ABSTRACT

The rapid rise in antibiotic resistance is a critical global health issue, and few new classes of antibiotics have been discovered since 1990 compared to the antibiotic's golden era between 1950 and 1970. However, developing new antimicrobial compounds faces many challenges, improvements in cultivation methods, genetic engineering, and advanced technologies are opening new paths for discovering and producing effective antibiotics. This study focuses on the fungal microbiome as a promising source of new antibiotics. We explored historical developments and advanced genetic techniques to reveal the potential of fungi in antibiotic production. Although isolating and scaling up fungal antibiotic production presents challenges, innovative approaches like in situ separation during fermentation can effectively address these issues. Our research highlights the importance of understanding fungal communication and metabolite sharing to enhance antibiotic yields and the connection of cutting‐edge technologies in accelerating the discovery and optimization of antibiotic‐producing fungi. By focusing on these technical aspects and fostering teamwork across various fields, this study aims to overcome current obstacles, and advance the development of antibiotic production technologies.

Keywords: antibiotic discovery, fungal metabolite sharing, fungal microbiome, fungal–bacterial interactions, industrial‐scale processes of antibiotics

Graphical abstract illustrating the multifaceted approach to harnessing fungal microbiome diversity for antibiotic discovery. Key elements include historical insights, modern genomic tools, and innovative biotechnological strategies for isolating and enhancing fungal antibiotic production. Highlighted are fungal communication networks and advanced fermentation techniques aimed at scaling up production and improving antibiotic yields.

1. Introduction

The global rise of antimicrobial resistance has created an urgent demand for new antibiotics, yet the pace of discovering novel compounds has significantly slowed in recent decades (Salam et al. 2023). One often‐overlooked but immensely promising source is the fungal microbiome, which continues to reveal its potential as a reservoir of bioactive secondary metabolites with potent antimicrobial properties (A. Gupta et al. 2023). Fungi have long been recognized for their vital role in antibiotic discovery and ation to the development of essential drugs that have revolutionized modern medicine (Walker 2021; Dutta et al. 2022). From the serendipitous discovery of penicillin to the synthesis of blockbuster drugs like Cyclosporine and Caspofungin, fungi have provided a rich reservoir of secondary metabolites with potent bioactive properties (Baby and Thomas 2021). The unique biosynthetic capabilities of fungi, often stimulated by environmental stress factors, enable them to produce diverse bioactive compounds (Saxena et al. 2018). Despite this rich legacy, the pace of discovering new antibiotics has slowed, prompting a reevaluation of traditional bioprospecting methods (Ryan et al. 2019). This has led to a shift in focus toward understanding the ecological and genetic underpinnings of fungal metabolite production and leveraging cutting‐edge tools to unlock previously inaccessible biosynthetic capacities (Alves et al. 2025).

In recent years, advances in genomic and metabolomic technologies have revitalized interest in fungal secondary metabolites (Jampilek 2022). Techniques such as whole‐genome sequencing and bioinformatics tools have enabled the identification of novel biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), facilitating the dereplication process and reducing rediscovery rates (Karwehl and Stadler 2016). Additionally, advances in chromatographic, spectroscopic, and fermentation techniques have facilitated the isolation and characterization of countless new metabolites (Silber et al. 2016). Coculture techniques and stress‐induced biosynthetic pathways have emerged as innovative strategies to uncover hidden bioactive compounds, further expanding the scope of fungal antibiotic discovery (Demers et al. 2018; Krause 2021). The urgency to address antimicrobial resistance has underscored the need for new therapeutic agents, driving researchers to explore untapped fungal biodiversity using modern “‐OMICS” technologies and advanced biotechnological methods (Snelders et al. 2020). Techniques like CRISPR‐Cas9 genome editing, promoter engineering, and heterologous expression systems are helping researchers tap into the hidden chemical diversity of fungi (Leal et al. 2024). Studies have shown that fungi produce specialized metabolites with potent antimicrobial properties that influence bacterial community diversity in natural environments (Mosunova et al. 2022). The human microbiome itself, including fungal components, has been shown to harbor diverse microbial communities that produce bioactive molecules with potential therapeutic applications (Xiong 2016). As researchers continue to explore extreme habitats and symbiotic associations, the integration of interdisciplinary approaches and advanced technologies holds promise for harnessing the fungal microbiome as a rich reservoir of novel antibiotics (Nirmala and Zyju 2017). Beyond laboratory innovations, understanding fungal communication with bacteria and exploring fungal–bacterial co‐cultures have opened exciting possibilities for boosting metabolite production and discovering novel compounds (Hyde et al. 2024). These interdisciplinary efforts are reshaping how we approach fungal microbiome research for antibiotic discovery (Tiew et al. 2020).

In this review article, we investigated various aspects of fungal microbiome research aimed at uncovering novel antimicrobial compounds. We explored historical developments in fungal antibiotic discovery to challenges associated with isolating BGCs from fungal genomes and discussed strategies for identifying antibiotic‐producing fungi from complex microbial communities.

2. Fungal Microbiome in Antibiotic Discovery

Research into fungal microbiomes has greatly advanced antibiotic development and uncovered many potential bioactive compounds. Filamentous fungi, such as those from the Penicillium genus, are prolific producers of secondary metabolites with diverse pharmaceutical applications, including antibiotics, immunosuppressors, and anticancer drugs (Dutta et al. 2022; de Matos et al. 2023). The discovery of penicillin marked the beginning of the golden era of antibiotics, and fungi have since provided numerous blockbuster drugs like Cyclosporine and Lovastatin (Prescott et al. 2023). Marine fungi, in particular, have demonstrated vast chemo diversity and potential for sustainable antibiotic production through marine biotechnology (Suresh and Abinayalakshmi 2022). Advances in genomics and metabolomics have further accelerated the discovery of novel antibiotics, revealing that the biosynthetic potential of fungi is far from exhausted (Panter et al. 2021). The manipulation of host microbiomes by fungal pathogens through effector proteins also presents an untapped resource for new antibiotics (Snelders et al. 2020). The rich biodiversity and unique biosynthetic capabilities of fungi make them invaluable in the ongoing quest for new antibiotics to combat the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance (da Silva et al. 2023).

2.1. Historical Perspective: Fungal Contributions to Antibiotic Discovery

The discovery and development of antibiotics from the fungal microbiome have marked significant milestones in medical history. The discovery of penicillin from the mold Penicillium notatum by Alexander Fleming in 1928 marked the beginning of the antibiotic era (Fleming 1929). This landmark discovery spurred the exploration of fungal sources for novel antibiotics, leading to the identification of cephalosporins from Cephalosporium acremonium (Newton and Abraham 1955) in 1956 and griseofulvin from Penicillium griseofulvum in 1959 (Flint et al. 1959). These compounds have been crucial in treating various infections and have paved the way for modern antimicrobial therapy.

Recent advancements in genomics and bioinformatics have reignited interest in the fungal microbiome as a reservoir of novel bioactive compounds (Conrado et al. 2022). Techniques like metagenomics and genome mining have opened doors to previously inaccessible BGCs, facilitating the discovery of promising new antibiotic candidates (Clevenger et al. 2017). Several clinically relevant antibiotics currently in use originate from fungal sources. Table 1 provides a summary of these major antibiotics, including their source organism and their biological target. This ongoing research highlights the immense potential of fungal microbiomes to contribute to the development of the next generation of antibiotics.

Table 1.

Clinically relevant antibiotics family isolated directly from fungal microbiome.

| Antibiotic class | Example of clinically used drug | Biological target | Fungus name | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillins | Penicillin G | Bacterial cell wall synthesis | Penicillium notatum | Broomfield and Filipa Simões (2019) |

| Cephalosporins | Cefadroxil | Bacterial cell wall synthesis | Acremonium chrysogenum (formerly Cephalosporium acremonium) | L. Liu, Chen et al. (2022) |

| Pleuromutilins | Retapamulin | Protein synthesis | Clitopilus passeckerianus | de Mattos‐Shipley et al. (2017) |

| Amoxicillin | Clavacillin | Protein synthesis | Aspergillus clavatus | Katzman et al. (1944) |

| Carbapenems | Imipenem | Bacterial cell wall synthesis | Streptomyces cattleya (fungal‐associated) | Imipenem (2025) |

| Glycopeptides | Vancomycin | Bacterial cell wall synthesis | Mycolatopsis orientalis | Amycolatopsis Orientalis (2025) |

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | Protein synthesis (50S ribosomal subunit) | Saccharopolyspora erythraea | Dinos (2017) |

| Ansamycins | Rifampin | RNA polymerase inhibition | Amycolatopsis rifamycinica | Ansamycin (2025) |

| Tetracyclines | Doxycycline | Protein synthesis (30S ribosomal subunit) | Streptomyces spp. | Tetracycline (2025) |

2.2. Fungal Microbiome: A Reservoir of Bioactive Potential

The fungal microbiome is indeed a significant reservoir of bioactive potential, offering a plethora of compounds with diverse applications in pharmaceuticals, agriculture, and biotechnology. Fungi, including endophytes, basidiomycetes, and actinomycetes, produce a wide range of bioactive metabolites such as steroids, terpenoids, quinones, coumarins, phenols, saponins, and alkaloids, which exhibit anticancer, immunomodulatory, antitubercular, antiviral, and antidiabetic activities (Pant et al. 2021; Rousta et al. 2023). These metabolites are crucial for developing new drugs and therapies, addressing the high demand for novel antimicrobial and antitumor agents (Singh 2021). Fungal strains are also known for synthesizing bioactive compounds like bioactive peptides, chitin/chitosan, β‐glucan, ɣ‐aminobutyric acid, l‐carnitine, ergosterol, and fructooligosaccharides, which have significant health benefits and potential applications in innovative food production (Chourasia et al. 2022; Shahbaz et al. 2023). The exploration of fungal endophytes, which live symbiotically within plant tissues, has revealed their potential to produce unique bioactive compounds that can improve plant health and offer therapeutic benefits to humans (Selvakumar and Panneerselvam 2018).

2.3. The Potentiality of Fungal Secondary Metabolites

Fungi exhibit high productivity in the synthesis of bioactive secondary metabolites, which hold considerable promise for advancement in the field of antimicrobial drug discovery (Table 2). For instance, Nigrospora spp. isolated from Rhizophora racemosa produces a variety of compounds with antimicrobial properties against both Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria (Chourasia et al. 2022). Aspergillus polyporicola, isolated from Synsepalum dulcificum roots, yields several new and known compounds that exhibit inhibitory activities against Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Staphylococcus aureus, and other pathogens (S. S. Liu, Huang et al. 2022). Similarly, secondary metabolites from Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma lixii show high antimicrobial activity, particularly against Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli, and demonstrate a synergistic effect when combined with dicationic pyridinium iodide against Klebsiella pneumoniae (Abdelalatif et al. 2023). Chaetomium elatum, isolated from Hyssopus officinalis, produces penicillic acid, which has strong antibacterial effects against Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus (Soytong and Kanokmedhakul 2022). Additionally, Aspergillus sydowii from seawater yields compounds with selective inhibitory activities against several human pathogenic bacteria (Gao et al. 2017).

Table 2.

List of high‐productivity bioactive secondary metabolites isolated from fungus for antimicrobial drug discovery.

| Fungal source | Type of fungi | Secondary metabolites Identified | Antimicrobial activities | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nigrospora spp. | Endophytic | Septicine, aureonitol, papuamine, di‐iso‐octylphthalate, cladosporin, tetrabenzofuran, eicosane. | Antimicrobial activities against Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria. | Izuogu et al. (2023) |

| Aspergillus polyporicola | Saprophytic | Kipukasins O and P, arthropsadiol D, (+)‐2,5‐dimethyl‐3(2H)‐benzofuranone, polyporicolic acids A and B, (+)‐acetylkojic acid, and others. | Inhibitory activity against MRSA, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhimurium, and fungi. | S. Liu, Huang et al. (2022) |

| Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma lixii | Saprophytic | Pentadecanoic acid, 14‐methyl‐, methyl ester, 9‐octadecenoic acid (Z)‐, methyl ester, 2,4‐decadienal, 1,8‐cineole, 4‐hydroxybenzaldehyde, and others. | High activity against Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli; synergistic effect with dicationic pyridinium iodide against Klebsiella pneumoniae. | Abdelalatif et al. (2023) |

| Chaetomium elatum | Endophytic | Penicillic acid, Chaetoglobosin A, Chaetoglobosin C. | Strong antibacterial activities against Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. | Eshboev et al. (2023) |

| Aspergillus sydowii | Saprophytic/endophytic | Quinazolinone alkaloid, aromatic bisabolene‐type sesquiterpenoid, chorismic acid analogue, sydowic acid, sydonic acid. | Selective inhibitory activities against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. | Gao et al. (2017) |

| Colletotrichum sp. | Saprophytic/endophytic | Acropyrone, beauvericin, indole‐3‐carbaldehyde, indolyl‐3‐acetic acid, rocaglamid A. | Inhibitory effect against Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Aspergillus niger, Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli. | Munasinghe et al. (2017) |

| Candida spp. | Commensal | Benzene, pentamethyl, n‐hexadecanoic acid, 1‐docosene, bis(2‐ethylhexyl), others. | Various antimicrobial activities. | Hassan and Kasim (2023) |

2.4. Advances in Fungal Metabolic and Genetic Engineering for Antibiotic Discovery

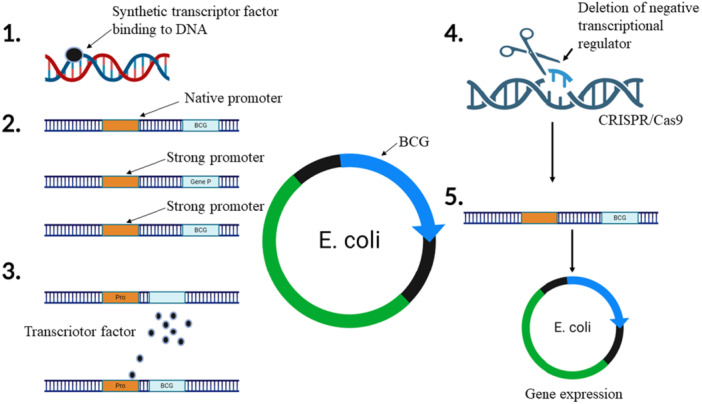

Metabolic engineering can significantly enhance fungal biosynthesis by manipulating and optimizing various biosynthetic pathways to increase the yield and efficiency of desired metabolites. Advances in DNA sequencing and bioinformatics have revealed numerous cryptic BGCs in fungal genomes, which are often transcriptionally silent under laboratory conditions (Hur et al. 2023; D. Wang, Jin, et al. 2023). Strategies to “waking up” silent gene clusters for antibiotic production include the use of synthetic transcription factors, gene cluster refactoring, and heterologous expression in optimized host strains strains such as Aspergillus oryzae and Fusarium graminearum. The different methods are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Potential approaches for enhancing the heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in Fungi.

2.4.1. Synthetic Biology Approaches

Synthetic biology tools, including synthetic transcription factors, gene cluster refactoring, and the assembly of artificial transcription units, further enhance the expression of both endogenous and exogenous BGCs in filamentous fungi (Mózsik, Pohl, et al. 2021). Targeted overexpression of pathway‐specific transcriptional regulators, such as AspE in Aspergillus sp., has resulted in the activation of previously silent metabolic pathways and the production of novel bioactive compounds with significant antimicrobial properties (Etxebeste 2021). Epigenetic modifications using small molecular compounds to alter chromatin structure have also shown promise in activating silent BGCs, although the response can be complex and variable (Pillay et al. 2022). Furthermore, coexpression network approaches have been utilized to identify and overexpress global and pathway‐specific transcription factors, thereby modulating secondary metabolite production in fungi like Aspergillus niger (Cairns et al. 2019).

2.4.2. Promoter Engineering

Promoter exchange techniques have become an effective method to activate BGCs in antibiotic‐producing fungi by replacing native promoters with strong, inducible ones to overcome the issue of silent or low‐expressing gene clusters in standard lab conditions, while an “always‐on” promoter ensures constant expression of antibiotic biosynthetic genes (Bergmann et al. 2010). For instance, the easyPACId method demonstrated that exchanging native promoters with inducible ones in Δhfq mutants of Photorhabdus, Xenorhabdus, and Pseudomonas led to the exclusive production of corresponding natural products (NPs) from targeted BGCs, facilitating NP identification and bioactivity testing (Bode et al. 2019). Additionally, the use of endogenous promoter libraries, constructed through rational design and site‐selective mutagenesis, has been shown to optimize multi‐gene metabolic pathways for high‐yield production of metabolites (Jin et al. 2019). Replacing a native promoter with the highly inducible alcA promoter in Aspergillus nidulans can boost penicillin production by up to 100 times, resulting in a significant 30‐fold increase in penicillin yields (Pi et al. 2020). Additionally, the use of constitutive promoters like gpdA and tef1 has been shown to enhance secondary metabolite production, indicating the potential of strong promoters in industrial applications (Umemura et al. 2020).

2.4.3. Transcription Factor Overexpression

Overexpression of transcription factors represents a potent approach for the activation of BGCs within the fungal microbiome, consequently facilitating the synthesis of essential secondary metabolites. By overexpressing pathway‐specific transcription factors, researchers have successfully activated these silent clusters, leading to the discovery of novel compounds. For instance, overexpression of the transcriptional regulator AspE in Aspergillus sp. CPCC 400735 activated a downregulated metabolic pathway, resulting in the production of 13 asperphenalenone derivatives with significant anti‐influenza A virus effects (Khan et al. 2020). Similarly, the overexpression of the xan BGC transcription factor AfXanC in Aspergillus fumigatus significantly increased xanthocillin production, although its ortholog PeXanC in Penicillium expansum unexpectedly promoted citrinin synthesis instead (Paul et al. 2022). Additionally, global regulatory networks have been explored using coexpression network approaches, identifying multiple transcription factors that modulate secondary metabolism in Aspergillus niger (Kwon et al. 2021). Finally, the transcription factor TRI6 in Fusarium graminearum was shown to regulate multiple BGCs, both directly and indirectly, highlighting the complex regulatory networks governing secondary metabolism (Shostak et al. 2020).

2.4.4. CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing

The CRISPR/Cas9 system, characterized by its ability to introduce precise genetic modifications, has been effectively employed to activate silent BGCs. The versatility of CRISPR/Cas9 extends to various Cas proteins, such as Cas12, which have been explored for their unique properties in genome editing across different fungal species (Agarwal 2023). The deletion of the negative transcriptional regulator mcrA in Aspergillus wentii led to the differential production of various secondary metabolites. This process revealed new compounds through additional genetic modifications (Yuan et al. 2022). Additionally, the system has been applied to confirm the involvement of specific gene clusters in secondary metabolites biosynthesis, as demonstrated in Lophiotrema sp. F6932, where targeted deletion of the ketosynthase domain in the PAL gene cluster halted the production of palmarumycins (Kwon et al. 2021). Moreover, Innovative approaches like CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) using dCas9‐VPR have further streamlined the activation of silent gene clusters, exemplified by the production of antimicrobial macrophorins in Penicillium rubens (Mózsik, Hoekzema, et al. 2021). The CRISPR/Cas12a‐mediated system, known as CAT‐FISHING, has been developed to efficiently clone large BGCs, facilitating the discovery of new bioactive compounds (Liang et al. 2022). Furthermore, the use of Cas9‐based RNA‐guided synthetic transcription activation systems, such as VPR‐dCas9, has proven effective in activating silent BGCs in Aspergillus nidulans, even in regions of facultative heterochromatin (Nan et al. 2021; Schüller et al. 2020). This approach is helping scientists to explore bigger and more complex clusters that were previously too difficult to work with. In addition to activating new pathways, CRISPR tools are also being used to improve production yields (Ansori et al. 2023). For example, by knocking down competing metabolic pathways using CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), fungi can be guided to focus more resources on producing the desired antimicrobial compounds (Zhao et al. 2021). Multiplexed CRISPR strategies, where several genes are edited or activated simultaneously, are also making it easier to reconstruct entire biosynthetic pathways in a more streamlined way (Zhao et al. 2021).

Overall, the CRISPR/Cas systems are reshaping how we approach fungal secondary metabolism. From activating silent clusters to optimizing production, these tools are creating exciting opportunities to discover new antibiotics and bioactive compounds from fungal sources.

2.4.5. Heterologous Expression

Heterologous expression approach involves transferring BGCs from their native, often genetically intractable or difficult‐to‐cultivate hosts, into more manageable organisms like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Aspergillus nidulans, or Pichia pastoris (Geistodt‐Kiener et al. 2023; Mózsik et al. 2022; Qian et al. 2022). Techniques such as transformation‐assisted recombination and polycistronic vectors have been developed to facilitate the seamless cloning and expression of these gene clusters in heterologous hosts (Y. Xu et al. 2022). For instance, the use of AMA1‐based pYFAC vectors in Aspergillus nidulans has shown high transformation efficiency and compound production, allowing for the evaluation of different pathway intermediates (Roux and Chooi 2022; Kanematsu and Shimizu 2015). Additionally, the refactoring of biosynthetic pathways in engineered hosts like Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus oryzae has led to the successful production of new compounds and the elucidation of biosynthetic pathways (Roux and Chooi 2022; Han et al. 2023). In Figure 1, we visualized the possible modern techniques to increase the expression of BGCs in fungi and boost the production of antibiotics through genetic methods.

2.5. Challenges in Harnessing BGCs From Fungal Genomics

Harnessing BGCs from fungal genomics presents several challenges despite the vast potential for discovering novel bioactive compounds. One primary issue is the difficulty in translating computational predictions of BGCs into actual compounds, as many BGCs remain transcriptionally silent under laboratory conditions, making it hard to identify and activate these pathways (Valiante 2023; D. Wang, Jin, et al. 2023). The regulatory circuits governing the expression of these gene clusters are often unknown, complicating efforts to exploit them in the lab (Keller 2019). Additionally, the sheer volume of data from over 1000 sequenced fungal genomes has yet to be systematically analyzed, which hampers the rational discovery of new compounds (Mohanta and Al‐Harrasi 2021; Schüller et al. 2022). Strategies like synthetic biology approaches are still in their infancy and require further refinement. Co‐expression network approaches need to be integrated more broadly into drug discovery programs to move beyond the BGC paradigm and understand the global regulatory networks involved (Soberanes‐Gutiérrez et al. 2022; S. Xu et al. 2023). Moreover, current BGC discovery tools often overestimate cluster boundaries, necessitating improved methods like reinforcement learning to optimize candidate BGC predictions (Yang et al. 2021; Almeida et al. 2022). While significant progress has been made, the challenges of activating silent BGCs, understanding their regulatory mechanisms, and efficiently mining the vast genomic data must be addressed to fully harness the biosynthetic potential of fungi.

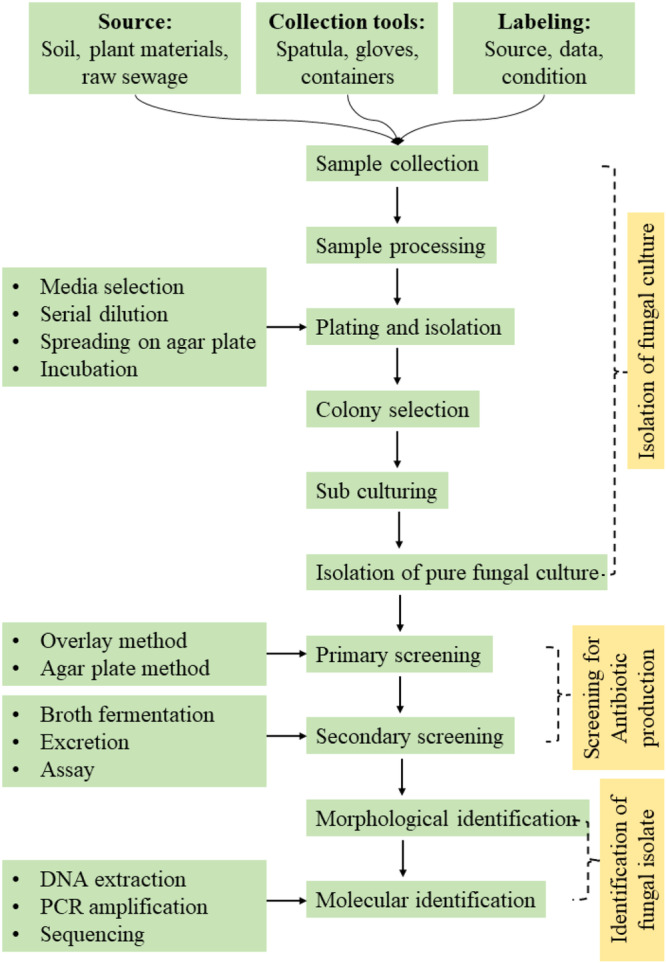

2.6. Isolation and Identification of Antibiotic‐Producing Fungi

The isolation and identification of antibiotic‐producing fungi involve several environmental sources and steps, including sample collection, culturing, and screening for antimicrobial activity. Soil is a rich source of antibiotic‐producing microorganisms, including fungi, which can be isolated using various techniques such as serial dilution and spread plate methods on specific media like Sabouraud Dextrose Agar and Nutrient Agar (Broomfield and Filipa Simões 2019). For instance, fungi isolated from soil samples at Ahmadu Bello University included species like Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Penicillium sp., which showed antimicrobial activity against pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli (Emmanuel and Igoche 2022).

Similarly, fungi from wastewater treatment plants and solid‐state waste sites have been found to produce antibiotics, with species like Penicillium chrysogenum and Aspergillus flavus demonstrating significant inhibitory effects against various bacteria (Verma and Haseena 2022; Dudeja et al. 2020). The identification of these fungi often involves both macroscopic and microscopic characterization, as well as molecular techniques like 18S rRNA gene sequencing (Logan et al. 2023). Additionally, fungi isolated from food products, such as Aspergillus fumigatus from stored sorghum grains, have been identified using molecular techniques (Prathibha et al. 2023). The antibiotic activity of isolated fungi is typically assessed using methods like the agar well diffusion assay and cross‐streaking techniques against a range of test microorganisms, including Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria (Singh et al. 2017; Yahaya et al. 2017). In Figure 2, we have developed a detailed process for identifying antibiotic‐producing fungi, which begins with sampling from various sources (Figure 2). These samples are then cultured under selective conditions designed to favor the growth of fungi with potential antibiotic activity.

Figure 2.

The generalized step‐by‐step process in isolating and discovering novel antibiotic‐producing fungi and characterizing their bioactive compounds.

The antibiotic activity of isolated fungi is initially assessed using classical methods like the agar well diffusion assay and cross‐streaking against Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria (Veeraswamy et al. 2022). However, to improve sensitivity, throughput, and reliability, advanced screening techniques are now being incorporated. Biosensors—analytical devices that combine biological recognition elements with signal transduction—enable real‐time, high‐sensitivity detection of bioactive metabolites (Tong et al. 2023). Meanwhile, high‐throughput screening allows rapid evaluation of large numbers of fungal extracts for antimicrobial properties using automated platforms (Ayon 2023). These modern tools significantly enhance the efficiency of discovering novel antibiotic‐producing strains.

2.7. Innovative Cultivation and Fermentation Strategies

Scaling up fungal production for antibiotic development involves transitioning from laboratory‐scale to industrial‐scale processes efficiently and cost‐effectively (Dutta et al. 2022). Successful scale‐up requires meticulous planning, attention to detail, and preparation for unforeseen challenges, especially during fermentation, which is a costly and critical step impacting downstream processing (Crater and Lievense 2018).

Cultivating fungi like Aspergillus fumigatus in various volumes to optimize secondary metabolite production is essential, with studies focusing on fermentation profiles and agitation speed effects (Tajabadi et al. 2015). Researchers have explored various techniques, the most efficient methods for the large‐scale cultivation of antibiotic‐producing fungi involve a combination of advanced cultivation techniques, optimized nutrient conditions, and innovative screening and monitoring technologies (Table 3). Another promising approach is aerobic submerged fermentation in a liquid medium with particulate anchoring carries has been shown to significantly increase mycelial biomass for large‐scale production (Giang et al. 2018; Farmer 2019). Similarly, microparticle‐enhanced cultivation (MPEC) techniques are particularly effective in overcoming the challenges of bulk fungal growth in bioreactors, improving homogeneity, and enhancing final product concentration without interfering with fungal metabolism (Mule et al. 2010). Different growth media compositions and physical conditions significantly influence the yield and potency of antibiotics produced by fungi. For instance, synthetic media with pure chemical sources are more consistent in penicillin production compared to semi‐synthetic media like potato dextrose agar (Waithaka 2022). The addition of biotic elicitors such as Staphylococcus aureus can extend the log phase growth of fungi like Penicillium sp., enhancing the antibiotic yield when added at specific times during fermentation (Fatima et al. 2019). Studies on Micromonospora sp. strain SMC23 revealed that specific solid media formulation could significantly enhance antibacterial metabolite production against ESKAPE pathogens (Giang et al. 2018).

Table 3.

Scale‐up techniques for fungal antibiotic production.

| Technique/strategy | Fungal strain involved | Reported enhancement in production | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic submerged fermentation with anchoring carriers | Aspergillus fumigatus | 2.5‐fold increase in biomass and metabolite yield | Yang et al. (2021), Almeida et al. (2022) |

| Microparticle‐enhanced cultivation (MPEC) | Penicillium sp. | 1.8–2.2× increase in homogeneity and final product | Emmanuel and Igoche (2022) |

| Synthetic media (pure chemical) versus semi‐synthetic | Penicillium chrysogenum | ~30% higher penicillin yield with synthetic media | Mubarak et al. (2022) |

| Biotic elicitor (Staphylococcus aureus) addition | Penicillium sp. | ~1.5‐fold increase when added at optimal fermentation time | Verma and Haseena (2022) |

| Solid‐state fermentation with optimized media | Micromonospora sp. strain SMC23 | ~2.7× enhancement in activity against ESKAPE pathogens | Yang et al. (2021) |

| Agro‐waste media + glucose and NaNO3 | Aspergillus fumigatus | ~3.1× increase in antibiotic substance production | Dudeja et al. (2020) |

| Ultralow temp. strain storage (mutation prevention) | Multiple strains | Enhanced strain stability over long‐term runs | Logan et al. (2023) |

| In situ metabolite separation | Multiple fungal strains | Reduction in inhibitory metabolite accumulation | Prathibha et al. (2023), Singh et al. (2017) |

| CFD‐guided bioreactor design | Generic industrial fungi | Improved mass/heat transfer; scale‐up reproducibility | Ayon (2023), Crater and Lievense (2018) |

| PAT integration (Raman/MIR/UV–Vis) | Aspergillus, Penicillium | Improved real‐time control and fermentation yield | Waithaka (2022), Fatima et al. (2019), Chanphen et al. (2018) |

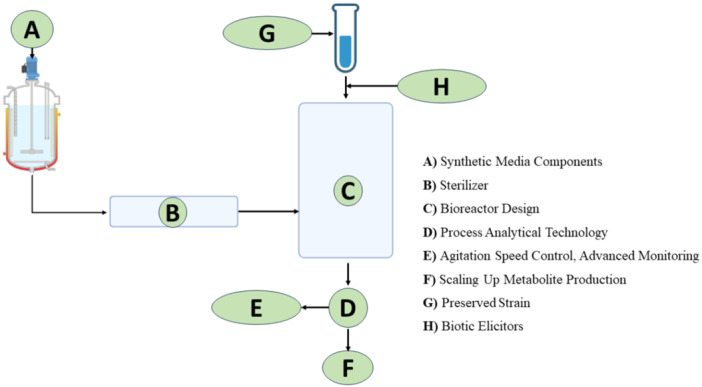

Furthermore, exploring cost‐effective alternatives like the use of agro‐waste‐based media supplemented with glucose and NaNO3 at optimal pH and temperature conditions has been shown to support maximum antimicrobial substance production in fungi like Aspergillus fumigatus (Chanphen et al. 2018). Employing strain prevention might improve production quality, this method involves ultralow temperature storage, which helps maintain strain characteristics and prevent mutations (Serna‐Cock et al. 2012). Additionally, implementing in situ separations in the fermentation process can help remove inhibitory secondary metabolites that may affect DNA stability and lead to downregulated mutations (Tang and Ren 2011; Izzo et al. 2020). Effective bioreactor design for scaling up fungal antibiotic productions, which involves consideration of medium rheology, oxygen transfer, shear stress, and fungal morphology (Kırdök et al. 2022). Scale‐up processes are usually complex, requiring engineers to focus on factors like heat and mass transfer phenomena, medium composition, and mixing time (Gomes et al. 2022). Traditional designs such as stirred tank reactors and bubble columns are commonly used, but new configurations like solid‐state fermentation systems aim to address issues like shear stress and inefficient aeration (Mahdinia et al. 2019). Bioreactor scale‐up challenges are also related to transport processes, with scale‐down techniques and computational fluid dynamics simulations proving valuable in understanding heterogeneities observed in large‐scale tanks (Mayer et al. 2022; Liu 2017). Figure 3 represents the key steps involved in harnessing metabolites during the industrial process. This includes optimizing fungal cultivation conditions and implementing downstream processing for efficient metabolite extraction and purification.

Figure 3.

Procedures for scaling up fungal metabolite production in the biopharmaceutical industry.

Recent advancements focus on implementing control strategies tailored for industrial‐scale biotherapeutic production (Nikita et al. 2023), utilizing metabolic engineering techniques to increase antibiotic yield through genetic modifications and metabolic alterations (S. Gupta et al. 2020). However, the use of anaerobic membrane bioreactors shows promise in treating antibiotic wastewater effectively (Cheng et al. 2018), an optimization method based on Pontryagin's maximum principle and optimal control theory are also employed to determine the best control trajectories for key variables like temperature and substrate feed rate in antibiotic production bioprocesses (de Oliveira 2018).

Process analytical technology (PAT) can be integrated into fungal fermentation processes to enhance scalability and consistency by utilizing advanced monitoring strategies such as spectroscopic measurements and in situ approaches. By employing tools like mid‐infrared (MIR) spectroscopy (McDermott 2023) and in situ Raman and UV/Vis spectroscopy (Gerzon et al. 2022), real‐time monitoring of key parameters like glucose, ethanol, glycerol, and other analytes can be achieved, leading to improved process understanding, control, and reactor efficacy (Pontius et al. 2020). Updating and managing prediction models based on PAT data is crucial to account for variations in the process (Rößler et al. 2020). This integration of PAT not only aligns with modern paradigms like circular economy and sustainability but also supports the development of fungal fermentation processes (Aramouni et al. 2023).

Modern studies using tools like Design‐Expert software, Plackett‐Burman design, and response surface methodology have been employed to identify key factors influencing antibiotic production (Giang et al. 2018). Additionally, strategies like extractive fermentation via in situ ion‐exchange‐based absorptive techniques have been developed to mitigate feedback inhibition and enhance fermentation performance (Talukdar et al. 2016). Overall, these combined approaches may contribute to the efficacy and scalability of fungal antibiotic production processes on an industrial scale.

2.8. Fungal Communication and Regulatory Mechanisms in Antibiotic Development

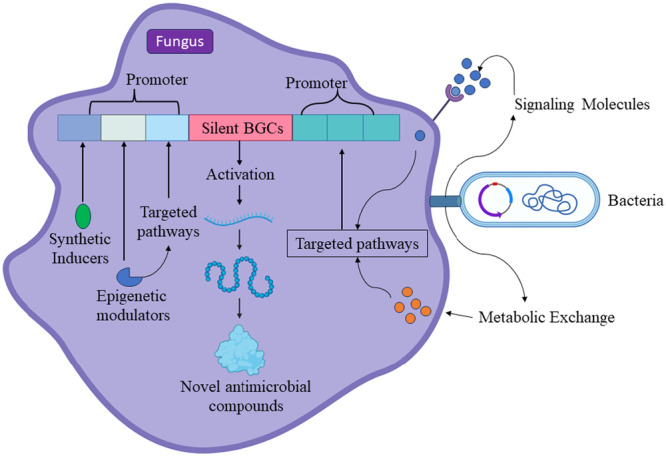

2.8.1. Quorum Sensing and Synthetic Inducers

Quorum Sensing (QS) is a cell‐density‐dependent signaling mechanism that fungi use to regulate various physiological processes, particularly for secondary metabolite production, including antibiotic biosynthesis (Padder et al. 2018). QS involves the release and detection of signaling molecules called autoinducers, such as farnesol and tyrosol (Rodrigues and Černáková 2020). When these molecules reach a critical concentration, they trigger changes in gene expression that activate key mechanisms like MAPK pathway proteins, cAMP–PKA pathways proteins, and BGCs, these pathways collectively boost antibiotic biosynthesis under certain conditions (Li et al. 2023; Polke et al. 2018; Santos‐Pascual et al. 2023).

To improve antibiotic yields, developing synthetic inducers (Kelly et al. 2016) that continuously activating these pathways under specific conditions could be a promising approach. Synthetic inducers are designed to mimic natural QS molecules but offer greater control over activation timing and intensity. For instance, replacing the promoter that derives the expression of transcriptional regulators in a common genome editing strategy to activate genes. This includes overexpressing activators, knocking out repressors, and modifying epigenetic modulators that control chromatin (Brakhage and Schroeckh 2011). While traditional genome editing can upregulate BGSs, recent advances in synthetic biology have introduced new tools like synthetic transcript factors, artificial transcription units, fungal shuttle vectors, and enhanced platform strains for heterologous expression (Mózsik et al. 2022).

2.8.2. Epigenetic Regulation of Antibiotic Production

Epigenetic regulations significantly impact antibiotic production or BGC expression in fungi through mechanisms such as histone modification, DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling, and noncoding RNAs (Xue et al. 2023; Zhgun 2023; X. Wang, Yu, et al. 2023). Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) alter histone acetylation to regulate gene expression, with HDAC inhibitors like vorinostat and sodium butyrate enhancing antibiotic biosynthesis by opening chromatin structure (Giang et al. 2018; Fischer et al. 2017). Similarly, DNA methyltransferases add repressive methyl groups to DNA, while DNA demethylating agents like 5‐azacytidine can reactivate such silent BGCs and secondary metabolites production genes (Wu and Yu 2015). Additionally, chromatin remodeling complexes such as SWI/SNF adjust nucleosome positioning and noncoding RNAs further modulate these processes by directing chromatin‐modifying enzymes to specific loci (Kuwahara et al. 2023; Morse et al. 2023). To boost antibiotic production, focusing on novel epigenetic modulators—like HDAC and HMT inhibitors, DNA methylating agents, and synthetic epigenetic modulators—can provide precise control over fungal secondary metabolite gene expression. Synthetic epigenetic modulators represent a cutting‐edge research field that precisely controls gene expression through targeted modification of epigenetic marks (Carosso et al. 2023; Rittiner et al. 2022). However, delivering these modulators into fungal cells presents significant challenges, mostly because of the complexity of the fungal cell wall. Targeted therapy requires innovative solutions such as nanoparticle carriers or viral vectors to ensure the modulators reach their intended genomic targets (Zhao et al. 2023; Fujita and Fujii 2022).

Figure 4 highlights how synthetic induces can affect QS and other regulators that may boost antibiotic production in fungi.

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of enhanced antibiotic productions in fungi through synthetic molecules and fungal–bacterial interactions.

2.9. Fungal–Bacterial Microbiome Interactions in Antibiotic Discovery

2.9.1. Cross‐Talk Through Signaling Molecules and Coculture Systems

Cross‐talk through signaling molecules plays a crucial role in modulating antibiotic production in the complex microbiome. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) (Vaishnavi et al. 2021) and diffusible signaling factors (DSFs) (Yetgin 2023) significantly impact fungal–bacterial interactions by regulating gene expression and metabolic pathways. The interaction between the bacterium Serratia plymuthica and the fungal pathogen Fusarium culmorum demonstrated that fungal VOCs can induce changes in bacterial gene and protein expression related to motility, signal transduction, and secondary metabolites (Schmidt et al. 2017; Almeida et al. 2023). Again, DSFs from bacteria such as Burkholderia species activate fungal non‐ribosomal peptide synthetase genes, boosting antibiotic synthesis through pathways like the target of rapamycin, high osmolarity glycerol, and calcineurin signaling pathways (Bach et al. 2022; Chen et al. 2021; Tran et al. 2020). Despite understanding these interactions, the exact molecular mechanism remains unclear, offering an opportunity for advanced research.

Furthermore, the fungal–bacterial coculture system also significantly influences antibacterial compound variation and production. For instance, coculturing fungal species with carbapenem‐resistance Klebsiella pneumoniae resulted in bacterial growth inhibition and the induction of fungal secondary metabolites with antibacterial properties (Moubasher et al. 2022). The study suggested that bacteria under chemical stress showed variable responses and induced fungal secondary metabolites. Another recent study indicated that the Streptomyces‐fungus interaction zone in cocultured growth results in antibacterial activity under certain conditions (Nicault et al. 2021). However, the core mechanism and process of activating genes in these interactions are still a growing field of study. Future research could focus on optimizing coculture conditions and employing advanced geniting and metabolic engineering techniques to further maximize the yield of novel antimicrobial compounds.

2.9.2. Bacterial‐Fungal Metabolic Exchange in Complex Microbiome

The metabolic exchange between fungi and bacteria involves the transfer of metabolites that can dominantly influence cellular activity and expression (Baby and Thomas 2021). Bacteria can provide essential precursors for fungal antibiotic biosynthesis, likewise, bacterial production of short‐chain fatty acids (SCFAs) can serve as a precursor for fungal metabolite production, while fungal metabolites can inhibit bacterial competitors (Luu et al. 2023; Gerke et al. 2021; Sun et al. 2022). Metabolic pathways such as the TCA cycle, glycolysis, and amino acid biosynthesis are often involved in these exchanges (Nielsen et al. 2019). As previously discussed, specific molecules such as farnesol and tyrosol play concentration‐dependent crucial roles in these interactions. A high concentration of farnesol reduces bacterial survival and increases the activity of antimicrobial compounds, whereas moderate levels enhance bacterial tolerance (Kong et al. 2017). Tyrosol inhibits virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and disrupts biofilm formation in Streptococcus mutants. Additionally, various active compounds have been discovered through fungal–bacterial co‐cultural systems as the result of metabolic exchange (Arias et al. 2016; Abdel‐Rhman et al. 2015). Notable examples include pestalones an effective bioactive compound against drug‐resistance bacteria, and glionitrin A, an antitumor metabolite (Zhang and Straight 2019).

Such findings suggest that exploring bacterial‐fungal interaction can lead to the discovery of new antibiotics. Future research could focus on optimizing these metabolic interactions through advanced techniques like isotope labeling and metabolomics to track metabolic fluxes and elucidate the pathways involved (Takahashi et al. 2022). Developing fungal strains with enhanced resistance to bacterial degradation enzymes or modifying antibiotic molecules to evade degradation can further improve yields.

2.10. Underexplored Fungi as a Frontier for Novel Antibiotic Sources

Although much attention has been given to common fungal genera like Penicillium and Aspergillus, vast areas of fungal biodiversity remain poorly explored, often referred to as “fungal dark matter” (Naranjo‐Ortiz and Gabaldón 2019). This includes rare, extremophilic, or slow‐growing fungi from underrepresented phyla like Basidiomycota, Zygomycota, or Glomeromycota, many of which inhabit unique ecological niches such as deep‐sea sediments, arid deserts, high‐altitude soils, or symbiotic environments (Rämä and Quandt 2021). Rare and extremophilic fungi, such as deep‐sea isolates and species from underexplored phyla like Basidiomycota or Glomeromycota, have recently shown promise in producing unique antibiotic scaffolds (Sista Kameshwar and Qin 2019). For instance, novel antimicrobial metabolites have been isolated from marine‐derived Emericellopsis and cold‐adapted fungi from Arctic soils, suggesting these niches may harbor untapped chemical diversity (Pan et al. 2024; Agrawal et al. 2023). However, accessing and cultivating these rare fungi is often challenging due to limitations in growth conditions, unculturability, or lack of genomic references. To overcome this, researchers are increasingly using phylogenetic and phylogenomic approaches to trace conserved BGCs across fungal lineages (Ziemert and Jensen 2012; Pizarro et al. 2020), enabling targeted strain selection. Tools like ITS‐guided fungal barcoding (Raja et al. 2017), metagenomic reconstruction, and single‐cell genomics now allow us to detect and classify these fungi even without traditional cultivation. Likewise, metagenomic methods have led to the discovery of novel antibiotics like malacidin and eradacin (Baby and Thomas 2021). By using metagenomic libraries, particularly fosmid‐ and cosmid‐based, researchers can retrieve large DNA fragments that encode entire biosynthetic pathways, aiding in the discovery of novel enzymes and antimicrobial compounds (Mahapatra et al. 2020). Combining these methods with network‐based BGC clustering, AI‐driven genome mining, and dereplication pipelines can systematically narrow down promising candidates for antibiotic production. As these strategies mature, they offer a clearer path for discovering novel antibiotics from the fungal kingdom's most elusive members.

2.11. Technological Advancement and Opportunities for Future Development

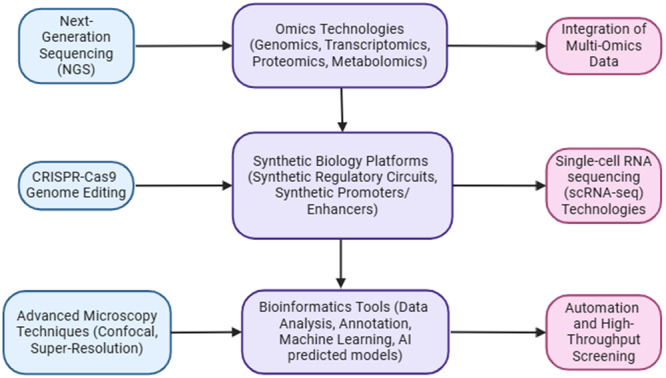

The field of fungal microbiome or mycobiome research for antibiotic discovery has seen remarkable technological advancements. By leveraging these innovations collectively, researchers can address existing challenges and fully exploit the antibiotic‐producing potential of fungal microbiomes (Ribeiro da Cunha et al. 2019). Next‐generation sequencing allows for comprehensive analysis of fungal genetic materials; concurrently, the integration of multi‐omics (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) provides a holistic understanding of fungal metabolism and secondary metabolite production (Palazzotto and Weber 2018; Crofts et al. 2017). This combination enables the identification of new BGCs and regulatory elements involved in antibiotic production. Building on this, CRISPR‐Cas9 genome editing facilitates the precise manipulation of fungal genomes to enhance NP biosynthesis, while synthetic biology platforms design synthetic regulatory circuits and promoters or optimized gene expression (Tong et al. 2023; Song et al. 2022; Singh et al. 2023). Similarly, single‐cell RNA sequencing (scRNA‐seq) reveals the heterogeneity of fungal populations and their regulatory mechanism (Gasch et al. 2017). Advanced microscopy techniques, coupled with bioinformatic tools, allow detailed visualization and analysis of fungal structures and interactions, aiding automation and high‐throughput screening to further streamline the process of identifying promising fungal strains with antibiotic activity (Scanlon et al. 2014; Carey and Heidari‐Torkabadi 2015). On the contrary, artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing antimicrobial discovery by addressing key challenges such as the lengthy and costly development process, low success rates, and the urgent need for novel antibiotics due to rising antibiotic resistance (Lluka and Stokes 2023; Jiménez‐Luna et al. 2021). Figure 5 presents a flowchart that outlines the technological sources and opportunities for future development in harnessing fungal microbiomes for antibiotic discovery.

Figure 5.

Integration of advanced technologies for exploring fungal microbiome for novel antibiotic discovery.

AI techniques, particularly machine learning algorithms, are being employed to reinvigorate traditional antibiotic discovery methods like natural production exploration and small molecule screening. For instance, deep neural networks and multi‐layer perceptrons are used for ligand‐based virtual screening to classify compounds as “active” or “inactive” (Wong et al. 2024; Melo et al. 2021; Oladunjoye et al. 2022). AI also facilitates the discovery and optimization of antimicrobial peptides by using sequence‐based features and evolutionary algorithms to generate peptide libraries with promising biological activity (Agüero‐Chapin et al. 2022; Ruiz Puentes et al. 2022). Moreover, AI‐driven models can predict the mechanism of action (MOA) of new compounds with high accuracy, as demonstrated by the CoHEC model, which uses transcriptome responses to identify novel MOAs in antibiotics (Espinoza et al. 2021). Additionally, AI's role in de novo molecular design and the prediction of drug‐likeness traits further streamline the development pipeline, making it more efficient and cost‐effective (Qureshi et al. 2023; Patel and Shah 2022).

The synergy of these technological advancements holds great promise for optimizing conditions for antibiotic production and discovering novel antibiotics essential for combating antibiotic resistance. Open access to high‐quality screening datasets and interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial for maximizing the potential of these technologies by ensuring a sustainable and effective response to antibiotic resistance globally.

3. Conclusion

Fungi have long proven their value as a source of antibiotics, yet much of their biosynthetic potential remains untapped. In this review, we highlighted the historical contributions of the fungal microbiome to antibiotic discovery and explored how modern tools are opening new possibilities. Advances in genetic engineering, particularly CRISPR/Cas9 systems, promoter engineering, and synthetic biology approaches, are helping researchers unlock silent BGCs and access new secondary metabolites. At the same time, innovations in cultivation methods, such as in situ separation techniques, are making it more feasible to scale up fungal production for industrial applications. Understanding fungal communication systems, such as QS, and exploring fungal–bacterial interactions are emerging as powerful strategies to boost metabolite production. Moving forward, combining genetic, technological, and ecological approaches, along with stronger interdisciplinary collaboration, will be key to overcoming current limitations. Unlocking the full potential of the fungal microbiome could provide urgently needed solutions to the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance and safeguard public health for generations to come.

Author Contributions

Md. Sakhawat Hossain: conceptualization, data curation, writing – original draft, formal analysis. Md. Al Amin: conceptualization, data curation, writing – original draft, formal analysis. Sirajul Islam: data curation, validation, formal analysis. Hasan Imam: formal analysis, validation, data curation. Liton Chandra Das: data curation, formal analysis, validation. Shahin Mahmud: conceptualization, supervision, writing – review and editing.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Md. Sakhawat Hossain and Md. Al Amin contributed equally as first authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- Abdel‐Rhman, S. H. , El‐Mahdy A. M., and El‐Mowafy M.. 2015. “Effect of Tyrosol and Farnesol on Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance of Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa .” BioMed Research International 2015: 456463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelalatif, A. M. , Elwakil B. H., Mohamed M. Z., Hagar M., and Olama Z. A.. 2023. “Fungal Secondary Metabolites/Dicationic Pyridinium Iodide Combinations in Combat Against Multi‐Drug Resistant Microorganisms.” Molecules 28, no. 6: 2434, 10.3390/MOLECULES28062434/S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, C. 2023. A Review: CRISPR/Cas12‐Mediated Genome Editing in Fungal Cells: Advancements, Mechanisms, and Future Directions in Plant‐Fungal Pathology. ScienceOpen. 10.14293/PR2199.000129.V2. [DOI]

- Agrawal, S. , Dufossé L., and Deshmukh S. K.. 2023. “Antibacterial Metabolites From an Unexplored Strain of Marine Fungi Emericellopsis minima and Determination of the Probable Mode of Action Against Staphylococcus aureus and Methicillin‐Resistant S. aureus .” Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry 70, no. 1: 120–129. 10.1002/bab.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agüero‐Chapin, G. , Galpert‐Cañizares D., Domínguez‐Pérez D., et al. 2022. “Emerging Computational Approaches for Antimicrobial Peptide Discovery.” Antibiotics 11, no. 7: 936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, O. A. C. , de Araujo N. O., Dias B., et al. 2023. “The Power of the Smallest: The Inhibitory Activity of Microbial Volatile Organic Compounds Against Phytopathogens.” Frontiers in Microbiology 13: 951130. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.951130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, H. , Tsang A., and Diallo A. B.. 2022. “Improving Candidate Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Fungi Through Reinforcement Learning.” Bioinformatics 38, no. 16: 3984–3991, 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTAC420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves, V. , Zamith‐Miranda D., Frases S., and Nosanchuk J. D.. 2025. “Fungal Metabolomics: A Comprehensive Approach to Understanding Pathogenesis in Humans and Identifying Potential Therapeutics.” Journal of Fungi 11, no. 2: 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amycolatopsis Orientalis 2025. “Amycolatopsis Orientalis—An Overview.” ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed May 11, 2025. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/amycolatopsis-orientalis.

- Ansamycin . 2025. “Ansamycin—An Overview.” ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed May 11, 2025. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/ansamycin.

- Ansori, A. N. , Antonius Y., Susilo R., et al. 2023. “Application of CRISPR‐Cas9 Genome Editing Technology in Various Fields: A Review.” Narra J 3, no. 2: e184. 10.52225/narra.v3i2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramouni, N. A. K. , Steiner‐Browne M., and Mouras R.. 2023. “Application of Process Analytical Technology (PAT) in Real‐Time Monitoring of Pharmaceutical Cleaning Process: Unveiling the Cleaning Mechanisms Governing the Cleaning‐In‐Place (CIP).” Process Safety and Environmental Protection 177: 212–222. 10.1016/j.psep.2023.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arias, L. S. , Delbem A. C. B., Fernandes R. A., Barbosa D. B., and Monteiro D. R.. 2016. “Activity of Tyrosol Against Single and Mixed‐Species Oral Biofilms.” Journal of Applied Microbiology 120, no. 5: 1240–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayon, N. J. 2023. “High‐Throughput Screening of Natural Product and Synthetic Molecule Libraries for Antibacterial Drug Discovery.” Metabolites 13, no. 5: 625. 10.3390/metabo13050625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baby, J. , and Thomas T.. 2021. “A Review on Different Approaches to Isolate Antibiotic Compounds From Fungi.” Italian Journal of Mycology 50: 99–116. 10.6092/issn.2531-7342/12700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bach, E. , Passaglia L. M. P., Jiao J., and Gross H.. 2022. “Burkholderia in the Genomic Era: From Taxonomy to the Discovery of New Antimicrobial Secondary Metabolites.” Critical Reviews in Microbiology 48, no. 2: 121–160. 10.1080/1040841X.2021.1946009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, S. , Funk A. N., Scherlach K., et al. 2010. “Activation of a Silent Fungal Polyketide Biosynthesis Pathway Through Regulatory Cross Talk With a Cryptic Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase Gene Cluster.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 76, no. 24: 8143–8149. 10.1128/AEM.00683-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode, E. , Heinrich A. K., Hirschmann M., et al. 2019. “Promoter Activation in Δhfq Mutants as an Efficient Tool for Specialized Metabolite Production Enabling Direct Bioactivity Testing.” Angewandte Chemie International Edition 58, no. 52: 18957–18963. 10.1002/ANIE.201910563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakhage, A. A. , and Schroeckh V.. 2011. “Fungal Secondary Metabolites—Strategies to Activate Silent Gene Clusters.” Fungal Genetics and Biology 48, no. 1: 15–22. 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broomfield, A. , and Filipa Simões M.. 2019. “ Penicillium spp. Strains as a Possible Weapon to Fight Microbial Infections.” Access Microbiology 1, no. 1A: 429. 10.1099/ACMI.AC2019.PO0249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, T. C. , Feurstein C., Zheng X., et al. 2019. “Functional Exploration of Co‐Expression Networks Identifies a Nexus for Modulating Protein and Citric Acid Titres in Aspergillus niger Submerged Culture.” Fungal Biology and Biotechnology 6, no. 1: 18. 10.1186/S40694-019-0081-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey, P. R. , and Heidari‐Torkabadi H.. 2015. “New Techniques in Antibiotic Discovery and Resistance: Raman Spectroscopy.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1354, no. 1: 67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carosso, G. A. , Yao R. W., Blair Gainous T., et al. 2023. “Discovery and Engineering of Hypercompact Epigenetic Modulators for Durable Gene Activation.” bioRxiv.

- Chanphen, S. , Chanama S., and Chanama M.. 2018. “Growth Medium Condition for Antibiotic Production in Novel Micromonospora Species.” Proceedings of the National and International Conference 9, no. 1: 223–228. Accessed May 21, 2024. http://www.journalgrad.ssru.ac.th/index.php/8thconference/article/view/1230/1122. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, D. , Ngo H. H., Guo W., et al. 2018. “Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactors for Antibiotic Wastewater Treatment: Performance and Membrane Fouling Issues.” Bioresource Technology 267: 714–724. 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.07.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. , Sun T., Bai X., et al. 2021. “Genomics‐Driven Activation of Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Burkholderia Gladioli by Screening Recombineering System.” Molecules 26, no. 3: 700. 10.3390/MOLECULES26030700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chourasia, R. , Chiring Phukon L., Abedin M. M., Padhi S., Singh S. P., and Rai A. K.. 2022. “Bioactive Peptides in Fermented Foods and Their Application: A Critical Review.” Systems Microbiology and Biomanufacturing 3, no. 1: 88–109. 10.1007/S43393-022-00125-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clevenger, K. D. , Bok J. W., Ye R., et al. 2017. “A Scalable Platform to Identify Fungal Secondary Metabolites and Their Gene Clusters.” Nature Chemical Biology 13, no. 8: 895–901. 10.1038/NCHEMBIO.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrado, R. , Gomes T. C., Roque G., and De Souza A. O.. 2022. “Overview of Bioactive Fungal Secondary Metabolites: Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Compounds.” Antibiotics 11, no. 11: 1604. 10.3390/ANTIBIOTICS11111604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crater, J. S. , and Lievense J. C.. 2018. “Scale‐Up of Industrial Microbial Processes.” FEMS Microbiology Letters 365, no. 13: 138. 10.1093/femsle/fny138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofts, T. S. , Gasparrini A. J., and Dantas G.. 2017. “Next‐Generation Approaches to Understand and Combat the Antibiotic Resistome.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 15, no. 7: 422–434. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers, D. H. , Knestrick M. A., Fleeman R., et al. 2018. “Exploitation of Mangrove Endophytic Fungi for Infectious Disease Drug Discovery.” Marine Drugs 16, no. 10: 376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinos, G. P. 2017. “The Macrolide Antibiotic Renaissance.” British Journal of Pharmacology 174, no. 18: 2967–2983. 10.1111/bph.13936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudeja, S. , Chhokar V., Badgujjar H., et al. 2020. “Isolation and Screening of Antibiotic Producing Fungi From Solid‐State Waste.” Polymorphism 4: 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, B. , Lahiri D., Nag M., Ghosh S., Dey A., and Ray R. R.. 2022. “Fungi in Pharmaceuticals and Production of Antibiotics.” In Applied Microbiology, 233–257. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel, A. J. , and Igoche O. P.. 2022. “Isolation and Characterization of Antibiotic Producing Fungi From Soil.” Microbiology Research Journal International 32, no. 9: 28–40. 10.9734/MRJI/2022/V32I91343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eshboev, F. , Karakozova M., Abdurakhmanov J., et al. 2023. “Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activities of the Secondary Metabolites of Endophytic Fungi Isolated From the Medicinal Plant Hyssopus officinalis .” Antibiotics 12, no. 7: 1201. 10.3390/ANTIBIOTICS12071201/S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, J. L. , Dupont C. L., O'Rourke A., et al. 2021. “Predicting Antimicrobial Mechanism‐of‐Action From Transcriptomes: A Generalizable Explainable Artificial Intelligence Approach.” PLoS Computational Biology 17, no. 3: e1008857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etxebeste, O. 2021. “Transcription Factors in the Fungus Aspergillus Nidulans: Markers of Genetic Innovation, Network Rewiring and Conflict Between Genomics and Transcriptomics.” Journal of Fungi 7, no. 8: 600. 10.3390/JOF7080600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer . 2019. Large‐Scale Aerobic Submerged Production of Fungi. LLC. January. 10.1093/FORESTSCIENCE/23.3.363. [DOI]

- Fatima, S. , Rasool A., Sajjad N., Bhat E. A., Hanafiah M. M., and Mahboob M.. 2019. “Analysis and Evaluation of Penicillin Production by Using Soil Fungi.” Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 21: 101330. 10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J. , Müller Y., Netzker T., et al. 2017. Fungal Chromatin Mapping Identifies BasR, as the Regulatory Node of Bacteria‐Induced Fungal Secondary Metabolism.” bioRxiv. 10.1101/211979. [DOI]

- Fleming, A. 1929. “On the Antibacterial Action of Cultures of a Penicillium, With Special Reference to Their Use in the Isolation of B. influenzæ .” British Journal of Experimental Pathology 10, no. 3: 226. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, A. , Forsey R. R., and Usher B.. 1959. “Griseofulvin, A New Oral Antibiotic for the Treatment of Fungous Infections of the Skin.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 81, no. 3: 173–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, T. , and Fujii H.. 2022. “New Directions for Epigenetics: Application of Engineered DNA‐binding Molecules to Locus‐specific Epigenetic Research.” In Handbook of Epigenetics: The New Molecular and Medical Genetics, Third Edition , 843–868. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T. , Cao F., Yu H., and Zhu H. J.. 2017. “Secondary Metabolites From the Marine Fungus Aspergillus Sydowii.” Chemistry of Natural Compounds 53, no. 6: 1204–1207, Nov. 10.1007/S10600-017-2241-7/METRICS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasch, A. P. , Yu F. B., Hose J., et al. 2017. “Single‐Cell Rna Sequencing Reveals Intrinsic and Extrinsic Regulatory Heterogeneity in Yeast Responding to Stress.” PLoS Biology 15, no. 12: e2004050. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geistodt‐Kiener, A. , Totozafy J. C., and Le Goff G.. 2023. “Yeast‐Based Heterologous Production of the Colletochlorin Family of Fungal Secondary Metabolites.” Metabolic Engineering 80: 216–231. 10.1101/2023.07.05.547564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerke, J. , Köhler A. M., Wennrich J. P., et al. 2021. “Biosynthesis of Antibacterial Iron‐Chelating Tropolones in Aspergillus nidulans as Response to Glycopeptide‐Producing Streptomycetes.” Frontiers in Fungal Biology 2: 777474. 10.3389/ffunb.2021.777474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerzon, G. , Sheng Y., and Kirkitadze M.. 2022. “Process Analytical Technologies—Advances in Bioprocess Integration and Future Perspectives.” Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 207: 114379. 10.1016/j.jpba.2021.114379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giang, V. , Nguyen D., and Nguyen T.. 2018. “Improvement of Antibiotic Production in Fungi.” Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology 11, no. 7: 3227. 10.5958/0974-360X.2018.00593.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, D. G. , Coelho E., Silva R., Domingues L., and Teixeira J. A., 2022. “Bioreactors and Engineering of Filamentous Fungi Cultivation.” In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering: Filamentous Fungi Biorefinery, 219–250. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. , Gupta P., and Pruthi V., 2020. “Microbial Production of Antibiotics Using Metabolic Engineering.” In Engineering of Microbial Biosynthetic Pathways. ResearchGate.

- Gupta, A. , Meshram V., Gupta M., et al. 2023. “Fungal Endophytes: Microfactories of Novel Bioactive Compounds With Therapeutic Interventions; A Comprehensive Review on the Biotechnological Developments in the Field of Fungal Endophytic Biology Over the Last Decade.” Biomolecules 13, no. 7: 1038. 10.3390/biom13071038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, H. , Yu C., Qi J., et al. 2023. “High‐Efficient Production of Mushroom Polyketide Compounds in a Platform Host Aspergillus oryzae .” Microbial Cell Factories 22, no. 1: 60, March. 10.1186/S12934-023-02071-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, K. J. , and Kasim A. A.. 2023. “Bioactive Secondary Metabolites Extracted From Some Species of Candida Isolated From Women Infected With Vulvovaginal Candidiasis.” International Journal of Drug Delivery Technology 13, no. 1: 263–267. 10.25258/IJDDT.13.1.42. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hur, J. Y. , Jeong E., Kim Y. C., and Lee S. R.. 2023. “Strategies for Natural Product Discovery by Unlocking Cryptic Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Fungi.” Separations 10: 333. 10.3390/SEPARATIONS10060333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, K. D. , Baldrian P., Chen Y., et al. 2024. “Current Trends, Limitations and Future Research in the Fungi?” Fungal Diversity 125, no. 1: 1–71. 10.1007/s13225-023-00532-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imipenem . 2025. “Imipenem—An Overview.” ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed May 11, 2025. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/imipenem.

- Izuogu, E. S. , Umeokoli B. O., Obidiegwu O. C., et al. 2023. “Screening of Secondary Mmetabolites Produced by a Mangroove‐Derived Nigrospora species: An Endophytic Fungus Isolated From Rhizophora racemosa for Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties.” GSC Advanced Research and Reviews 15, no. 2: 47–60. https://gsconlinepress.com/journals/gscarr/sites/default/files/GSCARR-2023-0133.pdf. [Google Scholar]; 10.30574/GSCARR.2023.15.2.0133. [DOI]

- Izzo, L. , Luz C., Ritieni A., Quiles Beses J., Mañes J., and Meca G.. 2020. “Inhibitory Effect of Sweet Whey Fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum Strains Against Fungal Growth: A Potential Application as an Antifungal Agent.” Journal of Food Science 85, no. 11: 3920–3926. 10.1111/1750-3841.15487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jampilek, J. 2022. “Novel Avenues for Identification of New Antifungal Drugs and Current Challenges.” Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 17, no. 9: 949–968. 10.1080/17460441.2022.2097659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez‐Luna, J. , Grisoni F., Weskamp N., and Schneider G.. 2021. “Artificial Intelligence in Drug Discovery: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives.” Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 16, no. 9: 949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L. Q. , Jin W. R., Ma Z. C., et al. 2019. “Promoter Engineering Strategies for the Overproduction of Valuable Metabolites in Microbes.” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 103, no. 21: 8725–8736. 10.1007/S00253-019-10172-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanematsu, S. , and Shimizu T.. 2015. Transformation of Ascomycetous Fungi Using Autonomously Replicating Vectors, Vol. 2, 161–167. Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-10503-113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karwehl, S. , and Stadler M.. 2016. “Exploitation of Fungal Biodiversity for Discovery of Novel Antibiotics.” Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 398: 303–338. 10.1007/82_2016_496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman, P. A. , Hays E. E., Cain C. K., et al. 1944. “Clavacin, an Antibiotic Substance From Aspergillus clavatus .” Journal of Biological Chemistry 154, no. 2: 475–486. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)71930-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller, N. P. 2019. “Fungal Secondary Metabolism: Regulation, Function and Drug Discovery.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 17, no. 3: 167–180, March. 10.1038/S41579-018-0121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, C. L. , Liu Z., Yoshihara A., et al. 2016. “Synthetic Chemical Inducers and Genetic Decoupling Enable Orthogonal Control of the rhaBAD Promoter.” ACS Synthetic Biology 5, no. 10: 1136–1145. 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I. , Xie W. L., Yu Y. C., et al. 2020. “Heteroexpression of Aspergillus nidulans laeA in Marine‐Derived Fungi Triggers Upregulation of Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Genes.” Marine Drugs 18, no. 12: 652. 10.3390/MD18120652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kırdök, O. , Çetintaş B., Atay A., Kale İ., Akyol Altun T. D., and Hameş E. E.. 2022. “A Modular Chain Bioreactor Design for Fungal Productions.” Biomimetics 7, no. 4: 179. 10.3390/biomimetics7040179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong, E. F. , Tsui C., Kucharíková S., Van Dijck P., and Jabra‐Rizk M. A.. 2017. “Modulation of Staphylococcus aureus Response to Antimicrobials by the Candida Albicans Quorum Sensing Molecule Farnesol.” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 61, no. 12: 10–1128. 10.1128/AAC.01573-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause, J. 2021. “Applications and Restrictions of Integrated Genomic and Metabolomic Screening: An Accelerator for Drug Discovery From Actinomycetes?” Molecules 26, no. 18: 5450. 10.3390/molecules26185450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara, Y. , Iehara T., Matsumoto A., and Okuda T.. 2023. “Recent Insights Into the SWI/SNF Complex and the Molecular Mechanism of hSNF5 Deficiency in Rhabdoid Tumors.” Cancer Medicine 12, no. 15: 16323–16336. 10.1002/cam4.6255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M. J. , Steiniger C., Cairns T. C., et al. 2021. “Beyond the Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Paradigm: Genome‐Wide Coexpression Networks Connect Clustered and Unclustered Transcription Factors to Secondary Metabolic Pathways.” Microbiology Spectrum 9, no. 2: e00898‐21. 10.1128/SPECTRUM.00898-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal, K. , Rojas E., Madariaga D., et al. 2024. “Unlocking Fungal Potential: The CRISPR‐Cas System as a Strategy for Secondary Metabolite Discovery.” Journal of Fungi 10, no. 11: 748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M. , Liu L., Xu F., et al. 2022. “Activating Cryptic Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Through a CRISPR–Cas12a‐mediated Direct Cloning Approach.” Nucleic Acids Research 50, no. 6: 3581–3592. 10.1093/NAR/GKAC181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. , Chen Z., Liu W., Ke X., Tian X., and Chu J.. 2022. “Cephalosporin C Biosynthesis and Fermentation in Acremonium chrysogenum .” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2022 10619 106, no. 19: 6413–6426, Sep. 10.1007/S00253-022-12181-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. 2017. “Bioreactor Design Operation.” Bioprocess Engineering: 1007–1058. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63783-3.00017-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. S. , Huang R., Zhang S. P., Xu T. C., Hu K., and Wu S. H.. 2022. “Antimicrobial Secondary Metabolites From an Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus polyporicola .” Fitoterapia 162: 105297. 10.1016/J.FITOTE.2022.105297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. , Pan Y., Zhang S., et al. 2023. “Quorum Sensing: Cell‐to‐Cell Communication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae .” Frontiers in Microbiology 14: 1250151. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1250151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lluka, T. , and Stokes J. M.. 2023. “Antibiotic Discovery in the Artificial Intelligence Era.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1519, no. 1: 74–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan, M. , Cantlay S., and Horzempa J.. 2023. “The Identification of Fungal Isolates Capable of Inhibiting Growth of Methicillin‐Resistant Staphylococcus aureus .” Proceedings of the West Virginia Academy of Science 95, no. 2: 95. 10.55632/PWVAS.V95I2.972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luu, G. T. , Little J. C., Pierce E. C., et al. 2023. “Metabolomics of Bacterial‐Fungal Pairwise Interactions Reveal Conserved Molecular Mechanisms.”Analyst 148, no. 13: 3002–3018. 10.1039/d3an00408b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, G. P. , Raman S., Nayak S., Gouda S., Das G., and Patra J. K.. 2020. “Metagenomics Approaches in Discovery and Development of New Bioactive Compounds From Marine Actinomycetes.” Current Microbiology 77, no. 4: 645–656. 10.1007/s00284-019-01698-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdinia, E. , Cekmecelioglu D., and Demirci A.. 2019, Bioreactor Scale‐Up.” In Essentials in Fermentation Technology, 213–236. ResearchGate. 10.1007/978-3-030-16230-6_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Matos, R. M. , Pereira B. V. N., Converti A., Duarte C. A. L., and Marques D. A. V.. 2023. “Bioactive Compounds of Filamentous Fungi With Biological Activity: A Systematic Review.” Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental 17, no. 2: e03423. 10.24857/rgsa.v17n2-020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Mattos‐Shipley, K. M. J. , Foster G. D., and Bailey A. M.. 2017. “Insights Into the Classical Genetics of Clitopilus passeckerianus—The Pleuromutilin Producing Mushroom.” Frontiers in Microbiology 8, no. Jun: 257177. 10.3389/FMICB.2017.01056/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F. , Cserjan‐Puschmann M., Haslinger B., et al. 2022. “Using Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation Improves the Design and Subsequent Characterization of a Plug‐Flow Type Scale‐Down Reactor for Microbial Cultivation Processes.” Biotechnology Journal 18: 2200152. 10.22541/AU.164873609.98488183/V1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, L. 2023. “Process Analytical Technology (PAT) Model Lifecycle Management.” Spectroscop) 38: 9–13. 10.56530/spectroscopy.pk3974j5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melo, M. C. R. , Maasch J. R. M. A., and de la Fuente‐Nunez C.. 2021. “Accelerating Antibiotic Discovery Through Artificial Intelligence.” Communications Biology 4, no. 1: 1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanta, T. K. , and Al‐Harrasi A.. 2021. “Fungal Genomes: Suffering With Functional Annotation Errors.” IMA Fungus 12, no. 1: 32, Nov. 10.1186/S43008-021-00083-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse, K. , Swerdlow S., and Ünal E.. 2023. “Swi/Snf Chromatin Remodeling Regulates Transcriptional Interference and Gene Repression.” bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mosunova, O. V. , Navarro‐Muñoz J. C., Haksar D., et al. 2022. “Evolution‐Informed Discovery of the Naphthalenone Biosynthetic Pathway in Fungi.” mBio 13, no. 3: e00223‐22. 10.1128/mbio.00223-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moubasher, H. , Elkholy A., Sherif M., Zahran M., and Elnagdy S.. 2022. “In Vitro Investigation of the Impact of Bacterial–Fungal Interaction on Carbapenem‐Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae .” Molecules 27, no. 8: 2541. 10.3390/molecules27082541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mózsik, L. , Hoekzema M., de Kok N. A. W., Bovenberg R. A. L., Nygård Y., and Driessen A. J. M.. 2021. “CRISPR‐Based Transcriptional Activation Tool for Silent Genes in Filamentous Fungi.” Scientific Reports 11, no. 1: 1118. 10.1038/S41598-020-80864-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mózsik, L. , Iacovelli R., Bovenberg R. A. L., and Driessen A. J. M.. 2022. “Transcriptional Activation of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Filamentous Fungi.” Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 10: 901037. 10.3389/fbioe.2022.901037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mózsik, L. , Pohl C., Meyer V., Bovenberg R. A. L., Nygård Y., and Driessen A. J. M.. 2021. “Modular Synthetic Biology Toolkit for Filamentous Fungi.” ACS Synthetic Biology 10, no. 11: 2850–2861. 10.1021/ACSSYNBIO.1C00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubarak, F. , Hendrarti W., Abidin H. L., and Bakar A. A.. 2022. “Identification of Antibiotic‐Producing Isolates From the Soil of Pesantren Darul Aman Gombara, Makassar.” Indonesian Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology 9, no. 3: 181. 10.24198/IJPST.V9I3.32257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mule, A. , Patil R. C., Jadhav U., Katchi V. I., Rao A. J., and Gaikwad S. K.. 2010. “Large Scale Production of Oxytetracyclin Using Streptomyces varsovances .” Biosciences Biotechnology Research Asia 7, no. 2: 813–818. [Google Scholar]