Abstract

This study aimed to define required forensic mental health service types in Australia. A staged Delphi process was used, including: (1) reference group consultation to establish a set of core forensic mental health service types; (2) Delphi survey to seek consensus on identified service types and definitions among forensic mental health stakeholders in Australia; and (3) amendment of service definitions in response to survey feedback. Nine forensic mental health service types were identified. Consensus (>80% agreement) was achieved among Delphi respondents that all services were core components of an ideal forensic mental health system. These included forensic bed-based (acute, sub-acute, non-acute, non-acute community), forensic community, outreach, prison and court liaison services. The high levels of agreement on service types are notable considering legislative differences impacting on design and operation of services across jurisdictions. The findings could contribute to the evidence base required for needs-based planning of forensic mental health services.

Keywords: Delphi, forensic mental health, forensic mental health services, health service planning, prison mental health services

Introduction

Adults with mental illness are over-represented within the criminal justice system, presenting significant health and welfare concerns (Butler et al., 2006; Fazel & Seewald, 2012; Stewart et al., 2021). Justice-involved populations often have other health or complex social needs (Baranyi et al., 2018; Binswanger et al., 2009; Fazel et al., 2006; Productivity Commission, 2021). Furthermore, incarceration is associated with negative health outcomes, including increased risk of suicide and mortality following release from prison (Fazel et al., 2016; Forsyth et al., 2018). In Australia, First Nations people are overrepresented in the criminal justice system, particularly in prisons (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2024), and are known to have disproportionally higher mental health needs (Heffernan et al., 2012).

Despite high levels of needs, justice-involved individuals experience limited access to the health care available to other populations (Kinner et al., 2012; Linnane et al., 2023). In Australia, this limited access results in part from the exclusion of people in custody from Medicare, the country’s universal health care program, as well as underinvestment in services and workforce (Davidson et al., 2020; Plueckhahn et al., 2015). Individuals released from prison utilise health services at higher rates than the general population (Carroll et al., 2017; Snow et al., 2022). The provision of appropriate, comprehensive forensic mental health care is essential for preventing poor health outcomes and further criminalisation (Crocker et al., 2017; Munetz & Griffin, 2006).

Forensic mental health services provide mental health care to people engaged with (or at risk of engaging with) the criminal justice system who have mental illness (Every-Palmer et al., 2014). This includes mental health care in prisons, inpatient and community specialist forensic mental health care, and court liaison services. The care provided is dependent on an individual’s severity of mental illness, security requirements, stage of engagement with the criminal justice system, and available resources within the mental health system (O’Donahoo & Simmonds, 2016).

Forensic mental health service models vary by jurisdiction (Every-Palmer et al., 2014; Salize et al., 2023; Salize & Dreßing, 2005; Sampson et al., 2016), largely due to the unique role of policy and legal frameworks in defining and engaging with justice-involved populations, and different ways in which boundaries are drawn between forensic and general mental health populations and services (Jansman-Hart et al., 2011; Khan et al., 2018). Globally, there is no guideline for the ideal design of forensic services or systems (Crocker et al., 2017; Dean, 2020). The lack of availability of unified definitions to describe service models in a clear and consistent manner has been identified as a knowledge gap (McKenna & Sweetman, 2020).

Within Australia, state and territory forensic mental health systems share common elements across models of care (Dean, 2020), but differ in precise models of service delivery due to varying legal frameworks, geography and demographics (Bartels et al., 2018; Ellis, 2020; Hanley & Ross, 2013). For example, some jurisdictions employ dedicated mental health teams within prisons, while others use in-reach into prisons by specialist forensic mental health services (Every-Palmer et al., 2014). Community forensic mental health services also vary; some jurisdictions provide direct specialist case management under a ‘parallel’ model of care (i.e. parallel to general mental health services), whereas others operate under an ‘integrated’ model of care, in which forensic teams provide specialist consultation liaison in-reach to general mental health services for the care of forensic consumers (Ellis, 2020; Latham & Williams, 2020). Service models are necessarily varied, due to the country’s unique geography and variable population density. These factors greatly affect health service access and delivery and necessitate innovative models of service delivery, such as the hub-and-spoke model (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023; Elrod & Fortenberry, 2017). Considered together, differences across jurisdictions pose challenges for coordinated planning of services.

A national model to plan forensic mental health services in Australia is needed to systematically estimate required resources to meet population needs (Whiteford et al., 2023), ensuring that services are available to those who require them (Productivity Commission, 2021). Coordinated service planning is also important to bring forensic mental health services to parity with general mental health services, which have common guidelines and planning requirements. A national model for forensic mental health service planning that is based on commonalities across jurisdictions would support the use of clear and consistent terminology among health planners. Such a model would allow the establishment of standardised national benchmarks to improve care and enable comparison across jurisdictions. One example of a needs-based planning model is Australia’s National Mental Health Service Planning Framework, which is used to support planning to ensure adequate health service resourcing is available to meet population needs (Diminic et al., 2022). In recent years there have been calls to develop modelling for justice-involved populations, which was not included in initial versions of this model (David McGrath Consulting, 2019; Davidson et al., 2020; Productivity Commission, 2020; Southalan et al., 2020).

To achieve needs-based planning in Australia, an understanding of the core forensic mental health service types that should be available, and definitions of these service types, is required. National principles to guide the provision of forensic mental health care discuss generally the types of care that should be provided; however, specific service types are not included (Australian Ministers’ Advisory Council Mental Health Standing Committee, 2006). Furthermore, a recent consultation found many forensic mental health stakeholders were unaware of these principles (Queensland Forensic Mental Health Service & Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research, 2022).

Aims

This study aimed to establish and define the core service types that should exist within an ideal forensic mental health system and seek consensus among a range of participants with experience in forensic mental health services. This information could contribute to the evidence base required to enable needs-based planning of forensic mental health services.

Method

Study design

A Delphi process including expert consultation and an online survey was used (Msibi et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2014; Westby et al., 2013; Young et al., 2022). The Delphi process was chosen as it allows a wide range of geographically diverse participants to voice anonymous opinions with the aim of generating consensus on items of interest to the research question (Barrett & Heale, 2020; Iqbal & Pipon-Young, 2009; Jünger et al., 2017; Waggoner et al., 2016). Services responding solely to the substance abuse or intellectual disability needs of people within the criminal justice system were considered out of scope. Ethics approval was obtained through the University of Queensland (Ethics IDs: 2020/HE001887 & 2022/HE002250).

Stage 1: Reference group consultation

Initial consultation was conducted through a broader project to scope the feasibility of developing a needs-based planning model for forensic mental health services in Australia. A panel of senior forensic mental health clinicians were identified through their leadership roles within forensic mental health services and invited to participate via email in a series of three one-day meetings during 2018. Additional delegates were nominated by invitees to attend meetings due to their specialist knowledge where relevant, including forensic mental health service clinical and operational directors. During meetings, reference group members were asked to draw on professional experiences and, through iterative group discussion, generate a set of provisional inputs for a forensic mental health service planning model. At the conclusion of the three meetings, a set of provisional modelling inputs were identified, including nine core forensic mental health service types with accompanying service definitions. Results from this consultation were used in the development and implementation of a Delphi process.

Stage 2: Online survey

The survey was conducted over three rounds between November 2020 and January 2021 to seek agreement on the service types and definitions developed in Stage 1.

Recruitment

Purposive and snowball sampling were used to identify prospective participants with expertise in forensic mental health care. A reference group, consisting of members of a network of senior clinical leaders in forensic mental health, identified key stakeholders to invite from forensic mental health service settings within each Australian jurisdiction. Stakeholders from forensic mental health services, non-government organisations, judicial services, corrective and custodial health services, and police were invited, as well as people with lived experience within, or supporting someone within, the forensic mental health system. Participants from the Stage 1 reference group consultation were also invited. Invitees were asked to circulate the invitation within their networks.

Survey design

The survey questionnaire was developed by the research team and delivered via Checkbox online survey platform. Survey content is summarised in Table 1. The survey was structured according to key settings in which forensic mental health services are provided (i.e. bed-based, community, prison, court); participants were able to select survey sections to complete based on their expertise. Briefing documents explaining key concepts and definitions were developed to assist participant understanding and interpretation of questions.

Table 1.

Example Delphi survey questions from each round.

| Survey round | Example questions |

|---|---|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

Survey process

Each survey round was open for up to three weeks. The first round was sent to all invitees; second and third round questionnaires were sent to all participants who had completed the previous round, so results were not confounded by the addition of new respondents who did not have the context from prior rounds. Between survey rounds, qualitative and quantitative responses were analysed to highlight areas of agreement and disagreement regarding service types and definitions. Qualitative responses were synthesised, and key themes were refined to create new consensus items (i.e. amendments to service definitions or additional service types), which were presented back to participants in subsequent rounds. The Round 2 and 3 questionnaires used four-point Likert scales (‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘agree’, ‘strongly agree’) to seek consensus on newly proposed items. Round 3 also included one question with a five-point Likert scale to rank additional core service types.

Analysis

There is no uniform definition for consensus in Delphi studies (Barrett & Heale, 2020; Drumm et al., 2022; Niederberger & Spranger, 2020). Here, consensus was defined as at least 80% of respondents answering the same way (i.e. ‘yes’ or ‘no’ in Round 1; agree/strongly agree or disagree/strongly disagree in Rounds 2 and 3), as used in previous studies (Penm et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2014; Watson et al., 2019). Descriptive statistics were generated for Likert scale response questions (mean, standard deviation and range). All items that did not achieve consensus were presented back to participants in subsequent rounds with the level of agreement reached for their re-scoring. Items that did not reach consensus after the third round were discussed with a reference group during Stage 3.

Stage 3: Reference group consultation

Two video-conference meetings were convened with a reference group of senior forensic mental health clinicians to discuss survey results. Membership of this reference group was drawn from the network who guided the recruitment of participants during Stage 2. Some, but not all, participants in this reference group took part in the Stage 1 consultation. During meetings, the consensus results for all items (e.g. service types, edits to service definitions, and suggested additional service types) were reviewed. The reference group made judgements as to the appropriateness (i.e. correctness and distinctiveness) of each item based on their professional experience. Items deemed to be inappropriate were not included in the final set of core service types and descriptions. This consultation added additional insight and context for survey responses, including discussing possible rationales for why some items did not achieve consensus.

Results

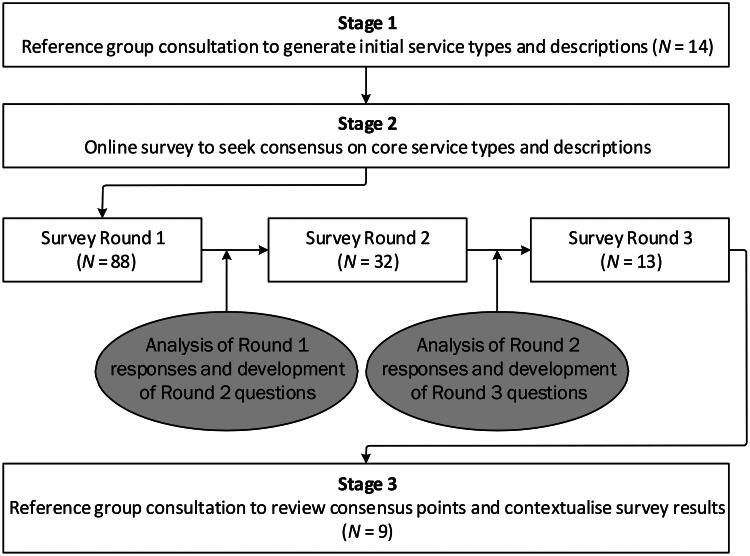

The Stage 1 reference group consultation included 14 participants from seven out of eight Australian jurisdictions who all held senior positions within forensic mental health services. The Stage 2 online survey included participants from all Australian jurisdictions. Over 200 participants accessed the survey; however, respondent numbers decreased with each round (Figure 1). Across all survey rounds, participants from forensic mental health services were the largest group. Participants also included police, magistrates and a prison director. There was lived experience representation only in Round 1 of the survey (5% of participants identified as a consumer or carer). The Stage 3 reference group consultation included nine participants from five jurisdictions who all held senior positions within forensic mental health services.

Figure 1.

Study process and participation.

Core service types

All nine forensic mental health service types developed through the Stage 1 reference group consultation achieved consensus during Round 1 of the survey (Table 2). The number of respondents to questions about each service type varied, ranging from 9 to 41 (Table 2). The largest number of participants answered questions about the Community Forensic Outreach Service (n = 41); the fewest answered questions about non-acute bed-based service types (n = 9). The only service type that all participants agreed was a core service type was the Court Liaison Service. The Prison Mental Health Service had the lowest level of agreement among repondents (88%). However, two of the three respondents who did not agree this was a core service type provided qualitative feedback suggesting they did think it was a core service type, but disagreed with the service definition. Qualitative responses to this effect included: ‘a lot more detail is required to make functional models of care in prisons’ and ‘while the service attributes aren’t wrong, they’re inadequate to describe the level of care.’ There were three instances where this apparent misalignment within individual responses occurred for other core service types.

Table 2.

Agreement on core service types for forensic mental health services during survey Round 1.

| Service type | Respondentsa (n = 88) (n) | Core service agreementb (%) |

Service definition agreementc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Court Liaison Service | 37 | 100 | 81 |

| Community Forensic Outreach Service | 41 | 98 | 63 |

| Community Forensic Mental Health Service | 35 | 97 | 83 |

| Acute Forensic Management Unit | 27 | 96 | 91 |

| Acute Forensic Assessment Unit | 23 | 93 | 81 |

| Sub-Acute Forensic Unit | 11 | 91 | 82 |

| Non-Acute Forensic Unit | 9 | 89 | 67 |

| Non-Acute Forensic Rehabilitation Unit | 9 | 89 | 78 |

| Prison Mental Health Service | 26 | 88 | 58 |

aRespondents were able to select the service types they answered questions about based on their expertise.

bProportion of respondents who selected ‘Yes’ when asked whether the presented service type was a core component of an ideal forensic mental health system.

cProportion of respondents who selected ‘Yes’ when asked whether all key functions of the service were included in the service definition.

dFor full definitions of service types see Appendix A.

Definitions of core service types

Agreement about whether all key functions were described for each service type highlighted heterogeneity among survey participants (Table 2). In Round 1 of the survey, the highest level of agreement among respondents was for the preliminary definition of the Acute Forensic Management Unit (91%); the lowest was for the Prison Mental Health Service (58%). Qualitative feedback suggesting amendments to service definitions was at times contradictory: for example, opposing feedback was received about the appropriateness of the Prison Mental Health Service model described (Box 1).

Box 1.

Examples of heterogeneity in survey qualitative feedback on proposed service definitions

| Referring to Community Forensic Outreach Services: Respondent 1: [It is] ‘essential that forensic specialist knowledge is available to community services.’ Respondent 2: [Services should provide] ‘education for stakeholders – Police, ambulance, court, GP etc.’ Respondent 3: ‘I disagree with providing specialised training to general mental health service and agencies in the criminal justice system.’ Referring to Prison Mental Health Services: Respondent 4: ‘wouldn’t it be great to have a functioning service that provided those services and in reality interfaced with the public community teams in the metro and country regions.’ Respondent 5: ‘This model of care is contentious as it does not outline what a prison mental health unit entails. It is against current guidelines.’ |

Table 3 demonstrates the translation of qualitative feedback into new consensus items (i.e. attributes to include in service definitions), the level of consensus reached among survey participants, and the feedback provided by the Stage 3 reference group. Commonly received qualitative feedback was translated into new service attributes; however, not all new service attributes achieved consensus during subsequent survey rounds. For example, Round 1 Delphi respondents suggested that Court Liaison Services should provide assessments to determine fitness for trial and cognitive status. However, when this service attribute was proposed in survey Round 2, only 55% of respondents agreed it was a core service attribute (Table 3).

Table 3.

Example qualitative feedback from Delphi consultations on proposed forensic mental health service definitions.

| Service type | Summary definition of service (from Stage 1 reference group meetings) | Feedback received (during survey Round 1) | New service attribute proposed (during survey Round 2) | Consensus reached in survey (agreement)?^ | Result of Stage 3 reference group consultation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Court Liaison Service | This service aims to provide mental health advice, assessments, diversion and referral for people who have been charged with an offense. Key attributes include:

|

‘

specialist psychological assessments for fitness and cognitive status

’

‘ Provision of mental state assessments is important in the diversion program. Ensuring defendants receive treatment asap. ’ |

Court Liaison Services should be responsible for providing specialist psychological assessments to determine fitness and cognitive status. | No (55%) |

Do not include as key attribute Reference group advised this attribute fits better within the function of the Community Forensic Mental Health Service. |

| Community Forensic Outreach Service | This service aims to provide clinical assessment, structured risk assessment, liaison, support, advice and risk management planning support for people who are in the care of mainstream mental health services or in contact with other agencies and who are engaging in (or at risk of engaging in) risky behaviours. Key attributes include:

|

‘

case management of high risk clients should be an integral part of the model of care

’

‘ manage a case load of those patients identified as high risk and beyond the expertise of mainstream services ’ ‘ Dedicated case management of a small number of high risk offenders […] on specific forensic orders may not be suitable for mainstream community [mental health services]. ’ |

Community Forensic Outreach Services case manage a cohort of high-risk patients whose needs are beyond the expertise of mainstream mental health services. | No (75%) |

Do not include as key attribute Reference group advised this statement does not reflect the intention of this core service, which was designed with a consultation liaison function. These services provide assessment and specialist advice to mainstream services. Case management is provided by Community Forensic Mental Health Services. |

| Acute Forensic Assessment Unit | This service aims to provide short to medium-term inpatient assessment and treatment planning services for people in custody who are experiencing severe episodes of mental illness complicated by alleged or proven offending. Key attributes include:

|

‘

Could have more of a trauma aware focus

’

‘ Trauma informed practice needs to be specified within the service attributes. ’ |

The Acute Forensic Assessment Unit provides trauma-informed practice. | Yes (100%) |

Include as key attribute Reference group advised this attribute should be included in all bed-based service definitions. |

| Non Acute Forensic Unit | This service aims to provide long term treatment and rehabilitation in a safe, structured environment for individuals with severe mental illness associated with significant violent or other serious offending behaviour. Key attributes include:

|

‘ Dislike the model suggesting it has to be a prolonged stay (i.e. 12 months +) ’ | The average length of stay within a Non Acute Forensic Unit is dependent on legal circumstances and jurisdictional differences, but would generally be at least 12 months. | Yes (86%) |

Do not include as key attribute Reference group advised this attribute should not be included as it was very similar to a statement in the originally drafted service definition and the phrasing of the first statement was preferred. |

| Non-Acute Forensic Rehabilitation Unit | This service aims to provide long term rehabilitation and treatment for people with severe mental illness associated with significant violent or other serious offending behaviour. Key attributes include:

|

‘ There is no mention of the role of NGO support in these facilities and the model of interactions with health and these services in this setting. ’ | Support provided by Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) is a key aspect of Non Acute Forensic Community Rehabilitation Units. | Yes (88%) | Include as key attribute |

| Prison Mental Health Service | This service aims to provide mental health services to people in prison. Key attributes include:

|

‘

7 days per week and extended hours required

’

‘ prison MH can be responsible for crisis assessment for prisoners at risk of suicide and self harm. So need to be available extended hours and weekends to work with Corrections to put in safety planning ’ |

Prison Mental Health Services should be available 7 days per week, operating on an extended hours schedule. | No (67%) |

Include as key attribute with minor amendment: Edit text to specify workforce can be ‘on site or on call.’ |

^Proportion of respondents who agreed or strongly agreed that the new service attribute should be included in the service definition.

Not all new service attributes that achieved consensus during the survey were considered appropriate to include in the final service definition by the Stage 3 reference group. Survey participants suggested 50 new service attributes across all service types; 33 achieved consensus among survey respondents; 30 were deemed appropriate for inclusion in service definitions; 6 service attributes that did not achieve consensus among survey respondents were deemed appropriate for inclusion in service definitions with minor amendment by the Stage 3 reference group.

Additional core service types

Of Round 1 survey participants, 44% indicated that there were additional core service types not included. There were 10 additional service types suggested, however, only one reached consensus (i.e. ⩾80% agreed or strongly agreed it was a core service type) in subsequent survey rounds (Forensic Step Down (Sub Acute) Unit). When additional suggested service types were reviewed by the Stage 3 reference group, none were deemed appropriate to include as core service types. The reference group suggested that the function of the Forensic Step Down (Sub Acute) Unit was already included within existing bed-based service types. Additional service types suggested that did not reach consensus included: court report writing services, which the reference group suggested are included within the function of Court Liaison Services; specialist psychological intervention services, which the reference group suggested are included within the function of the Community Forensic Outreach Service and the Community Forensic Mental Health Service; and police co-response services, which the reference group suggested are not a core function of forensic mental health services.

Final service descriptions

Final core service types and definitions are included in Appendix A. In each service description, italics indicate text that was added or amended through the Delphi and/or Stage 3 reference group consultation process. These final service descriptions represent agreed core forensic mental health services that should be available in Australia, despite jurisdictional differences that may exist in current service models or operational factors.

Discussion

Nine core service types were identified across forensic mental health settings in Australia, with a high level of agreement. Bed-based services include Acute Forensic Assessment, Acute Forensic Management, Sub Acute Forensic, Non Acute Forensic and Non Acute Forensic Community Rehabilitation Units. Community-based services included Community Forensic Mental Health and Community Forensic Outreach Services. The Prison Mental Health Service and Court Liaison Service were also identified as core services. All service types reached consensus among participants, and heterogeneity in responses about service definitions was addressed through reference group consultation. The identified service types broadly align with Australian forensic mental health services described in previous literature (Davidson et al., 2016; 2020; Dean, 2020; Ellis, 2020; Every-Palmer et al., 2014; Productivity Commission, 2020). They also align with the continuum of ‘balanced’ forensic mental health care outlined by Crocker et al. (2017).

Bed-based services are labelled by acuity and distinguished by level of security, as is done in Australia, New Zealand, England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland (Crocker et al., 2017; McKenna & Sweetman, 2020). This has been referred to in the literature as the ‘standard model’ of bed-based forensic mental health care (Kennedy, 2022). However, beyond a focus on procedural, relational and environmental security, there is little known about models of care for bed-based services in Australia (Khan et al., 2018). The services described here target the dual responsibility of forensic mental health services to balance risk while supporting individual recovery in terms of both mental health and criminogenic needs (i.e. personal factors related to an individual’s offending behaviour, such as antisocial behaviour).

The Prison Mental Health Service aligns with the essential requirements of service provision in prison settings, including screening, triage, assessment, intervention and re-integration, as outlined by Forrester et al. (2018) and the Prison Model of Care in northern New Zealand (Pillai et al., 2016). Although the provision of mental health care in prisons is an essential component of forensic mental health care globally (World Health Organisation, 2008), the definition of a Prison Mental Health Service included in Round 1 of the survey achieved a low level of consensus. The prison mental health workforce in Australia is known to be underresourced (Davidson et al., 2020). It is possible that Delphi participants referred to their own experiences of working in prisons and found the service definition to contain functions or aspects of care that are not currently provided in their jurisdiction due to resourcing constraints. Prison health services should be aligned to the structure of health services in the community, i.e. primary health care, secondary health care and specialist, tertiary care (Levy, 2005). Collaboration with general prison health services to deliver primary care functions is an essential component of comprehensive prison mental health care.

The Court Liaison Service was also identified as a core service type, perhaps due to its importance in diverting people out of the criminal justice system wherever possible and offering onward referral to appropriate mental health services. The service definition is aligned with service aims and models both in Australia and internationally (Chaplin et al., 2022; Davidson et al., 2016). Round 1 survey participants agreed that all key functions were described in the service definition, suggesting that the service definition highlighted commonalities in service provision across Australia. Most additional attributes suggested by participants in Round 1 to enhance the description of this service did not reach consensus in Rounds 2 or 3. This is possibly because the suggested service attributes were highly specialised and not common across all jurisdictions.

The delivery of Community Forensic Mental Health Services in Australia differs across states and territories (Brett et al., 2007; Ellis, 2020). Despite these differences, consensus was achieved on the service definition provided in survey Round 1, highlighting that participants were able to agree on the key attributes of this service type. The definition of this service type was drafted to reflect the service function while remaining agnostic to the various models of service delivery (i.e. parallel vs integrated). The description of this core service type is aligned with that for England and Wales (Latham & Williams, 2020).

Although they serve distinct functions, Community Forensic Outreach Services (CFOS) are related to Community Forensic Mental Health Services. CFOS may be a function of, or specialist team within, Community Forensic Mental Health Services and provide clinical assessment, structured risk assessment, liaison, support, advice, and risk management planning support for consumers who are in the care of mainstream mental health services or in contact with other agencies and who may be at risk of offending. The differing service delivery arrangements across jurisdictions may have resulted in confusion among Delphi participants. In the first round of the Delphi, a high level of agreement was observed for the Community Forensic Outreach Service being a core service type; however, the level of agreement for the service definition was among the lowest. This was further evidenced by the qualitative feedback that CFOS services provide a case management function. However, reference group contextualisation established that case management is not a core function of CFOS, because it is separately described under the attributes of Community Forensic Mental Health Services. This discrepancy may result from the influence of participants’ local experiences on their interpretation of the core service types.

A strength of this study was the diversity of participants consulted, including representation from all Australian jurisdictions. The heterogeneity of responses about service definitions highlights challenges in undertaking consensus work; the included Stage 3 reference group consultation was therefore critical for aligning feedback and revising definitions with best practice principles.

Several limitations were identified. First, there was limited lived experience involvement in this research. The sampling method limited the recruitment and engagement of lived experience stakeholders. Although invitations to participate in the survey were disseminated to lived experience organisations and peak bodies, the invitation may not have been shared through their networks, further limiting the opportunity for lived experience participation. This limitation is important to note, as lived experience stakeholders’ perspectives may be different from those of the stakeholders who participated in this study.

Second, there were small numbers of participants and a drop in survey response rates across the three rounds (coinciding with the end-of-year holiday period). This included loss of the small number of lived experience participants. However, the small number of participants in this study is not surprising, given the specialist topic: not all forensic mental health stakeholders would have had interest or expertise to participate in the survey or would have received the invitation. Furthermore, the potential participant pool for this study was small, given that there are known workforce shortages in Australia’s mental health sector (Department of Health and Aged Care, 2022b), especially for forensic psychiatrists (Acil Allen, 2020).

Third, specific First Nations cultural expertise and consultation were not included in the reference groups or design of this study. Culturally safe and appropriate approaches to mental health care for First Nations people are essential (Page et al., 2022; Perdacher et al., 2019), requiring co-design and appropriate cultural consultation. A decision was made at the outset of the study to conduct separate consultations for First Nations people, including appropriate cultural expertise at their core. The study described here takes a generalist approach that will be supported by additional cultural consultation and does not reflect the steps required to establish core forensic mental health service types for First Nations people.

Fourth, some intersectional service types were not identified during this process, such as services supporting the transition of justice-involved individuals back into the community and psychosocial support services provided by the non-government sector.

Conclusion

This study has generated evidence that could be used to undertake needs-based planning of forensic mental health services in Australia by establishing a set of required service types and definitions, as has been called for in recent policies and reports (Department of Health and Aged Care, 2022a; Productivity Commission, 2020). This information could serve as a key input into a needs-based planning model for forensic mental health services in Australia.

A challenge of needs-based planning is the requirement of common definitions for core service functions. Attempting to generate consensus among participants from different jurisdictions who operate under different service working definitions posed a challenge. Service definitions were developed so their intent and function could be adapted to jurisdictional differences (i.e. defining the function of a service type and, to the extent possible, not specifying the specific setting or other operational factors).

Although undertaking needs-based planning of forensic mental health services in Australia will assist service planners to identify the services required, it is up to health services to properly resource and deliver services to appropriate cohorts. The core service types generated by this study provide health service planners with an understanding of the forensic mental health service types that should be available in their jurisdiction to justice-involved people. By comparing services currently available with the core service types, health planners can identify if there are gaps in their service offerings. The detailed definitions will support planners to accurately map their catchment’s services against the attributes of the identified core service types, to ensure they are comparing like-for-like, based on core functions rather than local service names or groupings. Implementation will then need to be further tailored to specific local legislative requirements and consider the efficient location, staffing and grouping of core service types for the size and distribution of local justice-involved populations.

However, the presence of differences does not preclude the development or use of a nationally consistent model. Although there are differences in forensic mental health service models across Australia, health planners need a consistent and common terminology. This consistency also helps to support the integration between forensic and general mental health services, for which a comprehensive national set of service descriptions exists (Comben et al., 2022). Internationally, the identified service types and definitions could be used to undertake similar needs-based planning activities. Establishing core service types and definitions helps to standardise functions and allows greater comparison across services internationally. It could also be useful in future research evaluating service model effectiveness and understanding outcomes of the identified core service types. Further work is needed to understand how the identified service types and definitions could be tailored to best meet the needs of First Nations people in the criminal justice system in Australia in a culturally safe and appropriate way. To support needs-based planning of forensic mental health services, this work should now be extended to identify the number of people in Australia likely to require each service type in any given year.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the people involved in the consultations conducted as part of this study. We also thank Bill Kingswell, Ed Heffernan, Elissa Waterson, and Fiona Davidson for their insights during the initial consultation phase of this work.

Appendix A.

Final service definitions

Text set in italics was added or amended during the Stage 2 and 3 consultations.

1.

Community Forensic Outreach Service

| Service attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Services provided |

|

| Key features |

|

| Hours of operation | Business hours with after hours on-call emergency service provided by local mainstream or specialist forensic mental health services. |

| Population profile | Consumers often have a complex presentation of severe mental illness, with high levels of comorbidity particularly substance use disorders, severe personality disorders, cognitive impairment, and who pose a significant risk of harm to others. |

| Example service | Community Forensic Outreach Service (Qld) |

2.

Court Liaison Service

| Service attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Services provided |

|

| Key features |

|

| Hours of operation | Business hours (depending on court hours) |

| Population profile | Individuals often have a complex presentation of severe mental illness, with high levels of comorbidity particularly substance use disorders, severe personality disorders, cognitive impairment, and who pose significant risk of harm to others. |

| Example service | Queensland Court Liaison Service |

3.

Community Forensic Mental Health Service

| Service attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Services provided |

|

| Key features |

|

| Hours of operation | Extended hours (on-call service available) |

| Population profile | Individuals often have a complex presentation of severe mental illness that has been associated with serious offending, usually of a violent nature. Primary diagnoses often include psychotic disorders or severe affective disorders with high levels of comorbidity particularly substance use disorders, severe personality disorders or cognitive impairment, and who pose significant risk of harm to others. |

| Example service | N/A |

4.

Prison Mental Health Service

| Service attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Services provided |

|

| Key features |

|

| Hours of operation | Extended hours, on-call service available |

| Population profile | Adults with severe and/or persistent mental illness or situational distress that has a significant impact on their functioning. Primary diagnoses often include psychotic disorders or severe affective disorders with high levels of comorbidity particularly substance use disorders, severe personality disorders or cognitive impairment. Prisoners with mild and moderate mental illness are considered to be the responsibility of primary care. Note: PMHS can be accessed by any person detained in a prison or detention centre. However, the predominant population is male and aged between 18 and 64. Indigenous Australians are over-represented and make up approximately 30% of Australian prisoners. Women are underrepresented, making up less than 9% of Australian prisoners, however the prevalence of mental disorder in female prisoners, particularly moderate and severe disorders, is approximately 1.5 higher than in male prisoners. |

| Example service | N/A |

5.

Acute Forensic Assessment Unit

| Service attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Services provided |

|

| Key features |

|

| Hours of operation | 24 hours/7 days |

| Population profile | Adults in custody with a possible or diagnosed severe mental illness accompanied by alleged or proven offending, which could not be adequately assessed, investigated or treated in prison or in a mainstream mental health service. Individuals often have a complex presentation of severe mental illness, with high levels of comorbidity particularly substance use disorders, severe personality disorders, cognitive impairment, and who pose significant risk of harm to others. |

6.

Acute Forensic Management Unit

| Service attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Services provided |

|

| Key features |

|

| Hours of operation | 24 hours/7 days |

| Population profile | Individuals often have a complex presentation of severe mental illness that has been associated with serious offending, usually of a violent nature. Primary diagnoses often include psychotic disorders or severe affective disorders with high levels of comorbidity particularly substance use disorders, severe personality disorders, cognitive impairment, and who pose significant risk of harm to others. |

| Example service |

|

7.

Sub Acute Forensic Unit

| Service attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Services provided |

|

| Key features |

|

| Hours of operation | 24 hours/7 days |

| Population profile | Individuals often have a complex presentation of severe mental illness that has been associated with serious offending, usually of a violent nature. Primary diagnoses often include psychotic disorders or severe affective disorders with high levels of comorbidity particularly substance use disorders, severe personality disorders or cognitive impairment, and who pose significant risk of harm to others. |

| Example service | James Nash House (SA) |

8.

Non Acute Forensic Unit

| Service attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Services provided |

|

| Key features |

|

| Hours of operation | 24 hours/7 days |

| Population profile | Individuals often have a complex presentation of severe mental illness that has been associated with serious offending, usually of a violent nature. Primary diagnoses often include psychotic disorders or severe affective disorders with high levels of comorbidity particularly substance use disorders, severe personality disorders or cognitive impairment, and who pose significant risk of harm to others. |

| Example service |

|

9.

Non Acute Forensic Community Rehabilitation Unit

| Service attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Services provided |

|

| Key features |

|

| Hours of operation | 24 hours/7 days |

| Population profile | Individuals often have a complex presentation of severe mental illness that has been associated with serious offending, usually of a violent nature. Primary diagnoses often include psychotic disorders or severe affective disorders with high levels of comorbidity particularly substance use disorders, severe personality disorders or cognitive impairment, and who pose significant risk of harm to others. |

| Example service |

|

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Carla Meurk and Sandra Diminic receive salaries from Queensland Health. The authors currently hold time-limited project funding from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, Medical Research Future Fund, Queensland’s Mental Health, Alcohol and Other Drugs Strategy and Planning Branch, and The Queensland Children’s Hospital Foundation.

Charlotte Comben has declared no conflicts of interest.

Zoe Rutherford has declared no conflicts of interest.

Carla Meurk has declared no conflicts of interest.

Julie John has declared no conflicts of interest.

Kevin Fjeldsoe has declared no conflicts of interest.

Kate Gossip has declared no conflicts of interest.

Sandra Diminic has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of The University of Queensland (2020/HE001887 & 2022/HE002250) and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual Delphi participants included in the study. An ethics waiver was approved for secondary analysis of aggregated Reference Group discussion notes.

Funding details

This paper was derived from original research conducted for the National Mental Health Service Planning Framework project funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care and all Australian state and territory health departments. This publication reflects the views of the authors and should not be construed to represent the Department of Health and Aged Care’s or other funders’ views or policies.

References

- Acil Allen. (2020). Mental Health Workforce Labour Market Analysis Final Report. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/mental-health-workforce-labour-market-analysis-final-report.docx.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2024). Prisoners in Australia 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/prisoners-australia/latest-release#key-statistics.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Rural and remote health. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health.

- Australian Ministers’ Advisory Council Mental Health Standing Committee . (2006). National Statement of Principles for Forensic Mental Health. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/e615a500-d412-4b0b-84f7-fe0b7fb00f5f/National-Forensic-Mental-Health-Principles.pdf.aspx#:∼:text=The%20National%20Statement%20of%20Principles,of%20forensic%20mental%20health%20services.

- Baranyi, G., Cassidy, M., Fazel, S., Priebe, S., & Mundt, A. P. (2018). Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in prisoners. Epidemiologic Reviews, 40(1), 134–145. 10.1093/epirev/mxx015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, D., & Heale, R. (2020). What are Delphi studies? Evidence Based Nursing, 23(3), 68–69. 10.1136/ebnurs-2020-103303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, L., Fitzgerald, R., & Freiberg, A. (2018). Public opinion on sentencing and parole in Australia. Probation Journal, 65(3), 269–284. 10.1177/0264550518776763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger, I. A., Krueger, P. M., & Steiner, J. F. (2009). Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63(11), 912–919. 10.1136/jech.2009.090662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett, A., Carroll, A., Green, B., Mals, P., Beswick, S., Rodriguez, M., Dunlop, D., & Gagliardi, C. (2007). Treatment and security outside the wall: Diverse approaches to common challenges in community forensic mental health. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 6(1), 87–99. 10.1080/14999013.2007.10471252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, T., Andrews, G., Allnutt, S., Sakashita, C., Smith, N. E., & Basson, J. (2006). Mental disorders in Australian prisoners: A comparison with a community sample. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(3), 272–276. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01785.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, M., Spittal, M. J., Kemp-Casey, A. R., Lennox, N. G., Preen, D. B., Sutherland, G., & Kinner, S. A. (2017). High rates of general practice attendance by former prisoners: A prospective cohort study. The Medical Journal of Australia, 207(2), 75–80. 10.5694/mja16.00841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin, E., McCarthy, J., Ali, S., Marshall-Tate, K., Xenitidis, K., Harvey, D., Childs, J., Srivastava, S., McKinnon, I., Robinson, L., Allely, C. S., Hardy, S., Tolchard, B., & Forrester, A. (2022). Severe mental illness, common mental disorders, and neurodevelopmental conditions amongst 9088 lower court attendees in London, UK. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 551. 10.1186/s12888-022-04150-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comben, C., Page, I., Gossip, K., John, J., Wright, E., & Diminic, S. (2022). The National Mental Health Service Planning Framework – Service element and activity descriptions – Commissioned by the Australian Government Department of Health. Version AUS V4.1. The University of Queensland. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, A. G., Livingston, J. D., & Leclair, M. C. (2017). Forensic mental health systems internationally. In Roesch R. & Cook A. N. (Eds.), Handbook of Forensic Mental Health Services. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- David McGrath Consulting. (2019). Report on the review of Forensic Mental Health and Disability Services within the Northern Territory. https://health.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/727657/Report-on-the-Forensic-Mental-Health-and-Disability-Services-within-the-NT.pdf.

- Davidson, F., Clugston, B., Perrin, M., Williams, M., Heffernan, E., & Kinner, S. A. (2020). Mapping the prison mental health service workforce in Australia. Australasian Psychiatry, 28(4), 442–447. 10.1177/1039856219891525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, F., Heffernan, E., Greenberg, D., Butler, T., & Burgess, P. (2016). A critical review of mental health court liaison services in Australia: A first national survey. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 23(6), 908–921. 10.1080/13218719.2016.1155509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dean, K. (2020). Literature Review: Forensic Mental Health Models of Care. A report for the NSW Mental Health Commission. https://www.nswmentalhealthcommission.com.au/sites/default/files/old/literature_review_forensic_models_of_care.pdf.

- Department of Health and Aged Care. (2022a). National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Aged Care. (2022b). National Mental Health Workforce Strategy 2022-2032. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-10/national-mental-health-workforce-strategy-2022-2032.pdf.

- Diminic, S., Gossip, K., Page, I., & Comben, C. (2022). Introduction to the National Mental Health Service Planning Framework – Commissioned by the Australian Government Department of Health. version AUS V4.1. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/976cb3dd-18f1-4870-8cfb-9406a16dc844/introduction-to-the-national-mental-health-service-planning-framework-v4-3.pdf.aspx.

- Drumm, S., Bradley, C., & Moriarty, F. (2022). More of an art than a science’? The development, design and mechanics of the Delphi Technique. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy, 18(1), 2230–2236. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A. (2020). Forensic psychiatry and mental health in Australia: An overview. CNS Spectrums, 25(2), 119–121. 10.1017/S1092852919001299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod, J. K., & Fortenberry, J. L. (2017). The hub-and-spoke organization design revisited: A lifeline for rural hospitals. BMC Health Services Research, 17(Suppl 4), 795. 10.1186/s12913-017-2755-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Every-Palmer, S., Brink, J., Chern, T. P., Choi, W., Hern-Yee, J. G., Green, B., Heffernan, E., Johnson, S. B., Kachaeva, M., Shiina, A., Walker, D., Wu, K., Wang, X., & Mellsop, G. (2014). Review of psychiatric services to mentally disordered offenders around the Pacific Rim. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 6(1), 1–17. 10.1111/appy.12109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S., Bains, P., & Doll, H. (2006). Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: A systematic review. Addiction, 101(2), 181–191. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S., Hayes, A. J., Bartellas, K., Clerici, M., & Trestman, R. (2016). Mental health of prisoners: Prevalence, adverse outcomes, and interventions. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 3(9), 871–881. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30142-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S., & Seewald, K. (2012). Severe mental illness in 33,588 prisoners worldwide: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(5), 364–373. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, A., Till, A., Simpson, A., & Shaw, J. (2018). Mental illness and the provision of mental health services in prisons. British Medical Bulletin, 127(1), 101–109. 10.1093/bmb/ldy027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, S. J., Carroll, M., Lennox, N., & Kinner, S. A. (2018). Incidence and risk factors for mortality after release from prison in Australia: A prospective cohort study. Addiction, 113(5), 937–945. 10.1111/add.14106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, N. K., & Ross, S. (2013). Forensic mental health in Australia: Charting the gaps. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 24(3), 341–356. 10.1080/10345329.2013.12035965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, E., Andersen, K. C., Dev, A., & Kinner, S. (2012). Prevalence of mental illness among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Queensland prisons. The Medical Journal of Australia, 197(1), 37–41. 10.5694/mja11.11352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S., & Pipon-Young, L. (2009). The Delphi Method. The Psychologist, 22(7), 598–601. [Google Scholar]

- Jansman-Hart, E. M., Seto, M. C., Crocker, A. G., Nicholls, T. L., & Côté, G. (2011). International trends in demand for forensic mental health services. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 10(4), 326–336. 10.1080/14999013.2011.625591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jünger, S., Payne, S. A., Brine, J., Radbruch, L., & Brearley, S. G. (2017). Guidance on conducting and reporting Delphi studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 31(8), 684–706. 10.1177/0269216317690685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, H. G. (2022). Models of care in forensic psychiatry. BJPsych Advances, 28(1), 46–59. 10.1192/bja.2021.34 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A., Maheshwari, R., & Vrklevski, L. (2018). Clinician perspectives of inpatient forensic psychiatric rehabilitation in a low secure setting: A qualitative study. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law, 25(3), 329–340. 10.1080/13218719.2017.1396863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinner, S. A., Streitberg, L., Butler, T., & Levy, M. (2012). Prisoner and ex-prisoner health: Improving access to primary care. Australian Family Physician, 41(7), 535–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham, R., & Williams, H. K. (2020). Community forensic psychiatric services in England and Wales. CNS Spectrums, 25(5), 604–617. 10.1017/S1092852919001743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, M. (2005). Prisoner health care provision: Reflections from Australia. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 1(1), 65–73. 10.1080/17449200500156905 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linnane, D., McNamara, D., & Toohey, L. (2023). Ensuring universal access: The case for Medicare in prison. Alternative Law Journal, 48(2), 102–109. 10.1177/1037969X231171160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, B., Sweetman, L. E. (2020). Models of Care in Forensic Mental Health Services: A review of the international and national literature. Ministry of Health. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/models-care-forensic-mental-health-services-review-international-and-national-literature.

- Msibi, P. N., Mogale, R., de Waal, M., & Ngcobo, N. (2018). Using e-Delphi to formulate and appraise the guidelines for women’s health concerns at a coal mine: A case study. Curationis, 41(1), e1–e6. 10.4102/curationis.v41i1.1934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munetz, M. R., & Griffin, P. A. (2006). Use of the Sequential Intercept Model as an approach to decriminalization of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 57(4), 544–549. 10.1176/ps.2006.57.4.544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederberger, M., & Spranger, J. (2020). Delphi technique in health sciences: A map. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 457. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donahoo, J., & Simmonds, J. G. (2016). Forensic patients and forensic mental health in Victoria: Legal context, clinical pathways, and practice challenges. Australian Social Work, 69(2), 169–180. 10.1080/0312407X.2015.1126750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Page, I. S., Leitch, E., Gossip, K., Charlson, F., Comben, C., & Diminic, S. (2022). Modelling mental health service needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: A review of existing evidence and expert consensus. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 46(2), 177–185. 10.1111/1753-6405.13202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penm, J., Vaillancourt, R., & Pouliot, A. (2019). Defining and identifying concepts of medication reconciliation: An international pharmacy perspective. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy, 15(6), 632–640. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdacher, E., Kavanagh, D., & Sheffield, J. (2019). Well-being and mental health interventions for Indigenous people in prison: Systematic review. BJPsych Open, 5(6), e95. 10.1192/bjo.2019.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai, K., Rouse, P., McKenna, B., Skipworth, J., Cavney, J., Tapsell, R., Simpson, A., & Madell, D. (2016). From positive screen to engagement in treatment: A preliminary study of the impact of a new model of care for prisoners with serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 9. 10.1186/s12888-016-0711-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plueckhahn, T. M., Kinner, S. A., Sutherland, G., & Butler, T. G. (2015). Are some more equal than others? Challenging the basis for prisoners’ exclusion from Medicare. The Medical Journal of Australia, 203(9), 359–361. 10.5694/mja15.00588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Productivity Commission. (2020). Mental Health (Report no. 95). [Google Scholar]

- Productivity Commission. (2021). Australia’s prison dilemma. Research paper. [Google Scholar]

- Queensland Forensic Mental Health Service, & Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research. (2022). Principles for forensic mental health in Australia: A national stakeholder consultation. https://qcmhr.org/docman/reports/17-principles-for-forensic-mental-health-report-smallfile1/file.

- Salize, H. J., Dreßing, H. (2005). Placement and treatment of mentally ill offenders – Legislation and Practice in EU Member States. https://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_projects/2002/promotion/fp_promotion_2002_frep_15_en.pdf.

- Salize, H. J., Dressing, H., Fangerau, H., Gosek, P., Heitzman, J., Markiewicz, I., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Stompe, T., Wancata, J., Piccioni, M., & de Girolamo, G. (2023). Highly varying concepts and capacities of forensic mental health services across the European Union. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1095743. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1095743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, S., Edworthy, R., Völlm, B., & Bulten, E. (2016). Long-term forensic mental health services: An exploratory comparison of 18 European countries. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 15(4), 333–351. 10.1080/14999013.2016.1221484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snow, K. J., Petrie, D., Young, J. T., Preen, D. B., Heffernan, E., & Kinner, S. A. (2022). Impact of dual diagnosis on healthcare and criminal justice costs after release from Queensland prisons: A prospective cohort study. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 28(3), 264–270. 10.1071/PY21142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southalan, L., Carter, A., Meurk, C., Heffernan, E., Borschmann, R., Waterson, E., Young, J., & Kinner, S. (2020). Mapping the forensic mental health policy ecosystem in Australia: A national audit of strategies. Policies and plans. A report for the National Mental Health Commission.

- Stewart, A., Ogilvie, J. M., Thompson, C., Dennison, S., Allard, T., Kisely, S., & Broidy, L. (2021). Lifetime prevalence of mental illness and incarceration: An analysis by gender and Indigenous status. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56(2), 244–268. 10.1002/ajs4.146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S. L., Wakerman, J., & Humphreys, J. S. (2014). What core primary care services should be available to Australians living in rural and remote communities? BMC Family Practice, 15, 143. 10.1186/1471-2296-15-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner, J., Carline, J. D., & Durning, S. J. (2016). Is there a consensus on consensus methodology? Descriptions and recommendations for future consensus research. Academic Medicine, 91(5), 663–668. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, K. E., Singleton, J. A., Tippett, V., & Nissen, L. M. (2019). Defining pharmacists’ roles in disasters: A Delphi study. PLoS One, 14(12), e0227132. 10.1371/journal.pone.0227132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westby, M. D., Brittain, A., & Backman, C. L. (2013). Expert consensus on best practices for post-acute rehabilitation after total hip and knee arthroplasty: A Canada and United States Delphi study. Arthritis Care & Research, 66(3), 411–423. 10.1002/acr.22164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford, H., Bagheri, N., Diminic, S., Enticott, J., Gao, C. X., Hamilton, M., Hickie, I. B., Le, L. K., Lee, Y. Y., Long, K. M., McGorry, P., Meadows, G., Mihalopoulos, C., Occhipinti, J., Rock, D., Rosenberg, S., Salvador-Carulla, L., & Skinner, A. (2023). Mental health systems modelling for evidence-informed service reform in Australia. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 57(11), 1417–1427. 10.1177/00048674231172113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2008). Trencin statement on prisons and mental health. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/108575.

- Young, A. M., Chung, H., Chaplain, A., Lowe, J. R., & Wallace, S. J. (2022). Development of a minimum dataset for subacute rehabilitation: A three-round e-Delphi consensus study. BMJ Open, 12(3), e058725. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]