Abstract

Immune dysfunction and late mortality from multiorgan failure are hallmarks of severe sepsis. Arginine, a semi-essential amino acid important for protein synthesis, immune response, and circulatory regulation, is deficient in sepsis. However, arginine supplementation in sepsis remains controversial due to the potential to upregulate inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-mediated excessive nitric oxide (NO) generation in macrophages, leading to vasodilation and hemodynamic catastrophe. Citrulline supplementation has been considered an alternative to replenishing arginine via de novo synthesis, orchestrated by argininosuccinate synthase 1 (ASS1) and argininosuccinate lyase (ASL). However, the functional relevance of the ASS1-ASL pathway in macrophages after endotoxin stimulation is unclear but it is crucial to consider amino acid restoration as a tool for treating sepsis. We demonstrate that lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated iNOS, ASS1, and ASL protein expression and nitric oxide generation were dependent on exogenous arginine in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Exogenous citrulline was not sufficient to restore nitric oxide generation in arginine-free conditions. Despite the induction of iNOS and ASS1 mRNA in arginine-free conditions, exogenous arginine was necessary and citrulline was not sufficient to overcome eIF2-α (elongation initiation factor 2-α)-mediated translational repression of iNOS and ASS1 protein expression. Moreover, exogenous arginine, but not citrulline, selectively modified the inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression profile of the LPS-activated RAW 264.7 and bone marrow-derived macrophages. Our study highlights the complex, differential regulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression, and NO generation by exogenous arginine in macrophages.

Keywords: cell activation, cytokines, endotoxin shock, monocytes/macrophages, nitric oxide

Introduction

Sepsis, a dysregulated host response to an infectious trigger, is increasingly recognized as a complex state of altered homeostasis of the immune system.1 Decades of attempts to translate targeted therapies from the bench to improved outcomes at the bedside failed due to the broad application of these therapies to what is now recognized as a heterogeneous syndrome.2,3 While timely resuscitation efforts have reduced the mortality of sepsis, a substantial cohort of patients survive their initial insult yet continue to suffer from chronic critical illness defined by a dysregulated and ineffective immune system and altered catabolism.4,5 A new era of critical illness research has commenced to develop more effective interventions by refining their applications based on biologic, rather than syndromic, disease classifications.6 Gene expression profiling of peripheral blood leukocytes has identified distinct subtypes of adult and pediatric patients with sepsis, with some patients exhibiting high expression of proinflammatory genes suggestive of a hyperinflammatory endotype, whereas others suffer from repression of genes involved in innate and adaptive immune functions, characteristic of an immunoparalysis endotype.7–11 Although improved stratification of septic patients has important implications for the development of precision therapeutics, much is still unknown about the underlying molecular mechanisms of these pathologically distinct conditions.

Arginine is an amino acid responsible, in part, for the induction and regulation of both the innate and adaptive immune response during sepsis. Best known for its role in the regulation of macrophages during infection, differential arginine metabolism is central to the polarization of macrophages into proinflammatory M1 and reparative/anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage subtypes. Classically defined proinflammatory M1 macrophages express inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which utilizes arginine to produce nitric oxide (NO), itself an immunoregulator and potent vasodilator, while anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages metabolize arginine into ornithine and urea via arginase 1 (ARG-1), supplying substrate for polyamine and collagen synthesis for the promotion of cell repair and regeneration.12,13 While a non-essential amino acid under physiologic conditions, arginine becomes conditionally essential in sepsis, with the degree of arginine depletion associated with mortality and severity of inflammation.14–16 Hypoargininemia of sepsis is secondary both to increased metabolism from upregulated enzymes such as iNOS and ARG-1 as well as decreased de novo production from its precursor citrulline.17–19

Manipulation of arginine metabolism as a therapeutic modality in sepsis has attracted interest for decades, though, like most potential therapies, it has largely failed in application. Studies attempting enteral supplementation of arginine in septic patients produced conflicting results, though they were confounded by supplementation of other nutritional compounds in combination or in the application of therapies to different types of critically ill patients.20 The theoretical risk of harm due to increasing substrate availability to iNOS with resultant catastrophic hyperproduction of NO and vasodilation has tempered further consideration of arginine supplementation in sepsis, with the most recent international guidelines either refraining from commenting or recommending against the use altogether.21,22 Inhibition of the arginine-consuming NOS enzymes to reduce NO production and decrease arginine metabolism initially demonstrated improved hemodynamics in patients with septic shock, though the subsequent clinical trial was stopped early after the safety review revealed excess mortality in the treatment group.23,24 Experts postulate that nonselective inhibition of all NOS isoforms disrupted the differential blood flow to organs during sepsis while acknowledging that the successful and safe therapeutic modulation of NO-arginine metabolism first requires a better understanding of the complexity of arginine regulation in sepsis.20

Citrulline supplementation is an alternative, and perhaps more effective, method of restoring arginine in sepsis through its ability to bypass metabolism by ARG-1 and iNOS and instead serve as an intracellular source of arginine, where cytosolic enzymes argininosuccinate synthase 1 (ASS1) and argininosuccinate lyase (ASL) can convert citrulline to arginine for local utilization.25–27 This pathway, known as the citrulline recycling pathway, may sustain both arginine supply and NO production, with increasing evidence to suggest a particular role for its ability to selectively support endothelial NOS (eNOS) function.28,29 The exploitation of this pathway depends on the capacities of these enzymes in cells with high arginine metabolism, though early studies report conflicting abilities of ASS1 and ASL to sustain NO production in macrophages.30–32

A precise understanding of the functional capacity of these enzymes to restore arginine for intracellular functions is crucial to the consideration of citrulline or arginine supplementation as a therapy for sepsis. Since arginine is central to macrophage immune function and sepsis is an arginine-deficient state, we hypothesize that arginine metabolism may contribute to the pathobiology of the differing immune endotypes of sepsis, though the conflicting studies evaluating the arginine metabolism in macrophages during endotoxemia hinder the development of these therapies. We, therefore, aimed to determine the effects of arginine depletion, arginine supplementation, and citrulline supplementation on macrophage activation, NO generation, and inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression in response to endotoxin treatment.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

RAW 264.7 murine macrophages (Cat no. TIB-71, ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, USA) were cultured and passaged in standard media of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 400 μM L-arginine (ARG), 0 μM L-citrulline (CIT), 4 mM L-glutamine, 4,500 mg/l glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 1,500 mg/l sodium bicarbonate (Cat no. 30-2002, ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, USA) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Cat # 30-2020, ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, USA) and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were plated in 6-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well), 12-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well), or 24-well plates (2.5 × 105 cells/well). For treatments, cells were washed twice with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and then either standard DMEM as described or L-arginine- and L-lysine-deficient DMEM for stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC, Cat no. 88364, ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) supplemented with 800 µM lysine (Cat # 89987, ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) and 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (FBS, Cat no. A3382001, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA; dialyzed to deplete arginine in the serum) was added. In total, 0 to 1,000 μM of arginine (Cat no. 88427, ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) or citrulline (Cat no. C7629, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) was then immediately added to the media. After 1 hour, cells were treated in triplicate wells per group with 0.01 to 1.0 μg/ml of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Ultrapure LPS-EB, Cat no. tlrl-3pelps, InvivoGen, San Diego, California, USA) for 30 min, 6 h, or 24 h.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages were prepared from C57BL/6J mice (8–12 wk) based on the methods described by Toda et al.33 All experiments were conducted following the National Institute of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, Texas, USA). Briefly, mice were euthanized, and hindlimbs were dissected. Bone marrow was extracted from the tibia and femur bones following the removal of surrounding muscles and soft tissue. Aseptically, bone marrow was flushed out with DMEM/F12/Glutamax media (Cat no. 10565-018, ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin using a 10 ml syringe and a 26-gauge needle. The cell suspension was filtered with a 70 μm cell strainer and plated in 10 cm Petri dishes. The culture media were spiked with mCSF (macrophage colony stimulating factor, day 0, 20 ng/ml; days 2 and 4, 5 ng/ml). On day 6, macrophages were washed with warm PBS (Ca++/Mg++ free), trypsinized, and quenched with DMEM/F12/Glutamax media containing 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin. Macrophages were collected after centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 10 min and plated in 24-well tissue culture dishes (250,000 cells per well).

After overnight incubation, cells were washed twice with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and incubated in arginine-free media (L-arginine- and L-lysine-deficient DMEM for SILAC [Cat no. 88364, ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA] supplemented with 800 µM lysine [Cat no. 89987, ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA], penicillin [100 U/ml] and streptomycin [100 µg/ml] and 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum [FBS, Cat no. A3382001, ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA]) or arginine-free media supplemented with either 250 μM of arginine (Cat no. 88427, ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) or citrulline (Cat no. C7629, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA) for 1 h prior to LPS (1.0 μg/ml; Ultrapure LPS-EB, Cat no. tlrl-3pelps InvivoGen, San Diego, California, USA) treatment for 6 h or 24 h in triplicate wells per group.

Western blot

Total protein extracts were obtained from RAW 264.7 cells treated with 0.01 to 1.0 µg/ml of LPS for 30 min or 24 h or bone marrow-derived macrophages treated with 1.0 µg/ml of LPS for 24 h by homogenizing in total lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 0.5 M NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM EDTA, 1.0% Triston X-100, 0.25% deoxycholate, 1.0 μg/ml pepstatin, 1.0 μg/ml leupeptin, 1.0 μg/ml aprotinin, 1.0 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM NaF, 2 mM activated sodium orthovanadate and 1.0 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and centrifuging at 13,500 rpm for 12 minutes at 4 °C. Equal amounts of proteins as determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois, USA) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h and immunoblotted with primary antibodies overnight, rotating at 4 °C. The following day membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) 3 times, then incubated with a secondary antibody for 1 h, rotating at room temperature. Proteins were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) and exposed to film. Band intensities were quantified by GE Healthcare Life Sciences, ImageQuant TL 1D analysis software (v8.1, Cytiva). Primary antibodies used and their respective dilutions are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibodies and dilutions used for western blotting.

| Target protein | Primary antibody dilution | Source, Catalog number |

|---|---|---|

| ARG-1 | 1:15,000 | Proteintech, 66129 |

| ASL | 1:5,000 | Proteintech, 67692 |

| ASS1 | 1:3,000 | Proteintech, 16210-1-AP |

| ATF4 | 1:1,000 | CST, 11815 |

| β-actin | 1:20,000 | Sigma, A5441 |

| eIF2α | 1:1,000 | CST, 5324 |

| p-eIF2α Ser51 | 1:1,000 | CST, 3398 |

| ERK | 1:1,000 | CST, 9102 |

| p-ERK Thr202/Tyr204 | 1:1,000 | CST, 9101 |

| IκB-α | 1:1,000 | Santa Cruz, sc-371 |

| iNOS | 1:1,000 | Abcam, 15324 |

| IRE1α | 1:250 | CST, 3294 |

| p-IRE1α Ser274 | 1:1,000 | Novus Biologicals, NB100-2323 |

| JNK | 1:1,000 | CST, 9252 |

| p-JNK Thr183/Tyr185 | 1:500 | CST, 4668 |

| NF-κB p65 | 1:1,000 | CST, 4764 |

| p-NF-κB p65 Ser536 | 1:1,000 | CST, 3033 |

| p38 | 1:1,000 | CST, 9212 |

| p-p38 Thr180/Tyr182 | 1:1,000 | CST, 9211 |

| STAT-3 | 1:1,000 | CST, 9132 |

| p-STAT-3 Ser727 | 1:1,000 | CST, 9134 |

Nitrite assay

Nitric oxide (NO) production was estimated by measuring nitrite, formed by the spontaneous oxidation of NO. Cell culture supernatants of RAW 264.7 macrophages treated with LPS (1.0 µg/ml) for 24 h were analyzed by colorimetric Griess assay kit (Cat # G7921, ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) to quantify nitrite production, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, equal volumes of N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride and sulfanilic acid were mixed to form the Griess reagent. Griess reagent (20 μl) was added to the sample (280 μl) and incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance at 548 nm was recorded on a Cytation 5 plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, Vermont, USA). Nitrite concentrations of samples were calculated based on the standard curve obtained for serial dilutions of sodium nitrite standard.

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells treated with LPS for 24 h using TRIzol reagent (ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized by reverse transcription of RNA (1.0 μg) using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). The cDNA was amplified by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) in ABI StepOne Plus real-time PCR system using SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). Quantitative expression values were determined using the ΔΔCt method as specified manufacturers using cyclophilin as a control. Primer sequences used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

DNA primers used for qRT-PCR analysis.

| Gene | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| iNOS | TCTTGGTGAAAGTGGTGTTCTTTT | AGTAGTTGCTCCTCTTCCAAGGT |

| ARG-1 | AGGAACTGGCTGAAGTGGTTA | GATGAGAAAGGAAAGTGGCTGT |

| ASS1 | CACTCTACGAGGACCGCTATCT | CTCAAAGCGGACCTGGTCATTC |

| ASL | GGCAGAGACTAAAGGAGTGGCT | TCGACACTGGATTTCGCTGTGC |

| Cyclophilin | GGCCGATGACGAGCCC | TGTCTTGGAACTTTGTCTGCA |

Cytokine and chemokine assay

RAW 264.7 and bone marrow-derived cell culture supernatants were removed after 6 h of LPS (1.0 µg/ml) treatment and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min and aliquots of supernatants were frozen at −80°C. Proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines were quantified by a Luminex xMAP technology bead-based assay using the Luminex™ 200 system (Luminex, Austin, Texas, USA) by Eve Technologies Corp. (Calgary, Alberta, Canada). Ten markers (GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, MCP-1, and TNF-α) were simultaneously measured in the samples using Eve Technologies' Mouse Focused 10-Plex Discovery Assay® (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Statistics were performed using Prism software (v7.05, GraphPad, San Diego, California, USA). Data are presented as mean values of groups of 3 independent samples with error bars corresponding to ± standard deviation. Comparisons between the 2 groups were analyzed using an unpaired Student t-test. Comparisons among multiple groups were analyzed using a 4-parameter linear regression model or 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

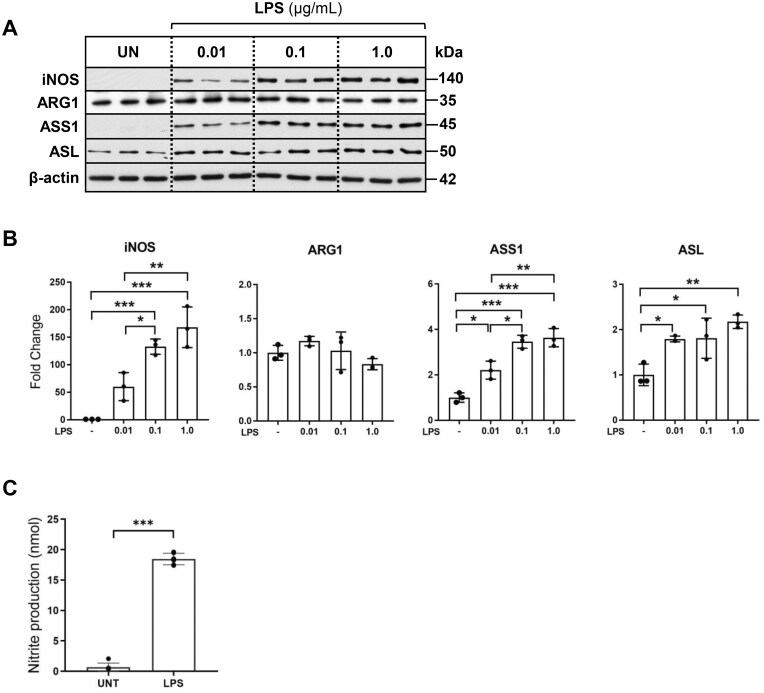

LPS treatment activates iNOS-mediated nitric oxide generation and upregulation of ASS1 and ASL expression in macrophages

First, we sought to determine the effects of LPS activation on the enzymes responsible for arginine degradation (iNOS, ARG-1) and de novo synthesis of arginine (ASS1, ASL) in RAW 264.7 macrophages under the standard cell culture conditions (DMEM, 400 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT). As expected, iNOS protein expression was undetectable in inactivated macrophages, while LPS treatment led to a robust and dose-dependent upregulation of iNOS protein expression, a hallmark of M1 polarization (Fig. 1A and B). Alternatively, ARG-1 protein expression, characteristic of M2 polarization, was not influenced by LPS treatment. ASS1, the rate-limiting enzyme in the conversion of citrulline to argininosuccinate exhibited a dose-dependent increase in protein expression by LPS. ASL, which catalyzes the conversion of argininosuccinate to arginine, was modestly elevated after 24 h of LPS treatment in our model. Corresponding to pro-inflammatory M1 polarization and iNOS protein induction, LPS (1 µg/ml) treatment led to a robust generation of nitric oxide, as assessed by the elevated nitrite levels detected in the culture media (Fig. 1C). Induction of ASS1 and ASL in LPS-activated macrophages confirmed that the key enzymes necessary for the regeneration of arginine from citrulline are intact and upregulated by LPS in macrophages.

Figure 1.

LPS treatment induces dose-dependent induction of iNOS, ASS1, and ASL protein expression in macrophages. (A) Total protein extracts of RAW 264.7 macrophages cultured in the standard media (400 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT) and treated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of LPS were analyzed by western blotting for expression of iNOS, ARG-1, ASS1, and ASL. (B) Densitometric analysis of band intensity was performed. Bar values represent the mean ± SD of n = 3/group with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 representing statistical significance as determined by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Cell culture supernatant from RAW 264.7 macrophages cultured in standard media treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 24 h was analyzed by Griess assay to quantify nitrite production. Bar values represent the mean ± SD of n = 3/group ***P < 0.001 representing statistical significance as determined by unpaired Student t-tests.

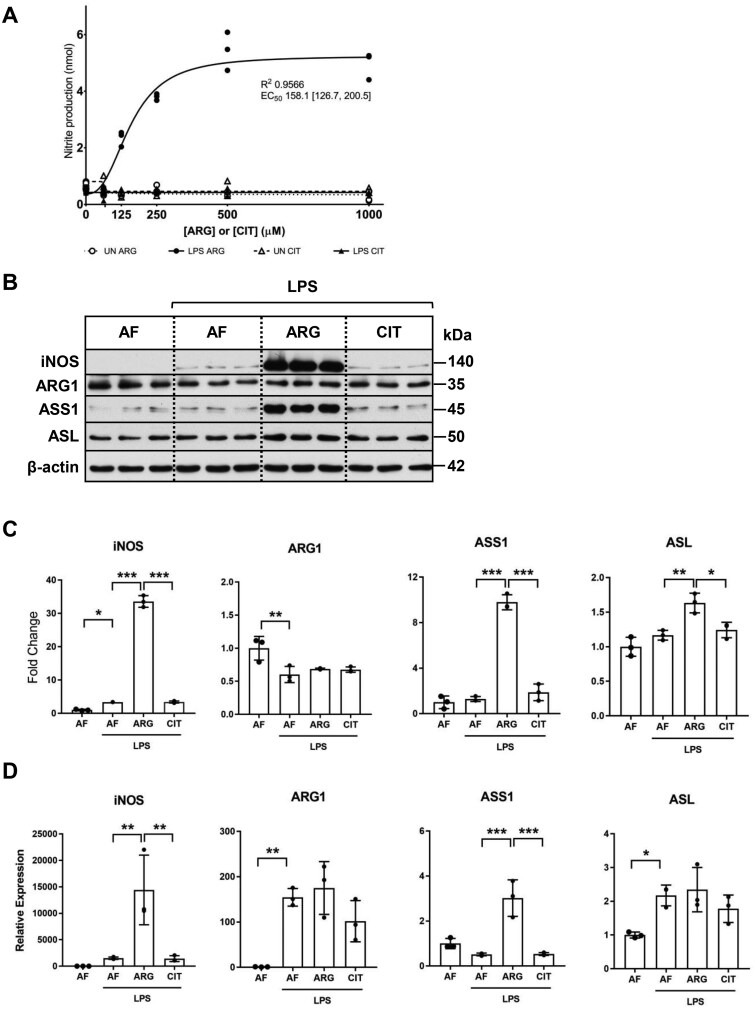

LPS-mediated iNOS protein induction and nitric oxide generation requires exogenous arginine

After establishing that both ASS1 and ASL protein expressions are elevated in RAW 264.7 macrophages in response to LPS treatment, we next aimed to determine the specific capacity of the ASS1/ASL pathway to generate arginine necessary for macrophage activation and NO generation in the absence of exogenous arginine. Our results suggest that in the absence of arginine, exogenous citrulline supplementation alone was not sufficient for iNOS-mediated nitric oxide production in activated macrophages (Fig. 2A). In the presence of exogenous arginine, macrophages exhibited the expected dose-dependent increase in nitric oxide production after LPS activation, plateauing between 500–1,000 μM.

Figure 2.

Exogenous arginine is necessary for iNOS, ASS1, and ASL protein induction and NO generation in macrophages. (A) The cell culture supernatant of RAW 264.7 macrophages cultured in arginine-free media or media with increasing concentrations of ARG or CIT (0 to 1000 μM) and treated for 24 h with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) was analyzed by Griess assay to quantify nitrite production. Graph values represent n = 3/group and EC50 and R2 values shown are representative of the 4-parameter logistic regression curve for the LPS ARG group. (B) Total protein extracts isolated from macrophages cultured in arginine-free (AF) media (0 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT) or supplemented media (125 μM ARG or 125 μM CIT) and treated with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) for 24 h were analyzed by western blotting for iNOS, ARG-1, ASS1, and ASL protein expression. (C) Densitometric analysis of band intensity was performed. Bar values rep7resent the mean ± SD of n = 3/group with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 representing statistical significance as determined by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. (D) The relative mRNA expression of iNOS, ARG-1, ASS1, and ASL was analyzed by qRT-PCR in macrophages cultured in AF media or ARG- or CIT-supplemented media and treated with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) for 24 h. Bar values represent the mean ± SD of n = 3/group with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 representing statistical significance as determined by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

Given the marked absence of nitric oxide generation in macrophages exposed to exogenous citrulline in arginine-free media, we wanted to determine if LPS-mediated upregulation of iNOS, ASS1, and ASL protein expression is dependent on exogenous arginine or citrulline. Our data suggest that LPS-mediated induction of iNOS, ASS1, and ASL protein expression was dependent on exogenous arginine (Fig. 2B and C). Curiously, citrulline supplementation alone was insufficient to support LPS-activated iNOS protein induction or the induction of the enzymes of the citrulline recycling pathway. LPS activation modestly downregulated ARG-1 protein expression in the absence of arginine. Unlike iNOS, ASS1, and ASL, LPS-mediated downregulation of ARG-1 protein expression was not influenced by exogenous arginine or citrulline. Following upon our observations that exogenous arginine is necessary and citrulline is insufficient to support LPS-mediated induction of iNOS, ASS1, and ASL protein expression, we wanted to determine if these effects are mediated via regulation of gene expression. Mirroring our observations with protein expression, exogenous arginine, and not citrulline led to a robust induction of iNOS and ASS1 mRNA expression in response to LPS treatment (Fig. 2B–D). Exogenous arginine did not influence ASL mRNA expression despite the modest elevation of ASL protein expression observed in response to LPS treatment. LPS treatment led to a modest induction of ASL mRNA expression in the absence of exogenous arginine. Interestingly, in the absence of exogenous arginine, LPS treatment led to robust induction of ARG1 mRNA expression while the ARG1 protein expression was attenuated (Fig. 2B–D). Together, these findings support the conclusion that RAW 264.7 macrophages are dependent on exogenous arginine for LPS-mediated nitric oxide production because of the requirement for exogenous arginine for both iNOS mRNA and protein induction in response to endotoxin activation.

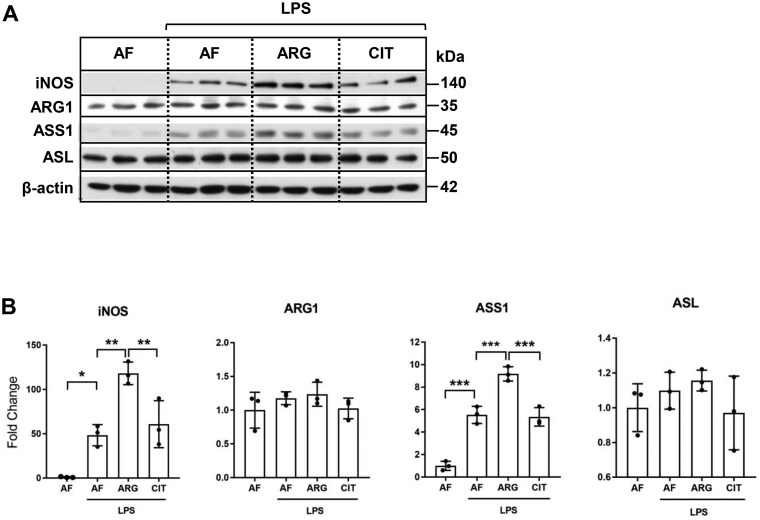

To validate whether our observations based on the analysis of RAW 264.7 cells apply to primary cells, murine bone marrow-derived macrophages were cultured in arginine-free (AF) media (0 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT) or supplemented media (125 μM ARG or 125 μM CIT) and treated with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) for 24 h. Total protein extracts were analyzed by western blotting for iNOS, ARG-1, ASS1, and ASL protein expression. LPS treatment induced iNOS and ASS1 protein expression in arginine-free media in bone marrow-derived macrophages. Similar to our observations with RAW 264.7 cells, exogenous arginine, and not citrulline, led to increased iNOS and ASS1 protein expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages. ASL protein induction was not dependent on exogenous arginine in bone marrow-derived macrophages (Fig. 3A, B).

Figure 3.

LPS-induced iNOS and ASS1 protein expressions are enhanced by exogenous arginine and not citrulline in bone marrow-derived macrophages. (A) Total protein extracts isolated from bone-marrow-derived macrophages cultured in arginine-free (AF) media (0 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT) or supplemented media (125 μM ARG or 125 μM CIT) and treated with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) for 24 h were analyzed by western blotting for iNOS, ARG-1, ASS1, and ASL protein expression. (B) Densitometric analysis of band intensity was performed. Bar values represent the mean ± SD of n = 3/group with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.01 representing statistical significance as determined by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

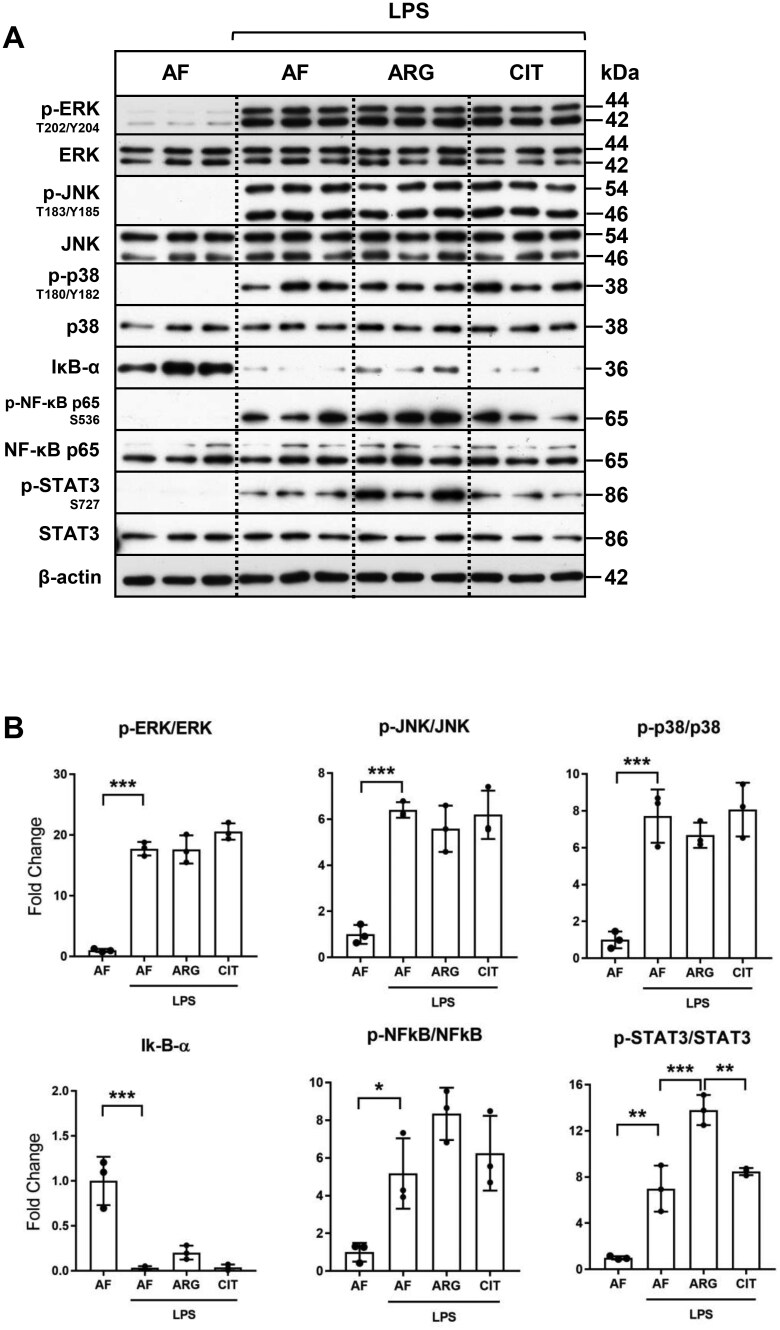

Exogenous arginine, and not citrulline, potentiates LPS-mediated phosphorylation and activation of STAT3

To investigate the underlying mechanisms responsible for the dependency on exogenous arginine for LPS-mediated induction of iNOS, ASS1, and ASL and subsequent NO generation, we next evaluated the key downstream signaling targets of the LPS-mediated Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) receptor activation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Phosphorylation and activation of the MAP kinases ERK, p38, and JNK occurred within 30 min of LPS treatment, independent of arginine supplementation (Fig. 4A and B). Activation of NF-κB signaling, as evidenced by the degradation of IκB-α and phosphorylation of NF-κB p65, occurred in cells treated with LPS in the absence of arginine. Arginine supplementation led to a modest attenuation of LPS-induced degradation of IκB-α, without appreciable change in the phosphorylation of the NF-κB p65 transcription factor; however, the arginine effects on NF-kB signaling were not statistically significant. Interestingly, phosphorylation of STAT3 at Ser727 after LPS activation was observed to occur independent of amino acid supplementation, with a significant enhancement in STAT3 phosphorylation observed in response to arginine supplementation, as compared to both arginine depletion and citrulline supplementation. Again, exogenous citrulline was not sufficient to mirror exogenous arginine-mediated potentiation of LPS-induced activation of STAT3 phosphorylation in RAW 264.7 macrophages.

Figure 4.

Exogenous arginine and not citrulline selectively regulates LPS-mediated phosphorylation and activation of STAT3. (A) RAW 264.7 macrophages were cultured in arginine-free (AF) media (0 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT) or supplemented media (125 μM ARG or 125 μM CIT) and treated with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) for 30 minutes. Total protein extracts were analyzed by western blotting for expression of enzymes involved in major proinflammatory signal transduction pathways. (B) Densitometric analysis of band intensity was performed. Bar values represent the mean ± SD of n = 3/group with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 representing statistical significance as determined by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

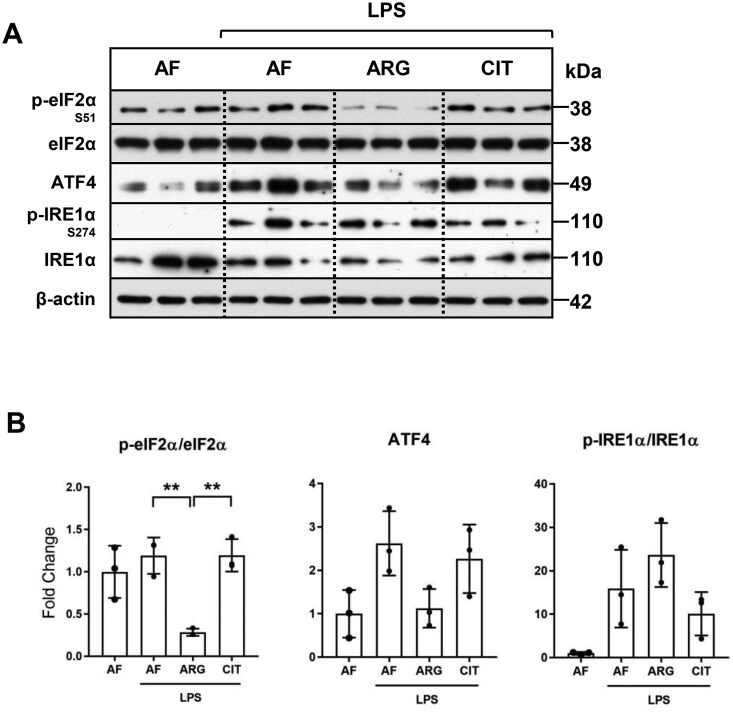

Exogenous arginine and not citrulline is necessary for dephosphorylation and inactivation of eIF2α-mediated translational repression

We next investigated whether arginine availability affected the translational regulatory mechanisms of activated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Similar to previous reports on cytokine-stimulated rat neonatal astrocytes34 and H. pylori-treated RAW 264.7 macrophages,35 we demonstrate that eIF2α phosphorylation was significantly attenuated in the presence of exogenous arginine in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Unlike arginine, exogenous citrulline did not influence eIF2α phosphorylation in LPS-treated macrophages (Fig. 5A and B). The effects of arginine supplementation on ATF4 protein expression, the downstream target of eIF2α; and phosphorylation of IRE1α, a key transducer of endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response, were not statistically significant (Fig. 5B). These findings, combined with previous reports, support the conclusion that exogenous arginine is necessary to overcome eIF2α-mediated translational repression in macrophages, which enhances translation and upregulation of iNOS, ASS1, and ASL protein expression in response to LPS treatment. Citrulline supplementation was not sufficient to overcome eIF2α-mediated translational repression in RAW 264.7 macrophages.

Figure 5.

Exogenous arginine and not citrulline is necessary for the suppression of eIF2-α phosphorylation. (A) RAW macrophages were cultured in arginine-free media (0 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT) or supplemented media (125 μM ARG or 125 μM CIT) and treated with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) for 30 minutes or 24 h. Total protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting for expression of enzymes involved in translational regulation and the ER stress response. (B) Densitometric analysis of band intensity was performed. Bar values represent the mean ± SD of n = 3/group with **P < 0.01 representing statistical significance as determined by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

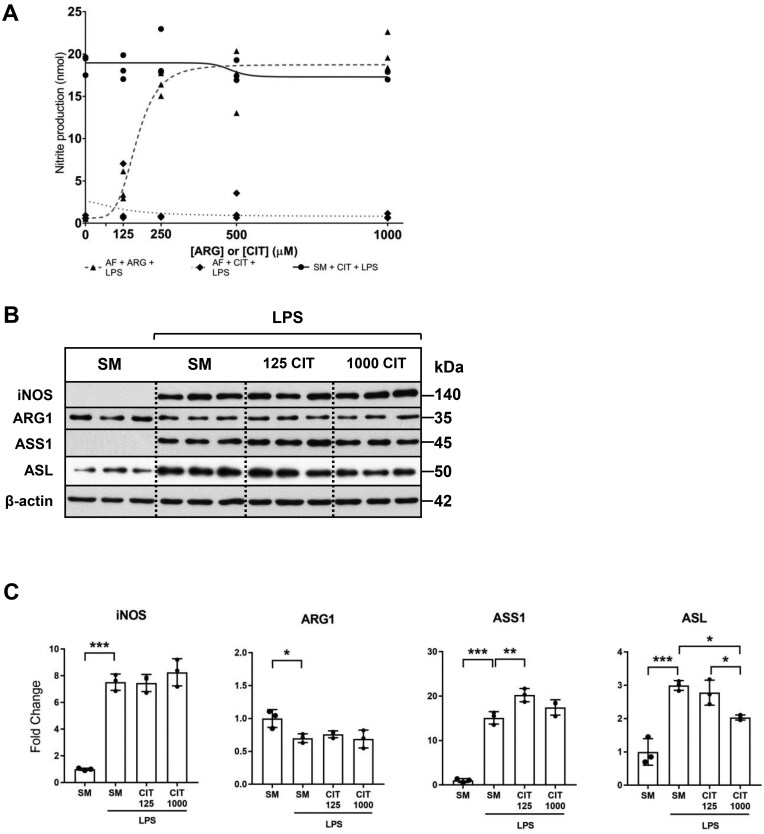

Citrulline supplementation in the presence of arginine does not affect nitric oxide generation

Recent work demonstrated that citrulline supplementation of mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) activated with IFN-γ and LPS resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of NO production and iNOS and ASS1 protein expression.36 Since our work demonstrates that citrulline supplementation in the absence of arginine was insufficient for NO production, we aimed to evaluate the effect of citrulline supplementation on NO production in the presence of arginine. Our studies suggest that citrulline supplementation in the presence of arginine did not affect NO generation (Fig. 6A) or iNOS protein expression in activated RAW macrophages (Fig. 6B and C). A lower concentration of citrulline supplementation modestly increased ASS1 protein expression, though this increase was not reproduced with high-dose citrulline supplementation. LPS-mediated ASL protein expression was significantly attenuated with high-dose citrulline supplementation.

Figure 6.

Citrulline supplementation in the presence of arginine does not affect iNOS protein expression or NO generation in macrophages. (A) RAW 264.7 macrophages were cultured in arginine-free media (AFM; 0 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT) supplemented with increasing concentrations of arginine or citrulline (0 to 1000 μM) or the standard media (SM; 400 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT) supplemented with increasing concentrations of citrulline (0 to 1000 μM) and treated for 24 h with LPS (1.0 µg/ml). Cell culture supernatant was analyzed by Griess assay to quantify nitrite production. Graph values represent n = 3/group. (B) Macrophages were cultured in the standard media, or the standard media supplemented with citrulline (125 or 1000 μM), and treated with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) for 24 h. Total protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting for expression of iNOS, ARG-1, ASS1, and ASL. (C) Densitometric analysis of band intensity was performed. Bar values represent the mean ± SD of n = 3/group with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 representing statistical significance as determined by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

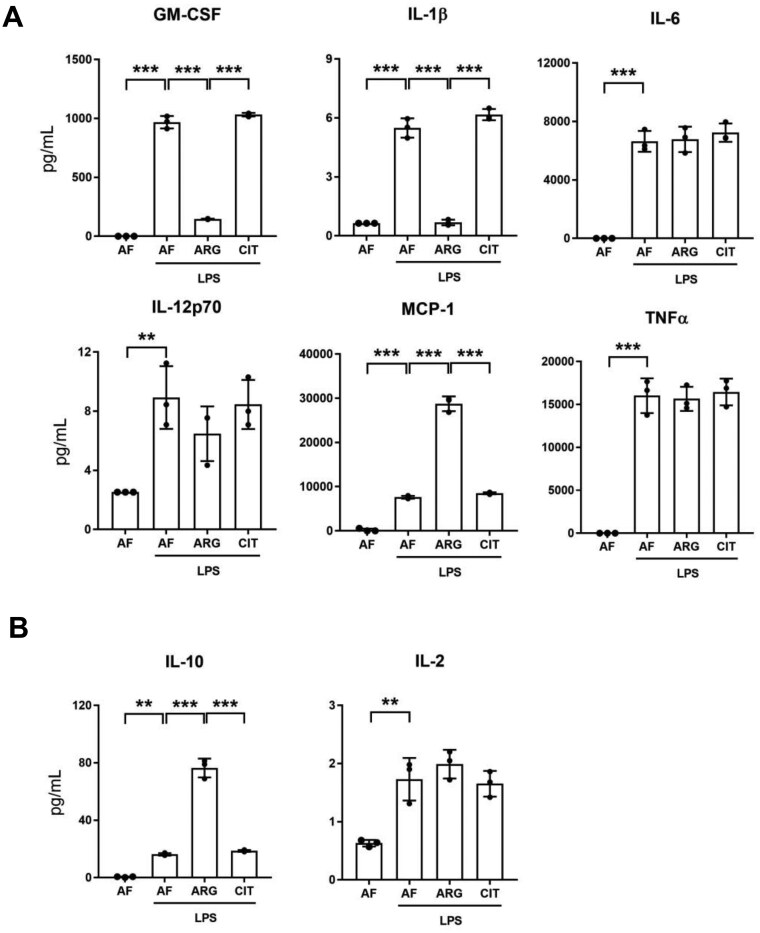

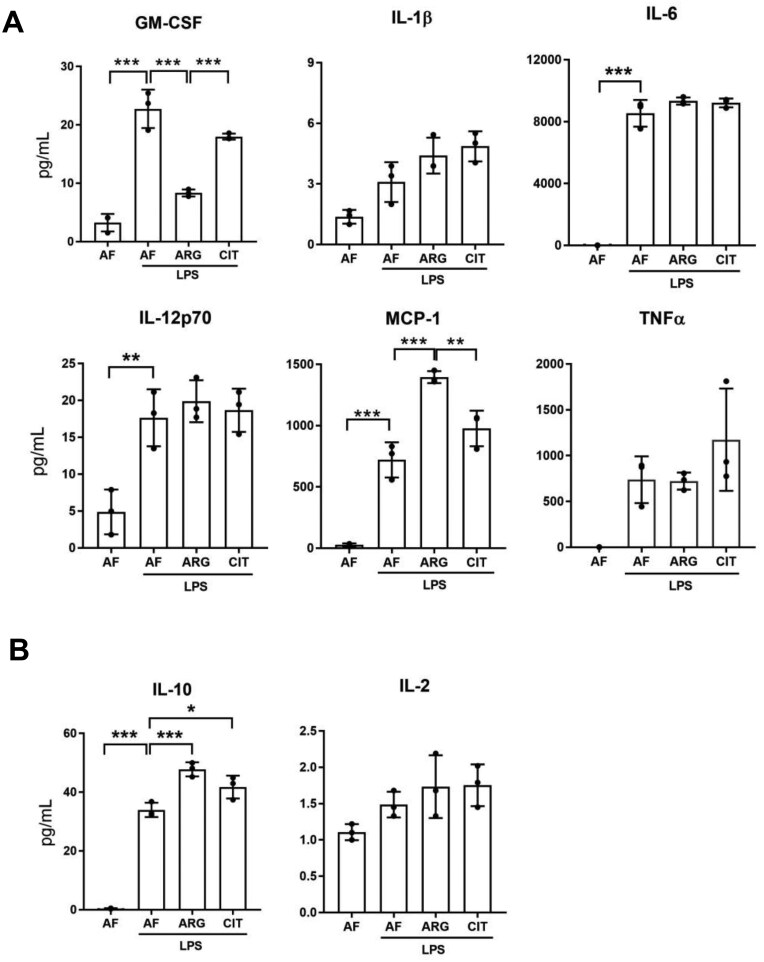

Exogenous arginine differentially regulates proinflammatory cytokine expression in macrophages

After confirming that exogenous arginine was necessary for LPS-mediated iNOS induction and NO generation in RAW 264.7 macrophages, we wondered whether the induction of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines by macrophages activated by LPS was regulated by exogenous arginine. Unlike iNOS expression and NO generation, LPS-mediated induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression was detectable in the absence of arginine or citrulline, and arginine supplementation led to differential regulation of LPS-mediated cytokine and chemokine secretion in macrophages. Curiously, we discovered that exogenous arginine, but not citrulline, attenuated the synthesis and secretion of the proinflammatory mediators GM-CSF and IL-1β while having no effect on the synthesis and secretion of IL-6, IL-12p70, or TNF-α in LPS-treated RAW 264.7 macrophages (Fig. 7A). Most notably, exogenous arginine, but not citrulline, potentiated the synthesis and secretion of MCP-1 in LPS-treated macrophages. We also noted that exogenous arginine, and not citrulline, potentiated LPS-mediated induction of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, elevated in part as a homeostatic response to LPS-mediated pro-inflammatory polarization of macrophages (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, the effects of exogenous arginine on LPS-mediated differential regulation of cytokine and chemokine synthesis and secretion were comparable between RAW 264.7 cells and bone marrow-derived macrophages (Fig. 8A, B). These findings highlight the functional significance of exogenous arginine as a key determinant of the differential regulation of cytokine and chemokine synthesis and secretion after endotoxin treatment of macrophages.

Figure 7.

Exogenous arginine differentially regulates pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines secreted by macrophages. (A) RAW 264.7 macrophages were cultured in arginine-free media (0 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT) or supplemented media (125 μM ARG or 125 μM CIT) and treated with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) for 6 h. The supernatant was analyzed by a bead-based discovery assay for quantification of secreted pro-inflammatory modulators and (B) anti-inflammatory modulators. Bar values represent the mean ± SD of n = 3/group with **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 representing statistical significance as determined by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 8.

Exogenous arginine differentially regulates pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines secreted by bone marrow-derived macrophages. (A) Bone marrow-derived macrophages were cultured in arginine-free media (0 μM ARG, 0 μM CIT) or supplemented media (125 μM ARG or 125 μM CIT) and treated with LPS (1.0 μg/ml) for 6 h. The supernatant was analyzed by a bead-based discovery assay for quantification of secreted pro-inflammatory modulators and (B) anti-inflammatory modulators. Bar values represent the mean ± SD of n = 3/group with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 representing statistical significance as determined by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that arginine plays a key role in macrophage activation beyond its well-recognized role as the substrate for iNOS and ARG1, enzymes associated with the respective classical (M1) and alternative (M2) polarization of macrophages. Our work shows that exogenous arginine is required for LPS-mediated iNOS protein induction and production of nitric oxide, an important immunomodulator, and significantly increases the macrophage secretion of MCP-1, a chemokine responsible for leukocyte migration and infiltration.37 Citrulline, in the absence of arginine, was incapable of supporting the LPS-mediated iNOS protein induction and subsequent generation of nitric oxide, secondary to its potential inability to relieve eIF2-α-mediated translational repression. Our findings support the conclusion that in the absence of arginine, citrulline supplementation is incapable of supporting LPS-mediated iNOS protein induction and nitric oxide generation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Similar to our observations with RAW 264.7 cells, LPS-induced iNOS protein expression is enhanced by exogenous arginine, and not citrulline, in bone marrow-derived macrophages. Counterintuitively, exogenous arginine, and not citrulline, induces ASS1, a key enzyme responsible for the citrulline recycling pathway in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells and bone-marrow derived macrophages. These observations suggest a limited role for the citrulline recycling pathway as an alternative source of arginine, necessary for macrophage activation in times of arginine depletion. Additionally, based on our in vitro studies with RAW 264.7 macrophages and bone marrow-derived macrophages, we report a previously unrecognized influence of exogenous arginine availability on cytokine and chemokine secretion that may have system-wide implications during the host response to infection.

Although both arginine and citrulline supplementation remain of interest as potential therapeutic modalities in the treatment of sepsis, several studies have reported conflicting evidence on the capacity of the citrulline recycling pathway to generate arginine necessary for NO production. Similar to our findings, early investigations in rat peritoneal macrophages30 and rat alveolar macrophages32 noted that citrulline supplementation alone was insufficient to produce NO after LPS treatment, despite detection of ASS1 protein in the latter study. These reports conflicted with results from J774 murine macrophages in which it was shown that after LPS and IFN-γ stimulation, citrulline in the absence of arginine was able to partially restore NO synthesis.31 The controversy was reexamined in a transgenic rat endothelial cell model, in which both iNOS and eNOS were expressed, that was the first to suggest that the different isoforms of NOS preferentially utilize different pools of arginine.28 Exogenous arginine fueled iNOS-derived NO production, while arginine regenerated from citrulline was a major source of eNOS-derived NO production. These findings inspired new hypotheses about the potential for selective promotion of NO production via exploitation of the citrulline recycling pathway, particularly after the clinical trial that attempted application of a nonselective NOS inhibitor failed.24 Nonetheless, fear about the potential for either arginine or citrulline to contribute to the hyperproduction of NO and worsen vasodilatory shock in the already delicate septic patient, however unfounded, has prevented the clinical application of either therapy. With the recent uncovering of sepsis endotypes and the appreciation of arginine as a central modulator of immune function, it becomes paramount to understanding the precise capacities of the enzymes of arginine metabolism, specifically in the context of an arginine-deficient state akin to sepsis, to inform and expedite consideration of amino acid supplementation or modulation as a precision therapy in sepsis. Our results confirm that citrulline supplementation is unlikely to contribute to iNOS-derived hyperproduction of NO and may be considered as a potential selective therapy in sepsis that may preferentially enhance eNOS-derived NO production in endothelial cells.

Arginine alternatively emerges as a potential gatekeeper of adequate immune function through its demonstrated regulatory role in macrophages via translational regulation of iNOS. Without adequate iNOS expression and NO production, it is plausible to consider that arginine deficiency may contribute to immune paralysis in sepsis. Indeed, arginine was shown to be required for iNOS-dependent macrophage defense against H. pylori infection.35 Widely considered a prototypical marker of acute inflammation, iNOS induction and metabolism of arginine to nitric oxide is central to the polarization of macrophages to the M1 pathway, with subsequent secretion of proinflammatory cytokines.12 However, here we report for the first time that arginine itself differentially regulates the immune-modulating factors secreted by activated macrophages beyond just nitric oxide. During arginine deficiency, higher levels of the proinflammatory molecules GM-CSF and IL-1β are detected in the supernatant of LPS-activated RAW 264.7 macrophages, along with other classically activated macrophage-derived proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12p70; arginine was not essential for their induction and secretion. To our surprise, when exogenous arginine was supplied, secretion of GM-CSF and IL-1β was suppressed and higher levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 were detected.

Previous studies suggest that NO may downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, and IL-1β mRNA expression in lung macrophages.38 NO-mediated inhibition of NF-kB activation is considered a likely mediator of transcriptional regulation of TNF-α and IL-1β in RAW 264.7 macrophages and vascular endothelial cells.39,40 On the contrary, N-monomethyl arginine (NMMA, a potent inhibitor of iNOS) treatment and suppression of NO production have been shown to inhibit LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β expression while enhancing anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages.41 Furthermore, arginine catabolism by arginase-1 leads to the generation of ornithine, a key substrate for polyamine synthesis in macrophages.42 Polyamines such as putrescine, spermidine, and spermine may have dual roles in promoting pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines.43,44 It is unclear whether the anti-inflammatory effect of arginine supplementation in RAW 264.7 cells and bone-marrow derived macrophages reported in this study is orchestrated by iNOS-mediated induction of NO or arginase-mediated induction of polyamines but plans for further mechanistic investigation are forthcoming.

Perhaps in the presence of arginine, activated macrophages suppress the expression of some proinflammatory cytokines and induce anti-inflammatory cytokines to balance the potent proinflammatory effect of upregulated iNOS and NO generation to prevent a potentially harmful hyperinflamed response. The classical M1/M2 dichotomy of macrophages is already largely considered a simplified summary of what is increasingly appreciated to be a complex spectrum of cell programming, although our results function to emphasize caution against using arginine-iNOS metabolism as an umbrella marker of “proinflammatory” states. Interestingly, we also show that arginine availability allows for significantly higher secretion of MCP-1/CCL2, a chemotactic factor that is important for the recruitment of monocytes, T lymphocytes, and natural killer cells to areas of inflammation and may directly influence T-cell differentiation.37 One possibility for the co-dependency of NO generation and MCP-1 secretion on arginine may relate to a conserved mechanism for macrophages to recruit leukocytes to arginine-rich areas of active inflammation, while avoiding recruitment to arginine-poor areas, knowing that arginine is central to the ability of these cells to activate an appropriate immune response. Similarly, perhaps arginine deficiency functions as a negative feedback mechanism reflecting the exhaustion of the immune response in that microenvironment, preventing further propagation of an unnecessary response and the ensuing dysregulation. Understanding the mechanistic details of this differential arginine regulation and its implications on cell-cell regulation and the directing of inflammation at large represents an important opportunity for future study.

Notably, we demonstrate that LPS-mediated induction of the enzymes of the citrulline recycling pathway only occurs in the presence of arginine in RAW 264.7 and bone marrow-derived macrophages. Without ASS1, citrulline is unable to supply intracellular arginine to relieve the translational repression of iNOS. Why arginine would be required for the induction of ASS1 and ASL in addition to iNOS is perplexing since the pathway seemingly could function to salvage the cell from arginine deficiency. Rapovy et. al demonstrated that citrulline supplementation in the absence of arginine of macrophages activated by IFN-γ was able to sustain NO production, though at a decreased amount compared to cells exposed to exogenous arginine, which may represent differential effects of LPS versus IFN-γ stimulation.45 Bryk et. al and Qualls et. al showed that, while the initial burst of NO by LPS-activated macrophages is fueled by extracellular arginine, ASS1, and ASL could support NO production after prolonged arginine depletion.46,47 However, both studies were conducted in “low” arginine states instead of true arginine deficiency, at which levels arginine was shown capable of at least partially suppressing eIF2-α phosphorylation (Ser51) and relieving translational repression.34 Appreciation of the coordinated induction of iNOS and the citrulline recycling pathway with the simultaneous recognition that macrophages required exogenous arginine for NO production formed the basis of the “arginine paradox,” which was ultimately explained by the discovery of the effect of exogenous arginine on eIF2-α phosphorylation and is further supported by our work. Collectively, it appears that the absence of exogenous arginine has a profound impact on the translational regulation of key enzymes necessary for arginine utilization and de novo synthesis of arginine, possibly as a protective mechanism that completely disarms the NO-mediated immune response to endotoxin and to allow the cell to focus its energy on alternative proinflammatory pathways. This theory is supported by our cytokine findings, which reveal that in arginine deficiency, macrophages secrete higher levels of classically activated macrophage-derived proinflammatory mediators compared to the secretion profile of activated macrophages with access to exogenous arginine.

Interestingly, recent work by Mao et al demonstrated that IFN-γ, LPS, and IFN-γ+LPS led to reduced intracellular citrulline levels via upregulation of ASS1 expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages. Citrulline supplementation, via inhibition of JAK2-STAT1 signaling and downregulation of ASS1, led to decreased NO generation and proinflammatory cytokine secretion.36 Based on these observations they conclude that citrulline depletion by ASS1 is required for proinflammatory macrophage activation.36 On the contrary, our studies suggest that citrulline supplementation in the presence of arginine did not reduce ASS1 protein expression and had no effect on iNOS protein expression and NO generation in response to LPS treatment of RAW 264.7 macrophages. Further studies are required to determine if these divergent observations are due to differences between RAW 264.7 and bone marrow-derived macrophages, both well-established in vitro models of mouse macrophages. Although the complexities of arginine and citrulline metabolism and their regulatory roles in the setting of infection are yet to be fully elucidated, both are progressively recognized as not just amino acids, but important modulators in the immune response in sepsis.

Limitations of our study include the simulation of a true arginine-deficient state versus a low-arginine state as mentioned, which may not be reflective of all in vivo microenvironments in sepsis. Additionally, we chose to use endotoxin stimulation as our sepsis model to activate macrophages instead of cytokines like IFN-γ to study the direct effect of infection on macrophage activation, but this may explain some differences in the results of similar studies. While it is impossible to simulate the intricate in vivo milieu of sepsis in a cell model, we aimed to study a simplified model in hopes of offering clarification to the complex, controversial body of literature that outlines arginine metabolism in sepsis. Finally, RAW 264.7 macrophages are murine-derived, and not all pathobiology is equal across species. Much of the preclinical sepsis research still occurs in mouse models and thus mice cell lines are still relevant but repeating similar experiments in human-derived macrophages represents a future area of investigation that would undoubtedly yield even more interesting insights into the development and application of amino acid supplementation as a strategy for sepsis recovery.

Restoration of arginine deficiency, either via citrulline supplementation to restore arginine levels in non-immune cells without the fear of confounding hyperproduction of NO by macrophages, or via arginine supplementation, which may promote a more balanced macrophage cytokine and chemokine secretion profile and chemotaxis to direct immune responses to targeted areas, holds promise as a tool to promote restoration of homeostasis in the complex dysregulated septic state.

Contributor Information

Kelsey Stayer, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States.

Saliha Pathan, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States.

Aalekhya Biswas, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States.

Huiqiao Li, USDA/ARS Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States.

Yi Zhu, USDA/ARS Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States.

Fong Wilson Lam, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States.

Juan Marini, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States; USDA/ARS Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States.

Sundararajah Thevananther, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States; Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States.

Author contributions

K.S. designed and performed most of the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. S.P., A.B., H.L., and Y.Z. performed experiments and analyzed data. F.L. analyzed data; S.T. designed, performed experiments, and analyzed data; J.M. and S.T. conceived and supervised the project.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH/NIDDK DK069558 (S.T.), NIH/NIDDK DK136532 (Y.Z.), NIH/NIGMS GM108940 (J.M.), and funding from Men of Distinction (S.T.), Cade R. Alpard Foundation, and Spain Fund for Pediatric Liver Research at Texas Children’s Hospital.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

- 1. Singer M et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gotts JE, Matthay MA. Sepsis: pathophysiology and clinical management. BMJ. 2016;353:i1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cavaillon JM, Singer M, Skirecki T. Sepsis therapies: learning from 30 years of failure of translational research to propose new leads. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12:e10128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rudd KE et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395:200–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mira JC et al. Sepsis pathophysiology, chronic critical illness, and persistent inflammation-immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:253–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maslove DM et al. Redefining critical illness. Nat Med. 2022;28:1141–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wong HR et al. Identification of pediatric septic shock subclasses based on genome-wide expression profiling. BMC Med. 2009;7:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scicluna BP et al. ; MARS consortium. Classification of patients with sepsis according to blood genomic endotype: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:816–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maslove DM, Tang BM, McLean AS. Identification of sepsis subtypes in critically ill adults using gene expression profiling. Crit Care. 2012;16:R183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davenport EE et al. Genomic landscape of the individual host response and outcomes in sepsis: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:259–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sweeney TE et al. Unsupervised analysis of transcriptomics in bacterial sepsis across multiple datasets reveals three robust clusters. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:915–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wculek SK, Dunphy G, Heras-Murillo I, Mastrangelo A, Sancho D. Metabolism of tissue macrophages in homeostasis and pathology. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19:384–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rath M, Müller I, Kropf P, Closs EI, Munder M. Metabolism via arginase or nitric oxide synthase: two competing arginine pathways in macrophages. Front Immunol. 2014;5:532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis JS, Anstey NM. Is plasma arginine concentration decreased in patients with sepsis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:380–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Freund H, Atamian S, Holroyde J, Fischer JE. Plasma amino acids as predictors of the severity and outcome of sepsis. Ann Surg. 1979;190:571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Waardenburg DA, de Betue CT, Luiking YC, Engel M, Deutz NE. Plasma arginine and citrulline concentrations in critically ill children: strong relation with inflammation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1438–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Argaman Z et al. Arginine and nitric oxide metabolism in critically ill septic pediatric patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:591–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Villalpando S et al. In vivo arginine production and intravascular nitric oxide synthesis in hypotensive sepsis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luiking YC, Poeze M, Ramsay G, Deutz NE. Reduced citrulline production in sepsis is related to diminished de novo arginine and nitric oxide production. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wijnands KA, Castermans TM, Hommen MP, Meesters DM, Poeze M. Arginine and citrulline and the immune response in sepsis. Nutrients. 2015;7:1426–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Evans L et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:1181–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weiss SL et al. Surviving sepsis campaign international guidelines for the management of septic shock and sepsis-associated organ dysfunction in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21:e52–e106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bakker J et al. ; Glaxo Wellcome International Septic Shock Study Group. Administration of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-methyl-L-arginine hydrochloride (546C88) by intravenous infusion for up to 72 hours can promote the resolution of shock in patients with severe sepsis: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study (study no. 144-002). Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. López A et al. Multiple-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor 546C88: effect on survival in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Agarwal U, Didelija IC, Yuan Y, Wang X, Marini JC. Supplemental citrulline is more efficient than arginine in increasing systemic arginine availability in mice. J Nutr. 2017;147:596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yuan Y et al. The citrulline recycling pathway sustains cardiovascular function in arginine-depleted healthy mice, but cannot sustain nitric oxide production during endotoxin challenge. J Nutr. 2018;148:844–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wijnands KA et al. Citrulline supplementation improves organ perfusion and arginine availability under conditions with enhanced arginase activity. Nutrients. 2015;7:5217–5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shen LJ, Beloussow K, Shen WC. Accessibility of endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthase to the intracellular citrulline-arginine regeneration pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wijnands KAP et al. Microcirculatory function during endotoxemia-a functional citrulline-arginine-NO pathway and NOS3 complex is essential to maintain the microcirculation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu GY, Brosnan JT. Macrophages can convert citrulline into arginine. Biochem J. 1992;281 ( Pt 1):45–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baydoun AR, Bogle RG, Pearson JD, Mann GE. Discrimination between citrulline and arginine transport in activated murine macrophages: inefficient synthesis of NO from recycling of citrulline to arginine. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;112:487–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hammermann R et al. Inability of rat alveolar macrophages to recycle L-citrulline to L-arginine despite induction of argininosuccinate synthetase mRNA and protein, and inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis by exogenous L-citrulline. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1998;358:601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Toda G, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T, Ueki K. Preparation and culture of bone marrow-derived macrophages from mice for functional analysis. STAR Protoc. 2021;2:100246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee J, Ryu H, Ferrante RJ, Morris SM Jr., Ratan RR. Translational control of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by arginine can explain the arginine paradox. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4843–4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chaturvedi R et al. L-arginine availability regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent host defense against Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4305–4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mao Y, Shi D, Li G, Jiang P. Citrulline depletion by ASS1 is required for proinflammatory macrophage activation and immune responses. Mol Cell. 2022;82:527–541.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:313–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meldrum DR Jr. et al. Nitric oxide downregulates lung macrophage inflammatory cytokine production. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen F, Kuhn DC, Sun SC, Gaydos LJ, Demers LM. Dependence and reversal of nitric oxide production on NF-kappa B in silica and lipopolysaccharide-induced macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;214:839–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peng HB, Rajavashisth TB, Libby P, Liao JK. Nitric oxide inhibits macrophage-colony stimulating factor gene transcription in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17050–17055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu CH et al. Nitric oxide modulates pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages. J Trauma. 2003;55:540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Karadima E, Chavakis T, Alexaki VI. Arginine metabolism in myeloid cells in health and disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2025;47:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu S et al. Spermidine suppresses development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Puntambekar SS 3rd et al. LPS-induced CCL2 expression and macrophage influx into the murine central nervous system is polyamine-dependent. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:629–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rapovy SM et al. Differential requirements for L-citrulline and L-arginine during antimycobacterial macrophage activity. J Immunol. 2015;195:3293–3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bryk J, Ochoa JB, Correia MI, Munera-Seeley V, Popovic PJ. Effect of citrulline and glutamine on nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 cells in an arginine-depleted environment. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008;32:377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Qualls JE et al. Sustained generation of nitric oxide and control of mycobacterial infection requires argininosuccinate synthase 1. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.