Abstract

Plasmids play key roles in the spreading of many traits, ranging from antibiotic resistance to varied secondary metabolism, from virulence to mutualistic interactions, and from defense to antidefense. Our understanding of plasmid mobility has progressed extensively in the last few decades. Conjugative plasmids are still often the textbook image of plasmids, yet they are now known to represent a minority. Many plasmids are mobilized by other mobile genetic elements, some are mobilized as phages, and others use atypical mechanisms of transfer. This review focuses on recent advances in our understanding of plasmid mobility, from the molecular mechanisms allowing transfer and evolutionary changes of plasmids to the ecological determinants of their spread. In this emerging, extended view of plasmid mobility, interactions between mobile genetic elements, whether involving exploitation, competition, or elimination, affect plasmid transfer and stability. Likewise, interactions between multiple cells and their plasmids shape the latter patterns of transfer through transfer-mediated bacterial predation, interference, or eavesdropping in cell communication, and by deploying defense and antidefense activity. All these processes are relevant for microbiome intervention strategies, from plasmid containment in clinical settings to harnessing plasmids in ecological or industrial interventions.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Plasmids [1] are extracellular molecules of DNA that replicate autonomously in a regulated and controlled way, keeping an approximate stoichiometry with the chromosome. This distinguishes them from other mobile genetic elements (MGEs) that may have a plasmid-like structure during horizontal transfer between cells, such as excised genomic islands, filamentous or virulent bacteriophages (phages), but that are usually not replicating as plasmids in pace with the cell cycle. Plasmids profoundly shape bacterial evolution and adaptation. Their capacity for genetic exchange has transformed our understanding of microbial ecology and has broad implications in fields ranging from infectious disease management to synthetic biology. Since plasmids carry genes that confer adaptive traits—such as antibiotic resistance, virulence, and metabolic versatility—plasmids facilitate the rapid spread of advantageous traits across diverse microbial communities, thereby driving genetic diversity and ecological fitness in bacteria [2]. Bacteria and Archaea access a vast gene reservoir through horizontal gene transfer (HGT), and plasmids constitute a substantial portion of this pool [3]. As an example, 46% of the complete bacterial sequences in the RefSeq dataset contain plasmids (Fig. 1A-C), with a median of two per host. These plasmids are scattered across the Prokaryotic taxonomy with higher numbers among the most sampled bacteria. But the frequency of plasmids is uneven across phyla, with some showing a clear majority of genomes with plasmids (Pseudomonadota), and others a minority (Bacillota) (Fig. 1B). Plasmid transfer underpins the open pangenomes observed in many microbial species (reviewed in [4–6]). Of particular concern, plasmid-mediated spread of antibiotic resistance is driving the current emergence of multidrug resistant bacteria with serious implications in public health [7]. The advances in genomics over the last decades have expanded our understanding of the evolutionary dynamics of plasmids, showing how they interact with chromosomal elements and other MGEs, including transposons and integrons. Such interactions enable plasmids to recruit and disseminate resistance and virulence determinants, sometimes from environmental reservoirs, into clinical settings [3].

Figure 1.

Plasmid distribution in the RefSeq database. The NCBI RefSeq database (release 229, 3 March 2025) includes 47 368 complete bacterial genome sequences, of which 21 801, distributed across 28 phyla, contain a total of 58 156 plasmids (A). For the 10 bacterial phyla with the highest number of plasmid-containing members, the abundance of genomes with and without plasmids is shown (B). The number of plasmids per bacterial host ranges from 0 to 28 and decreases exponentially (C). Plasmid size exhibits a bimodal distribution (when log-transformed) (D).

Several classification systems have been created to organize plasmid diversity by focusing on particular functions, including the use of replication or partition incompatibility types [8, 9], relaxases [10, 11], or conjugative pilus [12] (reviewed in [13]). Recently, the identification of plasmid taxonomic units (PTUs) provided a framework for categorizing plasmids as cohesive evolutionary entities akin to bacterial species [14]. PTUs group plasmids based on all conserved genetic markers, including those defining their type of mobility, allowing researchers to better understand their evolutionary dynamics and functional implications. Closely related plasmids also tend to have similar size, a trait that is highly variable among plasmids (Fig. 1D). The adaptive traits associated with a PTU shape the ecological roles and stability of plasmids in microbial communities.

Conjugation is regarded as the most frequent mechanism of plasmid transfer. Imaging techniques [15] and dynamic studies of conjugation [16], have recently provided unprecedented insights into the mechanics and regulation of plasmid transfer. These findings highlight previously unrecognized components and steps within the conjugation process, shedding light on factors that may affect plasmid stability, transfer rate, and host range. The traditional model of conjugation as a simple process of exchange between two cells mediated by a conjugative pilus under the control of a single plasmid has thus evolved to reflect a highly regulated, adaptive process that varies significantly across bacterial species, environmental contexts, and PTUs [14].

Beyond traditional conjugation mechanisms, plasmid biology encompasses a remarkable diversity of mobility strategies. Among the most intriguing recent discoveries is the abundance of elements that blur the boundary between plasmids and bacteriophages. These “phage-plasmids” combine the reproductive and transmission strategies of both, leveraging phage-like pathways to bypass the spatial and environmental constraints of standard conjugation (assessed in [17]). By forming phage particles and packaging their genetic material, these elements can transfer genes across microbial populations in a manner akin to viral infection, significantly broadening plasmid ecological and evolutionary impact. The dual functionality of phage-plasmids positions them as key players in the horizontal dissemination of adaptive traits, such as antibiotic resistance and stress response capabilities, within microbial communities.

In addition to classical conjugation and the emerging role of phage-plasmids, plasmid mobility encompasses mechanisms that rely on the functions of other MGEs for transmission. These mechanisms include plasmids that encode genetic information allowing to use helper plasmid conjugative systems for mobilization (reviewed in [18]). These processes are facilitated by the presence of numerous plasmids in the same cell, up to 28 different ones among the available genomes (Fig. 1). Plasmids can also be mobilized by phage transduction, whereby they are packaged and transferred by viral particles [19, 20], conduction, where plasmids transfer by recombining with coresident transmissible element via transposable elements (reviewed in [21]), and vesicle-mediated transfer (reviewed in [22]). All these forms of indirect mobility extend the functional versatility of MGEs, enabling the horizontal transfer of genetic material without requiring fully autonomous transfer machinery. This “hitchhiking” behavior has raised questions about the adaptability and survival strategies of plasmids in situations where autonomous transfer is not possible. By leveraging pre-existing systems, all these transmissible elements lower their costs while maintaining adaptability and evolutionary significance, further underscoring the complexity and plasticity of plasmid-mediated gene transfer.

The specificity of plasmid–host interactions is another critical aspect for plasmid mobility, with implications for understanding the selective pressures that influence plasmid spread and persistence. Studies on plasmid receptor interactions highlighted the role of host cell surface components in determining plasmid compatibility (reviewed in [23]). Quorum sensing also regulates plasmid transfer, thereby coordinating this process with host population density and environmental signals (reviewed in [24]). This raises questions about whether plasmids exhibit a preference for certain hosts and how microbial community composition might shape plasmid dissemination.

Finally, the dynamic nature of plasmid evolution is highlighted by the modification of plasmids into various forms throughout their life cycle. Some plasmids evolve to become integrative elements [25], to transfer genes in the host genome [26], or lose genes to emerge as small plasmids with limited functionality [27]. Similarly, plasmids may emerge from integrative elements or increase in size by acquiring genes from chromosomes, although these events have been much less well studied. These transformations highlight the plasticity of plasmid architecture and raise intriguing questions about the evolutionary pressures driving these changes.

In summary, plasmids are central players in bacterial evolution, not only because of their genetic content but also due to the varied mechanisms by which they move between hosts. While classical modes of HGT—conjugation, transformation, and transduction—have long defined our understanding of plasmid dissemination, it is now clear that many plasmids exploit additional, often unconventional, strategies to ensure their mobility. This includes mechanisms of communication or sensing the environment and the microbial community for potential hosts and competitor plasmids. We refer to this broader repertoire as the extended mobility of plasmids—a concept that encompasses the full diversity of mechanisms allowing plasmids to disseminate across microbial communities.

The mechanics, physiology, and diversity of conjugation

Conjugation from the side of the donor cell is primarily driven by self-transmissible MGEs that encode the machinery necessary for DNA processing and transfer. The ‘shoot and pump model’ is still used to illustrate the basic steps in conjugation [28] (reviewed in [2, 29]). The plasmid journey toward a new host cell has several critical steps and bottlenecks, encompassing exploration and contact initiation, invasion, establishment, control, and assimilation (reviewed in [30]). The process begins with the formation of the relaxosome, a multiprotein complex associated with the origin of transfer (oriT) on the plasmid. A key component is the relaxase enzyme, which nicks one strand of the plasmid DNA at the oriT site and forms in most cases a covalent bond with the 5′ end of the nicked DNA. The relaxase-DNA complex is then transported to the recipient cell through a Type IV secretion system (T4SS), a multiprotein apparatus that spans the donor’s inner and outer membranes also called Mating Pair Formation (MPF) system. Coupling proteins within the system ensure that the relaxase and its attached DNA are recognized and translocated by the T4SS. The structures of several T4SS involved in conjugation were recently revealed, providing clues on their similarities, differences and assembly processes (reviewed in [31, 32]). The most frequent localization of the F-plasmid transfer machinery in donor Escherichia coli cells is on the side at quarter positions [33]. Its conjugative pili are highly dynamic structures capable of extending and retracting to form contacts with potential recipients probing a volume around the cell that can exceed 100 times the one of the cell itself [30]. A longstanding controversy surrounded the transfer of the DNA through the conjugative pilus, when there is one. Live-cell microscopy has finally allowed to settle it by demonstrating that the F pilus serves as a conduit for DNA transfer during conjugation between physically distant bacteria [34–36].

The acquisition of plasmids by the recipient cell is less well understood. The F-plasmid DNA tends to arrive at the polar regions of the recipient cell [33]. Once in the recipient cytoplasm, the single DNA strand is circularized and serves as a template for replication and establishment of the full double stranded DNA plasmid. Direct visualization of F plasmid conjugation revealed that conversion of the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) into double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) is fast and occurs at specific subcellular localizations [33]. This conversion determines the timing of production of most plasmid-encoded proteins that are only expressed if the DNA is double stranded. Yet, the leading strand incoming region of some plasmids contains single stranded promoters, allowing immediate expression of certain genes [33, 37, 38] (see below for implications in plasmid defense). The full process of plasmid acquisition has costs that are still poorly understood and should not be mistaken for the costs of subsequent carriage. Some of these acquisition costs are associated with the activation of responses to the incoming ssDNA, e.g. the SOS response [39]. Other costs are more drastic, involving recipient cell death by lethal zygosis. This process was observed in matings involving donors with the integrated F plasmid (Hfr strains) [40, 41], and more recently with plasmids RP4 and R388 [42]. A combination of modeling and experiments revealed a tradeoff between the lag time a recipient cell requires to recover from conjugation and its subsequent growth rate [43], where bacteria with longer lag phases end up having higher growth rates. This results in unexpected ecological dynamics, where plasmids with intermediate fitness costs can outcompete both low- and high-cost variants. These intriguing results highlight that we need a deeper comprehension of plasmid acquisition costs [44] to better understand the spread of plasmids in microbial populations.

If the machinery is available, conjugation is a robust process that does not require gene expression to occur. This is why dead donors can conjugate, although relatively poorly [45]. The recipient cell provides the machinery for plasmid establishment and replication and does not strictly require specific nonessential genes for plasmid acquisition [46], unlike in natural transformation. Nevertheless, the efficiency of conjugation is profoundly influenced by environmental conditions such as nutrient availability, temperature, and stress factors including antibiotics (reviewed in [15, 47]). Conjugation rates are heterogeneous even within clonal populations, driven by variations in plasmid expression and host factors [48, 49].

Novel approaches are shedding light on the dynamics and environmental dependencies of plasmid conjugation. The use of time-lapse fluorescence microscopy revealed that conjugation events are not uniformly distributed within bacterial populations; rather, they occur in spatially confined ‘hotspots’ where donor and recipient cells form transient but highly efficient transfer clusters [36]. These findings challenge the traditional view of random plasmid transfer and suggest that microenvironmental factors and cell-to-cell interactions play crucial roles in shaping conjugation networks. Plasmid invasion by conjugation in biofilms depends on local cell densities where spatial proximity of bacteria facilitates transfer [50]. Social behaviors, like quorum sensing, regulate the expression of conjugation machinery in donors (reviewed in [51, 52]). Importantly, recent work indicates that at high cell densities conjugation becomes limited by engagement time rather than merely by the frequency of donor–recipient encounters [53]. Additionally, the presence of external stressors, such as sub-lethal antibiotic concentrations, can trigger plasmid-mediated stress responses, promoting conjugative activity [54, 55]. Studies with clinical plasmids revealed the key role of plasmid evolution within specific genetic backgrounds in shaping their rates of transfer [56]. Finally, as described more abundantly below, the transfer of conjugative plasmids is affected by cells’ MGEs, and notably by the presence of other plasmids [18, 21, 57].

Conjugation systems are very ancient and phylogenetic reconstructions of the T4SS suggest they originated in diderm bacteria [58]. Their diversification has created lineages that are broadly associated with bacterial super-phyla (left panel of Fig. 2). This means that while transfer of conjugative plasmids across phyla has been observed, the successful establishment of such plasmids is rare. Four MPF types are found in Pseudomonadota (previously Proteobacteria) and closely related phyla (F, I, T, G), one system is specific to Cyanobacteria (C) and another to Bacteroidota (B), two others being found among monoderms (Bacteria and Archaea: FA, FATA). These studies suggest that diderm T4SS were initially co-opted by bacterial monoderms from where they were subsequently transferred to Archaea. More recently, several conjugative T4SS were co-opted to secrete virulence factors into eukaryotes in bacterial pathogens [59] or toxins into competing bacteria [60] (reviewed in [61]). Some of these systems perform both functions (conjugation and secretion of effectors) [62]. It is important to note that the transfer channel encoded by plasmid F (MPFF), which has been the basis for many cellular studies, differs significantly from that of plasmid R388 (MPFT), the primary model for structural studies (Table 1). MPFF is genetically more complex than MPFT and their functions may differ markedly. For example, R388 conjugative pilus is not able to retract [63]. In some Firmicutes, conjugation does not require a pilus and uses aggregation proteins to keep cells in direct contact [64]. Of importance, a given relaxase can interact with different types of MPF systems [65, 66], resulting in diverse patterns of co-occurrence between types of mobilizable and conjugative plasmids (right panel of Fig. 2) and suggesting, at best, some loose co-evolution between the relaxase and the T4SS. In contrast, there is tight co-evolution between oriT and the cognate relaxases, since only relaxases with relatively high protein identity seem to recognize a given oriT [67]. Further research is needed to determine whether the dynamics observed in conjugative systems of types MPFF and MPFT apply to the many other systems that remain poorly known. These diverse MPF types have variable components of which few have identifiable homology across types [68]. Comparative studies across these systems will be essential in revealing their structural, mechanistic, and functional diversity.

Figure 2.

Association between relaxase MOB classes and MPF systems. Left panel: The schematic phylogenetic tree illustrates the evolutionary relationships between MPF types based on the VirB4 phylogeny, highlighting their diversification within diderms and subsequent transfer to monoderms. Examples of conjugative systems representing each MPF type are displayed at the right. The phylogenetic tree was adapted from [58]. Right panel: The chord diagram displays a ring featuring the nine relaxase MOB classes and eight MPF types. The width of each sector corresponds to the abundance of MOB or MPF in an NCBI dataset of 12 148 plasmids. Links indicate co-occurrence of MOB and MPF within the same plasmid. The data were taken from Supplementary Table S1 of [27].

Table 1.

Widely used model mobile plasmids

| Plasmid | Size (bp) | PTU | MOB class | MPF type | Mobility type | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ColE1 | 6646 | PTU-E1 | MOBP | - | Mobilizable | ColE1 plasmid family oriV is the basis for many modern cloning and expression vectors, including those for eukaryotic transfection; replication and mobilization extensively studied; model for antisense RNA-based regulation of plasmid replication |

| RSF1010 | 8688 | PTU-Q1 | MOBQ | - | Mobilizable | Broad host range plasmid; replicates in many Gram-negative and some Gram-positive bacteria; replication and mobilization extensively studied; model for strand-displacement replication mechanism |

| pMV158 | 5541 | - | MOBV | - | Mobilizable | Broad host range; replicates in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria; replication and mobilization extensively studied; model for rolling-circle replication plasmids |

| pBBR1 | 2687 | - | MOBV | - | Mobilizable | Broad host range plasmid; replicates in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria; engineered for constructing shuttle vectors |

| F | 99 159 | PTU-FE | MOBF | MPFF | Conjugative | Classic model for conjugation in E. coli; the mini-F replicon is used in bacterial artificial chromosomes and bacmids |

| RP4 | 60 099 | - | MOBP | MPFT | Conjugative | Broad host range conjugative plasmid; its oriT is used in shuttle vectors to transfer DNA between different bacterial phyla via conjugation; its replication, conjugation, and regulatory networks have been widely studied |

| R388 | 33 913 | PTU-W | MOBF | MPFT | Conjugative | Broad host range conjugative plasmid; its conjugation, regulatory networks, and segregation have been widely studied; model for structural biology studies on conjugative systems |

| R46 | 50 969 | PTU-N1 | MOBF | MPFT | Conjugative | Broad host range conjugative plasmid; its derivative, pKM101, has been widely studied for its conjugative transfer and error-prone DNA repair capabilities |

| R64 | 120 826 | PTU-I1 | MOBP | MPFI | Conjugative | Model for shufflon and type IV pilus role in conjugation |

| pTi-C58 | 214 233 | PTU-Rhi10 | MOBQ, MOBP | MPFT, MPFT | Conjugative | Natural tool for gene transfer to plants |

| pOXA-48 | 61 881 | PTU-L/M | MOBP | MPFI | Conjugative | Clinically relevant carbapenem-resistant plasmid; plasmid-associated fitness cost and transmission in hospital settings have been extensively studied |

| R27 | 180 461 | PTU-HI1A | MOBH | MPFF | Conjugative | Model for thermosensitive conjugative transfer |

| pIP501 | 30 599 | - | MOBV | MPFFATA | Conjugative | Model conjugative plasmid from Gram-positive bacteria; broad host range, replicates in many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria; replication and conjugation have been extensively studied |

| pCF10 | 67 673 | PTU-Lab36 | MOBP | MPFFATA | Conjugative | Model for pheromone-inducible conjugation |

| pMW2 | 20 650 | - | - | - | pOriT | Example of pOriT plasmids |

| N15 | 46 375 | - | - | - | Prophage-plasmid (P-P) | Model for linear P-P |

| P1 | 94 800 | PTU-Y | - | - | P-P | Model phage-plasmid; widely used to transfer segments of the E. coli genome between strains via transduction |

When plasmids are also phages

Bacteriophages (phages) are bacterial viruses. They can be made of RNA, ssDNA or, more commonly, dsDNA [69]. Phages produce viral particles where they can package their own DNA. Upon infecting a sensitive bacterial cell many dsDNA phages (called temperate) make a lysis-lysogeny decision by either immediately producing progeny (lysis) or integrating the bacterial genome as prophages for several generations (lysogeny). There is still a frequent misperception that temperate phages necessarily integrate in the chromosome when they integrate the genome. Yet, phage-plasmids (or prophage-plasmids, P-Ps) are MGEs that transfer between cells as phages, while remaining in genomes as prophages under a replicative extra-chromosomal state, like other plasmids (Fig. 3A, reviewed in [70]). This replicative state in lysogeny should not be mistaken for the replication stage of the phage during lytic cycle, since the former takes place only about once per replicon per cell cycle. The best studied P-P is P1, which was the first phage isolated by Bertani from E. coli (in 1951) and became a popular tool for generalized transduction in molecular biology laboratories across the world [71] (Table 1). This P-P has become a model system to study molecular processes such as restriction–modification (R–M), site-specific recombination, phase-variation, plasmid replication, and plasmid partition (reviewed in [72, 73]). The unrelated phage N15 is a model system for linear plasmids (reviewed in [74]) (Table 1). Other known or putative P-Ps include the crassphage [75], the most abundant phage family in the human gut, Borrelia burgdorferi φBB1 [76] and derivative elements which encode adhesins that are important virulence factors in Lyme disease, and Vibrio cholerae’s VP882, which is a model system for quorum-sensing mediated regulation of the lysis-lysogeny decision [77]. Like many other phages, most P-Ps produce tailed viral particles, used to package their DNA into host cells.

Figure 3.

(A) Mechanism of mobility of phage-plasmids. (B) Distribution of plasmids per type in Bacteria and in E. coli (as described in [102]): conjugative (pCONJ), mobilizable with a relaxase (pMOB), mobilizable having an oriT (pOriT, only represented for E. coli), and phage-plasmid. “?” represents other, mostly uncharacterized, plasmids. Frequency of each type among all plasmids is proportional to the surface of the rectangle. (C) Comparison of plasmid mobility by conjugation (left) or within phage particles (right). P-Ps can produce very large progeny, but at the cost of cell death. Conjugative plasmids usually have broader host ranges than temperate phages and are more tolerant to extensive gene gain or loss. P-Ps may disperse faster, especially in aquatic environments, since their transfer does not require cell-to-cell contact.

P-Ps remained in the shadow for many decades, possibly because few labs studied both phages and plasmids. Hence, where a phage biologist saw a phage that seemed to behave like a plasmid, the plasmid biologist saw a plasmid with phage-like genes. The recent increase in interest by both types of MGEs and the availability of huge numbers of bacterial genomes enabled the discovery of many novel P-Ps, which account for around 5%–7% of all sequenced plasmids and a similar fraction of all sequenced phages [17] (Fig. 3B). P-Ps encode the genetic information required to start replication of their DNA during the lytic cycle, produce phage particles, package the DNA on the viral particles and lyse the host cells. They also encode the genes for plasmid replication and partition during the lysogenic cycle, and the regulatory elements to coordinate these functions and to transition between lysogeny and the lytic cycle. No P-P has yet been found to be also conjugative. This is not overly surprising considering that no prophage integrated in a bacterial chromosome has been found to be conjugative, although it was reported that prophages may be mobilizable by conjugation encoded in integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) [78].

Most P-Ps found in current databases can be clustered in less than a dozen large families [17]. Each family is found within a bacterial genus or class, has a characteristic genome size, and equally characteristic ratios of plasmid-like and phage-like genes. This shows that many P-P families are ancient and not derived from recent fusions of plasmids and phages. Like other plasmids, their replication initiators make them unstable in the presence of closely related elements, allowing them to be grouped in incompatibility types. For example, P1 is the archetype of IncY plasmids that includes closely related phage-plasmids [79, 80]. Most of the known large families of P-Ps have at least one element that was shown experimentally to be both a temperate phage and a plasmid [17]. Yet, many small families of putative P-Ps still wait for experimental validation. It is also unclear if lysis-lysogeny decisions in P-Ps resemble those of integrative temperate phages. For example, phage lambda decision towards lysogeny is dependent on the multiplicity of infection, whereas that of P1 is independent [81]. On the other hand, both prophages start the lytic cycle upon induction with mitomycin C.

The dual nature of phage-plasmids, being phages and plasmids, has consequences for their evolution. The other plasmids rarely exchange genes with the other phages. In contrast, P-Ps often exchange genes with both other plasmids and other phages, possibly because they encode genes of both types of elements which facilitates recombination [82]. Accordingly, and contrary to other phages, a sizeable fraction of P-Ps has antibiotic resistance genes of clinical relevance, presumably acquired from conjugative plasmids [83]. These genes are transferred with the rest of the genome in viral particles and provide a resistance phenotype by lysogenic conversion. P-Ps, like other plasmids, encode a wide variety of other accessory functions that may enhance host fitness in specific circumstances [17, 83]. Because P-Ps are phages, and contrary to other plasmids, P-Ps actively induce cell death by lysis to disperse in the environment. A recent study revealed that recurrent loss-of-function mutations in the lytic cycle repressor of a Roseobacter P-P leads to continuous productive phage infection of the bacterial population, in which lytic and lysogenic P-Ps coexist [84]. Hence, the interplay between phage infection and plasmid genetics may result in unique outcomes for P-Ps.

Conjugation versus viral transfer

Around 25% of the plasmids in the database are conjugative and ∼5%–7% are recognizable P-Ps (Fig. 3B). Hence, P-Ps are rarer than conjugative plasmids, but not that rarer, especially considering that we may still be missing a lot of them (Fig. 3B). One must thus better understand the consequences associated with the two types of mobility, and how they shape the cost of plasmid transfer, its host range, genetic plasticity, and its ability to disperse in microbial communities (Fig. 3C).

The costs of transfer of conjugative plasmids and P-Ps are very different for the host [85]. While plasmid conjugation can be expensive because it requires the production and function of the MPF [16], and conjugative pili may increase the likelihood of phage infections [86], P-P transfer is deadly to the donor cell because, with the exception of filamentous phages, cell lysis is necessary to liberate phage progeny (Fig. 3C). This fitness effect may be less severe when lysis occurs in a small fraction of the bacterial population, allowing the survival of most lysogens. Lysis of a small subset of the population may even be favorable for the population of lysogens because the novel P-Ps may infect and kill the competitors that are sensitive to the phage (lysogens usually being protected from super-infection) [87–89].

The gains for the plasmid also differ depending on the mechanism of transfer. Each event of transfer by conjugation increases the number of plasmids in the population by one, whereas a lytic cycle produces dozens of phage particles carrying the P-P. There are thus key differences in transmission between the two types of plasmids: conjugative plasmids are less costly and reproduce at lower rates whereas P-Ps are deadly and reproduce at high rates (even if the original host dies in the process). On the other hand, conjugation delivers plasmids directly at host cells, whereas P-Ps particles still have to find a sensitive host before infecting another cell. From an ecological perspective, P-Ps generate vast numbers of progeny in a short period of time, of which only a few survive. This may provide an advantage for colonization, but a disadvantage when communities are mature. In contrast, conjugative plasmids generate a small progeny per cycle, but more of them survive because conjugation targets directly susceptible bacterial recipient cells. It is likely, even if it remains to be demonstrated, that ecological conditions determine which mechanism is most efficient for plasmid transfer.

The range of bacterial hosts permissive to plasmid transfer is much larger in conjugative plasmids than in P-Ps. Conjugative plasmids generally have broad host ranges, as shown by the fact that 81% of mobilizable and conjugative PTUs are capable of crossing genus barriers [14], even if decreasing taxonomic relatedness is associated with lower conjugation frequencies [90]. In contrast, most temperate phages have narrow host ranges, often infecting only a few strains within a species or closely related species [91]. The P1 P-P is somewhat unusual in that it was shown to infect multiple genera in Enterobacteria thanks to its encoding multiple tail fibers, the expression of which is under the control of the Cin site-specific recombinase and results in broader host range than the typical temperate phage [73]. Nevertheless, this is different from the broad host range of some plasmids (e.g. IncP-1 plasmids, [92]) where the same pilus is used to transfer plasmids into very different bacterial and even eukaryotic cells [93, 94].

The different transmission mechanisms affect plasmid genetic plasticity. In contrast to conjugative elements that may transfer vast amounts of DNA per event of transfer [95], the amount of transferred DNA by a P-P is limited by the volume of its capsid [17, 96, 97]. This constraint restricts the range of viable changes in the size of P-Ps to a few percent of their genomes, since beyond this threshold the P-P DNA can no longer fit the capsid [96, 97]. Therefore, conjugative plasmids more easily accommodate novel genes than P-Ps (Fig. 3C). For example, given the rate of conjugation of the F plasmid, an increase of 10 kb in the plasmid size, corresponding to an increase of 10% of its genome, only increases the transfer time by ca. 15 s [33, 98]. Hence, increase in plasmid size will much more likely block the transfer of P-Ps than those transferring by conjugation, which may allow the latter to vary their gene repertoires more freely.

The mechanism of mobility also shapes the patterns of plasmid dissemination (Fig. 3B). The differences between the two mechanisms in the requirement for close contact between cells, essential for conjugation, but not for phages, implicate the latter may disperse faster in the environment and quickly access distant communities. This difference in the dispersion mode may be particularly important for bacterial communities in aquatic environments, where phages are indeed exceedingly abundant [99, 100]. On the other hand, high dispersion also entails opportunity costs when the phage disperses out of a community with sensitive hosts to which it is adapted and entails risks when it ends up in habitats lacking in hosts (for a review of dispersal costs, see [101]). In conclusion, the cost, range, plasticity, and dispersion of plasmids depends on their mechanisms of mobility. This is likely to affect the accessory traits carried by plasmids because these are often associated with specific ecological conditions, although more work needs to be carried out to clarify this issue.

Hitchers

Plasmids encoding a full set of functions required for conjugation or phage reproduction are autonomous in their mobility, i.e. they only require host core functions, like transcription or replication, to transfer between cells. Yet, a majority (ca. 70%) of plasmids are not autonomously transmissible [2, 103], but can be mobilized by conjugation encoded in other MGEs (including plasmids), or by phages through transduction (Fig. 4). They are called hitchers because they require other elements to transfer (the helpers). Hitchers are not just hitchikers in that they actively attach themselves to conjugation machineries in the cell. They were extensively reviewed recently [18]. To attain a high frequency of mobility by conjugation or transduction, many hitcher plasmids evolved mechanisms to interact efficiently with the helper’s machinery (Fig. 4). For example, some encode specific relaxases and oriT whereas others encode just an oriT and all remaining machinery is provided by the helper. The consequence of these processes is that the probability of transfer of a hitcher plasmid depends on the content of the bacteria in other MGEs [18, 104]. Accordingly, plasmids in bacteria with few plasmids are conjugative, whereas bacteria with many plasmids have an over-representation of mobilizable ones [103].

Figure 4.

Mechanisms allowing the mobility of plasmids that do not encode a complete machinery for self-transfer. Mechanisms of transfer may involve mobilization by a conjugative element (top three rows) where a hitcher plasmid recruits an MPF and eventually also a relaxase from other plasmids. Phages may transfer plasmids by transduction either because they make generalized transduction and randomly package bacterial DNA in some of their capsids or because plasmids have evolved sequences to favor recognition by the phage packaging system. Plasmids may also transfer by other processes such as conduction (co-integration in a transferable plasmid), natural transformation, or within vesicles (although the latter mechanism is yet poorly understood).

Hitchers can be mobilized by conjugative helpers in three ways (upper panels in Fig. 4). In plasmids encoding a relaxase and an oriT, the relaxase interacts with the oriT of the element as described above for conjugative plasmids [105, 106]. The resulting nucleoprotein filament is then transferred by a conjugative system encoded by a helper. This process depends on the interaction of the relaxase of the mobilizable plasmid with the conjugative system of the helper. This can occur with the coupling protein of the conjugative system, or directly with the T4SS if the hitcher plasmid encodes a coupling protein [107, 108]. These physical interactions seem easy to mimic, since some mobilizable plasmids can be transferred by widely different conjugative systems [65, 108]. A more peculiar case was reported in Bacillus subtilis [109], where the ICE ICEBs1 can mobilize plasmids lacking typical conjugative relaxases, by interacting with the plasmid replicative relaxase. Other mobilizable plasmids only have an oriT for their mobility (they may encode many other unrelated genes) and are called pOriT [103, 110]. They may recruit a relaxase from a mobilizable element and a conjugative system from a conjugative element, or they may recruit both functions from the same helper. In E. coli the latter account for a little >60% of all pOriT [103]. This still leaves almost 40% of the plasmids depending on two different and compatible helpers to transfer between cells. The probability that a pOriT transfers into a cell with such a combination of MGEs is unknown, but their sheer abundance suggests that such combinations are not rare. One possibility is that plasmids are often co-transferred between donors and recipients, therefore allowing the pOriT to find the same compatible helper plasmid in the recipient. While this does not seem to have been thoroughly studied for co-transfer of hitchers and helpers, it was previously shown that different conjugative plasmids residing in the same cell tend to co-transfer [111].

Plasmids may also be mobilized by phages [19, 20], in a process called transduction [112] (Fig. 4). Generalized transduction results from a lack of specificity in the phage packaging machinery that leads to the encapsidation of random pieces of bacterial DNA. The P1 phage-plasmid is a model system to study generalized transduction and can be used in the laboratory to transduce plasmids or parts of them [113]. It was thought that generalized transduction is an inevitable “mistake” by the phage resulting from imprecise recognition of DNA sequences by its packaging machinery. Yet, recent works suggest transduction may have little cost to the phage (only a few capsids per replication cycle) and provide it with some advantages. Co-transfer of the phage and the bacterial DNA could for example allow the former to encounter in the recipient cells other adaptive functions for the host replication [114]. In this context, a low rate of transduction is no longer seen as a DNA packaging “mistake” but could instead be selected for. The intriguing similarity between the distribution of sizes of plasmids and those of phage genomes, has led to suggestions that co-occurrence of plasmids and transducing phages in the same cell often results in the transfer of the former by generalized transduction in phage capsids [20]. Transduction is especially likely for small plasmids because these will fit more easily the size of phage capsids [115] even if this may sometimes require they are packaged as concatemers [116]. It is also more frequent for high copy number plasmids because of their high concentration in cells [19].

Plasmids may further increase their rate of transduction by encoding DNA motifs similar to those used by the phages to recognize their own DNA. Some MGEs have developed this strategy to high degrees of sophistication and have become hitchers, which in this case are called phage satellites [117]. Contrary to common misperception, many satellites are not degenerate phages. Instead, they are MGEs that have evolved the ability to hijack phage particles and use them to transfer. At least one phage satellite has been shown to be a plasmid [118], but many others may exist and remain unknown. If plasmids often have phage packaging sites, it is likely that some are satellites of P-Ps.

Interactions between hitchers and helpers can diminish the latter’s capacity to transfer and pave the way to genetic conflicts. Some mobilizable plasmids can be costly to their helper conjugative elements by either diminishing or even blocking their dissemination [119, 120]. Phage satellites, by hijacking phage particles, diminish phage progeny [117]. Other hitcher plasmids have little, if any, impact in the transfer of the helper conjugative elements [110]. While mobilizable plasmids are in general smaller than conjugative ones [2, 103], there is no clear mechanistic reason for this [besides the fact that the loci encoding the transfer machinery can be large (15–40 kb)]. For example, the pSymB plasmid of Sinorhizobium meliloti is mobilized in trans by the pSymA even though it is over 1.6 Mb in length [121].

Lazy mobility

At least three other mechanisms allow plasmids to transfer between cells without having to encode specific mobility functions (“lazy” mobility, three lower panels in Fig. 4). Some plasmids can transfer by co-integrating with mobile plasmids (conduction) (reviewed in [21]). The two elements are transferred by conjugation in a single DNA molecule, a process that is different from the case of hitchers described above, where hitchers and helpers are transferred separately. Fusion between plasmids can occur by a variety of mechanisms, including the action of transposable elements [122] or homologous recombination [123]. Sometimes, these mechanisms allow the transfer of large nonmobilizable plasmids, such as the mobilization by conduction with a PTU-E21 plasmid of the large (>220 kb) Klebsiella pneumoniae virulence plasmid [124]. In the recipient cell the co-integrates may or may not reverse to the initial state, resulting in either a large recombinant plasmid or the two original plasmids. Many processes of conduction described in the literature involve integration mediated by transposable elements [125, 126]. It is not clear if conduction is a side effect of the action of these elements or if there are mechanisms that evolved specifically to facilitate conduction. It is also not clear how often the plasmid fusion may revert to the two original plasmids after transfer.

Plasmids may be present in the extra-cellular environment, e.g. following lysis of the donor cell. Recipient cells in a state of competence for natural transformation may uptake these plasmids when they attach to a structure in the cell envelope (typically to a type IV filament, for reviews, see [127, 128]). During DNA uptake by transformation, the DNA is made single-stranded and cut into fragments of a few kilobases before entering the cytoplasm. Hence, transformation of plasmids is thought to be more efficient for small high copy number plasmids [129–131], for which the likelihood of acquisition and re-assembly of the whole plasmid sequence (from one or multiple pieces) in the recipient cell is highest. While transfer of plasmids by natural transformation in the environment was described long ago [132], its importance remains unclear.

Small plasmids were also described to be transferred in outer membrane vesicles [133, 134]. This process is not yet fully understood. For example, it remains to be elucidated how plasmids arrive at the vesicle from the cytoplasm in the donor cell and from the periplasm to the cytoplasm in the recipient cell. The frequency of transfer of plasmids in vesicles seems to increase with their copy number and decrease with their size, but also depends on other unknown characteristics of plasmids [135]. Vesicles may favor transfer between neighbouring cells, since their diffusion away from cells is rare in microcolonies [136]. In summary, transfer of plasmids by transformation and by outer membrane vesicles favors small plasmids which usually have high copy number [137–139].

Is there a plasmid paradox?

Plasmids persist in bacterial populations in spite of conjugation rates that are often found to be low and costs to the host that are often high—a phenomenon termed the plasmid paradox [140–142]. The accumulation of data has started to solve the riddle (reviewed in [143]). A lot of the apparent plasmid paradox relies on the relatively low transfer rates given plasmid carriage costs observed in the laboratory. But quantifying conjugation rates in nature and their ecological implications remains challenging given the dynamic nature of microbial communities, host heterogeneity, and the regulation of conjugation [144, 145]. The quantification of plasmid carriage costs across environments is also still in its infancy. Nonetheless, recent works suggest that frequent conjugative transfer, combined with the selective advantages provided by plasmid-encoded traits, can sustain plasmid prevalence over evolutionary timescales. In support of this view, plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance was shown to remain resilient in microbial communities due to conjugation dynamics that counteract plasmid loss, even when antibiotic selection is reduced [55]. The environmental plasmid pQBR57 was shown to transfer until fixation in conditions where it provides no fitness gain [146]. This may occur even in hosts where the plasmid has low persistence by a source-sink dynamics where plasmids are constantly transmitted from hosts where their presence is stable [146, 147]. The costs of plasmid carriage are also extremely variable and this may favor their persistence (reviewed in [85]). For example, the resistance plasmid pOXA-48 (Table 1) can have widely different, positive or negative, carriage costs in the absence of antibiotics depending on the genetic background [148]. A recent analysis of 40 plasmids of clinical origin revealed that most plasmids operate at a rate of conjugation that is below the one resulting in major growth effects [149]. In nonmobile plasmids, stability may arise even in the absence of antibiotics from the coordination of plasmid gene transcription and replication dynamics [150]. These works underscore that plasmid persistence is governed by a delicate balance of conjugation dynamics, selective pressures, and host adaptation.

Transmission costs can also influence the probability of plasmid persistence in bacterial populations. MGEs are subject to virulence–transmission trade-offs, where high transmission is regarded as a marker of high virulence because of its costs [151]. Hence, plasmids with high rates of horizontal transmission will tend to have lower rates of vertical transmission. The extended mobility of plasmids shapes these trade-offs. For example, P-Ps transfer at high rates as phages and have thus a very large transmission cost, relative to conjugative plasmids, potentially resulting in very different population dynamics. Hitchers have lower transmission costs than phages or conjugative plasmids, because they use the transmission mechanisms of the helpers. The marginal costs of their transfer to the donor bacterium is thus very low [18]. Finally, the existence of multiple regulatory mechanisms favoring plasmid transfer in specific circumstances, such as high density of potential hosts, may contribute to lower transmission costs and alleviate the vertical-horizontal transmission trade-off, making the spread of plasmids across microbial populations very far from paradoxical.

Do plasmids pick their hosts, or vice-versa?

Long term plasmid survival depends on achieving a delicate balance between promoting their own transfer and minimizing the burden placed on their host [149, 152]. For example, experimental evolution of the antibiotic resistance plasmid R1 rapidly led to higher conjugation rates under appropriate selection pressure (antibiotics) and when confronted with high immigration rates of susceptible hosts, but this implicated higher costs to the carrying cells [153]. Sophisticated regulatory systems have evolved to favor plasmid mobility when it is more likely to be successful (reviewed in [154, 155]). As a result, many conjugative plasmids are naturally repressed for transfer. Recent mathematical models suggest that reduced transfer rates due to host control have limited effects on plasmid prevalence [156]. For F-like plasmids, repression of transfer operons is primarily mediated by the FinOP fertility inhibition system [157], which ensures that only a small fraction of bacterial cells harboring F-like plasmids express the genes of its conjugative apparatus at any given time. However, newly formed transconjugants are derepressed, allowing a temporary burst of plasmid transfer from these cells [158]. In competition experiments, repression of the R1 plasmid resulted in a significantly lower fitness cost to the host than the derepressed mutant [159], highlighting the advantage of repressing horizontal transfer in many circumstances. Even naturally derepressed plasmids, such as RP4 and R388 (Table 1), maintain tight control over their transfer genes, with plasmid regulators functioning in negative feedback loops [160–162]. When plasmid DNA is transferred into a recipient cell, the absence of these negative regulators triggers transient gene expression of the mobility genes. This burst facilitates rapid plasmid propagation [163], though it temporarily impairs the host’s growth rate until regulatory equilibrium is restored [161]. Other regulatory mechanisms act at the level of the MPF pilus assembly. For example, R388 pilus assembly is greatly stimulated by the presence of recipient cells, through mechanisms that remain to be determined [63].

Some conjugative elements use sophisticated cell-cell communication systems to express the functions necessary for transfer when recipient cells lacking the element are abundant (reviewed in [164, 165]). The Rhizobium leguminosarum symbiotic plasmid pRL1JI responds to the high concentration of an N-acyl-homoserine lactone by inducing conjugation [166]. Enterococcus faecalis produces a specific pheromone whose concentration is thus a proxy for cell concentration. Plasmid pCF10 inhibits both pheromone activity and its export by E. faecalis [165] (Table 1). In these cases, conjugation will preferably take place when potential recipient cells lacking the plasmid are abundant relative to those carrying the plasmid [167, 168]. The ICE ICEBs1 also employs intercellular peptide signaling to regulate excision and mating under conditions that optimize its transmission efficiency [169]. It encodes an activator of excision and transfer, and a peptide that inhibits this activity. Coordinated regulation ensures ICEBs1 excision and transfer when host cells are surrounded by potential recipients that lack the element. Recent works have shown similar strategies in many conjugative plasmids [170] and temperate phages, including phage-plasmids [171], which can regulate the lysis-lysogeny decision using quorum-sensing [172, 173]. Upon infecting a new host cell, the Vibrio parahaemolyticus temperate phage-plasmid φVP882 assesses host cell density to make the decision whether to lyse or lysogenize. It shows a strong preference for establishing lysogeny at low cell density, when hosts are potentially rare, while favoring host cell lysis at high cell density [77, 174], when future hosts may be more abundant. Other mechanisms also favor plasmid transfer between closely related bacteria. This is the case of natural transformation that can be regulated by quorum-sensing mechanisms [175] or by the recognition of species-specific motifs in the incoming DNA [176, 177].

A recent meta-analysis highlighted the key role of the recipient cell in determining the rates of transfer [47]. Accordingly, mechanistic studies have shown how the composition and physiological state of the recipient cell envelope influences the success and specificity of plasmid transfer. Early studies identified the outer membrane protein OmpA and core lipopolysaccharide (LPS) as critical factors in recipient cells for acquiring F plasmids via conjugation, particularly under liquid culture conditions [46, 178]. These effects are less important for other plasmids like R100-1 [179] or R388 [46]. Capsules were recently shown to negatively affect plasmid conjugation rates [180–182]. The effect is symmetric, similar in the donor and in the recipient cells, and increases in direct relation to the capsule volume [183], likely because larger capsules physically separate bacteria, hindering plasmid transfer. MPFF plasmids, which encode longer retractable pili, seem unaffected by the capsule suggesting that barriers to conjugation may be surpassed by some types of MPF [183]. Conjugation of ICEBs1 into B. subtilis is influenced by the phospholipid composition of the donor and recipient cell membranes [184, 185], while wall teichoic acids were found to be essential in both donor and recipient cells for efficient transfer [186]. The impact of the cell envelope is even more crucial for the transfer of DNA in phage particles. In tailed phages, such as most P-Ps, tail fibers or other receptor binding proteins interact specifically with receptors at the cell envelope [187]. If this interaction does not take place, e.g. because the receptor is lacking, mutated or hidden, the phage cannot infect the cell [91]. Hence, P-Ps target specific types of cells, which limits their host range even when, as mentioned above for P1, they have multiple variants of tail fibers. For example, the prophages induced from K. pneumoniae tend to infect bacteria with the same capsule serotype [188]. Hence, key traits of the cell envelope, such as LPS and capsule serotypes, shape the plasmid transfer network and their effects depend on the specific mechanisms of transfer.

Some outer membrane proteins from recipient cells play a crucial role in mating pair stabilization, enhancing DNA transfer [178]. TraN, an outer membrane protein encoded by F-like plasmids, is a key player in the process of mating pair stabilization by converting initial pairings with OmpA and LPS into stable complexes capable of resisting shear forces (the so-called kissing complex) [189, 190]. The interaction of TraN with OmpA takes place at its N-terminal domain [191], where structural variations across different F-like plasmids are primarily located [192]. These variations define four distinct TraN structural variants, each specifically interacting with a different outer membrane receptor in recipient cells (OmpA, OmpW, OmpK36, and OmpF) (upper panel of Fig. 5). Minor variations in the recipient outer membrane porins can profoundly affect conjugation efficiency and specificity [192, 193]. By stabilizing mating pairs, these interactions facilitate DNA transfer. Moreover, TraN variants tend to be associated with certain species, indicating that mating pair stabilization plays a role in shaping the plasmid transfer networks [192] (recently reviewed in [23]).

Figure 5.

Interacting partners that promote targeted conjugation. The left part of the panels represents conditions where conjugation is promoted, while the right part includes scenarios where conjugation is impeded. The upper panel shows the interaction between TraN and a specific Omp versus nonspecific partner. The middle panel depicts the interaction of a specific PilV adhesin with a compatible LPS versus an incompatible LPS. The lower panel illustrates the plasmid transfer to an empty recipient versus a recipient already containing a copy of the plasmid.

Some plasmids have evolved other strategies to facilitate their transfer to specific recipient cells and to quickly adjust their specificity. Donor cells bearing plasmid R64 (Table 1) show recipient specificity during liquid mating, with transfer frequencies varying significantly depending on the combinations of recipient bacterial strains and the C-terminal segments of the PilV adhesin of the donor cell’s Type IV pilus [194, 195] (middle panel of Fig. 5). These segments recognize distinct core regions of the LPS on the surface of recipient cells during liquid mating [196, 197]. PilV variants arise through site-specific recombination mediated by the Rci recombinase, a member of the tyrosine site-specific recombinase family (reviewed in [198]). This system, called shufflon, has been identified in PTU-I1 [199], PTU-I2 [200], and PTU-B/O/K/Z [201, 202] plasmids, all of which encode a type IV pilus required for liquid mating in addition to the conjugative pilus [203]. Multiple shufflon arrangements are detectable even in plasmid DNA isolated from a culture derived from a single colony [204], suggesting that donor cells rapidly switch PilV variants to adapt to suitable recipient cells.

Targeted conjugation by selective recognition of compatible recipients serves to identify incompatible recipients, such as those already carrying a copy of the plasmid. Exclusion occurs in two forms: entry exclusion, which blocks DNA translocation into the recipient cell; and surface exclusion, which prevents cell to cell contact, thereby destabilizing the mating pair [205] (see lower panel of Fig. 5). A different strategy, immunity against superinfection, is common among temperate bacteriophages [206]. For example, the P1 P-P impedes the entry of similar elements in the cell [207]. Similar strategies were reported for ICEBs1 [208]. Genes responsible for both types of exclusion are encoded within the transfer region of the conjugative element (reviewed in [209]). Entry exclusion is mediated by an inner membrane protein in the recipient cell [210–214]. In some cases (e.g. R27 and pKPC_UVA01), this protein must also be present in the donor cells [211, 215]. The donor cell partners are all VirB6 homologs: TraG for elements encoding a type F mating pair formation (MPFF) [216–219], TraY for MPFI-encoding elements [220], and ConG for ICEBs1, which harbors MPFFA [221]. Exclusion is typically highly specific to its cognate plasmid, though exceptions exist [215].

Surface exclusion is restricted to a subset of MPFF plasmids [205, 211–223]. It is mediated by the outer membrane protein TraT, which functions in the recipient cell. Subtle amino acid variations influence the specificity of the protein in surface exclusion [224]. In F-like plasmids, surface exclusion specificity has been attributed to interactions with different proteins: the tip of the pilus on the donor cell, which may block its engagement with a receptor site on the recipient cell surface [225]; and OmpA in the recipient cell, which could potentially mask its interaction with the donor partner [226]. In PTU-C plasmids, TraN, located in the donor cell, has been identified as the surface exclusion target [223], but it does not serve this role in F-like plasmids [190]. Recently, cryo-electron microscopy structures of the surface exclusion protein TraT from pKpQIL and the F plasmid were determined [227], but their exact mechanism of action has yet to be elucidated. Pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmids exhibit a different type of surface exclusion. In these plasmids, a surface-exposed protease protrudes far out from the cell wall, reducing aggregation and transfer through the activity of the protease domain [228].

All these studies show that, although pervasive, conjugation does not occur indiscriminately. Instead, there are characteristics in the conjugative pilus, in phage particle, in the recipient or in the donor cell that shape the success and the efficiency of transfer. So, do plasmids pick their hosts? Or are they just constrained in their transfer to novel hosts? It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the two hypotheses: whether plasmids select for specific conditions and targets of transfer or whether they face obstacles to transfer in the other conditions. For some mechanisms the answer seems to fall within the hypothesis that plasmids exert a choice, e.g. the use of quorum-sensing mechanisms to decide when to transfer (by phage-plasmids or conjugative plasmids). In contrast, the phage-plasmid dependency on cell receptors is more usually regarded as a constraint because phage attachment is strictly necessary for infection. In many cases the answer may be mixed, requiring further studies from the angle of evolutionary biology. A promising case of plasmids exerting a partner choice to conjugate concerns the Tra–Omp interactions described above. In this case, the specificity of the interactions changes a lot across plasmids [192], suggesting that high specificity evolved to allow the plasmid to actively pick specific hosts for conjugation. The matter of mating choice has implications for understanding the evolution of plasmid host range in natural populations and for predicting the evolutionary paths of synthetic plasmids (and assess their risks). Such plasmid–host associations operate through a key-lock mechanism, where plasmids evolve specific traits (the “keys”) to recognize and transfer into compatible recipient cells (the “locks”). In turn, recipient cells present structural and physiological features that determine which plasmids they can accept or exclude. This interaction can be viewed from two perspectives: either plasmids actively “pick” suitable hosts through targeted mechanisms, or recipient cells effectively “select” which plasmids they acquire based on compatibility constraints. In this framework, both plasmids and hosts exert agency in shaping HGT outcomes.

Plasmid antagonistic interactions

Plasmids can be costly to bacteria [85], and may compete with other MGEs. As a result, many bacteria evolved mechanisms to counter plasmid transfer. Some target plasmids specifically, but the majority also blocks other MGEs and virulent phages (extensively reviewed in [229, 230]). Here, we will focus specifically on the known impact of these systems on plasmid transfer. R–M systems were the earliest recognized barrier to DNA entry [231] and are the most widespread bacterial defense mechanisms [232]. Types I, II, and III R–M systems encode both a methylase and an endonuclease function, with the latter targeting unmethylated DNA [233]. In contrast, type IV systems encode an endonuclease that targets modified DNA [234]. In all cases, R–M functions as an innate immune response, as it does not distinguish among MGEs nor does it learn from past encounters. R–M reduces plasmid transfer up to 105-fold [235], but only when donor and recipient bacteria have different epigenetic markers, e.g. different patterns of DNA methylation. Hence, bacteria with compatible R–M systems exchange more genetic material than those with incompatible ones [236]. The level of restriction-based defense correlates with the number of recognition sites present on the plasmid [235]. Small plasmids tend to avoid restriction sites, thereby evading restriction [237]. In contrast, some large plasmids, for which full avoidance of restriction-sites is difficult to attain, encode orphan DNA methylases [237], which facilitate plasmid establishment in new hosts by inhibiting restriction enzyme activity [235, 238, 239] [first panel (left) of Fig. 6]. Interestingly, recent studies suggest that R–M targets are depleted in the leading regions of conjugative plasmids [240].

Figure 6.

Antiplasmid defense systems and plasmid antidefense systems. The first panel illustrates the action of plasmid-encoded methylases (left) and antirestriction proteins (right) in protecting the transferred DNA from the restriction activity of R–M systems in the recipient cell. The second panel depicts the antiplasmid immunity activity of CRISPR-Cas systems (left) and the antidefense activity of Acr proteins (right). The third panel shows the defense systems pAgo/DmdDE and DmdABC (Lamassu) (left) and the fertility inhibition activity exerted by a plasmid against the transfer of a co-resident plasmid (right). The fourth panel represents the counterattack deployed by T6SS against bacteria harboring conjugative plasmids (left) and the repression of chromosome-encoded T6SS by a transcription factor encoded in the conjugative plasmid (right).

R–M systems are encoded in approximately 3.1% of the plasmids [237]. These R–M systems can promote post-segregational killing of the host cell when the plasmid encoding them is displaced by an incompatible plasmid lacking the same R–M system [241]. Similarly, plasmids carrying toxin–antitoxin systems reduce the transmission of incompatible plasmids lacking such post-segregational killing systems [242]. Cell death eliminates both the competitor plasmid and the host, thereby favoring the persistence of plasmids encoding the post-segregational killing system [243].

CRISPR-Cas are adaptive immune systems that store small sequences (spacers) from previously encountered MGEs (protospacers) in an array (the CRISPR) [244]. This array is then used to recognize further infections. The majority of CRISPR spacers with known protospacers originate from bacteriophage and prophage sequences, while nonviral spacers predominantly derive from gene families involved in conjugative transfer and plasmid replication [245] [second panel (left) of Fig. 6]. Plasmid protospacers are unevenly distributed over plasmid regions, exhibiting higher frequency in the genes encoding mobility, a pattern that varies with the MOB type [246]. A class 1, type III-A CRISPR-Cas system from Staphylococcus epidermidis was the first shown to provide sequence-specific immunity against both phages and incoming plasmids via conjugation and transformation [247]. Plasmid clearance occurs through transcript depletion and plasmid DNA degradation [248–250]. Similarly, a class 2, type II-A CRISPR-Cas system in Streptococcus thermophilus was shown to induce plasmid loss [251], demonstrating for the first time spacer acquisition in response to plasmid invasion and in vivo CRISPR RNA (crRNA)-guided cleavage of dsDNA. The impact of CRISPR-Cas on HGT is undetectable at large time scales, possibly because it is a specific system that will only target a small number of MGEs at a given time [252, 253]. Yet, certain CRISPR-Cas systems are associated with reduced gene gain rate and low MGE abundance [253, 254]. There are also contradictory results concerning their effect on the spread of antibiotic resistance [255–258].

The first functional evidence of a type IV CRISPR-Cas system revealed that Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA83 uses crRNA-guided interference to clear plasmid DNA and block its uptake in vivo [259]. This CRISPR-Cas type is nearly exclusively associated with plasmids and its spacers show a pronounced preference for plasmid-derived protospacers. This suggests that type IV CRISPR-Cas systems specialised in mediating conflicts between plasmids [260–263]. Type IV systems lack the adaptation module responsible for spacer acquisition and the effector nuclease [262]. Nevertheless, they can leverage the host CRISPR-Cas adaptation machinery to modify the plasmid CRISPR array [264]. Unlike other CRISPR-Cas systems, its interference mechanism does not rely on cleavage of the targeted DNA but functions similarly to dead Cas9 [265, 266]. In this system, the Csf4/DinG helicase binds the dsDNA-bound complex and unwinds target DNA [259, 267], which blocks the DNA from interacting with gene expression machineries, negatively affecting plasmid transfer and stability. This effect is especially pronounced when core plasmid functions are silenced, thereby limiting plasmid transfer [264]. Other CRISPR-Cas systems are enriched in plasmids (reviewed in [268]). Among them, type V-M has been shown to inhibit plasmid replication by repressing transcription of essential plasmid genes, without cleaving the target DNA [269].

Several defense systems discovered in the last few years target plasmids with different degrees of specificity. For example, the prokaryotic Argonaute (pAgo) system degrades multi-copy DNA [270], which includes many small plasmids [178, 179] [third panel (left) of Fig. 6]. More specific systems have been found in pandemic V. cholerae strains, which are often, but not always [271], devoid of plasmids [272, 273]. In V. cholerae O1 El Tor, small, multicopy plasmids were found to be unstable, a phenomenon attributed to two DNA-defense modules: Lamassu/DmdABC and DmdDE [274]. The production of DmdABC causes significant but incomplete plasmid loss, whereas DmdDE leads to rapid and complete plasmid elimination through DNA degradation. The DmdABC system also induces plasmid-dependent cell toxicity in the presence of large conjugative plasmids, resulting in their loss [274]. Stem-loop hairpin structures in plasmids were identified as triggers of DmdABC activity, leading to bacterial death [275] [third panel (left) of Fig. 6]. Other proteins belonging to the SMC family, the one of DmdC, have been identified as antiplasmid defense systems, e.g. by inhibiting plasmid segregation [276]. Another system similar to the SMC complex, the Wadjet system, protects B. subtilis from plasmid transfer [277], by identifying and cleaving closed-circular DNA <100 kb [278]. In Corynebacterium glutamicum, Wadjet affects the maintenance of low-copy-number plasmids through its nuclease activity [279]. DNA loop extrusion promotes selective restriction of plasmids by Wadjet [280, 281], (recently reviewed [282]). The DmdDE system protects against plasmids through DNA-guided DNA targeting by the pAgo protein DmdE and subsequent degradation by the helicase-nuclease [282–285]. This type of plasmid instability may have consequences for AMR dissemination, as it indirectly favors the mobilization of plasmid-encoded AMR genes to the chromosome, thereby further stabilizing the resistance genes [216, 286]. These works revived significant interest in plasmid-specific defense systems and the next few years will likely reveal novel ones, especially with the advent of artificial intelligence-assisted defense prediction tools [287, 288].

A peculiar type of antiplasmid transfer mechanism is provided by type 6 secretion systems (T6SS), contractile injection machines that deliver toxins into target cells [289]. The P. aeruginosa H1-locus T6SS launches a lethal counterattack targeting conjugating donor cells carrying the broad-host-range IncP-1 conjugative plasmid RP4 or the PTU-N1 plasmid pKM101 [290] (Table 1). This tit-for-tat response is triggered by the MPF system encoded by conjugative plasmids in the donor cell [fourth panel (left) of Fig. 6]. In this specific case, the social interactions between bacteria directly shape the success of plasmid transfer. In another context, the anticonjugation activity of T6SS is counterbalanced: multidrug resistance plasmids of Acinetobacter baumannii encode transcriptional repressors of the chromosomal T6SS [291]. As a result, these potential conjugation donors are less effective predators, thereby facilitating plasmid transfer [fourth panel (right) of Fig. 6].

Other plasmid conflicts are mediated by fertility inhibition systems distinct from FinOP. They interfere with the transfer of a co-resident plasmid and may thus serve as competitive tools for colonizing new hosts (reviewed in [292]). These diverse fertility inhibition factors operate at different levels, but their mechanisms of action remain controversial [293–295] [third panel (right) of Fig. 6].

Research in the last few years revealed strong linkage between defence systems and MGEs: many of the defence systems found in bacterial genomes are actually encoded within MGEs and are thus implicated in MGE–MGE interactions (reviewed in [296]). As a result, while individual defence systems may diminish plasmid transfer, their presence at high frequency may be caused by the presence of plasmids. This may explain why associations between horizontal gene transfer and the presence of defense systems in bacterial genomes are taxa-dependent and in many cases non-significant [253].

Plasmids strike back

Plasmids have evolved numerous responses to defense systems encoded by bacteria or other MGEs [297]. Many of them are recorded in databases such as dbAPIS [298] and AntiDefenseFinder [299], which serve as tools to detect and annotate homologous antidefense systems. Genes known as “alleviation of restriction of DNA” or ard genes (reviewed in [300]), block the restriction sites [301] or inhibit the enzymes that restrict DNA, either by DNA mimicry [302] or by depleting the nuclease through ClpX [302, 303] [first panel (right) of Fig. 6]. One of the earliest known antirestriction systems is DarAB encoded by phage-plasmid P1 [304]. Initially identified in phages and prophages [305], anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins have been detected in diverse plasmids [306, 307]. Acrs exhibit a variety of inhibitory mechanisms, including blocking crRNA loading, preventing target DNA recognition, and hindering DNA cleavage (reviewed in [308]) [second panel (right) of Fig. 6]. A different host defense evasion (hde) mechanism was identified in PTU-C conjugative plasmids and SXT/R391 elements [309]. This mechanism promotes evasion of the type I CRISPR-Cas system in V. cholerae by repairing dsDNA breaks through recombination between short sequence repeats, similar to what occurs in the lambda Red recombination system.

Plasmid counter-defenses must act quickly upon transfer to the new bacterium. Yet, transcription of plasmid genes by conjugation usually requires conversion of the incoming ssDNA to dsDNA, which takes time. The incoming ssDNA becomes an adequate substrate for transcription by forming stem-loop structures allowing the establishment of a dsDNA-like promoter [37, 38, 310]. These single-stranded promoters enable early protein synthesis of genes located in the so-called leading region [311]. Their subsequent conversion into dsDNA turns off this unconventional form of gene expression, a process that occurs in as little as four minutes for the F plasmid [33]. The leading regions of conjugative plasmids are highly enriched with antidefense genes [312]. They include SOS inhibitors, antirestriction proteins, anti-CRISPR proteins, DNA methyltransferases, toxin–antitoxin systems, and ssDNA binding proteins. The positioning of antidefense genes in the leading region is essential for efficiently neutralizing recipient defense systems [312]. Notably, several proteins encoded in the leading region act themselves as substrates of the conjugative T4SS and are thus translocated from the donor to the recipient cell, mitigating the SOS response in the recipient [313]. Given that a significant portion of the most prevalent gene families in leading regions are still uncharacterized, it is likely that novel antidefense related functions will be discovered there in the coming years.

Fast plasmid evolution and implications for their mobility

Plasmids are particularly prone to rapid change of their gene repertoires [27]. Conjugative plasmids are more variable than ICEs [314] and P-Ps more variable than integrative prophages [17]. The extra-chromosomal state of plasmids may favor higher genetic plasticity in multiple ways (Fig. 7). First, structural modifications in plasmids are not likely to affect core chromosomal genes whose integrity and expression are under strong purifying selection. Second, plasmid copy number fluctuates more widely than that of chromosomes, with small plasmids usually having both higher copy number and higher variability in copy number than large ones [138]. High copy number provides opportunities for changes in gene dosage, recombination rates, and effective accumulation of mutations [3, 315]. All these effects spur functional innovation. Finally, and possibly because of these traits, plasmids contain a higher number of large DNA repeats, transposable elements, and integrons than other MGEs [314]. All of them promote genetic modifications [316], while facilitating gene exchange with other plasmids and the host chromosome [317–319]. The p96 plasmid of K. pneumoniae is an interesting example where genome changes result in resistance gene dosage increasing up to 58-fold by processes of tandem amplification, 89-fold by increase in plasmid copy number, or up to 172-fold by recombining with high copy number plasmids [320]. While most of these outcomes are genetically unstable in the absence of selective pressure, they may vastly accelerate antibiotic resistance by providing higher gene expression and mutation supply. Accordingly, all could be observed among plasmids of E. coli bloodstream isolates [320].

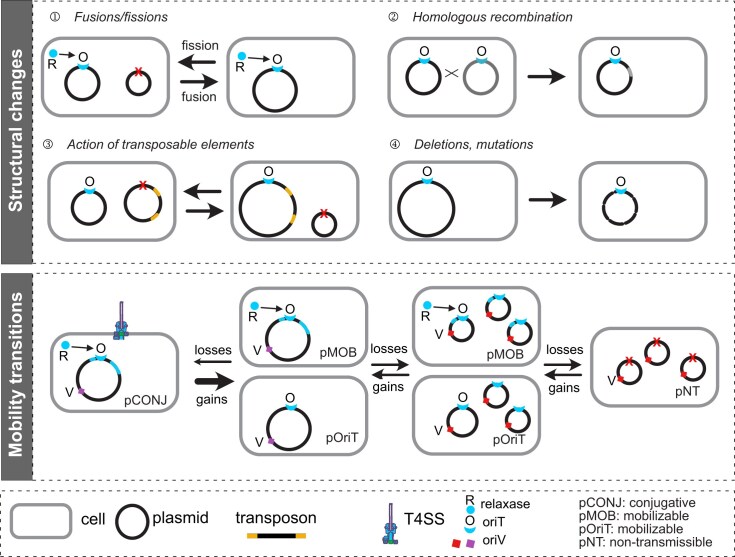

Figure 7.

Key mechanisms of genetic change in plasmids (top panel) and transitions in terms of mobility for plasmids mobilizable by conjugation (lower panel). Plasmids genomes may change by several mechanisms (top), including fusions and fissions of plasmids, recombination, translocation of transposable elements and mutations and deletions of genetic material. Successions of gene gains and losses may result in transitions between types of mobility (lower panel). Those resulting in more limited mobility are more frequent because they only require gene deletions, but available evidence suggests they are counter-selected [27].