Abstract

Background and aims:

Oral nicotine pouches (ONPs) contain varying proportions of freebase nicotine (FBN), with higher FBN expected to increase nicotine delivery across the oral mucosa. Because ONPs contain fewer toxicants than moist snuff and may serve as a reduced harm alternative for smokeless tobacco, we compared how the FBN in ONPs affects both nicotine pharmacokinetics and craving relief relative to moist snuff.

Design:

Three-visit (90-minute sessions; ≥48-hour washout), single-blind, randomized crossover study. Participants were asked to complete all visits within 1 month.

Setting:

Clinical facility in Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Participants:

N = 62 moist snuff users (Mage = 41 years, 96.8% male, 91.9% white, 33.9% had tried ONPs before), recruited through social media advertisements and participants’ word-of-mouth from rural and Appalachian Ohio.

Intervention:

Following ≥12 hours of nicotine abstinence, participants used either a (1) low FBN peppermint ONP (27.4% FBN; 5.1 mg nicotine/pouch; Rogue brand), (2) high FBN peppermint ONP (70.2% FBN; 5.0 mg nicotine/pouch; Zyn brand) or (3) 2 g of usual brand moist snuff for 30 minutes. Participants completed the three study visits in one of six randomized orders.

Measurements:

Plasma nicotine and self-reported craving were assessed at t = baseline, 5, 15, 30, 60 and 90 minutes. Plasma nicotine and craving relief at t = 30 minutes were primary and secondary outcomes, respectively.

Findings:

At t = 30 minutes, mean [standard deviation (SD)] plasma nicotine concentrations were 7.1 (2.8) ng/mL for low FBN ONP, 14.8 (6.4) ng/mL for high FBN ONP and 12.3 (8.4) ng/mL for moist snuff (all comparison Ps ≤ 0.001). Craving was lower for moist snuff (mean = 0.8) than either ONP (means = 1.4), with the low FBN ONP providing statistically significantly less craving relief than moist snuff (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

The proportion of freebase nicotine in oral nicotine pouches appears to statistically significantly influence their nicotine delivery, with higher freebase nicotine oral nicotine pouches delivering more nicotine than usual brand moist snuff. However, craving appears to be higher when using oral nicotine pouches than usual brand moist snuff.

Keywords: abuse liability, health disparities, nicotine, oral nicotine pouches, rural, smokeless tobacco

INTRODUCTION

In 2021, 5.2 million adults in the United States (US) used smokeless tobacco (SLT), including moist snuff, chewing tobacco and snus [1]. Moist snuff (i.e. ‘dip’) dominates the SLT market, representing 88.9% of sales in 2019 [2]. Although variation exists across brands, moist snuff products sold in the United States contain tobacco-specific nitrosamines [e.g. N’-Nitrosononornicotine (NNN)], metals (e.g. arsenic and cadmium), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [e.g. Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP)] and volatile aldehydes (e.g. formaldehyde) [3]. These constituents increase risk of cancer [4, 5], oral lesions [5] and gum disease and tooth loss [6] for moist snuff users. As the prevalence of SLT use in the United States varies according to geography, rural and Appalachian populations have increased risk of SLT use compared to urban and non-Appalachian populations [1, 7–9], translating to disparities in oral, pharynx and larynx cancers [10].

Oral nicotine pouches (ONPs) contain nicotine, flavorants, pH adjusters and stabilizers, but no tobacco leaf. This absence of tobacco significantly reduces their toxicant profile compared to moist snuff [11, 12], suggesting that switching from moist snuff to ONPs could plausibly reduce cancer risk. The market-leading ONPs are manufactured by major tobacco companies (e.g. Zyn is manufactured by Phillip Morris International, Rogue is manufactured by Swisher) and are, therefore, often cross-promoted with other tobacco products [13], with advertisements frequently noting positive characteristics of ONPs relative to other tobacco products (e.g. spit-free) [14]. This marketing strategy appears effective, because tobacco users—particularly those with a history of SLT use—are more likely to use ONPs than people who do not use tobacco [15–17]. The strong uptake among SLT users highlights ONPs’ potential as a harm reduction tool for this population [17, 18].

One characteristic that could affect whether moist snuff users switch to ONPs is the amount of freebase nicotine (FBN) in the ONP. The fraction of nicotine in the freebase versus salt form in an oral nicotine product affects the speed of nicotine transport across the oral mucosa [19–22], with higher fractions of FBN causing faster and greater plasma nicotine delivery [20–22]. Like moist snuff [23, 24], ONPs have a wide range of FBN fractions across, and sometimes within, brands (e.g. 6.5%–94.6%) [25]. Although FBN fraction is not included on ONP package labels, this variability in FBN fraction means that ONPs are available for consumers who seek slower, milder nicotine delivery and conversely, those who seek faster, harsher nicotine delivery. The effects of manipulating the FBN fraction of moist snuff products on plasma nicotine delivery contributed to moist snuff’s ascent to the top of the SLT market [2, 21, 22, 24, 26]. However, the effects of FBN fraction on the harm reduction potential of ONPs have not been studied.

We compared the nicotine delivery, withdrawal and craving relief, and subjective effects of moist snuff to ONPs with differing FBN fractions to determine if FBN can influence ONPs’ substitutability for moist snuff [27]. Because rural and Appalachian populations predominantly carry the disease burden from moist snuff use, we conducted our study among adults who use moist snuff in rural and Appalachian Ohio. We hypothesized that using ONPs with high (vs. low) FBN fraction would result in greater (1) plasma nicotine delivery and (2) craving and withdrawal relief, and (3) more positive subjective effects.

METHODS

Design

We conducted a three-visit, single-blind, randomized crossover human laboratory study (Figure 1). At each visit, participants used either a low FBN ONP, high FBN ONP or usual brand moist snuff for 30 minutes in a balanced randomized order. Data were collected over 90 minutes. The primary outcome variable was plasma nicotine level at 30 minutes. Visits were separated by ≥48 hours washout. When possible, participants were asked to complete all visits within 1 month.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT flow diagram for randomized crossover study, Ohio, 2023–2024. Abbreviations: FBN, freebase nicotine; ONP, oral nicotine pouch. aParticipants with t = baseline (BL) plasma nicotine concentrations >5 ng/mL at a visit were excluded from analyses for that visit only. bParticipants who had complete data and were compliant with nicotine abstinence for at least one visit were included in analyses.

Participants

Participants were adults who use moist snuff and live in an Appalachian or rural Ohio county. Appalachian status was designated by the Appalachian Regional Commission, and rurality was designated by a Rural–Urban Commuting Area Code of 10. Participant accrual occurred from May 2023 to January 2024. Recruitment methods involved targeted social media advertisements and participants’ word-of-mouth. People who were interested in the study completed an online screening questionnaire. Those who appeared eligible were called by study staff to confirm eligibility. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age 21 years or older; (2) reside in Appalachian or rural Ohio county; (3) willing to complete all study procedures, including abstaining from all tobacco, nicotine and marijuana for 12 hours before clinic visits; (4) able to read and speak English; and (5) daily use of moist snuff for at least the past 3 months. Exclusion criteria were: (1) use of tobacco or nicotine products other than moist snuff for >10 days per month; (2) any ONP use in past 3 months; (3) unstable or significant psychiatric conditions; (4) pregnant, planning to become pregnant or breastfeeding; (5) history of cardiac event or distress, including but not limited to uncontrolled high blood pressure, chest pain or shortness of breath within the past year; (6) self-reported diagnosis of lung or other disease including asthma (if uncontrolled or worse than usual), cystic fibrosis, throat cancer, tongue cancer, other oral cancer, lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; and (7) working with a cessation counselor, using cessation medication or planning to quit using moist snuff in the next 3 months.

Procedures

Participants traveled one to 3 hours to our clinic in Columbus, OH, for all three visits.

Participants capable of pregnancy took a urine pregnancy test before study product use at each visit. We confirmed nicotine and tobacco abstinence by asking participants at what time they last used a nicotine or tobacco product and by retrospectively reviewing t = baseline (BL) plasma nicotine values (details below). Data from participants with t = BL plasma nicotine concentrations >5 ng/mL were excluded from analyses for the respective visit [28].

Study product use was standardized across participants and visits. When using ONPs, participants were asked to keep the ONP in place between their upper lip and gum for 30 minutes. When using moist snuff, in addition to using a standard serving size of 2 g, participants were asked to use moist snuff in their location of typical use for 30 minutes, were permitted to spit as they usually would and rinsed their mouths to remove any remaining product following use. During the moist snuff visit, participants were additionally asked to extract a ‘typical’ amount of moist snuff (i.e. a ‘pinch’) from the container to approximate their typical serving size. The study staff weighed the pinch of moist snuff using a microbalance. Participants refrained from eating and drinking during product use, but were permitted to eat and drink after the study product was removed. Participants remained seated during the entire 90-minute observation period.

While using study products, the research nurse completed 3 mL blood draws at t = BL (immediately before study product placement), 5, 15, 30, 60 and 90 minutes via IV line placed at the beginning of the visit. Participants self-reported withdrawal and craving symptoms concurrent with each blood draw. Following study product use, participants completed measures of subjective drug effects, including product appeal, intentions for future use and study product effects. Participants received $150 at the end of each visit plus a $50 bonus for completing all three visits within 1 month. The Ohio State University’s Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures, and participants provided informed consent before completing any study activities.

Randomization and blinding

The clinical research assistant conducting the first visit, randomized participants to one of six possible visit orders using REDCap’s randomization function. Randomization was stratified by level of SLT dependence, as level of dependence might affect participants’ use topographies in response to varying FBN levels [29]. SLT dependence was categorized into two levels: dependent and not dependent (scoring below) for randomization. Randomization was single-blind, with participants being blinded to study product (except for moist snuff).

Interventions

Participants used a different study product at each visit: (1) one 6 mg nicotine concentration, peppermint, Rogue ONP (low FBN); (2) one 6 mg nicotine concentration, peppermint, Zyn ONP (high FBN); or (3) 2 g of their usual brand of moist snuff (consistent with other clinical studies) [21, 22]. ONP brands and flavors were initially selected based on a recent chemical analysis of several ONP brands that showed the Rogue and Zyn 6 mg peppermint pouches were likely to have similar total nicotine concentration, but discrepant FBN fractions [25]. We characterized nicotine content, FBN fraction and percent moisture of the ONPs using the federal register method [30, 31] (details are provided in the Supporting information). The study ONPs had similar nicotine concentration (Rogue: 5.1 mg/pouch, Zyn: 5.0 mg/pouch). The Zyn ONP had a FBN fraction that was 2.6 times as high as Rogue. The Zyn ONP also had less moisture, translating to a lighter mass (Table S1). Hereafter, the Zyn and Rogue ONPs will be referred to as High FBN ONP and Low FBN ONP, respectively.

Measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was plasma nicotine concentration at t = 30 minutes.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcome measures included (1) nicotine pharmacokinetics, including plasma nicotine at t = 5, 15, 60 and 90 minutes, maximum plasma nicotine concentration (Cmax), time to maximum nicotine concentration (Tmax) and total nicotine delivery from 0 to 90 minutes (area under the curve [AUC0–90]); (2) withdrawal symptoms measured by the Minnesota Withdrawal Scale (MNWS) at t = 5 to 90 minutes (response options: 0 = ‘none’ to 4 = ‘severe’) [32]; (3) craving measured by the MNWS at t = 5 to 90 minutes [32]; (4) craving measured by the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges brief form (QSU-Brief; desire and relief subscales analyzed separately; 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘strongly agree’) at t = 5 to 90 minutes [33]; and (5) measures of subjective drug effects, including pleasantness to use again, desire/urge to use again, need to use for relief and wanting to use (0=‘not at all’ to 100 = ‘very’) [34]; extent of liking, enjoyment, pleasurableness and satisfaction (0 = ‘not at all’ to 100 = ‘very’) [34]; interest and willingness to use again (0 = ‘not at all’ to 10 = ‘very’) [34]; satisfaction, reward, sensation, craving and aversion measured via the modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire (0 = ‘not at all’ to 6 = ‘extremely’) [35–37]; and feeling any effects, good effects, and bad effects from the Drug Effects Questionnaire (0 = ‘not at all’ to 100 = ‘extremely’) [37]. Subjective effects were measured on a visual analog scale.

Independent variables

The predictor variable was the study product: low FBN ONP, high FBN ONP and moist snuff. Variables that characterized the sample included age, sex and gender, race and ethnicity and highest level of education. Variables describing moist snuff use included usual pinch mass, frequency of using moist snuff each day, usual brand and flavor of moist snuff and SLT dependence measured via the Severson 7-Item Smokeless Tobacco Dependence Scale, a valid and reliable measure of SLT dependence [total score and categorized as dependent (total score >9) vs. not dependent] [38]. Variables describing history of ONP use included ever use of ONPs and prior use of ONPs fairly regularly.

Statistical analysis

Sample size

We powered our sample to detect differences in plasma nicotine concentration at t = 30 minutes using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Using estimates from other research [39], we assumed that participants’ mean t = 30 plasma nicotine concentration would be 16.9 ng/mL for moist snuff, 14.7 ng/mL for the high FBN ONP and 10.0 ng/mL for the low FBN ONP. We assumed a within-subjects correlation of 0.5 and a SD of 7.65 ng/mL [39]. With a planned sample size of 60 completers, we estimated having >95% power to detect a difference in the main effect of study product on maximum nicotine concentration with an α level of 0.05.

General statistical methods

We calculated descriptive statistics to characterize the sample. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, means and SDs were calculated for continuous variables, and medians and inter-quartile ranges (IQRs) were calculated for variables that were highly skewed (e.g. pinch mass and frequency of using moist snuff each day). Distributions of dependent variables were inspected and log-transformed (e.g. plasma nicotine, QSU relief subscale, MNWS total score and bad effects from study product) or dichotomized in cases of extreme skewness (e.g. aversiveness) before analysis. Period and order effects were investigated by comparing study product specific means across both visits and randomization order with ANOVA. Participants with complete data and t = BL plasma nicotine values ≤5 ng/mL for at least one visit were included in analyses as likelihood-based mixed effects models yield valid inference under missing at random assumptions (Figure 1), yielding an analytic sample of n = 62. Whereas the analytic sample size was n = 62, we note that the analytic sample size for each study product ranged from n = 50 to n = 53 because of attrition over the course of the study, blood draw failures and visit order being randomized.

Primary outcome

We compared plasma nicotine concentration at t = 30 minutes between the low FBN ONP, high FBN ONP and moist snuff using a linear mixed effects model. The model included random participant intercepts and fixed effects for study product, blood draw time (t = 5, 15, 30, 60, 90), plasma nicotine at t = BL and period (visit = 1, 2, 3), as well as the interaction between blood draw time and study product. We conducted an F test to compare plasma nicotine concentration at t = 30 across the three study products. Pairwise comparisons were conducted when the overall test comparing the three study products was significant. We used Holm’s procedure to adjust the alpha for multiple comparisons.

Secondary outcomes

We compared (1) plasma nicotine at t = 5, 15, 60 and 90 minutes; (2) Cmax, Tmax and AUC0–90; (3) withdrawal symptoms at t = 5 to 90 minutes; (4) craving measured via the MNWS at t = 5 to 90 minutes; and (5) craving measured via the QSU-Brief’s desire and relief subscales at t = 5 to 90 minutes using procedures described above for the primary outcome, with the exception of controlling for the respective t = BL measure of withdrawal or craving rather than t = BL plasma nicotine for withdrawal and craving models.

We compared most measures of subjective drug effects using linear mixed effects models; however, because of skewness, the aversion outcome was dichotomized and, therefore, analyzed using a logistic mixed effects regression model. Models included fixed effects for study product and period (visit = 1, 2, 3) and random participant intercepts. We first conducted an F test to identify differences across study products. If the P-value for the F test was <0.05, we conducted three pairwise comparisons with Holm’s adjustment of alphas.

Sensitivity analyses

The primary and secondary analyses described above were repeated incorporating all participants, including those previously excluded for having a baseline nicotine concentration greater than 5. Baseline nicotine concentration was added as an additional covariate in each of these models.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Of the n = 71 participants who were randomized, n = 70 completed at least one visit, and n = 62 met nicotine abstinence requirements for at least one visit and were included in analyses (Figure 1). Participants were 41.0 (SD = 13.2) years old on average (Table 1). Nearly all participants were male, white race, non-Hispanic ethnicity and had not obtained a Bachelor’s degree. Participants’ median pinch mass was 3.36 g (IQR = 2.42–5.11 g). The median frequency of moist snuff use each day was 5 (IQR = 4–10) times. Tobacco-flavored moist snuff was the most common flavor used, followed by wintergreen and mint. Over half of participants screened as dependent on SLT. One-third of participants had ever tried ONPs before, and 6.5% of participants had a history of using ONPs fairly regularly (but not in the past 3 months).

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics, rural and Appalachian Ohio, 2023–2024.a

| n = 62b | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (mean, SD) | 41.0 (13.2) |

| Sex assigned at birth (n, %) | |

| Female | 2 (3.2) |

| Male | 60 (96.8) |

| Gender (n, %) | |

| Woman | 2 (3.2) |

| Man | 60 (96.8) |

| Race (n, %) | |

| White | 57(91.9) |

| Black or African American | 1 (1.6) |

| Asian | 1 (1.6) |

| More than one race | 2 (3.2) |

| Refused | 1 (1.6) |

| Ethnicity (n, %) | |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 0 (0.0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino/a | 60 (96.8) |

| Refused | 2 (3.2) |

| Highest level of education (n, %) | |

| <High school | 1 (1.6) |

| Graduated high school | 22 (35.5) |

| Currently attending college | 3 (4.8) |

| Some college but no degree | 14 (22.6) |

| Associate’s degree | 10 (16.1) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 12 (19.4) |

| Usual pinch mass (g) | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.15 (2.59) |

| Median (IQR) | 3.36 (2.42, 5.11) |

| Usual dips/day | |

| Mean (SD) | 10.3 (17.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (4, 10) |

| Usual moist snuff flavor (n, %) | |

| Tobacco/unflavored | 24 (42.1) |

| Wintergreen | 22 (38.6) |

| Mint | 8 (14.0) |

| Fruit/other | 3 (5.3) |

| Usual brand of moist snuff (n, %) | |

| Copenhagen | 27 (43.5) |

| Grizzly | 9 (14.5) |

| Skoal | 10 (16.1) |

| Longhorn | 8(12.9) |

| More than 1 brand | 2 (3.2) |

| Other | 3 (4.8) |

| Missing | 3 (4.8) |

| SLT dependence (total score) (mean, SD) | 9.4 (3.9) |

| SLT dependence level (n, %) | |

| Dependent on SLT | 36 (58.1) |

| Not dependent on SLT | 26 (41.9) |

| Ever used ONPs (n, %) | |

| Yes | 21 (33.9) |

| No | 40 (64.5) |

| Do not know | 1 (1.6) |

| Ever used ONPs fairly regularly (n, %) | |

| Yes | 4(6.5) |

| No | 58 (93.5) |

| Random order assignments (n, %)c | |

| 1. Low FBN ONP, 2. High FBN ONP, 3. Moist snuff | 10 (16.1) |

| 1. Low FBN ONP, 2. Moist snuff, 3. High FBN ONP | 12 (19.4) |

| 1. High FBN ONP, 2. Low FBN ONP, 3. Moist snuff | 10 (16.1) |

| 1. High FBN ONP, 2. Moist snuff, 3. Low FBN ONP | 10 (16.1) |

| 1. Moist snuff, 2. Low FBN ONP, 3. High FBN ONP | 10 (16.1) |

| 1. Moist snuff, 2. High FBN ONP, 2. Low FBN ONP | 10 (16.1) |

Abbreviations: FBN, freebase nicotine; ONP, oral nicotine pouch; SLT, smokeless tobacco.

Participants were healthy adults who use moist snuff and live in a rural or Appalachian Ohio county. Data collection occurred in Columbus, OH.

Participants completed a single-blind, randomized crossover experiment in which they used 1 ONP with a low fraction of FBN, 1 ONP with a high fraction of FBN and (unblinded) 2 g of their usual brand of loose moist snuff for 30 minutes in three separate visits.

Participant counts might not sum to the total sample size because of missing data.

Assessment of period and order effects

The only outcome exhibiting period or order effects was Tmax, with period (P = 0.04) and order (P = 0.04) effects being present for the low FBN ONP and moist snuff (P = 0.02 and P = 0.03, respectively). Because we included period as a fixed effect in models and randomization was counterbalanced, however, we expect these period and order effects did not contribute substantially to the results.

Primary outcome: plasma nicotine concentration at t = 30 minutes

Following 30 minutes of use, mean (SD) plasma nicotine concentration was 7.1 (2.8) ng/mL for the low FBN ONP, 14.8 (6.4) ng/mL for the high FBN ONP and 12.3 (8.4) ng/mL for moist snuff (Table 2; Figure 2). Mean plasma nicotine concentration at t = 30 minutes differed across the three products (P < 0.001), including between the low FBN ONP and moist snuff (P < 0.001), the high FBN ONP and moist snuff (P = 0.001), and the low and high FBN ONPs (P < 0.001).

TABLE 2.

Plasma nicotine delivery during use of oral nicotine pouches with varied fractions of freebase nicotine versus moist snuff in a sample of healthy adults who use moist snuff, rural and Appalachian Ohio, 2023–2024.a

| Low FBN ONP n = 50b Mean (SD) |

High FBN ONP n = 51b Mean (SD) |

Moist snuff n = 51b Mean (SD) |

Comparison across products P-value |

Low FBN ONP vs. moist snuff P-valuec |

High FBN ONP vs. moist snuff P-valuec |

Low FBN ONP vs. high FBN ONP P-valuec |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Primary outcome | |||||||

| Plasma nicotine at 30 min (ng/mL)d | 7.1 (2.8) | 14.8 (6.4) | 12.3 (8.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||

| Plasma nicotine (ng/mL)d | |||||||

| 5 min | 2.5 (1.5) | 5.7 (4.5) | 5.3 (6.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| 15 min | 4.8 (2.2) | 11.2 (5.9) | 10.0 (9.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| 60 min | 6.2 (2.5) | 11.1 (4.6) | 11.1 (6.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.50 | <0.001 |

| 90 min | 5.2 (2.6) | 8.8 (3.8) | 9.2 (5.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.99 | <0.001 |

| Plasma nicotine Cmax (ng/mL)d | 7.5 (2.9) | 15.1 (6.3) | 13.7 (9.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Plasma nicotine Tmax (min)d | 41.7 (18.5) | 35.6 (14.7) | 41.2 (18.5) | 0.11 | – | – | – |

| Plasma nicotine AUC0–90 (ng/mL)d | 506.8 (188.2) | 997.5 (390.7) | 919.4 (585.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; Cmax, maximum plasma nicotine concentration; FBN, freebase nicotine; ONP, oral nicotine pouch; Tmax, time to maximum nicotine concentration.

n = 62 participants were recruited from rural and Appalachian Ohio counties to complete a three-visit, single-blind, randomized cross-over experiment. Study ONPs were 6 mg nicotine concentration and peppermint flavor. The low FBN ONP was Rogue brand, and the high FBN ONP was Zyn brand.

Participant counts do not sum to the total analytic sample size (n = 62) because of study attrition and visit-level exclusions from the analytic sample due to noncompliance with nicotine abstinence or blood draw failures.

Statistical significance following Holm’s procedure is denoted using bold.

Variable was log-transformed for analyses. Untransformed means and SDs are reported in this table.

FIGURE 2.

Plasma nicotine concentrations during 30-minute use of one low freebase nicotine (FBN) oral nicotine pouch (ONP), one high FBN ONP and 2 g of moist snuff. Abbreviations: FBN, freebase nicotine; ONP, oral nicotine pouch. aStatistically significant difference between low FBN ONP and high FBN ONP (P < 0.001).bStatistically significant difference between low FBN ONP and moist snuff (P < 0.001).cStatistically significant difference between high FBN ONP and moist snuff (P = 0.009).

Secondary outcomes

Plasma nicotine concentration

Mean plasma nicotine concentrations at t = 5, 15, 60 and 90 minutes differed across the study products (P < 0.001) (Table 2; Figure 2). Differences in mean plasma nicotine concentrations were driven by reduced plasma nicotine concentration from the low FBN ONP versus the high FBN ONP and moist snuff (P < 0.001). Mean plasma nicotine concentrations at t = 5, 15, 60 and 90 minutes did not differ between the high FBN ONP and moist snuff. Cmax differed across study products (P < 0.001), with Cmax for the low FBN ONP approximately half as high as for the high FBN ONP and moist snuff (P < 0.001). AUC0–90 also differed across study products (P < 0.001), with the low FBN ONP delivering approximately half as much nicotine overall as the high FBN ONP and moist snuff (P < 0.001). Tmax did not differ across the study products.

Withdrawal symptoms

We observed no differences in withdrawal symptoms across study products from t = 5 to 90 minutes (Table 2).

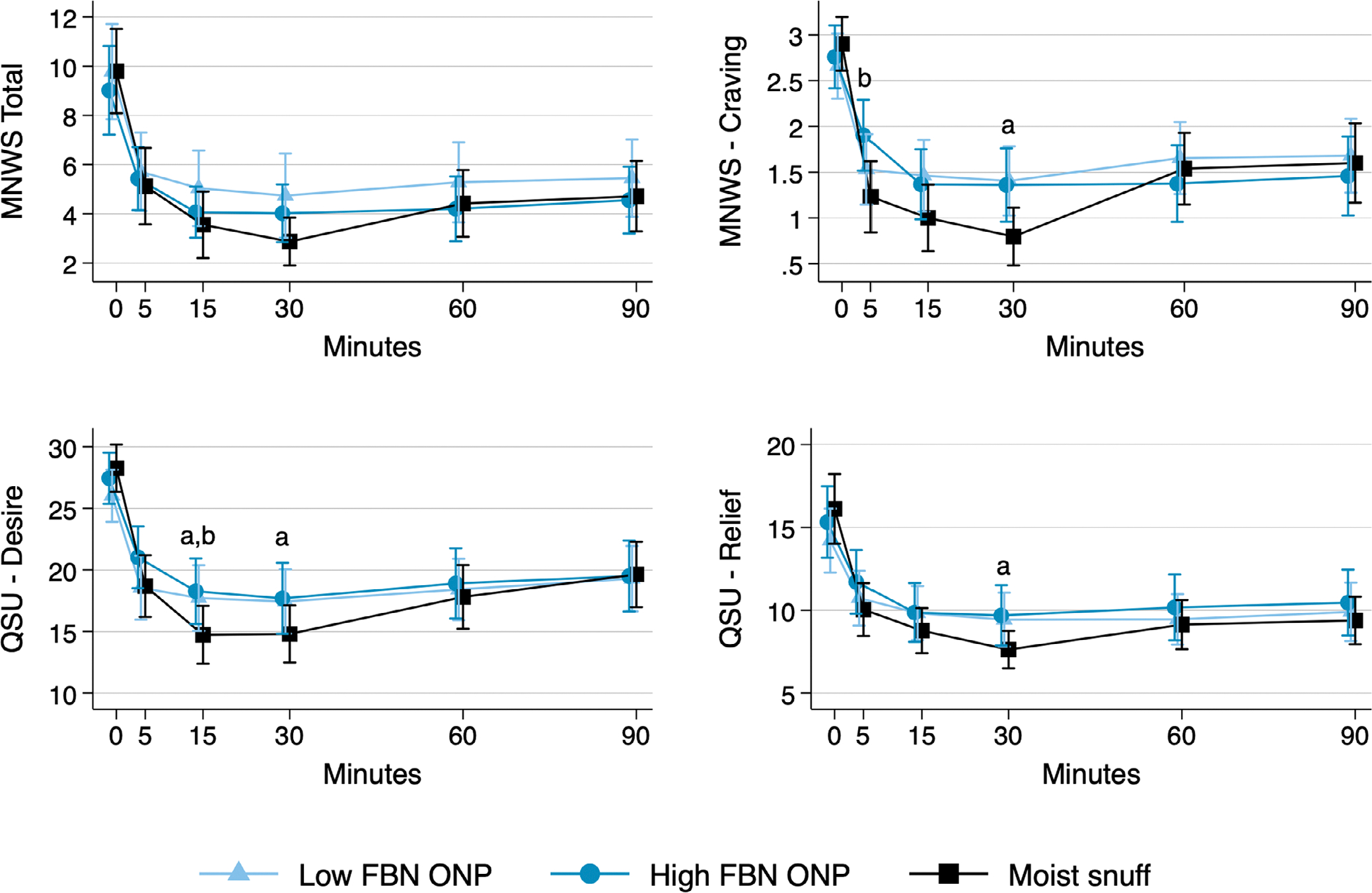

Craving

Across products, craving measured via the MNWS differed from t = 5 through 30 minutes (P ≤ 0.01) (Table 3; Figure 3). Mean craving score was higher at t = 5 minutes for the high FBN ONP versus moist snuff (P < 0.001) and at t = 30 minutes for the low FBN ONP versus moist snuff (P < 0.001).

TABLE 3.

Secondary outcomes of self-reported withdrawal and craving during use of oral nicotine pouches with varied fractions of freebase nicotine versus moist snuff in a sample of healthy adults who use moist snuff, rural and Appalachian Ohio, 2023–2024.a

| Low FBN ONP n = 53b Mean (SD) |

High FBN ONP n = 52b Mean (SD) |

Moist snuff n = 53b Mean (SD) |

Comparison across products P-value |

Low FBN ONP vs. moist snuff P-valuec |

High FBN ONP vs. moist snuff P-valuec |

Low FBN ONP vs. high FBN ONP P-valuec |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| MNWS withdrawal symptomsd | |||||||

| 5 min | 5.7 (5.5) | 5.4 (4.5) | 5.1 (5.4) | 0.81 | – | – | – |

| 15 min | 5.0 (5.4) | 4.1 (3.5) | 3.6 (4.6) | 0.22 | – | – | – |

| 30 min | 4.7 (6.0) | 4.0 (4.0) | 2.9 (3.3) | 0.09 | – | – | – |

| 60 min | 5.3 (5.7) | 4.2 (4.4) | 4.4 (4.8) | 0.72 | – | – | – |

| 90 min | 5.5 (5.5) | 4.6 (4.5) | 4.7 (5.0) | 0.69 | – | – | – |

| MNWS craving | |||||||

| 5 min | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.4) | 0.003 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.23 |

| 15 min | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.0 (1.3) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.75 |

| 30 min | 1.4 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.62 |

| 60 min | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.4) | 0.17 | – | – | – |

| 90 min | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.6 (1.5) | 0.36 | – | – | – |

| QSU-Brief Desire subscaled | – | – | – | ||||

| 5 min | 18.6 (9.3) | 21.0 (9.0) | 18.7 (9.0) | 0.08 | – | – | – |

| 15 min | 17.7 (9.7) | 18.3 (9.6) | 14.7 (8.5) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.82 |

| 30 min | 17.4 (9.5) | 17.7 (10.3) | 14.8 (8.3) | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.62 |

| 60 min | 18.4 (9.1) | 18.9 (10.2) | 17.8 (9.3) | 0.49 | – | – | – |

| 90 min | 19.3 (9.5) | 19.5 (10.3) | 19.6 (9.5) | 0.83 | – | – | – |

| QSU-Brief Relief subscale | – | – | – | ||||

| 5 min | 10.7 (5.9) | 11.7 (6.9) | 10.0 (5.7) | 0.09 | – | – | – |

| 15 min | 9.8 (5.9) | 9.9 (6.4) | 8.8 (4.9) | 0.17 | – | – | – |

| 30 min | 9.4 (5.9) | 9.7 (6.5) | 7.6 (4.0) | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.31 |

| 60 min | 9.5 (5.5) | 10.2 (7.1) | 9.1 (5.3) | 0.59 | – | – | – |

| 90 min | 9.9 (6.3) | 10.5 (7.1) | 9.4 (5.1) | 0.79 | – | – | – |

Abbreviations: FBN, freebase nicotine; ONP, oral nicotine pouch; MNWS, Minnesota Withdrawal Scale; QSU-Brief, Questionnaire of Smoking Urges brief form.

n = 62 participants were recruited from rural and Appalachian Ohio counties to complete a three-visit, single-blind, randomized cross-over experiment. Study ONPs were 6 mg nicotine concentration and peppermint flavor. The low FBN ONP was Rogue brand, and the high FBN ONP was Zyn brand.

Participant counts do not sum to the total analytic sample size (n = 62) because of study attrition and visit-level exclusions from the analytic sample because of noncompliance with nicotine abstinence.

Statistical significance following Holm’s procedure is denoted using bold.

Variable was log-transformed for analyses. Untransformed means and SDs are reported in this table.

FIGURE 3.

Self-reported withdrawal and craving symptoms during and following 30-minute use of one low freebase nicotine (FBN) oral nicotine pouch (ONP), one high FBN ONP and 2 g of moist snuff. Abbreviations: MNWS, Minnesota Withdrawal Scale; QSU, Questionnaire of Smoking Urges; FBN, freebase nicotine; ONP, oral nicotine pouch. aStatistically significant difference between low FBN ONP and moist snuff (P ≤ 0.003).bStatistically significant difference between high FBN ONP and moist snuff (P ≤ 0.002).

Across products, craving measured via the QSU-Brief desire subscale (intention or desire to use) differed at t = 15 and 30 minutes (P ≤ 0.006) (Table 3; Figure 3). At t = 15 minutes, desire was higher for the low FBN ONP (P < 0.001) and high FBN ONP (P = 0.002) versus moist snuff. At t = 30 minutes, desire was higher for the low FBN ONP versus moist snuff (P = 0.003). Across products, craving measured via the QSU-Brief relief subscale (relief of negative affect and urge to use) differed at t = 30 minutes (P = 0.003), with the low FBN ONP providing less relief than moist snuff (P < 0.001).

Subjective drug effects

Participants reported both ONPs as moderately appealing, but less appealing than moist snuff (Table 4). For most measures of subjective drug effects, we detected a statistically significant difference across study products, with differences being driven by reduced appeal of both ONPs relative to moist snuff. We detected no significant differences in measures of subjective drug effects between study ONPs. We detected no significant differences across products for measures of aversion or feeling effects from the product.

TABLE 4.

Secondary outcomes of subjective drug effects following use of oral nicotine pouches with varied fractions of freebase nicotine versus moist snuff in a sample of healthy adults who use moist snuff, rural and Appalachian Ohio, 2023–2024.a

| Low FBN ONP n = 53b Mean (SD) |

High FBN ONP n = 52b Mean (SD) |

Moist snuff n = 53b Mean (SD) |

Comparison across products P-value |

Low FBN ONP vs. moist snuff P-valuec |

High FBN ONP vs. moist snuff P-valuec |

Low FBN ONP vs. high FBN ONP P-valuec |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Drug effects and liking | |||||||

| Pleasant to use again right nowd | 59.0 (27.2) | 57.9 (30.1) | 89.7 (12.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.87 |

| Desire/urge to use right nowd | 46.7 (26.4) | 42.6 (28.1) | 84.5 (17.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.36 |

| Need to use for reliefd | 44.8 (29.7) | 46.3 (30.1) | 66.3 (24.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.81 |

| Want to used | 42.5 (27.4) | 41.8 (28.4) | 84.5 (16.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.90 |

| Extent of likingd | 55.4 (27.9) | 53.4 (32.2) | 92.1 (13.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.71 |

| Extent of enjoymentd | 55.2 (28.6) | 52.4 (32.2) | 90.0 (13.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.59 |

| Extent of pleasurablenessd | 57.5 (27.5) | 53.2 (31.9) | 86.7 (14.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.36 |

| Extent of satisfactiond | 59.4 (28.1) | 56.1 (29.2) | 90.4 (12.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.48 |

| Interest in using again in futuree | 5.2 (3.2) | 5.1 (3.2) | 9.4 (1.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.92 |

| Willing to use againe | 6.2 (3.1) | 6.1 (3.4) | 9.4 (1.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.87 |

| mCEQ | |||||||

| Satisfaction | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.5) | 4.8 (1.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.79 |

| Reward | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.3) | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.96 |

| Sensation | 2.4 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.6) | 3.2 (2.1) | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.66 |

| Craving | 2.5 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.92 |

| Aversion >0, n (%)f | 6 (11.3) | 7 (13.5) | 3 (5.8) | 0.45 | – | – | – |

| >Study product effects | – | – | |||||

| Felt any effectsg | 39.2 (26.1) | 37.9 (29.4) | 48.0 (30.6) | 0.07 | – | – | – |

| Felt good effectsg | 47.9 (25.0) | 43.6 (27.3) | 57.3 (25.0) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.005 | 0.35 |

| Felt bad effectsg,h | 7.8 (13.0) | 12.4 (21.7) | 21.5 (29.3) | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.018 | 0.46 |

Abbreviations: FBN, freebase nicotine; ONP, oral nicotine pouch; mCEQ, Modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire.

n = 62 participants were recruited from rural and Appalachian Ohio counties to complete a three-visit, single-blind, randomized cross-over experiment. Study ONPs were 6 mg nicotine concentration and peppermint flavor. The low FBN ONP was Rogue brand, and the high FBN ONP was Zyn brand.

Participant counts do not sum to the total analytic sample size (n = 62) because of study attrition and visit-level exclusions from the analytic sample because of noncompliance with nicotine abstinence.

Statistical significance following Holm’s procedure is denoted using bold.

Response options ranged from 0: ‘not at all’ to 100 ‘very.’

Response options ranged from 0: ‘not at all’ to 10 ‘very.’

Responses were dichotomized to 0 vs. >0 because of a skewed distribution.

Response options ranged from 0: ‘not at all’ to 100 ‘extremely.’

Variable was log-transformed for analyses. Untransformed means and SDs are reported in this table.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis of all n = 70 participants who completed at least one study visit, including those who were noncompliant with nicotine abstinence, had similar findings to our main analyses (Table S2). Mean plasma nicotine concentrations from 5 to 90 minutes, Cmax, and AUC0–90 were higher (reflecting higher starting plasma nicotine concentrations on average), but estimated associations between study product and each outcome were consistent with the main analyses. Point estimates for withdrawal and craving outcomes were similar to the main analyses, but we detected more differences between study products, with participants reporting that both ONPs relieved craving symptoms less effectively than moist snuff from 5 to 30 minutes for most measures. Finally, participants reported similar subjective effects in the sensitivity and main analyses (Table S3).

DISCUSSION

We compared plasma nicotine delivery, craving and withdrawal relief and subjective effects of ONPs with high versus low FBN fractions relative to moist snuff among rural and Appalachian adults who use moist snuff. We observed differences in plasma nicotine concentration from 5 to 90 minutes of product use, with the low FBN ONP delivering less nicotine than both the high FBN ONP and moist snuff. Although we did not identify differences in withdrawal symptoms across study products, we detected differences in craving symptoms, particularly in comparisons between the low FBN ONP and moist snuff. Participants found both study ONPs moderately appealing, but less appealing than moist snuff. Overall, our findings suggest that higher FBN ONPs might be a better substitute for moist snuff because of their capacity for greater plasma nicotine delivery.

As with moist snuff [21, 22], using the high (vs. low) FBN ONP resulted in greater plasma nicotine delivery. The high FBN ONP also delivered nicotine similarly to moist snuff. However, comparisons to moist snuff should be interpreted in the context of our 2 g moist snuff serving size. Although we standardized serving size to minimize differences across participants and maximize comparability to other studies [21, 22], standardization also meant that most participants were using at least 1 g less of moist snuff than they would typically use. It is also possible that participants would have preferred to use multiple ONPs at once [40]. Ultimately, although our study was designed to compare plasma nicotine delivery across study products in tightly controlled conditions, research investigating plasma nicotine delivery across different ONP use topographies, and compared to participants’ usual serving size of moist snuff, would improve understanding of ONPs’ harm reduction potential for moist snuff users.

Despite large differences in plasma nicotine delivery across products, we identified no differences in withdrawal relief. This finding is consistent with our other studies evaluating plasma nicotine delivery and withdrawal relief from ONPs [41, 42]. It is possible that strong withdrawal symptoms from the 12-hour nicotine abstinence period, followed by using products that delivered an acceptable amount of nicotine, biased our results toward the null. Moreover, we observed differences in craving symptoms across products, most often after 15 or 30 minutes of product use. Although craving symptoms were similar between ONPs, estimates in the low FBN ONP condition were typically less variable, and therefore, we detected more differences in craving between the low FBN ONP and moist snuff. With little difference in craving between study ONPs, and in the context of our plasma nicotine delivery and withdrawal relief findings, we expect that other factors, like the standardized ONP use topography and sensory effects, might contribute to the weaker craving relief ratings we observed for ONPs.

As in the extant literature [41, 42], we did not detect differences in subjective effects between the low and high FBN ONPs, and participants rated their moist snuff as more appealing than ONPs. Because we excluded participants who had recently used ONPs, participants’ lack of familiarity with ONPs could have contributed to these findings. For example, it is possible that participants were responding more broadly to differences between ONPs and moist snuff than discerning relatively smaller differences between ONPs. Nonetheless, participants consistently reported that both ONPs were moderately enjoyable, pleasant and satisfying, and they reported a moderate interest and willingness to use ONPs in the future. This pattern of results suggests that ONPs might be an acceptable substitute for moist snuff, although repeated sampling of ONPs would likely be necessary to bolster actual switching from ONPs to moist snuff [43]. Alternatively, conducting a similar study to the current project, but in a sample of experienced ONP users, could result in greater discernment of differences in subjective effects across ONPs.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. Because of the limited demographic and regional diversity of our sample, our results might not generalize to the full population of moist snuff users. Although SLT is predominantly used in the US by white non-Hispanic men in the Midwest and South and rural and Appalachian communities [1], other subgroups of SLT users (e.g. in rural Western US communities) might hold different perceptions of ONPs. Next, standardizing the serving size of moist snuff meant that some participants were under dosed relative to their typical serving in the moist snuff condition. Relatedly, we standardized the use of ONPs to be between the upper lip and gum for 30 minutes. Although this minimized differences between participants (and between conditions within participant), it is possible that participants would have rated ONPs differently using different topographies. With recent research describing that lower lip placement is common and that adults often use ONPs for <15 minutes [40, 44], future research should explore how differing ONP use topographies affect plasma nicotine delivery, craving and withdrawal relief and subjective effects. Another limitation was that we could not verify compliance with nicotine abstinence in real time, leading to missing data. Other methods of confirming nicotine abstinence among users of non-combustible tobacco products should be considered. Our final limitations are related to the study products. First, we chemically characterized ONPs that came from different lots than what was used in the clinical trial. It is, therefore, possible that study product characteristics could have changed in unknown ways, biasing our results toward or away from the null. Second, although the commercial ONPs tested had similar nicotine concentrations, but widely disparate nicotine freebase fractions, there were other product differences, including moisture content, pouch weight and likely differences in flavor, which could have affected product ratings.

In conclusion, the high FBN ONP—which was the market-dominating Zyn brand [45]—delivered nicotine like moist snuff and delivered over twice as much nicotine as the low FBN ONP. The increased nicotine delivery of the high FBN ONP suggests that regulations aiming to position ONPs as a strong harm reduction option for moist snuff users should consider specifying a minimum allowable FBN fraction. Future research that investigates joint effects of FBN fraction and total nicotine concentration would further bolster comprehensive regulation of ONPs (e.g. would ONPs with high nicotine concentration and high FBN fraction be the most appealing to moist snuff users or would these products be too harsh?). With a large proportion of moist snuff users reporting dual use with ONPs [46], identifying additional factors that support complete transitions from moist snuff use to ONPs (e.g. flavors, total nicotine content and pouch material or size) are needed.

Supplementary Material

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants for their contributions to this research.

Funding information

This research was supported by The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center - The James. B.K.H. was supported by grant number K01DA055696 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. B.K.H., A.H., D.M., A.E.H., M.C.B. and T.L.W. were supported by grant number U54CA287392 from the National Cancer Institute and Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Products, and B.K.H., A.H. and T.L.W. were supported by grant number R01CA289551 from the National Cancer Institute. This work was partially funded by grant number P30CA016058 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Jamal A, Davis Lynn BC, Mayer M, Alcantara IC, et al. Tobacco product use among adults - United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(18):475–83. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7218a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Miller EJ, Wackowski OA. Examining market trends in smokeless tobacco sales in the United States: 2011–2019. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;23(8):1420–4. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stepanov I, Hatsukami D. Call to establish constituent standards for smokeless tobacco products. Tob Regul Sci. 2016;2(1):9–30. 10.18001/TRS.2.1.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyss AB, Hashibe M, Lee YCA, et al. Smokeless tobacco use and the risk of head and neck cancer: Pooled analysis of US studies in the INHANCE consortium. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(10):703–16. 10.1093/aje/kww075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smokeless Tobacco and Some Tobacco-Specific N-Nitrosamines IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, International Agency for Research on Cancer ed. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer; distributed by WHO Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu YH, Tatakis DN, Wee AG. Smokeless tobacco use and periodontal health in a rural male population. J Periodontol. 2010;81(6):848–54. 10.1902/jop.2010.090310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaffee BW, Couch ET, Urata J, Gansky SA, Essex G, Cheng J. Predictors of smokeless tobacco susceptibility, initiation, and progression over time among adolescents in a rural cohort. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(7):1154–66. 10.1080/10826084.2018.1564330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang JT, Levy DT, Meza R. Trends and Factors Related to Smokeless Tobacco Use in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(8):1740–8. 10.1093/ntr/ntw090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pesko MF, Robarts AMT. Adolescent tobacco use in urban versus rural areas of the United States: The influence of tobacco control policy environments. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(1):70–6. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson RJ, Ryerson AB, Singh SD, King JB. Cancer Incidence in Appalachia, 2004–2011. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(2):250–8. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mallock N, Schulz T, Malke S, Dreiack N, Laux P, Luch A. Levels of nicotine and tobacco-specific nitrosamines in oral nicotine pouches. Tob Control. 2024;33(2):193–9. 10.1136/tc-2022-057280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stepanov I, Jensen J, Hatsukami D, Hecht SS. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines in new tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(2):309–13. 10.1080/14622200500490151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talbot EM, Giovenco DP, Grana R, Hrywna M, Ganz O. Cross-promotion of nicotine pouches by leading cigarette brands. Tob Control. 2023;32(4):528–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czaplicki L, Patel M, Rahman B, Yoon S, Schillo B, Rose SW. Oral nicotine marketing claims in direct-mail advertising. Tob Control. 2021;31(5):663–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Patterns of Non-Cigarette Tobacco and Nicotine Use Among Current Cigarette Smokers and Recent Quitters: Findings From the 2020 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(9):1611–6. 10.1093/ntr/ntab040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaiha SM, Lin C, Lempert LK, Halpern-Felsher B. Use, marketing, and appeal of oral nicotine products among adolescents, young adults, and adults. Addict Behav. 2023;140:107632. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornacchione Ross J, Kowitt SD, Rubenstein D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of flavored novel oral nicotine product use among a national sample of youth. Addict Behav. 2024;152:107982. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2024.107982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hrywna M, Gonsalves NJ, Delnevo CD, Wackowski OA. Nicotine pouch product awareness, interest and ever use among US adults who smoke, 2021. Tob Control. 2023;32(6):782–5. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-057156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. p. 1–978. https://permanent.access.gpo.gov/gpo45352/PDFversion/Fullreport/full-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomar SL, Henningfield JE. Review of the evidence that pH is a determinant of nicotine dosage from oral use of smokeless tobacco. Tob Control. 1997;6(3):219–25. 10.1136/tc.6.3.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickworth W, Rosenberry ZR, Gold W, Koszowski B. Nicotine absorption from smokeless tobacco modified to adjust pH. J Addic Res Ther. 2014;5(3):1000184. 10.4172/2155-6105.1000184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilhelm J, Mishina E, Viray L, Paredes A, Pickworth WB. The pH of smokeless tobacco determines nicotine buccal absorption: Results of a randomized crossover trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022;111(5):1066–74. 10.1002/cpt.2493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richter P, Hodge K, Stanfill S, Zhang L, Watson C. Surveillance of moist snuff: Total nicotine, moisture, pH, un-ionized nicotine, and tobacco-specific nitrosamines. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(11):1645–52. 10.1080/14622200802412937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alpert HR, Koh H, Connolly GN. Free nicotine content and strategic marketing of moist snuff tobacco products in the United States: 2000–2006. Tob Control. 2008;17(5):332–8. 10.1136/tc.2008.025247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanfill S, Tran H, Tyx R, Fernandez C, Zhu W, Marynak K, et al. Characterization of total and unprotonated (free) nicotine content of nicotine pouch products. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(9):1590–6. 10.1093/ntr/ntab030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connolly GN. The marketing of nicotine addiction by one oral snuff manufacturer. Tob Control. 1995;4(1):73–9. 10.1136/tc.4.1.73 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter LP, Stitzer ML, Henningfield JE, O’Connor RJ, Cummings KM, Hatsukami DK. Abuse liability assessment of tobacco products including potential reduced exposure products. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(12):3241–62. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiler M, Breland A, Spindle T, Maloney S, Lipato T, Karaoghlanian N, et al. Electronic cigarette user plasma nicotine concentration, puff topography, heart rate, and subjective effects: Influence of liquid nicotine concentration and user experience. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;25(5):380–92. 10.1037/pha0000140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller-Hamilton B, Mehta T, Hale JJ, et al. Effects of flavourants and humectants on waterpipe tobacco puffing behaviour, biomarkers of exposure and subjective effects among adults with high versus low nicotine dependence. Tob Control. Published online January 6. 2021;tobaccocontrol-2020-056062. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Federal Register. Annual submission of the quantity of nicotine contained in smokeless tobacco products manufactured, imported, or packaged in the United States; 1999. p. 14085–96. [PubMed]

- 31.CDC. Notice regarding revisions to the laboratory protocol to measure the quantity of nicotine contained in smokeless tobacco products manufactured, imported, or packaged in the United States. Fed Regist. 2009;74:712–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hughes JR. Signs and Symptoms of Tobacco Withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43(3):289. 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3(1):7–16. 10.1080/14622200020032051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leavens EL, Driskill LM, Molina N, Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A, Brett EI, et al. Comparison of a preferred versus non-preferred waterpipe tobacco flavour: Subjective experience, smoking behaviour and toxicant exposure. Tob Control. 2018;27(3):319–24. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arger CA, Heil SH, Sigmon SC, Tidey JW, Stitzer ML, Gaalema DE, et al. Preliminary validity of the modified cigarette evaluation questionnaire in predicting the reinforcing effects of cigarettes that vary in nicotine content. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;25(6):473–8. 10.1037/pha0000145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, Baker CL, Merikle E, Olufade AO, Gilbert DG. Confirmatory factor analyses and reliability of the modified cigarette evaluation questionnaire. Addict Behav. 2007;32(5):912–23. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Connor RJ, Lindgren BR, Schneller LM, Shields PG, Hatsukami DK. Evaluating the utility of subjective effects measures for predicting product sampling, enrollment, and retention in a clinical trial of a smokeless tobacco product. Addict Behav. 2018;76:95–9. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mushtaq N, Beebe LA. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Severson 7-item Smokeless Tobacco Dependence Scale (SSTDS). Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(7):1224–9. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa269.10.1093/ntr/ntaa269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lunell E, Fagerström K, Hughes J, Pendrill R. Pharmacokinetic comparison of a novel non-tobacco-based nicotine pouch (ZYN) with conventional, tobacco-based swedish snus and american moist snuff. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(10):1757–63. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dowd AN, Thrul J, Czaplicki L, Kennedy RD, Moran MB, Spindle TR. A cross-sectional survey on oral nicotine pouches: Characterizing use-motives, topography, dependence levels, and adverse events. Nicotine Tob Res. 2024;26(2):245–9. 10.1093/ntr/ntad179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keller-Hamilton B, Alalwan MA, Curran H, et al. Evaluating the effects of nicotine concentration on the appeal and nicotine delivery of oral nicotine pouches among rural and Appalachian adults who smoke cigarettes: A randomized cross-over study. Addiction. 2024;119(3):464–75. 10.1111/add.16355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keller-Hamilton B, Curran H, Alalwan M, Hinton A, Brinkman MC, El-Hellani A, et al. Evaluating the role of nicotine stereoisomer on nicotine pouch abuse liability: A randomized crossover trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2025;27(4):658–65. 10.1093/ntr/ntae079.27.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dahne J, Wahlquist AE, Smith TT, Carpenter MJ. The differential impact of nicotine replacement therapy sampling on cessation outcomes across established tobacco disparities groups. Prev Med. 2020;136:106096. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becker E, McCaffrey S, Lewis J, Vansickel A, Larson E, Sarkar M. Characterization of ad libitum use behavior of On! nicotine pouches. Am J Health Behav. 2023;47(3):428–49. 10.5993/AJHB.47.3.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Majmundar A, Okitondo C, Xue A, Asare S, Bandi P, Nargis N. Nicotine pouch sales trends in the US by volume and nicotine concentration levels from 2019 to 2022. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2242235. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.42235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel M, Kierstead EC, Kreslake J, Schillo BA. Patterns of oral nicotine pouch use among U.S. adolescents and young adults. Prev Med Rep. 2023;34:102239. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.