Abstract

IscS and IscU from Escherichia coli cooperate with each other in the biosynthesis of iron-sulfur clusters. IscS catalyzes the desulfurization of l-cysteine to produce l-alanine and sulfur. Cys-328 of IscS attacks the sulfur atom of l-cysteine, and the sulfane sulfur derived from l-cysteine binds to the Sγ atom of Cys-328. In the course of the cluster assembly, IscS and IscU form a covalent complex, and a sulfur atom derived from l-cysteine is transferred from IscS to IscU. The covalent complex is thought to be essential for the cluster biogenesis, but neither the nature of the bond connecting IscS and IscU nor the residues involved in the complex formation have been determined, which have thus far precluded the mechanistic analyses of the cluster assembly. We here report that a covalent bond is formed between Cys-328 of IscS and Cys-63 of IscU. The bond is a disulfide bond, not a polysulfide bond containing sulfane sulfur between the two cysteine residues. We also found that Cys-63 of IscU is essential for the IscU-mediated activation of IscS: IscU induced a six-fold increase in the cysteine desulfurase activity of IscS, whereas the IscU mutant with a serine substitution for Cys-63 had no effect on the activity. Based on these findings, we propose a mechanism for an early stage of iron-sulfur cluster assembly: the sulfur transfer from IscS to IscU is initiated by the attack of Cys-63 of IscU on the Sγ atom of Cys-328 of IscS that is bound to sulfane sulfur derived from l-cysteine.

Iron-sulfur proteins are widely distributed in almost all organisms and play essential roles in energy metabolism, DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, and biosynthesis of nucleotides and amino acids (1, 2). Although their prosthetic groups, iron-sulfur clusters, have been the focus of genetic, biochemical, and biophysical studies, little is known about the mechanism of their biosynthesis and repair. Recent studies demonstrated that the assembly of the clusters is mediated by proteins encoded by the isc (iron-sulfur cluster) operon in prokaryotes (3–7), such as Escherichia coli and Azotobacter vinelandii, and counterparts of these proteins in eukaryotes (8, 9). Among these proteins, IscS and IscU are believed to function in an early stage of the cluster assembly. IscS, which is a homodimeric pyridoxal phosphate-dependent cysteine desulfurase, catalyzes the production of sulfur and l-alanine from l-cysteine via an enzyme-bound persulfide intermediate on the active-site cysteine residue, Cys-328 in the case of IscS from E. coli (10, 11). The sulfur atom derived from l-cysteine is then transferred to IscU and eventually incorporated into iron-sulfur clusters. E. coli IscU has three conserved cysteine residues, Cys-37, Cys-63, and Cys-106 and provides a scaffold for the IscS-directed sequential assembly of labile [Fe2S2]2+ and [Fe4S4]2+ clusters (12, 13).

Recently, it was demonstrated that the sulfur atom derived from l-cysteine is transferred directly from IscS to IscU via the formation of an IscS/IscU covalent complex (14, 15). IscS and IscU form the covalent bond complex when mixed with each other in the presence of l-cysteine, the substrate for IscS (14, 15). The sulfur atom derived from l-cysteine is transferred to IscU and forms a covalent bond with IscU. These observations suggest that the sulfur transfer from IscS to IscU occurs in an early stage of the cluster assembly, and its mechanistic analysis is essential in dissecting the cluster assembly process. However, at present, neither the nature of the covalent bond (whether the bond is a disulfide bond or a polysulfide bond) nor the residues involved have been clarified. The composition of the complex has not even been determined. Accordingly, it has been impossible to describe the sulfur transfer process at a molecular level. In the present study, we have shown that IscS and IscU are covalently bound to each other by a disulfide bond and that the residues forming this bond are Cys-328 of IscS and Cys-63 of IscU. We also found a novel phenomenon that IscU promotes the cysteine desulfurase activity of IscS, which requires Cys-63 of IscU. Based on these findings, we propose a mechanism for the sulfur transfer reaction from IscS to IscU.

Experimental Procedures

Materials.

His⋅bind resin was purchased from Novagen. Lysyl endopeptidase and 4-fluoro-7-sulfamoylbenzofurazan (ABD-F) were purchased from Wako (Osaka, Japan). CDP-Star was purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland), Sep-Pak and Centricon YM-10 were from Millipore, and Capcell Pak C18 SG300 (4.6 mm × 250 mm) was from Shiseido (Tokyo, Japan). The Silver stain kit was purchased from Bio-Rad. All other chemicals were of analytical grade from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto).

Expression and Purification of Proteins.

The iscU gene was amplified from the Kohara miniset clone No. 430 (16) by PCR and inserted into the NdeI and XhoI sites in pET21a(+) to yield pUH12, which was used for the expression of IscU-His6. The recombinant protein contains six histidine residues at the C terminus of IscU. For the coexpression of IscU-His6 and IscS, a DNA fragment containing the iscU-iscS coding region was obtained by PCR and inserted into the NdeI and XhoI sites in pET21a(+) to yield pFH6. To produce three mutants of IscU (C37S, C63S, and C106S) and a C328A mutant of IscS, the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit was used with appropriate mutagenic primers. E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells harboring an expression plasmid were cultured aerobically in 500 ml of LB broth supplemented with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, 200 μg/ml of ampicillin, and 40 μg/ml of chloramphenicol at 37°C for 12 h or at 26°C for 20 h in the case of coexpression. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g); suspended in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.9), 0.5 M NaCl, and 5 mM imidazole; and disrupted by sonication. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation (10,000 × g), and the supernatant solution was applied to a nickel-chelating column (Ni-charged IDA agarose) (7 ml) and washed with 100 ml of a binding buffer [20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH7.9)/0.5 M NaCl/5 mM imidazole] and 250 ml of a washing buffer [20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.9)/0.5 M NaCl/60 mM imidazole]. Proteins retained in the column were eluted with 25 ml of an elution buffer [20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.9)/0.5 M NaCl/1 M imidazole].

Identification of Residues Forming a Covalent Bond Between IscS and IscU.

The copurified IscS/IscU complex (14 mg of protein) was incubated in an alkylation mixture (3 ml) containing 0.15 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.8), 6 M urea, 2% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, and 4 mM iodoacetic acid for 2 h at 37°C in the dark. The reaction mixture was dialyzed, concentrated with Centricon YM-10, and digested with lysyl endopeptidase (15 μg) at 37°C for 4 h in 1 ml of a reaction mixture containing 0.1 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 4 M urea, and 5 mM EDTA. The peptides were purified with a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge, concentrated by evaporation, and resuspended in 300 μl of 30% acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The samples were applied onto the Capcell Pak C18 HPLC column equilibrated with 20% acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, and the column was washed with the same buffer. The peptides were separated with a 50-min linear gradient from 20% to 100% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and monitored by UV absorption at 215 nm. Each peak was recovered, evaporated, and resuspended in 200 μl of a labeling mixture containing 0.1 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM EDTA, and 0.5 mM ABD-F. The labeling reaction was performed for 5 min at 50°C in the presence or absence of 1 mM tributylphosphine (TBP). The relative fluorescence of each fraction was measured at 520 nm with excitation at 380 nm, and a fraction that gave high fluorescence intensity was reanalyzed by HPLC. The peptides were recovered, and the primary structures were determined with an automated protein sequencer.

Other Analytical Methods.

Western-blot analysis was carried out by using anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to alkaline phosphatase and a CDP-Star detection reagent. S0 was determined by cyanolysis according to the method of Wood (17). The activity of IscS was determined as described (18). Protein was measured with the protein assay CBB solution (Nacalai Tesque) by using BSA as a standard. N-terminal amino acid sequences were determined with a Shimadzu PPSQ-10 protein sequencer. The nucleotide sequences were determined with an ABI Prism 310 DNA sequencer. Protein bands in an SDS/PAGE gel were quantified with the NIH image software.

Results

IscS and IscU Are Covalently Linked by a Disulfide Bond.

IscU-His6 was recombinantly expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS harboring pUH12, and the cell-free extract was subjected to nickel-chelating column chromatography. IscU-His6 was copurified with a 45-kDa protein, which was identified as IscS by N-terminal amino acid sequencing, indicating the specific interaction between the two proteins (data not shown). As a negative control, we applied the cell extract not containing IscU-His6 onto the nickel column and found that IscS did not bind to the column, indicating that IscS binds to the column only through an interaction with IscU-His6 (data not shown).

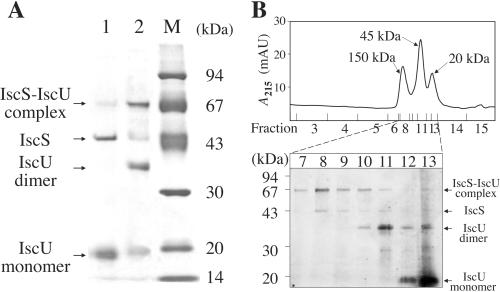

We next overproduced both IscS and IscU-His6 in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS harboring pFH6 to obtain a large amount of the IscS/IscU complex for biochemical analyses. IscS was copurified with IscU-His6 by nickel-column chromatography as judged by SDS/PAGE (Fig. 1A, lane 1). We carried out SDS/PAGE analysis for the same sample under nonreducing conditions to examine whether the sample included proteins bound to each other with a disulfide bond (or polysulfide bond) (Fig. 1A, lane 2). The fraction was found to contain 64- and 38-kDa proteins, in addition to 45- and 19-kDa proteins corresponding to monomeric IscS and IscU, respectively. N-terminal sequence analyses revealed that the 64-kDa protein is a covalently associated IscS/IscU heterodimer and the 38-kDa protein is an IscU homodimer with subunits covalently bound to each other.

Figure 1.

Covalent complex formation between IscS and IscU and between two IscU subunits. (A) An IscU-containing fraction from a His⋅bind column was treated (lane 1) or not treated (lane 2) with 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol and analyzed by SDS/PAGE. Lane “M” denotes marker proteins with sizes given in the right margin. Proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. (B) Gel filtration analysis of a copurified fraction containing IscU and IscS. (Upper) The elution profile of the fraction by using a Superose 12 column. (Lower) Nonreducing SDS/PAGE analysis of Superose 12 fractions. Proteins were visualized by silver staining.

The eluate from the nickel-chelating column was subjected to gel filtration to determine the subunit composition of the native proteins. Proteins were eluted as three resolved peaks corresponding to an α2β2 complex of IscS and IscU (about 150 kDa), dimeric IscU (about 45 kDa), and monomeric IscU (about 20 kDa) (Fig. 1B). We analyzed these proteins by SDS/PAGE under nonreducing conditions. The fractions of the α2β2 complex almost exclusively contained a covalently associated IscS/IscU heterodimer, and the amounts of monomeric IscS and IscU were negligibly small, indicating that the tetramer comprises two covalent IscS/IscU heterodimers. IscU appeared as a covalently linked dimer in the IscU dimer fractions.

To determine whether the covalent linkages between IscS and IscU and between the subunits of the IscU dimer were disulfide bonds or polysulfide bonds, S0 in the IscS/IscU complex and the IscU dimer was measured by cyanolysis. The amount of S0 in 1.5 mg of the copurified sample was determined to be 1.2 nmol. The copurified sample consisted of 42% IscU dimer, 38% IscS/IscU complex, 16% IscU monomer, and 4% IscS monomer based on quantification of the SDS/PAGE bands. Thus, the amount of S0 in the IscS/IscU complex is estimated to be at most 0.13 mol per mol of the IscS/IscU heterodimer assuming that all S0 was derived from the IscS/IscU complex [1.2 × 10−9/{1.5 × 10−3 × 0.38/(45,095 + 14,784)} = 0.13; the molecular weights of the subunits of IscS and IscU-His6 are 45,095 and 14,784, respectively]. The amount of S0 in the IscU dimer is estimated to be 0.056 mol per mol of the dimer at most. Accordingly, the vast majority of the IscS/IscU complexes and the IscU dimers have disulfide bonds, not polysulfide bonds, with S0 between two cysteine residues.

Formation of the Disulfide Bond Between Cys-63 of IscU and the Active-Site Cys-328 of IscS.

We next identified the residues constituting the disulfide bond between IscS and IscU. We also examined whether the disulfide bond is an absolute requirement for the interaction between IscS and IscU or whether other amino acid residues also mediate the specific interaction.

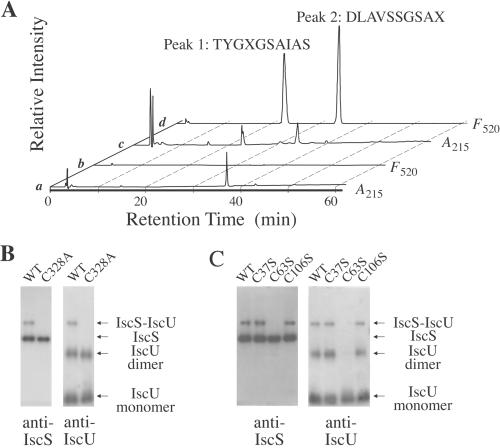

To identify the cysteine residues forming the disulfide linkage between IscS and IscU, the IscS/IscU complex was first treated with iodoacetic acid to alkylate free sulfhydryl groups and next digested with lysyl endopeptidase. The peptides were separated and purified by RP-HPLC, and a peptide containing the disulfide bond was identified by labeling the relevant cysteine residues with ABD-F after reducing the disulfide bond with TBP to produce free sulfhydryl groups. As a result, a peptide eluted at 37.1 min was exclusively labeled. The treatment with TBP caused the cleavage of the peptide into two peptides, which were eluted at 22.5 min (Fig. 2A, c and d, Peak 1) and 33.8 min (Fig. 2A, c and d, Peak 2). Both of them showed fluorescence derived from ABD-F (Fig. 2A, d). These peptides were not obtained without treatment with TBP (Fig. 2A, a and b). The N-terminal amino acid sequences of Peaks 1 and 2 were determined to be TYGXGSAIAS and DLAVSSGSAX, respectively. The former sequence corresponds to Thr-60-Ser-69 in IscU, and the latter corresponds to Asp-319-Cys-328 in IscS. The “X” in the amino acid sequences denotes the cysteine residue that was modified with ABD-F and therefore not identified with an automated protein sequencer. These results indicate that a disulfide bond is formed between Cys-63 of IscU and Cys-328 of IscS, which is the active site residue producing a persulfide intermediate in the reaction with l-cysteine.

Figure 2.

Determination of cysteine residues participating in the disulfide bond formation. (A) Peptide eluted at 37.1 min was treated with ABD-F in the absence (a and b) or presence (c and d) of TBP and analyzed by C18 column chromatography. Peptides were monitored by UV absorption at 215 nm (a and c) or by fluorescence at 520 nm (b and d). Effect of mutation(s) in IscS (B) or IscU (C) on the interaction and the covalent bond formation between IscS and IscU. Interactions were examined by copurification experiments with a nickel-chelating column as described in Experimental Procedures. Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE without the use of 2-mercaptoethanol and detected by Western blot analysis with anti-IscS or anti-IscU antiserum.

We next examined whether the disulfide bond between Cys-63 of IscU and Cys-328 of IscS is an absolute requirement for the association of IscU with IscS or whether other amino acid residues mediate the specific interaction between IscS and IscU. With this aim, we replaced Cys-328 of IscS with alanine by site-directed mutagenesis. We examined whether IscS-C328A interacts with IscU-His6 by copurification experiments with a nickel-chelating column. As shown in Fig. 2B, the C328A mutant of IscS was copurified with IscU-His6: IscS-C328A was identified in the eluate by Western-blot analysis with an anti-IscS Ab. Thus, Cys-328 of IscS is not an absolute requirement for the specific interaction between IscS and IscU. As expected, the 64-kDa band corresponding to the covalent IscS/IscU complex was not observed by SDS/PAGE for IscS-C328A because of the lack of the disulfide bond between IscS-C328A and IscU-His6.

We also constructed His6-tagged versions of IscU-C37S, IscU-C63S, and IscU-C106S and analyzed whether these mutant proteins were able to associate with IscS. As shown in Fig. 2C, IscS was copurified with every IscU mutant, as judged by Western blot analysis of the eluates with the anti-IscS Ab. Thus, none of the three cysteine residues of IscU is absolutely required for the specific interaction between IscS and IscU. However, as expected, Cys-63 is essential for the formation of the covalent complex of IscS and IscU: the 64-kDa band corresponding to the covalent complex was not observed when IscU-C63S was used for the copurification experiment. Cys-37 and Cys-106 of IscU were not required for the formation of the covalent complex. It is noteworthy that Cys-63 is also essential for the formation of the covalent IscU dimer: Western blot analysis of the eluate for IscU-C63S with the anti-IscU Ab showed the absence of the 38-kDa band, which corresponds to the IscU dimer.

Taken together, these results demonstrated that the disulfide bond was specifically formed between Cys-328 of IscS and Cys-63 of IscU and that the specific interaction between IscS and IscU was achieved by amino acid residues other than these cysteine residues through noncovalent interactions.

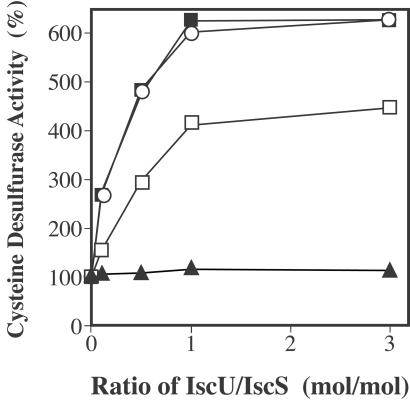

Activation of Cysteine Desulfurase Activity of IscS by IscU.

We found that IscU enhances the cysteine desulfurase activity of IscS and this activation requires the action of Cys-63 of IscU (Fig. 3). This was a novel observation with respect to IscS activation. We observed a maximum of a 6-fold increase in the activity with stoichiometric amounts of IscU-His6 (0.2 mM). The addition of excess IscU-His6 (3 times the IscS concentration) did not result in any further stimulation. The IscU-C37S and IscU-C106S mutants promoted 4.5- and 6-fold increases in the IscS activity, when added in stoichiometric amounts. In contrast, IscU-C63S did not stimulate the activity of IscS at all, indicating that Cys-63 of IscU, the residue forming the disulfide bond with the active-site residue of IscS, is essential for the activation of IscS.

Figure 3.

Activation of cysteine desulfurase activity of IscS by IscU. Cysteine desulfurase activity was measured in the presence of various amounts of IscU-His6 (○), IscU-C37S (□), IscU-C63S (▴), and IscU-C106S (■). The reaction mixture contained 20 mM l-cysteine, 50 mM DTT, 20 μM pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, 125 mM Tricine-NaOH (pH 8.0), 0.2 μM IscS, and wild-type or mutant IscU.

Discussion

In the present study, we have shown that IscS and IscU specifically interact with each other to produce a 1:1 complex and that Cys-328 of IscS and Cys-63 of IscU form a disulfide bond in the complex. Formation of the disulfide bond is supposed to be facilitated by noncovalent interactions between amino acid residues other than these cysteine residues, considering that the specific interaction between IscS and IscU is achieved even in the absence of these cysteine residues (Fig. 2 B and C). Specific interaction between IscS and IscU was also shown by the following observation. Although E. coli has two more enzymes with cysteine desulfurase activity, CSD (18) and CsdB (19), only IscS was shown to interact with IscU by surface plasmon resonance analysis (data not shown).

The covalent complex of IscS and IscU is produced only in the presence of l-cysteine, the substrate for IscS, implying that the target of IscU is IscS with sulfane sulfur derived from l-cysteine on its active-site Cys-328 (12, 14, 15). Because a disulfide bond was found between Cys-328 of IscS and Cys-63 of IscU, it is most likely that the Sγ atom of Cys-63 of IscU attacks the Sγ atom of Cys-328 carrying the sulfane sulfur derived from l-cysteine. It is also conceivable that the attack is crucial for the IscU-mediated activation of IscS, taking account of the indispensability of Cys-63 for the activation (Fig. 3); the attack by Cys-63 probably facilitates the release of the sulfane sulfur from Cys-328 of IscS. To increase the turnover rate of the IscS-catalyzed cysteine desulfurase reaction, IscU must be dissociated from IscS immediately after its attack on Cys-328 to make this residue competent again for the next cycle of catalysis. Dissociation of IscU from Cys-328 of IscS is probably facilitated by DTT in our assay system.

It will be interesting to examine what molecules are responsible for the dissociation of IscU from IscS in vivo. Glutathione may be involved in reduction of the disulfide bond. An hsp70-type molecular chaperone Hsc66 and a cochaperone Hsc20 encoded by the isc operon have been shown to interact with IscU (14, 20, 21). Thus, in addition to molecules required for reduction of the disulfide bond between IscS and IscU, these molecular chaperones may be involved in the dissociation process. That a significant amount of the covalent IscS/IscU complex was obtained in our copurification experiments may reflect the in vivo situation that the molecules required for the dissociation of IscU from IscS were not sufficient compared with overproduced IscS and IscU.

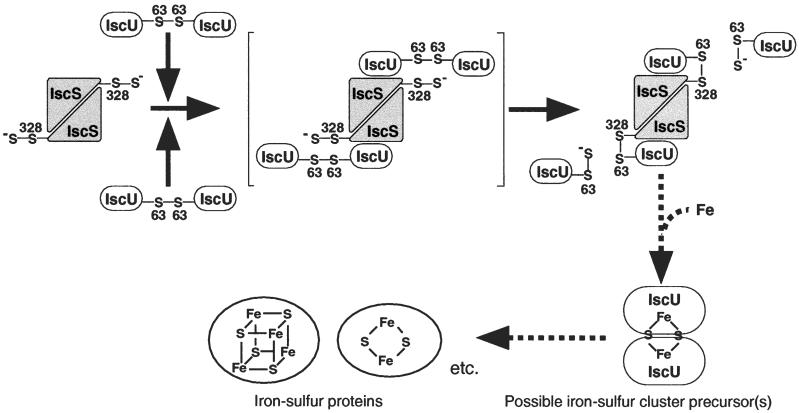

Based on the findings in the present study, we would like to propose a mechanism for the sulfur transfer from IscS to IscU. Previous reports have suggested that the sulfur atom derived from l-cysteine is transferred from IscS to IscU and covalently bound to IscU (14, 15). We show here that IscU exists in two forms, a monomeric form and a covalent dimeric form (Fig. 1B), and either of these two forms of IscU is supposed to receive the sulfur atom. If the monomeric form of IscU reacts with IscS, the sulfane sulfur is probably transferred to a cysteine residue located in the vicinity of Cys-63; the Sγ atom of Cys-328 of IscS is attacked by Cys-63 of IscU, and the sulfane sulfur released from Cys-328 is most likely accepted by a nearby residue. If the dimeric form of IscU is the molecule that attacks IscS, Cys-63 of IscU is supposed to be the primary site for sulfur transfer from IscS to IscU (Fig. 4). In this scheme, the disulfide-bridged IscU dimer reacts with persulfide-containing IscS, resulting in the formation of a disulfide linkage between Cys-328 of IscS and Cys-63 of one of the two subunits of the IscU dimer, releasing the other subunit of IscU with persulfide on Cys-63. Because IscS is a dimeric protein, there are two binding sites for IscU in each IscS dimer. On the basis of the x-ray crystallographic data for two IscS homologs, CsdB from E. coli (22) and an NifS-like protein from Thermotoga maritima (23), two subunits of IscS are probably associated with each other so that the two Cys-328 residues are located on opposite sides of the dimer (Fig. 4). If this is the case, two IscU dimers must react with one IscS dimer to produce the α2β2 heterotetramer of the IscS/IscU complex because two Cys-63 residues in one IscU dimer are not able to attack two Cys-328 residues of the IscS dimer simultaneously. Thus, two IscU monomers are released concomitantly with the formation of one heterodimeric complex of IscS and IscU.

Figure 4.

Proposed scheme for the formation of the covalent IscS/IscU complex involving the sulfur transfer from Cys-328 of IscS to Cys-63 of IscU. The bracketed α2β4 hexamer of the IscS/IscU complex is supposed to be produced transiently in the reaction. Details of the processes indicated by dotted arrows are not known. The type of iron-sulfur clusters on IscU serving as iron-sulfur cluster precursor(s) has not been determined.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (B) 13125203 (to N.E.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 13480192 (to N.E.), and by Grants-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Scientists 12780470 (to T.K.) and 13760069 (to H.M.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Abbreviations

- ABD-F

4-fluoro-7-sulfamoylbenzofurazan

- TBP

tributylphosphine

References

- 1.Beinert H. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2000;5:2–15. doi: 10.1007/s007750050002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beinert H, Kiley P J. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1999;3:152–157. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(99)80027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi Y, Nakamura M. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1999;126:917–926. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng L, Cash V L, Flint D H, Dean D R. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13264–13272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skovran E, Downs D M. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3896–3903. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.14.3896-3903.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tokumoto U, Takahashi Y. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2001;130:63–71. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz C J, Djaman O, Imlay J A, Kiley P J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9009–9014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160261497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kispal G, Csere P, Prohl C, Lill R. EMBO J. 1999;18:3981–3989. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Kogan M, Knight S A, Pain D, Dancis A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33025–33034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.33025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mihara H, Kurihara T, Yoshimura T, Esaki N. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2000;127:559–567. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng L, White R H, Cash V L, Dean D R. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4714–4720. doi: 10.1021/bi00181a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agar J N, Zheng L, Cash V L, Dean D R, Johnson M K. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:2136–2137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agar J N, Krebs C, Frazzon J, Huynh B H, Dean D R, Johnson M K. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7856–7862. doi: 10.1021/bi000931n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urbina H D, Silberg J J, Hoff K G, Vickery L E. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44521–44526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith A D, Agar J N, Johnson K A, Frazzon J, Amster I J, Dean D R, Johnson M K. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11103–11104. doi: 10.1021/ja016757n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohara Y, Akiyama K, Isono K. Cell. 1987;50:495–508. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood J L. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihara H, Kurihara T, Yoshimura T, Soda K, Esaki N. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22417–22424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mihara H, Maeda M, Fujii T, Kurihara T, Hata Y, Esaki N. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14768–14772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoff K G, Silberg J J, Vickery L E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7790–7795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130201997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silberg J J, Hoff K G, Tapley T L, Vickery L E. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1696–1700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujii T, Maeda M, Mihara H, Kurihara T, Esaki N, Hata Y. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1263–1273. doi: 10.1021/bi991732a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaiser J T, Clausen T, Bourenkow G P, Bartunik H D, Steinbacher S, Huber R. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:451–464. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]