Abstract

Background

Pediatric nurses operate in high-stakes environments characterized by emotional, cognitive, and physical demands. Excessive workload can undermine nurses’ ability to perform effectively, particularly when compounded by low self-efficacy. Core competencies such as clinical judgment, evidence-based practice, and communication are essential to pediatric nursing performance and are susceptible to the influence of psychological and environmental stressors.

Aim

This study aimed to examine the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between workload and core competencies among pediatric nurses in Egyptian governmental hospitals.

Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2024 to February 2025 with 198 pediatric nurses recruited from PICUs, NICUs, and pediatric wards using convenience sampling. Data were collected via self-administered questionnaires including the NASA Task Load Index (workload), General Self-Efficacy Scale, and the Core Competence Scale for Paediatric Specialist Nurses. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to assess direct and indirect effects.

Results

Nurses reported high workload (M = 63.79, SD = 10.21), low self-efficacy (M = 18.90, SD = 4.12), and low core competencies (M = 76.74, SD = 11.56). SEM results showed that workload negatively predicted self-efficacy (β = -0.285, p < 0.001), and self-efficacy positively predicted core competencies (β = 2.186, p < 0.001). Self-efficacy mediated the relationship between workload and core competencies, with a significant indirect effect (β = -0.624, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Self-efficacy acts as a psychological buffer against the negative effects of workload on professional performance. Enhancing nurses’ self-efficacy through targeted interventions may mitigate workload-related declines in core competencies and improve pediatric nursing care.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Keywords: Pediatrics, Self efficacy, Workload, Nursing staff, Hospital, Professional competence, Core competencies, Mediating role

Introduction

In the high-stakes pediatric healthcare contexts, the interplay between self-efficacy, workload, and core competencies among nurses is needed to ensure good quality patient care and professional satisfaction. Self-efficacy, or a nurse’s belief in their ability to perform job-related tasks successfully, significantly influences both their ability to decide wisely and resilience under pressure [1, 2]. Notably, the workload, heightened by shortages in staff, the seriousness of diagnoses, and administrative necessities, overpowers these beliefs, directly affecting their performance and well-being. Core competencies, encompassing the essential knowledge, skills, and attitudes required for pediatric care, serve as the foundation upon which self-efficacy is built and sustained, even under highly demanding conditions [3–5]. The relationship between self-efficacy and core competencies among pediatric nurses in high-pressure work environments is a critical area of study, as it directly impacts the quality of patient care and nurse performance [6].

Particularly in environments like critical care units, emergency rooms, and pediatric wards, self-efficacy is essential for developing the abilities of pediatric nurses. Self-efficacy in the context of nursing is a nurse’s confidence in their capacity to handle certain jobs, control stress, and deliver excellent treatment [7]. Self-efficacy is a psychological construct that influences an individual’s motivation, behavior, and persistence in the face of challenges [2, 8]. Higher degrees of self-efficacy have often been linked, in studies, to improved core competencies among pediatric nurses [1]. For example, studies on Chinese emergency room nurses revealed the general self-efficacy was quite highly connected with core competencies, as gauged by the Competency Inventory for Registered Nurses (CIRN) [9].

Maintaining the professional standards of nursing practice and providing high-quality care depend on pediatric nurses’ core competencies [3]. According to the current research, these competencies include the following: medical-related processes; professional technology mastery; specialist knowledge mastery; communication, coordination, and judgment skills; and evidence-based nursing competencies [10]. Every single domain is essential for the whole growth of nursing professionals since it helps them to fulfill the challenging requirements of contemporary healthcare environments. Pre-licensure core competencies, which are specific to pediatric nursing, focusing on the science, art, and practice of caring for children and their families, have been outlined by the Society of Pediatric Nurses. These competencies are designed to prepare nurses for the diverse challenges they will face in pediatric settings [4, 5].

Nursing competency in medical-related procedures is the ability to do required clinical tasks, including vital sign monitoring, medicine delivery, and wound care. Basic to patient treatment, these skills need ongoing education and training to maintain competency [11]. Masters of healthcare technology are nurses who wish to handle patient data and deliver therapy effectively as application of telemedicine systems and electronic health records [12]. Effective coordination and communication are vital for the provision of cooperative healthcare. Nurses who are adept at handling patients, families, and multidisciplinary teams will help to ensure flawless care transitions and patient safety [13]. Clinical decision-making relies on judgment skills, which enable nurses to correctly assess patient conditions and respond to changes in the health state [14].

Pediatric nurses carry out competencies independently in primary healthcare, such as health education, child development evaluations, vaccinations, and health checks. Among children and adolescents, these skills are essential for health promotion and illness prevention [15]. Pediatric nurses must possess skills in tertiary hospital environments, including nursing quality improvement, critical care, research and technology use, ethics, communication, and holistic care. Improving patient outcomes and guaranteeing thorough treatment for young patients depend on these skills [16]. These skills guarantee that nurses can react properly to crises and give young patients prompt and suitable treatment [17].

One important factor determining nurses’ professional competency is self-efficacy. Higher self-efficacy scores were linked to reduced levels of emotional weariness and anxiety, suggesting that self-efficacious nurses are better suited to manage the demands of high-pressure workplaces [15]. Previous study on pediatric nurses in Iran underlined that, especially in the setting of caring for children with complicated needs, self-efficacy is a major determinant of sustaining professional competency [10]. To improve general self-efficacy and competencies, a study on pediatric nurses in China, for instance, revealed that the nursing practice environment partially mediated the relationship between general self-efficacy and perceived professional benefits, thus underlining the need to create a supportive work environment [16].

Important determinants of both core skills and self-efficacy include experience and professional growth. Researchers looking at Thai pediatric nurses discovered that those with more experience and those who had attended training sessions on pediatric basic life support reported higher self-efficacy and lower stress levels [17]. Likewise, a study on ICU nurses found that prior experience in critical care situations and specialty can improve self-efficacy, thereby helping nurses to more successfully handle the demands of high-stress environments [18]. Major factors of self-efficacy and core competencies are job satisfaction and organizational support. Studies on Chinese emergency-room nurses revealed that married nurses and professional pleasure help to generate increased self-efficacy and competencies [15]. Research on pediatric nurses during the COVID-19 epidemic revealed that fatigue was negatively linked with self-efficacy, underlining the need for treatments addressing burnout and boosting resilience [9, 19].

Training strategies and focused educational programs can greatly raise core competency and self-efficacy. Training using concept maps enhanced caring self-efficacy, according to a study on nursing students in pediatric departments [20]. Fostering self-efficacy and basic competence depends on a supportive workplace. Based on research on pediatric nurses in China, a favorable practice environment is suggested to mediate the relationship between self-efficacy and professional advantages, implying that hospitals should give top priority to building a supportive work culture [16].

Pediatric nurses face a significant workload that impacts both their quality of work life and patient care outcomes. The workload in pediatric settings is influenced by various factors, including patient acuity, the frequency of alarms, and the complexity of care required. Understanding these factors is crucial for optimizing nurse staffing and improving both nurse and patient outcomes [21].

The subjective workload, as measured by the NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), has been shown to increase significantly in response to frequent physiologic monitor alarms, with more than 40 alarms within a two-hour period leading to heightened workload and an elevated risk of missed care [22]. High levels of mental workload and the presence of musculoskeletal disorders are common among pediatric nurses and are closely associated with increased intent to leave the profession. Notably, effort-related workload and frequent night shifts have been identified as significant predictors of this intention [23]. Increased nursing workload is associated with a higher incidence of adverse events in pediatric care settings. The clinical severity of patients is a predictive factor of the nursing workload required, emphasizing the need for adequate staffing to ensure patient safety [24]. A study was conducted t o identify the factors influencing pediatric nurses’ job stress and revealed the need for effective strategies to manage fatigue and reduce job stress among pediatric nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic [25].

Based on retrospective cohort research done in Vienna, excessive nursing workload correlates with a higher incidence of bloodstream infections [26]. Another study shows that poorer outcomes including higher mortality and longer durations of stay are linked with high workload on staff and significantly control workload and enhance patient outcomes in highly demanding environments [27]. A secondary study of qualitative data gathered in the United States reveals that pediatric nurses suffer tiredness connected to work pressures and individual risk factors, which might influence their workload [28]. Inaddition, previous study was conducted in NICU stated that adverse outcomes and stress among nurses linked to high workloads highlight the necessity of improved staffing policies to support pediatric nursing in critical care environments [29].

Despite the abundant international literature on the interplay between workload, self-efficacy, and core competencies, there is a notable lack of research addressing these dynamics within the context of pediatric nursing in Egypt. Previous research has predominantly been conducted in nations like China, Iran, and Thailand, where healthcare systems, resource accessibility, and professional contexts markedly contrast with those in Egypt. The absence of context-specific research is especially significant, considering the distinctive issues encountered by pediatric nurses in Egyptian governmental hospitals, such as staffing deficiencies, elevated patient acuity, and insufficient organizational support. Furthermore, the particular mediation model concerning self-efficacy has not, to our knowledge, been investigated in this context. This research aims to implement and validate the mediation framework within the Egyptian setting to guide targeted interventions and policy decisions suited to the local healthcare environment.

This study is grounded in Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), which posits a reciprocal relationship between personal factors (such as self-efficacy), environmental conditions (such as workload), and behavior (such as job performance). SCT emphasizes the importance of self-efficacy in shaping how individuals approach challenges, persist in the face of difficulties, and perform under pressure. In the nursing profession, especially in pediatric care, self-efficacy has been shown to influence clinical judgment, emotional resilience, and professional growth [1, 2].

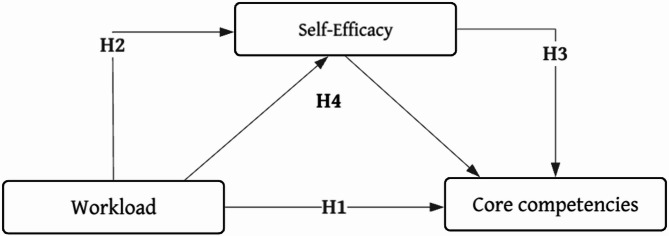

SCT provides a theoretical lens to understand how workload may impair performance by undermining self-efficacy and how self-efficacy may act as a mediator buffering the negative effects of workload on core competencies [1, 2]. This framework guides the study’s exploration of direct and indirect relationships among these key variables. Therefore, the present study was conducted to assess workload and core competencies among pediatric nurses and investigate the mediating role of nurses’ self-efficacy. Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized relationships among workload, self-efficacy, and core competencies.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesis of the study

Hypotheses

H1

(Direct Effect): There is a significant negative relationship between workload and core competencies among pediatric nurses.

H2

(Mediator Relationship): There is a significant negative relationship between workload and self-efficacy among pediatric nurses.

H3

(Mediation): There is a significant positive relationship between self-efficacy and core competencies among pediatric nurses.

H4

(Mediation Hypothesis): Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between workload and core competencies among pediatric nurses.

Methods

Research design

A descriptive quantitative study using a self-report questionnaire was conducted and reported according to the guidelines for Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE), which was conducted from November 2024 to February 2025.

Study setting

This study was conducted at pediatric intensive care units (PICU), pediatric wards, neonatal intensive care units (NICU), and pediatric wards in three governmental hospitals in Cairo, Egypt, affiliated with the Ministry of Health.

Sample size

To determine an appropriate sample size for the structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis, a power analysis was conducted based on reported effect sizes (0.29) by Liu et al. (2024), power (1 – β) at 0.90 and alpha (α) at 0.05. Using an SEM-focused sample size estimation formula appropriate for detecting a standardized regression path coefficient (MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996), by using the following equation for a simple path model:

|

the required sample size was estimated to be approximately 178 nurses, Z1-β = 1.28 (for 90% power), f = 0.29, and k = number of model parameters. By adding 10% attrition rate, the final adjusted sample size is calculated as: Adjusted sample size = n / (1 - Attrition rate) = 178 / 0.90 = 198 nurses. Therefore, the minimum required sample size for the study is 198 pediatric nurses to ensure adequate power for detecting the hypothesized mediation effect [30, 31].

Participants

Nurses were recruited through the convenience sampling method. Nurses were included in this study if they were currently working in pediatric care settings such as pediatric wards, NICUs, and PICUs. Eligible participants were required to hold a valid nursing license and have completed formal nursing education at a diploma, technical health institute, or Bachelor of Nursing. In addition, they needed to have at least one year of clinical experience in pediatric care. Only nurses who were willing to participate voluntarily and were able to provide informed consent were included. Invitations were sent to 220 nurses after assessing eligibility criteria; 198 patients responded (response rate: 90%).

Data collection

Characteristics of nurses

Age, gender, education level, years of experience in nursing, training courses related nurse role/last month, and nurse-to-patient ratio.

Self-efficacy

The General Self-Efficacy Scale, developed by Cid et al. (2010), is a self-report instrument designed to assess an individual’s perceived ability to cope with a variety of demanding situations. It comprises 10 items, each rated on a four-point Likert scale: 1 (incorrect), 2 (barely true), 3 (rather true), and 4 (true), with scores greater than 20 indicating high self-efficacy, and scores between 10 and 20 indicating low self-efficacy. Higher scores indicate greater perceived self-efficacy. The scale has demonstrated good reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients reported as α = 0.88 by Cid et al. (2010) [32], 0.87 by Li et al. (2024) [33], and 0.951 by Tong et al. (2024) [34].

Workload

The NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) is a subjective workload assessment tool originally developed for use in aviation and increasingly applied in healthcare settings to measure perceived workload [35, 36]. It assesses six dimensions: mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, performance, effort, and frustration. Each dimension is rated individually on a scale from 0 (very low) to 100 (very high), and the overall workload score is calculated as the unweighted average of the six ratings. Final scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater perceived workload. Interpretation categories include very low (0–20), low [19–38], moderate [8, 10, 39–55], high (61–80), and very high (81–100) workload (Febiyani et al., 2021). The reliability of the NASA-TLX has been supported in prior research, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients reported as 0.77 (Maghsoud et al., 2022) [37] and 0.72 for the overall workload scale [38].

Core competencies of pediatric specialist nurses

The Core Competence Scale for Pediatric Specialist Nurses, developed by Tang et al. (2023), consists of 32 items across five subdimensions: communication, coordination, and judgment ability (13 items); professional technology mastery ability (7 items); specialist knowledge mastery ability (6 items); medical-related processes (3 items); and evidence-based nursing competence (3 items). Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), yielding a total score between 32 and 160. Higher scores reflect greater core competence, with scores categorized as low (32–79) or high (80–160). The scale has demonstrated high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.944 and a split-half reliability coefficient of 0.883 [39].

Validity and reliability

With permission from the original developer of the three scales, the translation process was carried out following Brislin’s model [10]. Two bilingual translators, fluent in both Arabic and English, handled the translation and back-translation. The first translator, who also had a background in medication safety, translated the original English version into Arabic. The second translator, unfamiliar with the original text, then back-translated the Arabic version into English. Afterward, a panel of experts reviewed the original English scale, the back-translated version, and the Arabic translation to identify any discrepancies and ensure that the meaning and concepts were accurately preserved across all versions.

To ensure the psychometric soundness of the Arabic-translated instruments, a multi-step validation process was conducted. Following translation using Brislin’s model, the content validity of the NASA Task Load Index (workload), the General Self-Efficacy Scale, and the Core Competence Scale for Pediatric Specialist Nurses was assessed by a panel of seven bilingual experts in pediatric nursing and clinical practice. The average item-level Content Validity Index (I-CVI) values were 0.89, 0.93, and 0.91, respectively, indicating strong content validity. A pilot test involving 30 pediatric nurses confirmed the clarity and cultural appropriateness of the translated items. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed using the full study sample (N = 198) to assess construct validity. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) values demonstrated acceptable model fit: 0.91 for the NASA-TLX, 0.94 for the General Self-Efficacy Scale, and 0.92 for the Core Competence Scale. Reliability was evaluated using the test-retest method. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.860 for workload, 0.901 for self-efficacy, and 0.837 for core competencies, reflecting high internal consistency. Pearson’s correlation coefficients from the test-retest analysis were r = 0.843, 0.875, and 0.816, respectively, supporting the temporal stability of the instruments. These results confirm that the Arabic versions of the instruments are valid and reliable for use in the Egyptian pediatric nursing context.

Data collection procedure

Data were collected for four months, between November 2024 to February 2025. After obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and receiving clearance from hospital administration, the research team arranged to meet with nursing supervisors in all the participating hospitals to screen potential participants according to the inclusion criteria.

An online survey was used to gather data that would be convenient, accessible, and cost-efficient. The survey was planned with a secure and user-friendly online website. A brief introduction to the study, reason, procedures, assurances of confidentiality, and informed consent were provided at the beginning of the survey. Subjects were required to confirm their consent before they entered the main questions. The link for the survey was disseminated among nurses via official email and WhatsApp groups managed by head nurses. Reminders were sent weekly during the data collection period to prompt a response and ensure a good response rate.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 26) was used to code and enter the collected data. Descriptive statistics were used to assign demographic characteristics to numbers, that is, frequency distributions, means, standard deviations, and percentages. Quantitative data were presented as values and percentages. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the data distribution. A correlation coefficient was generated to visually display correlations between workload, self-efficacy, and core competency. A structural equation model (SEM) is a statistical model that combines principles of factor analysis and path analysis to represent hypothesized relationships among latent constructs and their observed indicators. Subsequently, structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied, which allowed evaluating the direct and mediator effects of latent predictor variables on outcome variables [40]. The indirect effects represent the portion of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables that is mediated by a third variable [40].

The SEM model specified workload and self-efficacy as latent variables and core competencies as the outcome construct. Model fit was assessed using several indices: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Parameter of model fit was defined as CFI 0.93, RMSEA 0.042, and SRMR 0.067. Missing data were minimal (< 5%) and were handled using listwise deletion, under the assumption that data were Missing Completely at Random (MCAR).

Furthermore, linear regression analysis was employed to assess the relationship between the report’s core competency and independent variables [41]. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic and professional characteristics of the 198 nurses included in the study. The mean age was 33.31 years (SD = 5.49), and the average years of nursing experience was 9.09 years (SD = 4.85). The sample was predominantly female (68.7%). In terms of educational attainment, nearly half of the nurses held a bachelor’s degree (49.5%), while the remainder had either a technical health institute qualification (33.8%). Notably, 70.7% of the nurses reported attending training courses in the last month. Additionally, most nurses were working under a 1:3 nurse-to-patient ratio (63.1%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studied nurses (n = 198)

| Sociodemographic characteristics | no. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

|

Mean (SD) 33.31 (5.49) Gender |

||

|

Male Female |

62 136 |

31.3 68.7 |

| Education level | ||

| Bachelor | 98 | 49.5 |

|

Technical health inistitute Diplom |

67 33 |

33.8 16.7 |

| Training courses related nurse role / last month | ||

| Yes | 140 | 70.7 |

| No | 58 | 29.3 |

| Nurse to Patient Ratio | ||

|

1:2 1:3 1:4 |

45 125 28 |

22.7 63.1 14.2 |

| Years experience in nursing / Mean (SD) | 9.09 (4.85) | |

SD: Standard deviation

Table 2 displays that the mean score of workload was 63.79 (SD = 29.96), which indicates a high level of workload among nurses. Core competencies have a mean score of 76.74 (SD = 25.59), indicating a low level of core competencies among the participants. Self-efficacy has a mean score of 18.90 (SD = 8.75), which is categorized as low.

Table 2.

Mean scores of workload, self-efficacy, and core competencies (n = 198)

| Study variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workload | 63.79 | 29.96 | 12 | 94 | High |

| Core competencies | 76.74 | 25.59 | 32 | 140 | Low |

| Self-Efficacy | 18.90 | 8.75 | 10 | 40 | Low |

SD: Standard Deviation

Table 3 presents the negative correlation between core competencies and workload as -0.812 (p < 0.001). Also, there is a negative correlation between self-efficacy and workload of -0.877 (p < 0.001). Finally, there was a positive correlation between core competencies and self-efficacy of 0.825 (p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Correlation between workload, self-efficacy, and core competencies (n = 198)

| Core competencies | Workload | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Workload |

r. p. |

-0.812 < 0.001 |

|

| Self-Efficacy |

r. p. |

0.825 < 0.001 |

-0.877 < 0.001 |

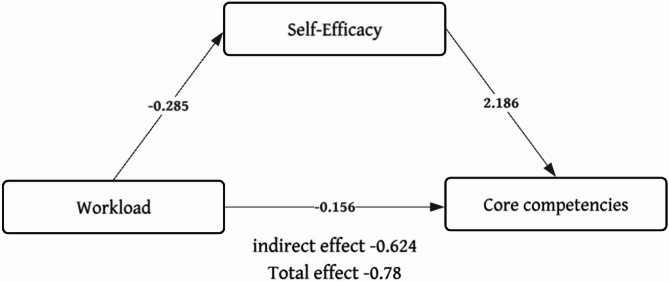

As shown in Table 4; Fig. 2, the mediation analysis provided robust support for the hypothesis that self-efficacy mediates the relationship between workload and core competencies among nurses. The direct path from workload to self-efficacy was strongly negative and statistically significant (β = −0.285, p < 0.001), indicating that higher workload reduces nurses’ confidence in their professional capabilities.

Table 4.

Mediation analysis results for the effect of workload on core competencies via mediating factor self-efficacy

| β | SE | Z value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct (Workload → Self-Efficacy) | -0.285 | 0.004 | -64.22 | 0.000 |

| Direct (Self-Efficacy → Core Competencies) | 2.186 | 0.371 | 5.90 | 0.000 |

| Direct (Workload → Core Competencies) | -0.156 | 0.108 | -1.44 | 0.152 |

| Indirect Effect (via Self-Efficacy) | -0.624 | 0.106 | -5.87 | 0.000 |

| Total Effect (Workload → Core Competencies) | -0.78 | 0.025 | -31.22 | 0.000 |

Fig. 2.

SEM for the effect of workload on the core competencies via the mediating factor self-efficacy

In turn, self-efficacy had a strong positive effect on core competencies (β = 2.186, p < 0.001), confirming that greater confidence is associated with higher performance and skill proficiency. Importantly, when self-efficacy was included in the model, the direct effect of workload on core competencies became non-significant (β = −0.156, p = 0.152), while the indirect effect via self-efficacy remained substantial (β = −0.624, p < 0.001). The total effect of workload on core competencies (β = −0.78, p < 0.001) reinforces the idea that workload has a detrimental impact on nursing performance, but this effect is largely explained by its influence on self-efficacy. The structural model presented in Fig. 2 visually supports this mediation structure, illustrating that self-efficacy serves as the psychological mechanism through which environmental stressors impair professional functioning. These findings highlight the central role of self-efficacy in maintaining competence under pressure and suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing confidence and psychological resilience may effectively mitigate the performance-related consequences of high workload.

The comparison between the two regression models in Table 5 provides strong evidence supporting the mediating role of self-efficacy in predicting core competencies among nurses. In Model 1, which includes self-efficacy, the predictor showed a strong, significant positive association with core competencies (β = 0.708, p < 0.001), while the effect of workload became statistically non-significant. This suggests that the negative impact of workload is largely transmitted through its suppression of self-efficacy. Conversely, in Model 2, where self-efficacy was excluded, workload emerged as a strong and significant negative predictor (β = -0.882, p < 0.001), indicating its direct detrimental effect when the buffering influence of self-efficacy is unaccounted for. Both models identified experience and training as consistent positive predictors of core competencies. However, Model 1 achieved better model fit (R² = 0.868) compared to Model 2 (R² = 0.819), underscoring the theoretical and statistical importance of including self-efficacy in models of professional competence.

Table 5.

Regression models for core competencies

| Variable | Model 1(With Self-Efficacy) | Model 2 (Without Self-Efficacy) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Beta | p | B | Beta | p | |

| Workload Score | -0.168 | -0.19 | 0.132 | -0.78 | -0.882 | 0.000 |

| Self-Efficacy Score | 2.144 | 0.708 | 0.000 | |||

| Age | -0.002 | -0.001 | 0.985 | -0.057 | -0.012 | 0.687 |

| Experience | 0.668 | 0.122 | 0.001 | 0.771 | 0.141 | 0.001 |

| Ratio (1:3) | − 0.206 | -0.022 | 0.485 | − 0.316 | -0.042 | 0.211 |

| Ratio (1:4) | -0.494 | -0.007 | 0.837 | -0.065 | -0.001 | 0.98 |

| Training (Yes) | 0.792 | 0.136 | 0.001 | 0.820 | 0.141 | 0.000 |

|

R² 0.868 F 87.66 P 0.000 |

R² 0.819 F 72.43 P 0.000 |

|||||

Discussion

This study addressed the role of self-efficacy in mediating the relationship between pediatric nurses’ workload and their core competencies. We found a high overall workload among nurses working in pediatric wards with low core competencies and low self-efficacy. The current results echoed the findings of studies from different settings where a significant proportion of nurses report high workload [42–45], low core competencies among nurses [46, 47], and low self-efficacy [48, 49].

This high overall workload among nurses working in pediatric areas reflects the intense demands inherent in caring for acutely ill and vulnerable children. This workload, when sustained over time, is known to contribute to stress, emotional exhaustion, and burnout. Compounding this concern is the finding of low self-efficacy and diminished core competencies among nurses in these roles. These findings could be explained due to the work environment itself, in terms of intense demands,, psychological pressures, and organizational challenges, all of which contribute to occupational burnout and high turnover rates., which is taking a significant toll on their core competency levels may further exacerbate stress, as nurses may feel ill-equipped to meet the complex demands of pediatric care, leading to a cycle of decreased confidence and performance. This justification is backed by the findings of studies conducted among nurses [50–52].

The correlation results revealed an adverse relationship between workload and core competencies, as well as between workload and self-efficacy, with a positive correlation between core competencies and self-efficacy. On one hand, these correlation results endorse the affirmation that low confidence in own capabilities and increased work requirements beyond nurses’ abilities are significant determinants in decreasing core competencies. On the other hand, having high confidence and belief that they can execute tasks successfully is a main determinant of having a high level of core competencies. The regression model results enhanced this explanation by quantifying the central role of self-efficacy.

In the study, a significant positive correlation was found between core competencies and self-efficacy (r = 0.825, p < 0.001). Since higher self-efficacy can enhance the level of core competencies and vice versa. Studies have consistently shown a positive correlation between core competencies and self-efficacy among nurses. For instance, in a study conducted in the Hamad Medical Corporation among 780 nurses, self-efficacy was found to have a predictive effect on core competency scores, indicating that nurses with higher self-efficacy tend to exhibit stronger core competencies [46]. The same results were reported among nurses in China [30]. In contrast, a study on Albanian registered nurses found that self-efficacy did not significantly impact professional competence, suggesting that job satisfaction might be a more crucial factor in developing professional skills [53]. The differing findings can be attributed to variations in cultural, organizational, and contextual factors across countries.

Furthermore, A significant negative correlation was observed between workload and core competencies (r = − 0.812, p < 0.001). This suggests that a higher workload leads to a decrease in the efficiency in completing tasks neatly. Put it differs, when pediatric nurses are overwhelmed with many tasks to be completed within the same time window, they fail to achieve excellence on what they are expected to complete as per their job descriptions in terms of the core competencies, namely medical-related processes, professional technology mastery, specialist knowledge mastery, communication, coordination, and judgment skills, and evidence-based nursing competencies. A recent study conducted in Tangerang indicated a significant negative correlation between the two variables [54]. Similarly, a systematic literature review confirmed that high workload is a major challenge for nurses, leading to declines in performance in hospital inpatient settings [45].

Likely, there was a significant negative correlation between workload and self-efficacy (r = -0.877, p < 0.001). This indicates that a high workload exceeds nurses’ capacity to perform tasks effectively. In the same line with our findings, studies conducted in various countries reported the same direction of relationship in Saudi Arabia [55], Canada [8], and Surabaya [56].

The rationale for these findings can be ascribed to multiple interconnected causes. Excessive workload frequently leads to cognitive fatigue, impairing nurses’ ability to concentrate, make accurate clinical judgments, or communicate effectively—skills vital to their core abilities. Time limits exacerbate this issue, compelling nurses to expedite tasks, thereby jeopardizing the quality and safety of patient care. Furthermore, the physical and mental exhaustion resulting from substantial workloads undermines nurses’ capacity to uphold professional standards, particularly in challenging settings such as pediatric wards. The restricted time for contemplation, continued study, and skill advancement impedes the continual improvement of specialized knowledge and evidence-based practice. Experiencing identical circumstances in which performance is hindered by an excessive work environment results in diminished self-efficacy, as nurses start to question their capacity to provide high-quality care. The interrelated elements clarify the pronounced negative association identified in this study.

When reflecting on the study results, it is necessary to take into account the overall system and culture in relation to Egyptian governmental hospitals. These institutions are often plagued with problems of inadequate manpower, high patient-to-nurse ratios, and limited resources, all of which can exacerbate the already elevated workload levels. Moreover, the organizational hierarchy and administrative red tape can restrict a nurse’s self-governance and stifle chances for skill enhancement. These contextual factors are critical to understand because they may mediate or moderate the relationships explored in this research, and should be addressed in any future attempts designed to enhance nursing performance and well-being.

Moreover, self-efficacy had a mediating effect on the relationship between workload and nurses’ core competencies. The efficiency of the core competencies decreases among pediatric nurses who reported a high level of workload and low self-efficacy. The findings underscore the pivotal role of self-efficacy in sustaining competence under pressure and indicate that interventions designed to bolster confidence and psychological resilience may effectively alleviate the performance-related effects of elevated workload. The substantial correlation among research variables substantiates the literature’s assertions that these concepts may be crucial in surmounting obstacles to nurses’ performance.

Limitations

The data were collected through self-reported measures, which may be subject to response bias, including social desirability. As convenience sampling was used, the study may be subject to selection bias, and the results may not be generalizable to all pediatric nurses, particularly those working in private or non-governmental institutions. Future studies using random or stratified sampling methods are recommended. Future studies are encouraged to explore the factors such as years of experience, education level, and organizational support within a moderated mediation or interaction-based SEM framework for a more nuanced understanding of their impact.

Conclusion

This study examined the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between workload and core competencies among pediatric nurses. The findings revealed that high workload is significantly associated with reduced self-efficacy and diminished core competencies, while self-efficacy was positively linked to higher core competency levels. Importantly, self-efficacy fully mediated the relationship between workload and core competencies, underscoring its critical role in buffering the negative effects of occupational stressors. These results highlight the importance of not only managing workload but also fostering psychological resources like self-efficacy to enhance professional performance. By addressing both environmental and cognitive factors, healthcare organizations can better support pediatric nurses in maintaining high standards of care under pressure.

Implications for practice

The findings of this study carry important implications for nursing management and policy. Interventions aimed at reducing workload, such as optimizing nurse-to-patient ratios, streamlining administrative tasks, and minimizing unnecessary disruptions, are essential to protect nurse well-being and care quality. Equally important is the need to enhance nurses’ self-efficacy through structured support programs, including mentorship, continuous education, performance feedback, and leadership that fosters autonomy and professional growth. Healthcare administrators should integrate psychological resilience-building strategies into professional development initiatives to strengthen nurses’ confidence and performance under pressure.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R448), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author contributions

“Conceptualization”, Abdelaziz Hendy, Rasha Ibrahim; Methodology, Zainab Attia Abdallah, Amna Nagaty Aboelmagd, Naglaa Hassan Abuelzahab; validation, Nasiru Mohammed Abdullahi, Lisa Babkair, Yasir S. Alsalamah; formal analysis, Rahmah Khubrani, Naglaa Hassan Abuelzahab; Statistical analysis: Abdelaziz Hendy, Rasha Ibrahim; writing—original draft preparation, Abdelaziz Hendy, Rasha Ibrahim Kadri; Rahmah Khubrani, Naglaa Hassan Abuelzahab, Amna Nagaty Aboelmagd, Hanan F. Alharbi, Nasiru Mohammed Abdullahi, Lisa Babkair, Yasir S. Alsalamah, Zainab Attia Abdallah; Editing: Abdelaziz Hendy, Rasha Ibrahim; Nasiru Mohammed Abdullahi Visualization, Lisa Babkair, Yasir S. Alsalamah; project administration, Abdelaziz hendy, Rasha Ibrahim; All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Also, all participate in prepare the manuscript.

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R448), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data availability

The data are provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Faculty of Nursing at Modern University for Technology and Information (MTI), with ID FAN/146/2024, waived ethical approval. All participating nurses were provided comprehensive information about the study’s purpose, objectives, and potential benefits. The researchers emphasized the study’s voluntary nature, and patients could withdraw their participation without facing any consequences. All procedures were conducted in compliance with pertinent rules and regulations. We confirm that our study was conducted by the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Nurses were required to provide written informed consent before participating in the study. Participation was entirely voluntary, and nurses had the right to withdraw at any stage without any consequences. The collected data was coded to maintain confidentiality, ensuring no identifiable information was disclosed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Abdelaziz Hendy, Email: abdelaziz.hendy@nursing.asu.edu.eg.

Rasha Kadri Ibrahim, Email: rasha.ibrahim@actvet.gov.ae.

References

- 1.Alavi A, Bahrami M, Zargham-Boroujeni A, Yousefy A. Threats to pediatric nurses’ perception of caring Self-efficacy: A qualitative study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(3):e25716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrahim RK, Aldawsari AN. Relationship between digital capabilities and academic performance: the mediating effect of self-efficacy. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laserna Jiménez C, Garrido Aguilar E, Casado Montañés I, Estrada Masllorens JM, Fabrellas N. Autonomous competences and quality of professional life of paediatric nurses in primary care, their relationship and associated factors: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(3–4):382–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis MN, Goleman G, Kubin L, Alles K, Beam P, Benedetto CO, et al. Society of pediatric nurses’ Pre-Licensure core competencies model, second edition. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;76:207–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maniscalco J, Gage S, Teferi S, Fisher ES. The pediatric hospital medicine core competencies: 2020 revision introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):389–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Shammari M, Elfeshawy R. Assessing competencies and self-efficacy of paediatric nursing in Iraq using NCSES scale: A pilot study. Int J Nurs Health Sci. 2024;6:101–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krongthammachart K, Nookong A, Wongmuan K. The relationships between knowledge, perceived Self-Efficacy, and barriers to nursing practice for psychosocial nursing care in hospitalized children. Nurs Sci J Thail. 2017;35(2):28–38. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bawazier B, Almulla H, Mansour M, Hammad S, Alameri R, Aldossary L, et al. The relationship between perceived Self-Efficacy and resilience among pediatric nurses in Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2025;18:739–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Zhou M, Wang H, Hao W. Factors associated with core competencies of emergency-room nurses in tertiary hospitals in China. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2020;17(3):e12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang Q, Zhang D, Chen J, Liu M, Xiang Y, Luo T, et al. Tests on a scale for measuring the core competencies of paediatric specialist nurses: an exploratory quantitative study. Nurs Open. 2023;10(8):5098–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alshammari YFH, Alharbi MN, Alanazi HF, Aldhahawi BK, Alshammari FM, Alsuwaydaa RH, et al. General health practitioner skills and procedures. Int J Health Sci. 2022;6(S8):7139–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker JA. Core Clinical Nurse Specialist Practice Competencies. In: Fulton JS, Holly VW, editors. Clinical Nurse Specialist Role and Practice: An International Perspective [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021 [cited 2025 May 8]. pp. 37–52. Available from: 10.1007/978-3-319-97103-2_3

- 13.Kompetensbeskrivning för legitimerad sjuksköterska [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 8]. Available from: https://swenurse.se/publikationer/kompetensbeskrivning-for-legitimerad-sjukskoterska

- 14.Winter PB. The design of an Evidence-Based competency model. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2018;34(4):206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gil-Almagro F, Carmona-Monge FJ, García-Hedrera FJ, Peñacoba-Puente C. Self-efficacy as a psychological resource in the management of stress suffered by ICU nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective study on emotional exhaustion. Nurs Crit Care. 2025;30(3):e13172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibrahim R, Varghese M, Salim SS. A Cross-Sectional study on nursing preceptors’ perspectives about preceptorship and organizational support. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024;10:23779608241288756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng L, Cui Y, Chen Q, Ye Y, Liu Y, Zhang F, et al. Paediatric nurses’ general self-efficacy, perceived organizational support and perceived professional benefits from class A tertiary hospitals in Jilin Province of china: the mediating effect of nursing practice environment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendy A, Hassani R, Abouelela MA, Alruwaili AN, Fattah HAA, Atia GA, elfattah, et al. Self-Assessed capabilities, attitudes, and stress among pediatric nurses in relation to cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023;16:603–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ODACI N. KALANLAR B. The relationship between Self-efficacy for managing Work-Family conflict, psychological resilience and burnout levels among Covid 19- ICU nurses. Sağlık Bilim Üniversitesi Hemşire Derg. 2022;4.

- 20.Vera M, Lorente L. Nurses´ performance: the importance of personal resources for coping with stressors. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2023;44(9):844–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alavi A, Okhovat F. Effects of training nursing process using the concept map on caring self-efficacy of nursing students in pediatric departments. J Educ Health Promot. 2024;13:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebet RM, Hasbani NR, Sisko MT, Agus MSD, Nadkarni VM, Wypij D, et al. Nurses’ perceptions of workload burden in pediatric critical care. Am J Crit Care. 2021;30(1):27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasooly IR, Kern-Goldberger AS, Xiao R, Ponnala S, Ruppel H, Luo B, et al. Physiologic monitor alarm burden and nurses’ subjective workload in a children’s hospital. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(7):703–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naserian E, Pouladi S, Bagherzadeh R, Ravanipour M. Relationship between mental workload and musculoskeletal disorders with intention to leave service among nurses working at neonatal and pediatric departments: a cross-sectional study in Iran. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nieri AS, Spithouraki E, Galanis P, Kaitelidou D, Matziou V, Giannakopoulou M. Clinical severity as a predictor of nursing workload in pediatric intensive care units: A Cross-Sectional study. Connect World Crit Care Nurs. 2019;13(4):175–Page. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeon BY, Yun SJ, Kim HY. Factors influencing job stress in pediatric nurses during the pandemic period: focusing on fatigue, pediatric nurse– parent partnership. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2024;29(4):e12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Küng E, Waldhör T, Rittenschober-Böhm J, Berger A, Wisgrill L. Increased nurse workload is associated with bloodstream infections in very low birth weight infants. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fundora MP, Liu J, Calamaro C, Mahle WT, Kc D. The association of workload and outcomes in the pediatric cardiac ICU*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2021;22(8):683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hittle BM, Keller EG, Lee RC, Daraiseh NM. Pediatric nurses’ fatigue descriptions in occupational injury reports: A descriptive qualitative study1. Work Read Mass. 2024;79(3):1307–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franco APV, Hamasaki BP, de Puiz A, de Dorigan LR, Dini GH, Carmona AP. Dimensioning of nursing team at neonatal intensive care unit: real versus ideal / Dimensionamento de enfermagem Em Unidade de terapia intensiva neonatal: real versus ideal. Rev Pesqui Cuid É Fundam Online. 2021;13:1536–41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu A, Wang D, Xu S, Zhou Y, Zheng Y, Chen J et al. Correlation between organizational support, self-efficacy, and core competencies among long-term care assistants: a structural equation model. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2024 Sep 17 [cited 2025 May 11];15. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.orghttps://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1411679/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(2):130–49. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cid HP, Orellana YA, Barriga O. Validación de La Escala de autoeficacia general En Chile. Rev Médica Chile. 2010;138(5):551–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li YR, Liu JY, Fang Y, Shen X, Li SW. Novice nurses’ transition shock and professional identity: the chain mediating roles of self-efficacy and resilience. J Clin Nurs. 2024;33(8):3161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong Y, Wang T, Tong S, Tang Z, Mao L, Xu L, et al. Relationship among core competency, self-efficacy and transition shock in Chinese newly graduated nurses: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2024;14(4):e082865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hart SG, Staveland LE. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of Empirical and Theoretical Research. In: Hancock PA, Meshkati N, editors. Advances in Psychology [Internet]. North-Holland; 1988 [cited 2025 May 13]. pp. 139–83. (Human Mental Workload; vol. 52). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166411508623869

- 37.Tubbs-Cooley HL, Mara CA, Carle AC, Gurses AP. The NASA task load index as a measure of overall workload among neonatal, paediatric and adult intensive care nurses. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;46:64–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maghsoud F, Rezaei M, Asgarian FS, Rassouli M. Workload and quality of nursing care: the mediating role of implicit rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion by using structural equations modeling approach. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoonakker P, Carayon P, Gurses A, Brown R, McGuire K, Khunlertkit A, et al. MEASURING WORKLOAD OF ICU NURSES WITH A QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY: THE NASA TASK LOAD INDEX (TLX). IIE Trans Healthc Syst Eng. 2011;1(2):131–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brislin RW. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural research. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 1970;1(3):185–216. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Byrne BM, Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS. EQS, and LISREL: Comparative Approaches to Testing for the Factorial Validity of a Measuring Instrument. Int J Test [Internet]. 2001 Mar 1 [cited 2025 May 13]; Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15327574IJT0101_4

- 42.Kothe) DN (bookdown translation: E. Chapter 15 Linear regression| Learning statistics with R: A tutorial for psychology students and other beginners. (Version 0.6.1) [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 13]. Available from: https://learningstatisticswithr.com/book/regression.html

- 43.Padila P, Andri J. Beban Kerja Dan Stres Kerja Perawat Di Masa pandemi Covid-19. J Keperawatan Silampari. 2022;5(2):919–26. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan Z, Wang J, Feng F, Jin M, Xie W, He H, et al. The levels and related factors of mental workload among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Pract. 2023;29(5):e13148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Astari DW, Kartikaningsih K, Setiawan D. Evaluation of nurse workload in patient units. Indones J Glob Health Res. 2024;6(1):83–94. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kurnia A, Karmilah K, Khusnul N, Fatimah S, Intan T, Ridwan H, et al. The effect of workload on nurse performance in hospital inpatient settings: A systematic literature review. Genius J. 2024;5(2):315–25. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nejadshafiee M, Mirzaee M, Aliakbari F, Rafiee N, Sabermahani A. Nekoei-moghadam M. Hospital nurses’ disaster competencies. Trauma Mon. 2020;25(2):89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo J, Dai Y, Chen Y, Liang Z, Hu Y, Xu X, et al. Core competencies among nurses engaged in pallative care: A scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2024;33(10):3905–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hussien RM, Alharbi TAF, Alasqah I, Alqarawi N, Ngo AD, Arafat AEAE, et al. Burnout among primary healthcare nurses: A study of association with depression, anxiety and Self-Efficacy. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2025;34(1):e13496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiong H, Yi S, Lin Y. The psychological status and Self-Efficacy of nurses during COVID-19 outbreak: A Cross-Sectional survey. INQUIRY. 2020;57:0046958020957114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luo AM, Yang YS, Zhong Y, Zeng RF, Liao QH, Yuan J, et al. Exploring factors contributing to occupational burnout among nurses in pediatric infection wards Post-COVID-19. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2024;17:5309–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lucchini A, Villa M, Del Sorbo A, Pigato I, D’Andrea L, Greco M, et al. Determinants of increased nursing workload in the COVID-era: A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data. Nurs Crit Care. 2024;29(1):196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mannethodi K, Hassan N, Kunjavara J, Pitiquen EE, Joy G, Al-Lenjawi B. Research Self-Efficacy and Research-Related behavior among nurses in qatar: A Cross-Sectional study. Florence Nightingale J Nurs. 2023;31(3):138–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duka B, Stievano A, Prendi E, Spada F, Rocco G, Notarnicola I. An observational Cross-Sectional study on the correlation between professional competencies and Self-Efficacy in Albanian registered nurses. Healthcare. 2023;11(15):2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anggela FE, Hilmy MR, Wahidi KR. Effect of workload and nurse competency on patient safety incidents and application of 6 patient safety goals as intervening variables. J Health Sains. 2023;4(3):117–28. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buckley L, Berta W, Cleverley K, Widger K. The Relationships Amongst Pediatric Nurses’ Work Environments, Work Attitudes, and Experiences of Burnout. Front Pediatr [Internet]. 2021 Dec 21 [cited 2025 May 11];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.orghttps://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pediatrics/articles/10.3389/fped.2021.807245/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.