Abstract

Skin cancer, particularly melanoma, is a major health concern due to rising incidence rates, largely driven by ultraviolet (UV) radiation overexposure, making it essential to monitor and manage sun exposure effectively. While existing wearable UV sensors track exposure, they often rely on external power sources, limiting their battery lifetime. This study presents a self-sustaining wearable UV sensor that integrates solar energy harvesting, enabling continuous monitoring without need for frequent recharging. The device uses low-power components to measure UVA and UVB radiation with high accuracy. It is powered by a solar panel made from Ethylene Tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE), which provides continuous energy to recharge a LiPo battery. It transmits data via BLE for real-time feedback and can be used for personalized sun protection recommendations. A usability study with 10 participants demonstrated the sensor’s effectiveness in raising UV awareness and encouraging sun protection habits.

I. Introduction

Skin cancer has been a significant global health problem, with melanoma representing a particularly concerning aspect due to its severity [1]. Although melanoma is the least common type of skin cancer, it can be one of the deadliest [2]. Over the years, there has been a steady increase in melanoma diagnoses [3], rising from 59,944 in 2007 in the U.S., to 100,000 in 2024. The primary factor contributing to skin cancer is over-exposure to the sun [4]. A moderate level of sun exposure is encouraged for the body to generate Vitamin D, which is necessary for strong bones and overall health. However, exposure to the sun for too long and without any protection can cause skin problems, which may lead to skin cancer and further contribute to the economic burden of the cost of treatment [5], [6]. Hence, it is crucial to raise public awareness regarding UV exposure and skincare while also providing tools to manage sun over- and underexposure.

Wearable sensors provide passive and continuous solutions to monitor UV exposure in real-time. UV estimates are traditionally captured using UV dosimeters, such as dye-based sticker dosimeters, electronic UV dosimeters, and radiometers [5]. While the dye-based UV sticker is skin-mounted, unobtrusive, and low-cost, the disadvantage of the dye-based approach is that it is hard to collect accurate UV values since it uses photosensitive dyes to detect color changes when exposed to UV rays. Those color changes might be hard for human beings to interpret. By contrast, most wearable sensors are lightweight and small, and they can record instantaneous and accumulated UV dose to determine UV risk [5]. However, traditional UV devices often depend on battery power, which presents challenges for maintenance and continuous use, particularly in resource-limited settings. Recent work by Yang and Rosa [7] introduced a battery-free wearable device using Near Field Communication (NFC) to harvest energy from a mobile phone. While promising, this approach requires close proximity to the energy source, limiting its ability for continuous monitoring.

Despite advancements in UV dosimeters and battery-free sensors, significant gaps remain. Many wearable UV sensors require periodic recharging, disrupting continuous monitoring [8]. Therefore, developing a self-sustaining UV sensor is essential for real-time, uninterrupted monitoring. Self-sustaining devices provide a solution for supplying power to electronic devices used in healthcare applications [9]. Harvesting energy from an outside readily available environmental source could help recharge the device without using internal power. This would help with uninterrupted monitoring and greater user compliance.

In this paper, we examine participants’ UV exposure across various environments (indoor, close to a window, outdoor, and outdoor in the shade). We hypothesize that a self-sustaining wearable UV sensor, that can distinguish across different UV risks both indoor and outdoor, can provide added value when providing user feedback and advice. The invisibility nature of UV radiation poses a significant challenge, as highlighted by Dumont et al. [10]: People often unknowingly accumulate UV exposure upon stepping outside, leading to insufficient awareness of the risks of prolonged sun exposure, which can cause adverse skin conditions. To address this issue, we propose the development and implementation of a self-sustaining wearable UV sensor to continuously monitor UV levels in different scenarios and to send reminders for sun protection when high UV exposure is detected. This approach aims to enhance user adherence to sun protection measures, increase overall awareness of UV exposure risks, and reduce the incidence of sunburn and related skin problems.

II. Method

Figure 1 provides an overview of our framework, which includes the electronics, 3D-designed enclosure, and notification mechanism that can trigger users to provide sun protection information or protect themselves from UV exposure when necessary. We first discuss the device, followed by details regarding the usability study.

Fig. 1.

A. Hardware components; B. 3D Design, and enclosure; C. Form Factors: wrist-worn, hat worn, arm and chest mount; D. UV notification triggers.

A. System Design

The main design focus of our system is to support all-day, real-time UV dose detection. To achieve this, we adhered to two core principles: ease of use and energy efficiency. We designed a low-cost, lightweight sensing device. The device measures the wearer’s current UV exposure with a 1 Hz sampling frequency. Simultaneously, the solar panel continuously harvests energy and stores it in the LiPo battery. The measured data is written to flash memory for subsequent analysis and integration. If the wearer wishes to view real-time UV data, the device can use BLE to transmit the UV values and provide suggestions in real time.

The system is built around the nRF52840 System on Chip (SoC) featuring a 32-bit processor with FPU, 64 MHz clock speed, 2 MB onboard flash, and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) for enabling real-time feedback. Additionally, the system incorporates the AS7331 UV sensor, which measures UV radiation across three channels: UVA (λ : 315–400 nm), UVB (λ : 280–315 nm), and UVC (λ : 100–280 nm) with high sensitivity and accuracy. Concurrently, the Voltaic P122 solar panel, constructed from durable ETFE (Ethylene Tetrafluoroethylene), supplies energy continuously, recharging and powering the system. This panel is notably robust and capable of withstanding physical stresses such as drops and pressure. The power harvested by the solar panel can be calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

where represents the total power output of the solar panel, is the amount of solar power received per unit area (measured in watts per square meter, W/m2). This is the only variable that affects the amount of energy we harvest. corresponds to the effective area of the solar panel (measured in square meters, m2), while indicates the efficiency at which the solar panel converts the received solar energy into electrical power. By multiplying these factors together, we can determine the solar panel’s total power under specific solar irradiance conditions.

| (2) |

By subtracting the energy consumed by the device from the energy harvested , we obtain the net energy balance . To ensure efficient power management, we employed the bq24074 solar charger. This charger utilizes a linear converter, providing heightened efficiency at lower voltages and currents, thus aligning with our lightweight sensor’s requirements. The support circuitry also includes a 350 mAh rechargeable LiPo battery, which works with solar panels to provide all-day battery life.

B. Usability Study

1). Participants:

We recruited 11 participants for this study, 5 identified as female (one dropped out post-experiment), and the remainder as male.

2). Procedures:

Participants were asked to wear the UV sensor on their wrists during the experiment. Before wearing devices and starting the experiment, participants completed a pre-experiment questionnaire designed to assess their UV knowledge and sun habits. The pre-experiment questionnaire is separated into four parts: demographic information, knowledge about UV radiation, sun protection habits, and health risk awareness. The first part collects data about their demographic information. The second section assessed general awareness and understanding of UV radiation. The third documented participants’ sun habits outdoors, e.g., whether they use sunscreen, wear protective clothing, or seek shade. Finally, we evaluated participants’ knowledge of health risks associated with UV exposure. Following the pre-experiment questionnaire, participants were asked to wear the device on the wrist and walk outside following a predetermined path that exposed them to various UV levels. The path included indoor locations, areas near windows, outdoor spaces, and shaded outdoor areas. Upon completion of the experiment, participants were presented with a real-time UV plot collected by the sensor, and the test experimenter explained the graph range of UV between indoors and outdoors. After data export and analysis, participants completed post-experiment questionnaire, which ask how likely they will use sun protection methods after learning about the UV risks, as well as their perception of the importance of educating others about UV radiation risks. Detailed questions from the experiment questionnaire and analysis are shown in Figure 2.

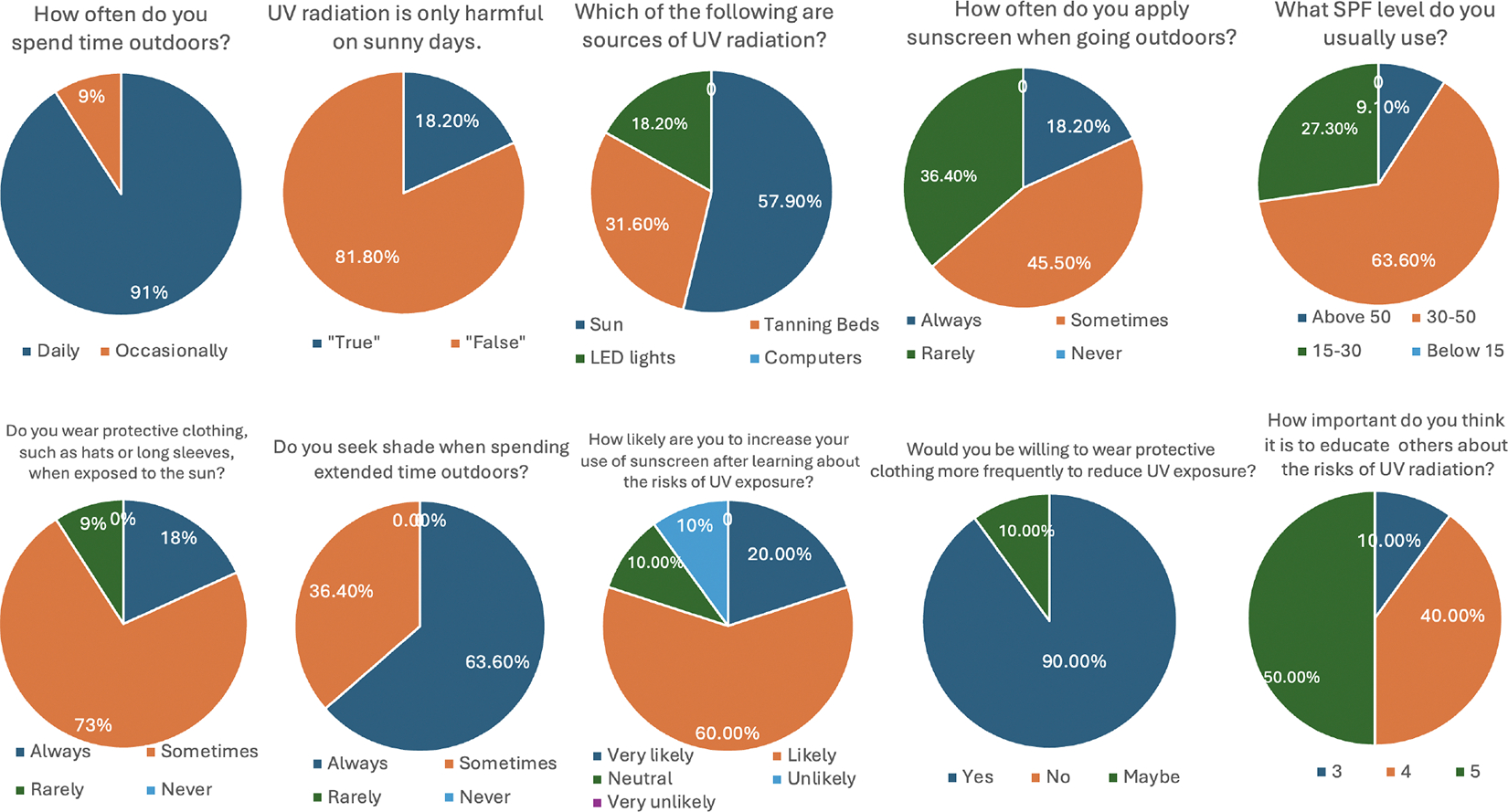

Fig. 2.

Results from Pre-Experiment Q1-Q7 and Post-Experiment Q1-Q3

III. Results

A. Energy Evaluation

1). Experimental Setup:

To measure the systems harvested and consumed energy in various states, we employed the INA219 current sensor to monitor the energy in our self-sustaining system. The current sensor was positioned between the battery and the rest of the components. Therefore, we measure how much energy is consumed from or charged into the battery. Data were sampled for 30 minutes for each state at a frequency of 50 Hz. We then determine each state’s average current and power (as shown in Tables I and II) and multiply the average power by the time duration the device spends in each state to estimate energy.

TABLE I.

Power and Current Consumption

| Operation | Sensing | Flash | BLE | SD | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Power (mW) | 11.27 | 17.82 | 12.34 | 27.63 | 17.27 |

| Current (mA) | 2.69 | 4.42 | 3.16 | 7.22 | 4.37 |

TABLE II.

Energy Harvesting Based on Device Orientation

| Orientation | Front | Side | Back | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Power (mW) | 186.79 | 46.48 | 19.87 | 84.38 |

| Current (mA) | 45.25 | 11.23 | 4.71 | 20.40 |

2). Consumed and Harvested Energy Experiments:

For power consumption measurements, we evaluated energy usage in four scenarios: (1) sensing UV data only, (2) sensing UV data while writing to flash memory, (3) sensing UV data while transmitting via BLE, and (4) sensing UV data while storing on an SD card. All of these operations were performed at a 1 Hz sampling frequency for UVA and UVB. Additionally, we evaluated energy harvesting under three distinct conditions outdoors: the device facing the sun directly, the device oriented sideways to the sun, and the device positioned away from the sun. This comprehensive assessment enables us to simulate energy consumption and harvesting efficiency in potential real-world scenarios. By testing these orientations, we aimed to understand device performance in typical usage situations, ensuring reliable energy capture and data transmission regardless of the wearer’s movements or environmental conditions. Table II shows the result of harvested energy in these outdoor scenarios. We observed that even when the wearer’s sensor was oriented away from the sun (back), the harvested energy was sufficient for sensing, writing data into the flash memory, or transmitting data via BLE.

Based to Equation 2, the system exhibits a net positive power profile of +67.11 mW when outdoors, indicating that the system harvests more energy than it consumes. While the device does not harvest significant energy indoors, it can still continue operating using the energy stored from outdoor exposure. For instance, a user spending 3 hours outdoors on a sunny day would accumulate approximately 201 mWh of net energy, sufficient to operate the system for over 11 hours (201 mWh / 17.27 mW).

B. Usability Study Results

Figure 2 illustrates the results from Pre-Experiment Q1-Q7 and Post-Experiment Q1-Q3, revealing several key findings. According to the study, 90.9% of participants spend time outdoors daily. Most participants are aware that the sun is a source of UV radiation and that UV radiation is harmful to the skin. However, only 18.2% consistently apply sunscreen and wear protective clothing, while 36.4% never use sunscreen outdoors. Notably, 63.6% of participants seek shade when spending extended periods outdoors, which helps reduce overexposure to UV radiation. In addition, we gathered data on changes in participants’ UV awareness from the postexperiment questionnaire. The results indicate that 70% of participants are likely to increase their use of sunscreen after learning about the risks of UV exposure. Additionally, 90% expressed a willingness to wear protective clothing more frequently to reduce UV exposure. When asked to rate the importance of educating others about the risks of UV radiation on a scale of 0 to 5, 40% of participants rated it as 4, while 50% rated it as 5, emphasizing the high importance they place on raising awareness about potential UV radiation risks.

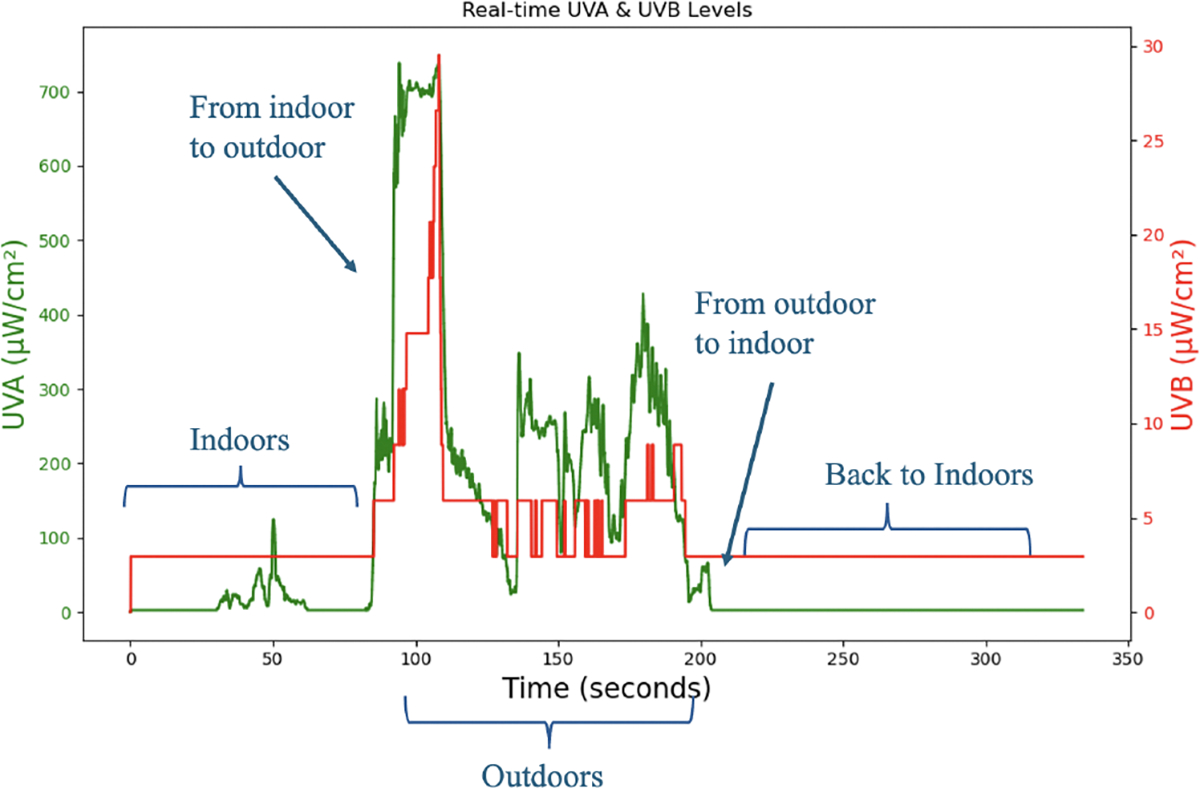

Figure 3 shows the real-time UVA and UVB levels recorded during the experiment, capturing the user’s transition between different environments and triggering notifications for sun protection. During the outdoor period, exposure levels fluctuate due to movement, shading, or glass reflections. Ultimately, from the observations mentioned, we discovered that by providing real-time feedback and increasing awareness, our self-sustaining wearable UV sensor can play a pivotal role in preventing skin cancer and other UV-related health issues.

Fig. 3.

Collected UVA and UVB data in different conditions

IV. Conclusion and Future Work

This study introduces a self-sustainable wearable UV sensor that integrates solar energy harvesting for passive and continuous monitoring of UVA and UVB radiation. By utilizing a solar panel made from ETFE and a low-power sensor system, the device remains operational without recharging, providing real-time UV dose detection and feedback. A usability study with 10 participants demonstrated the device’s effectiveness in raising awareness about UV risks and encouraging proactive sun protection behaviors. Results indicated that the self-sustaining sensor effectively monitored UV exposure and promotes healthier practices. Future work includes expanding the participant pool and incorporating additional features, such as an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), to improve accuracy by differentiating users’ stationary and moving conditions. Moreover, a companion mobile application will be developed to allow users to input relevant information, such as sunscreen application and clothing choices, thereby enabling more customized and precise real-time UV monitoring tailored to individual behaviors.

V. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This material is based upon work supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) under award numbers K25DK113242, R03DK127128, R21EB030305, R01DK129843, and R34CA283480.

REFERENCES

- [1].Lopes J, Rodrigues CMP, Gaspar MM, and Reis CP, “Melanoma Management: From Epidemiology to Treatment and Latest Advances,” Cancers, vol. 14, no. 19, p. 4652, Sep. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9562203/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Saginala K, Barsouk A, Aluru JS, Rawla P, and Barsouk A, “Epidemiology of melanoma,” Medical sciences, vol. 9, no. 4, p. 63, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].“2024 Melanoma Facts & Statistics” [Online]. Available: https://www.aimatmelanoma.org/facts-statistics/

- [4].Stump TK, Fastner S, Jo Y, Chipman J, Haaland B, Nagelhout ES, Wankier AP, Lensink R, Zhu A, Parsons B, Grossman D, and Wu YP, “Objectively-Assessed Ultraviolet Radiation Exposure and Sunburn Occurrence,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 20, no. 7, p. 5234, Jan. 2023, number: 7 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/7/5234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Huang X and Chalmers AN, “Review of Wearable and Portable Sensors for Monitoring Personal Solar UV Exposure,” Annals of Biomedical Engineering, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 964–978, Mar. 2021. [Online]. Available: 10.1007/s10439-020-02710-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Blumthaler M, “UV Monitoring for Public Health,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 15, no. 8, p. 1723, Aug. 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6121668/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yang GZ and Rosa BM, “A wearable and battery-less device for assessing skin hydration level under direct sunlight exposure with ultraviolet index calculation,” in 2018 IEEE 15th International Conference on Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks (BSN). IEEE, 2018, pp. 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hussein D, Bhat G, and Doppa JR, “Adaptive Energy Management for Self-Sustainable Wearables in Mobile Health,” Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 11 935–11 944, Jun. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/21451 [Google Scholar]

- [9].Xu C, Song Y, Han M, and Zhang H, “Portable and wearable self-powered systems based on emerging energy harvesting technology,” Microsystems & Nanoengineering, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Mar. 2021, publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41378-021-00248-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dumont ELP, Kaplan PD, Do C, Banerjee S, Barrer M, Ezzedine K, Zippin JH, and Varghese GI, “A randomized trial of a wearable UV dosimeter for skin cancer prevention,” Frontiers in Medicine, vol. 11, p. 1259050, Mar. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10940533/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]