Abstract

Background

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has the capacity to promote neuronal survival that is crucial to neurological recovery after closed head injury (CHI). We previously reported that intracerebral-transplanted induced neural stem cells (iNSCs) can up-regulate BDNF levels to exert neurotrophic effects in CHI-damaged brains. Here we aim to elucidate the mechanism of BDNF up-regulation in iNSCs.

Methods

We performed iNSC and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated microglia co-culture experiments, iNSC transplantation, loss-of-function study, morphological and molecular biological analyses to uncover the mechanism underlying the overexpression of BDNF in iNSCs.

Results

Our results indicated that co-culture with LPS-activated microglia up-regulated the expression levels of BDNF, as well as Bdnf exons I and IV in iNSCs. Notably, AKT inhibition could counteract the effects of co-culture with LPS-activated microglia that decreased enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) and H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) levels at Bdnf promoter IV but increased EZH2 phosphorylation and BDNF expression in iNSCs. Additionally, blockage of AKT could counteract the effects of co-culture with LPS-activated microglia that increased cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV, as well as CREB phosphorylation and BDNF expression in iNSCs. Furthermore, blocking AKT activity in grafted iNSCs could reduce BDNF expression in the injured cortices of CHI mice.

Conclusions

In short, our study shows that AKT signaling may regulate BDNF expression in iNSCs. Activation of AKT can up-regulate BDNF expression through inactivating EZH2 as well as reducing EZH2 and H3K27me3 levels at Bdnf promoter IV, meanwhile activating CREB as well as increasing CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13287-025-04489-x.

Keywords: Induced neural stem cell, BDNF, Closed head injury, Microglia, AKT, EZH2, H3K27me3, CREB

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13287-025-04489-x.

Introduction

Closed head injury (CHI) results in neuronal loss, which is one of the main causes of neurological impairment [1]. Neural stem cells (NSCs) with the capability to differentiate into mature neurons have been suggested as a potential treatment for CHI-induced neurological impairment [2, 3]. However, limited source of NSCs together with ethical concerns complicate efforts towards their clinical application [4]. Furthermore, limiting neuronal differentiation efficiency of intracerebral-transplanted NSCs can hardly explain their beneficial effects on neuronal survival in the injured cortices of CHI models [5]. Emerging evidence suggests that NSCs secrete brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)—an evolutionarily conserved neurotrophin—to mitigate neuronal apoptosis, thereby promoting survival in injury contexts [6, 7]. This mechanism may represent a potential therapeutic strategy for addressing neurological deficits induced by CHI.

With advances in regenerative medicine, techniques represented by cell reprogramming promise to break the limitations of NSC application [8]. We previously demonstrated that induced neural stem cells (iNSCs) directly reprogrammed from autologous somatic cells have the same ability to secrete BDNF as NSCs [9]. Recently we indicated that grafted iNSCs can up-regulate BDNF levels to exert neurotrophic effects in CHI-damaged brains [10]. However, deciphering of the mechanism by which BDNF is up-regulated in the injured cortices of CHI mice receiving iNSCs remains elusive, due in part to the complex regulatory and genetic structure of the Bdnf gene.

The Bdnf gene in mice contains eight 5’ noncoding exons (I-VIII), each of which is alternatively spliced to the common 3’ protein-coding exon (IX) to form multiple mRNA transcripts that encode the same BDNF protein [11]. Moreover, the transcription of each Bdnf exon is driven by a unique promoter whose transcriptional capacity can be modulated in response to various stimuli [12]. For example, changes in histone modifications triggered by extracellular stimuli at specific Bdnf promoters can affect BDNF expression [13]. Additionally, intracellular signaling activated by these stimuli may recruit certain transcription factors, such as cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), to regulate Bdnf exon transcription by binding to its promoters [14].

Our mechanistic studies reveal that intracerebrally transplanted iNSCs exhibit microenvironment-responsive plasticity, with their functional dynamics being modulated by specific chemotactic signals [15]. A representative regulator identified through is C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12). Notably, CXCL12 which secreted by activated microglia post-CHI mechanistically up-regulates both C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) and complement receptor type 1-related protein y (Crry) expression via the AKT signaling. Furthermore, recent evidence has revealed that AKT signaling plays important roles in the regulation of BDNF expression [16]. For instance, AKT signaling mediates histone modifications at selective Bdnf promoters to modulate BDNF expression [17]. Additionally, AKT signaling recruits certain transcription factors (including CREB) to induce BDNF expression by binding to specific Bdnf promoters [18]. Therefore, we hypothesized that BDNF up-regulation in iNSCs may have similar mechanisms. In this study, we aimed to elucidate the mechanism of BDNF up-regulation in iNSCs by using iNSC and microglia co-culture experiments, iNSC transplantation, loss-of-function study, morphological and molecular biological analyses.

Methods

Cell cultures and co-culture experiments

All experimental procedures were performed in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Chinese PLA General Hospital (approval No. 2016-40, approval date: March 16, 2016). The work has been reported in line with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. Cell cultures and experimental co-culture systems were established according to standardized protocols described in prior methodology literature [15], with strict adherence to aseptic techniques. Detailed methods were provided in Additional file 1.

CHI models and iNSC transplantation

Specific-pathogen-free grade healthy adult (12–14 weeks old) male C57BL/6 (B6) mice weighing 24–32 g (Charles River Laboratories, Beijing, China, license No. SCXK (Jing) 2016-0006) were kept four per cage in a temperature (21 ± 1℃) and humidity (50 ± 20%) controlled room with food and water ad libitum. CHI models were established by a standardized weight-drop device and CHI-induced neurological impairment was evaluated using the neurological severity score (NSS) (Additional Table 1) as previously reported [19]. INSC transplantation was conducted as previously described [20]. Detailed methods were provided in Additional file 2.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

To measure the levels of BDNF, supernatants from iNSC mono-culture, microglia mono-culture, iNSCs and microglia co-culture were collected at 12, 24 and 48 h and purified by centrifugation for 20 min at 1509 x g. BDNF levels in the supernatants were identified using enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Cell counting kit-8 assay

Cell proliferation ability was evaluated by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. INSCs and microglia in the lower chambers were collected and assayed at 12, 24 and 48 h. A microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cleveland, OH, USA) was used to measure the optical density at 450 nm (OD450), which reflected the cell proliferation ability.

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay

RNA extracted from iNSCs and microglia was reversely transcribed into cDNA using the QuantScript RT kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) and assessed by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay using the SYBR-Green Master Mix (TaKaRa Biotech, Dalian, China) and a ViiA7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The qRT-PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 5 min denaturation, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 35 s. Expression levels were calculated relative to that of GAPDH using the ΔCt method (2−ΔΔCt). The sequences of the PCR primer pairs are listed in Additional Table 2 and designed with reference to the primer sequences reported in these studies [15, 21, 22].

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

INSCs were treated with 1% formaldehyde to obtain protein-DNA crosslinks. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed using the Pierce Magnetic ChIP Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The immunoprecipitating antibodies used in this study are listed in Additional Table 3. After crosslink reversal and DNA purification, immunoprecipitated DNA samples were quantified by qRT-PCR assay. Fold enrichment values were examined relative to IgG controls and normalized to input values. The sequences of the PCR primer pairs are listed in Additional Table 2.

Western blot analysis

Mouse was anesthetized through the intranasal administration of isoflurane and sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and fresh brain tissue was collected. Protein was extracted from iNSCs or brain tissue using the RIPA reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Fermentas, Burlington, Canada). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein samples were heated for 10 min at 95 °C, separated using SDS-PAGE (35 µg per lane), and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The blots were blocked with 5% BSA in TBST for 1 h at room temperature and subsequently detected using incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After several washes, the blots were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunoblots were visualized using the SuperSignal ECL (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The intensities of bands were calculated using the Image Lab Version 4.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The results were expressed relative to the control and normalized to GAPDH. The antibodies used in this study are listed in Additional Table 3.

Loss-of-function study

To inhibit AKT activity, we utilized LY294002 (20 µM, CST, Beverly, MA, USA) to pretreat iNSCs for 1 h prior to co-culture experiments. In addition, to knock down AKT in iNSCs, we transfected iNSCs with AKT-specific shRNA (sc-29196-V, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or control shRNA (sc-108080, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) according to the shRNA manufacturer’s instructions.

To block CREB activity, we utilized 666 − 15 (1 µM, MedChem Express, Princeton, NJ, USA) to pretreat iNSCs for 2 h prior to co-culture experiments. In addition, to knock down CREB in iNSCs, we transfected iNSCs with CREB-specific shRNA (sc-35111-V, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or control shRNA (sc-108080, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) according to the shRNA manufacturer’s instructions.

Morphological analysis

Morphological analysis was accomplished as previously reported [20]. Briefly, slides of iNSCs and brain tissues (an average of 20 equally spaced slides (100-µm intervals) containing samples from throughout the injured cortex (a series of 5-mm coronal sections) of each brain was assessed) were blocked for 1 h using 10% BSA/0.3% TritonX-100 and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. After being washed in PBS, they were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies. After several washes with PBS, the nuclei were stained with DAPI Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) and staining was detected via fluorescent microscopy (DM3000, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), and confocal laser scanning microscopy (TCS SP5 II, Leica). The antibodies used in this study are listed in Additional Table 2.

Statistical analysis

SPSS17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). We conducted a Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test to determine statistical significance. P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Co-culture with LPS-activated microglia up-regulates BDNF expression in iNSCs

To elucidate the mechanism of BDNF up-regulation in iNSCs, we carried out iNSC and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated microglia co-culture experiments. The result suggested that BDNF levels were significantly higher in the iNSC mono-culture supernatant than in the microglia mono-culture supernatant, yet substantially lower than in the co-culture supernatant at 12, 24 and 48 h after co-culture (P < 0.05; Fig. 1A and B). To evaluate the effect of cell proliferation on BDNF levels, we performed CCK-8 assays and observed no significant changes in proliferation of iNSCs between the iNSC mono-culture and co-culture groups at 12, 24 and 48 h after co-culture (Fig. 1C and D). Furthermore, no significant differences were detected in the proliferation of microglia between the microglia mono-culture and co-culture groups at the same time points (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Co-culture with LPS-activated microglia up-regulates BDNF expression in iNSCs. (A) Schematic representation of the ELISA design (green dots represent iNSCs; red dots represent LPS-activated microglia). (B) ELISA results showing the levels of BDNF in cell culture supernatants among the three groups at 12, 24 and 48 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (C) Schematic representation of the CCK-8 assay design (green dots represent iNSCs; red dots represent LPS-activated microglia). (D, E) CCK-8 assay results showing the proliferation of iNSCs (D) and microglia (E) between the iNSC or microglia mono-culture and co-culture groups at 12, 24 and 48 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; student’s t-test). (F, G) qRT-PCR assay results showing the levels of Bdnf in iNSCs (F) and microglia (G) between the iNSC or microglia mono-culture and co-culture groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001). (H) qRT-PCR assay results showing the levels of Bdnf exons I-VIII in iNSCs between the iNSC mono-culture and co-culture groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; student’s t-test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CCK-8: cell counting Kit-8; ELISA: enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; iNSCs: induced neural stem cells; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; qRT-PCR: quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

Then, we exerted qRT-PCR assays to assess Bdnf gene expression in these cells. In contrast to its expression in mono-culture of iNSCs, Bdnf gene expression was significantly up-regulated in iNSCs co-cultured with microglia for 24 hours (P < 0.05; Fig. 1F). However, Bdnf gene expression in microglia was not affected by iNSC co-culture (Fig. 1G). The Bdnf mRNA contains one of the eight 5’ noncoding exons (I-VIII), which is spliced to the common 3’ protein-coding exon (IX). To examine the candidate noncoding exons which contribute to the transcription of Bdnf mRNA, we conducted qRT-PCR assays to analyze Bdnf exons and found that the levels of exons I and IV in iNSCs in the co-culture group were substantially higher than those in the iNSC mono-culture group (P < 0.05; Fig. 1H). These findings are proof of principle that co-culture with LPS-activated microglia up-regulated the expression levels of BDNF, as well as Bdnf exons I and IV in iNSCs.

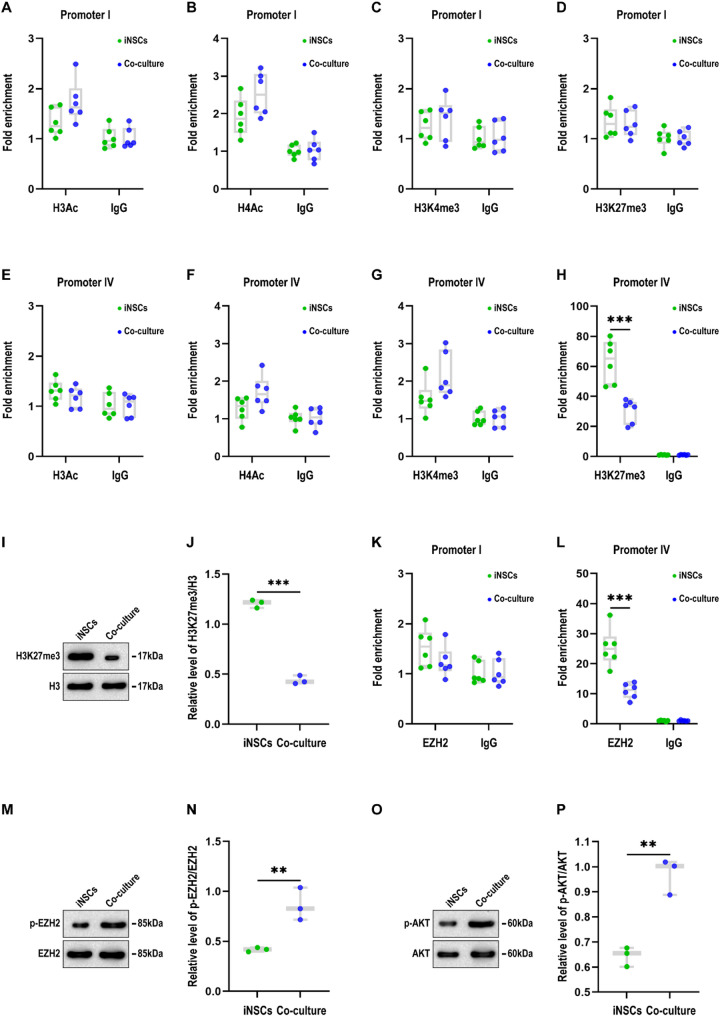

Co-culture with LPS-activated microglia decreases H3K27me3 and EZH2 levels at Bdnf promoter IV but increases EZH2 phosphorylation in iNSCs

To figure out the mechanism underlying the overexpression of Bdnf exons I and IV, we implemented ChIP assays to determine the levels of histone modifications at the promoter of Bdnf exons I and IV in iNSCs co-cultured with LPS-activated microglia for 24 h. No change in histone H3 acetylation (H3Ac), H4 acetylation (H4Ac), H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), or H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) was detected at Bdnf promoter I (Fig. 2A-D). In addition, H3Ac, H4Ac or H3K4me3 levels revealed no significant changes at Bdnf promoter IV (Fig. 2E-G). In contrast, co-culture with LPS-activated microglia significantly reduced H3K27 trimethylation at Bdnf promoter IV in iNSCs (P < 0.05; Fig. 2H). To verify these findings, we performed western blot analysis and found that the levels of H3K27me3/H3 in iNSCs in the co-culture group were significantly lower than those in the iNSC mono-culture group (P < 0.05; Fig. 2I and J).

Fig. 2.

Co-culture with LPS-activated microglia decreases H3K27me3 and EZH2 levels at Bdnf promoter IV but increases EZH2 phosphorylation in iNSCs (A-D) ChIP assay results showing the levels of histone H3 acetylation (H3Ac; A), H4 acetylation (H4Ac; B), H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3; C), and H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3; D) at Bdnf promoter I in iNSCs between the iNSC mono-culture and co-culture groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; student’s t-test). (E-H) ChIP assay results showing the levels of H3Ac (E), H4Ac (F), H3K4me3 (G), and H3K27me3 (H) at Bdnf promoter IV in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001). (I) Representative immunoblots illustrating the levels of H3K27me3 and H3 in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (full-length blots are presented in Additional Fig. 1). (J) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative levels of H3K27me3/H3 in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 3/group; student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001). (K, L) ChIP assay results showing the levels of EZH2 at Bdnf promoter I (K) and IV (L) in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001). (M) Representative immunoblots illustrating the levels of p-EZH2 and EZH2 in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (full-length blots are presented in Additional Fig. 1). (N) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative levels of p-EZH2/EZH2 in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 3/group; student’s t-test, **P < 0.01). (O) Representative immunoblots illustrating the levels of p-AKT and AKT in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (full-length blots are presented in Additional Fig. 1). (P) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative levels of p-AKT/AKT in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 3/group; student’s t-test, **P < 0.01). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ChIP: chromatin immunoprecipitation; EZH2: enhancer of zeste homolog 2; iNSCs: induced neural stem cells

H3K27 trimethylation is catalyzed by the histone methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2). To clarify the mechanism of the reduction of H3K27 trimethylation, we first implemented ChIP assays to investigate whether EZH2 binds to these Bdnf promoters in iNSCs. No change was detected in EZH2 levels at Bdnf promoter I (Fig. 2K), whereas co-culture with LPS-activated microglia significantly decreased EZH2 levels at Bdnf promoter IV in iNSCs (P < 0.05; Fig. 2L). Moreover, accumulating evidence has indicated that EZH2 phosphorylation (p-EZH2) impedes its binding to H3 and suppresses its methyltransferase activity [24]. We then examined western blot analysis and observed significantly higher levels of p-EZH2/EZH2 in iNSCs in the co-culture group than those in the iNSC mono-culture group (P < 0.05; Fig. 2M and N). The above findings indicate that co-culture with LPS-activated microglia decreased H3K27me3 and EZH2 levels at Bdnf promoter IV but increased EZH2 phosphorylation in iNSCs.

AKT signaling regulates EZH2 phosphorylation, H3K27 trimethylation and BDNF expression in iNSCs

Recent studies have elucidated that AKT signaling mediates the phosphorylation and inactivation of EZH2 [24]. Moreover, our prior investigations have established that AKT-mediated signaling critically regulates the functional cross-talk between iNSCs and microglia through upregulation of CXCR4 and Crry [15]. To illuminate the mechanism underlying the phosphorylation of EZH2, we completed western blot analysis and observed a significantly higher level of p-AKT/AKT in iNSCs in the co-culture group than those in the iNSC mono-culture group (P < 0.05; Fig. 2O and P).

To explore the role of AKT signaling in the regulation of EZH2 phosphorylation, H3K27 trimethylation and BDNF expression, we used LY294002 to block AKT activity in iNSCs prior to co-culture experiments. ChIP assays showed that EZH2 and H3K27me3 levels at Bdnf promoter IV in iNSCs in the co-culture (LY294002; iNSCs pretreated with LY294002) group were significantly lower than those in the iNSC mono-culture group but substantially higher than those in the co-culture group (P < 0.05; Fig. 3A and B). Furthermore, western blot analysis informed that the levels of p-AKT/AKT, p-EZH2/EZH2 and BDNF in iNSCs in the co-culture (LY294002) group were significantly higher than those in the iNSC mono-culture group but substantially lower than those in the co-culture group, while the levels of H3K27me3/H3 in iNSCs in the co-culture (LY294002) group were significantly lower than those in the iNSC mono-culture group but substantially higher than those in the co-culture group (P < 0.05; Fig. 3C-G).

Fig. 3.

AKT signaling regulates EZH2 phosphorylation, H3K27 trimethylation and BDNF expression in iNSCs. (A, B) ChIP assay results showing the levels of EZH2 (A) and H3K27me3 (B) at Bdnf promoter IV in iNSCs among the iNSC mono-culture, co-culture and co-culture (LY294002; iNSCs pretreated with LY294002) groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (C) Representative immunoblots illustrating the levels of p-AKT, AKT, p-EZH2, EZH2, H3K27me3, H3, BDNF and GAPDH in iNSCs among the three groups at 24 h after co-culture (full-length blots are presented in Additional Fig. 2). (D-G) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative levels of p-AKT/AKT (D), p-EZH2/EZH2 (E), H3K27me3/H3 (F), and BDNF/GAPDH (G) in iNSCs among the three groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 3/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (H, I) ChIP assay results showing the levels of EZH2 (H) and H3K27me3 (I) at Bdnf promoter IV in iNSCs among the iNSC mono-culture, co-culture, co-culture (Control shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with control shRNA), and co-culture (AKT shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with AKT-specific shRNA) groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). (J) Representative immunoblots illustrating the levels of p-AKT, AKT, p-EZH2, EZH2, H3K27me3, H3, BDNF and GAPDH in iNSCs among the four groups at 24 h after co-culture (full-length blots are presented in Additional Fig. 3). (K-N) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative levels of p-AKT/AKT (K), p-EZH2/EZH2 (L), H3K27me3/H3 (M), and BDNF/GAPDH (N) in iNSCs among the four groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 3/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ChIP: chromatin immunoprecipitation; EZH2: enhancer of zeste homolog 2; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; iNSCs: induced neural stem cells

To further understand these roles of AKT signaling, we transfected iNSCs with an AKT-specific shRNA or control shRNA prior to co-culture experiments. ChIP assays manifested that EZH2 and H3K27me3 levels at Bdnf promoter IV in iNSCs in the co-culture (AKT shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with AKT-specific shRNA) group were substantially lower than those in the iNSC mono-culture group but significantly higher than those in the co-culture and co-culture (Control shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with control shRNA) groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 3H and I). Additionally, western blot analysis demonstrated that the levels of p-AKT/AKT, p-EZH2/EZH2 and BDNF in iNSCs in the co-culture (AKT shRNA) group were significantly higher than those in the iNSC mono-culture group but substantially lower than those in the co-culture and co-culture (Control shRNA) groups, while the levels of H3K27me3/H3 in iNSCs in the co-culture (AKT shRNA) group were significantly lower than those in the iNSC mono-culture group but substantially higher than those in the co-culture and co-culture (Control shRNA) groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 3J-N).

To determine the expression and localization of p-EZH2, H3K27me3 and BDNF, we performed immunofluorescence staining and observed that the relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) values of p-EZH2 and BDNF in iNSCs in the co-culture (AKT shRNA) group were substantially lower than those in the co-culture (Control shRNA) group (P < 0.05; Fig. 4A-C and F). In contrast, the RFI values of H3K27me3 in iNSCs in the co-culture (AKT shRNA) group were substantially higher than those in the co-culture (Control shRNA) group (P < 0.05; Fig. 4D and E). These findings suggest that AKT inhibition could counteract the effects of co-culture with LPS-activated microglia that decreased EZH2 and H3K27me3 levels at Bdnf promoter IV but increased EZH2 phosphorylation and BDNF expression in iNSCs.

Fig. 4.

The expression and localization of p-EZH2, H3K27me3 and BDNF in iNSCs. (A) Representative staining for the p-EZH2+ (green) and BDNF+ (red) depicted p-EZH2 and BDNF levels in iNSCs between the co-culture (Control shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with control shRNA), and co-culture (AKT shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with AKT-specific shRNA) groups at 24 h after co-culture. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm (5 μm in the magnified images). (B, C) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) values of p-EZH2 (B) and BDNF (C) in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001). (D) Representative staining for the H3K27me3+ (green) and BDNF+ (red) depicted H3K27me3 and BDNF levels in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm (5 μm in the magnified images). (E, F) Box-whisker plot depicting the RFI values of H3K27me3 (E) and BDNF (F) in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; EZH2: enhancer of zeste homolog 2; iNSCs: induced neural stem cells

Co-culture with LPS-activated microglia increases CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV, as well as CREB phosphorylation in iNSCs

Recent studies have reported that AKT signaling mediates phosphorylation and activation of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) which initiates the transcription of Bdnf exons by binding to their promoters [18]. We first performed ChIP assays and found that co-culture with LPS-activated microglia significantly increased CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV in iNSCs (P < 0.05; Fig. 5A and B). We then performed western blot analysis and found that the levels of p-CREB/CREB in iNSCs in the co-culture group were significantly higher than those in the iNSC mono-culture group (P < 0.05; Fig. 5C and D). We conclude that co-culture with LPS-activated microglia increases CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV, as well as CREB phosphorylation in iNSCs.

Fig. 5.

Co-culture with LPS-activated microglia increases CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV, as well as CREB phosphorylation in iNSCs. (A, B) ChIP assay results showing the levels of CREB at Bdnf promoter I (A) and IV (B) in iNSCs between the iNSC mono-culture and co-culture groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001). (C) Representative immunoblots illustrating the levels of p-CREB and CREB in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (full-length blots are presented in Additional Fig. 4). (D) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative levels of p-CREB/CREB in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 3/group; student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001). (E, F) ChIP assay results showing the levels of CREB at Bdnf promoter I (E) and IV (F) in iNSCs among the iNSC mono-culture, co-culture and co-culture (666 − 15; iNSCs pretreated with 666 − 15) groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (G) Representative immunoblots illustrating the levels of p-CREB, CREB, BDNF and GAPDH in iNSCs among the three groups at 24 h after co-culture (full-length blots are presented in Additional Fig. 5). (H, I) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative levels of p-CREB/CREB (H) and BDNF/GAPDH (I) in iNSCs among the three groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 3/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (J, K) ChIP assay results showing the levels of CREB at Bdnf promoter I (J) and IV (K) in iNSCs among the iNSC mono-culture, co-culture, co-culture (Control shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with control shRNA), and co-culture (CREB shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with CREB-specific shRNA) groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, ***P < 0.001). (L) Representative immunoblots illustrating the levels of p-CREB, CREB, BDNF and GAPDH in iNSCs among the four groups at 24 h after co-culture (full-length blots are presented in Additional Fig. 6). (M, N) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative levels of p-CREB/CREB (M) and BDNF/GAPDH (N) in iNSCs among the four groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 3/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, ***P < 0.001). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ChIP: chromatin immunoprecipitation; CREB: cAMP response element binding protein; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; iNSCs: induced neural stem cells

To confirm these data, we used 666 − 15 to inhibit CREB activity in iNSCs prior to co-culture experiments. ChIP assays showed that CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV in iNSCs in the co-culture (666 − 15; iNSCs pretreated with 666 − 15) group were significantly higher than those in the iNSC mono-culture group but substantially lower than those in the co-culture group (P < 0.05; Fig. 5E and F). Furthermore, western blot analysis proved that the levels of p-CREB/CREB and BDNF in iNSCs in the co-culture (666 − 15) group were significantly higher than those in the iNSC mono-culture group but substantially lower than those in the co-culture group (P < 0.05; Fig. 5G-I).

To further study the function of CREB, we transfected iNSCs with a CREB-specific shRNA or control shRNA prior to co-culture experiments. ChIP assays revealed that CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV in iNSCs in the co-culture (CREB shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with CREB-specific shRNA) group were substantially lower than those in the co-culture and co-culture (Control shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with control shRNA) groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 5J and K). Additionally, western blot analysis made clear that the levels of p-CREB/CREB and BDNF in iNSCs in the co-culture (CREB shRNA) group were significantly lower than those in the co-culture and co-culture (Control shRNA) groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 5L-N). We draw a conclusion that co-culture with LPS-activated microglia increases CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV, as well as CREB phosphorylation and BDNF expression in iNSCs.

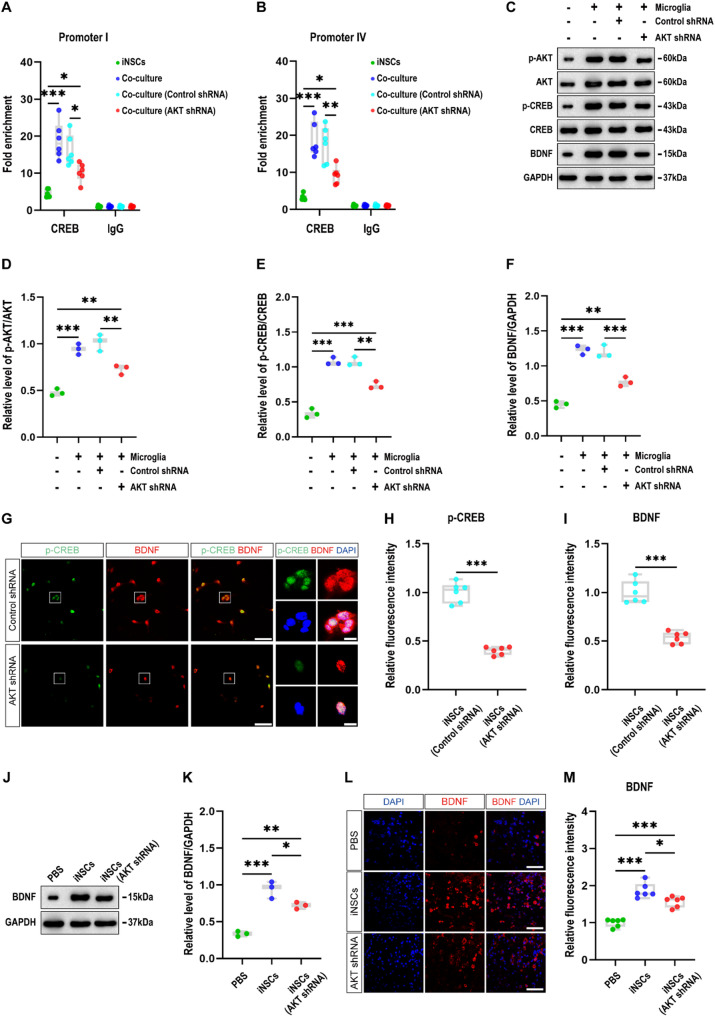

AKT signaling regulates BDNF expression by recruiting CREB to their promoters I and IV in iNSCs

To investigate whether AKT signaling regulates BDNF expression by recruiting CREB to Bdnf promoters, we employed ChIP assays and found that CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV in iNSCs in the co-culture (AKT shRNA) group were substantially higher than those in the iNSC mono-culture group but significantly lower than those in the co-culture and co-culture (Control shRNA) groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 6A and B). Additionally, western blot analysis confirmed that the levels of p-AKT/AKT, p-CREB/CREB and BDNF in iNSCs in the co-culture (AKT shRNA) group were significantly higher than those in the iNSC mono-culture group but substantially lower than those in the co-culture and co-culture (Control shRNA) groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 6C-F).

Fig. 6.

AKT signaling regulates BDNF expression by recruiting CREB to their promoters I and IV in iNSCs. (A, B) ChIP assay results showing the levels of CREB at Bdnf promoter I (A) and IV (B) in iNSCs among the iNSC mono-culture, co-culture, co-culture (Control shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with control shRNA), and co-culture (AKT shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with AKT-specific shRNA) groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (C) Representative immunoblots illustrating the levels of p-AKT, AKT, p-CREB, CREB, BDNF and GAPDH in iNSCs among the four groups at 24 h after co-culture (full-length blots are presented in Additional Fig. 7). (D-F) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative levels of p-AKT/AKT (D), p-CREB/CREB (E), and BDNF/GAPDH (F) in iNSCs among the four groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 3/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (G) Representative staining for the p-CREB+ (green) and BDNF+ (red) depicted p-CREB and BDNF levels in iNSCs between the co-culture (Control shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with control shRNA), and co-culture (AKT shRNA; iNSCs pretreated with AKT-specific shRNA) groups at 24 h after co-culture. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm (5 μm in the magnified images). (H, I) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) values of p-CREB (H) and BDNF (I) in iNSCs between the two groups at 24 h after co-culture (n = 6/group; student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001). (J) Representative immunoblots illustrating the levels of BDNF and GAPDH in the injured cortices among the PBS (CHI mice receiving PBS), iNSC (CHI mice receiving iNSCs pretreated with PBS), and iNSC (AKT shRNA; CHI mice receiving iNSCs pretreated with AKT-specific shRNA) groups on day 7 post-CHI (full-length blots are presented in Additional Fig. 8). (K) Box-whisker plot depicting the relative levels of BDNF/GAPDH in the injured cortices among the three groups on day 7 post-CHI (n = 3/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (L) Representative staining for the BDNF+ (red) depicted BDNF levels in the injured cortices among the three groups on day 7 post-CHI. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. (M) Box-whisker plot depicting the RFI values of BDNF in the injured cortices among the three groups on day 7 post-CHI (n = 6/group; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CHI: closed head injury; ChIP: chromatin immunoprecipitation; CREB: cAMP response element binding protein; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; iNSCs: induced neural stem cells

To determine the expression and localization of p-CREB and BDNF, we conducted immunofluorescence staining and observed that the RFI values of p-CREB and BDNF in iNSCs in the co-culture (AKT shRNA) group were substantially lower than those in the co-culture (Control shRNA) group (P < 0.05; Fig. 6G-I). We deduce from these observations that blockage of AKT could counteract the effects of co-culture with LPS-activated microglia that increased CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV, as well as CREB phosphorylation and BDNF expression in iNSCs.

AKT inhibition in grafted iNSCs reduces BDNF expression in the injured cortices of CHI mice

To further evaluate the regulatory effect of AKT signaling on BDNF expression in grafted iNSCs, we conducted western blot analysis and found that BDNF levels in the injured cortices in the iNSC (AKT shRNA; CHI mice receiving iNSCs pretreated with AKT-specific shRNA) group were significantly higher than those in the PBS (CHI mice receiving PBS) group but substantially lower than those in the iNSC (CHI mice receiving iNSCs pretreated with PBS) group (P < 0.05; Fig. 6J and K).

To determine the expression and localization of BDNF, we utilized immunofluorescence staining and observed that the RFI values of BDNF in the injured cortices in the iNSC (AKT shRNA) group were significantly higher than those in the PBS group but substantially lower than those in the iNSC group (P < 0.05; Fig. 6L and M). These findings indicate that blocking AKT activity in grafted iNSCs could reduce BDNF expression in the injured cortices of CHI mice.

Discussion

BDNF, an evolutionarily conserved neurotrophin, suppresses neuronal apoptosis and enhances neuronal survival—a critical determinant of neurological recovery following CHI [23]. We previously demonstrated that intracerebral-transplanted iNSCs can up-regulate BDNF levels in CHI-damaged brains, which enlarges therapeutic effects of iNSCs on neuronal loss and neurological impairment post-CHI [10]. In this study, we aimed to elucidate the mechanism of BDNF up-regulation in iNSCs. We come to a result that iNSCs, co-cultured with LPS-activated microglia, up-regulated the expression levels of BDNF through AKT-mediated reduction of methyltransferase EZH2 and histone H3K27me3 at Bdnf promoter IV, as well as activation of transcription factor CREB which targets Bdnf promoters I and IV, respectively.

Building on our mechanistic studies of AKT signaling [15], biochemical analyses demonstrate that AKT-mediated phosphorylation of EZH2 at Ser21 specifically ablates its methyltransferase activity. This post-translational modification concurrently diminishes EZH2 occupancy at the Bdnf promoter IV regulatory element. In line with previous studies, the inhibitory effects of AKT activation on EZH2 resulted in a decrease of H3K27 trimethylation at Bdnf promoter IV and derepression of silenced Bdnf exon IV [24]. Moreover, activation of AKT could enhance the transcriptional activity of CREB by phosphorylating CREB, and elevate CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV. Coincide with reported findings, the positive modulatory effects of AKT activation on CREB directly induced an increase of transcription of Bdnf exons I and IV [18]. Furthermore, blockage of AKT in iNSCs could counteract the effects of EZH2 and H3K27me3 reduction, as well as CREB activation on BDNF up-regulation. In agreement with the in vitro experimental results, AKT inhibition blocked the role of grafted iNSCs in elevating BDNF levels in the injured cortices of CHI mice. Collectively, BDNF overexpression in iNSCs attributed to AKT signaling appears to be a complex process, as multiple regulatory mechanisms and responsive promoters are involved.

In recent studies, AKT-mediated EZH2 phosphorylation may contribute to cell survival through derepression of genes silenced by H3K27me3 [25]. Besides, several lncRNAs are found to down-regulate BDNF expression by recruiting EZH2 to Bdnf promoters and aggravate the repressive H3K27me3 epigenetic mark at these promoters [26, 27]. Moreover, a few reports showed that activation of AKT may up-regulate BDNF expression via CREB signaling [18]. Our results are partially consistent with prior findings, and the differences in responsive promoters may be from the multiple regulatory mechanisms involved in BDNF overexpression in iNSCs [7]. Additionally, our novel findings revealed that AKT signaling could play various roles (including derepression and induction) in regulating BDNF expression through different mechanisms at the same Bdnf promoter (IV). For instance, AKT-mediated EZH2 phosphorylation responsible for H3K27me3 reduction disrupted Bdnf gene silencing. On the other hand, AKT-mediated CREB phosphorylation directly led to the induction of Bdnf genes. Notably, our data uncovered that these roles played by ATK signaling could selectively affect specific Bdnf promoters that explained the difference in regulatory mechanisms between responsive promoters I and IV.

Some limitations in our study should be noted. Firstly, why interaction between histone modifications and transcription factor activation may affect the expression levels of BDNF in iNSCs remains unclear. Follow-up researches will determine the effect of their interaction on BDNF expression. Furthermore, whether these regulatory mechanisms are conserved in human and mouse iNSCs awaits elucidated. Subsequent work will focus on the mechanism of BDNF expression in human iNSCs. Additionally, whether other molecules, such as insulin-like growth factor (IGF) secreted by microglia co-cultured with iNSCs, play modulatory roles in BDNF expression in iNSCs is also yet to be discovered, since IGF was reported to reduce H3K27 trimethylation through AKT signaling [28]. Further studies are in need to elucidate the interplay among these molecules associated with the expression of BDNF, to better clarify the neurotrophic effects of iNSCs in response to stimuli.

In conclusion, our study shows that AKT signaling may regulate BDNF expression in iNSCs. Activation of AKT can up-regulate BDNF expression through inactivating EZH2 as well as reducing EZH2 and H3K27me3 levels at Bdnf promoter IV, meanwhile activating CREB as well as increasing CREB levels at Bdnf promoters I and IV. Our results imply a novel role of AKT signaling in the neurotrophic effects of iNSCs and therefore, suggest a potential new approach to up-regulate BDNF expression by modulating the levels of AKT activation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Dr. Hui Yao, Yan Zhang, Cuiying Wu, Kai Sun and Ning Liu (Chinese PLA General Hospital) for helpful advice and technical support. The authors declare that they have not used Artificial Intelligence in this study.

Author contributions

WW and WQ performed co-culture experiments and wrote the manuscript. PC performed loss-of-function study. ZY and MZ performed western blot analysis. YZ performed morphological analysis. LG and DZ performed qRT-PCR assay. RX designed and revised the manuscript. MG conducted cell culture and transplantation experiments and revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Nos. 82271397 (to MG), 82001293 (to MG), 82171355 (to RX), 81971295 (to RX) and 81671189 (to RX) and the Medical Science Research Project Plan of the Hebei Provincial Health Commission, Nos. 20250191 (to MG) and 20251064 (to ZY).

Data availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

(1) Title of the approved project: Effect and mechanism of induced neural stem cell transplantation in the treatment of brain injury; (2) Name of the institutional approval committee: Research Ethics Committee at Chinese PLA General Hospital; (3) The approval number: 2016-40; (4) The approval date: March 16, 2016.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wenjia Wang, Wenqiao Qiu, Pengyu Chen, Zhijun Yang and Mingming Zou contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ruxiang Xu, Email: jzprofxu@126.com.

Mou Gao, Email: gaomou218@126.com.

References

- 1.Maas AIR, Menon DK, Manley GT, Abrams M, Åkerlund C, Andelic N, Aries M, Bashford T, Bell MJ, Bodien YG, Brett BL, Büki A, Chesnut RM, Citerio G, Clark D, Clasby B, Cooper DJ, Czeiter E, Czosnyka M, Dams, Connor K, et al. Traumatic brain injury: progress and challenges in prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(11):1004–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Bielefeld P, Martirosyan A, Martín-Suárez S, Apresyan A, Meerhoff GF, Pestana F, Poovathingal S, Reijner N, Koning W, Clement RA, Van der Veen I, Toledo EM, Polzer O, Durá I, Hovhannisyan S, Nilges BS, Bogdoll A, Kashikar ND, Lucassen PJ, Belgard TG, et al. Traumatic brain injury promotes neurogenesis at the cost of astrogliogenesis in the adult hippocampus of male mice. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindhout FW, Krienen FM, Pollard KS, Lancaster MA. A molecular and cellular perspective on human brain evolution and tempo. Nature. 2024;630(8017):596–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaker Z, Segalada C, Kretz JA, Acar IE, Delgado AC, Crotet V, Moor AE, Doetsch F. Pregnancy-responsive pools of adult neural stem cells for transient neurogenesis in mothers. Science. 2023;382(6673):958–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyart C, Carbo-Tano M, Cantaut-Belarif Y, Orts-Del’Immagine A, Böhm UL. Cerebrospinal fluid-contacting neurons: multimodal cells with diverse roles in the CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2023;24(9):540–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toparlak ÖD, Zasso J, Bridi S, Serra MD, Macchi P, Conti L, Baudet ML, Mansy SS. Artificial cells drive neural differentiation. Sci Adv. 2020;6(38):eabb4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang CS, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. BDNF signaling in context: from synaptic regulation to psychiatric disorders. Cell. 2022;185(1):62–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Yang Y, Liu J, Qian L. Direct cell reprogramming: approaches, mechanisms and progress. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(6):410–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao H, Gao M, Ma J, Zhang M, Li S, Wu B, Nie X, Jiao J, Zhao H, Wang S, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Wicha MS, Chang AE, Gao S, Li Q, Xu R. Transdifferentiation-induced neural stem cells promote recovery of middle cerebral artery stroke rats. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0137211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao M, Yao H, Dong Q, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Yang Z, Xu M, Xu R. Neurotrophy and immunomodulation of induced neural stem cell grafts in a mouse model of closed head injury. Stem Cell Res. 2017;23(1):132–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Zhao Q, Wei W, Lin Q, Magnan C, Emami MR, Wearick-Silva LE, Viola TW, Marshall PR, Yin J, Madugalle SU, Wang Z, Nainar S, Vågbø CB, Leighton LJ, Zajaczkowski EL, Ke K, Grassi-Oliveira R, Bjørås M, Baldi PF, et al. The DNA modification N6-methyl-2’-deoxyadenosine (m6dA) drives activity-induced gene expression and is required for fear extinction. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(4):534–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koo JW, Mazei-Robison MS, LaPlant Q, Egervari G, Braunscheidel KM, Adank DN, Ferguson D, Feng J, Sun H, Scobie KN, Damez-Werno DM, Ribeiro E, Peña CJ, Walker D, Bagot RC, Cahill ME, Anderson SAR, Labonté B, Hodes GE, Browne H, et al. Epigenetic basis of opiate suppression of Bdnf gene expression in the ventral tegmental area. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(3):415–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinowich K, Hattori D, Wu H, Fouse S, He F, Hu Y, Fan G, Sun YE. DNA methylation-related chromatin remodeling in activity-dependent BDNF gene regulation. Science. 2003;302(5646):890–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao W, Cao Q, Luo S, He L, Yang C, Chen J, Qi Q, Hashimoto K, Zhang JC. Microglial ERK-NRBP1-CREB-BDNF signaling in sustained antidepressant actions of (R)-ketamine. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(3):1618–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao M, Dong Q, Zou D, Yang Z, Guo L, Xu R. Induced neural stem cells regulate microglial activation through Akt-mediated upregulation of CXCR4 and Crry in a mouse model of closed head injury. Neural Regen Res. 2025;20(5):1416–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li C, Meng F, Lei Y, Liu J, Liu J, Zhang J, Liu F, Liu C, Guo M, Lu XY. Leptin regulates exon-specific transcription of the Bdnf gene via epigenetic modifications mediated by an AKT/p300 HAT cascade. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(8):3701–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jian WX, Zhang Z, Zhan JH, Chu SF, Peng Y, Zhao M, Wang Q, Chen NH. Donepezil attenuates vascular dementia in rats through increasing BDNF induced by reducing HDAC6 nuclear translocation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41(5):588–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarneshan SN, Fakhri S, Khan H. Targeting akt/creb/bdnf signaling pathway by ginsenosides in neurodegenerative diseases: a mechanistic approach. Pharmacol Res. 2022;177(1):106099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flierl MA, Stahel PF, Beauchamp KM, Morgan SJ, Smith WR, Shohami E. Mouse closed head injury model induced by a weight-drop device. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(9):1328–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao M, Dong Q, Wang W, Yang Z, Guo L, Lu Y, Ding B, Chen L, Zhang J, Xu R. Induced neural stem cell grafts exert neuroprotection through an interaction between Crry and Akt in a mouse model of closed head injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stragier E, Massart R, Salery M, Hamon M, Geny D, Martin V, Boulle F, Lanfumey L. Ethanol-induced epigenetic regulations at the Bdnf gene in C57BL/6J mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(3):405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsankova NM, Berton O, Renthal W, Kumar A, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(4):519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagahara AH, Tuszynski MH. Potential therapeutic uses of BDNF in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(3):209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cha TL, Zhou BP, Xia W, Wu Y, Yang CC, Chen CT, Ping B, Otte AP, Hung MC. Akt-mediated phosphorylation of EZH2 suppresses methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3. Science. 2005;310(5746):306–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiao L, Liu X. Structural basis of histone H3K27 trimethylation by an active polycomb repressive complex 2. Sci. 2015;350(6258):aac4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Bohnsack JP, Teppen T, Kyzar EJ, Dzitoyeva S, Pandey SC. The LncRNA BDNF-AS is an epigenetic regulator in the human amygdala in early onset alcohol use disorders. Transl Psychiat. 2019;9(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su H, Liu B, Chen H, Zhang T, Huang T, Liu Y, Wang C, Ma Q, Wang Q, Lv Z, Wang R. LncRNA ANRIL mediates endothelial dysfunction through BDNF downregulation in chronic kidney disease. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(7):661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu D, Yan Y, Wei T, Ye Z, Xiao Y, Pan Y, Orme JJ, Wang D, Wang L, Ren S, Huang H. An acetyl-histone vulnerability in PI3K/AKT inhibition-resistant cancers is targetable by both BET and HDAC inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2021;34(7):108744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiao L, Liu X. Structural basis of histone H3K27 trimethylation by an active polycomb repressive complex 2. Science. 2015;350(6258):aac4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Additional files.