Abstract

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a motor neuron disease characterized by progressive degeneration of motor neurons in the cerebral cortex, brainstem, and spinal cord, eventually leading to paralysis, respiratory failure, and death. Currently, no effective treatment exists for ALS.

Methods

This study examined the therapeutic potential of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells (HUMSCs) by transplanting 2 × 10⁶ HUMSCs into the spinal canal of transgenic mice expressing mutant human superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) at 8 weeks of age.

Results

Survival analysis showed that the SOD1 group lived up to 171 days, while the SOD1 + HUMSCs group survived up to 199 days, extending lifespan by 17 days on average. Motor function tests, including rotarod performance, grip strength, open field activity, and balance beam tests, demonstrated that while the SOD1 group experienced progressive decline, the SOD1 + HUMSCs group showed improvement. Electrophysiological assessments at 20 weeks of age revealed weak muscle action potential in the SOD1 group, whereas the SOD1 + HUMSCs group exhibited noticeable improvements. Histological analysis indicated significant spinal cord atrophy in the SOD1 group, while HUMSCs transplantation mitigated this degeneration. Moreover, HUMSCs reduced blood-spinal cord barrier leakage and T lymphocyte infiltration, alleviating inflammation. The number and size of activated microglia and astrocytes increased in the SOD1 group but were reduced with HUMSCs treatment. Additionally, HUMSCs preserved more motor neurons in the anterior horns.

Conclusion

Collectively, transplantation of HUMSCs effectively reduced inflammatory reaction in spinal cord, decreased loss of neurons, ameliorated disease deterioration, and extended life span, suggesting that it could serve as a new direction of ALS treatment to improve patients’ quality of life or behavioral function.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13287-025-04485-1.

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS, SOD1, Umbilical mesenchymal stromal cells, Cell transplantation, Neuronal inflammation

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease that is resulted from degeneration and death of upper and lower motor neurons, leading to muscle atrophy, spasticity, respiratory failure, and eventually death [1–3]. The incidence of ALS is approximately 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 people annually, with an age of 55 to 75 years at the time of first onset. Patients with genetic forms of ALS are more likely to have an earlier onset of symptoms [4]. The male to female ratio is between 1.5 and 2.5, and the median survival from onset to death ranges from 3 to 5 years. Currently, the therapeutic effects of available medications are very limited, and ALS is therefore considered as one of the most important and difficult-to-treat diseases in the twenty-first century by World Health Organization [5].

Around 90% to 95% of ALS patients have no family history but only considered as sporadic cases. The cause of disease is still indefinite and may involve factors such as cigarette smoking, aging, exposure to chemicals or radiation, and head trauma [6, 7]. Approximately 5% to 10% of ALS patients are familial. A number of genetic defects are found to be ALS-associated, of which mutation or deletion of superoxide dismutase (SOD) on chromosome 21 was first identified and is the most common causative gene among Asian and North American patients with familial ALS [8]. SOD1 is a vital antioxidant enzyme in the cytosol that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide (O2 −) radical into less reactive hydrogen peroxide H2O2, which is subsequently converted into unharmful H2O by catalase. This is a mechanism adopted for superoxide clearance in order to protect cells from oxidative stress-induced damages. There is a type of ALS that is caused by SOD1 gene mutation, resulting in the decreased ability in free radicals and leading to impairment and death of neuronal cells [9].

The central nervous system (CNS) develops a protective mechanism in order to prevent penetration of noxious substances from blood streams to neuronal tissues. The blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB) is a selective permeable barrier that can block entry of most medications, proteins, or large molecules and hence their subsequent influences on the CNS. Three main layers constitutes the BSCB and form a protective barrier for the spinal cord, including the first layer of the tight junction of vascular endothelial cells, the second layer of continuous basal membrane that lies externally to the endothelial cells, and the third layer of astrocytic end feet or pericytes covering capillaries. However, the BSCB is found to be damaged in patients and rodents with ALS [10]. Due to the BSCB breakdown, immune cells such as T cells and microglia enter the spinal cord and extensively infiltrate the CNS. The infiltration of these immune cells accompanies with cytokine release, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), resulting in the activation of microglia, which then release INF-γ, TNF-α, and reactive nitrogen species to activate astroglia. The crosstalk between astroglia and microglia further enhances each other’s activation and promotes neuro-inflammation, leading to impairment or death of neuronal cells [11]. Subsequently, fibrosis, atrophy, and death occur to myocytes innervated by these neurons [12].

The emergence of stem cell research and stem cell transplantation brings hope for ALS patients. Our study team actively investigate the therapeutic effects of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells (HUMSCs) derived from Wharton’s jelly for various types of diseases. Umbilical cord is a waste following delivery and is easier to obtain compared to embryos or bone marrow MSCs. In previous studies, we transplanted HUMSCs into the spinal cord, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum to effectively treat spinal cord injury, stroke, epilepsy, and spinocerebellar ataxia, respectively [13–17]. In fact, we not only applied HUMSCs transplantation in treating CNS diseases but also in rat diabetes [18], liver fibrosis [19], and pulmonary fibrosis [20–22] with prominent therapeutic effects. Given that HUMSCs transplanted into various types of organs in rats are able to survive, it demonstrates that HUMSCs does not cause immune responses or rejections in allogeneic or xenogeneic hosts. Hence, HUMSCs could serve as graft materials for clinical medicine.

In the present study, HUMSCs were transplanted into ALS transgenic mice to investigate their therapeutic effects. Male SOD1-G93A transgenic founder’s male (SOD1) progeny was selected by genetic tests for those expressing SOD1-G93A. A total of 2 × 106 HUMSCs were implanted into the spinal canal of the 8-week-old ALS mice, which were then sacrificed at 20 weeks of age. The results indicated that HUMSCs transplantation can effectively ameliorate deterioration of the disease and extend the life span of SOD1 mice.

Materials and Methods

In vitro Culture of HUMSCs

In the delivery room, umbilical cords were obtained, collected and preserved aseptically in Hanker’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) at 4 ℃. Within 24 h, HUMSCs were isolated and cultured. Umbilical cord was immersed in 75% alcohol for disinfection. Within a laminar flow, the umbilical cord was placed in HBSS and cut vertically with sterilized apparatus. Umbilical arteries and vein were removed, and mesenchymal tissues (Wharton’s jelly) were isolated, cut into cubes with the width around 1 ~ 2 mm, and placed in a 10-cm culture dish. HUMSCs migrated from the mesenchymal tissue and proliferated. Finally, HUMSCs were re-suspend for cell counting, culturing, or cryopreservation in liquid nitrogen for later use.

HUMSCs were isolated from Wharton's jelly in umbilical cord and expanded in vitro. The HUMSCs isolated in this study represent heterogeneous and non-clonal cell populations, consistent with the consensus presented in published reviews [23, 24]. The 5 ~ 6th passage HUMSCs were harvested for transplantation into SOD1 transgenic mice in this study. Flow cytometric analysis of Passage 3 (as a control) and Passage 6 HUMSCs revealed consistent and high expression of CD105, CD90, CD73, and CD44, while lacking expression of hematopoietic lineage markers (CD34 and CD45) (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Chromosome karyotyping using G-banding staining revealed no chromosomal abnormalities in HUMSCs at either Passage 3 or 6, indicating the absence of numerical or structural aberrations during in vitro expansion (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Moreover, the assay of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) showed only very faint blue staining in the cytoplasm of both Passage 3 and 6 of HUMSCs. In contrast, HUMSCs treated with 250 μM H₂O₂ as the positive control exhibited intense staining in nearly all cytoplasms (Supplemental Fig. 1C).

Experimental Animals

The experimental protocols complied with ARRIVE guidelines 2.0 (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments). SOD1-G93A transgenic mice is an ALS animal model that carries repetitive sequences of human SOD1 mutant, a point mutation at position 93 [25]. All male SOD1-G93A transgenic mice used in this study were kindly gifted from Professor Jun-An Chen of Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. Male SOD1-G93A transgenic mice were bred with female C57BL/6, and their male progeny of the same delivery carrying SOD1-G93A transgene were divided into a no-treatment group and a cell-transplantation group for behavioral and morphological analyses. Because the difficulty in collecting male SOD1-G93A transgenic mice, female SOD1-G93A mice of the same delivery were kept for survival analyses; that is, female SOD1-G93A mice were also divided into a no-treatment group and a cell-transplantation group and their age of death were recorded. Male mice without carrying SOD1-G93A transgene served as a reference group for behavioral and morphological analyses. Similarly, female mice without carrying SOD1-G93A transgene served as a reference group for survival analyses (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Mice were housed in a 45 × 24 × 20 transparent polycarbonate (PC) cage, with a 12-h light/dark cycle and controlled temperature (25 ± 2℃) and humidity (30%-70%). They had ad libitum access to food and water. Bedding materials were changed once every week.

Genetic Testing of Experimental Animals

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was applied for genetic testing. At 3 weeks of age, the genomic DNA was extracted from mice tail (about 1 cm in length) using DNA mini kit (Genoneid) and then the following primers were utilized for genetic testing:

Sense primer: 5’-CATCAGCCCTAATCCATCTGA-3’.

Anti-sense primer: 5’-CGCGACTAACAATCAAAGTGA-3’.

With the above primers, a PCR product of 236 bp indicated that the mice tested were carrying the vector and therefore were identified as SOD1-G93A transgenic mice.

Grouping of Experimental Animals

There were three study groups:

The first group was the Normal group (n = 11). Male SOD1-G93A transgenic mice were bred with female C57BL/6, and their male progeny of the same delivery not carrying SOD1-G93A transgene served as the Normal group. At 8 weeks of age, the spinal column was revealed and only saline of the same volume was administered intrathecally.

The second group was the SOD1 group (n = 11), the progeny of SOD1-G93A transgenic mice that carried SOD1-G93A transgene. They were randomly assigned to receive only an intrathecal injection of saline of the same volume at 8 weeks of age.

The third group was the SOD1 + HUMSCs group (n = 13). They were also the progeny of SOD1-G93A transgenic mice and carried SOD1-G93A transgene. They were randomly assigned to receive an intrathecal transplantation of 2 × 106 HUMSCs of the same volume at 8 weeks of age.

Starting from 4 weeks, the three experimental groups were weighed every week, and their behaviors were analyzed once every four weeks. Male SOD1-G93A transgenic mice were sacrificed at 20 weeks of age for analyzing changes in spinal cord phenotypes, whereas the female transgenic mice were not sacrificed but were followed up until death to observe their life span (n = 18) (Fig. 1a).

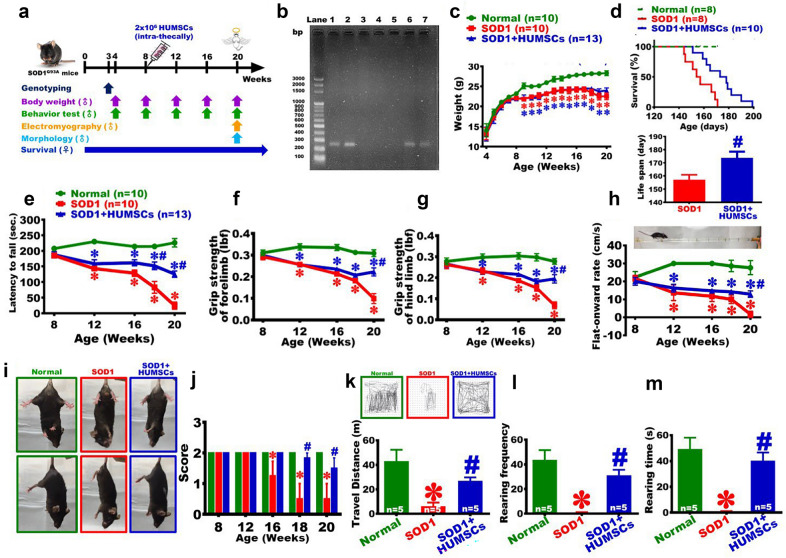

Fig. 1.

HUMSCs transplantation delayed motor performance decline in SOD1 mice. a Experiment flowchart. Genotyping was performed in 3-week-old mice. Body weight measurement and behavioral tests were performed starting from 4 weeks of age. At 20 weeks of age, male mice underwent muscle electrophysiological testing and were sacrificed and perfused. Life span was observed in female mice. b The tail biopsy obtained from SOD1 mice’s progeny were used for the confirmation of genotype of SOD1 mice. The PCR product was 236-bp. The results indicated that lanes 1, 2, 6, and 7 were of SOD1 mice. c Weekly mice body weight. d Survival and average life span. The results showed that HUMSCs transplantation prolonged life span in SOD1 mice. Motor performance was assessed and quantified via e rotarod test, f grip strength of forelimbs, g grip strength of hindlimbs, h pen test, i-j calf extension reflex, and k-m open field test, and the results demonstrated that HUMSCs transplantation delayed motor performance decline in SOD1 mice. *, versus the Normal group of the same time point, p < 0.05. #, versus the SOD1 group of the same time point, p < 0.05

Transplantation of HUMSCs

Eight-week-old mice were anaesthetized. HUMSCs were treated with 0.5% trypsin for 2.5 min. Trypsin was then neutralized by 10% FBS. The cells were centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 min to remove the supernatant, and the pelleted HUMSCs were obtained.

Laminae of mice T8 and T9 were removed, and 1 × 106 HUMSCs were injected intrathecally, toward the rostral and caudal location of the exposed spinal cord (a total of 2 × 106 HUMSCs for each transgenic mouse), respectively. The Normal and SOD1 groups also underwent the same procedure (removal of T8 and T9 laminae) and received 10-μL saline injection intrathecally.

Animal Behavioral Testing

Rotarod Test

The experimental animals were placed on an electric rotarod that accelerated from 4 to 40 rpm in 5 min, and the retention time was recorded to observe the animals’ forelimb and hindlimb coordination [17]. The rotarod test was performed when the mice reached 8 weeks of age. It was conducted at a frequency of 3 times per day for consecutive 3 days. There was a 15-min interval between each assessment so that the mice could have a rest between the tests. The average of 9 evaluations represented the mouse’s behavioral index of the given month. Afterwards, the test was performed once every 4 weeks until Week 20.

Grip Strength

The grip strength of mice forelimb and hindlimb was measured with a grip strength meter (MK-380CM/R, Sunpoint Scientific).

Extension Reflex

The extension reflex test was performed with the mouse suspended by the tail and the extension reflex of its hindlimbs observed. If both the right and left hindlimbs had normal extension reflex, a score of 2 was given. If only one of the hindlimbs showed extension reflex, it would be scored as 1. With no extension reflex observed in either of the hindlimbs, the score was 0 [26]. The test was performed once every 4 weeks until Week 20.

Pen Test

Mice were placed on one end of a round acrylic rod beam, which was 60 cm in length and 1.5 cm in diameter. The distance the mice traveled horizontally on the beam was observed. The distance was divided by time spent to obtain the flat-onward rate on the balance beam [17, 27]. The test was performed once every 4 weeks until Week 20 (Supplemental Video).

Open Field Test

Mice were placed in a plastic test box with a bottom area of 30 cm × 20 cm. The total distance travelled, rearing frequency, and rearing time during a 15-min period were recorded using the TRUSCAN software [17, 28]. The experiment was conducted in a light-protected and quiet environment to avoid causing any disturbance on mice activities. The test was performed once every 4 weeks until Week 20.

Measurement of Serum Biochemical Parameters

At 20 weeks of age, the mouse blood was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min, and the serum was collected and stored at -20 °C. The serum levels of Triglyceride, and Cholesterol were measured by LeZen Medical Technology Laboratory (Taipei).

Electrodiagnosis

Electrodiagnosis is an examination that applies a current to stimulate neurons and the electrophysiological changes of muscles are recorded with electrodes. It is used for assisting diagnosis of neuromuscular disease.

At 20 weeks of age, electrodes were inserted bilaterally of the fourth lumbar vertebra to give a 15-mA stimulus. The changes in action potentials of gastrocnemius muscles were recorded, and the latency, duration, and amplitude were measured [17, 29].

Sacrifice and Perfusion Fixation of Experimental Animals

Twenty-week-old mice were anaesthetized using isoflurane. An incision was made to the mouse’s xiphoid process of sternum. With a cut along the rib cage and as far as the front legs, the heart was revealed. The mouse’s left ventricle was punctured with a needle, perfused with 0.9% saline containing a vasodilator (0.2% sodium nitrate) and an anticoagulant (0.2% sodium citrate) to replace the blood, followed by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brain, spinal cord, and calf muscle tissues were than retrieved and placed in fixative solution for 24 h at 4℃.

Tissue Processing, Paraffin Embedding, and Sectioning

Brain, spinal cord, and gastrocnemius muscle were removed from the fixative solution, placed sequentially in 70%, 80%, 95% (I), and 95% (II) alcohols (set on a shaker for 20 min), and then dehydrated in 100% alcohol (6 times, 30 min each). After dehydration, tissues were placed in xylene for 1 min, which served as a mediator and helped penetration of paraffin into tissues; the process was completed while placed in a 68℃ oven. Finally, the tissues were embedded in paraffin and mice spinal cord and muscle tissues were sliced at 5-μm thickness to examine the pathological changes (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Cresyl Violet Staining

Cresyl violet can label polyribosome (i.e., Nissl body) of neuronal cells and can therefore be used to observe the morphology and number of neurons. Deparaffinized and rehydrated histological sections were stained in 1% cresyl violet solution for 30 min and then dehydrated in a series of increasing concentration of alcohol (50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100%; 30 s each). The sections were then submerged twice in xylene for 5 min each. Afterward, the slides were cover-slipped.

Immunohistochemical Staining

Histological sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and reacted with blocking solution (3% bovine serum albumin, 1% triton X-100, 5% FBS) for 1 h at room temperature. The primary mouse anti-NeuN (1:250, Millipore), goat anti-ChAT (1:100, Chemicon), rabbit anti-T cell CD3 (1:100, Sigma), rabbit anti-GFAP (1:1000, Chemicon), mouse anti-Iba1 (1:500, Abcam), rabbit anti-SQSTM1/ p62 (1:200, Abcam), and rabbit anti-SOD1 (1:500, Abcam) were then added to react for 12 h at 4℃. Subsequently, the corresponding secondary antibodies were added to react for 1 h at room temperature: goat anti-mouse IgG-conjugated biotin (1:250, Millipore), rabbit anti-goat IgG-conjugated biotin (1:250, Millipore), and goat anti-rabbit IgG-conjugated biotin (1:250, Sigma). The slides were then washed with 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS), reacted with avidin-biotinylated complex (ABC kit, Vector) for 1 h at room temperature, washed with 0.01 M PBS, and developed with DAB. After staining, the slides were dehydrated with a series of increasing concentration of alcohol, submerged in xylene, and cover-slipped.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining (HE Staining) for Gastrocnemius Histological Sections

Following deparaffinization and rehydration, histological sections were stained in hematoxylin for 5 min and washed in running water for 15 min. Subsequently, the slides were immersed in 1% acidic alcohol for 1 s, washed in running water for 15 min, followed by 3 min in 70% alcohol, stained in eosin for 1 min, and washed with running water for 15 min. The slides were then sequentially placed in 90% and 100% alcohol twice for 3 min each, submerged twice in xylene (5 min each), and finally cover-slipped.

Sirius Red Staining for Gastrocnemius Histological Sections

Following deparaffinization and rehydration, histological sections were stained in 1% Sirius Red for 14 min. The slides were then immersed in a series of alcohol solutions of increasing concentration for dehydration (50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100%; 30 s each), submerged twice in xylene (5 min each), and cover-slipped.

Immunohistochemical Staining for Gastrocnemius Histological Sections

Following deparaffinization and rehydration, histological sections were reacted with blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature. Histological sections were reacted with a primary antibody (rabbit anti-αSMA [1:300, Abcam]; rat anti-ED1 [1:50, Millipore]) for 12 h at 4℃, washed with 0.01 M PBS, and then reacted with a secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG-conjugated biotin [1:250, Sigma]; goat anti-rat IgG-conjugated biotin [1:250, Vector]) for 1 h at room temperature. Once reacted with avidin-biotinylated complex (ABC kit, Vector) for 1 h at room temperature, signals were developed with DAB, and the slides were cover-slipped.

Blood-spinal Cord Barrier Permeability Assay

Twenty-week-old mice were deeply anaesthetized and intraperitoneally injected with 0.2% Evans blue. After 3 h, the mice were perfused with saline to clear blood. After perfusion, the spinal cord was retrieved, grinded, and immersed in formamide 1 mL for 48 h at 60℃ to extract the dye in the spinal cord. After reaction, the formamide solution was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min, and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured by OD620 [30].

The value of absorbance was transformed to the absorbance of each gram of spinal cord. A higher value suggests a higher amount of dye penetrating into the spinal cord neuropia and indicates the BSCB is damaged to a higher extent.

Quantification of NF-kB in the Spinal Cord

The levels of mouse NF-kB were quantified using the FineTest® Mouse NFkB (Nuclear Factor Kappa B) ELISA Kit (Cat. No. EM1230, Wuhan Fine Biotech Co., Ltd., China). All reagents and procedures followed the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, standards and samples were added to pre-coated 96-well plates, followed by incubation with biotinylated antibody, HRP-streptavidin, and TMB substrate. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. The NF-kB concentrations were calculated from a standard curve. All reagents were used within their expiry dates and stored at 2–8 °C as recommended.

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription-polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Spinal cord tissues were placed in a mortar and grinded after adding liquid nitrogen. Next, TRIzol reagent (Sigma T9424) was added, and griding was continued to mix the reagent with tissues as complete as possible. The mixture was then centrifuged at 12,000 g at 4 ℃, and the supernatant was removed. Subsequently, the sample was washed with 75% alcohol. An adequate amount of diethyl pyrocarbonate was added to re-dissolve the sample, and the concentration of RNA was measured before use.

RT-PCR was performed by using 2 μg of RNA (Bionovas). After the cDNA was synthesized, 2 μg of DNA was subsequently used for PCR with the following primers:

| (1) | HUMAN RBFOX3 | 310 bp |

| F: 5’-ATCCAGTGGTCGGCGCAGTCTAC-3’ | ||

| R: 5’-TACGGGTCGGCAGCTGCGTA-3’ | ||

| (2) | HUMAN GFAP | 122 bp |

| F: 5’-CTGGAGAGGAAGATTGAGTCGC-3’ | ||

| R: 5’-ACGTCAAGCTCCACATGGACCT-3’ | ||

| (3) | MOUSE GAPDH | 223 bp |

| F: 5’- AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG -3’ | ||

| R: 5’- ACACATTGGGGGTAGGAACA -3’ | ||

| (4) | HUMAN GAPDH | 177 bp |

| F: 5’-TCCTCCACCTTTGACGCT-3’ | ||

| R: 5’-TCTTCCTCTTGTGCTCTTGC-3’ | ||

Quantification of Histochemical Staining

Spinal cord histological sections were stained with cresyl violet, which stained the cytoplasm in deep color and the grey matter and white matter were distinguished, allowing the quantification of spinal cord cross-sectional area and grey matter area at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections. Following immunostaining with anti-Iba1 and anti-GFAP, the percentage area of Iba1- and GFAP-positive fiber in the anterior horn of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections were quantified in spinal cord histological sections. Following immunostaining of anti-NeuN in spinal cord histological sections, the total number of neuronal cells in the anterior horn of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections were counted, and the distribution of neurons having perikarya of the greatest diameter were further analyzed. With spinal cord histological sections immunostained with anti-ChAT, the total number of motor neurons in the anterior horn of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections were counted. For quantifications mentioned above, there were 5–7 mice in each group, with 6 anterior horns of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections included for each mouse.

Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were expressed in mean SEM (Standard error of the mean). Comparisons between means were performed with one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA. Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test was then conducted for multiple comparisons. A minimum of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Confirmation of Transgenic Mice Carrying SOD1 Mutation by PCR

SOD1-G93A repetitive sequences were detected by the forward primer 5’-CATCAGCCCTAATCCATCTGA-3’ and the reverse primer 5’-CGCGACTAACAATCAAAGTGA-3’. With the PCR product of 236 bp, SOD1-G93A transgenic mice of lanes 1, 2, 6, and 7 were selected. Mice of the same delivery without carrying mutant gene (e.g., mice of lanes 3, 4, and 5) served as the Normal group (Fig. 1b).

Weight Change of SOD1 Mice

Mice were weighed weekly. The results indicated that the body weight increased with age in the Normal group, while only limited weight gain was noted in the SOD1 group starting from 8 weeks of age. For the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, its trend in weight gain was comparable to the SOD1 group; from 9 to 20 weeks of age, the body weight of the SOD1 + HUMSCs group was significantly lower than that of the Normal group (Fig. 1c).

Transplantation of HUMSCs Prolonged Life Span of SOD1 Mice

Life span was assessed in female mice. It revealed that the SOD1 group could only live up to 171 days, whereas the SOD1 + HUMSCs group could live up to 199 days. The mean lifespan was 157.00 ± 10.45 days in the SOD1 group and 173.80 ± 14.02 days in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group; there was an average of 17-day increase in life span in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group (Fig. 1d).

Transplantation of HUMSCs Increased Latency to Fall From Rotarod in SOD1 Mice

The results of rotarod test showed that the latency to fall was approximately 200 s in all three groups at 8 weeks of age, with no statistical differences found among the groups. As age increased over time, the latency remained at around 200 s in the Normal group. In the SOD1 group, the mobility deteriorated over time; at 12 weeks of age, the latency significantly decreased to 143.01 ± 14.98 secs; at 18 weeks, the motor performance dropped rapidly; at 20 weeks, the latency to fall was only 24.41 ± 28.37 secs. For the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, a marked decrease in latency was already observed at 12 weeks of age when compared with that of the Normal group; at 18 weeks, the latency remained at 152.20 ± 40.50 s, which was noticeably increased as compared to the SOD1 group. At 20 weeks of age, the latency to fall sustained at 125.29 ± 30.43 s in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group; the time was shorter than that of the Normal group but significantly higher than that of the SOD1 group. The results showed that HUMSCs transplantation extended latency to fall from rotarod in SOD1-G93A mice (Fig. 1e).

Transplantation of HUMSCs Lessened Loss of Grip Strength in SOD1 Mice

At 8 weeks of age, the grip strength of three groups ranged from 0.29 to 0.31 pound for forelimbs and from 0.26 to 0.28 pound for hindlimbs, with no statistical difference found. As age increased over time, the grip strength of forelimbs and hindlimbs remained stable in the Normal group (Fig. 1f and g). In the SOD1 group, the grip strength decreased to 0.26 ± 0.03 pound for forelimbs and to 0.23 ± 0.04 pound for hindlimbs at 12 weeks of age, which had already significantly differed from those of the Normal group. At 20 weeks of age, the grip strength of both forelimbs and hindlimbs of the SOD1 group sharply dropped to 0.10 ± 0.07 and 0.07 ± 0.05 pound, which was statistically lower than those of the Normal and SOD1 + HUMSCs groups. In the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, the grip strength of forelimbs and hindlimbs already differed from those of the Normal group at 12 weeks of age. From 16 to 20 weeks, no marked deterioration in grip strength was seen in forelimbs and hindlimbs, despite significantly lower than those of the Normal group. At 20 weeks, the grip strength of forelimbs and hindlimbs was noticeably preserved in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group when compared to the SOD1 group. Collectively, transplantation of HUMSCs alleviated grip strength loss of forelimbs and hindlimbs in SOD1-G93A mice (Fig. 1f and g).

Transplantation of HUMSCs Alleviated Deterioration of Motor Performance on Pen Test in SOD1 Mice

The results of pen test showed that the flat-onward rate was between 20 and 22 cm/s for the three study groups with no statistical differences found. As age increased over time, the flat-onward rate remained stable for the Normal group (Fig. 1h). For the SOD1 group, the flat-onward rate significantly decreased over time. At 12 weeks of age, the flat-onward rate markedly declined when compared to the Normal group; at 20 weeks of age, the rate dropped to 1.67 ± 2.36 cm/s, and even some of the mice in the SOD1 group could not finished the entire test. At 12 weeks of age, the flat-onward rate of the SOD1 + HUMSCs group was lower than that of the Normal group but was comparable to that of the SOD1 group. From 16 to 20 weeks, the flat-onward rate of the SOD1 + HUMSCs group remained steady. Although significantly lower than that of the Normal group, the rate was statistically higher than that of the SOD1 group. Hence, the results showed that HUMSCs transplantation delayed deterioration in motor performance as assessed with pen test (Fig. 1h) (Supplemental Video).

Transplantation of HUMSCs Alleviated Deterioration of Extension Reflex in SOD1 Mice

In the extension reflex test, when a mouse was suspended by grabbing its tail, it was scored as 2 if both its hindlimbs showed normal extension reflex, 1 if only one of the hindlimbs showed extension reflex, and 0 if none of hindlimbs showed extension reflex [26]. In the Normal group, both left and right hindlimbs showed extension reflex from 8 to 20 weeks of age, and a score of 2.00 ± 0.00 was obtained. For the SOD1 group, a marked deterioration in extension reflex was seen at 16 weeks of age; at 20 weeks of age, with almost all mice lost extension reflex, an average of 0.50 ± 0.87 was scored. In the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, it was only until 18 weeks was the deterioration in extension reflex observed in some mice; at 20 weeks, the score for extension reflex maintained at 1.50 ± 0.76, a significant improvement when compared to the SOD1 group (Fig. 1i-j). The results indicated that HUMSCs transplantation delayed deterioration of extension reflex in SOD1-G93A mice.

Transplantation of HUMSCs Improved Travel Distance, Rearing Frequency, and Rearing Time in SOD1 Mice

The movement trajectory of mice in the open-field test were recorded for the three study groups. The movement path was relatively complex in the Normal group, whereas the path was markedly decreased in the SOD1 group. The total travel distance of the SOD1 + HUMSCs group was not statistically different from that of the Normal group but was significantly longer than that of the SOD1 group (Fig. 1k). Following quantification of the rearing frequency and total rearing time over a 15-min period, it was revealed that the rearing frequency and total rearing time was 43.80 ± 15.51 times and 49.40 ± 17.36 s in the Normal group, respectively. However, it was noted that.

SOD1 + HUMSCs group, the rearing frequency and total rearing time were comparable with those of the Normal group but significantly higher than those of the SOD1 group (Figs 1l–m). From the data above, it suggests that HUMSCs transplantation improved total travel distance, rearing frequency, and total rearing time in SOD1-G93A mice.

Transplantation of HUMSCs Ameliorated Spinal Cord Atrophy in SOD1 Mice

At 20 weeks of age, the mice in each study group were sacrificed and the spinal cords were obtained. The gross morphological features revealed that there was a marked atrophy in spinal cord of the SOD1 group (Fig. 2a). It was found that the weight of the spinal cord in the SOD1 and SOD1 + HUMSCs groups significantly decreased in comparison to that of the Normal group (Fig. 2b). Next, the width of spinal cord at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections were measured. There was a noticeable atrophy at these three sections in the SOD1 group, while the atrophy was less apparent at the cervical and thoracic sections in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, the cross-sectional histological slides of spinal cord at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections were stained with cresyl violet to quantify the total area and grey matter area at each section (Fig. 2d). The results revealed that the spinal cord cross-sectional total area and total grey matter area showed marked atrophy at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections in the SOD1 group when compared to those of the Normal group. In the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, although there was a slight decrease in the spinal cord cross-sectional total area and grey matter area, it was not statistically different from those of the Normal group (Fig. 2e and f). Hence, the data indicated transplantation of HUMSCs significantly ameliorated spinal cord atrophy in SOD1-G93A mice.

Fig. 2.

HUMSCs transplantation significantly ameliorated spinal cord atrophy in SOD1 mice. a Images showing the appearance of mice spinal cord at 20 weeks of age. b Quantification of weight for spinal cord. c Width of spinal cord at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections. From the gross appearance of spinal cord, a noticeable atrophy of spinal cord in SOD1 mice was revealed. d Cross-sectional histological slices of spinal cord at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections were subjected to cresyl violet staining. Next, the e total area and f gray matter area of each spinal cord cross-sections were quantified. The results showed a marked atrophy of spinal cord in SOD1 mice. HUMSCs transplantation significantly ameliorated spinal cord atrophy. *, versus the Normal group of the same time point, p < 0.05. #, versus the SOD1 group of the same time point, p < 0.05

Transplantation of HUMSCs Reduced Infiltration of T Cells in SOD1 Mice’s Spinal Cord

An intact BSCB blocks penetration of most medications, proteins, or white blood cells in blood from entering the neuronal tissues and thereby preventing influences caused by these materials. However, when a leakage appears in BSCB or blood permeability increases, immune cells migrate to neuronal tissues and results in subsequent inflammatory reactions. In the spinal cord histological slides obtained from each group at 20 weeks of age, the location of T lymphocytes was labeled with anti-CD3 antibodies to evaluate the intactness of BSCB. The results indicated that T lymphocyte primarily presented in blood vessels or stuck to the inner wall of blood vessels at either cervical, thoracic, or lumbar sections of the spinal cord. In the SOD1 group, a large amount of T lymphocyte had migrated outside of blood vessels and scattered in neuropia of spinal cord. A marked improvement was observed in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group (Fig. 3a). It indicated that HUMSCs transplantation reduced BSCB leakage and migration of T lymphocytes into neuronal tissues in SOD1-G93A mice. Furthermore, 20-week-old mice were intraperitoneally injected with 2% Evans blue. After 3 h, the quantity of Evans blue in spinal cord was measured with OD620. A higher value indicates a higher quantity of dye penetrating from blood vessels into neuropia; that is, the BSCB was damaged to a higher extent. The level of Evans blue in spinal cord was higher in the SOD1 group than those of the Normal and SOD1 + HUMSCs groups. However, the amount of Evans blue in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group still more than that in the Normal group (Fig. 3b). It suggests that HUMSCs transplantation reduced the level of BSCB damage in SOD1-G93A mice.

Fig. 3.

HUMSCs transplantation reduced BSCB leakage and inflammatory responses in SOD1 mice. a Spinal cord histological sections obtained from 20-week-old mice, and T lymphocytes were labeled with anti-CD3 antibody. For each image set of spinal cord sections, the left panels display the images of spinal cord anterior horn at low magnification, and the right panels display the high magnification marked by squares in left panels. It shows that a large amount of T lymphocytes scattered in the neuropia of the spinal cord in the SOD1 group. b Twenty-week-old mice were intra-peritoneally injected with 2% Evans blue dye. The level of Evans blue was analyzed, with a higher value indicating a higher level of leakage from blood vessels to neuropia and hence a higher extent of impairment of BSCB. The results suggested that the level of Evans blue increased significantly in the SOD1 group. Spinal cord histological sections from 20-week-old mice were stained with c anti-Iba1 antibody for microglia labeling and with d anti-GFAP antibody for astroglia labeling. For each image set of spinal cord sections, the left panels display the images of spinal cord anterior horn (indicated with dashed lines) at low magnification, and the right panels display high magnification marked by squares in left panels. Next, the percentage of Iba1- and GFAP-positive area in spinal cord anterior horn were quantified. It revealed that HUMSCs transplantation decreased activation of microglia and astroglia in SOD1 mice (e-f). g A significant increase in NF-kB concentrations in the SOD1 group was observed compared to those of the Normal and SOD1 + HUMSCs groups. *, versus the Normal group of the same time point, p < 0.05. #, versus the SOD1 group of the same time point, p < 0.05

Transplantation of HUMSCs Alleviated Neuro-inflammatory Reactions in SOD1 Mice

Spinal cord histological slices from 20-week-old mice of each study group were subjected to immunohistochemical staining with anti-Iba1 antibody to analyze inflammatory status of anterior horn of spinal cord. From images taken at low and high magnifications, it showed that only a small amount of microglia with low branches in morphology were labeled in cervical, thoracis, and lumbar sections in the Normal group. In the SOD1 group, the number of microglia increased significantly at either cervical, thoracic, or lumbar sections, with a larger size and more complicated branch structure in morphology. The number of microglia locating in spinal cord anterior horn was relatively lower in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group (Fig. 3c). Moreover, the percentage of anti-Iba1-positive area in anterior horn at each spinal cord section was quantified in every study groups. The results indicated that the percentage of area occupied by microglia at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections were higher in the SOD1 group than that of the Normal group. In the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, the percentage area of microglia was higher than that of the Normal group but statistically lower than that in the SOD1 group (Fig. 3e). Thus, it indicated that HUMSCs transplantation lowered microglia activation in SOD1-G93A mice.

Astroglia were labeled with anti-GFAP antibody for analyzing astroglia activation in spinal cord anterior horn. From images taken at low and high magnifications, only a few astroglia were seen at the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections in the Normal group. In the SOD1 group, the number of astroglia markedly elevated at the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections, and their cell size also increased. The number of astroglia located at spinal cord anterior horn was relatively lower in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, the percentage of anti-GFAP-positive area of the anterior horn at each spinal cord section was quantified for all three study groups. The results showed that the percentage area occupied by astroglia was higher in the SOD1 group than those of the Normal group at the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections. On the contrary, the percentage of area occupied by astroglia was statistically lower in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group than those of the SOD1 group at the cervical and thoracic sections but not at the lumbar section (Fig. 3f). Collectively, HUMSCs transplantation reduced astroglia activation in SOD1-G93A mice.

A significant increase in NF-kB concentrations in the SOD1 group was observed compared to that of the Normal group. SOD1 + HUMSCs group had lower level of NF-kB compared with the SOD1 group. There was no statistically significant difference between Normal and SOD1 + HUMSCs groups in terms of NF-kB (Fig. 3g). It is therefore suggested that the anti-inflammatory effects of HUMSC transplantation in the spinal cord are mediated through the suppression of NF-κB pathway activation.

Transplantation of HUMSCs Reduced Neuronal Cell Death in Spinal Cord Grey Matter in SOD1 Mice

Spinal cord histological slices from 20-week-old mice of each study group were labeled with anti-NeuN antibody to mark neuronal cells. The number of neuronal cells locating at anterior horn of each spinal cord section were analyzed through images taken at low and high magnifications (Fig. 4a). The quantitative results showed that the number of neuronal cells was higher within the anterior horn at either cervical, thoracic, or lumbar sections in the Normal group. In the SOD1 group, the number of neuronal cells significantly decreased in the anterior horns of the cervical and lumbar sections. The neuronal cell number in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group was comparable to that of the Normal group and was higher than that in the SOD1 group (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

HUMSCs transplantation reduced loss of neuron in spinal cord gray matter in SOD1 mice. a Spinal cord histological sections from 20-week-old mice were subjected to immunohistochemical staining using anti-NeuN antibody to evaluate the number of neuronal cells in spinal cord anterior horn. For each image set of spinal cord sections, the left panel displays the low-magnification images of spinal cord anterior horn (indicated with dashed lines) at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections, and the right panels display corresponding images at high magnification. Next, the number of NeuN-positive cells in anterior horn was quantified. The results indicated that the number of neuronal cells was preserved at a higher level in mice receiving HUMSCs transplantation (b). Subsequently, changes in the number of neuronal cells of small (0- 40 μm) and large (> 40 μm) diameter in NeuN-positive neuronal cells were analyzed. The results indicated that the number of neuronal cells with large diameter significantly decreased in either c cervical, d thoracic, or e lumbar sections. *, versus the Normal group of the same time point, p < 0.05. #, versus the SOD1 group of the same time point, p < 0.05

Next, the diameter of neuron soma was quantified and the number of neurons with large and small diameters were analyzed to investigate the population of neuronal cell death at anterior horn. Neurons with soma diameter ≤ 40 μm were defined as small-diameter neurons and those with soma diameter > 40 μm were defined as large-diameter neurons. The results showed that there was no significant difference in the number of small-diameter neurons at cervical, thoracic, or lumbar sections between each group. However, there was a significant reduction in the number of large-diameter neurons in the SOD1 group. The number of neuron with a diameter between 40 and 50 μm was statistically higher in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group than that in the SOD1 group (Fig. 4c–e).

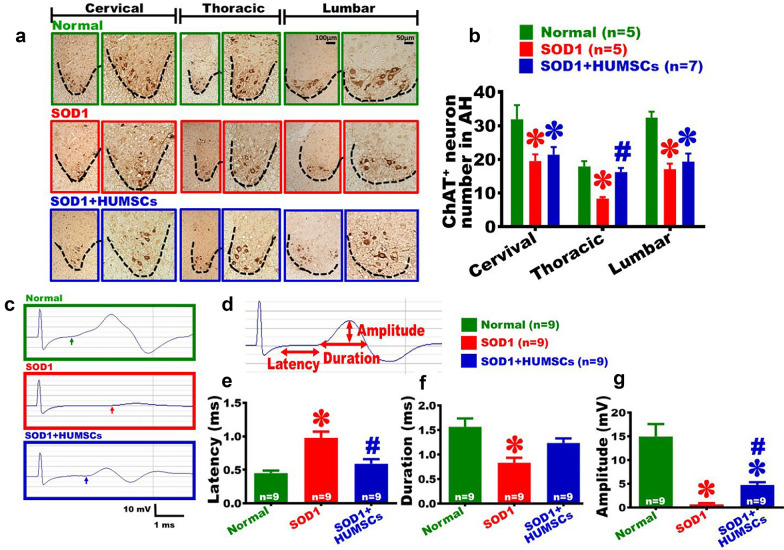

Transplantation of HUMSCs Decreased Loss of Motor Neuron in Spinal Cord Anterior Horn in SOD1 Mice

Spinal cord histological slices from 20-week-old mice of each study group were immunohistochemically stained with anti-ChAT antibody to label cholinergic motor neurons (Fig. 5a). From images taken at low and high magnifications, cholinergic motor neurons had a larger size in morphology at the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar anterior horn of the Normal group. The number of ChAT-positive motor neuron in the anterior horn of the SOD1 group was significantly lower than that of the Normal group. The number of ChAT-positive motor neuron in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group was lower than that of the Normal group at cervical and lumbar sections; however, the number of ChAT-positive motor neurons was preserved at a higher level at the thoracic section (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

HUMSCs transplantation reduced loss of motor neurons in spinal cord gray matter and attenuated degeneration in neuro-muscular electrophysiology. a Spinal cord histological sections from 20-week-old mice were subjected to immunohistochemical staining using anti-ChA for evaluating changes in the number of motor neuron in spinal cord anterior horn. For each image set of spinal cord sections, the left panel displays the low-magnification images of spinal cord anterior horn (indicated with dashed lines) at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sections, and the right panels display corresponding images at high magnification. Next, the number of ChA-positive cells in anterior horn was quantified. The results indicated that the number of motor neuron in the thoracic sections was preserved at a higher level in mice receiving HUMSCs transplantation (b). c A stimulus was given at the mouse’s lumbar vertebra, and changes in action potential of gastrocnemius were recorded for each study group. The arrow indicates the point where the action potential starts to change. Subsequently, latency, duration, and amplitude of action potential were quantified d. The results indicated that the latency increased (e), duration shortened (f), and amplitude decreased (g) in the SOD1 group. Mice transplanted HUMSCs showed changes in gastrocnemius actional potential to a more prominent level. *, versus the Normal group of the same time point, p < 0.05. #, versus the SOD1 group of the same time point, p < 0.05

Transplantation of HUMSCs Alleviated Electrophysiological Degeneration in SOD1 Mice

In order to investigate whether downstream muscles would be influenced by death of spinal cord motor neurons, 20-week-old mice were subjected to muscular electrophysiological tests to examine their neuro-muscular transmission system. Electrical stimuli were given at the fourth lumbar vertebra, and the changes in action potentials of gastrocnemius muscles were recorded and the electromyography for each group was generated. In the Normal group, a marked change in action potential of gastrocnemius muscles was recorded, while only an extremely weak wave was detected in the SOD1 group. For the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, a clear change in action potential was recorded (Fig. 5c). The parameters of action potential recorded at gastrocnemius muscles were further analyzed. The latency is the time from stimulus given at lumbar to the beginning of an action potential recorded at gastrocnemius muscles, which represents the neuron’s signal transmission speed. The duration of action potential stands for the time from the beginning to the end of gastrocnemius muscles contraction once a stimulation is given; it indicates the time of muscle fiber contraction following an impulse. The amplitude of a muscle’s action potential depicts the maximum value of muscle fiber contraction that represents the maximal amount of muscle fiber participating in a given contraction (Fig. 5d). The results showed that the latency was prolonged in the SOD1 group, indicating the speed of signal transmission was slowed down. The SOD1 + HUMSCs group’s latency was not statistically different from that of the Normal group (Fig. 5e). The duration of action potential shortened in the SOD1 group, suggesting that the contraction of muscle fiber was incomplete. The completeness of muscle contraction in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group was not statistically different from that of the Normal group (Fig. 5f). The amplitude of muscle action potential in the SOD1 group was reduced, indicating the number of dominant neurons or the number of muscle fiber that participated in the contraction decreased. The amplitude in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group was significantly smaller than that of the Normal group but statistically higher than that of the SOD1 group, suggesting that HUMSCs transplantation help preservation of neuronal or muscle fiber (Fig. 5g).

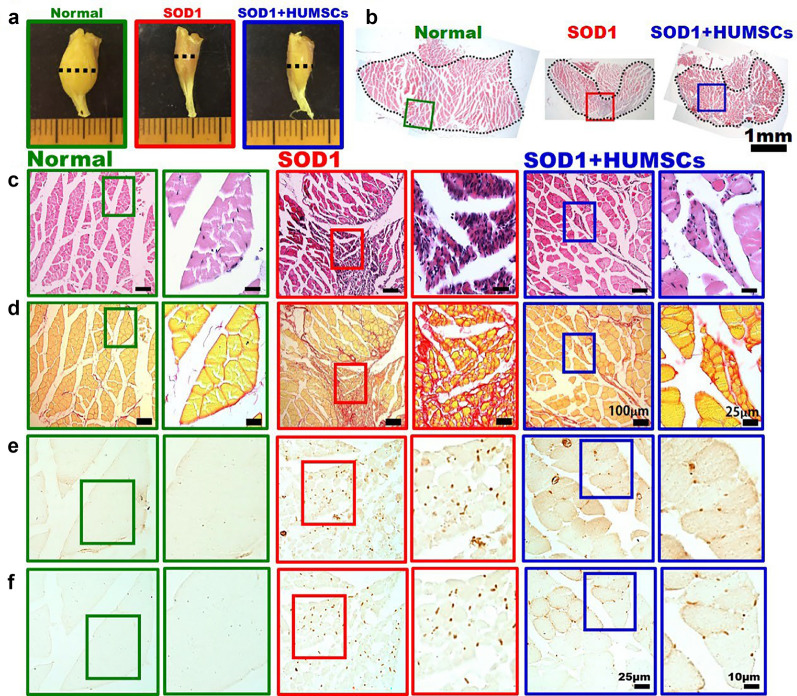

Transplantation of HUMSCs Delayed Deterioration of Gastrocnemius in SOD1 Mice

Calf muscle tissues obtained from 20-week-old mice were examined macroscopically. The appearance of calf muscle in the Normal group was large and thick, whereas marked atrophy of muscle bundle was observed in the SOD1 group. In the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, the atrophy of calf muscle was ameliorated (Fig. 6a). At the point where the calf has the largest diameter (i.e., where gastrocnemius muscle possessing the largest cross-sectional area), cross-sectional slices were subjected to various immunohistochemical stains to understand the pathological changes of the muscle. Through examining the H&E-stained slides at low magnification, it showed that the cross-sectional area of gastrocnemius in the Normal group was the largest. A marked atrophy was seen in the SOD1 group, and the gastrocnemius in the SOD1 + HUMSCs was preserved at a higher extent (Fig. 6b). In the images of H&E-stained histological sections taken at high magnification, the muscle bundle of gastrocnemius was clear and had a larger cross-sectional area in the Normal group. On the contrary, the cross-sectional area of muscle bundle of gastrocnemius was smaller, with multiple regions showing largely aggregated cell nuclei. Aggregated nuclei could be resulted from atrophy of muscle fiber or infiltration of inflammatory cells. In the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, the cross-section of muscle bundle of gastrocnemius was relatively more intact, with aggregated nuclei less seen (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

Transplantation of HUMSCs delayed atrophy of gastrocnemius in SOD1 mice. a Appearance of calf muscles of 20-week-old mice. The results showed that marked atrophy was seen in SOD1 mice. b Dashed line indicated the location where gastrocnemius had the largest diameter and where serial sections of muscle tissues were performed to investigate its pathology. Serial histological sections of calf muscles were subjected to c H&E staining, d Sirius red staining, e immunostaining with anti-αSMA, and f immunostaining with anti-ED1. For images of each group, the left panels display low-magnification images, and the right panels display the corresponding images at high magnification. The results indicated that transplantation of HUMSCs alleviated inflammatory responses, fibrosis, and atrophy in SOD1 mice

Sirius red staining marks fibrotic area in red. The results showed that the cross-sectional area of muscle fasciculus was larger in the Normal group, with only a slight amount of red collagen existing in the connective tissue surrounding the muscle fasciculus. In the SOD1 group, the cross-sectional area of gastrocnemius muscle fasciculus was smaller, accompanied by a large red area that indicated the accumulation of collagen. In the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, the cross-sectional area of muscle fasciculus also decreased, but the red fibrotic region was smaller (Fig. 6d).

Activated fibroblasts in muscle histological sections were labeled with anti-αSMA. Activated fibroblasts synthesize and release collagen and are the main components that cause development of fibrosis. In the Normal group, fibroblasts were rarely detected in gastrocnemius. In the SOD1 group, a large number of fibroblasts were activated in their gastrocnemius. For the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, activated fibroblasts were still seen in the muscle tissue but with a significantly fewer number (Fig. 6e).

Infiltration of macrophage in muscle tissue was labeled with anti-ED1. Almost no macrophage was detected in the muscle tissue of the Normal group. In the SOD1 group, infiltration of a large amount of macrophage was observed in the muscle tissues. For the SOD1 + HUMSCs group, the number of infiltrative macrophages was noticeably decreased (Fig. 6f). Hence, it suggested that HUMSCs transplantation reduced inflammation, fibrosis, and atrophy of gastrocnemius in SOD1-G93A mice.

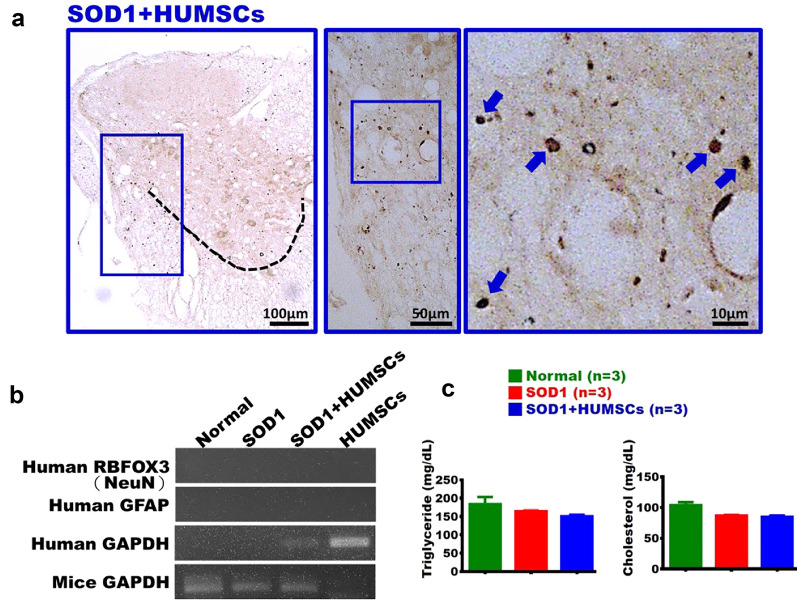

Transplanted HUMSCs Existed in Mice Spinal Cord with no Sign of Differentiation

The nucleus of HUMSC was labeled with anti-human specific nuclei antigen. It showed that HUMSCs survived and distributed in the spinal cord tissue in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group (Fig. 7a). Next, to investigate whether HUMSCs had differentiated into neuronal cells or astroglia, spinal cord tissue of 20-week-old mice in the SOD1 + HUMSCs group was detected with human RBFOX3 (NeuN) and human GFAP primers. Human GAPDH was used as a positive control for HUMSCs. The results indicated that HUMSCs residing in the spinal cord of SOD1 mice did not differentiate into neuronal cells or astroglia (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Undifferentiated HUMSCs in mice spinal cord. a The SOD1 + HUMSCs group was sacrificed at 20 weeks of age and subjected to immunohistochemical staining with anti-human specific nuclei antibody. It was found that HUMSCs survived and scattered in the spinal cord. b In addition, these HUMSCs did not differentiate into neuronal cells or astroglia in SOD1-G93A mice. HUMSCs served as a positive control for human GAPDH. c In the Normal, SOD1, and SOD1 + HUMSCs groups, there were no significant differences in serum levels of triglycerides and cholesterol

Physiological Parameters Unchanged in the Mice After HUMSCs Transplantation

To assess whether HUMSCs transplantation affects energy metabolism, serum lipid biomarkers were measured. No significant differences in triglyceride or cholesterol levels were found among the Normal, SOD1, and SOD1 + HUMSCs groups (Fig. 7c). SOD1 mice showed weight loss, likely due to reduced mobility and feeding. Although HUMSCs improved motor function and reduced spinal inflammation, body weight did not significantly recover. Overall, HUMSCs had no marked effect on systemic lipid or energy metabolism.

Discussion

In this study, HUMSCs were transplanted into the spinal canal of ALS transgenic mice, which was found to reduce inflammatory response, decrease neuronal cell death, alleviate deterioration of motor performance, and effectively prolong life span in SOD1-G93A mice.

Pathology of SOD1-G93A Mice

SOD-G93A transgenic mice have served as a model for ALS for many years. Previous studies have confirmed that motor neuron degeneration and loss of neuro-muscular transmission appear in SOD1-G93A mice. With an onset age of 3 to 4 months, the mice’s hindlimbs start to show tremors and they eventually experience paralysis and death; the time from onset to death ranges about 1 to 2 months [25, 31]. In the present study, a similar pathological development was observed. In the experiments of rotarod, grip strength, and extension reflex, a significant deterioration in behavior was seen in the SOD1 group at 12 weeks of age when compared to the Normal group. As the age increased over time, their mobility continuously worsened. With an average lifespan of 157 days in the SOD1 group, mice were sacrificed at 20 weeks (equivalent to 140 days), so that their spinal cord pathological tissues could be examined before their natural death.

In order to prevent penetration of toxic substances from blood vessels to neuronal tissues, a protective mechanism is developed by the CNS. BSCB is a selective barrier between blood vessels and spinal cord that can block entry and influences of most medications, proteins, and large molecules. A number of studies have found that the SOD1 transgenic mice possess severe BSCB leakages; for this reason, infiltration of a large amount of immunoglobulins is seen in the spinal cord tissue [30, 32]. Our experiments also found similar results, with permeability of blood vessel considerably increased and a large amount of T lymphocytes scattering in the spinal cord tissues.

HUMSCs Transplantation for Treating SOD1-G93A Mice

Due to the limited offspring from mating male SOD1 transgenic mice with wild-type females, all viable progeny was included in the study. Female mice, exhibiting lower body weight and slower behavior than those of males, were used solely for survival analysis to avoid sex-related bias, while males were assigned to behavioral and spinal cord morphological assessments. Behavioral tests involved 10–13 male mice per group, morphological analysis included 7–9 males with fixative perfusion, and 3–4 males with non-fixative perfusion were used for protein and molecular studies. Despite small sample sizes in this study, HUMSC transplantation significantly alleviated SOD1-associated pathology in male mice., with consistent survival benefits observed in female mice. We believe that larger cohorts may further validate these effects. Moreover, our previous studies showed that transplantation of HUMSCs did not induce tumor formation in rats, with monitoring extending up to five months post-transplantation [13–17, 33]. Consistently, no tumors were observed in mice in this study.

Marconi et al. transplanted 2 × 106 mouse adipose mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) into 77-day-old SOD1 transgenic mice via tail vein. From the results of rotarod tests, it was shown that the behavior of transplanted mice was better than that of untreated ones between 85 and 100 days; however, there was no significant difference between the two groups after 100 days. It suggests that the treatment effect of ADMSCs had a limitation in time, with a treatment effect of only 23 days. When the mice were sacrificed at 100 days, it was revealed that neuronal cells were preserved in the spinal cord at a higher extent in mice transplanted with ADMSCs, but there was no reduction in the number of microglia and astrocyte [34]. In our experiment, mice were administered with 2 × 106 HUMSCs at 8 weeks of age (equivalent to 56 days). At 20 weeks of age, mice receiving HUMSCs had significantly elevation in motor performance than those without transplantation. In the spinal cord histological sections of 20-week-old mice, not only neuronal cells but also motor neurons were preserved at a higher level and the number of microglia and astrocyte decreased significantly in mice transplanted with HUMSCs. There might be two reasons that caused the difference in treatment effectiveness: 1) an earlier time point for HUMSCs transplantation (56 days versus 77 days), and 2) a different route for stem cell transplantation (intra-thecal injection versus tail vein injection). It was suspected that the better therapeutic effect may result from a higher number of stem cells in spinal cord achieved by intra-thecal administration.

Garbuzova-Davis et al. administered low (5 × 104), medium (5 × 105), and high (1 × 106) doses of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs) into 13-week-old SOD1 transgenic mice. At 17 weeks of age, extension reflex and grip strength of the high-dose BMMSCs group were lower than those of the Normal group but a noticeable treatment effect was observed when compared to that of the SOD1 transgenic mice. The number of neuronal cells in the spinal cord was higher and activated microglia and astrocyte were significantly reduced in the 17-week-old mice. Furthermore, it was found that transplanted human BMMSCs had differentiated into vascular endothelial cells and CD45+ cells; hence, it was speculated that the treatment effect may arise from repairment of BSCB leakage [26]. Additionally, Uccelli et al. administered 1 × 106 human BMMSCs into 90-day-old SOD1 transgenic mice via tail vein. The results of rotarod tests showed that motor performance was significantly improved up to 40 days following transplantation in mice receiving stem cell treatment than those without such treatment; however, since 40 days after transplantation, there was no difference in motor performance between the two groups. The mice were sacrificed at 125 days, and the histological sections revealed that there was no statistical difference in motor neurons between the treatment and non-treatment groups [35]. In our study, mice received 2 × 106 HUMSCs at 8 weeks of age. At 20 weeks of age, motor performance and grip strength in mice receiving HUMSCs were statistically different from those without receiving HUMSCs. From histological sections of 20-week-old mice, neuronal cells and motor neurons were preserved at a higher level in mice transplanted with HUMSCs. Moreover, there was a significant decrease in the number of microglia and astrocyte. Unlike other studies, transplanted HUMSCs in our study did not differentiate into neuronal cells or astroglia. It was speculated that the therapeutic effect of HUMSCs may attribute to secretion of cytokines. The reason for better therapeutic outcomes could be owing to an earlier timing of HUMSCs administration (56 days in this study versus 77 and 90 days in previous studies) or a higher number of HUMSCs given (2 × 106 vs 1 × 106).

Sironi et al. transplanted 2.5 × 105 HUMSCs into lateral cerebral ventricles of 14-week-old SOD mice. Their results showed that there was no statistical difference in average life span between the SOD mice and those treated with HUMSCs (170 days versus 174 days, respectively). In histological sections of the HUMSCs-transplanted group, the number of microglia significantly reduced while the number of astrocytes increased [36]. In the present study, the average life span was 157 days in SOD1 mice and 174 days in those receiving HUMSCs, with difference being statistically meaningful. In the histological sections, the number of microglia and astrocyte in mice receiving HUMSCs significantly decreased and the BSCB was relatively more intact so that the infiltration of T lymphocyte in spinal cord tissues were less severe. Taken together, the study results show that the number, timing, and route of administration for stem cell transplantation are critical factors determining the treatment effectiveness.

ALS is a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disease marked by widespread motor neuron loss in the cerebral cortex, brainstem, medulla, and spinal cord [1–5]. In this study, intrathecal transplantation of HUMSCs at the ninth thoracic segment significantly reduced spinal inflammation and neuronal death. Our previous studies using direct HUMSCs transplantation into affected brain regions—such as the spinal cord, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum- showed therapeutic benefits in models of spinal cord injury, stroke, epilepsy, and cerebellar atrophy [13–17]. These results suggest that achieving broader neuroprotection in additional brain regions of SOD1 transgenic mice may require the administration of HUMSCs at multiple transplantation sites.

In our previous study, a human antibody-based protein array targeting 85 cytokines was employed to analyze the cytokine profile of HUMSCs-conditioned medium. High levels of CXCL-1, MIF, IL-8, PAI-1, TIMP-1, PTX3, and IGFBP3 were detected, along with lower levels of MMP-9 and thrombospondin-1. These results suggest that HUMSCs secrete growth-associated cytokines that may contribute to their protective and anti-inflammatory effects [33]. In addition, in our study team have investigated therapeutic effects of HUMSCs transplantation in various neuronal diseases. Transplanting HUMSCs to rat spinal cord, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum could improve spinal cord injury [13], stroke [14, 22], epilepsy [16], and spinocerebellar ataxia [17]. Although therapeutic effects were observed in these studies, the underlying mechanisms were different. Interestingly, in the case of stroke, when HUMSCs were transplanted into cerebral cortex, it was found that HUMSCs secreted cytokines such as NAP-2, angiopoientin-2, BDNF, CXCL-16, and PDGF-AA [14]. Additionally, when HUMSCs were transplanted into rats with transected spinal cord, a large amount of human cytokines were found in transected spinal cord, such as NT-3, NAP-2, bFGF, GITR, and VEGF-R3 [13]. In the case that HUMSCs were transplanted into hippocampus of rat with epilepsy, FGF-6, amphiregulin, GITR, MIP-3β, and osteoprotegerin were detected in the hippocampus at a high expression level [16]. By delivering HUMSCs into the cerebellum of mice with type I spinocerebellar ataxia, expression of human cytokines including IL-13, GIF, PAI-1, FGF-2, and CXCL-4 were detected in the cerebellum [17]. Collectively, HUMSCs release different cytokines and small molecules in response to surrounding pathological environment (e.g., different diseases and brain regions) they were transplanted into.

Conclusion

Transplantation of HUMSCs into the spinal canal of SOD1 mice could ameliorate inflammatory responses, reduce neuronal cell death, maintain a better mobility and effectively extend their lifespan. It indicates that HUMSCs transplantation could provide patients with a superior quality of life. In the future, it worth investigating that whether increasing the number of HUMSCs or times of transplantation could treat ALS more effectively.

Supplementary Information

Supplemental Fig. 1. Characterization of Passage 3 and 6 of HUMSCs in vitro. (A) Flow cytometry analyses of surface markers of HUMSCs at Passage 3 and 6 in vitro. The results revealed that HUMSCs in Passage 3 and 6 were positive for CD105, CD90. CD73, and CD44 but negative for CD34 and CD45. (B) To analyze 23 chromosomes of HUMSCs at passage 3rd and 6th in vitro, G-banding staining were used to screen the chromosomal karyotyping. The results demonstrated that HUMSCs at both passage 3rd and 6th exhibited no abnormal changes in chromosomal number or structure. (C) HUMSCs were stained with senescence β-galactosidase staining kit (9860, Cell Signaling Technology). The results revealed faint cytoplasmic signals in Passage 3 and 6 HUMSCs, while H₂O₂-treated HUMSCs showed strong staining in nearly all cytoplasms.

Supplemental Fig. 2. Pedigree of experimental animals

Supplemental Fig. 3. Paraffin embedding, sectioning, and obtaining spinal cord histological slices

Twenty-week-old mice were sacrificed and perfused. Spinal cords were obtained and divided into four regions, including cervical, thoracic upper, thoracic lower, and lumbar sections. The spinal cords were then vertically embedded. (A) Schematic illustration of serial spinal cord histological sections. (B) Spinal cord paraffin blocks were consecutively sectioned at a 5-μm thickness. Ten serial slices numbered 1 to 10 were placed on slides numbered ❶ to ❿, respectively. The following 10 slices were discarded. Slices numbered 21 to 30 and 41 to 50 were placed on slides, with each slide containing 6 slices and the first slide set named #1. The second (#2) and third (#3) sets of slides were prepared sequentially. The first slide of each set (i.e., slide ❶) was subjected to NISSL staining. The second slide (i.e., slide ❷) was subjected to anti-NeuN immunohistochemical staining for labeling nuclei of neurons. The third slide (i.e., slide ❸) was subjected anti-ChAT immunohistochemical staining for labeling motor neurons. The fourth slide (i.e., slide ❹) was subjected to anti-CD3 immunohistochemical staining for labeling T lymphocytes. The fifth slide (i.e., slide ❺) was subjected to anti-GFAP immunohistochemical staining for labeling astroglia. The sixth slide (i.e., slide ❻) was subjected to anti-Iba1 immunohistochemical staining for labeling microglia to observe histopathological status of spinal cord. The rest of the slides were kept as spares. (DOCX 641 KB)

Supplemental Video. The record of the flat-onward balance beam of the mice in the Normal, SOD1, SOD1 + HUMSCs groups at 5 months of age. (MP4 5982 KB)

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Jun-An Chen of Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica in Taipei for his kind gift of all male SOD1-G93A transgenic mice used in this study. All authors declare that they have not use AI-generated work in this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- HUMSCs

Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells

- SOD1

Superoxidase dismutase 1

- CNS

Central nervous system

- BSCB

Blood-spinal cord barrier

- IFN-γ

Interferon-γ

- TNF

αtumor-necrosis factor-α

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- HE staining

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

- ADMSCs

Adipose mesenchymal stem cells

- BMMSCs

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- AH

Anterior horn

Author Contributions

Lin CF and Chen YH performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Yeh CC supported the materials. Lin CF and Fu YS wrote the manuscript. Hsu SPC and Fu YS designed the experiments, reviewed and edited drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by research funds from the grant 113–2314-B-075–061 from National Science and Technology Council in Taiwan and grant V114C-203 from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the Lee Liang-Shong Neurosurgery Foundation in Taipei.

Data Availability

The corresponding author, Fu YS, will make all the data behind the study's conclusions available to the public under reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

The ethics approval for the research project titled “The outcomes and mechanism of xenografting of human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton’ s jelly on mouse amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” was granted by the Medical and Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei. The approval number for this project is 1100306, and the date of approval is March 06, 2021. All animals involved in the study were handled in accordance with ethical guidelines, and their care and use were approved by the Medical and Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University.

The use of human umbilical cord in this study was approved by the research project titled “The outcomes and mechanism of xenografting of human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton’ s jelly on mouse amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” and granted by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The ethics approval number for this project is 2021–01-009BC, and the date of approval is January 07, 2021. All expectant mothers who choose to donate their umbilical cords have provided written informed consent for the use of umbilical cords in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sanford P. C. Hsu, Email: doc3379b@gmail.com

Yu-Show Fu, Email: ysfu@nycu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Johnson JO, Mandrioli J, Benatar M, Abramzon Y, Van Deerlin VM, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Exome sequencing reveals VCP mutations as a cause of familial ALS. Neuron. 2010;68(5):857–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardiman O, Van Den Berg LH, Kiernan MC. Clinical diagnosis and management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(11):639–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman EL, Goutman SA, Petri S, Mazzini L, Savelieff MG, Shaw PJ, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2022;400(10360):1363–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott CJ, Shaw PJ. Diagnosis and management of motor neurone disease. BMJ. 2008;336(7645):658–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, Turner MR, Eisen A, Hardiman O, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):942–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mejzini R, Flynn LL, Pitout IL, Fletcher S, Wilton SD, Akkari PA. ALS genetics, mechanisms, and therapeutics: where are we now? Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutedja NA, Fischer K, Veldink JH, van der Heijden GJ, Kromhout H, Heederik D, et al. What we truly know about occupation as a risk factor for ALS: a critical and systematic review. Amyotrophic Lateral Scler. 2009;10(5–6):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362(6415):59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu D, Wen J, Liu J, Li L. The roles of free radicals in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: reactive oxygen species and elevated oxidation of protein, DNA, and membrane phospholipids. The FASEB J. 1999;13(15):2318–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garbuzova-Davis S, Haller E, Saporta S, Kolomey I, Nicosia SV, Sanberg PR. Ultrastructure of blood–brain barrier and blood–spinal cord barrier in SOD1 mice modeling ALS. Brain Res. 2007;1157:126–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bezzi P, Domercq M, Brambilla L, Galli R, Schols D, De Clercq E, et al. CXCR4-activated astrocyte glutamate release via TNFα: amplification by microglia triggers neurotoxicity. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(7):702–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Pietro L, Baranzini M, Berardinelli MG, Lattanzi W, Monforte M, Tasca G, et al. Potential therapeutic targets for ALS: MIR206, MIR208b and MIR499 are modulated during disease progression in the skeletal muscle of patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang C-C, Shih Y-H, Ko M-H, Hsu S-Y, Cheng H, Fu Y-S. Transplantation of human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton’s jelly after complete transection of the rat spinal cord. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(10):e3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Y-C, Ko T-L, Shih Y-H, Lin M-YA, Fu T-W, Hsiao H-S, et al. Human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells promote recovery after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(7):2045–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu Y-S, Yeh C-C, Chu P-M, Chang W-H, Lin M-YA, Lin Y-Y. Xenograft of human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells promotes recovery from chronic ischemic stroke in rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(6):3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang P-Y, Shih Y-H, Tseng Y-j, Ko T-L, Fu Y-S, Lin Y-Y. Xenograft of human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton’s jelly as a potential therapy for rat pilocarpine-induced epilepsy. Brain, Behav Immun. 2016;54:45–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai P-J, Yeh C-C, Huang W-J, Min M-Y, Huang T-H, Ko T-L, et al. Xenografting of human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton’s jelly ameliorates mouse spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Transl Neurodegener. 2019;8:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chao KC, Chao KF, Fu YS, Liu SH. Islet-like clusters derived from mesenchymal stem cells in Wharton’s Jelly of the human umbilical cord for transplantation to control type 1 diabetes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(1):e1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai PC, Fu TW, Chen YMA, Ko TL, Chen TH, Shih YH, et al. The therapeutic potential of human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton’s jelly in the treatment of rat liver fibrosis. Liver Transpl. 2009;15(5):484–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu K-A, Wang S-Y, Yeh C-C, Fu T-W, Fu Y-Y, Ko T-L, et al. Reversal of bleomycin-induced rat pulmonary fibrosis by a xenograft of human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton’s jelly. Theranostics. 2019;9(22):6646–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu K-A, Yeh C-C, Kuo F-H, Lin W-R, Hsu C-W, Chen T-H, et al. Comparison of reversal of rat pulmonary fibrosis of nintedanib, pirfenidone, and human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton’s jelly. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu K-A, Yeh C-C, Hsu C-H, Hsu C-W, Kuo F-H, Tsai P-J, et al. Reversal of pulmonary fibrosis: human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton’s Jelly versus human-adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):6948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulus M, Sibiak R, Stefańska K, Zdun M, Wieczorkiewicz M, Piotrowska-Kempisty H, et al. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells derived from human and animal perinatal tissues-origins, characteristics, signaling pathways, and clinical trials. Cells. 2021;10(12):3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galderisi U, Peluso G, Di Bernardo G. Clinical trials based on mesenchymal stromal cells are exponentially increasing: where are we in recent years? Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2022;18(1):23–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264(5166):1772–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garbuzova-Davis S, Kurien C, Thomson A, Falco D, Ahmad S, Staffetti J, et al. Endothelial and astrocytic support by human bone marrow stem cell grafts into symptomatic ALS mice towards blood-spinal cord barrier repair. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferris N, Reid S, Hutchings G, Kitching P, Danks C, Barker I, et al. Pen-side test for investigating FMD. Vet Rec. 2001;148(26):823–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boy J, Schmidt T, Schumann U, Grasshoff U, Unser S, Holzmann C, et al. A transgenic mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 resembling late disease onset and gender-specific instability of CAG repeats. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37(2):284–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]