Abstract

Terbium-155 (t 1/2 = 5.32 days) is one of four medically relevant radioisotopes of terbium. It is of interest to the field as a suitable diagnostic counterpart for therapeutic radiolanthanides, as its decay scheme includes γ-rays that are suitable for single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging. Additionally, 155Tb has an Auger electron (AE) yield that is viable for AE therapy. There are several direct and indirect production routes that can produce 155Tb. Two possible direct routes include proton irradiation on gadolinium targets via 155Gd(p,n)155Tb and 156Gd(p,2n)155Tb. The 155Gd(p,n)155Tb reaction is accessible at incident proton beam energies of ∼10 MeV, whereas the 156Gd(p,2n)155Tb nuclear reaction requires ∼18 MeV. This study aims to investigate the production of 155Tb from natGd through the natGd(p,x) nuclear reaction, wherein both (p,n) and (p,2n) reactions were leveraged, and the purification using a three-column ion chromatography method. Using this system, recoveries of radioterbium of up to 97% were achieved in addition to high recoveries of the Gd target material, illustrating the suitability of this technique for enriched targets.

1. Introduction

Theranostics, a portmanteau of the words therapeutic and diagnostic, aims to create techniques to image and treat malignant diseases using chemically identical or similar agents. An example of this is the positron emission tomography (PET) tracer [68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE, which is used to determine if a patient is a candidate for a therapy with matched [177Lu]Lu-DOTATATE β-emitting agent. This idea can be further improved by using elementally matched theranostic pairs: two radioisotopes of the same element, one with diagnostic potential and one with therapeutic potential. Examples of elementally matched pairs include 43,44/47Sc, 64/67Cu, 203/212Pb, and 152,155/149,161Tb. , This allows for identical pharmacokinetics of the imaging and therapeutic agents, leading to predictable biodistribution and dosimetry prior to administering a therapeutic dose.

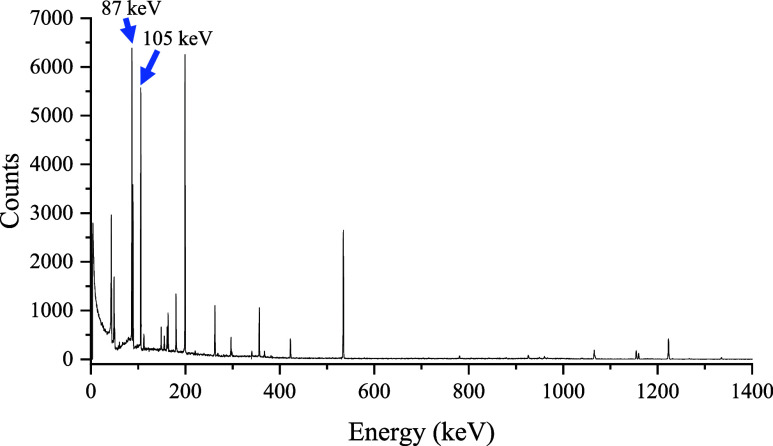

Tb has four medically relevant radioisotopes, 149Tb, 152Tb, 155Tb, and 161Tb, which encompass four medically relevant decay modes, α, β+, low-energy γ-ray emissions, and β–. 155Tb and 161Tb show potential as a true theranostic pair, where 155Tb is suitable for SPECT imaging and 161Tb is suitable for β– therapy. 155Tb [E γ = 87 keV (32%), 105 keV (25%), t 1/2 = 5.3 d] could be a promising addition to the SPECT radioisotope catalog for studies where longer time points are needed, as it has similar low-energy γ-ray profiles to 99mTc [E γ = 141 keV (89%), t 1/2 = 6 h] and 111In [E γ = 245 keV (94%), 171 keV (91%), t 1/2 = 2.8 d]. , In addition, 155Tb is also a promising AE therapeutic candidate with an AE yield similar to 123I (13 AE/decay). Both nuclides can be produced from the irradiation of gadolinium targets. ,

Natural Gd consists of 7 isotopes including 152Gd (0.2%), 154Gd (2.18%), 155Gd (14.8%), 156Gd (20.47%), 157Gd (15.65%), 158Gd (24.84%), and 160Gd (21.86%). Since natural Gd contains a significant percentage of 155Gd and 156Gd, it can be utilized as an inexpensive route to explore the production of 155Tb via the natGd(p,x) nuclear reaction to specifically produce 155Tb through the 155Gd(p,n) and 156Gd(p,2n) reactions. Reactions that occur on the other stable isotopes of Gd can lead to the production of several radiocontaminants when natural Gd is irradiated, as shown in Table . Previous studies have conducted cross-sectional measurements for the production of Terbium isotopes on natural Gd foils as well as 155Gd oxide and 156Gd oxide targets. , This present work investigated the production and purification of 155Tb from natural abundance Gd targets.

1. Isotopes Produced via Proton Irradiation of Natural Gd Targets ,

| target material (abundance) | nuclear reaction | half-life | threshold (MeV) | daughter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 152 Gd (0.2%) | 152Gd(p,n)152Tb | 17.5 h | 7.5 | 152Gd (stable) |

| 152Gd(p,2n)151Tb | 17.6 h | 12.5 | 151Gd (123.9 d) | |

| 154 Gd (2.18%) | 154Gd(p,n) 154Tb | 21.5 h | 6 | 154Gd (stable) |

| 154Gd(p,n)154mTb | 22.7 h | 6 | 154Tb (21.5 h) & 154Gd (stable) | |

| 154Gd(p,n)154m2Tb | 9.4 h | 6 | ||

| 154Gd(p,2n) 153Tb | 2.34 d | 11.6 | 153Gd (240.4 d) | |

| 155 Gd (14.8%) | 155Gd(p,n)155Tb | 5.32 d | 4 | 155Gd (stable) |

| 156 Gd (20.47%) | 156Gd(p,n)156Tb | 5.35 d | 6.6 | 156Gd (stable) |

| 156Gd(p,2n)155Tb | 5.32 d | 11 | 155Gd (stable) | |

| 157 Gd (15.65%) | 157Gd(p,n)157Tb | 71 y | 5 | 157Gd (stable) |

| 158 Gd (24.84%) | 158Gd(p,n)158Tb | 180 y | 5 | 158Gd (stable) |

| 160 Gd (21.86%) | 160Gd(p,n)160Tb | 72.3 d | 12.5 | 160Dy (stable) |

The development of purification methods to separate Tb from Gd targets is challenging due to the similar chemical characteristics of the lanthanides. Separation of the lanthanides is an obstacle that many researchers have addressed since these elements possess similar sizes in ionic radii and exist as trivalent cations. , However, many of these separation methods have been developed for the recovery of rare earth elements (REEs) from ore for one of their many applications (magnets, catalysts, batteries, etc.) or other larger-scale applications such as nuclear fuel reprocessing. − In nuclear medicine, the recovery of the man-made radioactive material is typically performed on a tracer level scale working with <μg to pg levels of radioactive material where these radionuclides are residing in >mg to g of target material with the potential of small-scale radiocontaminants, environmental contaminants or impurities in the target material. Due to this tracer scale limitation, the purification needs to focus on minimal contamination in the final product to prevent chemistry challenges downstream. While liquid–liquid extractions (LLEs) have been utilized for lanthanide separations, they have potential disadvantages that may not be suited for this application, including increased solvent consumption involving organics, increased operation time with multiple steps, and decreased extraction efficiency, and could be challenging to automate. , Thus, the purification of lanthanides in nuclear medicine has centered on solid phase extractions (SPEs), such as ionic chromatography (cation-exchange resins) for separating neighboring nuclides. − Other promising resins leverage the small differences in ionic radii and charge densities such as the commercially available LN series extractants (Triskem, Eichrom). , Furthermore, modifications such as aromatic groups in the solid support and small amounts of long-chain alcohols added to the organic phase allow mixed organophosphoric, organophosphonic, and organophosphinic acid extractants to be more resistant to radiolysis while increasing selectivity when compared to traditional lanthanide resins such as LN. ,, The inert support for resins such as TK212 also shows an elevated capacity for the extractants compared to unmodified versions. These types of resin chromatography also have the capacity to address dosimetry concerns by implementation into semi- or fully automated modules and direct employment into shielding cells. ,,− Specifically, the purification of radioterbium has been explored in many research groups for its unique decay characteristics spread across the four medically relevant radioisotopes. Unfortunately, many of the chromatography systems in the literature cater to smaller masses of the Gd target material (<40 mg), noting a limited loading capacity. ,

This work aims to streamline the Gd/Tb separation with a high Gd/Tb ratio (106) while maintaining a high recovery of the Tb and Gd species (for target recycling) and radiochemical purity of the final product. The purification presented here may also be applied to optimize production in the future with enriched Gd targets, alluding to the importance of recovering the Gd target material.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Materials

All materials used were of trace metal or analytical grade. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37% by weight, 99.999%) and nitric acid (HNO3, 67–70% by weight, 99.999%) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH). Twenty-nine milliliters and 53 mL of prepacked TK212 columns and 2 mL of prepacked TK221 columns with 700 mg of resin and 1 mL A8 columns prepacked with 670 mg of resin were provided by Triskem International (Triskem International, Bruz, France). Water was obtained from a deionized 18.2 M Ω-cm Milli-Q system (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Tubing, column adapters, ferrules, and fittings were all ordered from IDEX Health & Science (IDEX Corp., Northbrook, IL).

All other materials were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH) unless stated otherwise.

All radioactive elements were handled under ALARA principles in laboratories equipped with radiological fume hoods and shielding cells to handle radioactive materials appropriately, including all waste streams.

2.2. Target Design

Gd foils (Goodfellow Advanced Materials, Pittsburgh, PA) of natural abundance and 0.5 mm nominal thickness were cut into disks of 10 mm diameter and weight of approximately 300 mg. Tantalum (Ta) sheets with a purity of 99.98% and thickness of 2 mm, (ESPI Metals, Ashland, OR) were cut into a 2.5 cm diameter coins and a 1 mm deep divot was machined into the center (Figure ) (Ta coin). Ta foils, 0.1 mm thick and 99.98% pure (ESPI Metals, Ashland, OR), were punched into circles with a 10 mm diameter and placed into the divot of the Ta coin against the Gd foil as a proton beam degrader. The foils were secured in place by a stainless steel retaining ring (McMaster Carr, Elmhurst, IL). The target design is shown in Figure A,B.

1.

(A) Photograph of the natural Gd target configuration used for the irradiation of Gd targets without the proton beam degrader in the divot of the 2 mm Ta coin. (B) Photograph of the full natural Gd target configuration including the 0.1 mm Ta foil proton beam degrader and the stainless steel retaining ring. (C) Schematic of the solid target station that demonstrates the helium and water cooling.

2.3. Irradiation Parameters

The stopping and range of ions in matter (SRIM) was used to determine the energy of the proton beam after exiting the target. All bombardments were performed on a TR-24 Cyclotron instrument (Advanced Cyclotron Systems Inc.). This target configuration was irradiated with an incident proton beam energy of 17.5–18 MeV (15.3–15.6 MeV on the Gd target material) at 10–20 μA for 15 to 60 min. Following the Gd foil, the proton beam had an exit energy of 8.5–8.1 MeV and was stopped in a 1 mm Ta backing. The target was cooled by helium gas on the front of the target, while the back of the target was cooled by water, as illustrated in Figure C.

2.4. Separation Procedure

Two different column sizes, one 30 cm × 1.1 cm and one 30 cm × 1.5 cm with an internal volume of 29 and 53 mL, respectively, packed with 15 and 25 g of TK212 resin (Triskem International, Bruz, France), were investigated to purify the Tb from the target material. Columns were connected to a REAXUS PR class 100 mL PEEK dual piston pump to control the flow rate during purification. Columns were conditioned with three column volumes (CVs) of 0.05 M HCl, where the flow rate was increased from 1 to 5 mL/min during that period, with 5 mL/min utilized for the rest of the purification.

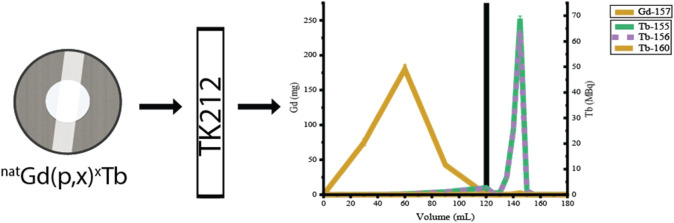

Irradiated Gd foils were dissolved in 7.8 mL of 2 M HCl at 50 °C, and 10–100 μL samples were taken from this dissolution for further analysis via ICP-MS and γ-ray spectroscopy. The dissolution solution was diluted to 0.05 M HCl with DI water and loaded onto a TK212 column. A 2 CV wash of 0.05 M HCl was eluted, and the Gd target material was eluted with 0.3 M HNO3 while the Tb was eluted with either 200 mL of 0.5 M HNO3 or 50 mL of 3.5 M HNO3. A schematic form of this separation procedure is presented in Figure .

2.

Schematic of the separation procedure designed to separate 155Tb from the natGd target material. B1: Beaker used to dissolve and hold the target for the first load onto the TK212 resin; 50 mL conical vials used to hold the eluents 0.3 M HNO3 for Gd for the second load onto the TK212 resin and 0.5 or 3.5 M HNO3 for Tb eluent for the third load onto the TK212 resin. The Reaxus piston pump was utilized to load each of these solutions at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. The respective column fractions were then allocated to either waste, Gd collection, or Tb collection.

2.5. Nitrate Removal and Volume Reduction

The Tb elution was further purified with two additional columns in order to remove any nitrates from the system and convert the Tb to a TbCl3 species. Two milliliters of TK221 was conditioned with 10 mL of 0.5 M HNO3 before the Tb fraction was loaded with a flow rate of 5 mL/min. The TK221 was rinsed with 5 mL of 0.5 M HNO3, followed by 5 mL of 0.1 M HNO3 to reduce the contact of other metallic impurities such as Fe. All of the HNO3 on the column was removed with 10 mL of air. Finally, Tb was eluted with 0.05 M HCl at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

Next, a 1 mL A8 column was utilized for additional nitrate removal. The column was conditioned with 15 mL of 0.05 M HCl before the Tb elution from the TK221 column was loaded onto the A8 column; 10 mL of air was pushed through the column to elute the Tb.

2.6. Test Labeling with DOTATATE

To ensure the purified Tb (purified with TK212 and nitrate removal with TK221 and A8 columns) had potential for preclinical use, the mixture of Tb isotopes was used to radiolabel DOTATATE (Macrocyclics, Plano, TX). Terbium ∼2 MBq (0.925 MBq of each 155,156Tb and 0.093 MBq of each 153,160Tb, while other isotopes of Tb were decayed or undetectable at the time of chelation) was added to a reaction mixture consisting of 0.05 M HCl and 0.5 M sodium acetate with a final pH of ∼4.5. DOTATATE (total volume of 100 μL with a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL) was added to obtain molar activities of up to 28 MBq/nmol. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. HPLC analysis was carried out using an Agilent 1620 HPLC instrument fitted with a Lablogic Flow-RAM radioactive detector (Sheffield, UK) to determine the radiolabeling yields of Tb-DOTATATE. Thirty microliter aliquots were analyzed using a C18 column (Waters, Symmetry C18 Column, 100Å, 5 μm, 4.6 mm × 150 mm) with a water: acetonitrile gradient mobile phase that started with 95% water and 5% acetonitrile and gradually changed to 5% water and 95% acetonitrile over a period of 30 min.

2.7. Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) Analysis

ICP-MS samples of the starting material and each of the fractions for the purification were diluted with 2% HNO3 to less than 1000 ppb of Gd. The samples were analyzed by ICP-MS (7900 Series: Agilent, Santa Clara, CA).

2.8. γ-ray Spectroscopy

Samples were analyzed using a high-purity germanium detector (Canberra S5000 and Canberra DSA1000; Ortek-Mertek, Oak Ridge, TN), and Canberra Genie 2000 software was used for data acquisition and analysis to quantify amounts of radioisotopes listed in Table . Aliquots of 10–100 μL (<37 kBq) were taken from the dissolved target material (2 M HCl) and after each 5–50 mL fraction during purification (0.3 – 3.5 M HNO3) and diluted to 1 mL with D.I. water in a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube and suspended in an acrylic holder at a distance of 246 mm from the HPGe detector. The dead time was consistently <5%. Energy and efficiency calibrations were performed using a mixed nuclide source in a sealed 1.5 mL centrifuge tube prepared by Eckert & Ziegler Analytics (Atlanta, GA). Efficiency–calibration spectra with a minimum photopeak area of 2 × 105 counts were collected and fitted to determine the relative detector efficiency. These geometries were maintained for all of the sample measurements.

2. Tb Isotopes with the Respective γ-Ray Energies (keV) Analyzed in the γ-Ray Spectrum after Irradiation of a Natural Gd Foil .

| Nuclide | 151Tb | 152Tb | 153Tb | 154Tb | 154mTb | 155Tb | 156Tb | 160Tb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| half-life | 17.6 h | 17.5 h | 2.34 h | 21.5 h | 22.7 h | 5.3 d | 5.4 d | 72.3 d |

| γ-ray energies (keV (Iγ%)) | 252 (26) | 344 (64) | 212 (9) | 1274 (11) | 226 (27) | 199 (41) | 966 (25) | |

| 287 (28) | 87 (32) | 356 (14) | ||||||

| 105 (25) | 534 (67) | |||||||

| 180 (8) | 1065 (11) | |||||||

| 367 (2) | 1154 (10) | |||||||

| 1222 (31) |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cyclotron Production Yields of 155Tb

Theoretical yields for natural gadolinium targets were calculated utilizing the cross sections reported in Vermeulen et al. , The theoretical and experimental yields determined by γ-ray spectroscopy for 155Tb in these experiments are shown in Table . The theoretical and experimental yields were found to be in reasonable agreement with the previously reported cross sections.

3. Proton Irradiation Parameters and the Resulting Theoretical and Experimental Yields of 155Tb.

| proton beam energy on target (MeV) | current (μA) | beam time (min) | theoretical yield10 (MBq) | experimental yield (MBq) | % error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15.3 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 11 ± 0.2 | 21 ± 2 |

| 15.4 | 15 | 15 | 21 | 21 ± 0.5 | 0 ± 3 |

| 15.6 | 20 | 60 | 112 | 107 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 |

The γ-ray spectrum of the proton-irradiated natural Gd targets showed emissions from 151Tb, 152Tb, 153Tb, 154Tb, 154mTb, 155Tb, 156Tb, and 160Tb. The physical half-lives and characteristic γ-rays are listed in Table , and the corresponding γ-ray spectra are listed in Figure .

3.

γ-Ray spectrum of the Tb isotopes produced after natural Gd target irradiation. The 155Tb characteristic photopeaks are labeled at 87 and 105 keV.

3.2. Purification of Tb from natGd with a 53 mL TK212 Column and 0.5 M Nitric Acid

TK212 columns (29 and 53 mL) were investigated for the separation of Gd and Tb isotopes. For the first separation process, 0.3 M HNO3 was used to elute the Gd target material, followed by 0.5 M HNO3 to elute the Tb isotopes, where all fractions were collected in 50 mL volumes. This created large volumes of solution for the Tb recovery as well as the Gd waste, equaling the total volumes of 250 mL for each element’s recovery. The recovery of 155Tb in Figure shows an 86 ± 4% recovery in a volume of 100 mL with a decontamination factor (DF) of 14,167.

4.

Separation profile for all species in natural Gd target irradiation and purification of the Tb isotopes (n = 2). The left y-axis displays the data collected from the ICP-MS for the stable nonradioactive species shown in the top half of the legend. The right y-axis displays the data collected via HPGe for all of the radioactive Tb species that were detected. Each isotope of the radioactive Tb is displayed in the lower half of the legend. The recovery yield was calculated to be 87 ± 5% for the natural Gd target material eluted in 0.3 M HNO3 and collected in fractions of 50 mL volumes. The recovery yield was calculated to be 86 ± 4% for Tb eluted in 0.5 M HNO3 in fractions of 50 mL volumes.

3.3. Purification of Tb from natGd with a 53 mL TK212 Column and 3.5 M Nitric Acid

To mitigate these large volumes of recovered material, an increase in HNO3 concentration was implemented to elute the Tb isotopes in a smaller volume. The Gd was still eluted utilizing 250 mL of 0.3 M HNO3, while the elution solution of the Tb isotopes was changed to 3.5 M HNO3 vs 0.5 M utilized in the previous section. The recovery of Tb increased to 97 ± 2% in the final volume of 20 mL, with 94 ± 2% of the activity in 10 mL and a DF of 21,286. These changes are shown in Figure , where the decrease in volume and increase in Tb recovery can be observed. The separation profile for all species in natural Gd target irradiation and purification of the Tb isotopes (n = 2) is shown in Figure . The left y-axis displays the data collected from the ICP-MS for the stable nonradioactive species shown in the top half of the legend. The right y-axis displays the data collected via HPGe for all of the radioactive Tb species that were detected, with each isotope of the radioactive Tb displayed in the lower half of the legend. The recovery yield was calculated to be 95 ± 2% for the natural Gd target material eluted in 0.3 M HNO3 and collected in 5 fractions of 50 mL, with the majority collected in the second fraction. The recovery yield was 97 ± 2% for the radioactive Tb eluted in 3.5 M HNO3 in 6 fractions of 10 mL, with the majority collected in the third fraction.

5.

Separation profile for all species in natural Gd target irradiation and purification of the Tb isotopes (n = 2). The left y-axis displays the data collected from the ICP-MS for the stable nonradioactive species shown in the top half of the legend. The right y-axis displays the data collected via HPGe for all of the radioactive Tb species that were detected, with each isotope of the radioactive Tb displayed in the lower half of the legend. The recovery yield was calculated to be 95 ± 2% for the natural Gd target material eluted in 0.3 M HNO3 and collected in 5 fractions of 50 mL, with the majority collected in the second fraction. The recovery yield was 97 ± 2% for the radioactive Tb eluted in 3.5 M HNO3 in 6 fractions of 10 mL, with the majority collected in the third fraction.

3.4. Purification of Tb from natGd with a 29 mL TK212 Column and 3.5 M HNO3

To further reduce the elution volumes, a smaller column with an internal volume of 29 mL was investigated in addition to the use of 3.5 M HNO3 to elute the Tb fraction. This resulted in a reduction in volume used to elute both the Gd target material and Tb activity from an initial 250 mL volume for the Gd fraction to 120 mL, as shown in Figure . A 93 ± 2% of the overall Tb activity was collected in 15 mL, with 64 ± 1% collected in a 5 mL fraction with a DF of 22,206. However, a modest Tb breakthrough was observed between the 60–90 and 90–120 mL 0.3 M HNO3 fractions from the column, totaling 4 ± 1% of the overall activity.

6.

Separation profile for natural Gd target irradiation and purification of the Tb isotopes (n = 2). The left y-axis displays the data collected from the ICP-MS for the stable nonradioactive species shown in the top half of the legend. The right y-axis displays the data collected via HPGe for all of the radioactive Tb species that were detected, with each isotope of the radioactive Tb displayed in the lower half of the legend. The recovery yield was calculated to be 99 ± 4% for the natural Gd target material eluted in 0.3 M HNO3 and collected in 4 fractions of 30 mL, with the majority collected in the second fraction. The recovery yield was 96 ± 2% for the radioactive Tb eluted in 3.5 M HNO3 in 12 fractions of 5 mL, with the majority collected in the fifth fraction.

The recovered Tb mixture was loaded onto a TK221 column to further reduce the volume and exchange the nitric acid medium with 0.05 M HCl, followed by an A8 column to remove the nitrates for further chelation studies; the chloride species TbCl3 is more suitable for the subsequent radiolabeling conditions. The Tb eluted from the TK221/A8 columns was recovered and analyzed by γ-ray spectroscopy with a 94 ± 3% recovery.

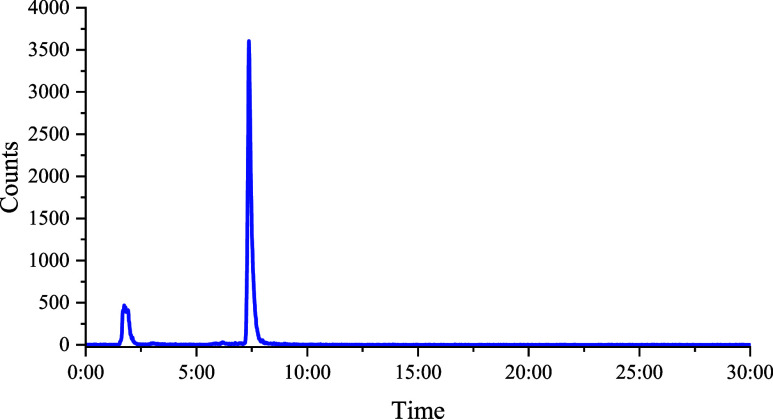

3.5. Radiolabeling of DOTATATE with Radioterbium

Radiolabeling of DOTATATE with Tb was performed with the mixture of radioactive Tb isotopes, as shown in Figure . During the time of HPLC analysis, some of the shorter-lived isotopes (151,152,154mTb) had decayed below detection limits. The results displayed a reproducible apparent molar activity (AMA) of 28 MBq/nmol, with >90% radiochemical yield. The results from the radiolabeling were analyzed by HPLC utilizing a gradient of water and acetonitrile, where the results are shown in Figure . The free Tb (TbCl3) had a retention time of 1 min and 44 s, while the Tb-DOTATATE species was clearly separated with a retention time of 7 min and 22 s.

7.

Radiolabeling of DOTATATE with 153,155,156,160Tb was analyzed via HPLC utilizing a mobile phase consisting of a gradient of water and acetonitrile moving from 95% water to 95% acetonitrile. The Tb-DOTATATE displayed a retention time of 7 min and 22 s with a radiochemical purity of >90%.

3.6. Discussion

These studies report data on the production, purification, and apparent molar activity of 155Tb. The production results are in line with theoretical calculations based on previous cross-sectional measurements. , The efficiency of the natGd target is limited due to several stable isotopes of Gd and the nuclear reactions that have varying thresholds and cross sections at the proton beam energies needed to produce 155Tb. Due to the several possible reactions on natGd targets, enriched 155Gd or 156Gd would need to be utilized for a higher purity of 155Tb needed for nuclear medicine applications. Characteristic γ-rays were identified for many radioterbium isotopes, including 151–156,160Tb. However, the three main isotopes of Tb that were found to be in the highest amounts were154,154mTb, 155Tb, and 156Tb. Fortunately, 154,154mTb [t 1/2 = 21.5 h, 22.7 h] will decay in a relatively short amount of time, within one-half-life of 155Tb [t 1/2 = 5.3 d]; 154,154mTb is near background. On the other hand, 156Tb [t 1/2 = 5.4 d] has a very similar half-life to 155Tb and would need to be minimized during production by utilizing enriched targets and specific proton beam energy windows to effectively select 155Tb while minimizing 156Tb production. Even though enriched materials will be needed for nuclear medicine applications, natGd production of 155Tb could be utilized as a cheaper alternative to investigate downstream optimization of Tb chemistry while exploring techniques to recycle the Gd target material.

The TK212 resin works by leveraging differences in the ionic radii and charge densities. By utilizing these differences, those with a smaller atomic number will elute first due to the extraction mechanism of the TK212 resin, where heavier lanthanides, possessing smaller ionic radii and higher charge densities, form more stable complexes with the extractant ligands on the resin, resulting in delayed elution. Therefore, the Gd elutes before Tb. For this work, we aimed to meet the needs of an increased loading capacity (>300 mg of Gd), and thus, the purification schemes implemented here do utilize a rather large bed volume. Additional optimization studies are currently ongoing to decrease both resin bed volume as well as solution volumes while maintaining the loading capacity. Further optimization could be explored by automating the purification to decrease the dose to personnel. Currently, the solutions introduced to the column are manually changed by moving the tubing to the corresponding vial in addition to changing vials for Gd, Tb, and waste collection, while the piston pump is used to regulate flow rate. Table presents a summary of the modifications within the purification technique and how they impacted the recovery percentage, volumes, separation factor, and total purification time. The initial change to a higher molarity of nitric acid to elute Tb demonstrated decreased recovery volumes and increased recovery, allowing for a purification time decrease of ∼30%. This small change also increased the decontamination factor by ∼30%. One final improvement to the purification decreased the column volume from 53 to 29 mL, which allowed for an overall total volume decrease while maintaining recovery yields. Since the volume was decreased, the procedure time was also decreased (∼24%) compared to the second purification method while keeping the decontamination factor constant.

4. Summary of the TK212 Purification Methods Described in This Work.

| TK212 column volume (mL) | HNO3 (M) for Gd elution | HNO3 (M) for Tb elution | Gd % recovery | Tb %recovery | Gd recovery volume (mL) | Tb recovery volume (mL) | total purification time (h) | DF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 53 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 87 ± 5% | 86 ± 4% | 150 | 100 | 3 | 14,167 |

| 53 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 95 ± 2% | 97 ± 2% | 150 | 20 | 2.1 | 21,286 |

| 29 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 99 ± 4% | 96 ± 2% | 120 | 20 | 1.6 | 22,206 |

The TK221 and A8 columns were utilized to reduce volume and remove nitrates in preparation for further chemistry and AMA analysis. Tb, being a hard Lewis acid, has a preference to bind to hard Lewis bases such as NO3 – over the borderline Lewis base Cl–. Therefore, removal of the nitrates is preferred to maintain an increased radiochemical purity and for binding to the hard donor atoms of oxygen and nitrogen that DOTATATE provides. The AMA reported (28 MBq/nmol) was comparable to previously reported AMA from Faveretto et al., who reported a AMA of 50 MBq/nmol using [155Tb]Tb-DOTATOC. Key differences in the radiolabeling procedure including the mixture of Tb isotopes, low activity, and temperature used for radiolabeling could be the cause of the lower AMA value of this work. Future experimentation will work toward optimizing the Tb chemistry parameters.

4. Conclusions

This work demonstrates the feasibility of separating radioterbium from irradiated gadolinium targets and the optimization, including reducing overall elution volumes used in the separations. During these experiments, the HNO3 concentration utilized to elute Tb from the TK212 column was modified from 0.5 to 3.5 M to decrease the overall volume of the recovered Tb solution by 80% and to increase the total recovery of the Tb and associated DF. The decrease in volume shortens the overall time it takes to move the Tb into the chemistry stages by eliminating an evaporation step and/or challenges due to low Tb concentration. The recovery of radioterbium for the initial purification method utilizing 0.5 M HNO3 and 53 mL of TK212 was also improved by the increase in HNO3 concentration from ∼87% to ∼ 97% (3.5 M HNO3 and a 53 mL TK212 column). To further improve the volume and overall time of the process, a smaller column (29 mL) of the TK212 was implemented that maintained the yield and DF for the purification while decreasing the overall volume collected and time by ∼47%. Chelation studies displayed promising results by utilizing the optimized purification method with modest apparent molar activity. These results establish a foundation for future investigations, which will focus on the irradiation and recycling of enriched 155Gd and 156Gd for high radionuclidic purity 155Tb as well as 155Tb chemistry.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Department of Energy Isotope Program under grant DESC0021269 (PI: Lapi). The authors acknowledge the support of all team members from Dr. Lapi’s group and the UAB Cyclotron Facility. Argonne National Laboratory’s contribution is based upon work supported by Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) funding from Argonne National Laboratory, provided by the Director, Office of Science, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available throughout the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Scarpa L., Buxbaum S., Kendler D., Fink K., Bektic J., Gruber L., Decristoforo C., Uprimny C., Lukas P., Horninger W., Virgolini I.. The 68Ga/177Lu theragnostic concept in PSMA targeting of castration-resistant prostate cancer: correlation of SUVmax values and absorbed dose estimates. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2017;44:788–800. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3609-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasi P. M., Maige C. L., Shahjehan F., Rodgers J. M., Aloszka D. L., Ritter A., Andrus M. L., Mcmillan J. M., Mody K., Sharma A., Jain M. K.. A Care Process Model to Deliver 177Lu-Dotatate Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy for Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors. Front. Oncol. 2019;8:663. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnovskaya O. O., Abramchuck D., Erofeev A., Gorelkin P., Kuznetsov A., Shemukhin A., Beloglazkina E. K.. Recent Advances in (64)Cu/(67)Cu-Based Radiopharmaceuticals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:9154. doi: 10.3390/ijms24119154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uygur, E. ; Sezgin, C. ; Parlak, Y. ; Karatay, K. B. ; Arikbasi, B. ; Avcibasi, U. ; Toklu, T. ; Barutca, S. ; Harmansah, C. ; Sozen, T. S. ; Maus, S. ; Scher, H. ; Aras, O. ; Gumuser, F. G. ; Muftuler, F. Z. B. . The Radiolabeling of [161Tb]-PSMA-617 by a Novel Radiolabeling Method and Preclinical Evaluation by In Vitro/In Vivo Methods Res. Square 2023. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3415703/v1. [DOI]

- Müller, C. ; van der Meulen, N. P. . Beyond Becquerel and Biology to Precision Radiomolecular Oncology: Festschrift in Honor of Richard P. Baum; Vikas Prasad, Ed.; Springer International Publishing, 2024; pp 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Favaretto C., Talip Z., Borgna F., Grundler P. V., Dellepiane G., Sommerhalder A., Zhang H., Schibli R., Braccini S., Müller C., van der Meulen N. P.. Cyclotron production and radiochemical purification of terbium-155 for SPECT imaging. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2021;6:37. doi: 10.1186/s41181-021-00153-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NuDat 2.8. Brookhaven National Laboratory Website, 2022. https://www.nndc.bnl.gov/nudat2/. Accessed May 24.

- Bolcaen J., Gizawy M. A., Terry S. Y. A., Paulo A., Cornelissen B., Korde A., Engle J., Radchenko V., Howell R. W.. Marshalling the Potential of Auger Electron Radiopharmaceutical Therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2023;64:1344–1351. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.122.265039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil S., Van de Voorde M., Zhang C., Ooms M., Benard F., Radchenko V., Yang H.. A simple and automated method for Tb purification and ICP-MS analysis of Tb. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2022;7:31. doi: 10.1186/s41181-022-00183-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen C., Steyn G. F., Szelecsényi F., Kovács Z., Suzuki K., Nagatsu K., Fukumura T., Hohn A., van der Walt T. N.. Cross sections of proton-induced reactions on natGd with special emphasis on the production possibilities of 152Tb and 155Tb. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B. 2012;275:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nimb.2011.12.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dellepiane G., Casolaro P., Favaretto C., Grundler P. V., Mateu I., Scampoli P., Talip Z., van der Meulen N. P., Braccini S.. Cross section measurement of terbium radioisotopes for an optimized 155Tb production with an 18 MeV medical PET cyclotron. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2022;184:110175. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2022.110175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning A. J., Rochman D.. Modern Nuclear Data Evaluation with the TALYS Code System. Nucl. Data Sheets. 2012;113:2841–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.nds.2012.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C. ; Medin, S. ; Adair, J. ; Demopoulos, B. ; Eneli, E. ; Kuelbs, C. ; Lee, J. ; Sheppard, T. J. ; Şinar, D. ; Thurston, Z. ; Xu, M. ; Zhang, K. ; Barstow, B. . Constraints on Lanthanide Separation by Selective Biosorption bioRxiv 2023. 10.1101/2023.10.18.562985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ellis R. J., Brigham D. M., Delmau L., Ivanov A. S., Williams N. J., Vo M. N., Reinhart B., Moyer B. A., Bryantsev V. S.. “Straining” to Separate the Rare Earths: How the Lanthanide Contraction Impacts Chelation by Diglycolamide Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2017;56:1152–1160. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria L., Cruz A., Carretas J. M., Monteiro B., Galinha C., Gomes S. S., Araújo M. F., Paiva I., Marçalo J., Leal J. P.. Improving the selective extraction of lanthanides by using functionalised ionic liquids. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020;237:116354. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2019.116354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Protsak I., Stockhausen M., Brewer A., Owton M., Hofmann T., Kleitz F.. Advancing Selective Extraction: A Novel Approach for Scandium, Thorium, and Uranium Ion Capture. Small Sci. 2024 doi: 10.1002/smsc.202400171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F., Zhang T. A., Dreisinger D., Doyle F.. A critical review on solvent extraction of rare earths from aqueous solutions. Miner. Eng. 2014;56:10–28. doi: 10.1016/j.mineng.2013.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nash K. L.. The Chemistry of TALSPEAK: A Review of the Science. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2015;33:1–55. doi: 10.1080/07366299.2014.985912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahadi A., Partoazar A., Abedi-Khorasgani M. H., Shetab-Boushehri S. V.. Comparison of liquid-liquid extraction-thin layer chromatography with solid-phase extraction-high-performance thin layer chromatography in detection of urinary morphine. J. Biomed. Res. 2011;25:362–367. doi: 10.1016/S1674-8301(11)60048-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy M. E. I., El-Nouby M. A. M., Kimani P. K., Lim L. W., Rabea E. I.. A review of the modern principles and applications of solid-phase extraction techniques in chromatographic analysis. Anal. Sci. 2022;38:1457–1487. doi: 10.1007/s44211-022-00190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitseva N. G., Dmitriev S. N., Maslov O. D., Molokanova L. G., Starodub G. Y., Shishkin S. V., Shishkina T. V., Beyer G. J.. Terbium-149 for nuclear medicine. The production of 149Tb via heavy ions induced nuclear reactions. Czech. J. Phys. 2003;53:A455–A458. doi: 10.1007/s10582-003-0058-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer G. J., Čomor J. J., Daković M., Soloviev D., Tamburella C., Hagebø E., Allan B., Dmitriev S. N., Zaitseva N. G., Collaboration I.. Production routes of the alpha emitting 149Tb for medical application. Radiochim. Acta. 2002;90:247–252. doi: 10.1524/ract.2002.90.5_2002.247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moiseeva A. N., Favaretto C., Talip Z., Grundler P. V., Van Der Meulen N. P.. Terbium sisters: current development status and upscaling opportunities. Front. Nucl. Med. 2024;4:1472500. doi: 10.3389/fnume.2024.1472500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arman M. Ö., Mullaliu A., Geboes B., Van Hecke K., Das G., Aquilanti G., Binnemans K., Cardinaels T.. Separation of terbium as a first step towards high purity terbium-161 for medical applications††Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. RSC Adv. 2024;14:19926–19934. doi: 10.1039/d4ra02694b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holiski C. K., Payne R., Wang M.-J., Sjoden G. E., Mastren T.. Adsorption of terbium (III) on DGA and LN resins: Thermodynamics, isotherms, and kinetics. J. Chromatogr. A. 2024;1732:465211. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2024.465211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happel, S. TrisKem Infos No 20 2025.

- Pyles J. M., Massicano A. V. F., Appiah J.-P., Bartels J. L., Alford A., Lapi S. E.. Production of 52Mn using a semi-automated module. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2021;174:109741. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2021.109741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyles J. M., Omweri J. M., Lapi S. E.. Natural and enriched Cr target development for production of Manganese-52. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:1167. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-27257-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaja V., Cawthray J., Geyer C. R., Fonge H.. Production and Semi-Automated Processing of (89)Zr Using a Commercially Available TRASIS MiniAiO Module. Molecules. 2020;25:2626. doi: 10.3390/molecules25112626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaretto C., Talip Z., Borgna F., Grundler P. V., Dellepiane G., Sommerhalder A., Zhang H., Schibli R., Braccini S., Müller C., van der Meulen N. P.. Cyclotron production and radiochemical purification of terbium-155 for SPECT imaging. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2021;6:37. doi: 10.1186/s41181-021-00153-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha D., Vithya J., Vijayalakshmi S., Chand M., Kumar R.. Radiochemical quality control of the radiopharmaceutical, 89SrCl2 produced in FBTR. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2023;192:110566. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2022.110566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available throughout the manuscript.