Abstract

Background

Tissue-resident mesenchymal stem cells, also known as mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), play a crucial role in maintaining tissue homeostasis and repair. However, their function in chronic inflammatory diseases, such as asthma, remains elusive.

Aim

Here, we aimed to assess the influence of house dust mite (HDM)-induced asthmatic inflammation on the numbers and function of lung resident (lr)MSCs.

Methods

Experimental asthma was induced in female C57BL6/cmdb mice via intranasal HDM administration. LrMSCs were isolated, expanded, and characterized by flow cytometry and differentiation assays. Human adipose tissue-derived (hAD)MSCs were isolated and stimulated with HDM, LPS, or cytokines. Co-culture experiments with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) assessed immunomodulatory potential. Gene expression, cytokine levels, and T-cell proliferation were analyzed.

Results

Here, we showed that asthmatic lung inflammation significantly reduces the number of lrMSCs. More importantly, remaining lrMSCs showed impaired differentiation potential and lacked immunomodulatory functions. Furthermore, we found that exposure of hAD-MSCs to HDM and LPS similarly led to marked inhibition of differentiation potential and suppression of immunosuppressive activities. Notably, this inhibitory effect persisted despite the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines released by PBMCs in response to LPS and HDM. Furthermore, we showed that inflammatory signaling alone, in the absence of direct LPS and HDM exposure, significantly reduces growth factor-induced adipogenesis and osteogenesis.

Conclusions

Taken together, our findings indicate that asthmatic inflammation not only reduces the number of lrMSCs but also impairs their function, potentially exacerbating disease progression by limiting their immunoregulatory role.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13287-025-04520-1.

Keywords: MSC, Asthmatic lung inflammation, MSC phenotype, Immunomodulation, Lung resident MSC, Mesenchymal stem cells, MSC differentiation

Introduction

Asthma, with over 300 million cases worldwide, represents one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases [1, 2]. Despite significant progress in understanding asthmatic inflammation, the etiology of asthma development remains elusive. Several asthma inflammatory phenotypes have been identified and characterized in experimental models, namely eosinophilic (Th2-mediated inflammation), mixed granulocytic (mixed Th2, Th1/Th17-mediated inflammation), and neutrophilic (non-Th2-mediated inflammation), which have enhanced our understanding of the complex nature of the disease [3]. Although a causative treatment is unavailable, Th2-mediated asthmatic inflammation can be well established with inhaled or systemic corticosteroids and novel biological therapies [4]. However, an increased neutrophil count, observed in approximately 50% of patients, strongly correlates with disease severity [5]. Unfortunately, 5–10% of all asthma cases remain poorly controlled [6]. Therefore, there is a substantial need to improve understanding of the complexity of the lower airways’ non-Th2 or Th2-low inflammatory microenvironment, which may aid in advancing innovative therapeutic strategies, including cellular and biological therapies.

Mesenchymal stromal cells, also known as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), represent a group of adult stem cells initially identified by Friedenstein et al. in the bone marrow [7, 8]. Due to their capacity for differentiation into mesodermal lineage cells [9–12], low or lack of immunogenicity (low or absent expression of major histocompatibility complex molecules) [13], and potent anti-inflammatory properties [14, 15], MSCs are recognized as promising candidates for the treatment of degenerative and inflammatory diseases, including chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma [16, 17].

MSCs have been isolated from nearly every tissue and organ, including the lungs [18]. Lung-resident (lr)MSCs are localized to the perivascular niche, particularly along the smallest blood vessels or capillaries, in the alveolar interstitial space close to type I alveolar epithelial cells [19]. The airway epithelial barrier is the first line of defense against inhaled irritants, such as allergens, pollutants, and microbes [20–23]. Given their subepithelial and perivascular localization, lrMSCs are presumed to play a crucial role in regulating pulmonary homeostasis, defined as the balance between destructive inflammatory mechanisms and repair/regeneration processes. Steady-state MSCs produce low levels of inflammatory mediators and are considered hypoimmunogenic. However, upon stimulation by inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β, IFNγ, and TNF, their immunomodulatory functions are activated [24–26]. Despite their potent immunosuppressive properties and proximity to the epithelial barrier, it remains unclear why these cells fail to effectively mitigate asthmatic inflammation. To address this question, we investigated the impact of asthmatic inflammation induced by house dust mite (HDM) extract on the number of lrMSCs. Furthermore, we assessed how such stimulation influences the functional properties of these cells.

Materials and methods

Experimental asthma model

The C57BL6/cmdb female mice (Experimental Medicine Centre, Medical University in Bialystok) were kept under pathogen-free conditions following Good Laboratory Practice standards. The mice were housed on a 12-h light/dark cycle with controlled temperature and humidity. The study was reviewed and approved by the Local Ethical Committee in Olsztyn, Poland (number 35/2019). The experimental asthma model was established as previously reported [27]. Briefly, female C57BL6/cmdb mice, aged 8–10 weeks, 5 animals per group (10 animals in total allocated randomly in the groups by research group members), were subjected to intranasal administration of 20 µl of HDM extract (Citeq) or saline (control group) for 3 weeks, with a 2-day break after every 5 days of exposure (Fig. 1A). Each administration delivered a dose of 100 µg of HDM, calculated based on total protein content (for detailed characteristics of the used HDM, please see online Supplementary Table S1). On day 22 of the experiment, the animals were sacrificed using overdosed isoflurane (Ramanweil) inhalation, followed by cervical dislocation. Subsequently, biospecimen collection, analysis, and biobanking were performed (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

The number of lrMSCs is decreased in asthmatic mice. A Schematic representation of the inflammatory phenotype induction in female C57BL6/cmdb mice via intranasal administration of house dust mite (HDM) extract (100 µg of protein) over three weeks. The exposure protocol included a cyclic pattern of five consecutive days of stimulation (black) followed by a two-day break (blue). The control group (Veh) received 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl) as a vehicle. Mice were euthanized 72 h after the final HDM exposure (green), and lung tissue was collected for analysis: the upper left lobes were processed for histological staining, while the right lobes were used for flow cytometry. B Representative lung tissue Sects. (3 µm) demonstrate increased inflammatory cell infiltration, as visualized by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, and enhanced mucus production, as indicated by periodic acid-schiff (PAS) staining, in HDM-exposed mice compared to controls. C Gating strategy for lung-resident mesenchymal stromal cells (lrMSCs), identified within the CD45⁻ MHC⁻ population as CD29⁺ and Sca-1⁺ cells. D Summary of quantitative analysis of lrMSCs numbers in HDM-exposed mice compared to controls. E Summary of quantitative analysis of bone marrow (BM)-MSCs numbers in HDM-exposed mice compared to controls. Statistical significance was determined using the Wilcoxon test (*p < 0.05; n = 5)

Histochemical stainings

The lungs were initially fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by paraffin embedding. Next, 3 µm-thick microtome sections were prepared and mounted on glass slides. Hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) staining served to evaluate inflammatory cell infiltration within the lungs, while periodic acid-schiff (PAS, Roche) staining was employed to assess mucus production, following standard protocols. The stained slides were visualized using a Panoramic 250 Flash III DX (3DHISTECH) and SlideViewer 2.8 software (3DHISTECH).

Isolation of lung resident Mesenchymal Stromal Cells

lrMSCs were isolated from the right lung lobes, which were initially washed with PBS (Corning), then cut into 2–4 mm pieces, and incubated for 45 min at 37 °C in 0.1% collagenase IV (1 mg/ml, Gibco). The resulting cell suspension was filtered through 100 µm cell strainers (Biologix) and then centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min. The lrMSCs were subsequently cultured in media from the MesenCult Expansion Kit (StemCell) supplemented with gentamicin (15 µg/ml, Gibco) until the second passage. Thereafter, lrMSCs were phenotypically and functionally analyzed according to the criteria set by the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) [29]. The cells exhibited adherence to plastic, expressed CD29 and Sca-1, lacked CD31, CD34, CD45, and MHC class II, and demonstrated the ability to differentiate into adipocytes and osteoblasts. Cell viability and density were evaluated by independent observers using trypan blue (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the Bürker chamber, ensuring the preparation was of high quality for experimental use. The cells were used for functional T cell suppression assay.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell isolation

The isolated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a buffy coat were obtained from the Regional Blood Donation Centre, Bialystok. The collection of buffy coats was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Bialystok (number R-I-002/634/2018, approved 28 February 2019). Study participants provided written informed consent, and the study was conducted under the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. PBMCs isolation was performed using a density gradient centrifugation (Pancoll, PANBiotech) at 1200 g for 25 min. After 8–10 washing steps with MACS buffer (PBS supplemented with ethylenediaminetetraacetic, Invitrogen), remaining red blood cells were lysed by incubating the samples for 10 min with freshly prepared 1 × lysing solution (Pharm Lyse Lysing Buffer with cell culture grade water 1:10, BD Biosciences), followed by washing with PBS without calcium and magnesium ions (Corning). Cell viability and cell count were assessed using trypan blue (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the Bürker chamber.

Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cell isolation

Adipose tissue was obtained from donors qualified for abdominoplasty surgery and admitted to the 1 st Clinical Department of General and Endocrinology Surgery, Medical University of Bialystok Clinical Hospital. Adipose tissue fragments obtained from resected skin folds were collected following approval from the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Bialystok (APK.002.114.2021). Study participants provided written informed consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration. Human adipose tissue-derived (hAD)-MSCs were isolated as previously described [28]. Briefly, tissue digestion with collagenase IV (1 mg/ml, Gibco) was followed by cell isolation, culture in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Basal Medium (ATCC) supplemented with 15 μg/ml gentamicin (Gibco), and expansion up to the second passage. Then, hAD-MSCs were identified following the criteria of the ISCT [29]. MSCs exhibited adherence to plastic, expressed CD73, CD90, and CD105, lacked CD45 and HLA-DR, and demonstrated differentiation potential into adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes. Cell viability and density were verified by independent observers using trypan blue (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the Bürker chamber, ensuring high-quality preparation for experimental usage.

PBMCs stimulation

Freshly isolated PBMCs were directly seeded on 24-well plates (NEST) (1mln cells/ml) and incubated for 24 h in 5% CO2 at 37 °C in R10 medium (RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum, PAN Biotech) either with 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl) or in the presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (0.25, 0.5, and 1 µg/ml, InvivoGen) or HDM (3.55, 7.1, 14.2 µg/ml, Citeq). Next, the cell stimulation medium was collected and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min to remove any remaining cells and used for MSC stimulation.

hAD-MSCs stimulation

The optimized medium was specifically designed to stimulate hAD-MSCs, which were cultured in 24-well plates (NEST) in 5% CO2 at 37 °C with MSC basal medium (ATCC) at the 3rd passage upon reaching 70–80% confluence. At that point, hAD-MSCs were washed twice with PBS (Corning) and then exposed to a 1:1 mixture of MSC-specific medium and PBMC-conditioned medium, which was prepared immediately before use.

Simultaneously, hAD-MSCs were directly stimulated for 24-120 h with the same stimulants (LPS or HDM), following the same procedure previously applied to PBMCs, including control (NaCl). Moreover, hAD-MSCs cultured under the same conditions as described above were exposed directly to cytokines: IL-1β (25 ng/ml, R&D Systems), IFNγ (50 ng/ml, R&D Systems), TNF (25 ng/ml, R&D Systems), or a mix for 24 h. Stimulation with only NaCl served as a control (Veh).

MSCs differentiation analysis

Following isolation, lrMSCs were differentiated into two mesodermal lineages: adipocytes and osteoblasts, using the Mouse Mesenchymal Stem Cell Functional Identification Kit (R&D Systems). Differentiation was evaluated using the kit-provided lineage-specific primary antibodies, namely goat anti-mouse fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) for adipocytes (assessed after 14 days of differentiation), and goat anti-mouse Osteopontin for osteoblasts (assessed after 21 days of differentiation) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Appropriate secondary antibodies were used for the detection of FABP4 and Osteopontin (donkey anti-goat IgG, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The hAD-MSCs were differentiated after 24 h preincubation with LPS (1 μg/ml), HDM (14.2 μg/ml), IL-1β (25 ng/ml), IFNγ (50 ng/ml), TNF (25 ng/ml), or a mix of cytokines according to the protocol provided with the Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Functional Identification Kit (R&D Systems). As a control, hAD-MSCs were stimulated with NaCl only. Differentiation was analyzed using the kit-provided lineage-specific primary antibodies, namely goat anti-mouse FABP4 for adipocytes (assessed after 14 days of differentiation), goat anti-human Osteocalcin for osteoblasts (assessed after 21 days of differentiation), and goat anti-human Aggrecan for chondrocytes (assessed after 21 days of differentiation) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Appropriate secondary antibodies were used for the detection of FABP4, Aggrecan (donkey anti-goat IgG, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and Osteocalcin (goat anti-mouse IgG1, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Finally, the slides were mounted in Prolong Gold with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to stain the nuclei and analyzed using a Leica Stellaris 5 confocal microscope.

For quantitative image analysis, FABP4-positive adipocytes and Osteopontin- or Osteocalcin-positive osteoblasts were manually counted by visually identifying them using ImageJ software (NIH). Chondrogenic differentiation was quantified by measuring Aggrecan expression mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) using ImageJ (NIH) with fluorescence values normalized to background levels.

Flow cytometry

The total lung cells were isolated from the right lobes according to the protocol provided with the lung dissociation kit (Miltenyi Biotec), resuspended with MACS buffer, and passed through a 70 μm cell strainer (Miltenyi Biotec) to obtain a single-cell suspension. Cells were then stained with Armenian hamster anti-mouse CD29 (APC-Cy7, clone HMβ1-1, BioLegend), rat anti-mouse CD31 (FITC, clone 390, BioLegend), rat anti-mouse CD34 (APC, clone MEC14.7, BioLegend), rat anti-mouse CD45 (PerCP, clone 30-F11, BioLegend), rat anti-mouse Sca-1 (Alexa Fluor 700, clone D7, BioLegend), rat anti-mouse MHC class II (PE, clone M5/114.15.2, BioLegened) for 45 min at room temperature. After two washes in MACS buffer, cells were fixed in 1% PFA and analyzed within 24 h using a Canto II flow cytometer.

The AD-MSCs after 24-120 h exposed to used stimulants were stained with mouse anti-human: CD34 (Alexa Fluor 700, clone 581, BioLegend), CD45 (BB700, clone HI30, BD Biosciences), CD73 (FITC, clone AD2, BD Biosciences), CD90 (PE, clone 5E10, BD Biosciences), CD105 (APC, clone 43A3, BioLegend), and HLA-DR (PE-Cy7, clone L243, BioLegend) to confirm the phenotype.

PBMCs and hAD-MSCs were stained with Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit with Propidium Iodide (PI) (FITC, Invitrogen) to assess viability. Cells were washed twice with MACS buffer and resuspended in Annexin V Binding Buffer (Invitrogen). A 100 μl aliquot of the cell suspension was transferred to a new cytometry tube, followed by the addition of 5 μl of Annexin V and 10 μl of PI solution. After 15 min of incubation, 400 μl of Annexin V Binding Buffer was added to each tube, and the samples were immediately analyzed using the Symphony A1 cytometer and FlowJo 10.7.2. software (BD Biosciences).

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Thermo Fisher Scientific), a fluorescent dye, was used to track PBMC proliferation. A 5 mM stock solution of CFSE, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, was diluted in pre-warmed R10 media to acquire a 5 μM working solution. Then, cells with CFSE were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min in the dark. Next, PBMCs were centrifuged at 400 g for 7 min. The prepared cells were subsequently stimulated with Dynabeads mouse/human T-activator CD3/CD28 (Gibco) according to the protocol and analyzed after 96 h incubation in co-culture with lrMSC or hAD-MSCs, using murine or human PBMCs, respectively.

RNA isolation, qPCR, and mRNA transcript analysis

Total RNA was extracted from PBMCs using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and from AD-MSCs after LPS or HDM stimulation using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) to evaluate the expression of selected genes designed by Primer-BLAST and synthesized by HPLC method (Genomed) (ACTB, 5’-ACAGAGCCTCGCCTTTGCC-3’, 5’-GATATCATCATCCATGGTGAGCTGG-3’; GAPDH, 5’-GGATTTGGTCGTATTGGGCG-3’, 5’- TCCCGTTCTCAGCCATGTAGT-3’; IL-6, 5’- CCACCGGGAACGAAAGAGAA-3’, 5’- TCTCCTGGGGGTATTGTGGA-3’). The quantity and purity of collected RNA were measured by a Nanodrop Microvolume Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reverse transcription was conducted using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mix master for qPCR contained 5 µl SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad), 2.5 μM of each primer, and 5 ng of cDNA. The parameters of the cycler were set as described: 10 min, 95 °C for hold; 40 cycles of PCR for 15 s, 95 °C, and 60 s, 60 °C; and melt curve for 15 s, 95 °C, and 60 s, 60 °C (StepOnePlus, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were normalized to the housekeeping genes, and the values were expressed as relative mRNA levels of specific gene expression as calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Additionally, total RNA was isolated from cytokine-stimulated hAD-MSCs as above. A total of 1 μg of RNA with a RIN > 8 was used for cDNA library preparation following the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA protocol (Illumina), and its quality was verified using the Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer. Next-generation sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform, generating 150 bp paired-end reads (2 × 75 bp). Sequencing quality was evaluated by FastQC version 0.11.5. Quality-filtered reads were mapped to the Human GRCh38 reference genome using the STAR aligner version 2.5.3a. Transcript per million (TPM) expression levels were acquired by running Salmon (v.1.10.1). The Index for running Salmon has been generated based on an ENSEMBL release 112, with the entire genome of the organism as the decoy sequence. This has been performed followin the Salmon manual by concatenating the genome to the end of the transcriptome and populating the decoys.txt file with the chromosome names.

ELISA

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the level of cytokines and growth factors, namely IL-6 and IL-10, was determined in cell culture supernatants through ELISA duo sets (R&D Systems). The plates were read using Varioscan Lux (Thermo Fisher Scientific) set to 450 nm, and the results were calculated relative to generated standard curves. The standard range for IL-6 was 9.38-600 pg/ml, and for IL-10 was 31.2-2000 pg/ml.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 9. The Wilcoxon test was employed to evaluate statistical significance, with a threshold of p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Asthmatic lung inflammation reduces the number of lrMSCs

Asthmatic lung inflammation is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by complex immune responses creating a heterogeneous inflammatory milieu. For this study, we used an experimental T2-low HDM-induced asthmatic lung inflammation model (Fig. 1A) [30]. We characterized increased inflammatory cell infiltration and mucus overproduction (Fig. 1B). Moreover, we assessed the inflammatory cytokine profiles to validate Th1/Th17-related cytokines characteristic for Th2-low inflammation (data not shown). Next, we isolated total lung cells and performed flow cytometry characterization of lrMSCs using a standard gating strategy (Fig. 1C). We found a significantly lower number of lrMSCs in inflamed lungs compared to non-inflamed counterparts (Fig. 1D). Next, we wished to analyze whether the observed decrease in lrMSCs numbers may be related to the depletion of their reservoir in the bone marrow and, consequently, reduced migration into the lungs. However, we found no differences in bone marrow (BM)-MSCs among the analyzed groups (Fig. 1E, Supplementary Fig. 1).

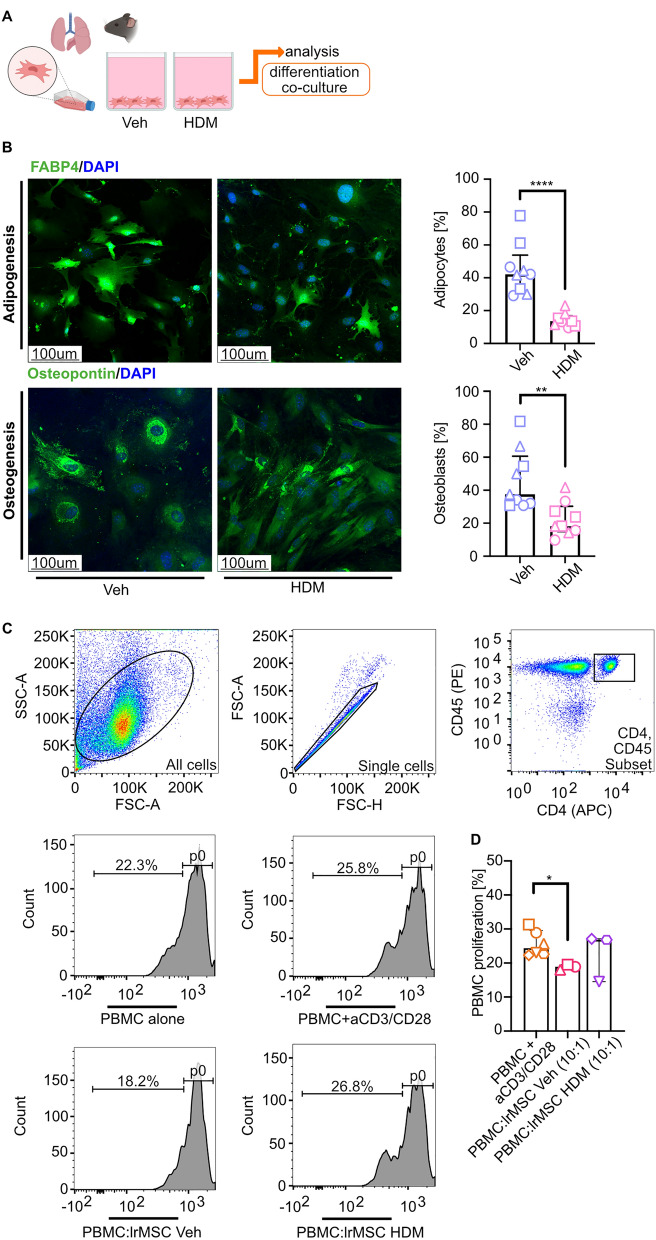

MSCs isolated from asthmatic lungs show reduced differentiation potential and a lack of immunosuppressive activities

Having found reduced numbers of lrMSCs, we aimed to evaluate their functional properties, namely differentiation potential and immunosuppressive activities (Fig. 2A). First, we differentiated lrMSCs into adipocytes and osteoblasts, and observed a significantly reduced ability for differentiation of lrMSCs isolated and expanded from inflamed lungs (Fig. 2B) compared to control counterparts. Next, we used an in vitro CFSE-based CD3/CD28 antibody mix-activated T cell proliferation assay to assess the lrMSCs’ immune modulatory properties (Fig. 2C). Surprisingly, only lrMSCs isolated and expanded from noninflamed lungs showed a significant reduction in T cell proliferation after 4 days of co-culture (Fig. 2D). Our findings suggest that asthmatic lrMSCs exhibit impaired immunosuppressive capacity.

Fig. 2 .

Impaired differentiation and immunosuppressive capacity of lrMSCs isolated from asthmatic lungs A Schematic representation experimental design. Lung resident mesenchymal stromal cells (lrMSCs) were isolated from mice, and functional properties were assessed. B Representative confocal stainings of lrMSCs differentiation. Differentiation potential was assessed by inducing adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation, followed by immunofluorescence staining for adipocyte marker, fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4, green) and osteoblast marker, Osteopontin (green). Nuclei were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The percentage of FABP4 + and Osteopontin + cells was calculated as the proportion of marker-positive cells relative to the total cell count. A summary of analyses is presented on the left side. Statistical significance was determined using the Wilcoxon test (**p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001; n = 3, each with 3 technical replicates). C Representative gating strategy for T-cell analysis in a T-cell proliferation assay. D Summary of analysis of the immunoregulatory potential of lrMSCs in T-cell proliferation assay. Statistical significance was determined using the Wilcoxon test (*p < 0.05; n = 3)

LPS and HDM stimulation reduce MSCs’ differentiation potential and anti-inflammatory properties

As mentioned in the introduction, steady-state MSCs are distinguished by their hypoimmunogenic nature and high differentiation potential. However, the reduced differentiation capacity and impaired anti-inflammatory properties observed in lrMSCs isolated from asthmatic lungs prompted us to investigate whether these alterations could result from direct exposure to HDM. In particular, HDM is a complex mixture containing various mite-derived proteins (including allergens and proteases) and endotoxin (LPS). Therefore, to more precisely evaluate the impact of HDM and endotoxin on the functional properties of MSCs, we additionally used LPS at concentrations equivalent to those present in HDM. To assess the influence of LPS and HDM exposure on MSCs’ function in human settings, we used hAD-MSCs (Fig. 3A).

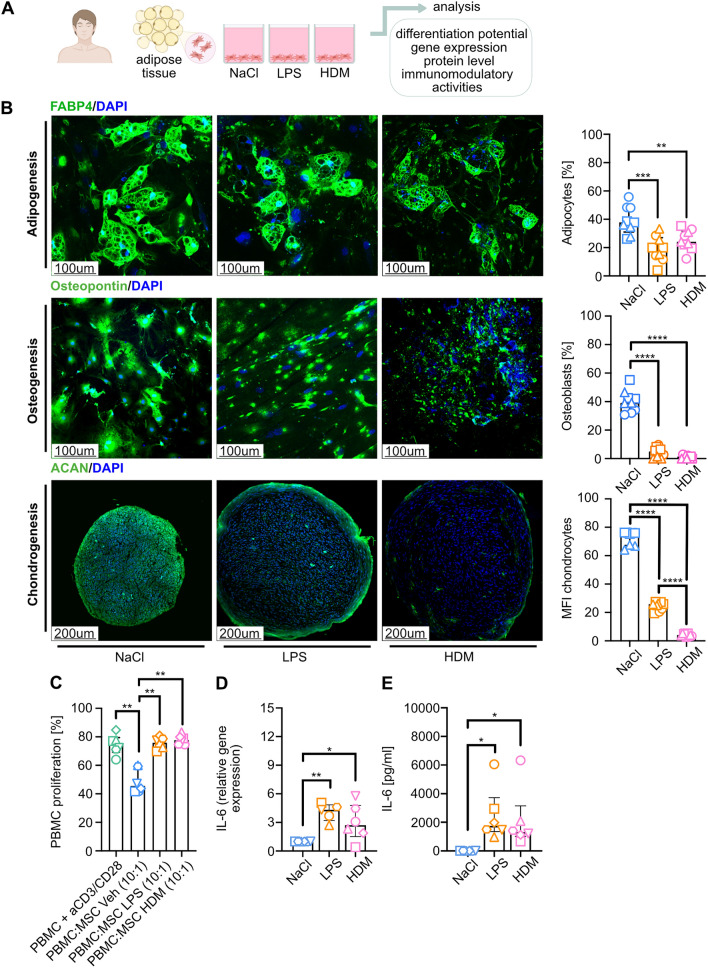

Fig. 3.

HDM and LPS stimulation of hAD-MSCs impairs their functional properties. A Schematic representation of the experimental design of an in-vitro model of direct 24 h hAD-MSCs stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 1 μg/ml), house dust mite (HDM, 14.2 μg/ml) or 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl) as a control. B Representative confocal pictures at the end of adipogenesis (fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) +, green; after 14 days of differentiation), osteogenesis (Osteocalcin +, green; after 21 days), and chondrogenesis (Aggrecan +, green; after 21 days). And 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used for nuclear stainings. The percentage of positive cells (adipocytes, osteoblasts) was determined by dividing the number of positive cells by the total cell count. The percentage of positive chondrocytes was evaluated using the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) method. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ software. Wilcoxon test (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; n = 3, each with 3 technical replicates). C Summary of analysis of the effect of hAD-MSCs exposure to HDM, LPS, and NaCl on T-cell proliferation. Wilcoxon test (**p < 0.01; n = 3). Summary of D IL-6 relative gene expression, expressed as 2−ΔΔ.CT and E IL-6 levels in cell culture supernatant upon LPS, HDM, or NaCl stimulation. Wilcoxon test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; n = 6)

First, we performed a differentiation assay of LPS- and HDM-primed cells. We found that both stimulations significantly reduce the differentiation capacity of MSCs (Fig. 3B). Next, we wished to assess whether LPS and HDM stimulation influence the immunosuppressor functions of MSCs. Again, both stimulations abolished the immunosuppressive activities of the analyzed cells (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Fig. 2). Moreover, we observed that primed MSCs showed significantly higher expression of proinflammatory IL-6 at the gene expression and protein level (Fig. 3D, E, respectively).

Conditioned media from LPS- and HDM-stimulated PBMCs modulate MSCs’ cytokine profile, inducing IL-6 but not IL-10 production

Having found that LPS and HDM signaling alter the functional properties of MSCs, we next aimed to investigate whether inflammatory mediators produced by LPS- and HDM-stimulated PBMCs affect MSCs’ viability and cytokine expression. Specifically, we sought to determine whether exposure to conditioned medium from stimulated PBMCs induces changes in MSC survival and cytokine secretion profile (Fig. 4A). First, we assessed the influence of LPS and HDM stimulation on PBMCs and found that both stimulators do not reduce their viability (Fig. 4B, C).

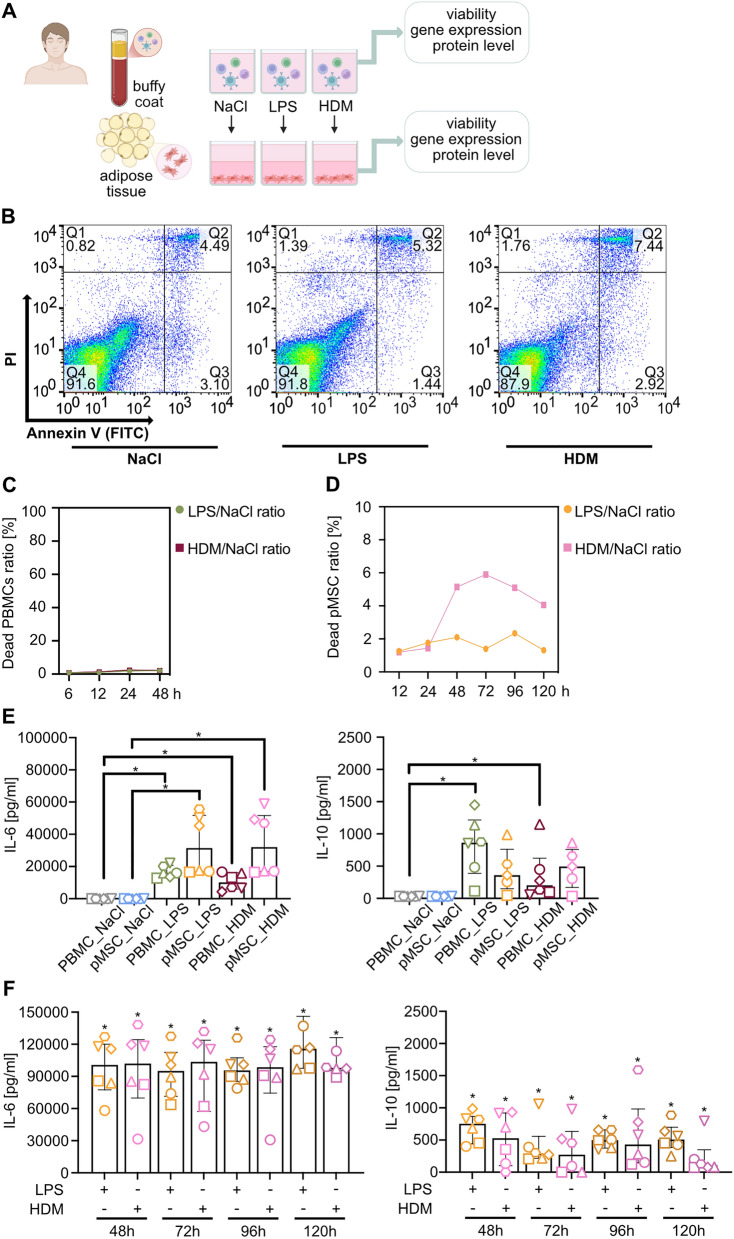

Fig. 4.

Exposure of hAD-MSCs to conditioned media from HDM or LPS stimulation does not induce IL-10 expression. A Schematic representation of the experimental design. Experimental procedure for human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (hAD-MSCs) priming. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from human buffy coat were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 1 μg/ml) or house dust mite (HDM, 14.2 μg/ml) for 24 h or up to 120 h. Next, 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl)–treated PBMCs served as the control group. hAD-MSCs were primed with a conditioned medium derived from the PBMCs after stimulation. B Representative flow cytometry graphs of cell viability were analyzed with Annexin V (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI). C Summary of PBMCs viability analyses. The mean data were normalized to the control group and presented as a percentage ratio. D Summary of 24 h analyses of IL-6 and IL-10 levels in cell culture supernatants from conditioned media and media upon hAD-MSCs exposure to conditioned media (primed hAD-MSCs, pMSCs). E Summary of hAD-MSCs viability analyses upon stimulation with conditioned PBMCs media. The mean data were normalized to the control group and presented as a percentage ratio. F Analysis of IL-6 and IL-10 levels in supernatants from pMSCs collected after 48-120 h was measured in supernatants using ELISA. Wilcoxon test was used in all analyses (*p < 0.05; n = 6)

Next, we assessed IL-6 and IL-10 expression profiles in conditioned supernatant and the supernatant from stimulated MSCs (Fig. 4D). We found increased production.

of IL-6 after stimulation of MSCs with conditioned media. However, no significant differences have been observed in IL-10 release (Fig. 4D). This suggests that inflammatory signaling, which usually induces anti-inflammatory properties of MSCs, is partially abolished in the presence of LPS or HDM. Next, we wished to analyze the long-term effects of MSCs stimulation with conditioned media. We found that long-term stimulation of MSCs with conditioned media from LPS or HDM exposed PBMCs does not profoundly affect MSCs’ viability (Fig. 4E). Moreover, in contrast to 24 h, longer time points showed a significant increase in both analyzed cytokines compared to control, but no differences over time (Fig. 4F).

Inflammatory signaling reduces MSCs’ differentiation ability

Considering the observed reduction in lrMSC abundance in asthmatic lungs, alongside their impaired immunomodulatory function and differentiation potential in response to LPS and HDM exposure, we subsequently investigated whether direct pro-inflammatory signaling via IL-1β, IFNγ, and TNF compromises the phenotypic stability of these cells.

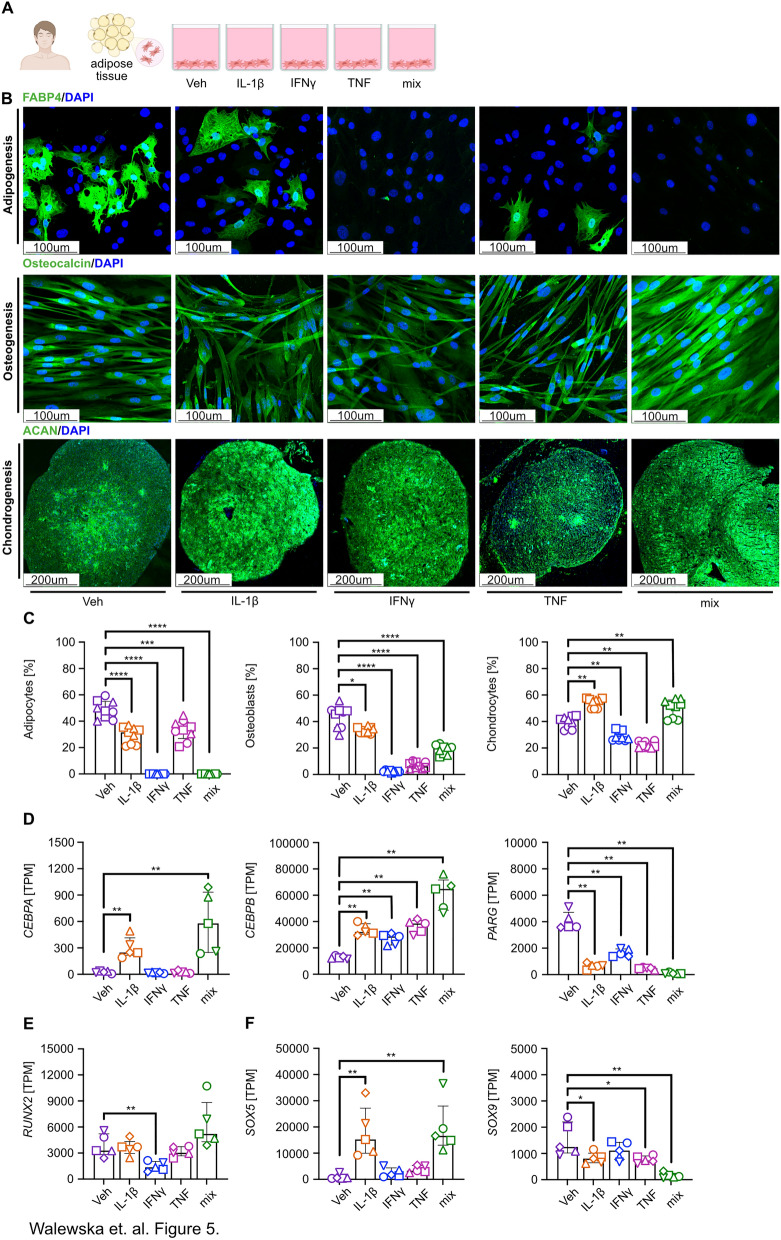

First, MSCs pre-incubated with pro-inflammatory cytokines were subjected to differentiation assays. We observed a significant reduction in differentiated adipocytes following IL-1β and TNF stimulation, whereas IFNγ completely inhibited adipogenesis. Similar results were observed in osteogenic differentiation assays, where exposure to pro-inflammatory cytokines led to a marked reduction in osteoblast formation. Interestingly, stimulation with IL-1β and IFNγ but not TNF resulted in an increased number of chondrocytes. In contrast to adipogenesis, a combined exposure to these cytokines slightly reduced osteoblast differentiation and increased chondrogenesis (Fig. 5B, C). We utilized a house transcriptomic database of MSCs profiling after IL-1β, IFNγ, and TNF stimulation to analyze the expression level of key transcription factors associated with MSCs differentiation and function [9].

Fig. 5.

Impaired potential for adipogenesis and osteogenesis of inflammatory cytokine-primed MSCs. A Schematic representation of the experimental design of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (hAD-MSCs) after stimulation with IL-1β, IFN-γ, TNF, and cytokine mix was subjected to differentiation and gene expression analysis. B Representative confocal images of hAD-MSCs differentiated into adipocytes (fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4 +)), osteoblasts (Osteocalcin +), and chondrocytes (Aggrecan +) after a 24 h priming with IL-1β, IFN-γ, TNF, and cytokine mix. NaCl-primed cells were used as a control (Veh). C The summary of quantification analyzes the proportion of adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes. Adipocytes and osteoblasts were analyzed 14 days after adipogenic differentiation and 21 days after osteogenic differentiation. The cell number was calculated by dividing the number of positively stained cells by the total count. The percentage of positive chondrocytes (day 21 of chondrogenesis differentiation) was assessed by analyzing mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Image analysis was conducted using ImageJ software. Statistical significance was determined using the Wilcoxon test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; n = 3, each with 3 technical replicates). D Transcripts Per Million (TPM) differences in transcriptomic factors associated with adipogenesis (CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein Alpha (CEBPA), CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein Beta (CEBPB), poly (ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG)), E osteogenesis (runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2)), and E, F chondrogenesis (RUNX2, SRY-related HMG-box gene (SOX)5,9). Wilcoxon test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; n = 5)

We found significantly upregulated expression of both transcription factors associated with adipogenic differentiation, namely CEBPA (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha) and CEBPB (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta), after IL-1β stimulation (Fig. 5D). In contrast, IFNγ and TNF stimulation induced CEBPB, but not CEBPA expression (Fig. 5D). Stimulation with cytokine mix elevated expression of both analyzed transcription factors; however, PPARG (Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma) expression, a master regulator of adipocyte differentiation, was significantly decreased when compared to control in all analyzed conditions (Fig. 5D). Expression of RUNX2 (Runt-related transcription factor 2), a key regulator of osteogenesis, has been downregulated by IFNγ, while no significant differences were observed in the remaining conditions (Fig. 5E). Finally, we assessed the expression level of SRY-box transcription factor (SOX)5 and SOX9, key regulators of chondrocyte differentiation. We observed a significant increase in SOX5 expression after IL-1β and cytokine mix stimulation, while no differences were observed after IFNγ and TNF stimulation (Fig. 5F). However, a significant reduction in SOX9 expression was observed after IL-1β, TNF, and cytokine mix stimulation, while no differences were observed after IFNγ exposure (Fig. 5F).

Discussion

The study shows that asthmatic lung inflammation induced by HDM exposure leads to a significant reduction in lrMSCs in a murine model. Moreover, the remaining lrMSCs exhibit diminished adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation potential and lack immunomodulatory activities. To further explore these findings, we employed in vitro models using hAD-MSCs, which serve as a relevant human model system to study responses to inflammatory stimulations [31–35]. These cells are widely used due to their accessibility, high proliferative capacity, and multipotency [36, 37]. Their consistent responsiveness to pro-inflammatory cues enables mechanistic insight that complements and extends our in vivo murine findings, thereby enhancing the translation relevance of the study. Employing hAD-MSCs, we showed that LPS and HDM exposure markedly impair their differentiation potential and block anti-inflammatory activities. Notably, this inhibitory effect persists in the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines released by PBMCs in response to LPS and HDM exposure. Moreover, our findings indicate that inflammatory signaling with pro-inflammatory cytokines, independent of LPS and HDM exposure, significantly attenuates growth factor-induced adipogenesis and osteogenesis differentiation.

Tissue-resident MSCs play an important role in maintaining tissue homeostasis. They serve as a reservoir of regenerative cells and actively modulate the local microenvironment through paracrine signaling and immunomodulatory activities [18, 38]. In fact, MSCs contribute to the repair processes by direct differentiation abilities but also indirectly via the secretion of soluble mediators regulating cell proliferation and differentiation. Moreover, they serve as orchestrators of the tissue microenvironment through their diverse immunomodulatory functions [39]. Substantial evidence supports the critical role of MSCs residing in the lower airways in preserving pulmonary homeostasis. In particular, lrMSCs have been shown to contribute significantly to maintaining lung structural integrity and regulating tissue regeneration [18, 40, 41]. Loss of lrMSCs during the bleomycin-induced lung injury model leads to higher fibrosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension, with an increased number of lymphocytes and granulocytes in bronchoalveolar fluid and T cell effector proliferation [42–44]. In human settings, MSCs isolated from lung transplant recipients effectively suppress T cell proliferation in vitro, potentially impacting immune responses in post-lung transplantation [45, 46]. However, our findings suggest that chronic inflammation may impair the regenerative and immune-modulatory functions of tissue-resident MSCs, which may lead to disease progression. Nevertheless, it remains elusive, how local inflammation reduces the number of lrMSCs. This is even more intriguing given our in vitro evidence demonstrating that prolonged exposure to LPS and HDM (including its proteolytic components) did not compromise MSCs’ viability. It has been recently suggested that MSCs’ apoptosis may be mediated by cytotoxic cells [47]. Notably, in utilized in this study T2-low asthmatic airway inflammation model, we observed activation of cytotoxic cells with high levels of IFNγ and TNF, indicating a potential link between cytotoxic-mediated mechanisms of lrMSCs reduction. However, in this study, we also aimed to assess the potential depletion of the MSC reservoir in the bone marrow. Our data clearly showed that the bone marrow reservoir of MSCs is not depleted in asthmatic mice; rather, the functional activity of the remaining MSCs was significantly impaired. It is therefore tempting to speculate that, due to the functional failure of these cells, they are unable to control inflammation within the lungs. However, its significance in asthma development remains unexplored.

The experimental asthma model employed in this study is a recognized translational model, as it accurately mimics the inflammatory mechanisms and epithelial barrier dysfunction characteristic of human asthma [27]. Sensitization and challenge are achieved through the intranasal administration of HDM, thereby eliciting local immune responses in the lower airways without the need for systemic activation [48]. Given a leaking barrier in this model, it is highly probable that lrMSCs, typically localized within the vascular niche, are directly exposed to HDM, which impairs their anti-inflammatory capabilities [49–51]. This observation contrasts with our previous findings, where intranasally administered hAD-MSCs in an HDM-induced lung inflammation model effectively attenuated the inflammatory response and partially restored epithelial barrier function [27]. Notably, in that study, MSCs were not administered simultaneously with HDM extract. They were delivered on days when the mice were not subjected to the HDM challenge. Thus, we assumed that in our previous research, the lungs at least partially cleared residual HDM, or its activity has been reduced/abolished. Consequently, the MSCs were influenced solely by the cytokines present in the BALF, activating their immune modulatory properties.

It has been reported that MSCs cultured with inflammatory cytokines (including IL-1β, IFNγ, and TNF) [52–54], exposed to hypoxia [55, 56], or supplemented with epigenetic modifiers [57–59] induce their immunosuppressive activities. However, we showed that MSCs stimulation with inflammatory cytokines in the presence of LPS or HDM induces high levels of IL-6. The IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine with essential roles in immune regulation and tissue homeostasis [60]. More precisely, it is involved in neutrophil recruitment, macrophage polarization, Th17 responses promotion, as well as B cell maturation and differentiation towards plasma cells, and inhibits regulatory T cell activity [61–64]. In addition, it may contribute to lung remodeling and fibrosis [65, 66]. Therefore, it seems that LPS and HDM exposure may induce proinflammatory activity of these cells. In fact, IL-6 production by MSCs has been reported previously as a support of CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor differentiation and as one of the key factors of tumor tissue remodeling [67]. However, it remains unexplored whether MSC-derived IL-6 may contribute to lung remodeling in asthma.

Our findings demonstrate that inflammatory signaling in MSCs enhances the stability of their phenotype by inhibiting their differentiation potential towards adipocytes and osteoblasts. This effect is associated with a downregulation of key transcription factors governing these processes, specifically CEBPB, PARG, and RUNX2. Notably, we observed that, following stimulation, MSCs exhibited an increased ability for chondrocyte differentiation. However, it is important to acknowledge that MSCs’ chondrogenic differentiation requires cellular condensation, a process that cannot be achieved under conditions of intranasal administration [68, 69]. Based on these observations, we propose that MSCs priming with pro-inflammatory cytokines may contribute to the stabilization of their phenotype and, as suggested by previous studies, effectively enhance their anti-inflammatory therapeutic potential. This state is in agreement with previous reports proposing pre-education of MSCs as a strategy for enhancing their therapeutic potential [17].

Conclusions

In summary, our study demonstrates that asthmatic inflammation reduces the number of MSCs residing in the lower airways. The mechanisms underlying this effect remain unclear. However, we provide evidence that the remaining MSCs exhibit a loss of functional properties, potentially contributing to the progression of asthmatic inflammation by losing their regulatory role in its resolution. Moreover, our findings indicate that direct exposure of MSCs to LPS and HDM suppresses their effector functions, attenuating their immune regulatory activities. This effect may have important implications for further MSC-based interventions. Additionally, we showed that preincubation with inflammatory mediators further restricts MSCs’ differentiation potential, thereby stabilizing their phenotype. Our findings underscore the need for further research into MSCs’ stability and the role of chronic inflammation on their functionality to enhance the creation and implementation of MSC-based therapies. However, further studies are required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the observed phenomena, to define the fate of MSCs in chronically inflamed lungs, and to clarify their possible contribution to lung remodeling.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

All authors recognized Agnieszka Popielska, MSc, and the Experimental Medicine Centre employees for technical support. The authors declare that they have not used AI-generated work in this manuscript. This manuscript was proofread with the assistance of artificial intelligence to ensure that the text is free of errors in grammar, spelling, punctuation, and tone. All edits were reviewed and approved by the authors to maintain accuracy and intended meaning.

Abbreviations

- CEBPA

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha

- CEBPB

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- DAPI

4’,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

- FABP4

Fatty acid binding protein 4

- H&E

Hematoxylin–eosin

- hAD-MSCs

Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells

- HDM

House dust mite

- ISCT

International society for cellular therapy

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- LrMSCs

Lung-resident mesenchymal stromal cells

- NaCl

0.9% Sodium chloride

- MACS buffer

PBC with 2 ml ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid per 498 ml

- PARG

Poly (ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase

- PAS

Periodic acid-schiff

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PFA

Paraformaldehyde

- R10 media

RPMI1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

- RUNX2

Runt-related transcription factor 2

- SOX5

SRY-box transcription factor 5

- SOX9

SRY-box transcription factor 9

Author contributions

Conceptualization: AE; Data Collection and Analysis: AW, MT, SK, AT, AJ, KB, MR, MD, JR-G, MM; Material (Patient and Blood Donors Qualification): HRH, PR, DS; Formal analysis: AW; Visualization: AW, AT; AE; Writing: AW, MM, AE; Review and Editing: MM, AE.

Funding

The study was supported by the Medical University of Bialystok’s statutory funding. The publication was written during UMB doctoral studies for AW. MT was supported by the Foundation for Polish Science START 2023.

Data availability

All datasets may be available under reasonable request from the corresponding author, subject to ethical and legal considerations.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Bialystok (for Buffy Coat Collection Approval No: R-I-002/634/2018 approved 28 February 2019 entitled: “Assessment of human acellular dermal matrices and cellular therapies in diabetic wound healing efficacy”, for MSC collection Approval No: APK.002.114.2021 from 25.02.2021 entitled: Utilization of Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Fibroblasts, and Acellular Scaffolds Based on Human Skin Derived from Dermal-Fat Folds in Experimental Models). All animal experiments were approved by the Local Ethical Committee in Olsztyn (Approval No: number 35/2019 from 26 April 2019, entitled: Application of Human Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hADMSCs) in the Control of House Dust Mite (HDM)-Induced Allergic Lung Inflammation). The work has been reported in line with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript. The authors confirm that the manuscript represents original work and has not been published or submitted elsewhere, in whole or in part.

Competing interests

MT reports National Science Centre (grant no. 2020/37/N/NZ5/04144); MM reports earlier personal payments from Astra Zeneca, GSK, Sanofi, Berlin-Chemie/Menarini, Chiesi, Lek-AM, Takeda, Teva, Novartis, CSL Behring, Celon, and support for attending meetings from Chiesi, Astra Zeneca, GSK, Berlin-Chemie/Menarini. AE reports National Science Centre (grant no. 2020/37/N/NZ5/04144), National Centre for Research and Development (POLTUR3/MT-REMOD/2/2019). The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All authors read and accepted the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/12/2025

The original article has been updated to re-implement an omitted ESM.

References

- 1.Boonpiyathad T, Sözener ZC, Satitsuksanoa P, et al. Immunologic mechanisms in asthma. Semin Immunol. 2019;46: 101333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. The immunology of asthma. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(1):45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. The basic immunology of asthma. Cell. 2021;184(6):1469–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramadan AA, Gaffin JM, Israel E, et al. Asthma and corticosteroid responses in childhood and adult asthma. Clin Chest Med. 2019;40(1):163–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray A, Kolls JK. Neutrophilic inflammation in asthma and association with disease severity. Trends Immunol. 2017;38(12):942–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kallis C, Morgan A, Fleming L, et al. Prevalence of poorly controlled asthma and factors associated with specialist referral in those with poorly controlled asthma in a paediatric asthma population. J Asthma Allergy. 2023;16:1065–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedenstein AJ, Piatetzky-Shapiro II, Petrakova KV. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1966;16(3):381–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedenstein AJ, Petrakova KV, Kurolesova AI, et al. Heterotopic of bone marrow. Analysis of precursor cells for osteogenic and hematopoietic tissues. Transplantation. 1968;6(2):230–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walewska A, Janucik A, Tynecka M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells under epigenetic control - the role of epigenetic machinery in fate decision and functional properties. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(11):720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong Y, Li Z, Zou S, et al. Vangl2 limits chaperone-mediated autophagy to balance osteogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells. Dev Cell. 2021;56(14):2103-2120.e2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiang S, Li Z, Fritch MR, et al. Caveolin-1 mediates soft scaffold-enhanced adipogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang D, Li Y, Ma Z, et al. Collagen hydrogel viscoelasticity regulates MSC chondrogenesis in a ROCK-dependent manner. Sci Adv. 2023;9(6):eade9497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Sousa PA, Perfect L, Ye J, et al. Hyaluronan in mesenchymal stromal cell lineage differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells: application in serum free culture. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;15(1):130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolstova T, Dotsenko E, Kozhin P, et al. The effect of TLR3 priming conditions on MSC immunosuppressive properties. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14(1):344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burnham AJ, Foppiani EM, Goss KL, et al. Differential response of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) to type 1 ex vivo cytokine priming: implications for MSC therapy. Cytotherapy. 2023;25(12):1277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbaszadeh H, Ghorbani F, Abbaspour-Aghdam S, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma: mesenchymal stem cells and their extracellular vesicles as potential therapeutic tools. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tynecka M, Moniuszko M, Eljaszewicz A. Old friends with unexploited perspectives: current advances in mesenchymal stem cell-based therapies in asthma. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2021;17(4):1323–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doherty DF, Roets L, Krasnodembskaya AD. The role of lung resident mesenchymal stromal cells in the pathogenesis and repair of chronic lung disease. Stem Cells. 2023;41(5):431–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steens J, Klar L, Hansel C, et al. The vascular nature of lung-resident mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2021;10(1):128–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murrison LB, Brandt EB, Myers JB, et al. Environmental exposures and mechanisms in allergy and asthma development. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(4):1504–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batra M, Dharmage SC, Newbigin E, et al. Grass pollen exposure is associated with higher readmission rates for pediatric asthma. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33(11): e13880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Amato G, Chong-Neto HJ, Monge Ortega OP, et al. The effects of climate change on respiratory allergy and asthma induced by pollen and mold allergens. Allergy. 2020;75(9):2219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carayol N, Birnbaum J, Magnan A, et al. Fel d 1 production in the cat skin varies according to anatomical sites. Allergy. 2000;55(6):570–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding Y, Gong P, Jiang J, et al. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells primed by inflammatory cytokines alleviate psoriasis-like inflammation via the TSG-6-neutrophil axis. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(11):996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hackel A, Vollmer S, Bruderek K, et al. Immunological priming of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells and their extracellular vesicles augments their therapeutic benefits in experimental graft-versus-host disease. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1078551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hackel A, Aksamit A, Bruderek K, et al. TNF-α and IL-1β sensitize human MSC for IFN-γ signaling and enhance neutrophil recruitment. Eur J Immunol. 2021;51(2):319–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tynecka M, Janucik A, Tarasik A, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells effectively limit house dust mite extract-induced mixed granulocytic lung inflammation. Allergy. 2024;79(11):3157–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tynecka M, Janucik A, Niemira M, et al. The short-term and long-term effects of intranasal mesenchymal stem cell administration to noninflamed mice lung. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 967487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horwitz EM, Le Blanc K, Dominici M, et al. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: the international society for cellular therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005;7(5):393–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan HT, Hagner S, Ruchti F, et al. Tight junction, mucin, and inflammasome-related molecules are differentially expressed in eosinophilic, mixed, and neutrophilic experimental asthma in mice. Allergy. 2019;74(2):294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bispo ECI, Argañaraz ER, Neves FAR, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of IFN-γ licensed adipose-mesenchymal stromal cells in an in vitro model of inflammation generated by SARS-CoV-2 antigens. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):24235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abreu SC, Antunes MA, Xisto DG, et al. Bone marrow, adipose, and lung tissue-derived murine mesenchymal stromal cells release different mediators and differentially affect airway and lung parenchyma in experimental asthma. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6(6):1557–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang ZG, He ZY, Liang S, et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of exosomes derived from human bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao X, Wu J, Yuan R, et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy for reverse bleomycin-induced experimental pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):13183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brizio M, Mancini M, Lora M, et al. Cytokine priming enhances the antifibrotic effects of human adipose derived mesenchymal stromal cells conditioned medium. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;15(1):329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu Y, Liu T, Song K, et al. Adipose-derived stem cell: a better stem cell than BMSC. Cell Biochem Funct. 2008;26(6):664–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baer PC, Geiger H. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal/stem cells: tissue localization, characterization, and heterogeneity. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012: 812693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J, Gao J, Liang Z, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and their microenvironment. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han Y, Yang J, Fang J, et al. The secretion profile of mesenchymal stem cells and potential applications in treating human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, Shi M, Tong L, et al. Lung-resident mesenchymal stem cells promote repair of LPS-induced acute lung injury via regulating the balance of regulatory T cells and Th17 cells. Inflammation. 2019;42(1):199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L, Feng Y, Dou M, et al. Study of mesenchymal stem cells derived from lung-resident, bone marrow and chorion for treatment of LPS-induced acute lung injury. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2022;302: 103914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang X, Sun W, Jing X, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress modulates the fate of lung resident mesenchymal stem cell to myofibroblast via C/EBP homologous protein during pulmonary fibrosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang C, Gu S, Cao H, et al. miR-877-3p targets Smad7 and is associated with myofibroblast differentiation and bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao H, Chen X, Hou J, et al. The Shh/Gli signaling cascade regulates myofibroblastic activation of lung-resident mesenchymal stem cells via the modulation of Wnt10a expression during pulmonary fibrogenesis. Lab Invest. 2020;100(3):363–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jarvinen L, Badri L, Wettlaufer S, et al. Lung resident mesenchymal stem cells isolated from human lung allografts inhibit T cell proliferation via a soluble mediator. J Immunol. 2008;181(6):4389–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laing AG, Fanelli G, Ramirez-Valdez A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit T-cell function through conserved induction of cellular stress. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3): e0213170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galleu A, Riffo-Vasquez Y, Trento C et al. Apoptosis in mesenchymal stromal cells induces in vivo recipient-mediated immunomodulation. Sci Transl Med 2017;9(416). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Branchett WJ, Lloyd CM. Regulatory cytokine function in the respiratory tract. Mucosal Immunol. 2019;12(3):589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hellings PW, Steelant B. Epithelial barriers in allergy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(6):1499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Messaoud-Nacer Y, Culerier E, Rose S et al. STING-dependent induction of neutrophilic asthma exacerbation in response to house dust mite. Allergy 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Ma Q, Qian Y, Jiang J, et al. IL-33/ST2 axis deficiency exacerbates neutrophil-dominant allergic airway inflammation. Clin Transl Immunology. 2021;10(6): e1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prasanna SJ, Gopalakrishnan D, Shankar SR, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, IFNgamma and TNFalpha, influence immune properties of human bone marrow and Wharton jelly mesenchymal stem cells differentially. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(2): e9016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calligaris M, Zito G, Busà R, et al. Proteomic analysis and functional validation reveal distinct therapeutic capabilities related to priming of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells with IFN-γ and hypoxia: potential implications for their clinical use. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1385712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu H, Zhu X, Cao X, et al. IL-1β-primed mesenchymal stromal cells exert enhanced therapeutic effects to alleviate chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome through systemic immunity. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yasan GT, Gunel-Ozcan A. Hypoxia and hypoxia mimetic agents as potential priming approaches to empower mesenchymal stem cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;19(1):33–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wobma HM, Kanai M, Ma SP, et al. Dual IFN-γ/hypoxia priming enhances immunosuppression of mesenchymal stromal cells through regulatory proteins and metabolic mechanisms. J Immunol Regen Med. 2018;1:45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pan Q, Kuang X, Cai S, et al. miR-132-3p priming enhances the effects of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes on ameliorating brain ischemic injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCully M, Conde J, Baptista V, P, et al. Nanoparticle-antagomiR based targeting of miR-31 to induce osterix and osteocalcin expression in mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0192562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Witte SFH, Peters FS, Merino A, et al. Epigenetic changes in umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells upon stimulation and culture expansion. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(7):919–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murakami M, Kamimura D, Hirano T. Pleiotropy and specificity: insights from the interleukin 6 family of cytokines. Immunity. 2019;50(4):812–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Halwani R, Sultana A, Vazquez-Tello A, et al. Th-17 regulatory cytokines IL-21, IL-23, and IL-6 enhance neutrophil production of IL-17 cytokines during asthma. J Asthma. 2017;54(9):893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saradna A, Do DC, Kumar S, et al. Macrophage polarization and allergic asthma. Transl Res. 2018;191:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin Y, Pan Z, Zhou J, et al. Hedgehog signaling pathway regulates Th17 cell differentiation in asthma via IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;139: 112771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ladjemi MZ, Lecocq M, Weynand B, et al. Increased IgA production by B-cells in COPD via lung epithelial interleukin-6 and TACI pathways. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(4):980–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pedroza M, Schneider DJ, Karmouty-Quintana H, et al. Interleukin-6 contributes to inflammation and remodeling in a model of adenosine mediated lung injury. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7): e22667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shieh JM, Tseng HY, Jung F, et al. Elevation of IL-6 and IL-33 levels in serum associated with lung fibrosis and skeletal muscle wasting in a bleomycin-induced lung injury mouse model. Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:7947596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Hagan-Wong K, Nadeau S, Carrier-Leclerc A, et al. Increased IL-6 secretion by aged human mesenchymal stromal cells disrupts hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells’ homeostasis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(12):13285–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li YY, Lam KL, Chen AD, et al. Collagen microencapsulation recapitulates mesenchymal condensation and potentiates chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells - a matrix-driven in vitro model of early skeletogenesis. Biomaterials. 2019;213: 119210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu S. Scaffolded chondrogenic spheroid-engrafted model. Methods Mol Biol. 2024;2766:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets may be available under reasonable request from the corresponding author, subject to ethical and legal considerations.