Abstract

Background

Gliomas, the most aggressive primary tumors in the central nervous system, are characterized by high morphological heterogeneity and diffusely infiltrating boundaries. Such complexity poses significant challenges for accurate segmentation in clinical practice. Although deep learning methods have shown promising results, they often struggle to achieve a satisfactory trade-off among precise boundary delineation, robust multi-scale feature representation, and computational efficiency, particularly when processing high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data. Therefore, the aim of this study is to develop a novel 3D segmentation framework that specifically addresses these challenges, thereby improving clinical utility in brain tumor analysis. To accomplish this, we propose a multi-level channel-spatial attention and light-weight scale-fusion network (MCSLF-Net), which integrates a multi-level channel-spatial attention mechanism (MCSAM) and a light-weight scale-fusion module. By strategically enhancing subtle boundary features while maintaining a compact network design, our approach seeks to achieve high accuracy in delineating complex glioma morphologies, reduce computational burden, and provide a more clinically feasible segmentation solution.

Methods

We propose MCSLF-Net, a network integrating two key components: (I) MCSAM: by strategically inserting a 3D channel-spatial attention module at critical semantic layers, the network progressively emphasizes subtle, infiltrative edges and small, easily overlooked contours. This avoids reliance on an additional edge detection branch while enabling fine-grained localization in ambiguous transitional regions. (II) Light-weight scale fusion unit (LSFU): leveraging depth-wise separable convolutions combined with multi-scale atrous (dilated) convolutions, LSFU enhances computational efficiency and adapts to varying feature requirements at different network depths. In doing so, it effectively captures small infiltrative lesions as well as extensive tumor areas. By coupling these two modules, MCSLF-Net balances global contextual information with local fine-grained features, simultaneously reducing the computational burden typically associated with 3D medical image segmentation.

Results

Extensive experiments on the BraTS 2019, BraTS 2020, and BraTS 2021 datasets validated the effectiveness of our approach. On BraTS 2021, MCSLF-Net achieved a mean Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) of 0.8974 and a mean 95th percentile Hausdorff distance (HD95) of 2.52 mm. Notably, it excels in segmenting intricate transitional areas, including the enhancing tumor (ET) region and the tumor core (TC), thereby demonstrating superior boundary delineation and multi-scale feature fusion capabilities relative to existing methods.

Conclusions

These findings underscore the clinical potential of deploying multi-level channel-spatial attention and light-weight multi-scale fusion strategies in high-precision 3D glioma segmentation. By striking an optimal balance among boundary accuracy, multi-scale feature capture, and computational efficiency, the proposed MCSLF-Net offers a practical framework for further advancements in automated brain tumor analysis and can be extended to a range of 3D medical image segmentation tasks.

Keywords: Brain tumor segmentation, multi-level attention mechanism, light-weight scale fusion, transformer-based network

Introduction

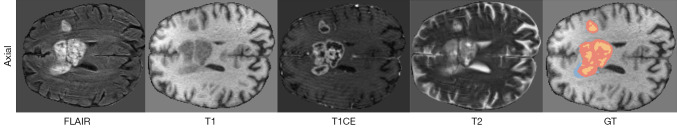

Gliomas are among the most prevalent and aggressive primary tumors of the central nervous system, leading to a high mortality rate each year. In particular, high-grade gliomas (HGGs) are characterized by complex morphologies, ill-defined boundaries, and a high likelihood of increasing intracranial pressure, posing a serious threat to patient survival (1). In the context of brain tumor diagnosis, accurate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based segmentation of brain tumors (gliomas) plays a pivotal role in both diagnostic processes and treatment planning. By acquiring multiple complementary MRI sequences—including T1-weighted, T2-weighted, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1CE), and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences—MRI can provide a comprehensive depiction of the tumor’s anatomical structures and pathological features, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the axial views of brain MRI in FLAIR, T1, T1CE, and T2 modalities, along with the GT annotations. In the GT mask, the WT is the union of the orange, red, and blue regions; the TC is the union of the red and blue regions; and the ET core corresponds to the orange region. ET, enhancing tumor; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; GT, ground-truth; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; T1, T1-weighted; T1CE, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted; T2, T2-weighted; TC, tumor core; WT, whole tumor.

To formulate precise surgical and radiotherapy strategies, boundary accuracy in tumor segmentation is of critical importance for clinical evaluation (2,3). However, manual delineation by experts is time-consuming and often suffers from inconsistent labeling (4,5), thereby catalyzing a surge of interest in automated brain tumor segmentation research. With the rapid development of deep learning for medical image analysis, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), vision transformer-based models, and hybrid CNN-transformer frameworks have each attained substantial progress. Nonetheless, three major challenges remain: (I) improving boundary segmentation accuracy; (II) achieving efficient multi-scale feature fusion; and (III) addressing the computational burden imposed by high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) data (6,7).

First, glioma boundaries often exhibit invasive penetration and gradual transitions. If an attention mechanism is introduced only once in the encoder or decoder [e.g., Attention U-Net (8), HDC-Net (9)] or the model relies solely on the global modeling capabilities of transformers [e.g., TransUNet (10), TransBTS (11)], it may fail to consistently emphasize local boundaries across multiple hierarchical levels, resulting in the neglect of subtle contour variations. Although a previous study has attempted adding edge-detection branches or specialized loss functions, these approaches typically require extra annotations or major network modifications, limiting their application to real-world 3D data scenarios (12). Second, effective multi-scale feature fusion is essential for jointly handling small lesions and expansive tumor regions (13,14). Tumors may occupy merely a few voxels or extend across large areas of the brain, thus demanding a segmentation network capable of capturing both fine-grained local details and broader global context. However, methods such as Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) or multi-branch convolutions [e.g., DeepLab (15), CPFNet (16), CANet (17)] frequently cause a surge in parameters and floating point operations per second (FLOPs) in 3D settings, while simpler skip connections [e.g., basic 3D U-Net (18) or VNet (19)] offer no explicit multi-scale refinement, leading to limited flexibility in capturing lesions of various sizes (20). Finally, due to the typically high resolution of 3D MRI, the computational cost of 3D CNNs and transformers escalates significantly. Many existing techniques employ multi-head self-attention (MHA) or multi-path modules for global context modeling and multi-scale feature capture, resulting in high computational load and memory usage, which poses difficulties in meeting real-time or resource-constrained requirements in clinical practice (21-24). Although some recent multimodal transformer networks [e.g., AMTNet (20)] and 3D lesion detection algorithms (25,26) offer new pathways for automated segmentation, they still struggle to balance boundary complexity and large lesion coverage.

Motivated by these challenges, we propose a multi-level channel-spatial attention and light-weight scale-fusion network (MCSLF-Net), comprising two key components: the multi-level channel-spatial attention mechanism (MCSAM) and the light-weight scale fusion unit (LSFU). In MCSAM, we strategically integrate 3D convolutional block attention module (CBAM) (27) at three crucial network stages—at the end of the encoder, during feature reorganization, and immediately before decoder output—repeatedly highlighting potential tumor boundaries through both channel-wise and spatial attention, without requiring an additional edge-detection branch. In LSFU, by parallelizing dilated convolutions with multiple dilation rates and employing depth-wise separable convolutions, we achieve a light-weight multi-scale fusion that preserves fine recognition for small lesions while encompassing broad contextual information, all while substantially reducing the computational overhead of 3D convolutions. Because MCSAM and LSFU respectively address “enhanced boundary accuracy” and “multi-scale fusion with computational efficiency”, MCSLF-Net can effectively capture local boundary delineation and maintain global semantic coherence in high-resolution datasets such as BraTS. Experimental results show that our approach significantly improves boundary localization metrics [e.g., 95th percentile Hausdorff distance (HD95)], multi-region segmentation accuracy, and inference efficiency, corroborating the effectiveness and practicality of multi-level attention deployment and single-module multi-scale fusion strategies for 3D glioma segmentation.

In summary, the main innovations of this work include:

MCSAM: we propose a multi-level attention enhancement strategy by embedding a 3D channel-spatial attention module into key stages of the encoder (end stage), feature reorganization phase, and decoder output. In contrast to methods that employ a single-level attention or rely solely on global transformer modeling, this repeated embedding strategy continuously accentuates potentially overlooked small or ambiguous boundaries throughout various network depths, while eliminating the need for an additional edge-detection branch.

LSFU: to accommodate fine-grained depiction of both small-scale lesions and large tumors under comprehensive contextual awareness, we design LSFU. By exploiting depth-wise separable convolutions, it markedly improves the computational efficiency of 3D feature extraction. Integrating multi-scale atrous convolutions further expands the receptive field, enabling effective feature representation for both infiltrative micro-lesions and extensive tumor areas. LSFU adopts a tiered architecture across the network depths: shallow layers maintain structural integrity to faithfully capture local morphological details, whereas deeper layers simplify the structure to extract and consolidate high-level semantic representations. By this means, LSFU achieves robust multi-scale feature fusion while notably curbing computational complexity, thus retaining the precision necessary for detecting small lesions and offering comprehensive coverage for broad tumor regions.

Comprehensive evaluation on BraTS datasets: we conduct systematic experiments on three brain tumor segmentation datasets—BraTS 2019, BraTS 2020, and BraTS 2021. MCSLF-Net achieves superior boundary localization and overlap metrics for whole tumor (WT), tumor core (TC), and enhancing tumor (ET) regions, exhibiting particularly strong performance in complex transitional zones such as the ET-TC interface and the tumor periphery. These results attest to the effectiveness of MCSAM and LSFU in strengthening feature representation and refining boundary delineation. Moreover, by creatively incorporating depth-wise separable convolutions and progressive atrous convolution, the proposed network substantially reduces computational cost while delivering satisfactory results in segmentation accuracy, boundary localization, and inference speed. Such findings underscore the advantages of the proposed multi-level feature enhancement and scale-fusion strategies.

Having outlined the core challenges and our proposed framework, we next review prior literature to situate our approach in the broader context of brain tumor segmentation. In the following subsections, we examine existing methods across three key domains—multi-level attention mechanisms for boundary optimization, multi-scale feature representation and fusion, and light-weight 3D network design—each of which informs our proposed MCSLF-Net:

Multi-level attention mechanisms and boundary optimization: in 3D MRI-based brain tumor segmentation, recent investigations commonly incorporate multi-level attention modules into the network architecture to accurately capture tumor boundaries and emphasize target regions. For instance, A4-Unet (28) inserts attention modules at multiple stages, including the encoder, bottleneck, decoder, and skip connections, thereby enforcing “focused” feature enhancement of the tumor region at different depths, and striking a balance between global context and local details. Compared to approaches that inject attention only once or rely solely on global transformers, this repeated embedding technique can more effectively strengthen irregular and fuzzy tumor boundaries across multiple hierarchical levels. Meanwhile, several studies introduce explicit boundary information to further improve segmentation granularity. For example, Edge U-Net (29) employs a parallel edge-detection branch, enabling interactions between boundary features and semantic features learned by the main network. Zhu et al. (30) propose fusing deep semantic and boundary features, using low-level boundary cues to refine high-level tumor predictions, which substantially enhances accuracy in complex boundary regions. These works collectively demonstrate the importance of combining multi-level attention with boundary optimization to suppress background interference and accentuate fine lesion borders. Building on these insights, some research has gone on to develop boundary attention gates (BAG) or additional boundary loss functions for more refined contour depiction. Khaled et al. (31), for instance, embed BAG into a transformer-based segmentation model, steering the network’s attention toward obscure boundary zones and significantly improving segmentation accuracy for blurred margins. Avazov et al. (32) introduce a light-weight 3D U-Net variant with dynamic boundary focus and spatial attention that delivers accurate results even for irregularly shaped or low-contrast lesions, boosting Dice scores while reducing Hausdorff distance. Similarly, several works incorporate boundary loss directly into the objective function—e.g., in the MUNet framework (33), combining Dice/intersection over union (IoU) loss with boundary loss yields higher overlap and boundary accuracy. Nevertheless, many of these strategies require extra edge-detection branches or explicit boundary modules, leading to more complex network designs. They may also exhibit “insufficient hierarchical coverage” or focus on a “single scale” of attention (34). Consequently, subtle boundary areas can remain underemphasized if the network is not repeatedly guided at multiple layers, potentially causing boundary discontinuities or fragmented segmentations. Conversely, focusing exclusively on boundaries may compromise the acquisition of global semantic context, especially in larger tumors. Likewise, D2PAM (35) introduces a dual-patch attention scheme—albeit for epileptic seizure prediction rather than tumor segmentation—that highlights localized patches via adversarial training, showing how attention can capture small but critical abnormal regions across different scales. In a similar vein, XAI-RACapsNet (36) employs relevance-aware attention within a capsule network for breast cancer detection, demonstrating the benefit of explicit attention modules in both localization and interpretability, which can also be adapted to boundary-aware segmentations. To overcome these limitations, we introduce the MCSAM, which repeatedly embeds 3D channel-spatial attention at key junctures—namely, the end of the encoder, during feature reorganization, and prior to the decoder output. By emphasizing latent tumor boundaries at progressively deeper layers of the network, MCSAM effectively balances local detail preservation with global contextual understanding, all without relying on a standalone edge-detection branch.

Multi-scale feature representation and fusion: acquiring and fusing multi-scale features serves as a vital strategy for addressing heterogeneous tumor morphologies and varied sizes. Transformer-based or hybrid encoders have demonstrated considerable promise in capturing long-range dependencies and multi-scale context. For example, Swin-Unet (37) integrates Swin transformer into a U-Net structure, leveraging hierarchical window-based attention to aggregate semantic information at multiple scales. DBTrans (38) adopts a dual-branch transformer encoder—one branch focuses on local window attention, while the other captures global context via cross-window attention—and aligns multi-resolution features in the decoder. Wu et al. (39) also propose a hierarchical feature learning framework for infrared salient object detection, exhibiting high efficiency and accuracy in multi-scale representation and fusion, which holds valuable insights for efficient multi-scale feature modeling in tumor segmentation. Recent studies increasingly integrate attention mechanisms into multi-scale representation to capture both global and local semantics. Zhang et al. introduce HMNet (40), which uses a dual-pathway approach: one branch preserves high-resolution detail, while the other provides low-resolution context, and a feature exchange mechanism fuses information across scales. Similarly, in DMRA U-Net, Zhang et al. (41) combine dilated convolutions with multi-scale residual blocks, complemented by channel attention in the decoder, thereby retaining both fine lesion details and overall tumor contours. DBTrans (38) likewise adopts dual-branch local window attention and global cross attention to address complex boundary regions and broad contextual dependencies. These methods highlight how multi-scale fusion strategies, which incorporate both global and local representations, facilitate robust modeling of the diverse sizes and shapes of brain tumors. Nonetheless, ensuring computational efficiency remains a persistent challenge (42,43). Further, many existing approaches lack light-weight solutions for handling “large tumor volumes” vs. “tiny infiltrative lesions” at different network depths, often requiring substantial expansion of network architecture or channel capacity. A related line of research in multi-modal and multi-transformer setups includes Dual-3DM3AD (44), which fuses MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) scans via a transformer-based segmentation and multi-scale feature aggregation to improve early Alzheimer’s classification, and Tri-M2MT (45), which integrates T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) images for neonatal encephalopathy detection using multiple transformer modules. Both approaches underscore the necessity of capturing cross-scale, cross-modality representations—concepts that likewise inform our multi-scale design for glioma segmentation. To address this, we introduce a LSFU, combining 3D depth-wise separable convolutions with dilated convolution. On the one hand, convolution factorization reduces parameters and computational costs; on the other, multi-scale dilated convolutions expand receptive fields while retaining continuous context, thus enhancing global context extraction. Hence, small or large lesions can both receive adequate feature representation under limited computational budgets.

Light-weight 3D network design: given the high resolution of 3D MRI data, researchers continue to explore methods that balance model accuracy with computational efficiency. BTIS-Net (46) employs 3D depth-wise separable convolutions to streamline the network architecture, reducing memory usage considerably while preserving segmentation accuracy—a clear advantage in scenarios demanding real-time performance or constrained hardware environments. Enhanced by hierarchical feature fusion (EHFF) (47) leverages a hierarchical feature fusion approach and a minimal decoder to fully exploit multi-level semantic information while significantly cutting down parameter counts. Along similar lines, Avazov et al. (32) present a light-weight U-Net variant that utilizes channel pruning and limited spatial attention modules, achieving further model size reduction without sacrificing accuracy. Wu et al. propose SDS-Net (48), which uses depth-wise separable convolutions and 3D shuffle attention to significantly lower the parameter count, achieving 92.7% Dice for WT segmentation in BraTS 2020—comparable to larger models. Shen et al. (49) introduce MBDRes-U-Net, incorporating multi-branch residual modules and group convolutions, thereby attaining performance rivaling mainstream architectures while using only a quarter of the parameters of a standard 3D U-Net. Despite these efforts toward overall structural simplification, fine-grained boundary delineation and multi-scale feature interaction often remain underexplored (7,50). In highly variable tumor contexts such as glioma, excessive channel pruning or omission of critical scale-specific information risks losing boundary details and leading to blurred segmentations. Consequently, our LSFU integrates light-weight convolution with multi-scale dilated feature extraction and aligns synergistically with the multi-level attention strategy of MCSAM. This design achieves a compact yet effective architecture that provides high-fidelity boundary representations from global to local scales, thereby enabling more precise 3D segmentation. We present this article in accordance with the CLEAR reporting checklist (available at https://qims.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/qims-2025-354/rc).

Methods

Overview of network architecture

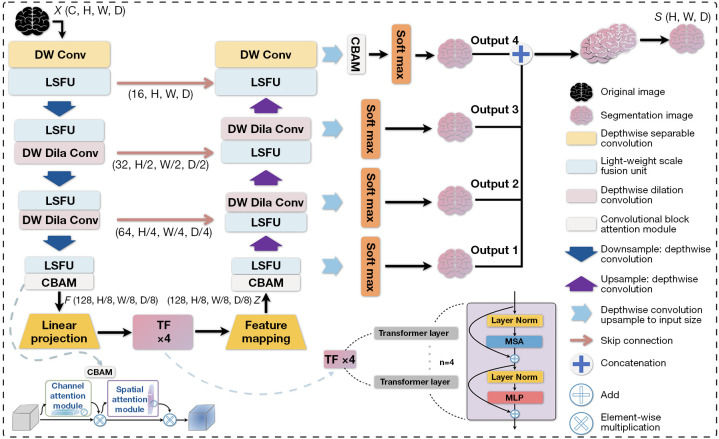

The proposed MCSLF-Net is an end-to-end deep learning framework for 3D brain tumor MRI segmentation. Its core lies in the design of a multi-level channel-spatial attention-enhanced feature extraction mechanism and a LSFU. As shown in Figure 2, this network combines multi-level attention mechanisms and multi-scale feature extraction to achieve accurate segmentation of 3D brain tumor medical images. The network takes multimodal 3D MRI data as input, where C is the number of input modalities, H and W denote the image height and width, and D is the depth of the slices. Overall, the architecture includes three main parts: a feature extraction network, a transformer-based feature reorganization module, and a multi-scale decoder. During feature extraction, the network first employs a feature embedding layer to map the input data into an initial feature space, and subsequently uses a series of feature extraction modules to progressively capture multi-scale feature representations. Let the output feature dimension of the i-th feature extraction module be , where denotes the level of the feature extraction module; while the channel dimension gradually expands to . Each feature extraction module incorporates the LSFU, which utilizes depth-wise separable convolutions and multi-scale dilated convolutions. These modules adopt a tiered structural design across different network layers to achieve efficient feature extraction and fusion. To optimize computational efficiency, the encoder employs two key light-weight strategies: first, it factorizes standard 3D convolutions into depth-wise and pointwise convolutions, significantly reducing the number of parameters; second, it adopts convolutions with varying dilation rates at different depths, thereby enlarging the receptive field without sacrificing computational efficiency. Next, to further enhance feature representation, the proposed MCSAM strategically deploys improved 3D CBAM modules at three crucial network stages. This allows multi-level adaptive enhancement of the features: the end of the feature extraction network strengthens global feature representation, the multi-scale feature reorganization stage improves fusion features, and right before the final classification output emphasizes crucial regions. The extracted features are then fed into an improved transformer encoder. During the linear projection stage, the network maps the feature map through a 3×3×3 convolution and reorganizes it into a sequence , where . It subsequently remaps the output sequence from the transformer back to a feature map and dynamically fuses multi-scale features via LSFU. In our implementation, this transformer-based feature reorganization module uses a learnable positional encoding P to preserve volumetric position information within the token sequence. Concretely, once the feature map has been reshaped into a sequence (as described above), we add P elementwise to form the initial embedding:

Figure 2.

Overall architecture of MCSLF-Net. Dashed arrows indicate internal components in the network architecture. X denotes the input 3D volume and S denotes the final segmentation output. 3D, three-dimensional; CBAM, convolutional block attention module; DW Conv, depth-wise separable convolution; DW Dila Conv, depth-wise dilation convolution; LSFU, light-weight scale fusion unit; MCSLF-Net, multi-level channel-spatial attention and light-weight scale-fusion network; MLP, multi-layer perceptron; MSA, multi-head self-attention; TF, transformer.

| [1] |

As illustrated in Figure 2, this transformer is configured with L=4 stacked layers, each containing MHA and a feed-forward network (FFN) in a residual manner:

| [2] |

where indexes the transformer layers. Specifically, each self-attention block adopts 8 attention heads, splitting the embedding dimension (512 in our setting) evenly across heads. The internal hidden dimension of the feed-forward module is set to 4,096, with Gaussian error linear unit (GELU) activation and a dropout rate of 0.1. We employ a layer normalization before both MHA and FFN (often referred to as a “pre-norm” approach) and apply a residual connection around each sub-layer, consistent with Eq. [2]. This design captures long-range dependencies among the volumetric tokens without discarding local context, as the features have already incorporated 3D spatial details through the encoder’s depth-wise separable convolutions. Our transformer thus complements LSFU’s multi-scale feature learning by explicitly modeling global correlations across the N tokenized volume patches.

By directly modeling long-range correlations across the volumetric tokens, the transformer complements the local multi-scale features learned by the LSFU. Such global attention can mitigate ambiguity in challenging regions (e.g., small or distant tumor sites). Once self-attention completes, the output sequence is reshaped back to a 3D feature map—optionally passing through a light-weight 1×1×1 or 3×3×3 convolution to align channel dimensions—and then fed into our multi-scale decoder. This brief feature mapping step ensures dimensional consistency, enabling a smooth transition to the progressive up-sampling and fusion modules described below. In the decoding phase, the network employs a progressive up-sampling strategy in multiple decoder modules to gradually recover the spatial resolution. Let the feature map at the i-th decoder module be denoted as ; each decoder module involves feature up-sampling and multi-scale feature fusion (LSFU). The up-sampling layers in these decoder modules utilize depth-wise separable convolution combined with 1×1×1 pointwise convolution to efficiently restore feature resolution. The network also incorporates skip connections and a deep supervision mechanism, providing supervision at different resolution layers to optimize feature learning. Ultimately, a Softmax layer is used to output the segmentation map. While ensuring segmentation accuracy, the overall design substantially reduces computational complexity through the use of depth-wise separable convolutions and light-weight feature fusion strategies (LSFU).

MCSAM

MCSAM is a feature enhancement mechanism that first extends the CBAM attention mechanism to 3D space, making it suitable for medical image processing tasks. Subsequently, by strategically deploying enhanced attention modules at several key semantic levels within the network—such as at the terminal stage of the encoder, at the encoder-decoder interfaces, and immediately preceding the decoder output—the model achieves adaptive enhancement of multi-level features. The design of MCSAM with three attention modules is based on two considerations. First, from a visual perception perspective, the human visual system processes information hierarchically, transitioning from lower-level edges and textures to mid-level semantic representations and, ultimately, high-level abstract concepts (51-54). This three-stage perceptual model offers valuable insights for designing network structures. Second, from a network architecture perspective, there are three critical nodes for feature transformation in the encoder-decoder structure: feature extraction, feature conversion, and feature integration. Deploying attention modules at these nodes achieves optimal feature enhancement while keeping computational overhead low (27,55).

In MCSLF-Net, the three CBAM modules are situated as follows: the first module is placed at the fourth layer of the encoder, where preliminary feature extraction is complete, allowing attention to effectively filter and enhance those foundational feature patterns—such as edges and textures—crucial for target recognition (27). The second module is located at the interface between the encoder and decoder, a key feature transformation point in which feature maps, having undergone multiple down-samplings and extractions, incorporate abundant mid-level semantic information. Attention here consolidates multi-scale features, boosting representation capacity and linking local details to the global semantic domain (56). The third module sits between the decoder output and the final classification layer. Given that the decoder’s final output possesses strong semantic discriminative capabilities yet often lacks fine-grained spatial detail, introducing attention at this juncture leverages spatial attention to optimize the spatial distribution of features, markedly improving boundary localization (15,57). This progressive feature handling reflects a flow from local to global and echoes the transition from basic visual cues to abstract semantic concepts.

Although the preceding paragraphs highlight the rationale for adopting a three-stage attention strategy from both visual perception and network architecture perspectives, here we clarify why these specific locations—encoder end, feature reorganization, and decoder output—are chosen. First, placing an attention module at the end of the encoder ensures that feature maps containing mid-to-high-level semantic information can be re-emphasized, especially for subtle tumor boundaries that may have been partially overlooked during earlier encoding steps. Second, introducing attention at the feature reorganization stage (i.e., between the encoder and decoder) capitalizes on the transformer’s multi-scale token mixing; recalibrating these fused representations helps capture fine boundary details while retaining important global context. Lastly, adding attention right before the decoder output refines the near-final predictions to resolve residual ambiguities in tumor margins, thereby enhancing delineation of intricate boundaries.

From an empirical standpoint, our ablation in the “Ablation analysis” section shows that omitting any one of these three insertion points leads to suboptimal boundary accuracy, confirming that each strategically placed module contributes to overall performance gains. Moreover, while our primary design adopts three MCSAM insertions by default, we have also empirically tested single- and two-stage placements. As detailed in the “Ablation analysis” section, these partial insertions do offer minor improvements over the baseline but consistently underperform the three-stage MCSAM approach in both overlap and boundary accuracy metrics. Similar observations were reported by Roy et al. (55), who also analyzed the impact of placing channel-spatial attention modules at different network stages, reinforcing the advantage of multi-level insertions. Hence, a fully multi-level attention deployment proves crucial for capturing the heterogeneous boundaries in high-resolution 3D MRI data. In other words, a single globally applied attention or a single-stage insertion would not adequately highlight small lesion interfaces across varying semantic depths. Therefore, our design strikes a balance between computational overhead—by limiting the total number of attention modules to three—and accuracy, through multi-level edge refinement in synergy with the transformer-based architecture.

As the core component of MCSAM, CBAM adopts a sequential channel-then-spatial attention structure to adaptively refine features by focusing on both channel importance and spatial significance (see Figure 2). Given an input feature map , where B denotes batch size, C the number of channels, and D, H, W the feature map’s depth, height, and width, respectively, CBAM first infers a channel attention map and then captures position-sensitive contextual information along the spatial dimension. Specifically, the module sequentially infers a channel attention map and a spatial attention map , and subsequently enhances the feature representation via a two-stage re-calibration process—first applying channel-wise re-calibration , followed by spatial re-calibration , where represents element-wise multiplication.

In the channel attention module, we adopt a dual-path aggregation strategy, using both average pooling and max pooling to generate complementary channel descriptors (the superscript C denotes “channel”, representing the feature mapping along the channel dimension). These descriptors are processed by a shared MLP, resulting in the channel attention map:

| [3] |

where is the sigmoid activation, and are weights of the MLP layers, and r is the reduction ratio.

The spatial attention module then focuses on learning the attention distribution in 3D space by performing average pooling and max pooling along the channel axis to produce spatial descriptors (the superscript s denotes “spatial”, representing the feature mapping along the spatial dimension.), which are concatenated and processed by a 3D convolutional layer, yielding the spatial attention map:

| [4] |

where k represents the convolutional kernel size. This design effectively captures spatial contextual information while maintaining low computational complexity.

In summary, the MCSAM mechanism ingeniously integrates attention mechanisms with multi-level feature representations—spanning the encoder’s terminal layers, the bottleneck, and the decoder—by deploying enhanced 3D CBAM modules at critical nodes within the network. This design not only emulates the hierarchical perception pattern of the human visual system but also capitalizes on CBAM’s strengths in feature selection and enhancement, achieving effective feature refinement with minimal computational cost. Experiments later in this paper show that this light-weight yet efficient feature enhancement strategy significantly elevates the representational capacity of the network.

To further elucidate our MCSAM design, we specify that each 3D CBAM module in our implementation adopts a channel-attention reduction ratio of 16 by default, balancing model capacity and efficiency. We also apply a 7×7×7 convolution in the spatial submodule to capture broader 3D context, following (27). Although one could experiment with lower reduction ratios (e.g., 4 or 8) or smaller kernels (3×3×3) for different trade-offs, our current setting (ratio =16, kernel size =7) proved sufficient to highlight subtle boundary cues while minimizing parameter overhead. In terms of spatial placement, we empirically confirmed that inserting MCSAM at three stages—the end of the encoder, mid-level feature reorganization, and immediately before the final output-helped emphasize infiltrative edges at increasingly abstract semantic levels. This choice aligns with the hierarchical perception principle described earlier and ensures that our attention mechanism repeatedly revisits boundary-sensitive regions. Unlike a single global attention, this multi-level approach yields more consistent boundary delineation across heterogeneous tumor morphologies, as we show in the “Ablation analysis” section.

LSFU

In medical image segmentation, the high dimensionality and structural complexity of 3D data present formidable challenges for feature representation. Traditional CNNs often encounter multiple limitations: for instance, a small convolution kernel (e.g., 1×1×1 or 3×3×3) constrains the receptive field and hampers the capture of sufficient contextual information, while directly using large kernels can dramatically raise computational costs. Moreover, certain tumor regions—such as infiltrative lesions—are small and feature indistinct boundaries, necessitating the retention of fine-grained high-resolution features alongside deeper semantic information. Traditional multi-scale feature extraction and fusion strategies also typically demand additional computational resources, which is particularly burdensome for high-resolution 3D medical images.

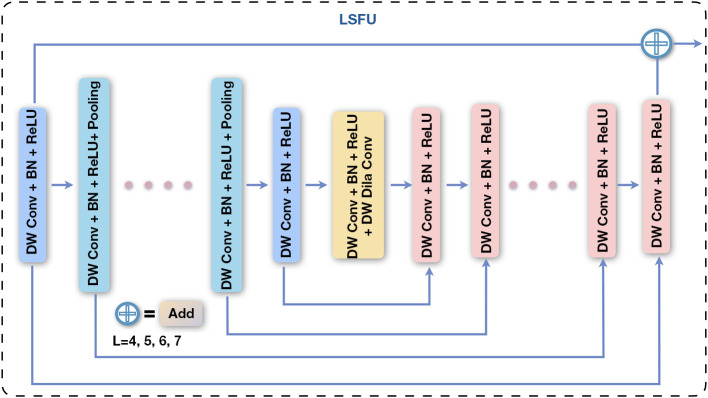

To address these challenges, we introduce the LSFU. By factorizing standard convolutions into depth-wise and pointwise convolutions, LSFU optimizes computational efficiency. It further adopts a tiered structure design: shallower layers employ a deeper encoder-decoder style to retain high-resolution detail, whereas deeper layers simplify the structure to capture semantic information. In addition, we incorporate progressive dilated convolutions to expand the receptive field and use residual connections to achieve efficient multi-scale feature fusion. This tiered feature representation and fusion strategy not only significantly reduces computational overhead but also enhances detection and segmentation capacity for targets at different scales. The overall architecture of LSFU is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The overall architecture of the LSFU module. It uses a cascaded multi-scale feature processing strategy that includes DW Conv, BN, and ReLU activation. The U-shaped structure within the module fuses features via skip connections (add), where L represents encoder-decoder depth (L=4, 5, 6, 7). BN, batch normalization; DW Conv, depth-wise separable convolution; LSFU, light-weight scale fusion unit; ReLU, rectified linear unit.

To resolve the limited receptive field, feature extraction, and computational efficiency issues, we adopt four feature processing stages (covering both encoder and decoder) in the network, each employing an LSFU for multi-scale feature learning. The output feature dimension of each stage is . The output of each stage (i.e., the LSFU) can be represented as:

| [5] |

where denotes the feature map transformed by LSFU, is the sigmoid activation. Within the LSFU, a residual structure is adopted for feature transformation, wherein the transformation component utilizes an encoder-decoder architecture. The feature transformation is defined as:

| [6] |

where is the input feature map to the i-th feature extraction module, and denotes the encoder-decoder-based transformation within LSFU. Let U denote the depth of the encoder-decoder structure (i.e., the number of internal layers in Eq. [4]), while and represent the numbers of input and output channels, respectively, and M indicates the number of channels within the internal layers. Here, L determines the feature representation capacity of U; a larger L value enables U to extract richer multi-scale features via a deeper encoder-decoder architecture. The LSFU block comprises three key components: (I) an input transformation layer that converts the input feature map into intermediate features; (II) a symmetric encoder-decoder structure with a depth of L that is used to extract and encode multi-scale contextual information; and (III) a residual connection that fuses local features with multi-scale features. Furthermore, to further reduce computational cost, the standard convolutions in the feature transformation operations and U are replaced by depth-wise separable convolutions:

| [7] |

where is a depth-wise convolution (with the number of groups equal to the input channels), and is a 1×1×1 pointwise convolution. Within different scales of feature processing, the depth of the LSFU’s internal encoder-decoder is adjusted according to the feature map resolution: the first and second stages use larger values of (e.g., ) to enhance feature representation, whereas the third and fourth stages adopt smaller (e.g., ) and incorporate dilated convolutions to compensate for the loss of receptive field caused by down-sampling. This nested design allows the LSFU to learn intra-stage multi-scale features and aggregate inter-stage multi-level features, while maintaining low computational cost. It is worth noting that the feature transformation U in LSFU incurs a relatively small overhead because during encoding, the spatial resolution of feature maps is successively reduced (for example, from 128×128×128 to 16×16×16), so even though channel dimensions increase, the overall computational cost is significantly lowered. In decoding, the progressive restoration of feature map resolution remains manageable, thanks to depth-wise separable convolutions. Although the FLOPs of U grow quadratically with the intermediate channel size M, the operations mainly occur at lower-resolution feature maps; thus, the resulting increase in computation is not substantial compared to standard convolutions and residual blocks.

While the basic structure of LSFU has been introduced, it is important to elaborate on how its specific design choices—namely the selection of dilation rates and the use of depth-wise separable convolutions—impact both accuracy and computational efficiency. In our implementation, we adopt relatively small dilation rates (e.g., 2 or 4) for the shallower layers within LSFU’s encoder-decoder blocks, where the spatial resolution remains relatively high. This strategy ensures that the receptive field is moderately expanded without incurring gridding artifacts or excessively dilated feature representations (15,58). Conversely, for deeper layers with reduced spatial dimensions, larger dilation rates (up to 8) may be employed to capture more extensive contextual information. By adjusting dilation rates progressively across these stages, LSFU strikes a balance between fine-grained local cues (essential for boundary delineation) and broader global context.

Moreover, depth-wise separable convolutions prove highly beneficial in curbing the computational burden compared to standard 3D convolutions. By factorizing each 3D convolution into a channel-wise (depth-wise) component followed by a 1×1×1 pointwise convolution, we effectively decouple the number of learnable parameters from both the spatial kernel size and the number of output channels. Empirically, our experiments indicate that LSFU can maintain strong representational capability while cutting FLOPs by approximately 30–40%, relative to equivalently scaled standard 3D convolutions. This efficiency renders the network more deployable, particularly in scenarios where hardware resources are constrained.

We further compare this strategy with other widely used multi-scale fusion methods such as ASPP and multi-branch convolutions. While ASPP [e.g., (15)] employs parallel atrous convolutions at varying rates, a prior study suggests that directly applying it in 3D can lead to higher parameter overhead, since each branch deals with high-dimensional feature maps. Similarly, multi-branch fusion [e.g., (48)] requires multiple streams and dedicated aggregation operations, which can become cumbersome in volumetric medical image segmentation. In contrast, LSFU handles multi-scale feature extraction via a streamlined encoder-decoder style within each LSFU block, mainly operating on reduced-resolution feature maps and therefore constraining its computational footprint. Our ablation studies confirm that this single-path design offers a favorable trade-off between complexity and accuracy: LSFU not only matches or outperforms established multi-scale modules on boundary-sensitive 3D segmentation metrics, but also exhibits lower memory consumption. This is especially advantageous in clinical MRI and CT applications, which often require processing full-volume, high-resolution data.

Overall, these design principles position LSFU as a robust and efficient solution for 3D medical image segmentation, where both small-scale boundary details and large-scale contextual cues play critical roles, yet computational budgets are frequently limited. By leveraging depth-wise separable convolutions and carefully calibrated dilation rates, LSFU delivers effective multi-scale representations with a moderate model size and reduced runtime overhead.

In practice, we incorporate LSFU at both encoder and decoder stages, but customize the dilation rates and channel widths per layer based on empirical trade-offs. Specifically, we vary the dilation rate within LSFU’s encoder-decoder blocks from 2 or 4 at shallower depths up to 8 in the deepest part, to balance local detail preservation and broader contextual coverage. Meanwhile, the channel width actually increases from 16 to 128 as we go deeper, ensuring sufficient capacity for high-level semantics. These tiered hyperparameter settings—partly inspired by nested U-Net-like designs (59)—help each stage capture the appropriate balance of local details vs. global context. Additionally, each LSFU combines depth-wise-separable 3D convolutions with LSFU blocks that embed small encoder-decoder substructures. Overall, these design decisions allow LSFU to handle heterogeneous tumor shapes under practical memory constraints without sacrificing boundary accuracy.

Supervision

MCSLF-Net employs a deep supervision strategy analogous to holistically-nested edge detection (HED) (60), but further incorporates progressive scale weighting to better suit medical image segmentation. Multiple supervision points are placed throughout the decoder to optimize feature extraction and fusion. Concretely, the network assigns supervision at resolution levels during decoding. These include multi-scale fusion layers , deep semantic feature layers , high-level context layers , mid-level local feature layers , and low-level detail layers . By allocating different weights to each supervision point, the network more effectively integrates multi-scale features for comprehensive optimization from high-level semantics to low-level details. The loss function adopts a weighted multi-scale Dice loss:

| [8] |

where is the scale weight, which decreases progressively from the final output layer to the initial feature layers. This design is motivated by the greater influence of deeper features on the final segmentation result, while still ensuring shallow layers receive auxiliary supervision. is the class weight for balancing the segmentation of different target regions (ET, WT, TC). denotes the number of classes. The Dice loss is defined as:

| [9] |

where represents the prediction of class at scale , v denotes the corresponding ground truth, and is a smoothing term.

By applying supervision signals at different resolution levels, this multi-scale deep supervision mechanism jointly guides feature learning: deep features ensure segmentation accuracy, shallow features preserve fine-grained details, and multi-scale feature fusion enhances overall robustness. During training, the network simultaneously optimizes outputs at all scales to learn multi-level feature representations; in the inference phase, the output of the multi-scale fusion layer serves as the final segmentation result. This progressive weighting strategy allows the network to more effectively exploit feature information across scales.

Datasets

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. This study conducts experimental evaluations on three publicly available brain tumor segmentation datasets: BraTS 2019, BraTS 2020, and BraTS 2021 (2,3,61). These datasets consist of preoperative MRI scans collected from multiple institutions, covering both glioblastomas (GBM)/HGG and lower-grade gliomas (LGG). Specifically, BraTS 2019 contains 335 training samples and 125 validation samples; BraTS 2020 has 369 training samples and 125 validation samples; and the BraTS 2021 training set includes 1,251 samples. Each case has four co-registered MRI modalities: T1-weighted, T1CE, T2-weighted, and FLAIR. All images undergo rigorous preprocessing, including registration to a common anatomical template, interpolation to a uniform resolution of 1 mm3, skull stripping, and a standardized input size of 240×240×155 voxels.

To ensure effective model training, a uniform preprocessing procedure is applied across all datasets. The MRI volumes are normalized to zero mean and unit variance, and then randomly cropped to 128×128×128 during training. Data augmentation techniques such as random flipping and rotation are also introduced to mitigate overfitting. Regarding tumor labels, the datasets’ tumor regions are subdivided into three components—ET (label 4), peritumoral edema (ED; label 2), and necrotic or non-ET (NCR/NET) core (label 1). In the evaluations, these labels are combined into three nested regions: the WT (consisting of labels 1, 2, and 4), the TC (consisting of labels 1 and 4), and the ET (label 4 only). Each volume is manually segmented by one to four annotators following a uniform labeling protocol, and the annotations are further validated by experienced neuroradiologists.

Evaluation metrics

To comprehensively assess model performance, this study uses evaluation metrics reflecting both computational efficiency and segmentation accuracy. For efficiency, gigaflops (GFLOPs) quantify inference throughput, while million parameters (MParams) indicate model size and thus feasibility for deployment in resource-constrained scenarios. In segmentation performance, two widely recognized metrics are used: Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) and HD95. DSC measures the overlap between predicted segmentation results and ground-truth labels using the formula:

| [10] |

where and respectively denote the voxel sets of the predicted mask and ground-truth labels. HD95 calculates the 95th percentile of surface distances between the prediction and the ground truth:

| [11] |

where denoting the Euclidean distance. Together, DSC gauges volumetric overlap, while HD95 provides insight into boundary accuracy.

Implementation details

All models are implemented in PyTorch and trained on two NVIDIA A100 40-GB GPUs. During data preprocessing, each of the four MRI modalities (T1-weighted, T1CE, T2-weighted, FLAIR) in each case is standardized. Specifically, z-score normalization is applied to the non-zero region of each modality, computing mean and standard deviation to transform the data to zero mean and unit variance. To enhance generalizability, various data augmentation strategies are adopted during training, such as random flipping (along each of the three axes with probability 0.5), random intensity scaling and shifting (scaling factor of 0.1), and random rotation (±10°). Training samples of size 128×128×128 are then randomly cropped from the original 240×240×155 images.

In our experiments, we adopt a multi-stage preprocessing pipeline that both standardizes the input data and diversifies the training samples. Initially, each 3D MRI scan of shape (H, W, D) is padded along the slice dimension from 155 to 160 if needed, ensuring a consistent size for subsequent cropping. We then perform zero-mean, unit-variance normalization on non-zero voxels, followed by a series of stochastic augmentations. First, we randomly sample a (128×128×128) cubic region from the original (240×240×160) volume, selecting offsets (h, w, d) uniformly from or for each dimension, and cropping accordingly, , to reduce memory usage and concentrate on localized 3D patches. Second, with probability 0.5 per axis, we flip the volume (and corresponding label) along each of the three spatial dimensions (x, y, z), thus expanding the range of anatomical orientations. Third, we rotate the volume around the in-plane axes by an angle , preserving structural integrity by restricting \theta to a moderate range. Fourth, we apply a random intensity shift to each channel c of a volumetric patch by sampling multiplicative and additive factors and updating , thereby simulating contrast variations across different scanners. Optionally, we also test a min-max rescaling to [0, 1] or re-apply zero-mean normalization for outlier-intense images, ensuring consistent normalization within each batch. After these transformations, we convert the patched data and the corresponding ground-truth label mask to tensors, maintaining alignment of all spatial operations. While these augmentations improve generalization, each can introduce biases: excessive rotation could distort subtle anatomical cues, and overly large intensity shifts might obscure clinically relevant contrasts. We mitigate such risks by restricting rotation angles to ±10° and capping intensity changes at ±10%. Likewise, random flipping across all three axes may raise concerns about orientation consistency, yet we preserve tumor location correctness by applying the same flips to the label. Finally, random cropping might exclude portions of larger tumors; we address this by drawing multiple crops per volume and allowing padding so boundary tumors remain likely to appear. Taken together, this balanced augmentation strategy increases sample diversity without substantially distorting tumor morphology or imposing systematic orientation bias.

A five-fold cross-validation approach is utilized to thoroughly evaluate the model’s performance and stability. Distributed training is performed using an initial learning rate of 0.0002, with an AdamW optimizer (weight decay =1e−5) and the AMSGrad variant enabled. The batch size is set to 4 (2 samples per GPU) for 1,000 epochs. PyTorch’s DistributedDataParallel module is employed for multi-GPU parallelism, and a linear learning rate decay policy is used. For the loss function, we adopt a weighted multi-scale Dice loss. Higher weights are assigned to the small and more challenging ET region, while different supervision signals (with progressively decreasing weighting factors of 1.0, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.2 from the final output to early feature layers) are applied at various scales, thereby facilitating more effective multi-scale feature learning. Additionally, deep supervision is used, applying supervision to feature maps at different scales to stabilize training. During inference, a sliding-window strategy is employed: the input MRI volume is partitioned into overlapping 128×128×128 blocks for prediction, and the partial results are fused to obtain the final segmentation.

Results

Quantitative results

We comprehensively validate the proposed MCSAM and LSFU on the BraTS 2019, BraTS 2020, and BraTS 2021 datasets. As shown in Tables 1-3, our method demonstrates strong overall performance in terms of both DSC and HD95. Specifically, on BraTS 2019 (Table 1), although TransBTS achieves the highest average DSC (0.8362) among all methods, our approach attains a slightly lower DSC of 0.8315 yet surpasses TransBTS in boundary accuracy by achieving the best HD95 (4.04 vs. 5.14 mm). On BraTS 2020 (Table 2), our mean DSC further increases to 0.8408, surpassing TransUNet and TransBTS by 2.44% and 0.67%, respectively, while also attaining the best average HD95 of 3.62 mm. On the most recent BraTS 2021 dataset (Table 3), SwinUNETR exhibits the highest average DSC of 0.9136, which is 1.81% higher than our model (0.8974); however, our method again achieves the best HD95 (2.52 vs. 5.03 mm for SwinUNETR), demonstrating superior boundary delineation and robustness. Notably, our method also shows outstanding regional segmentation capacity for the WT region, achieving DSCs of 0.8961, 0.9026, and 0.9257 on BraTS 2019, BraTS 2020, and BraTS 2021, respectively. These results underline the capacity of MCSLF-Net to maintain high overall segmentation quality—especially in boundary-sensitive metrics—while balancing computational efficiency, confirming the effectiveness of our design in handling complex 3D brain MRI segmentation tasks.

Table 1. Performance comparison on the BraTS 2019 validation set.

| Methods | DSC ↑ | HD95 (mm) ↓ | Parameter (M) ↓ | FLOPs (G) ↓ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ET | TC | Average | WT | ET | TC | Average | ||||

| 3D U-Net (18) | 0.8738 | 0.7086 | 0.7248 | 0.7691 | 9.43 | 5.06 | 8.72 | 7.74 | 16.90 | 586.71 | |

| Attention U-Net (8) | 0.8881 | 0.7596 | 0.7720 | 0.8066 | 7.76 | 5.20 | 8.23 | 7.07 | 17.12 | 588.26 | |

| An et al. (62) | 0.8866 | 0.7296 | 0.7897 | 0.8020 | 10.34 | 8.07 | 10.50 | 9.64 | 0.06 | 22.00 | |

| VNet (19) | 0.8873 | 0.7389 | 0.7656 | 0.7973 | 6.26 | 6.13 | 8.71 | 7.03 | 69.30 | 765.90 | |

| Swin-Unet (37) | 0.8938 | 0.7849 | 0.7875 | 0.8221 | 7.51 | 6.93 | 9.26 | 7.90 | 27.15 | 250.88 | |

| HDC-Net (9) | 0.8930 | 0.7760 | 0.8310 | 0.8333 | 7.51 | 3.51 | 7.46 | 6.16 | 0.29 | 25.82 | |

| TransUNet (10) | 0.8948 | 0.7817 | 0.7891 | 0.8219 | 6.67 | 4.83 | 7.37 | 6.29 | 105.18 | 1,205.76 | |

| TransBTS (11) | 0.9000† | 0.7893† | 0.8194 | 0.8362† | 5.64 | 3.74 | 6.05 | 5.14 | 30.61 | 263.82 | |

| Ours (MCSLF-Net) | 0.8961 | 0.7539 | 0.8445† | 0.8315 | 3.81† | 4.11† | 4.20† | 4.04† | 24.49 | 142.43 | |

The table presents each method’s performance in terms of DSC and HD95, as well as the model’s parameter count and computational complexity. For MCSLF-Net (Ours), all reported DSC and HD95 values represent the mean results from our five-fold cross-validation. The up arrow (↑) indicates that the metric increases, whereas the down arrow (↓) indicates that the metric decreases. The best results are marked by a symbol (†). 3D, three-dimensional; DSC, Dice similarity coefficient; ET, enhancing tumor; FLOPs, floating point operations per second; HD95, 95th percentile Hausdorff distance; MCSLF-Net, multi-level channel-spatial attention and light-weight scale-fusion network; TC, tumor core; WT, whole tumor.

Table 2. Performance comparison on the BraTS 2020 validation set.

| Methods | DSC ↑ | HD95 (mm) ↓ | Parameter (M) ↓ | FLOPs (G) ↓ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ET | TC | Average | WT | ET | TC | Average | ||||

| 3D U-Net (18) | 0.8411 | 0.6876 | 0.7906 | 0.7731 | 13.37 | 50.98 | 13.61 | 25.99 | 16.90 | 586.71 | |

| VNet (19) | 0.8611 | 0.6897 | 0.7790 | 0.7766 | 20.41 | 47.70 | 12.18 | 26.76 | 69.30 | 765.90 | |

| An et al. (62) | 0.8878 | 0.7208 | 0.7939 | 0.8008 | 11.69 | 34.14 | 13.76 | 19.86 | 0.06 | 22.00 | |

| Swin-Unet (37) | 0.8934 | 0.7895† | 0.7760 | 0.8196 | 7.86 | 11.01 | 14.59 | 11.15 | 27.15 | 250.88 | |

| HDC-Net (9) | 0.8940 | 0.7720 | 0.8250 | 0.8303 | 6.73 | 27.42 | 9.13 | 14.43 | 0.29 | 25.82 | |

| TransUNet (10) | 0.8946 | 0.7842 | 0.7837 | 0.8208 | 5.97 | 12.85 | 12.84 | 10.55 | 105.18 | 1,205.76 | |

| TransBTS (11) | 0.9009 | 0.7873 | 0.8173 | 0.8352 | 4.96 | 17.95 | 9.77 | 10.89 | 30.61 | 263.82 | |

| Ours (MCSLF-Net) | 0.9026† | 0.7726 | 0.8473† | 0.8408† | 3.25† | 3.86† | 3.76† | 3.62† | 24.49 | 142.43 | |

The table presents each method’s performance in terms of DSC and HD95, as well as the model’s parameter count and computational complexity. For MCSLF-Net (Ours), all reported DSC and HD95 values represent the mean results from our five-fold cross-validation. The up arrow (↑) indicates that the metric increases, whereas the down arrow (↓) indicates that the metric decreases. The best results are marked by a symbol (†). 3D, three-dimensional; DSC, Dice similarity coefficient; ET, enhancing tumor; FLOPs, floating point operations per second; HD95, 95th percentile Hausdorff distance; MCSLF-Net, multi-level channel-spatial attention and light-weight scale-fusion network; TC, tumor core; WT, whole tumor.

Table 3. Performance comparison on the BraTS 2021 validation set.

| Methods | DSC ↑ | HD95 (mm) ↓ | Parameter (M) ↓ | FLOPs (G) ↓ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ET | TC | Average | WT | ET | TC | Average | ||||

| U-Net3D (5) | 0.9269 | 0.8410 | 0.8710 | 0.8793 | 8.04 | 4.90 | 6.32 | 6.42 | 19.24 | 2,382.10 | |

| TransVW (63) | 0.9232 | 0.8209 | 0.9021 | 0.8821 | 9.89 | 8.02 | 7.07 | 8.33 | 19.13 | 2,381.30 | |

| VNet (19) | 0.9138 | 0.8690 | 0.8901 | 0.8909 | 9.81 | 10.99 | 8.69 | 9.83 | 69.30 | 765.90 | |

| UNETR (64) | 0.9253 | 0.8759 | 0.9078 | 0.9031 | 8.97 | 4.22 | 5.19 | 6.13 | 102.37 | 203.21 | |

| SwinUNETR (65) | 0.9332† | 0.8908† | 0.9169† | 0.9136† | 4.64 | 4.65 | 5.81 | 5.03 | 61.99 | 793.92 | |

| VIT3D (66) | 0.5386 | 0.4116 | 0.6489 | 0.5331 | 31.51 | 28.24 | 27.26 | 29.01 | 183.01 | 93.78 | |

| VitAutoEnc (67) | 0.8141 | 0.6835 | 0.7866 | 0.7614 | 19.36 | 16.23 | 18.19 | 17.93 | 183.41 | 125.66 | |

| TransUNet (10) | 0.8768 | 0.8334 | 0.8275 | 0.8459 | 12.32 | 8.04 | 9.71 | 10.02 | 105.18 | 1,205.76 | |

| TransBTS (11) | 0.9105 | 0.8675 | 0.8976 | 0.8918 | 8.54 | 5.12 | 6.50 | 6.72 | 30.61 | 263.82 | |

| Ours (MCSLF-Net) | 0.9257 | 0.8621 | 0.9045 | 0.8974 | 2.78† | 2.44† | 2.33† | 2.52† | 24.49 | 142.43 | |

The table presents each method’s performance in terms of DSC and HD95, as well as the model’s parameter count and computational complexity. For MCSLF-Net (Ours), all reported DSC and HD95 values represent the mean results from our five-fold cross-validation. The up arrow (↑) indicates that the metric increases, whereas the down arrow (↓) indicates that the metric decreases. The best results are marked by a symbol (†). 3D, three-dimensional; DSC, Dice similarity coefficient; ET, enhancing tumor; FLOPs, floating point operations per second; HD95, 95th percentile Hausdorff distance; MCSLF-Net, multi-level channel-spatial attention and light-weight scale-fusion network; TC, tumor core; WT, whole tumor.

Our model also shows considerable advantages in boundary localization. On BraTS 2019, the mean HD95 drops to 4.04 mm, indicating reductions of 21.4% and 35.8% relative to TransBTS and TransUNet, respectively. On BraTS 2020, the mean HD95 further drops to 3.62 mm—a relative reduction of 66.8% and 65.7% against TransBTS and TransUNet, respectively. On BraTS 2021, we achieve the best average HD95 of 2.52 mm, an improvement of 62.5% and 74.9% over TransBTS and TransUNet, respectively.

Regarding the trade-off between computational efficiency and performance, our approach achieves notable optimization through its innovative design. It contains only 24.49 M parameters, which is 76.7% lower than TransUNet (105.18 M), 20.0% lower than TransBTS (30.61 M), and 64.7% lower than VNet (69.30 M). For FLOPs, our model needs just 142.43 G, an 88.2% reduction compared to TransUNet (1,205.76 G), 46.0% lower than TransBTS (263.82 G), and 81.4% lower than VNet (765.90 G), as shown in Table 2. This considerable boost in efficiency is primarily attributable to our set of innovations, including depth-wise separable convolutions and a light-weight scale-fusion module (LSFU) integrated with progressive dilation, which jointly expand the receptive field in a computationally efficient manner. Compared to other methods such as U-Net3D (2,382.10 G) (5), UNETR (203.21 G), SwinUNETR (793.92 G), and VitAutoEnc (125.66 G), our approach substantially reduces computation while maintaining competitive performance.

On the BraTS 2020 dataset, we performed a two-tailed Wilcoxon significance test on both Dice score and HD95, comparing our proposed MCSLF-Net with four representative models [3D U-Net (18), VNet, SwinUNETR, and TransBTS]. As shown in Table 4, the resulting P values demonstrate that MCSLF-Net consistently yields statistically significant improvements (P<0.05), thereby confirming the effectiveness of our approach.

Table 4. Two-tailed Wilcoxon significance test P values (for DSC and HD95) on the BraTS 2020 dataset, comparing the proposed method with four state-of-the-art models (3D U-Net, VNet, SwinUNETR, and TransBTS).

| Methods | P value (DSC) | P value (HD95) |

|---|---|---|

| 3D U-Net (18) | 1.80e−06 | 2.50e−07 |

| VNet (19) | 6.20e−05 | 9.10e−06 |

| SwinUNETR (65) | 0.023 | 0.03 |

| TransBTS (11) | 0.032 | 0.049 |

3D, three-dimensional; DSC, Dice similarity coefficient; HD95, 95th percentile Hausdorff distance.

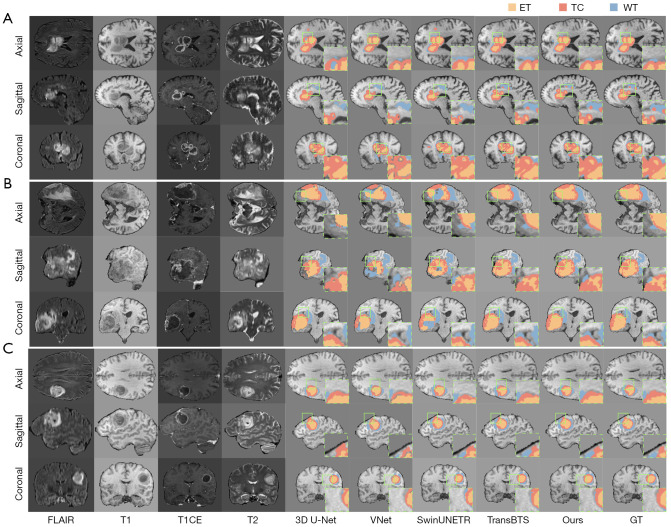

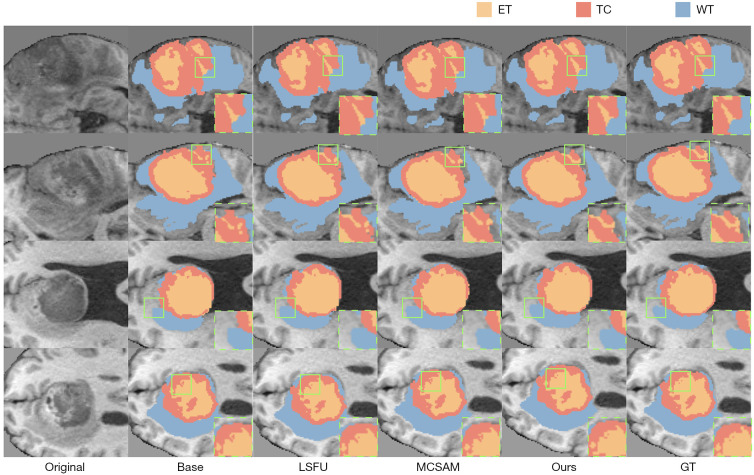

Qualitative results

Figure 4 presents visual comparisons of segmentation results for three representative cases from the BraTS 2020 dataset, each displayed in axial, sagittal, and coronal views. From left to right, we show the raw images of four MRI modalities (FLAIR, T1-weighted, T1CE, T2-weighted) followed by the segmentation results from 3D U-Net (18), VNet, SwinUNETR, TransBTS, our method, and the ground-truth annotations (GT). ET regions appear in orange, TC in red, and WT in blue.

Figure 4.

Visualization of segmentation outcomes for three representative cases from the BraTS 2020 dataset. Each row, from left to right, displays the original FLAIR, T1, T1CE, and T2 MRI modalities, followed by the segmentation results from 3D U-Net, VNet, SwinUNETR, TransBTS, and the method proposed in this paper (Ours), with the final column showing the GT labels. The orange region denotes the ET, the red region indicates the TC, and the blue region represents the WT. (A) A tumor exhibiting multiple subregions in the right hemisphere; (B) a large-volume lesion in the left hemisphere; (C) a small yet anatomically complex tumor located in the anterior portion of the right hemisphere. All cases are shown across the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. Green bounding boxes mark representative boundary areas or small lesion details that are especially challenging to segment, illustrating where each model may misclassify or omit subtle structures. 3D, three-dimensional; ET, enhancing tumor; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; GT, ground-truth; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; T1, T1-weighted; T1CE, contrast-enhanced T1-weighted; T2, T2-weighted; TC, tumor core; WT, whole tumor.

In Figure 4A, the tumor has a typical multi-component structure in the right lateral region (axial view). Our method achieves more accurate delineation of the ET region’s irregular contour and preserves the integrity of the TC region, closely matching the ground truth. The WT boundary is also captured more precisely compared to other methods. Figure 4B shows a large-volume tumor in the left lateral region (axial view). Our approach exhibits obvious advantages in capturing ET-TC boundaries, offering more precise discrimination between the enhancing portion and the TC. This is especially evident in the sagittal view, where our method reduces the confusion commonly seen in other segmentations. Figure 4C illustrates a relatively small yet structurally complex tumor in the right frontal region (axial view). Here, our method excels in identifying the small ET region, accurately capturing details of the enhancing lesion. Across all three views, our model demonstrates stronger boundary consistency, particularly evident in transitional areas where it surpasses competing methods.

Overall, our method displays superior segmentation performance in tumors with different volumes, locations, and morphological characteristics. These improvements stem chiefly from the multi-level deployments of 3D CBAM in MCSAM, which bolster feature representations from local textures to high-level semantics, and from LSFU, which uses an encoder-decoder structure and residual connections for efficient multi-scale feature fusion. The use of depth-wise separable convolutions and progressive dilation further curtails computational cost.

Ablation analysis

To systematically assess the contributions of MCSAM and LSFU, we perform detailed ablation studies on BraTS 2020 (Table 5). Our baseline is a transformer-based U-shaped hybrid network, achieving DSCs of 0.8863 (WT), 0.7416 (ET), 0.8009 (TC)—for an average of 0.8096—and HD95 values of 3.81 mm (WT), 4.91 mm (ET), and 4.55 mm (TC), with a mean of 4.42 mm. Adding MCSAM markedly improves performance, elevating DSCs for WT/ET/TC to 0.8956/0.7610/0.8028 and boosting the mean DSC to 0.8198 (+1.26%). The mean HD95 also decreases to 4.08 mm (−7.7%), achieved with only a minor cost increase of 0.01 M parameters (23.19 M total) and 1.45 G FLOPs (119.54 G total). Introducing LSFU similarly yields gains: WT/ET/TC DSCs of 0.8946/0.7501/0.8343 and a mean DSC of 0.8264 (+2.08% over baseline), with HD95s of 3.51, 4.12, and 4.41 mm, reducing the mean to 4.01 mm (−9.3%). This improvement adds 0.29 M parameters (23.47 M total) and 5.79 G FLOPs (123.88 G total).

Table 5. Ablation results on the BraTS 2020 dataset.

| Methods | DSC | HD95 (mm) | Parameter (M) ↑ | FLOPs (G) ↑ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ET | TC | Average | WT | ET | TC | Average | ||||

| Base | 0.8863 | 0.7416 | 0.8009 | 0.8096 | 3.81 | 4.91 | 4.55 | 4.42 | 23.18 | 118.09 | |

| Base + Enc-only | 0.8880 | 0.7450 | 0.8010 | 0.8113 | 3.70 | 4.85 | 4.50 | 4.35 | 23.18 | 118.09 | |

| Base + Bottleneck-only | 0.8880 | 0.7480 | 0.8020 | 0.8127 | 3.72 | 4.68 | 4.42 | 4.27 | 23.18 | 118.09 | |

| Base + Dec-only | 0.8890 | 0.7570 | 0.8000 | 0.8153 | 3.63 | 4.58 | 4.45 | 4.22 | 23.18 | 118.09 | |

| Base + Enc + Dec | 0.8945 | 0.7585 | 0.8025 | 0.8185 | 3.57 | 4.75 | 4.28 | 4.20 | 23.18 | 119.53 | |

| Base + MCSAM | 0.8956 | 0.7610 | 0.8028 | 0.8198 | 3.50 | 4.70 | 4.03 | 4.08 | 23.19 | 119.54 | |

| Base + LSFU | 0.8946 | 0.7501 | 0.8343 | 0.8264 | 3.51 | 4.12 | 4.41 | 4.01 | 23.47 | 123.88 | |

| Ours without transformer | 0.8960 | 0.7605 | 0.8340 | 0.8302 | 3.60 | 4.40 | 4.05 | 4.02 | 1.79 | 52.19 | |

| Ours (MCSLF-Net) | 0.9026† | 0.7726† | 0.8473† | 0.8408† | 3.25† | 3.86† | 3.76† | 3.62† | 24.49 | 142.43 | |

The table presents the performance of the baseline model (Base), the baseline model with selective MCSAM insertions (Base + Enc-only, Base + Bottleneck-only, Base + Dec-only, Base + Enc + Dec), the baseline model augmented with the MCSAM (Base + MCSAM), the baseline model incorporating the LSFU (Base + LSFU), the complete model (Ours), and an additional configuration removing the transformer from the baseline (Ours without transformer). Performance is reported in terms of DSC and HD95, as well as their parameter counts and computational complexity. The up arrow (↑) indicates that the metric increases. The best results are marked by a symbol (†). Dec, decoder output; DSC, Dice similarity coefficient; Enc, encoder end; ET, enhancing tumor; FLOPs, floating point operations per second; HD95, 95th percentile Hausdorff distance; LSFU, light-weight scale fusion unit; MCSAM, multi-level channel-spatial attention mechanism; MCSLF-Net, multi-level channel-spatial attention and light-weight scale-fusion network; TC, tumor core; WT, whole tumor.

To further clarify how MCSAM at different network stages influences segmentation quality, we also explore four additional variants: Base + Enc-only, Base + Bottleneck-only, Base + Dec-only, and Base + Enc + Dec, where the 3D CBAM is inserted at a single location (encoder end, bottleneck, or decoder output) or at both encoder and decoder ends. As shown in Table 5, all four new configurations yield minor-to-moderate improvements over the baseline (Base), consistent with each stage’s unique role. Specifically, inserting MCSAM only at the encoder end (Enc-only) slightly refines high-level semantic cues for large lesions (WT) but struggles with small or fuzzy boundaries (ET). Bottleneck-only instead capitalizes on mid-level feature reorganization for more balanced gains across WT and ET, yet still lacks final boundary enhancements. Conversely, Dec-only especially benefits small or ambiguous ET regions (ET =0.7570), highlighting the decoder’s capacity for precise boundary recalibration. Notably, combining Enc + Dec yields superior performance (DSC =0.8185 on average) compared to single-stage setups, underscoring the synergy between deep-level feature extraction and final-stage boundary refinement. Nevertheless, all these partial insertions still trail the three-stage MCSAM integration (Base + MCSAM) in both DSC and HD95, confirming that repeated attention guidance remains key for robust multi-scale feature capture. Although we include these four new variants to reveal distinct stage-level effects, for brevity we only visualize the representative configurations—Base, Base + LSFU, Base + MCSAM, and Ours—in Figure 5. Hence, single- or double-stage insertions do not appear in the figure-based comparisons but further reinforce our conclusion that multi-level attention is crucial for precise tumor delineation across varying lesion sizes.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the ablation experiment results on the BraTS 2020 dataset. All slices are axial T1-weighted views. From left to right, the figure shows the original image (Original), the baseline model’s segmentation output (Base), segmentation after integrating the LSFU module (LSFU), segmentation with the MCSAM mechanism (MCSAM), the final model’s segmentation (Ours), and the GT. In the displayed color scheme, orange denotes the ET, red represents the TC, and blue depicts the WT. Green bounding boxes mark representative boundary areas or small lesion details that are especially challenging to segment, illustrating where each model may misclassify or omit subtle structures. Four distinct slices are presented, illustrating how each module incrementally improves segmentation performance. ET, enhancing tumor; GT, ground-truth; LSFU, light-weight scale fusion unit; MCSAM, multi-level channel-spatial attention mechanism; TC, tumor core; WT, whole tumor.

Next, we examine how each of our proposed modules—MCSAM, LSFU, and the transformer—affects individual tumor regions (WT, TC, and ET), we analyze the DSC gains and HD95 reductions per component, referencing Table 5. When solely adding MCSAM to the baseline (Base + MCSAM), we observe that ET DSC increases from 0.7416 to 0.7610, while WT and TC improve from 0.8863 to 0.8956 and 0.8009 to 0.8028, respectively. This suggests that multi-level channel-spatial attention is particularly beneficial for the small and often ambiguous ET region, where repeated boundary emphasis helps resolve subtle margins. By contrast, introducing only LSFU (Base + LSFU) raises TC DSC more substantially—from 0.8009 to 0.8343—indicating that the light-weight multi-scale fusion is especially effective at capturing the varied spatial extents of the TC region. Although LSFU also improves WT (0.8863 to 0.8946) and ET (0.7416 to 0.7501), its most pronounced contribution appears in refining TC boundaries, likely due to deeper-scale receptive field expansions at reduced computational costs.

We also investigate the impact of removing the transformer module from the baseline to test whether MCSAM and LSFU retain their synergy without global self-attention. As shown in Table 5 (Ours without transformer), MCSAM + LSFU alone yields WT/ET/TC DSC scores of 0.8960, 0.7605, and 0.8340, surpassing either MCSAM or LSFU individually and achieving an average DSC of 0.8302 with a mean HD95 of 4.02 mm. However, once the transformer is reintroduced (Ours), the DSC scores climb further to 0.9026 (WT), 0.7726 (ET), and 0.8473 (TC), accompanied by noticeably lower HD95 values for all three regions. These improvements indicate that global self-attention complements the localized boundary cues provided by MCSAM and the scale-aware fusion offered by LSFU, altogether yielding more consistent delineation of WT, TC, and ET. Hence, the ablation results isolate each component’s specific benefits—the fine-tuned boundary awareness from MCSAM, the enhanced feature integration from LSFU, and the broader contextual modeling by the transformer—and demonstrate their cumulative effect when unified in MCSLF-Net. Although we only visualize the four main configurations in Figure 5 for clarity, the other ablation variants (single/double-stage or no transformer) also align with these trends, as evidenced by their numerical improvements in Table 5.

Ultimately, the combined MCSAM + LSFU approach attains the highest performance: average DSC increases to 0.8408 (+3.85%) while HD95 drops to 3.62 mm (−18.1%). Although the final model requires 24.49 M parameters and 142.43 G FLOPs, the substantial performance gain renders this computational overhead acceptable.

Figure 5 visually compares four representative slices. The Base captures most of the tumor region but yields prominent errors in boundary placement, especially in WT (blue) boundaries and ET (orange). Incorporating LSFU refines boundary continuity, particularly in the second and third slices. MCSAM further boosts detail recognition, notably at the ET-TC boundary in the first and fourth slices. The final model (Ours) integrates both modules, producing results closest to the ground-truth annotations across all slices and effectively capturing transitional boundaries in multi-region lesions.

Discussion

Analysis of performance gains