Abstract

Ultracold atoms and molecules provide an unprecedented view into the role of quantum effects in chemical reactions. However, these same quantum effects make ultracold chemical reactions notoriously difficult to simulate. Contrary to conventional wisdom that ultracold systems necessitate quantum approaches, with classical mechanics offering a rough approximation at best, the past three decades have seen an explosion in classical, quasiclassical, and semiclassical approaches that yield near-exact results for ultracold systemsincluding in cases where today’s quantum methods would be computationally intractable. This review illustrates the power of these approaches with 30 years’ worth of numerical and experimental evidence. The review provides a comprehensive account of the successes of universal classical post-threshold laws for low-energy atomic and molecular scattering systems, as well as the cutting edge in quasiclassical approaches that unravel the ongoing controversy surrounding long-lived collision complex lifetimes in ultracold collisions. Special attention is placed on atomic systems where classical scaling laws hold directly at zero Kelvin, which underline the predictive power classical methods can offer even in the most extreme quantum chemical environments. The review culminates with a discussion of broader implications for classically inspired approaches to prototypically quantum chemistry in the second quantum revolution.

1. Introduction

In 2012, when Chemical Reviews published its Special Issue on ultracold molecules, − the field of ultracold chemistry was at its outset. The Special Issue placed a special focus on the preparation of molecules in the cold regime (below 1 K) − and the ultracold regime (below 1 mK). − Provisions were made for future applications for condensed matter theory and aspirations toward quantum chemistry. At the time, evidence of ultracold chemical reactions was restricted to reactant lossas in the groundbreaking measurement of molecular density decay in the ultracold 40K87Rb dimer reaction at just 300 nK by Ospelkaus, Ni et al. In the intervening years, there has been a “quantum leap” in ultracold chemistry.

A surprising outcome of such recent developments in ultracold chemistry − is classical, semiclassical, and quasiclassical mechanics is sufficient to simulate aspects of a wide range of cold and ultracold chemical reactions nearly exactly. This advancement provides an opportunity to develop computational tools that vastly reduce the cost of cold and ultracold simulations and aid interpretation of fundamental nonreactive and reactive collision processes. Section provides a comprehensive account of the numerical and experimental evidence in the past 25 years, including the ubiquitous ability of classical and semiclassical mechanics to closely reproduce quantum cross sections for atom–ion collisions at collision energies as low as 10 nK, the capability of classical Langevin capture theory to yield accurate reactive rate coefficients for triatomic collisions at collision energies as low as 10 nK, and the power of semiclassical mechanics to evidence a quasiuniversal quantum-to-classical crossover in dipolar collisions at collision energies as low as 7 pK. Note the lowest of these temperatures is 12 orders of magnitude colder than the interstellar medium. These findings go beyond theoretical results. Classical and semiclassical mechanics have been seen to closely agree, for example, with experimentally obtained cross sections on the order of 10 μK for Li + Ba+ collisions, 10 mK for H2 + HD collisions, and 0.1 K for H2 + He collisionsthe latter with a relative error of just 1%.

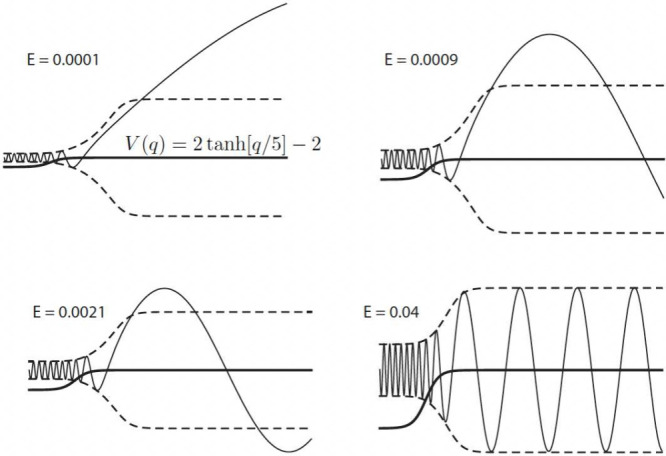

Recent rationales explain how semiclassical and classical mechanics can retain such accuracy in such a counterintuitive regime. Competing theories are detailed in Section , beginning with the foundational work of Gribakin and Flambaum, who found that semiclassical cross sections can hold when not a single oscillation of the scattering wave function fits in the potential well. − This argument is compared with the semiclassical Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin (WKB) criterion furthered by Julienne and Mies in 1989, Côté et al. in 1996, and Mody et al. in 2001 to pinpoint the onset of the quantum effects of quantum reflection and quantum suppression. Ultracold inferno theory, introduced in 2018, is also presented as a conceptual framework to indicate when not just semiclassical, but also classical treatment is expected to hold: namely, in the absence of quantum reflection and quantum interference. , These methods are placed in light of the controversy surrounding the true applicability of the WKB criterion and the related quantality condition and the question of whether these points of reference are sufficient to determine the “source” of quantum reflection effects. ,

The observation and justification of classical, semiclassical, and quasiclassical treatment of cold and ultracold collisions opens the door wide to applications throughout the field of chemistry. Section details how such advancements enable the derivation of novel semiclassical scaling laws for cross sections and rate coefficients, such as the semiclassical eikonal scaling laws of Bohn et al. for dipolar collisions currently underway in the laboratory, , as well as the development of techniques to rigorously extend existing quantum and classical cross section scaling laws to cover the whole of the collision energy region, as in the quantum threshold model of Quéméner and Bohn − and the quantum Langevin model of Gao. − Additionally, the review generalizes the semiclassical analogue of the Fermi golden rule approach of Mody et al. to derive semiclassical laws that apply to two-body collisions in not just three-dimensional, but reduced-dimensional collisions relevant to reactions in optical traps. ,− Section covers the novel perspective that rationales for classical and semiclassical behaviors in ultracold collisions offer on the origin of quantum-classical correspondence in scaling laws directly at zero collision energy in the renowned three-dimensional Coulomb potential and Wannier double ionization system, with implications for multiple ionization − and atomic fragmentation. , Section collects these universal scaling lawsspanning one- to N-dimensions and short-range to long-range potentialsto highlight and facilitate prediction of where classical and semiclassical predictions are expected to hold in a yet wider range of cold and ultracold collisions.

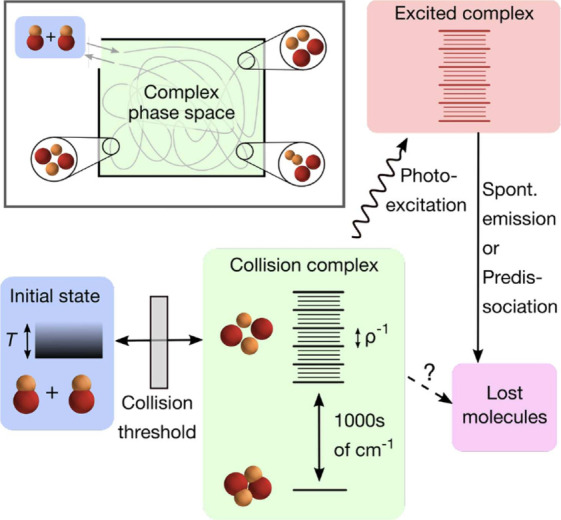

Section considers “sticky collisions”the mysterious disappearance of reactants even in ultracold collisions with no energetically accessible products. − Here a quasiclassical strategy based on the Rice–Ramsperger–Kassel–Marcus (RRKM) theory of unimolecular dissociation rates − has emerged as the method of choice. − This method has succeeded not least of all because simulation of such collision complexes with exact quantum mechanics ranges from highly computationally intensive for three-atom systems to computationally intractable for just four atoms. There remains a conundrumwhereas the quasiclassical and experimental collision-complex lifetimes for the 40K 87Rb + 40K 87Rb collision differ by a factor of just 2, , quasiclassical and experimental collision-complex lifetimes for 40K87Rb + 87Rb differ by 5 orders of magnitude ,, namely, a key area for further study.

Section provides an outlook for the future of classical, semiclassical, and quasiclassical methods in cold and ultracold molecules. The ability of classical mechanics to reap near-exact results opens the door to simulations of systems that are computationally intractable today, which includes systems of four atoms. Rigorous criteria for quantum-classical correspondence facilitate identification of not only where classical mechanics applies, but also where quantum treatment is essential, which is especially relevant today given the importance of accurate simulation of ultracold molecules proposed for quantum sensing − and quantum computing − technologies central to the second quantum revolution. Results at cold and ultracold temperatures also have implications for room-temperature chemistrythe exponential improvement in computational cost of classical simulations relative to quantum calculations provides a valuable complement to state-of-the-art data-science approaches to quantum mechanics, as well as the means to readily visualize detailed reaction mechanisms in terms of classical particles. And, the insight these findings offer into the border between quantum and classical worlds has implications for the wider field of near-threshold phenomena throughout chemistry and physics. We have moved far beyond the ultracold chemistry of 25 years ago, and this review provides a vision of what may be in store for the next 25 years.

2. Universal Classical and Semiclassical Scaling Laws in Ultracold Molecular Systems

2.1. Evidence of Quantum-to-Classical Crossover in the Cold and Ultracold Regime

To begin, some of the strongest support for classical treatment of ultracold collisions comes in the form of universal classical and semiclassical scalings near threshold in cold and ultracold scattering cross sections. ,− ,− Modern scattering calculations ,− ,− ,− ,− and experiments − ,,,,− confirm the prototypical picture of low-energy atomic and molecular cross sections: In the absence of resonances and bound states, − the Bethe–Wigner quantum threshold law , operates at the threshold of energetic accessibility (see Table ). , As the energy increases, a quantum-to-classical crossover appears. And, at the highest energies, the cross section asymptotically obeys (semi)classical post-threshold laws such as the classical capture theory laws of Langevin and Gorin , (modulo oscillations and resonances, see Table ). A schematic of this behavior is given in Figure .

1. Wigner Threshold Laws for Universal Scalings of Collision Cross Sections σ(k) as a Function of the Wavenumber k for Two-Body Collisions in Three Dimensions .

| Inelastic |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lim r→∞ V(r) | Endothermic | Exothermic | Depolarization | Elastic |

| 0 | ||||

| Ze2/r | exp(−2πμZe 2/(ℏ2 k)) | k–2 exp(−2πμZe 2/(ℏ2 k)) | k–2 exp(−4πμZe 2/(ℏ2 k)) | k –2 |

| –Ze 2/r | 1 | k –2 | k –2 | k –2 |

Scalings are shown for elastic collisions and inelastic collisions with positive threshold energy (endothermic reactions), negative threshold energy (exothermic reactions), and changes in angular momentum (depolarization events) and are given for short-range (lim r→∞ V(r)) and long-range (attractive Coulombic lim r→∞ V(r) = −Ze 2/r and repulsive Coulombic lim r→∞ V(r) = −Ze 2/r) potentials. Expressions are provided in terms of the reduced mass μ, charge number product Z, and initial and final angular momentum quantum numbers of the collision partners, where e is the electron charge and ℏ is reduced Planck’s constant.

2. Summary of Classical Langevin and Gorin , Laws for Scalings of the Capture Cross Sections σ L (E) with the Collision Energy E for van der Waals Potentials C n r –n of Order n .

| n | 3 | 4 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| σ L (E) |

The universal form of the scattering cross section, including its constant multiplicative factor, at low energy is provided. Reproduced table with permission from Robin Côté and Ionel Simbotin, Physical Review Letters, 121, 17, 173401, 2018. Copyright 2018 by the American Physical Society.

1.

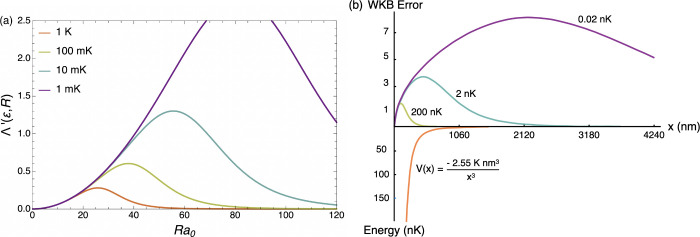

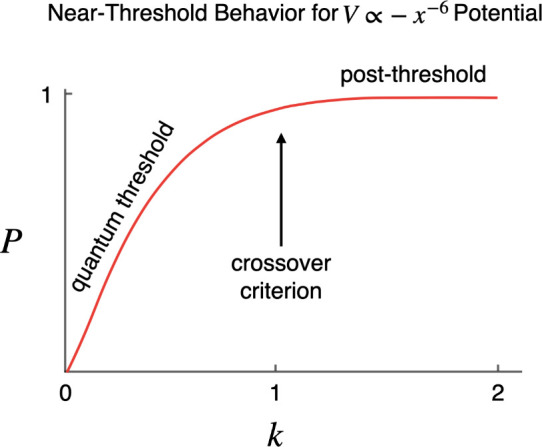

Prototypical framework for near-threshold cross sections as exemplified by numerical calculation of the transmission probability P in a one-dimensional V(x) ∝ – x –6 potential as a function of the wavenumber k. The transmission probability follows the quantum threshold law P ∝ k at threshold (k → 0) and crosses over (k ≈ 1) to the classical post-threshold law P = 1 at higher wavenumber (k → 1).

Numerical and experimental results show the quantum-to-classical crossover frequently appears in the cold to ultracold regime in molecular collisions. ,− ,,,− ,− Such low-energy quantum-to-classical crossovers imply that classical post-threshold laws for cross section and rate coefficient scalings are also highly accurate at extremely low collision energies. Several of the lowest-energy numerical examples of ultracold quantum-to-classical crossover and operation of classical post-threshold laws in the cold and ultracold regime are depicted in Figures –, with experimental counterparts in Figures – and additional details and related work below.

2.

Numerical evidence of quantum-to-classical crossover at ultracold energies approximately on the order of 10 nK in the averaged diffusion cross section ⟨σ d ⟩ (black line) and diffusion coefficient D (red line) for Na + Na+ collisions. Reprinted from Advances in Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics, 65, R. Côté, Ultracold atom–ion collisions, 67, Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier, based on reproduced figures with permission from R. Côté and A. Dalgarno, Physical Review A, 62, 1, 012709, 2000. Copyright 2000 by the American Physical Society.

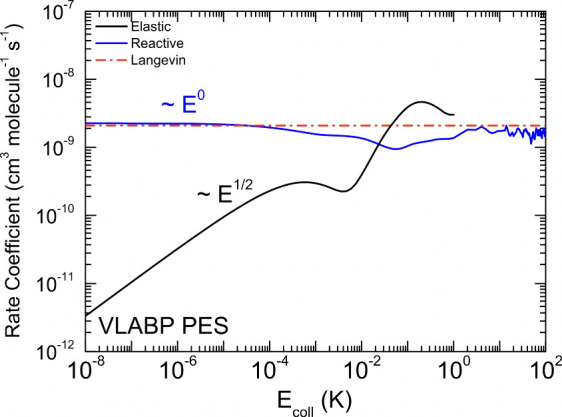

7.

Comparison of the reactive (blue) and elastic (black) rate coefficients to the classical Langevin rate coefficient (dashed-dotted red line) for D+ + H2 (v = 0, j = 0) indicates the reactive rate coefficient obeys the classical Langevin scaling down to the ultracold regime on the order of 10 nK. Reproduced from M. Lara and P. G. Jambrina, Cold and ultracold dynamics of the barrierless D+ + H2 reaction: Quantum reactive calculations for ∼R –4 long-range interaction potentials, Journal of Chemical Physics, 143 (2015) 204305, with the permission of AIP Publishing.

8.

Agreement between experimental total cross section measured at 30 μK (circles) with the classical Langevin (black line), scaled classical Langevin (thin dashed lines), quantum (colorful solid lines), and quantum thermalized (thick dashed lines) cross sections for (left) Li(2S 1/2) + Ba+ (5D 5/2) and (right) Li(2S 1/2) + Ba+ (5D 3/2). Quantum results are shown for competing nonradiative charge exchange (NRCE, yellow), nonradiative quenching (NRQ, red), and fine-structure quenching (FSQ, green) processes. Reproduced with permission from ref by Xing et al. CC BY 2024 IOP Publishing.

13.

Experimental evidence of cold quantum-to-classical crossover in He(23 P 2)/para-H2 (j = 0) collisions. The measured reaction rate constant (black points) obeys the classical Langevin post-threshold law (red dashed line) at collision energies as low as 0.8 K, with a quantum-to-classical crossover at energies on the order of 1 K for HD (j = 0) (gray points), compared to the p-wave barrier height (vertical dashed line). Reproduced figure with permission from Y. Shagam, A. Klein, W. Skomorowski, R. Yun, V. Akerbukh, C. P. Koch, and E. Narevicius, Molecular hydrogen interacts more strongly when rotationally excited at low temperatures leading to faster reactions, Nature Chemistry, 7, 921–926, 2015, Springer Nature. Reproduced with permission from SNCSC.

2.1.1. Numerical Evidence

2.1.1.1. Atom–Ion Collisions

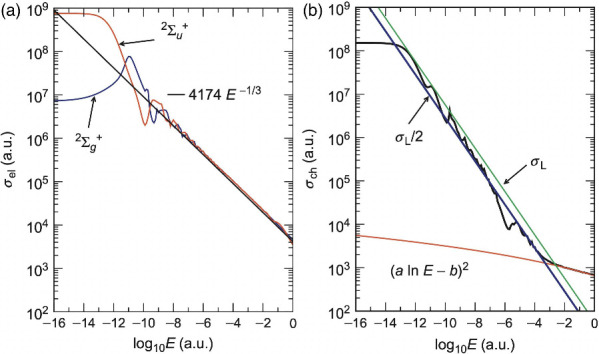

A number of authors have numerically identified quantum-to-classical crossover in hybrid atom–ion systems at collision energies well below 1 K. ,− ,,,, In 2000, Côté and Dalgarno identified a quantum-to-classical crossover at extremely low energies, as low as 10 nK, for collisions of Na + Na+. , As shown in Figures and , computed cross sections indicated that semiclassical treatment accurately modeled the quantum results at energies as low as 10–12 au (300 nK) for elastic and charge-transfer cross sections, with classical treatment accurately reproducing quantum results at energies as low as 10 nK for charge exchange cross sections. Côté and Dalgarno determined cross sections for ab initio potential energy surfaces and , with the potential approximated at short distances by an exponential wall and the potential approximated at long distances as V g,u (R) ∼ V disp (R) ∓ V exch (R) for dispersion term V disp (R) and exchange term V disp (R). Quantum scattering cross sections were determined from phase shifts calculated from the regular solutions of the corresponding partial wave equation. The quantum scattering cross sections were compared to both the classical Langevin formula and Massey and Mohr’s high angular momentum limit of Jeffrey’s semiclassical approximation. − Côté and Dalgarno recognized the underlying calculation strategies rest only on the neutral atom’s polarizability and mass, and thus are equally applicable to other alkali-metal hybrid atom–ion systemsand therefore low-energy quantum-to-classical crossover in atom–ion systems is expected to be widespread.

3.

Numerical evidence of quantum-to-classical crossover at ultracold energies approximately on the order of 10–12 au (300 nK) in (a) the elastic cross section of the state (blue line) and state (red line, semiclassical formula shown in black) and (b) the charge exchange cross section (black line, Langevin σ L shown in green, σ L /2 shown in blue, and higher-energy prediction in red) for Na + Na+ collisions. Reproduced from Advances in Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics, 65, R. Côté, Ultracold atom–ion collisions, 67, Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier, based on reproduced figures with permission from R. Côté and A. Dalgarno, Physical Review A, 62, 1, 012709, 2000. Copyright 2000 by the American Physical Society.

In 2001, Siska supported this finding, similarly identifying a quantum-to-classical crossover by collision energies of 10 μK in spin–orbit relaxation of Ne+ + He. Calculations were performed on an empirical potential energy surface based on spectroscopic measurements for the molecular ion and ab initio theory. Siska recognized that the required potential energy surface shares the form of an atom–homonuclear model potential, which facilitates rigorous quantum treatment according to the formalism of Reid, Arthurs, and Dalgarno. − The resulting coupled radial equations were then integrated numerically according to a variable step-size modified log-derivative method specifically for 4He + 20Ne+. Although the magnitude of the cross section usually remained <0.1% of the magnitude predicted by Langevin for the polarizability considered, the quantum scaling was seen to closely agree with the classical Langevin scaling down to collision energies in the quantum Wigner threshold regime less than 10 μK, well within the ultracold regime.

Likewise, in 2020, Pandey et al. demonstrated that total cross sections for the 7Li+ – 7Li collision agree with semiclassical and classical scalings at collision energies just above the ultracold regime. Pandey et al. developed ab initio potential energy curves for the Li2 electronic ground state X 2Σ g and first-excited state A 2Σ g according to the multireference configuration interaction (MRCI) method, which were used to determine the cross section quantum mechanically via direct numerical solution of the radial Schrödinger equation for individual partial waves and semiclassically according to the work of Côté and Dalgarno. The scattering cross sections for for all computed potential energy curves agreed with the semiclassical, classical Langevin, or scaled classical Langevin cross sections at collision energies at or greater than on the order of 10 mK.

In line with these results, in 2009, Zhang et al. identified quantum-to-classical crossover at 10 mK to 1 μK for inelastic and elastic 6Li + 7Li+ → 6Li+ + 7Li collisions, respectively. Zhang et al. considered cross sections computed for Born–Oppenheimer potentials with nonadiabatic couplings via the multiconfiguration self-consistent field (MCSCF) theory and multireference configuration interaction (MRCI) calculations. A comparison of quantum scattering cross sections and the semiclassical Langevin charge exchange model of Côté and Dalgarno , again demonstrated quantum-to-classical crossover from Wigner’s quantum threshold law beginning at 10–10 eV (1 μK), with semiclassical mechanics yielding accurate elastic scattering cross sections at energies higher than 10–6 eV (10 mK).

And, in 2011, Zhang et al. further showed that semiclassical mechanics reproduces quantum scattering cross sections at lower energy for charge exchange in atom–ion Be2 collisions. Zhang et al. again calculated ab initio quantum scattering cross sections on Born–Oppenheimer potentials with nonadiabatic couplings and compared the results to Côté and Dalgarno’s semiclassical Langevin charge model. Here, quantum-to-classical crossovers were identified in these results at 0.1 K to 0.1 mK.

Côté and Simbotin further extended the use of semiclassical mechanics to accurately predict ultracold atom–ion collision cross sections to temperatures up to 10 orders of magnitude colder (just above fK) in 2018, as shown in Figure . Côté and Simbotin published findings on quantum-to-classical crossover in the ultracold regime for resonant charge transfer of Yb + Yb+, spin flip of Na + Ca+ and 85Rb + 87Rb, and excitation exchange of – the last well below 1 pK. For Yb2 , quantum results were considered for V g /u potentials’ and states; for Na + Ca+, singlet A 1Σ+ and triplet a 3Σ+ states; , for 85Rb + 87Rb, for singlet X 1Σ g and triplet a 3Σ u states; and for Cs+ + Cs* (6p), for two Σ g/u and two Π g/u states. , van der Waals potentials of order four, four, six, and three approximated the asymptotic potentials, respectively. Semiclassical Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin (WKB) treatment − of the cross section for third-, fourth-, and sixth-order van der Waals potentials were directly related to the classical Langevin cross section to the expression for s-wave scattering; which yielded a modified Langevin scaling law for excitation exchange that incorporates the impact of quantum s-wave scattering above the prototypical Wigner quantum regime. This semiclassical modified Langevin scaling was again found to hold above a quantum-to-classical crossover that appears at energies on the order of approximately sub-mK to mK for spin-flip collisions of A Rb + B Rb for A = 85, 87 and B = 85, 87; μK to nK for resonant charge transfer in A Yb + A Yb+ for A = 168, 170, 172, 173, 174, 176; μK to nK for spin-flip collisions of Na + A Ca+ for A = 40, 42, 43, 44; and pK to fK in excitation exchange in A Cs + A Cs+ for A = 133, 132.75. These results, which encompass hybrid atom–ion systems for a variety of species of differing isotopes, both predict that quantum s-wave signatures are accessible experimentally via measurement of the semiclassical modified Langevin cross section and fulfill Côté and Dalgarno’s projection two decades prior , that their semiclassical treatment again applies broadly to alkali-metal hybrid atom–ion systems.

4.

Numerical example in which quantum-to-classical crossover appears at energies between on the order of 1 fK and 1 pK in excitation exchange in (a) and (b) in the same system with a rescaled fictitious mass m Cs = 132.75 that models an isotope effect. Images directly compare quantum numerical results (solid black line) with the classical Langevin cross section σ L (blue dot-dashed line), s-wave contribution (black dashed line), Langevin cross section s-wave contribution σ L sin2Δδ0 (solid blue line), and the s-wave-scattering-modulated Langevin cross section = . Reproduced figure with permission from Robin Côté and Ionel Simbotin, Physical Review Letters, 121, 17, 173401, 2018. Copyright 2018 by the American Physical Society.

In 2021, Hirzler and Pérez-Ríos demonstrated that quasiclassical and classical mechanics is also sufficient to accurately simulate another type of atom–ion collision processcharge exchange cross sections for low-energy Rydberg atom–ion collisions of Li* – Li+ and Li* – Cs+. Hirzler and Pérez-Ríos considered the interaction between the ionic cores and the Rydberg electron in resonant charge exchange according to two models: (i) a Coulomb potential and (ii) a pseudopotential that consists of a screened Coulomb interaction term and Rydberg electron–core electron interaction term. Scattering cross sections were determined quasiclassically according to a quasiclassical trajectory (QCT) approach ,− that treated nuclear dynamics classically and related the trajectories’ initial conditions and final positions to individual quantum states semiclassically. In order to examine the regions of parameter space well described by QCT and classical Langevin scaling, the number of partial waves required for accurate simulation of cross sections was determined, with the result that QCT remains accurate to energies as low as on the order of 1 K, and a classical Langevin framework holds to energies as low as on the order of that associated with Bose-Einstein condensation, namely, 100 nK.

2.1.1.2. Molecule–Molecule Collisions

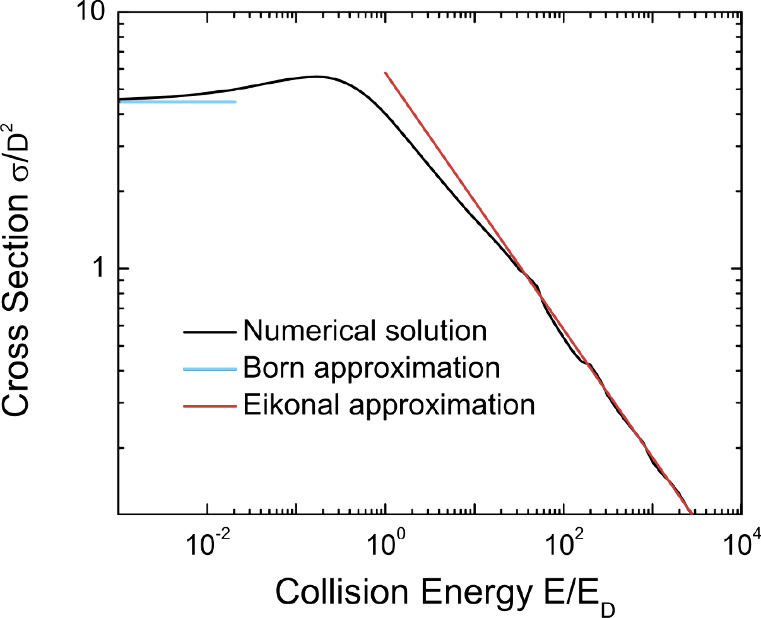

In 2009, Bohn, Cavagnero, and Ticknor found quasiuniversal quantum-to-classical crossover behavior also holds for dipolar collisions in the ultracold regime, of particular interest today given ongoing ultracold dipolar collision experiments. − ,,− In order to generate a widely applicable formulation for scattering cross sections, Bohn, Cavagnero, and Ticknor considered a potential dictated solely by two-body dipole–dipole interactions, with short-range physics and internal structure of the dipole neglected, as supported by previous work by Ticknor. , The resulting scattering cross section thus encompassed dipolar collisions in general, with the identity of the molecules of interest imparting on the resulting scattering cross sections only a length scale D = M⟨μ1⟩⟨μ2⟩/ℏ2 and energy scale E D = ℏ6/M 3 ⟨μ1⟩2 ⟨μ2⟩2, where M is the reduced mass and μ1 and μ2 are the dipoles. (Note that since both scales are dependent on the dipole moment, they are also dependent on the strength of any applied electric field.) Close-coupling results for this dipolar collision system were compared to the quantum Born approximation and the semiclassical eikonal approximation.

Semiclassical mechanics was found to be accurate throughout the cold collision regime to energies on the order of the energy scale E D , usually nK to μK. A quantum-to-classical crossover is therefore expected at 445 nK for OH, 83 nK for KRb, and 7 pK for LiCs for fully polarized molecules, as shown in Figure well within the ultracold regime. Bohn, Cavagnero, and Ticknor additionally recognized that in the quantum-to-classical crossover regime, universality falters and the cross section rests on lengths shorter than the length scale D, such that examination of the relevant energy regime may facilitate exploration of short-range physics and the intermolecular potential energy surface.

5.

Quantum-to-classical crossover of the total scattering cross section (black line) from the quantum Born approximation scaling (blue line) to the semiclassical eikonal approximation scaling (red line) occurs at characteristic energy E D = ℏ6/M 3 ⟨μ1⟩2 ⟨μ2⟩2 in distinguishable dipolar molecules, which corresponds to ultracold temperatures of 7 pK for LiCs, 83 nK in KRb, and 445 pK in OH. Reproduced with permission from ref by Bohn, Cavagnero, and Ticknor. CC BY 2009 IOP Publishing.

Dashevskaya et al. likewise showed that complex formation rates for a wide range of diatomic-diatomic/polyatomic ion collisions are amenable to quasiclassical treatment at temperatures above on the order of 1 to 10 mK in 2005and further showed that this behavior is expected to be widespread for molecular ion-neutral ion collisions. Dashevskaya et al. considered an asymptotic diatomic-ion interaction potential given by a sum of terms for an isotropic charge-induced dipole and an anisotropic charge-induced dipole with a charge-induced quadrupole. The total capture rate coefficient was determined in the zero-energy limit according to the quantum Bethe expression of Eltschka, Moritz, and Friedrich; in the intermediate energy range by direct solution of quantum coupled equations and the adiabatic channel classical (ACCl) approximation; , and in the high-energy limit by the classical Langevin rate. Quasiuniversal behavior of the capture cross section was observed, as shown in Figure , in which the total capture rate coefficient transitioned to its classical Langevin value at temperatures above T VLT, the characteristic temperature (termed Very Low Temperature) at which the de Broglie wavelength of relative motion equals the Langevin capture radius. This characteristic temperature was found to appear at T VLT = 1.49 · 10–4 K for collisions of diatomic nitrogen N2 with an ion X+ of mass 10 amu, and in the range 1.43 to 17.2 mK for a wide array of collisions of diatomic hydrogen isotopologues with molecular ions, as shown in Table . In 2016, Dashevskaya et al. confirmed accurate quantum capture rate coefficients for H2 (j = 0, 1) + H2 collisions approach the classical Langevin value on the order of 1 to 10 mK. These findings point to a broad ability of quasiclassical simulations to accurately model cold collisions of diatomic-molecular ion collisions in the cold regime below 1 K.

6.

Comparison of the total capture rate coefficient scaled to the classical Langevin rate for H2 (j = 0) collisions with any ionic partner indicate close agreement between the quantum (χ j=0 = k j=0/k L, solid line), ACCl (Χ j=0 , dashed line), quantum mechanically amplified ACCl (open circles), and Langevin rates (1.0) above the characteristic temperature TVLT. See ref for additional details. Adapted from E. I. Dashevskaya and I. Litvin, Rates of complex formation in collisions of rotationally excited homonuclear diatoms with ions at very low temperatures: Application to hydrogen isotopes and hydrogen-containing ions, Journal of Chemical Physics, 122 (2005) 184311, with the permission of AIP Publishing.

3. Characteristic Temperature T VLT for Transition to the Classical Langevin Capture Rate in Collisions of Diatomic Hydrogen Isotopologues with Selected Diatomic and Polyatomic Isotopologues .

| Molecular Ion | Neutral Molecule | TVLT [mK] |

|---|---|---|

| H2 | H2 | 17.2 |

| HD | 12.0 | |

| D2 | 9.70 | |

| HD+ | H2 | 12.0 |

| HD | 7.65 | |

| D2 | 5.86 | |

| D2 | H2 | 9.70 |

| HD | 5.86 | |

| D2 | 4.30 | |

| H3 | H2 | 12.0 |

| HD | 7.65 | |

| D2 | 5.86 | |

| H2D+ | H2 | 9.70 |

| HD | 5.86 | |

| D2 | 4.30 | |

| HD2 | H2 | 8.43 |

| HD | 4.90 | |

| D2 | 3.48 | |

| D3 | H2 | 7.65 |

| HD | 4.30 | |

| D2 | 3.00 | |

| CH3 | H2 | 5.53 |

| HD | 2.75 | |

| D2 | 1.73 | |

| C2H2 | H2 | 5.00 |

| HD | 2.38 | |

| D2 | 1.43 |

Note all temperatures considered occur in the cold regime well below 1 K. Adapted from E. I. Dashevskaya and I. Litvin, Rates of complex formation in collisions of rotationally excited homonuclear diatoms with ions at very low temperatures: Application to hydrogen isotopes and hydrogen-containing ions, Journal of Chemical Physics, 122 (2005) 184311, with the permission of AIP Publishing.

2.1.1.3. Atom–Molecule and Ion–Molecule Collisions

Likewise, numerous authors have identified ultracold quantum-to-classical crossover in triatomic collisions, including those relevant to experiments on three-body recombination (see refs , , , , , , , , , − , − ). In 2015, Lara et al. recognized that the classical Langevin scaling law accurately yields the reactive rate coefficient in the triatomic D+ + H2 (v = 0, j = 0) reaction in the ultracold regime as low as 10 nK, see Figure . Here, quantum calculations were performed according to the quantum reactive scattering method of Launey and Dourneuf on the potential energy surfaces of Velilla et al. and Aguado et al. Classical calculations were performed according to the classical Langevin model for long-range fourth-order van der Waals potentials both in its standard form and according to a numerical-capture statistical model that incorporates numerical values for centrifugal barrier heights to capture short-range behaviors, discrete summation over partial wave components, and a statistical factor to model the probability a collision complex decomposes into products. In its standard form, the classical Langevin model agrees with the quantum Wigner threshold law for long-range fourth-order van der Waals potentials, such that the classical Langevin model was found to accurately predict the E 0 scaling of the reactive cross section for D+ + H2 (v = 0, j = 0) collisions both in the low-energy and high-energy limits. Moreover, not only do the scalings agree, but the values of the cross sections also agree for this collision system (with the quantum result only 10% larger than the classical value), such that the cross section is predicted to vary by a multiplicative factor of just <10 from the classical value throughout the ultracold regime and extending beyond 10 orders of magnitude in energy.

In 2024, Karpa and Dulieu underlined the ubiquity of classical behavior in ultracold ion–molecule collisions according to a semiclassical Langevin scattering model. , The characteristic length and energy scales of s-wave collisions, defined by the position R * of the centrifugal barrier maximum E * associated with p-wave collisions in the absence of a Langer correction, were considered for an ion-neutral system with reduced mass μ and fourth-order van der Waals coefficient C 4

| 1 |

| 2 |

With the permanent electric dipole moments and static dipole polarizabilities of Vexiau et al., the characteristic scales were computed for collisions of 138Ba+ with bialkali molecules currently of interest in ultracold molecular experiments, revealing characteristic energies on the order of pK to nK, as shown in Table . Karpa and Dulieu suggested that this implies that even at the coldest temperatures at which molecular experiments have been performed as of 2024 (on the order of 10 nK), − ion–molecule collisions involving the species in Table would behave according to the classical Langevin capture model.

4. Characteristic Semiclassical Langevin Energy E * and Length R * Scales of the s-Wave Regime in 138Ba+ Ion-Neutral Rovibronic Ground-State Molecule Collisions, with Ion–Atom Collisions for Reference .

| Molecule | R* [10–6 m] | E* [nK] |

|---|---|---|

| LiCs | 25.9 | 0.00521 |

| NaCs | 40.1 | 0.00206 |

| LiRb | 16.2 | 0.0165 |

| LiK | 10.0 | 0.0703 |

| NaRb | 23.6 | 0.00711 |

| NaK | 14.2 | 0.0281 |

| KCs | 22.2 | 0.00644 |

| RbCs | 21.6 | 0.00614 |

| KRb | 6.21 | 0.0952 |

| LiNa | 1.12 | 7.86 |

| Rb | 0.295 | 52.3 |

| Li | 0.0694 | 8760. |

For all systems considered, the characteristic energy falls in the ultracold regime. Reproduced with permission from ref by Karpa and Dulieu. CC BY 2025 arXiv.

A great number of numerical studies have found classical, semiclassical, and quasiclassical mechanics are sufficient to accurately predict many triatomic scattering cross sections at energies above 0.1 mK in triatomic collisions (see refs , , , , , , , , , − , ). In 2000, Dashevskaya and Nikitin demonstrated that quasiclassical mechanics can be used to accurately determine s-wave vibrational relaxation cross sections for H2 (ν = 1, j = 0) + 4He → H2 (ν = 0, j = 0) + 4He in the ultracold regime above 0.1 mK. Dashevskaya and Nikitin expanded the Landau–Lifshitz method to determine quasiclassical matrix elements , to apply to states that are quasiclassical only in that their asymptotics obey the WKB approximation. This generalized Landau–Lifshitz method was applied to an exponential repulsive interaction and a Morse potential model and the results were compared to close-coupling cross sections. Quasiclassical results for the exponential repulsive interaction and for the Morse interaction closely agreed with quantum results just above 10–8 eV (0.1 mK) with the inclusion of quantum suppression effects. Dashevskaya et al. subsequently identified quantum-to-classical crossover in ion–molecule capture of H2 (j = 1) + Ar+ on the order of 0.1 mK and N2 (j = 1) + He+ on the order of 1 mK in 2004. Dashevskaya et al. treated the ion–molecule capture process in terms of a closed-state, structureless atomic ion and a rigid rotor molecule and found close agreement between rate coefficients computed with accurate quantum mechanics and the adiabatic channel classical approximation. , This agreement allowed for the accurate analysis of the capture process via classical treatment of the relative motion of the collision partners under an assumption of conserved intrinsic angular momentum projected onto the collision axis.

Similarly, in 2005, Quéméner et al. found that quenching rates in ultracold K + K2 collisions obey the classical Langevin model at energies higher than 0.1 mK. , An ab initio potential energy surface was generated for the potassium trimer 14 A 2 state via single-reference restricted open-shell coupled-cluster with single, double, and noniterative triple excitations [RCCSD(T)] − and employed the resulting surface in quantum close-coupling calculations with a body-frame democratic hyperspherical coordinate formalism at short atom–diatom distances , and the Arthurs–Dalgarno formalism at long atom–diatom distances. The resulting quantum total quenching rate coefficients reached their classical Langevin capture model values semiquantitatively past 0.1 mK. In 2017, Croft et al. also calculated elastic cross sections for s-wave K2 (v = 0, j = 0) + Rb collisions that exhibited a quantum-to-classical crossover on the order of 0.1 mK. Croft et al. evaluated quantum cross sections according to the atom–diatom scattering method of Pack et al. , and observed a large number of fine resonances appearing above approximately 10 mK. Although not explicitly discussed with reference to the classical post-threshold law in the work, resonances are visible beyond the energy at which the cross section begins to deviate from the threshold regime associated with E 0 quantum scaling in the energy range beyond 0.1 mK.

And, likewise, in 2016, Stoecklin et al. found that quantum vibrational quenching cross sections agree with the classical Langevin capture scaling at collision energies above 1 mK for the collision of Ca and BaCl+. Stoecklin et al. created an analytic potential energy surface for the electronic ground state 1 A′ via ab initio calculation at the coupled cluster singles, doubles, and perturbative triples [CCSD(T)] level of theory and employed both the close-coupling method and quantum defect theory − to determine the cross section quantum mechanically. The classical Langevin rate was computed and used to determine a statistical capture rate constant according to the method of Lara et al. Additionally, results were compared to the experimental data of Campbell et al. on the order of 10 to 100 mK. Both the experimental and quantum close-coupling vibrational quenching rate coefficients were found to obey the classical Langevin scaling on the order of 10 to 100 mK. Likewise, quantum defect theory universal loss rate coefficients were found to agree closely with the classical Langevin law (modulo oscillations) at energies on the order of 10 nK and above, and despite discrepancies at energies below one mK, was consistent with the experimental data and close-coupling calculations at energies above one mK.

Additional studies identify triatomic collisions in which classical post-threshold laws operate at collision energies above 10 mK. ,, In 2005, Cvitaš et al. found that classical post-threshold laws hold for the total inelastic rate coefficient of Li + Li2 collisions above 10 mK. Cvitaš et al. considered an ab initio global potential energy surface for Li3 computed via all-electron coupled-cluster theory. To determine scattering cross sections, the scattering S matrix was determined through wave function matching at the boundary of an inner region, where the wave function is determined through propagation of coupled equations in a diabatic-by-sector basis, and an outer region, where the wave function is determined according to the Arthurs–Dalgarno formalism. Comparison of the resulting quenching rates to the classical Langevin rate coefficient for vibrational quantum numbers v = 1, 2 indicated semiquantitative agreement for bosonic and fermionic Li. It was noted that the same Langevin rate coefficient holds for other spin-polarized state alkali atom–diatom inelastic rates in the post-threshold regime, which Cvitaš et al. predict to occur at or above 6.86 mK for Na, 1.89 mK for K, 0.537 mK for Rb, and 0.235 mK for Cs. In a similar spirit, in 2023, Morita et al. demonstrated that numerical quantum reactive and elastic cross sections obey classical post-threshold laws above 10 mK for Li + NaLi(ν = 0, j = 0) → Li2 + Na. Morita et al. considered an ab initio potential energy surface for the 14 A′ state of NaLi2 calculated according to the multireference configuration interaction (MRCI) method , and performed accurate quantum reactive scattering calculations with the adiabatically adjusting principal-axis frame hyperspherical (APH) coordinates method of Pack et al. , Examination of the reactive and elastic cross sections as a function of the collision energy evidence a rate law change consistent with quantum-to-classical crossover on the order of 10 mK and below for quantum numbers J = 0, 1 for both even and odd parity.

Beyond classical and semiclassical mechanics, beginning in 2019 Pérez-Ríos et al. also identified that QCT was valid for the determination of vibrational quenching cross sections of BaRb+(v) + Rb at energies above 1 mK. ,, In 2019, Pérez-Ríos considered interaction of spin-polarized Rb atoms in terms of Strauss et al.’s empirical triplet a Σ u potential and interaction of Ba+ – Rb according to a generalized Lennard-Jones potential that behaves asymptotically as a fourth-order van der Waals potential. QCT was again calculated with nuclear dynamics treated according to classical mechanics with initialization of trajectories and identification of final trajectories as individual quantum states treated according to the semiclassical quantization rule. The scaling of the vibrational quenching cross section was found to be consistent with the classical Langevin capture model scaling where the molecule was initialized in vibrational states v = 187–195 with angular momentum j = 0 for collision energies at and above 1 mK, with discrepancies for higher initial vibrational states. In 2021, Mohammadi et al. subsequently found that quasiclassical mechanics agrees with the classical Langevin value for BaRb+ (v)+ Rb for (2)1 Σ+ and (1)3 Σ+ vibrational relaxation cross sections. Mohammadi et al. employed QCT to simulate the collision, as in Pérez-Ríos’ 2019 approach, using a pairwise additive ground-state potential with a Rb2 interaction given by Strauss et al. and generalized Lennard-Jones potentials for both Ba+ – Rb and Ba – Rb+. The vibrational relaxation cross section from QCT was shown to be near the Langevin value for vibrational quantum numbers v = 5–16 for all collision energies studied, namely in the range of 1 to 100 mK. And, in 2024, Koots and Pérez-Ríos revisited the RbBa+ + Rb collision, now with the use of a Lennard-Jones potential to represent the triplet a Σ u state of Rb2 with QCT performed with their Python Quasi-Classical Atom-Molecule Scattering (PyQCAMS) package. These results confirmed quenching cross sections in agreement with the classical Langevin capture model at 20 and 100 mK for v = 187–195, with closest agreement for the lower vibrational quantum numbers. Over the years 2014 to 2021, Pérez-Ríos et al. have further employed a classical model based on a dynamical Langevin approach to determine classical ultracold threshold laws in a wide array of literature on three-body recombination ,,,, for which Dieterle et al. have experimentally confirmed the presence of Langevin capture dynamics for inelastic three-body collisions of individual ionic impurities in high-density rubidium Bose–Einstein condensates and Stevenson et al. have experimentally observed close agreement between NaCs three-body loss rates for varied field detunings and Rabi couplings across temperatures of 100 to 500 nK. ,,

2.1.2. Experimental Evidence

The aforementioned numerical evidence predicts quantum-to-classical crossover in the cold to ultracold regime for a broad range of atom–atom, atom–ion, molecule–molecule, and atom–molecule collisions. ,,,,,− ,− ,, Fortunately, in the past 15 years, experiment has supported these numerical predictions with flying colors. − ,,,− ,,,− A wide variety of experimental setups, including optical and/or radio-frequency traps ,,,,,, and merged supersonic beams, ,,, have reliably produced observations in keeping with classical and semiclassical predictions for disparate atomic and molecular processes including quenching, , charge exchange, ,, photofragmentation, , and atom–ion/molecule capture. ,,,

2.1.2.1. Atom–Atom and Atom–Ion Collisions

In 2024, Xing et al. found that total cross sections for Li(2S 1/2) + Ba+ (5D 5/2) and Li(2S 1/2) + Ba+ (5D 3/2) at 30 μK are consistent with scaled classical Langevin cross sections both in experiment and quantum numerics, as shown in Figure . This finding further supports the ability of classical mechanics to accurately describe many atom–ion collisions in the ultracold regime. To measure the cross sections experimentally, Xing et al. employed a combined all-in-one-spot ultracold atom apparatus with a segmented linear Paul trap. , 138Ba+ atoms were cooled to approximately the Doppler temperature of ∼354 μK and prepared in their 5 D 3/2 or 5 D 5/2 electronic state and 6Li atoms were cooled to approximately quantum degeneracy and prepared in their |f = 1/2, m f = −1/2⟩ state. The survival probability of Ba+ (52 D 3/2) or Ba+ (52 D 5/2) was recorded after various interaction durations, as well as the proportion of fine-structure quenching (FSQ), nonradiative charge exchange (NRCE), and nonradiative quenching (NRQ) events associated with distinct radial, spin–orbit, and rotational energy level transitions. Numerically, calculations were performed for LiBa+ potential energy curves computed via the CIPSI (configuration interaction by perturbation of a multiconfiguration wave function selected iteratively) package − with spin–orbit couplings computed via a quasidiabatic method. − Quantum cross sections were calculated in space-fixed frame according to two models: (i) a four-channel quantum scattering (FCQS) model of states in body-fixed frame with total electronic angular momentum Ω = 0+: 11Σ+ of Li(2s) + Ba+ (6s), 21Σ+ of Li+ + Ba(6s 2 1 S), and 31Σ+ and 13Π of Li(2s) + Ba+ (5d) (with coupling between atomic internal angular momentum and relative motional angular momentum neglected) and (ii) a multichannel quantum scattering (MCQS) model that additionally included Ω = 0–, 1 for 13Σ+ of Li(2s) + Ba+ (6s), as well as Ω = 0–, 1 for 23Σ+, Ω– = 0–, 1, 2 for 13Π, Ω = 1 for 11Π, Ω = 1, 2, 3 for 13Δ, and Ω = 2 for 11Δ of Li(2s) + Ba+ (5s). Results were thermalized according to a Maxwell–Boltzmann velocity distribution. For the FCQS model, the classical Langevin cross sections provided an upper bound for quantum cross sections. For MCQD, classical Langevin cross sections no longer serve as an upper bound for quantum cross sections locally due to the impact of shape resonances, but qualitatively provide an energy scaling of the quantum cross sections for FSQ, NRCE, and NRQ processes, often at energies well below 10 mK. Xing et al. found that experimental NRCE and NRQ cross sections at 30 μK, normalized to the computed classical Langevin rate, agree with both quantum calculations and the classical partial Langevin rate coefficient. Note quantum numerics suggest that elastic contributions are significant in the collision and are greater than the total Langevin rate coefficient, which suggests that the full capture assumption of the standard classical Langevin model does not hold.

In 2009, Grier et al. demonstrated agreement between experimental and classical Langevin rate coefficients also extends to multiple isotope combinations of resonant charge exchange for Yb+ + Yb at collision energies as low as 3 μeV (35 mK). Grier et al. employed a double-trap setup , in which neutral and singly charged atoms were trapped with a magneto-optical trap (MOT) and surface planar Paul trap, respectively, in a shared spatial volume. Isotope-selective ion fluorescence was used to measure signatures of charge-exchange collisions of αYb+ + βYb →αYb + βYb+ via tracking of αYb population decay. A pair of charge-coupled device (CCD) cameras were used to image the local atomic density n(r), which informed computation of the average atomic density colocated with the ions ⟨n⟩ = ∫p(r)n(r) dr for normalized ion distribution p(r) and subsequently the elastic rate coefficient K via a linear fit of the average atomic density ⟨n⟩ as a function of the measured ion decay rate constant Γ = 1/τ. For comparison, the semiclassical Langevin cross section was determined for an ab initio polarizability for the atomic ground state. , The rate coefficients were found to agree closely with the semiclassical Langevin value for collisions examined (172Yb+ + 174Yb, 172Yb+ + 171Yb, and 174Yb+ + 172Yb). The agreement extended from 3.1 μeV (36 mK) to 4 meV (46 K), namely over more than 3 orders of magnitude in energy. At 100 μeV (1.2 K) the semiclassical prediction was 5.8 · 10–10 cm3 s–1 with an experimental measurement of 6 · 10–10 cm3 s–1an absolute difference of just O(10–11 cm3 s–1).

And, in 2021, Ben-shlomi et al. identified classical Langevin scaling of quenching cross sections in 88Sr+ – Rb collisions at collision energies in the ultracold and cold regime as well. Ben-shlomi et al. measured the quenching cross section for the atom–ion collision with fine energy resolution on the order of 100 μK via the passage of optical-lattice-trapped Rb atoms across a radio-frequency-trapped 88Sr+ ion. Measured total quenching, electronic-excitation-exchange, and spin–orbit-change cross sections closely agreed with the Langevin cross section for all energies measured, which appeared in the domain of [0.2, 12] mK. In 2017, Saito et al. also experimentally measured classical Langevin scaling in cross sections for cold 6Li and 40Ca+ collisions. Saito et al. experimentally measured charge-exchange collision cross sections for the atom–ion mixture by trapping and cooling the two collision partners in distinct areas of a vacuum chamber and transporting the optically trapped atoms with an optical tweezer to be mixed with the radio-frequency-trapped ions. The resulting products of the collision were probed via measurement of the ions in their S 1/2, P 1/2, D 3/2, and D 5/2 states. The charge-exchange collision cross sections for the ions in a S 1/2, P 1/2, and D 3/2 mixture; the D 3/2 state alone; and the D 5/2 state alone agreed with the classical Langevin cross section for all energies measured, namely on the order of 1 mK to 1 K.

The extremely high accuracy possible with classical and quasiclassical treatment of cold molecules is especially evident in Kondov, Majewska et al.’s 2018 Sr2 photofragmentation experiments. , Kondov, Majewska et al. answered a decades-old quandary in the field of photodissociation − by experimentally observing and theoretically confirming a quantum-to-quasiclassical crossover at temperatures on the order of mK in photofragment angular distributions of diatomic strontium. , Above this crossover, at collision energies on the order of 0.1 to 1 mK, experiment, quantum, and semiclassical photofragmentation distributions were often nearly visually indistinguishable, as shown in Figure . In particular, there was near complete agreement between fully quantum, semiclassical WKB, and quasiclassical axial recoil limit photofragment distributions for the 0 u (−2,1,0) and 1 u (−2,1,0) states at just 48 mK, as is readily visible in Figure (right column center and bottom)a finding that evidences the ability of semiclassical and quasiclassical mechanics to accurately model not only collision cross sections, but photofragment distributions at cold temperatures for suitable molecular systems.

9.

Comparison of measured, quantum numerical, and semiclassical WKB numerical photofragment angular distributions of cold and ultracold strontium for initial 0 u (left column) and 1 u (right column top) states at energies 13 MHz (0.6 mK), 33 MHz (1.6 mK), 53 MHz (2.5 mK), 100 MHz (4.8 mK), and 300 MHz (14.4 mK) where each pair of rows corresponds to experiment (top) and quantum theory (bottom) with the exception of the final semiclassical WKB row. Strong agreement is also visible between between quantum theory, the semiclassical WKB approximation, and the quasiclassical axial recoil limit results at 1000 MHz (48 mK) for 0 u (right column center) and 1 u (right column bottom), and between quantum theory (solid lines) and the semiclassical WKB approximation (dashed line) for R (thick red line) and cos δ (thin blue line) above energies of approximately 1 mK (bottom center). Additional details in refs , . Reproduced figures with permission from I. Majewska, S. S. Kondov, C.-H. Lee, M. McDonald, B. H. McGuyer, R. Moszynski, and T. Zelevensky, 98, 4, 043404, 2018, Copyright 2018 by the American Physical Society, and from S. S. Kondov, C.-H. Lee, M. McDonald, B. H. McGuyer, I. Majewska, R. Moszynski, and T. Zelevensky, 121, 14, 143401, 2018, Copyright 2018 by the American Physical Society.

To identify this agreement, 88Sr atoms were cooled and photoassociated to produce Sr2 molecules with a temperature on the order of μK in a one-dimensional optical lattice trap, and photodissociation light pulses with a duration of 10 to 20 μs were employed, leading to a time-of-flight of 20 to 800 μs and an imaging pulse of 10 to 20 μs. The inverse Abel transform was used to convert the time-of-flight images to cross sections, which were subsequently averaged radially to produce the angular photofragment density. To identify the quantum-to-quasiclassical crossover, the photodissociation cross sections were simulated fully quantum mechanically according to Fermi’s golden rule on ab initio potentials, , semiclassically according to the WKB approximation, and semiclassically via an alternative model that treats molecular rotation classically. A quasiclassical model was also used to predict the angular distribution as a function of the initial molecular orientation probability density and the angular probability density of electric-dipole light absorption. ,, The quantum approach was found to accurately determine the cross sections at all energies considered (modulo potential energy surface corrections).

The quasiclassical model accurately yielded the angular distribution for 0 u (v = −4, J i = 1, M i = 0) molecules with parallelly polarized photodissociation light (P = 0) at the axial recoil limitthe energy above all potential energy barriers at which the photodissociation speed greatly surpasses rotation speeds, such that molecular fragments exit on the molecular axis, here just 14 mK. Likewise, the energy evolution of the amplitude R of photofragments in the J i – 1 angular momentum state and the phase difference δ obeyed the quasiclassical axial recoil limit R ≈ 1/2 above 5 mK and reached the semiclassical WKB (as well as semiclassical model) values at ≳ 1 mK, as depicted in Figure . Note quantum nuclear spin statistics and selection rules still can lead to discrepancies relative to quasiclassical results even at high energies, as Kondov, Majewska et al. observed, for example, for 1 u (−1,1,0) molecules subject to a projection quantum number selection rule ΔM = ±1 for perpendicular polarization that disallows odd angular momenta J. ,

Significant literature also points to the ability of classical and semiclassical approaches to reproduce quantum mechanical and experimental results for cold and ultracold atom–atom and atom–ion collisions in the presence of electromagnetic fields. ,− Initial demonstrations in the late 1980s and 1990s ,− indicated agreement between (semi)classical, quantum, and experimental analyses of atomic loss in optical traps with molecular states subject to laser-field dressing at collision energies on the order of 100 μK. − In the late 2000s and 2010s, classical and semiclassical methods to simulate cooling and trapping in radio frequency ion traps were found to be consistent with experiments. ,,− Notable among these advancements include Monte Carlo simulations based on classical time-evolution matrices by Devoe and classical trajectory simulations based on hard-sphere collisions and the polarization method of Cetina, Grier, and Vuletić by Meir et al. Devoe’s simulations closely reproduced experimental trapped ion lifetimes in noble buffer gases, including those of 136Ba+ in argon (theoretical value, 45 s; experimental value, 50 to 100 s) and krypton or xenon (theoretical value, < 0.1 s; experimental value, <5 s). ,, Likewise, Meir et al.’s simulations closely reproduced experimental values for the dependence of the ion temperature in the range of approximately 0.5 to 3 mK on the number of Langevin collisions for an 88Sr+ ion in a linear segmented Paul trap with ∼5 μK 87Rb in a cross dipole trap. Furthermore, all of Meir et al.’s classically simulated data points for the collision-number dependence of the ion temperature were found to be within one-sigma confidence bounds of the experimental mean. Contemporaneously, Wright et al. further supported the ability of (semi)classical mechanics to accurately model experimental loss rates of ultracold ions in traps with pulsed, frequency-chirped light close to resonance, ,− as their hybrid Landau–Zener excitation and Monte Carlo calculation based on classical atomic dynamics produced qualitative agreement with both experiment and fully quantum simulations. There are also studies in the literature that examine these systems from the perspective of semiclassical catastrophes and rainbows, , alternative classical models of cooling in electromagnetic traps, − and semiclassical models of quantum beats, which are interesting to watch as additional examples.

2.1.2.2. Molecule–Molecule Collisions

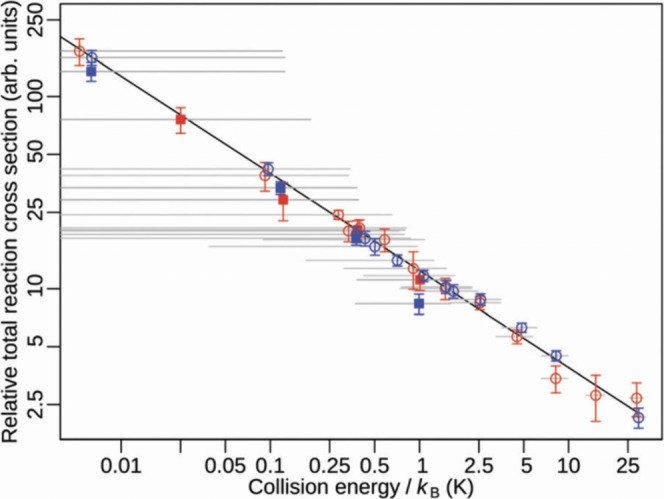

Just as predicted by quantum theory, Höveler et al. likewise experimentally observed classical capture rate coefficients on the order of 10 mK for molecular collisions of H2 + HD and on the order of 1 K for molecular collisions of H2 + D2, H2 + H2, and HD+ + HD, as shown in Figures , , and . ,, This finding represents classical behavior well within and on the cusp of the cold regime in molecule-cation collisions of a family of diatomic hydrogen molecule isotopologues, as presaged by Dashevskaya et al. The collision was studied experimentally via a merged supersonic beam setup: ,, Höveler et al. prepared ground rotational state J = 0 molecules (GS) in two pulsed supersonic beams, excited one beam’s molecules to a low-field seeking Rydberg–Stark state (Rg) with a rovibronic ground state ion core of a given principal quantum number, and merged the beams with a relative mean velocity of v rel = v Rg – v GS. The product ions were then measured with a time-of-flight mass spectrometer. The resulting relative total reaction cross section and rate coefficients for all collisions were compared to the classical Langevin capture model scaling, with H2 + H2, H2 + D2, and HD+ + HD collisions additionally compared against the theoretical rate coefficients of Dashevskaya et al. with appropriate mass scaling for isotopologues as required. ,,

10.

Close agreement between the classical Langevin law [exponent 0.5] and experiment [exponent – 0.505(14) from linear regression, black line] for the relative total reaction cross section in the H2 + HD collision. Experimental data are shown for time-of-flight windows of 5 μs (blue points) and 6 μs (red points), with vertical and horizontal gray bars indicating standard deviation of single data points and extent of probed collision energies, respectively. Used with permission of the Royal Society of Chemistry from The H2 + HD reaction at low collision energies: H3/H2D+ branching ratio and product-kinetic-energy distributions, K. Höveler, J. Deiglmayr, J. A. Agner, H. Schmutz, and F. Merkt, 23, 4 2021; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

11.

Quantum-to-classical crossover apparent in the cold regime for (top) and (bottom) . Gray points indicate individual measurements and black points measurements averaged within collision-energy ranges delineated with gray vertical lines, where vertical bars indicate one standard deviation and dashed lines indicate theoretical predictions. A transition is evident below 1 K between the quantum threshold value [blue arrow] and the classical Langevin capture model limit [red solid horizontal line]. Figure used with permission from Höveler, Deiglmayr, and Merkt from ref , CC BY 2021 Taylor & Francis.

12.

Cold quantum-to-classical crossover below 1 K visible in experimental rate coefficients for (a–c) H2 + H2 collisions [with para H2 (J = 0):ortho-H2 (J = 1) ratios of (a) 25:75, (b) 59(1):41(1), and (c) 80(1):20(1)] and (d) HD+ + HD collisions with 4.25% H2 and 4.25% D2 by volume. Theoretically computed contributions of individual molecules/molecular states are shown in color ([a–c]: ortho-H2 (J = 1) in red, para-H2 (J = 0) in blue, [d]: HD (J = 0) in blue, HD (J = 1) in red, H2 in green, D2 in orange), with experimental data and classical Langevin values presented as in Figure . Figure used with permission from Katharina Höveler, Johannes Deiglmayr, Josef A. Agner, Raphaël Hahn, Valentina Zhelyazkova, and Frédéric Merkt, Physical Review A, 106, 5, 052806, 2022, Copyright 2022 by the American Physical Society.

These experimental results showed clear agreement with classical Langevin capture model predictions both in terms of reaction cross sections and rate coefficients. ,, The experimental relative total reaction cross section for H2 + HD agreed with the classical Langevin capture law for all collision energies E coll measured50 mK to 30 K, encompassing 3 orders of magnitudewith a linear regression slope −0.505(14) in agreement with Langevin capture E coll with an absolute difference of O(10–3) (i.e., a relative discrepancy of just 1%). The experimental rate coefficients for H2 + H2 and H2 + D2 agreed with the classical Langevin capture scaling at higher energies above 3 K. Moreover, analysis of the deviation from classical Langevin behavior in the quantum limit below 1 K supported the theoretical prediction that a lower reduced mass would be associated with a wider collision energy range associated with deviations from Langevin behavior. , Namely, quantum theory predicts a 3.0 enhancement factor in the threshold rate coefficient’s rise between H2 and D2 (due to a product of the relative proportion of ortho and para spin isomers in the natural molecules and the reduced mass ratio for D2 and H2, ), which was supported by the experimental finding of an enhancement factor of 2.8(3), a difference of 7%. Additionally, the experimental branching ratio of H2 + D2 into H2D+ + D and HD2 + H products at 10 K of η = 0.341(15) and 1 – η agreed with the quasiclassical prediction of 0.3 at 0.01 meV (1.2 K), an absolute prediction error of O(10–2). Experimental rate coefficients for H2 + H2 and HD+ + HD were both consistent with reaching the classical Langevin capture model scaling by a collision energy on the order of 1 mK and consistent with Vogt and Wannier’s prediction over half a century prior: that ion-atom/molecule capture is enhanced by a factor of 2 at the quantum limit with respect to the Langevin rate. Finer collision-energy resolution remains a need to verify the precise enhancement factor.

2.1.2.3. Atom–Background Gas Collisions

In the same vein, for glancing and diffractive collisions of optically and magnetically trapped atoms and background gases, a wide array of authors have found close agreement between classical and semiclassical formulas ,,− and experimental data. , In 1988, Bjorkholm built on the classical small-angle scattering formula ,− to model trap loss due to elastic collisions of cold atoms with ambient background gas molecules as occurring due to the transfer of sufficient energy to expel the atom from the trap (namely, where the scattering angle exceeds the associated threshold). ,, This classical ejection rate yielded lifetimes that closely matched experimental values for sodium in varied conditions: 500 mK magnetic-molasses optical traps at pressure p (theoretical value, 2.2 · 10–8 s/p; experimental value, 2.0 · 10–8 s/p), 17 mK magnetic traps at pressure 10–8 Torr (theoretical value, 1.1 s; experimental value 0.83 s), and ∼5 mK optical traps at pressure 4 · 10–9 Torr (theoretical value, 2.2 s; experimental ∼ 1 s). Likewise, Arpornthip, Sackett, and Hughes’ 2012 classical loss rate for atoms in 1 K traps colliding with 300 K ambient gases closely agreed with experiment for sodium in hydrogen gas (theoretical value, 5.3 · 107 Torr–1 s–1; experimental value, 5 · 107 Torr–1 s–1), as well as for rubidium in argon gas (theoretical value, 2.3 · 107 Torr–1 s–1; experimental values 2.2 · 107 Torr–1 s–1 and 1.6 · 107 Torr–1 s–1). , Arpornthip, Sackett, and Hughes’ classical formula additionally concurred with the experimentally observed behavior of reduced dependence of the loss rate on the trap depth in the range [0.5, 2] K , with deviations observed for shallower traps where the classical approximation fails. ,,,

In the 2010s, Booth, Shen, Krems, and Madison similarly developed a semiclassical approach to trapped atom–background gas collisions that agrees with both quantum calculations and ultracold experiments to high accuracy. Booth, Shen, Krems, and Madison employed the minimum angle leading to trapped atom ejection and the total collision rate expression for a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution to produce a semiclassical loss rate Γloss = n⟨σtot v⟩(1 – p QDU) as a function of the gas density n, total cross section σtot, collision velocity v, and a novel probability of atomic retention in the trap p QDU. This probability p QDU was found to constitute a law of quantum diffraction universality in terms of the trap depth U, in which the coefficients β j and characteristic quantum diffractive energy U d are entirely independent of the van der Waals coefficient, mass, and dipole (ultimately leading to a universal formula for the gas pressure P = nk B T = Γloss (U)k B T/⟨σloss (U)v⟩ that has led to a search extending into the 2020s to establish the use of cold trapped atoms as pressure sensors ,− ,− ).

Booth, Shen, Krems, and Madison’s semiclassically predicted pressure agreed with experiment for magnetically trapped 87Rb atoms at <0.5 mK with helium, xenon, argon, molecular hydrogen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide. In particular, in the case of nitrogen, the associated pressure measurement reached as high as 0.5%-level agreement with the value for an ionization gauge calibrated by the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST). Similarly, in 2023, Kłos and Tiesinga further found agreement between quantum scattering results and the semiclassical small-angle approximation to the thermalized total elastic rate coefficient to within 10% for ultracold 7Li and 87Rb with 4He, 20Ne, 40Ar, 84Kr, 132Xe, and 14N2; ,− and, in 2024, Booth and Madison identified agreement between the quantum scattering results of Medvedev et al. and Kłos and Tiesinga and a semiclassical formula based on the Jeffreys–Born approximation for accurate total rate coefficients for collisions of cold 87Rb and 7Li with higher-mass background gases, in the case of trapped 7Li, with an error of less than 2% for krypton or xenon background gas and with an error less than the uncertainty range for argon or nitrogen background gas. These results for diffractive and glancing collisions thus support the use of semiclassical and classical methods to produce near-exact results in the cold and ultracold regimes for a wide array of atomic and molecular systems.

2.1.2.4. Atom–Molecule Collisions

We see the same high level of correspondence between (semi)classical methods and experiment in cold and ultracold atom–molecule collisions. With less than 1% error from classical predictions, Shagam et al. found in merged supersonic beam experiments that the rate constants for reaction of para-H2 (j = 0) and HD with He(23 P 2) obey the classical Langevin law to temperatures as low as on the order of 0.1 K, as shown in Figure further evidence of classical behavior in cold collisions of atoms with hydrogen molecule isotopologues. The experiment prepared supersonic beams of H2 or HD and He, excited He to the desired collision partner state, and employed a magnetic quadrupole guide to merge the resulting beams. The resulting beams were collided in a time-of-flight mass spectrometer such that the reaction rate could be found via detection of the atom at a microchannel plate. − For comparison, the scaling of the respective classical Langevin/Gorin scaling law was determined according to the order of the long-range van der Waals interaction, with the rate itself determined according to an estimated van der Waals coefficient. For collision of para-H2 with He(23 P 2), which features an asymptotic sixth-order van der Waals interaction, the sixth-order van der Waals coefficient was determined according to the H2 dipole polarizability of Bishop and Pipin and the sum-over-states expression for He(23 P 2) polarizability, dipole moments and transitions were calculated according to multireference configuration interaction calculations with single and double excitations (MRCISD), and potential energy surfaces were produced with the MOLPRO and DALTON packages. For collisions of He(23 P 2) with para-H2, the reaction rate constant scaled according to classical Langevin (Gorin) scaling to energies as low as 0.8 K, namely, in the unitary “black hole” limit in which reactants capable of surpassing the centrifugal energy barrier formed products with (near-)unit probability and the rate depended solely on the long-range interaction. The energy dependence of the reaction rate constant for collisions of He(23 P 2) with the HD isotopologue was also found to be consistent with the same classical Langevin scaling. Shagam et al. noted that the scaling law is independent of collision partner for a given specific van der Waals interaction, and suggested that the conformity of experimental reaction rates with universal Langevin scaling laws allows such laws to be used to probe long-range forces in cold collisions, including those that pertain to astrochemistry.

2.2. Rationales for the Accuracy of Classical and Semiclassical Approaches in the Cold and Ultracold Regime

Recent theoretical and experimental work (refs , , , , , , , , and − ) suggests a variety of rationales for why classical behavior of near-threshold physical and chemical systems is so ubiquitous beyond the classical limit of ℏ→0, high energy, and large quantum numbers ,,− ,,,, and how to predict what new ultracold molecular systems are expected to be accurately simulable with computationally efficient classical, semiclassical, and quantum-classical methods in the future.

2.2.1. Approach of Gribakin and Flambaum

Since 2020, a plurality of studies (see refs , , , , , − , − , − , − , − , − ) relate semiclassical behavior in cold and ultracold atomic and molecular collisions to the 1993 work of Gribakin and Flambaum, who discovered that semiclassical mechanics is often sufficient to accurately determine cross sections even for low collision energies typically associated with quantum mechanics. ,

Initially, Gribakin and Flambaum argued similarly that the semiclassical WKB approximation is expected to be accurate for scattering at low collision energies as long as there exist deep potential wells that permit the wave function to have a short oscillation period. This argument permits direct determination of the scattering length from the connection of the semiclassical wave function in the interior region to the quantum mechanical wave function in the exterior region at the region boundary. Specifically, Gribakin and Flambaum first assumed the semiclassical WKB solution holds in the interior beyond the classical turning point

| 3 |

and a quantum superposition state of Bessel and Neumann functions holds in the exterior asymptotic region. Matching the semiclassical WKB solution to the approximate analytic solution for an n th order asymptotic van der Waals potential U(R) ≃ −α/R n at a radius R = R * at which the semiclassical interior and quantum exterior solutions agree yielded the near-threshold scattering length in terms of the mean scattering length a̅

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

for the zero-energy semiclassical phase between the classical turning point and infinity Φ and the derived constant . As predicted by the rationale that semiclassics holds for deep potential wells, the hybrid semiclassical-quantum method gave a scattering length that agrees closely with the quantum result (namely, the extrapolation of the quantum result to zero Kelvin), as well as experimental data, for scattering from the deep Cs–Cs3Σ u potential (see Table )

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

where the potential is given by the sum of an exchange repulsion term (parametrized by B, α, and β) and a series of van der Waals terms (parametrized by C 6, C 8, and C 10 and modulated by a cutoff potential f c (R) that removes the van der Waals terms’ R = 0 divergence via imposition of a cutoff radius R c ). This scattering length in turn yielded a high-accuracy s-wave phase shift δ0 = −ak at wavenumber k, as well as the near-threshold scattering cross section σ = 4πa 2. Their subsequent development of a hybrid semiclassical-quantum formula for the effective range r e in terms of the aforementioned γ and ν = 1/(n – 2) along the same lines continued to support this initial deep potential well argument. Based on the same argument that the wave function can be determined by matching the semiclassical wave function in the interior region and the quantum wave function in the exterior region at the region boundary, Flambaum and Gribakin found that the semiclassical equation for the effective range r e

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

| 13 |

produced values of the effective range r e for the deep potentials of Li2, Na2, and Cs2 that agreed with quantum results with less than 1% error, again based on zero-energy semiclassical and quantum solutions. Note the special case result for n = 6 was simultaneously developed by Gao in the context of quantum defect theory. This effective range in turn gave high-accuracy s-wave phase shifts according to the definition of the standard effective range expansion

| 14 |

5. Gribakin and Flambaum’s Semiclassical Scattering Length a class (eq ) Closely Agrees with the Fully Quantum Mechanical Scattering Length a quant with Low Relative Error for Various Parametrizations of the Cs2 3Σ u Potential (eq ) .

| R c [au] | Rmin [au] | Umin [10–3 au] | aclass [au] | aquant [au] | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23.215 | 11.93 | –1.273 | 376 | 352.5 | 6.7% |

| 23.190 | 11.91 | –1.286 | 140 | 144.2 | 2.9% |

| 23.165 | 11.88 | –1.300 | 65 | 68.0 | 4.4% |

| 23.140 | 11.86 | –1.313 | –69 | –67.7 | 1.9% |

| 23.115 | 11.83 | –1.327 | 467 | 485.3 | 3.8% |

Results are shown for parameters B = 0.0016, α = 5.53, β = 1.072, C 6 = 6.5, C 8 = 1.1 · 106, and C 10 = 1.7 · 108 from ref , with stated cutoff radii R c resulting in shifted potential minima (R min, U min). The quantum result follows from extrapolation of the s-wave phase shift at k = 0.005 au (12 μK) to k = 0 au (zero Kelvin). Reproduced table with permission from G. F. Gribakin and V. V. Flambaum, Physical Review A, 48, 1, 546, 1993. Copyright 1993 by the American Physical Society.

The combination of these successes at first led Gribakin and Flambaum to first formally state that the scattering phase shift for deep potentials with asymptotic behavior U (R) ≃ −α/R n depends only on the derived constant γ and the semiclassical phase Φ where the potential well depth is much greater than the scattering energy. This implies the scattering phase shift in such cases is independent of energy, which they connect to the fact that deep in the potential well the potential may be substituted with a boundary condition that is independent of the energy.

However, what most closely relates to recent measurement of semiclassical behavior in cold and ultracold collisions is that Gribakin and Flambaum subsequently identified that, beyond their deep well hypothesis, their semiclassical method also succeeds for determination of the scattering length for a shallow H2 3Σ u potential. Gribakin and Flambaum rationalized the close agreement between semiclassical and quantum results for this shallow potential in terms of their derived formula and noted that the scattering length a for the system is significantly smaller than the average scattering length a̅, which ensures the scattering length is determined nearly entirely by the semiclassical phase Φ between the classical turning point and infinite radius. This finding points to a potentially much broader range of applicability of semiclassical mechanics near threshold in modern studies than originally theorized in which the semiclassical approximation can provide accurate results for shallow potentials, including potentials that support no wave function oscillations.

2.2.2. WKB Criterion

The WKB approximation has also been used to explain quantum-to-classical crossovers in the cold and ultracold regimes. These rationales, introduced by Julienne and Mies in 1989, Côté et al. in 1996, and Mody et al. in 2001, continue to be actively cited nearly three decades on (see refs , , , , − , − , , , − , , , , , , , , , − ).

Specifically, Julienne and Mies proposed that one may identify a broad range of energies at which semiclassical methods are accurate near threshold via careful consideration of the energies for which WKB holds at all interatomic distances. Building on prior work, − Julienne and Mies began with considering the deep connection between WKB and multichannel quantum defect theory (MQDT), which revealed that MQDT reference wave functions approach WKB wave functions at energies sufficiently beyond threshold, as follows: In MQDT, the fully quantum MQDT reference functions in the interior potential for the analytic matrix Y(E) at energy E, wavenumber k, and radius R assume the WKB-like form

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

| 18 |

for an uncoupled channel reference potential U 0 and channel state β; and quantum mechanically the reference wave functions for the scattering matrix S(E) assume the form

| 19 |

| 20 |