Abstract

Background

Osteonecrosis, or avascular necrosis (AVN), is a degenerative bone disorder caused by insufficient blood supply, primarily affecting weight-bearing joints. With increasing reliance on platforms like YouTube for health information, evaluating the quality of content related to AVN is crucial to prevent misinformation. This study aims to assess the quality and educational value of YouTube videos on AVN.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted on November 17, 2024, using the terms “avascular necrosis” and “osteonecrosis.” From an initial pool of 143,000 videos, 70 relevant videos were selected based on specific inclusion criteria. Two orthopedic surgeons independently reviewed these videos, assessing various characteristics and categorizing them by content and the uploader’s background. The quality was evaluated using the DISCERN score, JAMA criteria, and Video Power Index (VPI). Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC), which yielded a value of 0.903 (95% CI: 0.856 to 0.937), indicating nearly perfect agreement among reviewers.

Results

The mean video length was 11.6 ± 16.5 min, with a total view count averaging 23,087 ± 46,868. The mean DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS scores were 45.7 ± 13.9, 2.6 ± 0.7, and 3.0 ± 0.9, respectively. Videos uploaded by doctors had slightly higher quality scores, but overall, many videos were rated as average or poor. A significant positive correlation was found between the VPI and quality scores (p < 0.05), while older videos tended to have lower quality scores.

Conclusions

Health-related videos on platforms like YouTube frequently do not meet high-quality standards, despite some differences in assessments. This emphasizes the need for better quality control and standardization in health content production. Collaboration among medical professionals, content creators, and platforms can significantly enhance online health education quality.

Keywords: YouTube, Osteonecrosis, Avascular necrosis, Online health education, Medical information reliability, DISCERN, JAMA, GQS

Introduction

AVN is a degenerative disorder marked by bone tissue death resulting from an insufficient blood supply. This illness predominantly impacts weight-bearing joints, including the hip, knee, and shoulder, resulting in joint discomfort and the potential deterioration of bone structure [1]. The etiology of osteonecrosis is multifaceted, including both traumatic and non-traumatic factors. Traumatic causes encompass fractures and dislocations that impede blood circulation to the bone, while non-traumatic factors comprise prolonged corticosteroid administration, excessive alcohol intake, sickle cell disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus [2, 3].

Recent studies have further illuminated the multifactorial nature of AVN, particularly regarding non-traumatic factors such as steroid and alcohol exposure. Research has shown that non-traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head induced by these exposures is associated with alterations in intestinal flora and metabolomic profiles, suggesting that these factors may contribute to the disease’s pathogenesis. Understanding these associations is vital for developing targeted prevention and treatment strategies [4].

The etiology of AVN is intricate, with recent investigations examining the relationships among various biological factors. A multivariate logistic regression analysis has revealed significant associations between lipid metabolism, coagulation, and other blood indices with the etiology and staging of non-traumatic femoral head necrosis, highlighting the importance of understanding these biochemical relationships to better inform treatment strategies and enhance patient outcomes [5].

A comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing the progression and treatment of AVN is essential for effective management. Prognostic factors significantly impact the outcomes for patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head, guiding treatment decisions and overall management strategies [6].

Avascular necrosis of the femoral head represents a serious condition that can result in joint pain, restricted mobility, and eventual hip joint collapse if not managed properly. This condition presents unique challenges, particularly in skeletally immature patients, where treatment options must be carefully evaluated to prevent long-term complications. A systematic review highlights that operative management strategies for avascular necrosis in skeletally immature patients can be effective but necessitate a tailored approach based on individual patient factors, emphasizing the need for specialized treatment protocols to optimize outcomes in this vulnerable population [7].

Treatment options vary, ranging from conservative management to surgical interventions. Among these, osteotomies have been recognized as an effective surgical approach for managing avascular necrosis of the femoral head, particularly in the early stages of the disease, highlighting the importance of timely diagnosis and intervention to enhance patient outcomes [8].

Core decompression has emerged as a notable joint-preserving technique, demonstrating promise in the management of femoral head osteonecrosis. A study indicates that core decompression, whether performed alone or in combination with bone marrow-derived cell therapies, shows potential in managing femoral head osteonecrosis, emphasizing the need for innovative treatment strategies to improve patient outcomes through timely intervention [9].

A meta-analysis further reveals that core decompression is effective compared to other joint-preserving treatments for osteonecrosis of the femoral head, underscoring the significance of selecting appropriate interventions to optimize patient outcomes [10].

Recent literature emphasizes the importance of hip-preserving treatments for early osteonecrosis, with a growing body of research focused on their efficacy. A systematic bibliometric analysis provides valuable insights into the trends and outcomes associated with these treatments, indicating that key developments in the field have emerged from 2010 to 2023, underscoring the necessity for continued research and innovation in treatment strategies to improve patient outcomes [11].

Finally, the investigation of genetic predispositions related to osteonecrosis has gained traction. A case-control study explores the relationship between polymorphisms in the ESR1 and APOE genes and the risk of developing osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Findings suggest that specific gene polymorphisms may significantly correlate with the risk of osteonecrosis, emphasizing the importance of genetic factors in the etiology of this condition. Understanding these correlations can assist in identifying at-risk populations and tailoring preventive strategies [12].

These days, more and more people are using websites like YouTube for health education and searching. The accessibility of medical data on these platforms is easy, but the reliability and trustworthiness of the information are poor [13]. The need to assess the reliability of these sources is highlighted by the fact that users may make uninformed health decisions due to misinformation spread on these platforms [2]. There are scientific videos on orthopedic conditions such as carpal tunnel syndrome [13], anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries, hallux valgus [14], and hip arthroscopy [15] on YouTube. Unfortunately, there is a lack of studies analyzing the scientific reliability of videos on avascular necrosis of the femoral head, and similarly, evaluations of the quality of YouTube content related to osteonecrosis are quite limited.

Because of the abundance of user-generated content on YouTube, it is crucial to evaluate osteonecrosis films for accuracy and usefulness to provide patients with the information they need. Examining the content quality, correctness, and instructional value of seventy YouTube videos titled “Osteonecrosis” or “Avascular Necrosis” is the goal of this study. Through an analysis of these videos’ pros and cons, the research aims to shed light on the present situation of osteonecrosis video resources online and provide suggestions for how content providers and consumers can improve the spread of trustworthy health information.

This study is the first to evaluate the quality of videos related to osteonecrosis on YouTube using multiple tools such as DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS [16–18].

Materials and methods

A systematic search was conducted using the Google search engine on November 17, 2024 to identify relevant YouTube videos related to AVN or osteonecrosis. The search terms used were “avascular necrosis” or “osteonecrosis” within the YouTube platform. The initial search yielded 143,000 videos. To ensure relevance and quality, videos were excluded if they were not in English, appeared multiple times, had a duration of less than 60 seconds (the risk of superficial information in short videos), or contained advertising content (risk of commercial conflict of interest). After applying these criteria, the 70 most-watched videos were selected for further analysis.

Videos were categorized based on their content and the professional background of the uploader. The classification of video content included comprehensive information about AVN, general definitions incorporating radiological and histological perspectives, surgical and non-surgical treatment methods, pediatric cases, and different types of AVN. In addition, the sources of the videos were categorized into different groups, including physicians, audiologists, physiotherapists, health-related YouTube channels, hospital-affiliated YouTube channels, and other media or educational material sources.

To assess the quality and reliability of the content, each video was evaluated using three validated scoring systems. The DISCERN score was used to measure the quality of consumer health information, while the JAMA benchmark criteria were applied to assess medical information quality based on authorship, attribution, currency, and disclosure. Additionally, the VPI was used to evaluate the popularity and engagement of the videos based on metrics such as likes and dislikes count [18].

|

The evaluations were conducted independently by two orthopedic and traumatology specialists to ensure consistency and reliability. Any discrepancies in the assessment were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

To assess inter-rater reliability, we calculated the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for the DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS scores across the 70 videos. The ICC value of 0.903 (95% CI: 0.856 to 0.937) reflects nearly perfect agreement between the two orthopedic surgeons, indicating that the scoring system was consistently applied.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 26.0. Continuous variables’ normal distribution was checked with graphical methods (Q-Q Plot) and normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) tests. Since there was no ‘’Normal Distribution’’ status in all variables, the ‘’Mann-Whitney U’’ test was used in comparing independent groups. Box Plot was shaped with a graphic type. Descriptive statistics were presented with median and minimum, and maximum values. Categorical variables were presented with numbers and percentages. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated to evaluate the consistency between DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS measurements. The interaction between YouTube video parameters was examined with the Pearson correlation method. The statistical significance level was accepted as p < 0.05 for all tests.

The mean ± standard deviation video length was 11.6 ± 16.5 min. The broadcast duration was found to be 4.1 ± 2.6, 49 ± 31.7, and 1491 ± 965 on a year, month, and day basis, respectively.

The mean VPI was 98.03 ± 1.58. Other video characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics and descriptive statistics of Youtube videos related to avascular necrosis

| Mean ± SD | Median (Min-Max) | |

|---|---|---|

| Video Length (min) | 11.6 ± 16.5 | 6 (2–92) |

| Broadcast duration (years) | 4.1 ± 2.6 | 4 (0–13) |

| Broadcast duration (months) | 49 ± 31.7 | 48 (2-156) |

| Broadcast duration (days) | 1491 ± 965 | 1463 (64-4762) |

| Total views | 23,087 ± 46,868 | 4139 (571-246403) |

| Daily average views | 41.46 ± 181 | 4 (1-1475) |

| Total Like | 1076 ± 3743 | 68 (10-21000) |

| Monthly average likes | 69.04 ± 324.05 | 1.74 (0.22-2187.13) |

| Total Dislike | 8 ± 18 | 1 (0-105) |

| VPI | 98.03 ± 1.58 | 97.87 (93.94–100.) |

| Comments | 54.86 ± 190.45 | 6.5 (0-1520) |

| Yearly average comments | 31.8 ± 168.19 | 1.84 (0-1401.97) |

| DISCERN | 45.7 ± 13.9 | 45.5 (19.0-71.5) |

| JAMA | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) |

| GQS | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.0 (1.5–5.0) |

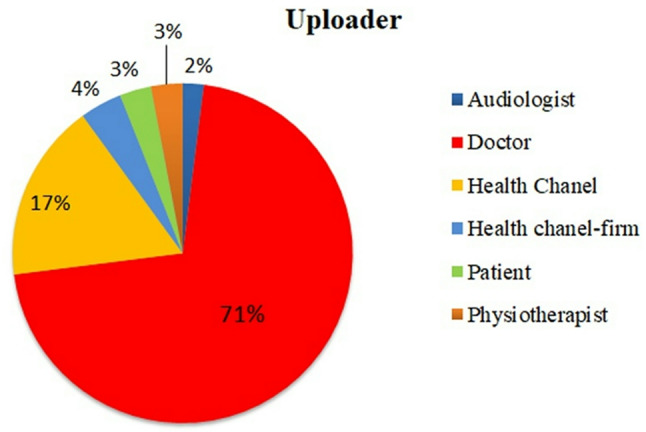

Video uploaders consist of 50 doctors, 12 health channels, 3 health firms, 2 physiotherapists, 2 patients, and 1 audiologist. (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Distribution of video uploaders among the analyzed youtube videos

Of the 70 videos, nearly half (45.7%) had general content that dealt with topics such as the description of AVN, epidemiology, and treatment. A fraction had non-surgical content (18.6%), and even fewer presented surgical topics (12.9%). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Distribution of video content type and animation usage

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Contents | ||

| General | 32 | 45.7% |

| No surgery | 13 | 18.6% |

| General Treatment | 9 | 12.9% |

| General-Diagnosis | 4 | 5.7% |

| General-Rad | 4 | 5.7% |

| Surgery | 4 | 5.7% |

| Patient experience | 3 | 4.3% |

| Histology | 1 | 1.4% |

| Animation | ||

| Yes | 13 | 18.6% |

| No | 57 | 81.4% |

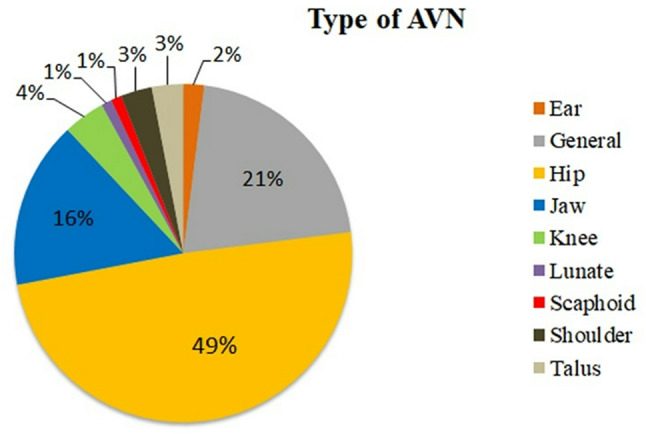

The most common AVN type presented was Hip 34 (48.6%), followed by Jaw 11 (15.7%), Knee 3 (4.3%), Shoulder 2 (2.9%), Talus 2 (2.9%), Ear 1 (1.4%), Lunate 1 (1.4%) and Scaphoid 1 (1.4%). (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Frequency of different types of avascular necrosis covered in youtube videos

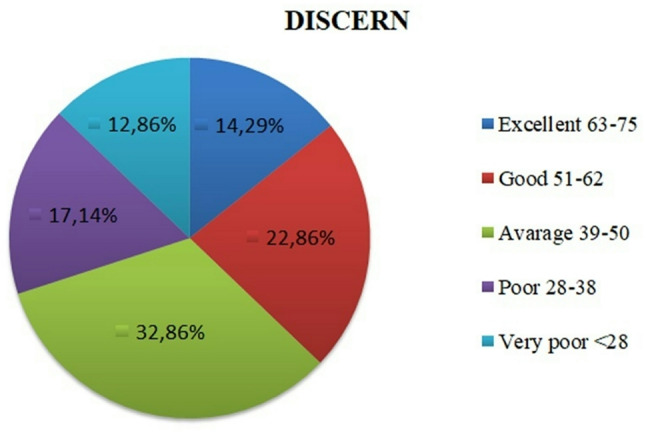

DISCERN score was 14,3% (n:10) excellent, 22,9% (n:16)good, 32,9% (n:23)average, 17,1% (n:12)poor, and 12,9% (n:9) very poor (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of DISCERN quality scores among analyzed youtube videos

Correlation analysis

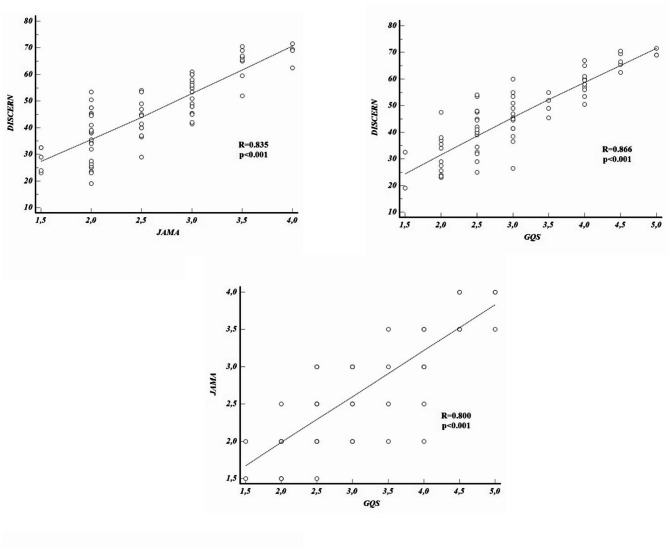

The observers’ DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS scores, and the compatibility of the evaluations made with these three measurement models were investigated with the Intraclass Correlations method. The ICC was found to show early perfect agreement (0.903 (0.856 to 0.937)). Pearson correlation analysis was performed to see the relationship between continuous variables. The correlation between DISCERN and JAMA was r = 0.835, p < 0.001, the correlation between DISCERN and GQS was r = 0.866, p < 0.001, and the correlation between JAMA and GQS was r = 0.800, p < 0.001, all highly positively related.

A negative low-level relationship was found between the broadcast time of the video and DISCERN, r=-0.254, p = 0.034, and a positive moderate relationship was found between VPI and DISCERN, r = 0.335, p = 0.005. There was no significant correlation between continuous variables in all other matches (Table 3; Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Correlation analysis between video parameters and quality scores (DISCERN, JAMA, GQS)

| DISCERN | JAMA | GQS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | R | p | R | p | |

| Video Length (min) | 0.153 | 0.206 | 0.222 | 0.064 | 0.079 | 0.515 |

| Broadcast duration (years) | -0.254 | 0.034 | -0.070 | 0.565 | -0.208 | 0.085 |

| Broadcast duration (months) | -0.254 | 0.034 | -0.070 | 0.565 | -0.208 | 0.085 |

| Broadcast duration (days) | -0.254 | 0.034 | -0.070 | 0.565 | -0.208 | 0.085 |

| Total views | 0.070 | 0.563 | 0.163 | 0.177 | 0.109 | 0.370 |

| Daily average views | -0.037 | 0.761 | 0.005 | 0.965 | -0.035 | 0.773 |

| Total Like | 0.071 | 0.558 | 0.092 | 0.449 | 0.141 | 0.246 |

| Monthly average likes | -0.052 | 0.671 | -0.044 | 0.717 | -0.022 | 0.856 |

| Total Dislike | -0.054 | 0.656 | 0.005 | 0.968 | 0.014 | 0.910 |

| VPI | 0.335 | 0.005 | 0.233 | 0.052 | 0.293 | 0.014 |

| Comments | -0.040 | 0.742 | -0.061 | 0.616 | 0.039 | 0.748 |

| Yearly average comments | -0.058 | 0.631 | -0.097 | 0.425 | 0.007 | 0.953 |

| DISCERN | — | — | 0.835 | < 0.001 | 0.866 | < 0.001 |

| JAMA | 0.835 | < 0.001 | — | — | 0.800 | < 0.001 |

| GQS | 0.866 | < 0.001 | 0.800 | < 0.001 | — | — |

r = Correlation coefficient

Fig. 4.

Correlation between various video parameters and quality assessment scores

The DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS scores were compared between the videos with and without animation. DISCERN score was found to be statistically significant as 61.0 (40.0-70.5) in the group with animation and 44.5 (19.0-71.5) in the group without animation, p < 0.001. The DISCERN score was higher in the group with animation. JAMA score was found to be 3.5 (2.0–4.0) higher in the group with animation and 2.5 (1.5-4.0) higher in the group without animation; the difference was statistically significant, p < 0.001. GQS score was also statistically significantly higher in the group with animation, p < 0.001. GQS median values, respectively; The group with animation content was 4.0 (2.5-5.0), and the group without animation content was 2.5 (1.5-5.0).

Video length assessment was performed by dividing into two groups as shorter than 5 min, n = 35 (50%), and longer than 5 min, n = 35 (50%). The median JAMA score in the > 5 min group was 3.0 (1.5-4.0) and in the ≤ 5 min group it was 2.5 (1.5–3.5); the > 5 min group JAMA score was found to be higher, p = 0.025. There was no significant difference between the groups in DISCERN and GQS scores, p > 0.005.

VPI assessment was performed by dividing into two groups: VPI > 98 n = 33 (47%) and VPI ≤ 98 n = 37 (53%). The DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS scores of the VPI > 98 group were found to be statistically significantly higher. Respectively, DISCERN score median values 49.0 (19.0-71.5) and 42.0 (23.0-70.5), p = 0.011. JAMA score median value 3.0 (1.5-4.0) and 2.5 (1.5–3.5), p = 0.039. GQS median values 3.0 (1.5-5.0) and 2.5 (1.5–4.5), p = 0.023. There was no statistically significant difference between DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS scores among the groups in other parameters examined. These parameters were as follows; Uploader (Doctor vs. Other), Video Period (New videos vs. Old videos), Daily average views (Daily view count > 10 vs. Daily view count < 10), Yearly average comments (Comment/Year > 10 vs. Comment/Year ≤ 10), Comments (Yes vs. No). (Table 4)

Table 4.

Relationship between categorical variables and video quality scores (DISCERN, JAMA, GQS)

| DISCERN | JAMA | GQS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Med… (Min.-Max.) | P * | Med. (Min.-Max.) | P * | Med. (Min.-Max.) | P* | |

| Uploader | |||||||

| Doctor | 50 | 46.3 (23.0-71.5) | 0.495 | 2.5 (1.5-4.0) | 0.867 | 3.0 (1.5-5.0) | 0.746 |

| Other | 20 | 40.0 (19.0-70.5) | 2.5 (1.5-4.0) | 3.0 (1.5-5.0) | |||

| Video Period | |||||||

| New videos (< 5 years) | 52 | 47.5 (23-69.5) | 0.093 | 2.5 (1.5-4.0) | 0.387 | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 0.163 |

| Old videos (> 5 years) | 18 | 38.5 (19-71.5) | 2.3 (1.5-4.0) | 2.5 (1.5-5.0) | |||

| Daily average views | |||||||

| Daily view count > 10 | 18 | 50.0 (23.5–70.5) | 0.320 | 2.8 (1.5-4.0) | 0.262 | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 0.298 |

| Daily view count < 10 | 52 | 45.3 (19.0-71.5) | 2.5 (1.5-4.0) | 3.0 (1.5-5.0) | |||

| Video Length (min) | |||||||

| Video length > 5 | 35 | 49.0 (19.0-71.5) | 0.081 | 3.0 (1.5-4.0) | 0.025 | 3.0 (1.5-5.0) | 0.163 |

| Video length ≤ 5 | 35 | 45.0 (23.0-70.5) | 2.5 (1.5–3.5) | 2.5 (1.5–4.5) | |||

| Animation | |||||||

| Yes | 13 | 61.0 (40.0-70.5) | < 0.001 | 3.5 (2.0–4.0) | < 0.001 | 4.0 (2.5-5) | < 0.001 |

| No | 57 | 44.5 (19.0-71.5) | 2.5 (1.5-4.0) | 2.5 (1.5-5) | |||

| VPI | |||||||

| VPI > 98 | 33 | 49.0 (19.0-71.5) | 0.011 | 3.0 (1.5-4.0) | 0.039 | 3.0 (1.5-5.0) | 0.023 |

| VPI ≤ 98 | 37 | 42.0 (23.0-70.5) | 2.5 (1.5–3.5) | 2.5 (1.5–4.5) | |||

| Yearly average comments | |||||||

| Comment/Year >10 | 19 | 52.0 (25.0-69.5) | 0.242 | 3.0 (1.5-4.0) | 0.196 | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 0.197 |

| Comment/Year ≤ 10 | 51 | 45.0 (19.0-71.5) | 2.5 (1.5-4.0) | 3.0 (1.5-5.0) | |||

| Comments | |||||||

| Yes | 60 | 45.3 (19.0-71.5) | 0.718 | 2.5 (1.5-4.0) | 0.213 | 3.0 (1.5-5.0) | 0.891 |

| No | 10 | 46.5 (23.5–65.0) | 2.0 (2.0-3.5) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) |

*Mann-Whitney Test, Med = Median

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the content quality of YouTube videos titled “Osteonecrosis” or dealing with the topics of “Avascular Necrosis”, using well-established tools such as DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS. In total, 70 videos met the inclusion criteria for the analysis. The results demonstrate considerable variability in video quality, content, and video uploaders.

The DISCERN scores ranged from 19.0 to 71.5, with a mean score of 45.7 (± 13.9), indicating that many of the videos failed to meet optimal standards for health information dissemination. These findings are consistent with those of previous similar studies that evaluated the quality of YouTube videos on orthopedic health-related topics, often reporting a wide range of quality scores [19–22].

The substantial standard deviations in the quality scores (e.g., DISCERN: 45.7 ± 13.9) suggest a wide range of content quality among the analyzed videos. This variability could be attributed to factors such as the uploader’s expertise, the depth of information provided, and the presentation style. For instance, videos created by healthcare professionals may offer more accurate and reliable information than those produced by non-experts. Understanding this variability is essential for viewers who rely on these videos for health-related information, as it emphasizes the importance of critically evaluating the source and content of the videos.

One potential explanation for this subpar outcome is that only 3% of the identified videos were academic. Consequently, we recommend expanding academic content production beyond conferences and encouraging researchers to publish evidence-based videos on platforms like YouTube.This would guarantee that patients were given information that was both safer and of higher quality.

The JAMA score, with a mean of 2.6 ± 0.7, suggests that while most videos provided basic information, they often lacked adequate references, authorship, and disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Video length was shown to be strongly connected with DISCERN, JAMA score, and their scoring system, the RCSS (rotator cuff score) [21, 23]. Additionally, showing a positive association with video length in JAMA, DISCERN, and GQS [24]. In line with the literature, this study demonstrated a favorable correlation between JAMA score, GQS, DISCERN, and video length. Furthermore, the fact that these videos have been on YouTube for less time than others may explain the negative correlation between their view counts and quality. Moreover, an increase in the like rate corresponds with video quality. Our analysis revealed that the quality ratings from any scoring systems—DISCERN, JAMA, or GQS— did not correlate with the duration of the videos. It appears that while lengthier videos may give more substance, they do not necessarily translate into higher quality, showing that the clarity, relevance, and evidence-based nature of the content are substantially more critical than duration. According to Osman et al., health-related content on YouTube is of average to below-average quality [25]. Consequently, it is not a reliable source of any medical or health-related information.

Videos produced by health professionals, particularly doctors, had a slightly higher average quality, but they still did not meet optimal standards across all evaluation tools. The majority of videos (71.4%) were uploaded by doctors, which highlights the potential for medical professionals to improve the reliability of health-related content on YouTube. However, other categories, such as health channels (17.1%) and health firms (4.3%), also contributed to the mix. The content of the videos also varied widely. Most of the videos were categorized as general (45.7%), while a smaller proportion focused on specific aspects of AVN, such as hip (48.6%) and jaw (15.7%) osteonecrosis. Interestingly, videos related to specific types of AVN, like the jaw or hip, seemed to have higher viewer engagement based on the number of likes and comments. This suggests that videos focusing on well-known or common forms of AVN may generate more interest and, potentially, more educational value. The literature in other medical topics found that there is no significant disparity in views and popularity between informative and potentially deceptive videos. Individuals seeking trustworthy information should favor videos produced by medical specialists. Prioritizing the qualifications of the content creator over the video’s popularity or view count is essential for obtaining accurate and reliable information [26].

Engagement metrics, such as total views, likes, and comments, were also considered. The average total views were 23,087 (± 46,868), with a median of 4,139, indicating that while some videos garnered substantial attention, others had limited reach. The daily average views (41.46 ± 181) were highly variable, and videos with a higher number of views generally had higher levels of interactivity, as evidenced by more likes (1076 ± 3743) and comments (54.86 ± 190.45). However, despite the potential for large reach, many videos did not achieve a high level of viewer interaction, with the median number of likes being just 68. These results underline the challenge of creating engaging and educational content that resonates with a wide audience. Furthermore, the use of animations in 18.6% of videos could be seen as a strategy to improve viewer engagement. Animation has been shown to enhance understanding in medical education, but the benefits of animations may also vary according to learner characteristics such as prior knowledge and spatial ability [27], and this could explain why these videos attracted more attention. However, despite their visual appeal, the quality of content still remained variable, with many of these videos failing to meet the necessary standards of accuracy and comprehensiveness.

As our study evaluates the quality of 70 health-related videos focused on AVN uploaded by diverse sources, including doctors, health channels, physiotherapists, and patients. The videos were assessed using established scoring systems (DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS) to gauge their accuracy, clarity, and reliability. A key finding was that the quality of the videos varied considerably, with most falling into the “average” and “poor” categories. This section compares our findings with similar studies on the quality of health-related videos, highlighting areas of consistency and discrepancy. There are several studies have examined the reliability and accuracy of health-related videos on platforms like YouTube within the field of orthopedics. For instance, a study by Abed et al. (2023) evaluated the content and quality of YouTube videos concerning patellar dislocations. The findings indicated that the overall transparency, reliability, and content quality of these videos were poor, highlighting the need for healthcare professionals to guide patients toward reliable sources [28].

Similarly, another study by Cole et al. (2022) assessed the quality of YouTube videos related to ACL injuries. The study found that videos produced by physicians had significantly higher JAMA and GQS scores compared to those created by non-physicians, indicating better quality and educational content [29].

Furthermore, a study by Cengiz et al.(2024) analyzed YouTube videos on frozen shoulder using the DISCERN and JAMA scoring systems. The results showed that videos were mostly rated poorly in quality, and no significant differences were found between videos uploaded by physicians and non-physicians [30]. However, in this study, there is no significant differences were found between videos uploaded by physicians and non-physicians. This discrepancy may be due to variations in the complexity of the topics, the target audience, or the criteria used for video assessment.

There is an inverse relationship between the video upload date and the quality score. Older videos scored lower, and newer videos performed better in terms of quality.A systematic review done by Madathil et al. (2015) analyzed the quality and reliability of health-related YouTube videos across various medical conditions, and it found that many videos contained misleading or inaccurate information which uploaded by non-professional users. However, the study also noted that more recent videos tended to have higher quality scores, suggesting an improvement in the accuracy and reliability of health-related content over time [31].

Our study found a very strong correlation between the scores from different quality assessment tools (DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS). This finding suggests that these scoring systems are in strong agreement when assessing the quality of health-related videos. It also supports the reliability of these tools in evaluating online health content. In a study by Cengiz et al. (2024), the quality of YouTube videos on frozen shoulder was evaluated using DISCERN and JAMA scoring systems. The authors found that both tools showed consistent results, with a strong correlation between DISCERN and JAMA scores (r = 0.845, p < 0.001) [30]. Similarly, Cole et al. (2022) assessed YouTube videos related to ACL injuries and found significant correlations between JAMA and GQS scores (r = 0.753, p < 0.001), highlighting the reliability of these tools for evaluating online health information in orthopedics [29]. Another study by Abed et al. (2023) evaluated YouTube videos on patellar dislocations, finding strong correlations between DISCERN and GQS scores (r = 0.796, p < 0.001), further supporting the consistency of these assessment tools [28].

Practical implications and recommendations

This study highlights the significant variability in the quality of YouTube videos on osteonecrosis and avascular necrosis, with many lacking accuracy and comprehensive information. Healthcare professionals and educators should critically evaluate such online resources before recommending them to patients. It is essential to promote higher-quality educational content on these platforms, encouraging collaboration with medical institutions to ensure evidence-based information is accessible.

Furthermore, findings are limited to English-language content, preventing global generalizations. Multilingual content analysis to identify cultural disparities in AVN education.

Viewers should be cautioned about the risks of relying solely on videos for medical information. Future research should focus on improving video quality and promoting standards for health-related content online.

Using AI-powered tools to dynamically flag misinformation on YouTube (for example, NLP models trained on clinical guidelines).

Conclusion

In conclusion, while there are some differences between our study and similar research in terms of video quality assessment, the general trend remains consistent: health-related videos on platforms like YouTube often fail to meet high-quality standards. This highlights the need for better quality control and standardization in the production of health content. By fostering collaboration among medical professionals, content creators, and platforms, it is possible to significantly improve the quality of online health education.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to Op. Dr. Ali Boz, who has experience in checking scientific manuscripts.

Abbreviations

- ACL

Anterior cruciate ligament

- AVN

Avascular Necrosis

- ICC

Intraclass correlation coefficients

- GQS

Global Quality Scale

- JAMA

Journal of the American Medical Association

- VPI

Video Power Index

Author contributions

JMA [1]: conceptualized the idea, study design, data collection, evaluation of DISCERN, JAMA, GQS, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafted the first manuscript, critical review of the final manuscript.KG [2]: conceptualized the idea, data collection, evaluation of DISCERN, JAMA, and GQS critical review of the final manuscript.NSH [3]: data review and analysis, provided critical supervision during the writing of the manuscript, and critical review of the final draft.

Funding

The authors received no financial support.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study complied with BMC’s ethical standards for publicly available data. No participant consent was required as per institutional guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Petek D, Hannouche D, Suva D. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: pathophysiology and current concepts of treatment. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4(3):85–97. 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassidy JT, Fitzgerald E, Cassidy ES, Cleary M, Byrne DP, Devitt BM, et al. YouTube provides poor information regarding anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(3):840–5. 10.1007/s00167-017-4514-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMahon KM, Schwartz J, Nilles-Melchert T, Ray K, Eaton V, Chakkalakal D. YouTube and the Achilles tendon: an analysis of internet information reliability and content quality. Cureus. 2022;14(4):e23984. 10.7759/cureus.23984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng Q-Y, Tao Y, Geng L, Ren P, Ni M, Zhang G-Q. Non-traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head induced by steroid and alcohol exposure is associated with intestinal flora alterations and metabolomic profiles. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2024;10.1186/s13018-024-04713-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Yu X, Dou S, Lu L, Wang M, Li Z, Wang D. Relationship between lipid metabolism, coagulation and other blood indices and etiology and staging of non-traumatic femoral head necrosis: a multivariate logistic regression-based analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024. 10.1186/s13018-024-04715-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Baroncini A, Eschweiler J, Tingart M, Betsch M. Prognostic factors in the management of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: A systematic review. Surg. 2021. 10.1016/j.surge.2021.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Migliorini F, La Padula G, Oliva F, Torsiello E, Hildebrand F, Maffulli N. Operative Management of Avascular Necrosis of the Femoral Head in Skeletally Immature Patients: A Systematic Review. Life. 2022;10.3390/life12020179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Quaranta M, Miranda L, Oliva F, Aletto C, Maffulli N. Osteotomies for avascular necrosis of the femoral head. BMB. 2021. 10.1093/bmb/ldaa044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Eschweiler J, Tingart M, Baroncini A. Core decompression isolated or combined with bone marrow-derived cell therapies for femoral head osteonecrosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2021. 10.1080/14712598.2021.1862790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadile F, Bernasconi A, Russo S, Maffulli N. Core decompression versus other joint preserving treatments for osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a meta-analysis. BMB. 2016. 10.1093/bmb/ldw010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu T, Jiang Y, Tian H, Shi W, Wang Y, Li T. Systematic analysis of hip-preserving treatment for early osteonecrosis of the femoral head from the perspective of bibliometrics (2010–2023). BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2023;10.1186/s13018-023-04435-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Wang Y, Ma X, Guo J, Li Y, Xiong Y. Correlation between ESR1 and APOE gene polymorphisms and risk of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a case-control study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023. 10.1186/s13018-023-04447-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goyal R, Mercado AE, Ring D, Crijns TJ. Most YouTube videos about carpal tunnel syndrome have the potential to reinforce misconceptions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479(10):2296–302. 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uzun M, Cingoz T, Duran ME, Varol A, Celik H. The videos on YouTube related to hallux valgus surgery have insufficient information. Foot Ankle Surg. 2022;28(4):414–7. 10.1016/j.fas.2021.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jildeh TR, Abbas MJ, Abbas L, Washington KJ, Okoroha KR. YouTube is a poor-quality source for patient information on rehabilitation and return to sports after hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2021;3(4):e1055–63. 10.1016/j.asmr.2021.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akpolat AO, Kurdal DP. Is quality of YouTube content on Bankart lesion and its surgical treatment adequate? J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):78. 10.1186/s13018-020-01590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kıvrak A, Ulusoy İ. How high is the quality of the videos about children’s elbow fractures on youtube?? J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):166. 10.1186/s13018-023-03648-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Yan C, Wu T, et al. YouTube online videos as a source for patient education of cervical spondylosis: a reliability and quality analysis. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1831. 10.1186/s12889-023-16495-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yüce A, İğde N, Ergün T, Mısır A. YouTube provides insufficient information on patellofemoral instability. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2022;56(4):306–10. 10.5152/j.aott.2022.22005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwak D, Park JW, Won Y, et al. Quality and reliability evaluation of online videos on carpal tunnel syndrome: a YouTube video-based study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e059239. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Celik H, Polat O, Ozcan C, et al. Assessment of the quality and reliability of the information on rotator cuff repair on YouTube. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2020;106(1):31–4. 10.1016/j.otsr.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Springer B, Bechler U, Koller U, et al. Online videos provide poor information quality, reliability, and accuracy regarding rehabilitation and return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2020;36(11):3037–47. 10.1016/j.arthro.2020.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuru T, Erken HY. Evaluation of the quality and reliability of YouTube videos on rotator cuff tears. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e6852. 10.7759/cureus.6852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mert A, Bozgeyik B. Quality and content analysis of carpal tunnel videos on YouTube. Indian J Orthop. 2022;56(1):73–8. 10.1007/s43465-021-00430-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osman W, Mohamed F, Elhassan M, Shoufan A. Is YouTube a reliable source of health-related information? A systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):382. 10.1186/s12909-022-03446-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tutan D, Kaya M. Evaluation of YouTube videos as a source of information on hepatosteatosis. Cureus. 2023;15(10):e46843. 10.7759/cureus.46843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruiz JG, Cook DA, Levinson AJ. Computer animations in medical education: a critical literature review. Med Educ. 2009;43(9):838–46. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abed V, Sullivan BM, Skinner M, et al. YouTube is a poor-quality source for patient information regarding patellar dislocations. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2023;5(2):e459–64. 10.1016/j.asmr.2023.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole EW, Bach KE, Theismann JJ, et al. Physician-led YouTube videos related to anterior cruciate ligament injuries provide higher-quality educational content compared to other sources. J ISAKOS. 2025;10:100367. 10.1016/j.jisako.2024.100367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cengiz T, Aydın Şimşek Ş, Ersoy A, et al. Assessment of YouTube videos on frozen shoulder: a quality analysis using DISCERN and JAMA scoring systems. Acta Med Alanya. 2024;8(1):15–9. 10.30565/medalanya.1417889. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madathil KC, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Greenstein JS, Gramopadhye AK. Healthcare information on youtube: a systematic review. Health Inf J. 2015;21(3):173–94. 10.1177/1460458214566226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.