituitary adenomas. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.726448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Z., Guo X., Gao L., Deng K., Lian W., Bao X., et al. The immune profile of pituitary adenomas and a novel immune classification for predicting immunotherapy responsiveness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:e3207–e3223. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Suteau V., Collin A., Menei P., Rodien P., Rousselet M.C., Briet C. Expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) in human pituitary neuroendocrine tumor. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69:2053–2061. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Turchini J., Sioson L., Clarkson A., Sheen A., Gill A.J. PD-L1 is preferentially expressed in PIT-1 positive pituitary neuroendocrine tumours. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:408–414. doi: 10.1007/s12022-021-09673-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bagati A., Kumar S., Jiang P., Pyrdol J., Zou A.E., Godicelj A., et al. Integrin alphavbeta6-TGFbeta-SOX4 pathway drives immune evasion in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(54–67):e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vannini A., Leoni V., Barboni C., Sanapo M., Zaghini A., Malatesta P., et al. alphavbeta3-integrin regulates PD-L1 expression and is involved in cancer immune evasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:20141–20150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901931116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu F., Wu Q., Dong Z., Liu K. Integrins in cancer: Emerging mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Ther. 2023;247 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen Y., Yang S., Tavormina J., Tampe D., Zeisberg M., Wang H., et al. Oncogenic collagen I homotrimers from cancer cells bind to alpha3beta1 integrin and impact tumor microbiome and immunity to promote pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(818–34):e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Su W., Ye Z., Liu J., Deng K., Liu J., Zhu H., et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptome analyses reveal tumor heterogeneity and immune remodeling involved in pituitary neuroendocrine tumor progression. Nat Commun. 2025;16:5007. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-60028-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kramerova I., Kumagai-Cresse C., Ermolova N., Mokhonova E., Marinov M., Capote J., et al. Spp1 (osteopontin) promotes TGFbeta processing in fibroblasts of dystrophin-deficient muscles through matrix metalloproteinases. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28:3431–3442. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu X., Lin J., Wang J., Wang Y., Zhu Y., Wang J., et al. SPP1 expression indicates outcome of immunotherapy plus tyrosine kinase inhibition in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2024;20 doi: 10.1080/21645515.2024.2350101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Klement J.D., Paschall A.V., Redd P.S., Ibrahim M.L., Lu C., Yang D., et al. An osteopontin/CD44 immune checkpoint controls CD8+ T cell activation and tumor immune evasion. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:5549–5560. doi: 10.1172/JCI123360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sirvent A., Espie K., Papadopoulou E., Naim D., Roche S. New functions of DDR1 collagen receptor in tumor dormancy, immune exclusion and therapeutic resistance. Front Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.956926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu J., Chiang H.C., Xiong W., Laurent V., Griffiths S.C., Dulfer J., et al. A highly selective humanized DDR1 mAb reverses immune exclusion by disrupting collagen fiber alignment in breast cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2023 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2023-006720. 11:https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2023-006720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang S., Fu Y., Kuerban K., Liu J., Huang X., Pan D., et al. Discoidin domain receptor 1 is a potential target correlated with tumor invasion and immune infiltration in gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.933165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Duan X., Xu X., Zhang Y., Gao Y., Zhou J., Li J. DDR1 functions as an immune negative factor in colorectal cancer by regulating tumor-infiltrating T cells through IL-18. Cancer Sci. 2022;113:3672–3685. doi: 10.1111/cas.15533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sun X., Wu B., Chiang H.C., Deng H., Zhang X., Xiong W., et al. Tumour DDR1 promotes collagen fibre alignment to instigate immune exclusion. Nature. 2021;599:673–678. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.You S., Kim M., Hoi X.P., Lee Y.C., Wang L., Spetzler D., et al. Discoidin domain receptor-driven gene signatures as markers of patient response to anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114:1380–1391. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vehlow A., Klapproth E., Jin S., Hannen R., Hauswald M., Bartsch J.W., et al. Interaction of discoidin domain receptor 1 with a 14-3-3-beclin-1-akt1 complex modulates glioblastoma therapy sensitivity. Cell Rep. 2019;26(3672–83):e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Juric V., O'sullivan C., Stefanutti E., Kovalenko M., Greenstein A., Barry-Hamilton V., et al. MMP-9 inhibition promotes anti-tumor immunity through disruption of biochemical and physical barriers to T-cell trafficking to tumors. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Melani C., Sangaletti S., Barazzetta F.M., Werb Z., Colombo M.P. Amino-biphosphonate-mediated MMP-9 inhibition breaks the tumor-bone marrow axis responsible for myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion and macrophage infiltration in tumor stroma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11438–11446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pascoal Ramos M.I., Van Der Vlist M., Meyaard L. Inhibitory pattern recognition receptors: lessons from LAIR1. Nat Rev Immunol. 2025 doi: 10.1038/s41577-025-01181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Park J.E., Brand D.D., Rosloniec E.F., Yi A.K., Stuart J.M., Kang A.H., et al. Leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor 1 inhibits T-cell signaling by decreasing protein phosphorylation in the T-cell signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:2239–2247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Meyaard L. The inhibitory collagen receptor LAIR-1 (CD305) J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:799–803. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Peng D.H., Rodriguez B.L., Diao L., Chen L., Wang J., Byers L.A., et al. Collagen promotes anti-PD-1/PD-L1 resistance in cancer through LAIR1-dependent CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4520. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vijver S.V., Singh A., Mommers-Elshof E., Meeldijk J., Copeland R., Boon L., et al. Collagen fragments produced in cancer mediate T cell suppression through leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor 1. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.733561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ramos M.I.P., Tian L., De Ruiter E.J., Song C., Paucarmayta A., Singh A., et al. Cancer immunotherapy by NC410, a LAIR-2 Fc protein blocking human LAIR-collagen interaction. Elife. 2021 doi: 10.7554/eLife.62927. 10:https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nemeth K., Schoppet M., Al-Fakhri N., Helas S., Jessberger R., Hofbauer L.C., et al. The role of osteoclast-associated receptor in osteoimmunology. J Immunol. 2011;186:13–18. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liao X., Bu Y., Zhang Y., Xu B., Liang J., Jia Q., et al. OSCAR facilitates malignancy with enhanced metastasis correlating to inhibitory immune microenvironment in multiple cancer types. J Cancer. 2021;12:3769–3780. doi: 10.7150/jca.51964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Larsen A.M.H., Kuczek D.E., Kalvisa A., Siersbaek M.S., Thorseth M.L., Johansen A.Z., et al. Collagen density modulates the immunosuppressive functions of macrophages. J Immunol. 2020;205:1461–1472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Morris B.A., Burkel B., Ponik S.M., Fan J., Condeelis J.S., Aguirre-Ghiso J.A., et al. Collagen matrix density drives the metabolic shift in breast cancer cells. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Olivares O., Mayers J.R., Gouirand V., Torrence M.E., Gicquel T., Borge L., et al. Collagen-derived proline promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell survival under nutrient limited conditions. Nat Commun. 2017;8:16031. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Feng J., Gao H., Zhang Q., Zhou Y., Li C., Zhao S., et al. Metabolic profiling reveals distinct metabolic alterations in different subtypes of pituitary adenomas and confers therapeutic targets. J Transl Med. 2019;17:291. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-2042-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kinali B., Senoglu M., Karadag F.K., Karadag A., Middlebrooks E.H., Oksuz P., et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A expression in pituitary adenomas: association with pathological, clinical, and radiological features. World Neurosurg. 2019;121:e716–e722. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yoshida D., Teramoto A. Elevated cell invasion is induced by hypoxia in a human pituitary adenoma cell line. Cell Adh Migr. 2007;1:43–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]