ABSTRACT

Arf and Rab family small GTPases and their regulators, GTPase‐activating proteins (GAPs) and guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), play a central role in membrane trafficking. In this study, we focused on a recently reported GAP for Arf (and potentially Rab) proteins, the CSW complex, a part of a small family of longin domain‐containing proteins that form complexes with GAP activity. This family also includes folliculin and GATOR1, which are GAPs for the Rag/Gtr GTPases. All three complexes are associated with lysosomes and play a role in nutrient signaling, the latter two being directly involved in the mTOR pathway. The role of CSW is not clear, but in addition to having GAP activity on Arf proteins in vitro, its mutation causes severe neurodegenerative diseases. Here we update the reported pan‐eukaryotic presence of folliculin and GATOR1, and demonstrate that CSW is also found throughout eukaryotes, though with sporadic distribution. We identify highly conserved motifs in all CSW subunits, some shared with the catalytic subunits of folliculin and GATOR1, that provide new potential avenues for experimental exploration. Remarkably, one such conserved sequence, the “GP” motif, is also found in structurally related longin proteins present in the archaeal ancestor of eukaryotes.

Keywords: Arf GTPases, DENN domain, GTPase‐activating proteins, LECA, molecular phylogenetics, nutrient signaling, pan‐eukaryotic homology search, structural modeling

The three longin domain‐containing GAP complexes ‐ CSW, folliculin, and GATOR1 ‐ have a sporadic but pan‐eukaryotic distribution and were likely already present in LECA in some form. Their catalytic longin domains contain highly conserved sequence motifs, some of which are shared with structurally similar proteins of Asgardarchaeota.

1. Introduction

The small GTPases are a large superfamily of highly conserved proteins that form the functional backbone of regulatory and signaling pathways involved in many cellular processes. Their function is dependent on guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase‐activating proteins (GAPs). GEFs are responsible for the exchange of bound GDP for GTP, converting the GTPase into its active form, while GAPs catalyze GTP hydrolysis. For the Arf and Rab GTPases, the best‐studied catalytic regions of GEFs are the Sec7 domain for the Arf family [1, 2] and the DENN/longin domain for Rab family proteins [3, 4, 5, 6]. For Arf proteins, two well‐established GAP families have been studied, those containing a Zn finger GAP domain [7, 8] and those with an ELMO domain [9]. For Rab proteins, the TBC domain is the most widespread GAP domain [10, 11]. Unlike the GTPases themselves, generally highly conserved, short, single domain proteins, their GEFs and GAPs usually contain multiple domains in addition to the catalytic domain (e.g., PH, SH3, C2, coiled‐coil, BAR, ankyrin‐repeat, WD40 or RUN [4, 10, 12]) and are much more varied in their size and architecture.

Arf and Rab GTPases, along with their specific GEFs and GAPs, play a central role in membrane trafficking [1, 13, 14]. An essential function of Arf proteins is in the formation of transport vesicles, while Rab proteins mediate vesicle navigation to the target membrane and fusion with it [1, 13, 14]. Arf and Rab GTPases carry out their functions by recruiting specific proteins to membranes in their active GTP‐bound conformation. For example, Arf proteins recruit vesicle coat complexes to membranes to mediate vesicle budding, and Rab proteins recruit vesicle tethering complexes as an early step in vesicle fusion [1, 13]. In addition to vesicular trafficking between organelles, Arf and Rab family proteins also regulate other endomembrane functions, such as organelle‐cytoskeleton interactions, organelle movement, and membrane lipid composition [2, 13, 15, 16, 17]. This fundamental and complex cellular organization is the staple of eukaryotic cells, as opposed to that in prokaryotes, which do not have extensive internal membrane structures. The closest known prokaryotic relatives of eukaryotes, the Asgard archaea (Asgardarchaeota), have a number of homologs of membrane trafficking proteins previously considered eukaryote‐specific [18, 19]. The first cultured Asgardarchaeota organisms were shown to have a simple cell morphology with no observable internal compartmentalization [20, 21]. However, the recent first report of cultivated heimdallarchaeial cells describes infrequently observed internal membrane structures, whose size and frequency increase with higher nutrient concentration [22].

The Arf family, which includes not only Arf, Arf‐like, and Sar GTPases in eukaryotes [15], but also the Arf‐related proteins (ArfRs) present in the Asgard archaea, is ancient, having arisen before the divergence of eukaryotes from their archaeal ancestor [23, 24]. Given their wide spectrum and high specificity of their interactions, the expansion of the Arf family, and their GEFs and GAPs, likely played a crucial role in the evolution of the endomembrane system, especially the emergence and specialization of its parts [8, 25, 26, 27]. All of the above GTPases, GAPs, and GEFs have been shown to be widely distributed, and in fact expanded to multiple paralogues, across eukaryotes, from animals to fungi, plants, algae, and parasites [15]. Studying these proteins and their domains and enzymatic functions in a broader, pan‐eukaryotic context is a prerequisite to better understanding of the biology of diverse eukaryotes and early eukaryotic evolution.

One set of potential Arf regulators, however, has not yet been examined systematically using this comparative evolutionary lens. The C9orf72:SMCR8:WDR41 or CSW complex, comprising three subunits, C9orf72, SMCR8, and WDR41, was first described in humans, where mutations in one of its subunits (noncoding region expansions in C9orf72) cause severe neurodegenerative diseases (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS, and frontotemporal dementia, FTD; [28, 29, 30]). It has been identified as a multisubunit GAP and experimentally shown in vitro to act most efficiently upon Arf1, Arf5, and Arf6, and to have some, albeit much weaker, activity toward Rab8 and Rab11 [31, 32, 33]. It is considered a member of a small family of longin domain‐containing GAP complexes, all of which localize to the lysosomal membrane and play a role in nutrient sensing [31, 32, 34]. The other two members of this family are the folliculin (FLCN:FNIP) and GATOR1 (NPRL2:NPRL3) complexes that act upon Rag GTPases and work in tandem as a part of the mTOR signaling cascade, a major control hub of cell growth [31, 35, 36, 37, 38]. The CSW complex is recruited to the lysosomal membrane via interaction between its subunit WDR41, which contains a beta‐propeller domain, and the PQ loop‐containing cationic amino acid transporter PQLC2 [35, 39, 40]. This binding is inhibited when the transporter substrate (arginine, histidine, and lysine) is abundant, suggesting that the CSW complex might mediate some kind of cross‐talk between Golgi‐ or endosome‐derived membranes and lysosomes under cationic amino acid starvation. The exact function, however, is currently not understood.

The catalytic pocket of the CSW complex is formed by two symmetrically arranged longin domains of different subunits (C9orf72 and SMCR8) with known essential residues of both required for GAP activity (specifically W33‐D34 in C9orf72, and R147, the catalytic arginine, referred to as an arginine finger, in SMCR8 [32]). In folliculin and GATOR1, the subunits containing the catalytic arginine are FLCN and NPRL2, respectively, present within their longin domains, with the FNIP2 and NPRL3 subunits also containing longin domains [31]. The evolutionary relationship and degree of sequence homology between these six proteins are yet to be established and examined in detail. However, previous studies group them together based on their domain architecture and secondary structure and consider them related to or a part of the DENN family [5, 31, 34]. Previous studies [34, 41] found evidence for SMCR8/FLCN‐type longin proteins and/or FNIP in Capsaspora, some fungi, amoebozoa, metamonads, and discobids, and one or both GATOR1 subunits in the previously mentioned groups plus several apicomplexans and stramenopiles, and a few more homologs are currently annotated as such in the Uniprot database (https://www.uniprot.org/, [42]). By contrast, little information is available regarding the distribution and function of the CSW proteins outside mammals. Zhang et al. [34] identified a few nonmetazoan homologs using a limited sampling of genomic data available at the time, namely C9orf72 in some choanoflagellates and amoebozoans, Trichomonas, and Naegleria. It is likely that this unique family of GAPs occurs more widely and could potentially be traceable to the root of a large subsection of the eukaryotic tree of life spanning very diverse organisms, to the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA), or even further. An updated, comprehensive eukaryote‐wide screening may therefore reveal distribution patterns that could shed some light on the early evolution of the organization and crosstalk between lysosomes and other endomembrane compartments.

In this study, we took advantage of the rich supply of available sequence data for nonmodel eukaryotic groups, including previously obscure and recently discovered deep‐branching lineages, and performed a pan‐eukaryotic search for each of the subunits of the CSW complex, other longin GAPs, and their potential interaction partners to observe patterns in their distribution and co‐occurrence, and attempt to trace their point of origin and evolutionary history using phylogenetic methods. Structural modeling and primary sequence analysis confirmed the conservation of known functionally critical amino acid positions and identified additional highly conserved amino acid residues which likely have functional importance. Intriguingly, some of these residues are also shared with longin domain proteins encoded in asgardarchaeal metagenomes.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Longin GAP Complexes Have Wide but Patchy Distribution

We investigated the distribution of CSW, folliculin, and GATOR1 complex proteins across all major eukaryotic lineages using an enriched and modified TCS database of genomes and transcriptomes and sensitive sequence homology detection (see Section 4, Table S1). The resulting homolog datasets, including e‐values of the hits, taxonomical annotation, and other notes can be found in Tables S2–S8.

We report that subunits of the CSW complex, which have been studied in humans and annotated in various animals in the Uniprot database, are present in many other eukaryotic lineages. However, their distribution is patchy as it seems to be completely missing from a number of major lineages, especially among Diaphoretickes (i.e., Archaeplastida, Haptista, Telonemia, Stramenopila, Cilliophora, and Myzozoa; Figure 1) and as it is not universally conserved in lineages in which it has been identified. The distribution of the folliculin complex exhibits a similar pattern, with its depletion among Diaphoretickes being even more noticeable (present or partially present only in some Provora and Haptista). GATOR1, on the other hand, is at least partially retained in all lineages (with the only exception of Fonticulida which is, however, represented by a single, possibly incomplete, dataset). In the context of the currently accepted topology of the eukaryotic tree of life (outlined in figure 1, [43, 44, 45]), including the recently proposed position of its root [46], these findings suggest that some form of all three complexes was already present in LECA and that its patchy distribution is the result of multiple secondary losses. The scenario explaining this distribution pattern could be simplified by the recently proposed changes to the eukaryotic tree, which place Provora, Meteora, and Hemimastigophorea (i.e., some of the groups where CSW and/or folliculin is retained to some degree) as sister to Diaphoretickes instead of nested within them [47]. If genuine, this relationship would strongly suggest there was a single instance of loss of CSW and folliculin complexes in the common ancestor of Diaphoretickes and a few cases of secondary gain of some subunits via LGT in isolated lineages of this group (e.g., Colponemidia).

FIGURE 1.

The distribution of the three longin GAP complexes across major eukaryotic lineages. From the center outward, CSW: C9orf72 (magenta), SMCR8 (purple), and WDR41 (blue), any PQ‐loop protein homologous to PQLC2 (i.e., potential interaction partners of CSW; sky blue), folliculin: FLCN (teal) and FNIP2 (cold green); GATOR1: NRPL2 (warm green) and NPRL3 (chartreuse). Darker hue of the respective color indicates the protein is present in majority of the investigated datasets, paler hue indicates it is present sporadically, while white denotes no reliable evidence of its presence. The tree topology is conservatively synthesized from the recent pan‐eukaryotic phylogenies [43, 44, 45], the possible position of the root is along the branches denoted by dashed lines. The asterisks denote evolutionarily significant but poorly sampled lineages that were represented by a single genome or transcriptome in our database.

Little is known about the function of these complexes outside model organisms and, in the case of CSW, even the function in humans remains unclear. The common denominator, however, seems to be a role in nutrient signaling [31]. Trophic strategy may therefore represent a contributing factor to the evolutionary pressures that led to the loss or retention of these proteins in different lineages. While not universally conserved, GATOR1 proteins seem to occur at a relatively similar rate in free‐living heterotrophs (178 of 250 possible orthologues in 125 taxa, 71%), parasitic/symbiotic heterotrophs (27 of 64 possible orthologues in 32 taxa, 42%), and phototrophs/mixotrophs (36 of 100 possible orthologues in 50 sampled taxa or 36%) (Figure 2, Table S1). This is not the case for CSW and folliculin complex proteins, whose presence is biased toward free‐living heterotrophs (41% and 33% of possible retained orthologues, respectively, compared to 2% and 9% retained in parasites/symbionts and 1% and 0% in phototrophs/mixotrophs). For example, while all three subunits are conserved in most free‐living Amoebozoa, the only parasitic representative in our sampling, Entamoeba histolytica , lacks all of them. Similarly, the same subunits are absent from phototrophic/mixotrophic organisms with the exception of an SMCR8 homolog in Euglena gracilis .

FIGURE 2.

Occurrence of the proteins of interest across eukaryotes broken down by trophic strategy. All organisms in our database were sorted into three categories: Phototrophic or mixotrophic (green), parasitic or symbiotic (orange), and free‐living heterotrophic (yellow) (Table S1). The composition of the database in regard to these categories is shown as the first column in both bar plots (as counts and percentages, respectively). The remaining columns shows their ratio in the subsets of organisms in which the respective protein has been identified. GATOR1 subunits and PQLC2/YPQ are more widespread and seem to be distributed equally across trophic categories. CSW and folliculin complex proteins, on the other hand, occur more sporadically and show a bias toward free‐living heterotrophic organisms.

Given their roles in amino acid sensing and signaling (demonstrated for folliculin and GATOR1 which are involved in the mTOR pathway, and presumed for CSW due to its interaction with cationic amino acid transporter PQLC2 and recruitment to lysosomes upon amino acid starvation [39]), this may reflect the difference in amino acid cost and availability under different evolutionary strategies. Photo‐ and mixotrophs generally synthesize most of their amino acids themselves. Parasites, on the other hand, often live in relative nutrient abundance and can therefore afford to streamline their energy metabolism at the cost of energetic efficiency or supplement it with alternative energy sources, including amino acids [48, 49]. Both of these situations may drive changes in amino acid signaling pathways, potentially resulting in fewer steps and proteins involved. At the same time, the possibility of some of these results being false negatives and caused by limited sampling or transcriptome incompleteness should not be dismissed (BUSCO scores of all datasets are given in Table S1). It should also be noted that the final dataset for WDR41 may be more affected by false negative results due to the stricter e‐value threshold used in homolog mining (see Section 4).

In conclusion, our analysis indicates that all three longin domain‐containing GAP complexes were already present in LECA, at least in some form. GATOR1 is the most widely distributed among eukaryotes, across taxonomic groups and trophic strategies, although some secondary losses have occurred. CSW and folliculin, on the other hand, appear to be somewhat confined to the nondiaphoretickes half of the eukaryotic tree of life, which includes animals, fungi, and amoebozoa, in addition to a number of protist groups. They are notably absent from plants and other phototrophs across eukaryotic diversity and more frequently found in free‐living heterotrophs than in parasites and symbionts. This pattern of conservation could shed light on their functions, given the role of all three complexes in nutrient sensing in mammalian cells.

We also searched for homologs of PQLC2 in order to investigate its co‐occurrence with the CSW complex. Our results show that they occur throughout eukaryotes, often in two or more divergent paralogues and in a patchy pattern. Our phylogenetic analyses suggest complex relationships between these homologs and an unclear history of duplications resulting in multiple differentially retained clades (Figures S1 and S2, Table S9, Data S1). These also include YPQ2 and YPQ3, vacuolar arginine/histidine transporters reported in yeast [50] which underlines the notion that the identified proteins likely have various localizations that cannot be discerned without experimental evidence. We were not able to identify a notable pattern of co‐occurrence between specific clade(s) and the CSW complex or WDR41 (i.e., the subunit interacting with PQLC2 in human). However, the possibility of interaction between the human CSW complex and other, heterologous PQLC2 homologs, such as the yeast YPQs, may be worth experimental investigation and may have broader implications for the CSW complex function and its evolution throughout eukaryotes. For instance, the existence of organisms possessing CSW but lacking any identifiable PQLC2 homolog (e.g., many of the sampled Amoebozoa, some CRuMs, Ancyromonadida, and Colponemidia; see Table S1) suggests their CSW complex is able to interact with an alternative partner, be it on lysosome or elsewhere, or that it performs its function exclusively in a soluble form. These results show that the receptor on membranes for CSW in humans is also widely distributed among eukaryotes, but is not always present in organisms that have CSW complex proteins, suggesting that other receptors might exist. Identification of such alternative membrane receptors could lead to new insights into the functions of the CSW complex.

2.2. The Inter‐Relationships Between CSW, Folliculin, and GATOR1 Proteins

The six longin proteins of CSW, folliculin, and GATOR1 complexes were previously reported as a distinct family of DENN domain‐containing proteins based on domain organization [34] and structural and functional similarity [31, 32]. In order to verify this notion and further investigate their relationships in a broader context, we mainly focused on the longin domains themselves and employed several parallel approaches (based on structure modeling, sequence alignment and similarity, and phylogenetics; see Section 4).

Our analyses clearly identified significant conservation of structure and/or sequence in particular regions of particular proteins (see Section 2.4). Although we were not able to consistently recover the proposed family as a clearly defined clade with resolved inner relationships, we identified several interesting homology relationships and cases of significant conservation of structure and/or sequence. All versus all BLAST results revealed sequence homology of SMCR8 and FLCN in the longin domain. Conversely, C9orf72 exhibits some homology to SMCR8 and FNIP2 outside the longin domain and weak similarity to NPRL2 in the longin domain. NPRL2 and NPRL3, on the other hand, robustly retrieve each other in all searches (Figure S3, Table S10). Interestingly, this is not corroborated by pairwise alignment‐based analysis of sequence identities and similarities of the full protein sequences (Table S11), further suggesting the homologous regions are scattered and full‐length alignment of different GAP longin proteins is problematic. Moreover, when analyzed based on predicted secondary structure, different patterns emerge (Figures S4 and S5). For instance, the abovementioned pairs of longin domains based on sequence similarity (NPRL2/NPRL3 and SMCR8/FLCN) do not exhibit prominent secondary structure similarity, and the GAP longin family as a whole seems less distinct from some other DENN proteins in our sampling. Our results indicate that among the members of the GAP longin family, specific protein regions have clear relationships between them but that complexity has been introduced, potentially by instances of gene fusions, evolutionary convergence, or simply artefacts stemming from paucity of phylogenetic signal.

2.3. Phylogenetic Signal of CSW Supports Its Presence in LECA and Vertical Inheritance

In order to better understand the evolutionary history of the individual complex subunits, we built single‐gene unrooted trees for each of the proteins of interest (Figures S6.1–7) and a tree based on a concatenated matrix of the three subunits of the CSW complex (Figure 3). While the single‐gene tree topologies have generally low support, major well‐sampled taxonomic groups, such as Metazoa, Fungi, Stramenopila, Percolozoa, etc., cluster in most cases. The concatenated tree for CSW subunits has low backbone support, but its overall topology is consistent with the expected relationships between the sampled taxonomic groups. Opisthokonts are recovered as a monophyletic group with resolved and well‐supported inner topology, and so are discobids. Amoebozoa form a well‐supported monophyletic cluster with Provora, represented by Ancoracysta twista and Nebulomonas marisrubri, nested inside (the attraction of these groups is also apparent in the single gene trees, Figures S6.1 and S6.3). This represents the only well‐supported phylogenetic relationship incongruent with pan‐eukaryotic topology and a likely case of lateral gene transfer (LGT) from Amoebozoa to Provora, possibly related to the phagotrophic predatory life strategy of the latter. We conclude this is unlikely to be the result of contamination, as the two provorans cluster together but form separate branches of regular length. This provides a new context for the notable absence of the folliculin complex in all diaphoretickes except Provora, begging the question of whether their folliculin could also be the result of LGT. It is also worth noting that Provora were recently proposed to be sister to other diaphoretickes [47]. Either of these scenarios could greatly reduce the number of secondary losses required to reconcile its observed distribution with its origin in LECA.

FIGURE 3.

Concatenated phylogeny of the three subunits of the CSW complex. The dark, light, and colorless circles denote bootstrap support of 100, 90–99, and 80–89, respectively, the branches without circles have lower support. The colors delineate main taxonomic groups: Holozoa (shades of red), Holomycota (shades of orange), Apusomonadida (gold), Amoebozoa (light green), CRuMs (green‐cyan), Percolozoa (dark cyan), Jakobida (sky blue), Malawimonada (blue), Provora (pink), and other Diaphoretickes (shades of purple, navy) (see Figure S7 for detailed color legend).

2.4. Eukaryote‐Wide Comparison Reveals Novel Motifs of Interest

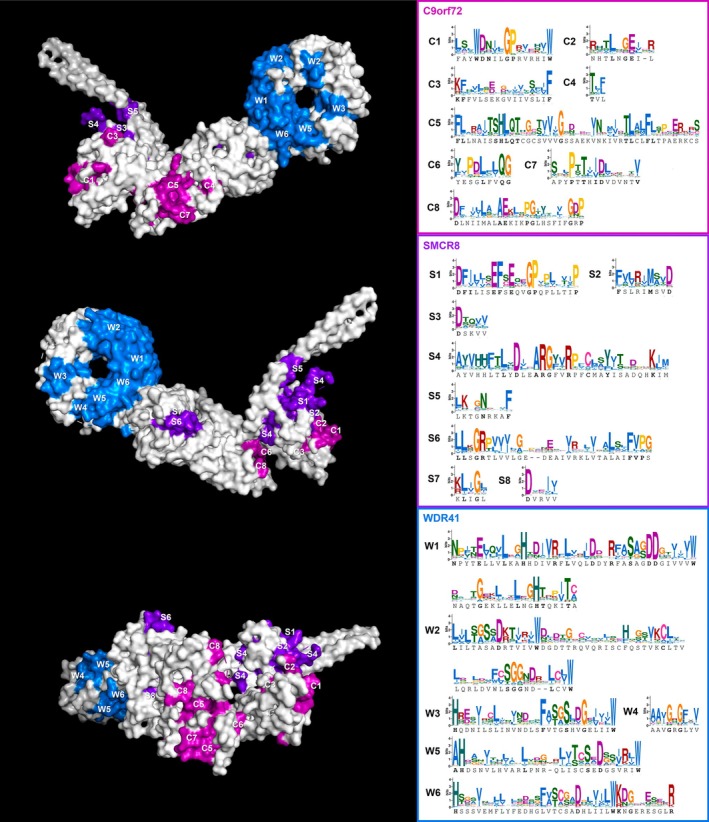

Thanks to the pan‐eukaryotic sampling of the CSW proteins, we were able to gain a broader perspective on the relative conservation of their structural and sequence motifs (Figure 4). The essential residues identified by previous studies in humans, namely the W33‐D34 of C9orf72 and the arginine finger (R147) of SMCR8, are almost universally conserved across other eukaryotes (C1 and S4 in Figure 4), suggesting the catalytic function is conserved despite the significant divergence in other parts of the protein chains. In addition, we identified a number of other widely conserved residues or motifs that were not previously reported or studied and that may represent potential targets of future experiments aiming to gain a deeper understanding of the role of the CSW complex in human cells as well as other organisms.

FIGURE 4.

Reference CSW complex structure with conserved regions highlighted. Conserved sequence motifs were manually selected from the pan‐eukaryotic alignments of the three subunits and are visualized as sequence logos on the right and shown mapped onto the human structure shown in three different orientations; the three subunits are distinguished by colors and letter IDs. Regions C1–C3 and S1–S5 are parts of the longin domains of their respective proteins, while C4–C8 and S6–S8 occurr downstream of it. The conserved regions of WDR41 shown are all equivalent to, or part of, the WD repeats with the exception of W4 which falls between the fourth and fifth repeat. The exact positions and other details are given in Table S13.

Sites of notable sequence conservation are not limited to the longin domain of C9orf72 and SMCR8, but also occur in the downstream part of the protein chain forming the middle section of the complex. The significance of these sites, for example whether some of them (e.g., the outward facing C5, C7, and S6 in Figure 4) could represent binding interfaces for additional molecules, remains to be determined by mutation experiments.

The most remarkable example is the GP motif in the catalytic longin domain that occurs in both C9orf72 and SMCR8 (G38‐P39 and G68‐P69 in the reference human sequences; C1 and S1 regions in Figure 4), as well as FLCN and NPRL2 but not in FNIP2, NPRL3, and other non‐GAP longin proteins such as adaptins, TRAPP complex subunits, or DENND family proteins. Structurally, it represents either the C‐terminal part of the loop immediately preceding the second beta sheet of the longin domain or the N‐terminal part of this beta sheet. As such, it clearly occupies a central position in the catalytic pocket and spatially neighbors the arginine finger, an essential motif present and universally conserved not only on SMCR8 but also FLCN and NRPL3 (Figure 5A–C). The GP motif of C9orf72 is positioned symmetrically to the one in SMCR8 and is closely adjacent to the abovementioned essential and highly conserved WD motif. This analysis, based on structural predictions, strongly supports the notion that the GP motif plays an important role in the function of all three complexes and, given its specific presence in this family and absence from other longins, may be at least partially responsible for them carrying out GAP activity instead of GEF activity, which is more typical of longin proteins. Together, these analyses make this novel motif an attractive prospective target for future experiments, for example, to test the effect of its mutation on enzyme kinetics and specificity.

FIGURE 5.

Conservation of the GP motif and arginine finger of the eukaryotic longin domain‐containing GAP complexes and structurally similar Asgardarchaeota longins. Detail of the catalytic pocket of human folliculin (A), GATOR1 (B), and CSW (C) complexes, including their interaction partners (RagC, RagB, and Arf1, respectively) and bound GDP, with arginine fingers, GP motifs, and WD motif of C9orf72 highlighted. Sequence logos for the GP motif‐containing regions denoted by lighter color shade (first and second beta sheets of the longin domain and the loop between them) based on our pan‐eukaryotic sampling are shown underneath. A reference heimdallarchaeial FLCN/SMCR8‐type longin domain‐containing protein and a logo based on 14 other structurally related Asgard longins with previously published predicted structures are shown in (D), underscoring their remarkable similarity to the eukaryotic longins with GAP activity. The subunit color coding is as per Figure 1 (FLCN: teal, FNIP2: cold green, NRPL2: warm green, NPRL3: chartreuse, C9orf72: magenta, SMCR8: purple) with additional colors for the client GTPases (RagB: wheat, RagC: orange, Arf1: yellow) and Asgard longin protein (red).

2.5. Secondary Structure of CSW Complexes From Diverse Eukaryotes

A number of studies have provided extensive structural information for the GATOR1 and folliculin complexes, including comparative structural analyses of yeast and human complexes [31, 35, 36, 37], but no comparative structural analyses have been reported for CSW. As a first step to obtaining information about the structures of the CSW complex across eukaryotes, we selected a small subset of taxonomically representative organisms with all three subunits identified, modeled their secondary structures using AlphaFold (Figures S8–S10), and aligned them to human reference (Figure 6) and to each other (Table S12). This sampling included Capsaspora owczarzaki, a protist lineage closely related to animals, Parvularia atlantis, a nucleariid amoeba closely related to fungi, Acanthamoeba castellanii , an amoebozoan, Diphylleia rotans, a deep‐branching flagellate distantly related to Amoebozoa and Opisthokonta, Meteora sporadica, a deep lineage of Diaphoretickes, and Colponemidia sp. Colp10, an alveolate. In this dataset, WDR41 and C9orf72 seem to be structurally conserved across the different organisms (TM‐scores generally between 0.8 and 0.9), but significant divergence is observed in the case of SMCR8 where the best alignments do not exceed a TM‐score of 0.8 while the lowest‐scoring ones fall below 0.5 (Table S12). This is congruent with the fact that these models by themselves are of lower overall confidence, usually exhibiting low PAE scores outside the longin domain (Figure S9). The structure of SMCR8 of Capsaspora, Parvularia, Acanthamoeba, and Diphylleia seems to be well‐conserved around the catalytic site but diverges, to various degrees, in the second and third alpha helices of the longin domain and further downstream. In Meteora and Colp10, the two representatives of Diaphoretickes in our sample, the structure of SMCR8 may be even more disrupted, even in the catalytic longin domain, which brings up the question of whether this subunit can function in a complex with C9orf72 and carry out the same function as its counterparts in other lineages. A functionally divergent SMCR8 is plausible, considering that the CSW complex is not present in the vast majority of Diaphoretickes, possibly due to secondary loss following a divergence in or loss of function in their common ancestor. Such a proposition would, however, require more detailed analysis, including in vitro experiments, for example, to test whether the divergent subunits form a complex and to determine their cellular localization.

FIGURE 6.

CSW complex secondary structure comparison between diverse eukaryotes. Structures modeled by AlphaFold (in color) are aligned to cryo‐EM‐based reference structure of the human CSW complex (white). SMCR8 subunit of Colponemidia sp. Colp10 is not shown due to its high divergence and misalignment. WDR41 subunit and the longin domains of the catalytic subunits exhibit higher structure conservation, especially across the nondiaphoretickes (Capsaspora, Parvularia, Acanthamoeba, and Diphylleia) homologs, while the middle section of the complex is more divergent or possibly completely disrupted in some cases (i.e., SMCR8 of Meteora and Colp10).

Nevertheless, our results indicate that the secondary structures of the longin domains of C9orf72 and SMCR8, which form the catalytic pocket, and the WDR41 subunit, which mediates interaction with lysosome, are relatively highly conserved across diverse nondiaphoretickes, which suggests retention of the GAP and lysosome‐interacting function of their CSW complex.

2.6. Conserved Sequence Motifs Connect Eukaryotic GAP Longins to a Specific Class of Asgard Longins

The conservation of the GP motif and arginine finger in components of all three of the eukaryotic complexes prompted us to look for deeper evolutionary origins of the GAP catalytic subunits. Asgard archaea are known to encode expanded complements of longin proteins [26, 51], and indeed there are sequences and predicted structures previously deposited in the Uniprot and AlphaFold databases that exhibit high structural similarity to GAP longins, in some cases explicitly annotated as “Folliculin/SMCR8 longin domain‐containing” (Figure 5D; protein sequences published in [19, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56] can be found in Data S1). Strikingly, the GP motif and arginine finger in the same structural arrangement are also present in these longins. This conservation and their notable presence in Heimdallarchaeia, the proposed closest Asgard relatives of eukaryotes [18, 57], further support their annotation as homologous and specifically related to the eukaryotic GAP longins. It also raises the possibility that these Asgard longin domains and the eukaryotic GAP longins share a common ancestor, and that they may potentially share GAP activity. CSW and folliculin/GATOR1 act as GAPs for Arf and Rag proteins, respectively, and Asgard archaea have previously been demonstrated to possess both Arf‐related (ArfR) [23] and Rag/Gtr GTPases [23, 26, 58] which begs the question of whether either, or possibly both of these families could represent interaction partners of the GP motif‐containing Asgard longins. Furthermore, if these longins are indeed evolutionarily related and could carry out similar enzymatic function, the fact that the eukaryotic members of this hypothetical family are all specifically associated with lysosomes could be of great significance in regard to the possible origin and ancestral forms of the eukaryotic endomembrane system, some traits of which are already present in Asgards, and particularly, Heimdallarchaeia [20, 22, 58, 59].

3. Conclusion

We searched for homologs of the subunits of the longin domain‐containing GAP complexes with an updated database containing genomes and transcriptomes of representatives spanning most currently known lineages of eukaryotes. We report that homologs of the GATOR1 proteins are present in some representatives of all groups, suggesting that the complex was already present in LECA. This result is congruent with the universal presence of the TOR signaling pathway in eukaryotes [60, 61]. On the other hand, we only find evidence of the folliculin and CSW complexes in roughly half of the examined lineages and note that both seem to be absent in the vast majority of diaphoretickes. This distribution is even more prominent in the case of folliculin. Moreover, both complexes exhibit patchy distribution favoring free‐living heterotrophic organisms as opposed to phototrophs/mixotrophs and parasites/symbionts, likely reflecting the very different dynamics of nutrient availability under different lifestyles. Nevertheless, considering the currently accepted pan‐eukaryotic tree topology, including the recently proposed position of its root within “excavates,” some form of all three complexes was also likely present in LECA but later lost in multiple lineages. The disparity in the occurrence of GATOR1 and folliculin is unexpected, given their complementary function in the mTOR signaling pathway in humans, but could relate to GATOR1's interaction with other partners that may not be conserved throughout eukaryotes [41].

The longin GAP complexes were previously proposed to be related to one another and to form a small protein family [31, 32, 34] and our results regarding their secondary structures and conserved sequence motifs confirm this classification. Longin domains have historically been difficult to phylogenetically resolve [12] and our results are no exception. We suspect that this is partially due to the long time since the divergence of the protein families and the diverse roles that longin‐domain containing proteins play in the cell, but also that their evolution could be underpinned by multiple cases of domain rearrangement or fusion and evolutionary convergence, which are difficult to trace. These factors make it challenging to reconstruct all of the details of their exact phylogenetic relationships. This work has also raised potential new research avenues to understanding the mechanism of the longin GAP complexes. We report a new, highly conserved GP motif present in the catalytic site of SMCR8, C9orf72, FLCN, and NPRL2, that is, specific to the longin domains with GAP activity. We predict that the GP motif might be essential for GAP activity given its conserved position close to the catalytic arginine. Moreover, we identified this motif in a class of structurally similar longins previously reported in Heimdallarchaeia, the proposed closest relatives of eukaryotes. Further studies of this and the other signature motifs we identified should provide new insight into the functions of the longin GAP complexes, not only as cellular components playing their role in their respective organisms but also as evolutionary entities whose relationships and histories may have broader implications for eukaryotic evolution.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Homolog Mining

As the base of all pan‐eukaryotic homology searches reported in this study, we used the TCS database, a curated subset of Eukprot [62], comprising 196 genomes and transcriptomes, supplemented by several recently published genomes for some of the undersampled lineages: Mantamonas spyranae and Mantamonas vickermanii (CRuMs) [63], Proteromonas lacerate (Opalinea) [64], Diplonema papillatum (Diplonemida) [65], N. marisrubri, Nibbleromonas quarantinus, Nibbleromonas curacaus, and Ubysseya fretuma (Nebulida) [66], and M. sporadica (deep lineage related to Hemimastigophorea) [44]; the resulting database consists of 207 genomes and transcriptomes and will be hereafter referred to as TCS+.

Homologs of C9orf72, SMCR8, WDR41, PQLC2, FLCN, FNIP, NPRL2, and NPRL3 were searched in TCS+ using HMMer. The HMM profiles for all genes were prepared by gradual addition of more divergent homologs to the initial seed datasets of human references and other reviewed sequences from Uniprot. This included BLAST searches against non‐mammal metazoan datasets in Genbank, and subsequent HMMer searches against datasets for Holozoa and Amorphea. In the case of C9orf72 and SMCR8, this initial search was also performed based on partial profiles for three DENN subdomains (the first of which, termed uDENN, corresponds to the longin domain), as annotated in the reference human sequences, to increase sensitivity. All TCS+ HMMer hits with e‐value < 0.01 for C9orf72, SMCR8, WDR41, and PQLC2 were considered preliminary candidates while only the best hits were considered for FLCN, FNIP, NPRL2, and NPRL3. Reverse BLAST searches against the human reference genome were then performed for all preliminary datasets, and only sequences that returned their respective reference gene among the top three hits were included in the final candidate datasets. The e‐value threshold of these searches was set to 1e−20 for WDR41 and 1e−5 for the rest as the latter value proved too loose for a satisfactory distinction between WDR41 and other WD repeat proteins. All candidates with detailed annotations, including the ones that did not pass the reverse BLAST check or those later discarded, as well as the final high‐confidence candidate datasets are available in Tables S2–S9 and Data S1.

4.2. Phylogenetic Analyses

To further validate these datasets and identify and remove redundant sequences, suspect contaminations, and low‐quality sequences, preliminary phylogenetic trees (not shown) were constructed and manually inspected. The datasets for individual proteins of interest were investigated one by one but also in several combinations in order to verify the distinction between related sequences (e.g., C9orf72 vs. FLCN). Alignments were constructed by MAFFT (v7.487 July 25, 2021; [67]) and trimmed by TrimAl (v1.4.rev15 December 17, 2013; [68]), and maximum likelihood trees were built by IQ‐TREE2 (v2.1.3 August 24, 2021; [69]) with automatic model selection and 1000 ultrafast bootstraps. Sequences that were removed during this analysis are annotated as such in Tables S2–S9.

Unrooted single‐gene trees were subsequently built for each of the proteins of interest to assess the inner relationships of the identified homologs. An additional rooted tree was constructed for the PQLC2 dataset with PQLC1 as an outgroup to confirm the correctness of their distinction. The sequences were aligned by MAFFT and trimmed by BMGE (v2.0; [70]), and trees were built by IQ‐TREE2 with LG + C20 + G4 matrix and 1000 ultrafast bootstraps. A concatenated phylogenetic matrix of the three CSW complex subunits was also prepared from a subset of homologs selected based on the presence of at least two subunits in the given organism, absence of divergent paralogues, and sequence completeness (annotated in Tables S2–S4) and analyzed using the same method with C60 matrix. Aligned datasets, trimmed matrices, log files, and trees in nexus format can be found in Data S1.

The sequence identity and similarity of the CSW subunits were investigated, and sequence logos were prepared for manually selected conserved regions using WebLogo [71]. The selected sequences are annotated in Table S13.

4.3. Structure and Sequence Comparison Between Various Longin Proteins

We employed several approaches to investigate the relationship between C9orf72, SMCR8, FLCN, FNIP, NPRL2, and NPRL3 in terms of their sequence and structure and to compare them to other longin domain‐containing proteins. For these analyses, we used a test dataset comprising six well‐supported homologs from diverse eukaryotes per protein for the six proteins of interest plus the following longin protein sampling: AP1‐3 sigma subunits, AP2‐4 mu subunits, BET5/TRAPPC1, MON1, SEC22, DENND1, DENND10, and AVL9. Regions corresponding to the longin domains were extracted from the sequences based on cursory secondary structure prediction by SWISS‐MODEL [72], creating three parallel datasets of full‐length proteins, longin regions, and nonlongin regions (if present), respectively (Table S10, Figure S3, Data S1). All versus all BLAST searches were performed on each of the datasets to identify even partial sequence homology between different longin proteins (the hits retrieving the same protein were disregarded, as well as hits with e‐value above 1). Additionally, sequence identity and similarity were calculated from a pairwise MAFFT alignment for every pair of full‐length proteins using a custom script (Table S11, Data S1).

A subset of the longin region sequences (three representatives per protein) was modeled by AlphaFold [73] on the ColabFold platform (https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb, [74]). A guide tree and structure‐based sequence alignment of these longin domains was then produced using FoldMason (https://search.foldseek.com/foldmason, [75]), and a maximum likelihood tree was additionally constructed based on the structure‐based alignment by IQ‐TREE2 with LG + C20 + G4 matrix and 1000 ultrafast bootstraps (Figures S4 and S5, Data S1).

4.4. Secondary Structure of the CSW Complex

To compare the structures of the full‐length CSW proteins, secondary structures of C9orf72, SMCR8, and WDR41 were predicted by AlphaFold for a subset of taxonomically representative organisms in which all three subunits were identified (C. owczarzaki, P. atlantis, A. castellanii , D. rotans, M. sporadica LBC3, and Colponemidia strain Colp10). The models were aligned to a reference cryo‐EM‐based model of the human CSW complex [76], and their noninformative and disordered regions were manually removed using PyMol (http://www.pymol.org/pymol). Structural homology of these models was investigated, and the structure‐guided alignments and guide trees were generated using FoldMason [75]; all pair‐wise structure alignments were also generated and scored using TM‐align (https://zhanggroup.org/TM‐align/) [77]. The FoldMason alignments and trees are available in Data S1, PAE and pLDTT plots for the models are shown in Figures S8–S10, and TM‐score matrices for the structure alignments are given in Table S12.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting Information Figure.

Data S2. Supporting Information Tables.

Data S3. Supporting Information.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France, and grant ANR‐20‐ce13‐0007 from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche, France, to C.L.J. Research in the Dacks Lab is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RES0043758 and RES0046091).

Novák Vanclová A. M. G., Jackson C. L., and Dacks J. B., “Eukaryote‐Wide Distribution of a Family of Longin Domain‐Containing GAP Complexes for Small GTPases ,” Traffic 26, no. 7‐9 (2025): e70016, 10.1111/tra.70016.

Funding: This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France, and grant ANR‐20‐CE13‐0007 from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche, France, to C.L.J. Research in the Dacks Lab is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RES0043758 and RES0046091).

Contributor Information

Catherine L. Jackson, Email: cathy.jackson@ijm.fr.

Joel B. Dacks, Email: dacks@ualberta.ca.

Data Availability Statement

No new materials nor code were generated for this manuscript. All data is included in Supporting Information.

References

- 1. Donaldson J. G. and Jackson C. L., “ARF Family G Proteins and Their Regulators: Roles in Membrane Transport, Development and Disease,” Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 12 (2011): 362–375, 10.1038/nrm3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sztul E., Chen P.‐W., Casanova J. E., et al., “ARF GTPases and Their GEFs and GAPs: Concepts and Challenges,” Molecular Biology of the Cell 30 (2019): 1249–1271, 10.1091/mbc.E18-12-0820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ishida M., Oguchi E., and Fukuda M., “Multiple Types of Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factors (GEFs) for Rab Small GTPases,” Cell Structure and Function 41 (2016): 61–79, 10.1247/csf.16008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levine T. P., Daniels R. D., Wong L. H., Gatta A. T., Gerondopoulos A., and Barr F. A., “Discovery of New Longin and Roadblock Domains That Form Platforms for Small GTPases in Ragulator and TRAPP‐II,” Small GTPases 4 (2013): 62–69, 10.4161/sgtp.24262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marat A. L., Dokainish H., and McPherson P. S., “DENN Domain Proteins: Regulators of Rab GTPases,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 286 (2011): 13791–13800, 10.1074/jbc.R110.217067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoshimura S., Gerondopoulos A., Linford A., Rigden D. J., and Barr F. A., “Family‐Wide Characterization of the DENN Domain Rab GDP‐GTP Exchange Factors,” Journal of Cell Biology 191 (2010): 367–381, 10.1083/jcb.201008051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Inoue H. and Randazzo P. A., “Arf GAPs and Their Interacting Proteins,” Traffic 8 (2007): 1465–1475, 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schlacht A., Herman E. K., Klute M. J., Field M. C., and Dacks J. B., “Missing Pieces of an Ancient Puzzle: Evolution of the Eukaryotic Membrane‐Trafficking System,” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 6 (2014): a016048, 10.1101/cshperspect.a016048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. East M. P., Bowzard J. B., Dacks J. B., and Kahn R. A., “ELMO Domains, Evolutionary and Functional Characterization of a Novel GTPase‐Activating Protein (GAP) Domain for Arf Protein Family GTPases,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 287 (2012): 39538–39553, 10.1074/jbc.M112.417477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bos J. L., Rehmann H., and Wittinghofer A., “GEFs and GAPs: Critical Elements in the Control of Small G Proteins,” Cell 129 (2007): 865–877, 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frasa M. A. M., Koessmeier K. T., Ahmadian M. R., and Braga V. M. M., “Illuminating the Functional and Structural Repertoire of Human TBC/RABGAPs,” Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 13 (2012): 67–73, 10.1038/nrm3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Franceschi N., Wild K., Schlacht A., Dacks J. B., Sinning I., and Filippini F., “Longin and gaf Domains: Structural Evolution and Adaptation to the Subcellular Trafficking Machinery,” Traffic 15 (2014): 104–121, 10.1111/tra.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Homma Y., Hiragi S., and Fukuda M., “Rab Family of Small GTPases: An Updated View on Their Regulation and Functions,” FEBS Journal 288 (2021): 36–55, 10.1111/febs.15453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mizuno‐Yamasaki E., Rivera‐Molina F., and Novick P., “GTPase Networks in Membrane Traffic,” Annual Review of Biochemistry 81 (2012): 637–659, 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052810-093700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jackson C. L., Ménétrey J., Sivia M., Dacks J. B., and Eliáš M., “An Evolutionary Perspective on Arf Family GTPases,” Current Opinion in Cell Biology 85 (2023): 102268, 10.1016/j.ceb.2023.102268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kjos I., Vestre K., Guadagno N. A., Borg Distefano M., and Progida C., “Rab and Arf Proteins at the Crossroad Between Membrane Transport and Cytoskeleton Dynamics,” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—Molecular Cell Research 1865 (2018): 1397–1409, 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li F.‐L. and Guan K.‐L., “The Arf Family GTPases: Regulation of Vesicle Biogenesis and Beyond,” BioEssays 45 (2023): 2200214, 10.1002/bies.202200214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eme L., Tamarit D., Caceres E. F., et al., “Inference and Reconstruction of the Heimdallarchaeial Ancestry of Eukaryotes,” Nature 618 (2023): 992–999, 10.1038/s41586-023-06186-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zaremba‐Niedzwiedzka K., Caceres E. F., Saw J. H., et al., “Asgard archaea Illuminate the Origin of Eukaryotic Cellular Complexity,” Nature 541 (2017): 353–358, 10.1038/nature21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Avcı B., Panagiotou K., Albertsen M., Ettema T. J. G., Schramm A., and Kjeldsen K. U., “Peculiar Morphology of Asgard Archaeal Cells Close to the Prokaryote‐Eukaryote Boundary,” MBio 16 (2025): e00327‐25, 10.1128/mbio.00327-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Imachi H., Nobu M. K., Nakahara N., et al., “Isolation of an Archaeon at the Prokaryote–Eukaryote Interface,” Nature 577 (2020): 519–525, 10.1038/s41586-019-1916-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Imachi H., Nobu M. K., Ishii S., et al., “Eukaryotes' Closest Relatives Are Internally Simple Syntrophic archaea.” 2025, 10.1101/2025.02.26.640444. [DOI]

- 23. Vargová R., Chevreau R., Alves M., et al., “The Asgard Archaeal Origins of Arf Family GTPases Involved in Eukaryotic Organelle Dynamics,” Nature Microbiology 10 (2025): 495–508, 10.1038/s41564-024-01904-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhu J., Xie R., Ren Q., et al., “Asgard Arf GTPases Can Act as Membrane‐Associating Molecular Switches With the Potential to Function in Organelle Biogenesis,” Nature Communications 16 (2025): 2622, 10.1038/s41467-025-57902-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barlow L. D. and Dacks J. B., “Seeing the Endomembrane System for the Trees: Evolutionary Analysis Highlights the Importance of Plants as Models for Eukaryotic Membrane‐Trafficking,” Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 80 (2018): 142–152, 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klinger C. M., Spang A., Dacks J. B., and Ettema T. J. G., “Tracing the Archaeal Origins of Eukaryotic Membrane‐Trafficking System Building Blocks,” Molecular Biology and Evolution 33 (2016): 1528–1541, 10.1093/molbev/msw034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. More K., Klinger C. M., Barlow L. D., and Dacks J. B., “Evolution and Natural History of Membrane Trafficking in Eukaryotes,” Current Biology 30 (2020): R553–R564, 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DeJesus‐Hernandez M., Mackenzie I. R., Boeve B. F., et al., “Expanded GGGGCC Hexanucleotide Repeat in Non‐Coding Region of C9ORF72 Causes Chromosome 9p‐Linked Frontotemporal Dementia and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis,” Neuron 72 (2011): 245–256, 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levine T. P., Daniels R. D., Gatta A. T., Wong L. H., and Hayes M. J., “The Product of C9orf72, a Gene Strongly Implicated in Neurodegeneration, Is Structurally Related to DENN Rab‐GEFs,” Bioinformatics 29 (2013): 499–503, 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Renton A. E., Majounie E., Waite A., et al., “A Hexanucleotide Repeat Expansion in C9ORF72 Is the Cause of Chromosome 9p21‐Linked ALS‐FTD,” Neuron 72 (2011): 257–268, 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jansen R. M. and Hurley J. H., “Longin Domain gap Complexes in Nutrient Signalling, Membrane Traffic and Neurodegeneration,” FEBS Letters 597 (2023): 750–761, 10.1002/1873-3468.14538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Su M.‐Y., Fromm S. A., Remis J., Toso D. B., and Hurley J. H., “Structural Basis for the ARF GAP Activity and Specificity of the C9orf72 Complex,” Nature Communications 12 (2021): 3786, 10.1038/s41467-021-24081-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tang D., Sheng J., Xu L., Yan C., and Qi S., “The C9orf72‐SMCR8‐WDR41 Complex Is a GAP for Small GTPases,” Autophagy 16 (2020): 1542–1543, 10.1080/15548627.2020.1779473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang D., Iyer L. M., He F., and Aravind L., “Discovery of Novel DENN Proteins: Implications for the Evolution of Eukaryotic Intracellular Membrane Structures and Human Disease,” Frontiers in Genetics 3 (2012): 283, 10.3389/fgene.2012.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cui Z., Joiner A. M. N., Jansen R. M., and Hurley J. H., “Amino Acid Sensing and Lysosomal Signaling Complexes,” Current Opinion in Structural Biology 79 (2023): 102544, 10.1016/j.sbi.2023.102544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lawrence R. E., Fromm S. A., Fu Y., et al., “Structural Mechanism of a Rag GTPase Activation Checkpoint by the Lysosomal Folliculin Complex,” Science 366 (2019): 971–977, 10.1126/science.aax0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu G. Y. and Sabatini D. M., “mTOR at the Nexus of Nutrition, Growth, Ageing and Disease,” Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 21 (2020): 183–203, 10.1038/s41580-019-0199-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meng J. and Ferguson S. M., “GATOR1‐Dependent Recruitment of FLCN–FNIP to Lysosomes Coordinates Rag GTPase Heterodimer Nucleotide Status in Response to Amino Acids,” Journal of Cell Biology 217 (2018): 2765–2776, 10.1083/jcb.201712177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Amick J., Tharkeshwar A. K., Talaia G., and Ferguson S. M., “PQLC2 Recruits the C9orf72 Complex to Lysosomes in Response to Cationic Amino Acid Starvation,” Journal of Cell Biology 219 (2019): e201906076, 10.1083/jcb.201906076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Talaia G., Amick J., and Ferguson S. M., “Receptor‐Like Role for PQLC2 Amino Acid Transporter in the Lysosomal Sensing of Cationic Amino Acids,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (2021): e2014941118, 10.1073/pnas.2014941118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dokudovskaya S., Waharte F., Schlessinger A., et al., “A Conserved Coatomer‐Related Complex Containing Sec13 and Seh1 Dynamically Associates With the Vacuole in Saccharomyces cerevisiae ,” Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 10 (2011): M110.006478, 10.1074/mcp.M110.006478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. The UniProt Consortium , “UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2025,” Nucleic Acids Research 53 (2025): D609–D617, 10.1093/nar/gkae1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Burki F., Roger A. J., Brown M. W., and Simpson A. G. B., “The New Tree of Eukaryotes,” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 35 (2020): 43–55, 10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eglit Y., Shiratori T., Jerlström‐Hultqvist J., et al., “ Meteora sporadica, a Protist With Incredible Cell Architecture, Is Related to Hemimastigophora,” Current Biology 34 (2024): 451–459.e6, 10.1016/j.cub.2023.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schön M. E., Zlatogursky V. V., Singh R. P., et al., “Single Cell Genomics Reveals Plastid‐Lacking Picozoa Are Close Relatives of Red Algae,” Nature Communications 12 (2021): 6651, 10.1038/s41467-021-26918-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Williamson K., Eme L., Baños H., et al., “A Robustly Rooted Tree of Eukaryotes Reveals Their Excavate Ancestry,” Nature 640 (2025): 1–8, 10.1038/s41586-025-08709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Torruella G., Galindo L. J., Moreira D., and López‐García P., “Phylogenomics of Neglected Flagellated Protists Supports a Revised Eukaryotic Tree of Life,” Current Biology 35 (2025): 198–207.e4, 10.1016/j.cub.2024.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Anderson I. J. and Loftus B. J., “ Entamoeba histolytica : Observations on Metabolism Based on the Genome Sequence,” Experimental Parasitology 110 (2005): 173–177, 10.1016/j.exppara.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Novák L., Zubáčová Z., Karnkowska A., et al., “Arginine Deiminase Pathway Enzymes: Evolutionary History in Metamonads and Other Eukaryotes,” BMC Evolutionary Biology 16 (2016): 197, 10.1186/s12862-016-0771-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kawano‐Kawada M., Manabe K., Ichimura H., et al., “A PQ‐Loop Protein Ypq2 Is Involved in the Exchange of Arginine and Histidine Across the Vacuolar Membrane of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ,” Scientific Reports 9 (2019): 15018, 10.1038/s41598-019-51531-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Spang A., Saw J. H., Jørgensen S. L., et al., “Complex Archaea That Bridge the Gap Between Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes,” Nature 521 (2015): 173–179, 10.1038/nature14447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dombrowski N., Teske A. P., and Baker B. J., “Expansive Microbial Metabolic Versatility and Biodiversity in Dynamic Guaymas Basin Hydrothermal Sediments,” Nature Communications 9 (2018): 4999, 10.1038/s41467-018-07418-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dong X., Greening C., Rattray J. E., et al., “Metabolic Potential of Uncultured Bacteria and Archaea Associated With Petroleum Seepage in Deep‐Sea Sediments,” Nature Communications 10 (2019): 1816, 10.1038/s41467-019-09747-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liang R., Li Z., Lau Vetter M. C. Y., et al., “Genomic Reconstruction of Fossil and Living Microorganisms in Ancient Siberian Permafrost,” Microbiome 9 (2021): 110, 10.1186/s40168-021-01057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wong H. L., MacLeod F. I., White R. A., Visscher P. T., and Burns B. P., “Microbial Dark Matter Filling the Niche in Hypersaline Microbial Mats,” Microbiome 8 (2020): 135, 10.1186/s40168-020-00910-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhao R. and Biddle J. F., “Helarchaeota and Co‐Occurring Sulfate‐Reducing Bacteria in Subseafloor Sediments From the Costa Rica Margin,” ISME Communications 1 (2021): 25, 10.1038/s43705-021-00027-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang J., Feng X., Li M., et al., “Deep Origin of Eukaryotes Outside Heimdallarchaeia Within Asgardarchaeota,” Nature 642 (2025): 1–9, 10.1038/s41586-025-08955-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tran L. T., Akıl C., Senju Y., and Robinson R. C., “The Eukaryotic‐Like Characteristics of Small GTPase, Roadblock and TRAPPC3 Proteins From Asgard Archaea,” Communications Biology 7 (2024): 1–13, 10.1038/s42003-024-05888-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hatano T., Palani S., Papatziamou D., et al., “Asgard Archaea Shed Light on the Evolutionary Origins of the Eukaryotic Ubiquitin‐ESCRT Machinery,” Nature Communications 13 (2022): 3398, 10.1038/s41467-022-30656-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Serfontein J., Nisbet R. E. R., Howe C. J., and de Vries P. J., “Evolution of the TSC1/TSC2‐TOR Signaling Pathway,” Science Signaling 3 (2010): ra49, 10.1126/scisignal.2000803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. van Dam T. J. P., Zwartkruis F. J. T., Bos J. L., and Snel B., “Evolution of the TOR Pathway,” Journal of Molecular Evolution 73 (2011): 209–220, 10.1007/s00239-011-9469-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Richter D. J., Berney C., Strassert J. F. H., et al., “EukProt: A Database of Genome‐Scale Predicted Proteins Across the Diversity of Eukaryotes,” Peer Community Journal 2 (2022): e56, 10.24072/pcjournal.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Blaz J., Galindo L. J., Heiss A. A., et al., “One High Quality Genome and Two Transcriptome Datasets for New Species of Mantamonas, a Deep‐Branching Eukaryote Clade,” Scientific Data 10 (2023): 603, 10.1038/s41597-023-02488-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Záhonová K., Low R. S., Warren C. J., et al., “Evolutionary Analysis of Cellular Reduction and Anaerobicity in the Hyper‐Prevalent Gut Microbe Blastocystis,” Current Biology 33 (2023): 2449–2464.e8, 10.1016/j.cub.2023.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Valach M., Moreira S., Petitjean C., et al., “Recent Expansion of Metabolic Versatility in Diplonema papillatum, the Model Species of a Highly Speciose Group of Marine Eukaryotes,” BMC Biology 21 (2023): 99, 10.1186/s12915-023-01563-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tikhonenkov D. V., Mikhailov K. V., Gawryluk R. M. R., et al., “Microbial Predators Form a New Supergroup of Eukaryotes,” Nature 612 (2022): 714–719, 10.1038/s41586-022-05511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Katoh K. and Standley D. M., “MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability,” Molecular Biology and Evolution 30 (2013): 772–780, 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Capella‐Gutiérrez S., Silla‐Martínez J. M., and Gabaldón T., “trimAl: A Tool for Automated Alignment Trimming in Large‐Scale Phylogenetic Analyses,” Bioinformatics 25 (2009): 1972–1973, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Minh B. Q., Schmidt H. A., Chernomor O., et al., “IQ‐TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era,” Molecular Biology and Evolution 37 (2020): 1530–1534, 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Criscuolo A. and Gribaldo S., “BMGE (Block Mapping and Gathering With Entropy): A New Software for Selection of Phylogenetic Informative Regions From Multiple Sequence Alignments,” BMC Evolutionary Biology 10 (2010): 210, 10.1186/1471-2148-10-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J.‐M., and Brenner S. E., “WebLogo: A Sequence Logo Generator,” Genome Research 14 (2004): 1188–1190, 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Waterhouse A., Bertoni M., Bienert S., et al., “SWISS‐MODEL: Homology Modelling of Protein Structures and Complexes,” Nucleic Acids Research 46 (2018): W296–W303, 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., et al., “Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction With AlphaFold,” Nature 596 (2021): 583–589, 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mirdita M., Schütze K., Moriwaki Y., Heo L., Ovchinnikov S., and Steinegger M., “ColabFold: Making Protein Folding Accessible to All,” Nature Methods 19 (2022): 679–682, 10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gilchrist C. L. M., Mirdita M., and Steinegger M., Multiple Protein Structure Alignment at Scale With FoldMason (bioRxiv, 2024), 10.1101/2024.08.01.606130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Su M.‐Y., Fromm S. A., Zoncu R., and Hurley J. H., “Structure of the C9orf72 Arf GAP Complex Haploinsufficient in ALS and FTD,” Nature 585 (2020): 251–255, 10.1038/s41586-020-2633-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhang Y., “TM‐Align: A Protein Structure Alignment Algorithm Based on the TM‐Score,” Nucleic Acids Research 33 (2005): 2302–2309, 10.1093/nar/gki524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting Information Figure.

Data S2. Supporting Information Tables.

Data S3. Supporting Information.

Data Availability Statement

No new materials nor code were generated for this manuscript. All data is included in Supporting Information.