Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and optimal dosing of intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) as a tumor bed boost in combination with whole-breast irradiation (WBI) in individuals with breast cancer in China undergoing breast-conserving surgery (BCS).

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted on 217 female patients without metastatic disease who underwent BCS between May 2020 and December 2023 and received INTRABEAM IORT followed by postoperative WBI. Adjuvant therapies were administered as indicated. Evaluated outcomes included recurrence, disease-free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS), wound healing, and the incidence of radiodermatitis.

Results

The cohort ranged in age from 20 to 67 years, with a median age of 48 years. Among them, 18 patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to BCS. Molecular subtypes included Luminal A (25.8%), Luminal B (33.6%), hormone receptor-negative/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive (6.9%), hormone receptor-positive/HER2-positive (12.9%), and triple-negative (20.7%). IORT doses were 10 Gy (n = 189), > 10 to < 20 Gy (n = 9), and 20 Gy (n = 19). At a median follow-up of 20 months (range: 12–55 months), all patients were alive. Disease recurrence was observed in 2.3% (n = 5). Age younger than 45 years (p = 0.044) and tumor size exceeding 2 cm (p = 0.040) identified as independent risk factors of recurrence. The 1-year and 2-year DFS rates were 99.1% and 98.2%, respectively. Most patients (95.4%) achieved complete wound healing within four weeks. Delayed wound healing exceeding two months occurred more frequently among those who received 20 Gy (15.8%) compared to those who received 10 Gy (2.6%) or > 10 to < 20 Gy (0%) (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The combination of IORT and WBI demonstrated favorable safety and efficacy profiles in individuals with breast cancer in China undergoing BCS. Younger age and tumor size > 2 cm were associated with increased recurrence risk. An IORT dose between 10 and 20 Gy (including 10 Gy), was determined to be optimal, as a 20 Gy dose was associated with increased wound complications without providing survival benefits. Further research is warranted to explore risk-stratified dosing strategies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12957-025-03958-0.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Breast-conserving surgery, Intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT), Tumor bed, Whole breast irradiation (WBI)

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide, with incidence rates in China continuing to rise over recent decades [1, 2]. For individuals with early-stage disease, breast-conserving surgery (BCS) combined with adjuvant whole-breast irradiation (WBI) is the standard treatment approach. This strategy consists of two key phases: achieving complete tumor resection with histologically negative margins through BCS, followed by postoperative radiotherapy to eliminate residual microscopic disease. Current evidence indicates that WBI reduces the risk of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR) by approximately 65 to 70%, contributing to significant improvements in locoregional control, distant metastasis prevention, and overall survival [3–5].

The conventional fractionation regimen for WBI involves delivering 45 to 50 Gy to the entire breast at 1.8 to 2.0 Gy per fraction over five weeks, typically followed by a sequential tumor bed boost of 10 to 16 Gy administered over 5 to 8 fractions. Although this approach has demonstrated clinical efficacy, it has notable limitations, including the prolonged five-week treatment duration and challenges in accurately localizing the tumor bed. Despite intraoperative placement of titanium clips to mark the resection cavity, postoperative anatomical changes—such as tissue remodeling, seroma evolution, and adipose tissue displacement—often result in geographical miss during radiation planning [6]. These factors may contribute to the reported 5 to 9% incidence of IBTR observed in long-term follow-up studies, with most recurrences occurring within or adjacent to the original tumor bed [4, 5, 7–11].

Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) has emerged as a promising approach to overcoming these limitations. This technique offers several advantages: (1) Immediate single-fraction irradiation during surgery eliminates delays associated with postoperative radiation; (2) Direct visualization of tumor cavity boundaries improves spatial accuracy, reducing the risk of geographical miss; (3) Displacement of healthy tissue intraoperatively facilitates protection of organ-at-risk (OAR); and (4) Hypofractionated delivery may provide potential radiobiological benefits. Studies conducted predominantly in non-Chinese populations have reported favorable outcomes when IORT is used as a tumor bed boosts in conjunction with reduced-dose WBI. However, critical knowledge gaps remain regarding its clinical utility in Chinese patients [12]. Specifically, there is a lack of reliable data on therapeutic efficacy, toxicity profiles, and optimal dosing strategies for patients in China, who typically have distinct breast anatomy and smaller average tumor cavity volumes. The aim of this study is to evaluate the oncological outcomes and safety profile of IORT used as a tumor bed boost in combination with WBI among patients with breast cancer in China and to establish evidence-based dosing strategies tailored to this population.

Materials and methods

Patients and treatment

A total of 231 female patients with non-metastatic breast cancer underwent IORT at the center between May 2020 and December 2023. After careful screening, only 217 patients met the criteria and were included in this retrospective study.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) females aged ≥ 18 years with pathologically confirmed unilateral breast cancer; (2) candidates for BCS with strong preference for breast preservation, unifocal tumor ≤ 3 cm (or 3–5 cm if feasible based on breast volume), and negative surgical margins (≥ 1 mm); (3) completion of planned treatment: BCS with either sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary lymph node dissection + IORT + postoperative WBI. Patients who did not receive WBI due to disease progression, death before planned WBI, or physician-determined contraindications (e.g., wound complications) remained eligible for analysis. Patients with metastatic disease, prior thoracic radiotherapy, or incomplete treatment records were excluded.

IORT was delivered to the tumor bed using the INTRABEAM system PRS 500 (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), a mobile 50 kV low-energy X-ray radiotherapy system. The IORT technique and dosing regimen adopted in this study were primarily based on established international protocols [12]. Previous studies have not established a consensus on the optimal tumor bed boost dose for IORT, with reported doses typically ranging between 8 and 21 Gy. We administered five dose levels: 10 Gy, 14 Gy, 16 Gy, 18 Gy, and 20 Gy, which were classified into three groups: low dose (10 Gy; n = 189), intermediate dose (10–20 Gy; n = 9), and high dose (20 Gy; n = 19). The prescribed dose at 0 mm depth on the applicator surface and was designed to cover the tumor bed, which encompassed the former tumor site plus a 1–2 cm radial margin. Tube diameters ranged from 25 mm to 40 mm, depending on tumor size, and spherical applicators were utilized. WBI was initiated within seven months postoperatively. A total dose of 45 to 50.4 Gy was delivered in 25 to 28 fractions using tangential field techniques. Neoadjuvant systemic therapies were permitted, while adjuvant systemic treatments, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and endocrine therapy, were administered as indicated.

Follow-up and endpoints

Patients were assessed at three-month intervals during the first two postoperative years after surgery and every six months thereafter. Clinical and pathological data, treatment outcomes, and adverse effects were recorded, including the incidence of locoregional or distant recurrence, disease-free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS), postoperative wound healing time, and radiation-induced dermatitis following WBI. Additionally, factors influencing treatment efficacy and adverse reactions were analyzed.

DFS and OS were calculated from the date of the initial pathological diagnosis to the occurrence of cancer recurrence or all-cause mortality. For patients without documented disease progression or mortality, data were censored at the last follow-up (December 31, 2023). Treatment efficacy was assessed using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1), and acute radiation dermatitis severity was graded according to the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) grading system [13, 14].

Ethical approval

was obtained by the institutional ethical review committee (Approval Number: CZLS2024189-B). Due to retrospective nature of the evaluation, the need for informed consent was waived.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline patient characteristics. Associations among categorical variables were evaluated using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software (version 15.1; StataCorp).

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 217 patients were included in the final analysis. Of these, 18 received neoadjuvant chemotherapy before BCS, while the remaining did not. All patients completed the planned treatment protocol, except for one case of poor wound healing, one local recurrence before WBI, and one patient who discontinued treatment after receiving 15 WBI sessions due to personal reasons.

The age of the cohort ranged from 20 to 67 years (median: 48 years). Histopathological evaluation identified invasive ductal carcinoma in 208 cases (95.9%), special subtypes of invasive carcinoma in 3 cases (1.4%), and non-invasive breast neoplasms in 6 cases (2.8%). Molecular subtyping showed the following distribution: Luminal A (56 cases, 25.8%), Luminal B (73 cases, 33.6%), HR-negative/HER2-positive (15 cases, 6.9%), HR-positive/HER2-positive (28 cases, 12.9%), and triple-negative (45 cases, 20.7%). IORT doses were classified into three groups: low dose (10 Gy; n = 189), intermediate dose (> 10–<20 Gy; n = 9), and high dose (20 Gy; n = 19). Details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline clinicopathological characteristics of patients

| Variable | Patients, n = 217 |

|---|---|

| Age (median-range) | 48 (20–67) |

| < 45 years | 130 (83.3%) |

| ≥ 45 years | 26 (16.7%) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0–1 | 215 (99.1%) |

| 2 | 2 (0.9%) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 18 (8.3%) |

| No | 199 (91.7%) |

| Histologic subtype | |

| invasive ductal carcinoma | 208 (95.8%) |

| special types of invasive carcinoma | 3 (1.4%) |

| non-invasive breast neoplasms | 6 (2.8%) |

| Nottingham grade (n = 211, for invasive carcinoma) | |

| uncertain | 13 (6.2%) |

| Grade 1–2 | 131 (62.1%) |

| Grade 3 | 67 (31.7%) |

| Molecular subtype | |

| Luminal A | 32 (20.5%) |

| Luminal B | 101 (64.7%) |

| HR-negative/HER2-positive | 10 (6.4%) |

| HR-positive/HER2-positive | 2 (1.3%) |

| Triple-negative | 2 (1.3%) |

| TNM Stage at initial diagnosis | |

| uncertain | 34 (15.7%) |

| I | 85 (39.2%) |

| II | 98 (45.1%) |

| T at initial diagnosis | |

| uncertain | 20 (9.2%) |

| 1 | 110 (50.7%) |

| 2 | 87 (40.1%) |

| N at initial diagnosis | |

| uncertain | 14 (6.4%) |

| Negative | 151 (69.6%) |

| Positive | 52 (24.0%) |

| IORT dose | |

| low-dose (10 Gy) | 189 (87.1%) |

| intermediate-dose (> 10–<20 Gy) | 9 (4.1%) |

| high-dose (20 Gy) | 19 (8.8%) |

| Wound healing time after IORT | |

| ≤ 4 weeks | 207 (95.4%) |

| 4–8 weeks | 2 (0.9%) |

| > 8 weeks | 8 (3.7%) |

| Acute radiation dermatitis after WBI | |

| Grade 1–2 | 216 (99.5%) |

| Grade 3 | 1 (0.5%) |

Efficacy outcomes

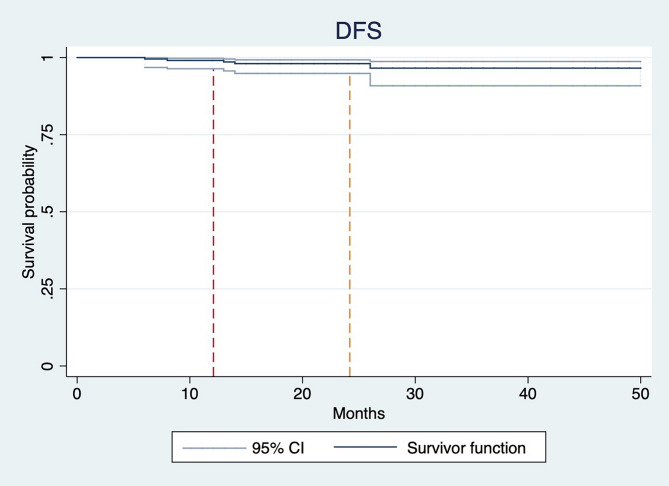

By the final follow-up in December 2024, all patients remained alive, with a median follow-up duration of 20 months (range: 12–55 months). The estimated 1-year and 2-year DFS rates were 99.1% and 98.2%, respectively, however findings should be interpreted with caution due to the relatively short follow-up period and immature data (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve for disease-free survival

Disease recurrence, including locoregional and distant metastasis, was observed in 5 patients (2.3%). Two patients developed bone metastases at 8 months and 26 months following diagnosis, respectively, while liver metastasis was identified in one patient at 14 months. Local recurrence was documented in two cases, both restricted to the tumor bed region, defined as the surgical site and the surrounding 2 cm area. These local recurrences occurred earlier than distant metastatic events, arising at 6- and 13-months post-diagnosis. Fisher’s exact test identified age below 45 years (p = 0.044) and tumor size greater than 2 cm (p = 0.040) as statistically significant predictors of disease recurrence (locoregional or distant). However, performance status (PS) score, histological grade, regional lymph node involvement, neoadjuvant therapy, Luminal subtype, and IORT dose were not significantly associated with recurrence outcomes. The findings are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The correlation between efficacy and categoric variables

| Variable | CR | PD (locoregional) | PD (distant) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.044 | |||

| < 45 years | 73 | 1 | 3 | |

| ≥ 45 years | 139 | 1 | 0 | |

| ECOG PS | 1.000 | |||

| 0–1 | 210 | 2 | 3 | |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Neo-chemotherapy | 0.354 | |||

| Yes | 17 | 0 | 1 | |

| No | 195 | 2 | 2 | |

| Histology | 0.591 | |||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 24 | 55 | ||

| Special types of invasive carcinoma | 12 | 34 | ||

| Non-invasive breast neoplasms | 3 | 4 | ||

| Nottingham grade | 0.153 | |||

| Grade 1–2 | 131 | 0 | 2 | |

| Grade 3 | 67 | 2 | 1 | |

| Molecular subtype | 0.225 | |||

| Luminal A | 56 | 0 | 0 | |

| Luminal B | 71 | 0 | 2 | |

| HR-negative/HER2-positive | 15 | 0 | 0 | |

| HR-positive/HER2-positive | 27 | 0 | 1 | |

| Triple-negative | 47 | 2 | 0 | |

| T at initial diagnosis | 0.040 | |||

| 1 | 110 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 87 | 2 | 2 | |

| N at initial diagnosis | 0.130 | |||

| Negative | 151 | 2 | 0 | |

| Positive | 52 | 0 | 2 | |

| IORT dose | ||||

| low-dose (10 Gy) | 185 | 2 | 2 | 0.247 |

| intermediate-dose (10 ~ 20 Gy) | 8 | 0 | 1 | |

| high-dose (20 Gy) | 19 | 0 | 0 |

Adverse reactions

Postoperative wound healing time

The majority of patients (207 out of 217, 95.4%) achieved wound healing within four weeks following surgery. Delayed wound healing (> 2 months) was observed in 8 patients (3.7%). Further analysis indicated a significant association between higher IORT doses (20 Gy) and delayed wound healing (p = 0.000). The incidence of delayed wound healing in the high-dose group (20 Gy) was 15.8%, whereas no cases were reported in the intermediate-dose group (> 10–<20 Gy), and the incidence in the low-dose group (10 Gy) was 2.6%. Additionally, the presence of diabetes mellitus (DM) was not significantly associated with prolonged wound healing.

Acute radiation dermatitis after WBI

Analysis of acute skin toxicity following WBI indicated that radiation dermatitis was primarily mild to moderate in severity, classified as grade 1 or 2. Only one patient (0.5%) experienced grade 3 dermatitis. Notably, this patient received low-dose IORT (10 Gy) and had no comorbidities, including DM, yet exhibited excellent wound healing post-IORT, with no observed delays.

Discussion

IORT has garnered attention for its precise targeting of the tumor bed, elimination of postoperative radiotherapy delays, and capacity to administer a single high-dose radiation fraction under direct visualization. Currently, two techniques are utilized: a linear electron accelerator or the INTRABEAM system, which employs 50 kV low-energy X-rays with an undefined dose range of 8 to 21 Gy [13].

IORT can be applied using two main strategies. The first is a definitive strategy, in which IORT serves as a complete replacement for postoperative external beam radiotherapy. Findings from two phase III randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—the ELIOT study using electrons and the TARGIT-A study using low-energy photons—indicated higher local recurrence rates in the single IORT group compared to postoperative WBI [15–17]. Consequently, this method is currently recommended only for carefully selected patients with a very low risk of recurrence [18].

The second, more conservative approach integrates IORT as a tumor bed boost combined with postoperative WBI. In this context, IORT replaces the conventional external boost, offering the advantage of concomitant rather than sequential dose delivery, reducing treatment duration. Radiobiologically, this approach allows administration of more than double the equivalent dose to the tumor bed while ensuring precise targeting and minimizing geographical miss. Multiple studies have confirmed its efficacy and safety [12, 19–23].

A 2023 meta-analysis involving 3,219 patients demonstrated that an IORT boost combined with postoperative WBI was more effective than conventional radiotherapy following BCS in patients with early-stage breast cancer, particularly in reducing distant metastasis rates [12]. Subgroup analysis indicated that electron boosts were more effective than X-ray boosts. Additionally, cosmetic and safety outcomes were comparable between groups. However, several limitations were noted. Only one of the included studies was an RCT, follow-up durations varied widely (ranging from 4 to 6 months to a median of 12 years), and data specific to Chinese patients were lacking. Furthermore, the optimal intraoperative irradiation dose remains undetermined.

Based on these considerations, the present study provides comprehensive data on the efficacy and safety of IORT as a tumor bed boost combined with WBI among patients with breast cancer in China, with additional analysis focused on optimal dosing strategies.

The findings indicated a disease recurrence rate (both locoregional and distant) of 2.3%, with 1-year and 2-year DFS rates of 99.1% and 98.2%, respectively. All patients were alive at the time of follow-up. Among them, three patients (1.4%) developed distant metastases, while two patients (0.9%) experienced local recurrences, both confined to the tumor bed region (defined as the surgical bed and a surrounding 2 cm area). These outcomes are comparable to, or more favorable than, those reported in other populations treated with similar strategies [12, 19].

For instance, an Italian single-institution phase III randomized study compared intraoperative radiotherapy with electrons (IOERT) with external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) boost in early-stage breast cancer [19]. Between 1999 and 2004, 245 patients were randomized, with 133 receiving IOERT and 112 receiving EBRT. At a median follow-up period of 12 years, the in-breast true recurrence rates at 5 and 10 years were 0.8% and 4.3% after IOERT, compared to 4.2% and 5.3% after the EBRT boost (p = 0.709). Similarly, out-field local recurrence rates at 5 and 10 years were 4.7% and 7.9% for IOERT versus 5.2% and 10.3% for EBRT (p = 0.762). The DFS rates at 5 and 10 years were 91.4% and 84% in the IOERT group, compared to 90.6% and 80.9% in the EBRT group (p = 0.529). These results indicate that a 10 Gy IOERT boost during BCS achieves high local control rates without significant morbidity. Although IOERT was not significantly superior to the EBRT boost, it was shown to be non-inferior.

However, it is essential to acknowledge several limitations of the present study. The median follow-up duration in the study was relatively short at 20 months, necessitating extended follow-up to confirm long-term outcomes, including late toxicities and survival rates. Additionally, the inclusion of a subset of patients who received neoadjuvant therapy—typically presenting with more advanced disease—introduces heterogeneity within the study population. Third, the single-center nature of the study may restrict the generalizability of the findings to broader populations.

Despite these limitations, both the stratified analyses of disease progression risk (Table 2) and univariate DFS analysis (Supplementary Data) consistently identified age less than 45 years and tumor size greater than 2 cm as key predictors of treatment efficacy. Younger age, often linked to more aggressive tumor biology—such as a higher prevalence of hormone receptor-negative or HER2-positive subtypes—and larger tumor size, a well-recognized risk factor for both local recurrence and distant metastasis, were independently associated with poorer outcomes.

In contrast, no statistically significant associations were observed between treatment outcomes and factors such as PS score, histological grade, regional lymph node involvement, neoadjuvant therapy, Luminal subtype, and IORT dose (all p > 0.05). These findings emphasize the importance of risk stratification and personalized therapeutic strategies, particularly for younger patients and those with larger tumors.

Building on these results, a prospective clinical trial has been initiated to evaluate the feasibility of risk-stratified IORT dosing based on prognostic indicators such as age and tumor size. Preliminary data indicate the feasibility of this approach, with predefined dose ceilings below 20 Gy. However, further validation in larger cohorts with extended follow-up is necessary to establish reliable, evidence-based dosing guidelines.

One of the primary objectives of this study was to determine the optimal IORT dose for patients diagnosed with breast cancer in China, given the substantial variations in dose administration reported in previous studies [12]. The present findings indicated a delayed wound healing rate of 3.7%, with the highest incidence observed in the 20 Gy high-dose group (20 Gy: 15.8% vs. >10–<20 Gy: 0% vs. 10 Gy: 2.6%, p < 0.001). These results align with prior research indicating that higher radiation doses may compromise tissue repair mechanisms and elevate the risk of wound-related complications [24, 25]. For example, the Young Boost Trial conducted by Brouwers et al., investigated the effects of different boost doses (16–26 Gy) delivered via external photons, electrons, or interstitial brachytherapy in patients older than 50 years [24]. Patients in the high-dose group demonstrated significantly poorer cosmetic outcomes, with a strong association between fibrosis severity and cosmetic results.

Similarly, a German study involving 48 patients evaluated the effects of a 20 Gy IORT boost followed by WBI at a total dose of 46 to 50 Gy [25]. These findings indicated that early initiation of WBI following IORT (median: 36 days) was associated with a significant increase in late toxicity. Consequently, caution is advised when considering IORT doses ≥ 20 Gy, particularly in Chinese patients, as elevated doses did not yield substantial oncological benefits but were correlated with heightened risk of toxicity. Doses ranging from 10 to 20 Gy (including 10 Gy) appear to provide an optimal balance between efficacy and safety. A prospective clinical trial is currently underway to assess risk-adapted IORT dosing strategies, with predefined dose ceilings set below 20 Gy. The outcomes of this trial are expected to contribute to the refinement of evidence-based guidelines for individualized IORT dosing in patients with breast cancer in China.

Overall, the findings of this study hold several significant implications for clinical practice. First, the combination of IORT and WBI following breast-conserving surgery appears to be a safe and effective treatment approach for patients with early-stage breast cancer in China. Second, personalized treatment planning that considers patient age, tumor size, and additional risk factors is crucial for optimizing clinical outcomes. Third, caution is warranted when administering IORT doses of 20 Gy or higher, as these doses may increase the risk of wound complications without providing substantial oncological benefits. However, this study did not calculate BED due to ongoing controversy regarding the linear-quadratic (LQ) model’s validity for low-energy photon rays and single doses > 10 Gy, as well as uncertainties surrounding the optimal α/β ratio for breast cancer in single-fraction IORT [26–29].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate that IORT administered as a tumor bed boost following lumpectomy and WBI is a safe and effective treatment approach for patients diagnosed with breast cancer in China. This approach is associated with low recurrence rates, favorable survival outcomes, and an acceptable toxicity profile. Age younger than 45 years and tumor size exceeding 2 cm were identified as significant predictors of recurrence, underscoring the necessity of risk stratification and personalized treatment planning. An IORT dose range of 10 Gy to 20 Gy (including 10 Gy) appears optimal. Doses of 20 Gy or higher were associated with impaired wound healing without offering additional oncological benefits. These findings support the incorporation of IORT into clinical practice for patients with breast cancer in China while highlighting the importance of extended follow-up periods and further research to refine risk-stratified IORT dosing strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Figure 1. DFS stratified by age.

Supplementary Material 2: Supplementary Figure 2. DFS stratified by tumor size (T stage).

Abbreviations

- IORT

Intraoperative radiotherapy

- BCS

Breast-conserving surgery

- WBI

Whole breast irradiation

- IBTR

Ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence

- OAR

Organ-at-risk

- PTV

Planning target volume

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- OS

Overall survival

- RECIST v1.1

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1

- RTOG

Radiation Therapy Oncology Group

- PS

Performance status

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- DMR

Distant metastasis rate

- IOERT

Intraoperative radiotherapy with electrons

- EBRT

External beam radiotherapy

Author contributions

Jing Chen: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing– original draft. Xian Zhou: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing– original draft. Ke-Gui Weng: Conceptualization, Software. Qian-Qian Lei: Conceptualization, Software. Min Ying: Data curation, Formal Analysis. Yong-Zhong Wu: Conceptualization, Writing– review & editing. Ying Wang: Formal Analysis, Writing– review & editing. Xiao-Hua Zeng: Conceptualization, Writing– review & editing. Yan-Yan Long: Conceptualization, Software, Writing– original draft. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Funding

This study was funded by Technology Innovation Project funded by Science and Technology Bureau of Shapingba District, Chongqing (Grant Number: 2024146). The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted with approval from the Ethics Committee of Chongqing University Cancer Hospital (Approval Number: CZLS2024189-B). This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jing Chen, Xian Zhou these authors contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Xiao-Hua Zeng, Email: zxiaohuacqu@126.com.

Yan-Yan Long, Email: lonky_007@163.com.

References

- 1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 May-Jun;74(3):229–63. 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Han B, Zheng R, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, Chen R, Li L, Wei W, He J. Cancer incidence and mortality in china, 2022. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2024;4(1):47–53. 10.1016/j.jncc.2024.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, Davies C, Elphinstone P, Evans V, Godwin J, Gray R, Hicks C, James S, MacKinnon E, McGale P, McHugh T, Peto R, Taylor C, Wang Y, Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2087–106. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67887-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG), Darby S, McGale P, Correa C, Taylor C, Arriagada R, Clarke M, Cutter D, Davies C, Ewertz M, Godwin J, Gray R, Pierce L, Whelan T, Wang Y, Peto R. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9804):1707–16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61629-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, Jeong JH, Wolmark N. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233–41. 10.1056/NEJMoa022152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sedlmayer F, Rahim HB, Kogelnik HD, Menzel C, Merz F, Deutschmann H, Kranzinger M. Quality assurance in breast cancer brachytherapy: geographic miss in the interstitial boost treatment of the tumor bed. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;34(5):1133–9. 10.1016/0360-3016(95)02176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartelink H, Horiot JC, Poortmans PM, Struikmans H, Van den Bogaert W, Fourquet A, Jager JJ, Hoogenraad WJ, Oei SB, Wárlám-Rodenhuis CC, Pierart M, Collette L. Impact of a higher radiation dose on local control and survival in breast-conserving therapy of early breast cancer: 10-year results of the randomized boost versus no boost EORTC 22881– 10882 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(22):3259–65. 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.4991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A, Aguilar M, Marubini E. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1227–32. 10.1056/NEJMoa020989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faverly DR, Hendriks JH, Holland R. Breast carcinomas of limited extent: frequency, radiologic-pathologic characteristics, and surgical margin requirements. Cancer. 2001;91(4):647–59. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holland R, Veling SH, Mravunac M, Hendriks JH. Histologic multifocality of tis, T1-2 breast carcinomas. Implications for clinical trials of breast-conserving surgery. Cancer. 1985;56(5):979–90. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher ER, Anderson S, Redmond C, Fisher B. Ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence and survival following lumpectomy and irradiation: pathological findings from NSABP protocol B-06. Semin Surg oncol. 1992 May-Jun;8(3):161–6. [PubMed]

- 12.He J, Chen S, Ye L, Sun Y, Dai Y, Song X, Lin X, Xu R. Intraoperative radiotherapy as a Tumour-Bed boost combined with whole breast irradiation versus conventional radiotherapy in patients with Early-Stage breast cancer: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30(13):8436–52. 10.1245/s10434-023-13955-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) and the European organization for research and treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1341–6. 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00060-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veronesi U, Orecchia R, Maisonneuve P, Viale G, Rotmensz N, Sangalli C, Luini A, Veronesi P, Galimberti V, Zurrida S, Leonardi MC, Lazzari R, Cattani F, Gentilini O, Intra M, Caldarella P, Ballardini B. Intraoperative radiotherapy versus external radiotherapy for early breast cancer (ELIOT): a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(13):1269–77. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70497-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orecchia R, Veronesi U, Maisonneuve P, Galimberti VE, Lazzari R, Veronesi P, Jereczek-Fossa BA, Cattani F, Sangalli C, Luini A, Caldarella P, Venturino M, Sances D, Zurrida S, Viale G, Leonardi MC, Intra M. Intraoperative irradiation for early breast cancer (ELIOT): long-term recurrence and survival outcomes from a single-centre, randomised, phase 3 equivalence trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):597–608. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaidya JS, Joseph DJ, Tobias JS, Bulsara M, Wenz F, Saunders C, Alvarado M, Flyger HL, Massarut S, Eiermann W, Keshtgar M, Dewar J, Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, Sütterlin M, Esserman L, Holtveg HM, Roncadin M, Pigorsch S, Metaxas M, Falzon M, Matthews A, Corica T, Williams NR, Baum M. Targeted intraoperative radiotherapy versus whole breast radiotherapy for breast cancer (TARGIT-A trial): an international, prospective, randomised, non-inferiority phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9735):91–102. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60837-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaidya JS, Bulsara M, Baum M, Wenz F, Massarut S, Pigorsch S, Alvarado M, Douek M, Saunders C, Flyger HL, Eiermann W, Brew-Graves C, Williams NR, Potyka I, Roberts N, Bernstein M, Brown D, Sperk E, Laws S, Sütterlin M, Corica T, Lundgren S, Holmes D, Vinante L, Bozza F, Pazos M, Le Blanc-Onfroy M, Gruber G, Polkowski W, Dedes KJ, Niewald M, Blohmer J, McCready D, Hoefer R, Kelemen P, Petralia G, Falzon M, Joseph DJ, Tobias JS. Long term survival and local control outcomes from single dose targeted intraoperative radiotherapy during lumpectomy (TARGIT-IORT) for early breast cancer: TARGIT-A randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2020;370:m2836. 10.1136/bmj.m2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciabattoni A, Gregucci F, Fastner G, Cavuto S, Spera A, Drago S, Ziegler I, Mirri MA, Consorti R, Sedlmayer F. IOERT versus external beam electrons for boost radiotherapy in stage I/II breast cancer: 10-year results of a phase III randomized study. Breast Cancer Res. 2021;23(1):46. 10.1186/s13058-021-01424-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welzel G, Hofmann F, Blank E, Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, Hermann B, Sütterlin M, Wenz F. Health-related quality of life after breast-conserving surgery and intraoperative radiotherapy for breast cancer using low-kilovoltage X-rays. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(Suppl 3):359–67. 10.1245/s10434-010-1257-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, Bauer L, Kehrer T, Hermann B, Melchert F, Wenz F. Intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) as a boost in patients with early-stage breast cancer -- acute toxicity. Onkologie. 2006;29(3):77–82. 10.1159/000091160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorrentino L, Fissi S, Meaglia I, Bossi D, Caserini O, Mazzucchelli S, Truffi M, Albasini S, Tabarelli P, Liotta M, Ivaldi GB, Corsi F. One-step intraoperative radiotherapy optimizes Conservative treatment of breast cancer with advantages in quality of life and work resumption. Breast. 2018;39:123–30. 10.1016/j.breast.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fadavi P, Nafissi N, Mahdavi SR, Jafarnejadi B, Javadinia SA. Outcome of hypofractionated breast irradiation and intraoperative electron boost in early breast cancer: A randomized non-inferiority clinical trial. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2021;4(5):e1376. 10.1002/cnr2.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brouwers PJAM, van Werkhoven E, Bartelink H, Fourquet A, Lemanski C, van Loon J, Maduro JH, Russell NS, Scheijmans LJEE, Schinagl DAX, Westenberg AH, Poortmans P, Boersma LJ. Young boost trial research group. Predictors for poor cosmetic outcome in patients with early stage breast cancer treated with breast conserving therapy: results of the young boost trial. Radiother Oncol. 2018;128(3):434–41. 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wenz F, Welzel G, Keller A, Blank E, Vorodi F, Herskind C, Tomé O, Sütterlin M, Kraus -T, iefenbacher U. Early initiation of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) May increase the risk of long-term toxicity in patients undergoing intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) as a boost for breast cancer. Breast. 2008;17(6):617–22. 10.1016/j.breast.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowler JF. The linear-quadratic formula and progress in fractionated radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 1989;62(740):679–94. 10.1259/0007-1285-62-740-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.START Trialists’ Group, Bentzen SM, Agrawal RK, Aird EG, Barrett JM, Barrett-Lee PJ, Bentzen SM, Bliss JM, Brown J, Dewar JA, Dobbs HJ, Haviland JS, Hoskin PJ, Hopwood P, Lawton PA, Magee BJ, Mills J, Morgan DA, Owen JR, Simmons S, Sumo G, Sydenham MA, Venables K, Yarnold JR. The UK standardisation of breast radiotherapy (START) trial B of radiotherapy hypofractionation for treatment of early breast cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1098–107. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60348-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whelan TJ, Kim DH, Sussman J. Clinical experience using hypofractionated radiation schedules in breast cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2008;18(4):257–64. 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartelink H. Commentary on the paper A preliminary report of intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) in limited-stage breast cancers that are conservatively treated. A critical review of an innovative approach. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(17):2143–6. 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Figure 1. DFS stratified by age.

Supplementary Material 2: Supplementary Figure 2. DFS stratified by tumor size (T stage).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.